King Idris I on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

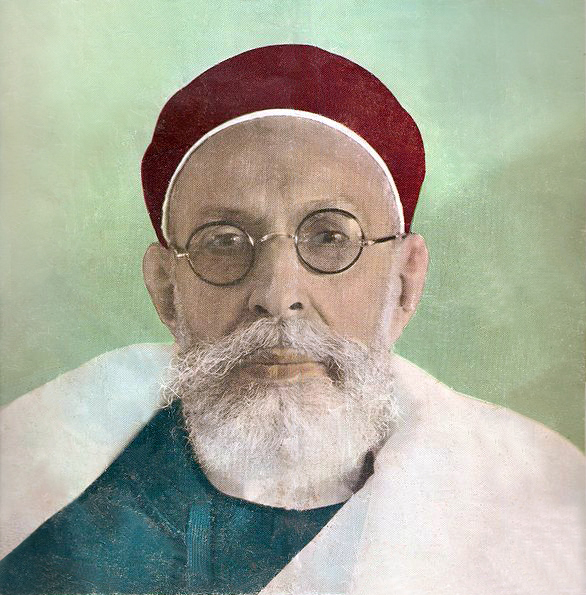

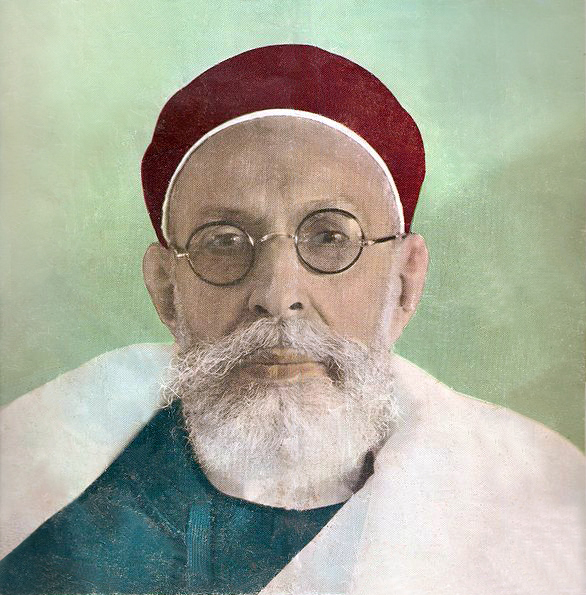

Muhammad Idris bin Muhammad al-Mahdi as-Senussi ( ar, إدريس, Idrīs; 13 March 1890 – 25 May 1983) was a

After the ''

After the ''

Following the outbreak of the

Following the outbreak of the

On 24 December 1951, Idris announced the establishment of the

On 24 December 1951, Idris announced the establishment of the  Under King Idris, Libya found itself within the Western sphere of influence. It became the recipient of Western expertise and aid, and by the end of 1959 it had received over $100 million of aid from the United States, being the single biggest per capita recipient of American aid. U.S. companies would also play a leading role in the development of the Libyan oil industry. This support was provided on a ''quid pro quo'' basis, and in return Libya granted the United States and United Kingdom usage of the

Under King Idris, Libya found itself within the Western sphere of influence. It became the recipient of Western expertise and aid, and by the end of 1959 it had received over $100 million of aid from the United States, being the single biggest per capita recipient of American aid. U.S. companies would also play a leading role in the development of the Libyan oil industry. This support was provided on a ''quid pro quo'' basis, and in return Libya granted the United States and United Kingdom usage of the  On April 26th 1963, King Idris abolished Libya's federal system. Both the provincial legislative assemblies and the provincial judicial systems were abolished. Doing so allowed him to concentrate economic and administrative planning at a centralised national level, and thenceforth all taxes and oil revenues were directed straight to the central government. As part of this reform, the "United Kingdom of Libya" was renamed the "Kingdom of Libya". This reform was not popular among many of Libya's provinces, which saw their power curtailed. According to the historian Dirk Vandewalle, this change was "the single most critical political act during the monarchy's tenure in office". The reform handed far greater political power to Idris than he had held previously. By the mid-1960s, Idris began to increasingly retreat from active involvement in the country's governance.

In 1955, failing to have produced a male heir, he convinced Queen Fatimah, his wife of 20 years, to let him marry a second wife, Aliya Abdel Lamloun, daughter of a wealthy Bedouin chief. The second marriage took place on 5 June 1955. Both wives then became pregnant, and each bore him a son.

On April 26th 1963, King Idris abolished Libya's federal system. Both the provincial legislative assemblies and the provincial judicial systems were abolished. Doing so allowed him to concentrate economic and administrative planning at a centralised national level, and thenceforth all taxes and oil revenues were directed straight to the central government. As part of this reform, the "United Kingdom of Libya" was renamed the "Kingdom of Libya". This reform was not popular among many of Libya's provinces, which saw their power curtailed. According to the historian Dirk Vandewalle, this change was "the single most critical political act during the monarchy's tenure in office". The reform handed far greater political power to Idris than he had held previously. By the mid-1960s, Idris began to increasingly retreat from active involvement in the country's governance.

In 1955, failing to have produced a male heir, he convinced Queen Fatimah, his wife of 20 years, to let him marry a second wife, Aliya Abdel Lamloun, daughter of a wealthy Bedouin chief. The second marriage took place on 5 June 1955. Both wives then became pregnant, and each bore him a son.

Idris was grand master of the following Libyan orders:

*

Idris was grand master of the following Libyan orders:

*

Imperial Order of the House of Osman 1st class (

Imperial Order of the House of Osman 1st class ( Nobility (Nishan-i-Majidieh) 2nd class (Ottoman Empire) (1918)

*

Nobility (Nishan-i-Majidieh) 2nd class (Ottoman Empire) (1918)

*

Honorary Knight Grand Cross of the

Honorary Knight Grand Cross of the  Grand Cordon of the

Grand Cordon of the  Grand Cross of the

Grand Cross of the  Grand Cordon of the Order of Independence (

Grand Cordon of the Order of Independence ( Grand Cordon of the

Grand Cordon of the  Grand Cross of the

Grand Cross of the  Grand Cross of the

Grand Cross of the

Libya

Libya (; ar, ليبيا, Lībiyā), officially the State of Libya ( ar, دولة ليبيا, Dawlat Lībiyā), is a country in the Maghreb region in North Africa. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to the north, Egypt to Egypt–Libya bo ...

n political and religious leader who was King of Libya

King is the title given to a male monarch in a variety of contexts. The female equivalent is queen regnant, queen, which title is also given to the queen consort, consort of a king.

