Kurt Von Schleicher on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

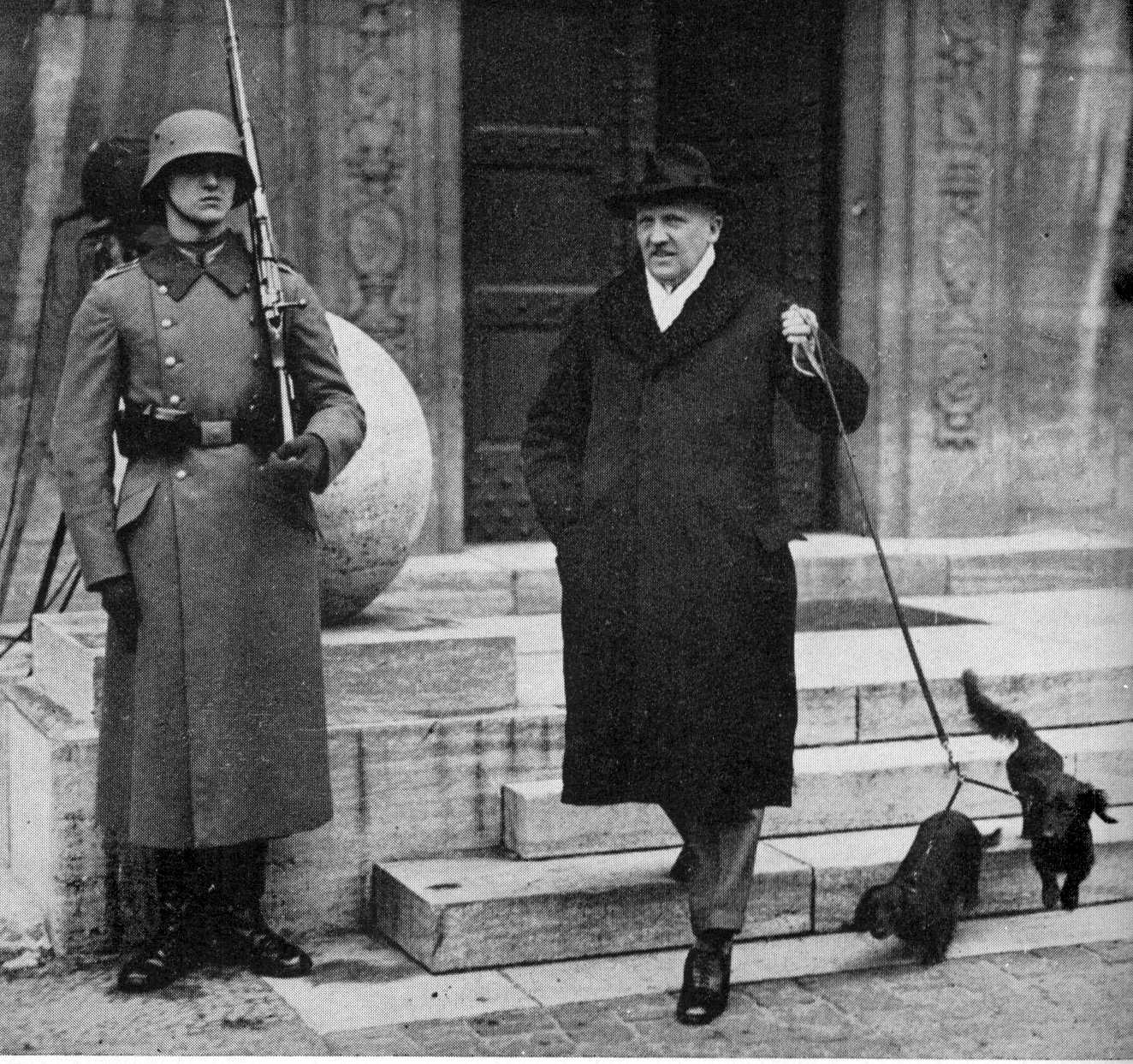

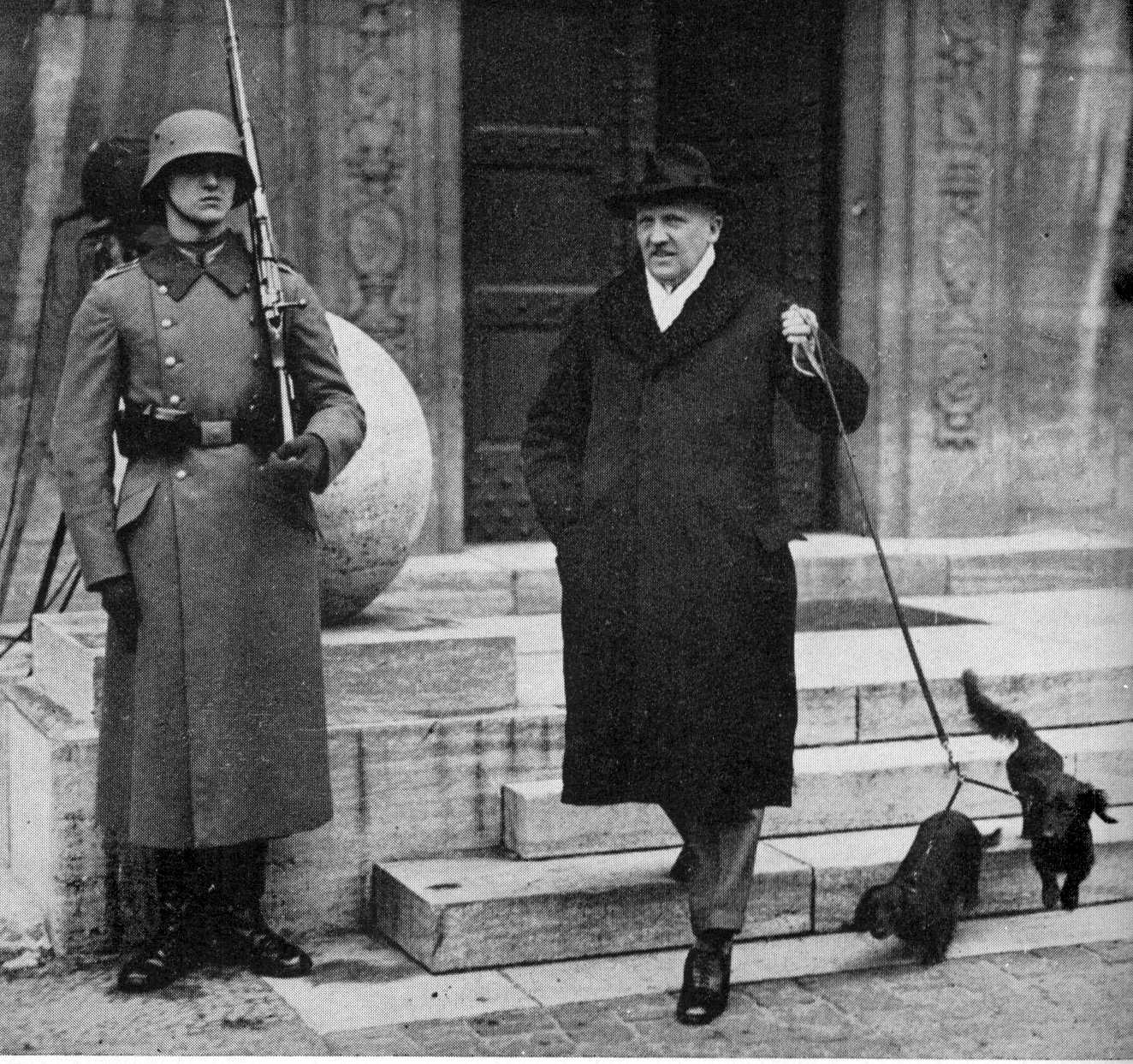

Kurt Ferdinand Friedrich Hermann von Schleicher (; 7 April 1882 – 30 June 1934) was a German general and the last

Kurt von Schleicher was born in

Kurt von Schleicher was born in

Although essentially a Prussian authoritarian, Schleicher also believed that the Army had a social function as an institution unifying the diverse elements in society. He was also opposed to policies such as Eastern Aid (Osthilfe) for the bankrupt East Elbian estates of his fellow

Although essentially a Prussian authoritarian, Schleicher also believed that the Army had a social function as an institution unifying the diverse elements in society. He was also opposed to policies such as Eastern Aid (Osthilfe) for the bankrupt East Elbian estates of his fellow

At the same time, Schleicher started rumors that General Groener was a secret Social Democrat, and argued that because Groener's daughter was born less than nine months after his marriage, Groener was unfit to hold office. On 8 May 1932, in exchange for promising to dissolve the ''Reichstag'' and lift the ban on the SA and the SS, Schleicher received a promise from Hitler to support a new government. After Groener had been savaged in a ''Reichstag'' debate with the Nazis over the alleged Social Democratic ''putsch'' and Groener's lack of belief in it, Schleicher told his mentor that "he no longer enjoyed the confidence of the Army" and must resign at once. When Groener appealed to Hindenburg, the president sided with Schleicher and told Groener to resign. With that, Groener resigned as Defense and Interior Minister.

