Klaus Kinski (band) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Klaus Kinski (, born Klaus Günter Karl Nakszynski 18 October 1926 – 23 November 1991) was a German actor. Equally renowned for his intense performance style and notorious for his volatile personality, he appeared in over 130 film roles in a career that spanned 40 years, from 1948 to 1988. He is best known for starring in five films directed by

Klaus Günter Karl Nakszynski was born on 18 October 1926 in

Klaus Günter Karl Nakszynski was born on 18 October 1926 in

Kinski's first film role was a small part in the 1948 film '' Morituri''. He appeared in several German

Kinski's first film role was a small part in the 1948 film '' Morituri''. He appeared in several German  Kinski's work with Werner Herzog brought him international recognition. They made five films together: '' Aguirre: The Wrath of God'' (1972), ''

Kinski's work with Werner Herzog brought him international recognition. They made five films together: '' Aguirre: The Wrath of God'' (1972), ''

In ''

In ''

Werner Herzog

Werner Herzog (; born 5 September 1942) is a German film director, screenwriter, author, actor, and opera director, regarded as a pioneer of New German Cinema. His films often feature ambitious protagonists with impossible dreams, people with un ...

from 1972 to 1987 (''Aguirre, the Wrath of God

''Aguirre, the Wrath of God'' (; german: Aguirre, der Zorn Gottes; ) is a 1972 West German epic historical drama film produced, written and directed by Werner Herzog. Klaus Kinski stars in the title role of Spanish soldier Lope de Aguirre, wh ...

'', ''Nosferatu the Vampyre

''Nosferatu the Vampyre'' (german: Nosferatu: Phantom der Nacht, lit=Nosferatu: Phantom of the Night) is a 1979 horror film written and directed by Werner Herzog. It is set primarily in 19th-century Wismar, Germany and Transylvania, and was conce ...

'', ''Woyzeck

''Woyzeck'' () is a stage play written by Georg Büchner. Büchner wrote the play between July and October 1836, yet left it incomplete at his death in February 1837. The play first appeared in 1877 in a heavily edited version by Karl Emil Fr ...

'', ''Fitzcarraldo

''Fitzcarraldo'' () is a 1982 West German epic adventure-drama film written, produced and directed by Werner Herzog, and starring Klaus Kinski as would-be rubber baron, Brian Sweeney Fitzgerald, an Irishman known in Peru as Fitzcarraldo, who i ...

'', and ''Cobra Verde

''Cobra Verde'' (also known as ''Slave Coast'') is a 1987 German drama film directed by Werner Herzog and starring Klaus Kinski, in their fifth and final collaboration. Based upon Bruce Chatwin's 1980 novel ''The Viceroy of Ouidah'', the film de ...

''), who would later chronicle their tumultuous relationship in the documentary ''My Best Fiend

''My Best Fiend'' (german: Mein liebster Feind - Klaus Kinski, literally ''My Dearest Foe - Klaus Kinski'') is a 1999 German documentary film written and directed by Werner Herzog, about his tumultuous yet productive relationship with German actor ...

''.

Kinski's roles spanned multiple genres, languages, and nationalities, including Spaghetti Western

The Spaghetti Western is a broad subgenre of Western films produced in Europe. It emerged in the mid-1960s in the wake of Sergio Leone's film-making style and international box-office success. The term was used by foreign critics because most o ...

s, horror films

Horror is a film genre that seeks to elicit fear or disgust in its audience for entertainment purposes.

Horror films often explore dark subject matter and may deal with transgressive topics or themes. Broad elements include monsters, apoc ...

, war films

War film is a film genre concerned with warfare, typically about naval, air, or land battles, with combat scenes central to the drama. It has been strongly associated with the 20th century. The fateful nature of battle scenes means that war f ...

, dramas

Drama is the specific mode of fiction represented in performance: a play, opera, mime, ballet, etc., performed in a theatre, or on radio or television.Elam (1980, 98). Considered as a genre of poetry in general, the dramatic mode has been c ...

, and Edgar Wallace

Richard Horatio Edgar Wallace (1 April 1875 – 10 February 1932) was a British writer.

Born into poverty as an illegitimate London child, Wallace left school at the age of 12. He joined the army at age 21 and was a war correspondent during th ...

''krimi

Edgar Wallace (1875–1932) was a British novelist and playwright and screenwriter whose works have been adapted for the screen on many occasions.

British adaptations

His works were adapted for the silent screen as early as 1916, and continued ...

'' films. His infamy was elevated by a number of eccentric creative endeavors, including a one-man show based on the life of Jesus Christ

Jesus, likely from he, יֵשׁוּעַ, translit=Yēšūaʿ, label=Hebrew/Aramaic ( AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ or Jesus of Nazareth (among other names and titles), was a first-century Jewish preacher and religious ...

