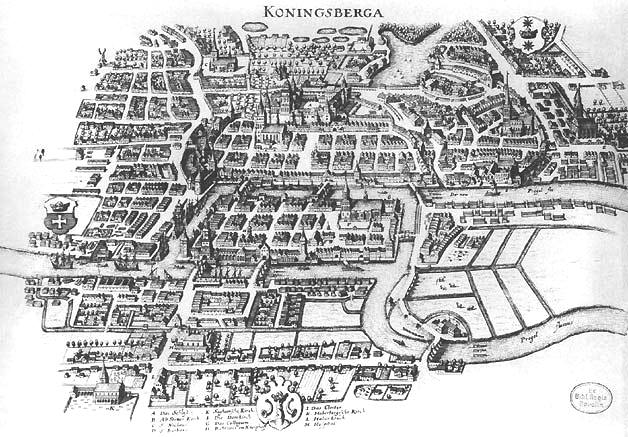

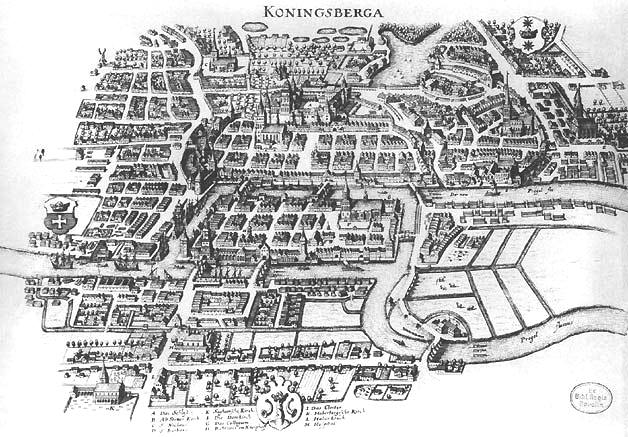

Königsberg 1656 on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Königsberg (, ) was the historic

During the conquest of the Prussian

During the conquest of the Prussian  Within the

Within the

While the Prussian estates quickly allied with the duke, the Prussian peasantry would only swear allegiance to Albert in person at Königsberg, seeking the duke's support against the oppressive nobility. After convincing the rebels to lay down their arms, Albert had several of their leaders executed.

Königsberg, the capital, became one of the biggest cities and ports of Ducal Prussia, having considerable autonomy, a separate

While the Prussian estates quickly allied with the duke, the Prussian peasantry would only swear allegiance to Albert in person at Königsberg, seeking the duke's support against the oppressive nobility. After convincing the rebels to lay down their arms, Albert had several of their leaders executed.

Königsberg, the capital, became one of the biggest cities and ports of Ducal Prussia, having considerable autonomy, a separate

In 1661 Frederick William informed the Prussian diet that he possessed ''jus supremi et absoluti domini'', and that the

In 1661 Frederick William informed the Prussian diet that he possessed ''jus supremi et absoluti domini'', and that the

By the act of coronation in

By the act of coronation in

Following the defeat of the

Following the defeat of the

In 1935, the

In 1935, the

In 1944, Königsberg suffered heavy damage from British bombing attacks and burned for several days. The historic city center, especially the original quarters Altstadt, Löbenicht, and Kneiphof were destroyed, including the cathedral, the castle, all churches of the old city, the old and the new universities, and the old shipping quarters.

Many people fled from Königsberg ahead of the

In 1944, Königsberg suffered heavy damage from British bombing attacks and burned for several days. The historic city center, especially the original quarters Altstadt, Löbenicht, and Kneiphof were destroyed, including the cathedral, the castle, all churches of the old city, the old and the new universities, and the old shipping quarters.

Many people fled from Königsberg ahead of the

The Jewish community in the city had its origins in the 16th century, with the arrival of the first Jews in 1538. The first synagogue was built in 1756. A second, smaller synagogue which served Orthodox Jews was constructed later, eventually becoming the Königsberg Synagogue, New Synagogue.

The Jewish population of Königsberg in the 18th century was fairly low, although this changed as restrictions became relaxed over the course of the 19th century. In 1756 there were 29 families of "protected Jews" in Königsberg, which increased to 57 by 1789. The total number of Jewish inhabitants was less than 500 in the middle of the 18th century, and around 800 by the end of it, out of a total population of almost 60,000 people.

The number of Jewish inhabitants peaked in 1880 at about 5,000, many of whom were migrants escaping pogroms in the Russian Empire. This number declined subsequently so that by 1933, when the Nazis took over, the city had about 3,200 Jews. As a result of anti-semitism and persecution in the 1920s and 1930s two-thirds of the city's Jews emigrated, mostly to the US and Great Britain. Those who remained were shipped by the Germans to concentration camps in two waves; first in 1938 to various camps in Germany, and the second in 1942 to the Theresienstadt concentration camp in occupied Czechoslovakia, Kaiserwald concentration camp in occupied Latvia, as well as camps in Maly Trostenets extermination camp, Minsk in the occupied Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic.

The Jewish community in the city had its origins in the 16th century, with the arrival of the first Jews in 1538. The first synagogue was built in 1756. A second, smaller synagogue which served Orthodox Jews was constructed later, eventually becoming the Königsberg Synagogue, New Synagogue.

The Jewish population of Königsberg in the 18th century was fairly low, although this changed as restrictions became relaxed over the course of the 19th century. In 1756 there were 29 families of "protected Jews" in Königsberg, which increased to 57 by 1789. The total number of Jewish inhabitants was less than 500 in the middle of the 18th century, and around 800 by the end of it, out of a total population of almost 60,000 people.

The number of Jewish inhabitants peaked in 1880 at about 5,000, many of whom were migrants escaping pogroms in the Russian Empire. This number declined subsequently so that by 1933, when the Nazis took over, the city had about 3,200 Jews. As a result of anti-semitism and persecution in the 1920s and 1930s two-thirds of the city's Jews emigrated, mostly to the US and Great Britain. Those who remained were shipped by the Germans to concentration camps in two waves; first in 1938 to various camps in Germany, and the second in 1942 to the Theresienstadt concentration camp in occupied Czechoslovakia, Kaiserwald concentration camp in occupied Latvia, as well as camps in Maly Trostenets extermination camp, Minsk in the occupied Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic.

Poles were among the first professors of the

Poles were among the first professors of the  According to historian Janusz Jasiński, based on estimates obtained from the records of St. Nicholas's Church, during the 1530s Lutheran Poles constituted about one quarter of the city population. This does not include Polish Catholics or Calvinists who did not have centralised places of worship until the 17th century, hence records that far back for these two groups are not available.

From the 16th to 20th centuries, the city was a publishing center of Polish-language religious literature. In 1545 in Königsberg a Polish catechism was printed by Jan Seklucjan. In 1551 the first translation of the

According to historian Janusz Jasiński, based on estimates obtained from the records of St. Nicholas's Church, during the 1530s Lutheran Poles constituted about one quarter of the city population. This does not include Polish Catholics or Calvinists who did not have centralised places of worship until the 17th century, hence records that far back for these two groups are not available.

From the 16th to 20th centuries, the city was a publishing center of Polish-language religious literature. In 1545 in Königsberg a Polish catechism was printed by Jan Seklucjan. In 1551 the first translation of the

In the Königsstraße (King Street) stood the Academy of Art with a collection of over 400 paintings. About 50 works were by Italian art, Italian masters; some early Dutch art, Dutch paintings were also to be found there. At the King's Gate (Kaliningrad), King's Gate stood statues of King Ottakar I of Bohemia, Albert, Duke of Prussia, Albert of Prussia, and Frederick I of Prussia. Königsberg had a magnificent Exchange (completed in 1875) with fine views of the harbour from the staircase. Along Bahnhofsstraße ("Station Street") were the offices of the famous Royal Amber Works – Samland was celebrated as the "Amber Coast". There was also an Koenigsberg Observatory, observatory fitted up by the astronomer Friedrich Bessel, a botanical garden, and a zoological museum. The "Physikalisch", near the Heumarkt, contained botanical and anthropological collections and prehistoric antiquities. Two large theatres built during the Wilhelmine era were the Stadttheater Königsberg, Stadttheater (municipal theatre) and the Apollo.

In the Königsstraße (King Street) stood the Academy of Art with a collection of over 400 paintings. About 50 works were by Italian art, Italian masters; some early Dutch art, Dutch paintings were also to be found there. At the King's Gate (Kaliningrad), King's Gate stood statues of King Ottakar I of Bohemia, Albert, Duke of Prussia, Albert of Prussia, and Frederick I of Prussia. Königsberg had a magnificent Exchange (completed in 1875) with fine views of the harbour from the staircase. Along Bahnhofsstraße ("Station Street") were the offices of the famous Royal Amber Works – Samland was celebrated as the "Amber Coast". There was also an Koenigsberg Observatory, observatory fitted up by the astronomer Friedrich Bessel, a botanical garden, and a zoological museum. The "Physikalisch", near the Heumarkt, contained botanical and anthropological collections and prehistoric antiquities. Two large theatres built during the Wilhelmine era were the Stadttheater Königsberg, Stadttheater (municipal theatre) and the Apollo.

