King Alfred the Great on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Alfred the Great (alt. Ælfred 848/849 – 26 October 899) was King of the West Saxons from 871 to 886, and King of the Anglo-Saxons from 886 until his death in 899. He was the youngest son of King Æthelwulf and his first wife Osburh, who both died when Alfred was young. Three of Alfred's brothers, Æthelbald, Æthelberht and

Alfred's grandfather, Ecgberht, became king of Wessex in 802, and in the view of the historian

Alfred's grandfather, Ecgberht, became king of Wessex in 802, and in the view of the historian

According to Asser, in his childhood Alfred won a beautifully decorated book of English poetry, offered as a prize by his mother to the first of her sons able to memorise it. He must have had it read to him because his mother died when he was about six and he did not learn to read until he was 12. In 853, Alfred is reported by the ''

According to Asser, in his childhood Alfred won a beautifully decorated book of English poetry, offered as a prize by his mother to the first of her sons able to memorise it. He must have had it read to him because his mother died when he was about six and he did not learn to read until he was 12. In 853, Alfred is reported by the ''

Alfred is not mentioned during the short reigns of his older brothers Æthelbald and Æthelberht. The ''Anglo-Saxon Chronicle'' describes the

Alfred is not mentioned during the short reigns of his older brothers Æthelbald and Æthelberht. The ''Anglo-Saxon Chronicle'' describes the

In the seventh week after Easter (4–10 May 878), around Whitsuntide, Alfred rode to Egbert's Stone east of Selwood where he was met by "all the people of Somerset and of

In the seventh week after Easter (4–10 May 878), around Whitsuntide, Alfred rode to Egbert's Stone east of Selwood where he was met by "all the people of Somerset and of

A year later, in 886, Alfred reoccupied the city of London and set out to make it habitable again. Alfred entrusted the city to the care of his son-in-law

A year later, in 886, Alfred reoccupied the city of London and set out to make it habitable again. Alfred entrusted the city to the care of his son-in-law

The Germanic tribes who invaded Britain in the fifth and sixth centuries relied upon the unarmoured infantry supplied by their tribal levy, or

The Germanic tribes who invaded Britain in the fifth and sixth centuries relied upon the unarmoured infantry supplied by their tribal levy, or

The foundation of Alfred's new military defence system was a network of burhs, distributed at tactical points throughout the kingdom. There were thirty-three burhs, about apart, enabling the military to confront attacks anywhere in the kingdom within a day.

Alfred's burhs (of which 22 developed into

The foundation of Alfred's new military defence system was a network of burhs, distributed at tactical points throughout the kingdom. There were thirty-three burhs, about apart, enabling the military to confront attacks anywhere in the kingdom within a day.

Alfred's burhs (of which 22 developed into

In the late 880s or early 890s, Alfred issued a long '' domboc'' or

In the late 880s or early 890s, Alfred issued a long '' domboc'' or

In the 880s, at the same time that he was "cajoling and threatening" his nobles to build and man the burhs, Alfred, perhaps inspired by the example of

In the 880s, at the same time that he was "cajoling and threatening" his nobles to build and man the burhs, Alfred, perhaps inspired by the example of

Alfred's educational ambitions seem to have extended beyond the establishment of a court school. Believing that without Christian wisdom there can be neither prosperity nor success in war, Alfred aimed "to set to learning (as long as they are not useful for some other employment) all the free-born young men now in England who have the means to apply themselves to it". Conscious of the decay of Latin literacy in his realm, Alfred proposed that primary education be taught in

Alfred's educational ambitions seem to have extended beyond the establishment of a court school. Believing that without Christian wisdom there can be neither prosperity nor success in war, Alfred aimed "to set to learning (as long as they are not useful for some other employment) all the free-born young men now in England who have the means to apply themselves to it". Conscious of the decay of Latin literacy in his realm, Alfred proposed that primary education be taught in  The

The

Asser wrote of Alfred in his ''

Asser wrote of Alfred in his ''

In 868, Alfred married Ealhswith, daughter of a Mercian nobleman, Æthelred Mucel,

In 868, Alfred married Ealhswith, daughter of a Mercian nobleman, Æthelred Mucel,

Alfred died on 26 October 899 at the age of 50 or 51. How he died is unknown, but he suffered throughout his life with a painful and unpleasant illness. His biographer Asser gave a detailed description of Alfred's symptoms, and this has allowed modern doctors to provide a possible diagnosis. It is thought that he had either

Alfred died on 26 October 899 at the age of 50 or 51. How he died is unknown, but he suffered throughout his life with a painful and unpleasant illness. His biographer Asser gave a detailed description of Alfred's symptoms, and this has allowed modern doctors to provide a possible diagnosis. It is thought that he had either

Though

Though  *

*

A prominent statue of King Alfred the Great stands in the middle of Pewsey. It was unveiled in June 1913 to commemorate the coronation of King

A prominent statue of King Alfred the Great stands in the middle of Pewsey. It was unveiled in June 1913 to commemorate the coronation of King

The centerpiece of

The centerpiece of

"Alfred the Great", Isidore Konti, 1910

. Sculpture Center. Retrieved 3 October 2017.

Æthelred

Æthelred (; ang, Æþelræd ) or Ethelred () is an Old English personal name (a compound of '' æþele'' and '' ræd'', meaning "noble counsel" or "well-advised") and may refer to:

Anglo-Saxon England

* Æthelred and Æthelberht, legendary pri ...

, reigned in turn before him. Under Alfred's rule, considerable administrative and military reforms were introduced, prompting lasting change in England.

After ascending the throne, Alfred spent several years fighting Viking

Vikings ; non, víkingr is the modern name given to seafaring people originally from Scandinavia (present-day Denmark, Norway and Sweden),

who from the late 8th to the late 11th centuries raided, pirated, traded and se ...

invasions. He won a decisive victory in the Battle of Edington

At the Battle of Edington, an army of the kingdom of Wessex under Alfred the Great defeated the Great Heathen Army led by the Dane Guthrum on a date between 6 and 12 May 878, resulting in the Treaty of Wedmore later the same year. Primary ...

in 878 and made an agreement with the Vikings, dividing England between Anglo-Saxon territory and the Viking-ruled Danelaw

The Danelaw (, also known as the Danelagh; ang, Dena lagu; da, Danelagen) was the part of England in which the laws of the Danes held sway and dominated those of the Anglo-Saxons. The Danelaw contrasts with the West Saxon law and the Mercian ...

, composed of northern England, the north-east Midlands and East Anglia. Alfred also oversaw the conversion of Viking leader Guthrum

Guthrum ( ang, Guðrum, c. 835 – c. 890) was King of East Anglia in the late 9th century. Originally a native of what is now Denmark, he was one of the leaders of the "Great Summer Army" that arrived in Reading during April 871 to join forces ...

to Christianity. He defended his kingdom against the Viking attempt at conquest, becoming the dominant ruler in England. Alfred began styling himself as "King of the Anglo-Saxons" after reoccupying London from the Vikings. Details of his life are described in a work by 9th-century Welsh scholar and bishop Asser.

Alfred had a reputation as a learned and merciful man of a gracious and level-headed nature who encouraged education, proposing that primary education be conducted in English

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

** English national ...

, rather than Latin, and improving the legal system and military structure and his people's quality of life. He was given the epithet "the Great" in the 16th century and is only one of two English monarchs, alongside Cnut the Great

Cnut (; ang, Cnut cyning; non, Knútr inn ríki ; or , no, Knut den mektige, sv, Knut den Store. died 12 November 1035), also known as Cnut the Great and Canute, was King of England from 1016, King of Denmark from 1018, and King of Norw ...

, to be labelled as such.

Family

Alfred was a son of Æthelwulf, king ofWessex

la, Regnum Occidentalium Saxonum

, conventional_long_name = Kingdom of the West Saxons

, common_name = Wessex

, image_map = Southern British Isles 9th century.svg

, map_caption = S ...

, and his wife Osburh. According to his biographer, Asser, writing in 893, "In the year of our Lord's Incarnation 849 Alfred, King of the Anglo-Saxons", was born at the royal estate called Wantage, in the district known as Berkshire

Berkshire ( ; in the 17th century sometimes spelt phonetically as Barkeshire; abbreviated Berks.) is a historic county in South East England. One of the home counties, Berkshire was recognised by Queen Elizabeth II as the Royal County of Ber ...

(which is so called from Berroc Wood, where the box tree grows very abundantly)." This date has been accepted by the editors of Asser's biography, Simon Keynes

Simon Douglas Keynes, ( ; born 23 September 1952) is a British author who is Elrington and Bosworth Professor of Anglo-Saxon emeritus in the Department of Anglo-Saxon, Norse, and Celtic at Cambridge University, and a Fellow of Trinity College ...

and Michael Lapidge Michael Lapidge, FBA (born 8 February 1942) is a scholar in the field of Medieval Latin literature, particularly that composed in Anglo-Saxon England during the period 600–1100 AD; he is an emeritus Fellow of Clare College, Cambridge, a Fellow ...

