Kazimierz Pulaski on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Kazimierz Michał Władysław Wiktor Pułaski of the Ślepowron coat of arms (; ''Casimir Pulaski'' ; March 4 or March 6, 1745 Makarewicz, 1998 October 11, 1779) was a Polish

In 1769, Pulaski's unit was again besieged by numerically superior forces, this time in the old fortress of Okopy Świętej Trójcy, which had served as his base of operations since December the previous year. However, after a staunch defence, he was able to break the Russian siege. On April 7, he was made the '' regimentarz'' of the Kraków Voivodeship. In May and June he operated near

In 1769, Pulaski's unit was again besieged by numerically superior forces, this time in the old fortress of Okopy Świętej Trójcy, which had served as his base of operations since December the previous year. However, after a staunch defence, he was able to break the Russian siege. On April 7, he was made the '' regimentarz'' of the Kraków Voivodeship. In May and June he operated near  In February 1771, Pulaski operated around

In February 1771, Pulaski operated around  In May 1771, Pulaski advanced on Zamość, refusing to coordinate an operation with Dumouriez against

In May 1771, Pulaski advanced on Zamość, refusing to coordinate an operation with Dumouriez against

On August 20, he met Washington in his headquarters in Neshaminy Falls, outside

On August 20, he met Washington in his headquarters in Neshaminy Falls, outside

Although Pulaski frequently suffered from

Although Pulaski frequently suffered from

The United States has long commemorated Pulaski's contributions to the American Revolutionary War, and already on October 29, 1779, the

The United States has long commemorated Pulaski's contributions to the American Revolutionary War, and already on October 29, 1779, the  In Poland, in 1793 Pulaski's relative, Antoni Pułaski, obtained a cancellation of his brother's sentence from 1773. He has been mentioned in the literary works of numerous Polish authors, including

In Poland, in 1793 Pulaski's relative, Antoni Pułaski, obtained a cancellation of his brother's sentence from 1773. He has been mentioned in the literary works of numerous Polish authors, including

This page links directly to numerous short entries, many accompanied by photographs, discussing a variety of monuments, memorials, etc., in the squares and elsewhere. Accessed June 16, 2007. The The villages of Mt. Pulaski, Illinois,

The villages of Mt. Pulaski, Illinois,

•

•

Url

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * Proclaiming Casimir Pulaski to be an honorary citizen of the United States. * * * * * Presidential Studies Quarterly Vol. XXIV No. 4 Fall 1994, pp. 876–77 * * * * *

Url

* *

Url

*

Url

* * Shepherd, Joshua,

Soldiers: Casimir Pulaski

'' Warfare History Network, February 13, 2019 *

* ttp://www.newadvent.org/cathen/12561a.htm Biography from ''Catholic Encyclopedia''

Casimir Pulaski Day

the Office of Civil Rights and Diversity at

Casimir Pulaski Foundation

{{DEFAULTSORT:Pulaski, Casimir 1745 births 1779 deaths Bar confederates Burials in Georgia (U.S. state) Continental Army officers from Poland Intersex men Intersex military personnel Intersex people and military service in the United States Military personnel from Warsaw Nobility from Warsaw People sentenced to death in absentia Polish emigrants to the United States Polish generals in other armies Polish Roman Catholics

nobleman

Nobility is a social class found in many societies that have an aristocracy. It is normally ranked immediately below royalty. Nobility has often been an estate of the realm with many exclusive functions and characteristics. The characteris ...

, soldier, and military commander who has been called, together with his counterpart Michael Kovats de Fabriczy

Michael Kovats de Fabriczy (often simply Michael Kovats; hu, Kováts Mihály; 1724 – May 11, 1779) was a Hungarian nobleman and cavalry officer who served in the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War, in which he was killed in ...

, "the father of the American cavalry."

Born in Warsaw

Warsaw ( pl, Warszawa, ), officially the Capital City of Warsaw,, abbreviation: ''m.st. Warszawa'' is the capital and largest city of Poland. The metropolis stands on the River Vistula in east-central Poland, and its population is official ...

and following in his father's footsteps, he became interested in politics at an early age. He soon became involved in the military and in revolutionary affairs in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, formally known as the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, and, after 1791, as the Commonwealth of Poland, was a bi-confederal state, sometimes called a federation, of Poland and Lithuania rul ...

. Pulaski was one of the leading military commanders for the Bar Confederation

The Bar Confederation ( pl, Konfederacja barska; 1768–1772) was an association of Polish nobles (szlachta) formed at the fortress of Bar in Podolia (now part of Ukraine) in 1768 to defend the internal and external independence of the Polis ...

and fought against the Commonwealth's foreign domination. When this uprising failed, he was driven into exile. Following a recommendation by Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin ( April 17, 1790) was an American polymath who was active as a writer, scientist, inventor, statesman, diplomat, printer, publisher, and political philosopher. Encyclopædia Britannica, Wood, 2021 Among the leading inte ...

, Pulaski traveled to North America to help in the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

. He distinguished himself throughout the revolution, most notably when he saved the life of George Washington

George Washington (February 22, 1732, 1799) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first president of the United States from 1789 to 1797. Appointed by the Continental Congress as commander of t ...

. Pulaski became a general

A general officer is an officer of high rank in the armies, and in some nations' air forces, space forces, and marines or naval infantry.

In some usages the term "general officer" refers to a rank above colonel."general, adj. and n.". O ...

in the Continental Army

The Continental Army was the army of the United Colonies (the Thirteen Colonies) in the Revolutionary-era United States. It was formed by the Second Continental Congress after the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War, and was establ ...

, and he and his friend, Michael Kovats, created the Pulaski Cavalry Legion and reformed the American cavalry as a whole. At the Battle of Savannah, while leading a cavalry charge against British forces, he was fatally wounded by grapeshot

Grapeshot is a type of artillery round invented by a British Officer during the Napoleonic Wars. It was used mainly as an anti infantry round, but had other uses in naval combat.

In artillery, a grapeshot is a type of ammunition that consists of ...

and died shortly after.

Pulaski is remembered as a hero who fought for independence and freedom in Poland and the United States. Numerous places and events are named in his honor, and he is commemorated by many works of art. Pulaski is one of only eight people to be awarded honorary United States citizenship. Analyses since the 1990s of Pulaski's presumed remains have raised the possibility that Pulaski was intersex

Intersex people are individuals born with any of several sex characteristics including chromosome patterns, gonads, or genitals that, according to the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, "do not fit typical b ...

.

Personal life

Pulaski was born on March 6, 1745, in themanor house

A manor house was historically the main residence of the lord of the manor. The house formed the administrative centre of a manor in the European feudal system; within its great hall were held the lord's manorial courts, communal meals wi ...

of the Pułaski family in Warsaw

Warsaw ( pl, Warszawa, ), officially the Capital City of Warsaw,, abbreviation: ''m.st. Warszawa'' is the capital and largest city of Poland. The metropolis stands on the River Vistula in east-central Poland, and its population is official ...

, Poland. Poles in America Foundation, 2012 Casimir was the second eldest son of Marianna Zielińska and Józef Pułaski, who was an ''advocatus

During the Middle Ages, an (sometimes given as modern English: advocate; German: ; French: ) was an office-holder who was legally delegated to perform some of the secular responsibilities of a major feudal lord, or for an institution such as ...

'' at the Crown Tribunal

The Crown Tribunal ( pl, Trybunał Główny Koronny, la, Iudicium Ordinarium Generale Tribunalis Regni) was the highest appellate court in the Crown of the Kingdom of Poland for most cases. Exceptions were if a noble landowner was threatened with ...