, a biopic

A biographical film or biopic () is a film that dramatizes the life of a non-fictional or historically-based person or people. Such films show the life of a historical person and the central character's real name is used. They differ from docudra ...

of violinist Niccolò Paganini

Niccolò (or Nicolò) Paganini (; 27 October 178227 May 1840) was an Italian violinist and composer. He was the most celebrated violin virtuoso of his time, and left his mark as one of the pillars of modern violin technique. His 24 Caprices f ...

directed by and starring himself, and over twenty spoken word

Spoken word refers to an oral poetic performance art that is based mainly on the poem as well as the performer's aesthetic qualities. It is a late 20th century continuation of an ancient oral artistic tradition that focuses on the aesthetics of ...

albums.

Kinski was prone to emotional and often violent outbursts aimed at his directors and fellow cast members, issues complicated by a history of mental illness

A mental disorder, also referred to as a mental illness or psychiatric disorder, is a behavioral or mental pattern that causes significant distress or impairment of personal functioning. Such features may be persistent, relapsing and remitti ...

. Herzog described him as "one of the greatest actors of the century, but also a monster and a great pestilence."

Posthumously, he was accused of physically and sexually abusing his daughters Pola Pola or POLA may refer to:

People

*House of Pola, an Italian noble family

*Pola Alonso (1923–2004), Argentine actress

*Pola Brändle (born 1980), German artist and photographer

*Pola Gauguin (1883–1961), Danish painter

*Pola Gojawiczyńska (18 ...

and Nastassja, themselves actresses. His notoriety and prolific output has developed into a widespread cult following

A cult following refers to a group of fans who are highly dedicated to some person, idea, object, movement, or work, often an artist, in particular a performing artist, or an artwork in some medium. The lattermost is often called a cult classic. ...

and a reputation as a popular icon

A pop icon is a celebrity, character, or object whose exposure in popular culture is regarded as constituting a defining characteristic of a given society or era. The usage of the term is largely subjective since there are no definitively object ...

.

Early life

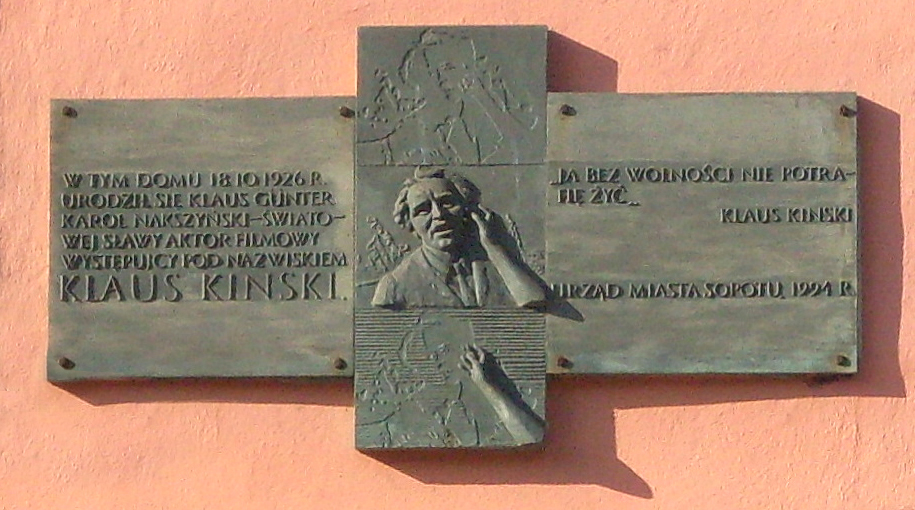

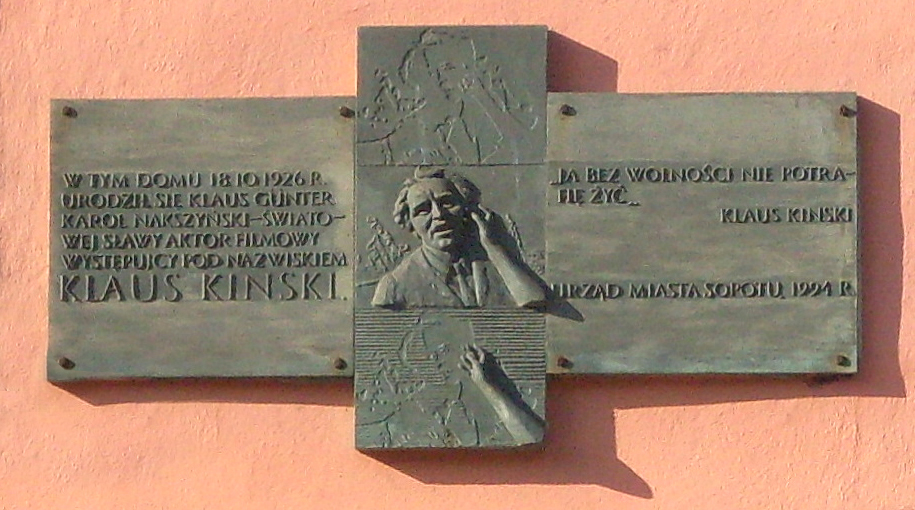

Klaus Günter Karl Nakszynski was born on 18 October 1926 in

Klaus Günter Karl Nakszynski was born on 18 October 1926 in Zoppot

Sopot is a seaside resort city in Pomerelia on the southern coast of the Baltic Sea in northern Poland, with a population of approximately 40,000. It is located in Pomeranian Voivodeship, and has the status of the county, being the smallest city ...

