King Richard II of England on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Richard II (6 January 1367 – ), also known as Richard of Bordeaux, was

Richard of Bordeaux was the younger son of Edward, Prince of Wales, and

Richard of Bordeaux was the younger son of Edward, Prince of Wales, and  On 21 June 1377, Richard's grandfather King Edward III, who was for some years frail and decrepit, died after a 50-year reign. This resulted in the 10-year-old Richard succeeding to the throne. He was crowned on 16 July at

On 21 June 1377, Richard's grandfather King Edward III, who was for some years frail and decrepit, died after a 50-year reign. This resulted in the 10-year-old Richard succeeding to the throne. He was crowned on 16 July at

Whereas the poll tax of 1381 was the spark of the

Whereas the poll tax of 1381 was the spark of the

It is only with the Peasants' Revolt that Richard starts to emerge clearly in the

It is only with the Peasants' Revolt that Richard starts to emerge clearly in the

The threat of a French invasion did not subside, but instead grew stronger into 1386. At the parliament of October that year, Michael de la Polein his capacity of chancellorrequested taxation of an unprecedented level for the defence of the realm. Rather than consenting, the parliament responded by refusing to consider any request until the chancellor was removed. The parliament (later known as the

The threat of a French invasion did not subside, but instead grew stronger into 1386. At the parliament of October that year, Michael de la Polein his capacity of chancellorrequested taxation of an unprecedented level for the defence of the realm. Rather than consenting, the parliament responded by refusing to consider any request until the chancellor was removed. The parliament (later known as the

Richard gradually re-established royal authority in the months after the deliberations of the Merciless Parliament. The aggressive foreign policy of the Lords Appellant failed when their efforts to build a wide, anti-French coalition came to nothing, and the north of England fell victim to a Scottish incursion. Richard was now over twenty-one years old and could with confidence claim the right to govern in his own name.Saul (1997), pp. 203–204. Furthermore, John of Gaunt returned to England in 1389 and settled his differences with the king, after which the old statesman acted as a moderating influence on English politics. Richard assumed full control of the government on 3 May 1389, claiming that the difficulties of the past years had been due solely to bad councillors. He outlined a foreign policy that reversed the actions of the appellants by seeking peace and reconciliation with France, and promised to lessen the burden of taxation on the people significantly. Richard ruled peacefully for the next eight years, having reconciled with his former adversaries. Still, later events would show that he had not forgotten the indignities he perceived. In particular, the execution of his former teacher Sir Simon de Burley was an insult not easily forgotten.

Richard gradually re-established royal authority in the months after the deliberations of the Merciless Parliament. The aggressive foreign policy of the Lords Appellant failed when their efforts to build a wide, anti-French coalition came to nothing, and the north of England fell victim to a Scottish incursion. Richard was now over twenty-one years old and could with confidence claim the right to govern in his own name.Saul (1997), pp. 203–204. Furthermore, John of Gaunt returned to England in 1389 and settled his differences with the king, after which the old statesman acted as a moderating influence on English politics. Richard assumed full control of the government on 3 May 1389, claiming that the difficulties of the past years had been due solely to bad councillors. He outlined a foreign policy that reversed the actions of the appellants by seeking peace and reconciliation with France, and promised to lessen the burden of taxation on the people significantly. Richard ruled peacefully for the next eight years, having reconciled with his former adversaries. Still, later events would show that he had not forgotten the indignities he perceived. In particular, the execution of his former teacher Sir Simon de Burley was an insult not easily forgotten.

With national stability secured, Richard began negotiating a permanent peace with France. A proposal put forward in 1393 would have greatly expanded the territory of

With national stability secured, Richard began negotiating a permanent peace with France. A proposal put forward in 1393 would have greatly expanded the territory of

These actions were made possible primarily through the collusion of John of Gaunt, but with the support of a large group of other magnates, many of whom were rewarded with new titles, and were disparagingly referred to as Richard's "duketti".Saul (2005), p. 63. These included the former Lords Appellant

* Henry Bolingbroke, Earl of Derby, who was made

These actions were made possible primarily through the collusion of John of Gaunt, but with the support of a large group of other magnates, many of whom were rewarded with new titles, and were disparagingly referred to as Richard's "duketti".Saul (2005), p. 63. These included the former Lords Appellant