, the Starost

The starosta or starost ( Cyrillic: ''старост/а'', Latin: ''capitaneus'', german: link=no, Starost, Hauptmann) is a term of Slavic origin denoting a community elder whose role was to administer the assets of a clan or family estates. T ...

of Warka, and one of the town's most notable inhabitants. He was a brother of Franciszek Ksawery Pułaski and Antoni Pułaski. His family bore the Ślepowron coat of arms. Szczygielski, 1986, p. 386 The Pułaski family was Roman Catholic

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

* Rome, the capital city of Italy

* Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

* Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*''Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a let ...

and early in his youth, Casimir Pulaski attended an elite college run by Theatines

The Theatines officially named the Congregation of Clerics Regular ( la, Ordo Clericorum Regularium), abreviated CR, is a Catholic order of clerics regular of Pontifical Right for men founded by Archbishop Gian Pietro Carafa in Sept. 14, 1524. I ...

, a male religious order of the Catholic Church in Warsaw, but did not finish his education.

There is some circumstantial evidence that Pulaski was a Freemason

Freemasonry or Masonry refers to fraternal organisations that trace their origins to the local guilds of stonemasons that, from the end of the 13th century, regulated the qualifications of stonemasons and their interaction with authorities ...

. When Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette

Marie-Joseph Paul Yves Roch Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de La Fayette (6 September 1757 – 20 May 1834), known in the United States as Lafayette (, ), was a French aristocrat, freemason and military officer who fought in the American Revolutio ...

laid the cornerstone of the monument erected in Pulaski's honour in Monterey Square in Savannah in 1824, a full Masonic ceremony took place with Richard T. Turner, High Priest of the Georgia chapter, conducting the service. Other sources claim Pulaski was a member of the Masonic Army Lodge in Maryland. A Masonic Lodge in Chicago is named ''Casimir Pulaski Lodge, No.1167'', and a brochure issued by the lodge claims he obtained the degree of Master Mason on June 19, 1779, and was buried with full Masonic honours. To date, no surviving documents of Pulaski's actual membership have been found.

Military career

In 1762, Pulaski started his military career as a page of Carl Christian Joseph of Saxony, Duke of Courland and the Polish king's vassal. He spent six months at the ducal court inMitau

Jelgava (; german: Mitau, ; see also other names) is a state city in central Latvia about southwest of Riga with 55,972 inhabitants (2019). It is the largest town in the region of Zemgale (Semigalia). Jelgava was the capital of the united Duc ...

, during which the court was interned in the palaces by the Russian forces occupying the area. He then returned to Warsaw, and his father gave him the village of Zezulińce in Podole; from that time, Pulaski used the title of Starost of Zezulińce.

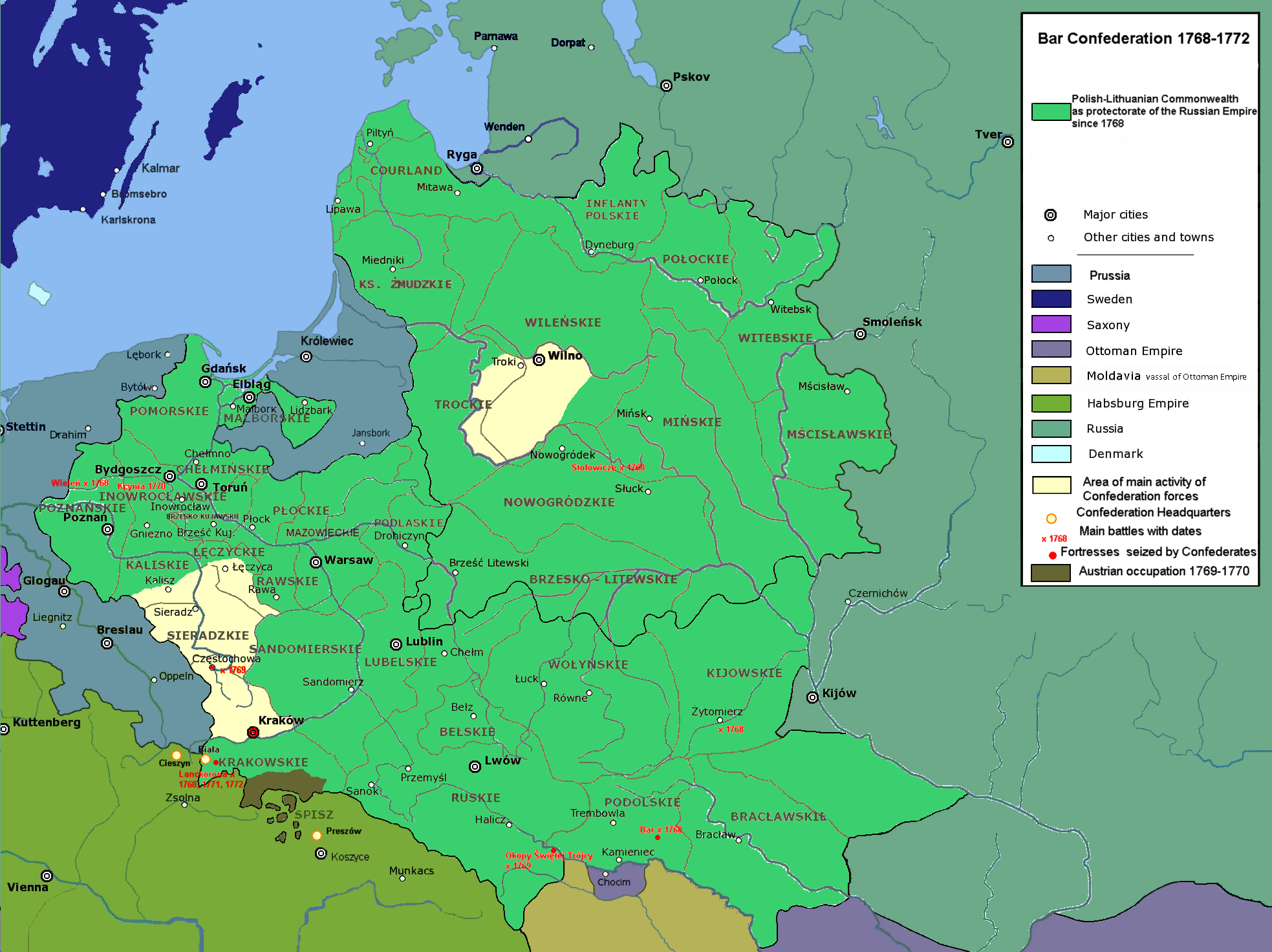

Bar Confederation

He took part in the 1764 election of the new Polish monarch,Stanisław II Augustus Stanislav and variants may refer to:

People

*Stanislav (given name), a Slavic given name with many spelling variations (Stanislaus, Stanislas, Stanisław, etc.)

Places

* Stanislav, a coastal village in Kherson, Ukraine

* Stanislaus County, Cali ...

, with his family. In December 1767, Pulaski and his father became involved with the Bar Confederation

The Bar Confederation ( pl, Konfederacja barska; 1768–1772) was an association of Polish nobles (szlachta) formed at the fortress of Bar in Podolia (now part of Ukraine) in 1768 to defend the internal and external independence of the Polis ...

, which saw King Stanisław as a Russian puppet and sought to curtail Russian hegemony

Hegemony (, , ) is the political, economic, and military predominance of one state over other states. In Ancient Greece (8th BC – AD 6th ), hegemony denoted the politico-military dominance of the ''hegemon'' city-state over other city-states. ...

over the Commonwealth

A commonwealth is a traditional English term for a political community founded for the common good. Historically, it has been synonymous with " republic". The noun "commonwealth", meaning "public welfare, general good or advantage", dates from th ...

. The confederation was actively opposed by the Russian forces stationed in Poland. Pulaski recruited a unit and, on February 29, 1768, signed the act of the confederation, thus declaring himself an official supporter of the movement. On March 6, he received a '' pułkownik'' (colonel) rank and commanded a ''chorągiew'' of cavalry

Historically, cavalry (from the French word ''cavalerie'', itself derived from "cheval" meaning "horse") are soldiers or warriors who fight mounted on horseback. Cavalry were the most mobile of the combat arms, operating as light cavalry in ...

