Kawakita v. United States on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Kawakita v. United States'', 343 U.S. 717 (1952), is a

In a 4–3 decision issued on June 2, 1952, the Supreme Court upheld Kawakita's treason conviction and death sentence. The Court's opinion was written by

In a 4–3 decision issued on June 2, 1952, the Supreme Court upheld Kawakita's treason conviction and death sentence. The Court's opinion was written by

Chief Justice Fred M. Vinson authored a dissenting opinion, which was joined by Associate Justices

Chief Justice Fred M. Vinson authored a dissenting opinion, which was joined by Associate Justices

United States Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. federal court cases, and over state court cases that involve a point o ...

case in which the Court ruled that a dual U.S./Japanese citizen could be convicted of treason

Treason is the crime of attacking a state authority to which one owes allegiance. This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to overthrow its government, spying on its military, its diplo ...

against the United States for acts performed in Japan

Japan ( ja, 日本, or , and formally , ''Nihonkoku'') is an island country in East Asia. It is situated in the northwest Pacific Ocean, and is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan, while extending from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north ...

during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

.''Kawakita v. United States'', . Tomoya Kawakita, born in California to Japanese parents, was in Japan when the war broke out and stayed in Japan until the war was over. After returning to the United States, he was arrested and charged with treason for having abused American prisoners of war

A prisoner of war (POW) is a person who is held Captivity, captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Belligerents hold priso ...

. Kawakita claimed he could not be found guilty of treason since he had lost his U.S. citizenship while in Japan, but this argument was rejected by the courts (including the Supreme Court), which ruled that he had in fact retained his U.S. citizenship during the war. Originally sentenced to death

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty, is the state-sanctioned practice of deliberately killing a person as a punishment for an actual or supposed crime, usually following an authorized, rule-governed process to conclude that t ...

, Kawakita's sentence was commuted to life imprisonment, and he was eventually released from prison, deported to Japan, and barred from ever returning to the United States.

Kawakita is currently one of the last people to be convicted of treason in the United States. One other person, John David Provoo

John David Provoo (August 6, 1917 – August 28, 2001) was United States Army staff sergeant and practicing Buddhist who was convicted of treason for his conduct as a Japanese prisoner of war during World War II. His conviction was later overtu ...

, was convicted of treason in 1952. However, Provoo's conviction was overturned on appeal. The distinction currently goes to Herbert John Burgman

Herbert John Burgman (April 17, 1894 – December 16, 1953) was an American broadcaster of Nazi propaganda during World War II. He was convicted of treason in 1949 and sentenced to imprisonment for 6 to 20 years. Burgman died in prison in 1953.

B ...

, who was convicted of treason in 1949.

Background

was born inCalexico, California

Calexico () is a city in southern Imperial County, California. Situated on the Mexican border, it is linked economically with the much larger city of Mexicali, the capital of the Mexican state of Baja California. It is about east of San Diego ...

, on September 26, 1921, of Japanese-born parents. He was born with U.S. citizenship

Citizenship of the United States is a legal status that entails Americans with specific rights, duties, protections, and benefits in the United States. It serves as a foundation of fundamental rights derived from and protected by the Constituti ...

due to his place of birth, and also Japanese nationality

Japanese nationality law details the conditions by which a person holds nationality of Japan. The primary law governing nationality regulations is the 1950 Nationality Act.

Children born to at least one Japanese parent are generally automatical ...

via his parents. A former high school classmate of Kawakita, Joe Gomez, recalled him as quiet and serious, but sadistic in nature.

After finishing high school in Calexico in 1939, Kawakita traveled to Japan with his father (a grocer and merchant). He enrolled in Meiji University

, abbreviated as Meiji (明治) or Meidai (明大'')'', is a private research university located in Chiyoda City, the heart of Tokyo, Japan. Established in 1881 as Meiji Law School (明治法律学校, ''Meiji Hōritsu Gakkō'') by three Meiji-er ...

in 1941. In 1943, he registered officially as a Japanese national.

Kawakita was in Japan when the attack on Pearl Harbor

The attack on Pearl HarborAlso known as the Battle of Pearl Harbor was a surprise military strike by the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service upon the United States against the naval base at Pearl Harbor in Honolulu, Territory of Hawaii, j ...

drew the United States and Japan into World War II. In August 1943, with the assistance of a family friend, Takeo Miki

was a Japanese politician who served as Prime Minister of Japan from 1974 until 1976.