, and by other historians such as David Dumville

David Norman Dumville (born 5 May 1949) is a British medievalist and Celtic scholar. He attended at Emmanuel College, Cambridge, where he studied Anglo-Saxon, Norse and Celtic; Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München; and received his PhD a ...

and Richard Huscroft. West Saxon genealogical lists state that Alfred was 23 when he became king in April 871, implying that he was born between April 847 and April 848. This dating is adopted in the biography of Alfred by Alfred Smyth, who regards Asser's biography as fraudulent, an allegation which is rejected by other historians. Richard Abels Richard Abels FRHistS (born 1951) is professor emeritus of history at the United States Naval Academy. Abels is a specialist in the military and political institutions of Anglo-Saxon England. He was Elected Fellow of the Royal Historical Society

...

in his biography discusses both sources but does not decide between them and dates Alfred's birth as 847/849, while Patrick Wormald in his ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

The ''Dictionary of National Biography'' (''DNB'') is a standard work of reference on notable figures from British history, published since 1885. The updated ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'' (''ODNB'') was published on 23 September ...

'' article dates it 848/849. Berkshire had been historically disputed between Wessex and the midland kingdom of Mercia

la, Merciorum regnum

, conventional_long_name=Kingdom of Mercia

, common_name=Mercia

, status=Kingdom

, status_text=Independent kingdom (527–879)Client state of Wessex ()

, life_span=527–918

, era=Heptarchy

, event_start=

, date_start=

, y ...

, and as late as 844, a charter showed that it was part of Mercia, but Alfred's birth in the county is evidence that, by the late 840s, control had passed to Wessex.

He was the youngest of six children. His eldest brother, Æthelstan

Æthelstan or Athelstan (; ang, Æðelstān ; on, Aðalsteinn; ; – 27 October 939) was King of the Anglo-Saxons from 924 to 927 and King of the English from 927 to his death in 939. He was the son of King Edward the Elder and his fir ...

, was old enough to be appointed sub-king of Kent in 839, almost 10 years before Alfred was born. He died in the early 850s. Alfred's next three brothers were successively kings of Wessex. Æthelbald (858–60) and Æthelberht (860–65) were also much older than Alfred, but Æthelred

Æthelred (; ang, Æþelræd ) or Ethelred () is an Old English personal name (a compound of '' æþele'' and '' ræd'', meaning "noble counsel" or "well-advised") and may refer to:

Anglo-Saxon England

* Æthelred and Æthelberht, legendary pri ...

(865–71) was only a year or two older. Alfred's only known sister, Æthelswith, married Burgred

Burgred (also Burhred or Burghred) was an Anglo-Saxon king of Mercia from 852 to 874.

Family

Burgred became king of Mercia in 852, and may have been related to his predecessor Beorhtwulf. After Easter in 853, Burgred married Æthelswith, daughte ...

, king of Mercia in 853. Most historians think that Osburh was the mother of all Æthelwulf's children, but some suggest that the older ones were born to an unrecorded first wife. Osburh was descended from the rulers of the Isle of Wight

The Isle of Wight ( ) is a county in the English Channel, off the coast of Hampshire, from which it is separated by the Solent. It is the largest and second-most populous island of England. Referred to as 'The Island' by residents, the Is ...

. She was described by Alfred's biographer Asser as "a most religious woman, noble by temperament and noble by birth". She had died by 856 when Æthelwulf married Judith, daughter of Charles the Bald

Charles the Bald (french: Charles le Chauve; 13 June 823 – 6 October 877), also known as Charles II, was a 9th-century king of West Francia (843–877), king of Italy (875–877) and emperor of the Carolingian Empire (875–877). After a se ...

, king of West Francia

In medieval history, West Francia (Medieval Latin: ) or the Kingdom of the West Franks () refers to the western part of the Frankish Empire established by Charlemagne. It represents the earliest stage of the Kingdom of France, lasting from ab ...

.

In 868, Alfred married Ealhswith, daughter of the Mercian nobleman Æthelred Mucel, ealdorman

Ealdorman (, ) was a term in Anglo-Saxon England which originally applied to a man of high status, including some of royal birth, whose authority was independent of the king. It evolved in meaning and in the eighth century was sometimes applied ...

of the Gaini, and his wife Eadburh, who was of royal Mercian descent. Their children were Æthelflæd, who married Æthelred, Lord of the Mercians; Edward the Elder

Edward the Elder (17 July 924) was King of the Anglo-Saxons from 899 until his death in 924. He was the elder son of Alfred the Great and his wife Ealhswith. When Edward succeeded to the throne, he had to defeat a challenge from his cousin ...

, Alfred's successor as king; Æthelgifu, abbess of Shaftesbury; Ælfthryth, who married Baldwin, count of Flanders

Flanders (, ; Dutch: ''Vlaanderen'' ) is the Flemish-speaking northern portion of Belgium and one of the communities, regions and language areas of Belgium. However, there are several overlapping definitions, including ones related to cultu ...

; and Æthelweard.

Background

Alfred's grandfather, Ecgberht, became king of Wessex in 802, and in the view of the historian

Alfred's grandfather, Ecgberht, became king of Wessex in 802, and in the view of the historian Richard Abels Richard Abels FRHistS (born 1951) is professor emeritus of history at the United States Naval Academy. Abels is a specialist in the military and political institutions of Anglo-Saxon England. He was Elected Fellow of the Royal Historical Society

...

, it must have seemed very unlikely to contemporaries that he would establish a lasting dynasty. For 200 years, three families had fought for the West Saxon throne, and no son had followed his father as king. No ancestor of Ecgberht had been a king of Wessex since Ceawlin in the late sixth century, but he was believed to be a paternal descendant of Cerdic, the founder of the West Saxon dynasty. This made Ecgberht an ætheling

Ætheling (; also spelt aetheling, atheling or etheling) was an Old English term (''æþeling'') used in Anglo-Saxon England to designate princes of the royal dynasty who were eligible for the kingship.

The term is an Old English and Old Saxon ...

– a prince eligible for the throne. But after Ecgberht's reign, descent from Cerdic was no longer sufficient to make a man an ætheling. When Ecgberht died in 839, he was succeeded by his son Æthelwulf; all subsequent West Saxon kings were descendants of Ecgberht and Æthelwulf, and were also sons of kings.

At the beginning of the ninth century, England was almost wholly under the control of the Anglo-Saxon

The Anglo-Saxons were a cultural group who inhabited England in the Early Middle Ages. They traced their origins to settlers who came to Britain from mainland Europe in the 5th century. However, the ethnogenesis of the Anglo-Saxons happened wit ...

s. Mercia dominated southern England, but its supremacy came to an end in 825 when it was decisively defeated by Ecgberht at the Battle of Ellendun. The two kingdoms became allies, which was important in the resistance to Viking

Vikings ; non, víkingr is the modern name given to seafaring people originally from Scandinavia (present-day Denmark, Norway and Sweden),

who from the late 8th to the late 11th centuries raided, pirated, traded and se ...

attacks. In 853, King Burgred of Mercia requested West Saxon help to suppress a Welsh rebellion, and Æthelwulf led a West Saxon contingent in a successful joint campaign. In the same year Burgred married Æthelwulf's daughter, Æthelswith.

In 825, Ecgberht sent Æthelwulf to invade the Mercian sub-kingdom of Kent

Kent is a county in South East England and one of the home counties. It borders Greater London to the north-west, Surrey to the west and East Sussex to the south-west, and Essex to the north across the estuary of the River Thames; it faces ...

, and its sub-king, Baldred, was driven out shortly afterwards. By 830, Essex

Essex () is a Ceremonial counties of England, county in the East of England. One of the home counties, it borders Suffolk and Cambridgeshire to the north, the North Sea to the east, Hertfordshire to the west, Kent across the estuary of the Riv ...

, Surrey

Surrey () is a ceremonial county, ceremonial and non-metropolitan county, non-metropolitan counties of England, county in South East England, bordering Greater London to the south west. Surrey has a large rural area, and several significant ur ...

and Sussex

Sussex (), from the Old English (), is a historic county in South East England that was formerly an independent medieval Anglo-Saxon kingdom. It is bounded to the west by Hampshire, north by Surrey, northeast by Kent, south by the Englis ...

had submitted to Ecgberht, and he had appointed Æthelwulf to rule the south-eastern territories as king of Kent. The Vikings ravaged the Isle of Sheppey

The Isle of Sheppey is an island off the northern coast of Kent, England, neighbouring the Thames Estuary, centred from central London. It has an area of . The island forms part of the local government district of Swale. ''Sheppey'' is deriv ...

in 835, and the following year they defeated Ecgberht at Carhampton

Carhampton is a village and civil parish in Somerset, England, to the east of Minehead.

Carhampton civil parish stretches from the Bristol Channel coast inland to Exmoor. The parish has a population of 865 (2011 census).

History

Iron Age occup ...

in Somerset

( en, All The People of Somerset)

, locator_map =

, coordinates =

, region = South West England

, established_date = Ancient

, established_by =

, preceded_by =

, origin =

, lord_lieutenant_office =Lord Lieutenant of Somerset

, lor ...

, but in 838 he was victorious over an alliance of Cornishmen and Vikings at the Battle of Hingston Down

The Battle of Hingston Down took place in 838, probably at Hingston Down in Cornwall between a combined force of Cornish and Vikings on the one side, and West Saxons led by Ecgberht, King of Wessex on the other. The result was a West Saxon ...

