Lawrence Textile Strike on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Lawrence Textile Strike, also known as the Bread and Roses Strike, was a

Founded in 1845,

Founded in 1845,

By 1912, the Lawrence mills at maximum capacity employed about 32,000 men, women, and children. Conditions had worsened even more in the decade before the strike. The introduction of the two-loom system in the woolen mills led to a dramatic increase in the pace of work. The greater production enabled the factory owners to lay off large numbers of workers. Those who kept their jobs earned, on average, $8.76 for 56 hours of work and $9.00 for 60 hours of work. Some of the mills, worker housing and part of the town was owned by American Woolen Company president William Wood, who said he could not afford to pay his workers for the two hours per week they were cut, even though the company had made a profit of $3,000,000 in 1911.

The workers in Lawrence lived in crowded and dangerous apartment buildings, often with many families sharing each apartment. Many families survived on bread, molasses, and beans; as one worker testified before the March 1912 congressional investigation of the Lawrence strike, "When we eat meat it seems like a holiday, especially for the children." Half of children died before they were six, and 36% of the adults who worked in the mill died before they were 25. The average life expectancy was 39.

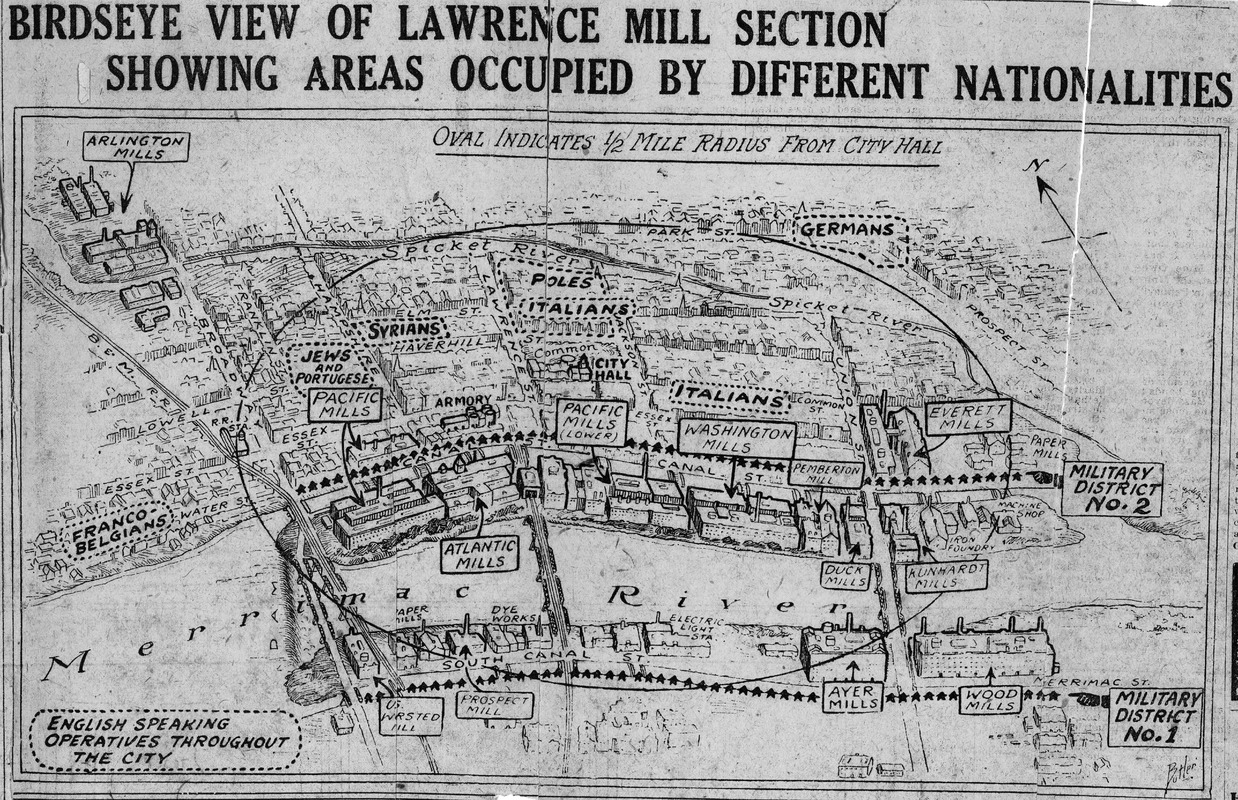

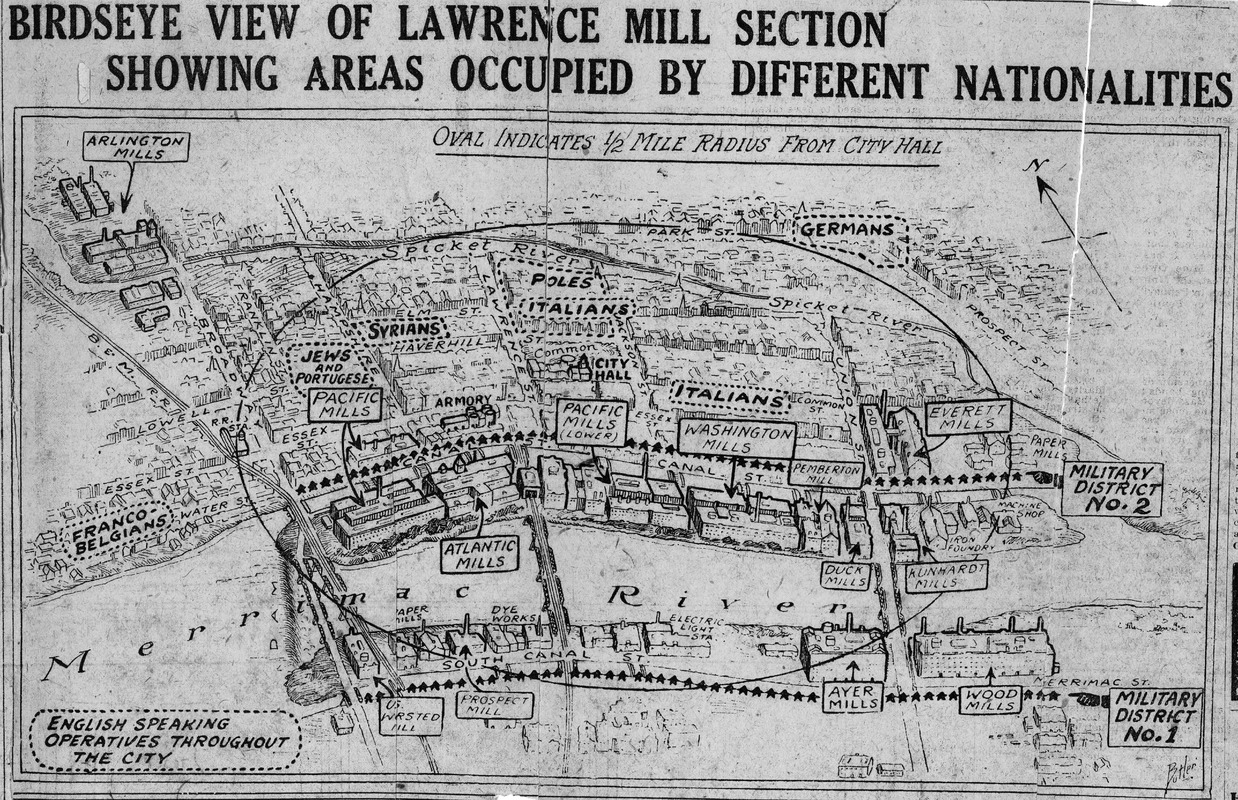

The mills and the community were divided along ethnic lines: most of the skilled jobs were held by native-born workers of English Americans, English,

Some of the mills, worker housing and part of the town was owned by American Woolen Company president William Wood, who said he could not afford to pay his workers for the two hours per week they were cut, even though the company had made a profit of $3,000,000 in 1911.

The workers in Lawrence lived in crowded and dangerous apartment buildings, often with many families sharing each apartment. Many families survived on bread, molasses, and beans; as one worker testified before the March 1912 congressional investigation of the Lawrence strike, "When we eat meat it seems like a holiday, especially for the children." Half of children died before they were six, and 36% of the adults who worked in the mill died before they were 25. The average life expectancy was 39.

The mills and the community were divided along ethnic lines: most of the skilled jobs were held by native-born workers of English Americans, English,

On January 1, 1912, a new labor law took effect in

On January 1, 1912, a new labor law took effect in  The city responded to the strike by ringing the city's alarm bell for the first time in its history; the mayor ordered a company of the local militia to patrol the streets. When mill owners turned fire hoses on the picketers gathered in front of the mills, (See photograph) they responded by throwing ice at the plants, breaking a number of windows. The court sentenced 24 workers to a year in jail for throwing ice; as the judge stated, "The only way we can teach them is to deal out the severest sentences." Governor

