Landis's Battery on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Landis's Missouri Battery, also known as Landis's Company, Missouri Light Artillery, was an

In

In

artillery battery

In military organizations, an artillery battery is a unit or multiple systems of artillery, mortar systems, rocket artillery, multiple rocket launchers, surface-to-surface missiles, ballistic missiles, cruise missiles, etc., so grouped to fac ...

that served in the Confederate States Army

The Confederate States Army, also called the Confederate Army or the Southern Army, was the military land force of the Confederate States of America (commonly referred to as the Confederacy) during the American Civil War (1861–1865), fighting ...

during the early stages of the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

. The battery was formed when Captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police department, election precinct, e ...

John C. Landis recruited men from the Missouri State Guard

The Missouri State Guard (MSG) was a military force established by the Missouri General Assembly on May 11, 1861. While not a formation of the Confederate States Army, the Missouri State Guard fought alongside Confederate troops and, at various ...

in late 1861 and early 1862. The battery fielded two 12-pounder Napoleon

The M1857 12-pounder Napoleon or Light 12-pounder gun or 12-pounder gun-howitzer was a bronze smoothbore muzzleloading artillery piece that was adopted by the United States Army in 1857 and extensively employed in the American Civil War. The gun ...

field gun

A field gun is a field artillery piece. Originally the term referred to smaller guns that could accompany a field army on the march, that when in combat could be moved about the battlefield in response to changing circumstances ( field artille ...

s and two 24-pounder howitzers for much of its existence, and had a highest reported numerical strength of 62 men. After initially serving in the Trans-Mississippi Theater, where it may have fought in the Battle of Pea Ridge

The Battle of Pea Ridge (March 7–8, 1862), also known as the Battle of Elkhorn Tavern, took place in the American Civil War near Leetown, northeast of Fayetteville, Arkansas. Federal forces, led by Brig. Gen. Samuel R. Curtis, moved south ...

, the unit was transferred east of the Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson Bay drainage system. From its traditional source of Lake Itasca in northern Minnesota, it f ...

. The battery saw limited action in 1862 at the Battle of Iuka

A battle is an occurrence of combat in warfare between opposing military units of any number or size. A war usually consists of multiple battles. In general, a battle is a military engagement that is well defined in duration, area, and force ...

and at the Second Battle of Corinth

The second Battle of Corinth (which, in the context of the American Civil War, is usually referred to as the Battle of Corinth, to differentiate it from the siege of Corinth earlier the same year) was fought October 3–4, 1862, in Corinth, M ...

.

In 1863, the unit was transferred to Grand Gulf, Mississippi

Grand Gulf is a ghost town in Claiborne County, Mississippi, United States.

History

Grand Gulf was named for the large whirlpool, (or gulf), formed by the Mississippi River flowing against a large rocky bluff. La Salle and Zadok Cramer commente ...

, a key point on the Mississippi River. After Major General

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of a ...

Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant ; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was an American military officer and politician who served as the 18th president of the United States from 1869 to 1877. As Commanding General, he led the Union Ar ...

landed Union infantry at Bruinsburg, Landis's Battery formed part of Confederate defenses at the battles of Port Gibson

Port Gibson is a city in Claiborne County, Mississippi, United States. The population was 1,567 at the 2010 census. Port Gibson is the county seat of Claiborne County, which is bordered on the west by the Mississippi River. It is the site of th ...

in early May, after which Landis was promoted and Lieutenant

A lieutenant ( , ; abbreviated Lt., Lt, LT, Lieut and similar) is a commissioned officer rank in the armed forces of many nations.

The meaning of lieutenant differs in different militaries (see comparative military ranks), but it is often sub ...

John M. Langan took command. Later that month, it took part in the Battle of Champion Hill

The Battle of Champion Hill of May 16, 1863, was the pivotal battle in the Vicksburg Campaign of the American Civil War (1861–1865). Union Army commander Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant and the Army of the Tennessee pursued the retreating Confe ...

. On May 17, the battery was part of a Confederate force tasked with holding the crossing of the Big Black River at the Battle of Big Black River Bridge

The Battle of Big Black River Bridge was fought on May 17, 1863, as part of the Vicksburg Campaign of the American Civil War. After a Union army commanded by Major General Ulysses S. Grant defeated Lieutenant General John C. Pemberton's Confed ...

, where it may have suffered the capture of two cannon

A cannon is a large- caliber gun classified as a type of artillery, which usually launches a projectile using explosive chemical propellant. Gunpowder ("black powder") was the primary propellant before the invention of smokeless powder ...

s. Landis's Battery next saw action during the siege of Vicksburg

The siege of Vicksburg (May 18 – July 4, 1863) was the final major military action in the Vicksburg campaign of the American Civil War. In a series of maneuvers, Union Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant and his Army of the Tennessee crossed the Missis ...

. While there, the battery helped repulse Union assaults on May 22. Landis's Battery was captured when the Confederate garrison of Vicksburg Vicksburg most commonly refers to:

* Vicksburg, Mississippi, a city in western Mississippi, United States

* The Vicksburg Campaign, an American Civil War campaign

* The Siege of Vicksburg, an American Civil War battle

Vicksburg is also the name of ...

surrendered on July 4. Although the surviving men of the battery were exchanged, the battery was not reorganized after Vicksburg; instead, it was absorbed into Guibor's Missouri Battery along with Wade's Missouri Battery

Wade's Battery (later Walsh's Battery, also known as the 1st Light Battery) was an artillery battery in the Confederate States Army during the American Civil War. The battery was mustered into Confederate service on December 28, 1861; many of t ...

.

Background

In the United States during the early 19th century, a large cultural divide developed between the Northern States and the Southern States over the issue ofslavery

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

. By the time of the 1860 United States presidential election, slavery had become one of the defining features of southern culture, with the ideology of states' rights

In American political discourse, states' rights are political powers held for the state governments rather than the federal government according to the United States Constitution, reflecting especially the enumerated powers of Congress and the ...

being used to defend the institution. Eventually, many southerners decided that secession

Secession is the withdrawal of a group from a larger entity, especially a political entity, but also from any organization, union or military alliance. Some of the most famous and significant secessions have been: the former Soviet republics le ...

was the only way to preserve slavery, especially after abolitionist Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation thro ...

was elected president

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

*President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese ful ...

in 1860. His candidacy was regionally successful, as much of his support was from the Northern States; he received no electoral votes from the Deep South

The Deep South or the Lower South is a cultural and geographic subregion in the Southern United States. The term was first used to describe the states most dependent on plantations and slavery prior to the American Civil War. Following the war ...

