Leo Baekeland on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

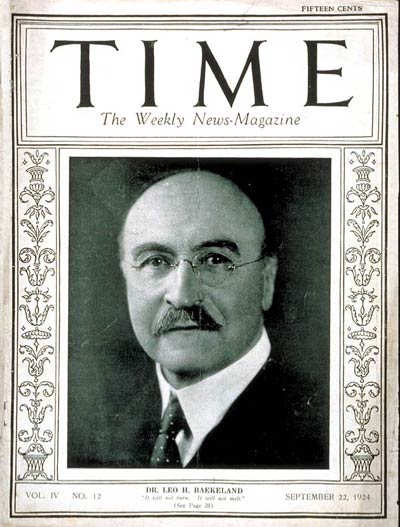

Leo Hendrik Baekeland (November 14, 1863 – February 23, 1944) was a Belgian chemist. He is best known for the inventions of Velox

In 1889, Baekeland and his wife Céline took advantage of a travel scholarship to visit universities in England and the United States. They visited

In 1889, Baekeland and his wife Céline took advantage of a travel scholarship to visit universities in England and the United States. They visited

The invention of Bakelite marks the beginning of the age of plastics. Bakelite was the first plastic invented that retained its shape after being heated.

The invention of Bakelite marks the beginning of the age of plastics. Bakelite was the first plastic invented that retained its shape after being heated.

Plastics Hall of Fame

in 1974. At the time of Baekeland's death in 1944, the world production of Bakelite was ca. 175,000 tons, and it was used in over 15,000 different products. He held more than 100 patents, including processes for the separation of

As Baekeland grew older he became more eccentric, entering fierce battles with his son and presumptive heir over salary and other issues. He sold the General Bakelite Company to

As Baekeland grew older he became more eccentric, entering fierce battles with his son and presumptive heir over salary and other issues. He sold the General Bakelite Company to

online review

*

Amsterdam Bakelite Collection Foundation

The Baekeland fundA virtual Bakelite museum with a short biography of Leo BaekelandVirtual Bakelite Museum of Ghent 1907–2007National Academy of Sciences Biographical MemoirNPR. Oil #4: How Oil Got Into Everything

Retrieved August 19, 2016. {{DEFAULTSORT:Baekeland, Leo 1863 births 1944 deaths 19th-century American inventors 20th-century American inventors Columbia University faculty 20th-century Belgian inventors Belgian emigrants to the United States Belgian chemists American chemists People from Miami Scientists from Ghent People from Yonkers, New York American people of Flemish descent Polymer scientists and engineers Ghent University alumni Burials at Sleepy Hollow Cemetery People from Beacon, New York Scientists from New York (state) Presidents of the Electrochemical Society

photographic paper

Photographic paper is a paper coated with a light-sensitive chemical formula, like photographic film, used for making photographic prints. When photographic paper is exposed to light, it captures a latent image that is then developed to form a v ...

in 1893, and Bakelite

Polyoxybenzylmethylenglycolanhydride, better known as Bakelite ( ), is a thermosetting phenol formaldehyde resin, formed from a condensation reaction of phenol with formaldehyde. The first plastic made from synthetic components, it was developed ...

in 1907. He has been called "The Father of the Plastics Industry" for his invention of Bakelite, an inexpensive, non-flammable and versatile plastic

Plastics are a wide range of synthetic or semi-synthetic materials that use polymers as a main ingredient. Their plasticity makes it possible for plastics to be moulded, extruded or pressed into solid objects of various shapes. This adaptab ...

, which marked the beginning of the modern plastics industry.

Early life

Leo Baekeland was born inGhent

Ghent ( nl, Gent ; french: Gand ; traditional English: Gaunt) is a city and a municipality in the Flemish Region of Belgium. It is the capital and largest city of the East Flanders province, and the third largest in the country, exceeded in ...

, Belgium, on November 14, 1863, the son of a cobbler

Cobbler(s) may refer to:

*A person who Shoemaking, repairs, and sometimes makes, shoes

Places

* The Cobbler, a mountain located near the head of Loch Long in Scotland

* Mount Cobbler, Australia

Art, entertainment and media

* The Cobbler (1923 ...

, Charles Baekeland, and a house maid, Rosalia Merchie. His siblings were: Elodia Maria Baekeland; Melonia Leonia Baekeland; Edmundus Baekeland; Rachel Helena Baekeland and Delphina Baekeland.

He told ''The Literary Digest

''The Literary Digest'' was an influential American general interest weekly magazine published by Funk & Wagnalls. Founded by Isaac Kaufmann Funk in 1890, it eventually merged with two similar weekly magazines, ''Public Opinion'' and '' Current O ...

