King William IV on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

William IV (William Henry; 21 August 1765 – 20 June 1837) was King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and

William was born in the early hours of the morning on 21 August 1765 at Buckingham House, the third child and son of King George III and

William was born in the early hours of the morning on 21 August 1765 at Buckingham House, the third child and son of King George III and

William ceased his active service in the Royal Navy in 1790. When Britain declared war on France in 1793, he was eager to serve his country and expected to be given a command but was not, perhaps at first because he had broken his arm by falling down some stairs drunk, but later perhaps because he gave a speech in the

William ceased his active service in the Royal Navy in 1790. When Britain declared war on France in 1793, he was eager to serve his country and expected to be given a command but was not, perhaps at first because he had broken his arm by falling down some stairs drunk, but later perhaps because he gave a speech in the

Deeply in debt, William made multiple attempts at marrying a wealthy heiress such as

Deeply in debt, William made multiple attempts at marrying a wealthy heiress such as

William's elder brother, the Prince of Wales, had been

William's elder brother, the Prince of Wales, had been

When King George IV died on 26 June 1830 without surviving legitimate issue, William succeeded him as King William IV. Aged 64, he was the oldest person to that point to assume the British throne, a distinction he would hold until surpassed by

When King George IV died on 26 June 1830 without surviving legitimate issue, William succeeded him as King William IV. Aged 64, he was the oldest person to that point to assume the British throne, a distinction he would hold until surpassed by

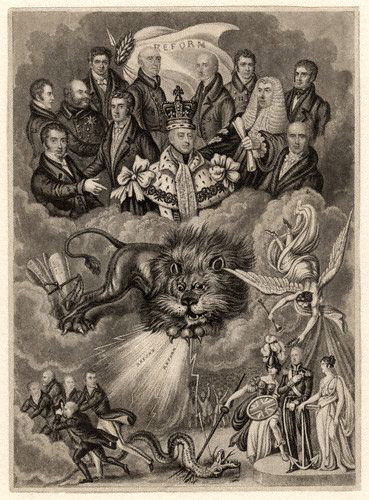

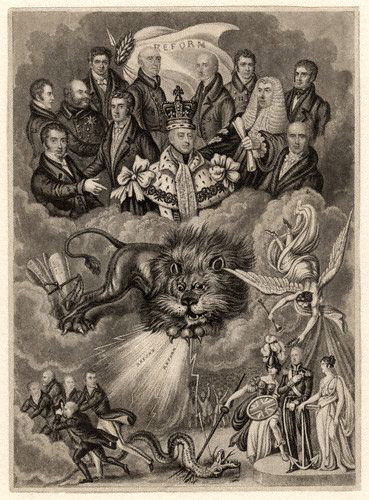

When the First Reform Bill was defeated in the House of Commons in 1831, Grey's ministry urged William to dissolve Parliament, which would lead to a new general election. At first, William hesitated to exercise his prerogative to dissolve Parliament because elections had just been held the year before and the country was in a state of high excitement which might boil over into violence. He was, however, irritated by the conduct of the Opposition, which announced its intention to move the passage of an Address, or resolution, in the House of Lords, against dissolution. Regarding the Opposition's motion as an attack on his prerogative, and at the urgent request of Lord Grey and his ministers, the King prepared to go in person to the House of Lords and

When the First Reform Bill was defeated in the House of Commons in 1831, Grey's ministry urged William to dissolve Parliament, which would lead to a new general election. At first, William hesitated to exercise his prerogative to dissolve Parliament because elections had just been held the year before and the country was in a state of high excitement which might boil over into violence. He was, however, irritated by the conduct of the Opposition, which announced its intention to move the passage of an Address, or resolution, in the House of Lords, against dissolution. Regarding the Opposition's motion as an attack on his prerogative, and at the urgent request of Lord Grey and his ministers, the King prepared to go in person to the House of Lords and

For the remainder of his reign, William interfered actively in politics only once, in 1834, when he became the last British sovereign to choose a prime minister contrary to the will of Parliament. In 1834, the ministry was facing increasing unpopularity and Lord Grey retired; the

For the remainder of his reign, William interfered actively in politics only once, in 1834, when he became the last British sovereign to choose a prime minister contrary to the will of Parliament. In 1834, the ministry was facing increasing unpopularity and Lord Grey retired; the  In November 1834, the

In November 1834, the  William was "very much shaken and affected" by the death of his eldest daughter, Sophia, Lady de L'Isle and Dudley, in childbirth in April 1837. William and his eldest son, George, Earl of Munster, were estranged at the time, but William hoped that a letter of condolence from Munster signalled a reconciliation. His hopes were not fulfilled and Munster, still thinking he had not been given sufficient money or patronage, remained bitter to the end.

Queen Adelaide attended the dying William devotedly, not going to bed herself for more than ten days. William died in the early hours of the morning of 20 June 1837 at

William was "very much shaken and affected" by the death of his eldest daughter, Sophia, Lady de L'Isle and Dudley, in childbirth in April 1837. William and his eldest son, George, Earl of Munster, were estranged at the time, but William hoped that a letter of condolence from Munster signalled a reconciliation. His hopes were not fulfilled and Munster, still thinking he had not been given sufficient money or patronage, remained bitter to the end.

Queen Adelaide attended the dying William devotedly, not going to bed herself for more than ten days. William died in the early hours of the morning of 20 June 1837 at

As William had no living legitimate issue, the Crown of the United Kingdom passed to his niece Princess Victoria, the only legitimate child of

As William had no living legitimate issue, the Crown of the United Kingdom passed to his niece Princess Victoria, the only legitimate child of

Vol. III, p. 261

* ''5 April 1770'':

pp. 32

50

** ''1831'': Knight of the House Order of Fidelity ** ''1831'': Knight Grand Cross of the Zähringer Lion * : ''21 February 1834'':

William IV

at the official website of the British monarchy

Digitised private and official papers of William IV

at the Royal Collection * , - {{DEFAULTSORT:William 04 1765 births 1837 deaths 18th-century British people 19th-century British monarchs 18th-century Royal Navy personnel 19th-century Royal Navy personnel Royal Navy personnel of the American Revolutionary War Burials at St George's Chapel, Windsor Castle Dukes of Clarence Peers of Great Britain created by George III Earls of Munster Peers of Ireland created by George III Fellows of the Society of Antiquaries of London Great Masters of the Order of the Bath Hanoverian princes Kings of Hanover Knights of the Garter Knights of the Thistle Lord High Admirals Members of the Privy Council of Great Britain Monarchs of the United Kingdom People from Westminster Princes of Great Britain Princes of the United Kingdom Knights of the Golden Fleece of Spain Royal Navy personnel of the Napoleonic Wars Freemasons of the United Grand Lodge of England Monarchs of the Isle of Man British princes Children of George III of the United Kingdom Military personnel from London Sons of kings

King of Hanover

The King of Hanover (German: ''König von Hannover'') was the official title of the head of state and hereditary ruler of the Kingdom of Hanover, beginning with the proclamation of King George III of the United Kingdom, as "King of Hanover" dur ...

from 26 June 1830 until his death in 1837. The third son of George III

George III (George William Frederick; 4 June 173829 January 1820) was King of Great Britain and of Ireland from 25 October 1760 until his death in 1820. Both kingdoms were in a personal union under him until the Acts of Union 1800 merged them ...

, William succeeded his elder brother George IV, becoming the last king and penultimate monarch of Britain's House of Hanover

The House of Hanover (german: Haus Hannover), whose members are known as Hanoverians, is a European royal house of German origin that ruled Hanover, Great Britain, and Ireland at various times during the 17th to 20th centuries. The house orig ...

.

William served in the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

in his youth, spending time in North America

North America is a continent in the Northern Hemisphere and almost entirely within the Western Hemisphere. It is bordered to the north by the Arctic Ocean, to the east by the Atlantic Ocean, to the southeast by South America and the Car ...

and the Caribbean

The Caribbean (, ) ( es, El Caribe; french: la Caraïbe; ht, Karayib; nl, De Caraïben) is a region of the Americas that consists of the Caribbean Sea, its islands (some surrounded by the Caribbean Sea and some bordering both the Caribbean Se ...

