Types of accent

The ancient Greek grammarians indicated the word-accent with three diacritic signs: the acute (ά), the circumflex (ᾶ), and the grave (ὰ). The acute was the most commonly used of these; it could be found on any of the last three syllables of a word. Some examples are: * 'man, person' * 'citizen' * 'good' The circumflex, which represented a falling tone, is found only on long vowels and diphthongs, and only on the last two syllables of the word: * 'body' * 'earth' When a circumflex appears on the final syllable of a polysyllabic word, it usually represents a contracted vowel: * 'I do' (contracted form of ) The grave is found, as an alternative to an acute, only on the last syllable of a word. When a word such as 'good' with final accent is followed by a pause (that is, whenever it comes at the end of a clause, sentence, or line of verse), or by anTerminology

In all there are exactly five different possibilities for placing an accent. The terms used by the ancient Greek grammarians were: *Oxytone (): acute on the final syllable (e.g. 'father') *Paroxytone (): acute on the penultimate (e.g. 'mother') *Proparoxytone (): acute on the antepenultimate (e.g. 'person') *Perispomenon (): circumflex on the final (e.g. 'I see') *Properispomenon (): circumflex on the penultimate (e.g. 'body') The wordPlacing the accent marks

In Greek, if an accent mark is written on a diphthong or vowel written with a digraph such as , it is always written above the second vowel of the diphthong, not the first, for example: * 'for the sailors' * 'one' When a word such as a proper name starts with a capital vowel letter, the accent and breathing are usually written before the letter. If a name starts with a diphthong, the accent is written above the second letter. But in 'Hades', where the diphthong is the equivalent of an alpha with iota subscript (i.e. ), it is written in front: * 'Hera' * 'Ajax' * 'Hades' When combined with a rough or smoothTonal minimal pairs

Whether the accent on a particular syllable is an acute or circumflex is largely predictable, but there are a few examples where a change from an acute on a long vowel to a circumflex indicates a different meaning, for example * 'he might free' – 'to free' * 'at home' – 'houses' * 'man' (poetic) – 'light' There are also examples where the meaning changes if the accent moves to a different syllable: * 'I remain' – 'I will remain' * 'I persuade' – 'persuasion' * 'make!' (middle imperative) – 'he might make' – 'to make' * 'ten thousand' – 'countless' * 'law' – 'place of pasturage' * 'Athenaeus' (proper name) – 'Athenian' There is also a distinction between unaccented (or grave-accented) and fully accented forms in words such as: * 'someone' – 'who?' * 'somewhere' / 'I suppose' – 'where?' * 'or' / 'than' – 'in truth' / 'I was' / 'he said' * 'but' – 'others (neuter)' * 'it is' – 'there is' / 'it exists' / 'it is possible'History of the accent in Greek writing

The three marks used to indicate accent in ancient Greek, the acute (´), circumflex (῀), and grave (`) are said to have been invented by the scholarOrigin of the accent

The ancient Greek accent, at least in nouns, appears to have been inherited to a large extent from the original parent language from which Greek and many other European and Indian languages derive,Pronunciation of the accent

General evidence

It is generally agreed that the ancient Greek accent was primarily one of pitch or melody rather than of stress. Thus in a word like 'man', the first syllable was pronounced on a higher pitch than the others, but not necessarily any louder. As long ago as the 19th century it was surmised that in a word with recessive accent the pitch may have fallen not suddenly but gradually in a sequence high–middle–low, with the final element always short. The evidence for this comes from various sources. The first is the statements of Greek grammarians, who consistently describe the accent in musical terms, using words such as 'high-pitched' and 'low-pitched'. According toEvidence from music

An important indication of the melodic nature of the Greek accent comes from the surviving pieces of Greek music, especially the two (Further examples of ancient Greek music can be found in the articles

(Further examples of ancient Greek music can be found in the articles Acute accent

When the signs for the notes in Greek music are transcribed into modern musical notation, it can be seen that an acute accent is generally followed by a fall, sometimes extending over two syllables. Usually the fall is only a slight one, as in 'daughters', 'Olympus' or 'she gave birth to' below. Sometimes, however, there is a sharp drop, as in 'you may sing' or 'windless': Before the accent the rise on average is less than the fall afterwards. There is sometimes a jump up from a lower note, as in the word 'mingling' from the second hymn; more often there is a gradual rise, as in 'of Castalia', 'Cynthian', or 'spreads upwards':

Before the accent the rise on average is less than the fall afterwards. There is sometimes a jump up from a lower note, as in the word 'mingling' from the second hymn; more often there is a gradual rise, as in 'of Castalia', 'Cynthian', or 'spreads upwards':

In some cases, however, before the accent instead of a rise there is a 'plateau' of one or two notes the same height as the accent itself, as in 'of Parnassus', 'he visits', 'of the Romans', or 'ageless' from the Delphic hymns:

In some cases, however, before the accent instead of a rise there is a 'plateau' of one or two notes the same height as the accent itself, as in 'of Parnassus', 'he visits', 'of the Romans', or 'ageless' from the Delphic hymns:

Anticipation of the high tone of an accent in this way is found in other

Anticipation of the high tone of an accent in this way is found in other  More frequently, however, on an accented long vowel in the music there is no rise in pitch, and the syllable is set to a level note, as in the words 'Hephaestus' from the 1st Delphic hymn or 'those' or 'of the Romans' from the 2nd hymn:

More frequently, however, on an accented long vowel in the music there is no rise in pitch, and the syllable is set to a level note, as in the words 'Hephaestus' from the 1st Delphic hymn or 'those' or 'of the Romans' from the 2nd hymn:

Because this is so common, it is possible that at least sometimes the pitch did not rise on a long vowel with an acute accent but remained level. Another consideration is that although the ancient grammarians regularly describe the circumflex accent as 'two-toned' () or 'compound' () or 'double' (), they usually do not make similar remarks about the acute. There are apparently some, however, who mention a 'reversed circumflex', presumably referring to this rising accent.

Because this is so common, it is possible that at least sometimes the pitch did not rise on a long vowel with an acute accent but remained level. Another consideration is that although the ancient grammarians regularly describe the circumflex accent as 'two-toned' () or 'compound' () or 'double' (), they usually do not make similar remarks about the acute. There are apparently some, however, who mention a 'reversed circumflex', presumably referring to this rising accent.