Königsberg was well known within Germany for its unique regional cuisine. A popular dish from the city was Königsberger Klopse, which is still made today in some specialist restaurants in the now Russian city and elsewhere in present-day Germany.

Other food and drink native to the city included:

* Königsberger Marzipan

* Kopskiekelwein, a wine made from blackcurrants or redcurrants

* Bärenfang

* Ochsenblut, literally "ox blood", a champagne-burgundy cocktail mixed at the popular Blutgericht pub, which no longer exists

Königsberg was well known within Germany for its unique regional cuisine. A popular dish from the city was Königsberger Klopse, which is still made today in some specialist restaurants in the now Russian city and elsewhere in present-day Germany.

Other food and drink native to the city included:

* Königsberger Marzipan

* Kopskiekelwein, a wine made from blackcurrants or redcurrants

* Bärenfang

* Ochsenblut, literally "ox blood", a champagne-burgundy cocktail mixed at the popular Blutgericht pub, which no longer exists

The fortifications of Königsberg consist of numerous defensive walls, forts, bastions and other structures. They make up the First and the Second Defensive Belt, built in 1626–1634 and 1843–1859, respectively. The 15-metre-thick First Belt was erected due to Königsberg's vulnerability during the Polish–Swedish wars. The Second Belt was largely constructed on the place of the first one, which was in a bad condition. The new belt included twelve bastions, three ravelins, seven spoil banks and two fortresses, surrounded by water moat. Ten brick gates served as entrances and passages through defensive lines and were equipped with moveable bridges.

There was a Bismarck tower just outside Königsberg, on the Galtgarben, the highest point on the Sambian peninsula. It was built in 1906 and destroyed by German troops sometime in January 1945 East Prussian Offensive, as the Soviets approached.:de:Galtgarben, Galtgarben (German Wikipedia)

The fortifications of Königsberg consist of numerous defensive walls, forts, bastions and other structures. They make up the First and the Second Defensive Belt, built in 1626–1634 and 1843–1859, respectively. The 15-metre-thick First Belt was erected due to Königsberg's vulnerability during the Polish–Swedish wars. The Second Belt was largely constructed on the place of the first one, which was in a bad condition. The new belt included twelve bastions, three ravelins, seven spoil banks and two fortresses, surrounded by water moat. Ten brick gates served as entrances and passages through defensive lines and were equipped with moveable bridges.

There was a Bismarck tower just outside Königsberg, on the Galtgarben, the highest point on the Sambian peninsula. It was built in 1906 and destroyed by German troops sometime in January 1945 East Prussian Offensive, as the Soviets approached.:de:Galtgarben, Galtgarben (German Wikipedia)

Photoarchaeology of Kneiphof

The Film ''Königsberg is dead'', France/Germany 2004 by Max & Gilbert

* [http://www.kng750.kanet.ru/index.htm Site with 400+ side-by-side photos of 1939/2005 identical locations in Königsberg/Kaliningrad]

Northeast Prussia 2000: Travel Photos

{{DEFAULTSORT:Konigsberg Königsberg, Kaliningrad Populated places established in the 1250s Histories of cities in Germany Capitals of former nations East Prussia Germany–Soviet Union relations Members of the Hanseatic League Kulm law 1255 establishments in Europe 13th century in the State of the Teutonic Order

Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an em ...

n city that is now Kaliningrad

Kaliningrad ( ; rus, Калининград, p=kəlʲɪnʲɪnˈɡrat, links=y), until 1946 known as Königsberg (; rus, Кёнигсберг, Kyonigsberg, ˈkʲɵnʲɪɡzbɛrk; rus, Короле́вец, Korolevets), is the largest city and ...

, Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia, Northern Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the ...

. Königsberg was founded in 1255 on the site of the ancient Old Prussian

Old Prussian was a Western Baltic language belonging to the Baltic branch of the Indo-European languages, which was once spoken by the Old Prussians, the Baltic peoples of the Prussian region. The language is called Old Prussian to avoid con ...

settlement ''Twangste'' by the Teutonic Knights

The Order of Brothers of the German House of Saint Mary in Jerusalem, commonly known as the Teutonic Order, is a Catholic religious institution founded as a military society in Acre, Kingdom of Jerusalem. It was formed to aid Christians on ...

during the Northern Crusades

The Northern Crusades or Baltic Crusades were Christianity and colonialism, Christian colonization and Christianization campaigns undertaken by Catholic Church, Catholic Christian Military order (society), military orders and kingdoms, primarily ...

, and was named in honour of King Ottokar II of Bohemia

Ottokar II ( cs, Přemysl Otakar II.; , in Městec Králové, Bohemia – 26 August 1278, in Dürnkrut, Lower Austria), the Iron and Golden King, was a member of the Přemyslid dynasty who reigned as King of Bohemia from 1253 until his deat ...

. A Baltic

Baltic may refer to:

Peoples and languages

* Baltic languages, a subfamily of Indo-European languages, including Lithuanian, Latvian and extinct Old Prussian

*Balts (or Baltic peoples), ethnic groups speaking the Baltic languages and/or originati ...

port city, it successively became the capital of the Królewiec Voivodeship, the State of the Teutonic Order

The State of the Teutonic Order (german: Staat des Deutschen Ordens, ; la, Civitas Ordinis Theutonici; lt, Vokiečių ordino valstybė; pl, Państwo zakonu krzyżackiego), also called () or (), was a medieval Crusader state, located in Centr ...

, the Duchy of Prussia

The Duchy of Prussia (german: Herzogtum Preußen, pl, Księstwo Pruskie, lt, Prūsijos kunigaikštystė) or Ducal Prussia (german: Herzogliches Preußen, link=no; pl, Prusy Książęce, link=no) was a duchy in the Prussia (region), region of P ...

and the provinces of East Prussia

East Prussia ; german: Ostpreißen, label=Low Prussian; pl, Prusy Wschodnie; lt, Rytų Prūsija was a province of the Kingdom of Prussia from 1773 to 1829 and again from 1878 (with the Kingdom itself being part of the German Empire from 187 ...

and Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an em ...

. Königsberg remained the coronation city of the Prussian monarchy, though the capital was moved to Berlin

Berlin ( , ) is the capital and largest city of Germany by both area and population. Its 3.7 million inhabitants make it the European Union's most populous city, according to population within city limits. One of Germany's sixteen constitue ...

in 1701.

Between the thirteenth and the twentieth centuries, the inhabitants spoke predominantly German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

** Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ge ...

, but the multicultural city also had a profound influence upon the Lithuanian and Polish cultures. The city was a publishing center of Lutheran literature, including the first Polish translation of the New Testament

The New Testament grc, Ἡ Καινὴ Διαθήκη, transl. ; la, Novum Testamentum. (NT) is the second division of the Christian biblical canon. It discusses the teachings and person of Jesus, as well as events in first-century Christ ...

, printed in the city in 1551, the first book in Lithuanian and the first Lutheran catechism, both printed in Königsberg in 1547. A university city, home of the Albertina University

The Albertina is a museum in the Innere Stadt (First District) of Vienna, Austria. It houses one of the largest and most important print rooms in the world with approximately 65,000 drawings and approximately 1 million old master prints, as well ...

(founded in 1544), Königsberg developed into an important German intellectual and cultural center, being the residence of Simon Dach

Simon Dach (29 July 1605 – 15 April 1659) was a German lyrical poet and hymnwriter, born in Memel, Duchy of Prussia (now Klaipėda in Lithuania).

Early life

Although brought up in humble circumstances (his father was a poorly paid court int ...

, Immanuel Kant

Immanuel Kant (, , ; 22 April 1724 – 12 February 1804) was a German philosopher and one of the central Enlightenment thinkers. Born in Königsberg, Kant's comprehensive and systematic works in epistemology, metaphysics, ethics, and ...

, Käthe Kollwitz

Käthe Kollwitz ( born as Schmidt; 8 July 1867 – 22 April 1945) was a German artist who worked with painting, printmaking (including etching, lithography and woodcuts) and sculpture. Her most famous art cycles, including ''The Weavers'' and ''T ...

, E. T. A. Hoffmann, David Hilbert

David Hilbert (; ; 23 January 1862 – 14 February 1943) was a German mathematician, one of the most influential mathematicians of the 19th and early 20th centuries. Hilbert discovered and developed a broad range of fundamental ideas in many a ...

, Agnes Miegel

Agnes Miegel (9 March 1879 – 26 October 1964) was a German author, journalist and poet. She is best known for her poems and short stories about East Prussia, but also for the support she gave to the Nazi Party.