, reducing Cornwall to the status of a client kingdom. When Æthelwulf succeeded, he appointed his eldest son Æthelstan as sub-king of Kent. Ecgberht and Æthelwulf may not have intended a permanent union between Wessex and Kent because they both appointed sons as sub-kings, and charters in Wessex were attested (witnessed) by West Saxon magnates, while Kentish charters were witnessed by the Kentish elite; both kings kept overall control, and the sub-kings were not allowed to issue their own coinage.

Viking raids increased in the early 840s on both sides of the English Channel, and in 843 Æthelwulf was defeated at Carhampton. In 850, Æthelstan defeated a Danish fleet off Sandwich

A sandwich is a food typically consisting of vegetables, sliced cheese or meat, placed on or between slices of bread, or more generally any dish wherein bread serves as a container or wrapper for another food type. The sandwich began as a po ...

in the first recorded naval battle in English history. In 851 Æthelwulf and his second son, Æthelbald, defeated the Vikings at the Battle of Aclea

The Battle of Aclea occurred in 851 between the West Saxons led by Æthelwulf, King of Wessex and the Danish Vikings at an unknown location in Surrey. It resulted in a West Saxon victory.

Little is known about the battle and the most importa ...

and, according to the ''Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

The ''Anglo-Saxon Chronicle'' is a collection of annals in Old English, chronicling the history of the Anglo-Saxons. The original manuscript of the ''Chronicle'' was created late in the 9th century, probably in Wessex, during the reign of A ...

'', "there made the greatest slaughter of a heathen raiding-army that we have heard tell of up to this present day, and there took the victory". Æthelwulf died in 858 and was succeeded by his oldest surviving son, Æthelbald, as king of Wessex and by his next oldest son, Æthelberht, as king of Kent. Æthelbald only survived his father by two years, and Æthelberht then for the first time united Wessex and Kent into a single kingdom.

Childhood

According to Asser, in his childhood Alfred won a beautifully decorated book of English poetry, offered as a prize by his mother to the first of her sons able to memorise it. He must have had it read to him because his mother died when he was about six and he did not learn to read until he was 12. In 853, Alfred is reported by the ''

According to Asser, in his childhood Alfred won a beautifully decorated book of English poetry, offered as a prize by his mother to the first of her sons able to memorise it. He must have had it read to him because his mother died when he was about six and he did not learn to read until he was 12. In 853, Alfred is reported by the ''Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

The ''Anglo-Saxon Chronicle'' is a collection of annals in Old English, chronicling the history of the Anglo-Saxons. The original manuscript of the ''Chronicle'' was created late in the 9th century, probably in Wessex, during the reign of A ...

'' to have been sent to Rome where he was confirmed by Pope Leo IV

Pope Leo IV (790 – 17 July 855) was the bishop of Rome and ruler of the Papal States from 10 April 847 to his death. He is remembered for repairing Roman churches that had been damaged during the Arab raid against Rome, and for building the Leo ...

, who "anointed him as king". Victorian writers later interpreted this as an anticipatory coronation in preparation for his eventual succession to the throne of Wessex. This is unlikely; his succession could not have been foreseen at the time because Alfred had three living elder brothers. A letter of Leo IV shows that Alfred was made a "consul

Consul (abbrev. ''cos.''; Latin plural ''consules'') was the title of one of the two chief magistrates of the Roman Republic, and subsequently also an important title under the Roman Empire. The title was used in other European city-states throu ...

" and a misinterpretation of this investiture, deliberate or accidental, could explain later confusion. It may be based upon the fact that Alfred later accompanied his father on a pilgrimage to Rome where he spent some time at the court of Charles the Bald

Charles the Bald (french: Charles le Chauve; 13 June 823 – 6 October 877), also known as Charles II, was a 9th-century king of West Francia (843–877), king of Italy (875–877) and emperor of the Carolingian Empire (875–877). After a se ...

, king of the Franks

The Franks, Germanic-speaking peoples that invaded the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century, were first led by individuals called dukes and reguli. The earliest group of Franks that rose to prominence was the Salian Merovingians, who c ...

, around 854–855. On their return from Rome in 856, Æthelwulf was deposed by his son Æthelbald. With civil war looming, the magnates of the realm met in council to form a compromise. Æthelbald retained the western shires (i.e. historical Wessex), and Æthelwulf ruled in the east. After King Æthelwulf died in 858, Wessex was ruled by three of Alfred's brothers in succession: Æthelbald, Æthelberht and Æthelred

Æthelred (; ang, Æþelræd ) or Ethelred () is an Old English personal name (a compound of '' æþele'' and '' ræd'', meaning "noble counsel" or "well-advised") and may refer to:

Anglo-Saxon England

* Æthelred and Æthelberht, legendary pri ...

.

The reigns of Alfred's brothers

Great Heathen Army

The Great Heathen Army,; da, Store Hedenske Hær also known as the Viking Great Army,Hadley. "The Winter Camp of the Viking Great Army, AD 872–3, Torksey, Lincolnshire", ''Antiquaries Journal''. 96, pp. 23–67 was a coalition of Scandin ...

of Danes landing in East Anglia with the intent of conquering the four kingdoms which constituted Anglo-Saxon England in 865. Alfred's public life began in 865 at age 16 with the accession of his third brother, 18-year-old Æthelred. During this period, Bishop Asser gave Alfred the unique title of ''secundarius'', which may indicate a position similar to the Celtic tanist, a recognised successor closely associated with the reigning monarch. This arrangement may have been sanctioned by Alfred's father or by the Witan to guard against the danger of a disputed succession should Æthelred fall in battle. It was a well known tradition among other Germanic peoples – such as the Swedes and Franks to whom the Anglo-Saxons were closely related – to crown a successor as royal prince and military commander.

Viking invasion

In 868, Alfred was recorded as fighting beside Æthelred in a failed attempt to keep the Great Heathen Army led by Ivar the Boneless out of the adjoining Kingdom of Mercia. The Danes arrived in his homeland at the end of 870, and nine engagements were fought in the following year, with mixed results; the places and dates of two of these battles have not been recorded. A successful skirmish at the Battle of Englefield in Berkshire on 31 December 870 was followed by a severe defeat at the siege and the Battle of Reading by Ivar's brother Halfdan Ragnarsson on 5 January 871. Four days later, the Anglo-Saxons won a victory at the Battle of Ashdown on the Berkshire Downs, possibly near Compton or Aldworth. The Saxons were defeated at theBattle of Basing

The Battle of Basing was a victory of a Danish Viking army over the West Saxons at the royal estate of Basing in Hampshire on about 22 January 871.

In late December 870 the Vikings invaded Wessex and occupied Reading. Several battles followe ...

on 22 January. They were defeated again on 22 March at the Battle of Merton (perhaps Marden in Wiltshire or Martin in Dorset). Æthelred died shortly afterwards in April.

King at war

Early struggles

In April 871 King Æthelred died and Alfred acceded to the throne of Wessex and the burden of its defence, even though Æthelred left two under-age sons, Æthelhelm and Æthelwold. This was in accordance with the agreement that Æthelred and Alfred had made earlier that year in an assembly at an unidentified place called Swinbeorg. The brothers had agreed that whichever of them outlived the other would inherit the personal property that King Æthelwulf had left jointly to his sons in his will. The deceased's sons would receive only whatever property and riches their father had settled upon them and whatever additional lands their uncle had acquired. The unstated premise was that the surviving brother would be king. Given the Danish invasion and the youth of his nephews, Alfred's accession probably went uncontested. While he was busy with the burial ceremonies for his brother, the Danes defeated the Saxon army in his absence at an unnamed spot and then again in his presence at Wilton in May. The defeat at Wilton smashed any remaining hope that Alfred could drive the invaders from his kingdom. Alfred was forced instead to make peace with them. Although the terms of the peace are not recorded, Bishop Asser wrote that the pagans agreed to vacate the realm and made good their promise. The Viking army withdrew from Reading in the autumn of 871 to take up winter quarters in Mercian London. Although not mentioned by Asser or by the ''Anglo-Saxon Chronicle'', Alfred probably paid the Vikings cash to leave, much as the Mercians were to do in the following year.Hoard

A hoard or "wealth deposit" is an archaeological term for a collection of valuable objects or artifacts, sometimes purposely buried in the ground, in which case it is sometimes also known as a cache. This would usually be with the intention of ...

s dating to the Viking occupation of London in 871/872 have been excavated at Croydon

Croydon is a large town in south London, England, south of Charing Cross. Part of the London Borough of Croydon, a local government district of Greater London. It is one of the largest commercial districts in Greater London, with an exten ...

, Gravesend

Gravesend is a town in northwest Kent, England, situated 21 miles (35 km) east-southeast of Charing Cross (central London) on the south bank of the River Thames and opposite Tilbury in Essex. Located in the diocese of Rochester, it is ...

and Waterloo Bridge. These finds hint at the cost involved in making peace with the Vikings. For the next five years, the Danes occupied other parts of England.

In 876, under their three leaders Guthrum

Guthrum ( ang, Guðrum, c. 835 – c. 890) was King of East Anglia in the late 9th century. Originally a native of what is now Denmark, he was one of the leaders of the "Great Summer Army" that arrived in Reading during April 871 to join forces ...

