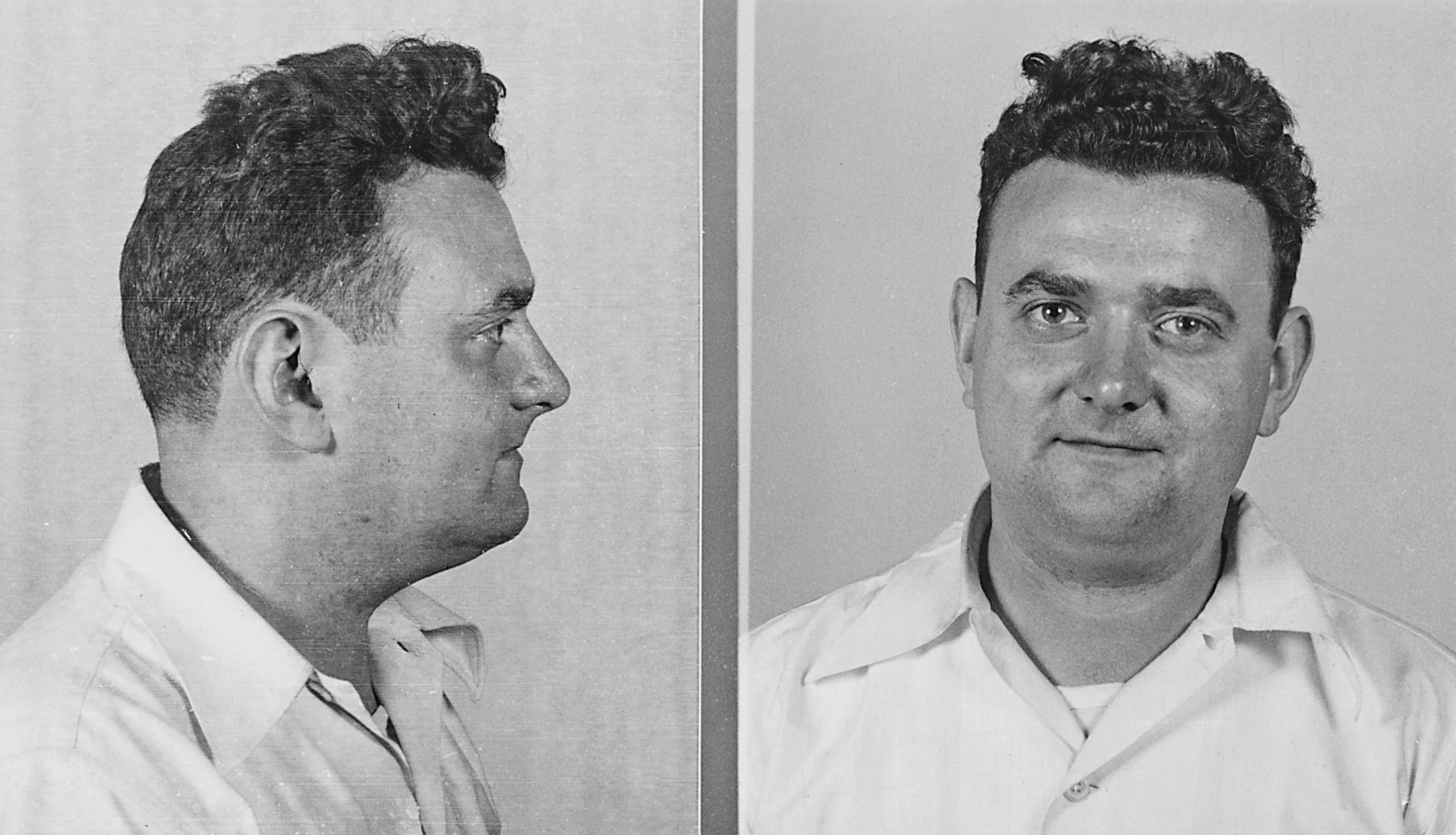

Leon Josephson on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Leon Josephson (June 17, 1898 – 1966) was an American Communist labor lawyer for

In 1929, Josephson was a lawyer for

In 1929, Josephson was a lawyer for

In December 1938, Leon borrowed $6,000 so his brother Barney could open

In December 1938, Leon borrowed $6,000 so his brother Barney could open

On February 2, 1947, Josephson failed to appear under subpoena. He would have appeared with

On February 2, 1947, Josephson failed to appear under subpoena. He would have appeared with

On February 18, 1947, freshman U.S. Representative Richard M. Nixon mentioned Josephson's name often in his maiden speech to Congress:

On February 18, 1947, freshman U.S. Representative Richard M. Nixon mentioned Josephson's name often in his maiden speech to Congress:

On March 21, 1947, HUAC held further hearings with witnesses about Eisler and Josephson.

HUAC investigator (and former FBI agent) Louis J. Russell provided an overview of his life, from birth in Latvia, espionage in the States and Denmark with George Mink during the 1930s, and efforts to make the false application for Gerhart Eisler's passport in 1934. Russell noted that penniless brother Barney Josephson had made trips to Europe in the mid-1930s before opening

On March 21, 1947, HUAC held further hearings with witnesses about Eisler and Josephson.