, and was later nicknamed the "Sailor King". In 1789, he was created Duke of Clarence and St Andrews

Duke of Clarence and St Andrews was a title awarded to a prince of the British Royal family. The creation was in the Peerage of Great Britain.

While there had been several creations of Dukes of Clarence (and there was later a Duke of Clarenc ...

. In 1827, he was appointed Britain's first Lord High Admiral since 1709. As his two elder brothers died without leaving legitimate issue, he inherited the throne when he was 64 years old. His reign saw several reforms: the Poor Law

In English and British history, poor relief refers to government and ecclesiastical action to relieve poverty. Over the centuries, various authorities have needed to decide whose poverty deserves relief and also who should bear the cost of hel ...

was updated, child labour

Child labour refers to the exploitation of children through any form of work that deprives children of their childhood, interferes with their ability to attend regular school, and is mentally, physically, socially and morally harmful. Such e ...

restricted, slavery abolished in nearly all of the British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts esta ...

, and the electoral system refashioned by the Reform Acts of 1832. Although William did not engage in politics as much as his brother or his father, he was the last British monarch to appoint a prime minister contrary to the will of Parliament

In modern politics, and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

. He granted his German kingdom a short-lived liberal constitution.

At the time of his death, William had no surviving legitimate children, but he was survived by eight of the ten illegitimate children he had by the actress Dorothea Jordan

Dorothea Jordan, née Bland (21 November 17615 July 1816), was an Anglo-Irish actress, as well as a courtesan. She was the long-time mistress (lover), mistress of Duke of Clarence, Prince William, Duke of Clarence, later William IV, and the moth ...

, with whom he cohabited for twenty years. Late in life, he married and apparently remained faithful to Princess Adelaide of Saxe-Meiningen

, house = Saxe-Meiningen

, father = Georg I, Duke of Saxe-Meiningen

, mother = Princess Louise Eleonore of Hohenlohe-Langenburg

, birth_date =

, birth_place = Meiningen, Saxe-Meiningen, Holy ...

. William was succeeded by his niece Victoria

Victoria most commonly refers to:

* Victoria (Australia), a state of the Commonwealth of Australia

* Victoria, British Columbia, provincial capital of British Columbia, Canada

* Victoria (mythology), Roman goddess of Victory

* Victoria, Seychelle ...

in the United Kingdom and his brother Ernest Augustus in Hanover.

Early life

William was born in the early hours of the morning on 21 August 1765 at Buckingham House, the third child and son of King George III and

William was born in the early hours of the morning on 21 August 1765 at Buckingham House, the third child and son of King George III and Queen Charlotte

Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz (Sophia Charlotte; 19 May 1744 – 17 November 1818) was Queen of Great Britain and of Ireland as the wife of King George III from their marriage on 8 September 1761 until the union of the two kingdoms ...

. He had two elder brothers, George, Prince of Wales, and Prince Frederick (later Duke of York and Albany

Duke of York and Albany was a title of nobility in the Peerage of Great Britain. The title was created three times during the 18th century and was usually given to the second son of British monarchs. The predecessor titles in the English and Sc ...

), and was not expected to inherit the Crown. He was baptised in the Great Council Chamber of St James's Palace

St James's Palace is the most senior royal palace in London, the capital of the United Kingdom. The palace gives its name to the Court of St James's, which is the monarch's royal court, and is located in the City of Westminster in London. Altho ...

on 20 September 1765. His godparents were the King's siblings: Prince William Henry, Duke of Gloucester and Edinburgh

Prince William Henry, Duke of Gloucester and Edinburgh, (25 November 1743 – 25 August 1805), was a grandson of King George II and a younger brother of George III of the United Kingdom.

Life

Youth

Prince William Henry was born at Leicester ...

; Prince Henry Prince Henry (or Prince Harry) may refer to:

People

*Henry the Young King (1155–1183), son of Henry II of England, who was crowned king but predeceased his father

*Prince Henry the Navigator of Portugal (1394–1460)

*Henry, Duke of Cornwall (Ja ...

(later Duke of Cumberland and Strathearn

Duke of Cumberland and Strathearn was a title in the Peerage of Great Britain that was conferred upon a member of the British royal family. It was named after the county of Cumberland in England, and after Strathearn in Scotland.

History

T ...

); and Princess Augusta, Hereditary Duchess of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel.

William spent most of his early life in Richmond

Richmond most often refers to:

* Richmond, Virginia, the capital of Virginia, United States

* Richmond, London, a part of London

* Richmond, North Yorkshire, a town in England

* Richmond, British Columbia, a city in Canada

* Richmond, California, ...

and at Kew Palace

Kew Palace is a British royal palace within the grounds of Kew Gardens on the banks of the River Thames. Originally a large complex, few elements of it survive. Dating to 1631 but built atop the undercroft of an earlier building, the main surv ...

, where he was educated by private tutors. At the age of thirteen, he joined the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

as a midshipman

A midshipman is an officer of the lowest rank, in the Royal Navy, United States Navy, and many Commonwealth navies. Commonwealth countries which use the rank include Canada (Naval Cadet), Australia, Bangladesh, Namibia, New Zealand, South Afr ...

, in Admiral Digby's squadron. For four years the lieutenant of his watch was Richard Goodwin Keats

Admiral Sir Richard Goodwin Keats (16 January 1757 – 5 April 1834) was a British naval officer who fought throughout the American Revolution, French Revolutionary War and Napoleonic War. He retired in 1812 due to ill health and was made Comm ...

with whom he formed a life-long friendship and whom he described as the one to whom he owed all his professional knowledge. He was present at the Battle of Cape St Vincent in 1780, when the ''San Julián'' struck her colours to his ship. His experiences in the navy seem to have been little different from those of other midshipmen, though in contrast to other sailors he was accompanied on board ship by a tutor. He did his share of the cooking and got arrested with his shipmates after a drunken brawl in Gibraltar

)

, anthem = " God Save the King"

, song = " Gibraltar Anthem"

, image_map = Gibraltar location in Europe.svg

, map_alt = Location of Gibraltar in Europe

, map_caption = United Kingdom shown in pale green

, mapsize =

, image_map2 = Gib ...

; he was hastily released from custody after his identity became known.

William served in New York during the American War of Independence

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

, making him the only member of the British royal family to visit America up to and through the American Revolution

The American Revolution was an ideological and political revolution that occurred in British America between 1765 and 1791. The Americans in the Thirteen Colonies formed independent states that defeated the British in the American Revolut ...

. While William was in America, George Washington

George Washington (February 22, 1732, 1799) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first president of the United States from 1789 to 1797. Appointed by the Continental Congress as commander of th ...

approved a plot to kidnap him, writing:

The spirit of enterprise so conspicuous in your plan for surprising in their quarters and bringing off the Prince William Henry and Admiral Digby merits applause; and you have my authority to make the attempt in any manner, and at such a time, as your judgment may direct. I am fully persuaded, that it is unnecessary to caution you against offering insult or indignity to the persons of the Prince or Admiral...The plot did not come to fruition; the British heard of it and assigned guards to William, who had until then walked around New York unescorted. In September 1781, William held court at the

Manhattan

Manhattan (), known regionally as the City, is the most densely populated and geographically smallest of the five boroughs of New York City. The borough is also coextensive with New York County, one of the original counties of the U.S. state ...

home of Governor Robertson. In attendance were Mayor David Mathews

David Mathews ( – July 28, 1800) was an American lawyer and politician from New York City. He was a Loyalist during the American Revolutionary War and was the 43rd and last Colonial Mayor of New York City from 1776 until 1783. As New York City ...

, Admiral Digby, and General Delancey.

