Lincoln's Assassination on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

On April 14, 1865,

John Wilkes Booth, born in

John Wilkes Booth, born in  Booth and Lincoln were not personally acquainted, but Lincoln had seen Booth at Ford's Theatre in 1863. After the assassination, actor Frank Mordaunt wrote that Lincoln, who apparently harbored no suspicions about Booth, admired the actor and had repeatedly but unsuccessfully invited him to visit the

Booth and Lincoln were not personally acquainted, but Lincoln had seen Booth at Ford's Theatre in 1863. After the assassination, actor Frank Mordaunt wrote that Lincoln, who apparently harbored no suspicions about Booth, admired the actor and had repeatedly but unsuccessfully invited him to visit the

On April 14, Booth's morning started at midnight. He wrote his mother that all was well but that he was "in haste". In his diary, he wrote that "Our cause being almost lost, something ''decisive'' and great must be done".

While visiting Ford's Theatre around noon to pick up his mail, Booth learned that Lincoln and Grant were to visit the theater that evening for a performance of ''Our American Cousin''. This provided him with an especially good opportunity to attack Lincoln since, having performed there several times, he knew the theater's layout and was familiar to its staff. Booth went to Mary Surratt's

On April 14, Booth's morning started at midnight. He wrote his mother that all was well but that he was "in haste". In his diary, he wrote that "Our cause being almost lost, something ''decisive'' and great must be done".

While visiting Ford's Theatre around noon to pick up his mail, Booth learned that Lincoln and Grant were to visit the theater that evening for a performance of ''Our American Cousin''. This provided him with an especially good opportunity to attack Lincoln since, having performed there several times, he knew the theater's layout and was familiar to its staff. Booth went to Mary Surratt's  The conspirators met for the final time at 8:45pm. Booth assigned Powell to kill Secretary of State William H. Seward at his home, Atzerodt to kill

The conspirators met for the final time at 8:45pm. Booth assigned Powell to kill Secretary of State William H. Seward at his home, Atzerodt to kill

Despite what Booth had heard earlier in the day, Grant and his wife, Julia Grant, had declined to accompany the Lincolns, as Mary Lincoln and Julia Grant were not on good terms. Others in succession also declined the Lincolns' invitation, until finally

Despite what Booth had heard earlier in the day, Grant and his wife, Julia Grant, had declined to accompany the Lincolns, as Mary Lincoln and Julia Grant were not on good terms. Others in succession also declined the Lincolns' invitation, until finally

Lincoln's usual protections were not in place that night at Ford's. Crook was on a second shift at the White House, and Ward Hill Lamon, Lincoln's personal bodyguard, was away in Richmond on assignment from Lincoln. John Frederick Parker was assigned to guard the Presidential Box. At intermission he went to a nearby tavern along with Lincoln's valet, Charles Forbes, and Coachman Francis Burke. Booth had several drinks while waiting for his planned time. It is unclear whether Parker returned to the theater, but he was certainly not at his post when Booth entered the box. In any event, there is no certainty that entry would have been denied to a celebrity such as Booth. Booth had prepared a brace to bar the door after entering the box, indicating that he expected a guard. After spending time at the tavern, Booth entered Ford's Theatre one last time at about 10:10 pm, this time through the theater's front entrance. He passed through the dress circle and went to the door that led to the Presidential Box after showing Charles Forbes his calling card. Navy Surgeon George Brainerd Todd saw Booth arrive:

Once inside the hallway, Booth

Lincoln's usual protections were not in place that night at Ford's. Crook was on a second shift at the White House, and Ward Hill Lamon, Lincoln's personal bodyguard, was away in Richmond on assignment from Lincoln. John Frederick Parker was assigned to guard the Presidential Box. At intermission he went to a nearby tavern along with Lincoln's valet, Charles Forbes, and Coachman Francis Burke. Booth had several drinks while waiting for his planned time. It is unclear whether Parker returned to the theater, but he was certainly not at his post when Booth entered the box. In any event, there is no certainty that entry would have been denied to a celebrity such as Booth. Booth had prepared a brace to bar the door after entering the box, indicating that he expected a guard. After spending time at the tavern, Booth entered Ford's Theatre one last time at about 10:10 pm, this time through the theater's front entrance. He passed through the dress circle and went to the door that led to the Presidential Box after showing Charles Forbes his calling card. Navy Surgeon George Brainerd Todd saw Booth arrive:

Once inside the hallway, Booth

All agreed Lincoln could not survive. Barnes probed the wound, locating the bullet and some bone fragments. Throughout the night, as the hemorrhage continued, they removed blood clots to relieve pressure on the brain, and Leale held the comatose president's hand with a firm grip, "to let him know that he was in touch with humanity and had a friend".

All agreed Lincoln could not survive. Barnes probed the wound, locating the bullet and some bone fragments. Throughout the night, as the hemorrhage continued, they removed blood clots to relieve pressure on the brain, and Leale held the comatose president's hand with a firm grip, "to let him know that he was in touch with humanity and had a friend".

Lincoln's older son Robert Todd Lincoln arrived at about 11 pm, but twelve-year-old Tad Lincoln, who was watching a play of ''

Lincoln's older son Robert Todd Lincoln arrived at about 11 pm, but twelve-year-old Tad Lincoln, who was watching a play of '' As he neared death, Lincoln's appearance became "perfectly natural" (except for the discoloration around his eyes). Shortly before 7am Mary was allowed to return to Lincoln's side, and, as Dixon reported, "she again seated herself by the President, kissing him and calling him every endearing name."

Lincoln died at 7:22 am on April 15. Mary Lincoln was not present. In his last moments, Lincoln's face became calm and his breathing quieter. Field wrote there was "no apparent suffering, no convulsive action, no rattling of the throat ... nlya mere cessation of breathing". According to Lincoln's secretary

As he neared death, Lincoln's appearance became "perfectly natural" (except for the discoloration around his eyes). Shortly before 7am Mary was allowed to return to Lincoln's side, and, as Dixon reported, "she again seated herself by the President, kissing him and calling him every endearing name."

Lincoln died at 7:22 am on April 15. Mary Lincoln was not present. In his last moments, Lincoln's face became calm and his breathing quieter. Field wrote there was "no apparent suffering, no convulsive action, no rattling of the throat ... nlya mere cessation of breathing". According to Lincoln's secretary

Booth had assigned Lewis Powell to kill Secretary of State William H. Seward. On the night of the assassination, Seward was at his home on Lafayette Square, confined to bed and recovering from injuries sustained on April 5 from being thrown from his carriage. Herold guided Powell to Seward's house. Powell carried an 1858 Whitney

Booth had assigned Lewis Powell to kill Secretary of State William H. Seward. On the night of the assassination, Seward was at his home on Lafayette Square, confined to bed and recovering from injuries sustained on April 5 from being thrown from his carriage. Herold guided Powell to Seward's house. Powell carried an 1858 Whitney

Lincoln was mourned in both the North and South,

and indeed around the world. Numerous foreign governments issued proclamations and declared periods of mourning on April 15. Lincoln was praised in sermons on

Lincoln was mourned in both the North and South,

and indeed around the world. Numerous foreign governments issued proclamations and declared periods of mourning on April 15. Lincoln was praised in sermons on

Within half an hour of fleeing Ford's Theatre, Booth crossed the Navy Yard Bridge into Maryland. A Union Army sentry named Silas Cobb questioned him about his late-night travel; Booth said that he was going home to the nearby town of Charles. Although it was forbidden for civilians to cross the bridge after 9 pm, the sentry let him through. Herold made it across the same bridge less than one hour later and rendezvoused with Booth. After retrieving weapons and supplies previously stored at Surattsville, Herold and Booth rode to the home of Samuel A. Mudd, a local doctor, who splinted the leg Booth had broken in his escape and later made a pair of crutches for Booth.