, Free City of Danzig

The Free City of Danzig (german: Freie Stadt Danzig; pl, Wolne Miasto Gdańsk; csb, Wòlny Gard Gduńsk) was a city-state under the protection of the League of Nations between 1920 and 1939, consisting of the Baltic Sea port of Danzig (now Gda ...

(now Sopot, Poland), to Polish-German parents. His father, Bruno Nakszynski, worked as an opera

Opera is a form of theatre in which music is a fundamental component and dramatic roles are taken by singers. Such a "work" (the literal translation of the Italian word "opera") is typically a collaboration between a composer and a librett ...

singer before becoming a pharmacist, while his mother, Susanne Lutze, was a nurse and the daughter of a local pastor. He had three older siblings; Inge, Arne and Hans-Joachim. Due to the Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

, his family was unable to make a living in Danzig and moved to Berlin

Berlin ( , ) is the capital and largest city of Germany by both area and population. Its 3.7 million inhabitants make it the European Union's most populous city, according to population within city limits. One of Germany's sixteen constitue ...

in 1931, where they also experienced financial difficulties. The family settled in an apartment in the Schöneberg

Schöneberg () is a locality of Berlin, Germany. Until Berlin's 2001 administrative reform it was a separate borough including the locality of Friedenau. Together with the former borough of Tempelhof it is now part of the new borough of Tempelh ...

district of the city and acquired German citizenship

German nationality law details the conditions by which an individual holds German nationality. The primary law governing these requirements is the Nationality Act, which came into force on 1 January 1914.

Germany is a member state of the Europ ...

. In 1936, he began attending the in Schöneberg.

Kinski was conscripted into the ''Wehrmacht

The ''Wehrmacht'' (, ) were the unified armed forces of Nazi Germany from 1935 to 1945. It consisted of the ''Heer'' (army), the ''Kriegsmarine'' (navy) and the ''Luftwaffe'' (air force). The designation "''Wehrmacht''" replaced the previous ...

'' in 1943 at the age of 17, serving in a unit. He saw no action until the winter of 1944, when his unit was transferred to the German-occupied Netherlands

Despite Dutch neutrality, Nazi Germany invaded the Netherlands on 10 May 1940 as part of Fall Gelb (Case Yellow). On 15 May 1940, one day after the bombing of Rotterdam, the Dutch forces surrendered. The Dutch government and the royal family re ...

and he was captured by the British Army

The British Army is the principal land warfare force of the United Kingdom, a part of the British Armed Forces along with the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. , the British Army comprises 79,380 regular full-time personnel, 4,090 Gurk ...

on his second day of combat. In his 1988 autobiography, he claimed that he had decided to desert from the ''Wehrmacht'' and had been recaptured by German forces and sentenced to death in a court-martial

A court-martial or court martial (plural ''courts-martial'' or ''courts martial'', as "martial" is a postpositive adjective) is a military court or a trial conducted in such a court. A court-martial is empowered to determine the guilt of memb ...

before escaping and hiding in the woods, subsequently encountering a British patrol which shot him in the arm and captured him. After being treated for his wounds and interrogated, he was transferred to a prisoner-of-war camp

A prisoner-of-war camp (often abbreviated as POW camp) is a site for the containment of enemy fighters captured by a belligerent power in time of war.

There are significant differences among POW camps, internment camps, and military prisons. P ...

in Colchester

Colchester ( ) is a city in Essex, in the East of England. It had a population of 122,000 in 2011. The demonym is Colcestrian.

Colchester occupies the site of Camulodunum, the first major city in Roman Britain and its first capital. Colches ...

, Essex

Essex () is a county in the East of England. One of the home counties, it borders Suffolk and Cambridgeshire to the north, the North Sea to the east, Hertfordshire to the west, Kent across the estuary of the River Thames to the south, and G ...

; the ship transporting him to Britain was torpedoed by a German U-boat

U-boats were naval submarines operated by Germany, particularly in the First and Second World Wars. Although at times they were efficient fleet weapons against enemy naval warships, they were most effectively used in an economic warfare role ...

but arrived safely.