William became a lieutenant in 1785 and captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police department, election precinct, e ...

of the following year. In late 1786, he was stationed in the West Indies

The West Indies is a subregion of North America, surrounded by the North Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea that includes 13 independent island countries and 18 dependencies and other territories in three major archipelagos: the Greater A ...

under Horatio Nelson

Vice-Admiral Horatio Nelson, 1st Viscount Nelson, 1st Duke of Bronte (29 September 1758 – 21 October 1805) was a British flag officer in the Royal Navy. His inspirational leadership, grasp of strategy, and unconventional tactics brought abo ...

, who wrote of William: "In his professional line, he is superior to two-thirds, I am sure, of the aval

''Aval'' () may refer to:

* ''Aval'' (1967 film)

* ''Aval'' (1972 film)

* ''Aval'' (2017 film)

* ''Aval'' (TV series), a 2011 Indian Tamil-language family soap opera

{{disambiguation ...

list; and in attention to orders, and respect to his superior officer, I hardly know his equal." The two were great friends, and dined together almost nightly. At Nelson's wedding, William insisted on giving the bride away. He was given command of the frigate in 1788, and was promoted to rear-admiral

Rear admiral is a senior naval flag officer rank, equivalent to a major general and air vice marshal and above that of a commodore and captain, but below that of a vice admiral. It is regarded as a two star "admiral" rank. It is often regarded ...

while commanding the following year.

William sought to be made a duke

Duke is a male title either of a monarch ruling over a duchy, or of a member of royalty, or nobility. As rulers, dukes are ranked below emperors, kings, grand princes, grand dukes, and sovereign princes. As royalty or nobility, they are ran ...

like his elder brothers, and to receive a similar parliamentary grant, but his father was reluctant. To put pressure on him, William threatened to stand for the British House of Commons

The House of Commons is the lower house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Like the upper house, the House of Lords, it meets in the Palace of Westminster in London, England.

The House of Commons is an elected body consisting of 650 mem ...

for the constituency of Totnes

Totnes ( or ) is a market town and civil parishes in England, civil parish at the head of the estuary of the River Dart in Devon, England, within the South Devon Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty. It is about west of Paignton, about west-so ...

in Devon. Appalled at the prospect of his son making his case to the voters, George III created him Duke of Clarence and St Andrews

Duke of Clarence and St Andrews was a title awarded to a prince of the British Royal family. The creation was in the Peerage of Great Britain.

While there had been several creations of Dukes of Clarence (and there was later a Duke of Clarenc ...

and Earl of Munster on 16 May 1789, supposedly saying: "I well know it is another vote added to the Opposition." William's political record was inconsistent and, like many politicians of the time, cannot be ascribed to a single party. However, he allied himself publicly with the Whigs, as did his elder brothers, who were known to be in conflict with the political positions of their father.

Military service and politics

William ceased his active service in the Royal Navy in 1790. When Britain declared war on France in 1793, he was eager to serve his country and expected to be given a command but was not, perhaps at first because he had broken his arm by falling down some stairs drunk, but later perhaps because he gave a speech in the

William ceased his active service in the Royal Navy in 1790. When Britain declared war on France in 1793, he was eager to serve his country and expected to be given a command but was not, perhaps at first because he had broken his arm by falling down some stairs drunk, but later perhaps because he gave a speech in the House of Lords

The House of Lords, also known as the House of Peers, is the Bicameralism, upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Membership is by Life peer, appointment, Hereditary peer, heredity or Lords Spiritual, official function. Like the ...

opposing the war. The following year he spoke in favour of the war, and expected a command after his change of heart; none came. The Admiralty did not reply to his request. He did not lose hope of being appointed to an active post. In 1798 he was made an admiral

Admiral is one of the highest ranks in some navies. In the Commonwealth nations and the United States, a "full" admiral is equivalent to a "full" general in the army or the air force, and is above vice admiral and below admiral of the fleet, ...

, but the rank was purely nominal. Despite repeated petitions, he was never given a command throughout the Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) were a series of major global conflicts pitting the French Empire and its allies, led by Napoleon I, against a fluctuating array of European states formed into various coalitions. It produced a period of Fren ...

. In 1811, he was appointed to the honorary position of Admiral of the Fleet. In 1813, he came nearest to involvement in actual fighting, when he visited the British troops fighting in the Low Countries

The term Low Countries, also known as the Low Lands ( nl, de Lage Landen, french: les Pays-Bas, lb, déi Niddereg Lännereien) and historically called the Netherlands ( nl, de Nederlanden), Flanders, or Belgica, is a coastal lowland region in N ...

. Watching the bombardment of Antwerp

Antwerp (; nl, Antwerpen ; french: Anvers ; es, Amberes) is the largest city in Belgium by area at and the capital of Antwerp Province in the Flemish Region. With a population of 520,504,

from a church steeple, he came under fire, and a bullet pierced his coat.

Instead of serving at sea, William spent time in the House of Lords, where he spoke in opposition to the abolition of slavery

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery. In Western Europe and the Americas, abolitionism was a historic movement that sought to end the Atlantic slave trade and liberate the enslaved people.

The British ...

, which still existed in the British colonies. Freedom would do the slaves little good, he argued. He had travelled widely and, in his eyes, the living standard among freemen in the Highlands and Islands

The Highlands and Islands is an area of Scotland broadly covering the Scottish Highlands, plus Orkney, Shetland and Outer Hebrides (Western Isles).

The Highlands and Islands are sometimes defined as the area to which the Crofters' Act of 1886 ...

of Scotland was worse than that among slaves in the West Indies

The West Indies is a subregion of North America, surrounded by the North Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea that includes 13 independent island countries and 18 dependencies and other territories in three major archipelagos: the Greater A ...

. His experience in the Caribbean, where he "quickly absorbed the plantation owners' views about slavery", lent weight to his position, which was perceived as well-argued and just by some of his contemporaries. In his first speech before Parliament he called himself "an attentive observer of the state of the negroes" who found them well cared for and "in a state of humble happiness". Others thought it "shocking that so young a man, under no bias of interest, should be earnest in continuance of the slave trade". In his speech to the House, William insulted William Wilberforce

William Wilberforce (24 August 175929 July 1833) was a British politician, philanthropist and leader of the movement to abolish the slave trade. A native of Kingston upon Hull, Yorkshire, he began his political career in 1780, eventually becom ...

, the leading abolitionist, saying: "the proponents of the abolition are either fanatics or hypocrites, and in one of those classes I rank Mr. Wilberforce". On other issues he was more liberal, such as supporting moves to abolish penal laws against dissenting Christians. He also opposed efforts to bar those found guilty of adultery

Adultery (from Latin ''adulterium'') is extramarital sex that is considered objectionable on social, religious, moral, or legal grounds. Although the sexual activities that constitute adultery vary, as well as the social, religious, and legal ...

from remarriage.

Relationships and marriage

From 1791, William lived with an Irish actress,Dorothea Bland

Dorothea Jordan, née Bland (21 November 17615 July 1816), was an Anglo-Irish actress, as well as a courtesan. She was the long-time mistress of Prince William, Duke of Clarence, later William IV, and the mother of ten illegitimate children by ...

, better known by her stage name, Mrs. Jordan, the title "Mrs." being assumed at the start of her stage career to explain an inconvenient pregnancy and "Jordan" because she had "crossed the water" from Ireland to Britain. He appeared to enjoy the domesticity of his life with Mrs. Jordan, remarking to a friend: "Mrs. Jordan is a very good creature, very domestic and careful of her children. To be sure she is absurd sometimes and has her humours. But there are such things more or less in all families." The couple, while living quietly, enjoyed entertaining, with Mrs. Jordan writing in late 1809: "We shall have a full and merry house this Christmas, 'tis what the dear Duke delights in." George III was accepting of his son's relationship with the actress (though recommending that he halve her allowance); in 1797, he created William the Ranger of Bushy Park

Bushy Park in the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames is the second largest of London's Royal Parks, at in area, after Richmond Park. The park, most of which is open to the public, is immediately north of Hampton Court Palace and Hampton ...

, which included a large residence, Bushy House

Bushy House is a Grade II* listed former residence of King William IV and Queen Adelaide in Teddington, London, which Lord Halifax had constructed for his own enjoyment on the site of a previous house Upper Lodge, Bushy Park, between 1714 and 1 ...