* Henry Bolingbroke, Earl of Derby, who was made

In the last years of Richard's reign, and particularly in the months after the suppression of the appellants in 1397, the king enjoyed a virtual monopoly on power in the country, a relatively uncommon situation in medieval England. In this period a particular court culture was allowed to emerge, one that differed sharply from that of earlier times. A new form of address developed; where the king previously had been addressed simply as "

In the last years of Richard's reign, and particularly in the months after the suppression of the appellants in 1397, the king enjoyed a virtual monopoly on power in the country, a relatively uncommon situation in medieval England. In this period a particular court culture was allowed to emerge, one that differed sharply from that of earlier times. A new form of address developed; where the king previously had been addressed simply as "

In June 1399,

In June 1399,  According to the official record, read by the Archbishop of Canterbury during an assembly of

According to the official record, read by the Archbishop of Canterbury during an assembly of

The popular view of Richard has more than anything been influenced by

The popular view of Richard has more than anything been influenced by

Historia Anglicana

' 2 vols., ed.

Richard II's Treasure

from the

Richard II's Irish chancery rolls

listed by year, translated, published online by CIRCLE.

The Peasants' Revolt

BBC Radio 4 discussion with Miri Rubin, Caroline Barron & Alastair Dunn (''In Our Time'', 16 November 2006) , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Richard 02 Of England 1367 births 1400 deaths 14th-century English monarchs 14th-century murdered monarchs 14th-century English nobility Burials at Westminster Abbey Children of Edward the Black Prince Deaths by starvation Dukes of Cornwall English people of French descent English pretenders to the French throne English Roman Catholics House of Plantagenet Knights of the Garter Medieval child rulers Monarchs who abdicated Peasants' Revolt Peers created by Edward III People from Bordeaux Princes of Wales Prisoners in the Tower of London Royal reburials

King of England

The monarchy of the United Kingdom, commonly referred to as the British monarchy, is the constitutional form of government by which a hereditary sovereign reigns as the head of state of the United Kingdom, the Crown Dependencies (the Bailiw ...

from 1377 until he was deposed

Deposition by political means concerns the removal of a politician or monarch.

ORB: The Online Reference for Med ...

in 1399. He was the son of ORB: The Online Reference for Med ...

Edward the Black Prince

Edward of Woodstock, known to history as the Black Prince (15 June 1330 – 8 June 1376), was the eldest son of King Edward III of England, and the heir apparent to the English throne. He died before his father and so his son, Richard II, su ...

, Prince of Wales, and Joan, Countess of Kent

Joan, Countess of Kent (29 September 1326/1327 – 7 August 1385), known as The Fair Maid of Kent, was the mother of King Richard II of England, her son by her third husband, Edward the Black Prince, son and heir apparent of King Edward III. A ...

. Richard's father died in 1376, leaving Richard as heir apparent

An heir apparent, often shortened to heir, is a person who is first in an order of succession and cannot be displaced from inheriting by the birth of another person; a person who is first in the order of succession but can be displaced by the b ...

to his grandfather, King Edward III

Edward III (13 November 1312 – 21 June 1377), also known as Edward of Windsor before his accession, was King of England and Lord of Ireland from January 1327 until his death in 1377. He is noted for his military success and for restoring ro ...

; upon the latter's death, the 10-year-old Richard succeeded to the throne.

During Richard's first years as king, government was in the hands of a series of regency

A regent (from Latin : ruling, governing) is a person appointed to govern a state '' pro tempore'' (Latin: 'for the time being') because the monarch is a minor, absent, incapacitated or unable to discharge the powers and duties of the monarchy ...

councils, influenced by Richard's uncles John of Gaunt

John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster (6 March 1340 – 3 February 1399) was an English royal prince, military leader, and statesman. He was the fourth son (third to survive infancy as William of Hatfield died shortly after birth) of King Edward ...

and Thomas of Woodstock

Thomas of Woodstock, 1st Duke of Gloucester (7 January 13558 or 9 September 1397) was the fifth surviving son and youngest child of King Edward III of England and Philippa of Hainault.

Early life

Thomas was born on 7 January 1355 at Woodstock ...

