Kotou on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

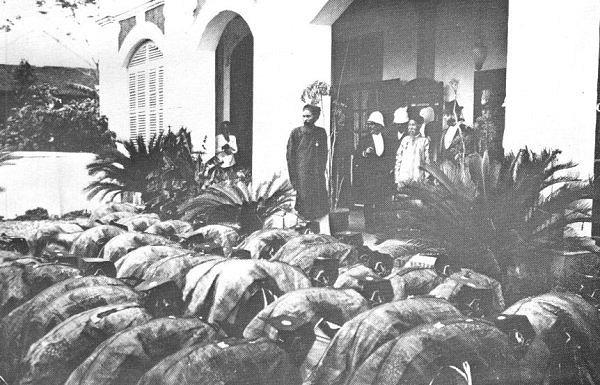

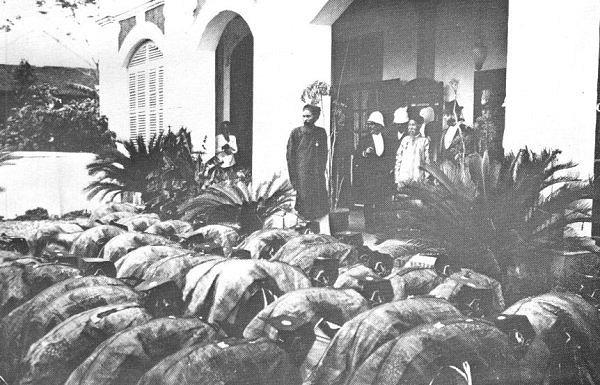

A kowtow is the act of deep respect shown by prostration, that is, kneeling and bowing so low as to have one's head touching the ground. In

The kowtow, and other traditional forms of reverence, were much maligned after the May Fourth Movement. Today, only vestiges of the traditional usage of the kowtow remain. In many situations, the standing bow has replaced the kowtow. For example, some, but not all, people would choose to kowtow before the grave of an ancestor, or while making traditional offerings to an ancestor. Direct descendants may also kowtow at the funeral of an ancestor, while others would simply bow. During a wedding, some couples may kowtow to their respective parents, though the standing bow is today more common. In extreme cases, the kowtow can be used to express profound gratitude, apology, or to beg for forgiveness.

The kowtow remains alive as part of a formal induction ceremony in certain traditional trades that involve apprenticeship or discipleship. For example, Chinese martial arts schools often require a student to kowtow to a master. Likewise, traditional performing arts often also require the kowtow.

The kowtow, and other traditional forms of reverence, were much maligned after the May Fourth Movement. Today, only vestiges of the traditional usage of the kowtow remain. In many situations, the standing bow has replaced the kowtow. For example, some, but not all, people would choose to kowtow before the grave of an ancestor, or while making traditional offerings to an ancestor. Direct descendants may also kowtow at the funeral of an ancestor, while others would simply bow. During a wedding, some couples may kowtow to their respective parents, though the standing bow is today more common. In extreme cases, the kowtow can be used to express profound gratitude, apology, or to beg for forgiveness.

The kowtow remains alive as part of a formal induction ceremony in certain traditional trades that involve apprenticeship or discipleship. For example, Chinese martial arts schools often require a student to kowtow to a master. Likewise, traditional performing arts often also require the kowtow.

online

* Frevert, Ute. "Kneeling and the Protocol of Humiliation." in by Benno Gammerl, Philipp Nielsen, and Margrit, eds. ''Encounters with Emotions: Negotiating Cultural Differences since Early Modernity'' (2019): pp. 133–159 excerpt. * Gao, Hao. "The "Inner Kowtow Controversy" During the Amherst Embassy to China, 1816–1817." ''Diplomacy & Statecraft'' 27.4 (2016): 595–614. * Hevia, James L. "‘The ultimate gesture of deference and debasement’: kowtowing in China." ''Past and Present'' 203.suppl_4 (2009): 212–234. * Pritchard, Earl H. "The kotow in the Macartney embassy to China in 1793." ''Journal of Asian Studies'' 2.2 (1943): 163–203

online

* * Rockhill, William Woodville. "Diplomatic Missions to the Court of China: The Kotow Question I," ''The American Historical Review,'' Vol. 2, No. 3 (Apr. 1897), pp. 427–442

online

* Rockhill, William Woodville. "Diplomatic Missions to the Court of China: The Kotow Question II," ''The American Historical Review,'' Vol. 2, No. 4 (Jul. 1897), pp. 627–643.