, for William's growing family. William used Bushy as his principal residence until he became king. His London residence, Clarence House

Clarence House is a royal residence on The Mall in the City of Westminster, London. It was built in 1825–1827, adjacent to St James's Palace, for the Duke of Clarence, the future king William IV.

Over the years, it has undergone much exte ...

, was constructed to the designs of John Nash between 1825 and 1827.

The couple had ten illegitimate children—five sons and five daughters—nine of whom were named after William's siblings; each was given the surname " FitzClarence".Weir, pp. 303–304. Their affair lasted for twenty years before ending in 1811. Mrs. Jordan had no doubt as to the reason for the break-up: "Money, money, my good friend, has, I am convinced made HIM at this moment the most wretched of men", adding, "With all his excellent qualities, his domestic ''virtues'', his love for his ''lovely'' children, what must he not at this moment suffer?" She was given a financial settlement of £4,400 () per year and custody of her daughters on condition that she did not resume the stage. When she resumed acting in an effort to repay debts incurred by the husband of one of her daughters from a previous relationship, William took custody of the daughters and stopped paying the £1,500 () designated for their maintenance. After Mrs. Jordan's acting career began to fail, she fled to France to escape her creditors, and died, impoverished, near Paris in 1816.

Before he met Mrs. Jordan, William had an illegitimate son whose mother is unknown; the son, also called William, drowned off Madagascar

Madagascar (; mg, Madagasikara, ), officially the Republic of Madagascar ( mg, Repoblikan'i Madagasikara, links=no, ; french: République de Madagascar), is an island country in the Indian Ocean, approximately off the coast of East Africa ...

in HMS ''Blenheim'' in February 1807. Caroline von Linsingen, whose father was a general in the Hanoverian infantry, claimed to have had a son, Heinrich, by William in around 1790 but William was not in Hanover at the time that she claims, and the story is considered implausible by historians.

Deeply in debt, William made multiple attempts at marrying a wealthy heiress such as

Deeply in debt, William made multiple attempts at marrying a wealthy heiress such as Catherine Tylney-Long

Catherine Tylney-Long (2 October 1789 – 12 September 1825) was a 19th-century British heiress, known as "The Wiltshire Heiress."

Life

She was the eldest daughter of Sir James Tylney-Long, 7th Baronet, of Draycot, Wiltshire. Her only brother ...

, but his suits were unsuccessful. Following the death of William's niece Princess Charlotte of Wales Princess Charlotte of Wales may refer to:

* Princess Charlotte of Wales (1796–1817), the only child of George, Prince of Wales, later King George IV of the United Kingdom

** Princess Charlotte of Wales (1812 EIC ship), a ship named after the pri ...

, then second-in-line to the British throne, in 1817, George III was left with twelve children, but no legitimate grandchildren. The race was on among his sons, the royal duke

Duke is a male title either of a monarch ruling over a duchy, or of a member of royalty, or nobility. As rulers, dukes are ranked below emperors, kings, grand princes, grand dukes, and sovereign princes. As royalty or nobility, they are ranke ...

s, to marry and produce an heir. William had great advantages in this race—his two older brothers were both childless and estranged from their wives, who were both beyond childbearing age anyway, and William was the healthiest of the three. If he lived long enough, he would almost certainly ascend the British and Hanoverian thrones, and have the opportunity to sire the next monarch. William's initial choices of potential wives either met with the disapproval of his eldest brother, the Prince of Wales, or turned him down. His younger brother Prince Adolphus, Duke of Cambridge

Prince Adolphus, Duke of Cambridge, (Adolphus Frederick; 24 February 1774 – 8 July 1850) was the tenth child and seventh son of the British king George III and Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz. He held the title of Duke of Cambridge from 18 ...

, was sent to Germany to scout out the available Protestant princesses; he came up with Princess Augusta of Hesse-Kassel

Princess Augusta of Hesse-Kassel (Augusta Wilhelmina Louisa; 25 July 1797 – 6 April 1889) was the wife of Prince Adolphus, Duke of Cambridge, the tenth-born child, and seventh son, of George III of the United Kingdom and Charlotte of Meckle ...

, but her father Frederick Frederick may refer to:

People

* Frederick (given name), the name

Nobility

Anhalt-Harzgerode

*Frederick, Prince of Anhalt-Harzgerode (1613–1670)

Austria

* Frederick I, Duke of Austria (Babenberg), Duke of Austria from 1195 to 1198

* Frederick ...

declined the match. Two months later, the Duke of Cambridge married Augusta himself. Eventually, a princess was found who was amiable, home-loving, and was willing to accept, even enthusiastically welcoming William's nine surviving children, several of whom had not yet reached adulthood. In the Drawing Room at Kew Palace

Kew Palace is a British royal palace within the grounds of Kew Gardens on the banks of the River Thames. Originally a large complex, few elements of it survive. Dating to 1631 but built atop the undercroft of an earlier building, the main surv ...

on 11 July 1818, William married Princess Adelaide of Saxe-Meiningen

, house = Saxe-Meiningen

, father = Georg I, Duke of Saxe-Meiningen

, mother = Princess Louise Eleonore of Hohenlohe-Langenburg

, birth_date =

, birth_place = Meiningen, Saxe-Meiningen, Holy ...

.

William's marriage, which lasted almost twenty years until his death, was a happy one. Adelaide took both William and his finances in hand. For their first year of marriage, the couple lived in economical fashion in Germany. William's debts were soon on the way to being paid, especially since Parliament had voted him an increased allowance, which he reluctantly accepted after his requests to have it increased further were refused. William is not known to have had mistresses after his marriage. The couple had two short-lived daughters and Adelaide suffered three miscarriages.Ziegler, p. 126. Despite this, false rumours that she was pregnant persisted into William's reign—he dismissed them as "damned stuff".

Lord High Admiral

William's elder brother, the Prince of Wales, had been

William's elder brother, the Prince of Wales, had been Prince Regent

A prince regent or princess regent is a prince or princess who, due to their position in the line of succession, rules a monarchy as regent in the stead of a monarch regnant, e.g., as a result of the sovereign's incapacity (minority or illness ...

since 1811 because of the mental illness of their father. In 1820, George III died and the Prince Regent became George IV. William, Duke of Clarence, was now second in the line of succession, preceded only by his brother, Frederick, Duke of York. Reformed since his marriage, William walked for hours, ate relatively frugally, and the only drink he imbibed in quantity was barley water

Barley water is a traditional drink consumed in various parts of the world. It is made by boiling barley grains in water, then (usually) straining to remove the grains, and possibly adding other ingredients, for example sugar.

Variations

*Kykeon ...

flavoured with lemon. Both of his older brothers were unhealthy, and it was considered only a matter of time before he became king. When Frederick died in 1827, William, then more than 60 years old, became heir presumptive. Later that year, the incoming Prime Minister, George Canning

George Canning (11 April 17708 August 1827) was a British Tory statesman. He held various senior cabinet positions under numerous prime ministers, including two important terms as Foreign Secretary, finally becoming Prime Minister of the Unit ...

, appointed him to the office of Lord High Admiral, which had been in commission (that is, exercised by a board rather than by a single individual) since 1709. While in office, William had repeated conflicts with his Council, which was composed of Admiralty

Admiralty most often refers to:

*Admiralty, Hong Kong

*Admiralty (United Kingdom), military department in command of the Royal Navy from 1707 to 1964

*The rank of admiral

*Admiralty law

Admiralty can also refer to:

Buildings

* Admiralty, Traf ...

officers. Things finally came to a head in 1828 when, as Lord High Admiral, he put to sea with a squadron of ships, leaving no word of where they were going, and remaining away for ten days. The King requested his resignation through the Prime Minister, Arthur Wellesley, Duke of Wellington; he complied.