. England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe b ...

then faced various problems, most notably the Hundred Years' War

The Hundred Years' War (; 1337–1453) was a series of armed conflicts between the kingdoms of Kingdom of England, England and Kingdom of France, France during the Late Middle Ages. It originated from disputed claims to the French Crown, ...

. A major challenge of the reign was the Peasants' Revolt

The Peasants' Revolt, also named Wat Tyler's Rebellion or the Great Rising, was a major uprising across large parts of England in 1381. The revolt had various causes, including the socio-economic and political tensions generated by the Black ...

in 1381, and the young king played a central part in the successful suppression of this crisis. Less warlike than either his father or grandfather, he sought to bring an end to the Hundred Years' War. A firm believer in the royal prerogative

The royal prerogative is a body of customary authority, privilege and immunity, recognized in common law and, sometimes, in civil law jurisdictions possessing a monarchy, as belonging to the sovereign and which have become widely vested in th ...

, Richard restrained the power of the aristocracy and relied on a private retinue

A retinue is a body of persons "retained" in the service of a noble, royal personage, or dignitary; a ''suite'' (French "what follows") of retainers.

Etymology

The word, recorded in English since circa 1375, stems from Old French ''retenue'', it ...

for military protection instead. In contrast to his grandfather, Richard cultivated a refined atmosphere centred on art and culture at court, in which the king was an elevated figure.

The king's dependence on a small number of courtiers caused discontent among the influential, and in 1387 control of government was taken over by a group of aristocrats known as the Lords Appellant

The Lords Appellant were a group of nobles in the reign of King Richard II, who, in 1388, sought to impeach some five of the King's favourites in order to restrain what was seen as tyrannical and capricious rule. The word ''appellant'' — still u ...

. By 1389 Richard had regained control, and for the next eight years governed in relative harmony with his former opponents. In 1397, he took his revenge on the Appellants, many of whom were executed or exiled. The next two years have been described by historians as Richard's "tyranny". In 1399, after John of Gaunt died, the king disinherited Gaunt's son, Henry Bolingbroke

Henry IV ( April 1367 – 20 March 1413), also known as Henry Bolingbroke, was King of England from 1399 to 1413. He asserted the claim of his grandfather King Edward III, a maternal grandson of Philip IV of France, to the Kingdom of Fran ...

, who had previously been exiled. Henry invaded England in June 1399 with a small force that quickly grew in numbers. Meeting little resistance, he deposed Richard and had himself crowned king. Richard is thought to have been starved to death in captivity, although questions remain regarding his final fate.

Richard's posthumous reputation has been shaped to a large extent by William Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 26 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's nation ...

, whose play ''Richard II

Richard II (6 January 1367 – ), also known as Richard of Bordeaux, was King of England from 1377 until he was deposed in 1399. He was the son of Edward the Black Prince, Prince of Wales, and Joan, Countess of Kent. Richard's father died ...

'' portrayed Richard's misrule and his deposition as responsible for the 15th-century Wars of the Roses

The Wars of the Roses (1455–1487), known at the time and for more than a century after as the Civil Wars, were a series of civil wars fought over control of the English throne in the mid-to-late fifteenth century. These wars were fought bet ...

. Modern historians do not accept this interpretation, while not exonerating Richard from responsibility for his own deposition. While probably not insane, as many historians of the 19th and 20th centuries believed, he may have had a personality disorder

Personality disorders (PD) are a class of mental disorders characterized by enduring maladaptive patterns of behavior, cognition, and inner experience, exhibited across many contexts and deviating from those accepted by the individual's culture ...

, particularly manifesting itself towards the end of his reign. Most authorities agree that his policies were not unrealistic or even entirely unprecedented, but that the way in which he carried them out was unacceptable to the political establishment, leading to his downfall.

Early life

Richard of Bordeaux was the younger son of Edward, Prince of Wales, and

Richard of Bordeaux was the younger son of Edward, Prince of Wales, and Joan, Countess of Kent

Joan, Countess of Kent (29 September 1326/1327 – 7 August 1385), known as The Fair Maid of Kent, was the mother of King Richard II of England, her son by her third husband, Edward the Black Prince, son and heir apparent of King Edward III. A ...