The city responded to the strike by ringing the city's alarm bell for the first time in its history; the mayor ordered a company of the local militia to patrol the streets. When mill owners turned fire hoses on the picketers gathered in front of the mills, (See photograph) they responded by throwing ice at the plants, breaking a number of windows. The court sentenced 24 workers to a year in jail for throwing ice; as the judge stated, "The only way we can teach them is to deal out the severest sentences." Governor  The IWW was successful, even with AFL-affiliated operatives, as it defended the grievances of all operatives from all the mills. Conversely, the AFL and the mill owners preferred to keep negotiations between separate mills and their own operatives. However, in a move that frustrated the UTW, Oliver Christian, the national secretary of the Loomfixers Association and an AFL affiliate itself, said he believed

The IWW was successful, even with AFL-affiliated operatives, as it defended the grievances of all operatives from all the mills. Conversely, the AFL and the mill owners preferred to keep negotiations between separate mills and their own operatives. However, in a move that frustrated the UTW, Oliver Christian, the national secretary of the Loomfixers Association and an AFL affiliate itself, said he believed  The IWW responded by sending

The IWW responded by sending  The police action against the mothers and children of Lawrence attracted the attention of the nation, in particular that of

The police action against the mothers and children of Lawrence attracted the attention of the nation, in particular that of

Ettor and Giovanniti, both members of IWW, remained in prison for months after the strike was over. Haywood threatened a general strike to demand their freedom, with the cry "Open the jail gates or we will close the mill gates." The IWW raised $60,000 for their defense and held demonstrations and mass meetings throughout the country in their support; the

Ettor and Giovanniti, both members of IWW, remained in prison for months after the strike was over. Haywood threatened a general strike to demand their freedom, with the cry "Open the jail gates or we will close the mill gates." The IWW raised $60,000 for their defense and held demonstrations and mass meetings throughout the country in their support; the  When the trial of Ettor and Giovannitti, as well as a third defendant, Giuseppe Caruso, accused of firing the shot that killed the picketer, began in September 1912 in Salem before Judge Joseph F. Quinn, the three defendants were kept in steel cages in the courtroom. All witnesses testified that Ettor and Giovannitti were miles away and that Caruso, the third defendant, was at home and eating supper at the time of the killing.