Despite the difficulties William experienced, he did considerable good as Lord High Admiral. He abolished the cat o' nine tails

The cat o' nine tails, commonly shortened to the cat, is a type of multi-tailed whip or flail that originated as an implement for severe physical punishment, notably in the Royal Navy and British Army, and as a judicial punishment in Britain ...

for most offences other than mutiny

Mutiny is a revolt among a group of people (typically of a military, of a crew or of a crew of pirates) to oppose, change, or overthrow an organization to which they were previously loyal. The term is commonly used for a rebellion among member ...

, attempted to improve the standard of naval gunnery, and required regular reports of the condition and preparedness of each ship. He commissioned the first steam warship and advocated the construction of more. Holding the office permitted him to make mistakes and learn from them—a process that might have been far more costly if he had not learnt before becoming king that he should act only with the advice of his councillors.

William spent much of his remaining time during his brother's reign in the House of Lords. He supported the Catholic Emancipation

Catholic emancipation or Catholic relief was a process in the kingdoms of Great Britain and Ireland, and later the combined United Kingdom in the late 18th century and early 19th century, that involved reducing and removing many of the restricti ...

Bill against the opposition of his younger brother, Ernest Augustus, Duke of Cumberland, describing the latter's position on the Bill as "infamous", to Cumberland's outrage.Ziegler, p. 143. George IV's health was increasingly bad; it was obvious by early 1830 that he was near death. The King took his leave of his younger brother at the end of May, stating, "God's will be done. I have injured no man. It will all rest on you then." William's genuine affection for his older brother could not mask his rising anticipation that he would soon be king.

Reign

Early reign

When King George IV died on 26 June 1830 without surviving legitimate issue, William succeeded him as King William IV. Aged 64, he was the oldest person to that point to assume the British throne, a distinction he would hold until surpassed by

When King George IV died on 26 June 1830 without surviving legitimate issue, William succeeded him as King William IV. Aged 64, he was the oldest person to that point to assume the British throne, a distinction he would hold until surpassed by Charles III

Charles III (Charles Philip Arthur George; born 14 November 1948) is King of the United Kingdom and the 14 other Commonwealth realms. He was the longest-serving heir apparent and Prince of Wales and, at age 73, became the oldest person to ...

in 2022.

Unlike his extravagant brother, William was unassuming, discouraging pomp and ceremony. In contrast to George IV, who tended to spend most of his time in Windsor Castle

Windsor Castle is a royal residence at Windsor in the English county of Berkshire. It is strongly associated with the English and succeeding British royal family, and embodies almost a millennium of architectural history.

The original cast ...

, William was known, especially early in his reign, to walk, unaccompanied, through London or Brighton

Brighton () is a seaside resort and one of the two main areas of the City of Brighton and Hove in the county of East Sussex, England. It is located south of London.

Archaeological evidence of settlement in the area dates back to the Bronze A ...

. Until the Reform Crisis eroded his standing, he was very popular among the people, who saw him as more approachable and down-to-earth than his brother.

The King immediately proved himself a conscientious worker. The Prime Minister, Wellington, stated that he had done more business with King William in ten minutes than he had with George IV in as many days. Lord Brougham

Henry Peter Brougham, 1st Baron Brougham and Vaux, (; 19 September 1778 – 7 May 1868) was a British statesman who became Lord High Chancellor and played a prominent role in passing the 1832 Reform Act and 1833 Slavery Abolition Act. ...

described him as an excellent man of business, asking enough questions to help him understand the matter—whereas George IV feared to ask questions lest he display his ignorance and George III would ask too many and then not wait for a response.

The King did his best to endear himself to the people. Charlotte Williams-Wynn wrote shortly after his accession: "Hitherto the King has been indefatigable in his efforts to make himself popular, and do good natured and amiable things in every possible instance." Emily Eden

Emily Eden (3 March 1797 – 5 August 1869) was an English poet and novelist who gave witty accounts of English life in the early 19th century. She wrote a celebrated account of her travels in India, and two novels that sold well. She was also a ...

noted: "He is an immense improvement on the last unforgiving animal, who died growling sulkily in his den at Windsor. This man at least ''wishes'' to make everybody happy, and everything he has done has been benevolent."

William dismissed his brother's French chefs and German band, replacing them with English ones to public approval. He gave much of George IV's art collection to the nation, and halved the royal stud

Stud may refer to the following terms:

Animals

* Stud (animal), an animal retained for breeding

** Stud farm, a property where livestock are bred

Arts and entertainment

* Stud (band), a British progressive rock group

* The Stud (bar), a gay ba ...

. George had begun an extensive (and expensive) renovation of Buckingham Palace

Buckingham Palace () is a London royal residence and the administrative headquarters of the monarch of the United Kingdom. Located in the City of Westminster, the palace is often at the centre of state occasions and royal hospitality. It ...

; William refused to reside there, and twice tried to give the palace away, once to the Army as a barracks, and once to Parliament after the Houses of Parliament

The Palace of Westminster serves as the meeting place for both the House of Commons and the House of Lords, the two houses of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Informally known as the Houses of Parliament, the Palace lies on the north bank ...

burned down in 1834. His informality could be startling: when in residence at the Royal Pavilion

The Royal Pavilion, and surrounding gardens, also known as the Brighton Pavilion, is a Grade I listed former royal residence located in Brighton, England. Beginning in 1787, it was built in three stages as a seaside retreat for George IV of t ...

in Brighton, King William used to send to the hotels for a list of their guests and invite anyone he knew to dinner, urging guests not to "bother about clothes. The Queen does nothing but embroider flowers after dinner."

Upon taking the throne, William did not forget his nine surviving illegitimate children, creating his eldest son Earl of Munster and granting the other children the precedence of a daughter or a younger son of a marquess. Despite this, his children importuned for greater opportunities, disgusting elements of the press who reported that the "impudence and rapacity of the FitzJordans is unexampled". The relationship between William and his sons "was punctuated by a series of savage and, for the King at least, painful quarrels" over money and honours. His daughters, on the other hand, proved an ornament to his court, as, "They are all, you know, pretty and lively, and make society in a way that real princesses could not."

Reform crisis

At the time, the death of the monarch required fresh elections and, in the general election of 1830, Wellington'sTories

A Tory () is a person who holds a political philosophy known as Toryism, based on a British version of traditionalism and conservatism, which upholds the supremacy of social order as it has evolved in the English culture throughout history. Th ...

lost ground to the Whigs under Lord Grey, though the Tories still had the largest number of seats. With the Tories bitterly divided, Wellington was defeated in the House of Commons in November, and Lord Grey formed a government. Grey pledged to reform the electoral system, which had seen few changes since the fifteenth century. The inequities in the system were great; for example, large towns such as Manchester

Manchester () is a city in Greater Manchester, England. It had a population of 552,000 in 2021. It is bordered by the Cheshire Plain to the south, the Pennines to the north and east, and the neighbouring city of Salford to the west. The t ...

and Birmingham

Birmingham ( ) is a city and metropolitan borough in the metropolitan county of West Midlands in England. It is the second-largest city in the United Kingdom with a population of 1.145 million in the city proper, 2.92 million in the West ...

elected no members (though they were part of county constituencies), while small boroughs, known as rotten

Rotten may refer to:

* Axl Rotten, ring name of American professional wrestler Brian Knighton (1971–2016)

* Bonnie Rotten, American former pornographic actress, feature dancer, fetish model, and director

* Ian Rotten, ring name of American profe ...

or pocket borough

A rotten or pocket borough, also known as a nomination borough or proprietorial borough, was a parliamentary borough or constituency in England, Great Britain, or the United Kingdom before the Reform Act 1832, which had a very small electorat ...

s—such as Old Sarum

Old Sarum, in Wiltshire, South West England, is the now ruined and deserted site of the earliest settlement of Salisbury. Situated on a hill about north of modern Salisbury near the A345 road, the settlement appears in some of the earliest re ...

with just seven voters—elected two members of Parliament each. Often, the rotten boroughs were controlled by great aristocrats, whose nominees were invariably elected by the constituents—who were, most often, their tenants—especially since the secret ballot was not yet used in Parliamentary elections. Landowners who controlled seats were even able to sell them to prospective candidates.