Biography

Agnes Miegel was born ...

, Hannah Arendt

Hannah Arendt (, , ; 14 October 1906 – 4 December 1975) was a political philosopher, author, and Holocaust survivor. She is widely considered to be one of the most influential political theorists of the 20th century.

Arendt was born ...

, Michael Wieck

Michael Wieck (19 July 1928 – 27 February 2021) was a German violinist and author. Wieck's memoir, ''Zeugnis vom Untergang Königsbergs'' (Witness to the fall of Königsberg), was published in 1989. In it he relates his and his partly Jewish fami ...

and others.

Königsberg was the easternmost large city in Germany until World War II. Between the wars it was in the exclave

An enclave is a territory (or a small territory apart of a larger one) that is entirely surrounded by the territory of one other state or entity. Enclaves may also exist within territorial waters. ''Enclave'' is sometimes used improperly to deno ...

of East Prussia

East Prussia ; german: Ostpreißen, label=Low Prussian; pl, Prusy Wschodnie; lt, Rytų Prūsija was a province of the Kingdom of Prussia from 1773 to 1829 and again from 1878 (with the Kingdom itself being part of the German Empire from 187 ...

, separated from Germany by Poland. The city was heavily damaged by Allied bombing in 1944 and during the Battle of Königsberg

The Battle of Königsberg, also known as the Königsberg offensive, was one of the last operations of the East Prussian offensive during World War II. In four days of urban warfare, Soviet forces of the 1st Baltic Front and the 3rd Belorussia ...

in 1945, when it was occupied by the Soviet Union. The Potsdam Agreement

The Potsdam Agreement (german: Potsdamer Abkommen) was the agreement between three of the Allies of World War II: the United Kingdom, the United States, and the Soviet Union on 1 August 1945. A product of the Potsdam Conference, it concerned th ...

of 1945 placed it provisionally under Soviet administration, and it was annexed on 9 April 1945. Its Lithuanian population was allowed to remain, but its German population was expelled, and the city was largely repopulated with Russians

, native_name_lang = ru

, image =

, caption =

, population =

, popplace =

118 million Russians in the Russian Federation (2002 ''Winkler Prins'' estimate)

, region1 =

, pop1 ...

and others from the Soviet Union. It was renamed Kaliningrad in 1946, in honour of Soviet leader Mikhail Kalinin

Mikhail Ivanovich Kalinin (russian: link=no, Михаи́л Ива́нович Кали́нин ; 3 June 1946), known familiarly by Soviet citizens as "Kalinych", was a Soviet politician and Old Bolshevik revolutionary. He served as head of s ...

. It is now the capital of Russia's Kaliningrad Oblast

Kaliningrad Oblast (russian: Калинингра́дская о́бласть, translit=Kaliningradskaya oblast') is the westernmost federal subject of Russia. It is a semi-exclave situated on the Baltic Sea. The largest city and administr ...

, an exclave

An enclave is a territory (or a small territory apart of a larger one) that is entirely surrounded by the territory of one other state or entity. Enclaves may also exist within territorial waters. ''Enclave'' is sometimes used improperly to deno ...

bordered in the north by Lithuania

Lithuania (; lt, Lietuva ), officially the Republic of Lithuania ( lt, Lietuvos Respublika, links=no ), is a country in the Baltic region of Europe. It is one of three Baltic states and lies on the eastern shore of the Baltic Sea. Lithuania ...

and in the south by Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populous ...

. In the Final Settlement treaty of 1990, Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

renounced all claim to it.

Name

The first mention of the present-day location in chronicles indicates it as the place of a village of fishermen and hunters. When the Teutonic crusaders began theirBaltic Crusades

The Northern Crusades or Baltic Crusades were Christian colonization and Christianization campaigns undertaken by Catholic Christian military orders and kingdoms, primarily against the pagan Baltic, Finnic and West Slavic peoples around the ...

, they built a wooden fortress, and later a stone fortress, calling it "Conigsberg", which later morphed into "Königsberg". The literal meaning of this is 'King's mountain', in apparent honour of King Ottokar II of Bohemia

Ottokar II ( cs, Přemysl Otakar II.; , in Městec Králové, Bohemia – 26 August 1278, in Dürnkrut, Lower Austria), the Iron and Golden King, was a member of the Přemyslid dynasty who reigned as King of Bohemia from 1253 until his deat ...

, who led one of the Teutonic campaigns. In Polish, the city is called , and in Lithuanian, it is called (with the same meaning as the German name).

History

Sambians

Königsberg was preceded by aSambian

The Sambians were a Old Prussians, Prussian tribe. They inhabited the Sambia Peninsula north of the city of Königsberg (now Kaliningrad). Sambians were located in a coastal territory rich in amber and engaged in trade early on (see Amber Road). ...

, or Old Prussian

Old Prussian was a Western Baltic language belonging to the Baltic branch of the Indo-European languages, which was once spoken by the Old Prussians, the Baltic peoples of the Prussian region. The language is called Old Prussian to avoid con ...

, fort known as ''Twangste'' (''Tuwangste'', ''Tvankste''), meaning 'Oak Forest', as well as several Old Prussian settlements, including the fishing village and port Lipnick, and the farming villages Sakkeim and Trakkeim.

Arrival of the Teutonic Order

During the conquest of the Prussian

During the conquest of the Prussian Sambians

The Sambians were a Prussian tribe. They inhabited the Sambia Peninsula north of the city of Königsberg (now Kaliningrad). Sambians were located in a coastal territory rich in amber and engaged in trade early on (see Amber Road). Therefore, the ...

by the Teutonic Knights

The Order of Brothers of the German House of Saint Mary in Jerusalem, commonly known as the Teutonic Order, is a Catholic religious institution founded as a military society in Acre, Kingdom of Jerusalem. It was formed to aid Christians on ...

in 1255, Twangste was destroyed and replaced with a new fortress known as ''Conigsberg''. This name meant "King’s Hill" ( la, castrum Koningsberg, Mons Regius, Regiomontium), honoring King Ottokar II of Bohemia

Bohemia ( ; cs, Čechy ; ; hsb, Čěska; szl, Czechy) is the westernmost and largest historical region of the Czech Republic. Bohemia can also refer to a wider area consisting of the historical Lands of the Bohemian Crown ruled by the Bohem ...

, who paid for the erection of the first fortress there during the Prussian Crusade

The Prussian Crusade was a series of 13th-century campaigns of Roman Catholic crusaders, primarily led by the Teutonic Knights, to Christianize under duress the pagan Old Prussians. Invited after earlier unsuccessful expeditions against the Pruss ...

. Northwest of this new Königsberg Castle

The Königsberg Castle (german: Königsberger Schloss, russian: Кёнигсбергский замок, Konigsbergskiy zamok) was a castle in Königsberg, Germany (since 1946 Kaliningrad, Russia), and was one of the landmarks of the East Prussian ...

arose an initial settlement, later known as Steindamm, roughly from the Vistula Lagoon

The Vistula Lagoon ( pl, Zalew Wiślany; russian: Калининградский залив, transliterated: ''Kaliningradskiy Zaliv''; german: Frisches Haff; lt, Aistmarės) is a brackish water lagoon on the Baltic Sea roughly 56 miles (90 ...

.

The Teutonic Order used Königsberg to fortify their conquests in Samland and as a base for campaigns against pagan Lithuania

Lithuania (; lt, Lietuva ), officially the Republic of Lithuania ( lt, Lietuvos Respublika, links=no ), is a country in the Baltic region of Europe. It is one of three Baltic states and lies on the eastern shore of the Baltic Sea. Lithuania ...

. Under siege

''Under Siege'' is a 1992 American action thriller film directed by Andrew Davis, written by J. F. Lawton, and starring Steven Seagal as a former Navy SEAL who must stop a group of mercenaries, led by Tommy Lee Jones, after they commandeer the ...

during the Prussian uprisings

The Prussian uprisings were two major and three smaller uprisings by the Old Prussians, one of the Baltic tribes, against the Teutonic Knights that took place in the 13th century during the Prussian Crusade. The crusading military order, sup ...

in 1262–63, Königsberg Castle was relieved by the Master of the Livonian Order

The Livonian Order was an autonomous branch of the Teutonic Order,

formed in 1237. From 1435 to 1561 it was a member of the Livonian Confederation.

History

The order was formed from the remnants of the Livonian Brothers of the Sword after the ...

. Because the initial northwestern settlement was destroyed by the Prussians during the rebellion, rebuilding occurred in the southern valley between the castle hill and the Pregolya River

The Pregolya or Pregola (russian: Прего́ля; german: Pregel; lt, Prieglius; pl, Pregoła) is a river in the Russian Kaliningrad Oblast exclave.

Name

A possible ancient name by Ptolemy of the Pregolya River is Chronos (from Germanic *''h ...