At the same time, Schleicher started rumors that General Groener was a secret Social Democrat, and argued that because Groener's daughter was born less than nine months after his marriage, Groener was unfit to hold office. On 8 May 1932, in exchange for promising to dissolve the ''Reichstag'' and lift the ban on the SA and the SS, Schleicher received a promise from Hitler to support a new government. After Groener had been savaged in a ''Reichstag'' debate with the Nazis over the alleged Social Democratic ''putsch'' and Groener's lack of belief in it, Schleicher told his mentor that "he no longer enjoyed the confidence of the Army" and must resign at once. When Groener appealed to Hindenburg, the president sided with Schleicher and told Groener to resign. With that, Groener resigned as Defense and Interior Minister.

The new Chancellor, Von Papen, in return appointed Schleicher as Minister of Defense, who now became ''

The new Chancellor, Von Papen, in return appointed Schleicher as Minister of Defense, who now became '' Besides ordering new ''Reichstag'' elections, Schleicher and Papen worked together to undermine the Social Democratic government of Prussia headed by

Besides ordering new ''Reichstag'' elections, Schleicher and Papen worked together to undermine the Social Democratic government of Prussia headed by  In the ''Reichstag'' election of 31 July 1932, the NSDAP became the largest party as expected. In August 1932, Hitler reneged on the "gentlemen's agreement" he made with Schleicher that May, and instead of supporting the Papen government demanded the Chancellorship for himself. Schleicher was willing to accept Hitler's demand, but Hindenburg refused, preventing Hitler from receiving the Chancellorship in August 1932. Schleicher's influence with Hindenburg started to decline. Papen himself was most offended at the way Schleicher was prepared to forsake him casually.

On 12 September 1932, Papen's government was defeated on a no-confidence motion in the ''Reichstag'', at which point the ''Reichstag'' was again dissolved. In the election of 6 November 1932, the NSDAP lost seats, but still remained the largest party. By the beginning of November, Papen had shown himself to be more assertive than Schleicher had expected; this led to a growing rift between the two. Schleicher brought down Papen's government on 3 December 1932, when Papen told the Cabinet that he wished to declare martial law rather than losing face after another motion of no-confidence. Schleicher released the results of a war game which showed that if martial law was declared, the ''Reichswehr'' would not be able to defeat the various paramilitary groups. With the martial law option now off the table, Papen was forced to resign and Schleicher became Chancellor. This war games study, which was done by and presented to the Cabinet by one of Schleicher's close aides General Eugen Ott, was rigged with the aim of forcing Papen to resign. Papen became consumed with hatred against his former friend who had forced him from office.

In the ''Reichstag'' election of 31 July 1932, the NSDAP became the largest party as expected. In August 1932, Hitler reneged on the "gentlemen's agreement" he made with Schleicher that May, and instead of supporting the Papen government demanded the Chancellorship for himself. Schleicher was willing to accept Hitler's demand, but Hindenburg refused, preventing Hitler from receiving the Chancellorship in August 1932. Schleicher's influence with Hindenburg started to decline. Papen himself was most offended at the way Schleicher was prepared to forsake him casually.

On 12 September 1932, Papen's government was defeated on a no-confidence motion in the ''Reichstag'', at which point the ''Reichstag'' was again dissolved. In the election of 6 November 1932, the NSDAP lost seats, but still remained the largest party. By the beginning of November, Papen had shown himself to be more assertive than Schleicher had expected; this led to a growing rift between the two. Schleicher brought down Papen's government on 3 December 1932, when Papen told the Cabinet that he wished to declare martial law rather than losing face after another motion of no-confidence. Schleicher released the results of a war game which showed that if martial law was declared, the ''Reichswehr'' would not be able to defeat the various paramilitary groups. With the martial law option now off the table, Papen was forced to resign and Schleicher became Chancellor. This war games study, which was done by and presented to the Cabinet by one of Schleicher's close aides General Eugen Ott, was rigged with the aim of forcing Papen to resign. Papen became consumed with hatred against his former friend who had forced him from office.

Schleicher hoped to attain a majority in the ''Reichstag'' by gaining the support of the Nazis for his government. In mid-December 1932, Schleicher told a meeting of senior military leaders that the collapse of the Nazi movement was not in the best interests of the German state. By the end of 1932, the NSDAP was running out of money, increasingly prone to in-fighting and was discouraged by the ''Reichstag'' election of November 1932 where the party had lost votes. Schleicher took the view that the NSDAP would sooner or later have to support his government because only he could offer the Nazis power and otherwise the NSDAP would continue to disintegrate.

To gain Nazi support while keeping himself Chancellor, Schleicher talked of forming a so-called '' Querfront'' ("cross-front"), whereby he would unify Germany's fractious special interests around a non-parliamentary, authoritarian, but participatory regime as a way of forcing the Nazis to support his government. It was hoped that faced with the threat of the ''Querfront'', Hitler would back down in his demand for the Chancellorship and support Schleicher's government instead. Schleicher was never serious about creating a ''Querfront''; he intended it to be a bluff to compel the NSDAP to support the new government. As part of his attempt to blackmail Hitler into supporting his government, Schleicher went through the motions of attempting to found the ''Querfront'' by reaching out to the

Schleicher hoped to attain a majority in the ''Reichstag'' by gaining the support of the Nazis for his government. In mid-December 1932, Schleicher told a meeting of senior military leaders that the collapse of the Nazi movement was not in the best interests of the German state. By the end of 1932, the NSDAP was running out of money, increasingly prone to in-fighting and was discouraged by the ''Reichstag'' election of November 1932 where the party had lost votes. Schleicher took the view that the NSDAP would sooner or later have to support his government because only he could offer the Nazis power and otherwise the NSDAP would continue to disintegrate.

To gain Nazi support while keeping himself Chancellor, Schleicher talked of forming a so-called '' Querfront'' ("cross-front"), whereby he would unify Germany's fractious special interests around a non-parliamentary, authoritarian, but participatory regime as a way of forcing the Nazis to support his government. It was hoped that faced with the threat of the ''Querfront'', Hitler would back down in his demand for the Chancellorship and support Schleicher's government instead. Schleicher was never serious about creating a ''Querfront''; he intended it to be a bluff to compel the NSDAP to support the new government. As part of his attempt to blackmail Hitler into supporting his government, Schleicher went through the motions of attempting to found the ''Querfront'' by reaching out to the

That same day, Schleicher, learning that his government was about to fall, and fearing that his rival Papen would get the Chancellorship, began to favor a Hitler Chancellorship. Knowing of Papen's by now boundless hatred for him, Schleicher knew he had no chance of becoming Defense Minister in a new Papen government, but he felt his chances of becoming the Defense Minister in a Hitler government were very good.

Hitler was initially willing to support Schleicher as Defense Minister but a meeting with Schleicher's associate

That same day, Schleicher, learning that his government was about to fall, and fearing that his rival Papen would get the Chancellorship, began to favor a Hitler Chancellorship. Knowing of Papen's by now boundless hatred for him, Schleicher knew he had no chance of becoming Defense Minister in a new Papen government, but he felt his chances of becoming the Defense Minister in a Hitler government were very good.

Hitler was initially willing to support Schleicher as Defense Minister but a meeting with Schleicher's associate The Enabling Act

United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

Schleicher's successor as Defense Minister was his arch-enemy

Schleicher's successor as Defense Minister was his arch-enemy  Hitler had considered Schleicher a target for assassination for some time. When the

Hitler had considered Schleicher a target for assassination for some time. When the

At his funeral, Schleicher's friend von Hammerstein was offended when the SS refused to allow him to attend the service and confiscated wreaths that the mourners had brought. Hammerstein and ''Generalfeldmarschall''

At his funeral, Schleicher's friend von Hammerstein was offended when the SS refused to allow him to attend the service and confiscated wreaths that the mourners had brought. Hammerstein and ''Generalfeldmarschall''

online

* * Nicholls, A. J. ''Weimar and the Rise of Hitler'', New York: St. Martin's Press, 2000 * Patch, William. ''Heinrich Bruning and the Dissolution of the Weimar Republic'', Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006 * * Turner, Henry Ashby. "The Myth of Chancellor von Schleicher's Querfront Strategy." ''Central European History'' 41.4 (2008): 673–681

online

*

online

* Evans, Richard J. ''The Coming of the Third Reich'' (2004)

online

* Fay, Sidney B. "Von Schleicher as German Chancellor." ''Current History'' 37.5 (1933): 616–619

online

* Jones, Larry Eugene. "Franz von Papen, the German Center Party, and the Failure of Catholic Conservatism in the Weimar Republic." ''Central European History'' 38.2 (2005): 191–217

online

* Jones, Larry Eugene. "From Democracy to Dictatorship: The Fall of Weimar and the Triumph of Nazism, 1930–1933." in ''The Oxford Handbook of the Weimar Republic'' (2022) pp 95–108

excerpt

chancellor of Germany

The chancellor of Germany, officially the federal chancellor of the Federal Republic of Germany,; often shortened to ''Bundeskanzler''/''Bundeskanzlerin'', / is the head of the federal government of Germany and the commander in chief of the Ge ...

