Le Règne Animal on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Le Règne Animal'' (The Animal Kingdom) is the most famous work of the French naturalist

Georges Cuvier

Jean Léopold Nicolas Frédéric, Baron Cuvier (; 23 August 1769 – 13 May 1832), known as Georges Cuvier, was a French natural history, naturalist and zoology, zoologist, sometimes referred to as the "founding father of paleontology". Cuvier ...

. It sets out to describe the natural structure of the whole of the animal kingdom based on comparative anatomy

Comparative anatomy is the study of similarities and differences in the anatomy of different species. It is closely related to evolutionary biology and phylogeny (the evolution of species).

The science began in the classical era, continuing in t ...

, and its natural history. Cuvier divided the animals into four ''embranchements'' ("Branches", roughly corresponding to phyla), namely vertebrates, molluscs, articulated animals (arthropods and annelids), and zoophytes (cnidaria and other phyla).

The work appeared in four octavo volumes in December 1816 (although it has "1817" on the title pages); a second edition in five volumes was brought out in 1829–1830 and a third, written by twelve "disciples" of Cuvier, in 1836–1849. In this classic work, Cuvier presented the results of his life's research into the structure of living and fossil animals. With the exception of the section on insects, in which he was assisted by his friend Pierre André Latreille, the whole of the work was his own. It was translated into English many times, often with substantial notes and supplementary material updating the book in accordance with the expansion of knowledge. It was also translated into German, Italian and other languages, and abridged in versions for children.

''Le Règne Animal'' was influential in being widely read, and in presenting accurate descriptions of groups of related animals, such as the living elephants

Elephants are the largest existing land animals. Three living species are currently recognised: the African bush elephant, the African forest elephant, and the Asian elephant. They are the only surviving members of the family Elephantidae and ...

and the extinct mammoths, providing convincing evidence for evolutionary change to readers including Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English natural history#Before 1900, naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all speci ...

, although Cuvier himself rejected the possibility of evolution.

Context

As a boy,Georges Cuvier

Jean Léopold Nicolas Frédéric, Baron Cuvier (; 23 August 1769 – 13 May 1832), known as Georges Cuvier, was a French natural history, naturalist and zoology, zoologist, sometimes referred to as the "founding father of paleontology". Cuvier ...

(1769-1832) read the Comte de Buffon's '' Histoire Naturelle'' from the previous century, as well as Linnaeus and Fabricius Fabricius ( la, smith, german: Schmied, Schmidt) is a surname. Notable people with the surname include:

*people from the Ancient Roman gens Fabricia:

**Gaius Fabricius Luscinus, the first of the Fabricii to move to Rome

* Johann Goldsmid (1587� ...

. He was brought to Paris by Étienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire in 1795, not long after the French Revolution. He soon became a professor of animal anatomy at the Musée National d'Histoire Naturelle

The French National Museum of Natural History, known in French as the ' (abbreviation MNHN), is the national natural history museum of France and a ' of higher education part of Sorbonne Universities. The main museum, with four galleries, is loc ...

, surviving changes of government from revolutionary to Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

ic to monarchy. Essentially on his own he created the discipline of vertebrate palaeontology and the accompanying comparative method. He demonstrated that animals had become extinct

Extinction is the termination of a kind of organism or of a group of kinds (taxon), usually a species. The moment of extinction is generally considered to be the death of the last individual of the species, although the capacity to breed and ...

.

In an earlier attempt to improve the classification of animals, Cuvier transferred the concepts of Antoine-Laurent de Jussieu

Antoine-Laurent de Lavoisier ( , ; ; 26 August 17438 May 1794),

CNRS (

CNRS (

botany to zoology. In 1795, from a "fixist" perspective (denying the possibility of evolution), Cuvier divided Linnaeus's two unsatisfactory classes ("insects" and "worms") into six classes of "white-blooded animals" or invertebrates: molluscs, crustaceans, insects and worms (differently understood), echinoderms and zoophytes. Cuvier divided the molluscs into three orders: cephalopods, gastropods and acephala. Still not satisfied, he continued to work on animal classification, culminating over twenty years later in the ''Règne Animal''.

For the ''Règne Animal'', using evidence from comparative anatomy and

For the ''Règne Animal'', using evidence from comparative anatomy and

*''Le Règne Animal distribué d'après son organisation, pour servir de base à l'histoire naturelle des animaux et d'introduction à l'anatomie comparée'' (1st edition, 4 volumes, 1816) (Volumes I, II and IV by Cuvier; Volume III by Pierre André Latreille)

* --- (2nd edition, 5 volumes, 1829–1830)

* --- (3rd edition, 22 volumes, 1836–1849) known as the "Disciples edition"

The twelve "disciples" who contributed to the 3rd edition were

*''Le Règne Animal distribué d'après son organisation, pour servir de base à l'histoire naturelle des animaux et d'introduction à l'anatomie comparée'' (1st edition, 4 volumes, 1816) (Volumes I, II and IV by Cuvier; Volume III by Pierre André Latreille)

* --- (2nd edition, 5 volumes, 1829–1830)

* --- (3rd edition, 22 volumes, 1836–1849) known as the "Disciples edition"

The twelve "disciples" who contributed to the 3rd edition were

Each section, such as on reptiles at the start of Volume II (and the entire work) is introduced with an essay on distinguishing aspects of their zoology. In the case of the reptiles, the essay begins with the observation that their circulation is so arranged that only part of the blood pumped by the heart goes through the lungs; Cuvier discusses the implications of this arrangement, next observing that they have a relatively small brain compared to the mammals and birds, and that none of them incubate their eggs.

