King Robert I Of Scotland on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Robert I (11 July 1274 – 7 June 1329), popularly known as Robert the Bruce (

Although Robert the Bruce's date of birth is known, his place of birth is less certain, although it is most likely to have been

Although Robert the Bruce's date of birth is known, his place of birth is less certain, although it is most likely to have been

Even after John's accession, Edward still continued to assert his authority over Scotland, and relations between the two kings soon began to deteriorate. The Bruces sided with King Edward against King John and his Comyn allies. Robert the Bruce and his father both considered John a usurper. Against the objections of the Scots, Edward I agreed to hear appeals on cases ruled on by the court of the Guardians that had governed Scotland during the interregnum. A further provocation came in a case brought by Macduff, son of Malcolm, Earl of Fife, in which Edward demanded that John appear in person before the

Even after John's accession, Edward still continued to assert his authority over Scotland, and relations between the two kings soon began to deteriorate. The Bruces sided with King Edward against King John and his Comyn allies. Robert the Bruce and his father both considered John a usurper. Against the objections of the Scots, Edward I agreed to hear appeals on cases ruled on by the court of the Guardians that had governed Scotland during the interregnum. A further provocation came in a case brought by Macduff, son of Malcolm, Earl of Fife, in which Edward demanded that John appear in person before the

In July 1301 King Edward I launched his sixth campaign into Scotland. Though he captured the castles of Bothwell and Turnberry, he did little to damage the Scots' fighting ability, and in January 1302 he agreed to a nine-month truce. It was around this time that Robert the Bruce submitted to Edward, along with other nobles, even though he had been on the side of the Scots until then. There were rumours that

In July 1301 King Edward I launched his sixth campaign into Scotland. Though he captured the castles of Bothwell and Turnberry, he did little to damage the Scots' fighting ability, and in January 1302 he agreed to a nine-month truce. It was around this time that Robert the Bruce submitted to Edward, along with other nobles, even though he had been on the side of the Scots until then. There were rumours that

Bruce, like all his family, had a complete belief in his right to the throne. His ambition was further thwarted by

Bruce, like all his family, had a complete belief in his right to the throne. His ambition was further thwarted by

Six weeks after Comyn was killed in Dumfries, Bruce was crowned King of Scots by Bishop William de Lamberton at

Six weeks after Comyn was killed in Dumfries, Bruce was crowned King of Scots by Bishop William de Lamberton at

By 1314, Bruce had recaptured most of the

By 1314, Bruce had recaptured most of the

The reign of Robert Bruce also included some significant diplomatic achievements. The

The reign of Robert Bruce also included some significant diplomatic achievements. The

Robert died on 7 June 1329, at the Manor of Cardross, near

Robert died on 7 June 1329, at the Manor of Cardross, near

In 1996, a casket was unearthed during construction work. Scientific study by AOC archaeologists in Edinburgh demonstrated that it did indeed contain human tissue and it was of appropriate age. It was reburied in Melrose Abbey in 1998, pursuant to the dying wishes of the King.

and Dr Martin McGregor (University of Glasgow) and Prof Caroline Wilkinson (Face Lab at Liverpool John Moores University).

A 1929 statue of Robert the Bruce is set in the wall of Edinburgh Castle at the entrance, along with one of

A 1929 statue of Robert the Bruce is set in the wall of Edinburgh Castle at the entrance, along with one of

According to a legend, at some point while he was on the run after the 1305 Battle of Methven, Bruce hid in a cave where he observed a spider spinning a web, trying to make a connection from one area of the cave's roof to another. It tried and failed twice, but began again and succeeded on the third attempt. Inspired by this, Bruce returned to inflict a series of defeats on the English, thus winning him more supporters and eventual victory. The story serves to illustrate the maxim: "if at first you don't succeed, try try try again." Other versions have Bruce in a small house watching the spider try to make its connection between two roof beams.

According to a legend, at some point while he was on the run after the 1305 Battle of Methven, Bruce hid in a cave where he observed a spider spinning a web, trying to make a connection from one area of the cave's roof to another. It tried and failed twice, but began again and succeeded on the third attempt. Inspired by this, Bruce returned to inflict a series of defeats on the English, thus winning him more supporters and eventual victory. The story serves to illustrate the maxim: "if at first you don't succeed, try try try again." Other versions have Bruce in a small house watching the spider try to make its connection between two roof beams.

This legend first appears in a much later account, ''

This legend first appears in a much later account, ''

Chronicon Galfridi le Baker de Swynebroke

ed.

The Robert the Bruce Commemoration Trust

Annual Commemorative Robert the Bruce Dinner

Robert the Bruce Heritage Centre

* , - , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Robert the Bruce 1274 births 1329 deaths People from South Ayrshire House of Bruce Guardians of Scotland Norman warriors Scoto-Normans Earls or mormaers of Carrick 13th-century mormaers 14th-century Scottish earls Scottish folklore Scottish people of the Wars of Scottish Independence Scottish knights Scottish generals Scottish rebels Burials at Dunfermline Abbey People temporarily excommunicated by the Catholic Church 13th-century Scottish people 14th-century Scottish monarchs Scottish Roman Catholics Scottish people of English descent Scottish people of French descent Scottish people of Irish descent Medieval legends

Scottish Gaelic

Scottish Gaelic ( gd, Gàidhlig ), also known as Scots Gaelic and Gaelic, is a Goidelic language (in the Celtic branch of the Indo-European language family) native to the Gaels of Scotland. As a Goidelic language, Scottish Gaelic, as well as ...

: ''Raibeart an Bruis''), was King of Scots

The monarch of Scotland was the head of state of the Kingdom of Scotland. According to tradition, the first King of Scots was Kenneth I MacAlpin (), who founded the sovereign state, state in 843. Historically, the Kingdom of Scotland is thoug ...

from 1306 to his death in 1329. One of the most renowned warriors of his generation, Robert eventually led Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a border with England to the southeast and is otherwise surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean to the ...

during the First War of Scottish Independence

The First War of Scottish Independence was the first of a series of wars between English and Scottish forces. It lasted from the English invasion of Scotland in 1296 until the ''de jure'' restoration of Scottish independence with the Treaty o ...

against England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe b ...

. He fought successfully during his reign to regain Scotland's place as an independent kingdom and is now revered in Scotland as a national hero

The title of Hero is presented by various governments in recognition of acts of self-sacrifice to the state, and great achievements in combat or labor. It is originally a Soviet-type honor, and is continued by several nations including Belarus, Ru ...

.

Robert was a fourth great-grandson of King David I

David I or Dauíd mac Maíl Choluim ( Modern: ''Daibhidh I mac haoilChaluim''; – 24 May 1153) was a 12th-century ruler who was Prince of the Cumbrians from 1113 to 1124 and later King of Scotland from 1124 to 1153. The youngest son of Mal ...

, and his grandfather, Robert de Brus, 5th Lord of Annandale

Robert V de Brus (Robert de Brus), 5th Lord of Annandale (ca. 1215 – 31 March or 3 May 1295), was a feudal lord, justice and constable of Scotland and England, a regent of Scotland, and a competitor for the Scottish throne in 1290/92 in the ...

, was one of the claimants to the Scottish throne during the "Great Cause

When the crown of Scotland became vacant in September 1290 on the death of the seven-year-old Queen Margaret, 13 claimants to the throne came forward. Those with the most credible claims were John Balliol, Robert de Brus, 5th Lord of Annandale, ...

". As Earl of Carrick

Earl of Carrick (or Mormaer of Carrick) is the title applied to the ruler of Carrick (now South Ayrshire), subsequently part of the Peerage of Scotland. The position came to be strongly associated with the Scottish crown when Robert the Bruce, ...

, Robert the Bruce supported his family's claim to the Scottish throne and took part in William Wallace

Sir William Wallace ( gd, Uilleam Uallas, ; Norman French: ; 23 August 1305) was a Scottish knight who became one of the main leaders during the First War of Scottish Independence.

Along with Andrew Moray, Wallace defeated an English army a ...

's revolt against Edward I of England

Edward I (17/18 June 1239 – 7 July 1307), also known as Edward Longshanks and the Hammer of the Scots, was King of England and Lord of Ireland from 1272 to 1307. Concurrently, he ruled the duchies of Aquitaine and Gascony as a vassa ...

. Appointed in 1298 as a Guardian of Scotland

The Guardians of Scotland were regents who governed the Kingdom of Scotland from 1286 until 1292 and from 1296 until 1306. During the many years of minority in Scotland's subsequent history, there were many guardians of Scotland and the post was ...

alongside his chief rival for the throne, John Comyn of Badenoch, and William Lamberton

William de Lamberton, sometimes modernized as William Lamberton, (died 20 May 1328) was Bishop of St Andrews from 1297 (consecrated 1298) until his death. Lamberton is renowned for his influential role during the Scottish Wars of Independence. ...

, Bishop of St Andrews

The Bishop of St. Andrews ( gd, Easbaig Chill Rìmhinn, sco, Beeshop o Saunt Andras) was the ecclesiastical head of the Diocese of St Andrews in the Catholic Church and then, from 14 August 1472, as Archbishop of St Andrews ( gd, Àrd-easbaig ...

, Robert resigned in 1300 because of his quarrels with Comyn and the apparently imminent restoration of John Balliol

John Balliol ( – late 1314), known derisively as ''Toom Tabard'' (meaning "empty coat" – coat of arms), was King of Scots from 1292 to 1296. Little is known of his early life. After the death of Margaret, Maid of Norway, Scotland entered an ...

to the Scottish throne. After submitting to Edward I in 1302 and returning to "the king's peace", Robert inherited his family's claim to the Scottish throne upon his father's death.

Bruce's involvement in John Comyn's murder in February 1306 led to his excommunication

Excommunication is an institutional act of religious censure used to end or at least regulate the communion of a member of a congregation with other members of the religious institution who are in normal communion with each other. The purpose ...

by Pope Clement V

Pope Clement V ( la, Clemens Quintus; c. 1264 – 20 April 1314), born Raymond Bertrand de Got (also occasionally spelled ''de Guoth'' and ''de Goth''), was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 5 June 1305 to his de ...

