King Ottokar's Sceptre on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''King Ottokar's Sceptre'' (french: link=no, Le Sceptre d'Ottokar) is the eighth volume of ''

''King Ottokar's Sceptre'' was not the first Tintin adventure to draw specifically on contemporary events;

''King Ottokar's Sceptre'' was not the first Tintin adventure to draw specifically on contemporary events;  The name Syldavia may be a composite of

The name Syldavia may be a composite of

Harry Thompson described ''King Ottokar's Sceptre'' as a "biting political satire" and asserted that it was "courageous" of Hergé to have written it given that the threat of Nazi invasion was imminent. Describing it as a "classic

Harry Thompson described ''King Ottokar's Sceptre'' as a "biting political satire" and asserted that it was "courageous" of Hergé to have written it given that the threat of Nazi invasion was imminent. Describing it as a "classic

''King Ottokar's Sceptre''

at the Official Tintin Website

at Tintinologist.org {{Portal bar, Belgium, Comics 1939 graphic novels 1947 graphic novels Comics set in a fictional country Comics set in Europe Literature first published in serial form Methuen Publishing books Tintin books Works originally published in Le Petit Vingtième

The Adventures of Tintin

''The Adventures of Tintin'' (french: Les Aventures de Tintin ) is a series of 24 bande dessinée#Formats, ''bande dessinée'' albums created by Belgians, Belgian cartoonist Georges Remi, who wrote under the pen name Hergé. The series was one ...

'', the comics series by Belgian cartoonist Hergé

Georges Prosper Remi (; 22 May 1907 – 3 March 1983), known by the pen name Hergé (; ), from the French pronunciation of his reversed initials ''RG'', was a Belgian cartoonist. He is best known for creating ''The Adventures of Tintin'', ...

. Commissioned by the conservative Belgian newspaper for its children's supplement , it was serialised weekly from August 1938 to August 1939. Hergé intended the story as a satirical criticism of the expansionist policies of Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

, in particular the annexation

Annexation (Latin ''ad'', to, and ''nexus'', joining), in international law, is the forcible acquisition of one state's territory by another state, usually following military occupation of the territory. It is generally held to be an illegal act ...

of Austria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populous ...

in March 1938 (the ''Anschluss

The (, or , ), also known as the (, en, Annexation of Austria), was the annexation of the Federal State of Austria into the German Reich on 13 March 1938.

The idea of an (a united Austria and Germany that would form a " Greater Germa ...

''). The story tells of young Belgian reporter Tintin

Tintin or Tin Tin may refer to:

''The Adventures of Tintin''

* ''The Adventures of Tintin'', a comics series by Belgian cartoonist Hergé

** Tintin (character), a fictional character in the series

** ''The Adventures of Tintin'' (film), 2011, ...

and his dog Snowy, who travel to the fictional Balkan nation of Syldavia

Syldavia ( Syldavian: ) is a fictional country in ''The Adventures of Tintin'', the comics series by Belgian cartoonist Hergé. It is located in the Balkans and has a rivalry with the fictional neighbouring country of Borduria. Syldavia is depic ...

, where they combat a plot to overthrow the monarchy of King Muskar XII.

''King Ottokar's Sceptre'' was a commercial success and was published in book form by Casterman

Casterman is a publisher of Franco-Belgian comics, specializing in comic books and children's literature. The company is based in Brussels, Belgium.

History

The company was founded in 1780 by Donat-Joseph Casterman, an editor and bookseller ...

shortly after its conclusion. Hergé continued ''The Adventures of Tintin'' with ''Land of Black Gold

''Land of Black Gold'' (french: link=no, Tintin au pays de l'or noir) is the fifteenth volume of ''The Adventures of Tintin'', the comics series by Belgian cartoonist Hergé. The story was commissioned by the conservative Belgian newspaper fo ...

'' until forced closure in 1940, while the series itself became a defining part of the Franco-Belgian comics tradition. In 1947, Hergé coloured and redrew ''King Ottokar's Sceptre'' in his distinctive style with the aid of Edgar P. Jacobs for Casterman

Casterman is a publisher of Franco-Belgian comics, specializing in comic books and children's literature. The company is based in Brussels, Belgium.

History

The company was founded in 1780 by Donat-Joseph Casterman, an editor and bookseller ...

's republication. The story introduces the recurring character Bianca Castafiore, and introduced the fictional countries of Syldavia and Borduria

Borduria (Cyrillic: Бордурија) is a fictional country in ''The Adventures of Tintin'', the comics series by Belgian cartoonist Hergé. It is located in the Balkans and has a rivalry with the fictional neighbouring country of Syldavia. ...

, both of which reappear in later stories. The first volume of the series to be translated into English, ''King Ottokar's Sceptre'' was adapted for both the 1956 Belvision Studios animation '' Hergé's Adventures of Tintin'' and for the 1991 Ellipse

In mathematics, an ellipse is a plane curve surrounding two focal points, such that for all points on the curve, the sum of the two distances to the focal points is a constant. It generalizes a circle, which is the special type of ellipse in ...

/Nelvana

Nelvana Enterprises, Inc. (; previously known as Nelvana Limited, sometimes known as Nelvana Animation and simply Nelvana or Nelvana Communications) is a Canadian animation studio and entertainment company owned by Corus Entertainment. Founded ...

animated series ''The Adventures of Tintin

''The Adventures of Tintin'' (french: Les Aventures de Tintin ) is a series of 24 bande dessinée#Formats, ''bande dessinée'' albums created by Belgians, Belgian cartoonist Georges Remi, who wrote under the pen name Hergé. The series was one ...

''.