'': "The name is a Dutch word meaning 'Land of Beacons.'" He spent much of his early life in Ghent, Belgium

Ghent ( nl, Gent ; french: Gand ; traditional English: Gaunt) is a city and a municipality in the Flemish Region of Belgium. It is the capital and largest city of the East Flanders province, and the third largest in the country, exceeded in ...

. Proudly, he graduated with honours from the Ghent Municipal Technical School and was awarded a scholarship by the City of Ghent to study chemistry at the Ghent University

Ghent University ( nl, Universiteit Gent, abbreviated as UGent) is a public research university located in Ghent, Belgium.

Established before the state of Belgium itself, the university was founded by the Dutch King William I in 1817, when the ...

, which he entered in 1880. He acquired a PhD ''summa cum laude'' at the age of 21. After a brief appointment as Professor of Physics and Chemistry at the Government Higher Normal School in Bruges

Bruges ( , nl, Brugge ) is the capital and largest City status in Belgium, city of the Provinces of Belgium, province of West Flanders in the Flemish Region of Belgium, in the northwest of the country, and the sixth-largest city of the countr ...

(1887–1889), he was appointed associate professor of chemistry at Ghent University

Ghent University ( nl, Universiteit Gent, abbreviated as UGent) is a public research university located in Ghent, Belgium.

Established before the state of Belgium itself, the university was founded by the Dutch King William I in 1817, when the ...

in 1889.

Personal life

Baekeland married (1868–1944) on August 8, 1889, and they had two children. One of their grandsons, Brooks (whose father was George Washington Baekeland) married the model Barbara Daly a.k.a.Barbara Daly Baekeland

Barbara Daly Baekeland (September 28, 1921 – November 17, 1972) was a wealthy American socialite who was murdered by her son, Antony "Tony" Baekeland. She was the ex-wife of Brooks Baekeland, who was the grandson of Leo Baekeland, inventor of B ...

in 1942 and had one child, a boy named Anthony "Tony" Baekeland.

Career

In 1889, Baekeland and his wife Céline took advantage of a travel scholarship to visit universities in England and the United States. They visited

In 1889, Baekeland and his wife Céline took advantage of a travel scholarship to visit universities in England and the United States. They visited New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

, where he met Professor Charles F. Chandler

Charles Frederick Chandler (December 6, 1836 – August 25, 1925) was an American chemist, best known for his regulatory work in public health, sanitation, and consumer safety in New York City, as well as his work in chemical education—first a ...

of Columbia University

Columbia University (also known as Columbia, and officially as Columbia University in the City of New York) is a private research university in New York City. Established in 1754 as King's College on the grounds of Trinity Church in Manhatt ...

and Richard Anthony, of the E. and H.T. Anthony photographic company. Professor Chandler was influential in convincing Baekeland to stay in the United States. Baekeland had already invented a process to develop photographic plates using water instead of other chemicals, which he had patented in Belgium in 1887. Although this method was unreliable, Anthony saw potential in the young chemist and offered him a job.

Baekeland worked for the Anthony company for two years, and in 1891, set up in business for himself working as a consulting chemist. However, a spell of illness and disappearing funds made him rethink his actions and he decided to return to his old interest of producing a photographic paper that would allow enlargements to be printed by artificial light. After two years of intensive effort, he perfected the process to produce the paper, which he named "Velox"; it was the first commercially successful photographic paper. At the time, the US was suffering a recession and there were no investors or buyers for his proposed new product, so Baekeland became partners with Leonard Jacobi and established the Nepera Chemical Company in Nepera Park, Yonkers, New York

Yonkers () is a city in Westchester County, New York, United States. Developed along the Hudson River, it is the third most populous city in the state of New York, after New York City and Buffalo. The population of Yonkers was 211,569 as enu ...

.

In 1899, Jacobi, Baekeland, and Albert Hahn, a further associate, sold Nepera to George Eastman of the Eastman Kodak Co. for $750,000. Baekeland earned approximately $215,000 net through the transaction.

With a portion of the money he purchased "Snug Rock", a house in Yonkers, New York, where he set up his own well-equipped laboratory. There, he later said, "in comfortable financial circumstances, a free man, ready to devote myself again to my favorite studies... I enjoyed for several years that great blessing, the luxury of not being interrupted in one's favorite work."

One of the requirements of the Nepera sale was, in effect, a non-compete clause

In contract law, a non-compete clause (often NCC), restrictive covenant, or covenant not to compete (CNC), is a clause under which one party (usually an employee) agrees not to enter into or start a similar profession or trade in competition agains ...