*In the context of prehistory, antiquity and contempora ...

from 24 December 1951 until his overthrow on 1 September 1969. He ruled over the United Kingdom of Libya

The Kingdom of Libya ( ar, المملكة الليبية, lit=Libyan Kingdom, translit=Al-Mamlakah Al-Lībiyya; it, Regno di Libia), known as the United Kingdom of Libya from 1951 to 1963, was a constitutional monarchy in North Africa which ca ...

from 1951 to 1963, after which the country became known as simply the ''Kingdom of Libya''. Idris had served as Emir of Cyrenaica

Muhammad Idris bin Muhammad al-Mahdi as-Senussi ( ar, إدريس, Idrīs; 13 March 1890 – 25 May 1983) was a Libyan political and religious leader who was King of Libya from 24 December 1951 until his overthrow on 1 September 1969. He ruled o ...

and Tripolitania

Tripolitania ( ar, طرابلس '; ber, Ṭrables, script=Latn; from Vulgar Latin: , from la, Regio Tripolitana, from grc-gre, Τριπολιτάνια), historically known as the Tripoli region, is a historic region and former province o ...

from the 1920s until 1951. He was the chief of the Senussi

The Senusiyya, Senussi or Sanusi ( ar, السنوسية ''as-Sanūssiyya'') are a Muslim political-religious tariqa (Sufi order) and clan in colonial Libya and the Sudan region founded in Mecca in 1837 by the Grand Senussi ( ar, السنوسي ...

Muslim order.

Idris was born into the Senussi Order. When his cousin Ahmed Sharif as-Senussi abdicated as leader of the Order, Idris took his position. The Senussi campaign was taking place, with the British and Italians fighting the Order. Idris put an end to the hostilities and, through the Modus vivendi of Acroma

The ''modus vivendi'' of Acroma was a pair of agreements signed by the Sanūsī Order with Britain and Italy on 16 April 1917 at Acroma (ʿAkrama). E. E. Evans-Pritchard (1945), "The Sanusi of Cyrenaica", ''Africa'' 15(2): 61–79, esp. at 69.

...

, abandoned Ottoman protection. Between 1919 and 1920, Italy recognized Senussi control over most of Cyrenaica in exchange for the recognition of Italian sovereignty by Idris. Idris then led his Order in an unsuccessful attempt to conquer the eastern part of the Tripolitanian Republic

Tripolitanian Republic (Arabic: , ''al-Jumhuriyat at-Trabulsiya''), was an Arabs, Arab republic that declared the independence of Tripolitania from Italian Libya after World War I.

Background

Tripolitania had been an Ottoman possession since the ...

.

Following the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, the United Nations General Assembly

The United Nations General Assembly (UNGA or GA; french: link=no, Assemblée générale, AG) is one of the six principal organs of the United Nations (UN), serving as the main deliberative, policymaking, and representative organ of the UN. Curr ...

called for Libya to be granted independence. It established the United Kingdom of Libya through the unification of Cyrenaica, Tripolitania and Fezzan

Fezzan ( , ; ber, ⴼⵣⵣⴰⵏ, Fezzan; ar, فزان, Fizzān; la, Phazania) is the southwestern region of modern Libya. It is largely desert, but broken by mountains, uplands, and dry river valleys (wadis) in the north, where oases enable ...

, appointing Idris to rule it as king. Wielding significant political influence in the impoverished country, he banned political parties and in 1963 replaced Libya's federal system

Federalism is a combined or compound mode of government that combines a general government (the central or "federal" government) with regional governments ( provincial, state, cantonal, territorial, or other sub-unit governments) in a single po ...

with a unitary state

A unitary state is a sovereign state governed as a single entity in which the central government is the supreme authority. The central government may create (or abolish) administrative divisions (sub-national units). Such units exercise only th ...

. He established links to the Western powers, allowing the United Kingdom and United States to open military bases in the country in return for economic aid. After oil was discovered in Libya in 1959, he oversaw the emergence of a growing oil industry that rapidly aided economic growth. Idris' regime was weakened by growing Arab nationalist

Arab nationalism ( ar, القومية العربية, al-Qawmīya al-ʿArabīya) is a nationalist ideology that asserts the Arabs are a nation and promotes the unity of Arab people, celebrating the glories of Arab civilization, the language an ...

and Arab socialist

Arab socialism ( ar, الإشتِراكيّة العربية, Al-Ishtirākīya Al-‘Arabīya) is a political ideology based on the combination of pan-Arabism and socialism. Arab socialism is distinct from the much broader tradition of socialis ...

sentiment in Libya as well as rising frustration at the country's high levels of corruption and close links with Western nations. While in Turkey

Turkey ( tr, Türkiye ), officially the Republic of Türkiye ( tr, Türkiye Cumhuriyeti, links=no ), is a list of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country located mainly on the Anatolia, Anatolian Peninsula in Western Asia, with ...

for medical treatment, Idris was deposed in a 1969 ''coup d'état'' by army officers led by Muammar Gaddafi

Muammar Muhammad Abu Minyar al-Gaddafi, . Due to the lack of standardization of transcribing written and regionally pronounced Arabic, Gaddafi's name has been romanized in various ways. A 1986 column by ''The Straight Dope'' lists 32 spellin ...

.

Early life

Idris was born at Al-Jaghbub, the headquarters of theSenussi

The Senusiyya, Senussi or Sanusi ( ar, السنوسية ''as-Sanūssiyya'') are a Muslim political-religious tariqa (Sufi order) and clan in colonial Libya and the Sudan region founded in Mecca in 1837 by the Grand Senussi ( ar, السنوسي ...

movement, on 12 March 1889 (although some sources give the year as 1890), a son of Sayyid

''Sayyid'' (, ; ar, سيد ; ; meaning 'sir', 'Lord', 'Master'; Arabic plural: ; feminine: ; ) is a surname of people descending from the Prophets in Islam, Islamic prophet Muhammad through his grandsons, Hasan ibn Ali and Husayn ibn Ali ...

Muhammad al-Mahdi bin Sayyid Muhammad al-Senussi and his third wife Aisha bint Muqarrib al-Barasa. He was a grandson of Sayyid Muhammad ibn Ali as-Senussi

Muhammad ibn Ali as-Senussi (; in full Muḥammad ibn ʿAlī al-Sanūsī al-Mujāhirī al-Ḥasanī al-Idrīsī) (1787–1859) was an Algerian Muslim theologian and leader who founded the Senussi mystical order in 1837. His militant mystical move ...

, the founder of the Senussi Muslim

Muslims ( ar, المسلمون, , ) are people who adhere to Islam, a monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God of Abrah ...

Sufi

Sufism ( ar, ''aṣ-ṣūfiyya''), also known as Tasawwuf ( ''at-taṣawwuf''), is a mystic body of religious practice, found mainly within Sunni Islam but also within Shia Islam, which is characterized by a focus on Islamic spirituality, ...