, Oscetel and Anwend, the Danes slipped past the Saxon army and attacked and occupied Wareham in Dorset. Alfred blockaded them but was unable to take Wareham by assault. He negotiated a peace that involved an exchange of hostages and oaths, which the Danes swore on a "holy ring" associated with the worship of Thor

Thor (; from non, Þórr ) is a prominent god in Germanic paganism. In Norse mythology, he is a hammer-wielding god associated with lightning, thunder, storms, sacred groves and trees, strength, the protection of humankind, hallowing, ...

. The Danes broke their word, and after killing all the hostages, slipped away under cover of night to Exeter

Exeter () is a city in Devon, South West England. It is situated on the River Exe, approximately northeast of Plymouth and southwest of Bristol.

In Roman Britain, Exeter was established as the base of Legio II Augusta under the personal comm ...

in Devon.

Alfred blockaded the Viking ships in Devon, and with a relief fleet having been scattered by a storm, the Danes were forced to submit. The Danes withdrew to Mercia. In January 878, the Danes made a sudden attack on Chippenham

Chippenham is a market town in northwest Wiltshire, England. It lies northeast of Bath, west of London, and is near the Cotswolds Area of Natural Beauty. The town was established on a crossing of the River Avon and some form of settlement i ...

, a royal stronghold in which Alfred had been staying over Christmas "and most of the people they killed, except the King Alfred, and he with a little band made his way by wood and swamp, and after Easter he made a fort at Athelney in the marshes of Somerset

( en, All The People of Somerset)

, locator_map =

, coordinates =

, region = South West England

, established_date = Ancient

, established_by =

, preceded_by =

, origin =

, lord_lieutenant_office =Lord Lieutenant of Somerset

, lor ...

, and from that fort kept fighting against the foe". From his fort at Athelney, an island in the marshes near North Petherton

North Petherton is a small town and civil parish in Somerset, England, situated on the edge of the eastern foothills of the Quantocks, and close to the edge of the Somerset Levels.

The town has a population of 6,730 as of 2014. The parish incl ...

, Alfred was able to mount a resistance campaign, rallying the local militias from Somerset, Wiltshire

Wiltshire (; abbreviated Wilts) is a historic and ceremonial county in South West England with an area of . It is landlocked and borders the counties of Dorset to the southwest, Somerset to the west, Hampshire to the southeast, Gloucestershire ...

and Hampshire

Hampshire (, ; abbreviated to Hants) is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in western South East England on the coast of the English Channel. Home to two major English cities on its south coast, Southampton and Portsmouth, Hampshire ...

. 878 was the nadir of the history of the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms. With all the other kingdoms having fallen to the Vikings, Wessex alone was resisting.

The cake legend

A legend tells how when Alfred first fled to theSomerset Levels

The Somerset Levels are a coastal plain and wetland area of Somerset, England, running south from the Mendips to the Blackdown Hills.

The Somerset Levels have an area of about and are bisected by the Polden Hills; the areas to the south a ...

, he was given shelter by a peasant woman who, unaware of his identity, left him to watch some wheaten cakes she had left cooking on the fire. Preoccupied with the problems of his kingdom, Alfred accidentally let the cakes burn and was roundly scolded by the woman upon her return. There is no contemporary evidence for the legend, but it is possible that there was an early oral tradition. The first known written account of the incident is from about 100 years after Alfred's death.

Counter-attack and victory

In the seventh week after Easter (4–10 May 878), around Whitsuntide, Alfred rode to Egbert's Stone east of Selwood where he was met by "all the people of Somerset and of

In the seventh week after Easter (4–10 May 878), around Whitsuntide, Alfred rode to Egbert's Stone east of Selwood where he was met by "all the people of Somerset and of Wiltshire

Wiltshire (; abbreviated Wilts) is a historic and ceremonial county in South West England with an area of . It is landlocked and borders the counties of Dorset to the southwest, Somerset to the west, Hampshire to the southeast, Gloucestershire ...

and of that part of Hampshire

Hampshire (, ; abbreviated to Hants) is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in western South East England on the coast of the English Channel. Home to two major English cities on its south coast, Southampton and Portsmouth, Hampshire ...

which is on this side of the sea (that is, west of Southampton Water), and they rejoiced to see him". Alfred's emergence from his marshland stronghold was part of a carefully planned offensive that entailed raising the fyrd

A fyrd () was a type of early Anglo-Saxon army that was mobilised from freemen or paid men to defend their Shire's lords estate, or from selected representatives to join a royal expedition. Service in the fyrd was usually of short duration and ...

s of three shire

Shire is a traditional term for an administrative division of land in Great Britain and some other English-speaking countries such as Australia and New Zealand. It is generally synonymous with county. It was first used in Wessex from the begin ...

s. This meant not only that the king had retained the loyalty of ealdormen

Ealdorman (, ) was a term in Anglo-Saxon England which originally applied to a man of high status, including some of royal birth, whose authority was independent of the king. It evolved in meaning and in the eighth century was sometimes applied ...

, royal reeves and king's thegns, who were charged with levying and leading these forces, but that they had maintained their positions of authority in these localities well enough to answer his summons to war. Alfred's actions also suggest a system of scouts and messengers.

Alfred won a decisive victory in the ensuing Battle of Edington

At the Battle of Edington, an army of the kingdom of Wessex under Alfred the Great defeated the Great Heathen Army led by the Dane Guthrum on a date between 6 and 12 May 878, resulting in the Treaty of Wedmore later the same year. Primary ...

which may have been fought near Westbury, Wiltshire

Westbury is a town and civil parish in the west of the English county of Wiltshire, below the northwestern edge of Salisbury Plain, about south of Trowbridge and a similar distance north of Warminster. Originally a market town, Westbury was ...

. He then pursued the Danes to their stronghold at Chippenham

Chippenham is a market town in northwest Wiltshire, England. It lies northeast of Bath, west of London, and is near the Cotswolds Area of Natural Beauty. The town was established on a crossing of the River Avon and some form of settlement i ...

and starved them into submission. One of the terms of the surrender was that Guthrum convert to Christianity. Three weeks later, the Danish king and 29 of his chief men were baptised at Alfred's court at Aller, near Athelney, with Alfred receiving Guthrum as his spiritual son.

According to Asser,

At Wedmore, Alfred and Guthrum negotiated what some historians have called the Treaty of Wedmore

The Treaty of Wedmore is a 9th-century accord between Alfred the Great of Wessex and the Viking king Guthrum the Old. The only contemporary reference to this treaty, is that of a Welsh monk Asser in his biography of Alfred, (known as ''Vita Ælf ...

