The history of England during the Late Middle Ages covers from the thirteenth century, the end of the

Angevins, and the accession of

Henry III – considered by many to mark the start of the

Plantagenet

The House of Plantagenet () was a royal house which originated from the lands of Anjou in France. The family held the English throne from 1154 (with the accession of Henry II at the end of the Anarchy) to 1485, when Richard III died in batt ...

dynasty – until the accession to the throne of the

Tudor dynasty

The House of Tudor was a royal house of largely Welsh and English origin that held the English throne from 1485 to 1603. They descended from the Tudors of Penmynydd and Catherine of France. Tudor monarchs ruled the Kingdom of England and it ...

in 1485, which is often taken as the most convenient marker for the end of the

Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire a ...

and the start of the

English Renaissance

The English Renaissance was a Cultural movement, cultural and Art movement, artistic movement in England from the early 16th century to the early 17th century. It is associated with the pan-European Renaissance that is usually regarded as beginni ...

and

early modern Britain

Early modern Britain is the history of the island of Great Britain roughly corresponding to the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries. Major historical events in early modern British history include numerous wars, especially with France, along with the E ...

.

At the accession of

Henry III only a remnant of English holdings remained in

Gascony

Gascony (; french: Gascogne ; oc, Gasconha ; eu, Gaskoinia) was a province of the southwestern Kingdom of France that succeeded the Duchy of Gascony (602–1453). From the 17th century until the French Revolution (1789–1799), it was part o ...

, for which English kings had to pay

homage

Homage (Old English) or Hommage (French) may refer to:

History

*Homage (feudal) /ˈhɒmɪdʒ/, the medieval oath of allegiance

*Commendation ceremony, medieval homage ceremony Arts

*Homage (arts) /oʊˈmɑʒ/, an allusion or imitation by one arti ...

to the French, and the barons were in revolt. Royal authority was restored by his son who inherited the throne in 1272 as

Edward I

Edward I (17/18 June 1239 – 7 July 1307), also known as Edward Longshanks and the Hammer of the Scots, was King of England and Lord of Ireland from 1272 to 1307. Concurrently, he ruled the duchies of Aquitaine and Gascony as a vassal o ...

. He reorganized his possessions, and gained control of Wales and most of Scotland. His son

Edward II

Edward II (25 April 1284 – 21 September 1327), also called Edward of Caernarfon, was King of England and Lord of Ireland from 1307 until he was deposed in January 1327. The fourth son of Edward I, Edward became the heir apparent to t ...

was defeated at the

Battle of Bannockburn

The Battle of Bannockburn ( gd, Blàr Allt nam Bànag or ) fought on June 23–24, 1314, was a victory of the army of King of Scots Robert the Bruce over the army of King Edward II of England in the First War of Scottish Independence. It was ...

in 1314 and lost control of Scotland. He was eventually deposed in a coup and from 1330 his son

Edward III

Edward III (13 November 1312 – 21 June 1377), also known as Edward of Windsor before his accession, was King of England and Lord of Ireland from January 1327 until his death in 1377. He is noted for his military success and for restoring r ...

took control of the kingdom. Disputes over the status of Gascony led Edward III to

lay claim to the

French throne

France was ruled by Monarch, monarchs from the establishment of the West Francia, Kingdom of West Francia in 843 until the end of the Second French Empire in 1870, with several interruptions.

Classical French historiography usually regards Cl ...

, resulting in the

Hundred Years' War

The Hundred Years' War (; 1337–1453) was a series of armed conflicts between the kingdoms of Kingdom of England, England and Kingdom of France, France during the Late Middle Ages. It originated from disputed claims to the French Crown, ...

, in which the English enjoyed success, before a French resurgence during the reign of Edward III's grandson

Richard II

Richard II (6 January 1367 – ), also known as Richard of Bordeaux, was King of England from 1377 until he was deposed in 1399. He was the son of Edward the Black Prince, Prince of Wales, and Joan, Countess of Kent. Richard's father died ...

.

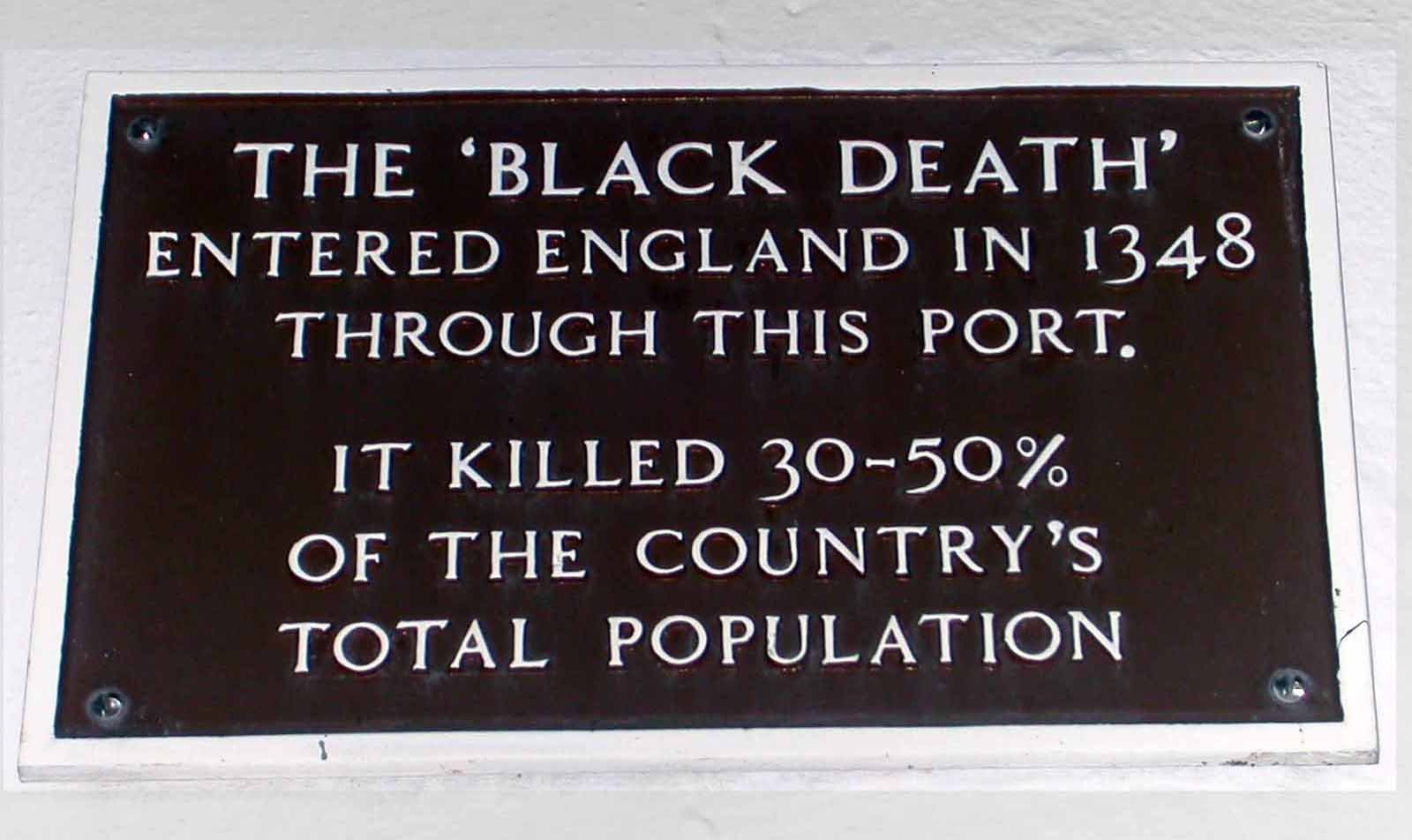

The fourteenth century saw the

Great Famine and the

Black Death

The Black Death (also known as the Pestilence, the Great Mortality or the Plague) was a bubonic plague pandemic occurring in Western Eurasia and North Africa from 1346 to 1353. It is the most fatal pandemic recorded in human history, causi ...

, catastrophic events that killed around half of England's population, throwing the economy into chaos and undermining the old political order. With a shortage of farm labour, much of England's arable land was converted to pasture, mainly for sheep. Social unrest followed in the

Peasants' Revolt

The Peasants' Revolt, also named Wat Tyler's Rebellion or the Great Rising, was a major uprising across large parts of England in 1381. The revolt had various causes, including the socio-economic and political tensions generated by the Black ...

of 1381.

Richard was deposed by

Henry of Bolingbroke

Henry IV ( April 1367 – 20 March 1413), also known as Henry Bolingbroke, was King of England from 1399 to 1413. He asserted the claim of his grandfather King Edward III, a maternal grandson of Philip IV of France, to the Kingdom of Fran ...

in 1399, who as Henry IV founded the

House of Lancaster

The House of Lancaster was a cadet branch of the royal House of Plantagenet. The first house was created when King Henry III of England created the Earldom of Lancasterfrom which the house was namedfor his second son Edmund Crouchback in 126 ...

and reopened the war with France. His son

Henry V Henry V may refer to:

People

* Henry V, Duke of Bavaria (died 1026)

* Henry V, Holy Roman Emperor (1081/86–1125)

* Henry V, Duke of Carinthia (died 1161)

* Henry V, Count Palatine of the Rhine (c. 1173–1227)

* Henry V, Count of Luxembourg (121 ...

won a decisive victory at

Agincourt in 1415, reconquered Normandy and ensured that his infant son

Henry VI would

inherit both English and French crowns after his unexpected death in 1421. However, the French enjoyed another resurgence and by 1453 the English had lost almost all their French holdings. Henry VI proved a weak king and was eventually deposed in the

Wars of the Roses

The Wars of the Roses (1455–1487), known at the time and for more than a century after as the Civil Wars, were a series of civil wars fought over control of the English throne in the mid-to-late fifteenth century. These wars were fought bet ...

, with

Edward IV

Edward IV (28 April 1442 – 9 April 1483) was King of England from 4 March 1461 to 3 October 1470, then again from 11 April 1471 until his death in 1483. He was a central figure in the Wars of the Roses, a series of civil wars in England ...

taking the throne as the first ruling member of the

House of York

The House of York was a cadet branch of the English royal House of Plantagenet. Three of its members became kings of England in the late 15th century. The House of York descended in the male line from Edmund of Langley, 1st Duke of York, ...

. After his death and the taking of the throne by his brother as

Richard III

Richard III (2 October 145222 August 1485) was King of England and Lord of Ireland from 26 June 1483 until his death in 1485. He was the last king of the House of York and the last of the Plantagenet dynasty. His defeat and death at the Battl ...

, an invasion led by

Henry Tudor and his victory in 1485 at the

Battle of Bosworth Field

The Battle of Bosworth or Bosworth Field was the last significant battle of the Wars of the Roses, the civil war between the houses of Lancaster and York that extended across England in the latter half of the 15th century. Fought on 22 Augu ...

marked the end of the Plantagenet dynasty.

