Kenzō Tange on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

was a Japanese

Tange's interest in urban studies put him in a good position to handle post war reconstruction. In the summer of 1946 he was invited by the War Damage Rehabilitation Board to put forward a proposal for certain war damaged cities. He submitted plans for Hiroshima and

Tange's interest in urban studies put him in a good position to handle post war reconstruction. In the summer of 1946 he was invited by the War Damage Rehabilitation Board to put forward a proposal for certain war damaged cities. He submitted plans for Hiroshima and

Work on the Peace Center commenced in 1950. In addition to the axial nature of the design, the layout is similar to Tange's early competition arrangement for the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere Memorial Hall.

In the initial design the

Work on the Peace Center commenced in 1950. In addition to the axial nature of the design, the layout is similar to Tange's early competition arrangement for the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere Memorial Hall.

In the initial design the

The

The

The reconstruction plan of the capital city of

The reconstruction plan of the capital city of

The

The

In 1965 the Bureau International des Expositions decided that Japan should host the 1970 Exposition. of land in the Senri Hills near

In 1965 the Bureau International des Expositions decided that Japan should host the 1970 Exposition. of land in the Senri Hills near

Tange had left the Team X Otterlo conference early to take up a tenure at Massachusetts Institute of Technology. His experiences at the conference may have led him to set his fifth year students a project to design a 25-thousand-person residential community to be erected in Boston over the bay. The scheme comprised two giant A-frame structures that resembled Tange's competition entry for the World Health Organisation's headquarters on

Tange had left the Team X Otterlo conference early to take up a tenure at Massachusetts Institute of Technology. His experiences at the conference may have led him to set his fifth year students a project to design a 25-thousand-person residential community to be erected in Boston over the bay. The scheme comprised two giant A-frame structures that resembled Tange's competition entry for the World Health Organisation's headquarters on

The modular expansion of Tange's Metabolist visions had some influence on

The modular expansion of Tange's Metabolist visions had some influence on

Tange's Honor Is Well-Deserved

''Los Angeles Times'' (22 March 1987). *

Tange Associates official websiteThe Kenzō Tange Archive

Gift of Mrs. Takako Tange, 2011. Frances Loeb Library, Harvard University Graduate School of Design. {{DEFAULTSORT:Tange, Kenzo 1913 births 2005 deaths Japanese architects Pritzker Architecture Prize winners Recipients of the Order of the Sacred Treasure, 1st class Recipients of the Pour le Mérite (civil class) Recipients of the Praemium Imperiale Recipients of the Royal Gold Medal Recipients of the Order of Culture Recipients of the Legion of Honour People from Sakai, Osaka University of Tokyo alumni Nihon University alumni Expo '70 Japanese Roman Catholics Recipients of the AIA Gold Medal

architect

An architect is a person who plans, designs and oversees the construction of buildings. To practice architecture means to provide services in connection with the design of buildings and the space within the site surrounding the buildings that h ...

, and winner of the 1987 Pritzker Prize

The Pritzker Architecture Prize is an international architecture award presented annually "to honor a living architect or architects whose built work demonstrates a combination of those qualities of talent, vision and commitment, which has produ ...

for architecture

Architecture is the art and technique of designing and building, as distinguished from the skills associated with construction. It is both the process and the product of sketching, conceiving, planning, designing, and constructing building ...

. He was one of the most significant architects of the 20th century, combining traditional Japanese styles with modernism

Modernism is both a philosophy, philosophical and arts movement that arose from broad transformations in Western world, Western society during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The movement reflected a desire for the creation of new fo ...

, and designed major buildings on five continents. His career spanned the entire second half of the twentieth century, producing numerous distinctive buildings in Tokyo, other Japanese cities and cities around the world, as well as ambitious physical plans for Tokyo and its environs. Tange was also an influential patron of the Metabolist movement

was a post-war Japanese architectural movement that fused ideas about architectural megastructures with those of organic biological growth. It had its first international exposure during CIAM's 1959 meeting and its ideas were tentatively tested ...

. He said: "It was, I believe, around 1959 or at the beginning of the sixties that I began to think about what I was later to call structuralism

In sociology, anthropology, archaeology, history, philosophy, and linguistics, structuralism is a general theory of culture and methodology that implies that elements of human culture must be understood by way of their relationship to a broader ...

", (cited in ''Plan'' 2/1982, Amsterdam), a reference to the architectural movement known as Dutch Structuralism.

Influenced from an early age by the Swiss modernist, Le Corbusier

Charles-Édouard Jeanneret (6 October 188727 August 1965), known as Le Corbusier ( , , ), was a Swiss-French architect, designer, painter, urban planner, writer, and one of the pioneers of what is now regarded as modern architecture. He was ...

, Tange gained international recognition in 1949 when he won the competition for the design of Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park

is a memorial park in the center of Hiroshima, Japan. It is dedicated to the legacy of Hiroshima as the first city in the world to suffer a Atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, nuclear attack at the end of World War II, and to the memorie ...

. He was a member of CIAM (Congres Internationaux d'Architecture Moderne) in the 1950s. He did not join the group of younger CIAM architects known as Team X

Team 10 – just as often referred to as Team X or Team Ten – was a group of architects and other invited participants who assembled starting in July 1953 at the 9th Congress of the International Congresses of Modern Architecture (CIAM) and c ...

, though his 1960 Tokyo Bay plan was influential for Team 10 in the 1960s, as well as the group that became Metabolism

Metabolism (, from el, μεταβολή ''metabolē'', "change") is the set of life-sustaining chemical reactions in organisms. The three main functions of metabolism are: the conversion of the energy in food to energy available to run cell ...

.

His university studies on urbanism put him in an ideal position to handle redevelopment projects after the Second World War. His ideas were explored in designs for Tokyo

Tokyo (; ja, 東京, , ), officially the Tokyo Metropolis ( ja, 東京都, label=none, ), is the capital and largest city of Japan. Formerly known as Edo, its metropolitan area () is the most populous in the world, with an estimated 37.468 ...

and Skopje

Skopje ( , , ; mk, Скопје ; sq, Shkup) is the capital and largest city of North Macedonia. It is the country's political, cultural, economic, and academic centre.

The territory of Skopje has been inhabited since at least 4000 BC; r ...

. Tange's work influenced a generation of architects across the world.

Early life

Born on 4 September 1913 inSakai

is a city located in Osaka Prefecture, Japan. It has been one of the largest and most important seaports of Japan since the medieval era. Sakai is known for its keyhole-shaped burial mounds, or kofun, which date from the fifth century and incl ...