When the First Reform Bill was defeated in the House of Commons in 1831, Grey's ministry urged William to dissolve Parliament, which would lead to a new general election. At first, William hesitated to exercise his prerogative to dissolve Parliament because elections had just been held the year before and the country was in a state of high excitement which might boil over into violence. He was, however, irritated by the conduct of the Opposition, which announced its intention to move the passage of an Address, or resolution, in the House of Lords, against dissolution. Regarding the Opposition's motion as an attack on his prerogative, and at the urgent request of Lord Grey and his ministers, the King prepared to go in person to the House of Lords and

When the First Reform Bill was defeated in the House of Commons in 1831, Grey's ministry urged William to dissolve Parliament, which would lead to a new general election. At first, William hesitated to exercise his prerogative to dissolve Parliament because elections had just been held the year before and the country was in a state of high excitement which might boil over into violence. He was, however, irritated by the conduct of the Opposition, which announced its intention to move the passage of an Address, or resolution, in the House of Lords, against dissolution. Regarding the Opposition's motion as an attack on his prerogative, and at the urgent request of Lord Grey and his ministers, the King prepared to go in person to the House of Lords and prorogue

Prorogation in the Westminster system of government is the action of proroguing, or interrupting, a parliament, or the discontinuance of meetings for a given period of time, without a dissolution of parliament. The term is also used for the period ...

Parliament. The monarch's arrival would stop all debate and prevent passage of the Address.Ziegler, p. 188. When initially told that his horses could not be ready at such short notice, William is supposed to have said, "Then I will go in a hackney cab

A hackney or hackney carriage (also called a cab, black cab, hack or London taxi) is a carriage or car for hire. A hackney of a more expensive or high class was called a remise. A symbol of London and Britain, the black taxi is a common s ...

!" Coach and horses were assembled quickly and he immediately proceeded to Parliament. Said ''The Times'' of the scene before William's arrival, "It is utterly impossible to describe the scene ... The violent tones and gestures of noble Lords ... astonished the spectators, and affected the ladies who were present with visible alarm." Lord Londonderry

Marquess of Londonderry, of the County of Londonderry ( ), is a title in the Peerage of Ireland.

History

The title was created in 1816 for Robert Stewart, 1st Earl of Londonderry. He had earlier represented County Down in the Irish House of ...

brandished a whip, threatening to thrash the Government supporters, and was held back by four of his colleagues. William hastily put on the crown, entered the Chamber, and dissolved Parliament. This forced new elections for the House of Commons, which yielded a great victory for the reformers. But although the Commons was clearly in favour of parliamentary reform, the Lords remained implacably opposed to it.

The crisis saw a brief interlude for the celebration of the King's coronation on 8 September 1831. At first, William wished to dispense with the coronation entirely, feeling that his wearing the crown while proroguing Parliament answered any need. He was persuaded otherwise by traditionalists. He refused, however, to celebrate the coronation in the expensive way his brother had—the 1821 coronation had cost £240,000, of which £16,000 was merely to hire the jewels. At William's instructions, the Privy Council budgeted less than £30,000 for the coronation. When traditionalist Tories threatened to boycott what they called the " Half Crown-nation", the King retorted that they should go ahead, and that he anticipated "greater convenience of room and less heat".

After the rejection of the Second Reform Bill by the House of Lords in October 1831, agitation for reform grew across the country; demonstrations grew violent in so-called "Reform Riots". In the face of popular excitement, the Grey ministry refused to accept defeat, and re-introduced the Bill, despite the continued opposition of peers in the House of Lords. Frustrated by the Lords' obdurate attitude, Grey suggested that the King create a sufficient number of new peers to ensure the passage of the Reform Bill. The King objected—though he had the power to create an unlimited number of peers, he had already created 22 new peers in his Coronation Honours. William reluctantly agreed to the creation of the number of peers sufficient "to secure the success of the bill". However, the King, citing the difficulties with a permanent expansion of the peerage

A peerage is a legal system historically comprising various hereditary titles (and sometimes non-hereditary titles) in a number of countries, and composed of assorted noble ranks.

Peerages include:

Australia

* Australian peers

Belgium

* Belgi ...

, told Grey that the creations must be restricted as much as possible to the eldest sons and collateral heirs of existing peers, so that the created peerages would eventually be absorbed as subsidiary titles. This time, the Lords did not reject the bill outright, but began preparing to change its basic character through amendments. Grey and his fellow ministers decided to resign if the King did not agree to an immediate and large creation to force the bill through in its entirety. The King refused, and accepted their resignations. The King attempted to restore the Duke of Wellington to office, but Wellington had insufficient support to form a ministry and the King's popularity sank to an all-time low. Mud was slung at his carriage and he was publicly hissed. The King agreed to reappoint Grey's ministry, and to create new peers if the House of Lords continued to pose difficulties. Concerned by the threat of the creations, most of the bill's opponents abstained and the 1832 Reform Act

The Representation of the People Act 1832 (also known as the 1832 Reform Act, Great Reform Act or First Reform Act) was an Act of Parliament of the United Kingdom (indexed as 2 & 3 Will. IV c. 45) that introduced major changes to the electo ...

was passed. The mob blamed William's actions on the influence of his wife and brother, and his popularity recovered.

Foreign policy

William distrusted foreigners, particularly anyone French, which he acknowledged as a "prejudice". He also felt strongly that Britain should not interfere in the internal affairs of other nations, which brought him into conflict with the interventionistForeign Secretary

The secretary of state for foreign, Commonwealth and development affairs, known as the foreign secretary, is a minister of the Crown of the Government of the United Kingdom and head of the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office. Seen as ...

, Lord Palmerston

Henry John Temple, 3rd Viscount Palmerston, (20 October 1784 – 18 October 1865) was a British statesman who was twice Prime Minister of the United Kingdom in the mid-19th century. Palmerston dominated British foreign policy during the period ...

. William supported Belgian independence and, after unacceptable Dutch

Dutch commonly refers to:

* Something of, from, or related to the Netherlands

* Dutch people ()

* Dutch language ()

Dutch may also refer to:

Places

* Dutch, West Virginia, a community in the United States

* Pennsylvania Dutch Country

People E ...

and French candidates were put forward, favoured Prince Leopold of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha

Prince Leopold Franz Julius of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha (Vienna, 31 January 1824 – Vienna, 20 May 1884) was a German prince of the House of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha-Koháry.

Born ''Prince Leopold Franz Julius of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld, Duke in Sax ...

, the widower of his niece, Charlotte, as a candidate for the newly created Belgian throne.

Though he had a reputation for tactlessness and buffoonery, William could be shrewd and diplomatic. He foresaw that the potential construction of a canal at Suez would make good relations with Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediter ...

vital to Britain. Later in his reign, he flattered the American ambassador at a dinner by announcing that he regretted not being "born a free, independent American, so much did he respect that nation, which had given birth to George Washington, the greatest man that ever lived". By exercising his personal charm, William assisted in the repair of Anglo-American relations, which had been so deeply damaged during the reign of his father.

King of Hanover

Public perception in Germany was that Britain dictated Hanoverian policy. This was not the case. In 1832, Austrian chancellorKlemens von Metternich

Klemens Wenzel Nepomuk Lothar, Prince of Metternich-Winneburg zu Beilstein ; german: Klemens Wenzel Nepomuk Lothar Fürst von Metternich-Winneburg zu Beilstein (15 May 1773 – 11 June 1859), known as Klemens von Metternich or Prince Metternic ...

introduced laws that curbed fledgling liberal movements in Germany. Lord Palmerston opposed this, and sought William's influence to cause the Hanoverian government to take the same position. The Hanoverian government instead agreed with Metternich, much to Palmerston's dismay, and William declined to intervene. The conflict between William and Palmerston over Hanover was renewed the following year when Metternich called a conference of the German states, to be held in Vienna

en, Viennese

, iso_code = AT-9

, registration_plate = W

, postal_code_type = Postal code

, postal_code =

, timezone = CET

, utc_offset = +1

, timezone_DST ...