Next, Cuvier identifies the taxonomic divisions of the group, in this case four orders of reptiles, the chelonians ( tortoises and turtles), saurians (

Each section, such as on reptiles at the start of Volume II (and the entire work) is introduced with an essay on distinguishing aspects of their zoology. In the case of the reptiles, the essay begins with the observation that their circulation is so arranged that only part of the blood pumped by the heart goes through the lungs; Cuvier discusses the implications of this arrangement, next observing that they have a relatively small brain compared to the mammals and birds, and that none of them incubate their eggs.

Next, Cuvier identifies the taxonomic divisions of the group, in this case four orders of reptiles, the chelonians ( tortoises and turtles), saurians (

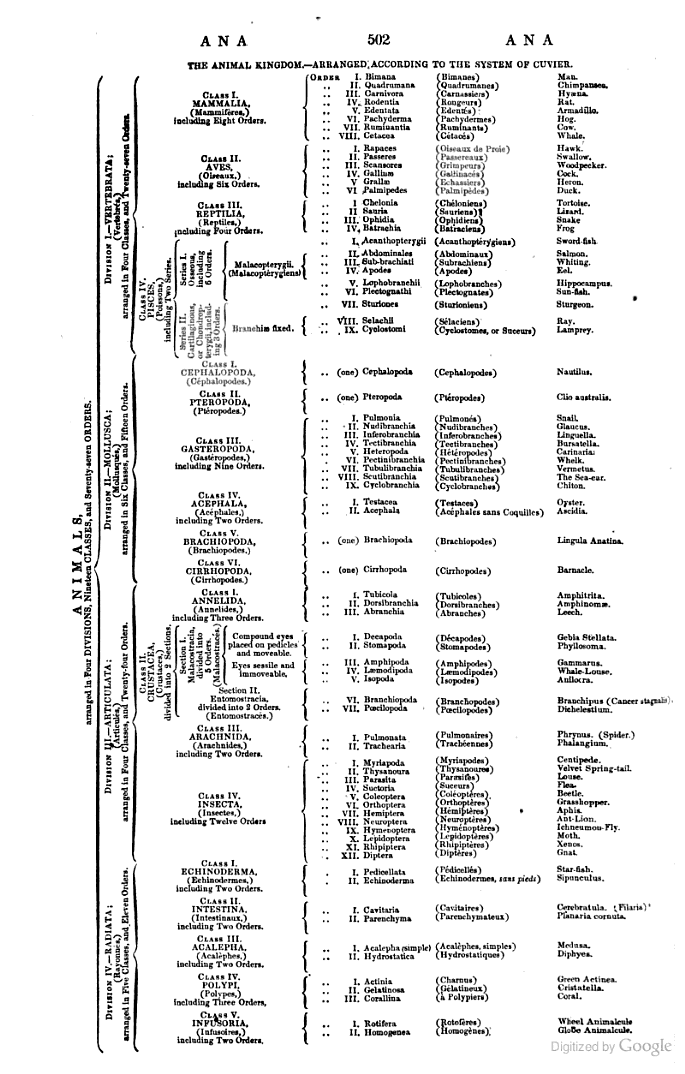

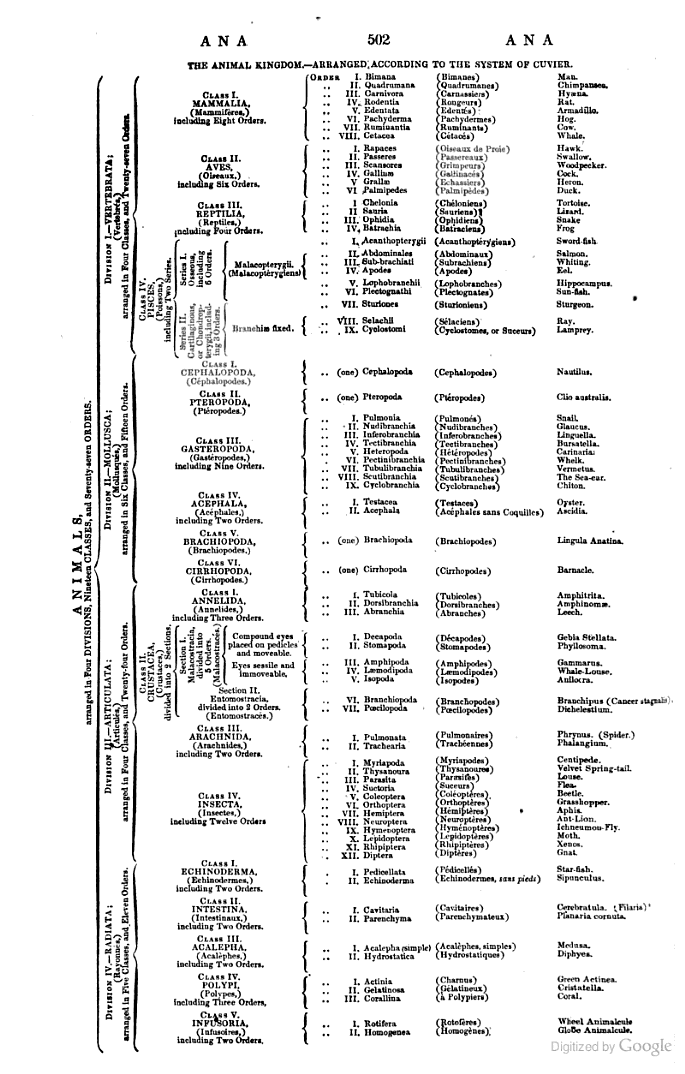

The classification adopted by Cuvier to define the natural structure of the animal kingdom, including both living and fossil forms, was as follows, the list forming the structure of the ''Règne Animal''. Where Cuvier's group names correspond (more or less) to modern taxa, these are named, in English if possible, in parentheses. The table from the 1828 '' Penny Cyclopaedia'' indicates species that were thought to belong to each group in Cuvier's taxonomy. The four major divisions were known as ''embranchements'' ("branches").

* I. Vertébrés. ( Vertebrates)

** Mammifères ( Mammals): 1. Bimanes, 2. Quadrumanes, 3. Carnassiers ( Carnivores), 4. Rongeurs (

The classification adopted by Cuvier to define the natural structure of the animal kingdom, including both living and fossil forms, was as follows, the list forming the structure of the ''Règne Animal''. Where Cuvier's group names correspond (more or less) to modern taxa, these are named, in English if possible, in parentheses. The table from the 1828 '' Penny Cyclopaedia'' indicates species that were thought to belong to each group in Cuvier's taxonomy. The four major divisions were known as ''embranchements'' ("branches").

* I. Vertébrés. ( Vertebrates)

** Mammifères ( Mammals): 1. Bimanes, 2. Quadrumanes, 3. Carnassiers ( Carnivores), 4. Rongeurs (

Le Règne Animal Distribué d'après son Organisation, pour Servir de Base à l'Histoire Naturelle des Animaux et d'Introduction à l'Anatomie Comparée

'. Déterville libraire, Imprimerie de A. Belin, Paris, 4 Volumes, 1816.

Volume I

(introduction, mammals, birds)

Volume II