After one day at Mudd's house, Booth and Herold hired a local man to guide them to Samuel Cox's house. Cox, in turn, took them to Thomas Jones, a Confederate sympathizer who hid Booth and Herold in Zekiah Swamp for five days until they could cross the

Within half an hour of fleeing Ford's Theatre, Booth crossed the Navy Yard Bridge into Maryland. A Union Army sentry named Silas Cobb questioned him about his late-night travel; Booth said that he was going home to the nearby town of Charles. Although it was forbidden for civilians to cross the bridge after 9 pm, the sentry let him through. Herold made it across the same bridge less than one hour later and rendezvoused with Booth. After retrieving weapons and supplies previously stored at Surattsville, Herold and Booth rode to the home of Samuel A. Mudd, a local doctor, who splinted the leg Booth had broken in his escape and later made a pair of crutches for Booth.

After one day at Mudd's house, Booth and Herold hired a local man to guide them to Samuel Cox's house. Cox, in turn, took them to Thomas Jones, a Confederate sympathizer who hid Booth and Herold in Zekiah Swamp for five days until they could cross the  Sergeant Boston Corbett crept up behind the barn and shot Booth in "the back of the head about an inch below the spot where his ooth'sshot had entered the head of Mr. Lincoln", severing his spinal cord. Booth was carried out onto the steps of the barn. A soldier poured water into his mouth, which he spat out, unable to swallow. Booth told the soldier, "Tell my mother I die for my country." Unable to move his limbs, he asked a soldier to lift his hands before his face and whispered his last words as he gazed at them: "Useless ... useless." He died on the porch of the Garrett farm three hours later. Corbett was initially arrested for disobeying orders from Stanton that Booth be taken alive if possible, but was later released and was largely considered a hero by the media and the public.

Sergeant Boston Corbett crept up behind the barn and shot Booth in "the back of the head about an inch below the spot where his ooth'sshot had entered the head of Mr. Lincoln", severing his spinal cord. Booth was carried out onto the steps of the barn. A soldier poured water into his mouth, which he spat out, unable to swallow. Booth told the soldier, "Tell my mother I die for my country." Unable to move his limbs, he asked a soldier to lift his hands before his face and whispered his last words as he gazed at them: "Useless ... useless." He died on the porch of the Garrett farm three hours later. Corbett was initially arrested for disobeying orders from Stanton that Booth be taken alive if possible, but was later released and was largely considered a hero by the media and the public.

The seven-week trial included the testimony of 366 witnesses. All of the defendants were found guilty on June 30. Mary Surratt, Lewis Powell, David Herold, and George Atzerodt were sentenced to death by

The seven-week trial included the testimony of 366 witnesses. All of the defendants were found guilty on June 30. Mary Surratt, Lewis Powell, David Herold, and George Atzerodt were sentenced to death by

Biography of Mary Surratt, Lincoln Assassination Conspirator

", University of Missouri–Kansas City. Retrieved December 10, 2006. O'Laughlen died in prison in 1867. Mudd, Arnold, and Spangler were pardoned in February 1869 by Johnson. Spangler, who died in 1875, always insisted his sole connection to the plot was that Booth asked him to hold his horse. John Surratt stood trial in a civil court in Washington in 1867. Four residents of

Review

* King, Benjamin. ''A Bullet for Lincoln'', Pelican Publishing, 1993. * Lattimer, John. ''Kennedy and Lincoln, Medical & Ballistic Comparisons of Their Assassinations''. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, New York. 1980. ncludes description and pictures of Seward's jaw splint, not a neck brace* Steers Jr., Edward, and Holzer, Harold, eds. ''The Lincoln Assassination Conspirators: Their Confinement and Execution, as Recorded in the Letterbook of John Frederick Hartranft''. Louisiana State University Press, 2009. * Steers Jr., Edward. ''Lincoln's Assassination''. Southern Illinois University Press, 2025. Concise Lincoln Library.

Donald E. Wilkes, Jr.

* ''The Lincoln Memorial: A Record of the Life, Assassination, and Obsequies of the Martyred President'', New York: Bunce & Huntington, 1865. This is a collection of essays, accounts, sermons, newspaper reports, poems, and more, with no editor or authors named, except Richard Henry Stoddard, whose poem "Abraham Lincoln—An Horatian Ode" is included at pages 273–278.

Abraham Lincoln's Physician's Observation and Postmortem Reports: Original Documentation

Shapell Manuscript Foundation

First Responder Dr. Charles Leale Eyewitness Report of Assassination

Shapell Manuscript Foundation

Abraham Lincoln: A Resource Guide from the Library of Congress

The Men Who Killed Lincoln

nbsp;– slideshow by '' Life magazine''

Dr. Samuel A. Mudd Research Site

The official transcript of the trial (as recorded by Benn Pitman and several assistants – originally published in 1865 by the United States Army Military Commission)

Hanging the Lincoln Conspirators

– detailed analysis and review of historic 1865 photograph {{DEFAULTSORT:Lincoln, Abraham, Assassination 1865 in American politics 1865 in Washington, D.C. 1865 murders in the United States April 1865 Deaths by person in Washington, D.C. Events that led to courts-martial Murder in Washington, D.C. Political violence in the United States Politics of the American Civil War Washington, D.C., in the American Civil War Assassinations in the United States Crimes adapted into films

Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln (February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was the 16th president of the United States, serving from 1861 until Assassination of Abraham Lincoln, his assassination in 1865. He led the United States through the American Civil War ...

, the 16th president of the United States

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States. The president directs the Federal government of the United States#Executive branch, executive branch of the Federal government of t ...

, was shot by John Wilkes Booth

John Wilkes Booth (May 10, 1838April 26, 1865) was an American stage actor who Assassination of Abraham Lincoln, assassinated United States president Abraham Lincoln at Ford's Theatre in Washington, D.C., on April 14, 1865. A member of the p ...

while attending the play '' Our American Cousin'' at Ford's Theatre in Washington, D.C. Shot in the head as he watched the play, Lincoln died of his wounds the following day at 7:22 a.m. in the Petersen House opposite the theater. He was the first U.S. president to be assassinated. His funeral and burial were marked by an extended period of national mourning.

Near the end of the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and the Confederate States of A ...

, Lincoln's assassination

Assassination is the willful killing, by a sudden, secret, or planned attack, of a personespecially if prominent or important. It may be prompted by political, ideological, religious, financial, or military motives.

Assassinations are orde ...

was part of a larger political conspiracy intended by Booth to revive the Confederate cause by eliminating the three most important officials of the federal government

A federation (also called a federal state) is an entity characterized by a political union, union of partially federated state, self-governing provinces, states, or other regions under a #Federal governments, federal government (federalism) ...

. Conspirators Lewis Powell and David Herold

David Edgar Herold (June 16, 1842 – July 7, 1865) was an American pharmacist's assistant and accomplice of John Wilkes Booth in the assassination of Abraham Lincoln on April 14, 1865. After the shooting, Herold accompanied Booth to the home o ...

were assigned to kill Secretary of State William H. Seward, and George Atzerodt was tasked with killing Vice President

A vice president or vice-president, also director in British English, is an officer in government or business who is below the president (chief executive officer) in rank. It can also refer to executive vice presidents, signifying that the vi ...

Andrew Johnson

Andrew Johnson (December 29, 1808July 31, 1875) was the 17th president of the United States, serving from 1865 to 1869. The 16th vice president, he assumed the presidency following the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. Johnson was a South ...

.

Beyond Lincoln's death, the plot failed: Seward was only wounded, and Johnson's would-be attacker became drunk instead of killing the vice president. After a dramatic initial escape, Booth was killed at the end of a 12-day chase. Powell, Herold, Atzerodt, and Mary Surratt were later hanged for their roles in the conspiracy.

Background

Abandoned plan to kidnap Lincoln

John Wilkes Booth, born in

John Wilkes Booth, born in Maryland

Maryland ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It borders the states of Virginia to its south, West Virginia to its west, Pennsylvania to its north, and Delaware to its east ...

into a family of prominent stage actors, had by the time of the assassination become a famous actor and national celebrity in his own right. He was also an outspoken Confederate sympathizer; in late 1860 he was initiated in the pro-Confederate Knights of the Golden Circle

The Knights of the Golden Circle (KGC) was a secret society founded in 1854 by American George W. L. Bickley, the objective of which was to create a new country known as the Golden Circle (), where slavery would be legal. The country would have ...

in Baltimore

Baltimore is the most populous city in the U.S. state of Maryland. With a population of 585,708 at the 2020 census and estimated at 568,271 in 2024, it is the 30th-most populous U.S. city. The Baltimore metropolitan area is the 20th-large ...