Tonal assimilation

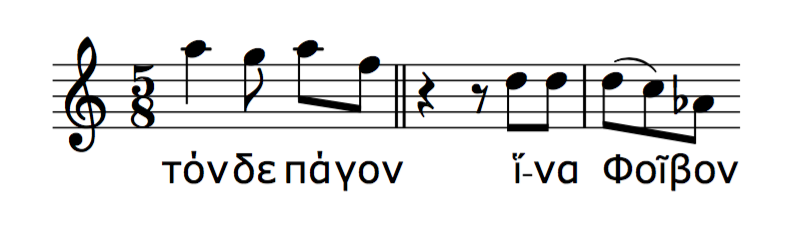

Devine and Stephens note that occasionally at the end of a word, the pitch rises again, as though leading up to or anticipating the accent in the following word. They refer to this as a 'secondary rise'. Examples are 'you have a tripod' or 'sing the Pythian' in the 2nd Delphic hymn. According to Devine and Stephens, it 'probably reflects a genuine process of pitch assimilation in fluent speech'. In the great majority of cases in the music, the pitch falls on the syllable immediately following an acute accent. However, there are some exceptions. One situation where this can happen is when two words are joined in a plateau or near-plateau, as in the phrases 'so that Phoebus' (1st Hymn) and 'in the city of Cecrops' in the 2nd Delphic Hymn:

In the great majority of cases in the music, the pitch falls on the syllable immediately following an acute accent. However, there are some exceptions. One situation where this can happen is when two words are joined in a plateau or near-plateau, as in the phrases 'so that Phoebus' (1st Hymn) and 'in the city of Cecrops' in the 2nd Delphic Hymn:

Tonal assimilation or

Tonal assimilation or Circumflex accent

A circumflex was written only over a long vowel or diphthong. In the music, the circumflex is usually set to a The circumflex therefore appears to have been pronounced in exactly the same way as an acute, except that the fall usually took place within one syllable. This is clear from the description of Dionysius of Halicarnassus (see above), who tells us that a circumflex accent was a blend of high and low pitch in a single syllable, and it is reflected in the word 'high-low' (or 'acute-grave'), which is one of the names given to the circumflex in ancient times. Another description was 'two-toned'.

Another piece of evidence for the pronunciation of the circumflex accent is the fact that when two vowels are contracted into one, if the first one has an acute, the result is a circumflex: e.g. 'I see' is contracted to with a circumflex, combining the high and low pitches of the previous vowels.

In the majority of examples in the Delphic hymns, the circumflex is set to a melisma of two notes. However, in Mesomedes' hymns, especially the hymn to Nemesis, it is more common for the circumflex to be set to a single note. Devine and Stephens see in this the gradual loss over time of the distinction between acute and circumflex.

One place where a circumflex can be a single note is in phrases where a noun is joined with a genitive or an adjective. Examples are (1st Delphic Hymn) 'thighs of bulls', 'Leto's son' (Mesomedes' Prayer to Calliope and Apollo), 'the whole world' (Mesomedes' Hymn to the Sun). In these phrases, the accent of the second word is higher than or on the same level as that of the first word, and just as with phrases such as mentioned above, the lack of fall in pitch appears to represent some sort of assimilation or

The circumflex therefore appears to have been pronounced in exactly the same way as an acute, except that the fall usually took place within one syllable. This is clear from the description of Dionysius of Halicarnassus (see above), who tells us that a circumflex accent was a blend of high and low pitch in a single syllable, and it is reflected in the word 'high-low' (or 'acute-grave'), which is one of the names given to the circumflex in ancient times. Another description was 'two-toned'.

Another piece of evidence for the pronunciation of the circumflex accent is the fact that when two vowels are contracted into one, if the first one has an acute, the result is a circumflex: e.g. 'I see' is contracted to with a circumflex, combining the high and low pitches of the previous vowels.

In the majority of examples in the Delphic hymns, the circumflex is set to a melisma of two notes. However, in Mesomedes' hymns, especially the hymn to Nemesis, it is more common for the circumflex to be set to a single note. Devine and Stephens see in this the gradual loss over time of the distinction between acute and circumflex.

One place where a circumflex can be a single note is in phrases where a noun is joined with a genitive or an adjective. Examples are (1st Delphic Hymn) 'thighs of bulls', 'Leto's son' (Mesomedes' Prayer to Calliope and Apollo), 'the whole world' (Mesomedes' Hymn to the Sun). In these phrases, the accent of the second word is higher than or on the same level as that of the first word, and just as with phrases such as mentioned above, the lack of fall in pitch appears to represent some sort of assimilation or  When a circumflex occurs immediately before a comma, it also regularly has a single note in the music, as in 'delightful' in the Mesomedes' ''Invocation to Calliope'' illustrated above. Other examples are 'famous', 'with arrows' in 2nd Delphic hymn, 'you live' in the Seikilos epitaph, and , and in Mesomedes' ''Hymn to Nemesis''.

Another place where a circumflex sometimes has a level note in the music is when it occurs in a penultimate syllable of a word, with the fall only coming in the following syllable. Examples are , (1st Delphic hymn), , , and (2nd Delphic hymn), and , (''Hymn to Nemesis'').

When a circumflex occurs immediately before a comma, it also regularly has a single note in the music, as in 'delightful' in the Mesomedes' ''Invocation to Calliope'' illustrated above. Other examples are 'famous', 'with arrows' in 2nd Delphic hymn, 'you live' in the Seikilos epitaph, and , and in Mesomedes' ''Hymn to Nemesis''.

Another place where a circumflex sometimes has a level note in the music is when it occurs in a penultimate syllable of a word, with the fall only coming in the following syllable. Examples are , (1st Delphic hymn), , , and (2nd Delphic hymn), and , (''Hymn to Nemesis'').