Order and the Senussi tribe in North Africa. Idris's family claimed descent from the Islamic prophet Muhammad

Muhammad ( ar, مُحَمَّد; 570 – 8 June 632 Common Era, CE) was an Arab religious, social, and political leader and the founder of Islam. According to Muhammad in Islam, Islamic doctrine, he was a prophet Divine inspiration, di ...

through his daughter, Fatimah

Fāṭima bint Muḥammad ( ar, فَاطِمَة ٱبْنَت مُحَمَّد}, 605/15–632 CE), commonly known as Fāṭima al-Zahrāʾ (), was the daughter of the Islamic prophet Muhammad and his wife Khadija. Fatima's husband was Ali, th ...

. The Senussi were a revivalist Sunni

Sunni Islam () is the largest branch of Islam, followed by 85–90% of the world's Muslims. Its name comes from the word '' Sunnah'', referring to the tradition of Muhammad. The differences between Sunni and Shia Muslims arose from a disagr ...

Islamic sect who were based largely in Cyrenaica, a region in present-day eastern Libya. The Ottoman Sultan Abdul Hamid II

Abdülhamid or Abdul Hamid II ( ota, عبد الحميد ثانی, Abd ül-Hamid-i Sani; tr, II. Abdülhamid; 21 September 1842 10 February 1918) was the sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 31 August 1876 to 27 April 1909, and the last sultan to ...

sent his aide-de-camp Azmzade Sadik El Mueyyed to Jaghbub in 1886 and to Kufra in 1895 to cultivate positive relations with the Senussi and to counter the West European scramble for Africa

The Scramble for Africa, also called the Partition of Africa, or Conquest of Africa, was the invasion, annexation, division, and colonisation of Africa, colonization of most of Africa by seven Western Europe, Western European powers during a ...

. By the end of the nineteenth century the Senussi Order had established a government in Cyrenaica, unifying its tribes, controlling its pilgrimage

A pilgrimage is a journey, often into an unknown or foreign place, where a person goes in search of new or expanded meaning about their self, others, nature, or a higher good, through the experience. It can lead to a personal transformation, aft ...

and trade routes, and collecting taxes.

In 1916, Idris became chief of the Senussi order, following the abdication of his cousin Sayyid Ahmed Sharif es Senussi

Ahmed Sharif as-Senussi ( ar, أحمد الشريف السنوسي) (1873 – 10 March 1933) was the supreme leader of the Senussi order (1902–1933), although his leadership in the years 1917–1933 could be considered nominal. His daughter, ...

. He was recognized by the British under the new title "emir

Emir (; ar, أمير ' ), sometimes transliterated amir, amier, or ameer, is a word of Arabic origin that can refer to a male monarch, aristocrat, holder of high-ranking military or political office, or other person possessing actual or cerem ...

" of the territory of Cyrenaica

Cyrenaica ( ) or Kyrenaika ( ar, برقة, Barqah, grc-koi, Κυρηναϊκή ��παρχίαKurēnaïkḗ parkhíā}, after the city of Cyrene), is the eastern region of Libya. Cyrenaica includes all of the eastern part of Libya between ...

, a position also confirmed by the Italians in 1920. He was also installed as Emir of Tripolitania

Tripolitania ( ar, طرابلس '; ber, Ṭrables, script=Latn; from Vulgar Latin: , from la, Regio Tripolitana, from grc-gre, Τριπολιτάνια), historically known as the Tripoli region, is a historic region and former province o ...

on 28 July 1922.

Head of the Senussi Order: 1916–22

Regio Esercito

The Royal Italian Army ( it, Regio Esercito, , Royal Army) was the land force of the Kingdom of Italy, established with the proclamation of the Kingdom of Italy. During the 19th century Italy started to unify into one country, and in 1861 Manfre ...

'' (the Italian Royal Army) invaded Cyrenaica in 1913 as part of their wider invasion of Libya, the Senussi Order fought back against them. When the Order's leader, Ahmed Sharif as-Senussi, abdicated his position, he was replaced by Idris, who was his cousin. Pressured to do so by the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

, Ahmed had pursued armed attacks against British military forces stationed in the neighbouring Sultanate of Egypt

The Sultanate of Egypt () was the short-lived protectorate that the United Kingdom imposed over Egypt between 1914 and 1922.

History

Soon after the start of the First World War, Khedive Abbas II of Egypt was removed from power by the British ...

(formerly known, until December 1914, as the Khedivate of Egypt

The Khedivate of Egypt ( or , ; ota, خدیویت مصر ') was an autonomous tributary state of the Ottoman Empire, established and ruled by the Muhammad Ali Dynasty following the defeat and expulsion of Napoleon Bonaparte's forces which brou ...

). On taking power, Idris put a stop to these attacks.

Instead he established a tacit alliance with the British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts esta ...

, which would last for half a century and accord his Order ''de facto'' diplomatic status. Using the British as intermediaries, Idris led the Order into negotiations with the Italians in July 1916. These resulted in two agreements, at al-Zuwaytina in April 1916 and at Akrama in April 1917. The latter of these treaties left most of inland Cyrenaica under the control of the Senussi Order.

Relations between the Senussi Order and the newly established Tripolitanian Republic

Tripolitanian Republic (Arabic: , ''al-Jumhuriyat at-Trabulsiya''), was an Arabs, Arab republic that declared the independence of Tripolitania from Italian Libya after World War I.

Background

Tripolitania had been an Ottoman possession since the ...

were acrimonious. The Senussi attempted to militarily extend their power into eastern Tripolitania, resulting in a pitched battle at Bani Walid in which the Senussi were forced to withdraw back into Cyrenaica.

At the end of the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, the Ottoman Empire ceded their claims over Libya to the Kingdom of Italy

The Kingdom of Italy ( it, Regno d'Italia) was a state that existed from 1861, when Victor Emmanuel II of Kingdom of Sardinia, Sardinia was proclamation of the Kingdom of Italy, proclaimed King of Italy, until 1946, when civil discontent led to ...

. Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical re ...

, however, was facing serious economic, social, and political problems domestically, and was not prepared to re-launch its military activities in Libya. It issued statutes known as the ''Legge Fondamentale'', for the Tripolitanian Republic in June 1919 and Cyrenaica in October 1919. These were a compromise by which all Libyans were accorded the right to joint Libyan-Italian citizenship, while each province was to have its own parliament and governing council. The Senussi were largely happy with this arrangement and Idris visited Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus (legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

as part of the celebrations to mark the promulgation of the settlement. In October 1920, further negotiations between Italy and Cyrenaica resulted in the Accord of al-Rajma

Accord may refer to:

Businesses and products

* Honda Accord, a car manufactured by the Honda Motor Company

* Accord (cigarette), a brand of Rothmans, Benson & Hedges

* Accord (company), a former public services provider in south England

* Accor ...