online

Sinospheric

The East Asian cultural sphere, also known as the Sinosphere, the Sinic world, the Sinitic world, the Chinese cultural sphere, the Chinese character sphere encompasses multiple countries in East Asia and Southeast Asia that were historically ...

culture, the kowtow is the highest sign of reverence. It was widely used to show reverence for one's elders, superiors, and especially the Emperor of China, as well as for religious and cultural objects of worship. In modern times, usage of the kowtow has been reduced.

Terminology

An alternative Chinese term is ''ketou''; however, the meaning is somewhat altered: ''kou'' () has the general meaning of ''knock'', whereas ''ke'' () has the general meaning of "touch upon (a surface)", ''tou'' () meaning head. The date of this custom's origin is probably sometime during theSpring and Autumn period

The Spring and Autumn period was a period in Chinese history from approximately 770 to 476 BC (or according to some authorities until 403 BC) which corresponds roughly to the first half of the Eastern Zhou period. The period's name derives fr ...

or the Warring States period of China's history (771–221 BC), because it was a custom by the time of the Qin dynasty (221 BC – 206 BC).

Traditional usage

In Imperial Chinese protocol, the kowtow was performed before the Emperor of China. Depending on the solemnity of the situation different grades of kowtow would be used. In the most solemn of ceremonies, for example at the coronation of a new Emperor, the Emperor's subjects would undertake the ceremony of the "three kneelings and nine kowtows", the so-called grand kowtow, which involves kneeling from a standing position three times, and each time, performing the kowtow three times while kneeling.Immanuel Hsu

Immanuel Chung-Yueh Hsü (, 1923 – October 24, 2005) was a sinologist, a scholar of modern Chinese intellectual and diplomatic history, and a professor of history at the University of California at Santa Barbara.

Biography

Born in Shanghai i ...

describes the "full kowtow" as "three kneelings and nine knockings of the head on the ground".

As government officials represented the majesty of the Emperor while carrying out their duties, commoners were also required to kowtow to them in formal situations. For example, a commoner brought before a local magistrate would be required to kneel and kowtow. A commoner is then required to remain kneeling, whereas a person who has earned a degree in the Imperial examinations is permitted a seat.

Since one is required by Confucian philosophy to show great reverence to one's parents and grandparents, children may also be required to kowtow to their elderly ancestors, particularly on special occasions. For example, at a wedding, the marrying couple was traditionally required to kowtow to both sets of parents, as acknowledgement of the debt owed for their nurturing.

Confucius believed there was a natural harmony between the body and mind and therefore, whatever actions were expressed through the body would be transferred over to the mind. Because the body is placed in a low position in the kowtow, the idea is that one will naturally convert to his or her mind a feeling of respect. What one does to oneself influences the mind. Confucian philosophy held that respect was important for a society, making bowing an important ritual.

Modern Chinese usage

The kowtow, and other traditional forms of reverence, were much maligned after the May Fourth Movement. Today, only vestiges of the traditional usage of the kowtow remain. In many situations, the standing bow has replaced the kowtow. For example, some, but not all, people would choose to kowtow before the grave of an ancestor, or while making traditional offerings to an ancestor. Direct descendants may also kowtow at the funeral of an ancestor, while others would simply bow. During a wedding, some couples may kowtow to their respective parents, though the standing bow is today more common. In extreme cases, the kowtow can be used to express profound gratitude, apology, or to beg for forgiveness.

The kowtow remains alive as part of a formal induction ceremony in certain traditional trades that involve apprenticeship or discipleship. For example, Chinese martial arts schools often require a student to kowtow to a master. Likewise, traditional performing arts often also require the kowtow.