Ettor and Giovannitti both delivered closing statements at the end of the two-month trial. In Ettor's closing statement, he turned and faced the District Attorney:

When the trial of Ettor and Giovannitti, as well as a third defendant, Giuseppe Caruso, accused of firing the shot that killed the picketer, began in September 1912 in Salem before Judge Joseph F. Quinn, the three defendants were kept in steel cages in the courtroom. All witnesses testified that Ettor and Giovannitti were miles away and that Caruso, the third defendant, was at home and eating supper at the time of the killing.

Ettor and Giovannitti both delivered closing statements at the end of the two-month trial. In Ettor's closing statement, he turned and faced the District Attorney:

''A People's History of the United States''.

Revised Edition. New York: HarperCollins, 2005. * https://www.celebrategreece.com/links/2185-products/resources/8397-angelo-rocco-the-lawrence-labor-strike-of-1912

Bread and Roses Centennial 1912–2012

Extensive collection of background information, photos, primary documents, bibliographies, testimonies, events, and more.

Testimony of Camella Teoli before Congress

on

Resources for teaching about the Lawrence Strike in K-12 Classrooms

listed on th

Zinn Education Project website

{{Authority control Labor disputes led by the Industrial Workers of the World

strike

Strike may refer to:

People

*Strike (surname)

Physical confrontation or removal

*Strike (attack), attack with an inanimate object or a part of the human body intended to cause harm

*Airstrike, military strike by air forces on either a suspected ...

of immigrant

Immigration is the international movement of people to a destination country of which they are not natives or where they do not possess citizenship in order to settle as permanent residents or naturalized citizens. Commuters, tourists, and ...

workers in Lawrence

Lawrence may refer to:

Education Colleges and universities

* Lawrence Technological University, a university in Southfield, Michigan, United States

* Lawrence University, a liberal arts university in Appleton, Wisconsin, United States

Preparator ...

, Massachusetts

Massachusetts (Massachusett language, Massachusett: ''Muhsachuweesut assachusett writing systems, məhswatʃəwiːsət'' English: , ), officially the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, is the most populous U.S. state, state in the New England ...

, in 1912 led by the Industrial Workers of the World

The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), members of which are commonly termed "Wobblies", is an international labor union that was founded in Chicago in 1905. The origin of the nickname "Wobblies" is uncertain. IWW ideology combines genera ...

(IWW). Prompted by a two-hour pay cut corresponding to a new law shortening the workweek for women, the strike spread rapidly through the town, growing to more than twenty thousand workers and involving nearly every mill in Lawrence. On January 1, 1912, the Massachusetts government enforced a law that cut mill workers' hours in a single work week from 56 hours, to 54 hours. Ten days later, they found out that pay had been reduced along with the cut in hours.

The strike united workers from more than 51 different nationalities

Nationality is a legal identification of a person in international law, establishing the person as a subject, a ''national'', of a sovereign state. It affords the state jurisdiction over the person and affords the person the protection of the ...

many of whom knew little to no English. A large portion of the striking workers, including many of the leaders of the strike, were Italian immigrants

The Italian diaspora is the large-scale emigration of Italians from Italy.

There were two major Italian diasporas in Italian history. The first diaspora began around 1880, two decades after the Risorgimento, Unification of Italy, and ended in the ...

. Carried on throughout a brutally cold winter, the strike lasted more than two months, from January to March, defying the assumptions of conservative trade union

A trade union (labor union in American English), often simply referred to as a union, is an organization of workers intent on "maintaining or improving the conditions of their employment", ch. I such as attaining better wages and benefits ( ...

s within the American Federation of Labor

The American Federation of Labor (A.F. of L.) was a national federation of labor unions in the United States that continues today as the AFL-CIO. It was founded in Columbus, Ohio, in 1886 by an alliance of craft unions eager to provide mutu ...

(AFL) that immigrant, largely female and ethnically divided workers could not be organized. In late January, when a striker, Anna LoPizzo Anna LoPizzo was an Italian immigrant striker killed during the Lawrence Textile Strike (also known as the Bread and Roses Strike), considered one of the most significant struggles in U.S. labor history. Eugene Debs said of the strike, "The Victory ...

, was killed by police during a protest, IWW organizers Joseph Ettor

Joseph James "Smiling Joe" Ettor (1885–1948) was an Italian-American trade union organizer who, in the middle-1910s, was one of the leading public faces of the Industrial Workers of the World. Ettor is best remembered as a defendant in a contr ...

and Arturo Giovannitti

Arturo M. Giovannitti (; 1884–1959) was an Italian-American union leader, socialist political activist, and poet. He is best remembered as one of the principal organizers of the 1912 Lawrence textile strike and as a defendant in a celebrated tri ...

were framed and arrested on charges of being accessories to the murder.