(before Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

) during the Weimar Republic

The Weimar Republic (german: link=no, Weimarer Republik ), officially named the German Reich, was the government of Germany from 1918 to 1933, during which it was a constitutional federal republic for the first time in history; hence it is al ...

. A rival for power with Hitler, Schleicher was murdered by Hitler's SS during the Night of the Long Knives

The Night of the Long Knives (German: ), or the Röhm purge (German: ''Röhm-Putsch''), also called Operation Hummingbird (German: ''Unternehmen Kolibri''), was a purge that took place in Nazi Germany from 30 June to 2 July 1934. Chancellor Ad ...

in 1934.

Schleicher was born into a military family in Brandenburg an der Havel

Brandenburg an der Havel () is a town in Brandenburg, Germany, which served as the capital of the Margraviate of Brandenburg until it was replaced by Berlin in 1417.

With a population of 72,040 (as of 2020), it is located on the banks of the H ...

on 7 April 1882. Entering the Prussian Army

The Royal Prussian Army (1701–1919, german: Königlich Preußische Armee) served as the army of the Kingdom of Prussia. It became vital to the development of Brandenburg-Prussia as a European power.

The Prussian Army had its roots in the co ...

as a lieutenant in 1900, he rose to become a General Staff

A military staff or general staff (also referred to as army staff, navy staff, or air staff within the individual services) is a group of officers, enlisted and civilian staff who serve the commander of a division or other large military un ...

officer in the Railway Department of the German General Staff

The German General Staff, originally the Prussian General Staff and officially the Great General Staff (german: Großer Generalstab), was a full-time body at the head of the Prussian Army and later, the German Army, responsible for the continuou ...

and served in the General Staff of the Supreme Army Command

The ''Oberste Heeresleitung'' (, Supreme Army Command or OHL) was the highest echelon of command of the army (''Heer'') of the German Empire. In the latter part of World War I, the Third OHL assumed dictatorial powers and became the ''de facto'' ...

during World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

. Schleicher served as liaison between the Army and the new Weimar Republic during the German Revolution of 1918–1919

The German Revolution or November Revolution (german: Novemberrevolution) was a civil conflict in the German Empire at the end of the First World War that resulted in the replacement of the German federal constitutional monarchy with a dem ...

. An important player in the Reichswehr

''Reichswehr'' () was the official name of the German armed forces during the Weimar Republic and the first years of the Third Reich. After Germany was defeated in World War I, the Imperial German Army () was dissolved in order to be reshaped ...

's efforts to avoid the restrictions of the Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles (french: Traité de Versailles; german: Versailler Vertrag, ) was the most important of the peace treaties of World War I. It ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers. It was signed on 28 June ...

, Schleicher rose to power as head of the Reichswehr's Armed Forces Department and was a close advisor to President Paul von Hindenburg

Paul Ludwig Hans Anton von Beneckendorff und von Hindenburg (; abbreviated ; 2 October 1847 – 2 August 1934) was a German field marshal and statesman who led the Imperial German Army during World War I and later became President of Germany fro ...

from 1926 onward. Following the appointment of his mentor Wilhelm Groener

Karl Eduard Wilhelm Groener (; 22 November 1867 – 3 May 1939) was a German general and politician. His organisational and logistical abilities resulted in a successful military career before and during World War I.

After a confrontation wi ...

as Minister of Defence

A defence minister or minister of defence is a Cabinet (government), cabinet official position in charge of a ministry of defense, which regulates the armed forces in sovereign states. The role of a defence minister varies considerably from coun ...

in 1928, Schleicher became head of the Defence Ministry's Office of Ministerial Affairs (''Ministeramt'') in 1929. In 1930, he was instrumental in the toppling of Hermann Müller's government and the appointment of Heinrich Brüning

Heinrich Aloysius Maria Elisabeth Brüning (; 26 November 1885 – 30 March 1970) was a German Centre Party politician and academic, who served as the chancellor of Germany during the Weimar Republic from 1930 to 1932.

A political scienti ...

as Chancellor. He enlisted the services of the Nazi Party

The Nazi Party, officially the National Socialist German Workers' Party (german: Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei or NSDAP), was a far-right politics, far-right political party in Germany active between 1920 and 1945 that crea ...

's SA as an auxiliary force for the Reichswehr from 1931 onward.

Beginning in 1932, Schleicher served as Minister of Defence in the cabinet of Franz von Papen

Franz Joseph Hermann Michael Maria von Papen, Erbsälzer zu Werl und Neuwerk (; 29 October 18792 May 1969) was a German conservative politician, diplomat, Prussian nobleman and General Staff officer. He served as the chancellor of Germany i ...

and was the prime mover behind the '' Preußenschlag'' coup against the Social Democratic

Social democracy is a political, social, and economic philosophy within socialism that supports political and economic democracy. As a policy regime, it is described by academics as advocating economic and social interventions to promote soci ...

government of Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an em ...

. Schleicher organized the downfall of Papen and succeeded him as Chancellor

Chancellor ( la, cancellarius) is a title of various official positions in the governments of many nations. The original chancellors were the of Roman courts of justice—ushers, who sat at the or lattice work screens of a basilica or law cou ...

on 3 December. During his brief term, Schleicher negotiated with Gregor Strasser

Gregor Strasser (also german: Straßer, see ß; 31 May 1892 – 30 June 1934) was an early prominent German Nazi Party, Nazi official and politician who was murdered during the Night of the Long Knives in 1934. Born in 1892 in Bavaria, Strasse ...

on a possible defection of the latter from the Nazi Party, but the plan was abandoned. Schleicher attempted to "tame" Hitler into cooperating with his government by threatening him with an anti-Nazi alliance of parties, the so-called ''Querfront'' ("cross-front"). Hitler refused to abandon his claim to the chancellorship and Schleicher's plan failed. Schleicher then proposed to Hindenburg that the latter disperse the Reichstag and rule as a ''de facto'' dictator, a course of action Hindenburg rejected.

On 28 January 1933, facing a political impasse and deteriorating health, Schleicher resigned and recommended the appointment of Hitler in his stead. Schleicher sought to return to politics by exploiting the divisions between Ernst Röhm

Ernst Julius Günther Röhm (; 28 November 1887 – 1 July 1934) was a German military officer and an early member of the Nazi Party. As one of the members of its predecessor, the German Workers' Party, he was a close friend and early ally ...

and Hitler but on 30 June 1934 he and his wife Elisabeth were murdered on the orders of Hitler during the Night of the Long Knives

The Night of the Long Knives (German: ), or the Röhm purge (German: ''Röhm-Putsch''), also called Operation Hummingbird (German: ''Unternehmen Kolibri''), was a purge that took place in Nazi Germany from 30 June to 2 July 1934. Chancellor Ad ...

.

Early life and family

Kurt von Schleicher was born in

Kurt von Schleicher was born in Brandenburg an der Havel

Brandenburg an der Havel () is a town in Brandenburg, Germany, which served as the capital of the Margraviate of Brandenburg until it was replaced by Berlin in 1417.

With a population of 72,040 (as of 2020), it is located on the banks of the H ...

, the son of Prussian

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an e ...

officer and noble Hermann Friedrich Ferdinand von Schleicher (1853–1906) and a wealthy East Prussia

East Prussia ; german: Ostpreißen, label=Low Prussian; pl, Prusy Wschodnie; lt, Rytų Prūsija was a province of the Kingdom of Prussia from 1773 to 1829 and again from 1878 (with the Kingdom itself being part of the German Empire from 187 ...

n shipowner

A ship-owner is the owner of a merchant vessel (commercial ship) and is involved in the shipping industry. In the commercial sense of the term, a shipowner is someone who equips and exploits a ship, usually for delivering cargo at a certain frei ...

's daughter, Magdalena Heyn (1857–1939). He had an older sister, Thusnelda Luise Amalie Magdalene (1879–1955), and a younger brother, Ludwig-Ferdinand Friedrich (1884–1923). On 28 July 1931, Schleicher married Elisabeth von Schleicher, daughter of the Prussian general Victor von Hennigs. She had previously been married to Schleicher's cousin, Bogislav von Schleicher, whom she had divorced on 4 May 1931.Marriage Register: Berlin-Lichterfelde

Lichterfelde () is a locality in the borough of Steglitz-Zehlendorf in Berlin, Germany. Until 2001 it was part of the former borough of Steglitz, along with Steglitz and Lankwitz. Lichterfelde is home to institutions like the Berlin Botanical Gar ...

: No. 4/1916.

He studied at the ''Hauptkadettenanstalt'' in Lichterfelde Lichterfelde may refer to:

* Lichterfelde (Berlin), a locality in the borough of Steglitz-Zehlendorf in Berlin, Germany

* Lichterfelde West, an elegant residential area in Berlin

* Lichterfelde, Saxony-Anhalt, a municipality in the Stendhal Distric ...

from 1896 to 1900. He was promoted to ''Leutnant'' on 22 March 1900 and was assigned to the 3rd Foot Guards, where he befriended fellow junior officers Oskar von Hindenburg

Oskar Wilhelm Robert Paul Ludwig Hellmuth von Beneckendorff und von Hindenburg (31 January 1883 – 12 February 1960) was a German ''Generalleutnant''. The son and aide-de-camp to Field Marshal and Reich President Paul von Hindenburg had consid ...

