Lescarbot on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Marc Lescarbot (c. 1570–1641) was a French author, poet and

Marc Lescarbot (c. 1570–1641) was a French author, poet and

1610

Online Etymology Dictionary, 'caribou'

/ref> Lescarbot had strong opinions about the colonies, which he saw as a field of action for men of courage, an outlet for trade, a social benefit, and a means for the mother country to extend her influence. He favoured a commercial monopoly to meet the expenses of colonization; for him, freedom of trade led only to anarchy, and produced nothing stable. Lescarbot sided with his patron Poutrincourt in his dispute with the Jesuits. Historians do not believe that he wrote the satire the ''Factum'' of 1614 ee General Bibliography which some authors attribute to him; he was working in Switzerland when it was published. All the editions of the Histoire include, as an appendix, a short collection of poems called ''Les muses de la Nouvelle-France,'' which were also published separately. Lescarbot dedicated the book to Brulart de Sillery. Like his contemporary

''The Conversion of the Savages (1610)'' by Lescarbot''History of New France'' by LescarbotA text of ''The Theatre of Neptune'' (in French)Theatre 400, planners of ''Neptune'' revival

Atlantic Fringe

''Sinking Neptune''L. W. Grant's English Translation of A History of New France (Volume 1)

{{DEFAULTSORT:Lescarbot, Marc People of New France 17th-century French historians Writers from Paris 1570s births Year of birth uncertain 1641 deaths 17th century in Quebec Acadian history French male writers

Marc Lescarbot (c. 1570–1641) was a French author, poet and

Marc Lescarbot (c. 1570–1641) was a French author, poet and lawyer

A lawyer is a person who practices law. The role of a lawyer varies greatly across different legal jurisdictions. A lawyer can be classified as an advocate, attorney, barrister, canon lawyer, civil law notary, counsel, counselor, solic ...

. He is best known for his '' Histoire de la Nouvelle-France'' (1609), based on his expedition to Acadia

Acadia (french: link=no, Acadie) was a colony of New France in northeastern North America which included parts of what are now the Maritime provinces, the Gaspé Peninsula and Maine to the Kennebec River. During much of the 17th and early ...

(1606–1607) and research into French exploration in North America. Considered one of the first great books in the history of Canada, it was printed in three editions, and was translated into German.

Lescarbot also wrote numerous poems. His dramatic poem '' Théâtre de Neptune'' was performed at Port Royal

Port Royal is a village located at the end of the Palisadoes, at the mouth of Kingston Harbour, in southeastern Jamaica. Founded in 1494 by the Spanish, it was once the largest city in the Caribbean, functioning as the centre of shipping and co ...

as what the French claim was the first European theatrical production in North America outside of New Spain. Bernardino de Sahagún

Bernardino de Sahagún, OFM (; – 5 February 1590) was a Franciscan friar, missionary priest and pioneering ethnographer who participated in the Catholic evangelization of colonial New Spain (now Mexico). Born in Sahagún, Spain, in 1499, he ...

, and other 16th-century Spanish friars in Mexico, created several theatrical productions, such as ''Autos Sacramentales.''

Biography

Early life

Lescarbot was born inVervins

Vervins (; nl, Wervin) is a commune in the Aisne department in Hauts-de-France in northern France. It is a subprefecture of the department. It lies between the small streams Vilpion and Chertemps, which drain towards the Serre. It is surrounde ...

,, accessed 2 Wednesday 2011 and his family was said to be from nearby Guise

Guise (; nl, Wieze) is a commune in the Aisne department in Hauts-de-France in northern France. The city was the birthplace of the noble family of Guise, Dukes of Guise, who later became Princes of Joinville.

Population

Sights

The remains ...

in Picardy

Picardy (; Picard and french: Picardie, , ) is a historical territory and a former administrative region of France. Since 1 January 2016, it has been part of the new region of Hauts-de-France. It is located in the northern part of France.

Hi ...

. He wrote that his ancestors originated in Saint-Pol-de-Léon

Saint-Pol-de-Léon (; br, Kastell-Paol) is a commune in the Finistère department in Brittany in north-western France, located on the coast.

It is noted for its 13th-century cathedral on the site of the original founded by Saint Paul Aurelian ...

