Lincoln–Douglas Debates on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

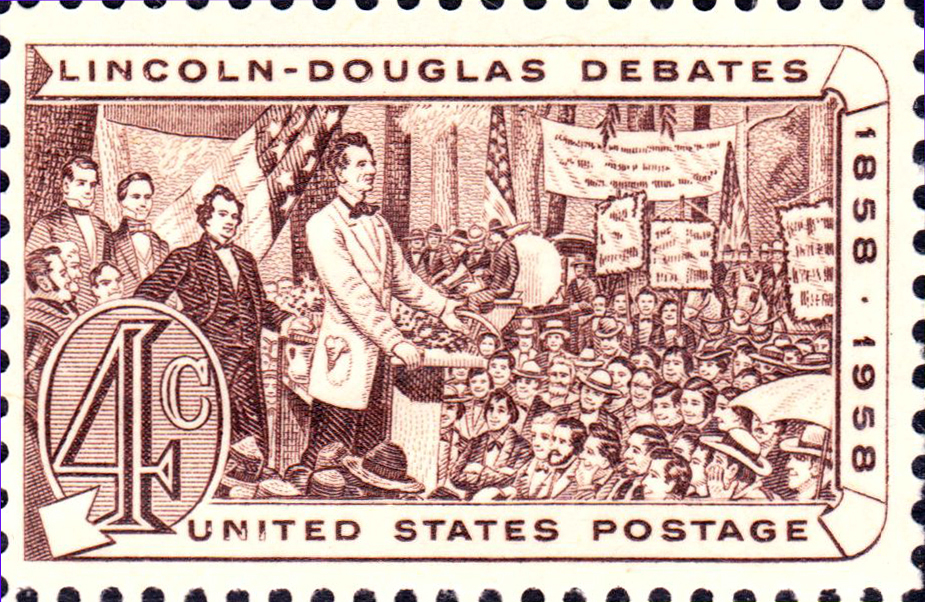

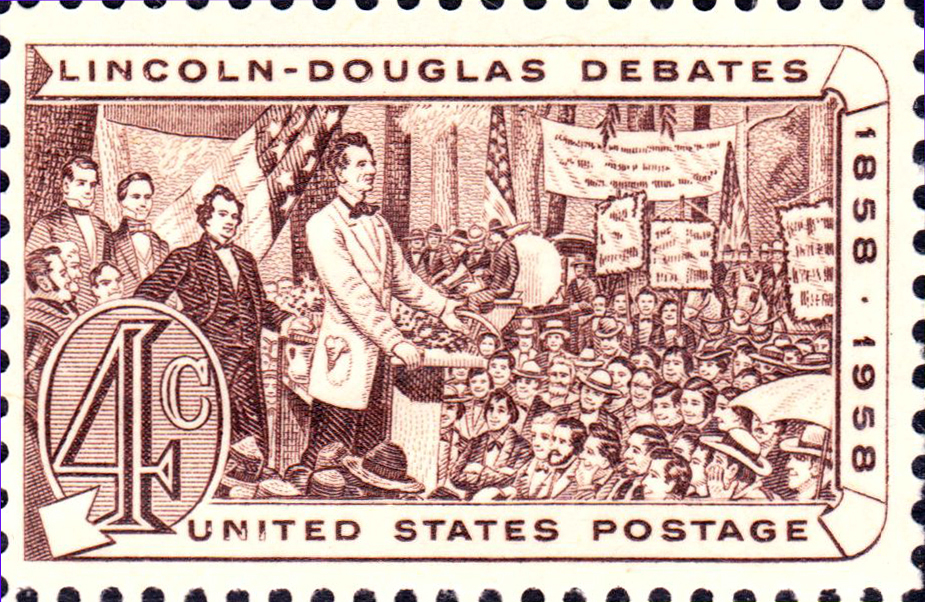

The Lincoln–Douglas debates were a series of seven debates between

The Lincoln–Douglas debates were a series of seven debates between

The debate locations in Illinois feature plaques and statuary of Douglas and Lincoln.

There is a Lincoln–Douglas Debate Museum in Charleston.

In 1994,

The debate locations in Illinois feature plaques and statuary of Douglas and Lincoln.

There is a Lincoln–Douglas Debate Museum in Charleston.

In 1994,

''The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln''

* Jaffa, Harry V. (1957). "Expediency and Morality in The Lincoln-Douglas Debates," ''The Anchor Review'', No. 2, pp. 177-204. * *

Website of the Stephen A. Douglas Association

Original Manuscripts and Primary Sources: Lincoln-Douglas Debates, First Edition 1860

Shapell Manuscript Foundation

Digital History

(archived link)

Bartleby Etext: ''Political Debates Between Abraham Lincoln and Stephen A. Douglas''

Mr. Lincoln and Freedom: Lincoln–Douglas Debates

Abraham Lincoln: A Resource Guide from the Library of Congress

Free audio book of "Noted Speeches of Abraham Lincoln," including the Lincoln-Douglas Debates.