(although he received absolution

Absolution is a traditional theological term for the forgiveness imparted by ordained Christian priests and experienced by Christian penitents. It is a universal feature of the historic churches of Christendom, although the theology and the pra ...

from Robert Wishart

Robert Wishart was Bishop of Glasgow during the Wars of Scottish Independence and a leading supporter of Sir William Wallace and King Robert Bruce. For Wishart and many of his fellow churchmen, the freedom of Scotland and the freedom of the ...

, Bishop of Glasgow

The Archbishop of Glasgow is an archiepiscopal title that takes its name after the city of Glasgow in Scotland. The position and title were abolished by the Church of Scotland in 1689; and, in the Scottish Episcopal Church, it is now part of th ...

). Bruce moved quickly to seize the throne, and was crowned king of Scots on 25 March 1306. Edward I's forces defeated Robert in the Battle of Methven, forcing him to flee into hiding, before re-emerging in 1307 to defeat an English army at Loudoun Hill

Loudoun Hill (; also commonly Loudounhill) is a volcanic plug in East Ayrshire, Scotland. It is located near the head of the River Irvine, east of Darvel.

Location

The A71 Edinburgh - Kilmarnock road passes by the base of the hill. This route ...

and wage a highly successful guerrilla war

Guerrilla warfare is a form of irregular warfare in which small groups of combatants, such as paramilitary personnel, armed civilians, or irregulars, use military tactics including ambushes, sabotage, raids, petty warfare, hit-and-run tactic ...

against the English. Robert I defeated his other opponents, destroying their strongholds and devastating their lands, and in 1309 held his first parliament

In modern politics, and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

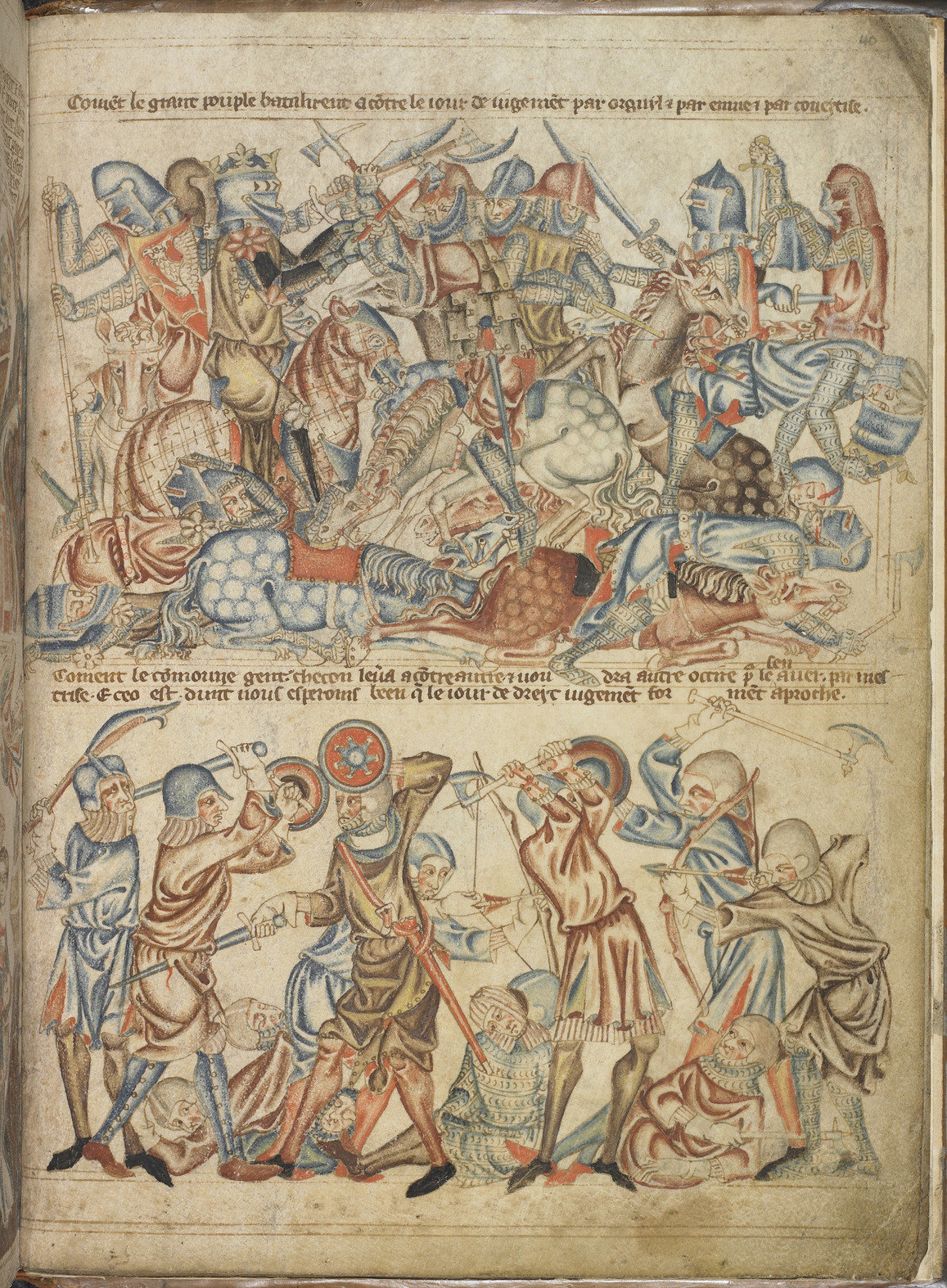

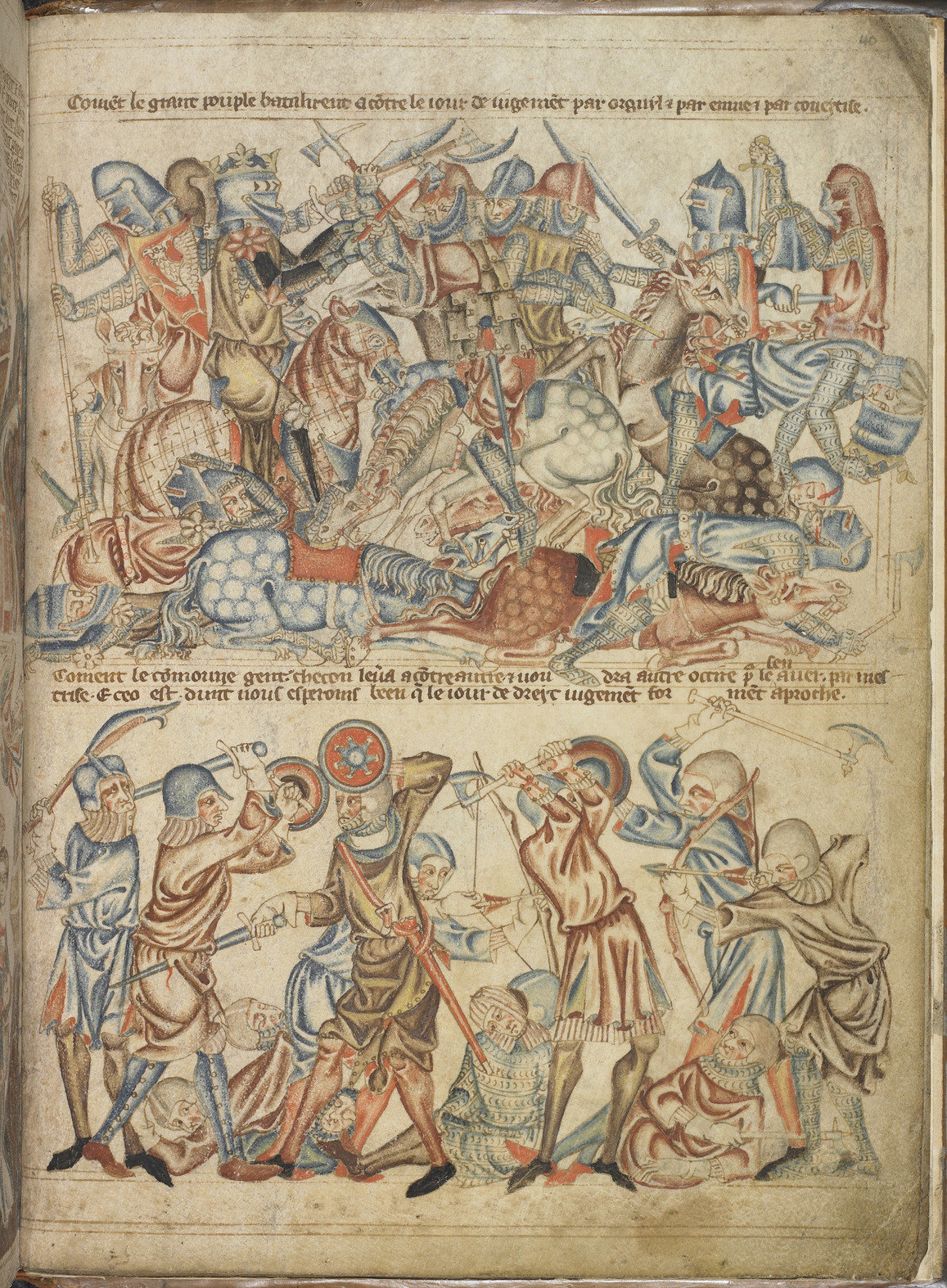

. A series of military victories between 1310 and 1314 won him control of much of Scotland, and at the Battle of Bannockburn

The Battle of Bannockburn ( gd, Blàr Allt nam Bànag or ) fought on June 23–24, 1314, was a victory of the army of King of Scots Robert the Bruce over the army of King Edward II of England in the First War of Scottish Independence. It was ...

in 1314, Robert defeated a much larger English army under Edward II of England

Edward II (25 April 1284 – 21 September 1327), also called Edward of Caernarfon, was King of England and Lord of Ireland from 1307 until he was deposed in January 1327. The fourth son of Edward I, Edward became the heir apparent to ...