, Kurt von Hammerstein-Equord

Kurt Gebhard Adolf Philipp Freiherr von Hammerstein-Equord (26 September 1878 – 24 April 1943) was a German general (''Generaloberst'') who was the Commander-in-Chief of the Reichswehr, the Weimar Republic's armed forces. He is regarded as "a ...

and Erich von Manstein

Fritz Erich Georg Eduard von Manstein (born Fritz Erich Georg Eduard von Lewinski; 24 November 1887 – 9 June 1973) was a German Field Marshal of the ''Wehrmacht'' during the Second World War, who was subsequently convicted of war crimes and ...

. From 1 November 1906 to 31 October 1909, he served as adjutant of the ''Fusilier

Fusilier is a name given to various kinds of soldiers; its meaning depends on the historical context. While fusilier is derived from the 17th-century French language, French word ''fusil'' – meaning a type of flintlock musket – the term has ...

'' battalion of his regiment.

After his appointment as ''Oberleutnant'' on 18 October 1909, he was assigned to the Prussian Military Academy

The Prussian Staff College, also Prussian War College (german: Preußische Kriegsakademie) was the highest military facility of the Kingdom of Prussia to educate, train, and develop general staff officers.

Location

It originated with the ''A ...

, where he met Franz von Papen

Franz Joseph Hermann Michael Maria von Papen, Erbsälzer zu Werl und Neuwerk (; 29 October 18792 May 1969) was a German conservative politician, diplomat, Prussian nobleman and General Staff officer. He served as the chancellor of Germany i ...

. Upon graduation on 24 September 1913, he was assigned to the German General Staff

The German General Staff, originally the Prussian General Staff and officially the Great General Staff (german: Großer Generalstab), was a full-time body at the head of the Prussian Army and later, the German Army, responsible for the continuou ...

where he joined the Railway Department at his own request. He soon became a protégé of his immediate superior, Lieutenant Colonel Wilhelm Groener

Karl Eduard Wilhelm Groener (; 22 November 1867 – 3 May 1939) was a German general and politician. His organisational and logistical abilities resulted in a successful military career before and during World War I.

After a confrontation wi ...

. Schleicher was promoted to Captain on 18 December 1913.

First World War

After the outbreak of theFirst World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, Schleicher was assigned to the General Staff at the Supreme Army Command

The ''Oberste Heeresleitung'' (, Supreme Army Command or OHL) was the highest echelon of command of the army (''Heer'') of the German Empire. In the latter part of World War I, the Third OHL assumed dictatorial powers and became the ''de facto'' ...

. During the Battle of Verdun

The Battle of Verdun (french: Bataille de Verdun ; german: Schlacht um Verdun ) was fought from 21 February to 18 December 1916 on the Western Front in France. The battle was the longest of the First World War and took place on the hills north ...

he wrote a manuscript criticising war profiteering

A war profiteer is any person or organization that derives profit (economics), profit from warfare or by selling weapons and other goods to parties at war. The term typically carries strong negative connotations. General profiteering (business), ...

in certain industrial sectors, causing a sensation and earning him the approval of the Social Democratic Party of Germany

The Social Democratic Party of Germany (german: Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands, ; SPD, ) is a centre-left social democratic political party in Germany. It is one of the major parties of contemporary Germany.

Saskia Esken has been the ...

(SPD) chairman Friedrich Ebert

Friedrich Ebert (; 4 February 187128 February 1925) was a German politician of the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) and the first President of Germany (1919–1945), president of Germany from 1919 until his death in office in 1925.

Eber ...

and a reputation as a liberal. From November 1916 to May 1917, Schleicher served in the ''Kriegsamt'' (War Office), an agency tasked with administering the war economy led by Groener.

Schleicher's only front-line mission was as Chief of Staff of the 237th Division on the Eastern Front from 23 May 1917 to mid-August 1917 during the Kerensky Offensive. He served the rest of the war at the Supreme Army Command. He was promoted to Major on 15 July 1918. Following the collapse of the German war effort from August 1918 onward, Schleicher's patron Groener was appointed ''Erster Generalquartiermeister'' and assumed ''de facto'' command of the German Army

The German Army (, "army") is the land component of the armed forces of Germany. The present-day German Army was founded in 1955 as part of the newly formed West German ''Bundeswehr'' together with the ''Marine'' (German Navy) and the ''Luftwaf ...

on 29 October 1918. As Groener's trusted assistant, Schleicher became a crucial liaison between the civil and military authorities.

Army service after First World War

German Revolution

After the November Revolution of 1918, the situation of the German military was precarious. In December 1918, Schleicher delivered an ultimatum to Friedrich Ebert on behalf ofPaul von Hindenburg

Paul Ludwig Hans Anton von Beneckendorff und von Hindenburg (; abbreviated ; 2 October 1847 – 2 August 1934) was a German field marshal and statesman who led the Imperial German Army during World War I and later became President of Germany fro ...

demanding that the German provisional government either allow the Army to crush the Spartacus League

The Spartacus League (German: ''Spartakusbund'') was a Marxism, Marxist revolutionary movement organized in Germany during World War I. It was founded in August 1914 as the "International Group" by Rosa Luxemburg, Karl Liebknecht, Clara Zetkin, ...

or the Army would do that task itself.

During the ensuing talks with the German cabinet, Schleicher was able to get permission to allow the Army to return to Berlin. On 23 December 1918, the provisional government under Ebert came under attack from the radical left-wing ''Volksmarinedivision The Volksmarinedivision (People's Navy Division) was an armed unit formed on 11 November 1918 during the November Revolution that broke out in Germany following its defeat in World War I. At its peak late that month, the People's Navy Division ...

''. Schleicher played a key role in negotiating the Ebert–Groener pact The Ebert–Groener pact, sometimes called the Ebert-Groener deal, was an agreement between the Social Democrat Friedrich Ebert, at the time the Chancellor of Germany, and Wilhelm Groener, Quartermaster General of the German Army, on November 10, 1 ...

. In exchange for agreeing to send help to the government, Schleicher was able to secure Ebert's assent to the Army being allowed to maintain its political autonomy as a " state within the state".

To crush the left-wing rebels, Schleicher helped to found the ''Freikorps

(, "Free Corps" or "Volunteer Corps") were irregular German and other European military volunteer units, or paramilitary, that existed from the 18th to the early 20th centuries. They effectively fought as mercenary or private armies, regar ...

'' in early January 1919. Schleicher's role for the rest of the Weimar Republic

The Weimar Republic (german: link=no, Weimarer Republik ), officially named the German Reich, was the government of Germany from 1918 to 1933, during which it was a constitutional federal republic for the first time in history; hence it is al ...

was to serve as the ''Reichswehr

''Reichswehr'' () was the official name of the German armed forces during the Weimar Republic and the first years of the Third Reich. After Germany was defeated in World War I, the Imperial German Army () was dissolved in order to be reshaped ...

s political fixer, who would ensure that the military's interests would be secured.

1920s

Contacts with the Soviet Union

In the early 1920s, Schleicher emerged as a leading protégé of GeneralHans von Seeckt

Johannes "Hans" Friedrich Leopold von Seeckt (22 April 1866 – 27 December 1936) was a German military officer who served as Chief of Staff to August von Mackensen and was a central figure in planning the victories Mackensen achieved for Germany ...

, who often gave Schleicher sensitive assignments. In the spring of 1921, Seeckt created a secret group within the ''Reichswehr'' known as ''Sondergruppe R'', whose task was to work with the Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army (Russian: Рабо́че-крестья́нская Кра́сная армия),) often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic and, after ...

in their common struggle against the international system established by the Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles (french: Traité de Versailles; german: Versailler Vertrag, ) was the most important of the peace treaties of World War I. It ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers. It was signed on 28 June ...

. Schleicher worked out the arrangements with Leonid Krasin

Leonid Borisovich Krasin (russian: Леони́д Бори́сович Кра́син; 15 July 1870 – 24 November 1926) was a Russian Soviet politician, engineer, social entrepreneur, Bolshevik revolutionary politician and a Soviet diplomat. In 1 ...

for German aid to the Soviet arms industry. German financial and technological aid in building the industry was exchanged for Soviet support in helping Germany circumvent the disarmament clauses of the Treaty of Versailles. Schleicher created several dummy corporation

A dummy corporation, dummy company, or false company is an entity created to serve as a front or cover for one or more companies. It can have the appearance of being real (logo, website, and sometimes employing actual staff), but lacks the capacity ...

s, most notably the GEFU (''Gesellschaft zur Förderung gewerblicher Unternehmungen'', "Company for the Promotion of Industrial Enterprise"), which funnelled 75 million ''Reichsmarks

The (; sign: ℛℳ; abbreviation: RM) was the currency of Germany from 1924 until 20 June 1948 in West Germany, where it was replaced with the , and until 23 June 1948 in East Germany, where it was replaced by the East German mark. The Reichs ...