Grave accent

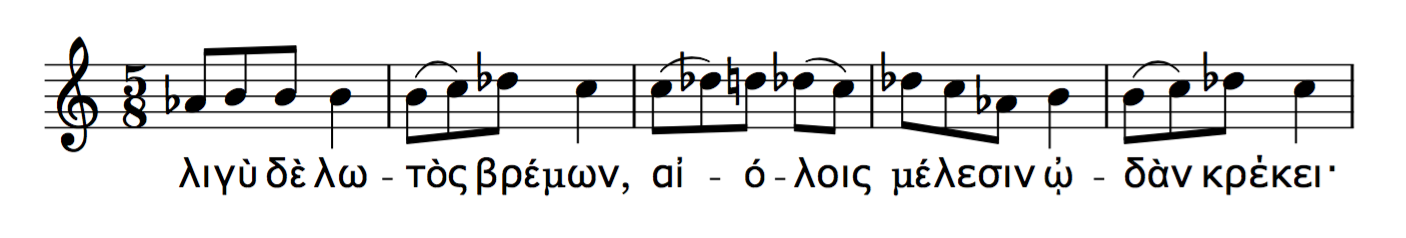

The third accentual mark used in ancient Greek was the grave accent, which is only found on the last syllable of words e.g. 'a good man'. Scholars are divided about how this was pronounced; whether it meant that the word was completely accentless or whether it meant a sort of intermediate accent is unclear. In some early documents making use of written accents, a grave accent could often be added to any syllable with low pitch, not just the end of the word, e.g. . Some scholars, such as the Russian linguist However, occasionally the syllable with the grave can be slightly higher than the rest of the word. This usually occurs when the word with a grave forms part of a phrase in which the music is in any case rising to an accented word, as in 'and you, wise initiator into the mysteries' in the Mesomedes prayer illustrated above, or in 'and the pipe, sounding clearly, weaves a song with shimmering melodies' in the 1st Delphic hymn:

However, occasionally the syllable with the grave can be slightly higher than the rest of the word. This usually occurs when the word with a grave forms part of a phrase in which the music is in any case rising to an accented word, as in 'and you, wise initiator into the mysteries' in the Mesomedes prayer illustrated above, or in 'and the pipe, sounding clearly, weaves a song with shimmering melodies' in the 1st Delphic hymn:

In the Delphic hymns, a grave accent is almost never followed by a note lower than itself. However, in the later music, there are several examples where a grave is followed by a fall in pitch, as in the phrase below, 'the harsh fate of mortals turns' (''Hymn to Nemesis''), where the word 'harsh, grey-eyed' has a fully developed accent:

In the Delphic hymns, a grave accent is almost never followed by a note lower than itself. However, in the later music, there are several examples where a grave is followed by a fall in pitch, as in the phrase below, 'the harsh fate of mortals turns' (''Hymn to Nemesis''), where the word 'harsh, grey-eyed' has a fully developed accent:

When an oxytone word such as 'good' comes before a comma or full stop, the accent is written as an acute. Several examples in the music illustrate this rise in pitch before a comma, for example 'wise Calliope' illustrated above, or in the first line of the Hymn to Nemesis ('Nemesis, winged tilter of the scales of life'):

When an oxytone word such as 'good' comes before a comma or full stop, the accent is written as an acute. Several examples in the music illustrate this rise in pitch before a comma, for example 'wise Calliope' illustrated above, or in the first line of the Hymn to Nemesis ('Nemesis, winged tilter of the scales of life'):

There are almost no examples in the music of an oxytone word at the end of a sentence except the following, where the same phrase is repeated at the end of a stanza. Here the pitch drops and the accent appears to be retracted to the penultimate syllable:

There are almost no examples in the music of an oxytone word at the end of a sentence except the following, where the same phrase is repeated at the end of a stanza. Here the pitch drops and the accent appears to be retracted to the penultimate syllable:

This, however, contradicts the description of the ancient grammarians, according to whom a grave became an acute (implying that there was a rise in pitch) at the end of a sentence just as it does before a comma.

This, however, contradicts the description of the ancient grammarians, according to whom a grave became an acute (implying that there was a rise in pitch) at the end of a sentence just as it does before a comma.

General intonation

Devine and Stephens also note that it is also possible from the Delphic hymns to get some indication of the intonation of Ancient Greek. For example, in most languages there is a tendency for the pitch to gradually become lower as the clause proceeds. This tendency, known as downtrend or downdrift, seems to have been characteristic of Greek too. For example, in the second line of the 1st Delphic Hymn, there is a gradual descent from a high pitch to a low one, followed by a jump up by an octave for the start of the next sentence. The words () mean: 'Come, so that you may hymn with songs your brother Phoebus, the Golden-Haired': However, not all sentences follow this rule, but some have an upwards trend, as in the clause below from the first Delphic hymn, which when restored reads 'how you seized the prophetic tripod which the great snake was guarding'. Here the whole sentence rises up to the emphatic word 'serpent':

However, not all sentences follow this rule, but some have an upwards trend, as in the clause below from the first Delphic hymn, which when restored reads 'how you seized the prophetic tripod which the great snake was guarding'. Here the whole sentence rises up to the emphatic word 'serpent':

In English before a comma, the voice tends to remain raised, to indicate that the sentence is not finished, and this appears to be true of Greek also. Immediately before a comma, a circumflex accent does not fall but is regularly set to a level note, as in the first line of the

In English before a comma, the voice tends to remain raised, to indicate that the sentence is not finished, and this appears to be true of Greek also. Immediately before a comma, a circumflex accent does not fall but is regularly set to a level note, as in the first line of the  A higher pitch is also used for proper names and for emphatic words, especially in situations where a non-basic word-order indicates emphasis or focus. An example occurs in the second half of the

A higher pitch is also used for proper names and for emphatic words, especially in situations where a non-basic word-order indicates emphasis or focus. An example occurs in the second half of the  Another circumstance in which no downtrend is evident is when a non-lexical word is involved, such as 'so that' or 'this'. In the music the accent in the word following non-lexical words is usually on the same pitch as the non-lexical accent, not lower than it. Thus there is no downtrend in phrases such as 'this crag' or 'so that Phoebus', where in each case the second word is more important than the first:

Another circumstance in which no downtrend is evident is when a non-lexical word is involved, such as 'so that' or 'this'. In the music the accent in the word following non-lexical words is usually on the same pitch as the non-lexical accent, not lower than it. Thus there is no downtrend in phrases such as 'this crag' or 'so that Phoebus', where in each case the second word is more important than the first:

Phrases containing a genitive, such as 'Leto's son' quoted above, or 'thighs of bulls' in the illustration below from the first Delphic hymn, also have no downdrift, but in both of these the second word is slightly higher than the first:

Phrases containing a genitive, such as 'Leto's son' quoted above, or 'thighs of bulls' in the illustration below from the first Delphic hymn, also have no downdrift, but in both of these the second word is slightly higher than the first:

