Laurier Cup on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Sir Henri Charles Wilfrid Laurier, ( ; ; November 20, 1841 – February 17, 1919) was a Canadian lawyer, statesman, and politician who served as the seventh

Laurier then practised law in

Laurier then practised law in

As a

As a

In the 1891 federal election, Laurier faced Conservative Prime Minister

In the 1891 federal election, Laurier faced Conservative Prime Minister

Laurier's government also constructed a third railway: the

Laurier's government also constructed a third railway: the

Laurier stayed on as Liberal leader. In December 1912, he started leading the filibuster and fight against the Conservatives' own naval bill which would have sent $35 million directly to the British Navy. Laurier argued that this threatened Canadian autonomy. After six months of battling the bill, the bill was blocked by the Liberal-controlled

Laurier stayed on as Liberal leader. In December 1912, he started leading the filibuster and fight against the Conservatives' own naval bill which would have sent $35 million directly to the British Navy. Laurier argued that this threatened Canadian autonomy. After six months of battling the bill, the bill was blocked by the Liberal-controlled

Wilfrid Laurier married Zoé Lafontaine in Montreal on May 13, 1868. She was the daughter of G.N.R. Lafontaine and his first wife, Zoé Tessier known as Zoé Lavigne. Laurier's wife Zoé was born in Montreal and educated there at the School of the Bon Pasteur, and at the Convent of the Sisters of the Sacred Heart, St. Vincent de Paul. The couple lived at Arthabaskaville until they moved to Ottawa in 1896. She served as one of the vice presidents on the formation of the National Council of Women and was honorary vice president of the

Wilfrid Laurier married Zoé Lafontaine in Montreal on May 13, 1868. She was the daughter of G.N.R. Lafontaine and his first wife, Zoé Tessier known as Zoé Lavigne. Laurier's wife Zoé was born in Montreal and educated there at the School of the Bon Pasteur, and at the Convent of the Sisters of the Sacred Heart, St. Vincent de Paul. The couple lived at Arthabaskaville until they moved to Ottawa in 1896. She served as one of the vice presidents on the formation of the National Council of Women and was honorary vice president of the

Laurier is commemorated by three National Historic Sites.

The Sir Wilfrid Laurier National Historic Site is in his birthplace, Saint-Lin-Laurentides, a town north of

Laurier is commemorated by three National Historic Sites.

The Sir Wilfrid Laurier National Historic Site is in his birthplace, Saint-Lin-Laurentides, a town north of

Canada is Civ 6’s latest arrival, and they’re too nice to declare surprise wars.

PCGamesN. Retrieved 17 December 2020.

online

* Brown, Craig, and Ramsay Cook, ''Canada: 1896–1921 A Nation Transformed'' (1983), standard history * Cook, Ramsay. "Dafoe, Laurier, and the Formation of Union Government." ''Canadian Historical Review'' 42#3 (1961) pp: 185–208. * Dafoe, J. W. ''Laurier: A Study in Canadian Politics'' (1922) * Dutil, Patrice, and David MacKenzie, ''Canada, 1911: The Decisive Election that Shaped the Country'' (2011) * J.L. Granatstein, Granatstein, J.L. and

online

* Robertson, Barbara. ''Wilfrid Laurier: The Great Conciliator'' (1971) * Schull, Joseph. ''Laurier. The First Canadian'' (1965); biography * Oscar D. Skelton, Skelton, Oscar Douglas. ''Life and Letters of Sir Wilfrid Laurier'' 2v (1921); the standard biograph

v. 2 online free

* Oscar D. Skelton, Skelton, Oscar Douglas. ''The Day of Sir Wilfrid Laurier A Chronicle of our own Times'' (1916), short popular surve

online free

* Stewart, Gordon T. "Political Patronage under Macdonald and Laurier 1878–1911." ''American Review of Canadian Studies'' 10#1 (1980): 3–26. * Stewart, Heather Grace. ''Sir Wilfrid Laurier: the weakling who stood his ground'' (2006) ; for children * Peter Busby Waite, Waite, Peter Busby, ''Canada, 1874–1896: Arduous Destiny'' (1971), standard history

Wilfrid Laurier fonds

at Library and Archives Canada. * iarchive:wilfridlaurieron00lauruoft, ''Wilfrid Laurier on the platform; collection of the principal speeches made in Parliament or before the people, since his entry into active politics in 1871;'' by Wilfrid Laurier at archive.org