. Edward, eldest son of Edward III

Edward III (13 November 1312 – 21 June 1377), also known as Edward of Windsor before his accession, was King of England and Lord of Ireland from January 1327 until his death in 1377. He is noted for his military success and for restoring r ...

and heir apparent

An heir apparent, often shortened to heir, is a person who is first in an order of succession and cannot be displaced from inheriting by the birth of another person; a person who is first in the order of succession but can be displaced by the b ...

to the throne of England, had distinguished himself as a military commander in the early phases of the Hundred Years' War

The Hundred Years' War (; 1337–1453) was a series of armed conflicts between the kingdoms of Kingdom of England, England and Kingdom of France, France during the Late Middle Ages. It originated from disputed claims to the French Crown, ...

, particularly in the Battle of Poitiers

The Battle of Poitiers was fought on 19September 1356 between a French army commanded by King JohnII and an Anglo- Gascon force under Edward, the Black Prince, during the Hundred Years' War. It took place in western France, south of Poi ...

in 1356. After further military adventures, however, he contracted dysentery

Dysentery (UK pronunciation: , US: ), historically known as the bloody flux, is a type of gastroenteritis that results in bloody diarrhea. Other symptoms may include fever, abdominal pain, and a feeling of incomplete defecation. Complications ...

in Spain in 1370. He never fully recovered and had to return to England the next year.

Richard was born at the Archbishop's Palace of Bordeaux

The Palais Rohan is the name of the Hôtel de Ville, or City Hall, of Bordeaux, France. The building was constructed from 1771 to 1784, originally serving as the Archbishop's Palace of Bordeaux.

History

In 1771, the new Archbishop of Bordeaux, ...

, in the English principality of Aquitaine

Aquitaine ( , , ; oc, Aquitània ; eu, Akitania; Poitevin-Saintongeais: ''Aguiéne''), archaic Guyenne or Guienne ( oc, Guiana), is a historical region of southwestern France and a former administrative region of the country. Since 1 January ...

, on 6 January 1367. According to contemporary sources, three kings, "the King of Castile

This is a list of kings and queens of the Kingdom and Crown of Castile. For their predecessors, see List of Castilian counts.

Kings and Queens of Castile

Jiménez dynasty

House of Ivrea

The following dynasts are descendants, in the ma ...

, the King of Navarre

This is a list of the kings and queens of kingdom of Pamplona, Pamplona, later kingdom of Navarre, Navarre. Pamplona was the primary name of the kingdom until its union with Kingdom of Aragon, Aragon (1076–1134). However, the territorial desig ...

and the King of Portugal

This is a list of Portuguese monarchs who ruled from the establishment of the Kingdom of Portugal, in 1139, to the deposition of the Portuguese monarchy and creation of the Portuguese Republic with the 5 October 1910 revolution.

Through the n ...

", were present at his birth.Tuck (2004). This anecdote, and the fact that his birth fell on the feast of Epiphany

Epiphany may refer to:

* Epiphany (feeling), an experience of sudden and striking insight

Religion

* Epiphany (holiday), a Christian holiday celebrating the revelation of God the Son as a human being in Jesus Christ

** Epiphany season, or Epiph ...

, was later used in the religious imagery of the Wilton Diptych

The Wilton Diptych () is a small portable diptych of two hinged panels, painted on both sides, now in the National Gallery, London. It is an extremely rare survival of a late medieval religious panel painting from England.

The diptych was pain ...

, where Richard is one of three kings paying homage to the Virgin and Child

In art, a Madonna () is a representation of Mary, either alone or with her child Jesus. These images are central icons for both the Catholic and Orthodox churches. The word is (archaic). The Madonna and Child type is very prevalent in ...

.

Richard's elder brother, Edward of Angoulême, died near his sixth birthday in 1371. The Prince of Wales finally succumbed to his long illness in June 1376. The Commons

The commons is the cultural and natural resources accessible to all members of a society, including natural materials such as air, water, and a habitable Earth. These resources are held in common even when owned privately or publicly. Commons ...

in the English Parliament

The Parliament of England was the legislature of the Kingdom of England from the 13th century until 1707 when it was replaced by the Parliament of Great Britain. Parliament evolved from the great council of bishops and peers that advised ...

genuinely feared that Richard's uncle, John of Gaunt

John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster (6 March 1340 – 3 February 1399) was an English royal prince, military leader, and statesman. He was the fourth son (third to survive infancy as William of Hatfield died shortly after birth) of King Edward ...