IWW leaders Bill Haywood

William Dudley "Big Bill" Haywood (February 4, 1869 – May 18, 1928) was an American labor organizer and founding member and leader of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) and a member of the executive committee of the Socialist Party of A ...

and Elizabeth Gurley Flynn

Elizabeth Gurley Flynn (August 7, 1890 – September 5, 1964) was a labor leader, activist, and feminist who played a leading role in the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW). Flynn was a founding member of the American Civil Liberties Union ...

came to Lawrence to run the strike. Together they masterminded its signature move, sending hundreds of the strikers' hungry children to sympathetic families in New York, New Jersey, and Vermont. The move drew widespread sympathy, especially after police stopped a further exodus, leading to violence at the Lawrence train station. Congressional hearings followed, resulting in exposure of shocking conditions in the Lawrence mills and calls for investigation of the "wool trust." Mill owners soon decided to settle the strike, giving workers in Lawrence and throughout New England raises of up to 20 percent. Within a year, however, the IWW had largely collapsed in Lawrence.

The Lawrence strike is often referred to as the "Bread and Roses

"Bread and Roses" is a political slogan as well as the name of an associated poem and song. It originated from a speech given by American women's suffrage activist Helen Todd; a line in that speech about "bread for all, and roses too" inspired ...

" strike. It has also been called the "strike for three loaves". The phrase "bread and roses" actually preceded the strike, appearing in a poem by James Oppenheim published in ''The American Magazine

''The American Magazine'' was a periodical publication founded in June 1906, a continuation of failed publications purchased a few years earlier from publishing mogul Miriam Leslie. It succeeded ''Frank Leslie's Popular Monthly'' (1876–1904), ' ...

'' in December 1911. A 1915 labor anthology, ''The Cry for Justice: An Anthology of the Literature of Social Protest'' by Upton Sinclair

Upton Beall Sinclair Jr. (September 20, 1878 – November 25, 1968) was an American writer, muckraker, political activist and the 1934 Democratic Party nominee for governor of California who wrote nearly 100 books and other works in seve ...

, attributed the phrase to the Lawrence strike, and the association stuck.

A popular rallying cry from the poem that has interwoven with the memory of the strike:

As we come marching, marching, we battle too for men,

For they are women's children, and we mother them again.

Our lives shall not be sweated from birth until life closes;

Hearts starve as well as bodies; give us bread, but give us roses! —James Oppenheim James Oppenheim (24 May 1882 – 4 August 1932) was an American poet, novelist, and editor. A lay analyst and early follower of Carl Jung, Oppenheim was also a founder and editor of ''The Seven Arts''. Life and work Oppenheim was born in St. ...

Background

Founded in 1845,

Founded in 1845, Lawrence

Lawrence may refer to:

Education Colleges and universities

* Lawrence Technological University, a university in Southfield, Michigan, United States

* Lawrence University, a liberal arts university in Appleton, Wisconsin, United States

Preparator ...

was a flourishing but deeply-troubled textile city. By 1900, mechanization and the deskilling of labor in the textile industry enabled factory owners to eliminate skilled workers and to employ large numbers of unskilled immigrant workers, mostly women. Work in a textile mill

Textile Manufacturing or Textile Engineering is a major industry. It is largely based on the conversion of fibre into yarn, then yarn into fabric. These are then dyed or printed, fabricated into cloth which is then converted into useful goods ...

took place at a grueling pace, and the labor was repetitive and dangerous. About one third of workers in the Lawrence textile mills died before the age of 25. In addition, a number of children under 14 worked in the mills. Half of the workers in the four Lawrence mills of the American Woolen Company

The American Woolen Company is a designer, manufacturer and distributor of men’s and women’s worsted and woolen fabrics. Based in Stafford Springs, Connecticut, the company operates from the 160-year-old Warren Mills, which it acquired from Lo ...

, the leading employer in the industry and the town, were females between 14 and 18. Falsification of birth certificates, allowing for girls younger than 14 to work, was common practice at the time. Lawrence had the 5th highest child mortality rate of any city in the country at the time, behind four other mill towns in Massachusetts (Lowell, Fall River, Worcester, and HolyokeBy 1912, the Lawrence mills at maximum capacity employed about 32,000 men, women, and children. Conditions had worsened even more in the decade before the strike. The introduction of the two-loom system in the woolen mills led to a dramatic increase in the pace of work. The greater production enabled the factory owners to lay off large numbers of workers. Those who kept their jobs earned, on average, $8.76 for 56 hours of work and $9.00 for 60 hours of work.

Some of the mills, worker housing and part of the town was owned by American Woolen Company president William Wood, who said he could not afford to pay his workers for the two hours per week they were cut, even though the company had made a profit of $3,000,000 in 1911.

The workers in Lawrence lived in crowded and dangerous apartment buildings, often with many families sharing each apartment. Many families survived on bread, molasses, and beans; as one worker testified before the March 1912 congressional investigation of the Lawrence strike, "When we eat meat it seems like a holiday, especially for the children." Half of children died before they were six, and 36% of the adults who worked in the mill died before they were 25. The average life expectancy was 39.

The mills and the community were divided along ethnic lines: most of the skilled jobs were held by native-born workers of English Americans, English,

Some of the mills, worker housing and part of the town was owned by American Woolen Company president William Wood, who said he could not afford to pay his workers for the two hours per week they were cut, even though the company had made a profit of $3,000,000 in 1911.

The workers in Lawrence lived in crowded and dangerous apartment buildings, often with many families sharing each apartment. Many families survived on bread, molasses, and beans; as one worker testified before the March 1912 congressional investigation of the Lawrence strike, "When we eat meat it seems like a holiday, especially for the children." Half of children died before they were six, and 36% of the adults who worked in the mill died before they were 25. The average life expectancy was 39.