, Maryland.

In May 1863, the Confederate States Congress passed a law prohibiting the exchange of black soldiers, following a previous decree by President Jefferson Davis

Jefferson F. Davis (June 3, 1808December 6, 1889) was an American politician who served as the only President of the Confederate States of America, president of the Confederate States from 1861 to 1865. He represented Mississippi in the Unite ...

in December 1862 that neither black soldiers nor their white officers would be exchanged. This became a reality in mid-July 1863 after some soldiers of the 54th Massachusetts

The 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment is an infantry regiment that saw extensive service in the Union Army during the American Civil War. The unit was the second African-American regiment, following the 1st Kansas Colored Volunteer Infantry ...

were not exchanged following their assault on Fort Wagner. On July 30, 1863, President Abraham Lincoln issued General Order 252 to stop prisoner exchanges with the South until all Northern soldiers would be exchanged without regard for their skin color. Stopping the prisoner exchanges is often wrongly attributed to General Grant, even though he was commanding an army in the west in mid-1863 and became overall commander in early 1864.

Booth conceived a plan to kidnap Lincoln in order to blackmail

Blackmail is a criminal act of coercion using a threat.

As a criminal offense, blackmail is defined in various ways in common law jurisdictions. In the United States, blackmail is generally defined as a crime of information, involving a thr ...

the Union into resuming prisoner exchanges, and he recruited Samuel Arnold, George Atzerodt, David Herold

David Edgar Herold (June 16, 1842 – July 7, 1865) was an American pharmacist's assistant and accomplice of John Wilkes Booth in the assassination of Abraham Lincoln on April 14, 1865. After the shooting, Herold accompanied Booth to the home o ...

, Michael O'Laughlen, Lewis Powell (also known as "Lewis Paine"), and John Surratt

John Harrison Surratt Jr. (April 13, 1844 – April 21, 1916) was an American Confederate States of America , Confederate spy who was accused of plotting with John Wilkes Booth to kidnap U.S. President Abraham Lincoln; he was also suspected of ...

to help him. Surratt's mother, Mary Surratt, left her tavern in Surrattsville, Maryland, and moved to a house in Washington, D.C., where Booth became a frequent visitor.

Booth and Lincoln were not personally acquainted, but Lincoln had seen Booth at Ford's Theatre in 1863. After the assassination, actor Frank Mordaunt wrote that Lincoln, who apparently harbored no suspicions about Booth, admired the actor and had repeatedly but unsuccessfully invited him to visit the

Booth and Lincoln were not personally acquainted, but Lincoln had seen Booth at Ford's Theatre in 1863. After the assassination, actor Frank Mordaunt wrote that Lincoln, who apparently harbored no suspicions about Booth, admired the actor and had repeatedly but unsuccessfully invited him to visit the White House

The White House is the official residence and workplace of the president of the United States. Located at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue Northwest (Washington, D.C.), NW in Washington, D.C., it has served as the residence of every U.S. president ...

. Booth attended Lincoln's second inauguration on March 4, 1865, writing in his diary afterwards: "What an excellent chance I had, if I wished, to kill the President on Inauguration day!"

On March 17, Booth and the other conspirators planned to abduct Lincoln as he returned from a play at Campbell General Hospital in northwest Washington. Lincoln did not go to the play, however, instead attending a ceremony at the National Hotel. Booth was living at the National Hotel at the time and, had he not gone to the hospital for the abortive kidnap attempt, might have been able to attack Lincoln at the hotel.

Meanwhile, the Confederacy was collapsing. On April 3, Richmond, Virginia

Richmond ( ) is the List of capitals in the United States, capital city of the Commonwealth (U.S. state), U.S. commonwealth of Virginia. Incorporated in 1742, Richmond has been an independent city (United States), independent city since 1871. ...

, the Confederate capital, fell to the Union Army. On April 9, General

A general officer is an Officer (armed forces), officer of high rank in the army, armies, and in some nations' air force, air and space forces, marines or naval infantry.

In some usages, the term "general officer" refers to a rank above colone ...

Robert E. Lee

Robert Edward Lee (January 19, 1807 – October 12, 1870) was a general officers in the Confederate States Army, Confederate general during the American Civil War, who was appointed the General in Chief of the Armies of the Confederate ...

and his Army of Northern Virginia

The Army of Northern Virginia was a field army of the Confederate States Army in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War. It was also the primary command structure of the Department of Northern Virginia. It was most often arrayed agains ...

surrendered to General

A general officer is an Officer (armed forces), officer of high rank in the army, armies, and in some nations' air force, air and space forces, marines or naval infantry.

In some usages, the term "general officer" refers to a rank above colone ...

Ulysses S. Grant and his Army of the Potomac after the Battle of Appomattox Court House. Confederate President Jefferson Davis and other Confederate officials had fled. Nevertheless, Booth continued to believe in the Confederate cause and sought a way to salvage it; he soon decided to assassinate Lincoln.

Motive

There are various theories about Booth's motivations. In a letter to his mother, he wrote of his desire to avenge the South. Doris Kearns Goodwin has endorsed the idea that another factor was Booth's rivalry with his well-known older brother, actorEdwin Booth

Edwin Thomas Booth (November 13, 1833 – June 7, 1893) was an American stage actor and theatrical manager who toured throughout the United States and the major capitals of Europe, performing Shakespearean plays. In 1869, he founded Booth's Th ...

, who was a loyal Unionist. David S. Reynolds believes that, though disagreeing with his cause, Booth greatly admired the daring of abolitionist

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the political movement to end slavery and liberate enslaved individuals around the world.

The first country to fully outlaw slavery was Kingdom of France, France in 1315, but it was later used ...

John Brown; Booth's sister Asia Booth Clarke

Asia Frigga Booth Clarke (November 19, 1835 – May 16, 1888) was a 19th-century American writer.

Early years

Asia Frigga Booth was the eighth in Booth family, the family of ten children born to Junius Brutus Booth and his wife Mary Ann Holmes. ...

quoted him as saying, "John Brown was a man inspired, the grandest character of the century!"

On April 11, Booth attended Lincoln's last speech, in which Lincoln promoted voting rights for emancipated slaves; Booth said, "That means nigger

In the English language, ''nigger'' is a racial slur directed at black people. Starting in the 1990s, references to ''nigger'' have been increasingly replaced by the euphemistic contraction , notably in cases where ''nigger'' is Use–menti ...

citizenship.... That is the last speech he will ever give." Enraged, Booth urged Powell to shoot Lincoln on the spot. Whether Booth made this request because he was not armed or considered Powell a better shot than himself (Powell, unlike Booth, had served in the Confederate Army and thus had military experience) is unknown. In any event, Powell refused for fear of the crowd, and Booth was either unable or unwilling to personally attempt to kill the president. However, Booth said to David Herold, "By God, I'll put him through."

Lincoln's premonitions

According to Ward Hill Lamon, three days before his death, Lincoln related a dream in which he wandered the White House searching for the source of mournful sounds: However, Lincoln later told Lamon that "In this dream it was not me, but some other fellow, that was killed. It seems that this ghostly assassin tried his hand on someone else." Paranormal investigator Joe Nickell wrote that dreams of assassination would not be unexpected, considering the Baltimore Plot and an additional assassination attempt in which a hole was shot through Lincoln's hat. For months, Lincoln had looked pale and haggard, but on the morning of the assassination he told people how happy he was. First Lady Mary Lincoln felt such talk could bring bad luck. Lincoln told his cabinet that he had dreamed of being on a "singular and indescribable vessel that was moving with great rapidity toward a dark and indefinite shore", and that he had had the same dream before "nearly every great and important event of the War" such as the Union victories at Antietam, Murfreesboro, Gettysburg, and Vicksburg.Preparations

On April 14, Booth's morning started at midnight. He wrote his mother that all was well but that he was "in haste". In his diary, he wrote that "Our cause being almost lost, something ''decisive'' and great must be done".