The kowtow, and other traditional forms of reverence, were much maligned after the May Fourth Movement. Today, only vestiges of the traditional usage of the kowtow remain. In many situations, the standing bow has replaced the kowtow. For example, some, but not all, people would choose to kowtow before the grave of an ancestor, or while making traditional offerings to an ancestor. Direct descendants may also kowtow at the funeral of an ancestor, while others would simply bow. During a wedding, some couples may kowtow to their respective parents, though the standing bow is today more common. In extreme cases, the kowtow can be used to express profound gratitude, apology, or to beg for forgiveness.

The kowtow remains alive as part of a formal induction ceremony in certain traditional trades that involve apprenticeship or discipleship. For example, Chinese martial arts schools often require a student to kowtow to a master. Likewise, traditional performing arts often also require the kowtow.

Religion

Prostration is a general practice in Buddhism, and not restricted to China. The kowtow is often performed in groups of three before Buddhist statues and images or tombs of the dead. In Buddhism it is more commonly termed either "worship with the crown (of the head)" (頂禮 ding li) or "casting the five limbs to the earth" (五體投地 wuti tou di)—referring to the two arms, two legs and forehead. For example, in certain ceremonies, a person would perform a sequence of three sets of three kowtows—stand up and kneel down again between each set—as an extreme gesture of respect; hence the term ''three kneelings and nine head knockings'' (). Also, some Buddhist pilgrims would kowtow once for every three steps made during their long journeys, the number three referring to the Triple Gem of Buddhism, the Buddha, theDharma

Dharma (; sa, धर्म, dharma, ; pi, dhamma, italic=yes) is a key concept with multiple meanings in Indian religions, such as Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism, Sikhism and others. Although there is no direct single-word translation for '' ...

, and the Sangha. Prostration is widely practiced in India by Hindus to give utmost respect to their deities in temples and to parents and elders. Nowadays in modern times people show the regards to elders by bowing down and touching their feet.

Diplomacy

The word "kowtow" came into English in the early 19th century to describe the bow itself, but its meaning soon shifted to describe any abject submission or groveling. The term is still commonly used in English with this meaning, disconnected from the physical act and the East Asian context. Dutch ambassador Isaac Titsingh did not refuse to kowtow during the course of his 1794–1795 mission to the imperial court of theQianlong Emperor

The Qianlong Emperor (25 September 17117 February 1799), also known by his temple name Emperor Gaozong of Qing, born Hongli, was the fifth Emperor of the Qing dynasty and the fourth Qing emperor to rule over China proper, reigning from 1735 t ...

. The members of the Titsingh mission, including Andreas Everardus van Braam Houckgeest and Chrétien-Louis-Joseph de Guignes, made every effort to conform with the demands of the complex Imperial court etiquette.

The Qing courts gave bitter feedback to the Afghan

Afghan may refer to:

*Something of or related to Afghanistan, a country in Southern-Central Asia

*Afghans, people or citizens of Afghanistan, typically of any ethnicity

** Afghan (ethnonym), the historic term applied strictly to people of the Pas ...

emir Ahmad Shah when its Afghan envoy, presenting four splendid horses to Qianlong in 1763, refused to perform the kowtow. Coming amid tense relations between the Qing and Durrani empires, Chinese officials forbade the Afghans from sending envoys to Beijing in the future..

On two occasions, the kowtow was performed by Chinese envoys to a foreign ruler – specifically the Russian Tsar. T'o-Shih, Qing emissary to Russia whose mission to Moscow took place in 1731, kowtowed before Tsarina Anna

Anna may refer to:

People Surname and given name

* Anna (name)

Mononym

* Anna the Prophetess, in the Gospel of Luke

* Anna (wife of Artabasdos) (fl. 715–773)

* Anna (daughter of Boris I) (9th–10th century)

* Anna (Anisia) (fl. 1218 to 1221)

...

, as per instructions by the Yongzheng Emperor, as did Desin, who led another mission the next year to the new Russian capital at St. Petersburg. Hsu notes that the Kangxi Emperor, Yongzheng's predecessor, explicitly ordered that Russia be given a special status in Qing foreign relations by not being included among tributary states

A tributary state is a term for a pre-modern state in a particular type of subordinate relationship to a more powerful state which involved the sending of a regular token of submission, or tribute, to the superior power (the suzerain). This to ...