, would usurp

A usurper is an illegitimate or controversial claimant to power, often but not always in a monarchy. In other words, one who takes the power of a country, city, or established region for oneself, without any formal or legal right to claim it as ...

the throne. For this reason, Richard was quickly invested with the princedom of Wales

Prince of Wales ( cy, Tywysog Cymru, ; la, Princeps Cambriae/Walliae) is a title traditionally given to the heir apparent to the English and later British throne. Prior to the conquest by Edward I in the 13th century, it was used by the rulers ...

and his father's other titles.

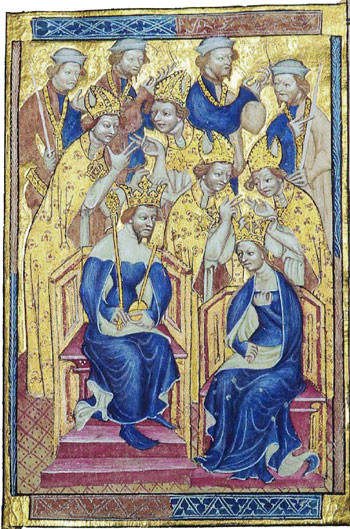

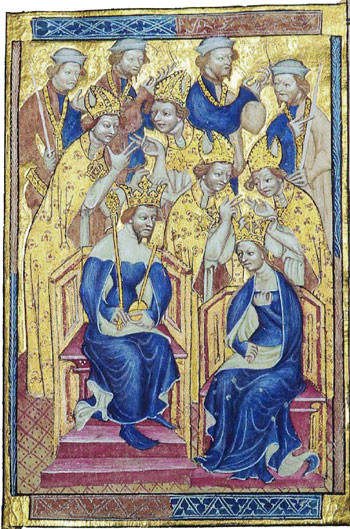

On 21 June 1377, Richard's grandfather King Edward III, who was for some years frail and decrepit, died after a 50-year reign. This resulted in the 10-year-old Richard succeeding to the throne. He was crowned on 16 July at

On 21 June 1377, Richard's grandfather King Edward III, who was for some years frail and decrepit, died after a 50-year reign. This resulted in the 10-year-old Richard succeeding to the throne. He was crowned on 16 July at Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an historic, mainly Gothic church in the City of Westminster, London, England, just to the west of the Palace of Westminster. It is one of the United ...

. Again, fears of John of Gaunt's ambitions influenced political decisions, and a regency led by the king's uncles was avoided. Instead, the king was nominally to exercise kingship with the help of a series of "continual councils", from which Gaunt was excluded.

Gaunt, together with his younger brother Thomas of Woodstock, Earl of Buckingham, still held great informal influence over the business of government, but the king's councillors and friends, particularly Sir Simon de Burley

Sir Simon de Burley, KG (ca. 1336 – 5 May 1388) was holder of the offices of Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports and Constable of Dover Castle between 1384–88, and was a Knight of the Garter.

Life

Sir Simon Burley was one of the most influent ...

and Robert de Vere, 9th Earl of Oxford

Robert de Vere, Duke of Ireland, KG (16 January 1362 – 22 November 1392) was a favourite and court companion of King Richard II of England. He was the ninth Earl of Oxford and the first and only Duke of Ireland and Marquess of Dublin. He ...

, increasingly gained control of royal affairs.

In a matter of three years, these councillors earned the mistrust of the Commons to the point that the councils were discontinued in 1380. Contributing to discontent was an increasingly heavy burden of taxation

A tax is a compulsory financial charge or some other type of levy imposed on a taxpayer (an individual or legal person, legal entity) by a governmental organization in order to fund government spending and various public expenditures (regiona ...

levied through three poll tax

A poll tax, also known as head tax or capitation, is a tax levied as a fixed sum on every liable individual (typically every adult), without reference to income or resources.