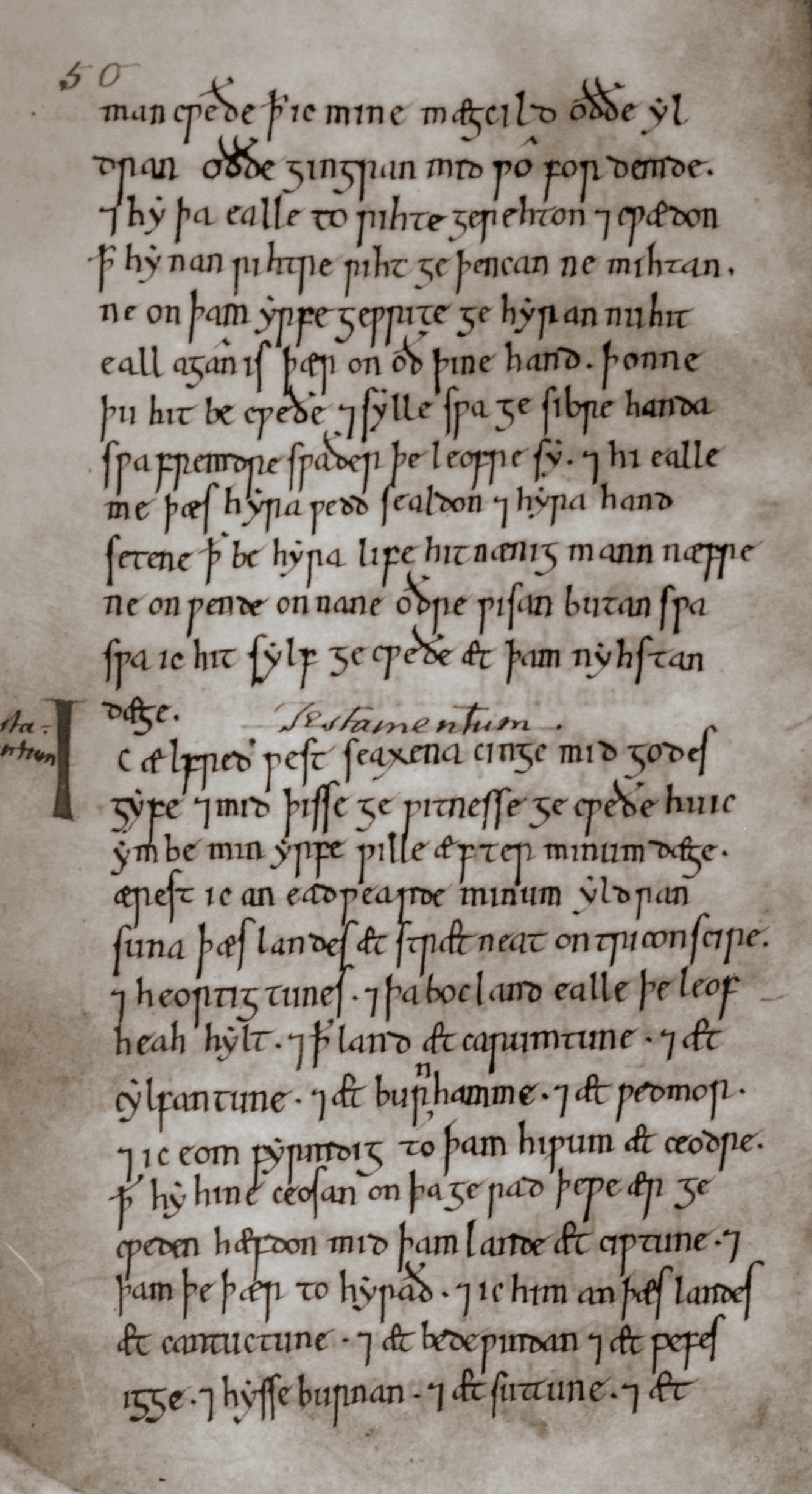

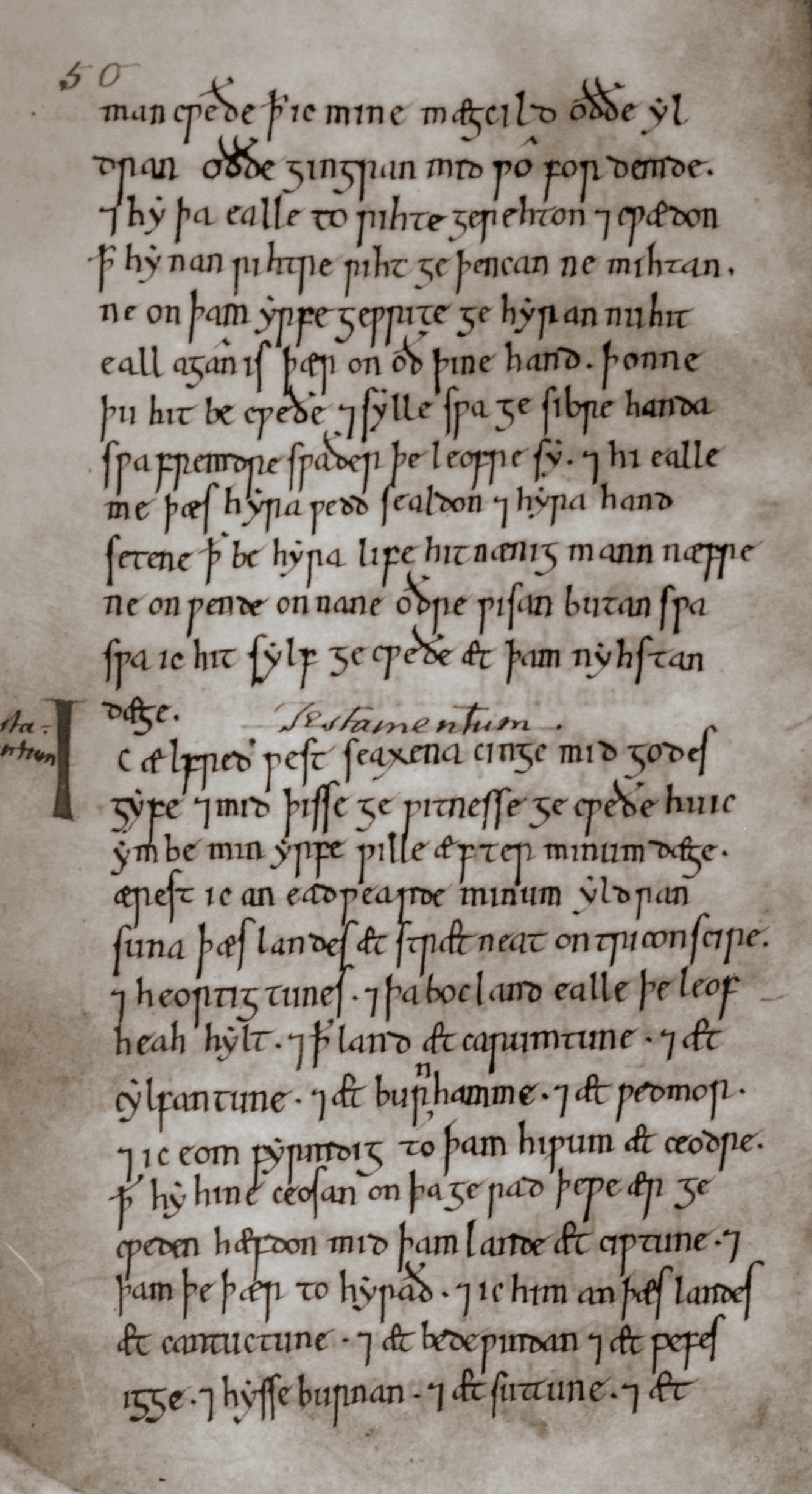

, but it was to be some years after the cessation of hostilities that a formal treaty was signed. Under the terms of the so-called Treaty of Wedmore, the converted Guthrum was required to leave Wessex and return to East Anglia. Consequently, in 879 the Viking army left Chippenham and made its way to Cirencester. The formal Treaty of Alfred and Guthrum

The Treaty of Alfred and Guthrum is a 9th-century peace agreement between Alfred of Wessex and Guthrum, the Viking ruler of East Anglia. It sets out the boundaries between Alfred and Guthrum's territories as well as agreements on peaceful trade, ...

, preserved in Old English

Old English (, ), or Anglo-Saxon, is the earliest recorded form of the English language, spoken in England and southern and eastern Scotland in the early Middle Ages. It was brought to Great Britain by Anglo-Saxon settlers in the mid-5th ...

in Corpus Christi College, Cambridge

Corpus Christi College (full name: "The College of Corpus Christi and the Blessed Virgin Mary", often shortened to "Corpus"), is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge. From the late 14th century through to the early 19th centur ...

(Manuscript 383), and in a Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through ...

compilation known as '' Quadripartitus'', was negotiated later, perhaps in 879 or 880, when King Ceolwulf II of Mercia was deposed.

That treaty divided up the kingdom of Mercia. By its terms, the boundary between Alfred's and Guthrum's kingdoms was to run up the River Thames

The River Thames ( ), known alternatively in parts as the The Isis, River Isis, is a river that flows through southern England including London. At , it is the longest river entirely in England and the Longest rivers of the United Kingdom, se ...

to the River Lea

The River Lea ( ) is in South East England. It originates in Bedfordshire, in the Chiltern Hills, and flows southeast through Hertfordshire, along the Essex border and into Greater London, to meet the River Thames at Bow Creek. It is one of ...

, follow the Lea to its source (near Luton

Luton () is a town and unitary authority with borough status, in Bedfordshire, England. At the 2011 census, the Luton built-up area subdivision had a population of 211,228 and its built-up area, including the adjacent towns of Dunstable an ...

), from there extend in a straight line to Bedford

Bedford is a market town in Bedfordshire, England. At the 2011 Census, the population of the Bedford built-up area (including Biddenham and Kempston) was 106,940, making it the second-largest settlement in Bedfordshire, behind Luton, whilst t ...

, and from Bedford follow the River Ouse to Watling Street

Watling Street is a historic route in England that crosses the River Thames at London and which was used in Classical Antiquity, Late Antiquity, and throughout the Middle Ages. It was used by the ancient Britons and paved as one of the main ...

.

Alfred succeeded to Ceolwulf's kingdom consisting of western Mercia, and Guthrum incorporated the eastern part of Mercia into an enlarged Kingdom of East Anglia (henceforward known as the Danelaw

The Danelaw (, also known as the Danelagh; ang, Dena lagu; da, Danelagen) was the part of England in which the laws of the Danes held sway and dominated those of the Anglo-Saxons. The Danelaw contrasts with the West Saxon law and the Mercian ...

). By terms of the treaty, moreover, Alfred was to have control over the Mercian city of London and its mints—at least for the time being. In 825, the ''Anglo-Saxon Chronicle'' had recorded that the people of Essex, Sussex, Kent and Surrey surrendered to Egbert, Alfred's grandfather. From then until the arrival of the Great Heathen Army

The Great Heathen Army,; da, Store Hedenske Hær also known as the Viking Great Army,Hadley. "The Winter Camp of the Viking Great Army, AD 872–3, Torksey, Lincolnshire", ''Antiquaries Journal''. 96, pp. 23–67 was a coalition of Scandin ...

, Essex had formed part of Wessex. After the foundation of Danelaw, it appears that some of Essex would have been ceded to the Danes, but how much is not clear.

880s

With the signing of theTreaty of Alfred and Guthrum

The Treaty of Alfred and Guthrum is a 9th-century peace agreement between Alfred of Wessex and Guthrum, the Viking ruler of East Anglia. It sets out the boundaries between Alfred and Guthrum's territories as well as agreements on peaceful trade, ...

, an event most commonly held to have taken place around 880 when Guthrum's people began settling East Anglia

East Anglia is an area in the East of England, often defined as including the counties of Norfolk, Suffolk and Cambridgeshire. The name derives from the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of the East Angles, a people whose name originated in Anglia, in ...

, Guthrum was neutralised as a threat. The Viking army, which had stayed at Fulham during the winter of 878–879, sailed for Ghent and was active on the continent from 879 to 892.