Early life and family

Takeo Miki was born on 17 March 1907, in Gosho, Tokushima Prefecture (present-day Awa, Tokushima), the only child of farmer-merchant H ...

, Kawakita took a job as an interpreter at a mining and metal processing plant.. Shortly after Kawakita started working there, British and Canadian POWs arrived. Kawakita was tasked with interpreting for them. The POWs were sometimes forced to work in the mine.

In 1944 and early in 1945, approximately 400 American POWs, many of whom were captured in Bataan

Bataan (), officially the Province of Bataan ( fil, Lalawigan ng Bataan ), is a province in the Central Luzon region of the Philippines. Its capital is the city of Balanga while Mariveles is the largest town in the province. Occupying the entir ...

in 1942 and had survived the subsequent death march

A death march is a forced march of prisoners of war or other captives or deportees in which individuals are left to die along the way. It is distinguished in this way from simple prisoner transport via foot march. Article 19 of the Geneva Convent ...

, arrived in the camp. Kawakita brutalized multiple American POWs during this time.The work done at the mine by the American prisoners consisted of digging nickel ore from the face of the mountain side, and loading it onto cars which were emptied into hoppers. The prisoners also performed other general labor in the mine area, including such duty as carrying logs to be used for construction and maintenance work.After Japan's surrender, Kawakita's attitude towards American POWs reportedly changed entirely. After the end of the war, Kawakita renewed his U.S. passport, explaining away his having registered as a Japanese national by claiming he had acted under duress. He returned to the U.S. in 1946 and enrolled at the

University of Southern California

The University of Southern California (USC, SC, or Southern Cal) is a Private university, private research university in Los Angeles, California, United States. Founded in 1880 by Robert M. Widney, it is the oldest private research university in C ...

.

In October 1946, a former POW, William L. Bruce saw Kawakita in a Los Angeles department store

A department store is a retail establishment offering a wide range of consumer goods in different areas of the store, each area ("department") specializing in a product category. In modern major cities, the department store made a dramatic app ...

and recognized him from the war. Bruce reported this encounter to the FBI

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) is the domestic Intelligence agency, intelligence and Security agency, security service of the United States and its principal Federal law enforcement in the United States, federal law enforcement age ...

, and in June 1947, Kawakita was arrested and charged with 15 counts of treason

Treason is the crime of attacking a state authority to which one owes allegiance. This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to overthrow its government, spying on its military, its diplo ...

arising from alleged abuse of American POWs.

In an interview shortly after the arrest, Bruce described his reaction to seeing Kawakita:"I was so dumbfounded, I just halted in my tracks and stared at him as he hurried by. It was a good thing, too. If I'd reacted then, I'm not sure but that I might have taken the law into my own hands--and probably Kawakita's neck."

Trial and appeal

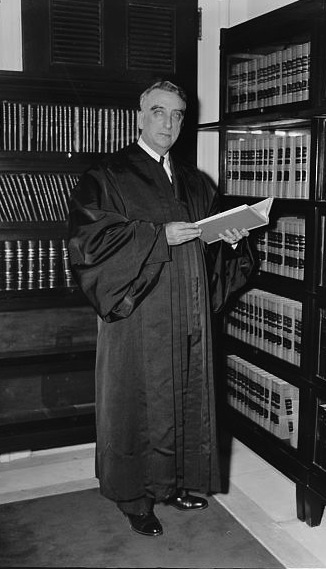

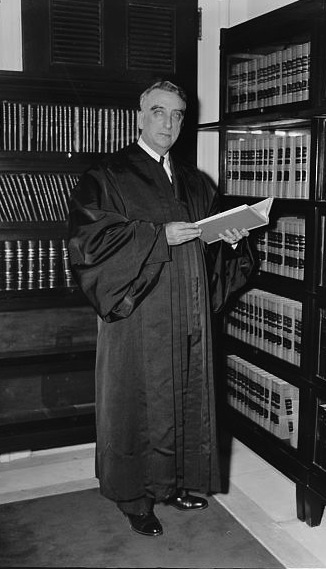

Nearly 100 ex-POWs said they were willing to testify against Kawakita. At Kawakita's trial, presided over byU.S. District Judge

The United States district courts are the trial courts of the U.S. federal judiciary. There is one district court for each federal judicial district, which each cover one U.S. state or, in some cases, a portion of a state. Each district cou ...

William C. Mathes and prosecuted by James Marshall Carter

James Marshall Carter (March 11, 1904 – November 18, 1979) was a United States circuit judge of the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit and previously was a United States district judge of the United States District Court for th ...