''Life and letters of Sir Wilfrid Laurier'' vol 1. at archive.org

''Life and letters of Sir Wilfrid Laurier'' vol 2. at archive.org

Photograph: Wilfrid Laurier, 1890

– McCord Museum

Photograph: Sir Wilfrid Laurier, c. 1900

– McCord Museum

Photograph: Wilfrid Laurier, 1906

– McCord Museum *

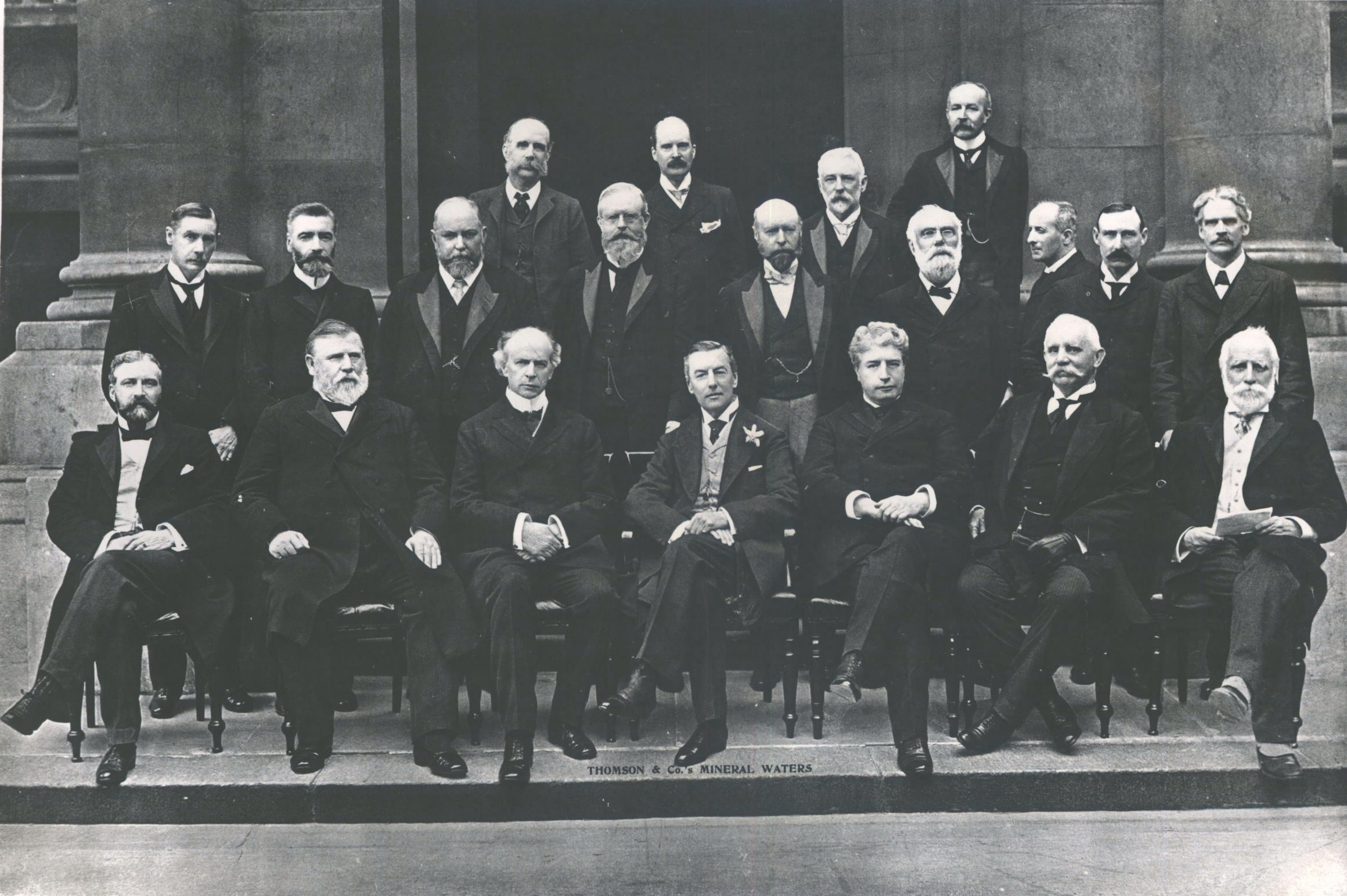

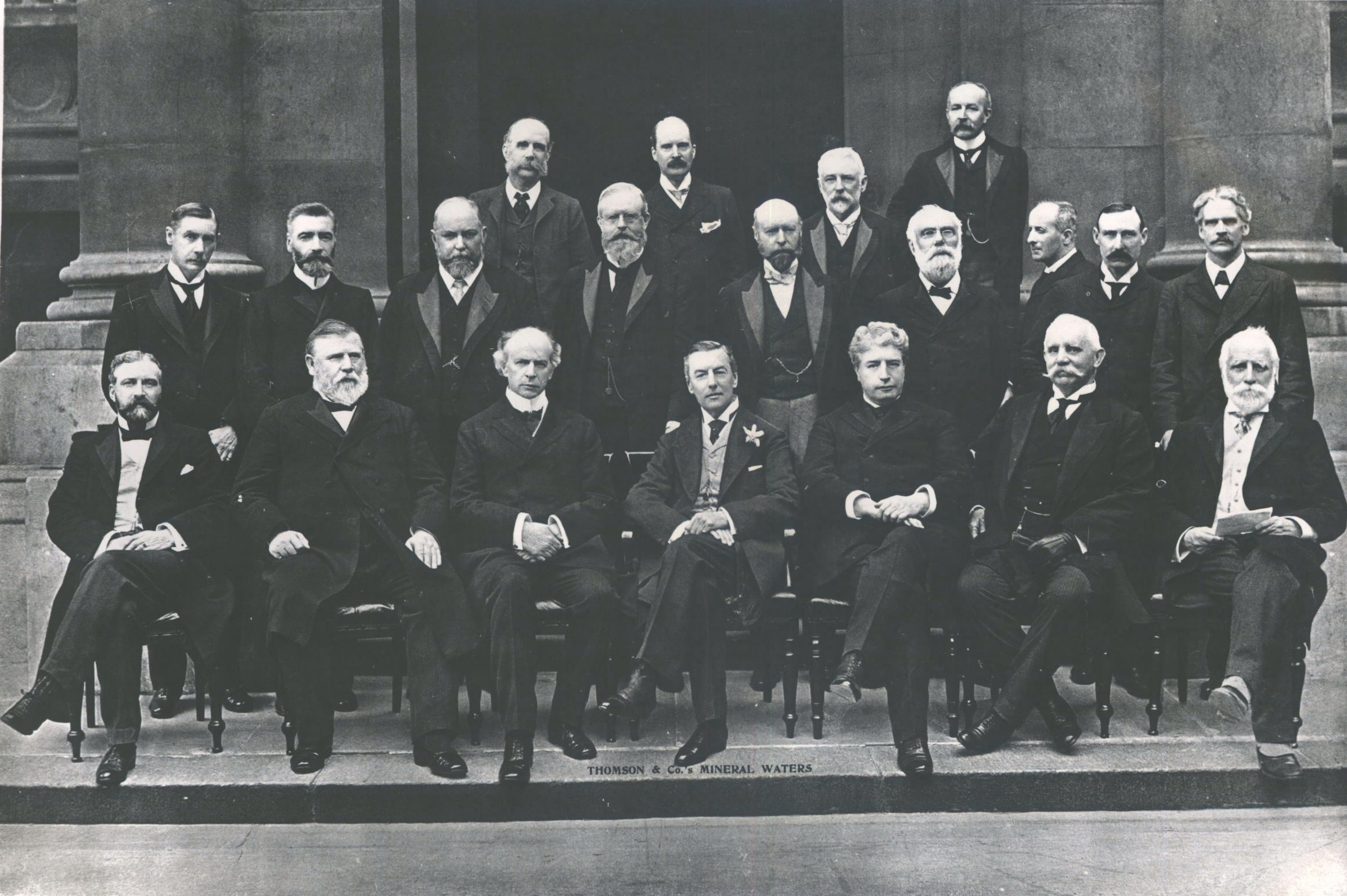

The 8th Canadian Ministry

- the Parliamentary website. {{DEFAULTSORT:Laurier, Wilfrid Wilfrid Laurier, 1841 births 1919 deaths Canadian Roman Catholics Canadian Knights Grand Cross of the Order of St Michael and St George Laurier Liberals, Leaders of the Liberal Party of Canada Leaders of the Opposition (Canada) Members of the House of Commons of Canada from Quebec Members of the House of Commons of Canada from the Northwest Territories Canadian members of the Privy Council of the United Kingdom Quebec Liberal Party MNAs Prime Ministers of Canada Lawyers in Quebec Quebec lieutenants Persons of National Historic Significance (Canada) French Quebecers Canadian King's Counsel McGill University Faculty of Law alumni Burials at Notre-Dame Cemetery (Ottawa)

prime minister of Canada

The prime minister of Canada (french: premier ministre du Canada, link=no) is the head of government of Canada. Under the Westminster system, the prime minister governs with the Confidence and supply, confidence of a majority the elected Hou ...

from 1896 to 1911. The first French Canadian

French Canadians (referred to as Canadiens mainly before the twentieth century; french: Canadiens français, ; feminine form: , ), or Franco-Canadians (french: Franco-Canadiens), refers to either an ethnic group who trace their ancestry to Fren ...

prime minister, his 15-year tenure remains the longest unbroken term of office among Canadian prime ministers and his nearly 45 years of service in the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. ...

is a record for the House. Laurier is best known for his compromises between English

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

** English national ide ...

and French Canada.

Laurier studied law at McGill University

McGill University (french: link=no, Université McGill) is an English-language public research university located in Montreal, Quebec, Canada. Founded in 1821 by royal charter granted by King George IV,Frost, Stanley Brice. ''McGill Universit ...

and practised as a lawyer before being elected to the Legislative Assembly of Quebec

The Legislative Assembly of Quebec (French: ''Assemblée législative du Québec'') was the name of the lower house of Quebec's legislature from 1867 to December 31, 1968, when it was renamed the National Assembly of Quebec. At the same time, t ...

in 1871

Events January–March

* January 3 – Franco-Prussian War – Battle of Bapaume: Prussians win a strategic victory.

* January 18 – Proclamation of the German Empire: The member states of the North German Confederation and the sout ...

. He was then elected as a member of Parliament

A member of parliament (MP) is the representative in parliament of the people who live in their electoral district. In many countries with bicameral parliaments, this term refers only to members of the lower house since upper house members of ...

(MP) in the 1874 federal election. As an MP, Laurier gained a large personal following among French Canadians and the Québécois. He also came to be known as a great orator. After serving as minister of inland revenue

The Minister of Inland Revenue is the political office of Minister for the department of Inland Revenue which is responsible for the collection of taxes. "Minister of Inland Revenue" is a title held by politicians in different countries. the offi ...

under Prime Minister Alexander Mackenzie from 1877 to 1878, Laurier became leader of the Liberal Party

The Liberal Party is any of many political parties around the world. The meaning of ''liberal'' varies around the world, ranging from liberal conservatism on the right to social liberalism on the left.

__TOC__ Active liberal parties

This is a li ...

in 1887, thus becoming leader of the Official Opposition. He lost the 1891 federal election to Prime Minister John A. Macdonald

Sir John Alexander Macdonald (January 10 or 11, 1815 – June 6, 1891) was the first prime minister of Canada, serving from 1867 to 1873 and from 1878 to 1891. The dominant figure of Canadian Confederation, he had a political career that sp ...

's Conservatives

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization in ...

. However, controversy surrounding the Conservative government's handling of the Manitoba Schools Question

The Manitoba Schools Question () was a political crisis in the Canadian province of Province of Manitoba, Manitoba that occurred late in the 19th century, attacking publicly-funded separate schools for Roman Catholics in Canada, Roman Catholics and ...

, which was triggered by the Manitoba

Manitoba ( ) is a Provinces and territories of Canada, province of Canada at the Centre of Canada, longitudinal centre of the country. It is Canada's Population of Canada by province and territory, fifth-most populous province, with a population o ...

government's elimination of funding for Catholic school

Catholic schools are pre-primary, primary and secondary educational institutions administered under the aegis or in association with the Catholic Church. , the Catholic Church operates the world's largest religious, non-governmental school syste ...

s, gave Laurier a victory in the 1896 federal election. He paved the Liberal Party to three more election victories afterwards.

As prime minister, Laurier solved the Manitoba Schools Question by allowing Catholic students to have a Catholic education on a school-by-school basis. Despite his controversial handling of the dispute and criticism from some French Canadians who believed that the resolution was insufficient, he was nicknamed "the Great Conciliator" for offering a compromise between French and English Canada. Two issues, the United Kingdom demanding Canadian military support to fight in the Second Boer War

The Second Boer War ( af, Tweede Vryheidsoorlog, , 11 October 189931 May 1902), also known as the Boer War, the Anglo–Boer War, or the South African War, was a conflict fought between the British Empire and the two Boer Republics (the Sout ...