Synopsis

Having discovered a lost briefcase in a Belgian park, Tintin returns it to its owner, the sigillographer Professor Hector Alembick, who informs the reporter of his plans to travel to the Balkan nation of Syldavia. Tintin discovers agents spying on the professor and follows those responsible to a nearby Syldavian restaurant. An unknown man agrees to meet with Tintin but is found unconscious and appears to haveamnesia

Amnesia is a deficit in memory caused by brain damage or disease,Gazzaniga, M., Ivry, R., & Mangun, G. (2009) Cognitive Neuroscience: The biology of the mind. New York: W.W. Norton & Company. but it can also be caused temporarily by the use ...

. Shortly after, the reporter receives a threatening note and is then the target of a bomb attack; Tintin survives the latter when police detectives Thomson and Thompson

Thomson and Thompson (french: Dupont et Dupond ) are fictional characters in ''The Adventures of Tintin'', the comics series by Belgian cartoonist Hergé. They are two incompetent detectives who provide much of the comic relief throughout the s ...

intercept the bomb. Suspecting that these events are linked to Syldavia, Tintin decides to accompany Professor Alembick on his forthcoming visit to the country. On the plane journey there, Tintin notices Alembick acting out of character, and suspects that an imposter has replaced him. Reading a brochure on Syldavian history, Tintin theorises that the imposter is part of a plot to steal the sceptre

A sceptre is a staff or wand held in the hand by a ruling monarch as an item of royal or imperial insignia. Figuratively, it means royal or imperial authority or sovereignty.

Antiquity

Ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia

The '' Was'' and other ...

of the medieval King Ottokar IV from the current King Muskar XII before St. Vladimir's Day, thus forcing him to abdicate.

Forcibly ejected from the plane by the pilot, Tintin survives and informs local police of his fears regarding the plot. However, the police captain is part of the conspiracy, and he organises an ambush in the woods where Tintin will be eliminated. Tintin evades death, and heads to the capital city of Klow in a car carrying the opera singer Bianca Castafiore. Leaving the car to evade Castafiore's singing, Tintin is arrested and survives another assassination attempt before heading to Klow on foot. Arriving in the city, he meets the King's '' aide-de-camp'', Colonel Boris Jorgen, and warns him of the plot. However, Jorgen is also a conspirator and organises a further unsuccessful assassination attempt aimed at Tintin. Meanwhile, the imposter pretending to be Alembick is allowed into Kropow Castle, where the sceptre is kept. Tintin finally succeeds in personally warning the King about the plot and they both rush to Kropow Castle, only to find that the sceptre is missing.

With the aid of Thomson and Thompson, who have recently arrived in Syldavia, Tintin discovers how the conspirators smuggled out the sceptre from the Castle and pursues the thieves, first by car and then by foot across the mountains. He is able to prevent the sceptre being carried over the border into neighbouring Borduria, discovering a letter on one of the conspirators. It reveals that the plot has been orchestrated by Müsstler, a political agitator who runs both the Syldavian Iron Guard and the Zyldav Zentral Revolutzionär Komitzät (ZZRK), a subversive organization which intends to have Borduria invade and annex Syldavia. Entering Borduria, Tintin commandeers a fighter plane and heads to Klow, but the Syldavian military shoot him down. Parachuting, he continues to Klow by foot, returning the sceptre to the King on St. Vladimir's Day and securing the monarchy. In return, the king makes Tintin a Knight of the Order of the Golden Pelican; the first foreigner to receive the honour. Tintin later learns that the imposter was Alembick's twin brother after police arrest Müsstler and rescue Professor Alembick.

History

Background

''King Ottokar's Sceptre'' was not the first Tintin adventure to draw specifically on contemporary events;

''King Ottokar's Sceptre'' was not the first Tintin adventure to draw specifically on contemporary events; Hergé

Georges Prosper Remi (; 22 May 1907 – 3 March 1983), known by the pen name Hergé (; ), from the French pronunciation of his reversed initials ''RG'', was a Belgian cartoonist. He is best known for creating ''The Adventures of Tintin'', ...

had for instance previously made use of the 1931 Japanese invasion of Manchuria

The Empire of Japan's Kwantung Army invaded Manchuria on 18 September 1931, immediately following the Mukden Incident. At the war's end in February 1932, the Japanese established the puppet state of Manchukuo. Their occupation lasted until the ...

as a political backdrop for the setting in '' The Blue Lotus''. This time, Hergé had closely observed the unfolding events surrounding the expansionist policies of Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

. In producing this story, he was particularly influenced by the ''Anschluss

The (, or , ), also known as the (, en, Annexation of Austria), was the annexation of the Federal State of Austria into the German Reich on 13 March 1938.

The idea of an (a united Austria and Germany that would form a " Greater Germa ...

'', the annexation of Austria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populous ...

by Nazi Germany in March 1938. The Munich Agreement

The Munich Agreement ( cs, Mnichovská dohoda; sk, Mníchovská dohoda; german: Münchner Abkommen) was an agreement concluded at Munich on 30 September 1938, by Germany, the United Kingdom, France, and Italy. It provided "cession to Germany ...

and the subsequent Nazi invasion of the Sudetenland followed in October 1938. Three weeks after ''King Ottokar's Sceptre'' finished serialisation, Germany invaded Poland. By this point, the threat to Belgian sovereignty posed by Nazi expansionism was becoming increasingly clear. By 1939, the events surrounding the Italian annexation of Albania made Hergé insist his editor publish the work to take advantage of current events as he felt "Syldavia is Albania". Later Hergé denied that he had just one country in mind.

Hergé claimed that the basic idea behind the story had been given to him by a friend; biographer Benoît Peeters

Benoît Peeters (; born 1956) is a French comics writer, novelist, and comics studies scholar.