''Booknotes'' interview with Harold Holzer on ''The Lincoln-Douglas Debates'', August 22, 1993.

Lincoln Douglas Debate Transcripts

on the

Conceptions of race central to Lincoln-Douglas debates – Pantagraph

(Bloomington, Illinois newspaper) {{DEFAULTSORT:Lincoln-Douglas Debates Of 1858 Political history of Illinois 1858 United States Senate elections Speeches by Abraham Lincoln Political debates Presidents of the United States and slavery Alton, Illinois Coles County, Illinois Freeport, Illinois Galesburg, Illinois Ottawa, Illinois Quincy, Illinois Union County, Illinois 1858 in Illinois Origins of the American Civil War 1858 in the United States Legal history of Kansas

The Lincoln–Douglas debates were a series of seven debates between

The Lincoln–Douglas debates were a series of seven debates between Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation thro ...

, the Republican Party candidate for the United States Senate

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and pow ...

from Illinois

Illinois ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern United States. Its largest metropolitan areas include the Chicago metropolitan area, and the Metro East section, of Greater St. Louis. Other smaller metropolita ...

, and incumbent Senator Stephen Douglas

Stephen Arnold Douglas (April 23, 1813 – June 3, 1861) was an American politician and lawyer from Illinois. A senator, he was one of two nominees of the badly split Democratic Party for president in the 1860 presidential election, which was ...

, the Democratic Party Democratic Party most often refers to:

*Democratic Party (United States)

Democratic Party and similar terms may also refer to:

Active parties Africa

*Botswana Democratic Party

*Democratic Party of Equatorial Guinea

*Gabonese Democratic Party

*Demo ...

candidate. Until the Seventeenth Amendment to the United States Constitution

The Seventeenth Amendment (Amendment XVII) to the United States Constitution established the direct election of United States senators in each state. The amendment supersedes Article I, Section 3, Clauses 1 and2 of the Constitution, under wh ...

, which provides that senators shall be elected by the people of their states, was ratified in 1913, senators were elected by their respective state legislatures, so Lincoln and Douglas were trying to win the votes of the Illinois General Assembly

The Illinois General Assembly is the legislature of the U.S. state of Illinois. It has two chambers, the Illinois House of Representatives and the Illinois Senate. The General Assembly was created by the first state constitution adopted in 181 ...

for their respective parties.

The debates were designed to generate publicity—some of the first examples of what later would be called media events. For Lincoln, they were an opportunity to raise both his national profile and the burgeoning Republican Party, while Douglas sought to defend his record—especially his leading role in the doctrine of popular sovereignty

Popular sovereignty is the principle that the authority of a state and its government are created and sustained by the consent of its people, who are the source of all political power. Popular sovereignty, being a principle, does not imply any ...

and its incarnation in the Kansas–Nebraska Act

The Kansas–Nebraska Act of 1854 () was a territorial organic act that created the territories of Kansas and Nebraska. It was drafted by Democratic Senator Stephen A. Douglas, passed by the 33rd United States Congress, and signed into law by ...

of 1854. The candidates spoke in each of Illinois's nine congressional districts. Both candidates had already spoken in Springfield

Springfield may refer to:

* Springfield (toponym), the place name in general

Places and locations Australia

* Springfield, New South Wales (Central Coast)

* Springfield, New South Wales (Snowy Monaro Regional Council)

* Springfield, Queenslan ...

and Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name ...

within a day of each other, so they decided that their joint appearances would be held in the remaining seven districts. Each debate lasted about three hours; one candidate spoke for 60 minutes, followed by a 90-minute response and a final 30-minute rejoinder by the first candidate. The candidates alternated speaking first. As the incumbent, Douglas spoke first in four of the debates. They were held outdoors, weather permitting, from about 2 to 5 p.m. There were fields full of listeners.

The debates focused on slavery, specifically whether it would be allowed in the new states to be formed from the territory acquired through the Louisiana Purchase

The Louisiana Purchase (french: Vente de la Louisiane, translation=Sale of Louisiana) was the acquisition of the territory of Louisiana by the United States from the French First Republic in 1803. In return for fifteen million dollars, or app ...

and the Mexican Cession

The Mexican Cession ( es, Cesión mexicana) is the region in the modern-day southwestern United States that Mexico originally controlled, then ceded to the United States in the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848 after the Mexican–American War ...

. Douglas, as the Democratic candidate, held that the decision should be made by the residents of the new states themselves rather than by the federal government (popular sovereignty). Lincoln argued against the expansion of slavery, yet stressed that he was not advocating its abolition where it already existed.

Never in American history had there been newspaper coverage of such intensity. Both candidates felt they were talking to the whole nation. New technology was readily available: railroads, the telegraph

Telegraphy is the long-distance transmission of messages where the sender uses symbolic codes, known to the recipient, rather than a physical exchange of an object bearing the message. Thus flag semaphore is a method of telegraphy, whereas p ...

, and Pitman shorthand

Pitman shorthand is a system of shorthand for the English language developed by Englishman Sir Isaac Pitman (1813–1897), who first presented it in 1837. Like most systems of shorthand, it is a phonetic system; the symbols do not represent lette ...