The mills and the community were divided along ethnic lines: most of the skilled jobs were held by native-born workers of English Americans, English, Irish

Irish may refer to:

Common meanings

* Someone or something of, from, or related to:

** Ireland, an island situated off the north-western coast of continental Europe

***Éire, Irish language name for the isle

** Northern Ireland, a constituent unit ...

, and German descent

, native_name_lang = de

, region1 =

, pop1 = 72,650,269

, region2 =

, pop2 = 534,000

, region3 =

, pop3 = 157,000

3,322,405

, region4 =

, pop4 = ...

, whereas French-Canadian

French Canadians (referred to as Canadiens mainly before the twentieth century; french: Canadiens français, ; feminine form: , ), or Franco-Canadians (french: Franco-Canadiens), refers to either an ethnic group who trace their ancestry to Fr ...

, Italian

Italian(s) may refer to:

* Anything of, from, or related to the people of Italy over the centuries

** Italians, an ethnic group or simply a citizen of the Italian Republic or Italian Kingdom

** Italian language, a Romance language

*** Regional Ita ...

, Slavic, Hungarian, Portuguese

Portuguese may refer to:

* anything of, from, or related to the country and nation of Portugal

** Portuguese cuisine, traditional foods

** Portuguese language, a Romance language

*** Portuguese dialects, variants of the Portuguese language

** Portu ...

, and Syrian immigrants made up most of the unskilled workforce. Several thousand skilled workers belonged, in theory at least, to the American Federation of Labor

The American Federation of Labor (A.F. of L.) was a national federation of labor unions in the United States that continues today as the AFL-CIO. It was founded in Columbus, Ohio, in 1886 by an alliance of craft unions eager to provide mutu ...

-affiliated United Textile Workers

The United Textile Workers of America (UTW) was a North American trade union established in 1901.

History

The United Textile Workers of America was founded following two conferences in 1901 under the aegis of the American Federation of Labor (AFL) ...

, but only a few hundred paid dues. The Industrial Workers of the World

The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), members of which are commonly termed "Wobblies", is an international labor union that was founded in Chicago in 1905. The origin of the nickname "Wobblies" is uncertain. IWW ideology combines genera ...

(IWW) had also been organizing for five years among workers in Lawrence but also had only a few hundred actual members.

Strike

On January 1, 1912, a new labor law took effect in

On January 1, 1912, a new labor law took effect in Massachusetts

Massachusetts (Massachusett language, Massachusett: ''Muhsachuweesut assachusett writing systems, məhswatʃəwiːsət'' English: , ), officially the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, is the most populous U.S. state, state in the New England ...

reducing the working week of 56 hours to 54 hours for women and children. Workers opposed the reduction if it reduced their weekly take-home pay. The first two weeks of 1912, the unions tried to learn how the owners of the mills would deal with the new law. On January 11, a group of Polish women textile workers in Lawrence discovered that their employer at the Everett Mill had reduced about $0.32 from their total wages and walked out.

On January 12, workers in the Washington Mill of the American Woolen Company also found that their wages had been cut. Prepared for the events by weeks of discussion, they walked out, calling "short pay, all out."

Joseph Ettor

Joseph James "Smiling Joe" Ettor (1885–1948) was an Italian-American trade union organizer who, in the middle-1910s, was one of the leading public faces of the Industrial Workers of the World. Ettor is best remembered as a defendant in a contr ...

of the IWW had been organizing in Lawrence for some time before the strike; he and Arturo Giovannitti

Arturo M. Giovannitti (; 1884–1959) was an Italian-American union leader, socialist political activist, and poet. He is best remembered as one of the principal organizers of the 1912 Lawrence textile strike and as a defendant in a celebrated tri ...

of the Italian Socialist Federation of the Socialist Party of America

The Socialist Party of America (SPA) was a socialist political party in the United States formed in 1901 by a merger between the three-year-old Social Democratic Party of America and disaffected elements of the Socialist Labor Party of Ameri ...

quickly assumed leadership of the strike by forming a strike committee of 56 people, four representatives of fourteen nationalities, which took responsibility for all major decisions. The committee, which arranged for its strike meetings to be translated into 25 different languages, put forward a set of demands: a 15% increase in wages for a 54-hour work week, double pay for overtime work, and no discrimination against workers for their strike activity.

The city responded to the strike by ringing the city's alarm bell for the first time in its history; the mayor ordered a company of the local militia to patrol the streets. When mill owners turned fire hoses on the picketers gathered in front of the mills, (See photograph) they responded by throwing ice at the plants, breaking a number of windows. The court sentenced 24 workers to a year in jail for throwing ice; as the judge stated, "The only way we can teach them is to deal out the severest sentences." Governor

The city responded to the strike by ringing the city's alarm bell for the first time in its history; the mayor ordered a company of the local militia to patrol the streets. When mill owners turned fire hoses on the picketers gathered in front of the mills, (See photograph) they responded by throwing ice at the plants, breaking a number of windows. The court sentenced 24 workers to a year in jail for throwing ice; as the judge stated, "The only way we can teach them is to deal out the severest sentences." Governor Eugene Foss

Eugene Noble Foss (September 24, 1858 – September 13, 1939) was an American politician and manufacturer from Massachusetts. He was a member of the United States House of Representatives and served as a three-term governor of Massachusetts.

E ...

then ordered out the state militia and state police. Mass arrests followed.

At the same time, the United Textile Workers (UTW) attempted to break the strike by claiming to speak for the workers of Lawrence. The striking operatives ignored the UTW, as the IWW had successfully united the operatives behind ethnic-based leaders, who were members of the strike committee and able to communicate Ettor's message to avoid violence at demonstrations. Ettor did not consider intimidating operatives who were trying to enter the mills as breaking the peace.