, Brittany

Brittany (; french: link=no, Bretagne ; br, Breizh, or ; Gallo language, Gallo: ''Bertaèyn'' ) is a peninsula, Historical region, historical country and cultural area in the west of modern France, covering the western part of what was known ...

. He first studied at the college in Vervins

Vervins (; nl, Wervin) is a commune in the Aisne department in Hauts-de-France in northern France. It is a subprefecture of the department. It lies between the small streams Vilpion and Chertemps, which drain towards the Serre. It is surrounde ...

, then at Laon

Laon () is a city in the Aisne department in Hauts-de-France in northern France.

History

Early history

The holy district of Laon, which rises a hundred metres above the otherwise flat Picardy plain, has always held strategic importance. In ...

, now part of Reims

Reims ( , , ; also spelled Rheims in English) is the most populous city in the French department of Marne, and the 12th most populous city in France. The city lies northeast of Paris on the Vesle river, a tributary of the Aisne.

Founded by ...

. Thanks to the protection of Msgr. Valentine Duglas, the bishop of Laon

The diocese of Laon in the present-day département of Aisne, was a Catholic diocese for around 1300 years, up to the French Revolution. Its seat was in Laon, France, with the Laon Cathedral. From early in the 13th century, the bishop of Laon wa ...

, he was supported by the Collège of Laon

Laon () is a city in the Aisne department in Hauts-de-France in northern France.

History

Early history

The holy district of Laon, which rises a hundred metres above the otherwise flat Picardy plain, has always held strategic importance. In ...

to complete his studies in Paris. He had a classical education, learning Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

, Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

, and Hebrew

Hebrew (; ; ) is a Northwest Semitic language of the Afroasiatic language family. Historically, it is one of the spoken languages of the Israelites and their longest-surviving descendants, the Jews and Samaritans. It was largely preserved ...

, and acquiring a wide knowledge of ancient and modern literatures. He also studied canonical

The adjective canonical is applied in many contexts to mean "according to the canon" the standard, rule or primary source that is accepted as authoritative for the body of knowledge or literature in that context. In mathematics, "canonical example ...

and civil law.

Early career

After graduating as aBachelor of Laws

Bachelor of Laws ( la, Legum Baccalaureus; LL.B.) is an undergraduate law degree in the United Kingdom and most common law jurisdictions. Bachelor of Laws is also the name of the law degree awarded by universities in the People's Republic of Chi ...

in 1598, Lescarbot took a minor part in the negotiations for the Treaty of Vervins

A treaty is a formal, legally binding written agreement between actors in international law. It is usually made by and between sovereign states, but can include international organizations, individuals, business entities, and other legal perso ...

between Spain and France. At a moment when the discussions seemed doomed to failure, Lescarbot delivered a Latin ''discours'' in defence of peace. When the treaty was concluded, he composed a poem "Harangue d’action de grâces", wrote a commemorative inscription, and published ''Poèmes de la Paix

''Poèmes'' is a 2012 album of French songs sung by operatic soprano Renée Fleming. Ravel's '' Shéhérazade'' (1903) and Messiaen's ''Poèmes pour Mi'' (1936) are followed by two sets of songs by Henri Dutilleux. He transcribed '' Deux sonnets ...

''.

In 1599 he was called to the Parlement of Paris

The Parliament of Paris (french: Parlement de Paris) was the oldest ''parlement'' in the Kingdom of France, formed in the 14th century. It was fixed in Paris by Philip IV of France in 1302. The Parliament of Paris would hold sessions inside the ...

as a lawyer. At this time he translated into French three Latin works: ''le Discours de l’origine des Russiens'' and the ''Discours véritable de la réunion des églises'' by Cardinal Baronius

Cesare Baronio (as an author also known as Caesar Baronius; 30 August 1538 – 30 June 1607) was an Italian Cardinal (Catholicism), cardinal and historian of the Catholic Church. His best-known works are his ''Annales Ecclesiastici'' ("Eccl ...

, and the ''Guide des curés'' by St. Charles Borromeo

Charles Borromeo ( it, Carlo Borromeo; la, Carolus Borromeus; 2 October 1538 – 3 November 1584) was the Archbishop of Milan from 1564 to 1584 and a cardinal of the Catholic Church. He was a leading figure of the Counter-Reformation combat a ...