In his documentary ''My Best Fiend

''My Best Fiend'' (german: Mein liebster Feind - Klaus Kinski, literally ''My Dearest Foe - Klaus Kinski'') is a 1999 German documentary film written and directed by Werner Herzog, about his tumultuous yet productive relationship with German actor ...

'', Werner Herzog

Werner Herzog (; born 5 September 1942) is a German film director, screenwriter, author, actor, and opera director, regarded as a pioneer of New German Cinema. His films often feature ambitious protagonists with impossible dreams, people with un ...

claimed that Kinski had fabricated much of his 1988 autobiography, including claims of maternal sexual abuse

Sexual abuse or sex abuse, also referred to as molestation, is abusive sexual behavior by one person upon another. It is often perpetrated using force or by taking advantage of another. Molestation often refers to an instance of sexual assa ...

, incest

Incest ( ) is human sexual activity between family members or close relatives. This typically includes sexual activity between people in consanguinity (blood relations), and sometimes those related by affinity (marriage or stepfamily), adoption ...

, and childhood poverty; according to Herzog, Kinski was actually raised in a financially stable upper middle class

In sociology, the upper middle class is the social group constituted by higher status members of the middle class. This is in contrast to the term ''lower middle class'', which is used for the group at the opposite end of the middle-class strat ...

family.

Career

While interned at Berechurch Hall in Colchester, Kinski played his first roles on stage, taking part in variety shows intended to maintain morale among the prisoners. By May 1945, at the end of the war in Europe, the German POWs were anxious to return home. Kinski had heard that sick prisoners were to be returned first, and tried to qualify by standing outside naked at night,drinking urine

Urophagia is the consumption of urine. Urine was used in several ancient cultures for various health, healing, and cosmetic purposes; urine drinking is still practiced today. In extreme cases, people may drink urine if no other fluids are availabl ...

and eating cigarettes. He remained healthy, however, and was returned to Germany in 1946.

Arriving in Berlin, he learned his father had died during the war, and his mother had been killed in an Allied air attack on the city.

Theatrical career

After his return to Germany, Kinski started out as an actor, first at a small touring company inOffenburg

Offenburg ("open borough" - coat of arms showing open gates; Low Alemannic German, Low Alemmanic: ''Offäburg'') is a city located in the state of Baden-Württemberg, Germany. With nearly 60,000 inhabitants (2019), it is the largest city and the ad ...

, where he first used the name "Klaus Kinski". In 1946, he was hired by the renowned Schlosspark-Theater in Berlin, but he was fired the following year due to his unpredictable behavior. He found work at other theater companies thereafter, but his emotional volatility regularly got him into trouble.

For three months in 1955, Kinski lived in the same boarding house as a 13-year-old Werner Herzog, who would later direct him in a number of films. In ''My Best Fiend'', Herzog described how Kinski once locked himself in the communal bathroom for 48 hours and broke everything in the room.

In March 1956, he made a guest appearance at Vienna

en, Viennese

, iso_code = AT-9

, registration_plate = W

, postal_code_type = Postal code

, postal_code =

, timezone = CET

, utc_offset = +1

, timezone_DST ...

's Burgtheater

The Burgtheater (literally:"Castle Theater" but alternatively translated as "(Imperial) Court Theater"), originally known as '' K.K. Theater an der Burg'', then until 1918 as the ''K.K. Hofburgtheater'', is the national theater of Austria in Vi ...

in Goethe

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (28 August 1749 – 22 March 1832) was a German poet, playwright, novelist, scientist, statesman, theatre director, and critic. His works include plays, poetry, literature, and aesthetic criticism, as well as treat ...

's ''Torquato Tasso

Torquato Tasso ( , also , ; 11 March 154425 April 1595) was an Italian poet of the 16th century, known for his 1591 poem ''Gerusalemme liberata'' (Jerusalem Delivered), in which he depicts a highly imaginative version of the combats between ...

''. Although respected by his colleagues, among them Judith Holzmeister

Judith Maria Holzmeister (14 February 1920 – 23 June 2008) was an Austrian actress. Her performances included ''Kunigunde'' opposite Ewald Balser in Franz Grillparzer's ''König Ottokars Glück und Ende'' at the reopening of the famed Vienna ...

, and cheered by the audience, Kinski did not gain a permanent contract after the Burgtheater's management became aware of his earlier difficulties in Germany. Kinski then unsuccessfully tried to sue the company.

Living jobless in Vienna, Kinski reinvented himself as a monologist

A monologist (), or interchangeably monologuist (), is a solo artist who recites or gives dramatic readings from a monologue, soliloquy, poetry, or work of literature, for the entertainment of an audience. The term can also refer to a person wh ...

and spoken word

Spoken word refers to an oral poetic performance art that is based mainly on the poem as well as the performer's aesthetic qualities. It is a late 20th century continuation of an ancient oral artistic tradition that focuses on the aesthetics of ...

artist. He presented the prose and verse of François Villon

François Villon (Modern French: , ; – after 1463) is the best known French poet of the Late Middle Ages. He was involved in criminal behavior and had multiple encounters with law enforcement authorities. Villon wrote about some of these ex ...