: Baekeland agreed not to do research in photography for at least 20 years. He would have to find a new area of research. His first step was to go to Germany in 1900, for a "refresher in electrochemistry" at the Technical Institute at Charlottenburg.

Upon returning to the United States, Baekeland was involved briefly but successfully in helping Clinton Paul Townsend and Elon Huntington Hooker to develop a production-quality electrolytic cell. Baekeland was hired as an independent consultant, with the responsibility of constructing and operating a pilot plant. Baekeland developed a stronger diaphragm cell for the chloralkali process

The chloralkali process (also chlor-alkali and chlor alkali) is an industrial process for the electrolysis of sodium chloride (NaCl) solutions. It is the technology used to produce chlorine and sodium hydroxide (caustic soda), which are comm ...

, using woven asbestos

Asbestos () is a naturally occurring fibrous silicate mineral. There are six types, all of which are composed of long and thin fibrous crystals, each fibre being composed of many microscopic "fibrils" that can be released into the atmosphere b ...

cloth filled with a mixture of iron oxide

Iron oxides are chemical compounds composed of iron and oxygen. Several iron oxides are recognized. All are black magnetic solids. Often they are non-stoichiometric. Oxyhydroxides are a related class of compounds, perhaps the best known of whic ...

, asbestos fibre, and iron hydroxide

Iron oxides are chemical compounds composed of iron and oxygen. Several iron oxides are recognized. All are black magnetic solids. Often they are non-stoichiometric. Oxyhydroxides are a related class of compounds, perhaps the best known of which ...

. Baekeland's improvements were important to the founding of Hooker Chemical Company

Hooker Chemical Company (or Hooker Electrochemical Company) was an American firm producing chloralkali products from 1903 to 1968. In 1922, bought the S. Wander & Sons Company to sell lye and chlorinated lime. The company became notorious in ...

and the construction of one of the world's largest electrochemical plants, at Niagara Falls

Niagara Falls () is a group of three waterfalls at the southern end of Niagara Gorge, spanning the border between the province of Ontario in Canada and the state of New York in the United States. The largest of the three is Horseshoe Falls, ...

.

Invention of Bakelite

Having been successful with Velox, Baekeland set out to find another promising area for chemical development. As he had done with Velox, he looked for a problem that offered "the best chance for the quickest possible results". Asked why he entered the field ofsynthetic resin

Synthetic resins are industrially produced resins, typically viscous substances that convert into rigid polymers by the process of curing. In order to undergo curing, resins typically contain reactive end groups, such as acrylates or epoxides. ...

s, Baekeland answered that his intention was to make money. By the 1900s, chemists had begun to recognize that many of the natural resins and fibers were polymer

A polymer (; Greek '' poly-'', "many" + ''-mer'', "part")

is a substance or material consisting of very large molecules called macromolecules, composed of many repeating subunits. Due to their broad spectrum of properties, both synthetic a ...

ic, a term introduced in 1833 by Jöns Jacob Berzelius

Baron Jöns Jacob Berzelius (; by himself and his contemporaries named only Jacob Berzelius, 20 August 1779 – 7 August 1848) was a Swedish chemist. Berzelius is considered, along with Robert Boyle, John Dalton, and Antoine Lavoisier, to be on ...

. Adolf von Baeyer

Johann Friedrich Wilhelm Adolf von Baeyer (; 31 October 1835 – 20 August 1917) was a German chemist who synthesised indigo and developed a nomenclature for cyclic compounds (that was subsequently extended and adopted as part of the IUPAC org ...

had experimented with phenols and formaldehydes in 1872, particularly Pyrogallol

Pyrogallol is an organic compound with the formula C6H3(OH)3. It is a water-soluble, white solid although samples are typically brownish because of its sensitivity toward oxygen. It is one of three isomers of benzenetriols.

Production and react ...

and benzaldehyde. He created a "black guck" which he considered useless and irrelevant to his search for synthetic dyes. Baeyer's student, Werner Kleeberg, experimented with phenol and formaldehyde in 1891, but as Baekeland noted "could not crystallize this mess, nor purify it to constant composition, nor in fact do anything with it once produced".

Baekeland began to investigate the reactions of phenol

Phenol (also called carbolic acid) is an aromatic organic compound with the molecular formula . It is a white crystalline solid that is volatile. The molecule consists of a phenyl group () bonded to a hydroxy group (). Mildly acidic, it req ...

and formaldehyde

Formaldehyde ( , ) (systematic name methanal) is a naturally occurring organic compound with the formula and structure . The pure compound is a pungent, colourless gas that polymerises spontaneously into paraformaldehyde (refer to section F ...