, in which Idris was given the title of Emir of Cyrenaica

Muhammad Idris bin Muhammad al-Mahdi as-Senussi ( ar, إدريس, Idrīs; 13 March 1890 – 25 May 1983) was a Libyan political and religious leader who was King of Libya from 24 December 1951 until his overthrow on 1 September 1969. He ruled o ...

and permitted to administer autonomously the oases around Kufra

Kufra () is a basinBertarelli (1929), p. 514. and oasis group in the Kufra District of southeastern Cyrenaica in Libya. At the end of nineteenth century Kufra became the centre and holy place of the Senussi order. It also played a minor role in ...

, Jalu

Jalu, Jallow, or Gialo ( ar, جالو) is a town in the Al Wahat District in northeastern Libya in the Jalo oasis. An oasis, a city, and it is the main center of the oasis region in eastern Libya. It is located at the confluence of longitude an ...

, Jaghbub

Jaghbub ( ar, الجغبوب) is a remote desert village in the Al Jaghbub Oasis in the eastern Libyan Desert. It is actually closer to the Egyptian town of Siwa than to any Libyan town of note. The oasis is located in Butnan District and was th ...

, Awjila, and Ajdabiya. As part of the Accord he was given a monthly stipend by the Italian government, who agreed to take responsibility for policing and administration of areas under Senussi control. The Accord also stipulated that Idris must fulfill the requirements of the ''Legge Fondamentale'' by disbanding the Cyrenaican military units, but he did not comply with this. By the end of 1921, relations between the Senussi Order and the Italian government had again deteriorated.

Following the death of Tripolitanian leader Ramadan Asswehly Ramadan Sewehli, also spelt as Ramadan al-Suwayhili, ( ar, رمضان السويحلي ''Ramaḍān as-Swīḥlī'') (c. 1879 – 1920) was a prominent Tripolitanian nationalist at the outset of the Italian occupation in 1911 and one of the founders ...

in August 1920, the Republic descended into civil war. Many tribal leaders in the region recognized that this discord was weakening the region's chances of attaining full autonomy from Italy, and in November 1920 they met in Gharyan

Gharyan is a city in northwestern Libya, in Jabal al Gharbi District, located 80 km south of Tripoli. Prior to 2007, it was the administrative seat of Gharyan District. Gharyan is one of the largest towns in the Western Mountains.

In 2005, ...

to bring an end to the violence. In January 1922 they agreed to request that Idris extend the Emirate of Cyrenaica into Tripolitania in order to bring stability; they presented a formal document with this request on 28 July 1922. Idris' advisers were divided on whether he should accept the offer or not. Doing so would contravene the al-Rajma Agreement and would damage relations with the Italian government, who opposed the political unification of Cyrenaica and Tripolitania as being against their interests. Nevertheless, in November 1922 Idris agreed to the proposal.

Exile: 1922–1951

Following the agreement, Emir Idris feared that Italy—under its new Fascist leaderBenito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (; 29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who founded and led the National Fascist Party. He was Prime Minister of Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 until his deposition in 194 ...

—would militarily retaliate against the Senussi Order, and so he went into exile in the newly established Kingdom of Egypt

The Kingdom of Egypt ( ar, المملكة المصرية, Al-Mamlaka Al-Miṣreyya, The Egyptian Kingdom) was the legal form of the Egyptian state during the latter period of the Muhammad Ali dynasty's reign, from the United Kingdom's recog ...

(formerly known as the Sultanate of Egypt

The Sultanate of Egypt () was the short-lived protectorate that the United Kingdom imposed over Egypt between 1914 and 1922.

History

Soon after the start of the First World War, Khedive Abbas II of Egypt was removed from power by the British ...

) in December 1922. Soon, the Italian reconquest of Libya began, and by the end of 1922 the only effective anti-colonial resistance to the occupation was concentrated in the Cyrenaican hinterlands. The Italians subjugated the Libyan people; Cyrenaica's livestock was decimated, a large portion of its population was interned in concentration camps, and between 1930 and 1931 an estimated 12,000 Cyrenaicans were executed by the ''Regio Esercito

The Royal Italian Army ( it, Regio Esercito, , Royal Army) was the land force of the Kingdom of Italy, established with the proclamation of the Kingdom of Italy. During the 19th century Italy started to unify into one country, and in 1861 Manfre ...

'' (Italian Royal Army). The Italian government implemented a policy of "demographic colonization", by which tens of thousands of Italians were relocated to Libya, largely to establish farms.

Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

in September 1939, Idris supported the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and North ...

—which was now at war with Italy—in the hope of ridding his country of Italian occupation. He argued that even if the Italians were victorious, the situation for the Libyan people would be no different than it had been before the war. Delegates from both the Cyrenaicans and Tripolitanians agreed that Idris should conclude agreements with the British that they would gain independence in return for support during the war. Privately, Idris did not promote the idea of Libyan independence to the British, instead suggesting that it become a British protectorate akin to Transjordan Transjordan may refer to:

* Transjordan (region), an area to the east of the Jordan River

* Oultrejordain, a Crusader lordship (1118–1187), also called Transjordan

* Emirate of Transjordan, British protectorate (1921–1946)

* Hashemite Kingdom of ...

. A Libyan Arab Force The Libyan Arab Force, also known as the known as the Sanusi Army, consisting of five infantry battalions made up of volunteers, was established to aid the British war effort. With the exception of one military engagement near to Benghazi, this fo ...

, consisting of five infantry battalions made up of volunteers, was established to aid the British war effort. With the exception of one military engagement near to Benghazi

Benghazi () , ; it, Bengasi; tr, Bingazi; ber, Bernîk, script=Latn; also: ''Bengasi'', ''Benghasi'', ''Banghāzī'', ''Binghāzī'', ''Bengazi''; grc, Βερενίκη (''Berenice'') and ''Hesperides''., group=note (''lit. Son of he Ghazi ...

, this force's role did not extend beyond support and gendarmerie duties.

After the defeat of the Italian armies, Libya was left under the military control of British and French forces. They governed the area until 1949 according to the Hague Convention of 1907

The Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907 are a series of international treaties and declarations negotiated at two international peace conferences at The Hague in the Netherlands. Along with the Geneva Conventions, the Hague Conventions were amo ...

. In 1946, a National Congress was established to lay the groundwork for independence; it was dominated by the Senussi Order. Under British and French pressure, Italy relinquished its claim of sovereignty over the country in 1947, although still hoping that they would be permitted a trusteeship over Tripolitania. The European powers drew up the Bevin-Sforza plan, which proposed that France retain a ten-year trusteeship in Fezzan, the UK in Cyrenaica, and Italy in Tripolitania. After the plans were published in May 1949, they generated violent demonstrations in Tripolitania and Cyrenaica and drew protests from the United States, Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

, and other Arab states. In September 1948, the question of Libya's future was brought to the United Nations General Assembly

The United Nations General Assembly (UNGA or GA; french: link=no, Assemblée générale, AG) is one of the six principal organs of the United Nations (UN), serving as the main deliberative, policymaking, and representative organ of the UN. Curr ...