. This new settlement, Altstadt, received Culm rights in 1286. Löbenicht View of Löbenicht from the Pregel, including its church and gymnasium, as well as the nearby Propsteikirche

Löbenicht ( lt, Lyvenikė; pl, Lipnik) was a quarter of central Königsberg, Germany. During the Middle Ages it was the weakest of ...

, a new town directly east of Altstadt between the Pregolya and the Schlossteich, received its own rights in 1300. Medieval Königsberg's third town was Kneiphof

Coat of arms of Kneiphof

Postcard of Kneiphöfsche Langgasse

Reconstruction of Kneiphof in Kaliningrad's museum

Kneiphof (russian: Кнайпхоф; pl, Knipawa; lt, Knypava) was a quarter of central Königsberg (Kaliningrad). During the M ...

, which received town rights in 1327 and was located on an island of the same name in the Pregolya south of Altstadt.

Within the

Within the state of the Teutonic Order

The State of the Teutonic Order (german: Staat des Deutschen Ordens, ; la, Civitas Ordinis Theutonici; lt, Vokiečių ordino valstybė; pl, Państwo zakonu krzyżackiego), also called () or (), was a medieval Crusader state, located in Centr ...

, Königsberg was the residence of the marshal, one of the chief administrators of the military order. The city was also the seat of the Bishopric of Samland

The Bishopric of Samland (Sambia) (german: Bistum Samland, pl, Diecezja sambijska) was a bishopric in Samland (Sambia) in medieval Prussia. It was founded as a Roman Catholic diocese in 1243 by papal legate William of Modena. Its seat was Kö ...

, one of the four diocese

In Ecclesiastical polity, church governance, a diocese or bishopric is the ecclesiastical district under the jurisdiction of a bishop.

History

In the later organization of the Roman Empire, the increasingly subdivided Roman province, pro ...

s into which Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an em ...

had been divided in 1243 by the papal legate

300px, A woodcut showing Henry II of England greeting the pope's legate.

A papal legate or apostolic legate (from the ancient Roman title ''legatus'') is a personal representative of the pope to foreign nations, or to some part of the Catholic ...

, William of Modena

William of Modena ( – 31 March 1251), also known as ''William of Sabina'', ''Guglielmo de Chartreaux'', ''Guglielmo de Savoy'', ''Guillelmus'', was an Italian clergyman and papal diplomat.

. Adalbert of Prague

Adalbert of Prague ( la, Sanctus Adalbertus, cs, svatý Vojtěch, sk, svätý Vojtech, pl, święty Wojciech, hu, Szent Adalbert (Béla); 95623 April 997), known in the Czech Republic, Poland and Slovakia by his birth name Vojtěch ( la, Vo ...

became the main patron saint

A patron saint, patroness saint, patron hallow or heavenly protector is a saint who in Catholicism, Anglicanism, or Eastern Orthodoxy is regarded as the heavenly advocate of a nation, place, craft, activity, class, clan, family, or perso ...

of Königsberg Cathedral

, infobox_width =

, image = Kaliningrad 05-2017 img04 Kant Island.jpg

, image_size =

, alt =

, caption = Front (west side) of the cathedral

, map_type =

, map_ ...

, a landmark of the city located in Kneiphof.

Königsberg joined the Hanseatic League

The Hanseatic League (; gml, Hanse, , ; german: label=Modern German, Deutsche Hanse) was a medieval commercial and defensive confederation of merchant guilds and market towns in Central and Northern Europe. Growing from a few North German to ...

in 1340 and developed into an important port for the south-eastern Baltic region, trading goods throughout Prussia, the Kingdom of Poland

The Kingdom of Poland ( pl, Królestwo Polskie; Latin: ''Regnum Poloniae'') was a state in Central Europe. It may refer to:

Historical political entities

*Kingdom of Poland, a kingdom existing from 1025 to 1031

*Kingdom of Poland, a kingdom exist ...

, and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania

The Grand Duchy of Lithuania was a European state that existed from the 13th century to 1795, when the territory was partitioned among the Russian Empire, the Kingdom of Prussia, and the Habsburg Empire of Austria. The state was founded by Li ...

. The chronicler Peter of Dusburg Peter of Dusburg (german: Peter von Dusburg; la, Petrus de Dusburg; died after 1326), also known as Peter of Duisburg, was a Priest-Brother and chronicler of the Teutonic Knights. He is known for writing the ''Chronicon terrae Prussiae'', which des ...

probably wrote his ''Chronicon terrae Prussiae'' in Königsberg from 1324 to 1330. After the Teutonic Order's victory over pagan Lithuanians

Lithuanians ( lt, lietuviai) are a Baltic ethnic group. They are native to Lithuania, where they number around 2,378,118 people. Another million or two make up the Lithuanian diaspora, largely found in countries such as the United States, Uni ...

in the 1348 Battle of Strėva

The Battle of Strėva, Strebe, or Strawe was fought on 2 February 1348 between the Teutonic Order and the pagan Grand Duchy of Lithuania on the banks of the Strėva River, a right tributary of the Neman River, near present-day Žiežmariai. Chronic ...

, Grand Master Winrich von Kniprode

Winrich von Kniprode was the 22nd Grand Master of the Teutonic Order. He was the longest serving Grand Master, holding the position for 31 years (1351–1382).

Winrich von Kniprode was born in 1310 in Monheim am Rhein near Cologne. He served a ...

established a Cistercian nunnery

Cistercian nuns are female members of the Cistercian Order, a religious order belonging to the Roman Catholic branch of the Catholic Church.

History

The first Cistercian monastery for women, Le Tart Abbey, was established at Tart-l'Abbaye in t ...

in the city. Aspiring students were educated in Königsberg before continuing on to higher education elsewhere, such as Prague

Prague ( ; cs, Praha ; german: Prag, ; la, Praga) is the capital and largest city in the Czech Republic, and the historical capital of Bohemia. On the Vltava river, Prague is home to about 1.3 million people. The city has a temperate ...

or Leipzig

Leipzig ( , ; Upper Saxon: ) is the most populous city in the German state of Saxony. Leipzig's population of 605,407 inhabitants (1.1 million in the larger urban zone) as of 2021 places the city as Germany's eighth most populous, as wel ...

.

Although the knights suffered a crippling defeat in the Battle of Grunwald

The Battle of Grunwald, Battle of Žalgiris or First Battle of Tannenberg was fought on 15 July 1410 during the Polish–Lithuanian–Teutonic War. The alliance of the Crown of the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, led respec ...

, Königsberg remained under the control of the Teutonic Knights throughout the Polish-Lithuanian-Teutonic War. Livonian knights replaced the Prussian branch's garrison at Königsberg, allowing them to participate in the recovery of towns occupied by Władysław II Jagiełło

Jogaila (; 1 June 1434), later Władysław II Jagiełło ()He is known under a number of names: lt, Jogaila Algirdaitis; pl, Władysław II Jagiełło; be, Jahajła (Ягайла). See also: Names and titles of Władysław II Jagiełło. w ...

's troops.

Polish sovereignty

Since 1440, the city was a founding member of the anti-TeutonicPrussian Confederation

The Prussian Confederation (german: Preußischer Bund, pl, Związek Pruski) was an organization formed on 21 February 1440 at Kwidzyn (then officially ''Marienwerder'') by a group of 53 nobles and clergy and 19 cities in Prussia, to oppose the a ...

. In 1454 the Confederation rebelled against the Teutonic Knights and asked the Polish King Casimir IV Jagiellon

Casimir IV (in full Casimir IV Andrew Jagiellon; pl, Kazimierz IV Andrzej Jagiellończyk ; Lithuanian: ; 30 November 1427 – 7 June 1492) was Grand Duke of Lithuania from 1440 and King of Poland from 1447, until his death. He was one of the ...

to incorporate Prussia into the Kingdom of Poland

The Kingdom of Poland ( pl, Królestwo Polskie; Latin: ''Regnum Poloniae'') was a state in Central Europe. It may refer to:

Historical political entities

*Kingdom of Poland, a kingdom existing from 1025 to 1031

*Kingdom of Poland, a kingdom exist ...

, to which the King agreed and signed an act of incorporation. The local mayor pledged allegiance to the Polish King during the incorporation in March 1454. This marked the beginning of the Thirteen Years' War (1454–1466)

The Thirteen Years' War (german: Dreizehnjähriger Krieg; pl, wojna trzynastoletnia), also called the War of the Cities, was a conflict fought in 1454–1466 between the Prussian Confederation, allied with the Crown of the Kingdom of Poland, a ...

between the State of the Teutonic Order

The State of the Teutonic Order (german: Staat des Deutschen Ordens, ; la, Civitas Ordinis Theutonici; lt, Vokiečių ordino valstybė; pl, Państwo zakonu krzyżackiego), also called () or (), was a medieval Crusader state, located in Centr ...

and the Kingdom of Poland. The city, known in Polish as ''Królewiec'', became the seat of the short-lived Królewiec Voivodeship. King Casimir IV authorized the city to mint Polish coins. While Königsberg/Królewiec's three towns initially joined the rebellion, Altstadt and Löbenicht soon rejoined the Teutonic Knights and defeated Kneiphof (Knipawa) in 1455. Grand Master Ludwig von Erlichshausen

Ludwig von Erlichshausen (1410–1467) was the 31st Grand Master of the Teutonic Knights, serving from 1449/1450 to 1467.