'', some $18 million (equivalent to $ million in ), into the Soviet arms industry by the end of 1923.

Black Reichswehr

At the same time, a team from ''Sondergruppe R'' comprising Schleicher, Eugen Ott,Fedor von Bock

Moritz Albrecht Franz Friedrich Fedor von Bock (3 December 1880 – 4 May 1945) was a German who served in the German Army during the Second World War. Bock served as the commander of Army Group North during the Invasion of Poland in ...

and Kurt von Hammerstein-Equord formed the liaison with Major Bruno Ernst Buchrucker, who led the so-called ''Arbeits-Kommandos'' (Work Commandos), officially a labor group intended to assist with civilian projects but in reality a force of soldiers. This fiction allowed Germany to exceed the limits on troop strength set by the Versailles Treaty. Buchrucker's so-called Black ''Reichswehr'' became infamous for its practice of murdering all Germans suspected of working as informers for the Allied Control Commission, which was responsible for ensuring that Germany was in compliance with Part V of the Treaty of Versailles.

The killings perpetrated by the "Black ''Reichswehr''" were justified under the so-called ''Femegerichte'' (secret court) system in which alleged traitors were killed after being "convicted" in secret "trials" of which the victims were unaware. These killings were ordered by officers from ''Sondergruppe R'' as the best way to neutralize the efforts of the Allied Control Commission.

Schleicher perjured himself several times under oath in court when he denied that the ''Reichswehr'' had anything to do with the "Black ''Reichswehr''" or the murders they had committed. In a secret letter sent to the president of the German Supreme Court, which was trying a member of the Black ''Reichswehr'' for murder, Seeckt admitted that the Black ''Reichswehr'' was controlled by the ''Reichswehr'', and claimed that the murders were justified by the struggle against Versailles; the court should therefore acquit the defendant. Although Seeckt disliked Schleicher, he appreciated his political finesse, and came increasingly to assign Schleicher tasks dealing with politicians.

Military-political role in the Weimar Republic

Despite Seeckt's patronage, it was Schleicher who brought about the former's downfall in 1926 by leaking the fact that Seeckt had invited the former Crown Prince to attend military manoeuvres. After Seeckt's fall Schleicher became, in the words ofAndreas Hillgruber

Andreas Fritz Hillgruber (18 January 1925 – 8 May 1989) was a conservative German historian who was influential as a military and diplomatic historian who played a leading role in the ''Historikerstreit'' of the 1980s. In his controversial book ...

, "in fact, if not in name hemilitary-political head of the ''Reichswehr''". Schleicher's triumph was also the triumph of the "modern" faction within the ''Reichswehr'', which favored a total war

Total war is a type of warfare that includes any and all civilian-associated resources and infrastructure as legitimate military targets, mobilizes all of the resources of society to fight the war, and gives priority to warfare over non-combata ...

ideology and wanted Germany to become a dictatorship that would wage total war upon the other nations of Europe.

During the 1920s Schleicher moved up steadily in the ''Reichswehr'', becoming the primary liaison between the army and civilian government officials. He was promoted to Lieutenant Colonel on 1 January 1924, and Colonel in 1926. On 29 January 1929, he became ''Generalmajor

is the Germanic variant of major general, used in a number of Central and Northern European countries.

Austria

Belgium

Denmark

is the second lowest general officer rank in the Royal Danish Army and Royal Danish Air Force. As a two-star ...

''. Schleicher generally preferred to operate behind the scenes, planting stories in friendly newspapers and relying on a casual network of informers to find out what other government departments were planning. Following the hyperinflation of 1923, the ''Reichswehr'' took over much of the administration of the country between September 1923 and February 1924, a task in which Schleicher played a prominent role.

The appointment of Groener as Defence Minister in January 1928 did much to advance Schleicher's career. Groener, who regarded Schleicher as his "adopted son", created the ''Ministeramt'' (Office of the Ministerial Affairs) for Schleicher in 1928. The new office officially dealt with all matters relating to joint concerns of the Army and Navy

A navy, naval force, or maritime force is the branch of a nation's armed forces principally designated for naval warfare, naval and amphibious warfare; namely, lake-borne, riverine, littoral zone, littoral, or ocean-borne combat operations and ...

, and was tasked with liaising between the military and other departments, and between the military and politicians. Because Schleicher interpreted that mandate very broadly, the ''Ministeramt'' quickly became the means by which the ''Reichswehr'' interfered in politics. The creation of the ''Ministeramt'' formalized Schleicher's position as the chief political fixer for the ''Reichswehr'', a role which had existed informally since 1918. He became ''Chef des Ministeramtes'' on 1 February 1929.

Like his patron Groener, Schleicher was alarmed by the results of the ''Reichstag'' election of 1928, in which the Social Democrats

Social democracy is a political, social, and economic philosophy within socialism that supports political and economic democracy. As a policy regime, it is described by academics as advocating economic and social interventions to promote so ...

(SPD) won the largest share of the vote on a platform of scrapping the building of ''Panzerkreuzer'' A, the intended lead ship of the proposed ''Deutschland'' class of "pocket battleships" together with the entire "pocket battleship" building programme. Schleicher opposed the prospect of a "grand coalition" headed by the SPD's Hermann Müller, and made it clear that he preferred that the SPD be excluded from power on the grounds that their anti-militarism

Militarism is the belief or the desire of a government or a people that a state should maintain a strong military capability and to use it aggressively to expand national interests and/or values. It may also imply the glorification of the mili ...

disqualified them from office. Both Groener and Schleicher had decided in the aftermath of the 1928 elections to put an end to democracy as the Social Democrats could not be trusted with power. Groener depended on Schleicher to get favorable military budget

A military budget (or military expenditure), also known as a defense budget, is the amount of financial resources dedicated by a state to raising and maintaining an armed forces or other methods essential for defense purposes.

Financing militar ...

s passed. Schleicher justified Groener's confidence by getting the naval budget for 1928 passed despite the opposition of the Social Democrats. Schleicher prepared Groener's statements to the Cabinet and attended Cabinet meetings on a regular basis. Above all, Schleicher won the right to brief President Hindenburg on both political and military matters.

In 1929, Schleicher came into conflict with Werner von Blomberg

Werner Eduard Fritz von Blomberg (2 September 1878 – 13 March 1946) was a German General Staff officer and the first Minister of War in Adolf Hitler's government. After serving on the Western Front in World War I, Blomberg was appointed chi ...

, the chief of the ''Truppenamt

The ''Truppenamt'' or was the cover organisation for the German General Staff from 1919 through until 1935 when the General Staff of the German Army (''Heer'') was re-created. This subterfuge was deemed necessary in order for Germany to be seen ...

'' (the disguised General Staff). That year Schleicher had started a policy of "frontier defense" (''Grenzschutz''), under which the ''Reichswehr'' would stockpile arms in secret depots and start training volunteers, in excess of the limits imposed by Versailles, in the eastern parts of Germany facing Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populous ...

. Blomberg wished to extend the system to the French border. Schleicher disagreed, wanting to give the French no excuse to delay their 1930 withdrawal

Withdrawal means "an act of taking out" and may refer to:

* Anchoresis (withdrawal from the world for religious or ethical reasons)

* ''Coitus interruptus'' (the withdrawal method)

* Drug withdrawal

* Social withdrawal

* Taking of money from a ban ...

from the Rhineland

The Rhineland (german: Rheinland; french: Rhénanie; nl, Rijnland; ksh, Rhingland; Latinised name: ''Rhenania'') is a loosely defined area of Western Germany along the Rhine, chiefly its middle section.

Term

Historically, the Rhinelands ...

. Blomberg lost the struggle and was demoted from command of the ''Truppenamt'' and sent to command a division in East Prussia

East Prussia ; german: Ostpreißen, label=Low Prussian; pl, Prusy Wschodnie; lt, Rytų Prūsija was a province of the Kingdom of Prussia from 1773 to 1829 and again from 1878 (with the Kingdom itself being part of the German Empire from 187 ...

.

Presidential government

In late 1926 or early 1927 Schleicher told Hindenburg that if it were impossible to form a government headed by theGerman National People's Party

The German National People's Party (german: Deutschnationale Volkspartei, DNVP) was a national-conservative party in Germany during the Weimar Republic. Before the rise of the Nazi Party, it was the major conservative and nationalist party in Wei ...

alone, then Hindenburg should "appoint a government in which he had confidence, without consulting the parties or paying attention to their wishes", and with "the order for dissolution ready to hand, give the government every constitutional opportunity to get a majority in Parliament." Together with Hindenburg's son, Major Oskar von Hindenburg, Otto Meißner, and General Wilhelm Groener, Schleicher was a leading member of the ''Kamarilla

A camarilla is a group of courtiers or favourites who surround a king or ruler. Usually, they do not hold any office or have any official authority at the royal court but influence their ruler behind the scenes. Consequently, they also escape havi ...

'' that surrounded President von Hindenburg. It was Schleicher who came up with the idea of a presidential government based on the so-called "25/48/53 formula", which referred to the three articles of the Weimar Constitution that could make a presidential government possible:

*Article 25 allowed the President to dissolve the ''Reichstag''.

