Laco Novomeský on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

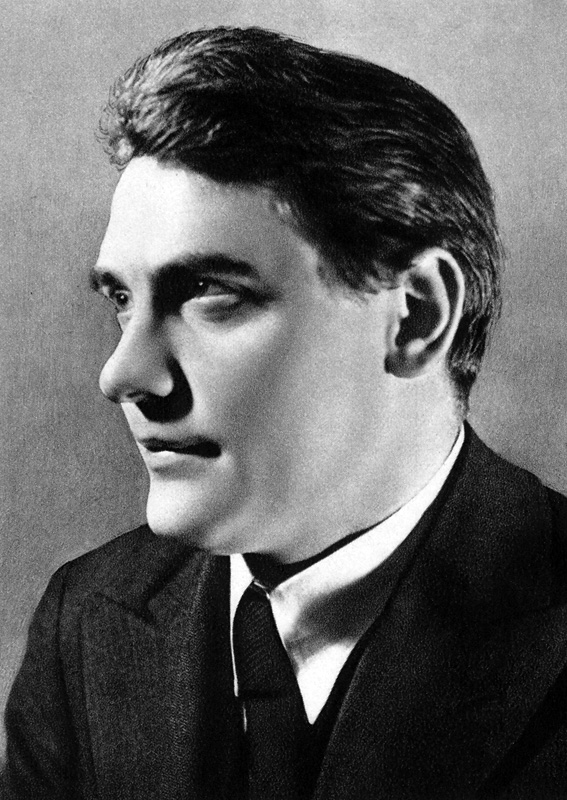

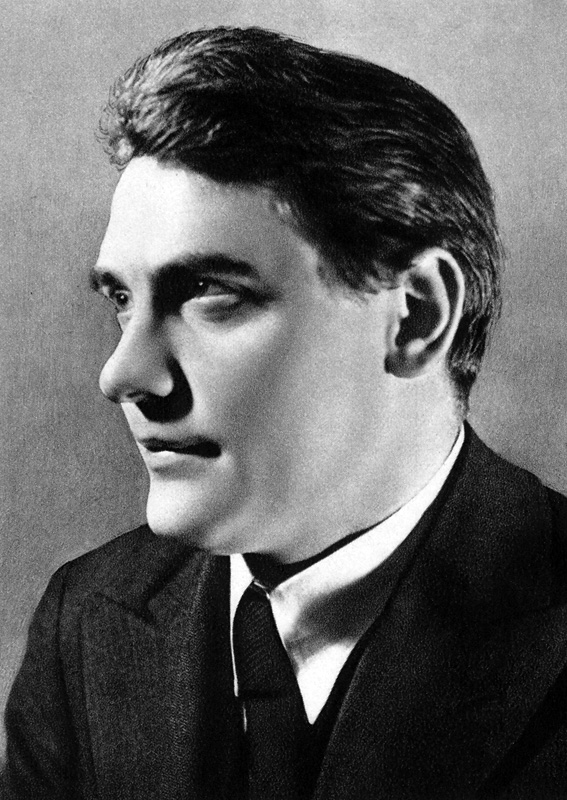

Laco Novomeský (full name: Ladislav Novomeský) (27 December 1904,

Laco Novomeský (full name: Ladislav Novomeský) (27 December 1904,

Laco Novomeský (full name: Ladislav Novomeský) (27 December 1904,

Laco Novomeský (full name: Ladislav Novomeský) (27 December 1904, Budapest

Budapest (, ; ) is the capital and most populous city of Hungary. It is the ninth-largest city in the European Union by population within city limits and the second-largest city on the Danube river; the city has an estimated population ...

— 4 September 1976, Bratislava

Bratislava (, also ; ; german: Preßburg/Pressburg ; hu, Pozsony) is the Capital city, capital and largest city of Slovakia. Officially, the population of the city is about 475,000; however, it is estimated to be more than 660,000 — approxim ...

) was a Slovak poet, writer, publicist and communist

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, a s ...

politician. Novomeský was a member of the DAV group; after The Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

he was commissioner of education and culture of Socialist Czechoslovakia. A prominent Czechoslovak politician, he was persecuted in the 1950s and later rehabilitated in the 1960s.

Early life

Novomeský was born in to the family of a tailor that immigrated fromSenica

Senica (; german: Senitz; hu, Szenice) is a town in Trnava Region, western Slovakia. It is located in the north-eastern part of the Záhorie lowland, close to the Little Carpathians.

Etymology

The name is derived from the word ''seno'' (" hay" ...

to Budapest, where he was born. The family moved back to Senica to continue his studies. He later graduated from the teacher training institute in Modra

Modra (german: Modern, hu, Modor, Latin: ''Modur'') is a city and municipality in the Bratislava Region in Slovakia. It has a population of 9,042 as of 2018. It nestles in the foothills of the Malé Karpaty (Little Carpathian mountains) and i ...