. Many southerners rejected the legitimacy of Lincoln's election, and promoted secession. On December 20, 1860, the state of South Carolina

)''Animis opibusque parati'' ( for, , Latin, Prepared in mind and resources, links=no)

, anthem = " Carolina";" South Carolina On My Mind"

, Former = Province of South Carolina

, seat = Columbia

, LargestCity = Charleston

, LargestMetro = ...

seceded, and the states of Mississippi

Mississippi () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States, bordered to the north by Tennessee; to the east by Alabama; to the south by the Gulf of Mexico; to the southwest by Louisiana; and to the northwest by Arkansas. Miss ...

, Florida

Florida is a state located in the Southeastern region of the United States. Florida is bordered to the west by the Gulf of Mexico, to the northwest by Alabama, to the north by Georgia, to the east by the Bahamas and Atlantic Ocean, and to ...

, Alabama

(We dare defend our rights)

, anthem = "Alabama (state song), Alabama"

, image_map = Alabama in United States.svg

, seat = Montgomery, Alabama, Montgomery

, LargestCity = Huntsville, Alabama, Huntsville

, LargestCounty = Baldwin County, Al ...

, Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to the ...

, Louisiana

Louisiana , group=pronunciation (French: ''La Louisiane'') is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It is the 20th-smallest by area and the 25th most populous of the 50 U.S. states. Louisiana is borde ...

, and Texas

Texas (, ; Spanish language, Spanish: ''Texas'', ''Tejas'') is a state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States. At 268,596 square miles (695,662 km2), and with more than 29.1 million residents in 2 ...

followed suit in early 1861. On February 4, the seceding states formed the Confederate States of America

The Confederate States of America (CSA), commonly referred to as the Confederate States or the Confederacy was an unrecognized breakaway republic in the Southern United States that existed from February 8, 1861, to May 9, 1865. The Confeder ...

; Jefferson Davis

Jefferson F. Davis (June 3, 1808December 6, 1889) was an American politician who served as the president of the Confederate States from 1861 to 1865. He represented Mississippi in the United States Senate and the House of Representatives as a ...

became the nascent state's president

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

*President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese ful ...

.

In

In Charleston Harbor

The Charleston Harbor is an inlet (8 sq mi/20.7 km²) of the Atlantic Ocean at Charleston, South Carolina. The inlet is formed by the junction of Ashley and Cooper rivers at . Morris and Sullivan's Islands shelter the entrance. Charleston H ...

, South Carolina, the military installation of Fort Sumter

Fort Sumter is a sea fort built on an artificial island protecting Charleston, South Carolina from naval invasion. Its origin dates to the War of 1812 when the British invaded Washington by sea. It was still incomplete in 1861 when the Battl ...

was still held by a Union Army

During the American Civil War, the Union Army, also known as the Federal Army and the Northern Army, referring to the United States Army, was the land force that fought to preserve the Union (American Civil War), Union of the collective U.S. st ...

garrison. On the morning of April 12, the Confederates fired on Fort Sumter, beginning the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

. The fort surrendered the next day. Shortly after the attack, Lincoln requested that the states remaining in the Union provide 75,000 volunteers; in the coming weeks Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth ar ...

, North Carolina

North Carolina () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States. The state is the 28th largest and 9th-most populous of the United States. It is bordered by Virginia to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the east, Georgia and So ...

, Tennessee

Tennessee ( , ), officially the State of Tennessee, is a landlocked state in the Southeastern region of the United States. Tennessee is the 36th-largest by area and the 15th-most populous of the 50 states. It is bordered by Kentucky to th ...

, and Arkansas

Arkansas ( ) is a landlocked state in the South Central United States. It is bordered by Missouri to the north, Tennessee and Mississippi to the east, Louisiana to the south, and Texas and Oklahoma to the west. Its name is from the Osage ...

joined the Confederacy. A Union army commanded by Brigadier General

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointed ...

Irvin McDowell

Irvin McDowell (October 15, 1818 – May 4, 1885) was a career American army officer. He is best known for his defeat in the First Battle of Bull Run, the first large-scale battle of the American Civil War. In 1862, he was given command o ...

moved south into Virginia and attacked two Confederate armies commanded by Brigadier Generals P. G. T. Beauregard and Joseph E. Johnston

Joseph Eggleston Johnston (February 3, 1807 – March 21, 1891) was an American career army officer, serving with distinction in the United States Army during the Mexican–American War (1846–1848) and the Seminole Wars. After Virginia seceded ...

on July 21. In the ensuing First Battle of Bull Run

The First Battle of Bull Run (the name used by Union forces), also known as the Battle of First Manassas

, the Union army was rout

A rout is a panicked, disorderly and undisciplined retreat of troops from a battlefield, following a collapse in a given unit's command authority, unit cohesion and combat morale (''esprit de corps'').

History

Historically, lightly-equi ...

ed.

Meanwhile, the state of Missouri

Missouri is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. Ranking List of U.S. states and territories by area, 21st in land area, it is bordered by eight states (tied for the most with Tennessee ...

was politically divided. The state legislature voted against secession, but Governor

A governor is an administrative leader and head of a polity or political region, ranking under the head of state and in some cases, such as governors-general, as the head of state's official representative. Depending on the type of political ...

Claiborne F. Jackson

Claiborne Fox Jackson (April 4, 1806 – December 6, 1862) was an American politician of the Democratic Party in Missouri. He was elected as the 15th Governor of Missouri, serving from January 3, 1861, until July 31, 1861, when he was forc ...

supported it. Jackson decided to mobilize the state militia

A militia () is generally an army or some other fighting organization of non-professional soldiers, citizens of a country, or subjects of a state, who may perform military service during a time of need, as opposed to a professional force of r ...

to a point outside of St. Louis

St. Louis () is the second-largest city in Missouri, United States. It sits near the confluence of the Mississippi and the Missouri Rivers. In 2020, the city proper had a population of 301,578, while the bi-state metropolitan area, which e ...