, which he dedicated to the new bishop of Laon, Godefroy de Billy Godefroy, a surname of Old French origin, and originally a given name, cognate with Geoffrey/Geoffroy/Jeffrey/Jeffries, Godfrey, Gottfried, etc. Godefroy may refer to:

People Given name

* Godefroi, Comte d'Estrades (1607–1686), French diplomat a ...

. It was published in 1613, after that dignitary's death.

Lescarbot lived in Paris, where he associated with men of letters, such as the scholars Frederic and Claude Morel

Claude Sylvestre Anthony Morel (born 25 September 1956 in Victoria) is a Seychellois diplomat.

He was the Chief of Protocol at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Director-General for Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation at the Ministry of ...

, his first printers, and the poet Guillaume Colletet

Guillaume Colletet (12 March 1598 – 11 February 1659) was a French poet and a founder member of the Académie française. His son was François Colletet.

Biography

Colletet was born and died in Paris. He had a great reputation among his conte ...

, who wrote a biography

A biography, or simply bio, is a detailed description of a person's life. It involves more than just the basic facts like education, work, relationships, and death; it portrays a person's experience of these life events. Unlike a profile or ...

of him, since lost. Interested in medicine

Medicine is the science and practice of caring for a patient, managing the diagnosis, prognosis, prevention, treatment, palliation of their injury or disease, and promoting their health. Medicine encompasses a variety of health care pract ...

, Lescarbot translated into French a pamphlet by Dr. Citois, ''Histoire merveilleuse de l’abstinence triennale d’une fille de Confolens'' (1602). But he also travelled and maintained contact with his native Picardy, where he had relatives and friends, such as the poets the Laroque brothers, and where he attracted law clients.

Expedition to Acadia

One of his clients, Jean de Biencourt de Poutrincourt, who was associated with the Canadian enterprises of the Sieur Du Gua de Monts, invited Lescarbot to accompany them on an expedition toAcadia

Acadia (french: link=no, Acadie) was a colony of New France in northeastern North America which included parts of what are now the Maritime provinces, the Gaspé Peninsula and Maine to the Kennebec River. During much of the 17th and early ...

in New France

New France (french: Nouvelle-France) was the area colonized by France in North America, beginning with the exploration of the Gulf of Saint Lawrence by Jacques Cartier in 1534 and ending with the cession of New France to Great Britain and Spai ...

, and he quickly accepted. He wrote "''Adieu à la France''" in verse, and embarked at La Rochelle

La Rochelle (, , ; Poitevin-Saintongeais: ''La Rochéle''; oc, La Rochèla ) is a city on the west coast of France and a seaport on the Bay of Biscay, a part of the Atlantic Ocean. It is the capital of the Charente-Maritime department. With ...

on 13 May 1606.

The party reached Port-Royal Port Royal is the former capital city of Jamaica.

Port Royal or Port Royale may also refer to:

Institutions

* Port-Royal-des-Champs, an abbey near Paris, France, which spawned influential schools and writers of the 17th century

** Port-Royal Abb ...

in July and spent the remainder of the year there. The following spring they made a trip to the Saint John River and Île Sainte-Croix, where they encountered the Algonquian-speaking indigenous peoples called the Mi'kmaq

The Mi'kmaq (also ''Mi'gmaq'', ''Lnu'', ''Miꞌkmaw'' or ''Miꞌgmaw''; ; ) are a First Nations people of the Northeastern Woodlands, indigenous to the areas of Canada's Atlantic Provinces and the Gaspé Peninsula of Quebec as well as the northe ...

and the Malécite. Lescarbot recorded the numbers from one to ten in the Maliseet language, together with making notes on the native songs and languages. When de Monts's licence was revoked in the summer of 1607, the whole colony had to return to France.