, Japan, Tange spent his early life in the Chinese cities of Hankow

Hankou, alternately romanized as Hankow (), was one of the three towns (the other two were Wuchang and Hanyang) merged to become modern-day Wuhan city, the capital of the Hubei province, China. It stands north of the Han and Yangtze Rivers whe ...

and Shanghai

Shanghai (; , , Standard Mandarin pronunciation: ) is one of the four direct-administered municipalities of the People's Republic of China (PRC). The city is located on the southern estuary of the Yangtze River, with the Huangpu River flow ...

; he and his family returned to Japan after learning of the death of one of his uncles. In contrast to the green lawns and red bricks in their Shanghai abode, the Tange family took up residence in a thatched roof farmhouse in Imabari

270px, Imabari City Hall

270px, Aerial view of Imabari city center

is a city in Ehime Prefecture, Japan. It is the second largest city in Ehime Prefecture. , the city had an estimated population of 152,111 in 75947 households and a population ...

on the island of Shikoku

is the smallest of the four main islands of Japan. It is long and between wide. It has a population of 3.8 million (, 3.1%). It is south of Honshu and northeast of Kyushu. Shikoku's ancient names include ''Iyo-no-futana-shima'' (), '' ...

.Stewart (1987), p. 170

After finishing middle school, Tange moved to Hiroshima

is the capital of Hiroshima Prefecture in Japan. , the city had an estimated population of 1,199,391. The gross domestic product (GDP) in Greater Hiroshima, Hiroshima Urban Employment Area, was US$61.3 billion as of 2010. Kazumi Matsui h ...

in 1930 to attend high school. It was here that he first encountered the works of Swiss modernist, Le Corbusier

Charles-Édouard Jeanneret (6 October 188727 August 1965), known as Le Corbusier ( , , ), was a Swiss-French architect, designer, painter, urban planner, writer, and one of the pioneers of what is now regarded as modern architecture. He was ...

. His discovery of the drawings of the Palace of the Soviets

The Palace of the Soviets (russian: Дворец Советов, ''Dvorets Sovetov'') was a project to construct a political convention center in Moscow on the site of the demolished Cathedral of Christ the Saviour. The main function of the p ...

in a foreign art journal convinced him to become an architect. Although he graduated from high school, Tange's poor results in mathematics and physics meant that he had to pass entrance exams to qualify for admission to the prestigious universities. He spent two years doing so and during that time, he read extensively about western philosophy. Tange also enrolled in the film division at Nihon University

, abbreviated as , is a private university, private research university in Japan. Its predecessor, Nihon Law School (currently the Department of Law), was founded by Yamada Akiyoshi, the Minister of Justice (Japan), Minister of Justice, in 1889. ...

's art department to dodge Japan's drafting of young men to its military and seldom attended classes.

In 1935 Tange began the tertiary studies he desired at University of Tokyo

, abbreviated as or UTokyo, is a public research university located in Bunkyō, Tokyo, Japan. Established in 1877, the university was the first Imperial University and is currently a Top Type university of the Top Global University Project by ...

's architecture department. He studied under Hideto Kishida and Shozo Uchida. Although Tange was fascinated by the photographs of Katsura villa

The , or Katsura Detached Palace, is an Imperial residence with associated gardens and outbuildings in the western suburbs of Kyoto, Japan. Located on the western bank of the Katsura River in Katsura, Nishikyō-ku, the Villa is 8km distant fr ...

that sat on Kishida's desk, his work was inspired by Le Corbusier. His graduation project was a seventeen-hectare (42-acre) development set in Tokyo's Hibiya Park

Hibiya Park (日比谷公園 ''Hibiya Kōen'') is a park in Chiyoda City, Tokyo, Japan. It covers an area of 161,636.66 m2 (40 acres) between the east gardens of the Imperial Palace to the north, the Shinbashi district to the southeast and the Ka ...

.Stewart (1987), p. 171

Early career

After graduating from the university, Tange started to work as an architect at the office ofKunio Maekawa

was a Japanese architect and a key figure in Japanese postwar modernism. His distinctive architectural language deftly blended together elements of traditional Japanese design and modernist tenets from Europe, drawing from early career work exp ...

. During his employment, he travelled to Manchuria

Manchuria is an exonym (derived from the endo demonym " Manchu") for a historical and geographic region in Northeast Asia encompassing the entirety of present-day Northeast China (Inner Manchuria) and parts of the Russian Far East (Outer Manc ...

, participating in an architectural design competition

An architectural design competition is a type of design competition in which an organization that intends on constructing a new building invites architects to submit design proposals. The winning design is usually chosen by an independent panel o ...

for a bank, and toured Japanese-occupied Jehol on his return. When the Second World War started, he left Maekawa to rejoin the University of Tokyo as a postgraduate student. He developed an interest in urban design, and referencing only the resources available in the university library, he embarked on a study of Greek and Roman marketplaces. In 1942, Tange entered a competition for the design of the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere Memorial Hall. He was awarded first prize for a design that would have been situated at the base of Mount Fuji

, or Fugaku, located on the island of Honshū, is the highest mountain in Japan, with a summit elevation of . It is the second-highest volcano located on an island in Asia (after Mount Kerinci on the island of Sumatra), and seventh-highest p ...

; the hall he conceived was a fusion of Shinto

Shinto () is a religion from Japan. Classified as an East Asian religion by scholars of religion, its practitioners often regard it as Japan's indigenous religion and as a nature religion. Scholars sometimes call its practitioners ''Shintois ...

shrine architecture and the plaza on Capitoline Hill

The Capitolium or Capitoline Hill ( ; it, Campidoglio ; la, Mons Capitolinus ), between the Forum and the Campus Martius, is one of the Seven Hills of Rome.

The hill was earlier known as ''Mons Saturnius'', dedicated to the god Saturn. Th ...

in Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus (legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

. The design was not realised.

In 1946, Tange became an assistant professor at the university and opened Tange Laboratory. In 1963, he was promoted to professor of the Department of Urban Engineering. His students included Sachio Otani, Kisho Kurokawa

(April 8, 1934 – October 12, 2007) was a leading Japanese architect and one of the founders of the Metabolist Movement.

Biography

Born in Kanie, Aichi, Kurokawa studied architecture at Kyoto University, graduating with a bachelor's d ...

, Arata Isozaki

Arata Isozaki (磯崎 新, ''Isozaki Arata''; born 23 July 1931) is a Japanese architect, urban designer, and theorist from Ōita. He was awarded the RIBA Gold Medal in 1986 and the Pritzker Architecture Prize in 2019.

Biography

Isozaki was ...