* Article 48 allowed the President to sign into law emergency bills without the consent of the ''Reichstag''. However the ''Reichstag'' could cancel any law passed by Article 48 by a simple majority within sixty days of its passage.

*Article 53 allowed the President to appoint the Chancellor.

Schleicher's idea was to have Hindenburg use his powers under Article 53 to appoint a man of Schleicher's choosing as Chancellor, who would rule under the provisions of Article 48. Should the ''Reichstag'' threaten to annul any laws so passed, Hindenburg could counter with the threat of dissolution

Dissolution may refer to:

Arts and entertainment Books

* ''Dissolution'' (''Forgotten Realms'' novel), a 2002 fantasy novel by Richard Lee Byers

* ''Dissolution'' (Sansom novel), a 2003 historical novel by C. J. Sansom Music

* Dissolution, in mu ...

. Hindenburg was unenthusiastic about these plans, but was pressured into going along with them by his son, Meißner, Groener, and Schleicher. Schleicher was well known for his sense of humor, his lively conversational skills, his sharp wit and his habit of abandoning his upper class aristocratic accent to speak his German with a salty working class Berlin accent, full of risqué phrases that many found either charming or vulgar.

During the course of the winter of 1929–30 Schleicher undermined the "Grand Coalition" government of Hermann Müller by means of various intrigues, with the support of Groener and Hindenburg. In January 1930, after receiving ''Zentrum'' political party's Heinrich Brüning

Heinrich Aloysius Maria Elisabeth Brüning (; 26 November 1885 – 30 March 1970) was a German Centre Party politician and academic, who served as the chancellor of Germany during the Weimar Republic from 1930 to 1932.

A political scienti ...

's assent to heading a presidential government, Schleicher had told Brüning that the "Hindenburg government" was to be "anti-Marxist

Marxism is a Left-wing politics, left-wing to Far-left politics, far-left method of socioeconomic analysis that uses a Materialism, materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to understand S ...

" and "anti-parliamentarian", and under no conditions were the Social Democrats to be allowed to serve in office, even though the SPD was the largest party in the ''Reichstag''. In March 1930 Müller's government fell, and the first presidential government headed by Brüning came into office. The German historian Eberhard Kolb

Professor Eberhard Kolb (born 8 August 1933, Stuttgart) is a German historian, best known for his research of the German history of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

Biography

Eberhard Kolb studied at the universities of Tübingen and Bo ...

described the presidential governments that began in March 1930 as a sort of 'creeping' ''coup d'état'', by which the government gradually become more and more authoritarian and less and less democratic, a process that culminated with the Nazi regime in 1933. The British historian Edgar Feuchtwanger called the Brüning government Schleicher's "brainchild".

Social function of the Army

Although essentially a Prussian authoritarian, Schleicher also believed that the Army had a social function as an institution unifying the diverse elements in society. He was also opposed to policies such as Eastern Aid (Osthilfe) for the bankrupt East Elbian estates of his fellow

Although essentially a Prussian authoritarian, Schleicher also believed that the Army had a social function as an institution unifying the diverse elements in society. He was also opposed to policies such as Eastern Aid (Osthilfe) for the bankrupt East Elbian estates of his fellow Junker

Junker ( da, Junker, german: Junker, nl, Jonkheer, en, Yunker, no, Junker, sv, Junker ka, იუნკერი (Iunkeri)) is a noble honorific, derived from Middle High German ''Juncherre'', meaning "young nobleman"Duden; Meaning of Junke ...

s.

To bypass Part V of the Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles (french: Traité de Versailles; german: Versailler Vertrag, ) was the most important of the peace treaties of World War I. It ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers. It was signed on 28 June ...

, which had forbidden conscription

Conscription (also called the draft in the United States) is the state-mandated enlistment of people in a national service, mainly a military service. Conscription dates back to antiquity and it continues in some countries to the present day un ...

, Schleicher engaged the services of the SA and other paramilitaries as the best substitute for conscription. From December 1930 onwards, Schleicher was in regular secret contact with Ernst Röhm

Ernst Julius Günther Röhm (; 28 November 1887 – 1 July 1934) was a German military officer and an early member of the Nazi Party. As one of the members of its predecessor, the German Workers' Party, he was a close friend and early ally ...

, the leader of the SA, who soon became one of his best friends. On 2 January 1931 Schleicher changed the Defense Ministry's rules to allow National Socialists to serve in military depots and arsenals, though not as officers, combat troops or sailors. Before 1931, members of the military had been strictly forbidden to join any political parties, because the ''Reichswehr'' was supposed to be non-political. It was only National Socialists who were allowed to join the ''Reichswehr'' in Schleicher's changing of the rules; if a member of the ''Reichswehr'' joined any other political party, he would be dishonourably discharged. In March 1931, without the knowledge of either Groener or Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

, Schleicher and Röhm reached a secret arrangement that in the event of a war with Poland or a Communist ''putsch'', or both, the SA would mobilise and come under the command of ''Reichswehr'' officers in order to deal with the national emergency. The close friendship between Schleicher and Röhm was later in 1934 to provide a seemingly factual basis to Hitler's claim that Schleicher and Röhm had been plotting to overthrow him, thus justifying the assassination of both.

Like the rest of the ''Reichswehr'' leadership, Schleicher saw democracy as an impediment to military power, and was convinced that only a dictatorship could make Germany a great military power again. It was Schleicher's dream to create a ''Wehrstaat'' (Military State), in which the military would reorganize German society as part of the preparations for the total war that the ''Reichswehr'' wished to wage. From the second half of 1931 onwards Schleicher was the leading advocate within the German government of the ''Zähmungskonzept'' (taming concept) where the Nazis were to be "tamed" by being brought into the government. Schleicher, a militarist to the core, greatly admired the militarism of the Nazis; and the fact that ''Grenzschutz'' was working well, especially in East Prussia where the SA was serving as an unofficial militia backing up the ''Reichswehr'' was seen as a model for future Army-Nazi co-operation.

Schleicher became a major figure behind the scenes in the presidential cabinet government of Heinrich Brüning

Heinrich Aloysius Maria Elisabeth Brüning (; 26 November 1885 – 30 March 1970) was a German Centre Party politician and academic, who served as the chancellor of Germany during the Weimar Republic from 1930 to 1932.

A political scienti ...

between 1930 and 1932, serving as an aide to ''General'' Groener, the Minister of Defense. Eventually, Schleicher, who established a close relationship with '' Reichspräsident'' (''Reich President'') Paul von Hindenburg, came into conflict with Brüning and Groener and his intrigues were largely responsible for their fall in May 1932.

Presidential election of 1932

One of Schleicher's aides later recalled that Schleicher viewed the Nazis as "an essentially healthy reaction of the '' Volkskörper''" and praised the Nazis as "the only party that could attract voters away from the radical left and had already done so." Schleicher planned to secure Nazi support for a new right-wing presidential government of his creation, thereby destroying German democracy. Schleicher would then crush the Nazis by exploiting feuds between various Nazi leaders and by incorporating the SA into the ''Reichswehr''. During this period, Schleicher became increasingly convinced that the solution to all of Germany's problems was a " strong man" and that he was that strong man. Schleicher told Hindenburg that his gruelling re-election campaign was the fault of Brüning. Schleicher claimed that Brüning could have had Hindenburg's term extended by the ''Reichstag'', but that he chose not to in order to humiliate Hindenburg by making him appear on the same stage as Social Democratic leaders. Brüning banned the SA and the SS on 13 April 1932 on the grounds they were ones chiefly responsible for the wave of political violence afflicting Germany. The banning of the SA and SS saw an immediate and huge drop in the amount of political violence in Germany but threatened to destroy Schleicher's policy of reaching out to the Nazis, and as a result Schleicher decided that both Brüning and Groener had to go. On 16 April, Groener received an angry letter from Hindenburg demanding to know why the ''Reichsbanner'', the paramilitary wing of the Social Democrats had not also been banned. This was especially the case as Hindenburg said he had solid evidence that the ''Reichsbanner'' was planning a coup. The same letter from the president was leaked and appeared that day in all the right-wing German newspapers. Groener discovered that Eugen Ott, a close protégé of Schleicher, had made the Social Democratic ''putsch'' allegations to Hindenburg and leaked the President's letter. British historianJohn Wheeler-Bennett

Sir John Wheeler Wheeler-Bennett (13 October 1902 – 9 December 1975) was a conservative English historian of German and diplomatic history, and the official biographer of King George VI. He was well known in his lifetime, and his inter ...

wrote that the evidence for an intended SPD ''putsch'' was "flimsy" at best, and this was just Schleicher's way of discrediting Groener in Hindenburg's eyes. Groener's friends told him that it was impossible that Ott would fabricate allegations of that sort or leak the President's letter on his own, and that he should sack Schleicher at once. Groener refused to believe that his old friend had turned on him and refused to fire Schleicher.