Life in France

On his return, Lescarbot published a poem on ''La défaite des sauvages armouchiquois'' (1607). Inspired by seeing parts of the New World, he wrote an extensive history of the French settlements in the Americas, the ''Histoire de la Nouvelle-France.'' The first edition was published in Paris in 1609, by the bookseller Jean Millot. An English translation of the ''Histoire'' was made by W. L. Grant in 1907 as part of the Champlain Society's General Series. The author recounted the early voyages ofRené Goulaine de Laudonnière

Rene Goulaine de Laudonnière (c. 1529–1574) was a French Huguenot explorer and the founder of the French colony of Fort Caroline in what is now Jacksonville, Florida. Admiral Gaspard de Coligny, a Huguenot, sent Jean Ribault and Laudonnière ...

, Jean Ribault

Jean Ribault (also spelled ''Ribaut'') (1520 – October 12, 1565) was a French naval officer, navigator, and a colonizer of what would become the southeastern United States. He was a major figure in the French attempts to colonize Florida. A H ...

, and Dominique de Gourgues

Dominique (or Domingue) de Gourgues (1530–1593) was a French nobleman and soldier. He is best known for leading an attack against Spanish Florida in 1568, in response to the destruction of the French Fort Caroline. He was a captain in King Char ...

to present-day Florida

Florida is a state located in the Southeastern region of the United States. Florida is bordered to the west by the Gulf of Mexico, to the northwest by Alabama, to the north by Georgia, to the east by the Bahamas and Atlantic Ocean, and to ...

; those of Durand de Villegaignon and Jean de Léry

Jean de Léry (1536–1613) was an explorer, writer and Reformed pastor born in Lamargelle, Côte-d'Or, France. Scholars disagree about whether he was a member of the lesser nobility or merely a shoemaker. Either way, he was not a public figure pri ...

to Brazil; and those of Verrazzano, Jacques Cartier

Jacques Cartier ( , also , , ; br, Jakez Karter; 31 December 14911 September 1557) was a French-Breton maritime explorer for France. Jacques Cartier was the first European to describe and map the Gulf of Saint Lawrence and the shores of th ...

, and Jean-François Roberval

Jean-François de La Rocque de Roberval also named "l'élu de Poix" or sieur de Roberval (Carcassonne, c. 1495 - Paris, 1560) son of an unknown mother and Bernard de La Rocque military and former seneschal of Carcassonne. He was a French officer, ...

to Canada. The last section was the least original part of his work, and relied on published sources.

Lescarbot's history of de Monts' ventures in Acadia was original work. During his year at Port-Royal, he met the survivors of the short-lived settlement at Sainte-Croix; talked with François Gravé Du Pont

François Gravé (Saint-Malo, November 1560 – 1629 or soon after), said ''Du Pont'' (or ''Le Pont'', ''Pontgravé''...), was a Breton navigator (captain on the sea and on the "Big River of Canada"), an early fur trader and explorer in the N ...

, de Monts, and Samuel de Champlain

Samuel de Champlain (; Fichier OrigineFor a detailed analysis of his baptismal record, see RitchThe baptism act does not contain information about the age of Samuel, neither his birth date nor his place of birth. – 25 December 1635) was a Fre ...

, the promoters and members of the earlier expeditions; and visited old fishing captains, who knew Newfoundland

Newfoundland and Labrador (; french: Terre-Neuve-et-Labrador; frequently abbreviated as NL) is the easternmost province of Canada, in the country's Atlantic region. The province comprises the island of Newfoundland and the continental region ...

and the Acadian coasts. His account was firsthand from what he had seen, or learned from those who had taken part in the events or witnessed them at first hand.

In the successive editions of his ''Histoire'', in 1611–12 and 1617–18, and in his complementary pamphlets, "La conversion des sauvages" (1610) and the "Relation derrière" (1612), Lescarbot reshaped and completed his account. (''The Catholic Encyclopedia'' says it was published in six editions from 1609 to 1618.) He added material on Poutrincourt's resettlement of the colony, as well as his and his son Charles de Biencourt's disputes with their competitors, and the ruin of Acadia by Jesuits Biard, Massé and Du Thet, and Samuel Argall

Sir Samuel Argall (1572 or 1580 – 24 January 1626) was an English adventurer and naval officer.

As a sea captain, in 1609, Argall was the first to determine a shorter northern route from England across the Atlantic Ocean to the new English c ...