English government went through periods of reform and decay, with the

Parliament of England

The Parliament of England was the legislature of the Kingdom of England from the 13th century until 1707 when it was replaced by the Parliament of Great Britain. Parliament evolved from the great council of bishops and peers that advised t ...

emerging as an important part of the administration. Women had an important economic role, and noblewomen exercised power on their estates in their husbands' absence. The English began to see themselves as superior to their neighbours in the

British Isles

The British Isles are a group of islands in the North Atlantic Ocean off the north-western coast of continental Europe, consisting of the islands of Great Britain, Ireland, the Isle of Man, the Inner and Outer Hebrides, the Northern Isles, ...

and regional identities continued to be significant. New reformed monastic orders and preaching orders reached England from the twelfth century, pilgrimage became highly popular and

Lollardy

Lollardy, also known as Lollardism or the Lollard movement, was a proto-Protestant Christian religious movement that existed from the mid-14th century until the 16th-century English Reformation. It was initially led by John Wycliffe, a Catholic ...

emerged as a major heresy from the later fourteenth century. The

Little Ice Age

The Little Ice Age (LIA) was a period of regional cooling, particularly pronounced in the North Atlantic region. It was not a true ice age of global extent. The term was introduced into scientific literature by François E. Matthes in 1939. Ma ...

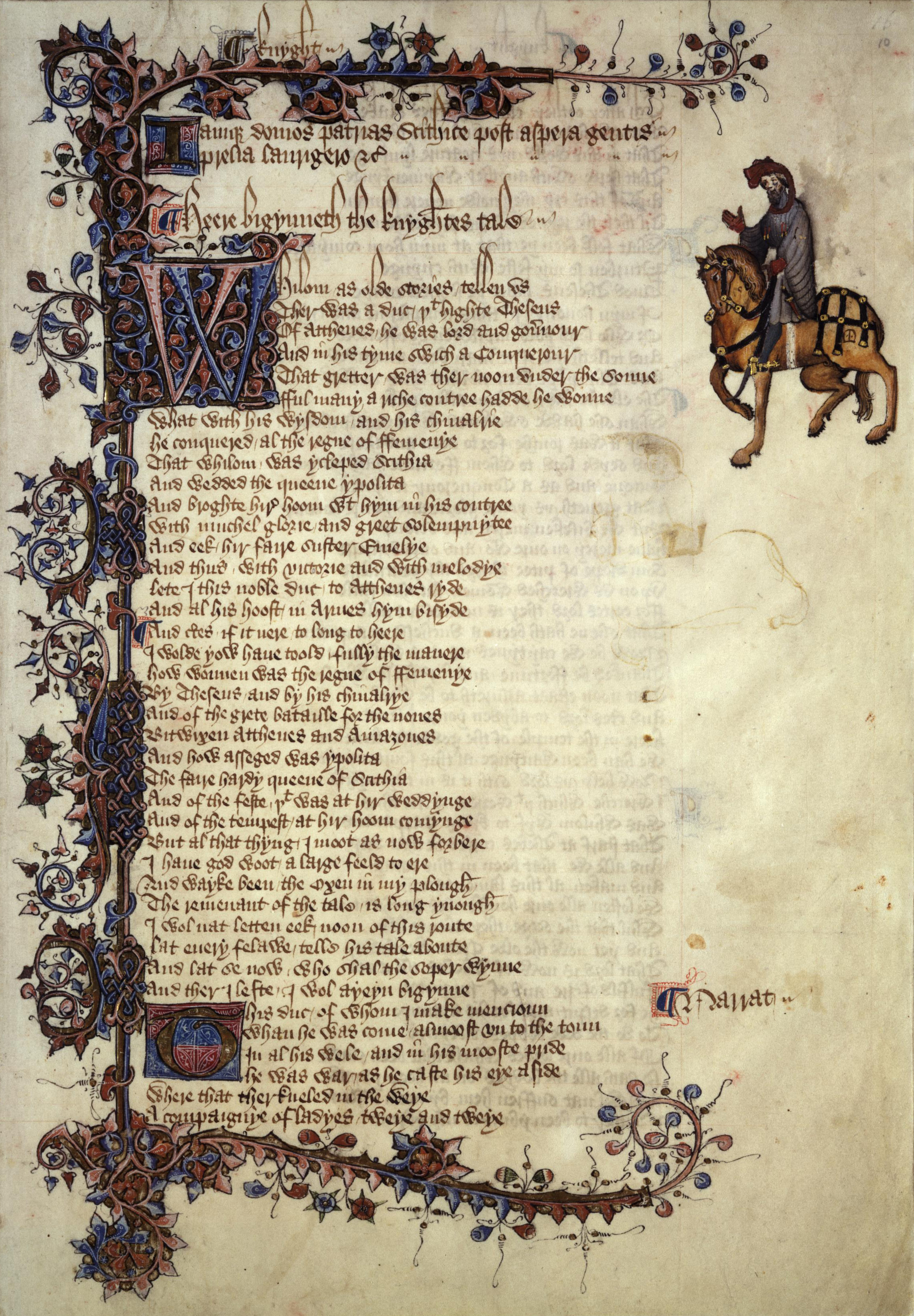

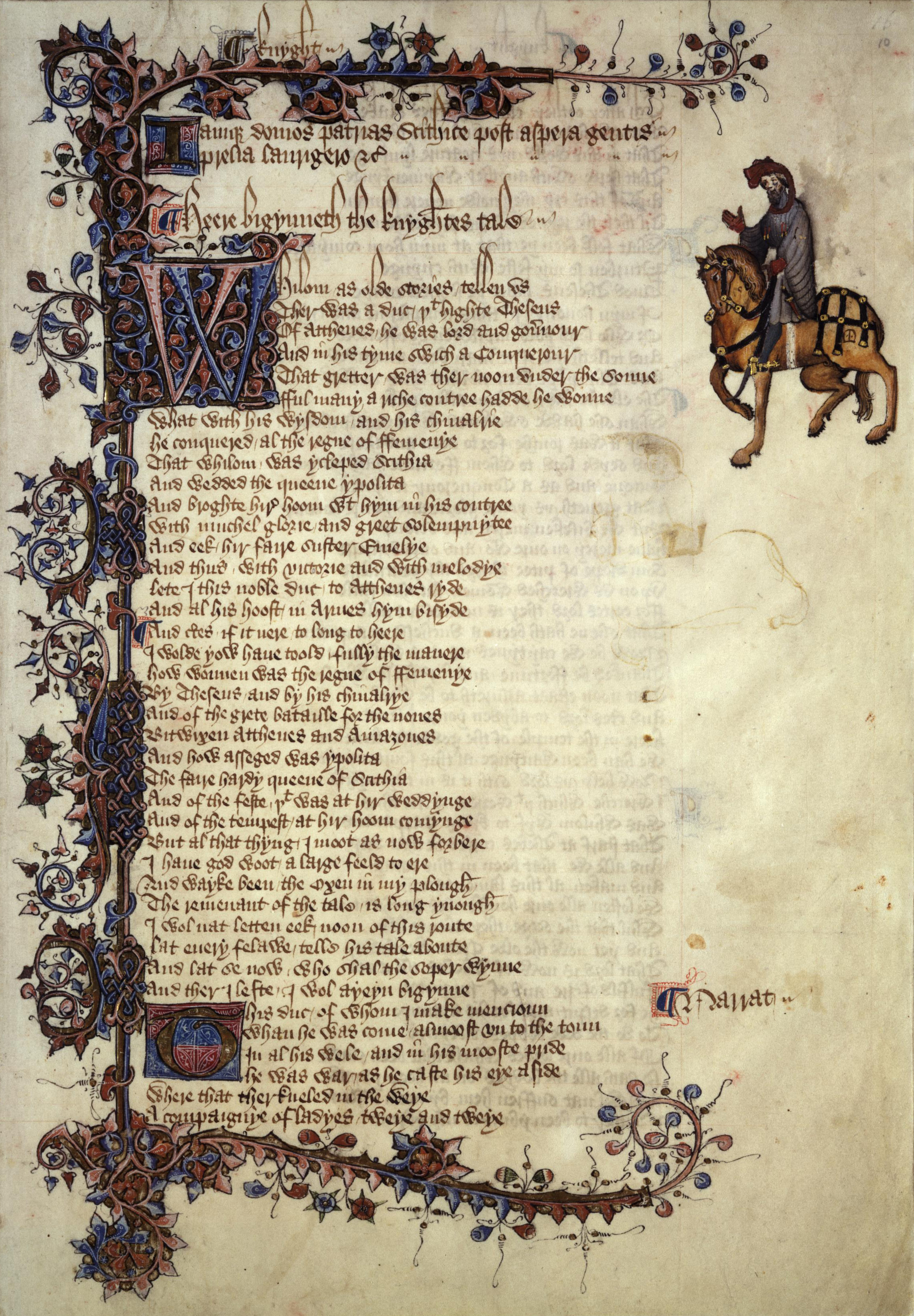

had a significant impact on agriculture and living conditions. Economic growth began to falter at the end of the thirteenth century, owing to a combination of overpopulation, land shortages and depleted soils. Technology and science was driven in part by the Greek and Islamic thinking that reached England from the twelfth century. In warfare, mercenaries were increasingly employed and adequate supplies of ready cash became essential for the success of campaigns. By the time of Edward III, armies were smaller, but the troops were better equipped and uniformed. Medieval England produced art in the form of paintings, carvings, books, fabrics and many functional but beautiful objects. Literature was produced in Latin and French. From the reign of Richard II there was an upsurge in the use of

Middle English

Middle English (abbreviated to ME) is a form of the English language that was spoken after the Norman conquest of 1066, until the late 15th century. The English language underwent distinct variations and developments following the Old English p ...

in poetry. Music and singing were important and were used in religious ceremonies, court occasions and to accompany theatrical works. During the twelfth century the style of

Norman architecture

The term Norman architecture is used to categorise styles of Romanesque architecture developed by the Normans in the various lands under their dominion or influence in the 11th and 12th centuries. In particular the term is traditionally used fo ...

became more ornate, with pointed arches derived from France, termed

Early English Gothic

English Gothic is an architectural style that flourished from the late 12th until the mid-17th century. The style was most prominently used in the construction of cathedrals and churches. Gothic architecture's defining features are pointed ar ...

.