, William Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 26 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's nation ...

and Oscar Wilde

Oscar Fingal O'Flahertie Wills Wilde (16 October 185430 November 1900) was an Irish poet and playwright. After writing in different forms throughout the 1880s, he became one of the most popular playwrights in London in the early 1890s. He is ...

, amongst others, and toured Austria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populous ...

, Germany, and Switzerland

). Swiss law does not designate a ''capital'' as such, but the federal parliament and government are installed in Bern, while other federal institutions, such as the federal courts, are in other cities (Bellinzona, Lausanne, Luzern, Neuchâtel ...

with his shows.

Film work

Edgar Wallace

Richard Horatio Edgar Wallace (1 April 1875 – 10 February 1932) was a British writer.

Born into poverty as an illegitimate London child, Wallace left school at the age of 12. He joined the army at age 21 and was a war correspondent during th ...

movies, and had bit parts in the American war films ''Decision Before Dawn

''Decision Before Dawn'' is a 1951 American war film directed by Anatole Litvak, starring Richard Basehart, Oskar Werner, and Hans Christian Blech. It tells the story of the American Army using potentially unreliable German prisoners of war to ga ...

'' (1951), ''A Time to Love and a Time to Die

''A Time to Love and a Time to Die'' is a 1958 Eastmancolor CinemaScope drama war film directed by Douglas Sirk and starring John Gavin and Liselotte Pulver. Based on the book by German author Erich Maria Remarque and set on the Eastern Front ...

'' (1958), and ''The Counterfeit Traitor

''The Counterfeit Traitor'' is a 1962 espionage thriller film starring William Holden, Hugh Griffith, and Lilli Palmer. Holden plays an American-born Swedish citizen who agrees to spy on the Nazis in World War II. It was based on a nonfiction boo ...

'' (1962). In Alfred Vohrer

Alfred Vohrer (29 December 1914 – 3 February 1986) was a German film director and actor. He directed 48 films between 1958 and 1984. His 1969 film ''Seven Days Grace'' was entered into the 6th Moscow International Film Festival. His 1972 ...

's '' Die toten Augen von London'' (1961), his character refused any personal guilt for his evil deeds and claimed to have only followed the orders given to him. Kinski's performance reflected post-war Germany's reluctance to take responsibility for what had happened during World War II.

During the 1960s and 1970s, he appeared in various European exploitation films

An exploitation film is a film that tries to succeed financially by exploiting current trends, niche genres, or lurid content. Exploitation films are generally low-quality "B movies", though some set trends, attract critical attention, become hi ...

, as well as more acclaimed works such as ''Doctor Zhivago

''Doctor Zhivago'' is the title of a novel by Boris Pasternak and its various adaptations.

Description

The story, in all of its forms, describes the life of the fictional Russian physician and poet Yuri Zhivago and deals with love and loss during ...

'' (1965), in which he appeared as an anarchist prisoner on his way to the Gulag

The Gulag, an acronym for , , "chief administration of the camps". The original name given to the system of camps controlled by the GPU was the Main Administration of Corrective Labor Camps (, )., name=, group= was the government agency in ...

.

He relocated to Italy during the late 1960s, and found roles in numerous Spaghetti Western

The Spaghetti Western is a broad subgenre of Western films produced in Europe. It emerged in the mid-1960s in the wake of Sergio Leone's film-making style and international box-office success. The term was used by foreign critics because most o ...

s, including ''For a Few Dollars More

''For a Few Dollars More'' ( it, Per qualche dollaro in più) is a 1965 Spaghetti Western film directed by Sergio Leone. It stars Clint Eastwood and Lee Van Cleef as bounty hunters and Gian Maria Volonté as the primary villain. German actor K ...

'' (1965), ''A Bullet for the General

''A Bullet for the General'' ( es, Quién sabe?; original title means "Who knows?", in the Spanish language), also known as ''El Chucho Quién Sabe?'', is a 1966 Cinema of Italy, Italian Zapata Western film directed by Damiano Damiani and starrin ...

'' (1966), ''The Great Silence

''The Great Silence'' ( it, Il grande silenzio) is a 1968 revisionist Spaghetti Western film directed and co-written by Sergio Corbucci. An Italian-French co-production, the film stars Jean-Louis Trintignant, Klaus Kinski, Vonetta McGee (in ...

'' (1968), ''Twice A Judas

Twice (; Japanese: トゥワイス, Hepburn: ''To~uwaisu''; commonly stylized as TWICE) is a South Korean girl group formed by JYP Entertainment. The group is composed of nine members: Nayeon, Jeongyeon, Momo, Sana, Jihyo, Mina, Dahyun, Chaey ...