, at the time called phonography. The state's largest newspapers, from Chicago, sent phonographers (stenographers

Shorthand is an abbreviated symbolic writing method that increases speed and brevity of writing as compared to longhand, a more common method of writing a language. The process of writing in shorthand is called stenography, from the Greek ''ste ...

) to report complete texts of each debate; thanks to the new railroads, the debates were not hard to reach from Chicago. Halfway through each debate, runners were handed the stenographers' notes. They raced for the next train to Chicago, handing them to riding stenographers who during the journey converted the shorthand back into words, producing a transcript ready for the Chicago typesetter and for the telegrapher, who sent it to the rest of the country (east of the Rockies) as soon as it arrived. The next train brought the conclusion. The papers published the speeches in full, sometimes within hours of their delivery. Some newspapers helped their own candidate with minor corrections, reports on the audience's positive reaction, or tendentious headlines ("New and Powerful Argument by Mr. Lincoln—Douglas Tells the Same Old Story"). The newswire

A news agency is an organization that gathers news reports and sells them to subscribing news organizations, such as newspapers, magazines and radio and television broadcasters. A news agency may also be referred to as a wire service, newswire, ...

of the Associated Press

The Associated Press (AP) is an American non-profit news agency headquartered in New York City. Founded in 1846, it operates as a cooperative, unincorporated association. It produces news reports that are distributed to its members, U.S. newspa ...

sent messages simultaneously to multiple points, so newspapers all across the country (east of the Rocky Mountains

The Rocky Mountains, also known as the Rockies, are a major mountain range and the largest mountain system in North America. The Rocky Mountains stretch in straight-line distance from the northernmost part of western Canada, to New Mexico in ...

) printed them, and the debates quickly became national events. They were republished as pamphlets.

The debates took place between August and October 1858. Newspapers reported 12,000 in attendance at Ottawa, 16,000 to 18,000 in Galesburg, 15,000 in Freeport,

12,000 in Quincy, and at the last one, in Alton, 5,000 to 10,000. The debates near Illinois's borders ( Freeport, Quincy, and Alton

Alton may refer to:

People

*Alton (given name)

*Alton (surname)

Places Australia

*Alton National Park, Queensland

* Alton, Queensland, a town in the Shire of Balonne

Canada

* Alton, Ontario

*Alton, Nova Scotia

New Zealand

* Alton, New Zealand, ...

) drew large numbers of people from neighboring states. A number travelled within Illinois to follow the debates.

Douglas was re-elected by the Illinois General Assembly, 54–46. But the publicity made Lincoln a national figure and laid the groundwork for his 1860 presidential campaign.

As part of that endeavor, Lincoln edited the texts of all the debates and had them published in a book. It sold well and helped him receive the Republican Party's nomination for president at the 1860 Republican National Convention

The 1860 Republican National Convention was a presidential nominating convention that met May 16-18 in Chicago, Illinois. It was held to nominate the Republican Party's candidates for president and vice president in the 1860 election. The conven ...

in Chicago.

Background

Douglas had first been elected to the United States Senate in 1846, and he was seeking re-election for a third term in 1858. The issue of slavery was raised several times during his tenure in the Senate, particularly with respect to theCompromise of 1850

The Compromise of 1850 was a package of five separate bills passed by the United States Congress in September 1850 that defused a political confrontation between slave and free states on the status of territories acquired in the Mexican–Ame ...

. As chairman of the committee on U.S. territories

Territories of the United States are sub-national administrative divisions overseen by the federal government of the United States. The various American territories differ from the U.S. states and tribal reservations as they are not sover ...

, he argued for an approach to slavery called popular sovereignty

Popular sovereignty is the principle that the authority of a state and its government are created and sustained by the consent of its people, who are the source of all political power. Popular sovereignty, being a principle, does not imply any ...

: electorates in the territories would vote whether to adopt or reject slavery. Decisions previously had been made at the federal level concerning slavery in the territories. Douglas was successful with passage of the Kansas–Nebraska Act

The Kansas–Nebraska Act of 1854 () was a territorial organic act that created the territories of Kansas and Nebraska. It was drafted by Democratic Senator Stephen A. Douglas, passed by the 33rd United States Congress, and signed into law by ...

in 1854. The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History

The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History was founded in New York City by businessmen-philanthropists Richard Gilder and Lewis E. Lehrman in 1994 to promote the study and interest in American history.

The Institute serves teachers, studen ...

's ''Mr. Lincoln and Friends Society'' notes that prominent Bloomington, Illinois resident Jesse W. Fell

Jesse W. Fell (November 10, 1808 – February 25, 1887) was an American businessman and landowner. He was instrumental in the founding of Illinois State University as well as Normal, Pontiac, Clinton, Towanda, Dwight, DeWitt County and Liv ...

, a local real estate developer who founded the ''Bloomington Pantagraph

''The Pantagraph'' is a daily newspaper that serves Bloomington–Normal, Illinois, along with 60 communities and eight counties in the Central Illinois area. Its headquarters are in Bloomington and it is owned by Lee Enterprises. The name is d ...