As did his uncle and predecessor Konrad von Erlichshausen, Ludwig came from Ellrichshausen in Swabia, now part of Satteldo ...

fled from the crusaders' capital at Castle Marienburg (Malbork) to Königsberg in 1457; the city's magistrate presented Erlichshausen with a barrel of beer out of compassion.

Following the Second Peace of Thorn (1466)

The Peace of Thorn or Toruń of 1466, also known as the Second Peace of Thorn or Toruń ( pl, drugi pokój toruński; german: Zweiter Friede von Thorn), was a peace treaty signed in the Hanseatic city of Thorn (Toruń) on 19 October 1466 betwee ...

, which ended the Thirteen Years' War, Königsberg became the new capital of the reduced monastic state, which became a part of the Kingdom of Poland as a fief. The grand masters took over the quarters of the marshal. During the Polish-Teutonic War (1519–1521), Königsberg was unsuccessfully besieged by Polish forces led by Grand Crown Hetman Mikołaj Firlej. The city itself opposed the Teutonic Knights' war against Poland and demanded peace.

Duchy of Prussia

Through the preachings of the Bishop of Samland,Georg von Polenz

George of Polentz (born: ; died: 1550 in Balga) was bishop of Samland and Pomesania and a lawyer. He was the first Lutheran bishop and also a Protestant reformer.

Polentz was a member of an old Saxon noble family. He studied law in Bologna ...

, Königsberg became predominantly Lutheran

Lutheranism is one of the largest branches of Protestantism, identifying primarily with the theology of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German monk and reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practice of the Catholic Church launched th ...

during the Protestant Reformation

The Reformation (alternatively named the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation) was a major movement within Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the Catholic Church and in ...

. After summoning a quorum

A quorum is the minimum number of members of a deliberative assembly (a body that uses parliamentary procedure, such as a legislature) necessary to conduct the business of that group. According to ''Robert's Rules of Order Newly Revised'', the ...

of the Knights to Königsberg, Grand Master Albert of Brandenburg

Cardinal Albert of Brandenburg (german: Albrecht von Brandenburg; 28 June 149024 September 1545) was a German cardinal, elector, Archbishop of Mainz from 1514 to 1545, and Archbishop of Magdeburg from 1513 to 1545.

Biography Early career

Bo ...

(a member of the House of Hohenzollern

The House of Hohenzollern (, also , german: Haus Hohenzollern, , ro, Casa de Hohenzollern) is a German royal (and from 1871 to 1918, imperial) dynasty whose members were variously princes, Prince-elector, electors, kings and emperors of Hohenzol ...

) secularised the Teutonic Knights' remaining territories in Prussia in 1525 and converted to Lutheranism. By paying feudal homage to his uncle, King Sigismund I of Poland

Sigismund I the Old ( pl, Zygmunt I Stary, lt, Žygimantas II Senasis; 1 January 1467 – 1 April 1548) was King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania from 1506 until his death in 1548. Sigismund I was a member of the Jagiellonian dynasty, the ...

, Albert became the first duke of the new Duchy of Prussia

The Duchy of Prussia (german: Herzogtum Preußen, pl, Księstwo Pruskie, lt, Prūsijos kunigaikštystė) or Ducal Prussia (german: Herzogliches Preußen, link=no; pl, Prusy Książęce, link=no) was a duchy in the Prussia (region), region of P ...

, a fief of Poland.

While the Prussian estates quickly allied with the duke, the Prussian peasantry would only swear allegiance to Albert in person at Königsberg, seeking the duke's support against the oppressive nobility. After convincing the rebels to lay down their arms, Albert had several of their leaders executed.

Königsberg, the capital, became one of the biggest cities and ports of Ducal Prussia, having considerable autonomy, a separate

While the Prussian estates quickly allied with the duke, the Prussian peasantry would only swear allegiance to Albert in person at Königsberg, seeking the duke's support against the oppressive nobility. After convincing the rebels to lay down their arms, Albert had several of their leaders executed.

Königsberg, the capital, became one of the biggest cities and ports of Ducal Prussia, having considerable autonomy, a separate parliament

In modern politics, and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

and currency. While German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

** Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ge ...

continued to be the official language, the city served as a vibrant center of publishing in both Polish

Polish may refer to:

* Anything from or related to Poland, a country in Europe

* Polish language

* Poles

Poles,, ; singular masculine: ''Polak'', singular feminine: ''Polka'' or Polish people, are a West Slavic nation and ethnic group, w ...

and Lithuanian. The city flourished through the export of wheat

Wheat is a grass widely cultivated for its seed, a cereal grain that is a worldwide staple food. The many species of wheat together make up the genus ''Triticum'' ; the most widely grown is common wheat (''T. aestivum''). The archaeologi ...

, timber

Lumber is wood that has been processed into dimensional lumber, including beams and planks or boards, a stage in the process of wood production. Lumber is mainly used for construction framing, as well as finishing (floors, wall panels, wi ...

, hemp

Hemp, or industrial hemp, is a botanical class of ''Cannabis sativa'' cultivars grown specifically for industrial or medicinal use. It can be used to make a wide range of products. Along with bamboo, hemp is among the fastest growing plants o ...

, and furs

Fur is a thick growth of hair that covers the skin of mammals. It consists of a combination of oily guard hair on top and thick underfur beneath. The guard hair keeps moisture from reaching the skin; the underfur acts as an insulating blanket t ...

, as well as pitch, tar

Tar is a dark brown or black viscous liquid of hydrocarbons and free carbon, obtained from a wide variety of organic materials through destructive distillation. Tar can be produced from coal, wood, petroleum, or peat. "a dark brown or black bit ...

, and fly ash

Fly ash, flue ash, coal ash, or pulverised fuel ash (in the UK) plurale tantum: coal combustion residuals (CCRs)is a coal combustion product that is composed of the particulates (fine particles of burned fuel) that are driven out of coal-fired ...

.

Königsberg was one of the few Baltic ports regularly visited by more than one hundred ships annually in the latter 16th century, along with Gdańsk

Gdańsk ( , also ; ; csb, Gduńsk;Stefan Ramułt, ''Słownik języka pomorskiego, czyli kaszubskiego'', Kraków 1893, Gdańsk 2003, ISBN 83-87408-64-6. , Johann Georg Theodor Grässe, ''Orbis latinus oder Verzeichniss der lateinischen Benen ...

and Riga

Riga (; lv, Rīga , liv, Rīgõ) is the capital and largest city of Latvia and is home to 605,802 inhabitants which is a third of Latvia's population. The city lies on the Gulf of Riga at the mouth of the Daugava river where it meets the Ba ...

. The University of Königsberg

The University of Königsberg (german: Albertus-Universität Königsberg) was the university of Königsberg in East Prussia. It was founded in 1544 as the world's second Protestant academy (after the University of Marburg) by Duke Albert of Prussi ...

, founded by Duke Albert in 1544 and receiving token royal approval from King Sigismund II Augustus

Sigismund II Augustus ( pl, Zygmunt II August, lt, Žygimantas Augustas; 1 August 1520 – 7 July 1572) was King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania, the son of Sigismund I the Old, whom Sigismund II succeeded in 1548. He was the first ruler ...

in 1560, became a center of Protestant teaching. The university had a profound impact on the development of Lithuanian culture, and several important Lithuanian writers attended the ''Albertina'' (see ''Lithuanians'' section below). Poles, including several notable figures, were also among the staff and students of the university (see ''Poles'' section below). The university was also the preferred educational institution of the Baltic German

Baltic Germans (german: Deutsch-Balten or , later ) were ethnic German inhabitants of the eastern shores of the Baltic Sea, in what today are Estonia and Latvia. Since their coerced resettlement in 1939, Baltic Germans have markedly declined ...

nobility.

The capable Duke Albert was succeeded by his feeble-minded son, Albert Frederick

Albert Frederick (german: Albrecht Friedrich; pl, Albrecht Fryderyk; 7 May 1553 – 27 August 1618) was the Duke of Prussia, from 1568 until his death. He was a son of Albert of Prussia and Anna Marie of Brunswick-Lüneburg. He was the secon ...

. Anna, daughter of Albert Frederick, married Elector John Sigismund of Brandenburg

Brandenburg (; nds, Brannenborg; dsb, Bramborska ) is a states of Germany, state in the northeast of Germany bordering the states of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, Lower Saxony, Saxony-Anhalt, and Saxony, as well as the country of Poland. With an ar ...