, and the United Kingdom asking Canada to send money for the British Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

, divided the country as English Canadians supported Britain's requests whereas French Canadians did not. Laurier's government sought a middle ground between the two groups, deciding to send a volunteer force

The Volunteer Force was a citizen army of part-time rifle, artillery and engineer corps, created as a popular movement throughout the British Empire in 1859. Originally highly autonomous, the units of volunteers became increasingly integrated ...

to fight in the Boer War and passing the 1910 ''Naval Service Act

The ''Naval Service Act'' was a statute of the Parliament of Canada, enacted in 1910. The Act was put forward by the Liberal government of Prime Minister Sir Wilfrid Laurier to establish a Canadian navy. Prior to the passage of the Act, Canada ...

'' to create Canada's own navy

A navy, naval force, or maritime force is the branch of a nation's armed forces principally designated for naval warfare, naval and amphibious warfare; namely, lake-borne, riverine, littoral zone, littoral, or ocean-borne combat operations and ...

. In addition, his government dramatically increased immigration

Immigration is the international movement of people to a destination country of which they are not natives or where they do not possess citizenship in order to settle as permanent residents or naturalized citizens. Commuters, tourists, and ...

, oversaw Alberta

Alberta ( ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is part of Western Canada and is one of the three prairie provinces. Alberta is bordered by British Columbia to the west, Saskatchewan to the east, the Northwest Ter ...

and Saskatchewan

Saskatchewan ( ; ) is a Provinces and territories of Canada, province in Western Canada, western Canada, bordered on the west by Alberta, on the north by the Northwest Territories, on the east by Manitoba, to the northeast by Nunavut, and on t ...

's entry into Confederation

A confederation (also known as a confederacy or league) is a union of sovereign groups or states united for purposes of common action. Usually created by a treaty, confederations of states tend to be established for dealing with critical issu ...

, constructed the Grand Trunk Pacific

The Grand Trunk Pacific Railway was a historic Canadian transcontinental railway running from Fort William, Ontario (now Thunder Bay) to Prince Rupert, British Columbia, a Pacific coast port. East of Winnipeg the line continued as the National Tra ...

and National Transcontinental Railways, and put effort into establishing Canada as an autonomous country within the British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts esta ...

.

Laurier's proposed reciprocity

Reciprocity may refer to:

Law and trade

* Reciprocity (Canadian politics), free trade with the United States of America

** Reciprocal trade agreement, entered into in order to reduce (or eliminate) tariffs, quotas and other trade restrictions on ...

agreement with the United States to lower tariffs became a main issue in the 1911 federal election, in which the Liberals were defeated by the Conservatives led by Robert Borden

Sir Robert Laird Borden (June 26, 1854 – June 10, 1937) was a Canadian lawyer and politician who served as the eighth prime minister of Canada from 1911 to 1920. He is best known for his leadership of Canada during World War I.

Borde ...

, who claimed that the treaty would lead to the US influencing Canadian identity. Despite his defeat, Laurier stayed on as Liberal leader and once again became leader of the Opposition. During World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

and the Conscription Crisis of 1917

The Conscription Crisis of 1917 (french: Crise de la conscription de 1917) was a political and military crisis in Canada during World War I. It was mainly caused by disagreement on whether men should be conscripted to fight in the war, but also b ...

, Laurier faced divisions within the Liberal Party as pro-conscription

Conscription (also called the draft in the United States) is the state-mandated enlistment of people in a national service, mainly a military service. Conscription dates back to antiquity and it continues in some countries to the present day un ...

Liberals joined Borden's Unionist government. The anti-conscription faction of the Liberal Party, led by Laurier, became the Laurier Liberals

Prior to the 1917 federal election in Canada, the Liberal Party of Canada split into two factions. To differentiate the groups, historians tend to use two retrospective names:

* The Laurier Liberals, who opposed conscription of soldiers to supp ...

, though the group would be heavily defeated by Borden's Unionists in the 1917 federal election. Laurier remained Opposition leader even after his 1917 defeat, but was not able to fight in another election as he died in 1919. Laurier is ranked

A ranking is a relationship between a set of items such that, for any two items, the first is either "ranked higher than", "ranked lower than" or "ranked equal to" the second.

In mathematics, this is known as a weak order or total preorder of ...

among the top three of Canadian prime ministers. At 31 years and 8 months, Laurier is the longest-serving leader of a major Canadian political party. He is the fourth-longest serving prime minister of Canada, behind Pierre Trudeau

Joseph Philippe Pierre Yves Elliott Trudeau ( , ; October 18, 1919 – September 28, 2000), also referred to by his initials PET, was a Canadian lawyer and politician who served as the 15th prime minister of Canada

The prime mini ...

, Macdonald, and William Lyon Mackenzie King

William Lyon Mackenzie King (December 17, 1874 – July 22, 1950) was a Canadian statesman and politician who served as the tenth prime minister of Canada for three non-consecutive terms from 1921 to 1926, 1926 to 1930, and 1935 to 1948. A Li ...

.

Early life (1841–1871)

Childhood

The second child of Carolus Laurier and Marcelle Martineau, Henri Charles Wilfrid Laurier was born in Saint-Lin,Canada East

Canada East (french: links=no, Canada-Est) was the northeastern portion of the United Province of Canada. Lord Durham's Report investigating the causes of the Upper and Lower Canada Rebellions recommended merging those two colonies. The new ...

(modern-day Saint-Lin-Laurentides, Quebec

Quebec ( ; )According to the Canadian government, ''Québec'' (with the acute accent) is the official name in Canadian French and ''Quebec'' (without the accent) is the province's official name in Canadian English is one of the thirtee ...

), on November 20, 1841. He was a sixth-generation French Canadian

French Canadians (referred to as Canadiens mainly before the twentieth century; french: Canadiens français, ; feminine form: , ), or Franco-Canadians (french: Franco-Canadiens), refers to either an ethnic group who trace their ancestry to Fren ...

. His ancestor François Cottineau, ''dit'' Champlaurier, came to Canada from Saint-Claud

Saint-Claud (; oc, Sent Claud) is a commune in the Charente department in southwestern France.

The small commune is located northeast of Angoulême.

Population

Personalities

The commune is partly the ancestral home of Sir Wilfrid Laurier, P ...

, France. Laurier grew up in a family where politics was a staple of talk and debate. His father, an educated man having liberal ideas, enjoyed a certain degree of prestige about town. In addition to being a farmer and surveyor

Surveying or land surveying is the technique, profession, art, and science of determining the terrestrial two-dimensional or three-dimensional positions of points and the distances and angles between them. A land surveying professional is ca ...

, he also occupied such sought-after positions as mayor, justice of the peace

A justice of the peace (JP) is a judicial officer of a lower or ''puisne'' court, elected or appointed by means of a commission ( letters patent) to keep the peace. In past centuries the term commissioner of the peace was often used with the sa ...

, militia lieutenant and school board

A board of education, school committee or school board is the board of directors or board of trustees of a school, local school district or an equivalent institution.

The elected council determines the educational policy in a small regional are ...

member. At the age of 11, Wilfrid left home to study in New Glasgow, Quebec

New is an adjective referring to something recently made, discovered, or created.

New or NEW may refer to:

Music

* New, singer of K-pop group The Boyz

Albums and EPs

* ''New'' (album), by Paul McCartney, 2013

* ''New'' (EP), by Regurgitator, ...

, a neighbouring village largely inhabited by immigrants from Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a border with England to the southeast and is otherwise surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean to the ...

. Over the next two years, he familiarized himself with the mentality, language and culture of British people, in addition to learning English. In 1854, Laurier attended the Collège de L'Assomption, an institution that staunchly followed Roman Catholicism

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwide . It is am ...

. There, he started to develop an interest in politics, and began to endorse the ideology of liberalism

Liberalism is a political and moral philosophy based on the rights of the individual, liberty, consent of the governed, political equality and equality before the law."political rationalism, hostility to autocracy, cultural distaste for c ...

, despite the school being heavily conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization i ...

.

Political beginnings

In September 1861, Laurier began studying law atMcGill University

McGill University (french: link=no, Université McGill) is an English-language public research university located in Montreal, Quebec, Canada. Founded in 1821 by royal charter granted by King George IV,Frost, Stanley Brice. ''McGill Universit ...

. There, he met Zoé Lafontaine, who would later become his wife. Laurier also discovered that he had chronic bronchitis

Bronchitis is inflammation of the bronchi (large and medium-sized airways) in the lungs that causes coughing. Bronchitis usually begins as an infection in the nose, ears, throat, or sinuses. The infection then makes its way down to the bronchi. ...

, an illness that would stick with him for the rest of his life. At McGill, Laurier joined the Parti Rouge

The Red Party (french: Parti rouge, or french: Parti démocratique) was a political group that contested elections in the Eastern section of the Province of Canada. It was formed around 1847 by radical French-Canadians inspired by the ideas of L ...