(reptiles, fish, molluscs, annelids)

Volume III

(crustaceans, arachnids, insects)

Volume IV

(zoophytes; tables, plates) {{DEFAULTSORT:Regne Animal 1816 non-fiction books Natural history books Zoology books

For the ''Règne Animal'', using evidence from comparative anatomy and

For the ''Règne Animal'', using evidence from comparative anatomy and palaeontology

Paleontology (), also spelled palaeontology or palæontology, is the scientific study of life that existed prior to, and sometimes including, the start of the Holocene epoch (roughly 11,700 years before present). It includes the study of fossi ...

—including his own observations—Cuvier divided the animal kingdom into four principal body plans. Taking the central nervous system as an animal's principal organ system which controlled all the other organ systems such as the circulatory and digestive systems, Cuvier distinguished four types of organisation of an animal's body:

* I. with a brain and a spinal cord (surrounded by parts of the skeleton)

* II. with organs linked by nerve fibres

* III. with two longitudinal, ventral nerve cords linked by a band with two ganglia positioned below the oesophagus

* IV. with a diffuse nervous system which is not clearly discernible

Grouping animals with these body plans resulted in four "embranchements" or branches (vertebrates, molluscs, the articulata that he claimed were natural (arguing that insects and annelid worms were related) and zoophytes ( radiata)). This effectively broke with the mediaeval notion of the continuity of the living world in the form of the great chain of being. It also set him in opposition to both Saint-Hilaire and Jean-Baptiste Lamarck. Lamarck claimed that species could transform through the influence of the environment, while Saint-Hilaire argued in 1820 that two of Cuvier's branches, the molluscs and radiata, could be united via various features, while the other two, articulata and vertebrates, similarly had parallels with each other. Then in 1830, Saint-Hilaire argued that these two groups could themselves be related, implying a single form of life from which all others could have evolved, and that Cuvier's four body plans were not fundamental.

Book

Editions

Jean Victor Audouin

Jean Victor Audouin (27 April 1797 – 9 November 1841), sometimes Victor Audouin, was a French naturalist, an entomologist, herpetologist, ornithologist, and malacologist.

Biography

Audouin was born in Paris and was educated in the field of medi ...