Biography

After a degree in Philosophy at Université de Paris I, Peeters prepared his Master's at the École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales ...

suggested that the most likely candidate was school and scouting

Scouting, also known as the Scout Movement, is a worldwide youth Social movement, movement employing the Scout method, a program of informal education with an emphasis on practical outdoor activities, including camping, woodcraft, aquatics, hik ...

friend Philippe Gérard, who had warned of a second war with Germany for years. ''Tintin'' scholars have claimed Hergé did not develop the names ''Syldavia'' and ''Borduria'' himself; instead, the country names had supposedly appeared in a paper included in a 1937 edition of the ''British Journal of Psychology

The ''British Journal of Psychology'' is a quarterly peer-reviewed psychology journal. It was established in 1904 and is published by Wiley-Blackwell on behalf of the British Psychological Society. The editor-in-chief is Stefan R. Schweinberger ( ...

'', in which the author described a hypothetical conflict between a small kingdom and an annexing power. Reportedly, the paper, by Lewis Fry Richardson

Lewis Fry Richardson, FRS (11 October 1881 – 30 September 1953) was an English mathematician, physicist, meteorologist, psychologist, and pacifist who pioneered modern mathematical techniques of weather forecasting, and the application of s ...

and entitled "General Foreign Policy", explored the nature of inter-state conflict in a mathematical

Mathematics is an area of knowledge that includes the topics of numbers, formulas and related structures, shapes and the spaces in which they are contained, and quantities and their changes. These topics are represented in modern mathematics ...

way. Peeters attributed these claims to Georges Laurenceau, but said that "no researcher has confirmed this source". Instead, a paper by Richardson entitled "Generalized Foreign Politics: A Story in Group Psychology" was published in ''The British Journal of Psychology Monograph Supplements'' in 1939, but did not mention ''Syldavia'' or ''Borduria''. In any case, given the publication date, it is unlikely that it was an influence on ''King Ottokar's Sceptre''.

Hergé designed Borduria as a satirical depiction of Nazi Germany.

Hergé named the pro-Bordurian agitator "Müsstler" from the surnames of Nazi

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in ...

leader Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Germany from 1933 until his death in 1945. He rose to power as the leader of the Nazi Party, becoming the chancellor in 1933 and the ...

and Italy's National Fascist leader Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (; 29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who founded and led the National Fascist Party. He was Prime Minister of Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 until his deposition in ...

. The name also had similarities with the British Union of Fascists

The British Union of Fascists (BUF) was a British fascist political party formed in 1932 by Oswald Mosley. Mosley changed its name to the British Union of Fascists and National Socialists in 1936 and, in 1937, to the British Union. In 1939, f ...

' leader Oswald Mosley and the National Socialist Movement in the Netherlands

The National Socialist Movement in the Netherlands ( nl, Nationaal-Socialistische Beweging in Nederland, ; NSB) was a Dutch fascist and later Nazi political party that called itself a " movement". As a parliamentary party participating in legisl ...

' leader Anton Mussert

Anton may refer to: People

*Anton (given name), including a list of people with the given name

*Anton (surname)

Places

*Anton Municipality, Bulgaria

**Anton, Sofia Province, a village

*Antón District, Panama

**Antón, a town and capital of th ...

. Müsstler's group was named after the Iron Guard

The Iron Guard ( ro, Garda de Fier) was a Romanian militant revolutionary fascist movement and political party founded in 1927 by Corneliu Zelea Codreanu as the Legion of the Archangel Michael () or the Legionnaire Movement (). It was stron ...

, a Romanian fascist group that sought to oust King Carol II and forge a Romanian-German alliance. The Bordurian officers wore uniforms based on those of the German SS, while the Bordurian planes are German in design; in the original version Tintin escapes in a Heinkel He 112, while in the revised version this is replaced by a Messerschmitt Bf 109

The Messerschmitt Bf 109 is a German World War II fighter aircraft that was, along with the Focke-Wulf Fw 190, the backbone of the Luftwaffe's fighter force. The Bf 109 first saw operational service in 1937 during the Spanish Civil War an ...

. Hergé adopted the basis of Borduria's false flag operation to take over Syldavia from the plans outlined in Curzio Malaparte

Curzio Malaparte (; 9 June 1898 – 19 July 1957), born Kurt Erich Suckert, was an Italian writer, filmmaker, war correspondent and diplomat. Malaparte is best known outside Italy due to his works ''Kaputt'' (1944) and ''La pelle'' (1949). The f ...

's ''Tecnica del Colpo di Stato'' ("''The Technique of a Coup d'Etat''").