, where the St. Louis Arsenal was located. Brigadier General Nathaniel Lyon

Nathaniel Lyon (July 14, 1818 – August 10, 1861) was the first Union general to be killed in the American Civil War. He is noted for his actions in Missouri in 1861, at the beginning of the conflict, to forestall secret secessionist plans of th ...

, the commander of the arsenal, moved to disperse the militiamen on May 10 in the Camp Jackson affair; a pro-secession riot

A riot is a form of civil disorder commonly characterized by a group lashing out in a violent public disturbance against authority, property, or people.

Riots typically involve destruction of property, public or private. The property targete ...

in St. Louis followed. In turn, Jackson created the Missouri State Guard

The Missouri State Guard (MSG) was a military force established by the Missouri General Assembly on May 11, 1861. While not a formation of the Confederate States Army, the Missouri State Guard fought alongside Confederate troops and, at various ...

as a new militia organization, appointing Major General Sterling Price

Major-General Sterling "Old Pap" Price (September 14, 1809 – September 29, 1867) was a senior officer of the Confederate States Army who commanded infantry in the Western and Trans-Mississippi theaters of the American Civil War. Prior to ...

as the organization's commander on May 12. After a June 11 meeting between Lyon, Jackson, Price, and United States Representative

The United States House of Representatives, often referred to as the House of Representatives, the U.S. House, or simply the House, is the lower chamber of the United States Congress, with the Senate being the upper chamber. Together they ...

Francis P. Blair Jr. failed to lead to a peaceable compromise, Lyon moved against the state capital of Jefferson City

Jefferson City, informally Jeff City, is the capital of Missouri, United States. It had a population of 43,228 at the 2020 census, ranking as the 15th most populous city in the state. It is also the county seat of Cole County and the principa ...

, ejecting Jackson and the pro-secession elements of the state legislature on June 15.

Two days later, the Missouri State Guard suffered another defeat at the hands of Lyon, this time at the Battle of Boonville

The First Battle of Boonville was a minor skirmish of the American Civil War, occurring on June 17, 1861, near Boonville in Cooper County, Missouri. Although casualties were extremely light, the battle's strategic impact was far greater than ...

, which led Jackson and Price to withdraw to southwestern Missouri. Lyon pursued, although a portion of his command, under Colonel

Colonel (abbreviated as Col., Col or COL) is a senior military officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, a colonel was typically in charge of ...

Franz Sigel

Franz Sigel (November 18, 1824 – August 21, 1902) was a German American military officer, revolutionary and immigrant to the United States who was a teacher, newspaperman, politician, and served as a Union major general in the American Civil W ...

, was defeated at the Battle of Carthage on July 5. Price was reinforced by Confederate States Army troops commanded by Brigadier General Benjamin McCulloch

Brigadier-General Benjamin McCulloch (November 11, 1811 – March 7, 1862) was a soldier in the Texas Revolution, a Texas Ranger, a major-general in the Texas militia and thereafter a major in the United States Army (United States Volunteers) ...

; the latter commanded the combined force. On August 10, Lyon attacked the Confederate camp near Wilsons Creek. Lyon's plan in the ensuing Battle of Wilson's Creek

The Battle of Wilson's Creek, also known as the Battle of Oak Hills, was the first major battle of the Trans-Mississippi Theater of the American Civil War. It was fought on August 10, 1861, near Springfield, Missouri, Springfield, Missou ...

was a pincer attack

The pincer movement, or double envelopment, is a military maneuver in which forces simultaneously attack both flanks (sides) of an enemy formation. This classic maneuver holds an important foothold throughout the history of warfare.

The pin ...

, with Lyon leading the main Union body to attack one side of the Confederate camp, and Sigel swinging a column around to attack the Confederate rear. The plan failed as Sigel was routed and Lyon was killed; the Union troops retreated all the way to Rolla after the defeat. Price followed up the Confederate victory at Wilson's Creek by driving north towards the Missouri River. On September 13, the Missouri State Guard encountered Union troops near Lexington; the city was soon placed under siege

A siege is a military blockade of a city, or fortress, with the intent of conquering by attrition warfare, attrition, or a well-prepared assault. This derives from la, sedere, lit=to sit. Siege warfare is a form of constant, low-intensity con ...

. The Union garrison surrendered on September 20, ending the siege of Lexington

The siege of Lexington, also known as the First Battle of Lexington or the Battle of the Hemp Bales, was a minor conflict of the American Civil War. The siege took place from September 13 to 20, 1861 between the Union Army and the pro- Confedera ...

. However, Major General John C. Frémont

John Charles Frémont or Fremont (January 21, 1813July 13, 1890) was an American explorer, military officer, and politician. He was a U.S. Senator from California and was the first Republican nominee for president of the United States in 1856 ...

concentrated Union troops near Tipton

Tipton is an industrial town in the West Midlands in England with a population of around 38,777 at the 2011 UK Census. It is located northwest of Birmingham.

Tipton was once one of the most heavily industrialised towns in the Black Country, w ...

, threatening Price's position. In turn, Price withdrew to Neosho in the southwestern part of the state. On November 3, Jackson and the pro-secession elements of the state legislature voted to secede and join the Confederate States of America as a government-in-exile

A government in exile (abbreviated as GiE) is a political group that claims to be a country or semi-sovereign state's legitimate government, but is unable to exercise legal power and instead resides in a foreign country. Governments in exile u ...

; the anti-secession elements of the legislature had voted against secession in July.

Service history

1862

Captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police department, election precinct, e ...

John C. Landis, formerly an officer in the Missouri State Guard, was authorized in December 1861 to recruit an artillery unit for official service in the Confederate States Army

The Confederate States Army, also called the Confederate Army or the Southern Army, was the military land force of the Confederate States of America (commonly referred to as the Confederacy) during the American Civil War (1861–1865), fighting ...

. Landis's recruiting operations were centered near Osceola, Missouri

Osceola is a city in St. Clair County, Missouri, United States. The population was 909 at the 2020 census. It is the county seat of St. Clair County. During the American Civil War, Osceola was the site of the Sacking of Osceola.