(insects), Gerard Paul Deshayes

Gerard is a masculine forename of Proto-Germanic origin, variations of which exist in many Germanic and Romance languages. Like many other early Germanic names, it is dithematic, consisting of two meaningful constituents put together. In this ca ...

(molluscs), Alcide d'Orbigny (birds), Antoine Louis Dugès

Antoine Louis Dugès (19 December 1797 – 1 May 1838) was a French obstetrician and naturalist born in Charleville-Mézières, Ardennes. He was the father of zoologist Alfredo Dugès (1826–1910), and a nephew to midwife Marie-Louise Lach ...

(arachnids), Georges Louis Duvernoy (reptiles), Charles Léopold Laurillard

Charles Léopold Laurillard (21 January 1783 – 1853) was a French zoologist and paleontologist. His father died when he was 13, but he was able continue his studies. In 1803 he moved to Paris, and the following year he met Frédéric Cuvie ...

(mammals in part), Henri Milne Edwards

Henri Milne-Edwards (23 October 1800 – 29 July 1885) was an eminent French zoologist.

Biography

Henri Milne-Edwards was the 27th child of William Edwards, an English planter and colonel of the militia in Jamaica and Elisabeth Vaux, a Frenchwo ...

(crustaceans, annelids, zoophytes, and mammals in part), Francois Desire Roulin (mammals in part), Achille Valenciennes

Achille Valenciennes (9 August 1794 – 13 April 1865) was a French zoologist.

Valenciennes was born in Paris, and studied under Georges Cuvier. His study of parasitic worms in humans made an important contribution to the study of parasitology. ...

(fishes), Louis Michel François Doyère (insects), Charles Émile Blanchard

Charles is a masculine given name predominantly found in English and French speaking countries. It is from the French form ''Charles'' of the Proto-Germanic name (in runic alphabet) or ''*karilaz'' (in Latin alphabet), whose meaning was ...

(insects, zoophytes) and Jean Louis Armand de Quatrefages de Bréau (annelids, arachnids etc.).

The work was illustrated with tables and plates (at the end of Volume IV) covering only some of the species mentioned. A much larger set of illustrations, said by Cuvier to be "as accurate as they were elegant" was published by the entomologist Félix Édouard Guérin-Méneville in his ''Iconographie du Règne Animal de G. Cuvier'', the nine volumes appearing between 1829 and 1844. The 448 quarto plates by Christophe Annedouche

Christophe Annedouche (28 June 1803 – 10 June 1866) was a French engraver from Paris. He is known for his natural history illustrations in works such as Georges Cuvier's '' Le Règne Animal''.

Biography

On March 29, 1832, Annedouche married ...

, Canu, Eugène Giraud, Lagesse, Lebrun, Vittore Pedretti, Plée and Smith illustrated some 6200 animals.

Translations

''Le Règne Animal'' was translated into languages including English, German and Italian. Many English translations and abridged versions were published and reprinted in the nineteenth century; records may be for the entire work or individual volumes, which were not necessarily dated, while old translations were often brought out in "new" editions by other publishers, making for a complex publication history. A translation by Edward Griffith (with assistance by Edward Pidgeon for some volumes and other specialists for other volumes) was published in 44 parts by G.B. Whittaker and partners from 1824 to 1835 and many times reprinted (up to 2012 and eBook format); another by G. Henderson in 1834–1837. A translation was made and published by the ornithologist William MacGillivray in Edinburgh in 1839–1840. Another version byEdward Blyth

Edward Blyth (23 December 1810 – 27 December 1873) was an English zoologist who worked for most of his life in India as a curator of zoology at the museum of the Asiatic Society of India in Calcutta.

Blyth was born in London in 1810. In 1841 ...

and others was published by William S. Orr and Co. in 1840. An abridged version by an "experienced teacher" was published by Longman, Brown, Green and Longman in London, and by Stephen Knapp in Coventry, in 1844. Kraus published an edition in New York in 1969. Other editions were brought out by H.G. Bohn in 1851 and W. Orr in 1854. An "easy introduction to the study of the animal kingdom: according to the natural method of Cuvier", together with examination questions on each chapter, was made by Annie Roberts and published in the 1850s by Thomas Varty.

A German translation by H.R. Schinz was published by J.S. Cotta in 1821–1825; another was made by Friedrich Siegmund Voigt and published by Brockhaus.

An Italian translation by G. de Cristofori was published by Stamperia Carmignani in 1832.

A Hungarian translation by Peter Vajda was brought out in 1841.

Approach

Each section, such as on reptiles at the start of Volume II (and the entire work) is introduced with an essay on distinguishing aspects of their zoology. In the case of the reptiles, the essay begins with the observation that their circulation is so arranged that only part of the blood pumped by the heart goes through the lungs; Cuvier discusses the implications of this arrangement, next observing that they have a relatively small brain compared to the mammals and birds, and that none of them incubate their eggs.