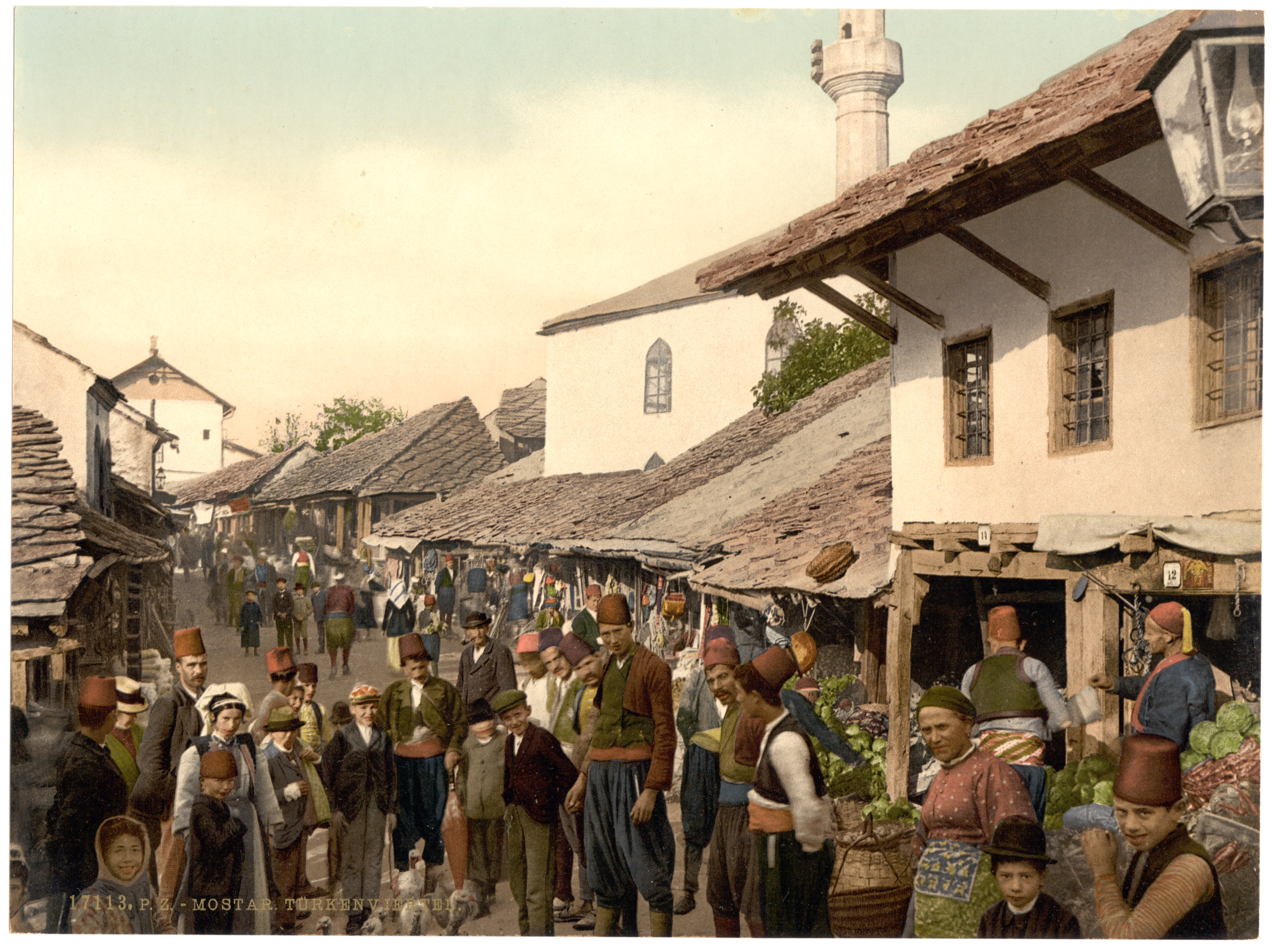

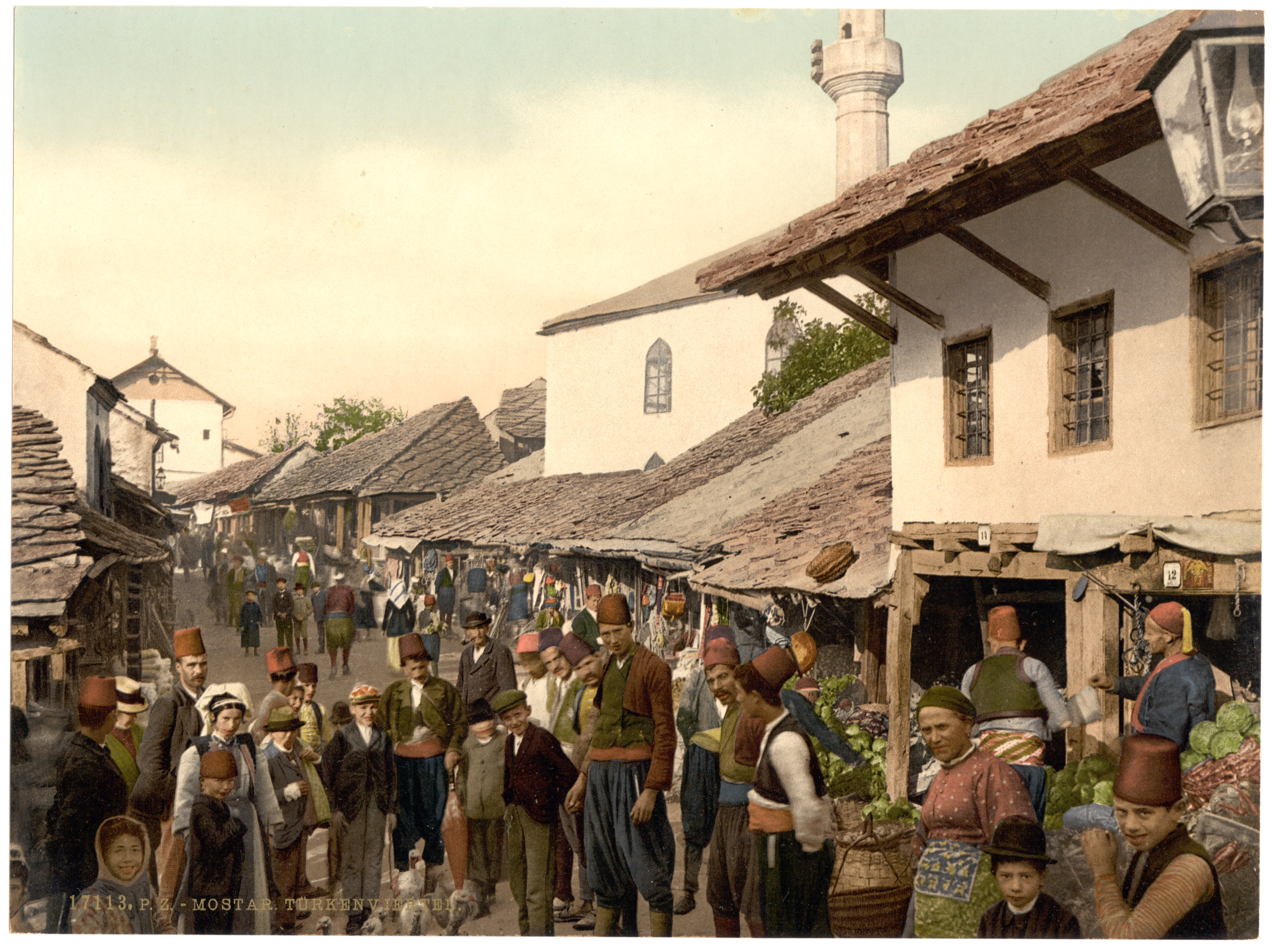

Syldavia's depiction was influenced by the costumes and cultures of Romania

Romania ( ; ro, România ) is a country located at the crossroads of Central Europe, Central, Eastern Europe, Eastern, and Southeast Europe, Southeastern Europe. It borders Bulgaria to the south, Ukraine to the north, Hungary to the west, S ...