History

Located ...

, and the men recruited were former members of the Missouri State Guard. Despite not being able to enlist enough men to bring the battery to full strength, the unit traveled to Des Arc, Arkansas

Des Arc is a city on the White River in the Arkansas Delta, United States. It is the largest city in Prairie County, Arkansas, and the county seat for the county's northern district. Incorporated in 1854, Des Arc's position on the river has sha ...

in January 1862 to be equipped with cannons

A cannon is a large-caliber gun classified as a type of artillery, which usually launches a projectile using explosive chemical propellant. Gunpowder ("black powder") was the primary propellant before the invention of smokeless powder during ...

. The battery was assigned two 12-pounder Napoleon

The M1857 12-pounder Napoleon or Light 12-pounder gun or 12-pounder gun-howitzer was a bronze smoothbore muzzleloading artillery piece that was adopted by the United States Army in 1857 and extensively employed in the American Civil War. The gun ...

field gun

A field gun is a field artillery piece. Originally the term referred to smaller guns that could accompany a field army on the march, that when in combat could be moved about the battlefield in response to changing circumstances ( field artille ...

s and two 24-pounder howitzers; all four cannons were made of brass

Brass is an alloy of copper (Cu) and zinc (Zn), in proportions which can be varied to achieve different mechanical, electrical, and chemical properties. It is a substitutional alloy: atoms of the two constituents may replace each other with ...

. The unit joined the Army of the West in March 1862 after the Battle of Pea Ridge

The Battle of Pea Ridge (March 7–8, 1862), also known as the Battle of Elkhorn Tavern, took place in the American Civil War near Leetown, northeast of Fayetteville, Arkansas. Federal forces, led by Brig. Gen. Samuel R. Curtis, moved south ...

; more men joined the unit afterwards. Archaeological evidence suggests at least a portion of the battery may have been engaged at Pea Ridge, as part of a cannonball

A round shot (also called solid shot or simply ball) is a solid spherical projectile without explosive charge, launched from a gun. Its diameter is slightly less than the bore of the barrel from which it is shot. A round shot fired from a lar ...

that could have been fired only from a 24-pounder howitzer was recovered at Pea Ridge National Military Park

Pea Ridge National Military Park is a United States National Military Park located in northwest Arkansas near the Missouri border. The park protects the site of the Battle of Pea Ridge, fought March 7 and 8, 1862. The battle was a victory for th ...

in 2001. As Landis's Battery was the only Confederate artillery battery armed with 24-pounder howitzers to serve west of the Mississippi River, this would likely indicate that at least a portion of the battery participated in the fighting, likely as part of Brigadier General William Y. Slack

William Yarnel Slack (August 1, 1816 – March 21, 1862) was an American lawyer, politician, and military officer who fought for the Confederate States of America during the American Civil War. Born in Kentucky, Slack moved to Missouri as a c ...

's brigade. However, other sources indicate that the battery did not see action in the battle. Around this time, the battery was assigned to Brigadier General

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointed ...

Daniel M. Frost

Daniel Marsh Frost (August 9, 1823 – October 29, 1900) was a former United States Army officer who became a brigadier general in the Missouri Volunteer Militia (MVM) and the Confederate States Army during the American Civil War. Among the han ...

's artillery brigade

An artillery brigade is a specialised form of military brigade dedicated to providing artillery support. Other brigades might have an artillery component, but an artillery brigade is a brigade dedicated to artillery and relying on other units fo ...

and followed the rest of the Army of the West across the Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson Bay drainage system. From its traditional source of Lake Itasca in northern Minnesota, it f ...

in mid-April.

On May 1, while stationed in the vicinity of Memphis, Tennessee

Memphis is a city in the U.S. state of Tennessee. It is the seat of Shelby County in the southwest part of the state; it is situated along the Mississippi River. With a population of 633,104 at the 2020 U.S. census, Memphis is the second-mos ...

, the battery officially elected its officers. A muster conducted on May5 at Corinth, Mississippi

Corinth is a city in and the county seat of Alcorn County, Mississippi, Alcorn County, Mississippi, United States. The population was 14,573 at the 2010 census. Its ZIP codes are 38834 and 38835. It lies on the state line with Tennessee.

Histor ...

, found 62 men in the battery; it also noted that the battery was armed with four cannons. Union troops had previously occupied positions near the city on May 3, beginning the siege of Corinth

The siege of Corinth (also known as the first Battle of Corinth) was an American Civil War engagement lasting from April 29 to May 30, 1862, in Corinth, Mississippi. A collection of Union forces under the overall command of Major General Henry ...

. During the siege, Landis's Battery held a strong redoubt

A redoubt (historically redout) is a fort or fort system usually consisting of an enclosed defensive emplacement outside a larger fort, usually relying on earthworks, although some are constructed of stone or brick. It is meant to protect soldi ...

with its four cannons, dueling with Union batteries at a range of . The battery also fought in a skirmish in the vicinity on May 28 before the Confederates abandoned the city on the night of May 29/30. Landis's Battery then spent the next several months stationed at various points in Mississippi. In September 1862, Price, now commanding the Army of the West, was preparing for an offensive designed to support the Confederate Heartland Offensive

The Confederate Heartland Offensive (August 14 – October 10, 1862), also known as the Kentucky Campaign, was an American Civil War campaign conducted by the Confederate States Army in Tennessee and Kentucky where Generals Braxton Bragg and ...

. On September 14, Price occupied Iuka, Mississippi

Iuka is a city in and the county seat of Tishomingo County, Mississippi, United States. Its population was 3,028 at the 2010 census. Woodall Mountain, the highest point in Mississippi, is located just south of Iuka.

History

Iuka is built on t ...

, as part of his movement; additional Confederate forces under the command of Major General Earl Van Dorn

Earl Van Dorn (September 17, 1820May 7, 1863) started his military career as a United States Army officer but joined Confederate forces in 1861 after the Civil War broke out. He was a major general when he was killed in a private conflict.

A g ...

were only a four-days' march away. Major General Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant ; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was an American military officer and politician who served as the 18th president of the United States from 1869 to 1877. As Commanding General, he led the Union Ar ...