Head taxes were important sources of revenue for many governments fr ...

es between 1377 and 1381 that were spent on unsuccessful military expeditions on the continent. By 1381, there was a deep-felt resentment against the governing classes in the lower levels of English society.

Early reign

Peasants' Revolt

Whereas the poll tax of 1381 was the spark of the

Whereas the poll tax of 1381 was the spark of the Peasants' Revolt

The Peasants' Revolt, also named Wat Tyler's Rebellion or the Great Rising, was a major uprising across large parts of England in 1381. The revolt had various causes, including the socio-economic and political tensions generated by the Black ...

, the root of the conflict lay in tensions between peasants and landowners precipitated by the economic and demographic consequences of the Black Death

The Black Death (also known as the Pestilence, the Great Mortality or the Plague) was a bubonic plague pandemic occurring in Western Eurasia and North Africa from 1346 to 1353. It is the most fatal pandemic recorded in human history, causi ...

and subsequent outbreaks of the plague. The rebellion started in Kent

Kent is a county in South East England and one of the home counties. It borders Greater London to the north-west, Surrey to the west and East Sussex to the south-west, and Essex to the north across the estuary of the River Thames; it faces ...

and Essex

Essex () is a county in the East of England. One of the home counties, it borders Suffolk and Cambridgeshire to the north, the North Sea to the east, Hertfordshire to the west, Kent across the estuary of the River Thames to the south, and G ...

in late May, and on 12 June, bands of peasants gathered at Blackheath Blackheath may refer to:

Places England

*Blackheath, London, England

** Blackheath railway station

**Hundred of Blackheath, Kent, an ancient hundred in the north west of the county of Kent, England

*Blackheath, Surrey, England

** Hundred of Blackh ...

near London under the leaders Wat Tyler

Wat Tyler (c. 1320/4 January 1341 – 15 June 1381) was a leader of the 1381 Peasants' Revolt in England. He led a group of rebels from Canterbury to London to oppose the institution of a poll tax and to demand economic and social reforms. Wh ...

, John Ball, and Jack Straw

John Whitaker Straw (born 3 August 1946) is a British politician who served in the Cabinet from 1997 to 2010 under the Labour governments of Tony Blair and Gordon Brown. He held two of the traditional Great Offices of State, as Home Secretary ...

. John of Gaunt's Savoy Palace

The Savoy Palace, considered the grandest nobleman's townhouse of medieval London, was the residence of prince John of Gaunt until it was destroyed during rioting in the Peasants' Revolt of 1381. The palace was on the site of an estate given to ...

was burnt down. The Archbishop of Canterbury

The archbishop of Canterbury is the senior bishop and a principal leader of the Church of England, the ceremonial head of the worldwide Anglican Communion and the diocesan bishop of the Diocese of Canterbury. The current archbishop is Justi ...

, Simon Sudbury

Simon Sudbury ( – 14 June 1381) was Bishop of London from 1361 to 1375, Archbishop of Canterbury from 1375 until his death, and in the last year of his life Lord Chancellor of England. He met a violent death during the Peasants' Revolt in 138 ...

, who was also Lord Chancellor

The lord chancellor, formally the lord high chancellor of Great Britain, is the highest-ranking traditional minister among the Great Officers of State in Scotland and England in the United Kingdom, nominally outranking the prime minister. The ...

, and Lord High Treasurer

The post of Lord High Treasurer or Lord Treasurer was an English government position and has been a British government position since the Acts of Union of 1707. A holder of the post would be the third-highest-ranked Great Officer of State in ...

Robert Hales

Sir Robert Hales ( – 14 June 1381) was Grand Prior of the Knights Hospitaller of England, Lord High Treasurer, and Admiral of the West. He was killed in the Peasants' Revolt.

Career

In 1372 Robert Hales became the Lord/Grand Prior of th ...

were both killed by the rebels, who were demanding the complete abolition of serfdom

Serfdom was the status of many peasants under feudalism, specifically relating to manorialism, and similar systems. It was a condition of debt bondage and indentured servitude with similarities to and differences from slavery, which develop ...

.Harriss (2006), p. 231. The king, sheltered within the Tower of London

The Tower of London, officially His Majesty's Royal Palace and Fortress of the Tower of London, is a historic castle on the north bank of the River Thames in central London. It lies within the London Borough of Tower Hamlets, which is separa ...

with his councillors, agreed that the Crown did not have the forces to disperse the rebels and that the only feasible option was to negotiate.