Political history

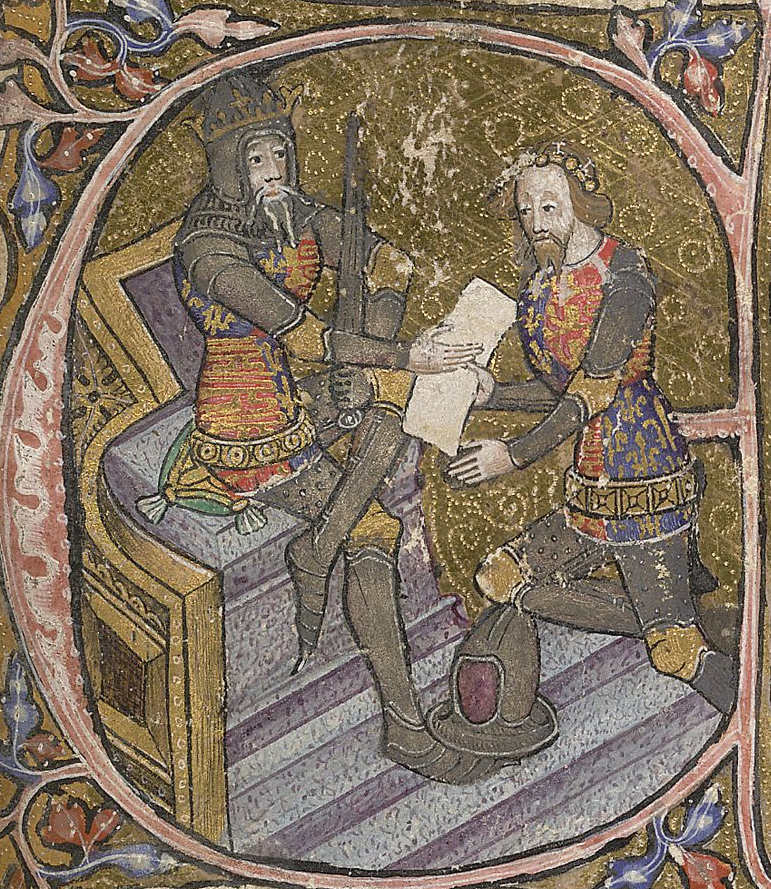

House of Plantagenet

Background

Geoffrey Plantagenet, Count of Anjou

Geoffrey V (24 August 1113 – 7 September 1151), called the Handsome, the Fair (french: link=no, le Bel) or Plantagenet, was the count of Anjou, Count of Tours, Touraine and Count of Maine, Maine by inheritance from 1129, and also Duke of Nor ...

's marriage to the

Empress Matilda

Empress Matilda ( 7 February 110210 September 1167), also known as the Empress Maude, was one of the claimants to the English throne during the civil war known as the Anarchy. The daughter of King Henry I of England, she moved to Germany as ...

meant that he gained control of England and Normandy by 1154, and the marriage of Geoffrey's son

Henry Curtmantle, to

Eleanor of Aquitaine

Eleanor ( – 1 April 1204; french: Aliénor d'Aquitaine, ) was Queen of France from 1137 to 1152 as the wife of King Louis VII, Queen of England from 1154 to 1189 as the wife of King Henry II, and Duchess of Aquitaine in her own right from ...

expanded the family's holdings into what was later termed the

Angevin Empire

The Angevin Empire (; french: Empire Plantagenêt) describes the possessions of the House of Plantagenet during the 12th and 13th centuries, when they ruled over an area covering roughly half of France, all of England, and parts of Ireland and W ...

. As Henry II he consolidated his holdings and acquired nominal control of Wales and Ireland. His son

Richard I

Richard I (8 September 1157 – 6 April 1199) was King of England from 1189 until his death in 1199. He also ruled as Duke of Normandy, Aquitaine and Gascony, Lord of Cyprus, and Count of Poitiers, Anjou, Maine, and Nantes, and was overl ...

was a largely absentee English king, concerned more with the crusades and his holdings in France. His brother

John

John is a common English name and surname:

* John (given name)

* John (surname)

John may also refer to:

New Testament

Works

* Gospel of John, a title often shortened to John

* First Epistle of John, often shortened to 1 John

* Second ...

's defeats in France weakened his position in England. The rebellion of his English vassals resulted in the treaty called

Magna Carta

(Medieval Latin for "Great Charter of Freedoms"), commonly called (also ''Magna Charta''; "Great Charter"), is a royal charter of rights agreed to by King John of England at Runnymede, near Windsor, on 15 June 1215. First drafted by the ...

, which limited royal power and established

common law

In law, common law (also known as judicial precedent, judge-made law, or case law) is the body of law created by judges and similar quasi-judicial tribunals by virtue of being stated in written opinions."The common law is not a brooding omnipresen ...

. This would form the basis of every constitutional battle through the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries. However, both the barons and the crown failed to abide by the terms of Magna Carta, leading to the

First Barons' War

The First Barons' War (1215–1217) was a civil war in the Kingdom of England in which a group of rebellious major landowners (commonly referred to as barons) led by Robert Fitzwalter waged war against King John of England. The conflict resulte ...

in which the rebel barons invited an invasion by

Prince Louis. John's death and

William Marshal

William Marshal, 1st Earl of Pembroke (1146 or 1147 – 14 May 1219), also called William the Marshal (Norman French: ', French: '), was an Anglo-Norman soldier and statesman. He served five English kings— Henry II, his sons the "Young King" ...

l's appointment as the protector of the nine-year-old

Henry III are considered by some historians to mark the end of the Angevin period and the beginning of the Plantagenet dynasty.

Henry III (1216–72)

When Henry III came to the throne in 1216, much of his holdings on the continent were occupied by the French and many of the barons were in rebellion as part of the

First Barons' War

The First Barons' War (1215–1217) was a civil war in the Kingdom of England in which a group of rebellious major landowners (commonly referred to as barons) led by Robert Fitzwalter waged war against King John of England. The conflict resulte ...

. Marshall won the war with victories at the battles of

Lincoln

Lincoln most commonly refers to:

* Abraham Lincoln (1809–1865), the sixteenth president of the United States

* Lincoln, England, cathedral city and county town of Lincolnshire, England

* Lincoln, Nebraska, the capital of Nebraska, U.S.

* Lincoln ...

and

Dover

Dover () is a town and major ferry port in Kent, South East England. It faces France across the Strait of Dover, the narrowest part of the English Channel at from Cap Gris Nez in France. It lies south-east of Canterbury and east of Maidstone ...

in 1217, leading to the

Treaty of Lambeth

The Treaty of Lambeth of 1217, also known as the Treaty of Kingston to distinguish it from the Treaty of Lambeth of 1212, was a peace treaty signed by Louis of France in September 1217 ending the campaign known as the First Barons' War to uphold ...

by which Louis renounced his claims.

In victory, the Marshal Protectorate reissued the ''Magna Carta'' agreement as a basis for future government.

Despite the treaty hostilities continued and Henry was forced to make significant constitutional concessions to the newly crowned Louis VIII of France and Henry's stepfather

Hugh X of Lusignan

Hugh X de Lusignan, Hugh V of La Marche or Hugh I of Angoulême (c. 1183 – c. 5 June 1249, Angoulême) was Seigneur de Lusignan and Count of La Marche in November 1219 and was Count of Angoulême by marriage. He was the son of Hugh IX an ...

. Between them, they overran much of the remnants of Henry's continental holdings, further eroding the Plantagenet grip on the continent. Henry saw such similarities between himself and England's then patron saint

Edward the Confessor

Edward the Confessor ; la, Eduardus Confessor , ; ( 1003 – 5 January 1066) was one of the last Anglo-Saxon English kings. Usually considered the last king of the House of Wessex, he ruled from 1042 to 1066.

Edward was the son of Æth ...

in his struggle with his nobles

that he gave his first son the Anglo-Saxon name Edward and built the saint a magnificent, still-extant shrine at

Westminster

Westminster is an area of Central London, part of the wider City of Westminster.

The area, which extends from the River Thames to Oxford Street, has many visitor attractions and historic landmarks, including the Palace of Westminster, Bu ...

.

The barons were resistant to the cost in men and money required to support a war to restore Plantagenet holdings on the continent. In order to motivate his barons, Henry III reissued Magna Carta and the

Charter of the Forest

The Charter of the Forest of 1217 ( la, Carta Foresta) is a charter that re-established for free men rights of access to the royal forest that had been eroded by King William the Conqueror and his heirs. Many of its provisions were in force for ...

in return for a tax that raised the huge sum of £45,000. This was enacted in an assembly of the barons, bishops and magnates that created a compact in which the feudal prerogatives of the king were debated and discussed in the political community.

Henry was forced to agree to the

Provisions of Oxford

The Provisions of Oxford were constitutional reforms developed during the Oxford Parliament of 1258 to resolve a dispute between King Henry III of England and his barons. The reforms were designed to ensure the king adhered to the rule of law and ...

by barons led by his brother-in-law,

Simon de Montfort

Simon de Montfort, 6th Earl of Leicester ( – 4 August 1265), later sometimes referred to as Simon V de Montfort to distinguish him from his namesake relatives, was a nobleman of French origin and a member of the English peerage, who led the ...

, under which his debts were paid in exchange for substantial reforms. He was also forced to agree to the

Treaty of Paris Treaty of Paris may refer to one of many treaties signed in Paris, France:

Treaties

1200s and 1300s

* Treaty of Paris (1229), which ended the Albigensian Crusade

* Treaty of Paris (1259), between Henry III of England and Louis IX of France

* Trea ...

with

Louis IX of France

Louis IX (25 April 1214 – 25 August 1270), commonly known as Saint Louis or Louis the Saint, was King of France from 1226 to 1270, and the most illustrious of the Direct Capetians. He was crowned in Reims at the age of 12, following the ...

, acknowledging the loss of the

Dukedom of Normandy, Maine, Anjou and Poitou, but retaining the

Channel Islands

The Channel Islands ( nrf, Îles d'la Manche; french: îles Anglo-Normandes or ''îles de la Manche'') are an archipelago in the English Channel, off the French coast of Normandy. They include two Crown Dependencies: the Bailiwick of Jersey, ...

. The treaty held that "islands (if any) which the king of England should hold", he would retain "as peer of France and Duke of Aquitaine".

In exchange Louis withdrew his support for English rebels, ceded three bishoprics and cities, and was to pay an annual rent for possession of

Agenais

Agenais (), or Agenois (), was an ancient region that became a county (Old French: ''conté'' or ''cunté'') of France, south of Périgord.Mish, Frederick C., Editor in Chief. "Agenais". '' Webster's Ninth New Collegiate Dictionary''. 9th ed. Sprin ...

.

Disagreements about the meaning of the treaty began as soon as it was signed.

The agreement resulted in English kings having to pay homage to the French monarch, thus remaining French vassals, but only on French soil. This was one of the indirect causes of the

Hundred Years War

The Hundred Years' War (; 1337–1453) was a series of armed conflicts between the kingdoms of England and France during the Late Middle Ages. It originated from disputed claims to the French throne between the English House of Plantagen ...

.

=Second Barons War and the establishment of Parliament

=

Friction intensified between the barons and the king. Henry repudiated the Provisions of Oxford and obtained a

papal bull in 1261 exempting him from his oath. Both sides began to raise armies.

Prince Edward, Henry's eldest son, was tempted to side with his godfather Simon de Montfort, and supported holding a Parliament in his father's absence, before he decided to support his father. The barons, under Montfort, captured most of south-eastern England. The war, its prelude and aftermath, included a wave of violence targeting Jewish communities in order to destroy evidence of the Baron's debts, a particular grievance of the rebels. 500 Jews died in London, and communities were decimated in

Worcester

Worcester may refer to:

Places United Kingdom

* Worcester, England, a city and the county town of Worcestershire in England

** Worcester (UK Parliament constituency), an area represented by a Member of Parliament

* Worcester Park, London, Englan ...