Strophe and antistrophe

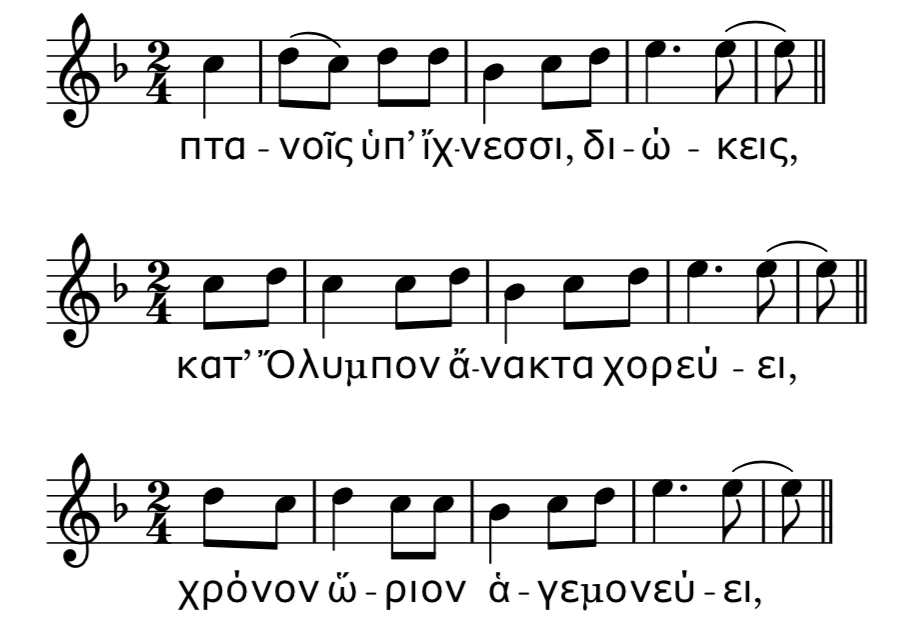

One problem which has been discussed concerning the relationship between music and word accent is what may have happened in choral music which was written in pairs of corresponding stanzas known as ''strophe'' and ''antistrophe''. Rhythmically these always correspond exactly but the word accents in the antistrophe generally do not match those in the strophe. Since none of the surviving music includes both a strophe and antistrophe, it is not clear whether the same music was written for both stanzas, ignoring the word accents in one or the other, or whether the music was similar but varied slightly to account for the accents. The following lines from Mesomedes' Hymn to the Sun, which are very similar but with slight variations in the first five notes, show how this might have been possible:

Change to modern Greek

In modern Greek the accent is for the most part in the same syllable of the words as it was in ancient Greek, but is one of stress rather than pitch, so that an accented syllable, such as the first syllable in the word , can be pronounced sometimes on a high pitch, and sometimes on a low pitch. It is believed that this change took place around 2nd–4th century AD, at around the same time that the distinction between long and short vowels was also lost. One of the first writers to compose poetry based on a stress accent was the 4th-centuryRules for the placement of the accent

Law of Limitation

The accent may not come more than three syllables from the end of a word. If an accent comes on the antepenultimate syllable, it is always an acute, for example: * 'sea' * 'they did' * 'person' * 'people' * 'I want' Exception: 'of what sort of', in which the second part is an enclitic word. With a few exceptions, the accent can come on the antepenult only if the last syllable of the word is 'light'. The last syllable counts as light if it ends in a short vowel, or if it ends in a short vowel followed by no more than one consonant, or if the word ends in or , as in the above examples. But for words like the following, which have a heavy final syllable, the accent moves forward to the penultimate: * 'of a man' * 'for men' * 'I wanted' The ending always counts as long, and in the() Law

If the accent comes on the penultimate syllable, it must be a circumflex if the last two vowels of the word are long–short. This applies even to words ending in or : * 'body' * 'slave' * 'herald' * 'storm' This rule is known as the () Law, since in the accusative case the word 'saviour' becomes . In most cases, a final or counts as a short vowel: * 'sailors' * 'to do' * 'slaves' Otherwise the accent is an acute: * 'sailor' * 'he orders' * 'for slaves (dative)' Exception 1: Certain compounds made from an ordinary word and an enclitic suffix have an acute even though they have long vowel–short vowel: * 'these', 'this (fem.)' (but 'of these') * 'that (as a result)', 'nor' * 'if only' * 'no one' (but as a name in the Odyssey, ) Exception 2: In locative expressions and verbs in theLaw of Persistence

The third principle of Greek accentuation is that, after taking into account the Law of Limitation and the () Law, the accent in nouns, adjectives, and pronouns remains as far as possible on the same syllable (counting from the beginning of the word) in all the cases, numbers, and genders. For example: * 'yoke', pl. 'yokes' * 'soldier', 'soldiers' * , pl. 'fathers' * , pl. 'bodies' But an extra syllable or a long ending causes accent shift: * , pl. 'names' * , fem. 'just' * , gen.pl. 'of bodies'Exceptions to the Law of Persistence

There are a number of exceptions to the Law of Persistence. Exception 1: The following words have the accent on a different syllable in the plural: * , pl. 'men' * , pl. (poetic ) 'daughters' * , pl. 'mothers' The accusative singular and plural has the same accent as the nominative plural given above. The name 'Demeter' changes its accent to accusative , genitive , dative . Exception 2: Certain vocatives (mainly of the 3rd declension) have recessive accent: * , 'o Socrates' * , 'o father' Exception 3: All 1st declension nouns, and all 3rd declension neuter nouns ending in , have a genitive plural ending in . This also applies to 1st declension adjectives, but only if the feminine genitive plural is different from the masculine: * 'soldier', gen.pl. 'of soldiers' * 'the wall', gen.pl. 'of the walls' Exception 4: Some 3rd declension nouns, including all monosyllables, place the accent on the ending in the genitive and dative singular, dual, and plural. (This also applies to the adjective 'all' but only in the singular.) Further details are given below. * 'foot', acc.sg. , gen.sg. , dat.sg. Exception 5: Some adjectives, but not all, move the accent to the antepenultimate when neuter: * 'better', neuter *But: 'graceful', neuter Exception 6: The following adjective has an accent on the second syllable in the forms containing : * , pl. 'big'Oxytone words