. He familiarized himself with previous work and approached the field systematically, carefully controlling and examining the effects of temperature, pressure, and the types and proportions of materials used.

The first application that appeared promising was the development of a synthetic replacement for shellac

Shellac () is a resin secreted by the female lac bug on trees in the forests of India and Thailand. It is processed and sold as dry flakes and dissolved in alcohol to make liquid shellac, which is used as a brush-on colorant, food glaze and ...

(made from the secretion of lac beetles). Baekeland produced a soluble phenol-formaldehyde shellac called "Novolak

Novolaks (sometimes: novolacs) are low molecular weight polymers derived from phenols and formaldehyde. They are related to Bakelite, which is more highly crosslinked. The term comes from Swedish "lack" for lacquer and Latin "novo" for new, sin ...

" but concluded that its properties were inferior. It never became a big market success, but is still used to this day (e. g. as a photoresist

A photoresist (also known simply as a resist) is a light-sensitive material used in several processes, such as photolithography and photoengraving, to form a patterned coating on a surface. This process is crucial in the electronic industry.

T ...

).

Baekeland continued to explore possible combinations of phenol and formaldehyde, intrigued by the possibility that such materials could be used in molding. By controlling the pressure and temperature applied to phenol and formaldehyde, he produced his dreamed-of hard moldable plastic: Bakelite

Polyoxybenzylmethylenglycolanhydride, better known as Bakelite ( ), is a thermosetting phenol formaldehyde resin, formed from a condensation reaction of phenol with formaldehyde. The first plastic made from synthetic components, it was developed ...

. Bakelite was made from phenol

Phenol (also called carbolic acid) is an aromatic organic compound with the molecular formula . It is a white crystalline solid that is volatile. The molecule consists of a phenyl group () bonded to a hydroxy group (). Mildly acidic, it req ...

, then known as carbolic acid, and formaldehyde

Formaldehyde ( , ) (systematic name methanal) is a naturally occurring organic compound with the formula and structure . The pure compound is a pungent, colourless gas that polymerises spontaneously into paraformaldehyde (refer to section F ...

. The chemical name of Bakelite is polyoxybenzylmethylenglycolanhydride. In compression molding, the resin is generally combined with fillers such as wood or asbestos

Asbestos () is a naturally occurring fibrous silicate mineral. There are six types, all of which are composed of long and thin fibrous crystals, each fibre being composed of many microscopic "fibrils" that can be released into the atmosphere b ...

, before pressing it directly into the final shape of the product. Baekeland's process patent for making insoluble products of phenol and formaldehyde was filed in July 1907, and granted on December 7, 1909. In February 1909, Baekeland officially announced his achievement at a meeting of the New York section of the American Chemical Society

The American Chemical Society (ACS) is a scientific society based in the United States that supports scientific inquiry in the field of chemistry. Founded in 1876 at New York University, the ACS currently has more than 155,000 members at all d ...

.

In 1917, Baekeland became a professor by special appointment at Columbia University

Columbia University (also known as Columbia, and officially as Columbia University in the City of New York) is a private research university in New York City. Established in 1754 as King's College on the grounds of Trinity Church in Manhatt ...

. The Smithsonian contains documents from the County of Westchester Courthouse in White Plains, New York, indicating that he was admitted to U. S. Citizenship on December 16, 1919.

In 1922, after patent litigation favorable to Baekeland, the General Bakelite Co., which he had founded in 1910, along with the Condensite Co. founded by Aylesworth, and the Redmanol Chemical Products Company

Redmanol Chemical Products Company was an early plastics manufacturer formed in 1913. Lawrence V. Redman was its president. In 1922, the Redmanol Company, the Condensite Company of America, and General Bakelite were consolidated into the Bakelit ...

founded by Lawrence V. Redman, were merged into the Bakelite Corporation.

The invention of Bakelite marks the beginning of the age of plastics. Bakelite was the first plastic invented that retained its shape after being heated.

The invention of Bakelite marks the beginning of the age of plastics. Bakelite was the first plastic invented that retained its shape after being heated. Radio

Radio is the technology of signaling and communicating using radio waves. Radio waves are electromagnetic waves of frequency between 30 hertz (Hz) and 300 gigahertz (GHz). They are generated by an electronic device called a transmit ...

s, telephone

A telephone is a telecommunications device that permits two or more users to conduct a conversation when they are too far apart to be easily heard directly. A telephone converts sound, typically and most efficiently the human voice, into e ...

s and electrical insulator

An electrical insulator is a material in which electric current does not flow freely. The atoms of the insulator have tightly bound electrons which cannot readily move. Other materials—semiconductors and conductors—conduct electric current ...

s were made of Bakelite because of its excellent electrical insulation and heat-resistance. Soon, its applications spread to most branches of industry.