,

Canterbury

Canterbury (, ) is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city and UNESCO World Heritage Site, situated in the heart of the City of Canterbury local government district of Kent, England. It lies on the River Stour, Kent, River Stour.

...

and elsewhere. At the

Battle of Lewes

The Battle of Lewes was one of two main battles of the conflict known as the Second Barons' War. It took place at Lewes in Sussex, on 14 May 1264. It marked the high point of the career of Simon de Montfort, 6th Earl of Leicester, and made h ...

in 1264, Henry and Edward were defeated and taken prisoner. Montfort summoned the

Great Parliament, regarded as the first English Parliament worthy of the name because it was the first time cities and burghs sent representatives.

Edward escaped and raised an army. He defeated and killed Montfort at the

Battle of Evesham

The Battle of Evesham (4 August 1265) was one of the two main battles of 13th century England's Second Barons' War. It marked the defeat of Simon de Montfort, Earl of Leicester, and the rebellious barons by the future King Edward I, who led the ...

in 1265. Savage retribution was exacted on the rebels and authority was restored to Henry. Edward, having pacified the realm, left England to join Louis IX on the

Ninth Crusade

Lord Edward's crusade, sometimes called the Ninth Crusade, was a military expedition to the Holy Land under the command of Edward, Duke of Gascony (future King Edward I of England) in 1271–1272. It was an extension of the Eighth Crusade and was ...

, funded by an unprecedented levy of one-twentieth of every citizen's movable goods and possessions. He was one of the last crusaders in the tradition aiming to recover the Holy Lands. Louis died before Edward's arrival and the result was anticlimactic; Edward's small force limited him to the relief of

Acre

The acre is a unit of land area used in the imperial

Imperial is that which relates to an empire, emperor, or imperialism.

Imperial or The Imperial may also refer to:

Places

United States

* Imperial, California

* Imperial, Missouri

* Imp ...

and a handful of raids. Surviving a murder attempt by an

assassin

Assassination is the murder of a prominent or VIP, important person, such as a head of state, head of government, politician, world leader, member of a royal family or CEO. The murder of a celebrity, activist, or artist, though they may not ha ...

, Edward left for Sicily later in the year, never to return on crusade. The stability of England's political structure was demonstrated when Henry III died and his son succeeded as Edward I; the barons swore allegiance to Edward even though he did not return for two years.

Edward I (1272–1307)

=Conquest of Wales

=

From the beginning of his reign Edward I sought to organise his inherited territories. As a devotee of the cult of

King Arthur

King Arthur ( cy, Brenin Arthur, kw, Arthur Gernow, br, Roue Arzhur) is a legendary king of Britain, and a central figure in the medieval literary tradition known as the Matter of Britain.

In the earliest traditions, Arthur appears as a ...

he also attempted to enforce claims to primacy within the British Isles. Wales consisted of a number of

princedoms

A principality (or sometimes princedom) can either be a monarchical feudatory or a sovereign state, ruled or reigned over by a regnant-monarch with the title of prince and/or princess, or by a monarch with another title considered to fall under ...

, often in conflict with each other.

Llywelyn ap Gruffudd

Llywelyn ap Gruffudd (c. 1223 – 11 December 1282), sometimes written as Llywelyn ap Gruffydd, also known as Llywelyn the Last ( cy, Llywelyn Ein Llyw Olaf, lit=Llywelyn, Our Last Leader), was the native Prince of Wales ( la, Princeps Wall ...

held north Wales in fee to the English king under the Treaty of Woodstock, but had taken advantage of the English civil wars to consolidate his position as Prince of Wales and maintained that his principality was 'entirely separate from the rights' of England. Edward considered Llywelyn 'a rebel and disturber of the peace'. Edward's determination, military experience and skillful use of ships ended Welsh independence by driving Llywelyn into the mountains. Llywelyn later died in battle. The

Statute of Rhuddlan

The Statute of Rhuddlan (12 Edw 1 cc.1–14; cy, Statud Rhuddlan ), also known as the Statutes of Wales ( la, Statuta Valliae) or as the Statute of Wales ( la, Statutum Valliae, links=no), provided the constitutional basis for the government of ...

extended the shire system, bringing Wales into the English legal framework. When Edward's son was born he was proclaimed as the first English

Prince of Wales

Prince of Wales ( cy, Tywysog Cymru, ; la, Princeps Cambriae/Walliae) is a title traditionally given to the heir apparent to the English and later British throne. Prior to the conquest by Edward I in the 13th century, it was used by the rulers ...

. Edward's Welsh campaign produced one of the largest armies ever assembled by an English king in a formidable combination of heavy Anglo-Norman cavalry and Welsh archers that laid the foundations of later military victories in France. Edward spent around £173,000 on his two Welsh campaigns, largely on a network of castles to secure his control.

=Domestic policy

=

Because of his legal reforms Edward is sometimes called ''The English

Justinian

Justinian I (; la, Iustinianus, ; grc-gre, Ἰουστινιανός ; 48214 November 565), also known as Justinian the Great, was the Byzantine emperor from 527 to 565.

His reign is marked by the ambitious but only partly realized ''renovat ...

'',

although whether he was a reformer or an autocrat responding to events is debated. His campaigns left him in debt. This necessitated that he gain wider national support for his policies among lesser landowners, merchants and traders so that he could raise taxes through frequently summoned Parliaments. When

Philip IV of France

Philip IV (April–June 1268 – 29 November 1314), called Philip the Fair (french: Philippe le Bel), was King of France from 1285 to 1314. By virtue of his marriage with Joan I of Navarre, he was also King of Navarre as Philip I from 12 ...

confiscated the

duchy of Gascony

The Duchy of Gascony or Duchy of Vasconia ( eu, Baskoniako dukerria; oc, ducat de Gasconha; french: duché de Gascogne, duché de Vasconie) was a duchy located in present-day southwestern France and northeastern Spain, an area encompassing the m ...

in 1294, more money was needed to wage war in France. To gain financial support for the war effort, Edward summoned a precedent-setting assembly known as the Model Parliament, which included barons, clergy, knights and townspeople.

Edward imposed his authority on the Church with the

Statutes of Mortmain

The Statutes of Mortmain were two enactments, in 1279 and 1290, passed in the reign of Edward I of England, aimed at preserving the kingdom's revenues by preventing land from passing into the possession of the Church. Possession of property by a ...

that prohibited the donation of land to the Church, asserted the rights of the Crown at the expense of traditional feudal privileges, promoted the uniform administration of justice, raised income and codified the legal system. He also emphasised the role of Parliament and the common law through significant legislation, a

survey of local government and the codification of laws originating from Magna Carta with the

Statute of Westminster 1275

The Statute of Westminster of 1275 (3 Edw. I), also known as the Statute of Westminster I, codified the existing law in England, into 51 chapters. Only Chapter 5 (which mandates free elections) is still in force in the United Kingdom, whilst par ...

. Edward also enacted economic reforms on wool exports to take customs, which amounted to nearly £10,000 a year, and imposed licence fees on gifts of land to the Church. Feudal jurisdiction was regulated by the

Statute of Gloucester

The Statute of Gloucester (6 Edw 1) is a piece of legislation enacted in the Parliament of England during the reign of Edward I. The statute, proclaimed at Gloucester in August 1278, was crucial to the development of English law. The Statute of Gl ...

and

Quo Warranto

In law, especially English and American common law, ''quo warranto'' (Medieval Latin for "by what warrant?") is a prerogative writ requiring the person to whom it is directed to show what authority they have for exercising some right, power, or ...

. The

Statute of Winchester

The Statute of Winchester of 1285 (13 Edw. I, St. 2; Law French: '), also known as the Statute of Winton, was a statute enacted by King Edward I of England that reformed the system of Watch and Ward (watchmen) of the Assize of Arms of 1252, and rev ...

enforced Plantagenet policing authority. The

Statute of Westminster 1285

The Statute of Westminster of 1285, also known as the Statute of Westminster II or the Statute of Westminster the Second, like the Statute of Westminster 1275, is a code in itself, and contains the famous clause '' De donis conditionalibus'', one ...

kept estates within families: tenants only held property for life and were unable to sell the property.

Quia Emptores

''Quia Emptores'' is a statute passed by the Parliament of England in 1290 during the reign of Edward I that prevented tenants from alienating their lands to others by subinfeudation, instead requiring all tenants who wished to alienate the ...

stopped sub-infeudation where tenants subcontracted their properties and related feudal services.

Expulsion of the Jews

The oppression of Jews following their exclusion from the guarantees of Magna Carta peaked with Edward expelling them from England.

Christians were forbidden by

canon law

Canon law (from grc, κανών, , a 'straight measuring rod, ruler') is a set of ordinances and regulations made by ecclesiastical authority (church leadership) for the government of a Christian organization or church and its members. It is th ...

from providing

loans with interest, so the Jews played a key economic role in the country by providing this service. In turn the Plantagenets took advantage of the Jews' status as direct subjects, heavily taxing them at will without the necessity to summon Parliament.

Edward's first major step towards Jewish expulsion was the

Statute of Jewry

The Statute of Jewry was a statute issued by Henry III of England in 1253. In response to England's anti-Jewish hatred, Henry attempted to segregate and debase England's Jews with oppressive laws which included imposing the wearing of a yellow J ...

,

which outlawed all

usury

Usury () is the practice of making unethical or immoral monetary loans that unfairly enrich the lender. The term may be used in a moral sense—condemning taking advantage of others' misfortunes—or in a legal sense, where an interest rate is ch ...

and gave Jews fifteen years to buy agricultural land. However, popular prejudice made Jewish movement into mercantile or agricultural pursuits impossible.

Edward attempted to clear his debts with the expulsion of Jews from Gascony, seizing their property and transferred all outstanding debts payable to himself.

He made his continued tax demands more palatable to his subjects by offering to expel all Jews in exchange.

The heavy tax was passed and the Edict of Expulsion was issued. This proved widely popular and was quickly carried out.

=Anglo-Scottish wars

=

Edward asserted that the king of Scotland owed him feudal allegiance, which embittered Anglo-Scottish relations for the rest of his reign. Edward intended to create a

dual monarchy

Dual monarchy occurs when two separate kingdoms are ruled by the same monarch, follow the same foreign policy, exist in a customs union with each other, and have a combined military but are otherwise self-governing. The term is typically used ...

by marrying his son

Edward

Edward is an English given name. It is derived from the Anglo-Saxon name ''Ēadweard'', composed of the elements '' ēad'' "wealth, fortune; prosperous" and '' weard'' "guardian, protector”.

History

The name Edward was very popular in Anglo-Sa ...

to

Margaret, Maid of Norway

Margaret (, ; March or April 1283 – September 1290), known as the Maid of Norway, was the queen-designate of Scotland from 1286 until her death. As she was never inaugurated, her status as monarch is uncertain and has been debated by historian ...