'' (1969), and ''A Genius, Two Partners and a Dupe

''A Genius, Two Partners and a Dupe'' ( it, Un genio, due compari, un pollo) is a 1975 Spaghetti Western comedy film directed by Damiano Damiani and Sergio Leone, who directed the opening scene.

Plot

Joe Thanks (Terence Hill) is a genius conman ...

'' (1975). In 1977, he starred as the RZ guerrillero Wilfried Böse

Wilfried Bonifatius "Boni" Böse (7 February 1949, – 4 July 1976) was a founding member of the German organization Revolutionary Cells that was described in the early 1980s as one of Germany's most dangerous leftist terrorist groups by the ...

in '' Operation Thunderbolt'', based on the events of the Entebbe raid

Operation Entebbe, also known as the Entebbe Raid or Operation Thunderbolt, was a counter-terrorist hostage-rescue mission carried out by commandos of the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) at Entebbe Airport in Uganda on 4 July 1976.

A week ear ...

.

Kinski's work with Werner Herzog brought him international recognition. They made five films together: '' Aguirre: The Wrath of God'' (1972), ''

Kinski's work with Werner Herzog brought him international recognition. They made five films together: '' Aguirre: The Wrath of God'' (1972), ''Woyzeck

''Woyzeck'' () is a stage play written by Georg Büchner. Büchner wrote the play between July and October 1836, yet left it incomplete at his death in February 1837. The play first appeared in 1877 in a heavily edited version by Karl Emil Fr ...

'' (1979), ''Nosferatu the Vampyre

''Nosferatu the Vampyre'' (german: Nosferatu: Phantom der Nacht, lit=Nosferatu: Phantom of the Night) is a 1979 horror film written and directed by Werner Herzog. It is set primarily in 19th-century Wismar, Germany and Transylvania, and was conce ...

'' (1979), ''Fitzcarraldo

''Fitzcarraldo'' () is a 1982 West German epic adventure-drama film written, produced and directed by Werner Herzog, and starring Klaus Kinski as would-be rubber baron, Brian Sweeney Fitzgerald, an Irishman known in Peru as Fitzcarraldo, who i ...

'' (1982) and ''Cobra Verde

''Cobra Verde'' (also known as ''Slave Coast'') is a 1987 German drama film directed by Werner Herzog and starring Klaus Kinski, in their fifth and final collaboration. Based upon Bruce Chatwin's 1980 novel ''The Viceroy of Ouidah'', the film de ...

'' (1987). The working relationship between the two was contentious; Herzog had threatened, on occasion, to murder Kinski. In one incident, Kinski was said to have been saved by his dog who attacked Herzog as he crept up to supposedly burn down the actor's house. Herzog has refused to comment on his numerous other plans to kill Kinski. However, he did pull a gun on Kinski, or at least threatened to do so, on the set of ''Aguirre, the Wrath of God,'' after the actor threatened to walk off the set. Late in the filming of ''Fitzcarraldo'' in Peru, the chief of the Machiguenga

The Machiguenga (also Matsigenka, Matsigenga) are an indigenous people who live in the high jungle, or''montaña'', area on the eastern slopes of the Andes and in the Amazon Basin jungle regions of southeastern Peru. Their population in 2020 amou ...

tribe offered to kill Kinski for Herzog, but the director declined.

In 1980, Kinski refused the lead villain role of Major Arnold Toht in ''Raiders of the Lost Ark

''Raiders of the Lost Ark'' is a 1981 American action-adventure film directed by Steven Spielberg and written by Lawrence Kasdan, based on a story by George Lucas and Philip Kaufman. It stars Harrison Ford, Karen Allen, Paul Freeman, Ronal ...

'', telling director Steven Spielberg

Steven Allan Spielberg (; born December 18, 1946) is an American director, writer, and producer. A major figure of the New Hollywood era and pioneer of the modern blockbuster, he is the most commercially successful director of all time. Spie ...

that the script was "a yawn-making, boring pile of shit" and "moronically shitty". Kinski would go on to play Kurtz, an Israeli intelligence officer, in ''The Little Drummer Girl

''The Little Drummer Girl'' is a spy novel by British writer John le Carré, published in 1983. The story follows the manipulations of Martin Kurtz, an Israeli spymaster who intends to kill Khalil – a Palestinian terrorist who is bombing Jewis ...

'', a feature film by George Roy Hill

George Roy Hill (December 20, 1921 – December 27, 2002) was an American film director. He is most noted for directing such films as ''Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid'' (1969) and ''The Sting'' (1973), both starring Paul Newman and Robert Re ...

in 1984.

Kinski co-starred in the science fiction television film

A television film, alternatively known as a television movie, made-for-TV film/movie or TV film/movie, is a feature-length film that is produced and originally distributed by or to a television network, in contrast to theatrical films made for ...

''Timestalkers

''Timestalkers'' is a 1987 American made-for-television science fiction film directed by Michael Schultz and starring William Devane.