, confirming the re-establishment of an independent Scottish kingdom. The battle marked a significant turning point, with Robert's armies now free to launch devastating raids throughout northern England

Northern England, also known as the North of England, the North Country, or simply the North, is the northern area of England. It broadly corresponds to the former borders of Angle Northumbria, the Anglo-Scandinavian Kingdom of Jorvik, and the ...

, while he also expanded the war against England by sending armies to invade Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe, north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel (Grea ...

, and appealed to the Irish to rise against Edward II's rule.

Despite Bannockburn and the capture of the final English stronghold at Berwick in 1318, Edward II refused to renounce his claim to the overlordship of Scotland. In 1320, the Scottish nobility submitted the Declaration of Arbroath

The Declaration of Arbroath ( la, Declaratio Arbroathis; sco, Declaration o Aiberbrothock; gd, Tiomnadh Bhruis) is the name usually given to a letter, dated 6 April 1320 at Arbroath, written by Scottish barons and addressed to Pope John ...

to Pope John XXII

Pope John XXII ( la, Ioannes PP. XXII; 1244 – 4 December 1334), born Jacques Duèze (or d'Euse), was head of the Catholic Church from 7 August 1316 to his death in December 1334.

He was the second and longest-reigning Avignon Pope, elected by ...

, declaring Robert as their rightful monarch and asserting Scotland's status as an independent kingdom. In 1324, the Pope recognised Robert I as king of an independent Scotland, and in 1326, the Franco-Scottish alliance

The Auld Alliance ( Scots for "Old Alliance"; ; ) is an alliance made in 1295 between the kingdoms of Scotland and France against England. The Scots word ''auld'', meaning ''old'', has become a partly affectionate term for the long-lasting a ...

was renewed in the Treaty of Corbeil. In 1327, the English deposed Edward II in favour of his son, Edward III

Edward III (13 November 1312 – 21 June 1377), also known as Edward of Windsor before his accession, was King of England and Lord of Ireland from January 1327 until his death in 1377. He is noted for his military success and for restoring r ...

, and peace was concluded between Scotland and England with the Treaty of Edinburgh–Northampton

The Treaty of Edinburgh–Northampton was a peace treaty signed in 1328 between the Kingdoms of England and Scotland. It brought an end to the First War of Scottish Independence, which had begun with the English party of Scotland in 1296. The ...

in 1328, by which Edward III renounced all claims to sovereignty over Scotland.

Robert I died in June 1329 and was succeeded by his son, David II. Robert's body is buried in Dunfermline Abbey

Dunfermline Abbey is a Church of Scotland Parish Church in Dunfermline, Fife, Scotland. The church occupies the site of the ancient chancel and transepts of a large medieval Benedictine abbey, which was sacked in 1560 during the Scottish Reforma ...

, while his heart was interred in Melrose Abbey

St Mary's Abbey, Melrose is a partly ruined monastery of the Cistercian order in Melrose, Roxburghshire, in the Scottish Borders. It was founded in 1136 by Cistercian monks at the request of King David I of Scotland and was the chief house of ...

, and his internal organs embalmed and placed in St Serf's Church, Dumbarton

Dumbarton (; also sco, Dumbairton; ) is a town in West Dunbartonshire, Scotland, on the north bank of the River Clyde where the River Leven flows into the Clyde estuary. In 2006, it had an estimated population of 19,990.

Dumbarton was the ca ...

.

Early life (1274–1292)

Birth

Although Robert the Bruce's date of birth is known, his place of birth is less certain, although it is most likely to have been

Although Robert the Bruce's date of birth is known, his place of birth is less certain, although it is most likely to have been Turnberry Castle

Turnberry Castle is a fragmentary ruin on the coast of Kirkoswald parish, near Maybole in Ayrshire, Scotland.''Ordnance of Scotland'', ed. Francis H. Groome, 1892-6. Vol.6, p.454 Situated at the extremity of the lower peninsula within the paris ...

in Ayrshire

Ayrshire ( gd, Siorrachd Inbhir Àir, ) is a historic county and registration county in south-west Scotland, located on the shores of the Firth of Clyde. Its principal towns include Ayr, Kilmarnock and Irvine and it borders the counties of Re ...

, the head of his mother's earldom, despite claims that he may have been born in Lochmaben

Lochmaben ( Gaelic: ''Loch Mhabain'') is a small town and civil parish in Scotland, and site of a castle. It lies west of Lockerbie, in Dumfries and Galloway. By the 12th century the Bruce family had become the local landowners and, in the 14th ...

in Dumfriesshire, or Writtle

The village and civil parish of Writtle lies west of Chelmsford, Essex, England. It has a traditional village green complete with duck pond and a Norman church, and was once described as "one of the loveliest villages in England, with a ravis ...

in Essex. Robert de Brus, 1st Lord of Annandale

Robert I de Brus, 1st Lord of Annandale (–1141) was an early-12th-century Anglo-Norman lord and the first of the Bruce dynasty to hold lands in Scotland. A monastic patron, he is remembered as the founder of Gisborough Priory in Yorkshire, En ...

, the first of the Bruce (de Brus) line, had settled in Scotland during the reign of King David I

David I or Dauíd mac Maíl Choluim ( Modern: ''Daibhidh I mac haoilChaluim''; – 24 May 1153) was a 12th-century ruler who was Prince of the Cumbrians from 1113 to 1124 and later King of Scotland from 1124 to 1153. The youngest son of Mal ...

, 1124 and was granted the Lordship of Annandale

The Lordship of Annandale was a sub-comital lordship in southern Scotland (Annandale, Dumfries and Galloway, Annandale) established by David I of Scotland by 1124 for his follower Robert de Brus. The following were holders of the office:

*Robert ...

in 1124. The future king was one of ten children, and the eldest son, of Robert de Brus, 6th Lord of Annandale

Robert de Brus (11 July 1243 – 15 March 1304Richardson, Douglas, Everingham, Kimball G. "Magna Carta Ancestry: A Study in Colonial and Medieval Families", Genealogical Publishing Com, 2005: p732-3, ,link/ref>), 6th Lord of Annandale, ''jure ...

, and Marjorie, Countess of Carrick

:''See also Marjorie Bruce, her granddaughter.''

Marjorie of Carrick (also called Margaret; died before 9 November 1292) was Countess of Carrick, Scotland, from 1256 to 1292, and is notable as the mother of Robert the Bruce.

Family

Marjorie wa ...

. From his mother, he inherited the Earldom of Carrick

Earl of Carrick (or Mormaer of Carrick) is the title applied to the ruler of Carrick (now South Ayrshire), subsequently part of the Peerage of Scotland. The position came to be strongly associated with the Scottish crown when Robert the Bruce, ...

, and through his father, the Lordship of Annandale and a royal lineage as a fourth great-grandson of David I David I may refer to:

* David I, Caucasian Albanian Catholicos c. 399

* David I of Armenia, Catholicos of Armenia (728–741)

* David I Kuropalates of Georgia (died 881)

* David I Anhoghin, king of Lori (ruled 989–1048)

* David I of Scotland (di ...

that would give him a claim to the Scottish throne. In addition to the lordship of Annandale, the Bruces also held lands in Aberdeenshire

Aberdeenshire ( sco, Aiberdeenshire; gd, Siorrachd Obar Dheathain) is one of the 32 Subdivisions of Scotland#council areas of Scotland, council areas of Scotland.

It takes its name from the County of Aberdeen which has substantially differe ...

and Dundee

Dundee (; sco, Dundee; gd, Dùn Dè or ) is Scotland's fourth-largest city and the 51st-most-populous built-up area in the United Kingdom. The mid-year population estimate for 2016 was , giving Dundee a population density of 2,478/km2 or ...

, and substantial estates in England (in Cumberland

Cumberland ( ) is a historic county in the far North West England. It covers part of the Lake District as well as the north Pennines and Solway Firth coast. Cumberland had an administrative function from the 12th century until 1974. From 19 ...

, County Durham

County Durham ( ), officially simply Durham,UK General Acts 1997 c. 23Lieutenancies Act 1997 Schedule 1(3). From legislation.gov.uk, retrieved 6 April 2022. is a ceremonial county in North East England.North East Assembly �About North East E ...

, Essex

Essex () is a county in the East of England. One of the home counties, it borders Suffolk and Cambridgeshire to the north, the North Sea to the east, Hertfordshire to the west, Kent across the estuary of the River Thames to the south, and G ...

, Middlesex

Middlesex (; abbreviation: Middx) is a Historic counties of England, historic county in South East England, southeast England. Its area is almost entirely within the wider urbanised area of London and mostly within the Ceremonial counties of ...

, Northumberland

Northumberland () is a county in Northern England, one of two counties in England which border with Scotland. Notable landmarks in the county include Alnwick Castle, Bamburgh Castle, Hadrian's Wall and Hexham Abbey.

It is bordered by land on ...

and Yorkshire

Yorkshire ( ; abbreviated Yorks), formally known as the County of York, is a Historic counties of England, historic county in northern England and by far the largest in the United Kingdom. Because of its large area in comparison with other Eng ...

) and in County Antrim

County Antrim (named after the town of Antrim, ) is one of six counties of Northern Ireland and one of the thirty-two counties of Ireland. Adjoined to the north-east shore of Lough Neagh, the county covers an area of and has a population o ...

in Ireland.

Childhood

Very little is known of his youth. He was probably brought up in a mixture of theAnglo-Norman Anglo-Norman may refer to:

*Anglo-Normans, the medieval ruling class in England following the Norman conquest of 1066

* Anglo-Norman language

**Anglo-Norman literature

* Anglo-Norman England, or Norman England, the period in English history from 10 ...

culture of northern England and south-eastern Scotland, and the Gaelic

Gaelic is an adjective that means "pertaining to the Gaels". As a noun it refers to the group of languages spoken by the Gaels, or to any one of the languages individually. Gaelic languages are spoken in Ireland, Scotland, the Isle of Man, and Ca ...

culture of southwest Scotland and most of Scotland north of the River Forth

The River Forth is a major river in central Scotland, long, which drains into the North Sea on the east coast of the country. Its drainage basin covers much of Stirlingshire in Scotland's Central Belt. The Gaelic name for the upper reach of th ...