There were local raids on the coast of Wessex throughout the 880s. In 882, Alfred fought a small sea battle against four Danish ships. Two of the ships were destroyed, and the others surrendered. This was one of four sea battles recorded in the ''Anglo-Saxon Chronicle'', three of which involved Alfred. Similar small skirmishes with independent Viking raiders would have occurred for much of the period as they had for decades.

In 883, Pope Marinus exempted the Saxon quarter in Rome from taxation, probably in return for Alfred's promise to send alms annually to Rome, which may be the origin of the medieval tax called Peter's Pence

Peter's Pence (or ''Denarii Sancti Petri'' and "Alms of St Peter") are donations or payments made directly to the Holy See of the Catholic Church. The practice began under the Saxons in England and spread through Europe. Both before and after the ...

. The pope sent gifts to Alfred, including what was reputed to be a piece of the True Cross

The True Cross is the cross upon which Jesus was said to have been crucified, particularly as an object of religious veneration. There are no early accounts that the apostles or early Christians preserved the physical cross themselves, althoug ...

.

After the signing of the treaty with Guthrum, Alfred was spared any large-scale conflicts for some time. Despite this relative peace, the king was forced to deal with a number of Danish raids and incursions. Among these was a raid in Kent

Kent is a county in South East England and one of the home counties. It borders Greater London to the north-west, Surrey to the west and East Sussex to the south-west, and Essex to the north across the estuary of the River Thames; it faces ...

, an allied kingdom in South East England, during the year 885, which was possibly the largest raid since the battles with Guthrum. Asser's account of the raid places the Danish raiders at the Saxon city of Rochester, where they built a temporary fortress in order to besiege the city. In response to this incursion, Alfred led an Anglo-Saxon

The Anglo-Saxons were a cultural group who inhabited England in the Early Middle Ages. They traced their origins to settlers who came to Britain from mainland Europe in the 5th century. However, the ethnogenesis of the Anglo-Saxons happened wit ...

force against the Danes who, instead of engaging the army of Wessex, fled to their beached ships and sailed to another part of Britain. The retreating Danish force supposedly left Britain the following summer.

Not long after the failed Danish raid in Kent, Alfred dispatched his fleet to East Anglia. The purpose of this expedition is debated, but Asser claims that it was for the sake of plunder. After travelling up the River Stour, the fleet was met by Danish vessels that numbered 13 or 16 (sources vary on the number), and a battle ensued. The Anglo-Saxon fleet emerged victorious, and as Henry of Huntingdon writes, "laden with spoils". The victorious fleet was surprised when attempting to leave the River Stour and was attacked by a Danish force at the mouth of the river. The Danish fleet defeated Alfred's fleet, which may have been weakened in the previous engagement.

King of the Anglo-Saxons

Æthelred

Æthelred (; ang, Æþelræd ) or Ethelred () is an Old English personal name (a compound of '' æþele'' and '' ræd'', meaning "noble counsel" or "well-advised") and may refer to:

Anglo-Saxon England

* Æthelred and Æthelberht, legendary pri ...

, ealdorman

Ealdorman (, ) was a term in Anglo-Saxon England which originally applied to a man of high status, including some of royal birth, whose authority was independent of the king. It evolved in meaning and in the eighth century was sometimes applied ...

of Mercia. Soon afterwards, Alfred restyled himself as "King of the Anglo-Saxons". The restoration of London progressed through the latter half of the 880s and is believed to have revolved around a new street plan; added fortifications in addition to the existing Roman walls; and, some believe, the construction of matching fortifications on the south bank of the River Thames

The River Thames ( ), known alternatively in parts as the The Isis, River Isis, is a river that flows through southern England including London. At , it is the longest river entirely in England and the Longest rivers of the United Kingdom, se ...

.

This is also the period in which almost all chroniclers agree that the Saxon people of pre-unification England submitted to Alfred. In 888, Æthelred, the archbishop of Canterbury

The archbishop of Canterbury is the senior bishop and a principal leader of the Church of England, the ceremonial head of the worldwide Anglican Communion and the diocesan bishop of the Diocese of Canterbury. The current archbishop is Just ...

, also died. One year later Guthrum, or Athelstan by his baptismal name, Alfred's former enemy and king of East Anglia, died and was buried in Hadleigh, Suffolk

Hadleigh () is an ancient market town and civil parish in South Suffolk, East Anglia, situated, next to the River Brett, between the larger towns of Sudbury and Ipswich. It had a population of 8,253 at the 2011 census. The headquarters of Ba ...

. Guthrum's death changed the political landscape for Alfred. The resulting power vacuum stirred other power-hungry warlords eager to take his place in the following years. The quiet years of Alfred's life were coming to a close.

Viking attacks (890s)

After another lull, in the autumn of 892 or 893, the Danes attacked again. Finding their position in mainland Europe precarious, they crossed to England in 330 ships in two divisions. They entrenched themselves, the larger body at Appledore, Kent, and the lesser under Hastein, at Milton, also in Kent. The invaders brought their wives and children with them, indicating a meaningful attempt at conquest and colonisation. Alfred, in 893 or 894, took up a position from which he could observe both forces. While he was in talks with Hastein, the Danes at Appledore broke out and struck north-westwards. They were overtaken by Alfred's eldest son,Edward

Edward is an English given name. It is derived from the Anglo-Saxon name ''Ēadweard'', composed of the elements '' ēad'' "wealth, fortune; prosperous" and '' weard'' "guardian, protector”.

History

The name Edward was very popular in Anglo-Sax ...

and were defeated at the Battle of Farnham

The Battle of Farnham was an armed conflict between the Anglo-Saxons, under the command of Alfred the Great and Edward the Elder

Edward the Elder (17 July 924) was King of the Anglo-Saxons from 899 until his death in 924. He was the elder ...

in Surrey. They took refuge on an island at Thorney, on the River Colne between Buckinghamshire

Buckinghamshire (), abbreviated Bucks, is a ceremonial county in South East England that borders Greater London to the south-east, Berkshire to the south, Oxfordshire to the west, Northamptonshire to the north, Bedfordshire to the north-e ...

and Middlesex

Middlesex (; abbreviation: Middx) is a historic county in southeast England. Its area is almost entirely within the wider urbanised area of London and mostly within the ceremonial county of Greater London, with small sections in neighbour ...

, where they were blockaded and forced to give hostages and promise to leave Wessex. They then went to Essex and after suffering another defeat at Benfleet, joined with Hastein's force at Shoebury.

Alfred had been on his way to relieve his son at Thorney when he heard that the Northumbria

la, Regnum Northanhymbrorum

, conventional_long_name = Kingdom of Northumbria

, common_name = Northumbria

, status = State

, status_text = Unified Anglian kingdom (before 876)North: Anglian kingdom (af ...

n and East Anglian Danes were besieging Exeter

Exeter () is a city in Devon, South West England. It is situated on the River Exe, approximately northeast of Plymouth and southwest of Bristol.

In Roman Britain, Exeter was established as the base of Legio II Augusta under the personal comm ...

and an unnamed stronghold on the North Devon

North Devon is a local government district in Devon, England. North Devon Council is based in Barnstaple. Other towns and villages in the North Devon District include Braunton, Fremington, Ilfracombe, Instow, South Molton, Lynton and Lyn ...

shore. Alfred at once hurried westward and raised the Siege of Exeter. The fate of the other place is not recorded.

The force under Hastein set out to march up the Thames Valley, possibly with the idea of assisting their friends in the west. They were met by a large force under the three great ealdormen of Mercia

la, Merciorum regnum

, conventional_long_name=Kingdom of Mercia

, common_name=Mercia

, status=Kingdom

, status_text=Independent kingdom (527–879)Client state of Wessex ()

, life_span=527–918

, era=Heptarchy

, event_start=

, date_start=

, y ...

, Wiltshire

Wiltshire (; abbreviated Wilts) is a historic and ceremonial county in South West England with an area of . It is landlocked and borders the counties of Dorset to the southwest, Somerset to the west, Hampshire to the southeast, Gloucestershire ...

and Somerset

( en, All The People of Somerset)

, locator_map =

, coordinates =

, region = South West England

, established_date = Ancient

, established_by =

, preceded_by =

, origin =

, lord_lieutenant_office =Lord Lieutenant of Somerset

, lor ...

and forced to head off to the north-west, being finally overtaken and blockaded at Buttington. (Some identify this with Buttington Tump at the mouth of the River Wye

The River Wye (; cy, Afon Gwy ) is the fourth-longest river in the UK, stretching some from its source on Plynlimon in mid Wales to the Severn estuary. For much of its length the river forms part of the border between England and Wales ...

, others with Buttington near Welshpool

Welshpool ( cy, Y Trallwng) is a market town and community in Powys, Wales, historically in the county of Montgomeryshire. The town is from the Wales–England border and low-lying on the River Severn; its Welsh language name ''Y Trallwng'' m ...

.) An attempt to break through the English lines failed. Those who escaped retreated to Shoebury. After collecting reinforcements, they made a sudden dash across England and occupied the ruined Roman

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

* Rome, the capital city of Italy

* Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*''Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a lett ...

walls of Chester

Chester is a cathedral city and the county town of Cheshire, England. It is located on the River Dee, close to the English–Welsh border. With a population of 79,645 in 2011,"2011 Census results: People and Population Profile: Chester Loca ...

. The English did not attempt a winter blockade but contented themselves with destroying all the supplies in the district.