Next, Cuvier identifies the taxonomic divisions of the group, in this case four orders of reptiles, the chelonians ( tortoises and turtles), saurians (

Each section, such as on reptiles at the start of Volume II (and the entire work) is introduced with an essay on distinguishing aspects of their zoology. In the case of the reptiles, the essay begins with the observation that their circulation is so arranged that only part of the blood pumped by the heart goes through the lungs; Cuvier discusses the implications of this arrangement, next observing that they have a relatively small brain compared to the mammals and birds, and that none of them incubate their eggs.

Next, Cuvier identifies the taxonomic divisions of the group, in this case four orders of reptiles, the chelonians ( tortoises and turtles), saurians (lizards

Lizards are a widespread group of squamate reptiles, with over 7,000 species, ranging across all continents except Antarctica, as well as most oceanic island chains. The group is paraphyletic since it excludes the snakes and Amphisbaenia althou ...

), ophidians (snakes

Snakes are elongated, limbless, carnivorous reptiles of the suborder Serpentes . Like all other squamates, snakes are ectothermic, amniote vertebrates covered in overlapping scales. Many species of snakes have skulls with several more joi ...

) and batracians (amphibians

Amphibians are four-limbed and ectothermic vertebrates of the class Amphibia. All living amphibians belong to the group Lissamphibia. They inhabit a wide variety of habitats, with most species living within terrestrial, fossorial, arbore ...

, now considered a separate class of vertebrates), describing each group in a single sentence. Thus the batracians are said to have a heart with a single atrium, a naked body (with no scales), and to pass with age from being fish-like to being like a quadruped or biped.

There is then a section heading, in this case "The first order of Reptiles, or The Chelonians", followed by a three-page essay on their zoology, starting with the fact that their hearts have two atria. The structure then repeats at a lower taxonomic level, with what Cuvier notes is one of Linnaeus's genera, '' Testudo'', the tortoises, with five sub-genera. The first sub-genus comprises the land tortoises; their zoology is summed up in a paragraph, which observes that they have a domed carapace

A carapace is a Dorsum (biology), dorsal (upper) section of the exoskeleton or shell in a number of animal groups, including arthropods, such as crustaceans and arachnids, as well as vertebrates, such as turtles and tortoises. In turtles and tor ...

, with a solid bony support (the term being "charpente", commonly used of the structure of wooden beams that support a roof). He records that the legs are thick, with short digits joined for most of their length, five toenails on the forelegs, four on the hind legs.

Then (on the ninth page) he arrives at the first species in the volume, the Greek tortoise, ''Testudo graeca

The Greek tortoise (''Testudo graeca''), also known commonly as the spur-thighed tortoise, is a species of tortoise in the family Testudinidae. ''Testudo graeca'' is one of five species of Mediterranean tortoises (genera '' Testudo'' and '' Ag ...

''. It is summed up in a paragraph, Cuvier noting that it is the commonest tortoise in Europe, living in Greece, Italy, Sardinia and (he writes) apparently all round the Mediterranean. He then gives its distinguishing marks, with a highly domed carapace, raised scales boldly marked with black and yellow marbling, and at the posterior edge a bulge over the tail. He gives its size—rarely reaching a foot in length; notes that it lives on leaves, fruit, insects and worms; digs a hole in which to pass the winter; mates in spring, and lays 4 or 5 eggs like those of a pigeon. The species is illustrated with two plates.

Contents

The classification adopted by Cuvier to define the natural structure of the animal kingdom, including both living and fossil forms, was as follows, the list forming the structure of the ''Règne Animal''. Where Cuvier's group names correspond (more or less) to modern taxa, these are named, in English if possible, in parentheses. The table from the 1828 '' Penny Cyclopaedia'' indicates species that were thought to belong to each group in Cuvier's taxonomy. The four major divisions were known as ''embranchements'' ("branches").

* I. Vertébrés. ( Vertebrates)

** Mammifères ( Mammals): 1. Bimanes, 2. Quadrumanes, 3. Carnassiers ( Carnivores), 4. Rongeurs (

The classification adopted by Cuvier to define the natural structure of the animal kingdom, including both living and fossil forms, was as follows, the list forming the structure of the ''Règne Animal''. Where Cuvier's group names correspond (more or less) to modern taxa, these are named, in English if possible, in parentheses. The table from the 1828 '' Penny Cyclopaedia'' indicates species that were thought to belong to each group in Cuvier's taxonomy. The four major divisions were known as ''embranchements'' ("branches").

* I. Vertébrés. ( Vertebrates)

** Mammifères ( Mammals): 1. Bimanes, 2. Quadrumanes, 3. Carnassiers ( Carnivores), 4. Rongeurs (Rodents

Rodents (from Latin , 'to gnaw') are mammals of the order Rodentia (), which are characterized by a single pair of continuously growing incisors in each of the upper and lower jaws. About 40% of all mammal species are rodents. They are nat ...

), 5. Édentés ( Edentates), 6. Pachydermes ( Pachyderms), 7. Ruminants ( Ruminants), 8. Cétacés (Cetaceans

Cetacea (; , ) is an infraorder of aquatic mammals that includes whales, dolphins, and porpoises. Key characteristics are their fully aquatic lifestyle, streamlined body shape, often large size and exclusively carnivorous diet. They propel them ...