, or Red Party, which was a centre-left

Centre-left politics lean to the left on the left–right political spectrum but are closer to the centre than other left-wing politics. Those on the centre-left believe in working within the established systems to improve social justice. The c ...

political party that contested elections in Canada East. In 1864, Laurier graduated from McGill. Laurier would continue being active within the Parti Rouge, and from May 1864 to fall 1866, served as vice president of the Institut canadien de Montréal The Institut canadien de Montréal (English; Canadian Institute of Montreal) was founded on 17 December 1844, by a group of 200 young liberal professionals in Montreal, Canada East, Province of Canada. The Institute provided a public library and d ...

, a literary society with ties to the Rouge. In August 1864, Laurier joined the Liberals of Lower Canada, an anti-Confederation

A confederation (also known as a confederacy or league) is a union of sovereign groups or states united for purposes of common action. Usually created by a treaty, confederations of states tend to be established for dealing with critical issu ...

group composed of both moderates and radicals. The group argued that Confederation would give too much power to the central, or federal government, and the group believed that Confederation would lead to discrimination towards French Canadians.

Laurier then practised law in

Laurier then practised law in Montreal

Montreal ( ; officially Montréal, ) is the List of the largest municipalities in Canada by population, second-most populous city in Canada and List of towns in Quebec, most populous city in the Provinces and territories of Canada, Canadian ...

, though he initially struggled as a lawyer. He opened his first practice on October 27, 1864, but closed it within a month. He established his second office, but that closed within three months, due to a lack of clients. In March 1865, nearly bankrupt, Laurier established his third law firm, partnering with Médéric Lanctot, a lawyer and journalist who staunchly opposed Confederation. The two experienced some success, but in late 1866, Laurier was invited by fellow Rouge Antoine-Aimé Dorion

Sir Antoine-Aimé Dorion (January 17, 1818May 31, 1891) was a French Canadian politician and jurist.

Early years

Dorion was born in Ste-Anne-de-la-Pérade into a family with liberal values that had been sympathetic to the Patriotes in 1837� ...

to replace his recently deceased brother to became editor and run the newspaper, ''Le Défricheur''.

Laurier moved to Victoriaville

Victoriaville is a town in central Quebec, Canada, on the Nicolet River. Victoriaville is the seat of Arthabaska Regional County Municipality and a part of the Centre-du-Québec (Bois-Francs) region. It is formed by the 1993 merger of Arthabask ...

and began writing and controlling the newspaper from January 1, 1867. Laurier saw this as an opportunity to express his strong anti-Confederation views; in one instance he wrote, "Confederation is the second stage on the road to ‘anglification’ mapped out by Lord Durham

Earl of Durham is a title in the Peerage of the United Kingdom. It was created in 1833 for the Whig politician and colonial official John Lambton, 1st Baron Durham. Known as "Radical Jack", he played a leading role in the passing of the Gre ...

...We are being handed over to the English majority...e must

E, or e, is the fifth letter and the second vowel letter in the Latin alphabet, used in the modern English alphabet, the alphabets of other western European languages and others worldwide. Its name in English is ''e'' (pronounced ); plura ...

use whatever influence we have left to demand and obtain a free and separate government." On March 21, ''Le Défricheur'' was forced to shut down, as a result of financial issues and opposition from the local clergy

Clergy are formal leaders within established religions. Their roles and functions vary in different religious traditions, but usually involve presiding over specific rituals and teaching their religion's doctrines and practices. Some of the ter ...

. On July 1, Confederation was officially proclaimed and recognized, a defeat for Laurier.

Laurier decided to remain in Victoriaville. He slowly became well known across the town with a population of 730, and was even elected mayor not so long after he settled. In addition, he established a law practice which would span for three decades and have four different partners. He would make some money, but not enough to consider himself wealthy. During his period in Victoriaville, Laurier opted to accept Confederation and identify himself as a moderate liberal, as opposed to a radical liberal.

Early political career (1871–1887)

Member of the Legislative Assembly of Quebec (1871–1874)

A member of theQuebec Liberal Party

The Quebec Liberal Party (QLP; french: Parti libéral du Québec, PLQ) is a provincial political party in Quebec. It has been independent of the federal Liberal Party of Canada since 1955. The QLP has always been associated with the colour red; e ...

, Laurier was elected to the Legislative Assembly of Quebec

The Legislative Assembly of Quebec (French: ''Assemblée législative du Québec'') was the name of the lower house of Quebec's legislature from 1867 to December 31, 1968, when it was renamed the National Assembly of Quebec. At the same time, t ...

for the riding of Drummond-Arthabaska in the 1871 Quebec general election

The 1871 Quebec general election was held in June and July 1871 to elect members of the Second Legislature for the Province of Quebec, Canada. The Quebec Conservative Party, led by Premier Pierre-Joseph-Olivier Chauveau, was re-elected, defeat ...

, though the Liberal Party altogether suffered a landslide defeat. To win the provincial riding, Laurier campaigned on increasing funding for education, agriculture, and colonization. His career as a provincial politician was not noteworthy, and very few times would he make speeches in the legislature.

Member of Parliament (1874–1887)

Laurier resigned from the provincial legislature to enter federal politics as aLiberal

Liberal or liberalism may refer to:

Politics

* a supporter of liberalism

** Liberalism by country

* an adherent of a Liberal Party

* Liberalism (international relations)

* Sexually liberal feminism

* Social liberalism

Arts, entertainment and m ...

. He was elected to the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. ...

in the January 22, 1874 election, representing the riding of Drummond—Arthabaska

Drummond—Arthabaska was a federal electoral district in Quebec, Canada, that was represented in the House of Commons of Canada from 1867 to 1968.

It was created by the ''British North America Act'', 1867. It was amalgamated into the Richmon ...

. In this election, the Liberals led by Alexander Mackenzie heavily triumphed, as a result of the Pacific Scandal The Pacific Scandal was a political scandal in Canada involving bribes being accepted by 150 members of the Conservative government in the attempts of private interests to influence the bidding for a national rail contract. As part of British Colum ...

that was initiated by the Conservative Party

The Conservative Party is a name used by many political parties around the world. These political parties are generally right-wing though their exact ideologies can range from center-right to far-right.

Political parties called The Conservative P ...

and the Conservative prime minister, John A. Macdonald

Sir John Alexander Macdonald (January 10 or 11, 1815 – June 6, 1891) was the first prime minister of Canada, serving from 1867 to 1873 and from 1878 to 1891. The dominant figure of Canadian Confederation, he had a political career that sp ...

. Laurier ran a simple campaign, denouncing Conservative corruption.

As a

As a member of Parliament

A member of parliament (MP) is the representative in parliament of the people who live in their electoral district. In many countries with bicameral parliaments, this term refers only to members of the lower house since upper house members of ...

(MP), Laurier's first mission was to build prominence by giving speeches in the House of Commons. He gained considerable attention when he delivered a speech on political liberalism on June 26, 1877, in front of about 2,000 people. He stated, "Liberal Catholicism is not political liberalism" and that the Liberal Party is not "a party composed of men holding perverse doctrines, with a dangerous tendency, and knowingly and deliberately progressing towards revolution." He also stated, "The policy of the Liberal party is to protect urinstitutions, to defend them and spread them, and, under the sway of those institutions, to develop the country’s latent resources. That is the policy of the Liberal party and it has no other." The speech helped Laurier become a leader of the Quebec wing of the Liberal Party.

From October 1877 to October 1878, Laurier served briefly in the Cabinet

Cabinet or The Cabinet may refer to:

Furniture

* Cabinetry, a box-shaped piece of furniture with doors and/or drawers

* Display cabinet, a piece of furniture with one or more transparent glass sheets or transparent polycarbonate sheets

* Filing ...

of Prime Minister Mackenzie as minister of inland revenue

The Minister of Inland Revenue is the political office of Minister for the department of Inland Revenue which is responsible for the collection of taxes. "Minister of Inland Revenue" is a title held by politicians in different countries. the offi ...

. However, his appointment triggered an October 27, 1877 ministerial by-election

A ministerial by-election is a by-election to fill a vacancy triggered by the appointment of the sitting member of parliament (MP) as a minister in the cabinet. The requirement for new ministers to stand for re-election was introduced in the Hous ...

. In the by-election, he lost his seat in Drummond—Arthabaska. On November 11, he ran for the seat of Quebec East

Quebec East (also known as Québec-Est and Québec East) was a federal electoral district in Quebec, Canada, that was represented in the House of Commons of Canada from 1867 to 2004.

While its boundaries changed over the decades, it was essenti ...

, which he narrowly won. From November 11, 1877, to his death on February 17, 1919, Laurier's seat would be Quebec East. Laurier won reelection for Quebec East in the 1878 federal election, though the Liberals suffered a landslide defeat as a result of their mishandling of the Panic of 1873

The Panic of 1873 was a financial crisis that triggered an economic depression in Europe and North America that lasted from 1873 to 1877 or 1879 in France and in Britain. In Britain, the Panic started two decades of stagnation known as the "Lon ...