. In March and April, Pulaski agitated among the Polish military, successfully convincing some forces to join the Confederates. He fought his first battle on April 20 near Pohorełe; it was a victory, as was another on April 23 near Starokostiantyniv

Starokostiantyniv ( uk, Старокостянтинів; pl, Starokonstantynów, or ''Konstantynów''; yi, אלט-קאָנסטאַנטין ''Alt Konstantin'') is a city in Khmelnytskyi Raion, Khmelnytskyi Oblast (province) of western Ukraine. I ...

. An engagement at Kaczanówka on April 28 resulted in a defeat. In early May, he garrisoned Chmielnik but was forced to retreat when allied reinforcements were defeated. He retreated to a monastery in Berdyczów, which he defended during a siege by royalist forces for over two weeks until June 16. Eventually, he was forced to surrender and was taken captive by the Russians. On June 28, he was released in exchange for a pledge that he would not again take up arms with the Confederates, and that he would lobby the Confederates to end hostilities. However, Pulaski considered the assurance to be non-binding and made a public declaration to that effect upon reaching a camp of the Confederates at the end of July. Agreeing to the pledge in the first place weakened his authority and popularity among the Confederates, and his own father considered whether or not he should be Court-martial

A court-martial or court martial (plural ''courts-martial'' or ''courts martial'', as "martial" is a postpositive adjective) is a military court or a trial conducted in such a court. A court-martial is empowered to determine the guilt of mem ...

ed; some heated debates followed, and Pulaski was reinstated to active-duty only in early September. Szczygielski 1986, p. 387

Przemyśl

Przemyśl (; yi, פשעמישל, Pshemishl; uk, Перемишль, Peremyshl; german: Premissel) is a city in southeastern Poland with 58,721 inhabitants, as of December 2021. In 1999, it became part of the Subcarpathian Voivodeship; it was pr ...

, but failed to take the town. Criticized by some of his fellow Confederates, Pulaski departed to Lithuania

Lithuania (; lt, Lietuva ), officially the Republic of Lithuania ( lt, Lietuvos Respublika, links=no ), is a country in the Baltic region of Europe. It is one of three Baltic states and lies on the eastern shore of the Baltic Sea. Lithuania ...

with his allies and a force of about 600 men on June 3. There, Pulaski attempted to incite a larger revolt against Russia; despite no decisive military successes, he was able to assemble a 4,000-strong army and deliver it back to a Confederate staging point. This excursion received international notice and gained him a reputation as the most effective military leader in the Bar Confederation. Next, he moved with his unit towards Zamość

Zamość (; yi, זאמאשטש, Zamoshtsh; la, Zamoscia) is a historical city in southeastern Poland. It is situated in the southern part of Lublin Voivodeship, about from Lublin, from Warsaw. In 2021, the population of Zamość was 62,021. ...

and — after nearly losing his life to the inferior forces of the future Generalissimo Alexander Suvorov

Alexander Vasilyevich Suvorov (russian: Алекса́ндр Васи́льевич Суво́ров, Aleksándr Vasíl'yevich Suvórov; or 1730) was a Russian general in service of the Russian Empire. He was Count of Rymnik, Count of the Holy ...

in the disastrous Battle of Orekhowa — on the very next day, September 15, he was again defeated at the Battle of Włodawa with his forces almost completely dispelled. He spent the rest of the year rebuilding his unit in the region of Podkarpacie. Szczygielski 1986, p. 388

In February 1770, Pulaski moved near Nowy Targ, and in March, helped to subdue the mutiny of Józef Bierzyński. Based in Izby, he subsequently operated in southern Lesser Poland

Lesser Poland, often known by its Polish name Małopolska ( la, Polonia Minor), is a historical region situated in southern and south-eastern Poland. Its capital and largest city is Kraków. Throughout centuries, Lesser Poland developed a s ...

and on May 13 his force was defeated at the Battle of Dęborzyn. Around June 9–10 in Prešov

Prešov (, hu, Eperjes, Rusyn and Ukrainian: Пряшів) is a city in Eastern Slovakia. It is the seat of administrative Prešov Region ( sk, Prešovský kraj) and Šariš, as well as the historic Sáros County of the Kingdom of Hungary. Wit ...

, in a conference with other Confederate leaders, he met Joseph II, Holy Roman Emperor

Joseph II (German: Josef Benedikt Anton Michael Adam; English: ''Joseph Benedict Anthony Michael Adam''; 13 March 1741 – 20 February 1790) was Holy Roman Emperor from August 1765 and sole ruler of the Habsburg lands from November 29, 1780 un ...

, who complimented Pulaski on his actions. On July 3–4, Pulaski's camp was captured by Johann von Drewitz, and he was forced to retreat into Austria. Early in August he met with the French emissary, Charles François Dumouriez. He disregarded an order to take Lanckorona

Lanckorona is a village located south-west of Kraków in Lesser Poland. It lies on the Skawinka river, among the hills of the Beskids, above sea level. It is known for the Lanckorona Castle, today in ruins. Lanckorona is also known for the ...

and instead cooperated with Michał Walewski in a raid on Kraków

Kraków (), or Cracow, is the second-largest and one of the oldest cities in Poland. Situated on the Vistula River in Lesser Poland Voivodeship, the city dates back to the seventh century. Kraków was the official capital of Poland until 1596 ...

on the night of August 31. Szczygielski, 1986, p. 389 He then departed for Częstochowa

Częstochowa ( , ; german: Tschenstochau, Czenstochau; la, Czanstochova) is a city in southern Poland on the Warta River with 214,342 inhabitants, making it the thirteenth-largest city in Poland. It is situated in the Silesian Voivodeship (adm ...

. On September 10, along with Walewski, he used subterfuge to take control of the Jasna Góra monastery

The Jasna Góra Monastery ( pl, Jasna Góra , ''Luminous Mount'', hu, Fényes Hegy, lat, Clarus Mons) in Częstochowa, Poland, is a shrine dedicated to the Virgin Mary and one of the country's places of pilgrimage. The image of the Black Mado ...

. On September 18 he met Franciszka z Krasińskich, an aristocrat from the Krasiński family and the wife of Charles of Saxony, Duke of Courland; he impressed her and she would become one of his protectors. Around September 22–24 Walewski was made the commandant of Jasna Góra, which slighted Pulaski. Nonetheless he continued as the ''de facto'' commander of Confederate troops stationed in and around Jasna Góra. Between September 10, 1770, and January 14, 1771, Pulaski, Walewski and Józef Zaremba commanded the Polish forces during the siege of Jasna Góra monastery. They successfully defended against Drewitz in a series of engagements, the largest one on November 11, followed by a siege from December 31 to January 14. The defense of Jasna Góra further enhanced his reputation among the Confederates and abroad. A popular Confederate song taunting Drewitz included lyrics about Pulaski and Jasna Góra. Maciejewski, 1976, p. 381 Pulaski intended to pursue Drewitz, but a growing discord between him and Zaremba prevented this from becoming a real option.

Lublin

Lublin is the ninth-largest city in Poland and the second-largest city of historical Lesser Poland. It is the capital and the center of Lublin Voivodeship with a population of 336,339 (December 2021). Lublin is the largest Polish city east of ...

; on February 25 he was victorious at Tarłów and on the night of February 28 and March 1, his forces besieged Kraśnik

Kraśnik is a town in southeastern Poland with 35,602 inhabitants (2012), situated in the Lublin Voivodeship, historic Lesser Poland. It is the seat of Kraśnik County. The town of Kraśnik as it is known today was created in 1975, after the me ...

. In March that year he became one of the members of the Confederates' War Council. Dumouriez, who became a military adviser to the Confederates, at the time described him as "spontaneous, more proud than ambitious, friend of the prince of Courland, enemy of the Potocki family

The House of Potocki (; plural: Potoccy, male: Potocki, feminine: Potocka) was a prominent Polish noble family in the Kingdom of Poland and magnates of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. The Potocki family is one of the wealthiest an ...

, brave and honest" as well as popular among other commanders. This was due to his refusal to follow orders and adhere to discipline. Jędrzej Kitowicz who met him as well around that time described him as short and thin, pacing and speaking quickly, and uninterested in women or drinking. Furthermore, he enjoyed fighting against the Russians above everything else, and was daring to the extent he forgot about his safety in battles, resulting in his many failures on the battlefield.