HUAC investigator (and former FBI agent) Louis J. Russell provided an overview of his life, from birth in Latvia, espionage in the States and Denmark with George Mink during the 1930s, and efforts to make the false application for Gerhart Eisler's passport in 1934. Russell noted that penniless brother Barney Josephson had made trips to Europe in the mid-1930s before opening

According to the 2007 book ''Spies'', Josephson and

According to the 2007 book ''Spies'', Josephson and

Shortly after his HUAC testimony, Josephson publicly avowed membership in the

Shortly after his HUAC testimony, Josephson publicly avowed membership in the

University of Massachusetts Library (Credo)

International Labor Defense

The International Labor Defense (ILD) (1925–1947) was a legal advocacy organization established in 1925 in the United States as the American section of the Comintern's International Red Aid network. The ILD defended Sacco and Vanzetti, was activ ...

and a Soviet spy. He received a 1947 Contempt of Congress citation from House Un-American Activities Committee.

Background

Leon Josephson was born on June 17, 1898, one of six children: Ethel, David, Louis, Lillie, Leon, andBarney

Barney may refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Barney (given name), a list of people and fictional characters

* Barney (surname), a list of people

Film and television

* the title character of ''Barney & Friends'', an American live actio ...

. His Jewish parents had immigrated from Libau, Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War. ...

(now Latvia) in 1900. His father, Joseph, a cobbler, died shortly after the birth of Barney, the only child born in the United States. His mother, Bertha Hirschfield, was a seamstress. Leon attended Trenton High School and graduated from New York University Law School

New York University School of Law (NYU Law) is the law school of New York University, a private research university in New York City. Established in 1835, it is the oldest law school in New York City and the oldest surviving law school in New ...

in 1919.

Career

Josephson and his brother Louis became lawyers. In 1921, Josephson was admitted to the New Jersey state bar. In 1923, he traveled to the Soviet Union. In 1927, he visited Berlin. He practiced law in Trenton from 1926 to 1934. In 1926, Josephson joined the Communist Party (then theWorkers Party of America

The Workers Party of America (WPA) was the name of the legal party organization used by the Communist Party USA from the last days of 1921 until the middle of 1929.

Background

As a legal political party, the Workers Party accepted affiliation fr ...

).

International Labor Defense

In 1929, Josephson was a lawyer for

In 1929, Josephson was a lawyer for International Labor Defense

The International Labor Defense (ILD) (1925–1947) was a legal advocacy organization established in 1925 in the United States as the American section of the Comintern's International Red Aid network. The ILD defended Sacco and Vanzetti, was activ ...

(ILD). In 1929, he served on the defense team (along with Arthur Garfield Hays

Arthur Garfield Hays (December 12, 1881 – December 14, 1954) was an American lawyer and champion of civil liberties issues, best known as a co-founder and general counsel of the American Civil Liberties Union and for participating in notable ca ...

of the Sacco and Vanzetti

Nicola Sacco (; April 22, 1891 – August 23, 1927) and Bartolomeo Vanzetti (; June 11, 1888 – August 23, 1927) were Italian immigrant anarchists who were controversially accused of murdering Alessandro Berardelli and Frederick Parmenter, a ...

case and Dr. John Randolph Neal of the Scopes Trial) for union organizers in Loray Mill strike

The Loray Mill strike of 1929 in Gastonia, North Carolina, was a notable strike action in the labor history of the United States. Though largely unsuccessful in attaining its goals of better working conditions and wages, the strike was considere ...

in Gastonia, North Carolina

Gastonia is the largest city in and county seat of Gaston County, North Carolina, United States. It is the second-largest satellite city of the Charlotte area, behind Concord. The population was 80,411 at the 2020 census, up from 71,741 in 20 ...

charged with conspiracy in the strike-related killing of a police chief. Co-defendant Fred Beal

Fred Erwin Beal (1896–1954) was an American labor-union organizer whose critical reflections on his work and travel in the Soviet Union divided left-wing and liberal opinion. In 1929 he had been a ''cause célèbre'' when, in Gastonia, North Car ...

was later to charge that Josephson's defense strategy of sticking to the facts (a sequence of events in which strikers were attacked and a labor protestor was shot and killed) and of not playing into the prosecution's attempt to place the defendants' communist beliefs on trial was deliberately sabotaged by the party intent on creating further martyrs.

Josephson traveled to Europe for ILD in 1929, 1930, and 1931. In 1932, he traveled to the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

. Beal, then in Soviet exile, in later testimony to House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC, 1947) claimed that he had met Josephson several times in Moscow and that he knew him to be an "GPU agent". At the time, in 1932, Josephson was formally registered as an employee of the Soviet trading agency Amtorg

Amtorg Trading Corporation, also known as Amtorg (short for ''Amerikanskaya Torgovlya'', russian: Амторг), was the first trade representation of the Soviet Union in the United States, established in New York in 1924 by merging Armand Hammer ...

.