, i.e. recognition as an implicit equal of China.

The kowtow was often performed in intra-Asian diplomatic relations as well. In 1636, after being defeated by the invading Manchus, King Injo of Joseon (Korea) was forced to surrender by kowtowing three times to pledge tributary status to the Qing Emperor, Hong Taiji. As was customary of all Asian envoys to Qing China, Joseon envoys kowtowed three times to the Qing emperor during their visits to China, continuing until 1896, when the Korean Empire

The Korean Empire () was a Korean monarchical state proclaimed in October 1897 by Emperor Gojong of the Joseon dynasty. The empire stood until Japan's annexation of Korea in August 1910.

During the Korean Empire, Emperor Gojong oversaw the Gwa ...

withdrew its tributary status from Qing as a result of the First Sino-Japanese War.

The King of the Ryukyu Kingdom also had to kneel three times on the ground and touch his head nine times to the ground (), to show his allegiance to the Chinese emperors.

See also

* Chinese social relations * Culture of China * Dogeza * Emoticons for posture *Finger kowtow: ** Finger tapping in Chinese tea culture ** Finger tapping in Yum Cha *Gadaw

Gadaw ( my, ကန်တော့, ; also spelt kadaw) is a Burmese verb referring to a Burmese tradition in which a person, always of lower social standing, pays respect or homage to a person of higher standing (including Buddhist monks, elders, ...

, a Burmese form of obeisance akin to kowtow

* Hand-kissing

*John Moyse

Private John Moyse was a British soldier of the 3rd (East Kent) Regiment who according to popular legend was captured by Chinese soldiers during the Second Opium War and later was executed for refusing to prostrate himself before the Chinese ge ...

* Maundy (foot washing), another act of extreme humility

* Orz

* Proskynesis

* Prostration

* Salute

*''Sankin-kōtai

''Sankin-kōtai'' ( ja, 参覲交代/参覲交替, now commonly written as ja, 参勤交代/参勤交替, lit=alternate attendance, label=none) was a policy of the Tokugawa shogunate during most of the Edo period of Japanese history.Jansen, M ...

''

* Shuysky Tribute, a similar Eastern European practice

* Sifu

*Sujud

Sujūd ( ar, سُجود, ), or sajdah (, ), is the act of low bowing or prostration to God facing the ''qiblah'' (direction of the Kaaba at Mecca). It is usually done in standardized prayers (salah). The position involves kneeling and bowing t ...

, prostration to Allah

* Yeongeunmun

Notes

References

Citations

Sources

* Fairbank, John K., and Ssu-yu Teng. "On the Ch'ing tributary system." ''Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies'' 6.2 (1941): 135–246online

* Frevert, Ute. "Kneeling and the Protocol of Humiliation." in by Benno Gammerl, Philipp Nielsen, and Margrit, eds. ''Encounters with Emotions: Negotiating Cultural Differences since Early Modernity'' (2019): pp. 133–159 excerpt. * Gao, Hao. "The "Inner Kowtow Controversy" During the Amherst Embassy to China, 1816–1817." ''Diplomacy & Statecraft'' 27.4 (2016): 595–614. * Hevia, James L. "‘The ultimate gesture of deference and debasement’: kowtowing in China." ''Past and Present'' 203.suppl_4 (2009): 212–234. * Pritchard, Earl H. "The kotow in the Macartney embassy to China in 1793." ''Journal of Asian Studies'' 2.2 (1943): 163–203

online

* * Rockhill, William Woodville. "Diplomatic Missions to the Court of China: The Kotow Question I," ''The American Historical Review,'' Vol. 2, No. 3 (Apr. 1897), pp. 427–442

online

* Rockhill, William Woodville. "Diplomatic Missions to the Court of China: The Kotow Question II," ''The American Historical Review,'' Vol. 2, No. 4 (Jul. 1897), pp. 627–643.

online

External links

* {{Gestures Chinese culture Etiquette Bowing Chinese words and phrases Gestures of respect Kneeling