Alexander Suvorov

Alexander Vasilyevich Suvorov (russian: Алекса́ндр Васи́льевич Суво́ров, Aleksándr Vasíl'yevich Suvórov; or 1730) was a Russian general in service of the Russian Empire. He was Count of Rymnik, Count of the Holy ...

; without Pulaski's support, the Confederates were defeated at the Battle of Lanckorona

Two of the main battles of the Bar Confederation took place on the plains before Lanckorona, a small settlement 27km (17 mi) southwest of the Polish capital Kraków.

First Battle

On 22 February 1769, the Bar Confederates defended Lanckorona a ...

. Pulaski's forces were victorious at the Battle of Majdany, and briefly besieged Zamość, but it was relieved by Suvorov. He retreated, suffering major losses, towards Częstochowa. On July 27, pressured by Franciszka z Krasińskich, he declared he would from then on strictly adhere to orders from the Confederacy that he had previously habitually disregarded. In October his responsibilities in the War Council were increased, and the same month he became involved with the plan to kidnap king Poniatowski. Pulaski was initially opposed to this plan but later supported it on the condition that the king would not be harmed. Storozynski, 2010, p. 23 The attempt failed, weakening the international reputation of the Confederates, and when Pulaski's involvement with the attempted kidnapping became known, the Austrians expelled him from their territories. Stone, 2001, p. 272 He spent the following winter and spring in Częstochowa, during which time several of his followers were defeated, captured or killed. Szczygielski, 1986, p. 390

On May 31, 1772, Pulaski, increasingly distanced from other leaders of the Confederation, left the Jasna Góra monastery and went to Silesia

Silesia (, also , ) is a historical region of Central Europe that lies mostly within Poland, with small parts in the Czech Republic and Germany. Its area is approximately , and the population is estimated at around 8,000,000. Silesia is split ...

in Prussia. In the meantime, the Bar Confederation was defeated, with most fighting ending around the summer. Overall, Pulaski was seen as one of the most famous and accomplished Confederate leaders. At the same time, he often acted independently, disobeying orders from Confederate command, and among his detractors (which included Dumouriez) had a reputation of a "loose cannon". The First Partition of Poland occurred in 1772.

Leaving Prussia, Pulaski sought refuge in France, where he unsuccessfully attempted to join the French Army

The French Army, officially known as the Land Army (french: Armée de Terre, ), is the land-based and largest component of the French Armed Forces. It is responsible to the Government of France, along with the other components of the Armed Forc ...

. In 1773, his opponents in Poland accused him of attempted regicide

Regicide is the purposeful killing of a monarch or sovereign of a polity and is often associated with the usurpation of power. A regicide can also be the person responsible for the killing. The word comes from the Latin roots of ''regis ...

, and proceedings began at the Sejm Court on June 7. Szczygielski, 1986, p. 391 The Partition Sejm had been convened by the victors to validate the First Partition.

Poniatowski himself warned Pulaski to stay away from Poland, or risk death. The court verdict, declared '' in absentia'' in July, stripped Pulaski of "all dignity and honors", demanded that his possessions be confiscated, and sentenced him to death. He attempted to recreate a Confederate force in the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

during the Russo-Turkish War, but before he could make any progress, the Turks were defeated, and he barely escaped by sea to Marseille

Marseille ( , , ; also spelled in English as Marseilles; oc, Marselha ) is the prefecture of the French department of Bouches-du-Rhône and capital of the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region. Situated in the camargue region of southern Fran ...

, France. He found himself in debt and unable to find an army that would enlist him. He spent the year of 1775 in France, imprisoned at times for debts, until his allies gathered enough funds to arrange for his release. Around that time, due to the efforts of his friend Claude-Carloman de Rulhière, he was recruited by the Marquis de Lafayette

Marie-Joseph Paul Yves Roch Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de La Fayette (6 September 1757 – 20 May 1834), known in the United States as Lafayette (, ), was a French aristocrat, freemason and military officer who fought in the American Revolutio ...

and Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin ( April 17, 1790) was an American polymath who was active as a writer, scientist, inventor, statesman, diplomat, printer, publisher, and political philosopher. Encyclopædia Britannica, Wood, 2021 Among the leading inte ...

(whom he met in spring 1777) for service in the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

.

In the United States

Northern front

Franklin was impressed by Pulaski, and wrote of him: "Count Pulaski of Poland, an officer famous throughout Europe for his bravery and conduct in defence of the liberties of his country against the three great invading powers of Russia, Austria and Prussia ... may be highly useful to our service." Storozynski, 2010, p. 56 He subsequently recommended that GeneralGeorge Washington

George Washington (February 22, 1732, 1799) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first president of the United States from 1789 to 1797. Appointed by the Continental Congress as commander of t ...

accept Pulaski as a volunteer in the Continental Army cavalry and said that Pulaski "was renowned throughout Europe for the courage and bravery he displayed in defense of his country's freedom." U.S. Government Printing Office Pulaski departed France from Nantes

Nantes (, , ; Gallo: or ; ) is a city in Loire-Atlantique on the Loire, from the Atlantic coast. The city is the sixth largest in France, with a population of 314,138 in Nantes proper and a metropolitan area of nearly 1 million inhabit ...

in June, and arrived in Marblehead, Massachusetts

Marblehead is a coastal New England town in Essex County, Massachusetts, along the North Shore. Its population was 20,441 at the 2020 census. The town lies on a small peninsula that extends into the northern part of Massachusetts Bay. Attach ...

, near Boston

Boston (), officially the City of Boston, is the state capital and most populous city of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as well as the cultural and financial center of the New England region of the United States. It is the 24th- m ...

, on July 23, 1777. Szczygielski, 1986, p. 392 After his arrival, Pulaski wrote to Washington, "I came here, where freedom is being defended, to serve it, and to live or die for it."

Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Sin ...

. He showed off riding stunts, and argued for the superiority of cavalry over infantry. Because Washington was unable to grant him an officer rank, Pulaski spent the next few months traveling between Washington and the United States Congress

The United States Congress is the legislature of the federal government of the United States. It is bicameral, composed of a lower body, the House of Representatives, and an upper body, the Senate. It meets in the U.S. Capitol in Washi ...

in Philadelphia, awaiting his appointment. His first military engagement against the British occurred before he received it, on September 11, 1777, at the Battle of Brandywine

The Battle of Brandywine, also known as the Battle of Brandywine Creek, was fought between the American Continental Army of General George Washington and the British Army of General Sir William Howe on September 11, 1777, as part of the A ...

. When the Continental Army

The Continental Army was the army of the United Colonies (the Thirteen Colonies) in the Revolutionary-era United States. It was formed by the Second Continental Congress after the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War, and was establ ...

troops began to yield, he reconnoitered with Washington's bodyguard of about 30 men, and reported that the enemy were endeavoring to cut off the line of retreat. Washington ordered him to collect as many as possible of the scattered troops who came his way and employ them according to his discretion to secure the retreat of the army. Appletons Cyclopaedia of American Biography: Pickering-Sumter, 1898, p. 133 His subsequent charge averted a disastrous defeat of the Continental Army cavalry, Kazimierz Pulaski Granted U.S. Citizenship Posthumously, 2009 earning him fame in America and saving the life of George Washington. As a result, on September 15, 1777, on the orders of Congress, Washington commissioned Pulaski a brigadier general

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointed ...

in the Continental Army cavalry. At that point, the cavalry was only a few hundred men strong organized into four regiments. These men were scattered among numerous infantry formations, and used primarily for scouting duties. Pulaski immediately began work on reforming the cavalry, and wrote the first regulations for the formation.

On September 16, while on patrol west of Philadelphia, Pulaski spotted significant British forces moving toward the Continental position. Upon being informed by Pulaski, Washington prepared for a battle, but the encounter was interrupted by a major storm before either side was organized. Sokol, 1992, pp. 31–36 McGuire, 2006, pp.31–36 On October 4, Pulaski took part in the Battle of Germantown

The Battle of Germantown was a major engagement in the Philadelphia campaign of the American Revolutionary War. It was fought on October 4, 1777, at Germantown, Pennsylvania, between the British Army led by Sir William Howe, and the American Co ...