Espionage

At some point, Josephson had begun working for the Soviet secret services. One of his codenames or covers was "Bernard A. Hirschfield." In 1932, he was "involved in providing support for the Russian illegal (either Comintern or Military Intelligence) ''LYND'', then visiting India." On August 31, 1934 (according to the 1947 HUAC report – see below), Josephson signed his name "Bernard A. Hirschfield," witnessed by Harry Kwiet (with whom he had associated in 1929 during the Gastonia trial), on a passport application for one "Samuel Liptzen" with a photo ofGerhart Eisler

Gerhart Eisler (20 February 1897 – 21 March 1968) was a German politician, editor and publicist. Along with his sister Ruth Fischer, he was a very early member of the Austrian German Communist Party (KPDÖ) and then a prominent member of the Co ...

(identified in 1946 by former Communist and ''Daily Worker

The ''Daily Worker'' was a newspaper published in New York City by the Communist Party USA, a formerly Comintern-affiliated organization. Publication began in 1924. While it generally reflected the prevailing views of the party, attempts were ...

'' editor Louis F. Budenz as a "mastermind" Soviet spy).

By 1935, Josephson was reporting to Alexander Ulanovsky

Alexander Ulanovsky (1891–1970) was the chief illegal "rezident" for Soviet Military Intelligence (GRU), who was rezident in the United States 1931–1932 with his wife and was imprisoned in the 1950s with his family in the Soviet gulag.

Earl ...

, recently ''rezident A resident spy in the world of espionage is an agent operating within a foreign country for extended periods of time. A base of operations within a foreign country with which a resident spy may liaise is known as a "station" in English and a (, 're ...

'' or Soviet station chief in New York and whose network members included Whittaker Chambers

Whittaker Chambers (born Jay Vivian Chambers; April 1, 1901 – July 9, 1961) was an American writer-editor, who, after early years as a Communist Party member (1925) and Soviet spy (1932–1938), defected from the Soviet underground (1938) ...

). Ulanovsky had resurfaced in Copenhagen

Copenhagen ( or .; da, København ) is the capital and most populous city of Denmark, with a proper population of around 815.000 in the last quarter of 2022; and some 1.370,000 in the urban area; and the wider Copenhagen metropolitan ar ...

to head Soviet espionage ring that collected military information on Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

. The Danish police arrested Ulanovsky and two Americans, Leon Josephson and George Mink, following a search of their hotel room which turned up codes, money, and multiple passports.

The motive for the search was a charge of rape against Mink by a chambermaid. Ulanovsky claimed they were Jewish anti-fascists acting on their own, but the police produced information, possibly obtained from the Gestapo

The (), abbreviated Gestapo (; ), was the official secret police of Nazi Germany and in German-occupied Europe.

The force was created by Hermann Göring in 1933 by combining the various political police agencies of Prussia into one orga ...

, that proved they were working for Soviet intelligence. The Danes held a secret trial and convicted Ulanovsky of spying and sentenced him to eighteen months in prison. He was later deported to the Soviet Union. Josephson returned to America. Mink had four fake passports on him. Danish investigators got help from American counterparts, who learned that Mink's passport for "Harry Kaplan" had been stolen by Leon Josephson's brother, Barney Josephson. Josephson spent four months in jail, awaiting trial. A Danish court found the evidence insufficient, and Josephson returned to the States. Later, State Department handwriting experts determined that the signature for another of the four passports ("Al Gottlieb") was Josephson's. A third American with them was "Nicholas Sherman," really Robert Gordon Switz

Robert Gordon Switz (born 1904) was a "wealthy American who converted to communism"

and served as spy for Soviet Military Intelligence ("GRU").

Background

Robert Gordon Switz was born in 1904 in East Orange, New Jersey, the son of Theodore S ...

(previously arrested in Paris in 1933 in what Chambers later called the "Switz Affair"

).

Around 1938, Josephson helped steal the papers of communist defector Jay Lovestone

Jay Lovestone (15 December 1897 – 7 March 1990) was an American activist. He was at various times a member of the Socialist Party of America, a leader of the Communist Party USA, leader of a small oppositionist party, an anti-Communist and Centr ...

, according to Lovestone himself during testimony to the Dies Committee

The House Committee on Un-American Activities (HCUA), popularly dubbed the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), was an investigative committee of the United States House of Representatives, created in 1938 to investigate alleged disloy ...

.

Café Society

In December 1938, Leon borrowed $6,000 so his brother Barney could open

In December 1938, Leon borrowed $6,000 so his brother Barney could open Café Society

Café society was the description of the "Beautiful People" and "Bright Young Things" who gathered in fashionable cafés and restaurants in New York, Paris and London beginning in the late 19th century. Maury Henry Biddle Paul is credited with ...

in a basement room on Sheridan Square, West Village

The West Village is a neighborhood in the western section of the larger Greenwich Village neighborhood of Lower Manhattan, New York City.

The traditional boundaries of the West Village are the Hudson River to the west, West 14th Street to th ...

, New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

. Billie Holiday

Billie Holiday (born Eleanora Fagan; April 7, 1915 – July 17, 1959) was an American jazz and swing music singer. Nicknamed "Lady Day" by her friend and music partner, Lester Young, Holiday had an innovative influence on jazz music and pop si ...

sang in Café Society's opening show in 1938 and performed there for the next nine months. Josephson set down certain rules around the performance of " Strange Fruit" at the club: it would close Holiday's set; the waiters would stop serving just before it; the room would be in darkness except for a spotlight on Holiday's face; and there would be no encore.