, which rejected the principles of the Bevin-Sforza plan, instead indicating support for full independence. At the time neither the UK nor France supported the principle of Libyan unification, with France being keen to retain colonial control of Fezzan. In 1949 the British unilaterally declared that they would leave Cyrenaica and grant it independence under the control of Idris; by doing so they believed that it would remain under their own sphere of influence. Similarly, France established a provisional government in Fezzan in February 1950.

In November 1949, the UN General Assembly adopted a resolution on Libyan independence, stipulating that it must come into being by January 1952. The resolution called for Libya to become a single state led by Idris, who was to be declared king of Libya. He had been reluctant to accept the position. Both the United Kingdom and the United States—who were committed to preventing any growth in Soviet influence in the southern Mediterranean—agreed to this for their own Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because the ...

strategic reasons. They recognised that while they would be able to establish military bases in an independent Libyan state sympathetic to their interests, they would have been unable to do so were Libya to have entered UN-sponsored trusteeship. The Tripolitanians—largely united under Selim Muntasser and the United National Front—agreed to this plan in order to avoid further European colonial rule. The concept of a kingdom would be alien to Libyan society, where the loyalties to the family, tribe, and region—or alternately to the global Muslim community—were far stronger than to any concept of Libyan nationhood.

King of Libya: 1951–1969

On 24 December 1951, Idris announced the establishment of the

On 24 December 1951, Idris announced the establishment of the United Kingdom of Libya

The Kingdom of Libya ( ar, المملكة الليبية, lit=Libyan Kingdom, translit=Al-Mamlakah Al-Lībiyya; it, Regno di Libia), known as the United Kingdom of Libya from 1951 to 1963, was a constitutional monarchy in North Africa which ca ...

from the al-Manar Palace in Benghazi. The country had a population of approximately one million, the majority of whom were Arabs, but with Berber, Tebu, Sephardi Jewish

Sephardic (or Sephardi) Jews (, ; lad, Djudíos Sefardíes), also ''Sepharadim'' , Modern Hebrew: ''Sfaradim'', Tiberian: Səp̄āraddîm, also , ''Ye'hude Sepharad'', lit. "The Jews of Spain", es, Judíos sefardíes (or ), pt, Judeus sefa ...

, Greek, Turkish, and Italian minorities. The newly established state faced serious problems; in 1951, Libya was one of the world's poorest countries. Much of its infrastructure had been destroyed by war, it had very little trade and high unemployment, and both a 40% infant mortality rate and a 94% illiteracy rate. Only 1% of Libya's land mass was arable, with another 3–4% being used for pastoral farming. Although the three provinces had been united, they shared little common aspiration.

The Kingdom was established along federal

Federal or foederal (archaic) may refer to:

Politics

General

*Federal monarchy, a federation of monarchies

*Federation, or ''Federal state'' (federal system), a type of government characterized by both a central (federal) government and states or ...

lines, something that Cyrenaica and Fezzan had insisted upon, fearing that they would otherwise be dominated by Tripolitania, where two-thirds of the Libyan population lived. Conversely, the Tripolitanians had largely favoured a unitary state, believing that it would allow the government to act more effectively in the national interest

The national interest is a sovereign state's goals and ambitions (economic, military, cultural, or otherwise), taken to be the aim of government.

Etymology

The Italian phrase ''ragione degli stati'' was first used by Giovanni della Casa around t ...

and fearing that a federal system would result in further British and French domination of Libya. The three provinces had their own legislative authorities; while that of Fezzan was composed entirely of elected officials, those of Cyrenaica and Tripolitania contained a mix of elected and non-elected representatives. This constitutional framework left Libya with a weak central government and strong provincial autonomy. The governments of successive Prime Ministers tried to push through economic policies but found them hampered by the differing provinces. There remained a persistent distrust between Cyrenaica and Tripolitania. Benghazi and Tripoli were appointed as joint capital cities, with the country's parliament moving between the two. The city of Bayda also became a ''de facto'' summer capital as Idris moved there.

According to the reporter Jonathan Bearman, King Idris was "nominally a constitutional monarch" but in practice was "a spiritual leader with autocratic temporal power", with Libya being a "monarchical dictatorship" rather than a constitutional monarchy

A constitutional monarchy, parliamentary monarchy, or democratic monarchy is a form of monarchy in which the monarch exercises their authority in accordance with a constitution and is not alone in decision making. Constitutional monarchies dif ...

or parliamentary democracy

A parliamentary system, or parliamentarian democracy, is a system of democratic governance of a state (or subordinate entity) where the executive derives its democratic legitimacy from its ability to command the support ("confidence") of the ...

. The new constitution granted Idris significant personal power, and he remained a crucial player in the country's political system. Idris ruled via a palace cabinet, namely his royal '' diwan'', which contained a ''chef de cabinet'', two deputies, and senior advisers. This ''diwan'' worked in consultation with the federal government to determine the policies of the Libyan state.

King Idris was a self-effacing devout Muslim, he refused to allow his portrait to be featured on Libyan currency and also insisted that nothing should be named after him except the Tripoli Idris Airport. Idris' regime soon banned political parties from operating in the country, claiming that they exacerbated internal instability. From 1952 onward, all candidates for election were government nominees. In 1954, the Prime Minister Mustafa Ben Halim

Mustafa Ahmed Ben Halim ( ar, مصطفى احمد بن حليم; 29 January 1921 – 7 December 2021) was a Libyan politician and businessman who served in a number of leadership positions in the Kingdom of Libya from 1953 to 1960. Ben Halim wa ...

suggested that Libya be converted from a federal to a unitary system and that Idris be proclaimed President for Life. Idris recognised that this would deal with the problems caused by federalism and would put a stop to the intrigues among the Senussi family surrounding his succession. He asked Ben Halim to produce a formal draft for these plans, but the idea was dropped amid opposition from Cyrenaican tribal chiefs.