. He spent the winter of 1777 to 1778 with most of the army at Valley Forge

Valley Forge functioned as the third of eight winter encampments for the Continental Army's main body, commanded by General officer, General George Washington, during the American Revolutionary War. In September 1777, Congress fled Philadelphi ...

. Pulaski argued that the military operations should continue through the winter, but this idea was rejected by the general staff. In turn, he directed his efforts towards reorganizing the cavalry force, mostly stationed in Trenton. While at Trenton his assistance was requested by General Anthony Wayne

Anthony Wayne (January 1, 1745 – December 15, 1796) was an American soldier, officer, statesman, and one of the Founding Fathers of the United States. He adopted a military career at the outset of the American Revolutionary War, where his mil ...

, whom Washington had dispatched on a foraging expedition into southern New Jersey. Wayne was in danger of encountering a much larger British force sent to oppose his movements. Pulaski and 50 cavalry rode south to Burlington, where they skirmished with British sentries on February 28. After this minor encounter the British commander, Lieutenant Colonel Thomas Stirling, was apparently convinced that he was facing a much larger force than expected, and prepared to withdraw his troops across the Delaware River into Pennsylvania at Cooper's Ferry (present-day Gloucester City). Pulaski and Wayne joined forces to attack Stirling's position on February 29 while he awaited suitable weather conditions to cross. In the resulting skirmish (which only involved a few hundred men out of the larger forces on either side), Pulaski's horse was shot out from under him and a few of his cavalry were wounded. Griffin, 1907, pp. 50–54

American officers serving under Pulaski had difficulty taking orders from a foreigner who could scarcely speak English and whose ideas of discipline and tactics differed enormously from those to which they were accustomed. This resulted in friction between the Americans and Pulaski and his fellow Polish officers. Kajencki, 2005, p. 47 There was also discontent in the unit over delays in pay, and Pulaski's imperious personality was a regular source of discontent among his peers, superiors, and subordinates. Pulaski was also unhappy that his suggestion to create a lancer

A lancer was a type of cavalryman who fought with a lance. Lances were used for mounted warfare in Assyria as early as and subsequently by Persia, India, Egypt, China, Greece, and Rome. The weapon was widely used throughout Eurasia during the M ...

unit was denied. Despite a commendation from Wayne, these circumstances prompted Pulaski to resign his general command in March 1778, and return to Valley Forge.

Pulaski went to Yorktown, where he met with General Horatio Gates

Horatio Lloyd Gates (July 26, 1727April 10, 1806) was a British-born American army officer who served as a general in the Continental Army during the early years of the Revolutionary War. He took credit for the American victory in the Battle ...

and suggested the creation of a new unit. At Gates' recommendation, Congress confirmed his previous appointment to the rank of a brigadier general, with a special title of "Commander of the Horse", and authorized the formation of a corps of 68 lancers and 200 light infantry. This corps, which became known as the Pulaski Cavalry Legion, was recruited mainly in Baltimore

Baltimore ( , locally: or ) is the most populous city in the U.S. state of Maryland, fourth most populous city in the Mid-Atlantic, and the 30th most populous city in the United States with a population of 585,708 in 2020. Baltimore was ...

, where it was headquartered. Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (February 27, 1807 – March 24, 1882) was an American poet and educator. His original works include " Paul Revere's Ride", '' The Song of Hiawatha'', and '' Evangeline''. He was the first American to completely tra ...

would later commemorate in verse the consecration of the Legion's banner. By August 1778, it numbered about 330 men, both Americans and foreigners. British major general Charles Lee commented on the high standards of the Legion's training. The "father of the American cavalry" demanded much of his men and trained them in tested cavalry tactics. He used his own personal finances when money from Congress was scarce, in order to assure his forces of the finest equipment and personal safety. However, later that year a controversy arose related to the Legion's finances, and its requisitions from the local populace. His troubles with the auditors continued until his death; Pulaski complained that he received inadequate funds, was obstructed by locals and officials, and was forced to spend his own money. He was not cleared of these charges until after his death.

In the autumn Pulaski was ordered to Little Egg Harbor

Little Egg Harbor is a brackish bay along the coast of southeast New Jersey. It was originally called Egg Harbor by the Dutch sailors because of the eggs found in nearby gull nests.

The bay is part of the Intracoastal Waterway

The Intraco ...

on the coast of southeast New Jersey

New Jersey is a U.S. state, state in the Mid-Atlantic States, Mid-Atlantic and Northeastern United States, Northeastern regions of the United States. It is bordered on the north and east by the state of New York (state), New York; on the ea ...

, where in the engagement on October 15, known as the Affair at Little Egg Harbor, the legion suffered heavy losses. Stryker, 1894, p. 16 During the following winter Pulaski was stationed at Minisink, at that time in northwestern New Jersey. Ordered to take part in the punitive Sullivan Expedition

The 1779 Sullivan Expedition (also known as the Sullivan-Clinton Expedition, the Sullivan Campaign, and the Sullivan-Clinton Genocide) was a United States military campaign during the American Revolutionary War, lasting from June to October 177 ...

against the Iroquois

The Iroquois ( or ), officially the Haudenosaunee ( meaning "people of the longhouse"), are an Iroquoian Peoples, Iroquoian-speaking Confederation#Indigenous confederations in North America, confederacy of First Nations in Canada, First Natio ...

, he was dissatisfied with this command, and intended to leave the service and return to Europe, but instead asked to be reassigned to the Southern front. On February 2, 1779, Washington instead ordered him to South Carolina

)'' Animis opibusque parati'' ( for, , Latin, Prepared in mind and resources, links=no)

, anthem = " Carolina";" South Carolina On My Mind"

, Former = Province of South Carolina

, seat = Columbia

, LargestCity = Charleston

, LargestMetro = ...

.

Southern front

Pulaski arrived in Charleston on May 8, 1779, finding the city in crisis. Wilson, 2005, pp. 107–108 GeneralBenjamin Lincoln

Benjamin Lincoln (January 24, 1733 ( O.S. January 13, 1733) – May 9, 1810) was an American army officer. He served as a major general in the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War. Lincoln was involved in three major surrenders ...

, commander of the southern army, had led most of the army toward Augusta, Georgia

Augusta ( ), officially Augusta–Richmond County, is a consolidated city-county on the central eastern border of the U.S. state of Georgia. The city lies across the Savannah River from South Carolina at the head of its navigable portion. Georgi ...

, in a bid to recapture Savannah

A savanna or savannah is a mixed woodland- grassland (i.e. grassy woodland) ecosystem characterised by the trees being sufficiently widely spaced so that the canopy does not close. The open canopy allows sufficient light to reach the ground ...

, which had been captured by the British in late 1778. Wilson, 2005, pp. 101–102 The British commander, Brigadier General Augustine Prevost, responded to Lincoln's move by launching a raiding expedition from Savannah across the Savannah River

The Savannah River is a major river in the southeastern United States, forming most of the border between the states of South Carolina and Georgia. Two tributaries of the Savannah, the Tugaloo River and the Chattooga River, form the nort ...