Barney Josephson later said:

I wanted a club where blacks and whites worked together behind the footlights and sat together out front ... There wasn't, so far as I know, a place like it in New York or in the whole country.Few nightclubs permitted blacks and whites to mix in the audience. The

Cotton Club

The Cotton Club was a New York City nightclub from 1923 to 1940. It was located on 142nd Street and Lenox Avenue (1923–1936), then briefly in the midtown Theater District (1936–1940).Elizabeth Winter"Cotton Club of Harlem (1923- )" Blac ...

in Harlem was segregated, admitting only occasional black celebrities to sit at obscure tables and limiting black customers to the back of the room behind the pillars and partitions. Clubs south of Harlem, like the Kit Kat Club, did not let African Americans in at all. Segregation in the States was relentless: as Josephson told Reuters

Reuters ( ) is a news agency owned by Thomson Reuters Corporation. It employs around 2,500 journalists and 600 photojournalists in about 200 locations worldwide. Reuters is one of the largest news agencies in the world.

The agency was estab ...

in 1984, "The only way they'd let Duke Ellington

Edward Kennedy "Duke" Ellington (April 29, 1899 – May 24, 1974) was an American jazz pianist, composer, and leader of his eponymous jazz orchestra from 1923 through the rest of his life. Born and raised in Washington, D.C., Ellington was based ...

's mother in was if she was playing in the band."

HUAC

HUAC 1: no-show

On February 2, 1947, Josephson failed to appear under subpoena. He would have appeared with

On February 2, 1947, Josephson failed to appear under subpoena. He would have appeared with Gerhart Eisler

Gerhart Eisler (20 February 1897 – 21 March 1968) was a German politician, editor and publicist. Along with his sister Ruth Fischer, he was a very early member of the Austrian German Communist Party (KPDÖ) and then a prominent member of the Co ...

, Ruth Fischer

Ruth Fischer (11 December 1895 – 13 March 1961) was an Austrian and German Communist, and a co-founder of the Austrian Communist Party (KPÖ) in 1918. Along with her partner Arkadi Maslow, she led the Communist Party of Germany (KPD) through ...

(Eisler's sister), Wiliam Nowell, Louis F. Budenz, and others. On that date, the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) produced evidence that Josephson had forged his name as "Bernard A. Hirshfield" for a "Samuel Liptzen" on a passport application dated August 31, 1934, which bore a photo of Gerhart Eisler. On February 5, Josephson sent a telegram to HUAC chairman U.S. Rep. J. Parnell Thomas

John Parnell Thomas (January 16, 1895 – November 19, 1970) was a stockbroker and politician. He was elected to seven terms as a U.S. Representative from New Jersey as a Republican. He was later a convicted criminal who served nine months in fe ...

that advised, "Unable appear before your committee February 6th, due inadequate notice of less than 48 hours. Counsel advises me such short notice unreasonable and that

I am entitled to reasonable notice. Willing appear at later date fixed by you if reasonable notice given me."

Nixon's maiden speech to Congress

On February 18, 1947, freshman U.S. Representative Richard M. Nixon mentioned Josephson's name often in his maiden speech to Congress:

On February 18, 1947, freshman U.S. Representative Richard M. Nixon mentioned Josephson's name often in his maiden speech to Congress: Mr. Speaker, on February 6, when the Committee on Un-American Activities opened its session at 10 o'clock, it had by previous investigation, tied together the loose end of one chapter of a foreign-directed conspiracy whose aim and purpose was to undermine and destroy the government of the United States. The principal character of this conspiracy was Gerbert Eisler, alias Berger, alias Brown, alias Gerhart, alias Edwards, alias Liptzin, alias Eisman, a seasoned agent of the Communist International ...

Two other conspirators and comrades of Eisler, Leon Josephson and Samuel Liptzin, who were subpenaed to appear, did not appear; Josephson contended by telegram that two days was not sufficient notice for him to come from New York to Washington ... It is no wonder that Eisler refused to talk and Josephson and Liptzin did not respond to the subpenaes ...

I think I am safe I announcing to the House that the committee will deal with Mr. Josephson and Mr. Liptzin at a very early date ... Now the handwriting on this application, according to the questioned documents experts of the Treasury Department, is that of Leo Josephson; the name on this application is that of Samuel Liptzin the picture on this application is that of Gerhart Eisler; the signature of the identifying witness, Bernard A. Hirschfield, is also in the handwriting of Leon Josephson ...

HUAC 2: contempt of Congress

On March 5, 1947, several witnesses appeared before HUAC. First came the real Samuel Liptzen, accompanied by labor lawyer Edward Kuntz as counsel: both were sworn in. Liptzen was born on March 13, 1893, inLipsk :''Lipsk is also the old Slavonic form of the name of Leipzig in Germany.''

Lipsk , (also pl, Lipsk nad Biebrzą; lt, Liepinė; yi, ליפּסק נאַד בּיבּג'ו) is a town in Augustów County, Podlaskie Voivodeship, Poland, with 2,520 ...