. Macdonald returned as prime minister.

Laurier called on Mackenzie to resign as leader, not least because of his handling of the economy. Mackenzie resigned as Liberal leader in 1880 and was succeeded by Edward Blake

Dominick Edward Blake (October 13, 1833 – March 1, 1912), known as Edward Blake, was the second premier of Ontario, from 1871 to 1872 and leader of the Liberal Party of Canada from 1880 to 1887. He is one of only three federal permanent Li ...

. Laurier, along with others, founded the Quebec newspaper, ''L’Électeur'', to promote the Liberal Party. The Liberals were in opposition once again, and Laurier made use of that status, expressing his support for laissez-faire economics

''Laissez-faire'' ( ; from french: laissez faire , ) is an economic system in which transactions between private groups of people are free from any form of economic interventionism (such as subsidies) deriving from special interest groups. A ...

and provincial rights. The Liberals suffered a second consecutive defeat in 1882

Events

January–March

* January 2

** The Standard Oil Trust is secretly created in the United States to control multiple corporations set up by John D. Rockefeller and his associates.

** Irish-born author Oscar Wilde arrives in ...

, with Macdonald winning his fourth term. Laurier continued to make speeches opposing the Conservative government's policies, though nothing notable came until 1885, when he spoke out against the execution of Métis activist Louis Riel

Louis Riel (; ; 22 October 1844 – 16 November 1885) was a Canadian politician, a founder of the province of Manitoba, and a political leader of the Métis people. He led two resistance movements against the Government of Canada and its first ...

, who was hung by Macdonald's government authorities after leading the North-West Rebellion

The North-West Rebellion (french: Rébellion du Nord-Ouest), also known as the North-West Resistance, was a resistance by the Métis people under Louis Riel and an associated uprising by First Nations Cree and Assiniboine of the District of S ...

.

Leader of the Official Opposition (1887–1896)

Edward Blake resigned as Liberal leader after leading them to back-to-back defeats in 1882 and1887

Events

January–March

* January 11 – Louis Pasteur's anti-rabies treatment is defended in the Académie Nationale de Médecine, by Dr. Joseph Grancher.

* January 20

** The United States Senate allows the Navy to lease Pearl Har ...

. Blake urged Laurier to run for leadership of the party. At first, Laurier refused as he was not keen to take such a powerful position, but later on accepted. After 13 and a half years, Laurier had already established his reputation. He was now a prominent politician who was known for leading the Quebec branch of the Liberal Party, known for defending French Canadian rights, and known for being a great orator who was a fierce parliamentary speaker. Over the next nine years, Laurier gradually built up his party's strength through his personal following both in Quebec and elsewhere in Canada.

In the 1891 federal election, Laurier faced Conservative Prime Minister

In the 1891 federal election, Laurier faced Conservative Prime Minister John A. Macdonald

Sir John Alexander Macdonald (January 10 or 11, 1815 – June 6, 1891) was the first prime minister of Canada, serving from 1867 to 1873 and from 1878 to 1891. The dominant figure of Canadian Confederation, he had a political career that sp ...

. Laurier campaigned in favour of reciprocity

Reciprocity may refer to:

Law and trade

* Reciprocity (Canadian politics), free trade with the United States of America

** Reciprocal trade agreement, entered into in order to reduce (or eliminate) tariffs, quotas and other trade restrictions on ...

, or free trade

Free trade is a trade policy that does not restrict imports or exports. It can also be understood as the free market idea applied to international trade. In government, free trade is predominantly advocated by political parties that hold econo ...

, with the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

, contrary to Macdonald's position on the matter, who claimed that reciprocity would lead to American annexation of Canada. On election day, March 5, the Liberals gained 10 seats. The Liberals also won a majority of seats in Quebec for the first time since the 1874 election. Prime Minister Macdonald won his fourth consecutive federal election victory. The day after, Blake denounced the Liberal trade policy.

Laurier remained disillusioned for some time after his defeat. Multiple times he suggested he resign as leader, though he was persuaded not to by other Liberals. Only in 1893 did Laurier become encouraged again. On June 20 and 21, 1893, Laurier convened a Liberal convention in Ottawa. The convention established that unrestricted reciprocity was intended to develop Canada's natural resources and that keeping a customs tariff was intended to generate revenue. Laurier subsequently undertook a series of speaking tours to campaign on the convention's results. Laurier visited Western Canada

Western Canada, also referred to as the Western provinces, Canadian West or the Western provinces of Canada, and commonly known within Canada as the West, is a Canadian region that includes the four western provinces just north of the Canada� ...

in September and October 1894, promising to relax the Conservatives' National Policy

The National Policy was a Canadian economic program introduced by John A. Macdonald's Conservative Party in 1876. After Macdonald led the Conservatives to victory in the 1878 Canadian federal election, he began implementing his policy in 1879. The ...

, open the American market, and increase immigration

Immigration is the international movement of people to a destination country of which they are not natives or where they do not possess citizenship in order to settle as permanent residents or naturalized citizens. Commuters, tourists, and ...

.

Macdonald died only three months after he defeated Laurier in the 1891 election. After Macdonald's death, the Conservatives went through a period of disorganization with four short-serving leaders. The fourth prime minister after Macdonald, Charles Tupper

Sir Charles Tupper, 1st Baronet, (July 2, 1821 – October 30, 1915) was a Canadian Father of Confederation who served as the sixth prime minister of Canada from May 1 to July 8, 1896. As the premier of Nova Scotia from 1864 to 1867, he led N ...

, became prime minister in May 1896 after Mackenzie Bowell

Sir Mackenzie Bowell (; December 27, 1823 – December 10, 1917) was a Canadian newspaper publisher and politician, who served as the fifth prime minister of Canada, in office from 1894 to 1896.

Bowell was born in Rickinghall, Suffolk, En ...

resigned as a result of a leadership crisis that was triggered by his attempts to offer a compromise for the Manitoba Schools Question

The Manitoba Schools Question () was a political crisis in the Canadian province of Province of Manitoba, Manitoba that occurred late in the 19th century, attacking publicly-funded separate schools for Roman Catholics in Canada, Roman Catholics and ...

, a dispute which emerged after the provincial government ended funding for Catholic schools in 1890. Tupper faced Laurier in the 1896 federal election, in which the schools dispute was a key issue. While Tupper supported overriding the provincial legislation to reinstate funding for the Catholic schools, Laurier was vague when giving his position on the matter, proposing an investigation of the issue first and then conciliation, a method he famously called, "sunny ways". On June 23, Laurier led the Liberals to their first victory in 22 years, despite losing the popular vote. Laurier's win was made possible by his sweep in Quebec.

Prime Minister (1896–1911)

Domestic policy

Manitoba Schools Question

One of Laurier's first acts as prime minister was to implement a solution to the Manitoba Schools Question, which had helped to bring down the Conservative government of Charles Tupper earlier in 1896. The Manitoba legislature had passed a law eliminating public funding for Catholic schooling. Supporters of Catholic schools argued that the new statute was contrary to the provisions of theManitoba Act, 1870

The ''Manitoba Act, 1870'' (french: link=no, Loi de 1870 sur le Manitoba)Originally entitled (until renamed in 1982) ''An Act to amend and continue the Act 32 and 33 Victoria, chapter 3; and to establish and provide for the Government of the Pro ...

, which had a provision relating to school funding, but the courts rejected that argument and held that the new statute was constitutional. The Catholic minority in Manitoba then asked the federal government for support, and eventually, the Conservatives proposed remedial legislation to override Manitoba's legislation. Laurier opposed the remedial legislation on the basis of provincial rights and succeeded in blocking its passage by Parliament. Once elected, Laurier reached a compromise with the provincial premier, Thomas Greenway

Thomas Greenway (March 25, 1838 – October 30, 1908) was a Canadian politician, merchant and farmer. He served as the seventh premier of Manitoba from 1888 to 1900. A Liberal, his ministry formally ended Manitoba's non-partisan government, al ...

. Known as the Laurier-Greenway Compromise, the agreement did not allow separate Catholic schools to be re-established. However, religious instruction (Catholic education) would take place for 30 minutes at the end of each day, if requested by the parents of 10 children in rural areas or 25 in urban areas. Catholic teachers were allowed to be hired in the schools as long as there were at least 40 Catholic students in urban areas or 25 Catholic students in rural areas, and teachers could speak in French (or any other minority language) as long as there were enough Francophone students. This was seen by many as the best possible solution in the circumstances, however, some French Canadians criticized this move as it was done on an individual basis, and did not protect Catholic or French rights in all schools. Laurier called his effort to lessen the tinder in this issue "sunny ways" (french: link=no, voies ensoleillées).

Railway construction

Laurier's government introduced and initiated the idea of constructing a secondtranscontinental railway

A transcontinental railroad or transcontinental railway is contiguous railroad trackage, that crosses a continental land mass and has terminals at different oceans or continental borders. Such networks can be via the tracks of either a single ...