. Wilson, 2005, p. 103 The South Carolina militia fell back before the British advance, and Prevost's force followed them all the way to Charleston. Pulaski arrived just as military leaders were establishing the city's defenses. Russell, 2000, p. 106 When the British advanced on May 11, Pulaski's Legion engaged forward elements of the British force, and was badly mauled in the encounter. The Legion infantry, numbering only about 60 men before the skirmish, was virtually wiped out, and Pulaski was forced to retreat to the safety of the city's guns. Wilson, 2005, p. 108 Although some historians credit this action with Prevost's decision to withdraw back toward Savannah the next day (despite ongoing negotiations of a possible surrender of Charleston), that decision is more likely based on news Prevost received that Lincoln's larger force was returning to Charleston to face him, and that Prevost's troops had gone further than he had originally intended. One early historian criticized Pulaski's actions during that engagement as "ill-judged, ill-conducted, disgraceful and disastrous". Griffin, 1907, p. 95 The episode was of minor strategic consequence and did little to enhance the reputation of Pulaski's unit. Russell, 2000, p. 107

Although Pulaski frequently suffered from

Although Pulaski frequently suffered from malaria

Malaria is a mosquito-borne infectious disease that affects humans and other animals. Malaria causes symptoms that typically include fever, tiredness, vomiting, and headaches. In severe cases, it can cause jaundice, seizures, coma, or deat ...

while stationed in Charleston, he remained in active service. At the beginning of September, Lincoln prepared to launch an attempt to retake Savannah with French assistance. Pulaski was ordered to Augusta, where he was to join forces with General Lachlan McIntosh

Lachlan McIntosh (March 17, 1725 – February 20, 1806) was a Scottish American military and political leader during the American Revolution and the early United States. In a 1777 duel, he fatally shot Button Gwinnett, a signer of the Declarati ...

. Their combined forces were to serve as the forward elements of Lincoln's army. Colcock, 1883, p. 378 Pulaski captured a British outpost near Ogeechee River

The Ogeechee River is a U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map, accessed April 26, 2011 blackwater river in the U.S. state of Georgia. It heads at the confluence of its North and South ...

. Kajencki, 2005, p. 93 His units then acted as an advance guard for the allied French units under Admiral Charles Hector, comte d'Estaing

Jean Baptiste Charles Henri Hector, comte d'Estaing (24 November 1729 – 28 April 1794) was a French general and admiral. He began his service as a soldier in the War of the Austrian Succession, briefly spending time as a prisoner of war of the B ...

. He rendered great services during the siege of Savannah

The siege of Savannah or the Second Battle of Savannah was an encounter of the American Revolutionary War (1775–1783) in 1779. The year before, the city of Savannah, Georgia, had been captured by a British expeditionary corps under Lieutenan ...

, and in the assault of October 9 commanded the whole cavalry, both French and American.

Death and burial

While attempting to rally fleeing French forces during a cavalry charge, Pulaski was mortally wounded bygrapeshot

Grapeshot is a type of artillery round invented by a British Officer during the Napoleonic Wars. It was used mainly as an anti infantry round, but had other uses in naval combat.

In artillery, a grapeshot is a type of ammunition that consists of ...

. The reported grapeshot is on display at the Georgia Historical Society

The Georgia Historical Society (GHS) is a statewide historical society in Georgia. Headquartered in Savannah, Georgia, GHS is one of the oldest historical organizations in the United States. Since 1839, the society has collected, examined, and ta ...

in Savannah. The Charleston Museum also has a grapeshot reported to be from Pulaski's wound. Kajencki, 2005, p. 163 Pulaski was carried from the field of battle and taken aboard the South Carolina merchant brig

A brig is a type of sailing vessel defined by its rig: two masts which are both square-rigged. Brigs originated in the second half of the 18th century and were a common type of smaller merchant vessel or warship from then until the latter par ...

privateer

A privateer is a private person or ship that engages in maritime warfare under a commission of war. Since robbery under arms was a common aspect of seaborne trade, until the early 19th century all merchant ships carried arms. A sovereign or deleg ...

''Wasp'', under the command of Captain Samuel Bulfinch, where he died two days later, having never regained consciousness. His heroic death, admired by American Patriot supporters, further boosted his reputation in America. Storozynski, 2010, p. 91

Pulaski never married and had no descendants. Despite his fame, there have long been uncertainties and controversies surrounding both his place and date of birth, and his burial. Many primary sources record a burial at sea. The historical accounts for Pulaski's time and place of burial vary considerably. According to several contemporary accounts there were witnesses, including Pulaski's aide-de-camp, that Pulaski received a symbolic burial in Charleston on October 21, sometime after he was buried at sea

Burial at sea is the disposal of human remains in the ocean, normally from a ship or boat. It is regularly performed by navies, and is done by private citizens in many countries.

Burial-at-sea services are conducted at many different location ...

. American Council for Polish Culture Other witnesses, including Captain Samuel Bulfinch of the ''Wasp'', however, claimed that the wounded Pulaski was actually later removed from the ship and taken to the Greenwich Plantation in the town of Thunderbolt

A thunderbolt or lightning bolt is a symbolic representation of lightning when accompanied by a loud thunderclap. In Indo-European mythology, the thunderbolt was identified with the 'Sky Father'; this association is also found in later Hell ...

, near Savannah, where he died and was buried.

In March 1825, during his grand tour

The Grand Tour was the principally 17th- to early 19th-century custom of a traditional trip through Europe, with Italy as a key destination, undertaken by upper-class young European men of sufficient means and rank (typically accompanied by a tut ...

of the United States, Lafayette personally laid the cornerstone for the Casimir Pulaski Monument in Savannah, Georgia. Szymański, 1979, p. 301

Exhumation and analysis of remains

In 1853 remains found on a bluff above Augustine Creek on Greenwich Plantation were believed to be the general's. These bones are interred at the Casimir Pulaski Monument inSavannah, Georgia

Savannah ( ) is the oldest city in the U.S. state of Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia and is the county seat of Chatham County, Georgia, Chatham County. Established in 1733 on the Savannah River, the city of Savannah became the Kingdom of Great Br ...

. They were exhumed in 1996 and examined during a forensic study. The eight-year examination, including DNA analysis, ended inconclusively, although the skeleton was consistent with Pulaski's age and occupation. A healed wound on the skull's forehead was consistent with historical records of an injury Pulaski sustained in battle, as was a bone defect on the left cheekbone, believed to have been caused by a benign tumor. The Pulaski Mystery, 2008 In 2005, the remains were reinterred in a public ceremony with full military honors, including Pulaski's induction into the Georgia Military Hall of Fame.

A later study funded by the Smithsonian Institution

The Smithsonian Institution ( ), or simply the Smithsonian, is a group of museums and education and research centers, the largest such complex in the world, created by the U.S. government "for the increase and diffusion of knowledge". Found ...

, the results of which were released in 2019, concluded from the mitochondrial DNA of his grandniece, known injuries, and physical characteristics, that the skeleton was likely Pulaski's. The skeleton has a number of typically female features, which has led to the hypothesis that Pulaski may have been female or intersex

Intersex people are individuals born with any of several sex characteristics including chromosome patterns, gonads, or genitals that, according to the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, "do not fit typical b ...

. A documentary based on the Smithsonian study suggests that Pulaski's hypothesized intersex condition could have been caused by congenital adrenal hyperplasia

Congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH) is a group of autosomal recessive disorders characterized by impaired cortisol synthesis. It results from the deficiency of one of the five enzymes required for the synthesis of cortisol in the adrenal cortex. ...

, where a fetus with female chromosomes is exposed to a high level of testosterone

Testosterone is the primary sex hormone and anabolic steroid in males. In humans, testosterone plays a key role in the development of male reproductive tissues such as testes and prostate, as well as promoting secondary sexual characteristi ...

in utero and develops partially male genitals. This analysis was based on the skeleton's female pelvis, facial structure and jaw angle, in combination with the fact that Pulaski identified as and lived as male.

Tributes and commemoration

The United States has long commemorated Pulaski's contributions to the American Revolutionary War, and already on October 29, 1779, the

The United States has long commemorated Pulaski's contributions to the American Revolutionary War, and already on October 29, 1779, the United States Congress

The United States Congress is the legislature of the federal government of the United States. It is bicameral, composed of a lower body, the House of Representatives, and an upper body, the Senate. It meets in the U.S. Capitol in Washi ...

passed a resolution that a monument should be dedicated to him, but the first monument to him, the Casimir Pulaski Monument in Savannah, Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to th ...