and the neighboring Balkan region. The mosques that appear in Hergé's Syldavia are based on those found throughout the Balkans, while the appearance of the Syldavian village, featuring red-tiled roofs and minarets

A minaret (; ar, منارة, translit=manāra, or ar, مِئْذَنة, translit=miʾḏana, links=no; tr, minare; fa, گلدسته, translit=goldaste) is a type of tower typically built into or adjacent to mosques. Minarets are generally ...

, may have been specifically inspired by the Bosnia

Bosnia and Herzegovina ( sh, / , ), abbreviated BiH () or B&H, sometimes called Bosnia–Herzegovina and Pars pro toto#Geography, often known informally as Bosnia, is a country at the crossroads of Southern Europe, south and southeast Euro ...

n town of Mostar

, settlement_type = City

, image_skyline = Mostar (collage image).jpg

, image_caption = From top, left to right: A panoramic view of the heritage town site and the Neretva river from Lučki Bridge, Koski Mehmed Pasha ...

. Syldavia's mineral rich subsoil

Subsoil is the layer of soil under the topsoil on the surface of the ground. Like topsoil, it is composed of a variable mixture of small particles such as sand, silt and clay, but with a much lower percentage of organic matter and humus, and ...

could be taken as a reference to the uranium deposits

Uranium ore deposits are economically recoverable concentrations of uranium within the Earth's crust. Uranium is one of the more common elements in the Earth's crust, being 40 times more common than silver and 500 times more common than gold. It ...

found under Romania's Carpathian Mountains

The Carpathian Mountains or Carpathians () are a range of mountains forming an arc across Central Europe. Roughly long, it is the third-longest European mountain range after the Urals at and the Scandinavian Mountains at . The range stretche ...

– later to be mentioned directly in the eventual '' Destination Moon''. ''Tintin'' scholars have noted that the black pelican

Pelicans (genus ''Pelecanus'') are a genus of large water birds that make up the family Pelecanidae. They are characterized by a long beak and a large throat pouch used for catching prey and draining water from the scooped-up contents before ...

of Syldavia's flag resembles the black eagle of Albania's flag, and that Romania is the only European country to which pelicans are native.

The name Syldavia may be a composite of

The name Syldavia may be a composite of Transylvania

Transylvania ( ro, Ardeal or ; hu, Erdély; german: Siebenbürgen) is a historical and cultural region in Central Europe, encompassing central Romania. To the east and south its natural border is the Carpathian Mountains, and to the west the A ...

and Moldavia

Moldavia ( ro, Moldova, or , literally "The Country of Moldavia"; in Romanian Cyrillic: or ; chu, Землѧ Молдавскаѧ; el, Ἡγεμονία τῆς Μολδαβίας) is a historical region and former principality in Centr ...

, two regions with historical ties to Romania. Czech, Slovak, and Bohemian history influenced the Syldavian names, while several medieval Bohemian kings were the inspiration for the name "Ottokar". The Polish language

Polish (Polish: ''język polski'', , ''polszczyzna'' or simply ''polski'', ) is a West Slavic language of the Lechitic group written in the Latin script. It is spoken primarily in Poland and serves as the native language of the Poles. In ad ...

influenced Hergé's inclusion of ''–ow'' endings to the names of Syldavian places, while Polish history parallels Hergé's description of Syldavian history. The Syldavian language used in the book had French syntax but with Marollien vocabulary, a joke understood by the original Brussels-based readership.

However, despite its Eastern European location, Syldavia itself was partly a metaphor for Belgium – Syldavian King Muskar XII physically resembles King Leopold III of Belgium

Leopold III (3 November 1901 – 25 September 1983) was King of the Belgians from 23 February 1934 until his abdication on 16 July 1951. At the outbreak of World War II, Leopold tried to maintain Belgian neutrality, but after the German invas ...

. Hergé's decision to create a fictional Eastern European kingdom might have been influenced by Ruritania

Ruritania is a fictional country, originally located in central Europe as a setting for novels by Anthony Hope, such as ''The Prisoner of Zenda'' (1894). Nowadays the term connotes a quaint minor European country, or is used as a placeholder name f ...

, the fictional country created by Anthony Hope

Sir Anthony Hope Hawkins, better known as Anthony Hope (9 February 1863 – 8 July 1933), was a British novelist and playwright. He was a prolific writer, especially of adventure novels but he is remembered predominantly for only two books: '' T ...

for his novel ''The Prisoner of Zenda

''The Prisoner of Zenda'' is an 1894 adventure novel by Anthony Hope, in which the King of Ruritania is drugged on the eve of his coronation and thus is unable to attend the ceremony. Political forces within the realm are such that, in orde ...

'' (1894), which subsequently appeared in film adaptations in 1913

Events January

* January 5 – First Balkan War: Battle of Lemnos – Greek admiral Pavlos Kountouriotis forces the Turkish fleet to retreat to its base within the Dardanelles, from which it will not venture for the rest of the ...

, 1915

Events

Below, the events of World War I have the "WWI" prefix.

January

* January – British physicist Sir Joseph Larmor publishes his observations on "The Influence of Local Atmospheric Cooling on Astronomical Refraction".

* January ...

, 1922

Events

January

* January 7 – Dáil Éireann (Irish Republic), Dáil Éireann, the parliament of the Irish Republic, ratifies the Anglo-Irish Treaty by 64–57 votes.

* January 10 – Arthur Griffith is elected President of Dáil Éirean ...