, over 30 ex-POWs testified that Kawakita had brutalized American POWs. He was said to have beaten prisoners, forced them to beat each other, and forced them to run until they collapsed from exhaustion if they finished their work assignments early. In one case, Kawakita was accused of causing the death of Einar Latvala, and American POW (he was later acquitted of that charge after two Canadians said Latvala had been killed by another guard). Two of the treason charges against Kawakita were later dropped.

One of the witnesses in Kawakita's defense was his childhood friend, Meiji Fujizawa. Fujizawa had also worked in Camp Oeyama, but wasn't prosecuted due to American POWs having overwhelmingly favorable opinions of him; they said Fujizawa had done the best he could to help them and get them medicine. Fujizawa said he never saw Kawakita beat anyone. He said beatings did happen in the camp, but those were done by military officials.

The defense conceded that Kawakita had acted abusively toward American POWs, but argued that his actions were relatively minor, and that in any event, they could not constitute treason against the United States as Kawakita was not a U.S. citizen at the time, having lost his U.S. citizenship when he confirmed his Japanese nationality in 1943. The prosecution argued that Kawakita had known he was still a U.S. citizen and still owed allegiance to the country of his birth—citing the statements he had made to consular officials when applying for a new passport as evidence that he had never intended to give up his U.S. citizenship.

Judge Mathes's instructed the jury that if they found Kawakita had genuinely believed he was no longer a U.S. citizen, then he must be found not guilty. He reminded them that Kawakita was on trial for treason, not for war crimes. During their deliberations, the jury reported several times that they were hopelessly deadlocked, but the judge insisted each time that they continue trying to reach a unanimous verdict. In the end—on September 2, 1948—the jury found Kawakita guilty of 8 of 13 counts of treason, and he was sentenced to death

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty, is the state-sanctioned practice of deliberately killing a person as a punishment for an actual or supposed crime, usually following an authorized, rule-governed process to conclude that t ...

. As a consequence of his conviction for treason, Kawakita's U.S. citizenship was also revoked.

In passing sentence, Mathes gave a speech:You gentlemen have performed your duties in this case most diligently. So has the jury. And this is now my responsibility. I want to make it perfectly clear that the sentence I impose here has no relation to any brutalities that may have been involved in this defendant's treatment of American prisoners of war. That is only an incident. So with any kindness that he may have shown them. It is only an incident. The defendant stands here convicted of the crime of treason. The fact that he was born of Japanese nationals has nothing to do with it. My views would be the same no matter who he was. Treason is the only crime, as has been said here several times, mentioned in our Constitution. The framers thought it of sufficient gravity to provide it as the only crime mentioned in the Constitution of the United States. As I view this matter, it is not a question of whether the defendant kicked some American prisoner of war or a dozen of them. His crime might be briefly put in two sentences. He said that from 1943 on he did everything he could to help the Japanese Government win the war. The jury found that he owed a duty of loyalty at that time to the United States. So his crime cannot be considered, I take it, in terms of beating up someone, no matter how brutal. His crime is a crime against the country of his birth. His crime is not against a few American prisoners of war. His crime is against the whole people of this country where he was born and where he was fed and where he was educated. Throughout history treason has always been the crime most abhorred by English-speaking peoples. The traitor has always been considered even worse than a murderer. And the distinction is based upon reason: for the murderer violates at most only a few, while the traitor violates all all the members of his society, all the members of the group to which he owes his allegiance. The punishment inflicted by the common law when traitors were publicly dragged to the place of execution and there drawn, quartered and beheaded recalls the extreme odium which our forebears attached to the crime of betraying one's country. The penalty for murder was death; for treason, death with vengeance. Today our law permits the life of a traitor to be spared. As it has been truly said: "It is the essence of treachery that those who commit it would still be severely punished if the law forgot its duty to provide deterrents to crime and did not lay a finger on them." If the defendant were to go from this Court a free man, he would be condemned to live out his life in bitter scorn of himself. Haunting him to the end of his days would be the memory not only of his base treason against the land of his birth, but also ofKawakita's mother broke down after hearing the sentence, and her son begged her not to kill herself. Kawakita was sent toSadao Munemori Sadao Munemori ( ja, 旨森 貞雄, August 17, 1922 – April 5, 1945) was a United States Army soldier and posthumous recipient of the Medal of Honor, after he sacrificed his life to save those of his fellow soldiers at Seravezza, Italy durin ...who won the Congressional Medal of Honor; of Privates First Class, Fumitaka Nagato and Saburo Tanamachi, who are buried with the American heroes of all time at Arlington National Cemetery; and the memory of almost seven hundred other boys of like American birthright, of like Japanese parentage, who stood the supreme test of loyalty to their native land, and gave up their lives that America and her institutions might continue to live. These thoughts and others must tell the defendant that his life, if spared, would not be worth living. Considering the inherent nature of treason and the purpose of the law in imposing punishment for the crime, reflection leads to the conclusion that the only worth-while use for the life of a traitor, such as this defendant has proved himself to be, is to serve as an example to those of weak moral fiber who may hereafter be tempted to commit treason against the United States.