, the Grand Trunk Pacific Railway

The Grand Trunk Pacific Railway was a historic Canadian transcontinental railway running from Fort William, Ontario (now Thunder Bay) to Prince Rupert, British Columbia, a Pacific coast port. East of Winnipeg the line continued as the National Tra ...

. The first transcontinental railway, the Canadian Pacific Railway

The Canadian Pacific Railway (french: Chemin de fer Canadien Pacifique) , also known simply as CPR or Canadian Pacific and formerly as CP Rail (1968–1996), is a Canadian Class I railway incorporated in 1881. The railway is owned by Canadi ...

, had limitations and was not able to meet everyone's needs. In the West

West is a cardinal direction or compass point.

West or The West may also refer to:

Geography and locations

Global context

* The Western world

* Western culture and Western civilization in general

* The Western Bloc, countries allied with NATO ...

, the railway was not able to transport everything produced by farmers and in the East, the railway did not reach into Northern Ontario

Northern Ontario is a primary geographic and quasi-administrative region of the Canadian province of Ontario, the other primary region being Southern Ontario. Most of the core geographic region is located on part of the Superior Geological Provi ...

and Northern Quebec Northern Quebec (french: le nord du Québec) is a geographic term denoting the northerly, more remote and less populated parts of the Canadian province of Quebec.Alexandre Robaey"Charity group works with Indigenous communities to feed Northern Quebe ...

. Laurier was in favour of a transcontinental line built entirely on Canadian land by private enterprise.

Laurier's government also constructed a third railway: the

Laurier's government also constructed a third railway: the National Transcontinental Railway

The National Transcontinental Railway (NTR) was a historic railway between Winnipeg and Moncton in Canada. Much of the line is now operated by the Canadian National Railway.

The Grand Trunk partnership

The completion of construction of Canada's ...

. It was made to provide Western Canada with direct rail connection to the Atlantic

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's five oceans, with an area of about . It covers approximately 20% of Earth's surface and about 29% of its water surface area. It is known to separate the " Old World" of Africa, Europe an ...

ports and to open up and develop Northern Ontario and Northern Quebec. Laurier believed that competition between the three railways would force one of the three, the Canadian Pacific Railway, to lower freight rate

A freight rate (historically and in ship chartering simply freight) is a price at which a certain cargo is delivered from one point to another. The price depends on the form of the cargo, the mode of transport (truck, ship, train, aircraft), the w ...

s and thus please Western shippers who would contribute to the competition between the railways. Laurier initially reached out to Grand Trunk Railway

The Grand Trunk Railway (; french: Grand Tronc) was a railway system that operated in the Canadian provinces of Quebec and Ontario and in the American states of Connecticut, Maine, Michigan, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and Vermont. The rai ...

and Canadian Northern Railway

The Canadian Northern Railway (CNoR) was a historic Canadian transcontinental railway. At its 1923 merger into the Canadian National Railway , the CNoR owned a main line between Quebec City and Vancouver via Ottawa, Winnipeg, and Edmonton.

Mani ...

to build the National Transcontinental railway, but after disagreements emerged between the two companies, Laurier's government opted to build part of the railway itself. However, Laurier's government soon struck a deal with the Grand Trunk Pacific Railway Company (subsidiary of the Grand Trunk Railway Company) to build the western section (from Winnipeg

Winnipeg () is the capital and largest city of the province of Manitoba in Canada. It is centred on the confluence of the Red and Assiniboine rivers, near the longitudinal centre of North America. , Winnipeg had a city population of 749,6 ...

to the Pacific Ocean) while the government would build the eastern section (from Winnipeg to Moncton

Moncton (; ) is the most populous city in the Provinces and territories of Canada, Canadian province of New Brunswick. Situated in the Petitcodiac River Valley, Moncton lies at the geographic centre of the The Maritimes, Maritime Provinces. The ...

). Once completed, Laurier's government would hand over the railway to the company for operation. Laurier's government gained criticism from the public due to the heavy cost to construct the railway.

Provincial and territorial boundaries

On September 1, 1905, through the ''Alberta Act

The ''Alberta Act'' (french: Loi sur l'Alberta), effective September 1, 1905, was the act of the Parliament of Canada that created the province of Alberta. The ''Act'' is similar in nature to the ''Saskatchewan Act'', which established the pro ...

'' and the ''Saskatchewan Act

''The Saskatchewan Act'', S. C. 1905, c. 42. (the ''Act'') is an Act of the Parliament of Canada which established the new province of Saskatchewan, effective September 1, 1905. Its long title is ''An Act to establish and provide for the gove ...

'', Laurier oversaw Alberta

Alberta ( ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is part of Western Canada and is one of the three prairie provinces. Alberta is bordered by British Columbia to the west, Saskatchewan to the east, the Northwest Ter ...

and Saskatchewan

Saskatchewan ( ; ) is a Provinces and territories of Canada, province in Western Canada, western Canada, bordered on the west by Alberta, on the north by the Northwest Territories, on the east by Manitoba, to the northeast by Nunavut, and on t ...

's entry into Confederation

A confederation (also known as a confederacy or league) is a union of sovereign groups or states united for purposes of common action. Usually created by a treaty, confederations of states tend to be established for dealing with critical issu ...

, the last two provinces to be created out of the Northwest Territories

The Northwest Territories (abbreviated ''NT'' or ''NWT''; french: Territoires du Nord-Ouest, formerly ''North-Western Territory'' and ''North-West Territories'' and namely shortened as ''Northwest Territory'') is a federal territory of Canada. ...

. Laurier decided to create two provinces, arguing that one large province would be too difficult to govern. This followed the enactment of the ''Yukon Territory Act'' by the Laurier Government in 1898, separating the Yukon

Yukon (; ; formerly called Yukon Territory and also referred to as the Yukon) is the smallest and westernmost of Canada's three territories. It also is the second-least populated province or territory in Canada, with a population of 43,964 as ...

from the Northwest Territories. Also in 1898, Quebec was enlarged through the ''Quebec Boundary Extension Act''.

Immigration

Laurier's government dramatically increased immigration to grow the economy. Between 1897 and 1914, at least a million immigrants arrived in Canada, and Canada's population increased by 40 percent. Laurier's immigration policy targeted thePrairies

Prairies are ecosystems considered part of the temperate grasslands, savannas, and shrublands biome by ecologists, based on similar temperate climates, moderate rainfall, and a composition of grasses, herbs, and shrubs, rather than trees, as the ...

as he argued that it would increase farming production and benefit the agriculture industry

Intensive agriculture, also known as intensive farming (as opposed to extensive farming), conventional, or industrial agriculture, is a type of agriculture, both of crop plants and of animals, with higher levels of input and output per unit of ag ...

.

The British Columbia electorate was alarmed at the arrival of people they considered "uncivilized" by Canadian standards, and adopted a whites-only policy. Although railways and large companies wanted to hire Asians, labour unions and the public at large stood opposed. Both major parties went along with public opinion, with Laurier taking the lead. Scholars have argued that Laurier acted in terms of his racist views in restricting immigration from China and India, as shown by his support for the Chinese head tax

A poll tax, also known as head tax or capitation, is a tax levied as a fixed sum on every liable individual (typically every adult), without reference to income or resources.

Head taxes were important sources of revenue for many governments fr ...

. In 1900, Laurier raised the Chinese head tax to $100. In 1903, this was further raised to $500, but when a few Chinese did pay the $500, he proposed raising the sum to $1,000. This was not the first time Laurier showed racially charged action, and over the course of his time as a politician, he had a history of racist views and actions. In 1886, Laurier told the House of Commons that it was moral for Canada to take lands from “savage nations” so long as the government paid adequate compensation. Laurier also negotiated a limit to Japanese emigration to Canada, and in 1910 introduced a more restrictive immigration law to reduce Black settlement, at a time when Blacks were fleeing racial terror and racial segregation enforced by Jim Crow laws in the Oklahoma territory.

In August 1911, Laurier approved the Order-in-Council P.C. 1911-1324

Order-in-Council P.C. 1911-1324 was a proposed one-year prohibition of black immigrants entering Canada because, according to the order-in-council, “the Negro race” was “unsuitable to the climate and requirements of Canada.” It was tabled ...

recommended by the minister of the interior

An interior minister (sometimes called a minister of internal affairs or minister of home affairs) is a cabinet official position that is responsible for internal affairs, such as public security, civil registration and identification, emergency ...

, Frank Oliver Frank Oliver may refer to:

*Frank Oliver (American football) (born 1952), American football player

*Frank Oliver (footballer) (1882–?), English footballer

*Frank Oliver (politician) (1853–1933), Canadian politician

*Frank Oliver (rugby union) ( ...