, who was the sole heir of

Alexander III of Scotland

Alexander III (Medieval ; Modern Gaelic: ; 4 September 1241 – 19 March 1286) was King of Scots from 1249 until his death. He concluded the Treaty of Perth, by which Scotland acquired sovereignty over the Western Isles and the Isle of Man. His ...

. When Margaret died there was no obvious heir to the Scottish throne. Edward was invited by the Scottish magnates to resolve the dispute. Edward obtained recognition from the

competitors for the Scottish throne that he had the 'sovereign lordship of Scotland and the right to determine our several pretensions'. He decided the case in favour of

John Balliol

John Balliol ( – late 1314), known derisively as ''Toom Tabard'' (meaning "empty coat" – coat of arms), was King of Scots from 1292 to 1296. Little is known of his early life. After the death of Margaret, Maid of Norway, Scotland entered an ...

, who duly swore loyalty to him and became king. Edward insisted that Scotland was not independent and that as sovereign lord he had the right to hear in England appeals against Balliol's judgements, undermining Balliol's authority. At the urging of his chief councillors, John entered into an alliance with France in 1295.

In 1296 Edward invaded Scotland, deposing and exiling Balliol.

Edward was less successful in Gascony, which was overrun by the French. His commitments were beginning to outweigh his resources. Chronic debts had been incurred by wars against Flanders and Gascony in France, and Wales and Scotland in Britain. The clergy refused to pay their share of the costs, with the Archbishop of Canterbury threatening excommunication; Parliament was reluctant to contribute to Edward's expensive and unsuccessful military policies.

Humphrey de Bohun, 3rd Earl of Hereford

Humphrey (VI) de Bohun (c. 1249 – 31 December 1298), 3rd Earl of Hereford and 2nd Earl of Essex, was an English nobleman known primarily for his opposition to King Edward I over the '' Confirmatio Cartarum.''Fritze and Robison, (2002) ...

and

Roger Bigod, 5th Earl of Norfolk

Roger Bigod (c. 1245 – bf. 6 December 1306) was 5th Earl of Norfolk.

Origins

He was the son of Hugh Bigod (1211–1266), Justiciar, and succeeded his father's elder brother Roger Bigod, 4th Earl of Norfolk (1209–1270) as 5th Earl of ...

, refused to serve in Gascony, and the barons presented a formal statement of their grievances. Edward was forced to reconfirm the charters (including Magna Carta) to obtain the money he required. A truce and peace treaty with the French king restored the duchy of Gascony to Edward. Meanwhile,

William Wallace

Sir William Wallace ( gd, Uilleam Uallas, ; Norman French: ; 23 August 1305) was a Scottish knight who became one of the main leaders during the First War of Scottish Independence.

Along with Andrew Moray, Wallace defeated an English army a ...

had risen in Balliol's name and recovered most of Scotland, before being defeated at the

Battle of Falkirk

The Battle of Falkirk (''Blàr na h-Eaglaise Brice'' in Gaelic), on 22 July 1298, was one of the major battles in the First War of Scottish Independence. Led by King Edward I of England, the English army defeated the Scots, led by William Wal ...

.

Edward summoned a full Parliament, including elected Scottish representatives for the settlement of Scotland. The new government in Scotland featured

Robert the Bruce

Robert I (11 July 1274 – 7 June 1329), popularly known as Robert the Bruce (Scottish Gaelic: ''Raibeart an Bruis''), was King of Scots from 1306 to his death in 1329. One of the most renowned warriors of his generation, Robert eventual ...

, but he rebelled and was crowned king of Scotland. Despite failing health, Edward was carried north to pursue another campaign, but he died en route at

Burgh by Sands

Burgh by Sands () is a village and civil parish in the City of Carlisle district of Cumbria, England, situated near the Solway Firth. The parish includes the village of Burgh by Sands along with Longburgh, Dykesfield, Boustead Hill, Moorhouse ...

.

Even though Edward had requested that his bones should be carried on Scottish campaigns and that his heart be taken to the Holy Land, he was buried at Westminster Abbey in a plain black marble tomb that in later years was painted with the words Scottorum malleus (Hammer of the Scots) and Pactum serva (Honour the vow). He was succeeded by his son as Edward II.

Edward II (1307–27)

Edward II's coronation oath on his succession in 1307 was the first to reflect the king's responsibility to maintain the laws that the community "shall have chosen" ("''aura eslu''").

The king was initially popular but faced three challenges: discontent over the financing of wars; his household spending and the role of his

favourite

A favourite (British English) or favorite (American English) was the intimate companion of a ruler or other important person. In post-classical and early-modern Europe, among other times and places, the term was used of individuals delegated si ...

Piers Gaveston

Piers Gaveston, Earl of Cornwall (c. 1284 – 19 June 1312) was an English nobleman of Gascon origin, and the favourite of Edward II of England.

At a young age, Gaveston made a good impression on King Edward I, who assigned him to the househo ...

.

When Parliament decided that Gaveston should be exiled the king had no choice but to comply.

The king engineered Gaveston's return, but was forced to agree to the appointment of

Ordainers

The Ordinances of 1311 were a series of regulations imposed upon King Edward II by the peerage and clergy of the Kingdom of England to restrict the power of the English monarch. The twenty-one signatories of the Ordinances are referred to as the Lo ...

, led by his cousin

Thomas, 2nd Earl of Lancaster

Thomas of Lancaster, 2nd Earl of Lancaster, 2nd Earl of Leicester, 2nd Earl of Derby, ''jure uxoris'' 4th Earl of Lincoln and ''jure uxoris'' 5th Earl of Salisbury (c. 1278 – 22 March 1322) was an English nobleman. A member of the House of Pl ...

, to reform the royal household with Piers Gaveston exiled again.

=Great Famine

=

In the spring of 1315 unusually heavy rain began in much of Europe. Throughout the spring and summer, it continued to rain and the temperature remained cool. These conditions caused widespread crop failures. The straw and hay for the animals could not be cured and there was no fodder for livestock. The price of food began to rise, doubling in England between spring and midsummer. Salt, the only way to cure and preserve meat, was difficult to obtain because it could not be extracted through evaporation in the wet weather; it peaked in price in the period 1310–20, reaching double the price from the decade before. In the spring of 1316 it continued to rain on a European population deprived of energy and reserves to sustain itself. All segments of society from nobles to peasants were affected, but especially the peasants who were the overwhelming majority of the population and who had no reserve food supplies. The height of the famine was reached in 1317 as the wet weather continued. Finally, in the summer the weather returned to its normal patterns. By now, however, people were so weakened by diseases such as

pneumonia

Pneumonia is an inflammatory condition of the lung primarily affecting the small air sacs known as alveoli. Symptoms typically include some combination of productive or dry cough, chest pain, fever, and difficulty breathing. The severity ...

,

bronchitis

Bronchitis is inflammation of the bronchi (large and medium-sized airways) in the lungs that causes coughing. Bronchitis usually begins as an infection in the nose, ears, throat, or sinuses. The infection then makes its way down to the bronchi. ...

, and

tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB) is an infectious disease usually caused by '' Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can also affect other parts of the body. Most infections show no symptoms, in ...

, and so much of the seed stock had been eaten, that it was not until 1325 that the food supply returned to relatively normal conditions and the population began to increase again.

=Late reign and deposition

=

The Ordinances were published widely to obtain maximum popular support but there was a struggle over their repeal or continuation for a decade.

When Gaveston returned again to England, he was abducted and executed after a mock trial.

This brutal act drove

Thomas, 2nd Earl of Lancaster

Thomas of Lancaster, 2nd Earl of Lancaster, 2nd Earl of Leicester, 2nd Earl of Derby, ''jure uxoris'' 4th Earl of Lincoln and ''jure uxoris'' 5th Earl of Salisbury (c. 1278 – 22 March 1322) was an English nobleman. A member of the House of Pl ...

, and his adherents from power. Edward's humiliating defeat at the

Battle of Bannockburn

The Battle of Bannockburn ( gd, Blàr Allt nam Bànag or ) fought on June 23–24, 1314, was a victory of the army of King of Scots Robert the Bruce over the army of King Edward II of England in the First War of Scottish Independence. It was ...

in 1314 confirmed Bruce's position as an independent king of Scots. In England it returned the initiative to Lancaster and

Guy de Beauchamp, 10th Earl of Warwick

Guy de Beauchamp, 10th Earl of Warwick (c. 127212 August 1315) was an English magnate, and one of the principal opponents of King Edward II and his favourite, Piers Gaveston. Guy was the son of William de Beauchamp, the first Beauchamp earl ...

, who had not taken part in the campaign, claiming that it was in defiance of the Ordinances.

Edward finally repealed the Ordinances after defeating Lancaster at the

Battle of Boroughbridge

The Battle of Boroughbridge was fought on 16 March 1322 in England between a group of rebellious barons and the forces of King Edward II, near Boroughbridge, north-west of York. The culmination of a long period of antagonism between the King a ...

and then executing him in 1322.

The

War of Saint-Sardos

The War of Saint-Sardos was a short war fought between the Kingdom of England and the Kingdom of France in 1324. The French invaded the English Duchy of Aquitaine. The war was a clear defeat for the English, and led indirectly to the overthrow of ...

, a short conflict between Edward and the

Kingdom of France

The Kingdom of France ( fro, Reaume de France; frm, Royaulme de France; french: link=yes, Royaume de France) is the historiographical name or umbrella term given to various political entities of France in the medieval and early modern period. ...

, led indirectly to Edward's overthrow. The French monarchy used the jurisdiction of the

Parlement of Paris

The Parliament of Paris (french: Parlement de Paris) was the oldest ''parlement'' in the Kingdom of France, formed in the 14th century. It was fixed in Paris by Philip IV of France in 1302. The Parliament of Paris would hold sessions inside the ...

to overrule decisions of the nobility's courts. As a French vassal, Edward felt this encroachment in Gascony with the French kings adjudicating disputes between him and his French subjects. Without confrontation he could do little but watch the duchy shrink.

Edmund of Woodstock, 1st Earl of Kent

Edmund of Woodstock, 1st Earl of Kent (5 August 130119 March 1330), whose seat was Arundel Castle in Sussex, was the sixth son of King Edward I of England, and the second by his second wife Margaret of France, and was a younger half-brother ...

, decided to resist one such judgement in

Saint-Sardos with the result that Charles IV declared the duchy forfeit. Charles's sister,

Queen Isabella, was sent to negotiate and agreed to a treaty that required Edward to pay homage in France to Charles. Edward resigned Aquitaine and Ponthieu to his son,

Prince Edward, who travelled to France to give homage in his stead. With the English heir in her power, Isabella refused to return to England unless Edward II dismissed his favourites and also formed a relationship with

Roger Mortimer, 1st Earl of March

Roger Mortimer, 3rd Baron Mortimer of Wigmore, 1st Earl of March (25 April 1287 – 29 November 1330), was an English nobleman and powerful Marcher Lord who gained many estates in the Welsh Marches and Ireland following his advantageous marri ...