The IWW was successful, even with AFL-affiliated operatives, as it defended the grievances of all operatives from all the mills. Conversely, the AFL and the mill owners preferred to keep negotiations between separate mills and their own operatives. However, in a move that frustrated the UTW, Oliver Christian, the national secretary of the Loomfixers Association and an AFL affiliate itself, said he believed

The IWW was successful, even with AFL-affiliated operatives, as it defended the grievances of all operatives from all the mills. Conversely, the AFL and the mill owners preferred to keep negotiations between separate mills and their own operatives. However, in a move that frustrated the UTW, Oliver Christian, the national secretary of the Loomfixers Association and an AFL affiliate itself, said he believed John Golden

John Lionel Golden (June 27, 1874 – June 17, 1955) was an American actor, songwriter, author, and theatrical producer. As a songwriter, he is best-known as lyricist for "Poor Butterfly" (1916). He produced many Broadway shows and four films.

...

, the Massachusetts-based UTW president, was a detriment to the cause of labor. That statement and missteps by William Madison Wood

William Madison Wood (June 18, 1858 – February 2, 1926) was an American textile mill owner of Lawrence, Massachusetts who was considered to be an expert in efficiency. He made a good deal of his fortune through being hired by mill owners to tu ...

quickly shifted public sentiment to favor the strikers.

A local undertaker and a member of the Lawrence school board attempted to frame the strike leadership by planting dynamite in several locations in town a week after the strike began. He was fined $500 and released without jail time. Later, William M. Wood, the president of the American Woolen Company

The American Woolen Company is a designer, manufacturer and distributor of men’s and women’s worsted and woolen fabrics. Based in Stafford Springs, Connecticut, the company operates from the 160-year-old Warren Mills, which it acquired from Lo ...

, was shown to have made an unexplained large payment to the defendant shortly before the dynamite was found.

The authorities later charged Ettor and Giovannitti as accomplices to murder for the death of striker Anna LoPizzo Anna LoPizzo was an Italian immigrant striker killed during the Lawrence Textile Strike (also known as the Bread and Roses Strike), considered one of the most significant struggles in U.S. labor history. Eugene Debs said of the strike, "The Victory ...

, who was likely shot by the police. Ettor and Giovannitti had been away, where they spoke to another group of workers. They and a third defendant, who had not even heard of either Ettor or Giovannitti at the time of his arrest, were held in jail for the duration of the strike and several months thereafter. The authorities declared martial law, banned all public meetings, and called out 22 more militia companies to patrol the streets. Harvard students were even given exemptions from their final exams if they agreed to go and try to break up the strike.

The IWW responded by sending

The IWW responded by sending Bill Haywood

William Dudley "Big Bill" Haywood (February 4, 1869 – May 18, 1928) was an American labor organizer and founding member and leader of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) and a member of the executive committee of the Socialist Party of A ...

, Elizabeth Gurley Flynn

Elizabeth Gurley Flynn (August 7, 1890 – September 5, 1964) was a labor leader, activist, and feminist who played a leading role in the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW). Flynn was a founding member of the American Civil Liberties Union ...

, and a number of other organizers to Lawrence. Haywood participated little in the daily affairs of the strike. Instead, he set out for other New England textile towns in an effort to raise funds for the strikers in Lawrence, which proved very successful. Other tactics established were an efficient system of relief committees, soup kitchens, and food distribution stations, and volunteer doctors provided medical care. The IWW raised funds on a nationwide basis to provide weekly benefits for strikers and dramatized the strikers' needs by arranging for several hundred children to go to supporters' homes in New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

for the duration of the strike. When city authorities tried to prevent another 100 children from going to Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Sinc ...

on February 24 by sending police and the militia to the station to detain the children and arrest their parents, the police began clubbing both the children and their mothers and dragged them off to be taken away by truck; one pregnant mother miscarried. The press, there to photograph the event, reported extensively on the attack. Moreover, when the women and children were taken to the Police Court, most of them refused to pay the fines levied and opted for a jail cell, some with babies in arms.

The police action against the mothers and children of Lawrence attracted the attention of the nation, in particular that of

The police action against the mothers and children of Lawrence attracted the attention of the nation, in particular that of first lady

First lady is an unofficial title usually used for the wife, and occasionally used for the daughter or other female relative, of a non-monarchical

A monarchy is a form of government in which a person, the monarch, is head of state fo ...

Helen Herron Taft

Helen Louise Taft (née Herron; June 2, 1861 – May 22, 1943), known as Nellie, was the wife of President William Howard Taft and the first lady of the United States from 1909 to 1913.

Born to a politically well-connected Ohio family, Nel ...

, wife of President William Howard Taft

William Howard Taft (September 15, 1857March 8, 1930) was the 27th president of the United States (1909–1913) and the tenth chief justice of the United States (1921–1930), the only person to have held both offices. Taft was elected pr ...

. Soon, both the House and the Senate set out to investigate the strike. In the early days of March, a special House Committee heard testimony from some of the strikers' children, as well as various city, state and union officials. In the end, both chambers published reports detailing the conditions at Lawrence.

The children involved in the police riot were not only the children of striking workers, they were also striking workers themselves. Most of the workers at the mill were women and children. Families were suffering not only from the lost income of adult workers, but also the lost wages of children.