Early in 894 or 895 lack of food obliged the Danes to retire once more to Essex. At the end of the year, the Danes drew their ships up the River Thames

The River Thames ( ), known alternatively in parts as the The Isis, River Isis, is a river that flows through southern England including London. At , it is the longest river entirely in England and the Longest rivers of the United Kingdom, se ...

and the River Lea

The River Lea ( ) is in South East England. It originates in Bedfordshire, in the Chiltern Hills, and flows southeast through Hertfordshire, along the Essex border and into Greater London, to meet the River Thames at Bow Creek. It is one of ...

and fortified themselves north of London. A frontal attack on the Danish lines failed but later in the year, Alfred saw a means of obstructing the river to prevent the egress of the Danish ships. The Danes realised that they were outmanoeuvred, struck off north-westwards and wintered at Cwatbridge near Bridgnorth. The next year, 896 (or 897), they gave up the struggle. Some retired to Northumbria

la, Regnum Northanhymbrorum

, conventional_long_name = Kingdom of Northumbria

, common_name = Northumbria

, status = State

, status_text = Unified Anglian kingdom (before 876)North: Anglian kingdom (af ...

, some to East Anglia

East Anglia is an area in the East of England, often defined as including the counties of Norfolk, Suffolk and Cambridgeshire. The name derives from the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of the East Angles, a people whose name originated in Anglia, in ...

. Those who had no connections in England returned to the continent.

Military reorganisation

The Germanic tribes who invaded Britain in the fifth and sixth centuries relied upon the unarmoured infantry supplied by their tribal levy, or

The Germanic tribes who invaded Britain in the fifth and sixth centuries relied upon the unarmoured infantry supplied by their tribal levy, or fyrd

A fyrd () was a type of early Anglo-Saxon army that was mobilised from freemen or paid men to defend their Shire's lords estate, or from selected representatives to join a royal expedition. Service in the fyrd was usually of short duration and ...

, and it was upon this system that the military power of the several kingdoms of early Anglo-Saxon England depended. The fyrd was a local militia in the Anglo-Saxon shire in which all freemen had to serve; those who refused military service were subject to fines or loss of their land. According to the law code

A code of law, also called a law code or legal code, is a systematic collection of statutes. It is a type of legislation that purports to exhaustively cover a complete system of laws or a particular area of law as it existed at the time the cod ...

of King Ine of Wessex, issued in ,

Wessex's history of failures preceding Alfred's success in 878 emphasised to him that the traditional system of battle he had inherited played to the Danes' advantage. While the Anglo-Saxons and the Danes attacked settlements for plunder, they employed different tactics. In their raids the Anglo-Saxons traditionally preferred to attack head-on by assembling their forces in a shield wall

A shield wall ( or in Old English, in Old Norse) is a military formation that was common in ancient and medieval warfare. There were many slight variations of this formation,

but the common factor was soldiers standing shoulder to should ...

, advancing against their target and overcoming the oncoming wall marshalled against them in defence. The Danes preferred to choose easy targets, mapping cautious forays to avoid risking their plunder with high-stake attacks for more. Alfred determined their tactic was to launch small attacks from a secure base to which they could retreat should their raiders meet strong resistance.

The bases were prepared in advance, often by capturing an estate and augmenting its defences with ditches, ramparts and palisade

A palisade, sometimes called a stakewall or a paling, is typically a fence or defensive wall made from iron or wooden stakes, or tree trunks, and used as a defensive structure or enclosure. Palisades can form a stockade.

Etymology

''Palisade ...

s. Once inside the fortification, Alfred realised, the Danes enjoyed the advantage, better situated to outlast their opponents or crush them with a counter-attack because the provisions and stamina of the besieging forces waned.

The means by which the Anglo-Saxons marshalled forces to defend against marauders also left them vulnerable to the Vikings. It was the responsibility of the shire fyrd to deal with local raids. The king could call up the national militia to defend the kingdom but in the case of the Viking raids, problems with communication and raising supplies meant that the national militia could not be mustered quickly enough. It was only after the raids had begun that a call went out to landowners to gather their men for battle. Large regions could be devastated before the fyrd could assemble and arrive. Although the landowners were obliged to the king to supply these men when called, during the attacks in 878 many of them abandoned their king and collaborated with Guthrum.

With these lessons in mind Alfred capitalised on the relatively peaceful years following his victory at Edington with an ambitious restructuring of Saxon defences. On a trip to Rome Alfred had stayed with Charles the Bald

Charles the Bald (french: Charles le Chauve; 13 June 823 – 6 October 877), also known as Charles II, was a 9th-century king of West Francia (843–877), king of Italy (875–877) and emperor of the Carolingian Empire (875–877). After a se ...

, and it is possible that he may have studied how the Carolingian kings had dealt with Viking raiders. Learning from their experiences he was able to establish a system of taxation and defence for Wessex. There had been a system of fortifications in pre-Viking Mercia that may have been an influence. When the Viking raids resumed in 892 Alfred was better prepared to confront them with a standing, mobile field army, a network of garrisons and a small fleet of ships navigating the rivers and estuaries.

Administration and taxation

Tenants in Anglo-Saxon England had a threefold obligation based on their landholding: the so-called "common burdens" of military service, fortress work, and bridge repair. This threefold obligation has traditionally been called ''trinoda necessitas

Trinoda necessitas ("three-knotted obligation" in Latin) is a term used to refer to a "threefold tax" in Anglo-Saxon times. Subjects of an Anglo-Saxon king were required to yield three services: bridge-bote (repairing bridges and roads), burgh-b ...

'' or ''trimoda necessitas''. The Old English name for the fine due for neglecting military service was . To maintain the burh

A burh () or burg was an Old English fortification or fortified settlement. In the 9th century, raids and invasions by Vikings prompted Alfred the Great to develop a network of burhs and roads to use against such attackers. Some were new const ...

s, and to reorganise the fyrd as a standing army, Alfred expanded the tax and conscription system based on the productivity of a tenant's landholding. The hide was the basic unit of the system on which the tenant's public obligations were assessed. A hide is thought to represent the amount of land required to support one family. The hide differed in size according to the value and resources of the land and the landowner would have to provide service based on how many hides he owned.

Burghal system

The foundation of Alfred's new military defence system was a network of burhs, distributed at tactical points throughout the kingdom. There were thirty-three burhs, about apart, enabling the military to confront attacks anywhere in the kingdom within a day.

Alfred's burhs (of which 22 developed into

The foundation of Alfred's new military defence system was a network of burhs, distributed at tactical points throughout the kingdom. There were thirty-three burhs, about apart, enabling the military to confront attacks anywhere in the kingdom within a day.

Alfred's burhs (of which 22 developed into borough

A borough is an administrative division in various English-speaking countries. In principle, the term ''borough'' designates a self-governing walled town, although in practice, official use of the term varies widely.

History

In the Middle Ag ...

s) ranged from former Roman towns, such as Winchester

Winchester is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city in Hampshire, England. The city lies at the heart of the wider City of Winchester, a local government Districts of England, district, at the western end of the South Downs Nation ...

, where the stone walls

Stone walls are a kind of masonry construction that has been used for thousands of years. The first stone walls were constructed by farmers and primitive people by piling loose field stones into a dry stone wall. Later, mortar and plaster ...

were repaired and ditches added, to massive earthen walls surrounded by wide ditches, probably reinforced with wooden revetment

A revetment in stream restoration, river engineering or coastal engineering is a facing of impact-resistant material (such as stone, concrete, sandbags, or wooden piles) applied to a bank or wall in order to absorb the energy of incoming water a ...

s and palisades, such as at Burpham

Burpham is a rural village and civil parish in the Arun District of West Sussex, England. The village is on an arm of the River Arun slightly less than northeast of Arundel.

A slight minority of the population qualifies as within the worki ...

in West Sussex. The size of the burhs ranged from tiny outposts such as Pilton in Devon, to large fortifications in established towns, the largest being at Winchester.

A document now known as the ''Burghal Hidage

The Burghal Hidage () is an Anglo-Saxon document providing a list of over thirty fortified places (burhs), the majority being in the ancient Kingdom of Wessex, and the taxes (recorded as numbers of hides) assigned for their maintenance.Hill/ Rumb ...

'' provides an insight into how the system worked. It lists the hidage for each of the fortified towns contained in the document. Wallingford had a hidage of 2,400, which meant that the landowners there were responsible for supplying and feeding 2,400 men, the number sufficient for maintaining of wall. A total of 27,071 soldiers were needed, approximately one in four of all the free men in Wessex. Many of the burhs were twin towns that straddled a river and were connected by a fortified bridge, like those built by Charles the Bald

Charles the Bald (french: Charles le Chauve; 13 June 823 – 6 October 877), also known as Charles II, was a 9th-century king of West Francia (843–877), king of Italy (875–877) and emperor of the Carolingian Empire (875–877). After a se ...

a generation before. The double-burh blocked passage on the river, forcing Viking ships to navigate under a garrisoned bridge lined with men armed with stones, spears or arrows. Other burhs were sited near fortified royal villas, allowing the king better control over his strongholds.