The film is based on Ray Brown's story ''The Tintype''.

Plot

In 1986, Dr. Scott McKenzie (William Devane) is a ...

'' with William Devane

William Joseph Devane (born September 5, 1939) is an American actor. He is known for his role as Greg Sumner on the primetime soap opera '' Knots Landing'' (1983–1993) and as James Heller on the Fox serial dramas '' 24'' (2001–2010) and '' ...

and Lauren Hutton

Lauren Hutton (born Mary Laurence Hutton; November 17, 1943) is an American model and actress. Born and raised in the southern United States, Hutton relocated to New York City in her early adulthood to begin a modeling career. Though she was ini ...

. His last film was '' Paganini'' (1989), which he wrote, directed, and starred in as Niccolò Paganini

Niccolò (or Nicolò) Paganini (; 27 October 178227 May 1840) was an Italian violinist and composer. He was the most celebrated violin virtuoso of his time, and left his mark as one of the pillars of modern violin technique. His 24 Caprices f ...

.

Personal life

Kinski was married three times. He married his first wife, singer Gislinde Kühlbeck, in 1952. The couple had a daughter,Pola Kinski

Pola Kinski (born Pola Nakszynski; 23 March 1952) is a German actress. She is the firstborn daughter of the German actor Klaus Kinski.

Early life

Under the name Pola Nakszynski, Pola Kinski was born in Berlin as the only daughter of German act ...

. They divorced in 1955. Five years later he married actress Ruth Brigitte Tocki. They divorced in 1971. Their daughter Nastassja Kinski

Nastassja Aglaia Kinski (; , ; born 24 January 1961) is a German actress and former model who has appeared in more than 60 films in Europe and the United States. Her worldwide breakthrough was with ''Stay as You Are'' (1978). She then came to gl ...

was born in January 1961. He married his third and final wife, model Minhoi Geneviève Loanic, in 1971. Their son Nikolai Kinski

Nanhoï Nikolai Kinski (born July 30, 1976) is a French-American film actor, who has also done work in television and on stage. He was born in Paris, and grew up in California. Currently residing in Berlin, he has acted primarily in American and ...

was born in 1976. They divorced in 1979.

Kinski published his autobiography, ''All I Need Is Love

''All I Need Is Love: A Memoir'' is the autobiography of the German actor Klaus Kinski first published 1975 in German under the title "Ich bin so wild nach deinem Erdbeermund" (English: I am so wild about your strawberry mouth). The first translat ...

'', in 1988 (reprinted in 1996 as ''Kinski Uncut''). The book prompted his second daughter Nastassja Kinski

Nastassja Aglaia Kinski (; , ; born 24 January 1961) is a German actress and former model who has appeared in more than 60 films in Europe and the United States. Her worldwide breakthrough was with ''Stay as You Are'' (1978). She then came to gl ...

to file a libel

Defamation is the act of communicating to a third party false statements about a person, place or thing that results in damage to its reputation. It can be spoken (slander) or written (libel). It constitutes a tort or a crime. The legal defini ...

suit against him, which she afterward withdrew.

Mental illness

In 1950, Kinski stayed at the ''Karl-Bonhoeffer-Nervenklinik'' (de), apsychiatric hospital

Psychiatric hospitals, also known as mental health hospitals, behavioral health hospitals, are hospitals or wards specializing in the treatment of severe mental disorders, such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, eating disorders, dissociative ...

in West Berlin

West Berlin (german: Berlin (West) or , ) was a political enclave which comprised the western part of Berlin during the years of the Cold War. Although West Berlin was de jure not part of West Germany, lacked any sovereignty, and was under mi ...

, for three days after stalking his theatrical sponsor and attempting to strangle her. Medical records from the period listed a preliminary diagnosis of schizophrenia

Schizophrenia is a mental disorder characterized by continuous or relapsing episodes of psychosis. Major symptoms include hallucinations (typically hearing voices), delusions, and disorganized thinking. Other symptoms include social withdra ...

, but the doctors' ultimate conclusion was psychopathy

Psychopathy, sometimes considered synonymous with sociopathy, is characterized by persistent Anti-social behaviour, antisocial behavior, impaired empathy and remorse, and Boldness, bold, Disinhibition, disinhibited, and Egotism, egotistical B ...

(antisocial personality disorder

Antisocial personality disorder (ASPD or infrequently APD) is a personality disorder characterized by a long-term pattern of disregard of, or violation of, the rights of others as well as a difficulty sustaining long-term relationships. Lack ...

). Kinski soon became unable to secure film roles, and in 1955 he attempted suicide twice.

Sexual abuse allegations

In 2013, more than 20 years after her father's death,Pola Kinski

Pola Kinski (born Pola Nakszynski; 23 March 1952) is a German actress. She is the firstborn daughter of the German actor Klaus Kinski.