, who was granted the right of succession to Prussia on Albert Frederick's death in 1618. From this time the Electors of Brandenburg

This article lists the Margraves and Electors of Brandenburg during the period of time that Brandenburg was a constituent state of the Holy Roman Empire.

The Mark, or ''March'', of Brandenburg was one of the primary constituent states of the Hol ...

, the rulers of Brandenburg-Prussia

Brandenburg-Prussia (german: Brandenburg-Preußen; ) is the historiographic denomination for the early modern realm of the Brandenburgian Hohenzollerns between 1618 and 1701. Based in the Electorate of Brandenburg, the main branch of the Hohenz ...

, governed the Duchy of Prussia.

Brandenburg-Prussia

When Imperial and thenSwedish

Swedish or ' may refer to:

Anything from or related to Sweden, a country in Northern Europe. Or, specifically:

* Swedish language, a North Germanic language spoken primarily in Sweden and Finland

** Swedish alphabet, the official alphabet used by ...

armies overran Brandenburg during the Thirty Years' War

The Thirty Years' War was one of the longest and most destructive conflicts in European history

The history of Europe is traditionally divided into four time periods: prehistoric Europe (prior to about 800 BC), classical antiquity (80 ...

of 1618–1648, the Hohenzollern court fled to Königsberg. On 1 November 1641, Elector Frederick William persuaded the Prussian diet to accept an excise tax

file:Lincoln Beer Stamp 1871.JPG, upright=1.2, 1871 U.S. Revenue stamp for 1/6 barrel of beer. Brewers would receive the stamp sheets, cut them into individual stamps, cancel them, and paste them over the Bunghole, bung of the beer barrel so when ...

. In the Treaty of Königsberg of January 1656, the elector recognised his Duchy of Prussia as a fief of Sweden. In the Treaty of Wehlau

The Treaty of Bromberg (, Latin: Pacta Bydgostensia) or Treaty of Bydgoszcz was a treaty between John II Casimir of Poland and Elector Frederick William of Brandenburg-Prussia that was ratified at Bromberg (Bydgoszcz) on 6 November 1657. The trea ...

in 1657, however, he negotiated the release of Prussia from Polish sovereignty in return for an alliance with Poland. The 1660 Treaty of Oliva

The Treaty or Peace of Oliva of 23 April (OS)/3 May (NS) 1660Evans (2008), p.55 ( pl, Pokój Oliwski, sv, Freden i Oliva, german: Vertrag von Oliva) was one of the peace treaties ending the Second Northern War (1655-1660).Frost (2000), p.183 ...

confirmed Prussian independence from both Poland and Sweden.

In 1661 Frederick William informed the Prussian diet that he possessed ''jus supremi et absoluti domini'', and that the

In 1661 Frederick William informed the Prussian diet that he possessed ''jus supremi et absoluti domini'', and that the Prussian Landtag

The Landtag of Prussia (german: Preußischer Landtag) was the representative assembly of the Kingdom of Prussia implemented in 1849, a bicameral legislature consisting of the upper House of Lords (''Herrenhaus'') and the lower House of Represent ...

could convene with his permission. The Königsberg burghers, led by Hieronymus Roth

Hieronymus Roth (1606–1678) was a lawyer and alderman of Königsberg (Polish: ''Królewiec'', modern day Kaliningrad) who led the city burghers in opposition to Elector Frederick William.

In the Treaty of Oliva of 1660 the Elector had managed ...

of Kneiphof, opposed "the Great Elector's" absolutist claims, and actively rejected the Treaties of Wehlau and Oliva, seeing Prussia as "indisputably contained within the territory of the Polish Crown". Delegations from the city's burghers went to the Polish king, John II Casimir Vasa

John II Casimir ( pl, Jan II Kazimierz Waza; lt, Jonas Kazimieras Vaza; 22 March 1609 – 16 December 1672) was King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania from 1648 until his abdication in 1668 as well as titular King of Sweden from 1648 ...

, who initially promised aid, but then failed to follow through. The town's residents attacked the elector's troops while local Lutheran priests held masses for the Polish king and for the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, formally known as the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, and, after 1791, as the Commonwealth of Poland, was a bi-confederal state, sometimes called a federation, of Crown of the Kingdom of ...

. However, Frederick William succeeded in imposing his authority after arriving with 3,000 troops in October 1662 and training his artillery on the town. Refusing to request mercy, Roth went to prison in Peitz

Peitz (; Lower Sorbian Picnjo) is a town in the district of Spree-Neiße, in Lower Lusatia, Brandenburg, Germany.

Overview

It is situated 13 km northeast of Cottbus. Surrounded by freshwater lakes, it is well known for its fishing industry. ...

until his death in 1678.

The Prussian estates which swore fealty to Frederick William in Königsberg on 18 October 1663 refused the elector's requests for military funding, and Colonel Christian Ludwig von Kalckstein Christian Ludwig von Kalckstein (1630 – 8 November 1672) was a Prussian count, colonel, and politician who was executed for treason.

Biography

Kalckstein was the son of Count Albrecht von Kalckstein, a strong critic of Frederick William, El ...

sought assistance from neighbouring Poland. After the elector's agents had abducted Kalckstein, he was executed in 1672. The Prussian estates' submission to Frederick William followed; in 1673 and 1674 the elector received taxes not granted by the estates and Königsberg received a garrison without the estates' consent. The economic and political weakening of Königsberg strengthened the power of the Junker

Junker ( da, Junker, german: Junker, nl, Jonkheer, en, Yunker, no, Junker, sv, Junker ka, იუნკერი (Iunkeri)) is a noble honorific, derived from Middle High German ''Juncherre'', meaning "young nobleman"Duden; Meaning of Junke ...

nobility within Prussia.

Königsberg long remained a center of Lutheran resistance to Calvinism

Calvinism (also called the Reformed Tradition, Reformed Protestantism, Reformed Christianity, or simply Reformed) is a major branch of Protestantism that follows the theological tradition and forms of Christian practice set down by John Cal ...

within Brandenburg-Prussia

Brandenburg-Prussia (german: Brandenburg-Preußen; ) is the historiographic denomination for the early modern realm of the Brandenburgian Hohenzollerns between 1618 and 1701. Based in the Electorate of Brandenburg, the main branch of the Hohenz ...

; Frederick William forced the city to accept Calvinist citizens and property-holders in 1668.

Kingdom of Prussia

By the act of coronation in

By the act of coronation in Königsberg Castle

The Königsberg Castle (german: Königsberger Schloss, russian: Кёнигсбергский замок, Konigsbergskiy zamok) was a castle in Königsberg, Germany (since 1946 Kaliningrad, Russia), and was one of the landmarks of the East Prussian ...

on 18 January 1701, Frederick William's son, Elector Frederick III, became Frederick I Frederick I may refer to:

* Frederick of Utrecht or Frederick I (815/16–834/38), Bishop of Utrecht.

* Frederick I, Duke of Upper Lorraine (942–978)

* Frederick I, Duke of Swabia (1050–1105)

* Frederick I, Count of Zoll ...

, King in Prussia

King ''in'' Prussia (German: ''König in Preußen'') was a title used by the Prussian kings (also in personal union Electors of Brandenburg) from 1701 to 1772. Subsequently, they used the title King ''of'' Prussia (''König von Preußen'').

Th ...

. The elevation of the Duchy of Prussia to the Kingdom of Prussia

The Kingdom of Prussia (german: Königreich Preußen, ) was a German kingdom that constituted the state of Prussia between 1701 and 1918.Marriott, J. A. R., and Charles Grant Robertson. ''The Evolution of Prussia, the Making of an Empire''. Re ...

was possible because the Hohenzollerns' authority in Prussia was independent of Poland and the Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a Polity, political entity in Western Europe, Western, Central Europe, Central, and Southern Europe that developed during the Early Middle Ages and continued until its Dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire, dissolution i ...

. Since "Kingdom of Prussia" was increasingly used to designate all of the Hohenzollern lands, former ducal Prussia became known as the Province of Prussia

The Province of Prussia (; ; pl, Prowincja Prusy; csb, Prowincjô Prësë) was a province of Prussia from 1829 to 1878. Prussia was established as a province of the Kingdom of Prussia in 1829 from the provinces of East Prussia and West Prussia ...

(1701–1773), with Königsberg as its capital. However, Berlin and Potsdam

Potsdam () is the capital and, with around 183,000 inhabitants, largest city of the German state of Brandenburg. It is part of the Berlin/Brandenburg Metropolitan Region. Potsdam sits on the River Havel, a tributary of the Elbe, downstream of B ...

in Brandenburg were the main residences of the Prussian kings.