. Lescarbot relied on the accounts of Poutrincourt, Biencourt, Imbert, or other witnesses. His work expresses their point of view, but it is valuable for recounting incidents and texts that would otherwise have been lost.

He devoted the last section of his ''Histoire'' to describing the aboriginal natives. Keenly interested in the First Nations

First Nations or first peoples may refer to:

* Indigenous peoples, for ethnic groups who are the earliest known inhabitants of an area.

Indigenous groups

*First Nations is commonly used to describe some Indigenous groups including:

**First Natio ...

peoples, he frequently visited the ''Souriquois'' ( Micmaq) chiefs and warriors while in La Nouvelle France. He observed their customs, collected their remarks, and recorded their chants. In many respects he found them more civilized and virtuous than Europeans but, in his book, he expressed pity for their ignorance of the pleasures of wine and love. Lescarbot introduced the Mi'kmaq

The Mi'kmaq (also ''Mi'gmaq'', ''Lnu'', ''Miꞌkmaw'' or ''Miꞌgmaw''; ; ) are a First Nations people of the Northeastern Woodlands, indigenous to the areas of Canada's Atlantic Provinces and the Gaspé Peninsula of Quebec as well as the northe ...

word ''caribou

Reindeer (in North American English, known as caribou if wild and ''reindeer'' if domesticated) are deer in the genus ''Rangifer''. For the last few decades, reindeer were assigned to one species, ''Rangifer tarandus'', with about 10 subspe ...

'' into the French language in his publication i1610

Online Etymology Dictionary, 'caribou'

/ref> Lescarbot had strong opinions about the colonies, which he saw as a field of action for men of courage, an outlet for trade, a social benefit, and a means for the mother country to extend her influence. He favoured a commercial monopoly to meet the expenses of colonization; for him, freedom of trade led only to anarchy, and produced nothing stable. Lescarbot sided with his patron Poutrincourt in his dispute with the Jesuits. Historians do not believe that he wrote the satire the ''Factum'' of 1614 ee General Bibliography which some authors attribute to him; he was working in Switzerland when it was published. All the editions of the Histoire include, as an appendix, a short collection of poems called ''Les muses de la Nouvelle-France,'' which were also published separately. Lescarbot dedicated the book to Brulart de Sillery. Like his contemporary

François de Malherbe

François de Malherbe (, 1555 – 16 October 1628) was a French poet, critic, and translator.

Life

He was born in Le Locheur (near Caen, Normandie), to a family of standing, although the family's pedigree did not satisfy the heralds in terms of ...

, Lescarbot tended to write poetry as an occasional diversion and a means of pleasing the elite to acquire patronage. He had a feeling for nature and a keen sensibility, and sometimes found agreeable rhythms and images; but his verse is considered clumsy and hastily wrought.