, Hajime Yatsuka and Fumihiko Maki

is a Japanese architect who teaches at Keio University SFC. In 1993, he received the Pritzker Prize for his work, which often explores pioneering uses of new materials and fuses the cultures of east and west.

Early life

Maki was born in Tokyo. A ...

.

Post war reconstruction

Tange's interest in urban studies put him in a good position to handle post war reconstruction. In the summer of 1946 he was invited by the War Damage Rehabilitation Board to put forward a proposal for certain war damaged cities. He submitted plans for Hiroshima and

Tange's interest in urban studies put him in a good position to handle post war reconstruction. In the summer of 1946 he was invited by the War Damage Rehabilitation Board to put forward a proposal for certain war damaged cities. He submitted plans for Hiroshima and Maebashi

is the capital city of Gunma Prefecture, in the northern Kantō region of Japan. , the city had an estimated population of 335,352 in 151,171 households, and a population density of 1100 persons per km2. The total area of the city is . It wa ...

. His design for an airport in Kanon, Hiroshima was accepted and built, but a seaside park in Ujina was not.

The Hiroshima authorities took advice about the city's reconstruction from foreign consultants, and in 1947 Tam Deling, an American park planner, suggested they build a Peace Memorial and preserve buildings situated near ground zero

In relation to nuclear explosions and other large bombs, ground zero (also called surface zero) is the point on the Earth's surface closest to a detonation. In the case of an explosion above the ground, ''ground zero'' is the point on the ground ...

, that point directly below the explosion of the atomic bomb. In 1949 the authorities enacted the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Reconstruction Act, which gave the city access to special grant aid, and in August 1949, an international competition was announced for the design of the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park.

Tange was awarded first prize for a design that proposed a museum whose axis runs through the park, intersecting Peace Boulevard

is one of the main streets in Hiroshima, Japan, which faces the south side of Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park.

The street is wide and runs {{convert, 3.6, km, abbr=off from east to west, between Tsurumi-cho and Fukushima-cho within the green ...

and the atomic bomb dome. The building is raised on massive columns

A column or pillar in architecture and structural engineering is a structural element that transmits, through compression, the weight of the structure above to other structural elements below. In other words, a column is a compression member. ...

, which frame the view along the structure's axis.