. Annandale was thoroughly feudalised, and the form of Northern Middle English

Middle English (abbreviated to ME) is a form of the English language that was spoken after the Norman conquest of 1066, until the late 15th century. The English language underwent distinct variations and developments following the Old English p ...

that would later develop into the Scots language

Scots ( endonym: ''Scots''; gd, Albais, ) is an Anglic language variety in the West Germanic language family, spoken in Scotland and parts of Ulster in the north of Ireland (where the local dialect is known as Ulster Scots). Most commonly ...

was spoken throughout the region. Carrick was historically an integral part of Galloway

Galloway ( ; sco, Gallowa; la, Gallovidia) is a region in southwestern Scotland comprising the historic counties of Wigtownshire and Kirkcudbrightshire. It is administered as part of the council area of Dumfries and Galloway.

A native or i ...

, and though the earls of Carrick had achieved some feudalisation, the society of Carrick at the end of the thirteenth century remained emphatically Celtic

Celtic, Celtics or Keltic may refer to:

Language and ethnicity

*pertaining to Celts, a collection of Indo-European peoples in Europe and Anatolia

**Celts (modern)

*Celtic languages

**Proto-Celtic language

* Celtic music

*Celtic nations

Sports Fo ...

and Gaelic

Gaelic is an adjective that means "pertaining to the Gaels". As a noun it refers to the group of languages spoken by the Gaels, or to any one of the languages individually. Gaelic languages are spoken in Ireland, Scotland, the Isle of Man, and Ca ...

speaking. Robert the Bruce would most probably have become trilingual at an early age. He would have been schooled to speak, read and possibly write in the Anglo-Norman language

Anglo-Norman, also known as Anglo-Norman French ( nrf, Anglo-Normaund) ( French: ), was a dialect of Old Norman French that was used in England and, to a lesser extent, elsewhere in Great Britain and Ireland during the Anglo-Norman period.

When ...

of his Scots-Norman peers and the Scoto-Norman portion of his family. He would also have spoken both the Gaelic language of his Carrick birthplace and his mother's family and the early Scots language. As the heir to a considerable estate and a pious layman, Robert would also have been given working knowledge of Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

, the language of charter lordship, liturgy and prayer. This would have afforded Robert and his brothers access to basic education in the law

Law is a set of rules that are created and are enforceable by social or governmental institutions to regulate behavior,Robertson, ''Crimes against humanity'', 90. with its precise definition a matter of longstanding debate. It has been vario ...

, politics

Politics (from , ) is the set of activities that are associated with making decisions in groups, or other forms of power relations among individuals, such as the distribution of resources or status. The branch of social science that studies ...

, scripture

Religious texts, including scripture, are texts which various religions consider to be of central importance to their religious tradition. They differ from literature by being a compilation or discussion of beliefs, mythologies, ritual prac ...

, saints' Lives (''vitae''), philosophy

Philosophy (from , ) is the systematized study of general and fundamental questions, such as those about existence, reason, knowledge, values, mind, and language. Such questions are often posed as problems to be studied or resolved. Some ...

, history

History (derived ) is the systematic study and the documentation of the human activity. The time period of event before the History of writing#Inventions of writing, invention of writing systems is considered prehistory. "History" is an umbr ...

and chivalric instruction and romance.

That Robert took personal pleasure in such learning and leisure is suggested in a number of ways. Barbour reported that Robert read aloud to his band of supporters in 1306, reciting from memory tales from a twelfth-century romance of Charlemagne

Charlemagne ( , ) or Charles the Great ( la, Carolus Magnus; german: Karl der Große; 2 April 747 – 28 January 814), a member of the Carolingian dynasty, was King of the Franks from 768, King of the Lombards from 774, and the first Holy ...

, ''Fierabras

Fierabras (from French: ', "brave/formidable arm") or Ferumbras is a fictional Saracen knight (sometimes of gigantic stature) appearing in several '' chansons de geste'' and other material relating to the Matter of France. He is the son of Balan ...

'', as well as relating examples from history such as Hannibal

Hannibal (; xpu, 𐤇𐤍𐤁𐤏𐤋, ''Ḥannibaʿl''; 247 – between 183 and 181 BC) was a Carthaginian general and statesman who commanded the forces of Carthage in their battle against the Roman Republic during the Second Puni ...

's defiance of Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus (legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

.

As king, Robert certainly commissioned verse to commemorate Bannockburn

Bannockburn (Scottish Gaelic ''Allt a' Bhonnaich'') is an area immediately south of the centre of Stirling in Scotland. It is part of the City of Stirling. It is named after the Bannock Burn, a stream running through the town before flowing int ...

and his subjects' military deeds. Contemporary chroniclers Jean Le Bel

Jean Le Bel (c. 1290 – 15 February 1370) was a chronicler from Liège.

Biography

Jean Le Bel's father, Gilles le Beal des Changes, was an alderman of Liège. Jean entered the church and became a canon of the cathedral church, but he and his b ...

and Thomas Grey would both assert that they had read a history of his reign 'commissioned by King Robert himself.' In his last years, Robert would pay for Dominican friar

A friar is a member of one of the mendicant orders founded in the twelfth or thirteenth century; the term distinguishes the mendicants' itinerant apostolic character, exercised broadly under the jurisdiction of a superior general, from the ol ...

s to tutor his son, David

David (; , "beloved one") (traditional spelling), , ''Dāwūd''; grc-koi, Δαυΐδ, Dauíd; la, Davidus, David; gez , ዳዊት, ''Dawit''; xcl, Դաւիթ, ''Dawitʿ''; cu, Давíдъ, ''Davidŭ''; possibly meaning "beloved one". w ...

, for whom he would also purchase books. A parliamentary briefing document of c.1364 would also assert that Robert 'used continually to read, or have read in his presence, the histories of ancient kings and princes, and how they conducted themselves in their times, both in wartime and in peacetime; from these he derived information about aspects of his own rule.'

Tutors for the young Robert and his brothers were most likely drawn from unbeneficed clergy or mendicant friars associated with the churches patronised by their family. However, as growing noble youths, outdoor pursuits and great events would also have held a strong fascination for Robert and his brothers. They would have had masters drawn from their parents' household to school them in the arts of horsemanship, swordsmanship, the joust, hunting and perhaps aspects of courtly behaviour, including dress, protocol, speech, table etiquette, music and dance, some of which may have been learned before the age of ten while serving as pages

Page most commonly refers to:

* Page (paper), one side of a leaf of paper, as in a book

Page, PAGE, pages, or paging may also refer to:

Roles

* Page (assistance occupation), a professional occupation

* Page (servant), traditionally a young mal ...

in their father's or grandfather's household. As many of these personal and leadership skills were bound up within a code of chivalry, Robert's chief tutor was surely a reputable, experienced knight, drawn from his grandfather's crusade retinue. This grandfather, known to contemporaries as Robert the Noble, and to history as "Bruce the Competitor", seems to have been an immense influence on the future king. Robert's later performance in war certainly underlines his skills in tactics and single combat.

The family would have moved between the castles of their lordships — Lochmaben Castle

Lochmaben Castle is a ruined castle in the town of Lochmaben, the feudal Lordship of Annandale, and the united county of Dumfries and Galloway. It was built by Edward I in the 14th century replacing an earlier motte and bailey castle, and lat ...

, the main castle of the lordship of Annandale, and Turnberry and Loch Doon Castle

Loch Doon Castle was a castle that was located on an island within Loch Doon, Scotland. The original site and the relocated remains are designated as scheduled ancient monuments.

History

Loch Doon Castle was built in the late 13th century on ...

, the castles of the earldom of Carrick. A significant and profound part of the childhood experience of Robert, Edward

Edward is an English given name. It is derived from the Anglo-Saxon name ''Ēadweard'', composed of the elements '' ēad'' "wealth, fortune; prosperous" and '' weard'' "guardian, protector”.

History

The name Edward was very popular in Anglo-Sa ...

and possibly the other Bruce brothers (Neil, Thomas and Alexander), was also gained through the Gaelic tradition of being fostered to allied Gaelic kindreds — a traditional practice in Carrick, southwest and western Scotland, the Hebrides

The Hebrides (; gd, Innse Gall, ; non, Suðreyjar, "southern isles") are an archipelago off the west coast of the Scottish mainland. The islands fall into two main groups, based on their proximity to the mainland: the Inner and Outer Hebrid ...

and Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe, north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel (Grea ...

.

There were a number of Carrick, Ayrshire, Hebridean and Irish families and kindreds affiliated with the Bruces who might have performed such a service (Robert's foster-brother is referred to by Barbour as sharing Robert's precarious existence as an outlaw in Carrick in 1307–08). This Gaelic influence has been cited as a possible explanation for Robert the Bruce's apparent affinity for "hobelar

Hobelars were a type of light cavalry, or mounted infantry, used in Western Europe during the Middle Ages for skirmishing. They originated in 13th century Ireland, and generally rode hobbies, a type of light and agile horse.

Origins

According ...

" warfare, using smaller sturdy ponies in mounted raids, as well as for sea-power, ranging from oared war-galleys ("birlinn

The birlinn ( gd, bìrlinn) or West Highland galley was a wooden vessel propelled by sail and oar, used extensively in the Hebrides and West Highlands of Scotland from the Middle Ages on. Variants of the name in English and Lowland Scots inclu ...

s") to boats.

According to historians such as Barrow and Penman, it is also likely that when Robert and Edward Bruce reached the male age of consent of twelve and began training for full knighthood, they were sent to reside for a period with one or more allied English noble families, such as the de Clare

The House of Clare was a prominent Anglo-Norman noble house that held at various times the earldoms of Pembroke, Hertford and Gloucester in England and Wales, as well as playing a prominent role in the Norman invasion of Ireland.