It is unclear how much Richard, who was still only fourteen years old, was involved in these deliberations, although historians have suggested that he was among the proponents of negotiations. The king set out by the River Thames

The River Thames ( ), known alternatively in parts as the The Isis, River Isis, is a river that flows through southern England including London. At , it is the longest river entirely in England and the Longest rivers of the United Kingdom, se ...

on 13 June, but the large number of people thronging the banks at Greenwich

Greenwich ( , ,) is a town in south-east London, England, within the ceremonial county of Greater London. It is situated east-southeast of Charing Cross.

Greenwich is notable for its maritime history and for giving its name to the Greenwich ...

made it impossible for him to land, forcing him to return to the Tower. The next day, Friday, 14 June, he set out by horse and met the rebels at Mile End

Mile End is a district of the London Borough of Tower Hamlets in the East End of London, England, east-northeast of Charing Cross. Situated on the London-to-Colchester road, it was one of the earliest suburbs of London. It became part of the m ...

. He agreed to the rebels' demands, but this move only emboldened them; they continued their looting and killings. Richard met Wat Tyler again the next day at Smithfield and reiterated that the demands would be met, but the rebel leader was not convinced of the king's sincerity. The king's men grew restive, an altercation broke out, and William Walworth

Sir William Walworth (died 1385) was an English nobleman and politician who was twice Lord Mayor of London (1374–75 and 1380–81). He is best known for killing Wat Tyler during the Peasants' Revolt in 1381.

Political career

His family cam ...

, the Lord Mayor of London

The Lord Mayor of London is the mayor of the City of London and the leader of the City of London Corporation. Within the City, the Lord Mayor is accorded precedence over all individuals except the sovereign and retains various traditional powe ...

, pulled Tyler down from his horse and killed him. The situation became tense once the rebels realised what had happened, but the king acted with calm resolve and, saying "I am your captain, follow me!", he led the mob away from the scene. Walworth meanwhile gathered a force to surround the peasant army, but the king granted clemency and allowed the rebels to disperse and return to their homes.

The king soon revoked the charters of freedom and pardon that he had granted, and as disturbances continued in other parts of the country, he personally went into Essex to suppress the rebellion. On 28 June at Billericay

Billericay ( ) is a town and civil parish in the Borough of Basildon, Essex, England. It lies within the London Basin and constitutes a commuter town east of Central London. The town has three secondary schools and a variety of open spaces. It is ...

, he defeated the last rebels in a small skirmish and effectively ended the Peasants' Revolt. Despite his young age, Richard had shown great courage and determination in his handling of the rebellion. It is likely, though, that the events impressed upon him the dangers of disobedience and threats to royal authority, and helped shape the absolutist attitudes to kingship that would later prove fatal to his reign.

Coming of age

It is only with the Peasants' Revolt that Richard starts to emerge clearly in the

It is only with the Peasants' Revolt that Richard starts to emerge clearly in the annals

Annals ( la, annāles, from , "year") are a concise historical record in which events are arranged chronologically, year by year, although the term is also used loosely for any historical record.

Scope

The nature of the distinction between ann ...

. One of his first significant acts after the rebellion was to marry Anne of Bohemia

Anne of Bohemia (11 May 1366 – 7 June 1394), also known as Anne of Luxembourg, was Queen of England as the first wife of King Richard II. A member of the House of Luxembourg, she was the eldest daughter of Charles IV, Holy Roman Emperor and ...

, daughter of Charles IV, Holy Roman Emperor

Charles IV ( cs, Karel IV.; german: Karl IV.; la, Carolus IV; 14 May 1316 – 29 November 1378''Karl IV''. In: (1960): ''Geschichte in Gestalten'' (''History in figures''), vol. 2: ''F–K''. 38, Frankfurt 1963, p. 294), also known as Charle ...

, on 20 January 1382. It had diplomatic significance; in the division of Europe caused by the Western Schism

The Western Schism, also known as the Papal Schism, the Vatican Standoff, the Great Occidental Schism, or the Schism of 1378 (), was a split within the Catholic Church lasting from 1378 to 1417 in which bishops residing in Rome and Avignon bo ...