).

** Oiseaux (Birds

Birds are a group of warm-blooded vertebrates constituting the class Aves (), characterised by feathers, toothless beaked jaws, the laying of hard-shelled eggs, a high metabolic rate, a four-chambered heart, and a strong yet lightweigh ...

): 1. Oiseaux de proie ( Birds of prey), 2. Passereaux ( Passerines), 3. Grimpeurs ( Piciformes), 4. Gallinacés (Gallinaceous birds

Galliformes is an order of heavy-bodied ground-feeding birds that includes turkeys, chickens, quail, and other landfowl. Gallinaceous birds, as they are called, are important in their ecosystems as seed dispersers and predators, and are often ...

), 5. Échassiers ( Waders), 6. Palmipèdes (Anseriformes

Anseriformes is an order of birds also known as waterfowl that comprises about 180 living species of birds in three families: Anhimidae (three species of screamers), Anseranatidae (the magpie goose), and Anatidae, the largest family, which in ...

).

** Reptiles (Reptiles

Reptiles, as most commonly defined are the animals in the Class (biology), class Reptilia ( ), a paraphyletic grouping comprising all sauropsid, sauropsids except birds. Living reptiles comprise turtles, crocodilians, Squamata, squamates (lizar ...

, inc. Amphibians): 1. Chéloniens ( Chelonii), 2. Sauriens (Lizards

Lizards are a widespread group of squamate reptiles, with over 7,000 species, ranging across all continents except Antarctica, as well as most oceanic island chains. The group is paraphyletic since it excludes the snakes and Amphisbaenia althou ...

), 3. Ophidiens (Snakes

Snakes are elongated, limbless, carnivorous reptiles of the suborder Serpentes . Like all other squamates, snakes are ectothermic, amniote vertebrates covered in overlapping scales. Many species of snakes have skulls with several more joi ...

), 4. Batraciens (Amphibians

Amphibians are four-limbed and ectothermic vertebrates of the class Amphibia. All living amphibians belong to the group Lissamphibia. They inhabit a wide variety of habitats, with most species living within terrestrial, fossorial, arbore ...

).

** Poissons ( Fishes): 1. Chrondroptérygiens à branchies fixes ( Chondrichthyes), 2. Sturioniens ou Chrondroptérygiens à branchies libres (Sturgeon

Sturgeon is the common name for the 27 species of fish belonging to the family Acipenseridae. The earliest sturgeon fossils date to the Late Cretaceous

The Late Cretaceous (100.5–66 Ma) is the younger of two epochs into which the Cretace ...

s), 3. Plectognates ( Tetraodontiformes), 4. Lophobranches ( Syngnathidae), 5. Malacoptérygiens abdominaux, 6. Malacoptérygiens subbrachiens, 7. Malacoptérygiens apodes, 8. Acanthoptérygiens (Acanthopterygians

Acanthopterygii (meaning "spiny finned one") is a superorder of bony fishes in the class Actinopterygii. Members of this superorder are sometimes called ray-finned fishes for the characteristic sharp, bony rays in their fins; however this nam ...

).

* II. Mollusques. ( Molluscs)

** Céphalopodes. (Cephalopods

A cephalopod is any member of the molluscan class Cephalopoda (Greek plural , ; "head-feet") such as a squid, octopus, cuttlefish, or nautilus. These exclusively marine animals are characterized by bilateral body symmetry, a prominent head, an ...

)

** Ptéropodes. (Pteropods

Pteropoda (common name pteropods, from the Greek meaning "wing-foot") are specialized free-swimming pelagic sea snails and sea slugs, marine opisthobranch gastropods. Most live in the top 10 m of the ocean and are less than 1 cm long. The mon ...

)

** Gastéropodes ( Gastropods): 1. Nudibranches ( Nudibranchs), 2. Inférobranches, 3. Tectibranches, 4. Pulmonés (Pulmonata

Pulmonata or pulmonates, is an informal group (previously an order, and before that a subclass) of snails and slugs characterized by the ability to breathe air, by virtue of having a pallial lung instead of a gill, or gills. The group includ ...

), 5. Pectinibranches, 6. Scutibranches, 7. Cyclobranches.

** Acéphales (Bivalves

Bivalvia (), in previous centuries referred to as the Lamellibranchiata and Pelecypoda, is a class of marine and freshwater molluscs that have laterally compressed bodies enclosed by a shell consisting of two hinged parts. As a group, bival ...

etc.): 1. Testacés, 2. Sans coquilles.

** Brachiopodes. ( Brachiopods, now a separate phylum)

** Cirrhopodes. ( Barnacles, now in Crustacea)

* III. Articulés. (Articulated animals: now Arthropods

Arthropods (, (gen. ποδός)) are invertebrate animals with an exoskeleton, a Segmentation (biology), segmented body, and paired jointed appendages. Arthropods form the phylum Arthropoda. They are distinguished by their jointed limbs and Arth ...

and Annelids)

** Annélides ( Annelids): 1. Tubicoles, 2. Dorsibranches, 3. Abranches.

** Crustacés ( Crustaceans): 1. Décapodes ( Decapods), 2. Stomapodes ( Stomatopods), 3. Amphipodes ( Amphipods), 4. Isopodes ( Isopods), 5. Branchiopodes (Branchiopods

Branchiopoda is a class (biology), class of crustaceans. It comprises Anostraca, fairy shrimp, clam shrimp, Diplostraca (or Cladocera), Notostraca and the Devonian ''Lepidocaris''. They are mostly small, freshwater animals that feed on plankton ...