Projects

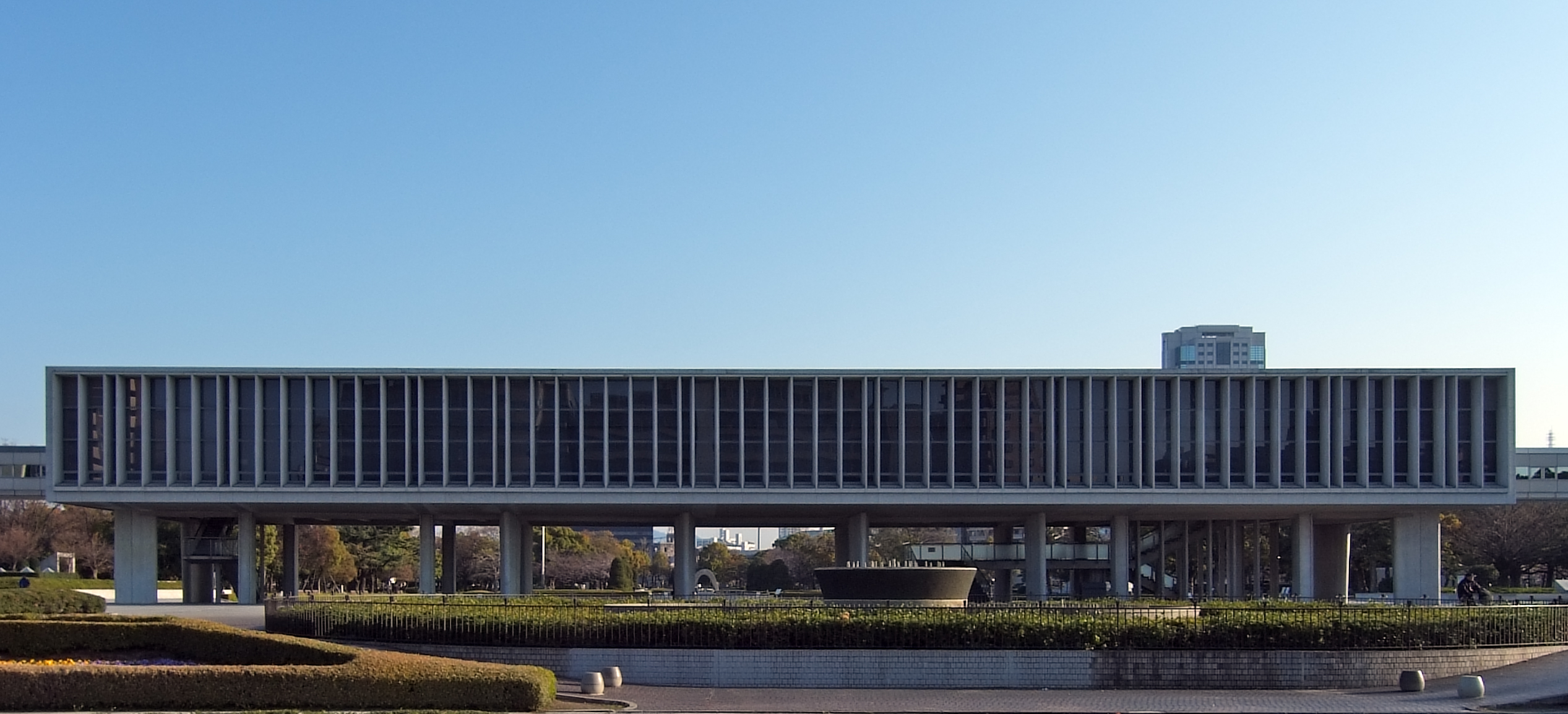

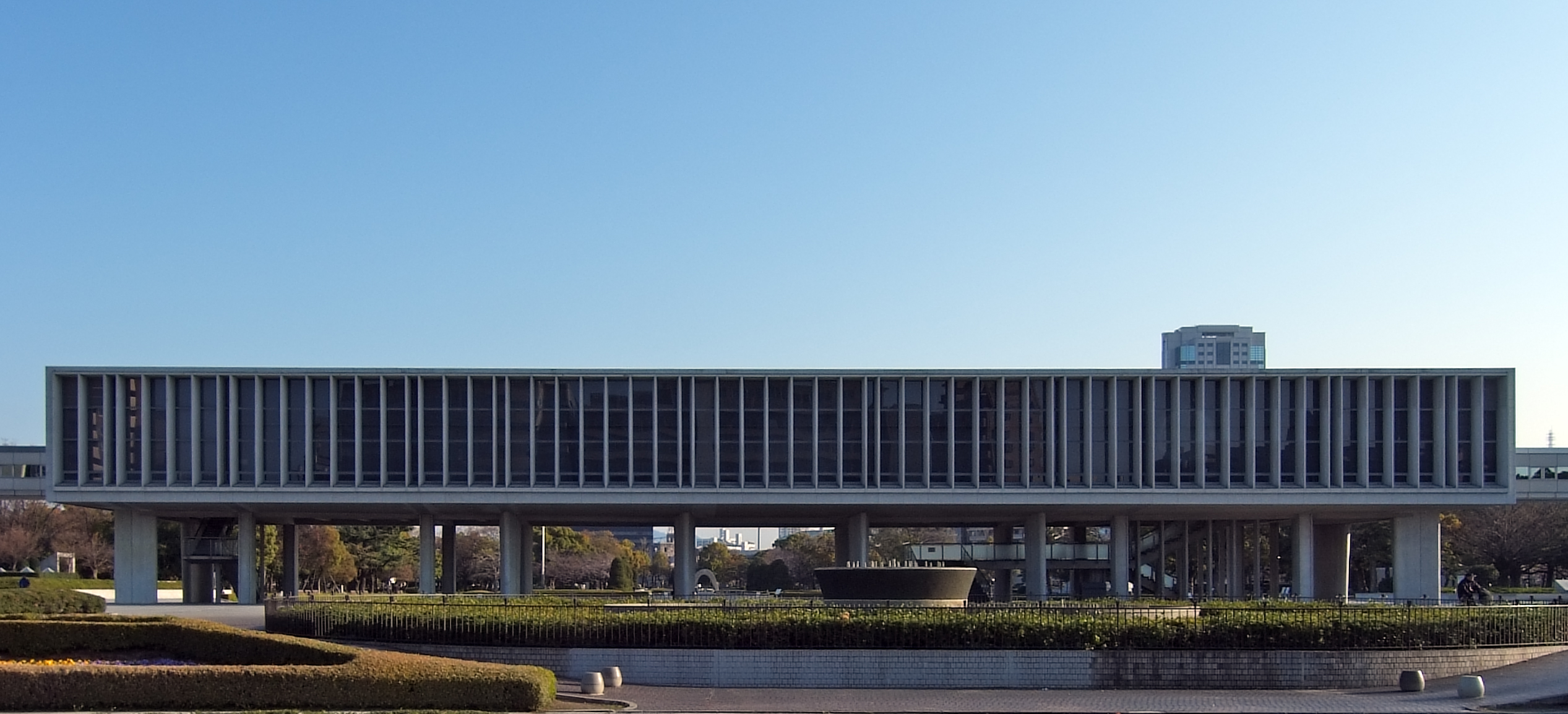

Peace Center in Hiroshima

Work on the Peace Center commenced in 1950. In addition to the axial nature of the design, the layout is similar to Tange's early competition arrangement for the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere Memorial Hall.

In the initial design the

Work on the Peace Center commenced in 1950. In addition to the axial nature of the design, the layout is similar to Tange's early competition arrangement for the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere Memorial Hall.

In the initial design the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum

The Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum is a museum located in Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park, in central Hiroshima, Japan, dedicated to documenting the atomic bombing of Hiroshima in World War II.

The museum was established in August 1955 with the ...

was dominated by adjoining utility buildings, which were linked to it by high-level walkways. Tange refined this concept to place the museum prominently at the centre, separate from the utility buildings (only one of which was subsequently designed by him). In addition to architectural symbolism, he thought it important for the design to centre around the building that houses the information about the atomic explosion.

The museum is constructed from bare reinforced concrete. The primary museum floor is lifted six metres above the ground on huge piloti and is accessible via a free-standing staircase. The rhythmical facade comprises vertical elements that repeat outwards from the centre. Like the exterior, the interior is finished with rough concrete; the idea was to keep the surfaces plain so that nothing could distract the visitor from the contents of the exhibits.Kulterman (1970), p. 18

The Peace Plaza is the backdrop for the museum. The plaza was designed to allow 50 thousand people to gather around the peace monument in the centre. Tange also designed the Cenotaph

A cenotaph is an empty tomb or a monument erected in honour of a person or group of people whose remains are elsewhere. It can also be the initial tomb for a person who has since been reinterred elsewhere. Although the vast majority of cenot ...

monument as an arch composed of two hyperbolic paraboloid

In geometry, a paraboloid is a quadric surface that has exactly one axis of symmetry and no center of symmetry. The term "paraboloid" is derived from parabola, which refers to a conic section that has a similar property of symmetry.

Every plane ...

s, said to be based on traditional Japanese ceremonial tombs from the Kofun Period

The is an era in the history of Japan from about 300 to 538 AD (the date of the introduction of Buddhism), following the Yayoi period. The Kofun and the subsequent Asuka periods are sometimes collectively called the Yamato period. This period is ...

.

Ise Shrine

In 1953 Tange and the architectural journalist and critic Noboru Kawazoe were invited to attend the reconstruction of theIse Shrine

The , located in Ise, Mie Prefecture of Japan, is a Shinto shrine dedicated to the sun goddess Amaterasu. Officially known simply as , Ise Jingū is a shrine complex composed of many Shinto shrines centered on two main shrines, and .

The Inner ...

. The shrine has been reconstructed every 20 years and in 1953 it was the 59th iteration. Normally the reconstruction process was a very closed affair but this time the ceremony was opened to architects and journalists to document the event. The ceremony coincided with the end of the American Occupation and it seemed to symbolise a new start in Japanese architecture. In 1965 when Tange and Kawazoe published the book ''Ise: Prototype of Japanese Architecture'', he likened the building to a modernist structure: an honest expression of materials, a functional design and prefabricated elements.

Kagawa Prefectural Government Hall

The Kagawa Prefectural Government Hall on the island of Shikoku was completed in 1958. Its expressive construction could be likened to the Daibutsu style seen at theTōdai-ji

is a Buddhist temple complex that was once one of the powerful Nanto Shichi Daiji, Seven Great Temples, located in the city of Nara, Nara, Nara, Japan. Though it was originally founded in the year 738 CE, Tōdai-ji was not opened until the year ...

in Nara

The National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) is an " independent federal agency of the United States government within the executive branch", charged with the preservation and documentation of government and historical records. It i ...