'' and who befriended Lincoln in 1834, had suggested the debates in 1854.

Lincoln had also been elected to Congress in 1846, and he served a two-year term in the House of Representatives. During his time in the House, he disagreed with Douglas and supported the Wilmot Proviso

The Wilmot Proviso was an unsuccessful 1846 proposal in the United States Congress to ban slavery in territory acquired from Mexico in the Mexican–American War. The conflict over the Wilmot Proviso was one of the major events leading to the ...

, which sought to ban slavery in any new territory. He returned to politics in the 1850s to oppose the Kansas–Nebraska Act and to help develop the new Republican Party.

Before the debates, Lincoln charged that Douglas was encouraging fears of amalgamation of the races, with enough success to drive thousands of people away from the Republican Party. Douglas replied that Lincoln was an abolitionist

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery. In Western Europe and the Americas, abolitionism was a historic movement that sought to end the Atlantic slave trade and liberate the enslaved people.

The British ...

for saying that the American Declaration of Independence

The United States Declaration of Independence, formally The unanimous Declaration of the thirteen States of America, is the pronouncement and founding document adopted by the Second Continental Congress meeting at Pennsylvania State House ...

applied to blacks

Black is a racialized classification of people, usually a political and skin color-based category for specific populations with a mid to dark brown complexion. Not all people considered "black" have dark skin; in certain countries, often in ...

as well as whites

White is a racialized classification of people and a skin color specifier, generally used for people of European origin, although the definition can vary depending on context, nationality, and point of view.

Description of populations as " ...

.

Lincoln argued in his House Divided Speech that Douglas was part of a conspiracy to nationalize slavery. Lincoln said that ending the Missouri Compromise

The Missouri Compromise was a federal legislation of the United States that balanced desires of northern states to prevent expansion of slavery in the country with those of southern states to expand it. It admitted Missouri as a Slave states an ...

ban on slavery in Kansas and Nebraska was the first step in this nationalizing and that the Dred Scott decision

''Dred Scott v. Sandford'', 60 U.S. (19 How.) 393 (1857), was a landmark decision of the United States Supreme Court that held the U.S. Constitution did not extend American citizenship to people of black African descent, enslaved or free; th ...

was another step in the direction of spreading slavery into Northern territories. He expressed the fear that any similar Supreme Court decision would turn Illinois into a slave state.

Much has been written of Lincoln's rhetorical style but, going into the debates, Douglas's reputation was a daunting one. As James G. Blaine later wrote:

The debates

When Lincoln made the debates into a book, in 1860, he included the following material as preliminaries: * Speech atSpringfield

Springfield may refer to:

* Springfield (toponym), the place name in general

Places and locations Australia

* Springfield, New South Wales (Central Coast)

* Springfield, New South Wales (Snowy Monaro Regional Council)

* Springfield, Queenslan ...

by Lincoln, June 16, the "Lincoln's House Divided Speech

The House Divided Speech was an address given by Illinois senatorial candidate and future president of the United States Abraham Lincoln, on June 16, 1858, at what was then the Illinois State Capitol in Springfield, after he had accepted the I ...

" speech (in the volume, the erroneous date June 17 is given)

* Speech at Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name ...

by Douglas, July 9

* Speech at Chicago by Lincoln, July 10

* Speech at Bloomington by Douglas, July 16

* Speech at Springfield by Douglas, July 17 (Lincoln was not present)

* Speech at Springfield by Lincoln, July 17 (Douglas was not present)

* Preliminary correspondence of Lincoln and Douglas, July 24–31

The debates were held in seven towns in the state of Illinois:

* Ottawa

Ottawa (, ; Canadian French: ) is the capital city of Canada. It is located at the confluence of the Ottawa River and the Rideau River in the southern portion of the province of Ontario. Ottawa borders Gatineau, Quebec, and forms the core ...

on August 21

* Freeport on August 27

* Jonesboro on September 15

* Charleston on September 18

* Galesburg on October 7

* Quincy on October 13

* Alton

Alton may refer to:

People

*Alton (given name)

*Alton (surname)

Places Australia

*Alton National Park, Queensland

* Alton, Queensland, a town in the Shire of Balonne

Canada

* Alton, Ontario

*Alton, Nova Scotia

New Zealand

* Alton, New Zealand, ...

on October 15

Slavery was the main theme of the Lincoln–Douglas debates, particularly the issue of slavery's expansion into the territories

A territory is an area of land, sea, or space, particularly belonging or connected to a country, person, or animal.

In international politics, a territory is usually either the total area from which a state may extract power resources or an ...

. Douglas's Kansas–Nebraska Act

The Kansas–Nebraska Act of 1854 () was a territorial organic act that created the territories of Kansas and Nebraska. It was drafted by Democratic Senator Stephen A. Douglas, passed by the 33rd United States Congress, and signed into law by ...

repealed the Missouri Compromise

The Missouri Compromise was a federal legislation of the United States that balanced desires of northern states to prevent expansion of slavery in the country with those of southern states to expand it. It admitted Missouri as a Slave states an ...