While visiting Ford's Theatre around noon to pick up his mail, Booth learned that Lincoln and Grant were to visit the theater that evening for a performance of ''Our American Cousin''. This provided him with an especially good opportunity to attack Lincoln since, having performed there several times, he knew the theater's layout and was familiar to its staff. Booth went to Mary Surratt's

On April 14, Booth's morning started at midnight. He wrote his mother that all was well but that he was "in haste". In his diary, he wrote that "Our cause being almost lost, something ''decisive'' and great must be done".

While visiting Ford's Theatre around noon to pick up his mail, Booth learned that Lincoln and Grant were to visit the theater that evening for a performance of ''Our American Cousin''. This provided him with an especially good opportunity to attack Lincoln since, having performed there several times, he knew the theater's layout and was familiar to its staff. Booth went to Mary Surratt's boarding house

A boarding house is a house (frequently a family home) in which lodging, lodgers renting, rent one or more rooms on a nightly basis and sometimes for extended periods of weeks, months, or years. The common parts of the house are maintained, and ...

in Washington, D.C., and asked her to deliver a package to her tavern in Surrattsville, Maryland. He also asked her to tell her tenant Louis J. Weichmann to ready the guns and ammunition that Booth had previously stored at the tavern.

The conspirators met for the final time at 8:45pm. Booth assigned Powell to kill Secretary of State William H. Seward at his home, Atzerodt to kill

The conspirators met for the final time at 8:45pm. Booth assigned Powell to kill Secretary of State William H. Seward at his home, Atzerodt to kill Vice President

A vice president or vice-president, also director in British English, is an officer in government or business who is below the president (chief executive officer) in rank. It can also refer to executive vice presidents, signifying that the vi ...

Andrew Johnson

Andrew Johnson (December 29, 1808July 31, 1875) was the 17th president of the United States, serving from 1865 to 1869. The 16th vice president, he assumed the presidency following the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. Johnson was a South ...

at the Kirkwood Hotel, and Herold to guide Powell (who was unfamiliar with Washington) to the Seward house and then to a rendezvous with Booth in Maryland.

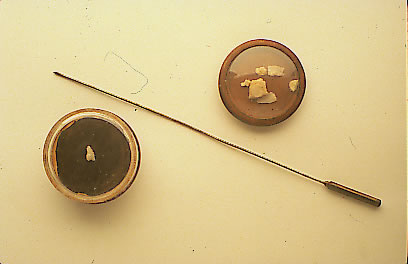

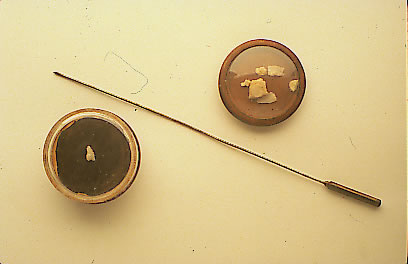

Booth was the only well-known member of the conspiracy. Access to the theater's upper floor containing the Presidential Box was restricted, and Booth was the only plotter who could have realistically expected to be admitted there without difficulty. Furthermore, it would have been reasonable (but ultimately incorrect) for the plotters to have assumed that the entrance of the box would be guarded. Had it been, Booth would have been the only plotter with a plausible chance of gaining access to the President, or at least to gain entry to the box without being searched for weapons first. Booth planned to shoot Lincoln at point-blank range with his single-shot Philadelphia Deringer pistol

A pistol is a type of handgun, characterised by a gun barrel, barrel with an integral chamber (firearms), chamber. The word "pistol" derives from the Middle French ''pistolet'' (), meaning a small gun or knife, and first appeared in the Englis ...

and then stab Grant at the theater. They were all to strike simultaneously shortly after ten o'clock. Atzerodt tried to withdraw from the plot, which to this point had involved only kidnapping, not murder, but Booth pressured him to continue.

Assassination

Lincoln arrives at the theater

Despite what Booth had heard earlier in the day, Grant and his wife, Julia Grant, had declined to accompany the Lincolns, as Mary Lincoln and Julia Grant were not on good terms. Others in succession also declined the Lincolns' invitation, until finally

Despite what Booth had heard earlier in the day, Grant and his wife, Julia Grant, had declined to accompany the Lincolns, as Mary Lincoln and Julia Grant were not on good terms. Others in succession also declined the Lincolns' invitation, until finally Major

Major most commonly refers to:

* Major (rank), a military rank

* Academic major, an academic discipline to which an undergraduate student formally commits

* People named Major, including given names, surnames, nicknames

* Major and minor in musi ...

Henry Rathbone and his fiancée Clara Harris (daughter of U.S. Senator Ira Harris of New York) accepted. At one point, Mary developed a headache and was inclined to stay home, but Lincoln told her he must attend because newspapers had announced that he would. William H. Crook, one of Lincoln's bodyguards, advised him not to go, but Lincoln said he had promised his wife. Lincoln told Speaker of the House Schuyler Colfax

Schuyler Colfax Jr. ( ; March 23, 1823January 13, 1885) was an American journalist, businessman, and politician who served as the 17th vice president of the United States from 1869 to 1873, and prior to that as the 25th Speaker of the United Sta ...

, "I suppose it's time to go though I would rather stay" before assisting Mary into the carriage.

The presidential party arrived late and settled into their box, made from two adjoining boxes with a dividing partition removed. The play was interrupted, and the orchestra played " Hail to the Chief" as the full house of about 1,700 rose in applause. Lincoln sat in a rocking chair that had been selected for him from among the Ford family's personal furnishings.

The cast modified a line of the play in honor of Lincoln: when the heroine asked for a seat protected from the draft, the replyscripted as, "Well, you're not the only one that wants to escape the draft

Draft, the draft, or draught may refer to:

Watercraft dimensions

* Draft (hull), the distance from waterline to keel of a vessel

* Draft (sail), degree of curvature in a sail

* Air draft, distance from waterline to the highest point on a v ...

"was delivered instead as, "The draft has already been stopped by order of the President!" A member of the audience observed that Mary Lincoln often called her husband's attention to aspects of the action onstage, and "seemed to take great pleasure in witnessing his enjoyment".

At one point, Mary whispered to Lincoln, who was holding her hand, "What will Miss Harris think of my hanging on to you so?" Lincoln replied, "She won't think anything about it". In following years, these words were traditionally considered Lincoln's last, though N.W. Miner, a family friend, claimed in 1882 that Mary Lincoln told him that Lincoln's last words expressed a wish to visit Jerusalem

Jerusalem is a city in the Southern Levant, on a plateau in the Judaean Mountains between the Mediterranean Sea, Mediterranean and the Dead Sea. It is one of the List of oldest continuously inhabited cities, oldest cities in the world, and ...

.

Booth shoots Lincoln

Lincoln's usual protections were not in place that night at Ford's. Crook was on a second shift at the White House, and Ward Hill Lamon, Lincoln's personal bodyguard, was away in Richmond on assignment from Lincoln. John Frederick Parker was assigned to guard the Presidential Box. At intermission he went to a nearby tavern along with Lincoln's valet, Charles Forbes, and Coachman Francis Burke. Booth had several drinks while waiting for his planned time. It is unclear whether Parker returned to the theater, but he was certainly not at his post when Booth entered the box. In any event, there is no certainty that entry would have been denied to a celebrity such as Booth. Booth had prepared a brace to bar the door after entering the box, indicating that he expected a guard. After spending time at the tavern, Booth entered Ford's Theatre one last time at about 10:10 pm, this time through the theater's front entrance. He passed through the dress circle and went to the door that led to the Presidential Box after showing Charles Forbes his calling card. Navy Surgeon George Brainerd Todd saw Booth arrive:

Once inside the hallway, Booth

Lincoln's usual protections were not in place that night at Ford's. Crook was on a second shift at the White House, and Ward Hill Lamon, Lincoln's personal bodyguard, was away in Richmond on assignment from Lincoln. John Frederick Parker was assigned to guard the Presidential Box. At intermission he went to a nearby tavern along with Lincoln's valet, Charles Forbes, and Coachman Francis Burke. Booth had several drinks while waiting for his planned time. It is unclear whether Parker returned to the theater, but he was certainly not at his post when Booth entered the box. In any event, there is no certainty that entry would have been denied to a celebrity such as Booth. Booth had prepared a brace to bar the door after entering the box, indicating that he expected a guard. After spending time at the tavern, Booth entered Ford's Theatre one last time at about 10:10 pm, this time through the theater's front entrance. He passed through the dress circle and went to the door that led to the Presidential Box after showing Charles Forbes his calling card. Navy Surgeon George Brainerd Todd saw Booth arrive:

Once inside the hallway, Booth barricade

Barricade (from the French ''barrique'' - 'barrel') is any object or structure that creates a barrier or obstacle to control, block passage or force the flow of traffic in the desired direction. Adopted as a military term, a barricade denotes ...

d the door by wedging a stick between it and the wall. From here, a second door led to Lincoln's box. Evidence shows that, earlier in the day, Booth had bored a peephole in this second door.