, and 1937

Events

January

* January 1 – Anastasio Somoza García becomes President of Nicaragua.

* January 5 – Water levels begin to rise in the Ohio River in the United States, leading to the Ohio River flood of 1937, which continues into ...

. Many places within Syldavia are visually based on pre-existing European sites: the ''Diplodocus

''Diplodocus'' (, , or ) was a genus of diplodocid sauropod dinosaurs, whose fossils were first discovered in 1877 by S. W. Williston. The generic name, coined by Othniel Charles Marsh in 1878, is a neo-Latin term derived from Greek δ ...

'' in the Klow Natural History Museum is based on the one in the Museum für Naturkunde

The Natural History Museum (german: Museum für Naturkunde) is a natural history museum located in Berlin, Germany. It exhibits a vast range of specimens from various segments of natural history and in such domain it is one of three major muse ...

, Berlin

Berlin ( , ) is the capital and largest city of Germany by both area and population. Its 3.7 million inhabitants make it the European Union's most populous city, according to population within city limits. One of Germany's sixteen constitu ...

; the Syldavian Royal Palace is based on both the Charlottenburg Palace

Schloss Charlottenburg (Charlottenburg Palace) is a Baroque palace in Berlin, located in Charlottenburg, a district of the Charlottenburg-Wilmersdorf borough.

The palace was built at the end of the 17th century and was greatly expanded during th ...

, Berlin and the Royal Palace of Brussels; and Kropow Castle is based on Olavinlinna Castle, constructed in fifteenth century Savonia – a historical province of the Swedish Kingdom, located in modern-day Finland. For the revised version, Kropow Castle was drawn with an additional tower, inspired by Vyborg Castle, Russia. The United Kingdom also bore at least one influence on Syldavia, as King Muskar XII's carriage is based on the British Royal Family's Gold State Coach.

Original publication

''King Ottokar's Sceptre'' was first serialised in ''Le Petit Vingtième'' from 4 August 1938 to 10 August 1939 under the title ''Tintin En Syldavie'' ("''Tintin in Syldavia''"). It would prove to be the last Tintin adventure to be published in its entirety in ''Le Petit Vingtième''. From 14 May 1939, the story was also serialised in the French Catholic newspaper, ''Cœurs Vaillants

''Cœurs Vaillants'' (''Brave Hearts''), known later as ''J2 Jeunes'' and ''Formule 1'', was a Catholic French language weekly newspaper for French children. Founded in 1929 by ''l' Union des œuvres catholiques de France'' (The Union of Catholic ...

''.

In 1939, Éditions Casterman collected the story together in a single hardcover volume; Hergé insisted to his contact at Casterman, Charles Lesne, that they hurry up the process due to the changing political situation in Europe. The Nazi–Soviet Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact

, long_name = Treaty of Non-Aggression between Germany and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics

, image = Bundesarchiv Bild 183-H27337, Moskau, Stalin und Ribbentrop im Kreml.jpg

, image_width = 200

, caption = Stalin and Ribbentrop shaking ...

was signed the day Hergé delivered the book's remaining drawings; finishing touches included the book's original front cover, the royal coat of arms for the title page, and the tapestry depicting the Syldavian's 1127 victory over the Turks in "The Battle of Zileheroum" on page 20. Hergé suggested that for this publication, the story's title be changed to ''The Scepter of Ottokar IV''; Casterman changed this to ''King Ottokar's Sceptre''.

''King Ottokar's Sceptre'' introduced the recurring character of Bianca Castafiore to the series, who appears alongside her pianist Igor Wagner. It also witnessed the introduction of antagonist Colonel Jorgen, who reappears in the later Tintin adventures '' Destination Moon'' and its sequel ''Explorers on the Moon

''Explorers on the Moon'' (french: link=no, On a marché sur la Lune; literally: ''We walked on the Moon'') is the seventeenth volume of ''The Adventures of Tintin'', the comics series by Belgian cartoonist Hergé. The story was serialised we ...

''. The Alembick brothers' inclusion echoes the Balthazar brothers' inclusion in ''The Broken Ear

''The Broken Ear'' (french: link=no, L'Oreille cassée, originally published in English as ''Tintin and the Broken Ear'') is the sixth volume of ''The Adventures of Tintin'', the comics series by the Belgian cartoonist Hergé. Commissioned by ...

''.

After the conclusion of ''King Ottokar's Sceptre'', Hergé continued ''The Adventures of Tintin'' with ''Land of Black Gold

''Land of Black Gold'' (french: link=no, Tintin au pays de l'or noir) is the fifteenth volume of ''The Adventures of Tintin'', the comics series by Belgian cartoonist Hergé. The story was commissioned by the conservative Belgian newspaper fo ...

'' until Germany placed Belgium under occupation in 1940 and forced the closure of . The adventure ''Land of Black Gold'' had to be abandoned.

Second version, 1947

The story was redrawn and colourised in 1947. For this edition, Hergé was assisted by Edgar P. Jacobs. Jacobs oversaw changes to the costumes and background of the story; in the 1938 version, the Syldavian Royal Guards are dressed like BritishBeefeaters

The Yeomen Warders of His Majesty's Royal Palace and Fortress the Tower of London, and Members of the Sovereign's Body Guard of the Yeoman Guard Extraordinary, popularly known as the Beefeaters, are ceremonial guardians of the Tower of London. ...

, while the 1947 version has them dressed in a Balkanised uniform similar to the National Guards Unit of Bulgaria

The National Guards Unit of Bulgaria ( bg, Национална гвардейска част на България, translit=Natsionalna gvardeyska chast na Bulgaria) is a unique Bulgarian military formation of regimental size, directly subordin ...