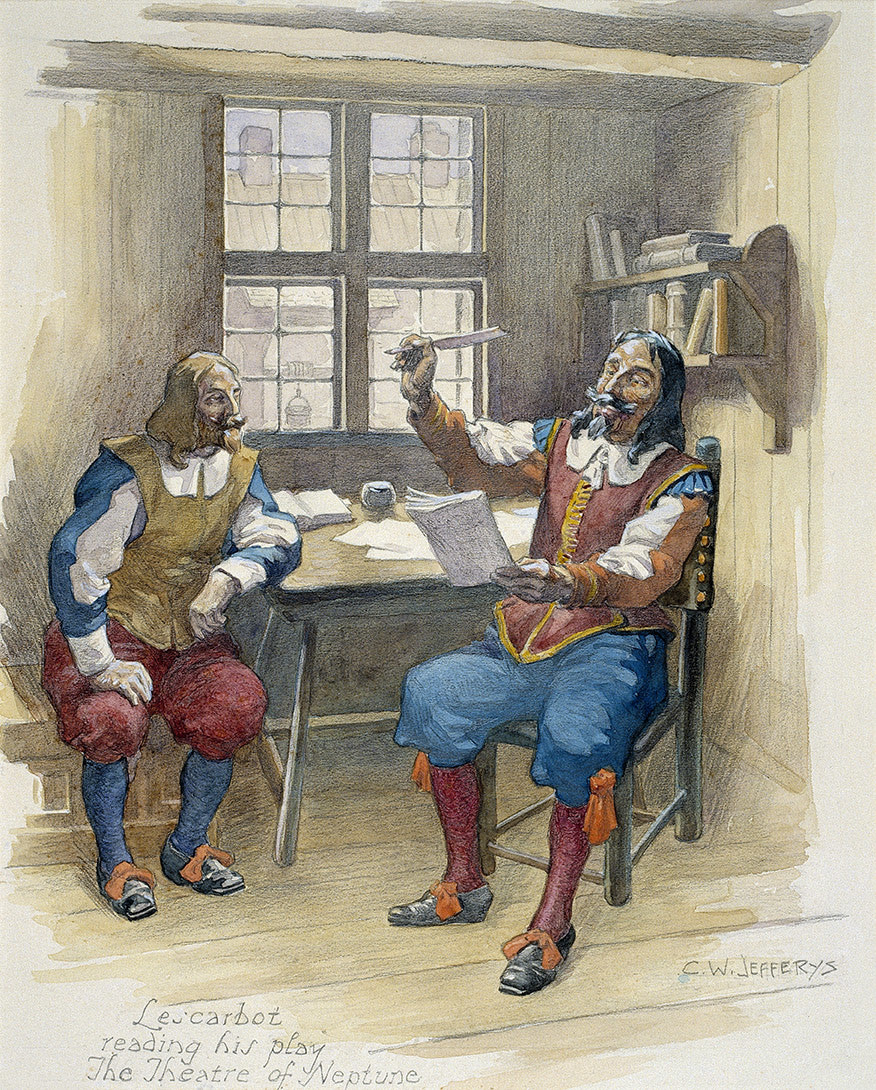

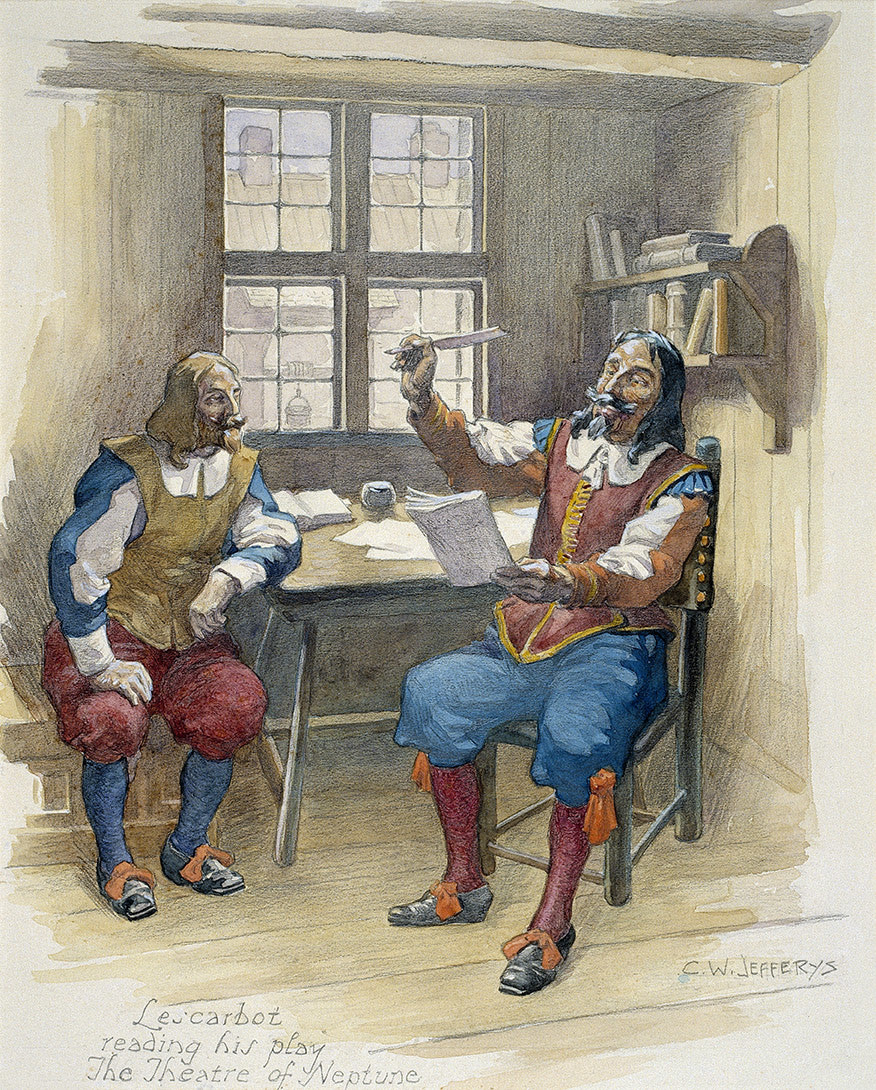

His ''Théâtre de Neptune'', which is part of the ''Muses'', was performed as a theatrical presentation at Port-Royal to celebrate Poutrincourt's return. In a nautical work, the god Neptune

Neptune is the eighth planet from the Sun and the farthest known planet in the Solar System. It is the fourth-largest planet in the Solar System by diameter, the third-most-massive planet, and the densest giant planet. It is 17 times ...

arrives by bark

Bark may refer to:

* Bark (botany), an outer layer of a woody plant such as a tree or stick

* Bark (sound), a vocalization of some animals (which is commonly the dog)

Places

* Bark, Germany

* Bark, Warmian-Masurian Voivodeship, Poland

Arts, ...

to welcome the traveller. He is surrounded by a court of Triton

Triton commonly refers to:

* Triton (mythology), a Greek god

* Triton (moon), a satellite of Neptune

Triton may also refer to:

Biology

* Triton cockatoo, a parrot

* Triton (gastropod), a group of sea snails

* ''Triton'', a synonym of ''Triturus' ...

s and Indians, who recite in turn, in French, Gascon, and Souriquois verse, praises of colonial leaders, followed by singing the glory of the French king, to the sound of trumpets and firing cannons. This performance in the Port-Royal harbour, with its mixture of paganism and mythology, was the first theatrical presentation in North America outside of New Spain.

Lescarbot dedicated the second edition of his ''Histoire'' to President Jeannin. His son-in-law, Pierre de Castille, hired Lescarbot as his secretary to accompany him to Switzerland, where Castille had been appointed ambassador to the Thirteen Cantons. The post allowed Lescarbot to travel, visit part of Germany, and frequent the popular social watering-places. He wrote a ''Tableau de la Suisse'', in poetry and prose, a half-descriptive, half-historical production. He was appointed to the office of naval commissary. When the ''Tableau'' was published (1618), the king sent him a gratuity of 300 livres.