, one of the top Union commanders in the region, wanted to avoid the possibility of Price and Van Dorn joining forces. To accomplish this goal, Grant sent troops commanded by Major General E. O. C. Ord to attack Iuka from the north, and others under Major General William Rosecrans

William Starke Rosecrans (September 6, 1819March 11, 1898) was an American inventor, coal-oil company executive, diplomat, politician, and U.S. Army officer. He gained fame for his role as a Union general during the American Civil War. He was t ...

to attack the city from the south. During the ensuing Battle of Iuka

A battle is an occurrence of combat in warfare between opposing military units of any number or size. A war usually consists of multiple battles. In general, a battle is a military engagement that is well defined in duration, area, and force ...

on September 19, Landis's Battery fought as part of Brigadier General Martin E. Green

Martin Edwin Green (June 3, 1815 – June 27, 1863) was a Confederate brigadier general in the American Civil War, and a key organizer of the Missouri State Guard in northern Missouri.

Early life

Green was born in Fauquier County, Virginia. ...

's brigade, assigned to Brigadier General Lewis Henry Little

Lewis Henry Little (March 19, 1817 – September 19, 1862) was a career United States Army officer and a Confederate brigadier general during the American Civil War. He served mainly in the Western Theater and was killed in action during the ...

's division of the Army of the West. Although the battery came under hostile fire at Iuka, it did not fire its cannons. Price was able to fend off Rosecrans, and an acoustic shadow An acoustic shadow or sound shadow is an area through which sound waves fail to propagate, due to topographical obstructions or disruption of the waves via phenomena such as wind currents, buildings, or sound barriers.

Short-distance acoustic shad ...

prevented Ord from learning of the fight until after it was over. By September 20, the Army of the West had escaped from Iuka.