's ban on slavery in the territories of Kansas

Kansas () is a state in the Midwestern United States. Its capital is Topeka, and its largest city is Wichita. Kansas is a landlocked state bordered by Nebraska to the north; Missouri to the east; Oklahoma to the south; and Colorado to the ...

and Nebraska

Nebraska () is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. It is bordered by South Dakota to the north; Iowa to the east and Missouri to the southeast, both across the Missouri River; Kansas to the south; Colorado to the southwe ...

and replaced it with the doctrine of popular sovereignty

Popular sovereignty is the principle that the authority of a state and its government are created and sustained by the consent of its people, who are the source of all political power. Popular sovereignty, being a principle, does not imply any ...

, which meant that the people of a territory would vote as to whether to allow slavery. During the debates, both Lincoln and Douglas appealed to the "Fathers" ( Founding Fathers) to bolster their cases.

Ottawa

Lincoln said at Ottawa: Lincoln said in the first debate, in Ottawa, that popular sovereignty would nationalize and perpetuate slavery. Douglas replied that both Whigs and Democrats believed in popular sovereignty and that theCompromise of 1850

The Compromise of 1850 was a package of five separate bills passed by the United States Congress in September 1850 that defused a political confrontation between slave and free states on the status of territories acquired in the Mexican–Ame ...

was an example of this. Lincoln said that the national policy was to limit the spread of slavery, and he mentioned the Northwest Ordinance

The Northwest Ordinance (formally An Ordinance for the Government of the Territory of the United States, North-West of the River Ohio and also known as the Ordinance of 1787), enacted July 13, 1787, was an organic act of the Congress of the Co ...

of 1787 as an example of this policy, which banned slavery from a large part of the Midwest.

The Compromise of 1850 allowed the territories of Utah

Utah ( , ) is a state in the Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. Utah is a landlocked U.S. state bordered to its east by Colorado, to its northeast by Wyoming, to its north by Idaho, to its south by Arizona, and to it ...

and New Mexico

)

, population_demonym = New Mexican ( es, Neomexicano, Neomejicano, Nuevo Mexicano)

, seat = Santa Fe

, LargestCity = Albuquerque

, LargestMetro = Tiguex

, OfficialLang = None

, Languages = English, Spanish ( New Mexican), Navajo, Ker ...

to decide for or against slavery, but it also allowed the admission of California

California is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States, located along the West Coast of the United States, Pacific Coast. With nearly 39.2million residents across a total area of approximately , it is the List of states and territori ...

as a free state, reduced the size of the slave state of Texas

Texas (, ; Spanish language, Spanish: ''Texas'', ''Tejas'') is a state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States. At 268,596 square miles (695,662 km2), and with more than 29.1 million residents in 2 ...

by adjusting the boundary, and ended the slave trade (but not slavery itself) in the District of Columbia

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, ...

. In return, the South got a stronger Fugitive Slave Law

The fugitive slave laws were laws passed by the United States Congress in 1793 and 1850 to provide for the return of enslaved people who escaped from one state into another state or territory. The idea of the fugitive slave law was derived from ...

than the version mentioned in the Constitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organisation or other type of Legal entity, entity and commonly determine how that entity is to be governed.

When ...

. Douglas said that the Compromise of 1850 replaced the Missouri Compromise's ban on slavery in the Louisiana Purchase

The Louisiana Purchase (french: Vente de la Louisiane, translation=Sale of Louisiana) was the acquisition of the territory of Louisiana by the United States from the French First Republic in 1803. In return for fifteen million dollars, or app ...

territory north and west of the state of Missouri

Missouri is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. Ranking List of U.S. states and territories by area, 21st in land area, it is bordered by eight states (tied for the most with Tennessee ...

, while Lincoln said—a topic he went back to in the Jonesboro debate—that Douglas was mistaken in seeing "Popular Sovereignty" and the ''Dred Scott

Dred Scott (c. 1799 – September 17, 1858) was an Slavery in the United States, enslaved African Americans, African American man who, along with his wife, Harriet Robinson Scott, Harriet, unsuccessfully sued for freedom for themselves and thei ...

'' decision as being in harmony with the Compromise of 1850. To the contrary, "Popular Sovereignty" would nationalize slavery.

There were partisan remarks, such as Douglas's accusations that members of the "Black Republican" party were abolitionists, including Lincoln, and he cited as proof Lincoln's House Divided Speech

The House Divided Speech was an address given by Illinois senatorial candidate and future president of the United States Abraham Lincoln, on June 16, 1858, at what was then the Illinois State Capitol in Springfield, after he had accepted the I ...

, in which he said, "I believe this government cannot endure permanently half slave and half free."First Debate: Ottawa, Illinois, Douglas quote, August 21, 1858. Douglas also charged Lincoln with opposing the ''Dred Scott

Dred Scott (c. 1799 – September 17, 1858) was an Slavery in the United States, enslaved African Americans, African American man who, along with his wife, Harriet Robinson Scott, Harriet, unsuccessfully sued for freedom for themselves and thei ...