. The columns on the elevation bore only vertical loads so Tange was able to design them to be thin, maximising the surfaces for glazing. Although the hall has been called one of his finest projects, it drew criticism at the time of its construction for relying too heavily on tradition.

Tange's own home

Tange's own home, designed in 1951 and completed in 1953, uses a similar skeleton structure raised off the ground as the Hiroshima Peace Museum; however, it is fused with a more traditional Japanese design that uses timber and paper. The house is based on the traditional Japanese module of thetatami

A is a type of mat used as a flooring material in traditional Japanese-style rooms. Tatamis are made in standard sizes, twice as long as wide, about 0.9 m by 1.8 m depending on the region. In martial arts, tatami are the floor used for traini ...

mat, with the largest rooms designed to have flexibility so that they can be separated into three smaller rooms by fusuma

In Japanese architecture, are vertical rectangular panels which can slide from side to side to redefine spaces within a room, or act as doors. They typically measure about wide by tall, the same size as a ''tatami'' mat, and are thick. The ...

sliding doors. The facade is designed with a rhythmic pattern; it comprises two types of facade designs ("a" and "b") that are ordered laterally in an a-b-a-a-b-a arrangement. The house is topped with a two-tier roof. Kazuo Shinohara

was a Japanese architect, forming what is now widely known as the "Shinohara School", which has been linked to the works of Toyo Ito, Kazunari Sakamoto and Itsuko Hasegawa. As architectural critic Thomas Daniell put it, "A key figure who explic ...

's 1954 house at Kugayama

is a neighbourhood of Tokyo in Suginami ward, west of Shinjuku in Japan.

Kugayama is a residential community

A residential community is a community, usually a small town or city, that is composed mostly of residents, as opposed to co ...

is remarkably similar in its design, although it is built with steel and has a simpler rhythm in its facade.

Town Hall, Kurashiki

The fortress-like town hall inKurashiki

is a historic city located in western Okayama Prefecture, Japan, sitting on the Takahashi River, on the coast of the Inland Sea. As of March 31, 2017, the city has an estimated population of 483,576 and a population density of 1,400 persons per ...

was designed in 1958 and completed in 1960. When it was constructed it was situated on the edge of the old town centre connecting it with the newer areas of the town. Kurashiki is better known as a tourist spot for its old Machiya

are traditional wooden townhouses found throughout Japan and typified in the historical capital of Kyoto. (townhouses) and (farm dwellings) constitute the two categories of Japanese vernacular architecture known as (folk dwellings).

orig ...

style houses.

Set in an open square, the building sits on massive columns that taper inwards as they rise. The elevation consists of horizontal planks (some of which are omitted to create windows) which overlap at the corners in a "log cabin" effect. The entrance is covered with a heavy projecting concrete canopy which leads to a monumental entrance hall. The stair to this hall ascends in cantilevered straight flights to the left and right. The walls to this interior are bare shuttered concrete punctured by windows reminiscent of Le Corbusier's La Tourette

La Tourette () is a commune in the Loire department in central France.

Population

See also

*Communes of the Loire department

The following is a list of the 323 communes of the Loire department of France.

The communes cooperate in the fol ...

. The Council Chamber is a separate building whose raked roof has seating on top of it to form an external performance space.

Tokyo Olympic arenas

The

The Yoyogi National Gymnasium

Yoyogi National Gymnasium, officially is an indoor arena located at Yoyogi Park in Shibuya, Tokyo, Japan, which is famous for its suspension roof design.

It was designed by Kenzo Tange and built between 1961 and 1964 to house swimming and d ...

is situated in an open area in Yoyogi Park

is a park in Shibuya, Tokyo, Japan. It is located adjacent to Harajuku Station and Meiji Shrine in Yoyogikamizonochō. The park is a popular Tokyo destination, especially on Sundays when it is used as a gathering place for Japanese rock music ...

on an adjacent axis to the Meiji Shrine

, is a Shinto shrine in Shibuya, Tokyo, that is dedicated to the deified spirits of Emperor Meiji and his wife, Empress Shōken. The shrine does not contain the emperor's grave, which is located at Fushimi-momoyama, south of Kyoto.

History

Af ...

. The gymnasium and swimming pool were designed by Tange for the 1964 Tokyo Olympics

The , officially the and commonly known as Tokyo 1964 ( ja, 東京1964), were an international multi-sport event held from 10 to 24 October 1964 in Tokyo, Japan. Tokyo had been awarded the organization of the 1940 Summer Olympics, but this hon ...

, which were the first Olympics held in Asia. Tange began his designs in 1961 and the plans were approved by the Ministry of Education in January 1963. The buildings were placed to optimize space available for parking and to permit the smoothest transition of incoming and outgoing people.Kulterman (1970), p. 204

Inspired by the skyline of the Colosseum

The Colosseum ( ; it, Colosseo ) is an oval amphitheatre in the centre of the city of Rome, Italy, just east of the Roman Forum. It is the largest ancient amphitheatre ever built, and is still the largest standing amphitheatre in the world to ...

in Rome, the roofs have a skin suspended from two masts. The buildings were inspired by Le Corbusier's Philips Pavilion

The Philips Pavilion was a World's Fair pavilion designed for Expo '58 in Brussels by the office of Le Corbusier. Commissioned by electronics manufacturer Philips, the pavilion was designed to house a multimedia spectacle that celebrated postwar ...

designed for Brussels' World Fair, and the Ingalls Rink

David S. Ingalls Rink is a hockey rink in New Haven, Connecticut, designed by architect Eero Saarinen and built between 1953 and 1958 for Yale University. It is commonly referred to as The Whale, due to its shape. The building was constructed fo ...

, Yale University's hockey area, by Eero Saarinen

Eero Saarinen (, ; August 20, 1910 – September 1, 1961) was a Finnish-American architect and industrial designer noted for his wide-ranging array of designs for buildings and monuments. Saarinen is best known for designing the General Motors ...

(both structures were completed in 1958). The roof of the Philips Pavilion was created by complex hyperbolic paraboloid surfaces stretched between cables. In both cases Tange took Western ideas and adapted them to meet Japanese requirements.

The gymnasium has a capacity of approximately 16,000 and the smaller building can accommodate up to 5,300 depending on the events that are taking place. At the time it was built, the gymnasium had the world's largest suspended roof span. Two reinforced concrete pillars support a pre-stressed steel net onto which steel plates are attached. The bottom anchoring of this steel net is a heavy concrete support system which forms a distinct curve on the interior and exterior of the building. In the interior, this structural anchor is used to support the grandstand seats. The overall curvature of the roof helps protect the building from the damaging effects of strong winds.