Oxytone words, that is, words with an acute on the final syllable, have their own rules.Change to a grave

Normally in a sentence, whenever an oxytone word is followed by a non-enclitic word, the acute is changed to a grave; but before a pause (such as a comma, colon, full stop, or verse end), it remains an acute: * 'a good man' (Not all editors follow the rule about verse end.) The acute also remains before an enclitic word such as 'is': * 'he's a good man' In the words 'who?' and 'what? why?', however, the accent always remains acute, even if another word follows: * 'who is that?' * 'what are you doing?'Change to a circumflex

When a noun or adjective is used in different cases, a final acute often changes to a circumflex. In the 1st and 2nd declension, oxytone words change the accent to a circumflex in the genitive and dative. This also applies to the dual and plural, and to the definite article: * 'the god', acc.sg. – gen. sg. 'of the god', dat.sg. 'to the god' However, oxytone words in the 'Attic' declension keep their acute in the genitive and dative: * 'in the temple' 3rd declension nouns like 'king' change the acute to a circumflex in the vocative and dative singular and nominative plural: * , voc.sg. , dat.sg. , nom.pl. or Adjectives of the type 'true' change the acute to a circumflex in all the cases which have a long vowel ending: * , acc.sg. , gen.sg. , dat.sg. , nom./acc.pl. , gen.pl. Adjectives of the type 'pleasant' change the acute to a circumflex in the dative singular and nominative and accusative plural: * , dat.sg. , nom./acc.pl.Accentless words

The following words have no accent, only a breathing: *the forms of the article beginning with a vowel ( ) *the prepositions 'in', 'to, into', 'from' *the conjunction 'if' *the conjunction 'as, that' (also a preposition 'to') *the negative adverb 'not'. However, some of these words can have an accent when they are used in emphatic position. are written when the meaning is 'who, which'; and is written if it ends a sentence.The definite article

The definite article in the nominative singular and plural masculine and feminine just has a rough breathing, and no accent: * 'the god' * 'the gods' Otherwise the nominative and accusative have an acute accent, which in the context of a sentence, is written as a grave: * 'the god' (accusative) * 'the weapons' The genitive and dative (singular, plural and dual), however, are accented with a circumflex: * 'of the house' (genitive) * 'for the god' (dative) * 'for the gods' (dative plural) * 'of/to the two goddesses' (genitive or dative dual) 1st and 2nd declension oxytones, such as , are accented the same way as the article, with a circumflex in the genitive and dative.Nouns

1st declension

=Types

= Those ending in short are all recessive: * 'sea', 'Muse (goddess of music)', 'queen', 'bridge', 'truth', 'dagger', 'tongue, language' Of those which end in long or , some have penultimate accent: * 'house', 'country', 'victory', 'battle', 'day', 'chance', 'necessity', 'craft', 'peace' Others are oxytone: * 'market', 'army', 'honour', 'empire; beginning', 'letter', 'head', 'soul', 'council' A very few have a contracted ending with a circumflex on the last syllable: * 'earth, land', 'Athena', 'mina (coin)' Masculine 1st declension nouns usually have penultimate accent: * 'soldier', 'citizen', 'young man', 'sailor', 'Persian', 'master', 'Alcibiades', 'Miltiades' A few, especially agent nouns, are oxytone: * 'poet', 'judge', 'learner, disciple', 'athlete', 'piper' There are also some with a contracted final syllable: * 'Hermes', 'the North Wind'=Accent movement

= In proparoxytone words like , with a short final vowel, the accent moves to the penultimate in the accusative plural, and in the genitive and dative singular, dual, and plural, when the final vowel becomes long: * 'sea', gen. 'of the sea' In words with penultimate accent, the accent is persistent, that is, as far as possible it stays on the same syllable when the noun changes case. But if the last two vowels are long–short, it changes to a circumflex: * 'soldier', nom.pl. 'the soldiers' In oxytone words, the accent changes to a circumflex in the genitive and dative (also in the plural and dual), just as in the definite article: * 'of the army', 'for the army' All 1st declension nouns have a circumflex on the final syllable in the genitive plural: * 'of soldiers', 'of days' The vocative of 1st declension nouns usually has the accent on the same syllable as the nominative. But the word 'master' has a vocative accented on the first syllable: * 'young man!', 'o poet' * 'master!'2nd declension

=Types

= The majority of 2nd declension nouns have recessive accent, but there are a few oxytones, and a very few with an accent in between (neither recessive nor oxytone) or contracted: * 'man', 'horse', 'war', 'island', 'slave', 'wοrd', 'death', 'life', 'sun', 'time', 'manner', 'law, custom', 'noise', 'circle' * 'god', 'river', 'road', 'brother', 'number', 'general', 'eye', 'heaven', 'son', 'wheel' * 'maiden', 'youth', 'hedgehog; sea-urchin' * 'mind' (contracted from ), 'voyage' Words of the 'Attic' declension ending in can also be either recessive or oxytone: * 'Menelaus', 'Minos' * 'temple', 'people' Neuter words are mostly recessive, but not all: * 'gift', 'tree', 'weapons', 'camp', 'boat', 'work', 'child', 'animal' * 'sign', 'oracle', 'school' * 'yoke', 'egg', 'fleet', 'temple' (the last two are derived from adjectives) Words ending in often have antepenultimate accent, especially diminutive words: * 'book', 'place', 'baby', 'plain' But some words are recessive, especially those with a short antepenultimate: * 'cloak', 'stade' (600 feet), 'race-course', 'lad'=Accent movement

= As with the first declension, the accent on 2nd declension oxytone nouns such as 'god' changes to a circumflex in the genitive and dative (singular, dual, and plural): * 'of the god', 'to the gods' But those in the Attic declension retain their acute: * 'of the people' Unlike in the first declension, barytone words do not have a circumflex in the genitive plural: * 'of the horses'3rd declension

=Types

= 3rd declension masculine and feminine nouns can be recessive or oxytone: * 'mother', 'daughter', 'guard', 'city', 'old man', 'lion', 'god', '=Accent movement