The city was wracked by plague

Plague or The Plague may refer to:

Agriculture, fauna, and medicine

*Plague (disease), a disease caused by ''Yersinia pestis''

* An epidemic of infectious disease (medical or agricultural)

* A pandemic caused by such a disease

* A swarm of pes ...

and other illnesses from September 1709 to April 1710, losing 9,368 people, or roughly a quarter of its populace. On 13 June 1724, Altstadt, Kneiphof

Coat of arms of Kneiphof

Postcard of Kneiphöfsche Langgasse

Reconstruction of Kneiphof in Kaliningrad's museum

Kneiphof (russian: Кнайпхоф; pl, Knipawa; lt, Knypava) was a quarter of central Königsberg (Kaliningrad). During the M ...

, and Löbenicht View of Löbenicht from the Pregel, including its church and gymnasium, as well as the nearby Propsteikirche

Löbenicht ( lt, Lyvenikė; pl, Lipnik) was a quarter of central Königsberg, Germany. During the Middle Ages it was the weakest of ...

amalgamated

Amalgamation is the process of combining or uniting multiple entities into one form.

Amalgamation, amalgam, and other derivatives may refer to:

Mathematics and science

* Amalgam (chemistry), the combination of mercury with another metal

**Pan ama ...

to formally create the larger city Königsberg. Suburbs that subsequently were annexed to Königsberg include Sackheim, Rossgarten Rossgarten's marketplace, the Roßgärter Markt

Rossgarten (german: Roßgarten) was a quarter of northeastern Königsberg, Germany. It was also occasionally known as Altrossgarten (''Altroßgarten'') to differentiate it from Neurossgarten in north ...

, and Tragheim.

Russian Empire

During theSeven Years' War

The Seven Years' War (1756–1763) was a global conflict that involved most of the European Great Powers, and was fought primarily in Europe, the Americas, and Asia-Pacific. Other concurrent conflicts include the French and Indian War (1754� ...

of 1756 to 1763 Imperial Russian

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War. The ...

troops occupied eastern Prussia at the beginning of 1758. On 31 December 1757, Empress Elizabeth I

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was Queen of England and Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. Elizabeth was the last of the five House of Tudor monarchs and is sometimes referred to as the "Virgin Queen".

El ...

of Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia, Northern Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the ...

issued an ''ukase

In Imperial Russia, a ukase () or ukaz (russian: указ ) was a proclamation of the tsar, government, or a religious leader (patriarch) that had the force of law. "Edict" and "decree" are adequate translations using the terminology and concepts ...

'' about the incorporation of Königsberg into Russia. On 24 January 1758, the leading burghers of Königsberg submitted to Elizabeth. Under the terms of the Treaty of Saint Petersburg (signed 5 May 1762) Russia exited the Seven Years' War, the Russian army abandoned eastern Prussia, and the city reverted to Prussian control.

Kingdom of Prussia after 1773

After the First Partition of Poland in 1772, Königsberg became the capital of the newly formedprovince of East Prussia

East Prussia ; german: Ostpreißen, label=Low Prussian; pl, Prusy Wschodnie; lt, Rytų Prūsija was a province of the Kingdom of Prussia from 1773 to 1829 and again from 1878 (with the Kingdom itself being part of the German Empire from 1871 ...

in 1773, which replaced the Province of Prussia in 1773. By 1800 the city was approximately five miles () in circumference and had 60,000 inhabitants, including a military garrison of 7,000, making it one of the most populous German cities of the time.

After Prussia's defeat at the hands of Napoleon Bonaparte

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

in 1806 during the War of the Fourth Coalition

The Fourth Coalition fought against Napoleon's French Empire and were defeated in a war spanning 1806–1807. The main coalition partners were Prussia and Russia with Saxony, Sweden, and Great Britain also contributing. Excluding Prussia, s ...

and the subsequent occupation of Berlin, King Frederick William III of Prussia

Frederick William III (german: Friedrich Wilhelm III.; 3 August 1770 – 7 June 1840) was King of Prussia from 16 November 1797 until his death in 1840. He was concurrently Elector of Brandenburg in the Holy Roman Empire until 6 August 1806, wh ...

fled with his court from Berlin to Königsberg. The city was a centre for political resistance to Napoleon. In order to foster liberalism

Liberalism is a political and moral philosophy based on the rights of the individual, liberty, consent of the governed, political equality and equality before the law."political rationalism, hostility to autocracy, cultural distaste for c ...

and nationalism

Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the State (polity), state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a in-group and out-group, group of peo ...

among the Prussian middle class, the "League of Virtue" was founded in Königsberg in April 1808. The French forced its dissolution in December 1809, but its ideals were continued by the ''Turnbewegung'' of Friedrich Ludwig Jahn

(11August 177815October 1852) was a German gymnastics educator and nationalist whose writing is credited with the founding of the German gymnastics (Turner) movement as well as influencing the German Campaign of 1813, during which a coalition of ...

in Berlin. Königsberg officials, such as Johann Gottfried Frey, formulated much of Stein

Stein is a German, Yiddish and Norwegian word meaning "stone" and "pip" or "kernel". It stems from the same Germanic root as the English word stone. It may refer to:

Places In Austria

* Stein, a neighbourhood of Krems an der Donau, Lower Aust ...

's 1808 ''Städteordnung'', or new order for urban communities, which emphasised self-administration for Prussian towns. The East Prussian ''Landwehr

''Landwehr'', or ''Landeswehr'', is a German language term used in referring to certain national army, armies, or militias found in nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Europe. In different context it refers to large-scale, low-strength fortif ...

'' was organised from the city after the Convention of Tauroggen

The Convention of Tauroggen was an armistice signed 30 December 1812 at Tauroggen (now Tauragė, Lithuania) between General Ludwig Yorck on behalf of his Prussian troops and General Hans Karl von Diebitsch of the Imperial Russian Army. Yorck's a ...

.

In 1819 Königsberg had a population of 63,800. It served as the capital of the united Province of Prussia

The Province of Prussia (; ; pl, Prowincja Prusy; csb, Prowincjô Prësë) was a province of Prussia from 1829 to 1878. Prussia was established as a province of the Kingdom of Prussia in 1829 from the provinces of East Prussia and West Prussia ...

from 1824 to 1878, when East Prussia was merged with West Prussia

The Province of West Prussia (german: Provinz Westpreußen; csb, Zôpadné Prësë; pl, Prusy Zachodnie) was a province of Prussia from 1773 to 1829 and 1878 to 1920. West Prussia was established as a province of the Kingdom of Prussia in 177 ...

. It was also the seat of the Regierungsbezirk Königsberg, an administrative subdivision.

Led by the provincial president Theodor von Schön

Heinrich Theodor von Schön (20 January 1773 – 23 July 1856) was a Prussian statesman who assisted in the liberal reforms in Prussia during the Napoleonic Wars.

Biography

Schön was born in Schreitlauken, Tilsit district, East Prussia (now Še ...

and the ''Königsberger Volkszeitung'' newspaper, Königsberg was a stronghold of liberalism

Liberalism is a political and moral philosophy based on the rights of the individual, liberty, consent of the governed, political equality and equality before the law."political rationalism, hostility to autocracy, cultural distaste for c ...

against the conservative government of King Frederick William IV

Frederick William IV (german: Friedrich Wilhelm IV.; 15 October 17952 January 1861), the eldest son and successor of Frederick William III of Prussia, reigned as King of Prussia from 7 June 1840 to his death on 2 January 1861. Also referred to ...

. During the revolution of 1848

The Revolutions of 1848, known in some countries as the Springtime of the Peoples or the Springtime of Nations, were a series of political upheavals throughout Europe starting in 1848. It remains the most widespread revolutionary wave in Europea ...

, there were 21 episodes of public unrest in the city; major demonstrations were suppressed. Königsberg became part of the German Empire

The German Empire (),Herbert Tuttle wrote in September 1881 that the term "Reich" does not literally connote an empire as has been commonly assumed by English-speaking people. The term literally denotes an empire – particularly a hereditary ...

in 1871 during the Prussian-led unification of Germany

The unification of Germany (, ) was the process of building the modern German nation state with federalism, federal features based on the concept of Lesser Germany (one without multinational Austria), which commenced on 18 August 1866 with ad ...

. A sophisticated-for-its-time series of fortifications around the city that included fifteen forts was completed in 1888.

The extensive Prussian Eastern Railway

The Prussian Eastern Railway (german: Preußische Ostbahn) was a railway in the Kingdom of Prussia and later Germany until 1918. Its main route, approximately long, connected the capital, Berlin, with the cities of Danzig (now Gdańsk, Poland) ...

linked the city to Breslau, Thorn

Thorn(s) or The Thorn(s) may refer to:

Botany

* Thorns, spines, and prickles, sharp structures on plants

* ''Crataegus monogyna'', or common hawthorn, a plant species

Comics and literature

* Rose and Thorn, the two personalities of two DC Com ...