).

** Arachnides (Arachnids

Arachnida () is a Class (biology), class of joint-legged invertebrate animals (arthropods), in the subphylum Chelicerata. Arachnida includes, among others, spiders, scorpions, ticks, mites, pseudoscorpions, opiliones, harvestmen, Solifugae, came ...

): 1. Pulmonaires, 2. Trachéennes.

** Insectes ( Insects, inc. Myriapods): 1. Myriapodes, 2. Thysanoures ( Thysanura), 3. Parasites, 4. Suceurs, 5. Coléoptères (Coleoptera

Beetles are insects that form the order Coleoptera (), in the superorder Endopterygota. Their front pair of wings are hardened into wing-cases, elytra, distinguishing them from most other insects. The Coleoptera, with about 400,000 describ ...

), 6. Orthoptères (Orthoptera

Orthoptera () is an order of insects that comprises the grasshoppers, locusts, and crickets, including closely related insects, such as the bush crickets or katydids and wētā. The order is subdivided into two suborders: Caelifera – grassho ...

), 7. Hémiptères (Hemiptera

Hemiptera (; ) is an order (biology), order of insects, commonly called true bugs, comprising over 80,000 species within groups such as the cicadas, aphids, planthoppers, leafhoppers, Reduviidae, assassin bugs, Cimex, bed bugs, and shield bugs. ...

), 8. Névroptères (Neuroptera

The insect order Neuroptera, or net-winged insects, includes the lacewings, mantidflies, antlions, and their relatives. The order consists of some 6,000 species. Neuroptera can be grouped together with the Megaloptera and Raphidioptera in th ...

), 9. Hyménoptères (Hymenoptera

Hymenoptera is a large order (biology), order of insects, comprising the sawfly, sawflies, wasps, bees, and ants. Over 150,000 living species of Hymenoptera have been described, in addition to over 2,000 extinct ones. Many of the species are Par ...

), 10. Lépidoptères (Lepidoptera

Lepidoptera ( ) is an order (biology), order of insects that includes butterfly, butterflies and moths (both are called lepidopterans). About 180,000 species of the Lepidoptera are described, in 126 Family (biology), families and 46 Taxonomic r ...

), 11. Ripiptères ( Strepsiptera), 12. Diptères (Diptera

Flies are insects of the order Diptera, the name being derived from the Greek δι- ''di-'' "two", and πτερόν ''pteron'' "wing". Insects of this order use only a single pair of wings to fly, the hindwings having evolved into advanced ...

).

* IV. Zoophytes. ( Zoophytes, called Radiata in English translations; now Cnidaria and other phyla)

** Échinodermes (Echinoderms

An echinoderm () is any member of the phylum Echinodermata (). The adults are recognisable by their (usually five-point) radial symmetry, and include starfish, brittle stars, sea urchins, sand dollars, and sea cucumbers, as well as the sea li ...

): 1. Pédicellés, 2. Sans pieds.

** Intestinaux (Helminth

Parasitic worms, also known as helminths, are large macroparasites; adults can generally be seen with the naked eye. Many are intestinal worms that are soil-transmitted and infect the gastrointestinal tract. Other parasitic worms such as schi ...

s): 1. Cavitaires, 2. Parenchymateux.

** Acalèphes ( Jellyfish and other free-floating polyps): 1. Fixes, 2. Libres.

** Polypes (Cnidaria

Cnidaria () is a phylum under kingdom Animalia containing over 11,000 species of aquatic animals found both in Fresh water, freshwater and Marine habitats, marine environments, predominantly the latter.

Their distinguishing feature is cnidocyt ...

): 1. Nus, 2. À polypiers.

** Infusoires ( Infusoria, various protistan phyla): 1. Rotifères ( Rotifers), 2. Homogènes.

Reception

Contemporary

The entomologist William Sharp Macleay, in his 1821 book ''Horae Entomologicae'' which put forward the short-lived "Quinarian

The quinarian system was a method of zoological classification which was popular in the mid 19th century, especially among British naturalists. It was largely developed by the entomologist William Sharp Macleay in 1819. The system was further pr ...

" system of classification into 5 groups, each of 5 subgroups, etc., asserted that in the ''Règne Animal'' "Cuvier was notoriously deficient in the power of legitimate and intuitive generalization in arranging the animal series". The zoologist William John Swainson

William John Swainson FLS, FRS (8 October 1789 – 6 December 1855), was an English ornithologist, malacologist, conchologist, entomologist and artist.

Life

Swainson was born in Dover Place, St Mary Newington, London, the eldest son of ...