Under King Idris, Libya found itself within the Western sphere of influence. It became the recipient of Western expertise and aid, and by the end of 1959 it had received over $100 million of aid from the United States, being the single biggest per capita recipient of American aid. U.S. companies would also play a leading role in the development of the Libyan oil industry. This support was provided on a ''quid pro quo'' basis, and in return Libya granted the United States and United Kingdom usage of the

Under King Idris, Libya found itself within the Western sphere of influence. It became the recipient of Western expertise and aid, and by the end of 1959 it had received over $100 million of aid from the United States, being the single biggest per capita recipient of American aid. U.S. companies would also play a leading role in the development of the Libyan oil industry. This support was provided on a ''quid pro quo'' basis, and in return Libya granted the United States and United Kingdom usage of the Wheelus Air Base

Wheelus Air Base was a United States Air Force base located in British-occupied Libya and the Kingdom of Libya from 1943 to 1970. At one time it was the largest US military facility outside the US. It had an area of on the coast of Tripoli. T ...

and the al-Adem Air Base. This reliance on the Western nations placed Libya at odds with the growing Arab nationalist

Arab nationalism ( ar, القومية العربية, al-Qawmīya al-ʿArabīya) is a nationalist ideology that asserts the Arabs are a nation and promotes the unity of Arab people, celebrating the glories of Arab civilization, the language an ...

and Arab socialist

Arab socialism ( ar, الإشتِراكيّة العربية, Al-Ishtirākīya Al-‘Arabīya) is a political ideology based on the combination of pan-Arabism and socialism. Arab socialism is distinct from the much broader tradition of socialis ...

sentiment across the Arab world. The Arab nationalist sentiment promoted by ''Radio Cairo

Egyptian Radio also known as the Egyptian Radio's General Program (إذاعة البرنامج العام transliterated as Iza'at El-Bernameg Al-Aam) also popularly known as Radio Cairo (in Arabic إذاعة القاهرة transliterated as Iza'at ...

'' found a particularly receptive audience in Tripolitania. In July 1967, anti-Western riots broke out in Tripoli and Benghazi to protest the West's support of Israel against the Arab states in the Six-Day War

The Six-Day War (, ; ar, النكسة, , or ) or June War, also known as the 1967 Arab–Israeli War or Third Arab–Israeli War, was fought between Israel and a coalition of Arab world, Arab states (primarily United Arab Republic, Egypt, S ...

. Many oil workers across Libya went on strike in solidarity with the Arab forces fighting Israel.

During the 1950s, a number of foreign companies began prospecting for oil in Libya, with the country's government passing the Minerals Law of 1953 and then the Petroleum Law of 1955 to regulate this process. In 1959 oil was discovered in Libya. The 1955 law created conditions that enabled small oil companies to drill alongside larger corporations; each concession had a low entry fee, with rents only increasing significantly after the eighth year of drilling. This created a competitive atmosphere that prevented any one company from becoming crucial to the country's oil operation, although it had the downside of incentivising companies to produce as much oil as possible in as quick a period as possible. Libya's oil fields fuelled rapidly growing demand in Europe, and by 1967 it was supplying a third of the oil entering the West European market. Within a few years, Libya had grown to become the world's fourth largest oil producer. Oil production provided a huge boost to the Libyan economy; whereas the per capita annual income in 1951 had been $25–35, by 1969 it was $2000. By 1961, the oil industry was exerting the greater influence over Libyan politics than any other issue. In 1962, Libya joined the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries

The Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC, ) is a cartel of countries. Founded on 14 September 1960 in Baghdad by the first five members (Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, and Venezuela), it has, since 1965, been headquart ...

(OPEC). In ensuing years the Libyan state furthered its control over the industry, establishing a Ministry of Petroleum Affairs in 1963 and then the Libyan National Oil Company. In 1968 they established the Libyan Petroleum Company (LIPETCO) and announced that any further concession agreements would have to be joint ventures with LIPETCO.

Libya experienced rampant corruption and favouritism. A number of high-profile corruption scandals impacted on the highest levels of Idris' government. In June 1960 Idris issued a public letter in which he condemned this corruption, claiming that bribery and nepotism "will destroy the very existence of the state and its good reputation both at home and abroad".

On April 26th 1963, King Idris abolished Libya's federal system. Both the provincial legislative assemblies and the provincial judicial systems were abolished. Doing so allowed him to concentrate economic and administrative planning at a centralised national level, and thenceforth all taxes and oil revenues were directed straight to the central government. As part of this reform, the "United Kingdom of Libya" was renamed the "Kingdom of Libya". This reform was not popular among many of Libya's provinces, which saw their power curtailed. According to the historian Dirk Vandewalle, this change was "the single most critical political act during the monarchy's tenure in office". The reform handed far greater political power to Idris than he had held previously. By the mid-1960s, Idris began to increasingly retreat from active involvement in the country's governance.

In 1955, failing to have produced a male heir, he convinced Queen Fatimah, his wife of 20 years, to let him marry a second wife, Aliya Abdel Lamloun, daughter of a wealthy Bedouin chief. The second marriage took place on 5 June 1955. Both wives then became pregnant, and each bore him a son.

On April 26th 1963, King Idris abolished Libya's federal system. Both the provincial legislative assemblies and the provincial judicial systems were abolished. Doing so allowed him to concentrate economic and administrative planning at a centralised national level, and thenceforth all taxes and oil revenues were directed straight to the central government. As part of this reform, the "United Kingdom of Libya" was renamed the "Kingdom of Libya". This reform was not popular among many of Libya's provinces, which saw their power curtailed. According to the historian Dirk Vandewalle, this change was "the single most critical political act during the monarchy's tenure in office". The reform handed far greater political power to Idris than he had held previously. By the mid-1960s, Idris began to increasingly retreat from active involvement in the country's governance.

In 1955, failing to have produced a male heir, he convinced Queen Fatimah, his wife of 20 years, to let him marry a second wife, Aliya Abdel Lamloun, daughter of a wealthy Bedouin chief. The second marriage took place on 5 June 1955. Both wives then became pregnant, and each bore him a son.

Overthrow and exile

King Idris used the oil money to strengthen family and tribal alliances that would support the monarchy, rather than using it to build up the economic or political apparatus of the state. According to Vandewalle, King Idris "showed no real interest in ruling the three provinces as a unified political community". Idris' regime had little support outside Cyrenaica. It had been weakened by endemic corruption and cronyism in the country, and growingArab nationalist

Arab nationalism ( ar, القومية العربية, al-Qawmīya al-ʿArabīya) is a nationalist ideology that asserts the Arabs are a nation and promotes the unity of Arab people, celebrating the glories of Arab civilization, the language an ...

sentiment following the 1967 Six-Day War

The Six-Day War (, ; ar, النكسة, , or ) or June War, also known as the 1967 Arab–Israeli War or Third Arab–Israeli War, was fought between Israel and a coalition of Arab world, Arab states (primarily United Arab Republic, Egypt, S ...

.