San Quentin State Prison

San Quentin State Prison (SQ) is a California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation state prison for men, located north of San Francisco in the unincorporated place of San Quentin in Marin County.

Opened in July 1852, San Quentin is the ...

to await his execution. His execution would be carried out via lethal gas.

Kawakita appealed to a three-judge panel of the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals

The United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit (in case citations, 9th Cir.) is the U.S. federal court of appeals that has appellate jurisdiction over the U.S. district courts in the following federal judicial districts:

* District o ...

, which unanimously upheld the verdict and death sentence. ''Certiorari

In law, ''certiorari'' is a court process to seek judicial review of a decision of a lower court or government agency. ''Certiorari'' comes from the name of an English prerogative writ, issued by a superior court to direct that the record of ...

'' was granted by the United States Supreme Court,''Kawakita v. United States'', (granting ''certiorari''). and oral arguments before the Supreme Court were heard on April 3, 1952.

Opinion of the Court

In a 4–3 decision issued on June 2, 1952, the Supreme Court upheld Kawakita's treason conviction and death sentence. The Court's opinion was written by

In a 4–3 decision issued on June 2, 1952, the Supreme Court upheld Kawakita's treason conviction and death sentence. The Court's opinion was written by Associate Justice

Associate justice or associate judge (or simply associate) is a judicial panel member who is not the chief justice in some jurisdictions. The title "Associate Justice" is used for members of the Supreme Court of the United States and some state ...

William O. Douglas

William Orville Douglas (October 16, 1898January 19, 1980) was an American jurist who served as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States, who was known for his strong progressive and civil libertarian views, and is often c ...

, joined by Associate Justices Stanley F. Reed

Stanley Forman Reed (December 31, 1884 – April 2, 1980) was an American lawyer and jurist who served as an Associate Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court from 1938 to 1957. He also served as U.S. Solicitor General from 1935 to 1938.

Born in Mas ...

, Robert H. Jackson

Robert Houghwout Jackson (February 13, 1892 – October 9, 1954) was an American lawyer, jurist, and politician who served as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States, Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the Unit ...

, and Sherman Minton

Sherman "Shay" Minton (October 20, 1890 – April 9, 1965) was an American politician and jurist who served as a U.S. senator from Indiana and later became an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States; he was a member of the ...

.

The Court's majority held

Held may refer to:

Places

* Held Glacier

People Arts and media

* Adolph Held (1885–1969), U.S. newspaper editor, banker, labor activist

*Al Held (1928–2005), U.S. abstract expressionist painter.

*Alexander Held (born 1958), German television ...

that the jury in Kawakita's trial had been justified in concluding that he had not lost or given up his U.S. citizenship while he was in Japan during the war. The Court added that an American citizen owed allegiance to the United States, and could be found guilty of treason, no matter where he lived—even for actions committed in another country that also claimed him as a citizen. Further, given the flagrant nature of Kawakita's actions, the majority found that the trial judge had not acted arbitrarily in imposing a death sentence.

Dissent

Chief Justice Fred M. Vinson authored a dissenting opinion, which was joined by Associate Justices

Chief Justice Fred M. Vinson authored a dissenting opinion, which was joined by Associate Justices Hugo Black

Hugo Lafayette Black (February 27, 1886 – September 25, 1971) was an American lawyer, politician, and jurist who served as a U.S. Senator from Alabama from 1927 to 1937 and as an associate justice of the U.S. Supreme Court from 1937 to 1971. A ...

and Harold H. Burton

Harold Hitz Burton (June 22, 1888 – October 28, 1964) was an American politician and lawyer. He served as the 45th mayor of Cleveland, Ohio, as a U.S. Senator from Ohio, and as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United Stat ...