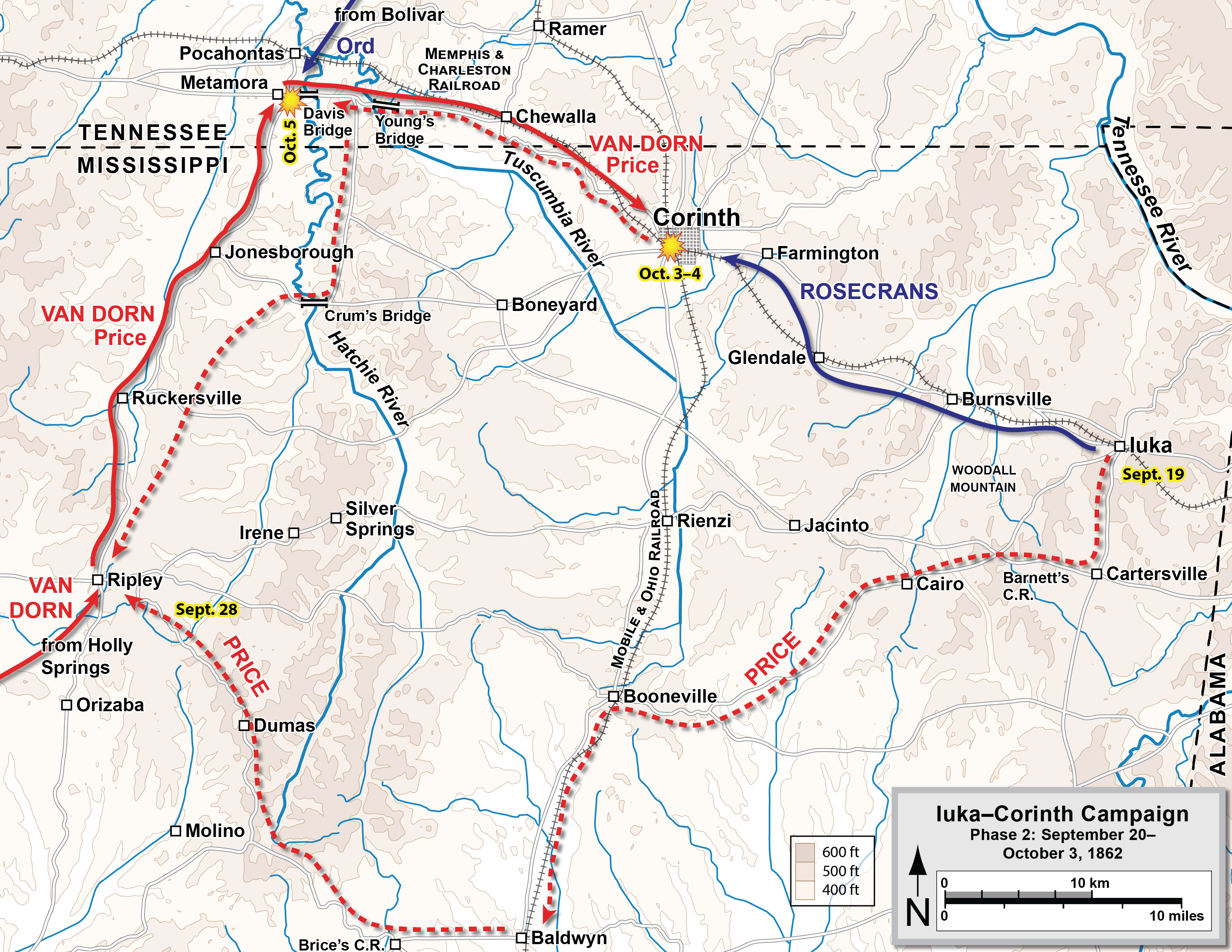

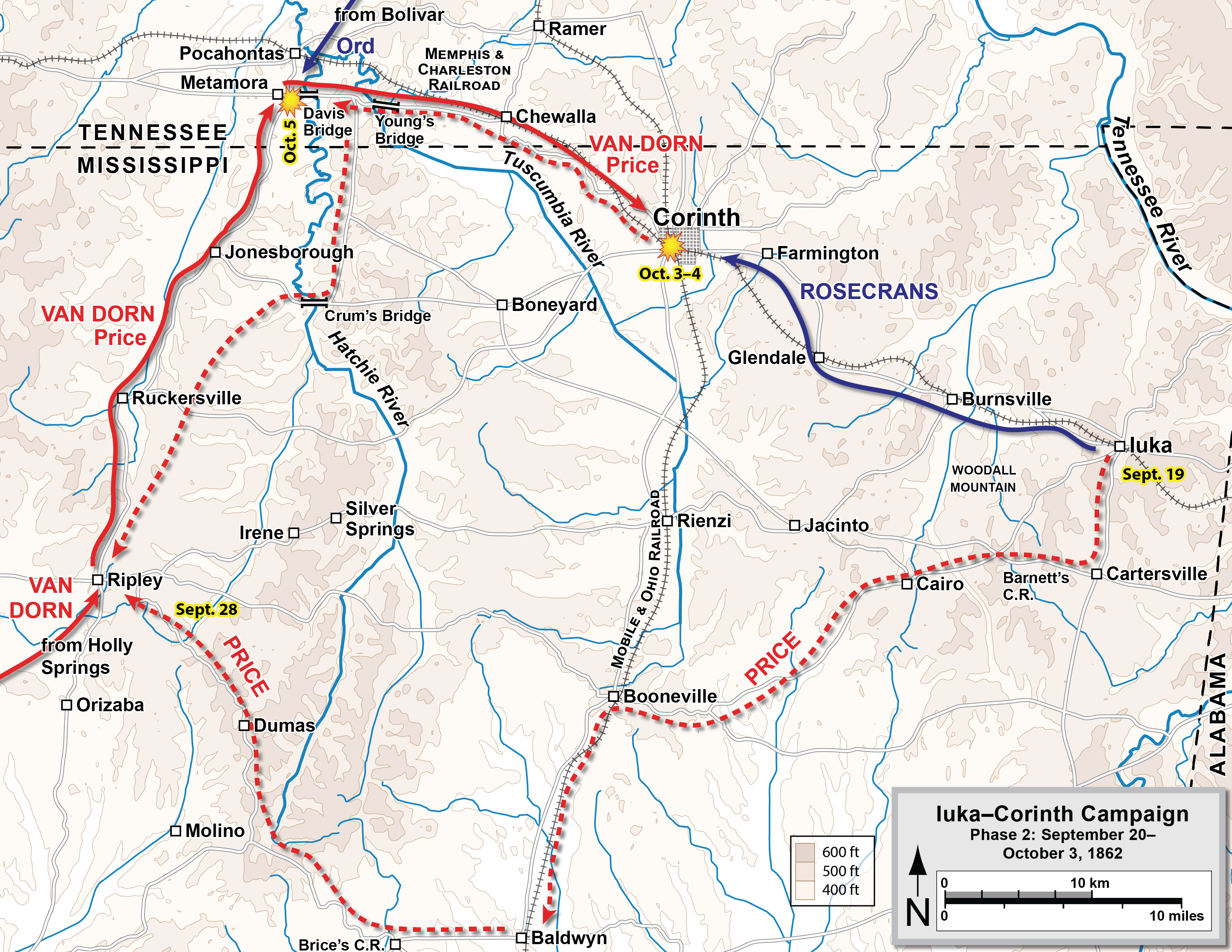

Price and Van Dorn then joined forces; Van Dorn commanded the combined army, as he had seniority

Seniority is the state of being older or placed in a higher position of status relative to another individual, group, or organization. For example, one employee may be senior to another either by role or rank (such as a CEO vice a manager), or by ...

over Price, who was relegated to corps command. Rosecrans responded to the Confederate consolidation by moving his army to Corinth on October 2. The Union position at Corinth consisted of an exterior line of fortifications built by the Confederates earlier in the war and a new inner line built as the result of orders by Major General Henry Halleck

Henry Wager Halleck (January 16, 1815 – January 9, 1872) was a senior United States Army officer, scholar, and lawyer. A noted expert in military studies, he was known by a nickname that became derogatory: "Old Brains". He was an important par ...

. On October 3, Van Dorn attacked, beginning the Second Battle of Corinth

The second Battle of Corinth (which, in the context of the American Civil War, is usually referred to as the Battle of Corinth, to differentiate it from the siege of Corinth earlier the same year) was fought October 3–4, 1862, in Corinth, M ...

. Landis's Battery was part of Green's brigade of Brigadier General Louis Hébert

Louis Hébert (c. 1575 – 25 January 1627) is widely considered the first European apothecary in the region that would later become Canada, as well as the first European to farm in said region. He was born around 1575 at 129 de la rue Saint ...

's division of Price's corps during the battle. During the battle, Landis's Battery continued to operate two 12-pounders and two 24-pounders. On the first day at Corinth, Landis's Battery, as well as Guibor's Missouri Battery, participated in an artillery duel with two Union batteries from the 1st Missouri Light Artillery: Battery I and Battery K. After two more Confederate artillery batteries joined the fighting, the Union artillery was forced to withdraw, allowing the infantry

Infantry is a military specialization which engages in ground combat on foot. Infantry generally consists of light infantry, mountain infantry, motorized infantry & mechanized infantry, airborne infantry, air assault infantry, and marine i ...

of Green's brigade to attack the Union line. Later that day, while the Confederate infantry was still fighting along the Union main line, Union infantry approached the Confederate flank, and advanced towards Landis's and Guibor's batteries. Artillery fire from the two batteries stopped the progress of the Union advance, and the Union infantry withdrew as darkness began to fall.

The Confederate infantry assaults on October3 had driven Rosecrans's men from the outer line, but the inner line was still in Union hands. That night, Landis's Battery fired at the interior Union lines, as the battery's guns had a longer effective range than most of the other Confederate artillery. Van Dorn then ordered another assault the next day. The October4 fighting briefly carried portions of the inner Union line, but the gains could not be held. The Confederates withdrew from Corinth that night in defeat. Landis's Battery suffered ten casualties at Corinth. The unit formed part of the Confederate rear guard

A rearguard is a part of a military force that protects it from attack from the rear, either during an advance or withdrawal. The term can also be used to describe forces protecting lines, such as communication lines, behind an army. Even more ...

, avoiding capture at the Battle of Davis Bridge. The battery's equipment had been damaged during the Corinth campaign, so the unit was detached to Jackson, Mississippi

Jackson, officially the City of Jackson, is the Capital city, capital of and the List of municipalities in Mississippi, most populous city in the U.S. state of Mississippi. The city is also one of two county seats of Hinds County, Mississippi, ...