Booth knew the play ''Our American Cousin'', and waited to time his shot at about 10:15 pm, with the laughter at one of the lines of the play, delivered by actor Harry Hawk: "Well, I guess I know enough to turn you inside out, old gal; you sockdologizing old man-trap!" Lincoln was laughing at this line

when Booth opened the door, stepped forward, and shot him from behind with his pistol.

The bullet entered Lincoln's skull behind his left ear, passed through his brain, and came to rest near the front of the skull after fracturing both orbital plates. Lincoln slumped over in his chair and then fell backward. Rathbone turned to see Booth standing in gunsmoke less than four feet behind Lincoln; Booth shouted a word that Rathbone thought sounded like "Freedom!"

Booth escapes

Rathbone jumped from his seat and struggled with Booth, who dropped the pistol and drew a dagger with which he stabbed Rathbone in the left forearm. Rathbone again grabbed at Booth as he prepared to jump from the box to the stage, a twelve-foot drop;''Lincoln Assassination'', History Channel Booth's riding spur became entangled on the Treasury flag decorating the box, and he landed awkwardly on his left foot. As he began crossing the stage, many in the audience thought he was part of the play. Booth held his bloody knife over his head and yelled something to the audience. While it is traditionally held that Booth shouted theVirginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic regions of the United States between the East Coast of the United States ...

state motto, '' Sic semper tyrannis!'' ("Thus always to tyrants") either from the box or the stage, witness accounts conflict. Most recalled hearing ''Sic semper tyrannis!'' but othersincluding Booth himselfsaid he yelled only ''Sic semper!'' Some did not recall Booth saying anything in Latin. There is similar uncertainty about what Booth shouted next, in English: either "The South is avenged!", "Revenge for the South!", or "The South shall be free!" Two witnesses remembered Booth's words as: "I have done it!"

Immediately after Booth landed on the stage, Major Joseph B. Stewart climbed over the orchestra pit and footlights and pursued Booth across the stage. The screams of Mary Lincoln and Clara Harris, and Rathbone's cries of, "Stop that man!" prompted others to join the chase as pandemonium broke out.

Booth exited the theater through a side door, and on the way stabbing orchestra leader William Withers Jr.

As he leapt into the saddle of his getaway horse Booth pushed away Joseph Burroughs, who had been holding the horse, striking Burroughs with the handle of his knife.

Death of Lincoln

Charles Leale, a young Union Army surgeon, pushed through the crowd to the door of the Presidential Box, but could not open it until Rathbone, inside, noticed and removed the wooden brace with which Booth had jammed the door shut. Leale found Lincoln seated with his head leaning to his right as Mary held him and sobbed. "His eyes were closed and he was in a profoundlycoma

A coma is a deep state of prolonged unconsciousness in which a person cannot be awakened, fails to Nociception, respond normally to Pain, painful stimuli, light, or sound, lacks a normal Circadian rhythm, sleep-wake cycle and does not initiate ...

tose condition, while his breathing was intermittent and exceedingly stertorous." Thinking Lincoln had been stabbed, Leale shifted him to the floor. Meanwhile, another physician, Charles Sabin Taft, was lifted into the box from the stage.

After Leale and bystander William Kent cut away Lincoln's collar while unbuttoning his coat and shirt and found no stab wound, Leale located the gunshot wound behind the left ear. He found the bullet too deep to be removed but dislodged a blood clot, after which Lincoln's breathing improved; he learned that regularly removing new clots maintained Lincoln's breathing. After giving Lincoln artificial respiration, Leale allowed actress Laura Keene to cradle the President's head in her lap. He pronounced the wound mortal.

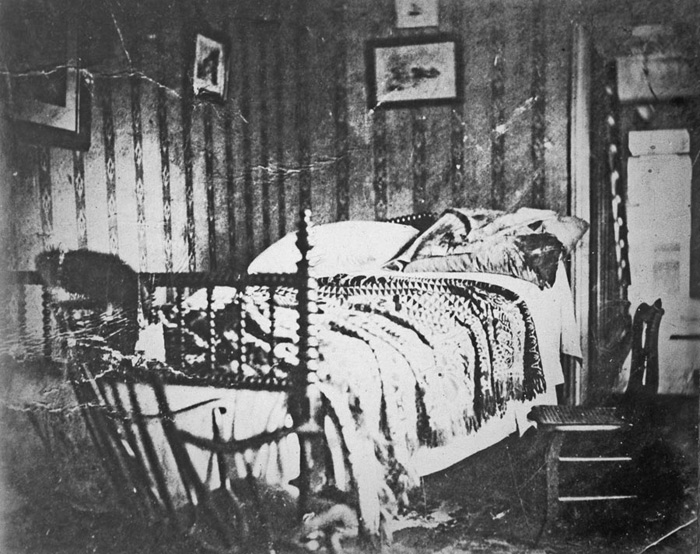

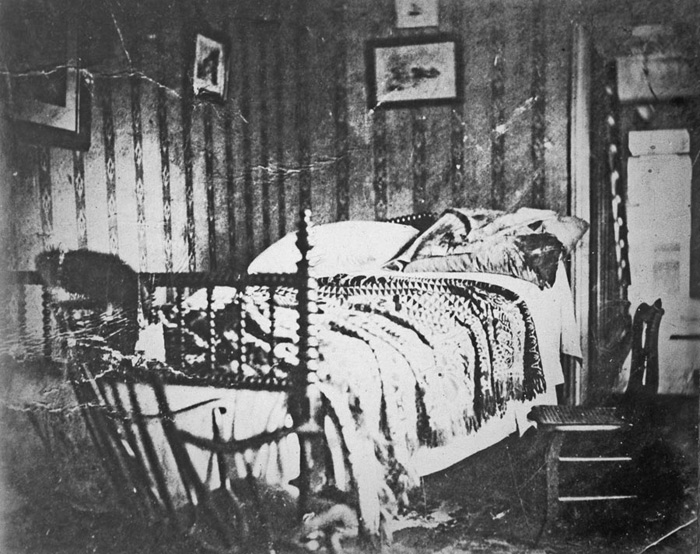

Leale, Taft, and another doctor, Albert King, decided that Lincoln must be moved to the nearest house on Tenth Street because a carriage ride to the White House was too dangerous. Carefully, seven men picked up Lincoln and slowly carried him out of the theater, which was packed with an angry mob. After considering Peter Taltavull's Star Saloon next door, they concluded that they would take Lincoln to one of the houses across the way. It was raining as soldiers carried Lincoln into the street, where a man urged them toward the house of tailor William Petersen. In Petersen's first-floor bedroom, the exceptionally tall Lincoln was laid diagonally on a small bed.

After clearing everyone out of the room, including Mrs. Lincoln, the doctors cut away Lincoln's clothes but discovered no other wounds. Finding that Lincoln was cold, they applied hot water bottles and mustard plasters while covering him with blankets. Later, more physicians arrived: Surgeon General Joseph K. Barnes, Charles Henry Crane, and Robert K. Stone (Lincoln's personal physician).

All agreed Lincoln could not survive. Barnes probed the wound, locating the bullet and some bone fragments. Throughout the night, as the hemorrhage continued, they removed blood clots to relieve pressure on the brain, and Leale held the comatose president's hand with a firm grip, "to let him know that he was in touch with humanity and had a friend".

All agreed Lincoln could not survive. Barnes probed the wound, locating the bullet and some bone fragments. Throughout the night, as the hemorrhage continued, they removed blood clots to relieve pressure on the brain, and Leale held the comatose president's hand with a firm grip, "to let him know that he was in touch with humanity and had a friend".