On 1 September 1969, while King Idris was in Turkey

Turkey ( tr, Türkiye ), officially the Republic of Türkiye ( tr, Türkiye Cumhuriyeti, links=no ), is a list of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country located mainly on the Anatolia, Anatolian Peninsula in Western Asia, with ...

for medical treatment, he was deposed in a coup d'état

A coup d'état (; French for 'stroke of state'), also known as a coup or overthrow, is a seizure and removal of a government and its powers. Typically, it is an illegal seizure of power by a political faction, politician, cult, rebel group, m ...

by a group of Libyan Army officers under the leadership of Muammar Gaddafi

Muammar Muhammad Abu Minyar al-Gaddafi, . Due to the lack of standardization of transcribing written and regionally pronounced Arabic, Gaddafi's name has been romanized in various ways. A 1986 column by ''The Straight Dope'' lists 32 spellin ...

. The monarchy was abolished and a republic proclaimed. The coup pre-empted King Idris's intended abdication and the succession of his heir the following day. From Turkey, he and the Queen traveled to Kamena Vourla

Kamena Vourla ( el, Καμένα Βούρλα, lit=Burnt Rushes, ) is a town and a municipality in Phthiotis, Greece. At the 2011 local government reform it became part of the municipality ''Molos-Agios Konstantinos'' (of which it became the sea ...

, Greece

Greece,, or , romanized: ', officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the southern tip of the Balkans, and is located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Greece shares land borders with ...

, by ship and went into exile in Egypt. After the 1969 coup, King Idris was put on trial ''in absentia'' in the Libyan People's Court

The Libyan People's Court is an emergency tribunal founded in Libya after the revolution of 1 September 1969. Although its initial purpose was to try the officials of the overthrown Kingdom, many others also were tried by this court. This article ...

and sentenced to death in November 1971.

Muammar Gaddafi's regime portrayed King Idris's administration as having been weak, inept, corrupt, anachronistic, and lacking in nationalist credentials, a presentation of it that would come to be widely adopted.

In 1983, at the age of 93, King Idris died in a hospital in the district of Dokki

Dokki ( ar, الدقي , is one of nine districts that make up Giza city, which is part of Greater Cairo, in Egypt. Dokki is situated on the western bank of the Nile, directly across from Downtown Cairo. It is a vital residential and comme ...

in Cairo

Cairo ( ; ar, القاهرة, al-Qāhirah, ) is the capital of Egypt and its largest city, home to 10 million people. It is also part of the largest urban agglomeration in Africa, the Arab world and the Middle East: The Greater Cairo metro ...

. He was buried at Al-Baqi' Cemetery, Medina

Medina,, ', "the radiant city"; or , ', (), "the city" officially Al Madinah Al Munawwarah (, , Turkish: Medine-i Münevvere) and also commonly simplified as Madīnah or Madinah (, ), is the Holiest sites in Islam, second-holiest city in Islam, ...

, Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia, officially the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA), is a country in Western Asia. It covers the bulk of the Arabian Peninsula, and has a land area of about , making it the fifth-largest country in Asia, the second-largest in the A ...

.

Legacy

According to Vandewalle, King Idris' monarchy "started Libya on the road of political exclusion of its citizens, and of a profound de-politicization" that still characterised the country in the first years of the twenty-first century. He informed the US ambassador to Libya and an early academic researcher that he had not truly wanted to rule over a unified Libya. Muammar Gaddafi's policies with regard to the oil industry would also be technocratic and bore many similarities with those of King Idris. Although the King died in exile and most Libyans were born after his reign, during theLibyan Civil War

Demographics of Libya is the demography of Libya, specifically covering population density, ethnicity, education level, health of the populace, economic status, and religious affiliations, as well as other aspects of the Libyan population. The ...

, many demonstrators opposing Gaddafi carried portraits of the King, especially in Cyrenaica. The tricolour flag used during the era of the monarchy was frequently used as a symbol of the revolution and was re-adopted by the National Transitional Council

The National Transitional Council of Libya ( ar, المجلس الوطني الإنتقالي '), sometimes known as the Transitional National Council, was the ''de facto'' government of Libya for a period during and after the Libyan Civil War ...

as the official flag of Libya

The national flag of Libya was originally introduced in 1951, following the creation of the Kingdom of Libya. It was designed by Omar Faiek Shennib and approved by King Idris Al Senussi who comprised the UN delegation representing the three regi ...

.

Personal life

Vandewalle characterised King Idris as "a scholarly individual whose entire life would be marked by a reluctance to engage in politics". For Vandewalle, Idris was a "well meaning but reluctant ruler", as well as "a pious, deeply religious, and self-effacing man". The Libyan Prime Minister Ben Halim stated his view that "I was sure... that drissincerely wanted reform, but I knew from experience that he became hesitant when he felt that such reform would affect the interests of his entourage. He would gradually pull back until he abandoned the reform plans, moved by the whisperings of his entourage." King Idris married five times: # AtKufra

Kufra () is a basinBertarelli (1929), p. 514. and oasis group in the Kufra District of southeastern Cyrenaica in Libya. At the end of nineteenth century Kufra became the centre and holy place of the Senussi order. It also played a minor role in ...

, 1896/1897, his cousin, Sayyida Aisha binti Sayyid Muhammad as-Sharif al-Sanussi (1873 Jaghbub – 1905 or 1907 Kufra), eldest daughter of Sayyid Muhammad as-Sharif bin Sayyid Muhammad al-Sanussi, by his fourth wife, Fatima, daughter of 'Umar bin Muhammad al-Ashhab, of Fezzan, by whom he had one son who died in infancy;

# At Kufra, 1907 (divorced 1922), his cousin, Sakina, daughter of Muhammad as-Sharif, by whom he had one son and one daughter, both of whom died in infancy;

# At Kufra, 1911 (divorced 1915), Nafisa, daughter of Ahmad Abu al-Qasim al-Isawi, by whom he had one son who died in infancy;

# At Siwa, Egypt, 1931, his cousin, Sayyida Fatima al-Shi'fa binti Sayyid Ahmad as-Sharif al-Sanussi, Fatimah el-Sharif

Sayyida Fatimah el-Sharif ( ar, فاطمة الشريف); after marriage, Fatimah as-Senussi (), 2 April 1911 – 3 October 2009), was queen consort of Libya by marriage to King Idris from 1951 until the 1969 Libyan coup d'état.

Early life

F ...

(1911 Kufra – 3 October 2009, Cairo, buried in Jannat al-Baqi, Medina, Saudi Arabia), fifth daughter of Field Marshal Sayyid Ahmad as-Sharif Pasha

Pasha, Pacha or Paşa ( ota, پاشا; tr, paşa; sq, Pashë; ar, باشا), in older works sometimes anglicized as bashaw, was a higher rank in the Ottoman Empire, Ottoman political and military system, typically granted to governors, gener ...

bin Sayyid Muhammad as-Sharif al-Senussi, 3rd Grand Seussi, by his second wife, Khadija, daughter of Ahmad al-Rifi, by whom he had one son who died in infancy;

# At the Libyan Embassy, Cairo, 6 June 1955 (divorced 20 May 1958), Aliya Khanum Effendi

Effendi or effendy ( tr, efendi ; ota, افندی, efendi; originally from grc-x-medieval, αφέντης ) is a title of nobility meaning ''sir'', ''lord'' or ''master'', especially in the Ottoman Empire and the Caucasus''.'' The title it ...