, for repairs. On November 29, Landis's men rejoined the Army of the West and they spent the rest of 1862 at Grenada, Mississippi

Grenada is a city in Grenada County, Mississippi, Grenada County, Mississippi, United States. The population was 13,092 at the United States Census, 2010, 2010 census. It is the county seat of Grenada County, Mississippi, Grenada County.

History

...

.

1863

On January 27, 1863, the battery was transferred toGrand Gulf, Mississippi

Grand Gulf is a ghost town in Claiborne County, Mississippi, United States.

History

Grand Gulf was named for the large whirlpool, (or gulf), formed by the Mississippi River flowing against a large rocky bluff. La Salle and Zadok Cramer commente ...

, joining the defenses on the Big Black River. While stationed at Grand Gulf, the battery participated in several minor engagements with Union gunboat

A gunboat is a naval watercraft designed for the express purpose of carrying one or more guns to bombard coastal targets, as opposed to those military craft designed for naval warfare, or for ferrying troops or supplies.

History Pre-steam ...

s, although some of the artillerymen reported boredom. In mid-March, the battery guarded a point known as Winkler's Bluff on the Big Black River, with orders to allow no boats to pass the point. On April 29, Union Navy

), (official)

, colors = Blue and gold

, colors_label = Colors

, march =

, mascot =

, equipment =

, equipment_label ...

vessels commanded by Admiral

Admiral is one of the highest ranks in some navies. In the Commonwealth nations and the United States, a "full" admiral is equivalent to a "full" general in the army or the air force, and is above vice admiral and below admiral of the fleet, ...

David Dixon Porter

David Dixon Porter (June 8, 1813 – February 13, 1891) was a United States Navy admiral and a member of one of the most distinguished families in the history of the U.S. Navy. Promoted as the second U.S. Navy officer ever to attain the rank o ...

bombarded the Confederate position at Grand Gulf, resulting in the Battle of Grand Gulf

The Battle of Grand Gulf was fought on April 29, 1863, during the American Civil War. As part of Major General Ulysses S. Grant's Vicksburg campaign, seven Union Navy ironclad warships commanded by Admiral David Dixon Porter bombarded Confederat ...

, although Landis's Battery was not part of the Confederate front line. One fort held out, so Grant landed 24,000 men downriver at Bruinsburg. These men soon moved east from the river, leading Brigadier General John S. Bowen

John Stevens Bowen (October 30, 1830 – July 13, 1863) was a career United States Army officer who later became a general in the Confederate Army and a commander in the Western Theater of the American Civil War. He fought at the battles ...

, the Confederate commander at Grand Gulf, to send a blocking force to Port Gibson

Port Gibson is a city in Claiborne County, Mississippi, United States. The population was 1,567 at the 2010 census. Port Gibson is the county seat of Claiborne County, which is bordered on the west by the Mississippi River. It is the site of th ...

in an attempt to stop Grant's incursion. During the morning of May 1, Landis's Battery's two howitzers and their crews were sent to join the blocking force. During the Battle of Port Gibson

The Battle of Port Gibson was fought near Port Gibson, Mississippi, on May 1, 1863, between Union and Confederate forces during the Vicksburg Campaign of the American Civil War. The Union Army was led by Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, and was victo ...

, the battery fired at men of Major General John McClernand

John Alexander McClernand (May 30, 1812 – September 20, 1900) was an American lawyer and politician, and a Union Army general in the American Civil War. He was a prominent Democratic politician in Illinois and a member of the United States H ...

's Union corps and engaged in an artillery duel with the 8th Michigan Light Artillery; the unit suffered three casualties during the fighting and did not disengage until the late afternoon. At one point in the battle, the battery was also subjected to Union sharpshooter

A sharpshooter is one who is highly proficient at firing firearms or other projectile weapons accurately. Military units composed of sharpshooters were important factors in 19th-century combat. Along with "marksman" and "expert", "sharpshooter" i ...

fire, before dispersing their attackers with canister. Despite holding initially, Union pressure eventually drove in Bowen's right, causing the Confederates to retreat before Grant outflanked them. After Port Gibson, the Confederates were forced to abandon their position at Grand Gulf on May 3; Landis's Battery again served as part of a rear guard.

Meanwhile, Grant was faced with a choice: he could approach Vicksburg Vicksburg most commonly refers to:

* Vicksburg, Mississippi, a city in western Mississippi, United States

* The Vicksburg Campaign, an American Civil War campaign

* The Siege of Vicksburg, an American Civil War battle

Vicksburg is also the name of ...

from either the south or the east. An attack from the south presented a more direct path to the city, but an advance from the east presented the better chance of a complete envelopment of Lieutenant General

Lieutenant general (Lt Gen, LTG and similar) is a three-star military rank (NATO code OF-8) used in many countries. The rank traces its origins to the Middle Ages, where the title of lieutenant general was held by the second-in-command on the ...

John C. Pemberton

John Clifford Pemberton (August 10, 1814 – July 13, 1881) was a career United States Army officer who fought in the Seminole Wars and with distinction during the Mexican–American War. He resigned his commission to serve as a Confederate Stat ...

's garrison at Vicksburg, so Grant decided on the latter route. On May 12, Union troops brushed aside Confederate resistance at the Battle of Raymond

The Battle of Raymond was fought on May 12, 1863, near Raymond, Mississippi, during the Vicksburg campaign of the American Civil War. Initial Union (American Civil War), Union attempts to capture the strategically important Mississippi River cit ...

before moving against Jackson, where Confederate General

A general officer is an Officer (armed forces), officer of highest military ranks, high rank in the army, armies, and in some nations' air forces, space forces, and marines or naval infantry.

In some usages the term "general officer" refers t ...