Tange won a Pritzker Prize

The Pritzker Architecture Prize is an international architecture award presented annually "to honor a living architect or architects whose built work demonstrates a combination of those qualities of talent, vision and commitment, which has produ ...

for the design; the citation described the gymnasium as "among the most beautiful buildings of the 20th century".

Plan for Skopje

The reconstruction plan of the capital city of

The reconstruction plan of the capital city of Skopje

Skopje ( , , ; mk, Скопје ; sq, Shkup) is the capital and largest city of North Macedonia. It is the country's political, cultural, economic, and academic centre.

The territory of Skopje has been inhabited since at least 4000 BC; r ...

, then part of the Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia

The Socialist Republic of Macedonia ( mk, Социјалистичка Република Македонија, Socijalistička Republika Makedonija), or SR Macedonia, commonly referred to as Socialist Macedonia or Yugoslav Macedonia, was ...

following a major earthquake was won by Tange's architecture team in 1965. The project was significant because of its international influence, however for Tange it was model case for urban reconstruction to realise modern architecture principles. It is the first time that a Japanese architect was invited by an international body to participate in an urban development of this scale.

Supreme Court Building of Pakistan

The

The Supreme Court of Pakistan Building

The Supreme Court Building is the official and principal site for the Supreme Court of Pakistan, located at 44000 Constitution Avenue in Islamabad, Pakistan. Completed in 1993, it is situated on the Constitution Avenue and is flanked by the Prim ...

is the official and principal workplace of the Supreme Court of Pakistan

The Supreme Court of Pakistan ( ur, ; ''Adālat-e-Uzma Pākistān'') is the apex court in the judicial hierarchy of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan.

Established in accordance to thePart VIIof the Constitution of Pakistan, it has ultimate a ...

, located in 44000 Constitution Avenue

Constitution Avenue is a major east–west street in the northwest and northeast quadrants of the city of Washington, D.C., in the United States. It was originally known as B Street, and its western section was greatly lengthened and widened betw ...

Islamabad

Islamabad (; ur, , ) is the capital city of Pakistan. It is the country's ninth-most populous city, with a population of over 1.2 million people, and is federally administered by the Pakistani government as part of the Islamabad Capital T ...

, Pakistan. Completed in 1993, it is flanked by the Prime Minister's Secretariat to the south and President's House and the Parliament Building to the north.

Designed by Tange, to a design brief prepared by the PEPAC, the complex was engineered and built by CDA Engineering and Siemens Engineering.

Osaka Exposition 1970

In 1965 the Bureau International des Expositions decided that Japan should host the 1970 Exposition. of land in the Senri Hills near

In 1965 the Bureau International des Expositions decided that Japan should host the 1970 Exposition. of land in the Senri Hills near Osaka

is a designated city in the Kansai region of Honshu in Japan. It is the capital of and most populous city in Osaka Prefecture, and the third most populous city in Japan, following Special wards of Tokyo and Yokohama. With a population of 2. ...

were put aside for its use. Tange and Uzo Nishiyama were appointed as planners for the masterplan by the Theme Committee. Tange assembled a group of twelve architects to design the infrastructure and facilities for the Expo.

At the centre of the Expo was the Festival Plaza. Tange conceived that this plaza (with its oversailing space frame roof) would connect the display spaces and create a setting for a "festival". The plaza divided the site into a northern zone for pavilions and a southern zone for administration facilities. The zones were interconnected with moving pathways.

Architectural circle

Congrès International d'Architecture Moderne

Tange's first placing in the design competition for the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park gained him recognition from Kunio Maekawa. The elder architect invited Tange to attend theCongrès International d'Architecture Moderne

A congress is a formal meeting of the representatives of different countries, constituent states, organizations, trade unions, political parties, or other groups. The term originated in Late Middle English to denote an encounter (meeting of ad ...

(CIAM). Founded in 1928, this organization of planners and architects had initially promoted architecture in economic and social context, but at its fourth meeting in 1933 (under the direction of Le Corbusier) it debated the notion of the "Functional City". This led to a series of proposals on urban planning known as " The Athens Charter". By the 1951 CIAM meeting that was held in Hoddesdon

Hoddesdon () is a town in the Borough of Broxbourne, Hertfordshire, lying entirely within the London Metropolitan Area and Greater London Urban Area. The area is on the River Lea and the Lee Navigation along with the New River.

Hoddesdon is ...

, England, to which Tange was invited, the Athens Charter came under debate by younger members of the group (including Tange) who found the Charter too vague in relation to city expansion. The "Athens Charter" promoted the idea that a city gains character from its continual changes over many years; this notion was written before the advent of mass bombings and the Second World War and therefore held little meaning for Tange who had evidenced the destruction of Hiroshima. The discussions at Hoddesdon sowed discontent within CIAM that eventually contributed to its breakup after their Dubrovnik

Dubrovnik (), historically known as Ragusa (; see notes on naming), is a city on the Adriatic Sea in the region of Dalmatia, in the southeastern semi-exclave of Croatia. It is one of the most prominent tourist destinations in the Mediterran ...

meeting in 1956; the younger members of CIAM formed a splinter group known as Team X, which Tange later joined. Tange presented various designs to Team X in their meetings. At a 1959 meeting in Otterlo

Otterlo is a village in the municipality of Ede of province of Gelderland in the Netherlands, in or near the Nationaal Park De Hoge Veluwe.

The Kröller-Müller Museum, named after Helene Kröller-Müller, is situated nearby and has the world's ...

, Holland, one of his presentations included an unrealised project by Kiyonori Kikutake

(April 1, 1928 – December 26, 2011) was a prominent Japanese architect known as one of the founders of the Japanese Metabolist group. He was also the tutor and employer of several important Japanese architects, such as Toyo Ito, Shōzō Uc ...

; this project became the basis of the Metabolist Movement

was a post-war Japanese architectural movement that fused ideas about architectural megastructures with those of organic biological growth. It had its first international exposure during CIAM's 1959 meeting and its ideas were tentatively tested ...

.

When Tange travelled back to Japan from the 1951 CIAM meeting, he visited Le Corbusier's nearly complete Unité d'Habitation

{{Infobox company

, name = Moldtelecom

, logo =

, type = JSC

, foundation = 1 April 1993

, location = Chişinău, Moldova

, key_people = Alexandru Ciubuc CEO interim

, num_employees = 2,750 employees As of 2019

, industry = Telecommunica ...

in Marseilles, France. He also looked at the sketches for the new capital of Punjab

Punjab (; Punjabi: پنجاب ; ਪੰਜਾਬ ; ; also romanised as ''Panjāb'' or ''Panj-Āb'') is a geopolitical, cultural, and historical region in South Asia, specifically in the northern part of the Indian subcontinent, comprising ...

at Chandigarh

Chandigarh () is a planned city in India. Chandigarh is bordered by the state of Punjab to the west and the south, and by the state of Haryana to the east. It constitutes the bulk of the Chandigarh Capital Region or Greater Chandigarh, which al ...