'' decision because "it deprives the negro of the rights and privileges of citizenship." Lincoln responded that "the next Dred Scott decision" could allow slavery to spread into free states. Douglas accused Lincoln of wanting to overthrow state laws that excluded Blacks from states such as Illinois, which were popular with the northern Democrats. Lincoln did not argue for complete social equality, but he did say that Douglas ignored the basic humanity of Blacks and that slaves did have an equal right to liberty, stating "I agree with Judge Douglas he is not my equal in many respects—certainly not in color, perhaps not in moral or intellectual endowment. But in the right to eat the bread, without the leave of anybody else, which his own hand earns, he is my equal and the equal of Judge Douglas, and the equal of every living man."

Lincoln said that he did not know how emancipation should happen. He believed in colonization in Africa by emancipated slaves

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery. In Western Europe and the Americas, abolitionism was a historic movement that sought to end the Atlantic slave trade and liberate the enslaved people.

The Britis ...

, but admitted that it was impractical. He said that it would be wrong for emancipated slaves to be treated as "underlings", but that there was a large opposition to social and political equality and that "a universal feeling, whether well or ill-founded, cannot be safely disregarded." He said that Douglas's public indifference would result in the expansion of slavery because it would mold public sentiment to accept it. As Lincoln said, "public sentiment is everything. With public sentiment, nothing can fail; without it, nothing can succeed. Consequently he who molds public sentiment goes deeper than he who enacts statutes or pronounces decisions. He makes statutes and decisions possible or impossible to be executed." He said that Douglas "cares not whether slavery is voted down or voted up," and that he would "blow out the moral lights around us" and eradicate the love of liberty.

Freeport

At the debate at Freeport, Lincoln forced Douglas to choose between two options, either of which would damage Douglas's popularity and chances of getting reelected. He asked Douglas to reconcile popular sovereignty with the Supreme Court's ''Dred Scott'' decision. Douglas responded that the people of a territory could keep slavery out even though the Supreme Court said that thefederal government

A federation (also known as a federal state) is a political entity characterized by a union of partially self-governing provinces, states, or other regions under a central federal government (federalism). In a federation, the self-governin ...

had no authority to exclude slavery, simply by refusing to pass a slave code

The slave codes were laws relating to slavery and enslaved people, specifically regarding the Atlantic slave trade and chattel slavery in the Americas.

Most slave codes were concerned with the rights and duties of free people in regards to ensl ...

and other legislation needed to protect slavery. Douglas alienated Southerners with this Freeport Doctrine

The Freeport Doctrine was articulated by Stephen A. Douglas at the second of the Lincoln-Douglas debates on August 27, 1858, in Freeport, Illinois. Former one-term U.S. Representative Abraham Lincoln was campaigning to take Douglas's U.S. Senate ...

, which damaged his chances of winning the Presidency in 1860. As a result, Southern politicians used their demand for a slave code to drive a wedge between the Northern and Southern wings of the Democratic Party, splitting the majority political party in 1858.

Douglas failed to gain support in all sections of the country through popular sovereignty. By allowing slavery where the majority wanted it, he lost the support of Republicans led by Lincoln, who thought that Douglas was unprincipled. He lost the support of the South by rejecting the pro-slavery Lecompton Constitution

The Lecompton Constitution (1859) was the second of four proposed constitutions for the state of Kansas. Named for the city of Lecompton where it was drafted, it was strongly pro-slavery. It never went into effect.

History Purpose

The Lecompton Co ...

and advocating a Freeport Doctrine

The Freeport Doctrine was articulated by Stephen A. Douglas at the second of the Lincoln-Douglas debates on August 27, 1858, in Freeport, Illinois. Former one-term U.S. Representative Abraham Lincoln was campaigning to take Douglas's U.S. Senate ...

to stop slavery in Kansas, where the majority were anti-slavery.

Jonesboro

In his address in Jonesboro, Lincoln said that the expansion of slavery would endanger the Union, and mentioned the controversies over slavery in Missouri in 1820, in the territories conquered from Mexico that led to the Compromise of 1850, and again with theBleeding Kansas

Bleeding Kansas, Bloody Kansas, or the Border War was a series of violent civil confrontations in Kansas Territory, and to a lesser extent in western Missouri, between 1854 and 1859. It emerged from a political and ideological debate over the ...

controversy. He said that the crisis would be reached and passed when slavery was put "in the course of ultimate extinction."

Charleston

Before the debate at Charleston, Democrats held up a banner that read "Negro equality" with a picture of a white man, a negro woman, and amulatto

(, ) is a racial classification to refer to people of mixed African and European ancestry. Its use is considered outdated and offensive in several languages, including English and Dutch, whereas in languages such as Spanish and Portuguese is ...

child.

Lincoln began his address by clarifying that his concerns about slavery did not equate to support for racial equality

Racial equality is a situation in which people of all races and ethnicities are treated in an egalitarian/equal manner. Racial equality occurs when institutions give individuals legal, moral, and political rights. In present-day Western society, ...