= The accent in the nominative plural and in the accusative singular and plural is usually on the same syllable as the nominative singular, unless this would break the three-syllable rule. Thus: * , pl. 'storms' * , pl. 'women' * , pl. 'fathers' * , pl. 'ships' * , pl. 'bodies' But, in accordance with the 3-syllable rule: * , nominative pl. 'names', gen. pl. The following are exceptions and have the accent on a different syllable in the nominative and accusative plural or the accusative singular: * , pl. 'men' * , pl. (poetic ) 'daughters' * , pl. 'mothers' But the following is recessive: * , acc. 'Demeter' Words ending in are all oxytone, but only in the nominative singular. In all other cases the accent is on the or : * 'king', nom.pl. or=Accent shift in genitive and dative

= In 3rd declension monosyllables the accent usually shifts to the final syllable in the genitive and dative. The genitive dual and plural have a circumflex: *singular: 'foot'dual: nom./acc. , gen./dat. '(pair of) feet'

plural: 'feet' *singular: 'night'

plural: The following are irregular in formation, but the accent moves in the same way: * } 'ship'

plural: * 'Zeus' The numbers for 'one', 'two', and 'three' also follow this pattern (see below). 'woman' and 'dog' despite not being monosyllables, follow the same pattern: * 'woman'

pl. * 'dog'

pl. There are some irregularities. The nouns 'boy' and 'Trojans' follow this pattern ''except'' in the genitive dual and plural: *singular 'boy'

The adjective 'all' has a mobile accent only in the singular: *singular :plural . Monosyllabic participles, such as 'being', and the interrogative pronoun 'who? what?' have a fixed accent. *singular :plural . The words 'father', 'mother', 'daughter', have the following accentuation: * 'father'

pl. 'stomach' is similar: * 'stomach'

pl. } The word 'man' has the following pattern, with accent shift in the genitive singular and plural: * 'man'

pl. 3rd declension neuter words ending in have a circumflex in the genitive plural, but are otherwise recessive: * 'wall', gen.pl. 'of walls' Concerning the genitive plural of the word 'trireme', there was uncertainty. 'Some people pronounce it barytone, others perispomenon,' wrote one grammarian. Nouns such as 'city' and 'town' with genitive singular 'city' keep their accent on the first syllable in the genitive singular and plural, despite the long vowel ending: * 'city'

pl. 3rd declension neuter nouns ending in have a circumflex in the genitive plural, but are otherwise recessive: * 'wall'

pl.

=Vocative

= Usually in 3rd declension nouns the accent becomes recessive in the vocative: * 'father!', 'madam!', 'o Socrates', , , However, the following have a circumflex on the final syllable: * 'o Zeus', 'o king'Adjectives

Types

Adjectives frequently have oxytone accentuation, but there are also barytone ones, and some with a contracted final syllable. Oxytone examples are: * 'good', 'bad', 'beautiful', 'fearsome', 'Greek', 'wise', 'strong', 'long', 'shameful', , 'small', 'faithful', 'difficult' * 'left-hand', 'right-hand' * 'pleasant', 'sharp, high-pitched', 'heavy, low-pitched', 'fast', 'slow', 'deep', 'sweet'. (The feminine of all of these has .) * 'much', plural 'many' * 'true', 'lucky', 'unfortunate', 'weak, sick', 'safe' Recessive: * 'friendly', 'enemy', 'just', 'rich', 'worthy', 'Spartan', 'easy' * 'foolish', 'unjust', 'new, young', 'alone', 'useful', 'made of stone', 'wooden' * 'other', 'each' * 'your', 'our' * 'propitious' * 'kindly', 'bad-smelling', 'happy'. (For other compound adjectives, see below.) * 'all', plural Paroxytone: * 'little', 'opposite', 'near' * 'great, big', fem. , plural Properispomenon: * 'Athenian', 'brave' * 'ready', 'deserted' * 'such', 'so great' Perispomenon: * 'golden', 'bronze' Comparative and superlative adjectives all have recessive accent: * 'wiser', 'very wise' * 'greater', 'very great' Adjectives ending in have a circumflex in most of the endings, since these are contracted: * 'true', masculine plural 'foolish' is oxytone in the New Testament: * 'and five of them were foolish' (Matthew 25.2) Personal names derived from adjectives are usually recessive, even if the adjective is not: * 'Athenaeus', from 'Athenian' * , from 'grey-eyed'Accent movement

Unlike in modern Greek, which has fixed accent in adjectives, an antepenultimate accent moves forward when the last vowel is long: * 'friendly (masc.)', 'friendly (fem.)', fem.pl. The genitive plural of feminine adjectives is accented , but only in those adjectives where the masculine and feminine forms of the genitive plural are different: * 'all', gen.pl. 'of all (masc.)', 'of all (fem.)' But: * 'just', gen.pl. (both genders) In a barytone adjective, in the neuter, when the last vowel becomes short, the accent usually recedes: * 'better', neuter However, when the final was formerly * , the accent does not recede (this includes neuter participles): * 'graceful', neuter * 'having done', neuter The adjective 'great' shifts its accent to the penultimate in forms of the word that contain ''lambda'' ( ): * 'great', plural The masculine 'all' and neuter have their accent on the ending in genitive and dative, but only in the singular: * 'all', gen.sg. , dat.sg. (but gen.pl. , dat.pl. ) The participle 'being', genitive , has fixed accent.Elided vowels

When the last vowel of an oxytone adjective is elided, an acute (not a circumflex) appears on the penultimate syllable instead: * 'he was doing dreadful things' (for ) * 'many good things' (for ) This rule also applies to verbs and nouns: * 'take (the cup), o stranger' (for ) But it does not apply to minor words such as prepositions or 'but': *'the fox knows many things, but the hedgehog one big thing' (Archilochus) The retracted accent was always an acute. The story was told of an actor who, in a performance of Euripides' play ''Orestes'', instead of pronouncing 'I see a calm sea', accidentally said 'I see a weasel', provoking laughter in the audience and mockery the following year in Aristophanes' ''Frogs''.