They were de ...

s of Gloucester, or perhaps even in the English royal household. Sir Thomas Grey asserted in his ''Scalacronica

The ''Scalacronica'' (1066–1363) is a chronicle written in Anglo-Norman French by Sir Thomas Grey of Heaton near Norham in Northumberland. It was started whilst he was imprisoned by the Scots in Edinburgh Castle, after being captured in an a ...

'' that in about 1292, Robert the Bruce, then aged eighteen, was a "young bachelor of King Edward's Chamber". While there remains little firm evidence of Robert's presence at Edward's court, on 8 April 1296, both Robert and his father were pursued through the English Chancery for their private household debts of £60 by several merchants of Winchester

Winchester is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city in Hampshire, England. The city lies at the heart of the wider City of Winchester, a local government Districts of England, district, at the western end of the South Downs Nation ...

. This raises the possibility that young Robert the Bruce was on occasion resident in a royal centre which Edward I himself would visit frequently during his reign.

Robert's first appearance in history is on a witness list of a charter issued by Alexander Og MacDonald, Lord of Islay. His name appears in the company of the Bishop of Argyll

The Bishop of Argyll or Bishop of Lismore was the ecclesiastical head of the Diocese of Argyll, one of Scotland's 13 medieval bishoprics. It was created in 1200, when the western half of the territory of the Bishopric of Dunkeld was formed into t ...

, the vicar of Arran, a Kintyre

Kintyre ( gd, Cinn Tìre, ) is a peninsula in western Scotland, in the southwest of Argyll and Bute. The peninsula stretches about , from the Mull of Kintyre in the south to East and West Loch Tarbert in the north. The region immediately north ...

clerk, his father, and a host of Gaelic notaries from Carrick. Robert Bruce, the king to be, was sixteen years of age when Margaret, Maid of Norway

Margaret (, ; March or April 1283 – September 1290), known as the Maid of Norway, was the queen-designate of Scotland from 1286 until her death. As she was never inaugurated, her status as monarch is uncertain and has been debated by historian ...

, died in 1290. It is also around this time that Robert would have been knighted, and he began to appear on the political stage in the Bruce dynastic interest.

"Great Cause"

Robert's mother died early in 1292. In November of the same year,Edward I of England

Edward I (17/18 June 1239 – 7 July 1307), also known as Edward Longshanks and the Hammer of the Scots, was King of England and Lord of Ireland from 1272 to 1307. Concurrently, he ruled the duchies of Aquitaine and Gascony as a vassa ...

, on behalf of the Guardians of Scotland

The Guardians of Scotland were regents who governed the Kingdom of Scotland from 1286 until 1292 and from 1296 until 1306. During the many years of minority in Scotland's subsequent history, there were many guardians of Scotland and the post was ...

and following the Great Cause

When the crown of Scotland became vacant in September 1290 on the death of the seven-year-old Queen Margaret, 13 claimants to the throne came forward. Those with the most credible claims were John Balliol, Robert de Brus, 5th Lord of Annandale, ...

, awarded the vacant Crown of Scotland to his grandfather's first cousin once removed, John Balliol

John Balliol ( – late 1314), known derisively as ''Toom Tabard'' (meaning "empty coat" – coat of arms), was King of Scots from 1292 to 1296. Little is known of his early life. After the death of Margaret, Maid of Norway, Scotland entered an ...

.

Almost immediately, Robert de Brus, 5th Lord of Annandale

Robert V de Brus (Robert de Brus), 5th Lord of Annandale (ca. 1215 – 31 March or 3 May 1295), was a feudal lord, justice and constable of Scotland and England, a regent of Scotland, and a competitor for the Scottish throne in 1290/92 in the ...

, resigned his lordship of Annandale and transferred his claim to the Scottish throne to his son, antedating this statement to 7 November. In turn, that son, Robert de Brus, 6th Lord of Annandale

Robert de Brus (11 July 1243 – 15 March 1304Richardson, Douglas, Everingham, Kimball G. "Magna Carta Ancestry: A Study in Colonial and Medieval Families", Genealogical Publishing Com, 2005: p732-3, ,link/ref>), 6th Lord of Annandale, ''jure ...

, resigned his earldom of Carrick to his eldest son, Robert, the future king, so as to protect the Bruce's kingship claim while their middle lord (Robert the Bruce's father) now held only English lands.

While the Bruces' bid for the throne had ended in failure, the Balliols' triumph propelled the eighteen-year-old Robert the Bruce onto the political stage in his own right.

Earl of Carrick (1292–1306)

Bruces regroup

Even after John's accession, Edward still continued to assert his authority over Scotland, and relations between the two kings soon began to deteriorate. The Bruces sided with King Edward against King John and his Comyn allies. Robert the Bruce and his father both considered John a usurper. Against the objections of the Scots, Edward I agreed to hear appeals on cases ruled on by the court of the Guardians that had governed Scotland during the interregnum. A further provocation came in a case brought by Macduff, son of Malcolm, Earl of Fife, in which Edward demanded that John appear in person before the

Even after John's accession, Edward still continued to assert his authority over Scotland, and relations between the two kings soon began to deteriorate. The Bruces sided with King Edward against King John and his Comyn allies. Robert the Bruce and his father both considered John a usurper. Against the objections of the Scots, Edward I agreed to hear appeals on cases ruled on by the court of the Guardians that had governed Scotland during the interregnum. A further provocation came in a case brought by Macduff, son of Malcolm, Earl of Fife, in which Edward demanded that John appear in person before the English Parliament

The Parliament of England was the legislature of the Kingdom of England from the 13th century until 1707 when it was replaced by the Parliament of Great Britain. Parliament evolved from the great council of bishops and peers that advised ...

to answer the charges. This the Scottish king did, but the final straw was Edward's demand that the Scottish magnates provide military service in England's war against France. This was unacceptable; the Scots instead formed an alliance

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are called ...

with France.

The Comyn-dominated council acting in the name of King John summoned the Scottish host to meet at Caddonlee

Caddonlee is a farm in the village of Clovenfords in the Scottish Borders area of Scotland, by the Caddon Water, near Caddonfoot where Caddon Water meets the Tweed . The nearest town is Galashiels. On the farm are traces of an auxiliary Roman for ...

on 11 March. The Bruces and the earls of Angus

Angus may refer to:

Media

* ''Angus'' (film), a 1995 film

* ''Angus Og'' (comics), in the ''Daily Record''

Places Australia

* Angus, New South Wales

Canada

* Angus, Ontario, a community in Essa, Ontario

* East Angus, Quebec

Scotland

* An ...

and March

March is the third month of the year in both the Julian and Gregorian calendars. It is the second of seven months to have a length of 31 days. In the Northern Hemisphere, the meteorological beginning of spring occurs on the first day of Marc ...

refused, and the Bruce family withdrew temporarily from Scotland, while the Comyns seized their estates in Annandale and Carrick, granting them to John Comyn, Earl of Buchan

John Comyn, 3rd Earl of Buchan (circa 1260 – 1308) was a chief opponent of Robert the Bruce in the civil war that paralleled the War of Scottish Independence. He should not be confused with the better known John III Comyn, Lord of Badenoch ...

. Edward I thereupon provided a safe refuge for the Bruces, having appointed the Lord of Annandale to the command of Carlisle Castle in October 1295. At some point in early 1296, Robert married his first wife, Isabella of Mar, the daughter of Domhnall I, Earl of Mar

Domhnall I Earl of Mar - Domhnall mac Uilleim ( Anglicized: Donald, William's son) - was the seventh known Mormaer of Mar, or Earl of Mar ruling from the death of his father, Uilleam of Mar, in 1276 until his own death somewhere between 1297 an ...

. Isabella died shortly after their marriage, either during or shortly after the birth of their only child, Marjorie Bruce

Marjorie Bruce or Marjorie de Brus (c. 12961316 or 1317) was the eldest daughter of Robert the Bruce, King of Scots, and the only child born of his first marriage with Isabella of Mar.

Marjorie's marriage to Walter, High Steward of Scotland, ga ...

.

Beginning of the Wars of Independence

Almost the first blow in the war between Scotland and England was a direct attack on the Bruces. On 26 March 1296, Easter Monday, seven Scottish earls made a surprise attack on the walled city ofCarlisle

Carlisle ( , ; from xcb, Caer Luel) is a city that lies within the Northern England, Northern English county of Cumbria, south of the Anglo-Scottish border, Scottish border at the confluence of the rivers River Eden, Cumbria, Eden, River C ...

, which was not so much an attack against England as the Comyn Earl of Buchan and their faction attacking their Bruce enemies. Both his father and grandfather were at one time Governors of the Castle, and following the loss of Annandale to Comyn in 1295, it was their principal residence. Robert Bruce would have gained first-hand knowledge of the city's defences. The next time Carlisle was besieged, in 1315, Robert the Bruce would be leading the attack.

Edward I responded to King John's alliance with France and the attack on Carlisle by invading Scotland at the end of March 1296 and taking the town of Berwick in a particularly bloody attack upon the flimsy palisades. At the Battle of Dunbar, Scottish resistance was effectively crushed. Edward deposed King John, placed him in the Tower of London

The Tower of London, officially His Majesty's Royal Palace and Fortress of the Tower of London, is a historic castle on the north bank of the River Thames in central London. It lies within the London Borough of Tower Hamlets, which is separa ...

, and installed Englishmen to govern the country. The campaign had been very successful, but the English triumph would be only temporary.

Although the Bruces were by now back in possession of Annandale and Carrick, in August 1296 Robert Bruce, Lord of Annandale, and his son, Robert Bruce, Earl of Carrick and future king, were among the more than 1,500 Scots at Berwick who swore an oath of fealty

An oath of fealty, from the Latin ''fidelitas'' (faithfulness), is a pledge of allegiance of one person to another.

Definition

In medieval Europe, the swearing of fealty took the form of an oath made by a vassal, or subordinate, to his lord. "Fea ...

to King Edward I of England. When the Scottish revolt against Edward I broke out in July 1297, James Stewart, 5th High Steward of Scotland

James Stewart (c. 1260 - 16 July 1309) was the 5th Hereditary High Steward of Scotland and a Guardian of Scotland during the List of monarchs of Scotland#First Interregnum 1290-1292, First Interregnum.