.

The couple invaded England and, joined by

Henry, 3rd Earl of Lancaster

Henry, 3rd Earl of Leicester and Lancaster ( – 22 September 1345) was a grandson of King Henry III of England (1216–1272) and was one of the principals behind the deposition of King Edward II of England, Edward II (1307–1327), his first c ...

, captured the king.

Edward II abdicated on the condition that his son would inherit the throne rather than Mortimer. He is generally believed to have been murdered at Berkeley Castle by having a red-hot poker thrust into his bowels.

In 1330 a coup by Edward III ended four years of control by Isabella and Mortimer. Mortimer was executed, but although removed from power, Isabella was treated well, living in luxury for the next 27 years.

Edward III (1327–77)

=Renewal of the Scottish War

=

After the defeat of the English under the Mortimer regime by the Scots at

Battle of Stanhope Park

The Weardale campaign, part of the First War of Scottish Independence, occurred during July and August 1327 in Weardale, England. A Scottish force under James, Lord of Douglas, and the earls of Moray and Mar faced an English army commande ...

, the

Treaty of Edinburgh–Northampton

The Treaty of Edinburgh–Northampton was a peace treaty signed in 1328 between the Kingdoms of England and Scotland. It brought an end to the First War of Scottish Independence, which had begun with the English party of Scotland in 1296. The ...

was signed in Edward III's name in 1328. Edward was not content with the peace agreement, but the renewal of the war with Scotland originated in private, rather than royal initiative. A group of English

magnate

The magnate term, from the late Latin ''magnas'', a great man, itself from Latin ''magnus'', "great", means a man from the higher nobility, a man who belongs to the high office-holders, or a man in a high social position, by birth, wealth or ot ...

s known as The Disinherited, who had lost land in Scotland by the peace accord, staged an invasion of Scotland and won a victory at the

Battle of Dupplin Moor

The Battle of Dupplin Moor was fought between supporters of King David II of Scotland, the son of King Robert Bruce, and English-backed invaders supporting Edward Balliol, son of King John I of Scotland, on 11 August 1332. It took place a lit ...

in 1332. They attempted to install

Edward Balliol

Edward Balliol (; 1283 – January 1364) was a claimant to the Scottish throne during the Second War of Scottish Independence. With English help, he ruled parts of the kingdom from 1332 to 1356.

Early life

Edward was the eldest son of John Ba ...

as king of Scotland in

David II's place, but Balliol was soon expelled and was forced to seek the help of Edward III. The English king responded by laying siege to the important border town of

Berwick and defeated a large relieving army at the

Battle of Halidon Hill

The Battle of Halidon Hill took place on 19 July 1333 when a Scottish army under Sir Archibald Douglas attacked an English army commanded by King Edward III of England () and was heavily defeated. The year before, Edward Balliol had seized ...

. Edward reinstated Balliol on the throne and received a substantial amount of land in southern Scotland. These victories proved hard to sustain, however, as forces loyal to David II gradually regained control of the country. In 1338, Edward was forced to agree to a truce with the Scots.

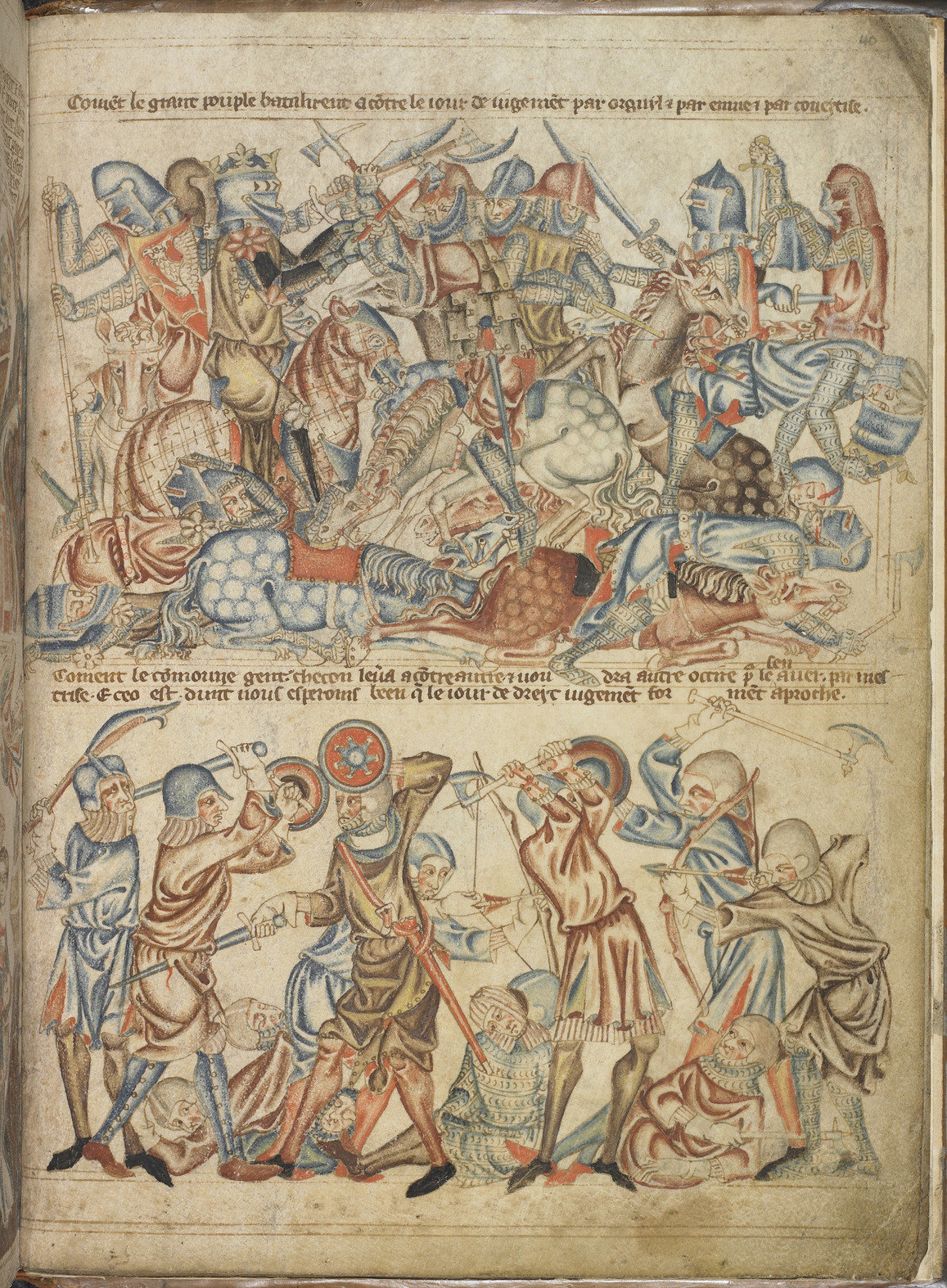

=Hundred Years' War

=

In 1328

Charles IV of France

Charles IV (18/19 June 1294 – 1 February 1328), called the Fair (''le Bel'') in France and the Bald (''el Calvo'') in Navarre, was last king of the direct line of the House of Capet, King of France and King of Navarre (as Charles I) from 132 ...

died without a male heir. His cousin

Phillip of Valois and

Queen Isabella, on behalf of her son Edward, were the major claimants to the throne. Philip, as senior grandson of

Philip III of France

Philip III (1 May 1245 – 5 October 1285), called the Bold (french: le Hardi), was King of France from 1270 until his death in 1285. His father, Louis IX, died in Tunis during the Eighth Crusade. Philip, who was accompanying him, returned ...

in the male line, became king over Edward's claim as a

matrilineal

Matrilineality is the tracing of kinship through the female line. It may also correlate with a social system in which each person is identified with their matriline – their mother's Lineage (anthropology), lineage – and which can in ...

grandson of Philip IV of France, following the precedents of Philip V's succession over his niece

Joan II of Navarre

Joan II (french: Jeanne; 28 January 1312 – 6 October 1349) was Queen of Navarre from 1328 until her death. She was the only surviving child of Louis X of France, King of France and Navarre, and Margaret of Burgundy. Joan's paternity was dubiou ...

and Charles IV's succession over his nieces. Not yet in power, Edward III paid homage to Phillip as Duke of Aquitaine and the French king continued to assert feudal pressure on Gascony.

Philip demanded that Edward extradite an exiled French adviser,

Robert III of Artois

Robert III of Artois (1287 – between 6 October & 20 November 1342) was Lord of Conches-en-Ouche, of Domfront, and of Mehun-sur-Yèvre, and in 1309 he received as appanage the county of Beaumont-le-Roger in restitution for the County of Artois ...

, and, when he refused, declared Edward's lands in Gascony and

Ponthieu

Ponthieu (, ) was one of six feudal counties that eventually merged to become part of the Province of Picardy, in northern France.Dunbabin.France in the Making. Ch.4. The Principalities 888-987 Its chief town is Abbeville.

History

Ponthieu play ...

forfeit.

In response Edward put together a coalition of continental supporters, promising payment of over £200,000.

Edward borrowed heavily from the banking houses of the

Bardi and

Peruzzi

The Peruzzi were bankers of Florence, among the leading families of the city in the 14th century, before the rise to prominence of the Medici. Their modest antecedents stretched back to the mid 11th century, according to the family's genealogist ...

, merchants in the Low Countries, and

William de la Pole

William is a male given name of Germanic origin.Hanks, Hardcastle and Hodges, ''Oxford Dictionary of First Names'', Oxford University Press, 2nd edition, , p. 276. It became very popular in the English language after the Norman conquest of Engl ...

, a wealthy merchant who came to the king's rescue by advancing him £110,000.

Edward also asked Parliament for a grant of £300,000 in return for further concessions.

The delay caused by fundraising allowed the French to invade Gascony, and threaten the English ports

while the English conducted widespread

piracy in the Channel.

Edward proclaimed himself king of France to encourage the Flemish to rise in open rebellion against the French king and won a significant naval victory at the

Battle of Sluys

The Battle of Sluys (; ), also called the Battle of l'Écluse, was a naval battle fought on 24 June 1340 between England and France. It took place in the roadstead of the port of Sluys (French ''Écluse''), on a since silted-up inlet betwee ...

, where the French fleet was almost completely destroyed. Inconclusive fighting continued at the

Battle of Saint-Omer

The Battle of Saint-Omer, fought on 26 July 1340, was a major engagement in the early stages of the Hundred Years' War, during Edward III's 1340 summer campaign against France launched from Flanders. The campaign was initiated in the aftermath o ...

and the

Siege of Tournai (1340)

The siege of Tournai (23 July - 25 September 1340) occurred during the Edwardian phase of the Hundred Years' War. The Siege began when a coalition of England, Flanders, Hainaut, Brabant and the Holy Roman Empire under the command of King Edwa ...