(1913 Guney, Egypt), daughter of Abdul-Qadir Lamlun Asadi Pasha.

For two short periods (1911–1922 and 1955–1958), King Idris kept two wives, marrying his fifth wife with a view to providing a direct heir.

King Idris fathered five sons and one daughter, none of whom survived childhood. He and Fatima adopted a daughter, Suleima, an Algerian orphan, who survived them.

Honours

Order of Idris I

The Order of Idris I (''Nishan al-Idris'') was founded by ''Sayyid'' Muhammad Idris as-Senussi, Emir of Cyrenaica, in 1947. The Emir later became Idris of Libya, King Idris I in December 1951, when the Kingdom of Libya, United Kingdom of Libya was ...

*

High Order of Sayyid Muhammad ibn Ali al-Senussi

High may refer to:

Science and technology

* Height

* High (atmospheric), a high-pressure area

* High (computability), a quality of a Turing degree, in computability theory

* High (tectonics), in geology an area where relative tectonic uplift to ...

*

Order of Independence

Order of Independence or Independence Order ( vi, Huân chương Độc lập) is a Vietnamese decoration.

Criteria

The Vietnamese government states that the decoration "shall be conferred or posthumously

Posthumous may refer to:

* Posthum ...

* Al-Senussi National Service Star

* Al-Senussi Army Liberation Medal

He was a recipient of the following non-Libyan honours:

*  Imperial Order of the House of Osman 1st class (

Imperial Order of the House of Osman 1st class (Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

) (1918)

*  Nobility (Nishan-i-Majidieh) 2nd class (Ottoman Empire) (1918)

*

Nobility (Nishan-i-Majidieh) 2nd class (Ottoman Empire) (1918)

* Collar

Collar may refer to:

Human neckwear

*Clerical collar (informally ''dog collar''), a distinctive collar used by the clergy of some Christian religious denominations

*Collar (clothing), the part of a garment that fastens around or frames the neck

...

of the Order of al-Hussein bin Ali

The Order of al-Hussein bin Ali is the highest order of the Kingdom of Jordan. It was founded on 22 June 1949 with one class (i.e. Collar) by King Abdullah I of Jordan with the scope of rewarding benevolence and foreign Heads of State. The class ...

(Jordan

Jordan ( ar, الأردن; tr. ' ), officially the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan,; tr. ' is a country in Western Asia. It is situated at the crossroads of Asia, Africa, and Europe, within the Levant region, on the East Bank of the Jordan Rive ...

)

* Order of the British Empire

The Most Excellent Order of the British Empire is a British order of chivalry, rewarding contributions to the arts and sciences, work with charitable and welfare organisations,

and public service outside the civil service. It was established ...

(1954 – KBE in 1946) (United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and North ...

)

* Collar of the Order of Muhammad

The Order of Muhammad, also referred to as Order of Sovereignty ( ar, وسام المحمدي, Wissam al-Mohammadi, French: ''Ordre de la Souveraineté'' or ''Ordre de Mohammed''), is the highest state decoration of the Kingdom of Morocco. The O ...

(Morocco

Morocco (),, ) officially the Kingdom of Morocco, is the westernmost country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It overlooks the Mediterranean Sea to the north and the Atlantic Ocean to the west, and has land borders with Algeria to ...

)

*  Grand Cordon of the

Grand Cordon of the Order of the Nile

The Order of the Nile (''Kiladat El Nil'') was established in 1915 and was one of the Kingdom of Egypt's principal orders until the monarchy was abolished in 1953. It was then reconstituted as the Republic of Egypt's highest state honor.

Sultana ...

(Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediter ...

)

* Legion of Honour

The National Order of the Legion of Honour (french: Ordre national de la Légion d'honneur), formerly the Royal Order of the Legion of Honour ('), is the highest French order of merit, both military and civil. Established in 1802 by Napoleon, ...

(France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

)

*  Grand Cordon of the Order of Independence (

Grand Cordon of the Order of Independence (Tunisia

)

, image_map = Tunisia location (orthographic projection).svg

, map_caption = Location of Tunisia in northern Africa

, image_map2 =

, capital = Tunis

, largest_city = capital

, ...

)

*  Grand Cordon of the

Grand Cordon of the National Order of the Cedar

National may refer to:

Common uses

* Nation or country

** Nationality – a ''national'' is a person who is subject to a nation, regardless of whether the person has full rights as a citizen

Places in the United States

* National, Maryland, ce ...

(Lebanon

Lebanon ( , ar, لُبْنَان, translit=lubnān, ), officially the Republic of Lebanon () or the Lebanese Republic, is a country in Western Asia. It is located between Syria to the north and east and Israel to the south, while Cyprus li ...

)

* Order of Merit of the Italian Republic

The Order of Merit of the Italian Republic ( it, Ordine al Merito della Repubblica Italiana) is the senior Italian order of merit. It was established in 1951 by the second President of the Italian Republic, Luigi Einaudi.

The highest-ranking ...

(Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical re ...

)

*  Grand Cross of the

Grand Cross of the Order of the Redeemer

The Order of the Redeemer ( el, Τάγμα του Σωτήρος, translit=Tágma tou Sotíros), also known as the Order of the Saviour, is an order of merit of Greece. The Order of the Redeemer is the oldest and highest decoration awarded by the ...

(Greece

Greece,, or , romanized: ', officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the southern tip of the Balkans, and is located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Greece shares land borders with ...

)

Ancestry

References

Footnotes

Bibliography

* * * * * *External links

* * , - , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Idris 01 of Libya 1889 births 1983 deaths Heads of state of Libya Leaders ousted by a coup Libyan exiles Libyan Muslims Libyan people of Algerian descent Libyan prisoners sentenced to death People sentenced to death in absentia Prisoners sentenced to death by Libya Senussi dynasty World War II political leaders Honorary Knights Grand Cross of the Order of the British Empire Grand Croix of the Légion d'honneur Knights Grand Cross of the Order of Merit of the Italian Republic Grand Cordons of the National Order of the Cedar Kings of Libya Libyan emigrants to Egypt Libyan politicians convicted of crimes Libyan royalty Muslim monarchs Dethroned monarchs 19th-century Arabs 20th-century Libyan people Rulers of Cyrenaica Hashemite people Burials at Jannat al-Baqī