, also a Quinarian, added that "no person of such transcendent talents and ingenuity, ever made so little use of his observations towards a natural arrangement as M. Cuvier."

The '' Magazine of Natural History'' of 1829 expressed surprise at the long interval between the first and second editions, surmising that there were too few scientific readers in France, apart from those in Paris itself; it notes that while the first volume was little changed, the treatment of fish was considerably altered in volume II, while the section on the Articulata was greatly enlarged (to two volumes, IV and V) and written by M. Latreille. It also expressed the hope that there would be an English equivalent of Cuvier's work, given the popularity of natural history resulting from the works of Thomas Bewick ('' A History of British Birds'' 1797–1804) and George Montagu (''Ornithological Dictionary

The ''Ornithological Dictionary; or Alphabetical Synopsis of British Birds'' was written by the English naturalist and army officer George Montagu, and first published by J. White of Fleet Street, London in 1802.

It was one of the texts, al ...

'', 1802). The same review covers Félix Édouard Guérin-Méneville's ''Iconographie du Règne Animal de M. le Baron Cuvier'', which offered illustrations of all Cuvier's genera (except for the birds).

The ''Foreign Review'' of 1830 broadly admired Cuvier's work, but disagreed with his classification. It commented that "From the comprehensive nature of the ''Règne Animal'', embracing equally the structure and history of all the existing and extinct races of animals, this work may be viewed as an epitome of M. Cuvier's zoological labours; and it presents the best outline, which exists in any language, of the present state of zoology and comparative anatomy." The review continued less favourably, however, that "We cannot help thinking that the science of comparative anatomy is now so far advanced, as to afford the means of distributing the animal kingdom on some more uniform and philosophical principles,—as on the modifications of those systems or functions which are most general in the animal economy". The review argued that the vertebrate division relied on the presence of a vertebral column, "a part of the organization of comparatively little importance in the economy"; it found the basis of the mollusca on "the general softness of the body" no better; the choice of the presence of articulations no better either, in the third division; while in the fourth it points out that while the echinoderms may fit well into the chosen scheme, it did not apply "to the entozoa, zoophyta, and infusoria, which constitute by much the greatest portion of this division." But the review notes that "the general distribution of the animal kingdom established by M. Cuvier in this work, are founded on a more extensive and minute survey of the organization than had ever before been taken, and many of the most important distinctions among the orders and families are the result of his own researches."

Writing in the ''Monthly Review'' of 1834, the pre-Darwinian evolutionist surgeon Sir William Lawrence commented that "the ''Regne Animal'' of Cuvier is, in short, an abridged expression of the entire science. He carried the lights derived from his zoological researches into kindred but obscure parts of nature." Lawrence calls the work "an arrangement of the animal kingdom nearly approaching to perfection; grounded on principles so accurate, that the place which any animal occupies in this scheme, already indicates the leading circumstances in its structure, economy, and habits."

The book was in the library of '' HMS Beagle'' for Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English natural history#Before 1900, naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all speci ...

's voyage. In '' The Origin of Species'' (1859), in a chapter on the difficulties facing the theory, Darwin comments that "The expression of conditions of existence, so often insisted on by the illustrious Cuvier, is fully embraced by the principle of natural selection." Darwin continues, reflecting both on Cuvier's emphasis on the conditions of existence, and Jean-Baptiste Lamarck's theory of acquiring heritable characteristics from those Cuvieran conditions: "For natural selection acts by either now adapting the varying parts of each being to its organic and inorganic conditions of life; or by having adapted them during long-past periods of time: the adaptations being aided in some cases by use and disuse, being slightly affected by the direct action of the external conditions of life, and being in all cases subjected to the several laws of growth. Hence, in fact, the law of the Conditions of Existence is the higher law; as it includes, through the inheritance of former adaptations, that of Unity of Type."

Modern

The palaeontologist Philippe Taquet wrote that "the ''Règne Animal'' was an attempt to create a complete inventory of the animal kingdom and to formulate a natural classification underpinned by the principles of the 'correlation of parts'.." He adds that with the book "Cuvier introduced clarity into natural history, accurately reproducing the actual ordering of animals." Taquet further notes that while Cuvier rejected evolution, it was paradoxically "the precision of his anatomical descriptions and the importance of his research on fossil bones", showing for instance that mammoths were extinct elephants, that enabled later naturalists including Darwin to argue convincingly that animals had evolved.Notes

References

External links

* Cuvier, Georges; Latreille, Pierre André.Le Règne Animal Distribué d'après son Organisation, pour Servir de Base à l'Histoire Naturelle des Animaux et d'Introduction à l'Anatomie Comparée

'. Déterville libraire, Imprimerie de A. Belin, Paris, 4 Volumes, 1816.

Volume I

(introduction, mammals, birds)

Volume II

(reptiles, fish, molluscs, annelids)

Volume III

(crustaceans, arachnids, insects)

Volume IV

(zoophytes; tables, plates) {{DEFAULTSORT:Regne Animal 1816 non-fiction books Natural history books Zoology books