, but with both sides running out of money, the fighting ended with the

Truce of Espléchin

The Truce of Espléchin (1340) was a truce between the English and French crowns during the early phases of the Hundred Years' War.

Background

The Hundred Years' War had started in 1337. After a naval defeat at the hands of the French at the Ba ...

. Edward III had achieved nothing of military value and English political opinion was against him. Bankrupt, he cut his losses, ruining many whom he could not, or chose not, to repay.

Both countries suffered from war exhaustion. The tax burden had been heavy and the wool trade had been disrupted. Edward spent the following years paying off his immense debt, while the Gascons merged the war with banditry. In 1346 Edward invaded from the Low Countries using the strategy of

chevauchée

A ''chevauchée'' (, "promenade" or "horse charge", depending on context) was a raiding method of medieval warfare for weakening the enemy, primarily by burning and pillaging enemy territory in order to reduce the productivity of a region, in add ...

, a large extended raid for plunder and destruction that would be deployed by the English throughout the war. The chevauchée discredited Philip VI of France's government and threatened to detach his vassals from loyalty. Edward fought two successful actions, the

Storming of Caen and the

Battle of Blanchetaque

The Battle of Blanchetaque was fought on 24 August 1346 between an Kingdom of England, English army under King Edward III and a Kingdom of France, French force commanded by Godemar I du Fay, Godemar du Fay. The battle was part of the Crécy ...

. He then found himself outmanoeuvred and outnumbered by Philip and was forced to fight at

Crécy. The battle was a crushing defeat for the French, leaving Edward free to capture the important port of

Calais

Calais ( , , traditionally , ) is a port city in the Pas-de-Calais department, of which it is a subprefecture. Although Calais is by far the largest city in Pas-de-Calais, the department's prefecture is its third-largest city of Arras. Th ...

. A subsequent victory against Scotland at the

Battle of Neville's Cross

The Battle of Neville's Cross took place during the Second War of Scottish Independence on 17 October 1346, half a mile (800 m) to the west of Durham, England. An invading Scottish army of 12,000 led by King David II was defeated with heavy loss ...

resulted in the capture of

David II and reduced the threat from Scotland.

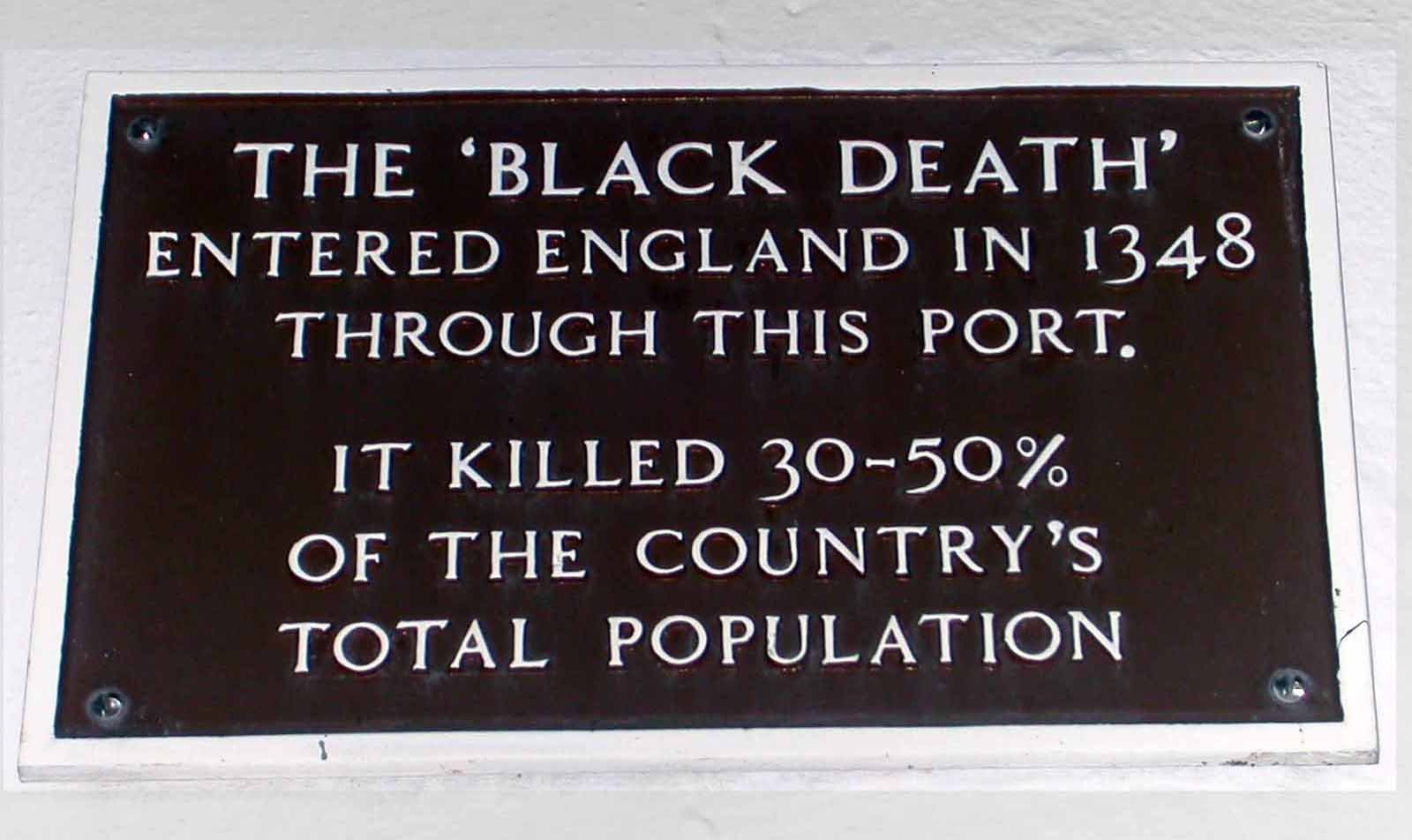

=Black Death

=

According to the chronicle of the

grey friars

, image = FrancescoCoA PioM.svg

, image_size = 200px

, caption = A cross, Christ's arm and Saint Francis's arm, a universal symbol of the Franciscans

, abbreviation = OFM

, predecessor =

, ...

at

King's Lynn

King's Lynn, known until 1537 as Bishop's Lynn and colloquially as Lynn, is a port and market town in the borough of King's Lynn and West Norfolk in the county of Norfolk, England. It is located north of London, north-east of Peterborough, no ...

, the plague arrived by ship from

Gascony

Gascony (; french: Gascogne ; oc, Gasconha ; eu, Gaskoinia) was a province of the southwestern Kingdom of France that succeeded the Duchy of Gascony (602–1453). From the 17th century until the French Revolution (1789–1799), it was part o ...

to

Melcombe in Dorsettoday normally referred to as

Weymouthshortly before "the

Feast of St. John The Baptist

The Nativity of John the Baptist (or Birth of John the Baptist, or Nativity of the Forerunner, or colloquially Johnmas or St. John's Day (in German) Johannistag) is a Christian feast day celebrating the birth of John the Baptist. It is observed ...

" on 24 June 1348. From Weymouth the disease spread rapidly across the south-west. The first major city to be struck was

Bristol

Bristol () is a city, ceremonial county and unitary authority in England. Situated on the River Avon, it is bordered by the ceremonial counties of Gloucestershire to the north and Somerset to the south. Bristol is the most populous city in ...

. London was reached in the autumn of 1348, before most of the surrounding countryside. This had certainly happened by November, though according to some accounts as early as 29 September. The full effect of the plague was felt in the capital early the next year. Conditions in London were ideal for the plague: the streets were narrow and flowing with sewage, and houses were overcrowded and poorly ventilated. By March 1349 the disease was spreading in a haphazard way across all of southern England. During the first half of 1349 the Black Death spread northwards. A second front opened up when the plague arrived by ship at the

Humber

The Humber is a large tidal estuary on the east coast of Northern England. It is formed at Trent Falls, Faxfleet, by the confluence of the tidal rivers Ouse and Trent. From there to the North Sea, it forms part of the boundary between th ...

, from where it spread both south and north. In May it reached

York

York is a cathedral city with Roman origins, sited at the confluence of the rivers Ouse and Foss in North Yorkshire, England. It is the historic county town of Yorkshire. The city has many historic buildings and other structures, such as a ...

, and during the summer months of June, July and August, it ravaged the north. Certain northern counties, like

Durham Durham most commonly refers to:

*Durham, England, a cathedral city and the county town of County Durham

*County Durham, an English county

*Durham County, North Carolina, a county in North Carolina, United States

*Durham, North Carolina, a city in No ...

and

Cumberland

Cumberland ( ) is a historic county in the far North West England. It covers part of the Lake District as well as the north Pennines and Solway Firth coast. Cumberland had an administrative function from the 12th century until 1974. From 19 ...

, had been the victim of violent incursions from the Scots, and were therefore left particularly vulnerable to the devastations of the plague. Pestilence is less virulent during the winter months, and spreads less rapidly. The Black Death in England had survived the winter of 1348–49, but during the following winter it ended, and by December 1349 conditions were returning to relative normalcy. It had taken the disease approximately 500 days to traverse the entire country. The Black Death brought a halt to Edward's campaigns by killing between a third to more than half of his subjects.

The king passed the

Ordinance of Labourers

The Ordinance of Labourers 1349 (23 Edw. 3) is often considered to be the start of English labour law.''Employment Law: Cases and Materials''. Rothstein, Liebman. Sixth Edition, Foundation Press. p. 20. Specifically, it fixed wages and imposed ...

and the

Statute of Labourers

The Statute of Labourers was a law created by the English parliament under King Edward III in 1351 in response to a labour shortage, which aimed at regulating the labour force by prohibiting requesting or offering a wage higher than pre-Plague sta ...

in response to the shortage of labour and social unrest that followed the plague.

The labour laws were ineffectively enforced and the repressive measures caused resentment.

=Poitiers campaign and expansion of the conflict (1356–68)

=

In 1356

Edward, Prince of Wales, resumed the war with one of the most destructive chevauchées of the conflict. Starting from Bordeaux he laid waste to the lands of Armagnac before turning eastward into Languedoc. Toulouse prepared for a siege, but the Prince's army was not equipped for one, so he bypassed the city and continued south, pillaging and burning. Unlike large cities such as Toulouse, the rural French villages were not organised to provide a defence, making them much more attractive targets. In a second great chevauchée the Prince burned the suburbs of Bourges without capturing the city, before marching west along the Loire River to Poitiers, where the

Battle of Poitiers

The Battle of Poitiers was fought on 19September 1356 between a French army commanded by King JohnII and an Anglo- Gascon force under Edward, the Black Prince, during the Hundred Years' War. It took place in western France, south of Poi ...

resulted in a decisive English victory and the capture of

John II of France

John II (french: Jean II; 26 April 1319 – 8 April 1364), called John the Good (French: ''Jean le Bon''), was King of France from 1350 until his death in 1364. When he came to power, France faced several disasters: the Black Death, which kill ...