Children were used several times during the strike to attract attention to the cause. On February 10, 119 children were sent to Manhattan to live with relatives, or strangers, who were able to feed them to alleviate the financial strain on the striking families. The children were welcomed in NY by cheering crowds that drew national attention. When another group of children were sent to NY, they were paraded down 5th Avenue, drawing even more attention. Embarrassed by the bad publicity, the city marshal tried to deter the next group of children that were being sent to Philadelphia on February 24, with disastrous results. Police attempted to stop the children from boarding the train and as mothers tried to force their children on board, police intervened with clubs and arrested the mothers as their children watched. The next role that children played in the result of the strike was the testimony they gave about the working conditions in the factories. The national sympathy that children elicited changed the outcome of the strike.

Children of the mill workers were brought to homes of supporters of the Lawrence textile strike. With the aid of Haywood and Flynn, these two individuals organized a way for donations for the children of strikers. In addition, the children began to form strike rallies to demonstrate the hardship and struggle occurring in the Lawrence mill factories. Strikes happened from Vermont all the way to New York City; those children fought to be seen and heard where they went.

The national attention had an effect: the owners offered a 5% pay raise on March 1, but the workers rejected it. American Woolen Company agreed to most of the strikers' demands on March 12, 1912. The strikers had demanded an end to the Premium System in which a portion of their earnings were subject to month-long production and attendance standards. The mill owners' concession was to change the award of the premium from once every four weeks to once every two weeks. The rest of the manufacturers followed by the end of the month; other textile companies throughout New England

New England is a region comprising six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York to the west and by the Canadian provinces ...

, anxious to avoid a similar confrontation, then followed suit.

The children who had been taken in by supporters in New York City came home on March 30.

Aftermath

Ettor and Giovanniti, both members of IWW, remained in prison for months after the strike was over. Haywood threatened a general strike to demand their freedom, with the cry "Open the jail gates or we will close the mill gates." The IWW raised $60,000 for their defense and held demonstrations and mass meetings throughout the country in their support; the

Ettor and Giovanniti, both members of IWW, remained in prison for months after the strike was over. Haywood threatened a general strike to demand their freedom, with the cry "Open the jail gates or we will close the mill gates." The IWW raised $60,000 for their defense and held demonstrations and mass meetings throughout the country in their support; the Boston

Boston (), officially the City of Boston, is the state capital and most populous city of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as well as the cultural and financial center of the New England region of the United States. It is the 24th- mo ...

authorities arrested all of the members of the Ettor and Giovannitti Defense Committee. On March 10, 1912, an estimated 10,000 protestors gathered in Lawrence demanding the release of Ettor and Giovannitti. Then, 15,000 Lawrence workers went on strike for one day on September 30 to demand the release of Ettor and Giovannitti. Swedish and French workers proposed a boycott of woolen goods from the US and a refusal to load ships going there, and Italian supporters of the Giovannitti men rallied in front of the US consulate in Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus (legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

.

In the meantime, Ernest Pitman—l, a Lawrence building contractor who had done extensive work for the American Woolen Company, confessed to a district attorney that he had attended a meeting in the Boston offices of Lawrence textile companies, where the plan to frame the union by planting dynamite had been made. Pitman committed suicide shortly thereafter when he was subpoenaed to testify. Wood, the American Woolen Company owner, was formally exonerated.

When the trial of Ettor and Giovannitti, as well as a third defendant, Giuseppe Caruso, accused of firing the shot that killed the picketer, began in September 1912 in Salem before Judge Joseph F. Quinn, the three defendants were kept in steel cages in the courtroom. All witnesses testified that Ettor and Giovannitti were miles away and that Caruso, the third defendant, was at home and eating supper at the time of the killing.

Ettor and Giovannitti both delivered closing statements at the end of the two-month trial. In Ettor's closing statement, he turned and faced the District Attorney:

When the trial of Ettor and Giovannitti, as well as a third defendant, Giuseppe Caruso, accused of firing the shot that killed the picketer, began in September 1912 in Salem before Judge Joseph F. Quinn, the three defendants were kept in steel cages in the courtroom. All witnesses testified that Ettor and Giovannitti were miles away and that Caruso, the third defendant, was at home and eating supper at the time of the killing.

Ettor and Giovannitti both delivered closing statements at the end of the two-month trial. In Ettor's closing statement, he turned and faced the District Attorney:

Does Mr. Ateill believe for a moment that... the cross or the gallows or the guillotine, the hangman's noose, ever settled an idea? It never did. If an idea can live, it lives because history adjudges it right. And what has been considered an idea constituting a social crime in one age has in the next age become the religion of humanity. Whatever my social views are, they are what they are. They cannot be tried in this courtroom.All three defendants were acquitted on November 26, 1912. The strikers, however, lost nearly all of the gains they had won in the next few years. The IWW, disdaining written contracts as encouraging workers to abandon the daily class struggle, thus left the mill owners to chisel away at the improvements in wages and working conditions, to fire union activists, and to install

labor spies

Labor spying in the United States had involved people recruited or employed for the purpose of gathering intelligence, committing sabotage, sowing dissent, or engaging in other similar activities, in the context of an employer/labor organization r ...

to keep an eye on workers. The more persistent owners laid off further employees during a depression in the industry.

By then, the IWW had turned its attention to supporting the silk industry workers in Paterson, New Jersey

Paterson ( ) is the largest City (New Jersey), city in and the county seat of Passaic County, New Jersey, Passaic County, in the U.S. state of New Jersey.Paterson Silk Strike of 1913

The 1913 Paterson silk strike was a work stoppage involving silk mill workers in Paterson, New Jersey. The strike involved demands for establishment of an eight-hour day and improved working conditions. The strike began in February 1913, and end ...

was defeated.