. The order was approved by the cabinet on August 12, 1911. The order was intended to keep out Black Americans escaping segregation in the American south, stating that "the Negro race...is deemed unsuitable to the climate and requirements of Canada." The order was never called upon, as efforts by immigration officials had already reduced the number of Blacks migrating to Canada. The order was cancelled on October 5, 1911, the day before Laurier left office, by cabinet claiming that the minister of the interior was not present at the time of approval.

Social policy

In March 1906, Laurier's government introduced the ''Lord's Day Act'' after being persuaded by the Lord's Day Alliance. The Act became effective on March 1, 1907. It prohibited business transactions from taking place on Sundays; it also restricted Sunday trade, labour, recreation, and newspapers. The Act was supported by organized labour and the French Canadian Catholic hierarchy but was opposed by those who worked in the manufacturing and transportation sectors. It was also opposed by French Canadians due to them believing the federal government was interfering in a provincial matter; the Quebec government passed its own ''Lord’s Day Act'' that came into effect one day before the federal act did. In 1907, Laurier's government passed the ''Industrial Disputes Investigation Act'', which mandated conciliation for employers and workers before any strike in public utilities or mines, but did not make it necessary for the groups to accept the conciliators’ report.Foreign policy

United Kingdom

On June 22, 1897, Laurier attended theDiamond Jubilee of Queen Victoria

The Diamond Jubilee of Queen Victoria was officially celebrated on 22 June 1897 to mark the occasion of the 60th anniversary of Queen Victoria's accession on 20 June 1837. Queen Victoria was the first British monarch ever to celebrate a Diamond ...

, which was the 60th anniversary of her coronation. There, he was knighted, and was given several honours, honorary degrees, and medals. Laurier again visited the United Kingdom in 1902, taking part in the 1902 Colonial Conference

The 1902 Colonial Conference followed the conclusion of the Boer War and was held on the occasion of the coronation of King Edward VII. As with the previous conference, it was called by Secretary of State for the Colonies Joseph Chamberlain who o ...

and the coronation

A coronation is the act of placement or bestowal of a coronation crown, crown upon a monarch's head. The term also generally refers not only to the physical crowning but to the whole ceremony wherein the act of crowning occurs, along with the ...

of King Edward VII

Edward VII (Albert Edward; 9 November 1841 – 6 May 1910) was King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and Emperor of India, from 22 January 1901 until his death in 1910.

The second child and eldest son of Queen Victoria an ...

on 9 August 1902. Laurier also took part in the 1907

Events

January

* January 14 – 1907 Kingston earthquake: A 6.5 Mw earthquake in Kingston, Jamaica, kills between 800 and 1,000.

February

* February 11 – The French warship ''Jean Bart'' sinks off the coast of Morocco. ...

and 1911

A notable ongoing event was the Comparison of the Amundsen and Scott Expeditions, race for the South Pole.

Events January

* January 1 – A decade after federation, the Northern Territory and the Australian Capital Territory ...

Imperial Conferences.

On June 1, 1909, Laurier's government established the Department of External Affairs In many countries, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs is the government department responsible for the state's diplomacy, bilateral, and multilateral relations affairs as well as for providing support for a country's citizens who are abroad. The entit ...

for Canada to take greater control of its foreign policy.

In 1899, the United Kingdom expected military support from Canada, as part of the British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts esta ...

, in the Second Boer War

The Second Boer War ( af, Tweede Vryheidsoorlog, , 11 October 189931 May 1902), also known as the Boer War, the Anglo–Boer War, or the South African War, was a conflict fought between the British Empire and the two Boer Republics (the Sout ...

. Laurier was caught between demands for support for military action from English Canada and a strong opposition from French Canada, which saw the Boer War as an English war. Laurier eventually decided to send a volunteer force, rather than the militia

A militia () is generally an army or some other fighting organization of non-professional soldiers, citizens of a country, or subjects of a state, who may perform military service during a time of need, as opposed to a professional force of r ...

expected by Britain

Britain most often refers to:

* The United Kingdom, a sovereign state in Europe comprising the island of Great Britain, the north-eastern part of the island of Ireland and many smaller islands

* Great Britain, the largest island in the United King ...

. Roughly 7,000 Canadian soldiers participated in the volunteer force. Outspoken French Canadian nationalist and Liberal MP Henri Bourassa

Joseph-Napoléon-Henri Bourassa (; September 1, 1868 – August 31, 1952) was a French Canadian political leader and publisher. In 1899, Bourassa was outspoken against the British government's request for Canada to send a militia to fight fo ...

was an especially vocal opponent of any form of military participation and thus resigned from the Liberal caucus in October 1899.

The naval competition between the United Kingdom and the German Empire

The German Empire (),Herbert Tuttle wrote in September 1881 that the term "Reich" does not literally connote an empire as has been commonly assumed by English-speaking people. The term literally denotes an empire – particularly a hereditary ...

escalated in the early years of the 20th century. The British asked Canada for more money and resources for ship construction, precipitating a heated political division in Canada. Many English Canadians wished to send as much as possible; many French Canadians and those against wished to send nothing. Aiming for compromise, Laurier advanced the ''Naval Service Act

The ''Naval Service Act'' was a statute of the Parliament of Canada, enacted in 1910. The Act was put forward by the Liberal government of Prime Minister Sir Wilfrid Laurier to establish a Canadian navy. Prior to the passage of the Act, Canada ...

'' of 1910 which created the Royal Canadian Navy

The Royal Canadian Navy (RCN; french: Marine royale canadienne, ''MRC'') is the Navy, naval force of Canada. The RCN is one of three environmental commands within the Canadian Armed Forces. As of 2021, the RCN operates 12 frigates, four attack s ...

. The navy would initially consist of five cruiser

A cruiser is a type of warship. Modern cruisers are generally the largest ships in a fleet after aircraft carriers and amphibious assault ships, and can usually perform several roles.

The term "cruiser", which has been in use for several hu ...

s and six destroyer

In naval terminology, a destroyer is a fast, manoeuvrable, long-endurance warship intended to escort

larger vessels in a fleet, convoy or battle group and defend them against powerful short range attackers. They were originally developed in ...

s; in times of crisis, it could be made subordinate to the British Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

. However, the idea faced opposition in both English and French Canada, especially in Quebec as ex-Liberal and staunch French Canadian nationalist Henri Bourassa organized an anti-Laurier force.

Alaska boundary dispute

In 1897 and 1898, theAlaska

Alaska ( ; russian: Аляска, Alyaska; ale, Alax̂sxax̂; ; ems, Alas'kaaq; Yup'ik: ''Alaskaq''; tli, Anáaski) is a state located in the Western United States on the northwest extremity of North America. A semi-exclave of the U.S., ...

-Canada border emerged as a pressing issue. The Klondike Gold Rush prompted Laurier to demand an all-Canadian route from the gold fields to a seaport. The region being a desirable place with lots of gold furthered Laurier's ambition of fixing an exact boundary. Laurier also wanted to establish who owned the Lynn Canal

Lynn Canal is an inlet (not an artificial canal) into the mainland of southeast Alaska.

Lynn Canal runs about from the inlets of the Chilkat River south to Chatham Strait and Stephens Passage. At over in depth, Lynn Canal is the deepest fjord ...

and who controlled maritime access to the Yukon. Laurier and US President William McKinley

William McKinley (January 29, 1843September 14, 1901) was the 25th president of the United States, serving from 1897 until his assassination in 1901. As a politician he led a realignment that made his Republican Party largely dominant in ...

agreed to set up a joint Anglo-American commission that would study the differences and resolve the dispute. However, this commission was unsuccessful and came to an abrupt end on February 20, 1899.

The dispute was then referred to an international judicial commission in 1903, which included three American politicians (Elihu Root

Elihu Root (; February 15, 1845February 7, 1937) was an American lawyer, Republican politician, and statesman who served as Secretary of State and Secretary of War in the early twentieth century. He also served as United States Senator from N ...

, Henry Cabot Lodge

Henry Cabot Lodge (May 12, 1850 November 9, 1924) was an American Republican politician, historian, and statesman from Massachusetts. He served in the United States Senate from 1893 to 1924 and is best known for his positions on foreign policy. ...

, and George Turner), two Canadians ( Allen Bristol Aylesworth and Louis-Amable Jetté

Sir Louis-Amable Jetté, (; 15 January 1836 – 5 May 1920) was a Canadian lawyer, politician, judge, professor, and the eighth Lieutenant Governor of Quebec. He was born in L'Assomption, Lower Canada (now Quebec) in 1836.

In 1872, he was ...

) and one Briton (Lord Alverstone

Richard Everard Webster, 1st Viscount Alverstone, (22 December 1842 – 15 December 1915) was a British barrister, politician and judge who served in many high political and judicial offices.

Background and education

Webster was the second son ...

, Lord Chief Justice of England

Lord is an appellation for a person or deity who has authority, control, or power over others, acting as a master, chief, or ruler. The appellation can also denote certain persons who hold a title of the peerage in the United Kingdom, or a ...