, Russia (now Liepinė, Lithuania). In April 1909. he emigrated to the United States. On March 13, 1917, he became an American citizen. In 1920 or 1921, Liptzen became a Party member. He had been a tailor and a member of the Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America

Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America (ACWA) was a United States labor union known for its support for "social unionism" and progressive political causes. Led by Sidney Hillman for its first thirty years, it helped found the Congress of Indus ...

. Then he worked in the fur industry until he became sick from dye. Between 1926 and 1928, he traveled twice to Canada (and again in the summer of 1945). In 1928 or 1929, he ran for the New York City Assembly. In 1935, he lived in Los Angeles (while ill). For two or three years, he had worked in the offices of the ''Morning Freiheit'' (''Morgen Freiheit

Morgen Freiheit (original title: ; English: ''Morning Freedom'') was a New York City-based daily Yiddish language newspaper affiliated with the Communist Party, USA, founded by Moissaye Olgin in 1922. After the end of World War II the paper's pro- ...

'', a Yiddish language

Yiddish (, or , ''yidish'' or ''idish'', , ; , ''Yidish-Taytsh'', ) is a West Germanic language historically spoken by Ashkenazi Jews. It originated during the 9th century in Central Europe, providing the nascent Ashkenazi community with a ver ...

newspaper affiliated with the Communist Party USA

The Communist Party USA, officially the Communist Party of the United States of America (CPUSA), is a communist party in the United States which was established in 1919 after a split in the Socialist Party of America following the Russian Revo ...

and with offices in the same building as the ''Daily Worker

The ''Daily Worker'' was a newspaper published in New York City by the Communist Party USA, a formerly Comintern-affiliated organization. Publication began in 1924. While it generally reflected the prevailing views of the party, attempts were ...

'', founded by Moissaye Olgin in 1922). (Liptzen called it a "left-wing" and "progressive" newspaper.) He claimed he had been unable to appear on February 6, 1947, as required by subpoena because of the illness of "the missus with whom I have the rooms," named Mrs. Annie Halland (Holland). He also stated that he had never applied for a passport – despite a passport application in his name dated August 31, 1934. Liptzen swore on the spot: "It isn't my signature ... absolutely not," nor his photo, nor a photo of anyone he knew. Liptzen could not produce his naturalization papers, nor when he lost them due to robbery, nor exactly where he lived when his home was robbed. Liptzen also denied ever "loaning" anyone his naturalization papers or knowing Josephson or Eisler (including any of his aliases or codenames).

Attorney Edward Kuntz was representing both Liptzen and the ''Morning Freiheit''; until a few years before, he had already represented the ''Daily Worker''. Kuntz described building occupants at 35 East 12th Street in New York City: CPUSA national committee on top ninth floor, ''Daily Worker'' editorial offices on eighth, F. & D. Printing Co. on seventh, ''Morning Freiheit'' sixth, CPUSA state on fifth, ''Daily Worker'' business offices on second, and F. & D. Printing Co. presses in the basement. Kuntz explained that he had changed the legal status of the ''Freiheit'' from business to membership corporation and that there were some communists who were corporate members and contributing journalists.

Nixon resumed questioning of Liptzen thereafter, asking him how he had managed not to see Eisler in that building; Liptzen simply denied knowing him or having seen him. HUAC member U.S. Rep. Bonner resumed questioning of Kuntz to ask him more about the ''Freiheit'' and the owners of the building and corporation therein. Kuntz could tell him little other than the current head of the ''Freiheit'': "Lechovitzky." HUAC member U.S. Rep. Vail

Vail is a home rule municipality in Eagle County, Colorado, United States. The population of the town was 4,835 in 2020. Home to Vail Ski Resort, the largest ski mountain in Colorado, the town is known for its hotels, dining, and for the numer ...

resume questioning of Liptzen regarding his alleged telegram to decline appearance. Liptzen confirmed that he wrote humorous pieces for the ''Freiheit'' and had written the book ''In Spite of Tears''. (Vail exclaimed, "You arrived at the age of 17 and you still write in Jewish (Yiddish)?" Vail and Stripling resumed questioning of Kuntz, who admitted that for some years up to the early 1940s he had headed the staff of International Labor Defense

The International Labor Defense (ILD) (1925–1947) was a legal advocacy organization established in 1925 in the United States as the American section of the Comintern's International Red Aid network. The ILD defended Sacco and Vanzetti, was activ ...