. The

Second Treaty of London

The Treaty of London (also known as the Second Treaty of London) was proposed by England, accepted by France, and signed in 1359. After Edward the Black Prince soundly defeated the French at Poitiers (during the Hundred Years' War), where the ...

was signed, which promised a four million écus ransom. It was guaranteed by the Valois family hostages being held in London, while John returned to France to raise his ransom. Edward gained possession of Normandy, Brittany, Anjou, Maine and the coastline from Flanders to Spain, restoring the lands of the former Angevin Empire. The hostages quickly escaped back to France. John, horrified that his word had been broken, returned to England and died there. Edward invaded France in an attempt to take advantage of the popular rebellion of the

Jacquerie

The Jacquerie () was a popular revolt by peasants that took place in northern France in the early summer of 1358 during the Hundred Years' War. The revolt was centred in the valley of the Oise north of Paris and was suppressed after a few week ...

, hoping to seize the throne. Although no French army stood against him, he was unable to take Paris or

Rheims

Reims ( , , ; also spelled Rheims in English) is the most populous city in the French department of Marne, and the 12th most populous city in France. The city lies northeast of Paris on the Vesle river, a tributary of the Aisne.

Founded by ...

. In the subsequent

Treaty of Brétigny

The Treaty of Brétigny was a treaty, drafted on 8 May 1360 and ratified on 24 October 1360, between Kings Edward III of England and John II of France. In retrospect, it is seen as having marked the end of the first phase of the Hundred Years' ...

he renounced his claim to the French crown, but greatly expanded his territory in Aquitaine and confirmed his conquest of Calais.

Fighting in the Hundred Years' War often spilled from the French and Plantagenet lands into surrounding realms. This included the dynastic conflict in Castile between

Peter of Castile

Peter ( es, Pedro; 30 August 133423 March 1369), called the Cruel () or the Just (), was King of Castile and León from 1350 to 1369. Peter was the last ruler of the main branch of the House of Ivrea. He was excommunicated by Pope Urban V for ...

and

Henry II of Castile

Henry II (13 January 1334 – 29 May 1379), called Henry of Trastámara or the Fratricidal (''el Fratricida''), was the first King of Castile and León from the House of Trastámara. He became king in 1369 by defeating his half-brother Peter the ...

. Edward, Prince of Wales, allied himself with Peter, defeating Henry at the

Battle of Nájera

The Battle of Nájera, also known as the Battle of Navarrete, was fought on 3 April 1367 to the northeast of Nájera, in the province of La Rioja, Castile. It was an episode of the first Castilian Civil War which confronted King Peter of Casti ...

before falling out with Peter, who had no means to reimburse him, leaving Edward bankrupt. The Plantagenets continued to interfere and

John of Gaunt, 1st Duke of Lancaster

John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster (6 March 1340 – 3 February 1399) was an English royal prince, military leader, and statesman. He was the fourth son (third to survive infancy as William of Hatfield died shortly after birth) of King Edward ...

, the prince's brother, married Peter's daughter

Constance

Constance may refer to:

Places

*Konstanz, Germany, sometimes written as Constance in English

*Constance Bay, Ottawa, Canada

* Constance, Kentucky

* Constance, Minnesota

* Constance (Portugal)

* Mount Constance, Washington State

People

* Consta ...

, claiming the Crown of Castile in the name of his wife. He arrived with an army, asking

John I John I may refer to:

People

* John I (bishop of Jerusalem)

* John Chrysostom (349 – c. 407), Patriarch of Constantinople

* John of Antioch (died 441)

* Pope John I, Pope from 523 to 526

* John I (exarch) (died 615), Exarch of Ravenna

* John I o ...

to give up the throne in favour of Constance. John declined; instead his son married John of Gaunt's daughter,

Catherine of Lancaster

Catherine of Lancaster ( Castilian: ''Catalina''; 31 March 1373 – 2 June 1418) was Queen of Castile by marriage to King Henry III of Castile. She governed Castile as regent from 1406 until 1418 during the minority of her son.

Queen Catherine ...

, creating the title

Prince of Asturias

Prince or Princess of Asturias ( es, link=no, Príncipe/Princesa de Asturias; ast, Príncipe d'Asturies) is the main substantive title used by the heir apparent or heir presumptive to the monarchy of Spain, throne of Spain. According to the Sp ...

for the couple.

=French resurgence (1369–77)

=

Charles V of France

Charles V (21 January 1338 – 16 September 1380), called the Wise (french: le Sage; la, Sapiens), was King of France from 1364 to his death in 1380. His reign marked an early high point for France during the Hundred Years' War, with his armi ...

resumed hostilities when Prince Edward refused a summons as

Duke of Aquitaine

The Duke of Aquitaine ( oc, Duc d'Aquitània, french: Duc d'Aquitaine, ) was the ruler of the medieval region of Aquitaine (not to be confused with modern-day Aquitaine) under the supremacy of Frankish, English, and later French kings.

As succe ...

and his reign saw the Plantagenets steadily pushed back in France.

Prince Edward went on to demonstrate the brutal character that some think is the cause of his name of the "Black Prince" at the

Siege of Limoges

The town of Limoges had been under English control but in August 1370 it surrendered to the French, opening its gates to the Duke of Berry. The siege of Limoges was laid by the English army led by Edward the Black Prince in the second week in ...

. After the town had opened its gates to

John, Duke of Berry

John of Berry or John the Magnificent ( French: ''Jean de Berry'', ; 30 November 1340 – 15 June 1416) was Duke of Berry and Auvergne and Count of Poitiers and Montpensier. He was Regent of France during the minority of his nephew 1380-1388 ...

, he directed the massacre of 3,000 inhabitants, men, women and children.

Following this the prince was too ill to contribute to the war or government and returned to England, where he soon died: the son of a king and the father of a king, but never a king himself.

Prince Edward's brother

John of Gaunt, 1st Duke of Lancaster

John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster (6 March 1340 – 3 February 1399) was an English royal prince, military leader, and statesman. He was the fourth son (third to survive infancy as William of Hatfield died shortly after birth) of King Edward ...

assumed leadership of the English in France. Despite further chevauchées, destroying the countryside and the productivity of the land, his efforts were strategically ineffective.

The French commander,

Bertrand Du Guesclin

Bertrand du Guesclin ( br, Beltram Gwesklin; 1320 – 13 July 1380), nicknamed "The Eagle of Brittany" or "The Black Dog of Brocéliande", was a Breton knight and an important military commander on the French side during the Hundred Years' W ...

adopted

Fabian tactics in avoiding major English field forces while capturing towns, including

Poitiers

Poitiers (, , , ; Poitevin: ''Poetàe'') is a city on the River Clain in west-central France. It is a commune and the capital of the Vienne department and the historical centre of Poitou. In 2017 it had a population of 88,291. Its agglomerat ...

and

Bergerac. In a further strategic blow, English dominance at sea was reversed by the disastrous defeat at the

Battle of La Rochelle

The Battle of La Rochelle was a naval battle fought on 22 and 23 June 1372 between a Castilian fleet commanded by the Castilian Ambrosio Boccanegra and an English fleet commanded by John Hastings, 2nd Earl of Pembroke. The Castilian fleet had ...

, undermining English seaborne trade and allowing Gascony to be threatened.

Richard II (1377–99)

=Peasants' Revolt

=

The 10-year-old Richard II succeeded on the deaths of his father and grandfather, with government in the hands of a regency council until he came of age. The poor state of the economy caused significant civil unrest as his government levied a number of

poll taxes

A poll tax, also known as head tax or capitation, is a tax levied as a fixed sum on every liable individual (typically every adult), without reference to income or resources.

Head taxes were important sources of revenue for many governments fr ...

to finance military campaigns. The tax of one shilling for everyone over the age of 15 proved particularly unpopular. This, combined with enforcement of the

Statute of Labourers

The Statute of Labourers was a law created by the English parliament under King Edward III in 1351 in response to a labour shortage, which aimed at regulating the labour force by prohibiting requesting or offering a wage higher than pre-Plague sta ...

, which curbed employment standards and wages,

triggered an uprising with a refusal to pay the tax in 1381. Kent rebels, led by

Wat Tyler

Wat Tyler (c. 1320/4 January 1341 – 15 June 1381) was a leader of the 1381 Peasants' Revolt in England. He led a group of rebels from Canterbury to London to oppose the institution of a poll tax and to demand economic and social reforms. Wh ...

, marched on London. Initially, there were only attacks on certain properties, many of them associated with John of Gaunt. The rebels are reputed to have been met by the young king himself and presented him with a series of demands, including the dismissal of some of his ministers and the abolition of

serfdom

Serfdom was the status of many peasants under feudalism, specifically relating to manorialism, and similar systems. It was a condition of debt bondage and indentured servitude with similarities to and differences from slavery, which develop ...

. Rebels stormed the

Tower of London

The Tower of London, officially His Majesty's Royal Palace and Fortress of the Tower of London, is a historic castle on the north bank of the River Thames in central London. It lies within the London Borough of Tower Hamlets, which is separa ...

and executed those hiding there.

At

Smithfield further negotiations were arranged, but Tyler behaved belligerently and in the ensuing dispute

William Walworth

Sir William Walworth (died 1385) was an English nobleman and politician who was twice Lord Mayor of London (1374–75 and 1380–81). He is best known for killing Wat Tyler during the Peasants' Revolt in 1381.

Political career

His family cam ...

, the Lord Mayor of London, attacked and killed Tyler. Richard seized the initiative shouting "You shall have no captain but me",

a statement left deliberately ambiguous to defuse the situation. He had promised clemency, but on re-establishing control he pursued, captured and executed the other leaders of the rebellion and all concessions were revoked.

=Deposition

=

A group of

magnates

The magnate term, from the late Latin ''magnas'', a great man, itself from Latin ''magnus'', "great", means a man from the higher nobility, a man who belongs to the high office-holders, or a man in a high social position, by birth, wealth or ot ...

consisting of the king's uncle

Thomas of Woodstock, 1st Duke of Gloucester

Thomas of Woodstock, 1st Duke of Gloucester (7 January 13558 or 9 September 1397) was the fifth surviving son and youngest child of King Edward III of England and Philippa of Hainault.

Early life

Thomas was born on 7 January 1355 at Woodstock ...

,

Richard FitzAlan, 11th Earl of Arundel

Richard Fitzalan, 4th Earl of Arundel, 9th Earl of Surrey, KG (1346 – 21 September 1397) was an English medieval nobleman and military commander.

Lineage

Born in 1346, he was the son of Richard Fitzalan, 3rd Earl of Arundel and Eleanor of L ...

, and

Thomas de Beauchamp, 12th Earl of Warwick

Thomas may refer to:

People

* List of people with given name Thomas

* Thomas (name)

* Thomas (surname)

* Saint Thomas (disambiguation)

* Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274) Italian Dominican friar, philosopher, and Doctor of the Church

* Thomas the Ap ...

, became known as the

Lords Appellant