Lincoln's older son Robert Todd Lincoln arrived at about 11 pm, but twelve-year-old Tad Lincoln, who was watching a play of ''

Lincoln's older son Robert Todd Lincoln arrived at about 11 pm, but twelve-year-old Tad Lincoln, who was watching a play of ''Aladdin

Aladdin ( ; , , ATU 561, 'Aladdin') is a Middle-Eastern folk tale. It is one of the best-known tales associated with '' One Thousand and One Nights'' (often known in English as ''The Arabian Nights''), despite not being part of the original ...

'' at Grover's Theater when he learned of his father's assassination, was kept away. Secretary of the Navy

The Secretary of the Navy (SECNAV) is a statutory officer () and the head (chief executive officer) of the Department of the Navy, a military department within the United States Department of Defense. On March 25, 2025, John Phelan was confirm ...

Gideon Welles and Secretary of War

The secretary of war was a member of the U.S. president's Cabinet, beginning with George Washington's administration. A similar position, called either "Secretary at War" or "Secretary of War", had been appointed to serve the Congress of the ...

Edwin M. Stanton arrived. Stanton insisted that the sobbing Mrs. Lincoln leave the sick room, then for the rest of the night he essentially ran the United States government from the house, including directing the hunt for Booth and the other conspirators. Guards kept the public away, but numerous officials and physicians were admitted to pay their respects.

Initially, Lincoln's features were calm and his breathing slow and steady. Later, one of his eyes became swollen and the right side of his face discolored. Maunsell Bradhurst Field wrote in a letter to ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''NYT'') is an American daily newspaper based in New York City. ''The New York Times'' covers domestic, national, and international news, and publishes opinion pieces, investigative reports, and reviews. As one of ...

'' that Lincoln then started "breathing regularly, but with effort, and did not seem to be struggling or suffering."  As he neared death, Lincoln's appearance became "perfectly natural" (except for the discoloration around his eyes). Shortly before 7am Mary was allowed to return to Lincoln's side, and, as Dixon reported, "she again seated herself by the President, kissing him and calling him every endearing name."

Lincoln died at 7:22 am on April 15. Mary Lincoln was not present. In his last moments, Lincoln's face became calm and his breathing quieter. Field wrote there was "no apparent suffering, no convulsive action, no rattling of the throat ... nlya mere cessation of breathing". According to Lincoln's secretary

As he neared death, Lincoln's appearance became "perfectly natural" (except for the discoloration around his eyes). Shortly before 7am Mary was allowed to return to Lincoln's side, and, as Dixon reported, "she again seated herself by the President, kissing him and calling him every endearing name."

Lincoln died at 7:22 am on April 15. Mary Lincoln was not present. In his last moments, Lincoln's face became calm and his breathing quieter. Field wrote there was "no apparent suffering, no convulsive action, no rattling of the throat ... nlya mere cessation of breathing". According to Lincoln's secretary John Hay

John Milton Hay (October 8, 1838July 1, 1905) was an American statesman and official whose career in government stretched over almost half a century. Beginning as a Secretary to the President of the United States, private secretary for Abraha ...

, at the moment of Lincoln's death, "a look of unspeakable peace came upon his worn features". The assembly knelt for a prayer, after which Stanton said either, "Now he belongs to the ages" or, "Now he belongs to the angels."

On Lincoln's death, Vice President Johnson became the 17th president of the United States. The presidential oath of office was administered to Johnson by Chief Justice Salmon Chase sometime between 10 and 11am.

Powell attacks Seward

Booth had assigned Lewis Powell to kill Secretary of State William H. Seward. On the night of the assassination, Seward was at his home on Lafayette Square, confined to bed and recovering from injuries sustained on April 5 from being thrown from his carriage. Herold guided Powell to Seward's house. Powell carried an 1858 Whitney

Booth had assigned Lewis Powell to kill Secretary of State William H. Seward. On the night of the assassination, Seward was at his home on Lafayette Square, confined to bed and recovering from injuries sustained on April 5 from being thrown from his carriage. Herold guided Powell to Seward's house. Powell carried an 1858 Whitney revolver

A revolver is a repeating handgun with at least one barrel and a revolving cylinder containing multiple chambers (each holding a single cartridge) for firing. Because most revolver models hold six cartridges before needing to be reloaded, ...

(a large, heavy, and popular gun during the Civil War) and a Bowie knife.

William Bell, Seward's maître d', answered the door when Powell knocked at 10:10pm, as Booth made his way to the Presidential Box at Ford's Theater. Powell told Bell that he had medicine from Seward's physician and that his instructions were to personally show Seward how to take it. Overcoming Bell's skepticism, Powell made his way up the stairs to Seward's third-floor bedroom. At the top of the staircase he was stopped by Seward's son, Assistant Secretary of State Frederick W. Seward, to whom he repeated the medicine story; Frederick, suspicious, said his father was asleep.

Hearing voices, Seward's daughter Fanny emerged from Seward's room and said, "Fred, Father is awake now"thus revealing to Powell where Seward was. Powell turned as if to start downstairs but suddenly turned again and drew his revolver. He aimed at Frederick's forehead and pulled the trigger, but the gun misfired, so he bludgeoned Frederick unconscious with it. Bell, yelling "Murder! Murder!", ran outside for help.

Fanny opened the door again, and Powell shoved past her to Seward's bed. He stabbed at Seward's face and neck, slicing open his cheek. However, the splint (often mistakenly described as a neck brace) that doctors had fitted to Seward's broken jaw prevented the blade from penetrating his jugular vein. Seward eventually recovered, though with serious scars on his face.

Seward's son Augustus

Gaius Julius Caesar Augustus (born Gaius Octavius; 23 September 63 BC – 19 August AD 14), also known as Octavian (), was the founder of the Roman Empire, who reigned as the first Roman emperor from 27 BC until his death in A ...

and Sergeant George F. Robinson, a soldier assigned to Seward, were alerted by Fanny's screams and received stab wounds in struggling with Powell. As Augustus went for a pistol, Powell ran downstairs toward the door, where he encountered Emerick Hansell, a State Department

The United States Department of State (DOS), or simply the State Department, is an executive department of the U.S. federal government responsible for the country's foreign policy and relations. Equivalent to the ministry of foreign affairs o ...

messenger. Powell stabbed Hansell in the back, then ran outside exclaiming, "I'm mad! I'm mad!" Screams from the house had frightened Herold, who ran off, leaving Powell to find his own way in an unfamiliar city.

Atzerodt fails to attack Johnson

Booth had assigned George Atzerodt to kill Vice President Andrew Johnson, who was staying at the Kirkwood House in Washington. Atzerodt was to go to Johnson's room at 10:15 pm and shoot him. On April 14, Atzerodt rented the room directly above Johnson's; the next day, he arrived there at the appointed time and, carrying a gun and knife, went to the bar downstairs, where he asked the bartender about Johnson's character and behavior. He eventually became drunk and wandered off through the streets, tossing his knife away at some point. He made his way to the Pennsylvania House Hotel by 2 am, where he obtained a room and went to sleep. Earlier in the day, Booth had stopped by the Kirkwood House and left a note for Johnson: "Don't wish to disturb you. Are you at home? J. Wilkes Booth." One theory is that Booth was trying to find out whether Johnson was expected at the Kirkwood that night; another holds that Booth, concerned that Atzerodt would fail to kill Johnson, intended the note to implicate Johnson in the conspiracy.Reactions

Lincoln was mourned in both the North and South,

and indeed around the world. Numerous foreign governments issued proclamations and declared periods of mourning on April 15. Lincoln was praised in sermons on

Lincoln was mourned in both the North and South,

and indeed around the world. Numerous foreign governments issued proclamations and declared periods of mourning on April 15. Lincoln was praised in sermons on Easter Sunday

Easter, also called Pascha (Aramaic: פַּסְחָא , ''paskha''; Greek language, Greek: πάσχα, ''páskha'') or Resurrection Sunday, is a Christian festival and cultural holiday commemorating the resurrection of Jesus from the dead, de ...

, which fell on the day after his death.