. He stated:

In his subsequent response, Stephen Douglas said that Lincoln had an ally in Frederick Douglass in preaching "abolition doctrines." He said that Frederick Douglass told "all the friends of negro equality and negro citizenship to rally as one man around Abraham Lincoln." He also charged Lincoln with a lack of consistency when speaking on the issue of racial equality (in the Charleston debate) and cited Lincoln's previous statements that the declaration that all men are created equal

The quotation "all men are created equal" is part of the sentence in the U.S. Declaration of Independence

The United States Declaration of Independence, formally The unanimous Declaration of the thirteen States of America, is the pronounc ...

applies to blacks as well as whites.

In response to Douglas's questioning of Lincoln's support of negro citizenship, if not full equality, Lincoln further clarified in his rejoinder: "I tell him very frankly that I am not in favor of negro citizenship."

Galesburg

At Galesburg, using quotes from Lincoln's Chicago address, Douglas sought again to prove that Lincoln was an abolitionist because of his insistence upon the principle that "all men are equal".Alton

At Alton, Lincoln tried to reconcile his statements on equality. He said that the authors of the Declaration of Independence "intended to include all men, but they did not mean to declare all men equal in all respects." As Lincoln said, "They meant to set up a standard maxim for the free society which should be familiar to all,—constantly looked to, constantly labored for, and even, though never perfectly attained, constantly approximated, and thereby constantly spreading and deepening its influence, and augmenting the happiness and value of life to all people, of all colors, everywhere." He contrasted his support for the Declaration with opposing statements made by John C. Calhoun and SenatorJohn Pettit

John Pettit (June 24, 1807January 17, 1877) was an American lawyer, jurist, and politician. A United States Representative and Senator from Indiana, he also served in the court systems of Indiana and Kansas.

Born in Sackets Harbor, New York, h ...

of Indiana, who called the Declaration "a self-evident lie". Lincoln said that Chief Justice Roger Taney

Roger Brooke Taney (; March 17, 1777 – October 12, 1864) was the fifth chief justice of the United States, holding that office from 1836 until his death in 1864. Although an opponent of slavery, believing it to be an evil practice, Taney belie ...

and Stephen Douglas were opposing Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 18 ...

's self-evident truth, dehumanizing blacks and preparing the public mind to think of them as only property. Lincoln thought that slavery had to be treated as a wrong and kept from growing.

As Lincoln said at Alton: These words were set to music by Aaron Copland

Aaron Copland (, ; November 14, 1900December 2, 1990) was an American composer, composition teacher, writer, and later a conductor of his own and other American music. Copland was referred to by his peers and critics as "the Dean of American Com ...

in his ''Lincoln Portrait

''Lincoln Portrait'' (also known as ''A Lincoln Portrait'') is a classical orchestral work written by the American composer Aaron Copland. The work involves a full orchestra, with particular emphasis on the brass section at climactic moments. The ...

''.

Lincoln used a number of colorful phrases in the debates. He said that one argument by Douglas made a horse chestnut into a chestnut horse, and he compared an evasion by Douglas to the sepia cloud from a cuttlefish. In Quincy, Lincoln said that Douglas's Freeport Doctrine was do-nothing sovereignty that was "as thin as the homeopathic soup that was made by boiling the shadow of a pigeon that had starved to death."

The role of technology

Recent improvements in technology were fundamental to the debates' success and popularity. New railroads connected major cities at high speeds—a message that on a horse would have taken a week arrived in hours. A forgotten "soft" technology,Pitman shorthand

Pitman shorthand is a system of shorthand for the English language developed by Englishman Sir Isaac Pitman (1813–1897), who first presented it in 1837. Like most systems of shorthand, it is a phonetic system; the symbols do not represent lette ...

, allowed writing to keep up with speech, far closer to a recording than had been possible before. Finally, messages could now be sent via the electrical telegraph

Electrical telegraphs were point-to-point text messaging systems, primarily used from the 1840s until the late 20th century. It was the first electrical telecommunications system and the most widely used of a number of early messaging systems ...

, anywhere east of the Rocky Mountains. "The combination of shorthand, the telegraph and the railroad changed everything," wrote Allen C. Guelzo, author of ''Lincoln and Douglas: The Debates That Defined America''. "It was unprecedented. Lincoln and Douglas knew they were speaking to the whole nation. It was like JFK

John Fitzgerald Kennedy (May 29, 1917 – November 22, 1963), often referred to by his initials JFK and the nickname Jack, was an American politician who served as the 35th president of the United States from 1961 until his assassination i ...

in 1960 coming to grips with the presence of the vast new television audience."

Results

TheOctober surprise

In U.S. political jargon, an October surprise is a news event that may influence the outcome of an upcoming November election (particularly one for the U.S. presidency), whether deliberately planned or spontaneously occurring. Because the date ...

of the election was former Whig John J. Crittenden

John Jordan Crittenden (September 10, 1787 July 26, 1863) was an American statesman and politician from the U.S. state of Kentucky. He represented the state in the U.S. House of Representatives and the U.S. Senate and twice served as Unite ...