, India.Stewart (1987), p. 175

Tokyo World Design Conference and urban planning

Tange had left the Team X Otterlo conference early to take up a tenure at Massachusetts Institute of Technology. His experiences at the conference may have led him to set his fifth year students a project to design a 25-thousand-person residential community to be erected in Boston over the bay. The scheme comprised two giant A-frame structures that resembled Tange's competition entry for the World Health Organisation's headquarters on

Tange had left the Team X Otterlo conference early to take up a tenure at Massachusetts Institute of Technology. His experiences at the conference may have led him to set his fifth year students a project to design a 25-thousand-person residential community to be erected in Boston over the bay. The scheme comprised two giant A-frame structures that resembled Tange's competition entry for the World Health Organisation's headquarters on Lake Geneva

, image = Lake Geneva by Sentinel-2.jpg

, caption = Satellite image

, image_bathymetry =

, caption_bathymetry =

, location = Switzerland, France

, coords =

, lake_type = Glacial lak ...

. Both this scheme and the earlier ones by Kikutake formed the basis of Tange's speech to the Tokyo World Design Conference in 1960. In his speech he used words such as "cell" and "metabolism" in relation to urban design. The Metabolist movement grew out of discussions with other members of the conference. Amongst them were Kisho Kurokawa

(April 8, 1934 – October 12, 2007) was a leading Japanese architect and one of the founders of the Metabolist Movement.

Biography

Born in Kanie, Aichi, Kurokawa studied architecture at Kyoto University, graduating with a bachelor's d ...

, Junzo Sakakura

was a Japanese architect and former president of the Architectural Association of Japan.

After graduating from university he worked in Le Corbusier's atelier in Paris. He rose to the position of studio chief during his seven-year stay in the st ...

, Alison and Peter Smithson

Alison Margaret Smithson (22 June 1928 – 14 August 1993) and Peter Denham Smithson (18 September 1923 – 3 March 2003) were English architects who together formed an architectural partnership, and are often associated with the New Brutalism ...

, Louis Kahn

Louis Isadore Kahn (born Itze-Leib Schmuilowsky; – March 17, 1974) was an Estonian-born American architect based in Philadelphia. After working in various capacities for several firms in Philadelphia, he founded his own atelier in 1935. Whi ...

, Jean Prouvé

Jean Prouvé (8 April 1901 – 23 March 1984) was a French metal worker, self-taught architect and designer. Le Corbusier designated Prouvé a constructeur, blending architecture and engineering. Prouvé's main achievement was transferring man ...

, B. V. Doshi

Balkrishna Vithaldas Doshi OAL (born 26 August 1927) is an Indian architect. He is considered to be an important figure of Indian architecture and noted for his contributions to the evolution of architectural discourse in India. Having worked ...

and Jacob Bakema

Jacob Berend "Jaap" Bakema (8 March 1914 – 20 February 1981) was a Dutch modernist architect, notable for design of public housing and involvement in the reconstruction of Rotterdam after the Second World War.

Born in Groningen, Bakema studi ...

. The conference ended with Tange's presentation of the Boston plan and his own scheme, "The Tokyo Plan – 1960".

Tange argued that the normal urban pattern of a radial centripetal transportation system was a relic of the Middle Ages and would not handle the strain placed upon it by the world's mega cities, which he qualified as those with populations greater than 10 million. Rather than building up a city from a civic centre, Tange's proposal was based on civic axis, developing the city in a linear fashion. Three levels of traffic, graded according to speed, would facilitate the movement of up to 2.5 million people along the axis, which would be divided into vertebrae-like cyclical transportation elements. The sheer size of the proposal meant that it would stretch out across the water of Tokyo Bay. Tange's proposals at this conference play a large part in establishing his reputation as "The West's favourite Japanese architect".

In 1965 Tange was asked by the United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization whose stated purposes are to maintain international peace and international security, security, develop friendly relations among nations, achieve international cooperation, and be ...

to enter a limited competition for the redevelopment of Skopje

Skopje ( , , ; mk, Скопје ; sq, Shkup) is the capital and largest city of North Macedonia. It is the country's political, cultural, economic, and academic centre.

The territory of Skopje has been inhabited since at least 4000 BC; r ...

, which was at that time a city of Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia

The Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, commonly referred to as SFR Yugoslavia or simply as Yugoslavia, was a country in Central and Southeast Europe. It emerged in 1945, following World War II, and lasted until 1992, with the breakup of Yug ...

. The town had been heavily destroyed by an earthquake in 1963. Tange won 60% of the prize; the other 40% was awarded to the Yugoslav team. Tange's design furthered ideas put forward in the earlier "Tokyo Plan".

Tange further developed his ideas for expandable urban forms in 1966 when he designed the Yamanashi Broadcasting and Press Centre in Kōfu

is the capital city of Yamanashi Prefecture, Japan. , the city had an estimated population of 187,985 in 90,924 households, and a population density of 880 persons per km2. The total area of the city is .

Overview Toponymy

Kōfu's name means "c ...

. It was designed for three media companies: a newspaper printing plant, a radio station and a television studio. To allow for future expansion Tange grouped the similar functions of three offices together in three zones. The newspaper printing machinery was on the ground floor, sealed studios on the upper floors and offices on glass walled floors surrounded by balconies. The services, including stairs and lifts, are housed in 16 reinforced concrete column A reinforced concrete column is a structural member designed to carry compressive loads, composed of concrete with an embedded steel frame to provide reinforcement. For design purposes, the columns are separated into two categories: short colum ...

s that are of five-metre (17 ft) diameter. Space was left between the cluster of functional space to allow for future expansion, although these have been used for gardens and terraces.

Urbanists and Architects Team

Tange's inspiration for his design office came from his friendWalter Gropius

Walter Adolph Georg Gropius (18 May 1883 – 5 July 1969) was a German-American architect

An architect is a person who plans, designs and oversees the construction of buildings. To practice architecture means to provide services in conne ...

who he had first met at the CIAM meeting in 1951. While lecturing at the Bauhaus

The Staatliches Bauhaus (), commonly known as the Bauhaus (), was a German art school operational from 1919 to 1933 that combined crafts and the fine arts.Oxford Dictionary of Art and Artists (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 4th edn., 200 ...