(which had a peak of 250–300 volunteer labor lawyers) and was chairman of the legal committee when ILD dissolved but denied knowing Josephson there. (In 1946 the ILD merged with the National Federation for Constitutional Liberties

The National Federation for Constitutional Liberties (NFCL) (1940–c. 1946) was a civil rights advocacy group made up from a broad range of people (including many trade unionists, religious organizations, African-American civil rights advocates a ...

or NFCL and National Negro Congress The National Negro Congress (NNC) (1936–ca. 1946) was an American organization formed in 1936 at Howard University as a broadly based organization with the goal of fighting for Black liberation; it was the successor to the League of Struggle for N ...

or NNC to form the Civil Rights Congress

The Civil Rights Congress (CRC) was a United States civil rights organization, formed in 1946 at a national conference for radicals and disbanded in 1956. It succeeded the International Labor Defense, the National Federation for Constitutional Li ...

or CRC).) When asked by Stripling whether he was sympathetic to communism, Kuntz answered, "Most of it" but denied being a communist. Kuntz, who denied knowing Eisler but admitted he knew Josephson because "I used to be a habitue of Cafe Society." Their joint testimony ended with HUAC's informing Liptzen that he remained under subpoena and was "not excused" but rather subject to recall. (Stripling managed to work in mention that U.S. Rep. Vito Marcantonio

Vito is an Italian name that is derived from the Latin word "''vita''", meaning "life".

It is a modern form of the Latin name Vitus, meaning "life-giver," as in San Vito or Saint Vitus, the patron saint of dogs and a heroic figure in southern I ...

was ILD president.)

That day, Josephson also appeared under subpoena before HUAC. He refused to be sworn in due to the "unconstitutionality of this committee" and refused to answer questions. Samuel A. Newburger of New York City served as his legal counsel.

The hearing's transcript records: The Chairman: Mr. Josephson, will you stand and be sworn?As a result, Josephson was found guilty of

Mr. Josephson: I will not be sworn.

Mr.Stripling Stripling may refer to: People *Byron Stripling (born 1961), trumpet player, vocalist, & bandleader * Jon Stripling, bass player *Kathryn Stripling Byer (1944–2017), author * Randy Stripling, actor * Robert E. Stripling (died 1991), American civ ...: Will you stand?

Mr. Josephson: I will stand.

(Mr. Josephson stands.)

Mr. Stripling: Do you refuse to be sworn?

Mr. Josephson: I refuse to be sworn.

Mr. Stripling: You refuse to give testimony before this sub-committee?

Mr. Josephson: Until I have had an opportunity to determine through the courts the legality of this committee.

The Chairman: You refuse to be sworn, and you refuse to give testimony before this committee at this hearing today?

Mr. Josephson: Yes.

The appellant was then excused subject to call either by the sub-committee or the full committee.

contempt of Congress

Contempt of Congress is the act of obstructing the work of the United States Congress or one of its committees. Historically, the bribery of a U.S. senator or U.S. representative was considered contempt of Congress. In modern times, contempt of Co ...

.

HUAC 3: evidence

Café Society

Café society was the description of the "Beautiful People" and "Bright Young Things" who gathered in fashionable cafés and restaurants in New York, Paris and London beginning in the late 19th century. Maury Henry Biddle Paul is credited with ...

in 1938. He also observed that in 1946 Barney was a sponsor of "Spanish Refugee Appeal," a branch of the Joint Anti-Fascist Refugee Committee

Joint Anti-Fascist Refugee Committee (JAFRC) was a nonprofit organization to provide humanitarian aid to refugees of the Spanish Civil War.

History

In 1941, the Joint Anti-Fascist Refugee Committee was formed by Lincoln Battalion veterans of ...

(which had paid Eisler funds in 1941 under another false name). Russell then presented 1938 Dies Committee

The House Committee on Un-American Activities (HCUA), popularly dubbed the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), was an investigative committee of the United States House of Representatives, created in 1938 to investigate alleged disloy ...

testimony from John P. Frey

John Philip Frey (February 24, 1871 – November 29, 1957) was a labor activist and president of the American Federation of Labor's Metal Trades Department, AFL-CIO, Metal Trades Department during a crucial period in American labor history.

E ...

, former president of the metal trades department of the AFL

AFL may refer to:

Sports

* American Football League (AFL), a name shared by several separate and unrelated professional American football leagues:

** American Football League (1926) (a.k.a. "AFL I"), first rival of the National Football Leagu ...

that claimed that Mink had been involved in the Soviet assassination of Leon Trotsky

Lev Davidovich Bronstein. ( – 21 August 1940), better known as Leon Trotsky; uk, link= no, Лев Давидович Троцький; also transliterated ''Lyev'', ''Trotski'', ''Trotskij'', ''Trockij'' and ''Trotzky''. (), was a Russian ...

and proceeded to insert four pages of transcripts into the record that included 1938 testimony by Earl Browder

Earl Russell Browder (May 20, 1891 – June 27, 1973) was an American politician, communist activist and leader of the Communist Party USA (CPUSA). Browder was the General Secretary of the CPUSA during the 1930s and first half of the 1940s.

Duri ...

, Benjamin Gitlow

Benjamin Gitlow (December 22, 1891 – July 19, 1965) was a prominent American socialist politician of the early 20th century and a founding member of the Communist Party USA. During the end of the 1930s, Gitlow turned to conservatism and wrote t ...

, and Jay Lovestone

Jay Lovestone (15 December 1897 – 7 March 1990) was an American activist. He was at various times a member of the Socialist Party of America, a leader of the Communist Party USA, leader of a small oppositionist party, an anti-Communist and Centr ...

among others, all about Mink. Russell documented Josephson's Party membership and loyalty to the Soviet Union with quotes from his own writings, e.g., "The new Soviet constitution and electoral law are the most democratic in the world" and his dream of a "Soviet America." HUAC chief investigator Robert E. Stripling concluded "Mr. Eisler and Mr. Josephson ... are in the higher echelons of the Communist International

The Communist International (Comintern), also known as the Third International, was a Soviet-controlled international organization founded in 1919 that advocated world communism. The Comintern resolved at its Second Congress to "struggle by a ...