. The dissent concluded that "for over two years, awakitawas consistently demonstrating his allegiance to Japan, not the United States. As a matter of law, he expatriated himself as well as that can be done." On this basis, the dissenting justices would have reversed Kawakita's treason conviction.

Subsequent developments

On October 29, 1953, PresidentDwight D. Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower (born David Dwight Eisenhower; ; October 14, 1890 – March 28, 1969) was an American military officer and statesman who served as the 34th president of the United States from 1953 to 1961. During World War II, ...

, responding to appeals from the Japanese government commuted Kawakita's sentence to life imprisonment plus a $10,000 fine. After the commutation of his sentence, Kawakita was transferred to the Alcatraz Federal Penitentiary

United States Penitentiary, Alcatraz Island, also known simply as Alcatraz (, ''"the gannet"'') or The Rock was a maximum security federal prison on Alcatraz Island, off the coast of San Francisco, California, United States, the site of a for ...

. He was transferred to McNeil Island Federal Penitentiary after the closure of Alcatraz in 1963.

Throughout his imprisonment, Kawakita's three sisters lobbied for his release. They said their brother's trial had been unfair and racist. They questioned the fairness of his trial in California, given its horrendous history against Japanese-Americans. The Kennedy administration initially refused to release Kawakita. However, on October 24, 1963, President Kennedy ordered his release on the condition that he permanently leave the United States. This was one of his last presidential acts before his assassination.

Earlier that year, the Attorney General, Robert F. Kennedy

Robert Francis Kennedy (November 20, 1925June 6, 1968), also known by his initials RFK and by the nickname Bobby, was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 64th United States Attorney General from January 1961 to September 1964, ...

had sought the opinions of those who were involved in the case. Mathes was adamantly opposed, but James Carter supported clemency, as did the lower appellate judge who wrote the opinion upholding Kawakita's conviction.

Carter said Kawakita should be released, but exiled. Robert Kennedy, forwarded the recommendation to his brother. He acknowledged Kawakita's crimes, but said he'd been a model prisoner. The Japan Desk of the Department of State

The United States Department of State (DOS), or State Department, is an executive department of the U.S. federal government responsible for the country's foreign policy and relations. Equivalent to the ministry of foreign affairs of other nati ...

said releasing Kawakita would boost foreign relations.

On October 24, 1963, President John F. Kennedy

John Fitzgerald Kennedy (May 29, 1917 – November 22, 1963), often referred to by his initials JFK and the nickname Jack, was an American politician who served as the 35th president of the United States from 1961 until his assassination i ...

—in what would be one of his last official acts before his assassination

Assassination is the murder of a prominent or important person, such as a head of state, head of government, politician, world leader, member of a royal family or CEO. The murder of a celebrity, activist, or artist, though they may not have ...

—ordered Kawakita released from prison on the condition that he leave the United States and be banned from ever returning. Kennedy justified Kawakita's release by saying he had now served more time than any other war criminal in Japan (the last Japanese war criminals serving time in Sugamo Prison

Sugamo Prison (''Sugamo Kōchi-sho'', Kyūjitai: , Shinjitai: ) was a prison in Tokyo, Japan. It was located in the district of Ikebukuro, which is now part of the Toshima ward of Tokyo, Japan.

History

Sugamo Prison was originally built in 1 ...

were paroled in 1958). Kawakita flew to Japan on December 13, 1963, and reacquired Japanese citizenship upon his arrival. In 1978, Kawakita sought permission to travel to the United States to visit his parents' grave, but his efforts were unsuccessful. As of late 1993, he was living quietly with relatives in Japan. When exactly he died, assuming he has died, is unknown.

See also

*List of United States Supreme Court cases, volume 343

This is a list of all United States Supreme Court cases from volume 343 of the ''United States Reports

The ''United States Reports'' () are the official record ( law reports) of the Supreme Court of the United States. They include rulings, ord ...

* Iva Toguri D'Aquino

Iva Ikuko Toguri D'Aquino ( ja, 戸栗郁子 アイバ; July 4, 1916 – September 26, 2006) was a Japanese-American disc jockey and radio personality who participated in English-language radio broadcasts transmitted by Radio Tokyo to Allied t ...

, another Japanese-American convicted of treason for actions committed during World War II

* Kanao Inouye, a Japanese-Canadian convicted of treason and executed for actions committed during World War II

References

External links

* {{good article United States Supreme Court cases United States Supreme Court cases of the Vinson Court 1952 in United States case law United States immigration and naturalization case law Japan–United States relations United States in World War II Treason in the United States Deportation from the United States