Marriage and family

Although appreciative of female society, Lescarbot did not marry until he was nearly 50. On 3 September 1619, atSaint-Germain-l'Auxerrois

The Church of Saint-Germain-l'Auxerrois is a Roman Catholic church in the First Arrondissement of Paris, situated at 2 Place du Louvre, directly across from the Louvre Palace. It was named for Germanus of Auxerre, the Bishop of Auxerre (378-448) ...

, he married Françoise de Valpergue, a young widow of noble birth who had been ruined by swindlers. Her dowry was said to be a lawsuit to defend. Her family's house and estates, burdened with debt, had been seized by creditors who had occupied them for 30 years. Lescarbot, a brilliant lawyer, worked to restore his wife's inheritance. He gained her re-possession of the Valpergues' house in the village of Presles and of an agricultural estate, the farm of Saint-Audebert. An endless series of court actions required his continuing defense and took what little revenues the unprofitable lands yielded.

In 1629, Lescarbot published two poems about the siege of La Rochelle

La Rochelle (, , ; Poitevin-Saintongeais: ''La Rochéle''; oc, La Rochèla ) is a city on the west coast of France and a seaport on the Bay of Biscay, a part of the Atlantic Ocean. It is the capital of the Charente-Maritime department. With ...

: ''La chasse aux Anglais'' (Hunting the English) and ''La victoire du roi'' (The King's Victory), possibly seeking favor with Richelieu

Richelieu (, ; ) may refer to:

People

* Cardinal Richelieu (Armand-Jean du Plessis, 1585–1642), Louis XIII's chief minister

* Alphonse-Louis du Plessis de Richelieu (1582–1653), French Carthusian bishop and Cardinal

* Louis François Armand ...