. Jacobs also inserted a cameo of himself and his wife in the Syldavian royal court, while in that same scene is a cameo of Hergé, his then-wife Germaine, his brother Paul, and three of his friends – Édouard Cnaepelinckx, Jacques Van Melkebeke

Jacques Van Melkebeke (12 December 1904 – 8 June 1983) was a Belgian painter, journalist, writer, and comic strip writer. He was the first chief editor of Tintin magazine and wrote scripts and articles anonymously for many of their publicatio ...

, and Marcel Stobbaerts. Hergé and Jacobs also inserted further cameos of themselves at the bottom of page 38, where they appear as uniformed officers. While the character of Professor Alembick had been given the forename of Nestor in the original version, this was changed to Hector for the second; this had been done so as to avoid confusion with the character of Nestor, the butler of Marlinspike Hall

Marlinspike Hall (french: Le château de Moulinsart ) is Captain Haddock's country house and family estate in ''The Adventures of Tintin'', the comics series by Belgian cartoonist Hergé.

The original French name of the hall, ''Moulinsart'', ...

, whom Hergé had introduced in ''The Secret of the Unicorn

''The Secret of the Unicorn'' (french: link=no, Le Secret de La Licorne) is the eleventh volume of ''The Adventures of Tintin'', the comics series by Belgian cartoonist Hergé. The story was serialised daily in , Belgium's leading francophon ...

''. Editions Casterman published this second version in book form in 1947.

Subsequent publications and legacy

''King Ottokar's Sceptre'' became the first Tintin adventure to be published for a British audience when ''Eagle

Eagle is the common name for many large birds of prey of the family Accipitridae. Eagles belong to several groups of genera, some of which are closely related. Most of the 68 species of eagle are from Eurasia and Africa. Outside this area, j ...

'' serialised the comic in 1951. Here, the names of Tintin and Milou were retained, although the characters of Dupond and Dupont were renamed Thomson and Thompson; the latter two names would be adopted by translators Leslie Lonsdale-Cooper and Michael Turner when they translated the series into English for Methuen Publishing

Methuen Publishing Ltd is an English publishing house. It was founded in 1889 by Sir Algernon Methuen (1856–1924) and began publishing in London in 1892. Initially Methuen mainly published non-fiction academic works, eventually diversifying t ...

in 1958.

Casterman republished the original black-and-white version of the story in 1980, as part of the fourth volume in their collection. In 1988, they then published a facsimile version of that first edition.

Critical analysis

Harry Thompson described ''King Ottokar's Sceptre'' as a "biting political satire" and asserted that it was "courageous" of Hergé to have written it given that the threat of Nazi invasion was imminent. Describing it as a "classic

Harry Thompson described ''King Ottokar's Sceptre'' as a "biting political satire" and asserted that it was "courageous" of Hergé to have written it given that the threat of Nazi invasion was imminent. Describing it as a "classic locked room mystery

The "locked-room" or "impossible crime" mystery is a type of crime seen in crime and detective fiction. The crime in question, typically murder ("locked-room murder"), is committed in circumstances under which it appeared impossible for the perpet ...

", he praised its "tightly constructed plot". Ultimately, he deemed it one of the best three Tintin adventures written before World War II, alongside ''The Blue Lotus'' and ''The Black Island''. He also thought it noteworthy that in 1976, archaeologists discovered a sceptre belonging to a 13th-century King Ottokar in St. Vitus Cathedral

, native_name_lang = Czech

, image = St Vitus Prague September 2016-21.jpg

, imagesize = 300px

, imagelink =

, imagealt =

, landscape =

, caption ...

, Prague

Prague ( ; cs, Praha ; german: Prag, ; la, Praga) is the capital and largest city in the Czech Republic, and the historical capital of Bohemia. On the Vltava river, Prague is home to about 1.3 million people. The city has a temperate ...

. Hergé biographer Pierre Assouline believed that the story had the atmosphere of Franz Lehár

Franz Lehár ( ; hu, Lehár Ferenc ; 30 April 1870 – 24 October 1948) was an Austro-Hungarian composer. He is mainly known for his operettas, of which the most successful and best known is ''The Merry Widow'' (''Die lustige Witwe'').

Life a ...

's ''The Merry Widow

''The Merry Widow'' (german: Die lustige Witwe, links=no ) is an operetta by the Austro-Hungarian composer Franz Lehár. The librettists, Viktor Léon and Leo Stein, based the story – concerning a rich widow, and her countrymen's attempt ...

'', with "added touches" from the films of Erich von Stroheim

Erich Oswald Hans Carl Maria von Stroheim (born Erich Oswald Stroheim; September 22, 1885 – May 12, 1957) was an Austrian-American director, actor and producer, most noted as a film star and avant-garde, visionary director of the silent era. H ...

and Ernst Lubitsch

Ernst Lubitsch (; January 29, 1892November 30, 1947) was a German-born American film director, producer, writer, and actor. His urbane comedies of manners gave him the reputation of being Hollywood's most elegant and sophisticated director; as ...

. Fellow biographer Benoît Peeters thought that it exhibited "a political maturity" and "originality". Further, he felt that Hergé was able to break free from the "narrative limits fnbsp;... too much realism" by the use of Syldavia as a setting.

Jean-Marc Lofficier

Jean-Marc Lofficier (; born June 22, 1954) is a French author of books about films and television programs, as well as numerous comics and translations of a number of animation screenplays. He usually collaborates with his wife, Randy Lofficier (b ...

and Randy Lofficier called ''King Ottokar's Sceptre'' "a Hitchcockian thriller" which "recaptures the paranoid ambience" of ''Cigars of the Pharaoh

''Cigars of the Pharaoh'' (french: link=no, Les Cigares du pharaon) is the fourth volume of ''The Adventures of Tintin'', the series of comic albums by Belgian cartoonist Hergé. Commissioned by the conservative Belgian newspaper '' Le Vingti� ...

''. They compared the pace of the latter part of the story to that of Steven Spielberg

Steven Allan Spielberg (; born December 18, 1946) is an American director, writer, and producer. A major figure of the New Hollywood era and pioneer of the modern blockbuster, he is the most commercially successful director of all time. Sp ...