, and Palmerston wanted Hanover to decline the invitation. Instead, William's brother Prince Adolphus

Prince Adolphus, Duke of Cambridge, (Adolphus Frederick; 24 February 1774 – 8 July 1850) was the tenth child and seventh son of the British king George III and Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz. He held the title of Duke of Cambridge from 18 ...

, Viceroy of Hanover, accepted, backed fully by William. In 1833, William signed a new constitution for Hanover, which empowered the middle class, gave limited power to the lower classes, and expanded the role of the parliament. The constitution would later be revoked by his brother and successor in Hanover, King Ernest Augustus.

Later reign and death

For the remainder of his reign, William interfered actively in politics only once, in 1834, when he became the last British sovereign to choose a prime minister contrary to the will of Parliament. In 1834, the ministry was facing increasing unpopularity and Lord Grey retired; the

For the remainder of his reign, William interfered actively in politics only once, in 1834, when he became the last British sovereign to choose a prime minister contrary to the will of Parliament. In 1834, the ministry was facing increasing unpopularity and Lord Grey retired; the Home Secretary

The secretary of state for the Home Department, otherwise known as the home secretary, is a senior minister of the Crown in the Government of the United Kingdom. The home secretary leads the Home Office, and is responsible for all national ...

, William Lamb, 2nd Viscount Melbourne

William Lamb, 2nd Viscount Melbourne, (15 March 177924 November 1848), in some sources called Henry William Lamb, was a British Whig politician who served as Home Secretary (1830–1834) and Prime Minister (1834 and 1835–1841). His first pre ...

, replaced him. Melbourne retained most Cabinet members, and his ministry retained an overwhelming majority in the House of Commons. Some members of the Government, however, were anathema to the King, and increasingly left-wing policies concerned him. The previous year Grey had already pushed through legislation

Legislation is the process or result of enrolled bill, enrolling, enactment of a bill, enacting, or promulgation, promulgating laws by a legislature, parliament, or analogous Government, governing body. Before an item of legislation becomes law i ...

reforming the Protestant Church of Ireland

The Church of Ireland ( ga, Eaglais na hÉireann, ; sco, label= Ulster-Scots, Kirk o Airlann, ) is a Christian church in Ireland and an autonomous province of the Anglican Communion. It is organised on an all-Ireland basis and is the second ...

. The Church collected tithe

A tithe (; from Old English: ''teogoþa'' "tenth") is a one-tenth part of something, paid as a contribution to a religious organization or compulsory tax to government. Today, tithes are normally voluntary and paid in cash or cheques or more r ...

s throughout Ireland, supported multiple bishoprics and was wealthy. However, barely an eighth of the Irish population belonged to the Church of Ireland. In some parishes, there were no Church of Ireland members at all, but there was still a priest paid for by tithes collected from the local Catholics and Presbyterians

Presbyterianism is a part of the Reformed tradition within Protestantism that broke from the Roman Catholic Church in Scotland by John Knox, who was a priest at St. Giles Cathedral (Church of Scotland). Presbyterian churches derive their nam ...

, leading to charges that idle priests were living in luxury at the expense of Irish people living at the level of subsistence. Grey's Act had reduced the number of bishoprics by half, abolished some of the sinecures and overhauled the tithe system. Further measures to appropriate the surplus revenues of the Church of Ireland were mooted by the more radical members of the Government, including Lord John Russell

John Russell, 1st Earl Russell, (18 August 1792 – 28 May 1878), known by his courtesy title Lord John Russell before 1861, was a British Whig and Liberal statesman who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1846 to 1852 and a ...

. The King had an especial dislike for Russell, calling him "a dangerous little Radical."

In November 1834, the

In November 1834, the Leader of the House of Commons

The leader of the House of Commons is a minister of the Crown of the Government of the United Kingdom whose main role is organising government business in the House of Commons. The leader is generally a member or attendee of the cabinet of the ...

and Chancellor of the Exchequer

The chancellor of the Exchequer, often abbreviated to chancellor, is a senior minister of the Crown within the Government of the United Kingdom, and head of His Majesty's Treasury. As one of the four Great Offices of State, the Chancellor is ...

, Lord Althorp

John Charles Spencer, 3rd Earl Spencer, (30 May 1782 – 1 October 1845), styled Viscount Althorp from 1783 to 1834, was a British statesman

A statesman or stateswoman typically is a politician who has had a long and respected political care ...

, inherited a peerage, thus removing him from the Commons to the Lords. Melbourne had to appoint a new Commons leader and a new Chancellor (who by long custom, must be drawn from the Commons), but the only candidate whom Melbourne felt suitable to replace Althorp as Commons leader was Lord John Russell, whom William (and many others) found unacceptable due to his radical politics. William claimed that the ministry had been weakened beyond repair and used the removal of Lord Althorp—who had previously indicated that he would retire from politics upon becoming a peer—as the pretext for the dismissal of the entire ministry. With Lord Melbourne gone, William chose to entrust power to a Tory, Sir Robert Peel

Sir Robert Peel, 2nd Baronet, (5 February 1788 – 2 July 1850) was a British Conservative statesman who served twice as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom (1834–1835 and 1841–1846) simultaneously serving as Chancellor of the Exchequer ...

. Since Peel was then in Italy, the Duke of Wellington was provisionally appointed Prime Minister. When Peel returned and assumed leadership of the ministry for himself, he saw the impossibility of governing because of the Whig majority in the House of Commons. Consequently, Parliament was dissolved to force fresh elections. Although the Tories won more seats than in the previous election, they were still in the minority. Peel remained in office for a few months, but resigned after a series of parliamentary defeats. Melbourne was restored to the Prime Minister's office, remaining there for the rest of William's reign, and the King was forced to accept Russell as Commons leader.

The King had a mixed relationship with Lord Melbourne. Melbourne's government mooted more ideas to introduce greater democracy, such as the devolution of powers to the Legislative Council of Lower Canada

The Legislative Council of Lower Canada was the upper house of the bicameral structure of provincial government in Lower Canada until 1838. The upper house consisted of appointed councillors who voted on bills passed up by the Legislative Assembly ...

, which greatly alarmed the King, who feared it would eventually lead to the loss of the colony. At first, the King bitterly opposed these proposals. William exclaimed to Lord Gosford

Earl of Gosford is a title in the Peerage of Ireland. It was created in 1806 for Arthur Acheson, 2nd Viscount Gosford.

The Acheson family descends from the Scottish statesman Sir Archibald Acheson, 1st Baronet of Edinburgh, who later settled ...

, Governor General-designate of Canada: "Mind what you are about in Canada ... mind me, my Lord, the Cabinet is not my Cabinet; they had better take care or by God, I will have them impeached." When William's son Augustus FitzClarence enquired of his father whether the King would be entertaining during Ascot week, William gloomily replied, "I cannot give any dinners without inviting the ministers, and I would rather see the devil than any one of them in my house."Somerset, p. 200. Nevertheless, William approved the Cabinet's recommendations for reform. Despite his disagreements with Melbourne, the King wrote warmly to congratulate the Prime Minister when he triumphed in the adultery case brought against him concerning Lady Caroline Norton—he had refused to permit Melbourne to resign when the case was first brought. The King and Prime Minister eventually found a ''modus vivendi''; Melbourne applying tact and firmness when called for; while William realised that his First Minister was far less radical in his politics than the King had feared.

Both the King and Queen were fond of their niece, Princess Alexandrina Victoria of Kent

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until her death in 1901. Her reign of 63 years and 216 days was longer than that of any previo ...

. Their attempts to forge a close relationship with the girl were frustrated by the conflict between the King and the Princess's widowed mother, the Duchess of Kent

Duchess of Kent is the principal courtesy title used by the wife of the Duke of Kent. There have been four titles referring to Kent since the 18th century. The current duchess is Katharine, the wife of Prince Edward. He inherited the dukedom ...