's endorsement of Douglas. Non-Republican former Whigs comprised the biggest block of swing vote

A swing vote is a vote that is seen as potentially going to any of a number of candidates in an election, or, in a two-party system, may go to either of the two dominant political parties. Such votes are usually sought after in election campaign ...

rs, and Crittenden's endorsement of Douglas rather than Lincoln reduced Lincoln's chances of winning.

The districts were drawn to favor Douglas's party, and the Democrats won 40 seats in the state House of Representatives while the Republicans won 35. In the State Senate, Republicans held 11 seats and Democrats held 14. Douglas was re-elected by the legislature 54–46, even though Republican candidates for the state legislature together received 24,094 more votes than candidates supporting Douglas. However, the widespread media coverage of the debates greatly raised Lincoln's national profile, making him a viable candidate for nomination as the Republican candidate in the upcoming 1860 presidential election.

Ohio Republican committee chairman George Parsons put Lincoln in touch with Ohio's main political publisher, Follett and Foster, of Columbus. It published copies of the text in ''Political Debates Between Hon. Abraham Lincoln and Hon. Stephen A. Douglas in the Celebrated Campaign of 1858, in Illinois.'' Four printings were made, and the fourth sold 16,000 copies.

Commemoration

The debate locations in Illinois feature plaques and statuary of Douglas and Lincoln.

There is a Lincoln–Douglas Debate Museum in Charleston.

In 1994,

The debate locations in Illinois feature plaques and statuary of Douglas and Lincoln.

There is a Lincoln–Douglas Debate Museum in Charleston.

In 1994, C-SPAN

Cable-Satellite Public Affairs Network (C-SPAN ) is an American cable and satellite television network that was created in 1979 by the cable television industry as a nonprofit public service. It televises many proceedings of the United States ...

aired a series of re-enactments of the debates filmed on location.

See also

*Bleeding Kansas

Bleeding Kansas, Bloody Kansas, or the Border War was a series of violent civil confrontations in Kansas Territory, and to a lesser extent in western Missouri, between 1854 and 1859. It emerged from a political and ideological debate over the ...

Notes

Further reading

* On January 1, 2009, BBC Audiobooks America, published the first complete recording of the Lincoln–Douglas Debates, starring actorsDavid Strathairn

David Russell Strathairn (; born January 26, 1949) is an American actor. Known for his leading roles on stage and screen, he has often portrayed historical figures such as Edward R. Murrow, J. Robert Oppenheimer, William H. Seward, and John Dos ...

as Abraham Lincoln and Richard Dreyfuss

Richard Stephen Dreyfuss (; born Dreyfus; October 29, 1947) is an American actor. He is known for starring in popular films during the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s, including ''American Graffiti'' (1973), ''Jaws'' (1975), ''Close Encounters of the T ...

as Stephen Douglas with an introduction by Allen C. Guelzo

Allen Carl Guelzo (born 1953) is an American historian who serves as Senior Research Scholar in the Council of the Humanities and Director of the Initiative on Politics and Statesmanship in the James Madison Program at Princeton University. He f ...

, Henry R. Luce III Professor of the Civil War Era at Gettysburg College. The text of the recording was provided courtesy of the Abraham Lincoln Association as presented i''The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln''

* Jaffa, Harry V. (1957). "Expediency and Morality in The Lincoln-Douglas Debates," ''The Anchor Review'', No. 2, pp. 177-204. * *

External links

Website of the Stephen A. Douglas Association

Original Manuscripts and Primary Sources: Lincoln-Douglas Debates, First Edition 1860

Shapell Manuscript Foundation

Digital History

(archived link)

Bartleby Etext: ''Political Debates Between Abraham Lincoln and Stephen A. Douglas''

Mr. Lincoln and Freedom: Lincoln–Douglas Debates

Abraham Lincoln: A Resource Guide from the Library of Congress

Free audio book of "Noted Speeches of Abraham Lincoln," including the Lincoln-Douglas Debates.

''Booknotes'' interview with Harold Holzer on ''The Lincoln-Douglas Debates'', August 22, 1993.

Lincoln Douglas Debate Transcripts

on the

Internet Archive

The Internet Archive is an American digital library with the stated mission of "universal access to all knowledge". It provides free public access to collections of digitized materials, including websites, software applications/games, music, ...

Conceptions of race central to Lincoln-Douglas debates – Pantagraph

(Bloomington, Illinois newspaper) {{DEFAULTSORT:Lincoln-Douglas Debates Of 1858 Political history of Illinois 1858 United States Senate elections Speeches by Abraham Lincoln Political debates Presidents of the United States and slavery Alton, Illinois Coles County, Illinois Freeport, Illinois Galesburg, Illinois Ottawa, Illinois Quincy, Illinois Union County, Illinois 1858 in Illinois Origins of the American Civil War 1858 in the United States Legal history of Kansas