. Novomeský started to work as a teacher while at the same time enrolling as an external student of the Faculty of Arts at the Comenius University

Comenius University in Bratislava ( sk, Univerzita Komenského v Bratislave) is the largest university in Slovakia, with most of its faculties located in Bratislava. It was founded in 1919, shortly after the creation of Czechoslovakia. It is name ...

where he became involved in literary and political activities.

Literary and political career

He joined theCommunist Party of Czechoslovakia

The Communist Party of Czechoslovakia (Czech and Slovak: ''Komunistická strana Československa'', KSČ) was a communist and Marxist–Leninist political party in Czechoslovakia that existed between 1921 and 1992. It was a member of the Cominte ...

in 1925 and worked for its press. He was the editor of the Communist Party's newspaper Pravda

''Pravda'' ( rus, Правда, p=ˈpravdə, a=Ru-правда.ogg, "Truth") is a Russian broadsheet newspaper, and was the official newspaper of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, when it was one of the most influential papers in the co ...

(previously it was named the Truth of Poverty).

In 1927 he was arrested by the Czechoslovak authorities for press offence and sentenced to 10 years in prison however he was released by bail.

He went to Prague and joined the group of left-wing intellectuals around the ''DAV'' magazine.

The members of '' DAV'' also had influence in the ''Youth Club'' (sk. ''Klub mladých''), which joined to the ''Art discussion club of Slovakia'' (sk. ''Umelecká beseda''), which together with the DAV organized book-reading parties with poetry of important Slovak writers like Lukáč, Smrek, Novomeský and Okáli. DAV supported internationalism

Internationalism may refer to:

* Cosmopolitanism, the view that all human ethnic groups belong to a single community based on a shared morality as opposed to communitarianism, patriotism and nationalism

* International Style, a major architectur ...

on the one hand, and too equality between Slovaks

The Slovaks ( sk, Slováci, singular: ''Slovák'', feminine: ''Slovenka'', plural: ''Slovenky'') are a West Slavic ethnic group and nation native to Slovakia who share a common ancestry, culture, history and speak Slovak.

In Slovakia, 4.4 mi ...

and Czechs

The Czechs ( cs, Češi, ; singular Czech, masculine: ''Čech'' , singular feminine: ''Češka'' ), or the Czech people (), are a West Slavic ethnic group and a nation native to the Czech Republic in Central Europe, who share a common ancestry, c ...

. The concept of DAV connected the political line on the one hand, and the aesthetic

Aesthetics, or esthetics, is a branch of philosophy that deals with the nature of beauty and taste, as well as the philosophy of art (its own area of philosophy that comes out of aesthetics). It examines aesthetic values, often expressed th ...

line on the other hand. After the ban on the DAV project (by representatives of the new Slovak state

Slovak may refer to:

* Something from, related to, or belonging to Slovakia (''Slovenská republika'')

* Slovaks, a Western Slavic ethnic group

* Slovak language, an Indo-European language that belongs to the West Slavic languages

* Slovak, Arka ...

), individual members ( Urx, Novomeský, Husák, Clementis) participated in the organization of the Slovak National Uprising 1944 (Eduard Urx was even executed by the Nazis; Gustav Husak was one of the most important organizers of the Slovak National Uprising 1944). Ex-DAV members, Husák, Okáli, Clementis and Novomeský became part of the government in exile (in London) and after the end of the war they took part in taking power.

Novomeský rejected the Manifesto of the Seven The Manifesto of the Seven ( cs, Manifest sedmi) was a protest by seven artists against the Bolshevization of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia (KSČ), after its 5th Congress in 1929. The text was written on the initiative of Ivan OlbrachtLexico ...

and supported Klement Gottwald

Klement Gottwald (; 23 November 1896 – 14 March 1953) was a Czech communist politician, who was the leader of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia from 1929 until his death in 1953–titled as general secretary until 1945 and as chairman from ...

and the Sovietisation of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia. He wrote against the seven left-wing intellectuals and called for the intellectual left to support the new Party line by saying "The intellectual left cannot stand above the party".

In 1936, the Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War ( es, Guerra Civil Española)) or The Revolution ( es, La Revolución, link=no) among Nationalists, the Fourth Carlist War ( es, Cuarta Guerra Carlista, link=no) among Carlists, and The Rebellion ( es, La Rebelión, lin ...

broke out against general Franco

Francisco Franco Bahamonde (; 4 December 1892 – 20 November 1975) was a Spanish general who led the Nationalist forces in overthrowing the Second Spanish Republic during the Spanish Civil War and thereafter ruled over Spain from 193 ...

's insurgency, in which Novomeský became involved in Czechoslovakia by organizing International Brigades

The International Brigades ( es, Brigadas Internacionales) were military units set up by the Communist International to assist the Popular Front government of the Second Spanish Republic during the Spanish Civil War. The organization existed f ...

(he also founded the ''Club of Friends of Spain''). A year later, he participated in the congress in Paris and became a direct participant in the fighting (he got directly to the Czechoslovak combat units fighting the fascists) and the congress of the International Association of Writers for the Defense of Culture in Valencia, Barcelona and Madrid. Many of his memoirs about the Civil War were later published.