On April 18, mourners lined up seven deep for a mile to view Lincoln in his walnut casket in the White House's black-draped East Room. Special trains brought thousands from other cities, some of whom slept on the Capitol's lawn. Hundreds of thousands watched the funeral procession on April 19, and millions more lined the route of the train which took Lincoln's remains through New York to Springfield, Illinois

Illinois ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern United States. It borders on Lake Michigan to its northeast, the Mississippi River to its west, and the Wabash River, Wabash and Ohio River, Ohio rivers to its ...

, often passing trackside tributes in the form of bands, bonfires, and hymn-singing.

Poet Walt Whitman composed " When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom'd", "O Captain! My Captain!

"O Captain! My Captain!" is an extended metaphor poem written by Walt Whitman in 1865 about Assassination of Abraham Lincoln, the death of U.S. president Abraham Lincoln. Well received upon publication, the poem was Whitman's first to be Anth ...

", and two other poems, to eulogize Lincoln.

Ulysses S. Grant called Lincoln "incontestably the greatest man I ever knew". Robert E. Lee expressed sadness.Kunhardt III, Philip B., "Lincoln's Contested Legacy," ''Smithsonian'', pp. 34–35. Southern-born Elizabeth Blair said that "Those of Southern born sympathies know now they have lost a friend willing and more powerful to protect and serve them than they can now ever hope to find again." African-American orator Frederick Douglass called the assassination an "unspeakable calamity".

British Foreign Secretary Lord Russell called Lincoln's death a "sad calamity". China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. With population of China, a population exceeding 1.4 billion, it is the list of countries by population (United Nations), second-most populous country after ...

's chief secretary of state for foreign affairs, Prince Gong, described himself as "inexpressibly shocked and startled". Ecuador

Ecuador, officially the Republic of Ecuador, is a country in northwestern South America, bordered by Colombia on the north, Peru on the east and south, and the Pacific Ocean on the west. It also includes the Galápagos Province which contain ...

ian president Gabriel García Moreno said, "Never should I have thought that the noble country of Washington would be humiliated by such a black and horrible crime; nor should I ever have thought that Mr. Lincoln would come to such a horrible end, after having served his country with such wisdom and glory under such critical circumstances." The government of Liberia

Liberia, officially the Republic of Liberia, is a country on the West African coast. It is bordered by Sierra Leone to Liberia–Sierra Leone border, its northwest, Guinea to Guinea–Liberia border, its north, Ivory Coast to Ivory Coast–Lib ...

issued a proclamation calling Lincoln "not only the ruler of his own people, but a father to millions of a race stricken and oppressed". The government of Haiti

Haiti, officially the Republic of Haiti, is a country on the island of Hispaniola in the Caribbean Sea, east of Cuba and Jamaica, and south of the Bahamas. It occupies the western three-eighths of the island, which it shares with the Dominican ...

condemned the assassination as a "horrid crime".

Temperance movement activist and academic T. D. Bancroft was present at Lincoln's assassination. He later lectured widely on Lincoln's death, and wrote on the subject.

Flight and capture of the conspirators

Booth and Herold

Within half an hour of fleeing Ford's Theatre, Booth crossed the Navy Yard Bridge into Maryland. A Union Army sentry named Silas Cobb questioned him about his late-night travel; Booth said that he was going home to the nearby town of Charles. Although it was forbidden for civilians to cross the bridge after 9 pm, the sentry let him through. Herold made it across the same bridge less than one hour later and rendezvoused with Booth. After retrieving weapons and supplies previously stored at Surattsville, Herold and Booth rode to the home of Samuel A. Mudd, a local doctor, who splinted the leg Booth had broken in his escape and later made a pair of crutches for Booth.

After one day at Mudd's house, Booth and Herold hired a local man to guide them to Samuel Cox's house. Cox, in turn, took them to Thomas Jones, a Confederate sympathizer who hid Booth and Herold in Zekiah Swamp for five days until they could cross the

Within half an hour of fleeing Ford's Theatre, Booth crossed the Navy Yard Bridge into Maryland. A Union Army sentry named Silas Cobb questioned him about his late-night travel; Booth said that he was going home to the nearby town of Charles. Although it was forbidden for civilians to cross the bridge after 9 pm, the sentry let him through. Herold made it across the same bridge less than one hour later and rendezvoused with Booth. After retrieving weapons and supplies previously stored at Surattsville, Herold and Booth rode to the home of Samuel A. Mudd, a local doctor, who splinted the leg Booth had broken in his escape and later made a pair of crutches for Booth.

After one day at Mudd's house, Booth and Herold hired a local man to guide them to Samuel Cox's house. Cox, in turn, took them to Thomas Jones, a Confederate sympathizer who hid Booth and Herold in Zekiah Swamp for five days until they could cross the Potomac River

The Potomac River () is in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic region of the United States and flows from the Potomac Highlands in West Virginia to Chesapeake Bay in Maryland. It is long,U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography D ...

. On the afternoon of April 24, they arrived at the farm of Richard H. Garrett, a tobacco farmer, in King George County, Virginia

King George County is a county located in the Commonwealth of Virginia. As of the 2020 census, the population sits at 26,723. Its county seat is the census designated place of King George. The county's largest employer is the U.S. Naval S ...

. Booth told Garrett he was a wounded Confederate soldier.

An April 15 letter to Navy Surgeon George Brainerd Todd from his brother tells of the rumors in Washington about Booth:

The hunt for the conspirators quickly became the largest in U.S. history, involving thousands of federal troops and countless civilians. Edwin M. Stanton personally directed the operation, authorizing rewards of for Booth and $25,000 each for Herold and John Surratt.

Booth and Herold were sleeping at Garrett's farm on April 26 when soldiers from the 16th New York Cavalry arrived, surrounded the barn, and threatened to set fire to it. Herold surrendered, but Booth cried out, "I will not be taken alive!" The soldiers set fire to the barn and Booth scrambled for the back door with a rifle and pistol.

Sergeant Boston Corbett crept up behind the barn and shot Booth in "the back of the head about an inch below the spot where his ooth'sshot had entered the head of Mr. Lincoln", severing his spinal cord. Booth was carried out onto the steps of the barn. A soldier poured water into his mouth, which he spat out, unable to swallow. Booth told the soldier, "Tell my mother I die for my country." Unable to move his limbs, he asked a soldier to lift his hands before his face and whispered his last words as he gazed at them: "Useless ... useless." He died on the porch of the Garrett farm three hours later. Corbett was initially arrested for disobeying orders from Stanton that Booth be taken alive if possible, but was later released and was largely considered a hero by the media and the public.

Sergeant Boston Corbett crept up behind the barn and shot Booth in "the back of the head about an inch below the spot where his ooth'sshot had entered the head of Mr. Lincoln", severing his spinal cord. Booth was carried out onto the steps of the barn. A soldier poured water into his mouth, which he spat out, unable to swallow. Booth told the soldier, "Tell my mother I die for my country." Unable to move his limbs, he asked a soldier to lift his hands before his face and whispered his last words as he gazed at them: "Useless ... useless." He died on the porch of the Garrett farm three hours later. Corbett was initially arrested for disobeying orders from Stanton that Booth be taken alive if possible, but was later released and was largely considered a hero by the media and the public.

Others

Without Herold to guide him, Powell did not find his way back to the Surratt house until April 17. He told detectives waiting there that he was a ditch-digger hired by Mary Surratt, but she denied knowing him. Both were arrested. George Atzerodt hid at his cousin's farm inGermantown, Maryland

Germantown is an urbanized census-designated place in Montgomery County, Maryland, United States. With a population of 91,249 as of the 2020 census, it is the third-most populous community in Maryland, after Baltimore and Columbia, Maryland, Col ...

, about northwest of Washington, where he was arrested April 20.

The remaining conspirators were arrested by month's endexcept for John Surratt

John Harrison Surratt Jr. (April 13, 1844 – April 21, 1916) was an American Confederate States of America , Confederate spy who was accused of plotting with John Wilkes Booth to kidnap U.S. President Abraham Lincoln; he was also suspected of ...

, who fled to Quebec

Quebec is Canada's List of Canadian provinces and territories by area, largest province by area. Located in Central Canada, the province shares borders with the provinces of Ontario to the west, Newfoundland and Labrador to the northeast, ...

where Roman Catholic priests hid him. In September, he boarded a ship to Liverpool, England

Liverpool is a port city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. It is situated on the eastern side of the Mersey Estuary, near the Irish Sea, north-west of London. With a population of (in ), Liverpool is the administrative, c ...