). On October 20, 1903, the commission by a majority (Root, Lodge, Turner, and Alverstone) ruled to support the American government's claims. Canada only acquired two islands below the Portland Canal

, image = Hyder Alaska IMG 0276 (22495379342).jpg

, alt =

, caption = Portland Canal from Hyder, Alaska

, image_bathymetry =

, alt_bathymetry =

, caption_bathymetry =

, location = Alaska and British Columbia

, group =

, coordinates ...

. The decision provoked a wave of anti-American and anti-British sentiment in Canada, which Laurier temporarily encouraged.

Tariffs and trade

Though supportive offree trade

Free trade is a trade policy that does not restrict imports or exports. It can also be understood as the free market idea applied to international trade. In government, free trade is predominantly advocated by political parties that hold econo ...

with the United States, Laurier did not pursue the idea because the American government refused to discuss the issue. Instead, he implemented a Liberal version of the Conservatives' nationalist and protectionist National Policy

The National Policy was a Canadian economic program introduced by John A. Macdonald's Conservative Party in 1876. After Macdonald led the Conservatives to victory in the 1878 Canadian federal election, he began implementing his policy in 1879. The ...

by maintaining high tariffs on goods from other countries that restricted Canadian goods. However, he lowered tariffs to the same level as countries that admitted Canadian goods.

In 1897, Laurier's government impelemented a preferential reduction of a tariff rate of 12.5 percent for countries that imported Canadian goods at a rate equivalent to the minimum Canadian charge; rates for countries that imposed a protective duty against Canada remained the same. For the most part, the policy was supported by those for free trade (due to the preferential reduction) and those against free trade (due to elements of the National Policy remaining in place).

Laurier's government again reformed tariffs in 1907. His government introduced a "three-column tariff", which added a new intermediate rate (a bargaining rate) alongside the existing British preferential rate and the general rate (which applied to all countries that Canada had no most-favoured-nation agreement with). The preferential and general rates remained unchanged, while the intermediate rates were slightly lower than the general rates.

Also in 1907, Laurier's minister of finance

A finance minister is an executive or cabinet position in charge of one or more of government finances, economic policy and financial regulation.

A finance minister's portfolio has a large variety of names around the world, such as "treasury", " ...

, William Stevens Fielding

William Stevens Fielding, (November 24, 1848 – June 23, 1929) was a Canadian Liberal politician, the seventh premier of Nova Scotia (1884–96), and the federal Minister of Finance from 1896 to 1911 and again from 1921 to 1925.

Early life

...

, and minister of marine and fisheries

The minister of fisheries, oceans and the Canadian Coast Guard () is the minister of the Crown in the Canadian Cabinet responsible for supervising the fishing industry, administrating all navigable waterways in the country, and overseeing the o ...

, Louis-Philippe Brodeur

Louis-Philippe Brodeur, baptised Louis-Joseph-Alexandre Brodeur (August 21, 1862 – January 2, 1924) was a Canadian journalist, lawyer, politician, federal Cabinet minister, Speaker of the House of Commons of Canada, and puisne justice o ...

, negotiated a trade agreement with France which lowered import duties on some goods. In 1909, Fielding negotiated an agreement to promote trade with the British West Indies

The British West Indies (BWI) were colonized British territories in the West Indies: Anguilla, the Cayman Islands, Turks and Caicos Islands, Montserrat, the British Virgin Islands, Antigua and Barbuda, The Bahamas, Barbados, Dominica, Grena ...

.

Election victories

Laurier led the Liberals to three re-elections in1900

As of March 1 ( O.S. February 17), when the Julian calendar acknowledged a leap day and the Gregorian calendar did not, the Julian calendar fell one day further behind, bringing the difference to 13 days until February 28 ( O.S. February 15), 2 ...

, 1904

Events

January

* January 7 – The distress signal ''CQD'' is established, only to be replaced 2 years later by ''SOS''.

* January 8 – The Blackstone Library is dedicated, marking the beginning of the Chicago Public Library system.

* ...

, and 1908

Events

January

* January 1 – The British ''Nimrod'' Expedition led by Ernest Shackleton sets sail from New Zealand on the ''Nimrod'' for Antarctica.

* January 3 – A total solar eclipse is visible in the Pacific Ocean, and is the 46 ...

. In the 1900 and 1904 elections, the Liberals' popular vote and seat share kept increasing whereas in the 1908 election, their popular vote and seat share went slightly down.

Quebec stronghold

By the late 1900s, Laurier had been able to build the Liberal Party a base in Quebec, which had remained a Conservative stronghold for decades due to the province's social conservatism and to the influence of theRoman Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

, which distrusted the Liberals' anti-clericalism

Anti-clericalism is opposition to religious authority, typically in social or political matters. Historical anti-clericalism has mainly been opposed to the influence of Roman Catholicism. Anti-clericalism is related to secularism, which seeks to ...

. The growing alienation of French Canadians

French Canadians (referred to as Canadiens mainly before the twentieth century; french: Canadiens français, ; feminine form: , ), or Franco-Canadians (french: Franco-Canadiens), refers to either an ethnic group who trace their ancestry to Fren ...

from the Conservative Party due to its links with anti-French, anti-Catholic Orangemen

Orangemen or Orangewomen can refer to:

*Historically, supporters of William of Orange

*Members of the modern Orange Order (also known as Orange Institution), a Protestant fraternal organisation

*Members or supporters of the Armagh GAA Gaelic foot ...

in English Canada aided the Liberal Party. These factors, combined with the collapse of the Conservative Party of Quebec

The Conservative Party of Quebec (CPQ; french: Parti conservateur du Québec (PCQ)) is a provincial political party in Quebec, Canada. It was authorized on 25 March 2009 by the Chief Electoral Officer of Quebec. The CPQ has gradually run more c ...

, gave Laurier an opportunity to build a stronghold in French Canada and among Catholics across Canada. However, Catholic priests in Quebec repeatedly warned their parishioners not to vote for Liberals. Their slogan was "" ("heaven is blue, hell is red", referring to the Conservative and Liberal parties' traditional colours).

Reciprocity and defeat

In 1911, controversy arose regarding Laurier's support of tradereciprocity

Reciprocity may refer to:

Law and trade

* Reciprocity (Canadian politics), free trade with the United States of America

** Reciprocal trade agreement, entered into in order to reduce (or eliminate) tariffs, quotas and other trade restrictions on ...

with the United States. His long-serving minister of finance, William Stevens Fielding

William Stevens Fielding, (November 24, 1848 – June 23, 1929) was a Canadian Liberal politician, the seventh premier of Nova Scotia (1884–96), and the federal Minister of Finance from 1896 to 1911 and again from 1921 to 1925.

Early life

...

, reached an agreement allowing for the free trade of natural products. The agreement would also lower tariff

A tariff is a tax imposed by the government of a country or by a supranational union on imports or exports of goods. Besides being a source of revenue for the government, import duties can also be a form of regulation of foreign trade and poli ...

s. This had the strong support of agricultural interests, particularly in Western Canada, but it alienated many businessmen who formed a significant part of the Liberal base. The Conservatives

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization in ...

denounced the deal and played on long-standing fears that reciprocity could eventually lead to weakened ties with Britain and a Canadian economy dominated by the United States. They also campaigned on fears that this would lead to the Canadian identity being taken away by the US and the American annexation of Canada.

Contending with an unruly House of Commons, including vocal disapproval from Liberal MP Clifford Sifton

Sir Clifford Sifton, (March 10, 1861 – April 17, 1929), was a Canadian lawyer and a long-time Liberal politician, best known for being Minister of the Interior under Sir Wilfrid Laurier. He was responsible for encouraging the massive amount o ...

, Laurier called an election to settle the issue of reciprocity. The Conservatives were victorious and the Liberals lost over a third of their seats. The Conservatives' leader, Robert Laird Borden

Sir Robert Laird Borden (June 26, 1854 – June 10, 1937) was a Canadian lawyer and politician who served as the eighth prime minister of Canada from 1911 to 1920. He is best known for his leadership of Canada during World War I.

Borde ...

, succeeded Laurier as prime minister. Over 15 consecutive years of Liberal rule ended.

Opposition and war (1911–1919)

Laurier stayed on as Liberal leader. In December 1912, he started leading the filibuster and fight against the Conservatives' own naval bill which would have sent $35 million directly to the British Navy. Laurier argued that this threatened Canadian autonomy. After six months of battling the bill, the bill was blocked by the Liberal-controlled

Laurier stayed on as Liberal leader. In December 1912, he started leading the filibuster and fight against the Conservatives' own naval bill which would have sent $35 million directly to the British Navy. Laurier argued that this threatened Canadian autonomy. After six months of battling the bill, the bill was blocked by the Liberal-controlled Senate

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the el ...

.

Laurier led the opposition during World War I