, Insterburg

Chernyakhovsk (russian: Черняхо́вск) – known prior to 1946 by its German name of (Old Prussian: Instrāpils, lt, Įsrutis; pl, Wystruć) – is a town in the Kaliningrad Oblast of Russia, where it is the administrative center of C ...

, Eydtkuhnen, Tilsit

Sovetsk (russian: Сове́тск; german: Tilsit; Old Prussian: ''Tilzi''; lt, Tilžė; pl, Tylża) is a town in Kaliningrad Oblast, Russia, located on the south bank of the Neman River which forms the border with Lithuania.

Geography

Sov ...

, and Pillau

Baltiysk (russian: Балти́йск; german: Pillau; Old Prussian: ''Pillawa''; pl, Piława; lt, Piliava; Yiddish: פּילאַווע, ''Pilave'') is a seaport town and the administrative center of Baltiysky District in Kaliningrad Oblast, Ru ...

. In 1860 the railway connecting Berlin

Berlin ( , ) is the capital and largest city of Germany by both area and population. Its 3.7 million inhabitants make it the European Union's most populous city, according to population within city limits. One of Germany's sixteen constitue ...

with St. Petersburg

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, Санкт-Петербург, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ˈsankt pʲɪtʲɪrˈburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914–1924) and later Leningrad (1924–1991), i ...

was completed and increased Königsberg's commerce. Extensive electric tramways were in operation by 1900; and regular steamers plied the waterways to Memel, Tapiau

Gvardeysk ( rus, Гварде́йск, p=ɡvɐrˈdʲejsk, a=RU-Gvardejsk.ogg), known prior to 1946 by its German name ( lt, Tepliava; pl, Tapiawa/Tapiewo), is a town and the administrative center of Gvardeysky District in Kaliningrad Oblast, Rus ...

and Labiau, Cranz, Tilsit, and Danzig. The completion of a canal to Pillau in 1901 increased the trade of Russian grain in Königsberg, but, like much of eastern Germany, the city's economy was generally in decline. The city was an important entrepôt

An ''entrepôt'' (; ) or transshipment port is a port, city, or trading post where merchandise may be imported, stored, or traded, usually to be exported again. Such cities often sprang up and such ports and trading posts often developed into co ...

for Scottish herring. in 1904 the export peaked at more than 322 thousand barrels. By 1900 the city's population had grown to 188,000, with a 9,000-strong military garrison. By 1914 Königsberg had a population of 246,000; Jew

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""Th ...

s flourished in the culturally pluralistic city.

Weimar Republic

Central Powers

The Central Powers, also known as the Central Empires,german: Mittelmächte; hu, Központi hatalmak; tr, İttifak Devletleri / ; bg, Централни сили, translit=Tsentralni sili was one of the two main coalitions that fought in ...

in World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, Imperial Germany was replaced with the democratic Weimar Republic

The Weimar Republic (german: link=no, Weimarer Republik ), officially named the German Reich, was the government of Germany from 1918 to 1933, during which it was a constitutional federal republic for the first time in history; hence it is al ...

. The Kingdom of Prussia ended with the abdication of the Hohenzollern monarch, Wilhelm II

Wilhelm II (Friedrich Wilhelm Viktor Albert; 27 January 18594 June 1941) was the last German Emperor (german: Kaiser) and King of Prussia, reigning from 15 June 1888 until his abdication on 9 November 1918. Despite strengthening the German Empir ...

, and the kingdom was succeeded by the Free State of Prussia

The Free State of Prussia (german: Freistaat Preußen, ) was one of the constituent states of Germany from 1918 to 1947. The successor to the Kingdom of Prussia after the defeat of the German Empire in World War I, it continued to be the domin ...

. Königsberg and East Prussia

East Prussia ; german: Ostpreißen, label=Low Prussian; pl, Prusy Wschodnie; lt, Rytų Prūsija was a province of the Kingdom of Prussia from 1773 to 1829 and again from 1878 (with the Kingdom itself being part of the German Empire from 187 ...

, however, were separated from the rest of Weimar Germany following the restoration of independent Poland and the creation of the so-called Polish Corridor

The Polish Corridor (german: Polnischer Korridor; pl, Pomorze, Polski Korytarz), also known as the Danzig Corridor, Corridor to the Sea or Gdańsk Corridor, was a territory located in the region of Pomerelia (Pomeranian Voivodeship, eastern ...

. Due to the isolated geographical situation after World War I the German Government supported a lot of large infrastructure projects: 1919 Airport "Devenau" (the first civil airport in Germany), 1920 "Deutsche Ostmesse" (a new German trade fare; including new hotels and radio station), 1929 reconstruction of the railway system including the new central railway station and 1930 opening of the North station.

Nazi Germany

In 1932 the local paramilitary SA had already started to terrorise their political opponents. On the night of 31 July 1932 there was a bomb attack on the headquarters of theSocial Democrats

Social democracy is a political, social, and economic philosophy within socialism that supports political and economic democracy. As a policy regime, it is described by academics as advocating economic and social interventions to promote so ...

in Königsberg, the Otto-Braun-House. The Communist politician Gustav Sauf was killed, and the executive editor of the Social Democrat ''"Königsberger Volkszeitung"'', Otto Wyrgatsch, and the German People's Party

The German People's Party (German: , or DVP) was a liberal party during the Weimar Republic that was the successor to the National Liberal Party of the German Empire. A right-liberal, or conservative-liberal political party, it represented politi ...

politician Max von Bahrfeldt were severely injured. Members of the Reichsbanner were attacked and the local Reichsbanner Chairman of Lötzen (Giżycko

Giżycko (former pl, Lec or ''Łuczany''; ; lt, Leičių pilis) is a town in northeastern Poland with 28,597 inhabitants as of December 2021. It is situated between Lake Kisajno and Lake Niegocin in the region of Masuria, and has been withi ...

), Kurt Kotzan, was murdered on 6 August 1932.

Following Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

's coming to power, Nazis confiscated Jewish shops and, as in the rest of Germany, a public book burning was organised, accompanied by anti-Semitic speeches in May 1933 at the Trommelplatz square. Street names and monuments of Jewish origin were removed, and signs such as "Jews are not welcomed in hotels" started appearing. As part of the state-wide "aryanisation" of the civil service Jewish academics were ejected from the university.

In July 1934 Hitler made a speech in the city in front of 25,000 supporters.Janusz Jasinski, Historia Krolewca, 1994, page 249 In 1933 the NSDAP alone received 54% of votes in the city. After the Nazis took power in Germany, opposition politicians were persecuted and newspapers were banned. The Otto-Braun-House was requisitioned and became the headquarters of the SA, which used the house to imprison and torture opponents. Walter Schütz

Walter Schütz (25 October 1897 – between 27 and 29 March 1933) was a German communist politician.

Biography

Schütz was born in Wehlau (today Znamensk, Russia), where he attended school. He was trained as a machine fitter and worked at t ...

, a communist member of the Reichstag, was murdered there. Many who would not co-operate with the rulers of Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

were sent to concentration camps

Internment is the imprisonment of people, commonly in large groups, without charges or intent to file charges. The term is especially used for the confinement "of enemy citizens in wartime or of terrorism suspects". Thus, while it can simply ...

and held prisoner there until their death or liberation.

Wehrmacht

The ''Wehrmacht'' (, ) were the unified armed forces of Nazi Germany from 1935 to 1945. It consisted of the ''Heer'' (army), the ''Kriegsmarine'' (navy) and the ''Luftwaffe'' (air force). The designation "''Wehrmacht''" replaced the previous ...

designated Königsberg as the Headquarters for Wehrkreis I

The military districts, also known in some English-language publications by their German name as Wehrkreise (singular: ''Wehrkreis''), were administrative territorial units in Nazi Germany before and during World War II. The task of military distr ...

(under the command of General der Artillerie Albert Wodrig __NOTOC__

Albert Wodrig (16 July 1883 – 31 October 1972) was a German general during World War II who commanded the XXVI. Corps. He was a recipient of the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross of Nazi Germany.

Awards and decorations

* Knight's Cr ...

), which took in all of East Prussia

East Prussia ; german: Ostpreißen, label=Low Prussian; pl, Prusy Wschodnie; lt, Rytų Prūsija was a province of the Kingdom of Prussia from 1773 to 1829 and again from 1878 (with the Kingdom itself being part of the German Empire from 187 ...

. According to the census of May 1939, Königsberg had a population of 372,164.

Persecution of Jews under the Nazi regime

Prior to the Nazi era, Königsberg was home to a third of East Prussia's 13,000 Jews. Under Nazi rule, the Polish and Jewish minorities were classified as ''Untermensch

''Untermensch'' (, ; plural: ''Untermenschen'') is a Nazi term for non- Aryan "inferior people" who were often referred to as "the masses from the East", that is Jews, Roma, and Slavs (mainly ethnic Poles, Serbs, and later also Russians). The ...