The burhs were connected by a road system maintained for army use (known as herepaths). The roads allowed an army quickly to be assembled, sometimes from more than one burh, to confront the Viking invader. The road network posed significant obstacles to Viking invaders, especially those laden with booty. The system threatened Viking routes and communications making it far more dangerous for them. The Vikings lacked the equipment for a siege against a burh and a developed doctrine of siegecraft

A siege is a military blockade of a city, or fortress, with the intent of conquering by attrition, or a well-prepared assault. This derives from la, sedere, lit=to sit. Siege warfare is a form of constant, low-intensity conflict characteri ...

, having tailored their methods of fighting to rapid strikes and unimpeded retreats to well-defended fortifications. The only means left to them was to starve the burh into submission but this gave the king time to send his field army or garrisons from neighbouring burhs along the army roads. In such cases, the Vikings were extremely vulnerable to pursuit by the king's joint military forces. Alfred's burh system posed such a formidable challenge against Viking attack that when the Vikings returned in 892 and stormed a half-built, poorly garrisoned fortress up the Lympne

Lympne (), formerly also Lymne, is a village on the former shallow-gradient sea cliffs above the expansive agricultural plain of Romney Marsh in Kent. The settlement forms an L shape stretching from Port Lympne Zoo via Lympne Castle facing Lymp ...

estuary in Kent, the Anglo-Saxons were able to limit their penetration to the outer frontiers of Wessex and Mercia. Alfred's burghal system was revolutionary in its strategic conception and potentially expensive in its execution. His contemporary biographer Asser wrote that many nobles balked at the demands placed upon them even though they were for "the common needs of the kingdom".

English navy

Alfred also tried his hand at naval design. In 896 he ordered the construction of a small fleet, perhaps a dozen or so longships that, at 60 oars, were twice the size of Viking warships. This was not, as the Victorians asserted, the birth of the English Navy. Wessex had possessed a royal fleet before this. Alfred's older brother sub-kingÆthelstan of Kent

Æthelstan (; died c. 852) was the King of Kent from 839 to 851. He served under the authority and overlordship of his father, King Æthelwulf of Wessex, who appointed him. The late D, E and F versions of the ''Anglo-Saxon Chronicle'' describe � ...

and Ealdorman Ealhhere had defeated a Viking fleet in 851 capturing nine ships and Alfred had conducted naval actions in 882. The year 897 marked an important development in the naval power of Wessex. The author of the ''Anglo-Saxon Chronicle'' related that Alfred's ships were larger, swifter, steadier and rode higher in the water than either Danish or Frisian ships. It is probable that, under the classical tutelage of Asser, Alfred used the design of Greek and Roman warships, with high sides, designed for fighting rather than for navigation.

Alfred had seapower in mind; if he could intercept raiding fleets before they landed, he could spare his kingdom from being ravaged. Alfred's ships may have been superior in conception, but in practice they proved to be too large to manoeuvre well in the close waters of estuaries and rivers, the only places in which a naval battle could be fought. The warships of the time were not designed to be ship killers but rather troop carriers. It has been suggested that, like sea battles in late Viking age Scandinavia, these battles may have entailed a ship coming alongside an opposing vessel, lashing the two ships together and then boarding the craft. The result was a land battle involving hand-to-hand fighting on board the two lashed vessels.

In the one recorded naval engagement in 896, Alfred's new fleet of nine ships intercepted six Viking ships at the mouth of an unidentified river in the south of England. The Danes had beached half their ships and gone inland. Alfred's ships immediately moved to block their escape. The three Viking ships afloat attempted to break through the English lines. Only one made it; Alfred's ships intercepted the other two. Lashing the Viking boats to their own, the English crew boarded and proceeded to kill the Vikings. One ship escaped because Alfred's heavy ships became grounded when the tide went out. A land battle ensued between the crews. The Danes were heavily outnumbered, but as the tide rose, they returned to their boats which, with shallower drafts, were freed first. The English watched as the Vikings rowed past them but they suffered so many casualties (120 dead against 62 Frisians and English) that they had difficulty putting out to sea. All were too damaged to row around Sussex, and two were driven against the Sussex coast (possibly at Selsey Bill). The shipwrecked crew were brought before Alfred at Winchester and hanged.

Legal reform

In the late 880s or early 890s, Alfred issued a long '' domboc'' or

In the late 880s or early 890s, Alfred issued a long '' domboc'' or law code

A code of law, also called a law code or legal code, is a systematic collection of statutes. It is a type of legislation that purports to exhaustively cover a complete system of laws or a particular area of law as it existed at the time the cod ...

consisting of his own laws, followed by a code issued by his late seventh-century predecessor King Ine of Wessex

Ine, also rendered Ini or Ina, ( la, Inus; c. AD 670 – after 726) was King of Wessex from 689 to 726. At Ine's accession, his kingdom dominated much of southern England. However, he was unable to retain the territorial gains of his predecess ...

. Together these laws are arranged into 120 chapters. In his introduction Alfred explains that he gathered together the laws he found in many "synod

A synod () is a council of a Christian denomination, usually convened to decide an issue of doctrine, administration or application. The word '' synod'' comes from the meaning "assembly" or "meeting" and is analogous with the Latin word mean ...

-books" and "ordered to be written many of the ones that our forefathers observed—those that pleased me; and many of the ones that did not please me, I rejected with the advice of my councillors, and commanded them to be observed in a different way".

Alfred singled out in particular the laws that he "found in the days of Ine, my kinsman, or Offa

Offa (died 29 July 796 AD) was King of Mercia, a kingdom of Anglo-Saxon England, from 757 until his death. The son of Thingfrith and a descendant of Eowa, Offa came to the throne after a period of civil war following the assassination of Æth ...

, king of the Mercians, or King Æthelberht of Kent

Æthelberht (; also Æthelbert, Aethelberht, Aethelbert or Ethelbert; ang, Æðelberht ; 550 – 24 February 616) was King of Kent from about 589 until his death. The eighth-century monk Bede, in his ''Ecclesiastical History of the Engli ...

who first among the English people received baptism". He appended, rather than integrated, the laws of Ine into his code and although he included, as had Æthelbert, a scale of payments in compensation for injuries to various body parts, the two injury tariffs are not aligned. Offa is not known to have issued a law code, leading historian Patrick Wormald to speculate that Alfred had in mind the legatine capitulary

A capitulary (Medieval Latin ) was a series of legislative or administrative acts emanating from the Frankish court of the Merovingian and Carolingian dynasties, especially that of Charlemagne, the first emperor of the Romans in the west since t ...

of 786 that was presented to Offa by two papal legates

300px, A woodcut showing Henry II of England greeting the pope's legate.

A papal legate or apostolic legate (from the ancient Roman title '' legatus'') is a personal representative of the pope to foreign nations, or to some part of the Catholic ...

.

About a fifth of the law code is taken up by Alfred's introduction which includes translations into English of the Ten Commandments

The Ten Commandments (Biblical Hebrew עשרת הדברים \ עֲשֶׂרֶת הַדְּבָרִים, ''aséret ha-dvarím'', lit. The Decalogue, The Ten Words, cf. Mishnaic Hebrew עשרת הדיברות \ עֲשֶׂרֶת הַדִּבְ ...

, a few chapters from the Book of Exodus

The Book of Exodus (from grc, Ἔξοδος, translit=Éxodos; he, שְׁמוֹת ''Šəmōṯ'', "Names") is the second book of the Bible. It narrates the story of the Exodus, in which the Israelites leave slavery in Biblical Egypt through ...

, and the Apostolic Letter from the Acts of the Apostles

The Acts of the Apostles ( grc-koi, Πράξεις Ἀποστόλων, ''Práxeis Apostólōn''; la, Actūs Apostolōrum) is the fifth book of the New Testament; it tells of the founding of the Christian Church and the spread of its messag ...

(15:23–29). The introduction may best be understood as Alfred's meditation upon the meaning of Christian law. It traces the continuity between God's gift of law to Moses to Alfred's own issuance of law to the West Saxon people. By doing so, it linked the holy past to the historical present and represented Alfred's law-giving as a type of divine legislation.

Similarly Alfred divided his code into 120 chapters because 120 was the age at which Moses died and, in the number-symbolism of early medieval biblical exegetes, 120 stood for law. The link between Mosaic law

The Law of Moses ( he, תֹּורַת מֹשֶׁה ), also called the Mosaic Law, primarily refers to the Torah or the first five books of the Hebrew Bible. The law revealed to Moses by God.

Terminology

The Law of Moses or Torah of Moses (Hebrew ...

and Alfred's code is the Apostolic Letter which explained that Christ "had come not to shatter or annul the commandments but to fulfill them; and he taught mercy and meekness" (Intro, 49.1). The mercy that Christ infused into Mosaic law underlies the injury tariffs that figure so prominently in barbarian law codes since Christian synods "established, through that mercy which Christ taught, that for almost every misdeed at the first offence secular lords might with their permission receive without sin the monetary compensation which they then fixed"."Alfred" Intro, 49.7, trans.

The only crime that could not be compensated with a payment of money was treachery to a lord "since Almighty God adjudged none for those who despised Him, nor did Christ, the Son of God, adjudge any for the one who betrayed Him to death; and He commanded everyone to love his lord as Himself". Alfred's transformation of Christ's commandment, from "Love your neighbour as yourself" (Matt. 22:39–40) to love your secular lord as you would love the Lord Christ himself, underscores the importance that Alfred placed upon lordship which he understood as a sacred bond instituted by God for the governance of man.