Joseph E. Johnston was positioned with 6,000 men. Grant attacked the city on May 14, and a Union victory in the ensuing Battle of Jackson forced Johnston out of the city, preventing him from reinforcing Pemberton. In turn, Johnston ordered Pemberton to move east and take the offensive. On May 16, Confederate Brigadier General Stephen D. Lee

Stephen Dill Lee (September 22, 1833 – May 28, 1908) was an American officer in the Confederate Army, politician and first president of Mississippi State University from 1880 to 1899. He served as lieutenant general of the Confederate ...

encountered elements of Grant's army during the move east, beginning the Battle of Champion Hill

The Battle of Champion Hill of May 16, 1863, was the pivotal battle in the Vicksburg Campaign of the American Civil War (1861–1865). Union Army commander Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant and the Army of the Tennessee pursued the retreating Confe ...

. During the battle, Landis's Battery provided artillery support for the Confederate center. By this time, Lieutenant

A lieutenant ( , ; abbreviated Lt., Lt, LT, Lieut and similar) is a commissioned officer rank in the armed forces of many nations.

The meaning of lieutenant differs in different militaries (see comparative military ranks), but it is often sub ...

John M. Langan had replaced Landis as battery commander, after the latter became divisional artillery commander within Bowen's Division. The infantrymen of Bowen's Division made a strong attack against the Union line, and some of the Confederate artillery, including Landis's Battery, moved forward to support the charge. As Bowen's men were deploying, Landis's and Wade's Batteries fired on Union skirmisher

Skirmishers are light infantry or light cavalry soldiers deployed as a vanguard, flank guard or rearguard to screen a tactical position or a larger body of friendly troops from enemy advances. They are usually deployed in a skirmish line, an i ...

s, temporarily dispersing them. The 17th Ohio Battery then arrived on the field, and began firing on the Confederate batteries. Landis's and Wade's guns lacked the range to effectively return fire, and the Ohioans had the better of the exchange, as Landis's two howitzers were disabled. When Bowen's attack was forced back, Landis's Battery moved forward to provide covering fire, expending all its ammunition. At one point, Landis ordered the men to fire a shell in the path of a retreating Confederate regiment in an attempt to force the men to rally. At Champion Hill, Landis's Battery suffered either five or nine casualties. Four of the losses were inflicted by a single shell

Shell may refer to:

Architecture and design

* Shell (structure), a thin structure

** Concrete shell, a thin shell of concrete, usually with no interior columns or exterior buttresses

** Thin-shell structure

Science Biology

* Seashell, a hard ou ...

fired by the 17th Ohio Battery. Pemberton's entire army retreated from the field later that day. A Confederate division commanded by Major General William W. Loring

William Wing Loring (December 4, 1818 – December 30, 1886) was an American soldier who served in the armies of the United States, the Confederacy, and Egypt.

Biography

Early life

William was born in Wilmington, North Carolina, to Reuben a ...

had become separated from the rest of the Confederate force during the retreat, leading Pemberton to order Bowen's division and a brigade commanded by Brigadier General John C. Vaughn

John Crawford Vaughn (February 24, 1824 – September 10, 1875) was a Confederate cavalry officer from East Tennessee. He served in the Mexican–American War, prospected in the California Gold Rush, and participated in American Civil War batt ...

to hold the crossing of the Big Black River in hopes that Loring could rejoin the main Confederate force.

The next day, the battery was present at the Battle of Big Black River Bridge

The Battle of Big Black River Bridge was fought on May 17, 1863, as part of the Vicksburg Campaign of the American Civil War. After a Union army commanded by Major General Ulysses S. Grant defeated Lieutenant General John C. Pemberton's Confed ...

. The unit's exact placement during the fight is variously reported. The historian Philip Thomas Tucker reports that a portion of the battery was assigned to the Confederate front line, and the rest on the far side of the river. Tucker then states that when the Confederate line was broken by a Union assault, that front line portion of the battery lost its cannons, as the battery's horses had been sent to the other side of the Big Black River. Other sources say the battery was positioned entirely on the far side of the river. The historian James McGhee says the two pieces damaged at Champion Hill were not present at this action. Either way, the portion of the battery across the river helped cover the Confederate retreat, and entered the fortifications of Vicksburg. During the siege of Vicksburg

The siege of Vicksburg (May 18 – July 4, 1863) was the final major military action in the Vicksburg campaign of the American Civil War. In a series of maneuvers, Union Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant and his Army of the Tennessee crossed the Missis ...

, some of the artillerymen served as sharpshooters due to a shortage of cannons. On May 22, the battery helped repulse Union attacks, at one point using double-shotted

Naval artillery is artillery mounted on a warship, originally used only for naval warfare and then subsequently used for naval gunfire support, shore bombardment and anti-aircraft roles. The term generally refers to tube-launched projectile-firi ...

ammunition. Over the course of the siege, the unit suffered either ten or thirteen casualties during a 47-day span of mostly continuous fighting. The Confederates surrendered Vicksburg on July 4, and Landis's Battery was captured at this time. The 37 men left in the battery were released on parole

Parole (also known as provisional release or supervised release) is a form of early release of a prison inmate where the prisoner agrees to abide by certain behavioral conditions, including checking-in with their designated parole officers, or ...

until they were exchanged; they were also ordered to Demopolis, Alabama

Demopolis is the largest city in Marengo County, in west-central Alabama. The population was 7,162 at the time of the 2020 United States census, down from 7,483 at the 2010 census.

The city lies at the confluence of the Black Warrior River and T ...

. On October 1, Landis's Battery and Wade's Missouri Battery

Wade's Battery (later Walsh's Battery, also known as the 1st Light Battery) was an artillery battery in the Confederate States Army during the American Civil War. The battery was mustered into Confederate service on December 28, 1861; many of t ...

were absorbed by Guibor's Battery; Landis's Battery ceased to exist as a separate unit. About 75 men served with the battery throughout the war. The unit reported the deaths of 22 of its members. Of these, fifteen were the result of battle, while six died from disease and one member of the battery was murdered.

See also

*List of Missouri Confederate Civil War units

This is a list of Missouri Confederate Civil War units, or military units from the state of Missouri which fought for the Confederacy in the American Civil War. A border state with both southern and northern influences, Missouri attempted to r ...

Notes

References

Sources

* * * * * * * * * * * * * *External links

* {{featured article Units and formations of the Confederate States Army from Missouri 1862 establishments in Missouri Artillery units and formations of the American Civil War 1863 disestablishments in Alabama Military units and formations disestablished in 1863 Military units and formations established in 1862