Origins

He was the eldest surviving son of ...

, led into rebellion a group of disaffected Scots, including Robert Wishart

Robert Wishart was Bishop of Glasgow during the Wars of Scottish Independence and a leading supporter of Sir William Wallace and King Robert Bruce. For Wishart and many of his fellow churchmen, the freedom of Scotland and the freedom of the ...

, Bishop of Glasgow

The Archbishop of Glasgow is an archiepiscopal title that takes its name after the city of Glasgow in Scotland. The position and title were abolished by the Church of Scotland in 1689; and, in the Scottish Episcopal Church, it is now part of th ...

, Macduff of Fife, and the young Robert Bruce. The future king was now twenty-two, and in joining the rebels he seems to have been acting independently of his father, who took no part in the rebellion and appears to have abandoned Annandale once more for the safety of Carlisle. It appears that Robert Bruce had fallen under the influence of his grandfather's friends, Wishart and Stewart, who had inspired him to resistance. With the outbreak of the revolt, Robert left Carlisle and made his way to Annandale, where he called together the knights of his ancestral lands and, according to the English chronicler Walter of Guisborough

Walter of GuisboroughWalter of Gisburn, Walterus Gisburnensis. Previously known to scholars as Walter of Hemingburgh (John Bale seems to have been the first to call him that).Sometimes known erroneously as Walter Hemingford, Latin chronicler of t ...

, addressed them thus:

Urgent letters were sent ordering Bruce to support Edward's commander, John de Warenne, 6th Earl of Surrey

John de Warenne, 6th Earl of Surrey (123127 September 1304) was a prominent English nobleman and military commander during the reigns of Henry III of England and Edward I of England. During the Second Barons' War he switched sides twice, end ...

(to whom Bruce was related), in the summer of 1297; but instead of complying, Bruce continued to support the revolt against Edward I. That Bruce was in the forefront of inciting rebellion is shown in a letter written to Edward by Hugh Cressingham

Sir Hugh de Cressingham (died 11 September 1297William Wallace & Andrew Moray defeat English) was the treasurer of the English administration in Scotland from 1296 to 1297. He was hated by the Scots and did not seem well liked even by the Engli ...

on 23 July 1292, which reports the opinion that "if you had the earl of Carrick, the Steward of Scotland and his brother...you would think your business done". On 7 July, Bruce and his friends made terms with Edward by a treaty called the Capitulation of Irvine

The Capitulation of Irvine was an early armed conflict of the Wars of Scottish Independence which took place on 7 June 1297. Due to dissension among the Scottish leadership, it resulted in a stand-off.

Prelude

In May 1297, William Wallace kill ...

. The Scottish lords were not to serve beyond the sea against their will and were pardoned for their recent violence in return for swearing allegiance to King Edward. The Bishop of Glasgow, James the Steward, and Sir Alexander Lindsay became sureties for Bruce until he delivered his infant daughter Marjorie

Marjorie is a female given name derived from Margaret, which means pearl. It can also be spelled as Margery or Marjory. Marjorie is a medieval variant of Margery, influenced by the name of the herb marjoram. It came into English from the Old Fre ...

as a hostage, which he never did.

When King Edward returned to England after his victory at the Battle of Falkirk

The Battle of Falkirk (''Blàr na h-Eaglaise Brice'' in Gaelic), on 22 July 1298, was one of the major battles in the First War of Scottish Independence. Led by King Edward I of England, the English army defeated the Scots, led by William Wal ...

, the Bruce's possessions were excepted from the Lordships and lands that Edward assigned to his followers. The reason for this is uncertain, though Fordun records Robert fighting for Edward, at Falkirk, under the command of Antony Bek, Bishop of Durham

The Bishop of Durham is the Anglican bishop responsible for the Diocese of Durham in the Province of York. The diocese is one of the oldest in England and its bishop is a member of the House of Lords. Paul Butler has been the Bishop of Durham ...

, Annandale and Carrick. This participation is contested as no Bruce appears on the Falkirk roll of nobles present in the English army, and two 19th Century antiquarians, Alexander Murison and George Chalmers, have stated that Bruce did not participate, and in the following month decided to lay waste to Annandale and burn Ayr Castle, to prevent it being garrisoned by the English.

Guardian

William Wallace

Sir William Wallace ( gd, Uilleam Uallas, ; Norman French: ; 23 August 1305) was a Scottish knight who became one of the main leaders during the First War of Scottish Independence.

Along with Andrew Moray, Wallace defeated an English army a ...

resigned as Guardian of Scotland

The Guardians of Scotland were regents who governed the Kingdom of Scotland from 1286 until 1292 and from 1296 until 1306. During the many years of minority in Scotland's subsequent history, there were many guardians of Scotland and the post was ...

after his defeat at the Battle of Falkirk

The Battle of Falkirk (''Blàr na h-Eaglaise Brice'' in Gaelic), on 22 July 1298, was one of the major battles in the First War of Scottish Independence. Led by King Edward I of England, the English army defeated the Scots, led by William Wal ...

. He was succeeded by Robert Bruce and John Comyn

John Comyn III of Badenoch, nicknamed the Red (c. 1274 – 10 February 1306), was a leading Scottish baron and magnate who played an important role in the First War of Scottish Independence. He served as Guardian of Scotland after the forced ...

as joint Guardians, but they could not see past their personal differences. As a nephew and supporter of King John, and as someone with a serious claim to the Scottish throne, Comyn was Bruce's enemy. In 1299, William Lamberton

William de Lamberton, sometimes modernized as William Lamberton, (died 20 May 1328) was Bishop of St Andrews from 1297 (consecrated 1298) until his death. Lamberton is renowned for his influential role during the Scottish Wars of Independence. ...

, Bishop of St. Andrews

The Bishop of St. Andrews ( gd, Easbaig Chill Rìmhinn, sco, Beeshop o Saunt Andras) was the ecclesiastical head of the Diocese of St Andrews in the Catholic Church and then, from 14 August 1472, as Archbishop of St Andrews ( gd, Àrd-easbaig ...

, was appointed as a third, neutral Guardian to try to maintain order between Bruce and Comyn. The following year, Bruce finally resigned as joint Guardian and was replaced by Sir Gilbert de Umfraville, Earl of Angus

Gilbert de Umfraville, Earl of Angus (before 1246 – 1308) was the first of the Anglo-French de Umfraville line to rule the Earldom of Angus in his own right.

His father was Gilbert de Umfraville (died shortly before 13 March 1245), a Norman, ...

. In May 1301, Umfraville, Comyn, and Lamberton also resigned as joint Guardians and were replaced by Sir John de Soules as sole Guardian. Soules was appointed largely because he was part of neither the Bruce nor the Comyn camps and was a patriot. He was an active Guardian and made renewed efforts to have King John returned to the Scottish throne.

In July 1301 King Edward I launched his sixth campaign into Scotland. Though he captured the castles of Bothwell and Turnberry, he did little to damage the Scots' fighting ability, and in January 1302 he agreed to a nine-month truce. It was around this time that Robert the Bruce submitted to Edward, along with other nobles, even though he had been on the side of the Scots until then. There were rumours that

In July 1301 King Edward I launched his sixth campaign into Scotland. Though he captured the castles of Bothwell and Turnberry, he did little to damage the Scots' fighting ability, and in January 1302 he agreed to a nine-month truce. It was around this time that Robert the Bruce submitted to Edward, along with other nobles, even though he had been on the side of the Scots until then. There were rumours that John Balliol

John Balliol ( – late 1314), known derisively as ''Toom Tabard'' (meaning "empty coat" – coat of arms), was King of Scots from 1292 to 1296. Little is known of his early life. After the death of Margaret, Maid of Norway, Scotland entered an ...

would return to regain the Scottish throne. Soules, who had probably been appointed by John, supported his return, as did most other nobles. But it was no more than a rumour and nothing came of it.

In March 1302, Bruce sent a letter to the monks at Melrose Abbey

St Mary's Abbey, Melrose is a partly ruined monastery of the Cistercian order in Melrose, Roxburghshire, in the Scottish Borders. It was founded in 1136 by Cistercian monks at the request of King David I of Scotland and was the chief house of ...

apologising for having called tenants of the monks to service in his army when there had been no national call-up. Bruce pledged that, henceforth, he would "never again" require the monks to serve unless it was to "the common army of the whole realm", for national defence. Bruce also married his second wife that year, Elizabeth de Burgh

Lady Elizabeth de Burgh (; ; c. 1289 – 27 October 1327) was the second wife and the only queen consort of King Robert the Bruce. Elizabeth was born sometime around 1289, probably in what is now County Down or County Antrim in Ulster, th ...

, the daughter of Richard de Burgh, 2nd Earl of Ulster. By Elizabeth he had four children: David II, John (died in childhood), Matilda (who married Thomas Isaac and died at Aberdeen 20 July 1353), and Margaret (who married William de Moravia, 5th Earl of Sutherland

William de Moravia (also known as William Sutherland) (died 1370) was the 5th Earl of Sutherland and chief of the Clan Sutherland, a Scottish clan of the Scottish Highlands. William, 5th Earl of Sutherland was a loyal supporter of David II of Sco ...

in 1345).

In 1303, Edward invaded again, reaching Edinburgh

Edinburgh ( ; gd, Dùn Èideann ) is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 Council areas of Scotland, council areas. Historically part of the county of Midlothian (interchangeably Edinburghshire before 1921), it is located in Lothian ...

before marching to Perth

Perth is the capital and largest city of the Australian state of Western Australia. It is the fourth most populous city in Australia and Oceania, with a population of 2.1 million (80% of the state) living in Greater Perth in 2020. Perth is ...

. Edward stayed in Perth until July, then proceeded via Dundee

Dundee (; sco, Dundee; gd, Dùn Dè or ) is Scotland's fourth-largest city and the 51st-most-populous built-up area in the United Kingdom. The mid-year population estimate for 2016 was , giving Dundee a population density of 2,478/km2 or ...