At the same time, Schleicher started rumors that General Groener was a secret Social Democrat, and argued that because Groener's daughter was born less than nine months after his marriage, Groener was unfit to hold office. On 8 May 1932, in exchange for promising to dissolve the ''Reichstag'' and lift the ban on the SA and the SS, Schleicher received a promise from Hitler to support a new government. After Groener had been savaged in a ''Reichstag'' debate with the Nazis over the alleged Social Democratic ''putsch'' and Groener's lack of belief in it, Schleicher told his mentor that "he no longer enjoyed the confidence of the Army" and must resign at once. When Groener appealed to Hindenburg, the president sided with Schleicher and told Groener to resign. With that, Groener resigned as Defense and Interior Minister.

At the same time, Schleicher started rumors that General Groener was a secret Social Democrat, and argued that because Groener's daughter was born less than nine months after his marriage, Groener was unfit to hold office. On 8 May 1932, in exchange for promising to dissolve the ''Reichstag'' and lift the ban on the SA and the SS, Schleicher received a promise from Hitler to support a new government. After Groener had been savaged in a ''Reichstag'' debate with the Nazis over the alleged Social Democratic ''putsch'' and Groener's lack of belief in it, Schleicher told his mentor that "he no longer enjoyed the confidence of the Army" and must resign at once. When Groener appealed to Hindenburg, the president sided with Schleicher and told Groener to resign. With that, Groener resigned as Defense and Interior Minister.

The Papen government

On 30 May 1932, Schleicher's intrigues bore fruit when Hindenburg dismissed Brüning as Chancellor and appointedFranz von Papen

Franz Joseph Hermann Michael Maria von Papen, Erbsälzer zu Werl und Neuwerk (; 29 October 18792 May 1969) was a German conservative politician, diplomat, Prussian nobleman and General Staff officer. He served as the chancellor of Germany i ...

as his successor. Feuchtwanger called Schleicher the "principal wire-puller" behind Brüning's fall.

Schleicher had chosen Papen, who was unknown to the German public, as new Chancellor because he believed he could control Papen from behind the scenes. Kolb wrote of Schleicher's "key role" in the downfall of not only Brüning, but also the Weimar Republic, for, by bringing down Brüning, Schleicher unintentionally set off a series of events that would lead directly to the Third ''Reich''.

Schleicher's example in bringing down the Brüning government led to a more overt politicization of the ''Reichswehr''. From the spring of 1932 officers such as Werner von Blomberg

Werner Eduard Fritz von Blomberg (2 September 1878 – 13 March 1946) was a German General Staff officer and the first Minister of War in Adolf Hitler's government. After serving on the Western Front in World War I, Blomberg was appointed chi ...

and Walther von Reichenau

Walter Karl Ernst August von Reichenau (8 October 1884 – 17 January 1942) was a field marshal in the Wehrmacht of Nazi Germany during World War II. Reichenau commanded the 6th Army, during the invasions of Belgium and France. During Ope ...

had started talks on their own with the NSDAP

The Nazi Party, officially the National Socialist German Workers' Party (german: Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei or NSDAP), was a far-right politics, far-right political party in Germany active between 1920 and 1945 that crea ...

. Schleicher's example actually served to undermine his own power, since, in part, his power had always rested on the fact that he was the only general who was allowed to talk to the politicians.

Minister of Defense

The new Chancellor, Von Papen, in return appointed Schleicher as Minister of Defense, who now became ''

The new Chancellor, Von Papen, in return appointed Schleicher as Minister of Defense, who now became ''General der Infanterie General of the Infantry is a military rank of a General officer in the infantry and refers to:

* General of the Infantry (Austria)

* General of the Infantry (Bulgaria)

* General of the Infantry (Germany) ('), a rank of a general in the German Imper ...

''. Schleicher had selected the entire cabinet himself before he even had approached Papen with the offer to be Chancellor. The first act of the new government was to dissolve the ''Reichstag'' in accordance with Schleicher's "gentlemen's agreement" with Hitler on 4 June 1932. On 15 June 1932, the new government lifted the ban on the SA and the SS, who were secretly encouraged to indulge in as much violence as possible, both to discredit democracy and to provide a pretext for the new authoritarian regime Schleicher was working to create.

Besides ordering new ''Reichstag'' elections, Schleicher and Papen worked together to undermine the Social Democratic government of Prussia headed by

Besides ordering new ''Reichstag'' elections, Schleicher and Papen worked together to undermine the Social Democratic government of Prussia headed by Otto Braun

Otto Braun (28 January 1872 – 15 December 1955) was a politician of the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) during the Weimar Republic. From 1920 to 1932, with only two brief interruptions, Braun was Minister President of the Free State of ...

. Schleicher fabricated evidence that the Prussian police under Braun's orders were favoring the Communist '' Rotfrontkämpferbund'' in street clashes with the SA, which he used to get an emergency decree from Hindenburg imposing ''Reich'' control on Prussia. To facilitate his plans for a coup against the Prussian government and to avert the danger of a general strike which had defeated the Kapp Putsch

The Kapp Putsch (), also known as the Kapp–Lüttwitz Putsch (), was an attempted coup against the German national government in Berlin on 13 March 1920. Named after its leaders Wolfgang Kapp and Walther von Lüttwitz, its goal was to undo the ...

of 1920, Schleicher had a series of secret meetings with trade union leaders, during which he promised them a leading role in the new authoritarian political system he was building, in return for which he received a promise that there would be no general strike in support of Braun.

In the "Rape of Prussia" on 20 July 1932, Schleicher had martial law proclaimed and called out the ''Reichswehr'' under Gerd von Rundstedt

Karl Rudolf Gerd von Rundstedt (12 December 1875 – 24 February 1953) was a German field marshal in the '' Heer'' (Army) of Nazi Germany during World War II.

Born into a Prussian family with a long military tradition, Rundstedt entered th ...

to oust the elected Prussian government, which was accomplished without a shot being fired. Using Article 48, Hindenburg named Papen the ''Reich'' Commissioner of Prussia. To help with advice for the new regime that he was planning to create, in the summer of 1932 Schleicher engaged the services of a group of right-wing intellectuals known as the '' Tatkreis'', and through them got to know Gregor Strasser

Gregor Strasser (also german: Straßer, see ß; 31 May 1892 – 30 June 1934) was an early prominent German Nazi Party, Nazi official and politician who was murdered during the Night of the Long Knives in 1934. Born in 1892 in Bavaria, Strasse ...

.

In the ''Reichstag'' election of 31 July 1932, the NSDAP became the largest party as expected. In August 1932, Hitler reneged on the "gentlemen's agreement" he made with Schleicher that May, and instead of supporting the Papen government demanded the Chancellorship for himself. Schleicher was willing to accept Hitler's demand, but Hindenburg refused, preventing Hitler from receiving the Chancellorship in August 1932. Schleicher's influence with Hindenburg started to decline. Papen himself was most offended at the way Schleicher was prepared to forsake him casually.

On 12 September 1932, Papen's government was defeated on a no-confidence motion in the ''Reichstag'', at which point the ''Reichstag'' was again dissolved. In the election of 6 November 1932, the NSDAP lost seats, but still remained the largest party. By the beginning of November, Papen had shown himself to be more assertive than Schleicher had expected; this led to a growing rift between the two. Schleicher brought down Papen's government on 3 December 1932, when Papen told the Cabinet that he wished to declare martial law rather than losing face after another motion of no-confidence. Schleicher released the results of a war game which showed that if martial law was declared, the ''Reichswehr'' would not be able to defeat the various paramilitary groups. With the martial law option now off the table, Papen was forced to resign and Schleicher became Chancellor. This war games study, which was done by and presented to the Cabinet by one of Schleicher's close aides General Eugen Ott, was rigged with the aim of forcing Papen to resign. Papen became consumed with hatred against his former friend who had forced him from office.

In the ''Reichstag'' election of 31 July 1932, the NSDAP became the largest party as expected. In August 1932, Hitler reneged on the "gentlemen's agreement" he made with Schleicher that May, and instead of supporting the Papen government demanded the Chancellorship for himself. Schleicher was willing to accept Hitler's demand, but Hindenburg refused, preventing Hitler from receiving the Chancellorship in August 1932. Schleicher's influence with Hindenburg started to decline. Papen himself was most offended at the way Schleicher was prepared to forsake him casually.

On 12 September 1932, Papen's government was defeated on a no-confidence motion in the ''Reichstag'', at which point the ''Reichstag'' was again dissolved. In the election of 6 November 1932, the NSDAP lost seats, but still remained the largest party. By the beginning of November, Papen had shown himself to be more assertive than Schleicher had expected; this led to a growing rift between the two. Schleicher brought down Papen's government on 3 December 1932, when Papen told the Cabinet that he wished to declare martial law rather than losing face after another motion of no-confidence. Schleicher released the results of a war game which showed that if martial law was declared, the ''Reichswehr'' would not be able to defeat the various paramilitary groups. With the martial law option now off the table, Papen was forced to resign and Schleicher became Chancellor. This war games study, which was done by and presented to the Cabinet by one of Schleicher's close aides General Eugen Ott, was rigged with the aim of forcing Papen to resign. Papen became consumed with hatred against his former friend who had forced him from office.