. The King, angered at what he took to be disrespect from the Duchess to his wife, took the opportunity at what proved to be his final birthday banquet in August 1836 to settle the score. Speaking to those assembled at the banquet, who included the Duchess and Princess, William expressed his hope that he would survive until the Princess was 18 so that the Duchess would never be regent. He said, "I trust to God that my life may be spared for nine months longer ... I should then have the satisfaction of leaving the exercise of the Royal authority to the personal authority of that young lady, heiress presumptive to the Crown, and not in the hands of a person now near me, who is surrounded by evil advisers and is herself incompetent to act with propriety in the situation in which she would be placed." The speech was so shocking that Victoria burst into tears, while her mother sat in silence and was only with difficulty persuaded not to leave immediately after dinner (the two left the next day). William's outburst undoubtedly contributed to Victoria's tempered view of him as "a good old man, though eccentric and singular". William survived, though mortally ill, to the month after Victoria's coming of age. "Poor old man!", Victoria wrote as he was dying, "I feel sorry for him; he was always personally kind to me."

William was "very much shaken and affected" by the death of his eldest daughter, Sophia, Lady de L'Isle and Dudley, in childbirth in April 1837. William and his eldest son, George, Earl of Munster, were estranged at the time, but William hoped that a letter of condolence from Munster signalled a reconciliation. His hopes were not fulfilled and Munster, still thinking he had not been given sufficient money or patronage, remained bitter to the end.

Queen Adelaide attended the dying William devotedly, not going to bed herself for more than ten days. William died in the early hours of the morning of 20 June 1837 at

William was "very much shaken and affected" by the death of his eldest daughter, Sophia, Lady de L'Isle and Dudley, in childbirth in April 1837. William and his eldest son, George, Earl of Munster, were estranged at the time, but William hoped that a letter of condolence from Munster signalled a reconciliation. His hopes were not fulfilled and Munster, still thinking he had not been given sufficient money or patronage, remained bitter to the end.

Queen Adelaide attended the dying William devotedly, not going to bed herself for more than ten days. William died in the early hours of the morning of 20 June 1837 at Windsor Castle

Windsor Castle is a royal residence at Windsor in the English county of Berkshire. It is strongly associated with the English and succeeding British royal family, and embodies almost a millennium of architectural history.

The original cast ...

, where he was buried at St George's Chapel.

Legacy

As William had no living legitimate issue, the Crown of the United Kingdom passed to his niece Princess Victoria, the only legitimate child of

As William had no living legitimate issue, the Crown of the United Kingdom passed to his niece Princess Victoria, the only legitimate child of Prince Edward, Duke of Kent and Strathearn

Prince Edward, Duke of Kent and Strathearn, (Edward Augustus; 2 November 1767 – 23 January 1820) was the fourth son and fifth child of King George III. His only legitimate child became Queen Victoria.

Prince Edward was created Duke of Kent an ...

, George III's fourth son. Under Salic Law

The Salic law ( or ; la, Lex salica), also called the was the ancient Frankish civil law code compiled around AD 500 by the first Frankish King, Clovis. The written text is in Latin and contains some of the earliest known instances of Old Du ...

, a woman could not rule Hanover

Hanover (; german: Hannover ; nds, Hannober) is the capital and largest city of the German state of Lower Saxony. Its 535,932 (2021) inhabitants make it the 13th-largest city in Germany as well as the fourth-largest city in Northern Germany ...

, and so the Hanoverian Crown went to George III's fifth son, the Duke of Cumberland and Teviotdale. William's death thus ended the personal union

A personal union is the combination of two or more states that have the same monarch while their boundaries, laws, and interests remain distinct. A real union, by contrast, would involve the constituent states being to some extent interlink ...

of Britain and Hanover, which had persisted since 1714. The main beneficiaries of his will were his eight surviving children by Mrs. Jordan. Although William is not the direct ancestor of the later monarchs of the United Kingdom, he has many notable descendants through his illegitimate family with Mrs. Jordan, including former Prime Minister David Cameron

David William Donald Cameron (born 9 October 1966) is a British former politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 2010 to 2016 and Leader of the Conservative Party from 2005 to 2016. He previously served as Leader o ...

, TV presenter Adam Hart-Davis

Adam John Hart-Davis (born 4 July 1943) is an English scientist, author, photographer, historian and broadcaster. He presented the BBC television series '' Local Heroes'' and '' What the Romans Did for Us'', the latter spawning several spin-off ...

, and author and statesman Duff Cooper

Alfred Duff Cooper, 1st Viscount Norwich, (22 February 1890 – 1 January 1954), known as Duff Cooper, was a British Conservative Party politician and diplomat who was also a military and political historian.

First elected to Parliament in 19 ...

.

William IV had a short but eventful reign. In Britain, the Reform Crisis marked the ascendancy of the House of Commons and the corresponding decline of the House of Lords, and the King's unsuccessful attempt to remove the Melbourne ministry indicated a reduction in the political influence of the Crown and of the King's influence over the electorate. During the reign of George III, the king could have dismissed one ministry, appointed another, dissolved Parliament, and expected the electorate to vote in favour of the new administration. Such was the result of a dissolution in 1784, after the dismissal of the Fox-North Coalition, and in 1807, after the dismissal of Lord Grenville

William Wyndham Grenville, 1st Baron Grenville, (25 October 175912 January 1834) was a British Pittite Tory politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1806 to 1807, but was a supporter of the Whigs for the duration of ...

. But when William dismissed the Melbourne ministry, the Tories under Peel failed to win the ensuing elections. The monarch's ability to influence the opinion of the electorate, and therefore national policy, had been reduced. None of William's successors has attempted to remove a government or to appoint another against the wishes of Parliament. William understood that as a constitutional monarch he had no power to act against the opinion of Parliament. He said, "I have my view of things, and I tell them to my ministers. If they do not adopt them, I cannot help it. I have done my duty."

During William's reign, the British Parliament enacted major reforms, including the Factory Act of 1833 (preventing child labour), the Slavery Abolition Act 1833

The Slavery Abolition Act 1833 (3 & 4 Will. IV c. 73) was an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom which provided for the gradual abolition of slavery in most parts of the British Empire. It was passed by Earl Grey's reforming administrati ...

(emancipating slaves in the colonies), and the Poor Law Amendment Act 1834

The ''Poor Law Amendment Act 1834'' (PLAA) known widely as the New Poor Law, was an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom passed by the Whig government of Earl Grey. It completely replaced earlier legislation based on the ''Poor Relief ...

(standardising provision for the destitute). William attracted criticism both from reformers, who felt that reform did not go far enough, and from reactionaries, who felt that reform went too far. A modern interpretation sees him as failing to satisfy either political extreme by trying to find a compromise between two bitterly opposed factions, but in the process proving himself more capable as a constitutional monarch than many had supposed.

Honours and arms

British and Hanoverian honours Cokayne, G.E.; Gibbs, Vicary; Doubleday, H. A. (1913). ''The Complete Peerage of England, Scotland, Ireland, Great Britain and the United Kingdom, Extant, Extinct or Dormant'', London: St. Catherine's PressVol. III, p. 261

* ''5 April 1770'':

Knight of the Thistle

A knight is a person granted an honorary title of knighthood by a head of state (including the Pope) or representative for service to the monarch, the church or the country, especially in a military capacity. Knighthood finds origins in the Gr ...

* ''19 April 1782'': Knight of the Garter

The Most Noble Order of the Garter is an order of chivalry founded by Edward III of England in 1348. It is the most senior order of knighthood in the British honours system, outranked in precedence only by the Victoria Cross and the George ...

* ''23 June 1789'': Member of the Privy Council of the United Kingdom

The Privy Council (PC), officially His Majesty's Most Honourable Privy Council, is a formal body of advisers to the sovereign of the United Kingdom. Its membership mainly comprises senior politicians who are current or former members of e ...

* ''2 January 1815'': Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath

The Most Honourable Order of the Bath is a British order of chivalry founded by George I on 18 May 1725. The name derives from the elaborate medieval ceremony for appointing a knight, which involved bathing (as a symbol of purification) as one ...

* ''12 August 1815'': Knight Grand Cross of the Royal Hanoverian Guelphic Order

* ''26 April 1827'': Royal Fellow of the Royal Society

Foreign honours

* Kingdom of Prussia