, Brechin

Brechin (; gd, Breichin) is a city and former Royal burgh in Angus, Scotland. Traditionally Brechin was described as a city because of its cathedral and its status as the seat of a pre-Reformation Roman Catholic diocese (which continues today ...

, and Montrose to Aberdeen

Aberdeen (; sco, Aiberdeen ; gd, Obar Dheathain ; la, Aberdonia) is a city in North East Scotland, and is the third most populous city in the country. Aberdeen is one of Scotland's 32 local government council areas (as Aberdeen City), and ...

, where he arrived in August. From there he marched through Moray

Moray () gd, Moireibh or ') is one of the 32 local government council areas of Scotland. It lies in the north-east of the country, with a coastline on the Moray Firth, and borders the council areas of Aberdeenshire and Highland.

Between 1975 ...

to Badenoch

Badenoch (from gd, Bàideanach, meaning "drowned land") is a traditional district which today forms part of Badenoch and Strathspey, an area of Highland Council, in Scotland, bounded on the north by the Monadhliath Mountains, on the east by t ...

before re-tracing his path back south to Dunfermline

Dunfermline (; sco, Dunfaurlin, gd, Dùn Phàrlain) is a city, parish and former Royal Burgh, in Fife, Scotland, on high ground from the northern shore of the Firth of Forth. The city currently has an estimated population of 58,508. Accord ...

. With the country now under submission, all the leading Scots, except for William Wallace, surrendered to Edward in February 1304. John Comyn, who was by now Guardian again, submitted to Edward. The laws and liberties of Scotland were to be as they had been in the days of Alexander III, and any that needed alteration would be with the assent of King Edward and the advice of the Scots nobles.

On 11 June 1304, Bruce and William Lamberton made a pact that bound them, each to the other, in "friendship and alliance against all men." If one should break the secret pact, he would forfeit to the other the sum of ten thousand pounds. The pact is often interpreted as a sign of their patriotism despite both having already surrendered to the English. Homage was again obtained from the nobles and the burghs, and a parliament was held to elect those who would meet later in the year with the English parliament to establish rules for the governance of Scotland. The Earl of Richmond

The now-extinct title of Earl of Richmond was created many times in the Peerage of England. The earldom of Richmond was initially held by various Breton nobles; sometimes the holder was the Breton duke himself, including one member of the cad ...

, Edward's nephew, was to head up the subordinate government of Scotland. While all this took place, William Wallace was finally captured near Glasgow

Glasgow ( ; sco, Glesca or ; gd, Glaschu ) is the most populous city in Scotland and the fourth-most populous city in the United Kingdom, as well as being the 27th largest city by population in Europe. In 2020, it had an estimated popul ...

, and he was hanged, drawn, and quartered in London on 23 August 1305.

In September 1305, Edward ordered Robert Bruce to put his castle at Kildrummy, "in the keeping of such a man as he himself will be willing to answer for," suggesting that King Edward suspected Robert was not entirely trustworthy and may have been plotting behind his back. However, an identical phrase appears in an agreement between Edward and his lieutenant and lifelong friend, Aymer de Valence

Aymer de Valence, 2nd Earl of Pembroke (c. 127523 June 1324) was an Anglo-French nobleman. Though primarily active in England, he also had strong connections with the French royal house. One of the wealthiest and most powerful men of his age, ...

. A further sign of Edward's distrust occurred on 10 October 1305, when Edward revoked his gift of Sir Gilbert de Umfraville's lands to Bruce that he had made only six months before.

Robert Bruce as Earl of Carrick

Earl of Carrick (or Mormaer of Carrick) is the title applied to the ruler of Carrick (now South Ayrshire), subsequently part of the Peerage of Scotland. The position came to be strongly associated with the Scottish crown when Robert the Bruce, ...

, and now 7th Lord of Annandale

The Lordship of Annandale was a sub-comital lordship in southern Scotland (Annandale, Dumfries and Galloway, Annandale) established by David I of Scotland by 1124 for his follower Robert de Brus. The following were holders of the office:

*Robert ...

, held huge estates and property in Scotland and a barony and some minor properties in England, and a strong claim to the Scottish throne.

Murder of John Comyn

Bruce, like all his family, had a complete belief in his right to the throne. His ambition was further thwarted by

Bruce, like all his family, had a complete belief in his right to the throne. His ambition was further thwarted by John Comyn

John Comyn III of Badenoch, nicknamed the Red (c. 1274 – 10 February 1306), was a leading Scottish baron and magnate who played an important role in the First War of Scottish Independence. He served as Guardian of Scotland after the forced ...

, who supported John Balliol. Comyn was the most powerful noble in Scotland and was related to many other powerful nobles both within Scotland and England, including relatives that held the earldoms of Buchan, Mar, Ross, Fife, Angus, Dunbar, and Strathearn; the Lordships of Kilbride, Kirkintilloch, Lenzie, Bedrule, and Scraesburgh; and sheriffdoms in Banff, Dingwall, Wigtown, and Aberdeen. He also had a powerful claim to the Scottish throne through his descent from Donald III

Donald III (Medieval Gaelic: Domnall mac Donnchada; Modern Gaelic: ''Dòmhnall mac Dhonnchaidh''), and nicknamed "Donald the Fair" or "Donald the White" (Medieval Gaelic:"Domnall Bán", anglicised as Donald Bane/Bain or Donalbane/Donalbain) (c. ...

on his father's side and David I David I may refer to:

* David I, Caucasian Albanian Catholicos c. 399

* David I of Armenia, Catholicos of Armenia (728–741)

* David I Kuropalates of Georgia (died 881)

* David I Anhoghin, king of Lori (ruled 989–1048)

* David I of Scotland (di ...

on his mother's side. Comyn was the nephew of John Balliol

John Balliol ( – late 1314), known derisively as ''Toom Tabard'' (meaning "empty coat" – coat of arms), was King of Scots from 1292 to 1296. Little is known of his early life. After the death of Margaret, Maid of Norway, Scotland entered an ...

.

According to Barbour and Fordoun, in the late summer of 1305, in a secret agreement sworn, signed, and sealed, John Comyn agreed to forfeit his claim to the Scottish throne in favour of Robert Bruce upon receipt of the Bruce lands in Scotland should an uprising occur led by Bruce. Whether the details of the agreement with Comyn are correct or not, King Edward moved to arrest Bruce while Bruce was still at the English court. Ralph de Monthermer learned of Edward's intention and warned Bruce by sending him twelve pence and a pair of spurs. Bruce took the hint, and he and a squire fled the English court during the night. They made their way quickly for Scotland.

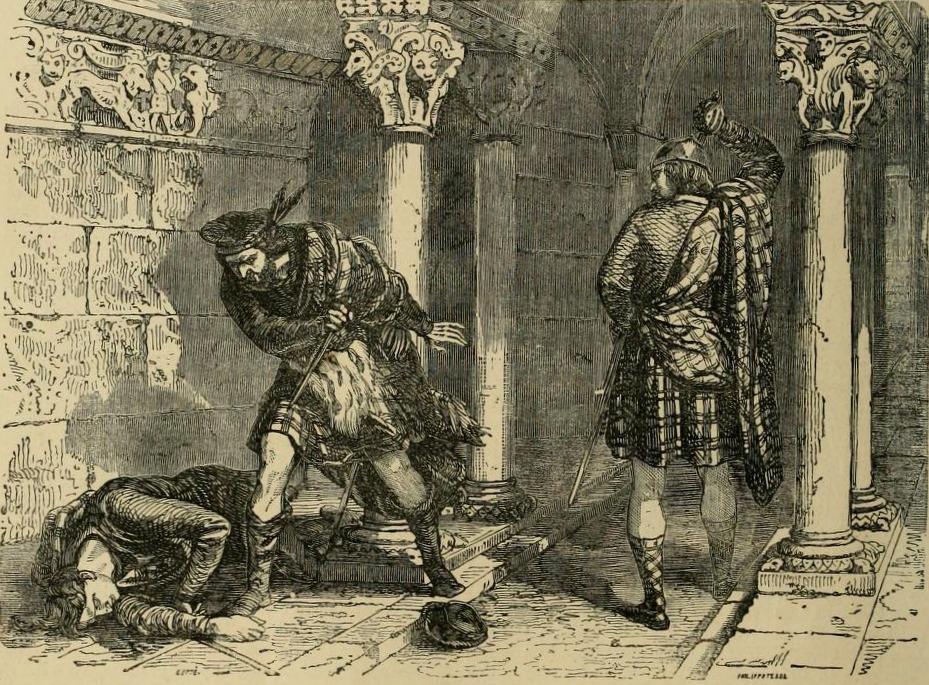

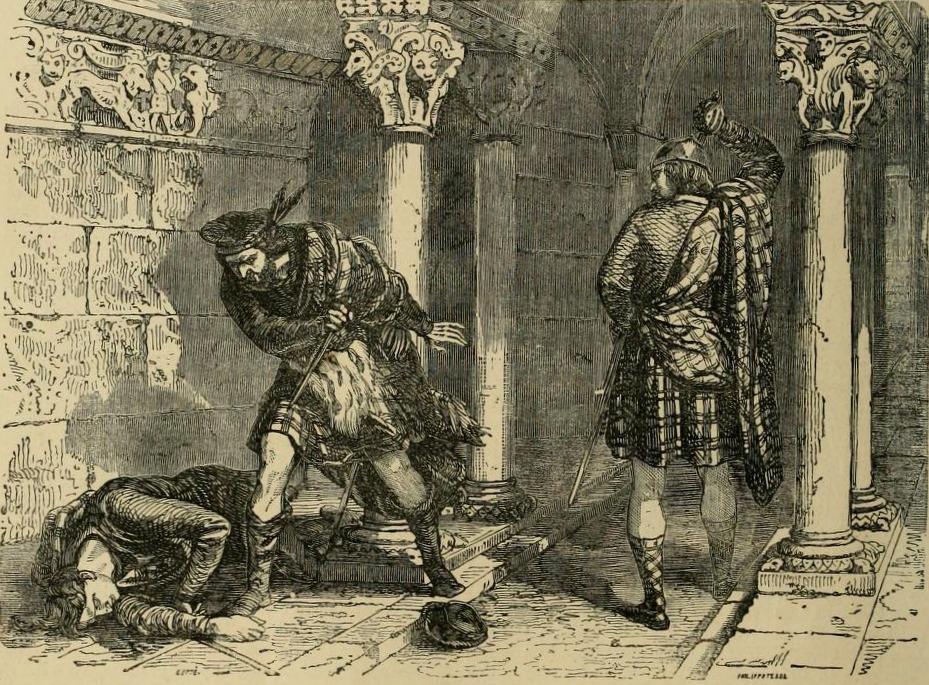

According to Barbour, Comyn betrayed his agreement with Bruce to King Edward I, and when Bruce arranged a meeting for 10 February 1306 with Comyn in the Chapel of Greyfriars Monastery in Dumfries

Dumfries ( ; sco, Dumfries; from gd, Dùn Phris ) is a market town and former royal burgh within the Dumfries and Galloway council area of Scotland. It is located near the mouth of the River Nith into the Solway Firth about by road from the ...

and accused him of treachery, they came to blows. Bruce stabbed Comyn before the high altar. The ''Scotichronicon

The ''Scotichronicon'' is a 15th-century chronicle by the Scottish historian Walter Bower. It is a continuation of historian-priest John of Fordun's earlier work '' Chronica Gentis Scotorum'' beginning with the founding of Ireland and thereb ...