In 1939 he moved back to Slovakia and continued his communist activities despite the ban of the Party. In August 1943, together with his younger friend Gustav Husák, he became a member of the 5th illegal leadership of the Communist Party of Slovakia, led by Karol Šmidke

Karol Šmidke (January 21, 1897, Vítkovice (Ostrava), Austria-Hungary – December 15, 1952, Czechoslovakia) was a Slovak Communist politician, member of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia.

Smidke was Co- President of the Presidium of the Slo ...

. He was one of the leading organizers of the Slovak National uprising

The Slovak National Uprising ( sk, Slovenské národné povstanie, abbreviated SNP) was a military uprising organized by the Slovak resistance movement during World War II. This resistance movement was represented mainly by the members of the ...

. He was also a co-founder and vice-chairman of the insurgent Slovak National Council in 1943 which later became the highest legislative and executive body in socialist Slovakia.

In the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic

After the war he became a member of theCentral committee

Central committee is the common designation of a standing administrative body of Communist party, communist parties, analogous to a board of directors, of both ruling and nonruling parties of former and existing socialist states. In such party org ...

of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia and the Commissioner of Education from 1945 to 1950 as well as a member of the Constituent National Assembly.

At the congress of the Communist Party of Slovakia in 1950, he was accused of 'bourgeois nationalism' and was arrested on 6 February 1951, together with Gustav Husák. In 1954 he was sentenced to 10 years in prison in a staged trial with a subversive group of bourgeois nationalists. While Gustáv Husák was not completely broken in custody and tried to oppose the investigators, Novomeský and other accusers cooperated with the security forces and confessed to all the fabricated points. He could not publish at this time. In prison, he wrote 4,000 poems on tobacco papers, but smoked most of them. On 22 December 1955 he was released on parole. Zolo Mikeš wrote (Aktuality.sk) Novomeský's statements were used in the Slánsky trial against his friend Vladimir Clementis, thus contributing to his death sentence.

Novomeský then lived in Prague and was not allowed to return to Bratislava and was under police supervision. Then, until 1962, he worked at the Monument of National Literature in Prague. In 1963, Novomeský was fully rehabilitated. He moved to Bratislava, where he worked at the ''Institute of Slovak Literature of the'' Slovak Academy of Sciences. After the Warsaw Pact invasion on 21 August 1968, he again became a member of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia, and in the same year he also chaired the Matica slovenská

Matica Slovenská (en. Slovak Matica) is a Slovakia, Slovak national, Culture, cultural and scientific organization headquartered in Martin, Slovakia. It was founded in 1863 and revived in 1919. The organisation has facilities in the Slovaki ...

. In 1970, he resigned from the Central Committee of the Party and soon became seriously ill. In July 1970, a stroke completely removed him from social life. Opinions therefore differ as to whether, at least initially, he contributed to the so-called Husák's "normalization

Normalization or normalisation refers to a process that makes something more normal or regular. Most commonly it refers to:

* Normalization (sociology) or social normalization, the process through which ideas and behaviors that may fall outside of ...

" In the cultural and political field.

He died on 4 September 1976 in Bratislava.

Works

Poetry

* ''Sunday'', 1927 (proletarian poetry

Proletarian poetry is a political poetry movement that developed in the United States during the 1920s and 1930s that expresses the class-conscious perspectives of the working-class. Such poems are either explicitly Marxist or at least socialis ...

)

* ''Romboid,'' 1932 (This collection is influenced by poetism

Poetism (in Czech language, Czech: ''poetismus'') was an artistic program in Czechoslovakia which belongs to the avant-garde; it has never spread abroad. It was invented by members of avant-garde association Devětsil, mainly Vítězslav Nezval and ...

)

* ''Open windows'', 1935

* ''Saint behind the village'', 1939

* ''Villa Teresa'', 1963

* ''To the city 30 minutes'', 1963

* ''Stamodtúd et al'', 1964

* ''An Unnoticed World'', 1964

* ''The House I Live In'', 1966

*

Journalism and essays

* ''Marx and the Slovak Nation.'' 1933 * ''Education of the socialist generation.'' 1949 * ''The new spirit of the new school.'' 1949 * ''Sounding Echoes.'' 1969 * ''Honorary duty.'' 1969 * ''Manifestations and protests.'' 1970 * ''Ceremony of Certainty.'' 1970 * ''Bonds and liabilities.'' 1972 * ''About Hviezdoslav.'' 1971 * ''About literature.'' 1971 * ''The new spirit of the new school.'' 1974 * ''Work I, Work II''. 1984 * ''Repayment of large debt I.'' 1993 * ''Repayment of large debt II''. 1993References

{{authority control 1904 births 1976 deaths Writers from Budapest Politicians from Budapest Slovak poets Slovak writers Slovak communists Slovak journalists Czechoslovak communists Czechoslovak politicians Communist poets Socialist realism writers Recipients of the Order of Lenin Communist Party of Czechoslovakia politicians Members of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia Members of the National Assembly of Czechoslovakia (1948–1954) Slovak male writers 20th-century Slovak politicians