, Gropius had placed great importance on teaching architects, especially imparting on them the concept of working together as a team. The Urbanists and Architects Team was founded in 1961 and became Kenzō Tange Associates. Tange promoted a very flat hierarchy in the practice: partners were equal in importance and were encouraged to participate in every project. Multiple options were developed simultaneously, and research on individual schemes was encouraged.

Later career

During the 1970s and 1980s Tange expanded his portfolio to include buildings in over 20 countries around the world. In 1985, at the behest ofJacques Chirac

Jacques René Chirac (, , ; 29 November 193226 September 2019) was a French politician who served as President of France from 1995 to 2007. Chirac was previously Prime Minister of France from 1974 to 1976 and from 1986 to 1988, as well as Ma ...

, the mayor of Paris at that time, Tange proposed a master plan for a plaza at Place d'Italie

The Place d'Italie (; en, Italy Square) is a public space in the 13th arrondissement of Paris. The square has an average dimension somewhat less than 200 meters in extent (comprising about 30,000 m²), and the following streets meet there:

*Boule ...

that would interconnect the city along an east-west axis.

For the Tokyo Metropolitan Government Building

The , also referred to as the for short, is the seat of the Tokyo Metropolitan Government, which governs the special wards, cities, towns, and villages that constitute the Tokyo Metropolis.

Located in Shinjuku ward, the building was designed b ...

, which opened in 1991, Tange designed a large civic centre with a plaza dominated by two skyscrapers. These house the administration offices whilst a smaller seven-storey building contains assembly facilities. In his design of a high tech version of Kofu Communications Centre, Tange equipped all three buildings with state-of-the-art building management systems that monitored air quality, light levels and security. The external skin of the building makes dual references to both tradition and the modern condition. Tange incorporated vertical and horizontal lines reminiscent of both timber boarding and the lines on semiconductor boards.

Tange continued to practice until three years before his death in 2005. He disliked postmodernism

Postmodernism is an intellectual stance or Rhetorical modes, mode of discourseNuyen, A.T., 1992. The Role of Rhetorical Devices in Postmodernist Discourse. Philosophy & Rhetoric, pp.183–194. characterized by philosophical skepticism, skepticis ...

in the 1980s and considered this style of architecture to be only "transitional architectural expressions". His funeral was held in one of his works, the Tokyo Cathedral.

Legacy

Archigram

Archigram was an avant-garde architectural group formed in the 1960s that was neofuturistic, anti-heroic and pro-consumerist, drawing inspiration from technology in order to create a new reality that was solely expressed through hypothetical ...

with their plug-in mega structures. The Metabolist movement gave momentum to Kikutake's career. Although his Marine City proposals (submitted by Tange at CIAM) were not realised, his Miyakonojo City Hall (1966) was a more Metabolist example of Tange's own Nichinan Cultural Centre (1962). Although the Osaka Expo had marked a decline in the Metabolist movement, it resulted in a "handing over" of the reigns to a younger generation of architects such as Kazuo Shinohara and Arata Isozaki.

In an interview with Jeremy Melvin at the Royal Academy of Arts, Kengo Kuma

is a Japanese architect and professor in the Department of Architecture (Graduate School of Engineering) at the University of Tokyo. Frequently compared to contemporaries Shigeru Ban and Kazuyo Sejima, Kuma is also noted for his prolific writings ...

explained that, at the age of ten, he was inspired to become an architect after seeing Tange's Olympic arenas, which were constructed in 1964.

For Reyner Banham

Peter Reyner Banham Hon. FRIBA (2 March 1922 – 19 March 1988) was an English architectural critic and writer best known for his theoretical treatise ''Theory and Design in the First Machine Age'' (1960) and for his 1971 book ''Los Angeles: Th ...

, Tange was a prime exemplar of the use of Brutalist architecture

Brutalist architecture is an architectural style that emerged during the 1950s in the United Kingdom, among the reconstruction projects of the post-war era. Brutalist buildings are characterised by minimalist constructions that showcase the ba ...

. His use of Béton brut concrete finishes in a raw and undecorated way combined with his civic projects such as the redevelopment of Tokyo Bay made him a great influence on British architects during the 1960s. Brutalist architecture has been criticised for being soulless and for promoting the exclusive use of a material that is poor at withstanding long exposures to natural weather.

He received the AIA Gold Medal

The AIA Gold Medal is awarded by the American Institute of Architects conferred "by the national AIA Board of Directors in recognition of a significant body of work of lasting influence on the theory and practice of architecture."

It is the Ins ...

in 1966.

Tange's son Paul Noritaka Tange graduated from Harvard University in 1985 and went on to join Kenzō Tange Associates. He became the president of Kenzo Tange Associates in 1997 before founding Tange Associates in 2002.

Awards

*RIBA

The Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) is a professional body for architects primarily in the United Kingdom, but also internationally, founded for the advancement of architecture under its royal charter granted in 1837, three suppl ...

Gold Medal (1965)

* American Institute of Architects

The American Institute of Architects (AIA) is a professional organization for architects in the United States. Headquartered in Washington, D.C., the AIA offers education, government advocacy, community redevelopment, and public outreach to su ...

Gold Medal (1966)

* French Academy of Architecture Grand Medal of Gold (1973)

* Pritzker Architecture Prize

The Pritzker Architecture Prize is an international architecture award presented annually "to honor a living architect or architects whose built work demonstrates a combination of those qualities of talent, vision and commitment, which has produ ...

(1987)Sam Hall KaplanTange's Honor Is Well-Deserved

''Los Angeles Times'' (22 March 1987). *

Olympic Diploma of Merit

The Olympic Diploma of Merit was an award given by the International Olympic Committee (IOC) to recognise outstanding services to sports or a notable contribution to the Olympic Games. By 1974, the last time the awards were granted, just 58 peop ...

(1965)

Footnotes

References

* * * * * * * * *External links

Tange Associates official website

Gift of Mrs. Takako Tange, 2011. Frances Loeb Library, Harvard University Graduate School of Design. {{DEFAULTSORT:Tange, Kenzo 1913 births 2005 deaths Japanese architects Pritzker Architecture Prize winners Recipients of the Order of the Sacred Treasure, 1st class Recipients of the Pour le Mérite (civil class) Recipients of the Praemium Imperiale Recipients of the Royal Gold Medal Recipients of the Order of Culture Recipients of the Legion of Honour People from Sakai, Osaka University of Tokyo alumni Nihon University alumni Expo '70 Japanese Roman Catholics Recipients of the AIA Gold Medal