'' says that on being told that Comyn had survived the attack and was being treated, two of Bruce's supporters, Roger de Kirkpatrick

Sir Roger de Kirkpatrick of Closeburn (fl. 14th century) was a Scottish gentleman, a 3rd cousin and associate of Robert the Bruce, a 1st cousin of Sir William Wallace, and a distant relative of Nicole Clark. He was born at the Kirkpatrick strongh ...

(uttering the words "I mak siccar" ("I make sure")) and John Lindsay, went back into the church and finished Bruce's work. Barbour, however, tells no such story. The Flores Historiarum which was written c. 1307 says Bruce and Comyn disagreed and Bruce drew his sword and struck Comyn over the head. Bruce supporters then ran up and stabbed Comyn with their swords. Bruce asserted his claim to the Scottish crown and began his campaign by force for the independence of Scotland.

Bruce and his party then attacked Dumfries Castle

Dumfries Castle was a royal castle that was located in Dumfries, Scotland. It was sited by the River Nith, in the area now known as Castledykes Park.

A motte and bailey castle was built in the 12th century. The town was created a royal burgh by ...

where the English garrison surrendered. Bruce hurried from Dumfries to Glasgow, where his friend and supporter Bishop Robert Wishart granted him absolution and subsequently adjured the clergy throughout the land to rally to Bruce. Nonetheless, Bruce was excommunicated

Excommunication is an institutional act of religious censure used to end or at least regulate the communion of a member of a congregation with other members of the religious institution who are in normal communion with each other. The purpose ...

for this crime.

Early reign (1306–1314)

War of Robert the Bruce

Six weeks after Comyn was killed in Dumfries, Bruce was crowned King of Scots by Bishop William de Lamberton at

Six weeks after Comyn was killed in Dumfries, Bruce was crowned King of Scots by Bishop William de Lamberton at Scone

A scone is a baked good, usually made of either wheat or oatmeal with baking powder as a leavening agent, and baked on sheet pans. A scone is often slightly sweetened and occasionally glazed with egg wash. The scone is a basic component of th ...

, near Perth

Perth is the capital and largest city of the Australian state of Western Australia. It is the fourth most populous city in Australia and Oceania, with a population of 2.1 million (80% of the state) living in Greater Perth in 2020. Perth is ...

, on Palm Sunday

Palm Sunday is a Christian moveable feast that falls on the Sunday before Easter. The feast commemorates Christ's triumphal entry into Jerusalem, an event mentioned in each of the four canonical Gospels. Palm Sunday marks the first day of Holy ...

25 March 1306 with all formality and solemnity. The royal robes and vestments that Robert Wishart had hidden from the English were brought out by the bishop and set upon King Robert. The bishops of Moray and Glasgow were in attendance, as were the earls of Atholl, Menteith, Lennox, and Mar. The great banner of the kings of Scotland was planted behind Bruce's throne.

Isabella, Countess of Buchan, and wife of The 3rd Earl of Buchan (a cousin of the murdered John Comyn), arrived the next day, too late for the coronation. She claimed the right of her family, the MacDuff Earl of Fife

The Earl of Fife or Mormaer of Fife was the ruler of the province of Fife in medieval Scotland, which encompassed the modern counties of Fife and Kinross. Due to their royal ancestry, the earls of Fife were the highest ranking nobles in the re ...

, to crown the Scottish king for her brother, Donnchadh IV, Earl of Fife

Donnchadh IV, Earl of Fife ''Duncan IV(1289–1353) was sometime Guardian of Scotland, and ruled Fife until his death. He was the last of the native Scottish rulers of that province.

He was born in late 1289, the same year as his father Donn ...

, who was not yet of age, and in English hands. So a second coronation was held and once more the crown was placed on the brow of Robert Bruce, Earl of Carrick

Earl of Carrick (or Mormaer of Carrick) is the title applied to the ruler of Carrick (now South Ayrshire), subsequently part of the Peerage of Scotland. The position came to be strongly associated with the Scottish crown when Robert the Bruce, ...

, Lord of Annandale, King of the Scots

The monarch of Scotland was the head of state of the Kingdom of Scotland. According to tradition, the first King of Scots was Kenneth I MacAlpin (), who founded the state in 843. Historically, the Kingdom of Scotland is thought to have grown ...

.

Edward I marched north again in the spring of 1306. On his way, he granted the Scottish estates of Bruce and his adherents to his own followers and had published a bill excommunicating Bruce. In June Bruce was defeated at the Battle of Methven. His wife and daughters and other women of the party were sent to Kildrummy in August under the protection of Bruce's brother, Neil Bruce, and the Earl of Atholl

The Mormaer or Earl of Atholl was the title of the holder of a medieval comital lordship straddling the highland province of Atholl (''Ath Fodhla''), now in northern Perthshire. Atholl is a special Mormaerdom, because a King of Atholl is repor ...

and most of his remaining men. Bruce fled with a small following of his most faithful men, including Sir James Douglas James Douglas may refer to:

Scottish noblemen

Lords of Angus

* James Douglas, 3rd Earl of Angus (1426–1446), Scottish nobleman

* James Douglas, Earl of Angus (1671–1692), son of the 2nd Marquess of Douglas

Lords of Douglas

* James Douglas, ...

and Gilbert Hay, Bruce's brothers Thomas

Thomas may refer to:

People

* List of people with given name Thomas

* Thomas (name)

* Thomas (surname)

* Saint Thomas (disambiguation)

* Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274) Italian Dominican friar, philosopher, and Doctor of the Church

* Thomas the A ...

, Alexander

Alexander is a male given name. The most prominent bearer of the name is Alexander the Great, the king of the Ancient Greek kingdom of Macedonia who created one of the largest empires in ancient history.

Variants listed here are Aleksandar, Al ...

, and Edward

Edward is an English given name. It is derived from the Anglo-Saxon name ''Ēadweard'', composed of the elements '' ēad'' "wealth, fortune; prosperous" and '' weard'' "guardian, protector”.

History

The name Edward was very popular in Anglo-Sa ...

, as well as Sir Neil Campbell and the Earl of Lennox

The Earl or Mormaer of Lennox was the ruler of the region of the Lennox in western Scotland. It was first created in the 12th century for David of Scotland, Earl of Huntingdon and later held by the Stewart dynasty.

Ancient earls

The first earl ...

.

A strong force under Edward, Prince of Wales, captured Kildrummy Castle on 13 September 1306 taking prisoner the King's youngest brother, Nigel de Bruce, as well as Robert Boyd and Alexander Lindsay, and Sir Simon Fraser. Boyd managed to escape but both Nigel de Bruce and Lindsay were executed shortly after at Berwick following King Edward's orders to execute all followers of Robert de Bruce. Fraser was taken to London to suffer the same fate. Shortly before the fall of Kildrummy Castle, the Earl of Athol made a desperate attempt to take Queen Elizabeth de Burgh, Margery de Bruce, as well as King Robert's sisters and Isabella of Fife. They were betrayed a few days later and also fell into English hands, Atholl to be executed in London and the women to be held under the harshest possible circumstances.

It is still uncertain where Bruce spent the winter of 1306–07. Most likely he spent it in the Hebrides

The Hebrides (; gd, Innse Gall, ; non, Suðreyjar, "southern isles") are an archipelago off the west coast of the Scottish mainland. The islands fall into two main groups, based on their proximity to the mainland: the Inner and Outer Hebrid ...

, possibly sheltered by Christina of the Isles. The latter was married to a member of the Mar kindred, a family to which Bruce was related (not only was his first wife a member of this family but her brother, Gartnait, was married to a sister of Bruce). Ireland is also a serious possibility, and Orkney

Orkney (; sco, Orkney; on, Orkneyjar; nrn, Orknøjar), also known as the Orkney Islands, is an archipelago in the Northern Isles of Scotland, situated off the north coast of the island of Great Britain. Orkney is 10 miles (16 km) north ...

(under Norwegian rule at the time) or Norway proper (where his sister Isabel Bruce

Isabel Bruce (''Isabella de Brus'' or ''Isobail a Brus'', or ''Isabella Robertsdotter Brus'') (c. 1272–1358) was Queen of Norway as the wife of King Eric II.

Background

Isabel was born in Carrick, Scotland. Her parents were Robert de Brus ...

was queen dowager) are unlikely but not impossible. Bruce and his followers returned to the Scottish mainland in February 1307 in two groups. One, led by Bruce and his brother Edward

Edward is an English given name. It is derived from the Anglo-Saxon name ''Ēadweard'', composed of the elements '' ēad'' "wealth, fortune; prosperous" and '' weard'' "guardian, protector”.

History

The name Edward was very popular in Anglo-Sa ...

, landed at Turnberry Castle