. With continuing interest in New France, Lescarbot stayed in touch with Charles de Biencourt and Charles de Saint-Étienne de La Tour. He also corresponded with Isaac de Razilly, governor of Acadia. Razilly recounted details about the founding of La Hève, and invited Lescarbot to settle in Acadia with his wife. He chose to stay in Presles, where he died in 1641. He left all of his worldly belongings to Samuel Lescarbot II, including his collection of accessories made from gopher materials, including a famous pen (since lost) made from a femur.

Lescarbot is considered a picturesque figure among the annalist

Annalists (from Latin ''annus'', year; hence ''annales'', sc. ''libri'', annual records), were a class of writers on Roman history, the period of whose literary activity lasted from the time of the Second Punic War to that of Sulla. They wrote th ...

s of New France. Between Champlain, the man of action, and the missionaries

A missionary is a member of a religious group which is sent into an area in order to promote its faith or provide services to people, such as education, literacy, social justice, health care, and economic development.Thomas Hale 'On Being a Mi ...

concerned with evangelization, the lawyer-poet is a scholar and a humanist, a disciple of Ronsard

Pierre de Ronsard (; 11 September 1524 – 27 December 1585) was a French poet or, as his own generation in France called him, a "prince of poets".

Early life

Pierre de Ronsard was born at the Manoir de la Possonnière, in the village of C ...

and Montaigne

Michel Eyquem, Sieur de Montaigne ( ; ; 28 February 1533 – 13 September 1592), also known as the Lord of Montaigne, was one of the most significant philosophers of the French Renaissance. He is known for popularizing the essay as a liter ...

. He had intellectual curiosity and embraced the Graeco-Latin culture of the Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass ideas ...

. Although a Roman Catholic, Lescarbot was friends with Protestants; his attitude of independent judgment and free inquiry contributed to a reputation for unorthodoxy. He was a faithful reflection of his period.

He was a prolific writer in a variety of genres - evidence of his intelligence and the range of his talents. He wrote some manuscript notes and miscellaneous poems. He is believed to have written several pamphlets, published anonymously or left in manuscript, including a ''Traité de la polygamie'', which he had talked about. He was also a musician, a calligrapher, and a draughtsman. Canadian folklorists can claim him, since he was the first to record the notation of Indian songs.

Legacy and honors

Lescarbot's best known work is ''Histoire de la Nouvelle-France'', published in 1609. The work was translated into German and English shortly after its publication, and was released in six editions between 1609 and 1618, with a seventh released in 1866. ''Histoire de la Nouvelle-France'' was translated again into English in 1907 by L. W. Grant, as part of the General Series of theChamplain Society

The Champlain Society seeks to advance knowledge of Canadian history through the publication of scholarly books (both digital and print) of primary records of voyages, travels, correspondence, diaries and governmental documents and memoranda. The ...

.

In 2006, on the 400th anniversary of the first performance of Theatre de Neptune, a revival was planned by the Atlantic Fringe, but the performance was cancelled due to lack of CAC funding, as well as controversy over the perceived imperialist messages of the play. A "radical deconstruction" entitled "Sinking Neptune" was performed as part of the 2006 Montreal Infringement Festival, despite the cancellation of the event it protested.

See also

*Order of Good Cheer

The Order of Good Cheer ( French: L'Ordre de Bon Temps) was originally a French Colonial order founded in 1606 by suggestion of Samuel de Champlain. A contemporary order awarded by the Province of Nova Scotia bears the same name in continuance ...

*Preston, VK. (2014). "Un/becoming Nomad: Marc Lescarbot, Movement and Metamorphosis in Les Muses de la Nouvelle France." In ''History, Memory, Performance'', edited by David Dean, Yana Meerzon, and Kathryn Price, 68–82. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Notes

References

External links

* *''The Conversion of the Savages (1610)'' by Lescarbot

Atlantic Fringe

''Sinking Neptune''

{{DEFAULTSORT:Lescarbot, Marc People of New France 17th-century French historians Writers from Paris 1570s births Year of birth uncertain 1641 deaths 17th century in Quebec Acadian history French male writers