, was not built until 1854. A bust of Pulaski was added to a collection of other busts of American heroes at United States Capitol

The United States Capitol, often called The Capitol or the Capitol Building, is the seat of the legislative branch of the United States federal government, which is formally known as the United States Congress. It is located on Capitol Hill ...

in 1867. On May 11, 1910, US President William Taft

William Howard Taft (September 15, 1857March 8, 1930) was the 27th president of the United States (1909–1913) and the tenth chief justice of the United States (1921–1930), the only person to have held both offices. Taft was elected pr ...

revealed a Congress-sponsored General Casimir Pulaski statue. In 1929, Congress passed another resolution, this one recognizing October 11 of each year as " General Pulaski Memorial Day", with a large parade held annually on Fifth Avenue

Fifth Avenue is a major and prominent thoroughfare in the borough (New York City), borough of Manhattan in New York City. It stretches north from Washington Square Park in Greenwich Village to 143rd Street (Manhattan), West 143rd Street in Har ...

in New York City. Separately, a Casimir Pulaski Day is celebrated in Illinois

Illinois ( ) is a state in the Midwestern United States. Its largest metropolitan areas include the Chicago metropolitan area, and the Metro East section, of Greater St. Louis. Other smaller metropolitan areas include, Peoria and Rockf ...

and some other places on the first Monday of each March. In some Illinois school districts, the day is an official school holiday. After a previous attempt failed, Congress passed a joint resolution conferring honorary U.S. citizenship on Pulaski in 2009, sending it to President Barack Obama

Barack Hussein Obama II ( ; born August 4, 1961) is an American politician who served as the 44th president of the United States from 2009 to 2017. A member of the Democratic Party, Obama was the first African-American president of the U ...

for approval. He duly signed it on November 6, 2009, making Pulaski the seventh person so honored.

In Poland, in 1793 Pulaski's relative, Antoni Pułaski, obtained a cancellation of his brother's sentence from 1773. He has been mentioned in the literary works of numerous Polish authors, including

In Poland, in 1793 Pulaski's relative, Antoni Pułaski, obtained a cancellation of his brother's sentence from 1773. He has been mentioned in the literary works of numerous Polish authors, including Adam Mickiewicz

Adam Bernard Mickiewicz (; 24 December 179826 November 1855) was a Polish poet, dramatist, essayist, publicist, translator and political activist. He is regarded as national poet in Poland, Lithuania and Belarus. A principal figure in Polish ...

, Juliusz Słowacki

Juliusz Słowacki (; french: Jules Slowacki; 4 September 1809 – 3 April 1849) was a Polish Romantic poet. He is considered one of the " Three Bards" of Polish literature — a major figure in the Polish Romantic period, and the father of mo ...

and Józef Ignacy Kraszewski. Adolf Nowaczyński wrote a drama "Pułaski w Ameryce" (Pulaski in America) in 1917. A museum dedicated to Pulaski, the Casimir Pulaski Museum in Warka, opened in 1967.

Throughout Poland and the United States, people have celebrated anniversaries of Pulaski's birth and death, and there exist numerous objects of art such as paintings and statues of him. In 1879, to commemorate the 100th anniversary of his death, Henri Schoeller composed "A Pulaski March". Twenty years earlier, Eduard Sobolewski composed his opera, "Mohega", about the last days of Pulaski's life. Commemorative medals and stamps of Pulaski have been issued. Several cities, towns, townships

A township is a kind of human settlement or administrative subdivision, with its meaning varying in different countries.

Although the term is occasionally associated with an urban area, that tends to be an exception to the rule. In Australia, Ca ...

and counties

A county is a geographic region of a country used for administrative or other purposesChambers Dictionary, L. Brookes (ed.), 2005, Chambers Harrap Publishers Ltd, Edinburgh in certain modern nations. The term is derived from the Old French ...

in United States are named after him, as are numerous streets, parks and structures.

Although his statue stands in Savannah's Monterey Square, the city's Pulaski Square is named for him.City of Savannah's monuments pageThis page links directly to numerous short entries, many accompanied by photographs, discussing a variety of monuments, memorials, etc., in the squares and elsewhere. Accessed June 16, 2007. The

Pulaski Bridge

The Pulaski Bridge in New York City connects Long Island City in Queens to Greenpoint in Brooklyn over Newtown Creek. It was named after Polish military commander and American Revolutionary War fighter Casimir Pulaski in homage to the large P ...

in New York City links Brooklyn to Queens; the Pulaski Skyway

The Pulaski Skyway is a four-lane bridge-causeway in the northeastern part of the U.S. state of New Jersey, carrying an expressway designated U.S. Route 1/9 (US 1/9) for most of its length. The structure has a total length of . Its ...

in Northern New Jersey links Jersey City to Newark, and the Pulaski Highway traverses the city of Baltimore, Maryland.

Michigan designated US Highway 112 (now US 12

U.S. Route 12 (US 12) is an east–west United States highway, running from Aberdeen, Washington, to Detroit, Michigan, for almost . The highway has mostly been superseded by Interstate 90 (I-90) and I-94, but unlike most U.S. routes tha ...

) as Pulaski Memorial Highway in 1935.

There are also a number of educational, academic, and Polish-American

Polish Americans ( pl, Polonia amerykańska) are Americans who either have total or partial Polish ancestry, or are citizens of the Republic of Poland. There are an estimated 9.15 million self-identified Polish Americans, representing about 2.83 ...

institutions named after him. A US Navy submarine, , has been named for him, as was a 19th-century United States Revenue Cutter Service

)

, colors=

, colors_label=

, march=

, mascot=

, equipment=

, equipment_label=

, battles=

, anniversaries=4 August

, decorations=

, battle_honours=

, battle_honours_label=

, disbanded=28 January 1915

, flying_hours=

, website=

, commander1=

, co ...

cutter. U.S. Coast Guard, Pulaski, 1825 A Polish frigate, ORP ''Generał Kazimierz Pułaski'', is also named after Pulaski. Fort Pulaski

A fortification is a military construction or building designed for the defense of territories in warfare, and is also used to establish rule in a region during peacetime. The term is derived from Latin ''fortis'' ("strong") and ''facere'' ...

between Savannah

A savanna or savannah is a mixed woodland- grassland (i.e. grassy woodland) ecosystem characterised by the trees being sufficiently widely spaced so that the canopy does not close. The open canopy allows sufficient light to reach the ground ...

and Tybee Island in Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to th ...

, active during the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states ...

, is named in honor of Casimir Pulaski. Pulaski Barracks, an active U.S. Army post in Kaiserslautern, Germany, is named for Casimir Pulaski in honor of the Polish people who worked for the U.S. Army in Civilian Service Groups after WWII. A statue commemorating Pulaski stands at the eastern end of Freedom Plaza

Freedom Plaza, originally known as Western Plaza, is an open plaza in Northwest Washington, D.C., United States, located near 14th Street and Pennsylvania Avenue NW, adjacent to Pershing Park. The plaza features an inlay that partially depic ...

in Washington, D.C. There is an equestrian statue of Pulaski in Roger Williams Park in Providence, Rhode Island

Providence is the capital and most populous city of the U.S. state of Rhode Island. One of the oldest cities in New England, it was founded in 1636 by Roger Williams, a Reformed Baptist theologian and religious exile from the Massachusetts ...

, as well as one in the center of Pulaski park in Manchester, New Hampshire

Manchester is a city in Hillsborough County, New Hampshire, United States. It is the most populous city in New Hampshire. At the 2020 census, the city had a population of 115,644.

Manchester is, along with Nashua, one of two seats of New H ...

. A statue by Granville W. Carter depicting Pulaski on a rearing horse signaling a forward charge with a sword in his right hand is erected in Hartford, Connecticut

Hartford is the capital city of the U.S. state of Connecticut. It was the seat of Hartford County until Connecticut disbanded county government in 1960. It is the core city in the Greater Hartford metropolitan area. Census estimates since t ...

. There is a Pulaski Monument in Patterson Park in Baltimore, Maryland. There is also a statue in Buffalo, NY near the intersection of Main and S. Division St.

The villages of Mt. Pulaski, Illinois,

The villages of Mt. Pulaski, Illinois, Pulaski, New York

Pulaski () is a village in Oswego County, New York, United States. The population was 2,365 at the 2010 census.