's ''Indiana Jones

''Indiana Jones'' is an American media franchise based on the adventures of Dr. Henry Walton "Indiana" Jones, Jr., a fictional professor of archaeology, that began in 1981 with the film '' Raiders of the Lost Ark''. In 1984, a prequel, '' Th ...

'' films before noting that despite the "horrors of the real world" that are present with Borduria's inclusion, they do not interfere in "the pure escapist nature of the adventure". Ultimately they awarded it three stars out of five.

Michael Farr

Michael Farr (born 1953) is a British expert on the comic series '' The Adventures of Tintin'' and its creator, Hergé. He has written several books on the subject as well as translating several others into English. A former reporter, he has al ...

opined that the adventure has "a convincingly authentic feel" due to the satirical portrayal to Nazi Germany, but that this was coupled with "sufficient scope for invention" with the creation of Syldavia. He compared it to Hitchcock's '' The Lady Vanishes''. Farr preferred the colour version assembled with E.P. Jacobs' aid, however. Deeming it "particularly successful", he thought that it was "one of the most polished and accomplished" adventures in the series, with a "perfectly paced and balanced" narrative that mixed drama and comedy successfully.

Literary critic Jean-Marie Apostolidès

Jean-Marie Apostolidès (; born 1943) is a Greek-French novelist, essayist, playwright, theater director, and university professor. He was born in Saint-Bonnet-Tronçais, France, on 27 November 1943.

Biography

Apostolidès grew up in Troyes, a ...

of Stanford University

Stanford University, officially Leland Stanford Junior University, is a private research university in Stanford, California. The campus occupies , among the largest in the United States, and enrolls over 17,000 students. Stanford is conside ...

asserted that the inclusion of the Iron Guard evoked Colonel François de La Rocque

François de La Rocque (; 6 October 1885 – 28 April 1946) was the leader of the French right-wing league the Croix de Feu from 1930 to 1936 before he formed the more moderate nationalist French Social Party (1936–1940), which has been ...

's Croix-de-Feu

, logo = Croix de Feu.svg

, logo_size = 200px

, leader1_title = President

, leader1_name = François de La Rocque

, foundation = 11 November 1927

, dissolution = 10 January 1936

, successor = F ...

. Noting that the figure of Müsstler was "the Evil One without a face", he expressed disbelief regarding Hergé's depiction of Syldavia, as there were no apparent economic problems or reasons why Müsstler's anti-monarchist conspiracy was so strong; thus, "mass revolution remains schematic".

Literary critic Tom McCarthy identified several instances in the story that he argued linked to wider themes within the ''Adventures of Tintin''. He identified a recurring host-and-guest theme in Alembick's visit to Syldavia, and believed that the theme of thieving was present in the story as Alembick's identity is stolen. Another theme identified within the series by McCarthy was that of the blurring between the sacred and the political; he saw echoes of this in ''King Ottokar's Sceptre'' as the King has to wait three days before appearing to the Syldavian public on St. Vladimir's Day, something that McCarthy thought linked to Jesus Christ

Jesus, likely from he, יֵשׁוּעַ, translit=Yēšūaʿ, label= Hebrew/ Aramaic ( AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ or Jesus of Nazareth (among other names and titles), was a first-century Jewish preacher and relig ...

and the Resurrection. McCarthy also opined that a number of characters in the book visually resembled Captain Haddock, a character who would be introduced in the subsequent Tintin adventure, ''The Crab with the Golden Claws''.

Adaptations

''King Ottokar's Sceptre'' was the first of ''The Adventures of Tintin'' to be adapted for the animated series '' Hergé's Adventures of Tintin''. The series was created by Belgium's Belvision Studios in 1957, directed by Ray Goossens and written by Greg. The studio divided ''King Ottokar's Sceptre'' into six 5-minute black-and-white episodes that diverged from Hergé's original plot in many ways. It was also adapted into a 1991 episode of ''The Adventures of Tintin

''The Adventures of Tintin'' (french: Les Aventures de Tintin ) is a series of 24 bande dessinée#Formats, ''bande dessinée'' albums created by Belgians, Belgian cartoonist Georges Remi, who wrote under the pen name Hergé. The series was one ...

'' television series by French studio Ellipse

In mathematics, an ellipse is a plane curve surrounding two focal points, such that for all points on the curve, the sum of the two distances to the focal points is a constant. It generalizes a circle, which is the special type of ellipse in ...

and Canadian animation company Nelvana

Nelvana Enterprises, Inc. (; previously known as Nelvana Limited, sometimes known as Nelvana Animation and simply Nelvana or Nelvana Communications) is a Canadian animation studio and entertainment company owned by Corus Entertainment. Founded ...

. The episode was directed by Stéphane Bernasconi, and Thierry Wermuth voiced the character of Tintin.

Tintin fans adopted the Syldavian language that appears in the story and used it to construct grammars and dictionaries, akin to the fan following of ''Star Trek

''Star Trek'' is an American science fiction media franchise created by Gene Roddenberry, which began with the eponymous 1960s television series and quickly became a worldwide pop-culture phenomenon. The franchise has expanded into vari ...

s Klingon

The Klingons ( ; Klingon: ''tlhIngan'' ) are a fictional species in the science fiction franchise ''Star Trek''.

Developed by screenwriter Gene L. Coon in 1967 for the original ''Star Trek'' (''TOS'') series, Klingons were swarthy humanoids c ...

and J. R. R. Tolkien's Elvish.

References

Notes

Footnotes

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * *External links

''King Ottokar's Sceptre''

at the Official Tintin Website

at Tintinologist.org {{Portal bar, Belgium, Comics 1939 graphic novels 1947 graphic novels Comics set in a fictional country Comics set in Europe Literature first published in serial form Methuen Publishing books Tintin books Works originally published in Le Petit Vingtième