." Russell then showed Josephson's connection to two current Federal employees, Sol Rabkin and Milton Fischer, both of whom had affiliations with known "communist fronts" including the National Lawyers Guild

The National Lawyers Guild (NLG) is a progressive public interest association of lawyers, law students, paralegals, jailhouse lawyers, law collective members, and other activist legal workers, in the United States. The group was founded in 193 ...

(Rabkin). Stripling complained that Martin Popper had called as Josephson's lawyer to ask for extension on appearance in the subpoena, only to later deny he was representing Josephson. (Stripling observed that Popper was long-time executive secretary of the National Lawyers Guild.) Russell then proceeded to provide his report on the real Samual Liptzen. Liptzen had failed to report trips to Mexico and Canada to the FBI. He had failed to report the robbery of his naturalization papers for two years. Finally, Russell found an article in the ''Jewish Daily Forward

''The Forward'' ( yi, פֿאָרווערטס, Forverts), formerly known as ''The Jewish Daily Forward'', is an American news media organization for a American Jews, Jewish American audience. Founded in 1897 as a Yiddish-language daily socialis ...

'' (Yiddish ''Forverts'') dated March 8, 1947, that stated that Liptzen and Josephson are friends and that Liptzen had a long history in the Soviet underground, for which he was expelled from unions and wound up at the ''Freiheit''.

Alwyn Cole, Treasury examiner, reported that his examination of handwriting on the 1934 passport application revealed that the handwriting of the signature "Bernard A. Hirschfield" belonged to Leon Josephson. Cole did not find the signature "Samuel Liptzen" as confidently belonging to Gerhart Eisler, though he was confident that the real Samuel Liptzen had not signed.

Fred Erwin Beal

Fred Erwin Beal (1896–1954) was an American labor-union organizer whose critical reflections on his work and travel in the Soviet Union divided left-wing and liberal opinion. In 1929 he had been a ''cause célèbre'' when, in Gastonia, North Car ...

, indicted during the Loray Mill strike

The Loray Mill strike of 1929 in Gastonia, North Carolina, was a notable strike action in the labor history of the United States. Though largely unsuccessful in attaining its goals of better working conditions and wages, the strike was considere ...

of 1929, testified next. Josephson (with Clarence Miller of the National Textile Workers Union

National may refer to:

Common uses

* Nation or country

** Nationality – a ''national'' is a person who is subject to a nation, regardless of whether the person has full rights as a citizen

Places in the United States

* National, Maryland, c ...

and Juliet Stuart Poyntz

Juliet Stuart Poyntz (originally 'Points') (25 November 1886 – 1937) was an American suffragist, trade unionist and communist spy. As a student and university teacher, Poyntz espoused many radical causes and went on to become a co-founder o ...

of the International Labor Defense

The International Labor Defense (ILD) (1925–1947) was a legal advocacy organization established in 1925 in the United States as the American section of the Comintern's International Red Aid network. The ILD defended Sacco and Vanzetti, was activ ...

) had helped arrange false passports for many of those indicted, including himself, and helped them flee to the Soviet Union. Beal saw Josephson in Moscow several times and knew him to be a GPU

A graphics processing unit (GPU) is a specialized electronic circuit designed to manipulate and alter memory to accelerate the creation of images in a frame buffer intended for output to a display device. GPUs are used in embedded systems, mobi ...

agent. After some years, Beal returned to the States, although he faced possible re-arrest and imprisonment, rather than stay in the USSR. Josephson, William Z. Foster, and other high-level communists persuaded Beal to return to Moscow. He saw George Mink there several times. Again he left: in 1940, he was serving four years in the Raleigh Penitentiary, where the FBI visited him several times.

Columnists like Dorothy Kilgallen

Dorothy Mae Kilgallen (July 3, 1913 – November 8, 1965) was an American columnist, journalist, and television game show panelist. After spending two semesters at the College of New Rochelle, she started her career shortly before her 18th birth ...

, Lee Mortimer Lee Mortimer (1904–1963) was an American newspaper columnist, radio commentator, crime lecturer, night club show producer, and author.

He was born Mortimer Lieberman in Chicago, but was best known by the pen name he adopted as a young newspa ...

, Westbrook Pegler

Francis James Westbrook Pegler (August 2, 1894 – June 24, 1969) was an American journalist and writer. He was a popular columnist in the 1930s and 1940s famed for his opposition to the New Deal and labor unions. Pegler aimed his pen at president ...

, and Walter Winchell

Walter Winchell (April 7, 1897 – February 20, 1972) was a syndicated American newspaper gossip columnist and radio news commentator. Originally a vaudeville performer, Winchell began his newspaper career as a Broadway reporter, critic and co ...

attacked. Within weeks of these attacks, business at Café Society fell away, and his brother Barney had to sell.