The Village of Pulaski is within the Town of Richland, and lies between the eastern shore of Lake Ontario and the Tug Hill region. ...

, and Pulaski, Wisconsin

Pulaski is a village in Brown, Oconto, and Shawano counties in the U.S. state of Wisconsin. The population was 3,539 at the 2010 census. Of this, 3,321 were in Brown County, 218 in Shawano County, and none in Oconto County.

The Brown and Oco ...

, are named for him, as is the city of Pulaski, Tennessee

Pulaski is a city in and the county seat of Giles County, which is located on the central-southern border of Tennessee, United States. The population was 8,397 at the 2020 census. It was named after Casimir Pulaski, a noted Polish-born soldier o ...

. Pulaski High School and Casimir Pulaski High School, both in Wisconsin, are also named after him, as is Pulaski Middle School in New Britain, Connecticut

New Britain is a city in Hartford County, Connecticut, United States. It is located approximately southwest of Hartford. According to 2020 Census, the population of the city is 74,135.

Among the southernmost of the communities encompassed wi ...

. Pulaski County in Virginia, Pulaski County in Arkansas, Pulaski County in Georgia, Pulaski County in Missouri, Pulaski County in Kentucky, and Pulaski County in Indiana are named after him as well.

Polish historian Władysław Konopczyński, who wrote a monograph on Pulaski in 1931, noted that he was one of the most accomplished Polish people, grouping him with other Polish military heroes such as Tadeusz Kościuszko

Andrzej Tadeusz Bonawentura Kościuszko ( be, Andréj Tadévuš Banavientúra Kasciúška, en, Andrew Thaddeus Bonaventure Kosciuszko; 4 or 12 February 174615 October 1817) was a Polish military engineer, statesman, and military leader who ...

, Stanisław Żółkiewski, Stefan Czarniecki

Stefan Czarniecki (Polish: of the Łodzia coat of arms, 1599 – 16 February 1665) was a Polish nobleman, general and military commander. In his career, he rose from a petty nobleman to a magnate holding one of the highest offices in the Comm ...

, and Prince Józef Poniatowski

Prince Józef Antoni Poniatowski (; 7 May 1763 – 19 October 1813) was a Polish general, minister of war and army chief, who became a Marshal of the French Empire during the Napoleonic Wars.

A nephew of king Stanislaus Augustus of Poland (), ...

.

In popular culture

•

• Michigan

Michigan () is a state in the Great Lakes region of the upper Midwestern United States. With a population of nearly 10.12 million and an area of nearly , Michigan is the 10th-largest state by population, the 11th-largest by area, and the ...

-born songwriter Sufjan Stevens

Sufjan Stevens ( ; born July 1, 1975) is an American singer, songwriter, and multi-instrumentalist. He has released nine solo studio albums and multiple collaborative albums with other artists. Stevens has received Grammy and Academy Award nomi ...

released a song called "Casimir Pulaski Day" on his album ''Illinois

Illinois ( ) is a state in the Midwestern United States. Its largest metropolitan areas include the Chicago metropolitan area, and the Metro East section, of Greater St. Louis. Other smaller metropolitan areas include, Peoria and Rockf ...

''. The song interweaves his memories of a friend's battle with bone cancer

A bone tumor is an abnormal growth of tissue in bone, traditionally classified as noncancerous (benign) or cancerous (malignant). Cancerous bone tumors usually originate from a cancer in another part of the body such as from lung, breast, thyr ...

with an account of the holidays.

• In a downloadable content of ''Age of Empires III

''Age of Empires III'' is a real-time strategy video game developed by Microsoft Corporation's Ensemble Studios and published by Microsoft Game Studios. The Mac version was ported over and developed and published by Destineer's MacSoft. The PC ...

'', twelve ''Uhlan

Uhlans (; ; ; ; ) were a type of light cavalry, primarily armed with a lance. While first appearing in the cavalry of Lithuania and then Poland, Uhlans were quickly adopted by the mounted forces of other countries, including France, Russia, P ...

'' cavalry units can be summoned by the player by clicking on a shipment button called Pulaski's Legion.

• An account of Pulaski's death and burial is used as the background and setting for the family reunion of two POV characters in Diana Gabaldon's ninth main Outlander novel, ''Go Tell the Bees That I Am Gone'' (2021). Her historical observations and inspirations are in her author's notes.Gabaldon, Diana, 2021-Nov. ''Go Tell the Bees That I Am Gone'', chapters 93–97 (pp 622–657), chapters 119–120 (pp 760–767), and author's notes, pp 962–963. Delacorte Press (Penguin Random House), ISBN 978-1-10-188569-7.

See also

* Casimir Pulaski Foundation - leading Polish think tank specialized in foreign policy and national security *Johann de Kalb

Johann von Robais, Baron de Kalb (June 19, 1721 – August 19, 1780), born Johann Kalb, was a Franconian-born French military officer who served as a major general in the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War. He was mortally ...

, a Bavarian-born French officer who served as a general in the Continental Army

* Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette

Marie-Joseph Paul Yves Roch Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de La Fayette (6 September 1757 – 20 May 1834), known in the United States as Lafayette (, ), was a French aristocrat, freemason and military officer who fought in the American Revolutio ...

, a French officer who served as a general in the Continental Army

* '' The General Was Female?'', documentary film about Pulaski's possible intersex status

* Intersex people and military service in the United States

* Knight of Freedom Award, an award established in honour of General Pulaski

* Michael Kovats de Fabriczy

Michael Kovats de Fabriczy (often simply Michael Kovats; hu, Kováts Mihály; 1724 – May 11, 1779) was a Hungarian nobleman and cavalry officer who served in the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War, in which he was killed in ...

, a Hungarian nobleman and cavalry officer who served in the Continental Army

* List of Poles

This is a partial list of notable Polish or Polish-speaking or -writing people. People of partial Polish heritage have their respective ancestries credited.

Science

Physics

* Czesław Białobrzeski

* Andrzej Buras

* Georges Charp ...

* Friedrich Wilhelm von Steuben

Friedrich Wilhelm August Heinrich Ferdinand von Steuben (born Friedrich Wilhelm Ludolf Gerhard Augustin Louis von Steuben; September 17, 1730 – November 28, 1794), also referred to as Baron von Steuben (), was a Prussian military officer who p ...

, a Prussian drill master who served in the Continental Army

Explanatory notes

Citations

General bibliography

* * * * *Url

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * Proclaiming Casimir Pulaski to be an honorary citizen of the United States. * * * * * Presidential Studies Quarterly Vol. XXIV No. 4 Fall 1994, pp. 876–77 * * * * *

Url

* *

Further reading

* *Url

*

Url

* * Shepherd, Joshua,

Soldiers: Casimir Pulaski

'' Warfare History Network, February 13, 2019 *

External links

* ttp://www.newadvent.org/cathen/12561a.htm Biography from ''Catholic Encyclopedia''

Casimir Pulaski Day

the Office of Civil Rights and Diversity at

Eastern Illinois University

Eastern Illinois University is a public university in Charleston, Illinois. Established in 1895 as the Eastern Illinois State Normal School, a teacher's college offering a two-year degree, Eastern Illinois University gradually expanded into a co ...

. Leszek Szymański, ''Casimir Pulaski: A Hero of the American Revolution'', E207.P8 S97 1994.

*

*

Casimir Pulaski Foundation

{{DEFAULTSORT:Pulaski, Casimir 1745 births 1779 deaths Bar confederates Burials in Georgia (U.S. state) Continental Army officers from Poland Intersex men Intersex military personnel Intersex people and military service in the United States Military personnel from Warsaw Nobility from Warsaw People sentenced to death in absentia Polish emigrants to the United States Polish generals in other armies Polish Roman Catholics

Casimir

Casimir is classically an English, French and Latin form of the Polish name Kazimierz. Feminine forms are Casimira and Kazimiera. It means "proclaimer (from ''kazać'' to preach) of peace (''mir'')."

List of variations

*Belarusian: Казі ...

United States military personnel killed in the American Revolutionary War