Chancellorship

Schleicher hoped to attain a majority in the ''Reichstag'' by gaining the support of the Nazis for his government. In mid-December 1932, Schleicher told a meeting of senior military leaders that the collapse of the Nazi movement was not in the best interests of the German state. By the end of 1932, the NSDAP was running out of money, increasingly prone to in-fighting and was discouraged by the ''Reichstag'' election of November 1932 where the party had lost votes. Schleicher took the view that the NSDAP would sooner or later have to support his government because only he could offer the Nazis power and otherwise the NSDAP would continue to disintegrate.

To gain Nazi support while keeping himself Chancellor, Schleicher talked of forming a so-called '' Querfront'' ("cross-front"), whereby he would unify Germany's fractious special interests around a non-parliamentary, authoritarian, but participatory regime as a way of forcing the Nazis to support his government. It was hoped that faced with the threat of the ''Querfront'', Hitler would back down in his demand for the Chancellorship and support Schleicher's government instead. Schleicher was never serious about creating a ''Querfront''; he intended it to be a bluff to compel the NSDAP to support the new government. As part of his attempt to blackmail Hitler into supporting his government, Schleicher went through the motions of attempting to found the ''Querfront'' by reaching out to the

Schleicher hoped to attain a majority in the ''Reichstag'' by gaining the support of the Nazis for his government. In mid-December 1932, Schleicher told a meeting of senior military leaders that the collapse of the Nazi movement was not in the best interests of the German state. By the end of 1932, the NSDAP was running out of money, increasingly prone to in-fighting and was discouraged by the ''Reichstag'' election of November 1932 where the party had lost votes. Schleicher took the view that the NSDAP would sooner or later have to support his government because only he could offer the Nazis power and otherwise the NSDAP would continue to disintegrate.

To gain Nazi support while keeping himself Chancellor, Schleicher talked of forming a so-called '' Querfront'' ("cross-front"), whereby he would unify Germany's fractious special interests around a non-parliamentary, authoritarian, but participatory regime as a way of forcing the Nazis to support his government. It was hoped that faced with the threat of the ''Querfront'', Hitler would back down in his demand for the Chancellorship and support Schleicher's government instead. Schleicher was never serious about creating a ''Querfront''; he intended it to be a bluff to compel the NSDAP to support the new government. As part of his attempt to blackmail Hitler into supporting his government, Schleicher went through the motions of attempting to found the ''Querfront'' by reaching out to the Social Democratic

Social democracy is a political, social, and economic philosophy within socialism that supports political and economic democracy. As a policy regime, it is described by academics as advocating economic and social interventions to promote soci ...

labor unions, the Christian labor unions, and the economically left-wing branch of the Nazi Party, led by Gregor Strasser

Gregor Strasser (also german: Straßer, see ß; 31 May 1892 – 30 June 1934) was an early prominent German Nazi Party, Nazi official and politician who was murdered during the Night of the Long Knives in 1934. Born in 1892 in Bavaria, Strasse ...

.

On 4 December 1932, Schleicher met with Strasser and offered to restore the Prussian government from ''Reich'' control and make Strasser the new Minister-President of Prussia. Schleicher's hope was that the threat of a split within the Nazi Party, with Strasser leading his faction out of the party, would force Hitler to support the new government. Schleicher's policy failed as Hitler isolated Strasser in the party.

One of the main initiatives of the Schleicher government was a public works program intended to counter the effects of the Great Depression, which was shepherded by Günther Gereke, whom Schleicher had appointed special commissioner for employment. The various public works projects—which were to give 2 million unemployed Germans jobs by July 1933 and are often wrongly attributed to Hitler—were the work of the Schleicher government, which had passed the necessary legislation in January.

Schleicher's relations with his Cabinet were poor because of Schleicher's secretive ways and open contempt for his ministers. With two exceptions, Schleicher retained all of Papen's cabinet, which meant that much of the unpopularity of the Papen government was inherited by Schleicher's government. Shortly after Schleicher became Chancellor, he told some joke at the expense of Major Oskar von Hindenburg

Oskar Wilhelm Robert Paul Ludwig Hellmuth von Beneckendorff und von Hindenburg (31 January 1883 – 12 February 1960) was a German ''Generalleutnant''. The son and aide-de-camp to Field Marshal and Reich President Paul von Hindenburg had consid ...

, which greatly offended the younger Hindenburg and reduced Schleicher's access to the President. Papen by contrast had been able to stay on excellent terms with both Hindenburgs.

Regarding tariffs, Schleicher refused to make a firm stand. Schleicher's non-policy on tariffs hurt his government very badly when on 11 January 1933 the leaders of the Agricultural League

The Imperial Agricultural League (german: Reichs-Landbund) or National Rural League was a German agrarian association during the Weimar Republic which was led by landowners with property east of the Elbe. It was allied with the German National Pe ...

launched a blistering attack on Schleicher in front of Hindenburg. The Agricultural League leaders attacked Schleicher for his failure to keep his promise to raise tariffs on food imports, and for allowing to lapse a law from the Papen government that gave farmers a grace period from foreclosure if they defaulted on their debts. Hindenburg forced Schleicher to accede to all of the League's demands.

In foreign policy, Schleicher's main interest was in winning ''Gleichberechtigung'' ("equality of status") at the World Disarmament Conference

The Conference for the Reduction and Limitation of Armaments, generally known as the Geneva Conference or World Disarmament Conference, was an international conference of states held in Geneva, Switzerland, between February 1932 and November 1934 ...

, which would do away with Part V of the Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles (french: Traité de Versailles; german: Versailler Vertrag, ) was the most important of the peace treaties of World War I. It ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers. It was signed on 28 June ...

that had disarmed Germany. Schleicher made a point of cultivating the French ambassador André François-Poncet

André François-Poncet (13 June 1887 – 8 January 1978) was a French politician and diplomat whose post as ambassador to Germany allowed him to witness first-hand the rise to power of Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party, and the Nazi regime's prep ...

and stressing his concern with improving Franco-German relations. This was in part because Schleicher wanted to ensure French acceptance of ''Gleichberechtigung'' in order to allow Germany to rearm without fear of a French "preventative war." He also believed that improving Berlin-Paris relations would lead the French to abrogate the Franco-Polish alliance of 1921, which would allow Germany to partition Poland with the Soviet Union without having to go to war with France. In a speech before a group of German journalists on 13 January 1933, Schleicher proclaimed that based on the acceptance "in principle" of ''Gleichberechtigung'' by the other powers at the World Disarmament Conference

The Conference for the Reduction and Limitation of Armaments, generally known as the Geneva Conference or World Disarmament Conference, was an international conference of states held in Geneva, Switzerland, between February 1932 and November 1934 ...

in December 1932, he planned to have by no later than the spring of 1934 a return to conscription and for Germany to have all the weapons forbidden by Versailles.

Political misstep

On 20 January 1933, Schleicher missed one of his best chances to save his government.Wilhelm Frick

Wilhelm Frick (12 March 1877 – 16 October 1946) was a prominent German politician of the Nazi Party (NSDAP), who served as Reich Minister of the Interior in Adolf Hitler's cabinet from 1933 to 1943 and as the last governor of the Protectorate ...

—who was in charge of the Nazi ''Reichstag'' delegation when Hermann Göring

Hermann Wilhelm Göring (or Goering; ; 12 January 1893 – 15 October 1946) was a German politician, military leader and convicted war criminal. He was one of the most powerful figures in the Nazi Party, which ruled Germany from 1933 to 1 ...

was not present—suggested to the ''Reichstags agenda committee that the ''Reichstag'' go into recess until the next budget could be presented, which would have been some time in the spring. Had this happened, by the time the recess ended, Schleicher would have been reaping the benefits of the public works projects that his government had begun in January, and in-fighting within the NSDAP would have worsened. Schleicher had his Chief of Staff, Erwin Planck

Erwin Planck (12 March 1893 – 23 January 1945) was a German politician, and a resistance fighter against the Nazi regime.

Biography

Born in Charlottenburg (today part of Berlin), Erwin Planck was the fourth child of Nobel Prize-winning physici ...

, tell the ''Reichstag'' that the government wanted the recess to be as short as possible, which led to the recess being extended only to 31 January as Schleicher believed mistakenly that the ''Reichstag'' would not dare bring a motion of no-confidence against him as that would mean another election.

The ousted Papen now had Hindenburg's ear, and used his position to advise the President to sack Schleicher at the first chance. Papen was urging the aged President to appoint Hitler as Chancellor in a coalition with the Nationalist ''Deutschnationale Volkspartei'' (German National People's Party; DNVP) who, together with Papen, would supposedly work to rein in Hitler. Papen was holding secret meetings with both Hitler and Hindenburg, who then refused Schleicher's request for emergency powers and another dissolution of the ''Reichstag''. Schleicher for a long time refused to take seriously the possibility that Papen was working to bring him down.

The consequence of promoting the idea of presidential government where everything depended upon President Hindenburg's whims, with the ''Reichstag'' weakened, meant that when Hindenburg decided against Schleicher, the latter was in an extremely weak political position. By January 1933, Schleicher's reputation as the destroyer of governments, as a man who was just as happy intriguing against his friends as his enemies, and as a man who had betrayed all who had trusted him, meant he was universally distrusted and disliked by all factions, which further weakened his attempts to stay in power.