Baekeland received many awards and honors, including the Perkin Medal

The Perkin Medal is an award given annually by the Society of Chemical Industry (American Section) to a scientist residing in America for an "innovation in applied chemistry resulting in outstanding commercial development." It is considered the ...

in 1916 and the Franklin Medal

The Franklin Medal was a science award presented from 1915 until 1997 by the Franklin Institute

The Franklin Institute is a science museum and the center of science education and research in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. It is named after the Am ...

in 1940. In 1978, he was posthumously inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame

The National Inventors Hall of Fame (NIHF) is an American not-for-profit organization, founded in 1973, which recognizes individual engineers and inventors who hold a U.S. patent of significant technology. Besides the Hall of Fame, it also opera ...

at Akron, Ohio

Akron () is the fifth-largest city in the U.S. state of Ohio and is the county seat of Summit County, Ohio, Summit County. It is located on the western edge of the Glaciated Allegheny Plateau, about south of downtown Cleveland. As of the 2020 C ...

. He was inducted into thPlastics Hall of Fame

in 1974. At the time of Baekeland's death in 1944, the world production of Bakelite was ca. 175,000 tons, and it was used in over 15,000 different products. He held more than 100 patents, including processes for the separation of

copper

Copper is a chemical element with the symbol Cu (from la, cuprum) and atomic number 29. It is a soft, malleable, and ductile metal with very high thermal and electrical conductivity. A freshly exposed surface of pure copper has a pinkis ...

and cadmium

Cadmium is a chemical element with the symbol Cd and atomic number 48. This soft, silvery-white metal is chemically similar to the two other stable metals in group 12, zinc and mercury. Like zinc, it demonstrates oxidation state +2 in most of ...

, and for the impregnation of wood.

Decline and death

Union Carbide

Union Carbide Corporation is an American chemical corporation wholly owned subsidiary (since February 6, 2001) by Dow Chemical Company. Union Carbide produces chemicals and polymers that undergo one or more further conversions by customers befo ...

in 1939 and, at his son's prompting, he retired. He became a recluse, eating all of his meals from cans and becoming obsessed with developing an immense tropical garden on his winter estate in Coconut Grove, Florida

Coconut Grove, also known colloquially as The Grove, is the oldest continuously inhabited neighborhood of Miami in Miami-Dade County, Florida. The neighborhood is roughly bound by North Prospect Drive to the south, LeJeune Road to the west, S ...

. He died of a stroke

A stroke is a medical condition in which poor blood flow to the brain causes cell death. There are two main types of stroke: ischemic, due to lack of blood flow, and hemorrhagic, due to bleeding. Both cause parts of the brain to stop functionin ...

in a sanatorium in Beacon, New York, in 1944. Baekeland is buried in Sleepy Hollow Cemetery

Sleepy Hollow Cemetery in Sleepy Hollow, New York, is the final resting place of numerous famous figures, including Washington Irving, whose 1820 short story "The Legend of Sleepy Hollow" is set in the adjacent burying ground at the Old Dutch C ...

in Sleepy Hollow, New York

Sleepy Hollow is a village in the town of Mount Pleasant, in Westchester County, New York, United States. The village is located on the east bank of the Hudson River, about north of New York City, and is served by the Philipse Manor stop on ...

.

Children

Jenny Nina Rose Baekeland (October 9, 1890 – 1895) George Washington Baekeland (February 8, 1895 – January 31, 1966) Nina Baekeland (July 22, 1896 – May 19, 1975)References

Further reading

* * Mercelis, Joris. (2020) ''Beyond Bakelite: Leo Baekeland and the Business of Science and Invention'' (MIT Press, 2020online review

*

External links

Amsterdam Bakelite Collection Foundation

The Baekeland fund

Retrieved August 19, 2016. {{DEFAULTSORT:Baekeland, Leo 1863 births 1944 deaths 19th-century American inventors 20th-century American inventors Columbia University faculty 20th-century Belgian inventors Belgian emigrants to the United States Belgian chemists American chemists People from Miami Scientists from Ghent People from Yonkers, New York American people of Flemish descent Polymer scientists and engineers Ghent University alumni Burials at Sleepy Hollow Cemetery People from Beacon, New York Scientists from New York (state) Presidents of the Electrochemical Society