, staying in the Catholic Church of the Holy Cross there. From there, he moved furtively through Europe until joining the Pontifical Zouaves in the Papal States

The Papal States ( ; ; ), officially the State of the Church, were a conglomeration of territories on the Italian peninsula under the direct sovereign rule of the pope from 756 to 1870. They were among the major states of Italy from the 8th c ...

. A friend from his school days recognized him there in early 1866 and alerted the U.S. government. Surratt was arrested by the Papal authorities but managed to escape under suspicious circumstances. He was finally captured by an agent of the United States in Egypt

Egypt ( , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the Northeast Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to northe ...

in November 1866.

Conspirators' trial and execution

Scores of people were arrested, including many tangential associates of the conspirators and anyone having had even the slightest contact with Booth or Herold during their flight. These included Louis J. Weichmann, a boarder in Mrs. Surratt's house; Booth's brother Junius (in Cincinnati at the time of the assassination); theater owner John T. Ford; James Pumphrey, from whom Booth hired his horse; John M. Lloyd, the innkeeper who rented Mrs. Surratt's Maryland tavern and gave Booth and Herold weapons and supplies the night of April 14; and Samuel Cox and Thomas A. Jones, who helped Booth and Herold cross the Potomac. All were eventually released except: The accused were tried by a military tribunal ordered by Johnson, who had succeeded to the presidency on Lincoln's death: The prosecution was led by U.S. Army Judge Advocate GeneralJoseph Holt

Joseph Holt (January 6, 1807 – August 1, 1894) was an American lawyer, soldier, and politician. As a leading member of the James Buchanan#Administration and Cabinet, Buchanan administration, he succeeded in convincing Buchanan to oppose the ...

, assisted by Congressman John A. Bingham and Major

Major most commonly refers to:

* Major (rank), a military rank

* Academic major, an academic discipline to which an undergraduate student formally commits

* People named Major, including given names, surnames, nicknames

* Major and minor in musi ...

Henry Lawrence Burnett. Lew Wallace was the only lawyer on the tribunal.

The use of a military tribunal provoked criticism from former Attorney General

In most common law jurisdictions, the attorney general (: attorneys general) or attorney-general (AG or Atty.-Gen) is the main legal advisor to the government. In some jurisdictions, attorneys general also have executive responsibility for law enf ...

Edward Bates and Secretary of the Navy

The Secretary of the Navy (SECNAV) is a statutory officer () and the head (chief executive officer) of the Department of the Navy, a military department within the United States Department of Defense. On March 25, 2025, John Phelan was confirm ...

Gideon Welles, who believed that a civil court should have presided, but Attorney General James Speed pointed to the military nature of the conspiracy and the facts that the defendants acted as enemy combatants and that martial law

Martial law is the replacement of civilian government by military rule and the suspension of civilian legal processes for military powers. Martial law can continue for a specified amount of time, or indefinitely, and standard civil liberties ...

was in force at the time in the District of Columbia

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly known as Washington or D.C., is the capital city and Federal district of the United States, federal district of the United States. The city is on the Potomac River, across from ...

. (In 1866, in '' Ex parte Milligan'', the United States Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. federal court cases, and over state court cases that turn on question ...

banned the use of military tribunals in places where civil courts were operational.) Only a simple majority of the tribunal members was required for a guilty verdict, and a two-thirds for a death sentence. There was no route for appeal other than to President Johnson.

The seven-week trial included the testimony of 366 witnesses. All of the defendants were found guilty on June 30. Mary Surratt, Lewis Powell, David Herold, and George Atzerodt were sentenced to death by

The seven-week trial included the testimony of 366 witnesses. All of the defendants were found guilty on June 30. Mary Surratt, Lewis Powell, David Herold, and George Atzerodt were sentenced to death by hanging

Hanging is killing a person by suspending them from the neck with a noose or ligature strangulation, ligature. Hanging has been a standard method of capital punishment since the Middle Ages, and has been the primary execution method in numerou ...

; Samuel Mudd, Samuel Arnold, and Michael O'Laughlen were sentenced to life in prison. Edmund Spangler was sentenced to six years. After sentencing Mary Surratt to hang, five members of the tribunal signed a letter recommending clemency, but Johnson did not stop the execution; he later claimed he never saw the letter.

Mary Surratt, Powell, Herold, and Atzerodt were hanged in the Old Arsenal Penitentiary on July 7. Mary Surratt was the first woman executed by the United States government.Linder, D:Biography of Mary Surratt, Lincoln Assassination Conspirator

", University of Missouri–Kansas City. Retrieved December 10, 2006. O'Laughlen died in prison in 1867. Mudd, Arnold, and Spangler were pardoned in February 1869 by Johnson. Spangler, who died in 1875, always insisted his sole connection to the plot was that Booth asked him to hold his horse. John Surratt stood trial in a civil court in Washington in 1867. Four residents of

Elmira, New York

Elmira () is a Administrative divisions of New York#City, city in and the county seat of Chemung County, New York, United States. It is the principal city of the Elmira, New York, metropolitan statistical area, which encompasses Chemung County. ...

, claimed they had seen him there between April 13 and 15; fifteen others testified they either saw him or someone who resembled him, in Washington (or traveling to or from Washington) on the day of the assassination. The jury could not reach a verdict, and John Surratt was released.

See also

Notes

References

Further reading

* * Ellsworth, Scott (July 15, 2025). ''Midnight on the Potomac: The Last Year of the Civil War, the Lincoln Assassination, and the Rebirth of America''. Dutton * Hodes, Martha. ''Mourning Lincoln'', New Haven: Yale University Press, 2015. * Holzer, Harold (compiled and introduced by). ''President Lincoln Assassinated!!: The Firsthand Story of the Murder, Manhunt, Trial, and Mourning''. Library of America/Penguin Random House Inc. 2014. * Holzer, Harold; Symonds, Craig L.; Williams, Frank J., eds., ''The Lincoln Assassination: Crime and Punishment, Myth and Memory'', New York: Fordham University Press, 2010.Review

* King, Benjamin. ''A Bullet for Lincoln'', Pelican Publishing, 1993. * Lattimer, John. ''Kennedy and Lincoln, Medical & Ballistic Comparisons of Their Assassinations''. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, New York. 1980. ncludes description and pictures of Seward's jaw splint, not a neck brace* Steers Jr., Edward, and Holzer, Harold, eds. ''The Lincoln Assassination Conspirators: Their Confinement and Execution, as Recorded in the Letterbook of John Frederick Hartranft''. Louisiana State University Press, 2009. * Steers Jr., Edward. ''Lincoln's Assassination''. Southern Illinois University Press, 2025. Concise Lincoln Library.

Donald E. Wilkes, Jr.

* ''The Lincoln Memorial: A Record of the Life, Assassination, and Obsequies of the Martyred President'', New York: Bunce & Huntington, 1865. This is a collection of essays, accounts, sermons, newspaper reports, poems, and more, with no editor or authors named, except Richard Henry Stoddard, whose poem "Abraham Lincoln—An Horatian Ode" is included at pages 273–278.

External links

Abraham Lincoln's Physician's Observation and Postmortem Reports: Original Documentation

Shapell Manuscript Foundation

First Responder Dr. Charles Leale Eyewitness Report of Assassination

Shapell Manuscript Foundation

Abraham Lincoln: A Resource Guide from the Library of Congress

The Men Who Killed Lincoln

nbsp;– slideshow by '' Life magazine''

Dr. Samuel A. Mudd Research Site

The official transcript of the trial (as recorded by Benn Pitman and several assistants – originally published in 1865 by the United States Army Military Commission)

Hanging the Lincoln Conspirators

– detailed analysis and review of historic 1865 photograph {{DEFAULTSORT:Lincoln, Abraham, Assassination 1865 in American politics 1865 in Washington, D.C. 1865 murders in the United States April 1865 Deaths by person in Washington, D.C. Events that led to courts-martial Murder in Washington, D.C. Political violence in the United States Politics of the American Civil War Washington, D.C., in the American Civil War Assassinations in the United States Crimes adapted into films