HUAC 4: evidence

On October 28, 1953, Josephson with attorney Samuel Neuberger again appeared under subpoena before HUAC. He told the Committee that he was working with his brother "Warren Josephson" in his brother's restaurant, rather than state Barney Josephson andCafe Society

A coffeehouse, coffee shop, or café is an establishment that primarily serves coffee of various types, notably espresso, latte, and cappuccino. Some coffeehouses may serve cold drinks, such as iced coffee and iced tea, as well as other non-caf ...

. Josephson confirmed that he had worked in fact at both uptown and downtown branches of Cafe Society. He refused to confirm whether he had associated in the mid-1930s with George Mink or whether he had traveled with Mink to Copenhagen, or whether Danish police had arrested them there as Soviet spies, etc. Louise Bransten with attorney Joseph Forer

Joseph Forer (11 August 1910 – 20 June 1986) was a 20th-century American attorney who, with partner David Rein, supported Progressive causes, including discriminated communists and African-Americans. Forer was one of the founders of the Nation ...

immediately followed him on the stand.

Espionage: Rosenberg Case

According to the 2007 book ''Spies'', Josephson and

According to the 2007 book ''Spies'', Josephson and John L. Spivak

John Louis Spivak (June 13, 1897 – September 30, 1981) was an American socialist and later communist reporter and author, who wrote about the problems of the working class, racism, and the spread of fascism in Europe and the United States. Most ...

"burglarized" the offices of labor lawyer O. John Rogge, attorney for David Greenglass

David Greenglass (March 2, 1922 – July 1, 2014) was an atomic spy for the Soviet Union who worked on the Manhattan Project. He was briefly stationed at the Clinton Engineer Works uranium enrichment facility at Oak Ridge, Tennessee, and then ...

, and stole papers later published by the Communist Party to discredit Greenglass in his testimony in the Rosenberg Case.

Later life

From 1952 to 1956, Josephson taught Soviet Law at theJefferson School of Social Science The Jefferson School of Social Science was an adult education institution of the Communist Party USA located in New York City. The so-called "Jeff School" was launched in 1944 as a successor to the party's New York Workers School, albeit skewed mo ...

.

Personal life and death

Josephson married Lucy Wishart in 1945; they had two children. Josephson died in February 1966 of a "massive heart attack."Works

Shortly after his HUAC testimony, Josephson publicly avowed membership in the

Shortly after his HUAC testimony, Josephson publicly avowed membership in the Communist Party USA

The Communist Party USA, officially the Communist Party of the United States of America (CPUSA), is a communist party in the United States which was established in 1919 after a split in the Socialist Party of America following the Russian Revo ...

in the influential leftist journal, the ''New Masses

''New Masses'' (1926–1948) was an American Marxist magazine closely associated with the Communist Party USA. It succeeded both ''The Masses'' (1912–1917) and ''The Liberator''. ''New Masses'' was later merged into '' Masses & Mainstream'' (19 ...

''.

* "The New Soviet Electoral Law," ''The Communist'' (1937)

* "I Am A Communist," ''New Masses

''New Masses'' (1926–1948) was an American Marxist magazine closely associated with the Communist Party USA. It succeeded both ''The Masses'' (1912–1917) and ''The Liberator''. ''New Masses'' was later merged into '' Masses & Mainstream'' (19 ...

'' (1947)

* ''The Individual in Soviet Law'' (1957)

See also

* Barney Josephson *Alexander Ulanovsky

Alexander Ulanovsky (1891–1970) was the chief illegal "rezident" for Soviet Military Intelligence (GRU), who was rezident in the United States 1931–1932 with his wife and was imprisoned in the 1950s with his family in the Soviet gulag.

Earl ...

* International Labor Defense

The International Labor Defense (ILD) (1925–1947) was a legal advocacy organization established in 1925 in the United States as the American section of the Comintern's International Red Aid network. The ILD defended Sacco and Vanzetti, was activ ...

* ''Morgen Freiheit

Morgen Freiheit (original title: ; English: ''Morning Freedom'') was a New York City-based daily Yiddish language newspaper affiliated with the Communist Party, USA, founded by Moissaye Olgin in 1922. After the end of World War II the paper's pro- ...

''

* ''Daily Worker

The ''Daily Worker'' was a newspaper published in New York City by the Communist Party USA, a formerly Comintern-affiliated organization. Publication began in 1924. While it generally reflected the prevailing views of the party, attempts were ...

''

References

External links

*University of Massachusetts Library (Credo)

Civil Rights Congress

The Civil Rights Congress (CRC) was a United States civil rights organization, formed in 1946 at a national conference for radicals and disbanded in 1956. It succeeded the International Labor Defense, the National Federation for Constitutional Li ...

(U.S.) – United States of America v. Leon Josephson dissenting opinion press release (December 12, 1947)

{{DEFAULTSORT:Josephson, Leon

1898 births

1966 deaths

American trade union leaders

20th-century American lawyers

American political activists

Members of the Communist Party USA

Lawyers from New York City

Prisoners and detainees of the United States federal government

American spies for the Soviet Union

Espionage in the United States

American communists

Date of death missing

Place of death missing