Compound nouns and adjectives

Ordinary compounds, that is, those which are not of the type 'object+verb', usually have recessive accent: * 'hippopotamus' ('horse of the river') * 'Timothy' ('honouring God') * 'ally' ('fighting alongside') * 'philosopher' ('loving wisdom') * 'mule' ('half-donkey') But there are some which are oxytone: * 'high priest' * 'actor, hypocrite' Compounds of the type 'object–verb', if the penultimate syllable is long or heavy, are usually oxytone: * 'general' ('army-leader') * 'farmer' ('land-worker') * 'bread-maker' But 1st declension nouns tend to be recessive even when the penultimate is long: * 'book-seller' * 'informer' (lit. 'fig-revealer') Compounds of the type 'object+verb' when the penultimate syllable is short are usually paroxytone: * 'cowherd' * 'spear-bearer' * 'discus-thrower' * 'look-out man' (lit. 'day-watcher') But the following, formed from 'I hold', are recessive: * 'who holds the aegis' * 'holder of an allotment (of land)'Adverbs

Adverbs formed from barytone adjectives are accented on the penultimate, as are those formed from adjectives ending in ; but those formed from other oxytone adjectives are perispomenon: * 'brave', 'bravely' * 'just', 'justly' * , 'pleasant', 'with pleasure' * , 'beautiful', 'beautifully' * , 'true', 'truly' Adverbs ending in have penultimate accent: * 'often'Numbers

The first three numbers have mobile accent in the genitive and dative: * 'one (m.)', acc. , gen. 'of one', dat. 'to or for one' * 'one (f.)', acc. , gen. , dat. * 'two', gen/dat. * 'three', gen. , dat. Despite the circumflex in , the negative 'no one (m.)' has an acute. It also has mobile accent in the genitive and dative: * 'no one (m.)', acc. , gen. 'of no one', dat. 'to no one' The remaining numbers to twelve are: * 'four', 'five', 'six', 'seven', 'eight', 'nine', 'ten', 'eleven' 'twelve' Also commonly found are: * 'twenty', 'thirty', 'a hundred', 'a thousand'. Ordinals all have recessive accent, except those ending in : * 'first', 'second', 'third' etc., but 'twentieth'Pronouns

The personal pronouns are the following: * 'I', 'you (sg.)', 'him(self)' * 'we two', 'you two' * 'we', 'you (pl.)', 'they' The genitive and dative of all these personal pronouns has a circumflex, except for the datives , , and : * 'of me', 'for you (pl.)', 'to him(self)' * 'for me', 'for you', and 'for them(selves)' The oblique cases of , 'you (sg.)', , and can also be used enclitically when they are unemphatic (see below under Enclitics), in which case they are written without accents. When enclitic, , , and are shortened to , , and : * 'it is possible for you' * 'tell me' * 'for this apparently was their custom' (Xenophon) The accented form is usually used after a preposition: * 'Cyrus sent me to you' * (sometimes ) 'to me' The pronouns 'he himself', 'himself (reflexive)', and 'who, which' change the accent to a circumflex in the genitive and dative: * 'him', 'of him, his', 'to him', 'to them', etc. Pronouns compounded with 'this' and are accented as if the second part was an enclitic word. Thus the accent of does not change to a circumflex even though the vowels are long–short: * 'these', 'of which things' The demonstratives 'this' and 'that' are both accented on the penultimate syllable. But 'this man here' is oxytone. When means 'who?' is it always accented, even when not before a pause. When it means 'someone' or 'a certain', it is enclitic (see below under Enclitics): * 'to someone' * 'to whom?' The accent on is fixed and does not move to the ending in the genitive or dative.Prepositions

'in', 'to, into', and 'from, out of' have no accent, only a breathing. * 'in him' Most other prepositions have an acute on the final when quoted in isolation (e.g. 'from', but in the context of a sentence this becomes a grave. When elided this accent does not retract and it is presumed that they were usually pronounced accentlessly: * 'to him' * 'from him' When a preposition follows its noun, it is accented on the first syllable (except for 'around' and 'instead of'): * 'about what?' The following prepositions were always accented on the first syllable in every context: * 'without', 'until, as far as'Interrogative words

Interrogative words are almost all accented recessively. In accordance with the principle that in a monosyllable the equivalent of a recessive accent is a circumflex, a circumflex is used on a long-vowel monosyllable: * 'when?', 'where from?', 'A... or B?', 'what kind of?', 'how much?', 'how many?' * , 'is it the case that...?' * 'where?', 'where to?', 'which way?' Two exceptions, with paroxytone accent, are the following: * 'how big?', 'how old?', 'how often?' The words and always keep their acute accent even when followed by another word. Unlike other monosyllables, they do not move the accent to the ending in the genitive or dative: * 'who? which?', 'what?', 'why?', 'which people?', 'of what? whose?', 'to whom?', 'about what?' Some of these words, when accentless or accented on the final, have an indefinite meaning: * 'someone', 'some people', 'once upon a time', etc. When used in indirect questions, interrogative words are usually prefixed by or . The accentuation differs. The following are accented on the second syllable: * 'when', 'from where', 'how great', 'which of the two' But the following are accented on the first: * 'where', 'to where', 'who'Enclitics

Types of enclitic

'he ordered the slave-boy to run and ask the man to wait for him' (Plato) Some of these pronouns also have non-enclitic forms which are accented. The non-enclitic form of 'me', 'of me', 'to me' is . The accented forms are used at the beginning of a sentence and (usually) after prepositions: * 'I'm calling you' * 'in you'

Enclitic rules

When an enclitic follows a proparoxytone or a properispomenon word, the main word has two accents: * 'certain Greeks' * 'he's a slave' When it follows an oxytone word or an accentless word, there is an acute on the final syllable: * 'tell me' * 'if anyone' When it follows perispomenon or paroxytone word, there is no additional accent, and a monosyllabic enclitic remains accentless: * 'I see you' * 'tell me' A two-syllable enclitic has no accent after a perispomenon: * 'of some good thing' * 'of some archers' But a two-syllabled enclitic has one after a paroxytone word (otherwise the accent would come more than three syllables from the end of the combined word). After a paroxytone has a circumflex: * 'certain others' * 'of some weapons' A word ending in or behaves as if it was paroxytone and does not take an additional accent: * 'he is a herald' A two-syllable enclitic is also accented after an elision: * 'there are many' When two or three enclitics come in a row, according to Apollonius andVerbs

In verbs, the accent is grammatical rather than lexical; that is to say, it distinguishes different parts of the verb rather than one verb from another. In the indicative mood it is usually recessive, but in other parts of the verb it is often non-recessive. Except for the nominative singular of certain participles (e.g., masculine , neuter 'after taking'), a few imperatives (such as 'say'), and the irregular present tenses ( 'I say' and 'I am'), no parts of the verb are oxytone.Indicative