Early life

Under the name Pola Nakszynski, Pola Kinski was born in Berlin as the only daughter of German act ...

published an autobiography titled ''Kindermund'' (or ''From a Child's Mouth''), in which she claimed her father had sexually abused her from the age of 5 to 19.

In an interview published by the German tabloid ''Bild

''Bild'' (or ''Bild-Zeitung'', ; ) is a German tabloid newspaper published by Axel Springer SE. The paper is published from Monday to Saturday; on Sundays, its sister paper ''Bild am Sonntag'' ("''Bild on Sunday''") is published instead, which ...

'' on 14 January 2013, Kinski's younger daughter and Pola's half-sister, Nastassja, said their father would embrace her in a sexual manner when she was 4–5 years old but never had sex with her. Nastassja has expressed support for Pola and said that she was always afraid of their father, whom she described as an unpredictable tyrant.

Death

Kinski died on 23 November 1991 of a sudden heart attack at his home inLagunitas, California

Lagunitas (''Laguna'', Spanish for "Little lagoons") is an unincorporated community in Marin County, California. It is located southwest of Novato, at an elevation of 217 feet (66 m). For census purposes, Lagunitas is aggregated with Forest Kn ...

; he was 65 years old. His body was cremated, and his ashes were scattered into the Pacific Ocean. Of his three children, only his son Nikolai attended his funeral.

Legacy

In ''

In ''My Best Fiend

''My Best Fiend'' (german: Mein liebster Feind - Klaus Kinski, literally ''My Dearest Foe - Klaus Kinski'') is a 1999 German documentary film written and directed by Werner Herzog, about his tumultuous yet productive relationship with German actor ...

'', his 1999 documentary about Kinski, Werner Herzog claimed that Kinski had fabricated much of his autobiography, and told of the difficulties in their working relationship. In the same year, director David Schmoeller

David Schmoeller (born December 8, 1947) is an American film director, producer and screenwriter. He is notable for directing several full-length theatrical horror films including ''Tourist Trap'' (1979), '' The Seduction'' (1982), ''Crawlspace' ...

released a short film entitled ''Please Kill Mr. Kinski'', which examined Kinski's erratic and disruptive behavior on the set of Schmoeller's 1986 film ''Crawlspace

A crawl space is an unoccupied, unfinished, narrow space within a building, between the ground and the first (or ground) floor. The crawl space is so named because there is typically only enough room to crawl rather than stand; anything larger t ...

''. The film features behind-the-scenes footage of Kinski's various confrontations with the director and crew, along with Schmoeller's account of the events, in which he claims a producer offered to murder Kinski for his life insurance money.

In 2006, Christian David published the first comprehensive biography of Kinski, based on newly discovered archived material, personal letters and interviews with the actor's friends and colleagues. Peter Geyer published a paperback book of essays on Kinski's life and work.

Filmography and discography

Bibliography

* ''Ich bin so wild nach deinem Erdbeermund''.München

Munich ( ; german: München ; bar, Minga ) is the capital and most populous city of the German state of Bavaria. With a population of 1,558,395 inhabitants as of 31 July 2020, it is the third-largest city in Germany, after Berlin and Ha ...

: :de:Rogner & Bernhard 1975

* ''All I Need Is Love

''All I Need Is Love: A Memoir'' is the autobiography of the German actor Klaus Kinski first published 1975 in German under the title "Ich bin so wild nach deinem Erdbeermund" (English: I am so wild about your strawberry mouth). The first translat ...

''. New York : Random House, 1988.

* ''Paganini''. München

Munich ( ; german: München ; bar, Minga ) is the capital and most populous city of the German state of Bavaria. With a population of 1,558,395 inhabitants as of 31 July 2020, it is the third-largest city in Germany, after Berlin and Ha ...

: Heyne Verlag

The Heyne Verlag (formerly Wilhelm Heyne Verlag) is a German publisher based in Munich, which was founded in Dresden in 1934 and sold to Axel Springer in 2000. In 2004 it became part of Random House. Heyne was one of the largest publishing houses ...

1992

* ''Kinski Uncut: The Autobiography of Klaus Kinski''. London: Bloomsbury 1997

* (with Peter Geyer) ''Jesus Christus Erlöser und Fieber – Tagebuch eines Aussätzigen''. Frankfurt: Suhrkamp, 2006

References

External links

* * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Kinski, Klaus 1926 births 1991 deaths 20th-century German male actors Deaths from coronary thrombosis Fallschirmjäger of World War II German Film Award winners German male film actors German male stage actors German people of Polish descent German prisoners of war in World War II held by the United Kingdom German spoken word artists Male Spaghetti Western actors Naturalized citizens of Germany People from Marin County, California People from Sopot Actors from Pomeranian Voivodeship People from the Free City of Danzig People with antisocial personality disorder Kinski family