Casualties

The strike had at least three casualties: *Anna LoPizzo Anna LoPizzo was an Italian immigrant striker killed during the Lawrence Textile Strike (also known as the Bread and Roses Strike), considered one of the most significant struggles in U.S. labor history. Eugene Debs said of the strike, "The Victory ...

, an Italian immigrant, who was shot in the chest during a clash between strikers and police

* John Ramey, a Syrian youth who was bayoneted in the back by the militia

* Jonas Smolskas, a Lithuanian immigrant who was beaten to death several months after the strike ended for wearing a pro-labor pin on his lapel

Conclusion and legacy

After the strike concluded, workers received a few of the demands established between mill workers and owners. Some workers went back to work at the mills and "others came and went, trying to find other jobs, failing, returning again to the music of the power loom". Even after the strike was finished, there were many other strikes that occurred in other states involving various mill factories. "On January 12, 1913, the IWW held anniversary celebration in Lawrence" which was one of the last celebrations for a couple of years. The 1912 strike was the first of many that by the mid-1900s would result in driving out the textile industry from New England. On February 9, 2019, SenatorElizabeth Warren

Elizabeth Ann Warren ( née Herring; born June 22, 1949) is an American politician and former law professor who is the senior United States senator from Massachusetts, serving since 2013. A member of the Democratic Party and regarded as a ...

officially announced her candidacy for President of the United States at the site of the strike.

See also

*Bread and Roses Heritage Festival

The Bread and Roses Heritage Festival is an annual, open-air festival in Lawrence, Massachusetts that celebrates labor history, cultural diversity, and social justice. It is a free, day-long event featuring live music and dance, children’s act ...

in Lawrence

*Carmela Teoli

Carmela Teoli (1897–) was an Italian-American mill worker whose testimony before the U.S. Congress in 1912 called national attention to unsafe working conditions in the mills and helped bring a successful end to the "Bread and Roses" strike. Teo ...

, a teenage mill worker who testified before Congress about being scalped by a machine

* William M. Wood, co-founder of the American Woolen Company

The American Woolen Company is a designer, manufacturer and distributor of men’s and women’s worsted and woolen fabrics. Based in Stafford Springs, Connecticut, the company operates from the 160-year-old Warren Mills, which it acquired from Lo ...

*Ralph Fasanella

Ralph Fasanella (September 2, 1914 – December 16, 1997) was an American self-taught painter whose large, detailed works depicted urban working life and critiqued post-World War II America.

Early life

Ralph Fasanella was born to Joseph and Ginev ...

, an artist who depicted the strike in a series of paintings

*Murder of workers in labor disputes in the United States

The following list of worker deaths in United States labor disputes captures known incidents of fatal labor-related violence in U.S. labor history, which began in the colonial era with the earliest worker demands around 1636 for better working co ...

References

Sources

* Cameron, Ardis, ''Radicals of the Worst Sort: Laboring Women in Lawrence, Massachusetts, 1860–1912'' (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1993). * Cole, Donald B. ''Immigrant City: Lawrence, Massachusetts 1845–1921.'' Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1963. * Forrant, Robert and Susan Grabski, ''Lawrence and the 1912 Bread and Roses Strike (Images of America)'' Arcadia Publishing, 2013. * Forrant, Robert and Jurg Siegenthaler, "The Great Lawrence Textile Strike of 1912: New Scholarship on the Bread & Roses Strike,"Amityville, NY: Baywood Publishing Inc., 2014. *Watson, Bruce, ''Bread and Roses: Mills, Migrants, and the Struggle for the American Dream'', Penguin Books, 2006. *Zinn, Howard

Howard Zinn (August 24, 1922January 27, 2010) was an American historian, playwright, philosopher, socialist thinker and World War II veteran. He was chair of the history and social sciences department at Spelman College, and a political scien ...

''A People's History of the United States''.

Revised Edition. New York: HarperCollins, 2005. * https://www.celebrategreece.com/links/2185-products/resources/8397-angelo-rocco-the-lawrence-labor-strike-of-1912

External links

Bread and Roses Centennial 1912–2012

Extensive collection of background information, photos, primary documents, bibliographies, testimonies, events, and more.

Testimony of Camella Teoli before Congress

on

Marxists.org

Marxists Internet Archive (also known as MIA or Marxists.org) is a non-profit online encyclopedia that hosts a multilingual library (created in 1990) of the works of communist, anarchist, and socialist writers, such as Karl Marx, Friedrich Enge ...

Resources for teaching about the Lawrence Strike in K-12 Classrooms

listed on th

Zinn Education Project website

{{Authority control Labor disputes led by the Industrial Workers of the World

Lawrence Textile Strike

The Lawrence Textile Strike, also known as the Bread and Roses Strike, was a strike of immigrant workers in Lawrence, Massachusetts, in 1912 led by the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW). Prompted by a two-hour pay cut corresponding to a ne ...

Textile and clothing labor disputes in the United States

Lawrence, Massachusetts

History of Essex County, Massachusetts

Riots and civil disorder in Massachusetts

Lawrence Textile Strike

The Lawrence Textile Strike, also known as the Bread and Roses Strike, was a strike of immigrant workers in Lawrence, Massachusetts, in 1912 led by the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW). Prompted by a two-hour pay cut corresponding to a ne ...

Industrial Revolution

Italian-American history

American Woolen Company

Progressive Era in the United States

Labor disputes in Massachusetts