In the indicative of most verbs, other than contracting verbs, the accent is recessive, meaning it moves as far back towards the beginning of the word as allowed by the length of the last vowel. Thus, verbs of three or more syllables often have an acute accent on the penult or antepenult, depending on whether the last vowel is long or short (with final counted as short): * 'I give' * 'I take' * 'he orders' * 'he ordered' * 'I want' Monosyllabic verbs, such as 'he went' (poetic) and 'you are', because they are recessive, have a circumflex. An exception is or 'you say'. A few 3rd person plurals have a contracted ending (the other persons are recessive): * 'they send off' * 'they stand (transitive)' * 'they have died' * 'they are standing (intransitive)' When a verb is preceded by an augment, the accent goes no further back than the augment itself: * 'it was possible' * 'they entered'Contracting verbs

Contracting verbs are underlyingly recessive, that is, the accent is in the same place it had been before the vowels contracted. When an acute and a non-accented vowel merge, the result is a circumflex. In practice therefore, several parts of contracting verbs are non-recessive: * 'I do' (earlier ) * 'I was doing' (earlier ) * 'they do' (earlier ) Contracting futures such as 'I will announce' and 'I will say' are accented like .Imperative

The accent is recessive in the imperative of most verbs: * 'say!' * 'crucify!' * 'remember!' * 'eat!' * 'give (pl.)!' * 'go away (sg.)!' * 'go across (sg.)!' * 'say!' In compounded monosyllabic verbs, however, the imperative is paroxytone: * 'give back!' * 'place round!' The strong aorist imperative active (2nd person singular only) of the following five verbs (provided they are not prefixed) is oxytone: * 'say', 'come', 'find', 'see', 'take!' (the last two inSubjunctive

The subjunctive of regular thematic verbs in the present tense or the weak or strong aorist tense is recessive, except for the aorist passive: * 'he may say' * 'they may say' * 'he may free' * 'he may take' It is also recessive in the verb 'I go' and verbs ending in : * 'he may go away' * 'he may point out' But in the aorist passive, in the compounded aorist active of 'I go', and in all tenses of other athematic verbs, it is non-recessive: * 'I may be freed' * 'I may appear' * 'he may go across' * 'they may give', * 'I may stand' * 'I may hand over' * 'it may be possible'Optative

The optative similarly is recessive in regular verbs in the same tenses. The optative endings and count as long vowels for the purpose of accentuation: * 'he might free' * 'he might take' But in the aorist passive, in the compounded aorist active of 'I go', and in all tenses of athematic verbs (other than 'I go' and verbs ending in ), it is non-recessive: * 'they might be freed' * 'they might appear' * 'they might go across' * 'they might give' * 'they might stand' * 'they might hand over' But 'he might go away' is accented recessively like a regular verb.Infinitive

The present and future infinitive of regular thematic verbs is recessive: * 'to say' * 'to be going to free' * 'to want' * 'to be going to be' But all other infinitives are non-recessive, for example the weak aorist active: * 'to prevent' * 'to punish' Strong aorist active and middle: * 'to take' * 'to become' * 'to arrive' Weak and strong aorist passive: * 'to be freed' * 'to appear' The aorist active of 'I go' when compounded: * 'to go across' The present and aorist infinitives of all athematic verbs: * 'to give' * 'to go' * 'to be possible' * 'to betray' But the Homeric 'to be' and 'to give' are recessive. The perfect active, middle, and passive: * 'to have freed' * 'to have been freed'Participles

The present, future and weak aorist participles of regular thematic verbs are recessive: * 'saying' * 'wanting' * 'going to free' * 'having heard' But all other participles are non-recessive. These include the strong aorist active: * , masc. pl. , fem. sg. 'after taking' The weak and strong aorist passive: * , masc. pl. , fem.sg. 'after being freed' * , masc. pl. , fem.sg. 'after appearing' The compounded aorist active of 'I go': * , , fem.sg. 'after going across' The present and aorist participles of athematic verbs: * 'giving', masc.pl. , fem.sg. * , masc.pl. , fem.sg. 'going' * , masc.pl. , fem.sg. 'after handing over' * (neuter) 'it being possible' The perfect active, middle, and passive: * , masc. pl. , fem.sg. 'having freed' * 'having been freed''I am' and 'I say'

Two athematic verbs, 'I am' and 'I say', are exceptional in that in the present indicative they are usually enclitic. When this happens they put an accent on the word before them and lose their own accent: * 'I am responsible' * 'he says ... not' But both verbs can also begin a sentence, or follow a comma, or an elision, in which case they are not enclitic. In this case the accent is usually on the final syllable (e.g. , ). When it follows an elision, is also accented on the final: * 'what (ever) is it?' However, the 3rd person singular also has a strong form, , which is used 'when the word expresses existence or possibility (i.e. when it is translatable with expressions such as 'exists', 'there is', or 'it is possible').' This form is used among other places in the phrase 'it is not' and at the beginning of sentences, such as: * 'The sea exists; and who shall quench it?' The 2nd person singular 'you are' and 'you say' are not enclitic. The future of the verb 'to be' has its accent on the verb itself even when prefixed: * 'he will be away'Verbal adjectives

The verbal adjectives ending in and are always paroxytone: * 'he needs to be punished' * 'it is necessary to punish wrong-doers' The adjective ending in is usually oxytone, especially when it refers to something which is capable of happening: * 'famous (able to be heard about)' * 'capable of being taken apart' * 'made, adopted'Accent shift laws

Comparison with Sanskrit as well as the statements of grammarians shows that the accent in some Greek words has shifted from its position in Proto-Indo-European.Wheeler's Law

Bartoli's Law

Bartoli's Law (pronunciation /'bartoli/), proposed in 1930, aims to explain how some oxytone words ending in the rhythmVendryes's Law

Vendryes's Law (pronunciation /vɑ̃dʁi'jɛs]/), proposed in 1945, describes how words of the rhythmDialect variations

The ancient grammarians were aware that there were sometimes differences between their own accentuation and that of other dialects, for example that of the Homeric poems, which they could presumably learn from the traditional sung recitation.Attic

Some peculiarities ofAeolic

The Aeolic Greek, Aeolic pronunciation, exemplified in the dialect of the 7th-century BC poetsDoric

TheSee also

*References

Notes

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *External links

Prayer to Calliope and Apollo

Sung to the lyre by Stefan Hagel. {{Ancient Greek grammar Ancient Greek Greek grammar Tone (linguistics)