, Bohemia

Bohemia ( ; cs, Čechy ; ; hsb, Čěska; szl, Czechy) is the westernmost and largest historical region of the Czech Republic. Bohemia can also refer to a wider area consisting of the historical Lands of the Bohemian Crown ruled by the Bohem ...

and the Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a Polity, political entity in Western Europe, Western, Central Europe, Central, and Southern Europe that developed during the Early Middle Ages and continued until its Dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire, dissolution i ...

were seen as potential allies against France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

in the ongoing Hundred Years' War. Nonetheless, the marriage was not popular in England. Despite great sums of money awarded to the Empire, the political alliance never resulted in any military victories. Furthermore, the marriage was childless. Anne died from plague in 1394, greatly mourned by her husband.

Michael de la Pole had been instrumental in the marriage negotiations; he had the king's confidence and gradually became more involved at court and in government as Richard came of age. De la Pole came from an upstart merchant family. When Richard made him chancellor in 1383, and created him Earl of Suffolk

Earl of Suffolk is a title which has been created four times in the Peerage of England. The first creation, in tandem with the creation of the title of Earl of Norfolk, came before 1069 in favour of Ralph the Staller; but the title was forfei ...

two years later, this antagonised the more established nobility. Another member of the close circle around the king was Robert de Vere, Earl of Oxford, who in this period emerged as the king's favourite

A favourite (British English) or favorite (American English) was the intimate companion of a ruler or other important person. In post-classical and early-modern Europe, among other times and places, the term was used of individuals delegated si ...

. Richard's close friendship to de Vere was also disagreeable to the political establishment. This displeasure was exacerbated by the earl's elevation to the new title of Duke of Ireland

The title of Duke of Ireland was created in 1386 for Robert de Vere, 9th Earl of Oxford (1362–1392), the favourite of King Richard II of England, who had previously been created Marquess of Dublin. Both were peerages for one life only. At thi ...

in 1386. The chronicler Thomas Walsingham

Thomas Walsingham (died c. 1422) was an English chronicler, and is the source of much of the knowledge of the reigns of Richard II, Henry IV and Henry V, and the careers of John Wycliff and Wat Tyler.

Walsingham was a Benedictine monk who sp ...

suggested the relationship between the king and de Vere was of a homosexual nature, due to a resentment Walsingham had toward the king.

Tensions came to a head over the approach to the war in France. While the court party preferred negotiations, Gaunt and Buckingham urged a large-scale campaign to protect English possessions. Instead, a so-called crusade

The Crusades were a series of religious wars initiated, supported, and sometimes directed by the Latin Church in the medieval period. The best known of these Crusades are those to the Holy Land in the period between 1095 and 1291 that were i ...

led by Henry le Despenser

Henry le Despenser ( 1341 – 23 August 1406) was an English nobleman and Bishop of Norwich whose reputation as the 'Fighting Bishop' was gained for his part in suppressing the Peasants' Revolt in East Anglia and in defeating the peasants at th ...

, Bishop of Norwich

The Bishop of Norwich is the ordinary of the Church of England Diocese of Norwich in the Province of Canterbury. The diocese covers most of the county of Norfolk and part of Suffolk. The bishop of Norwich is Graham Usher.

The see is in the ...

, was dispatched, which failed miserably. Faced with this setback on the continent, Richard turned his attention instead towards France's ally, the Kingdom of Scotland

The Kingdom of Scotland (; , ) was a sovereign state in northwest Europe traditionally said to have been founded in 843. Its territories expanded and shrank, but it came to occupy the northern third of the island of Great Britain, sharing a la ...

. In 1385, the king himself led a punitive expedition to the north, but the effort came to nothing, and the army had to return without ever engaging the Scots in battle. Meanwhile, only an uprising in Ghent

Ghent ( nl, Gent ; french: Gand ; traditional English: Gaunt) is a city and a municipality in the Flemish Region of Belgium. It is the capital and largest city of the East Flanders province, and the third largest in the country, exceeded in ...

prevented a French invasion of southern England. The relationship between Richard and his uncle John of Gaunt deteriorated further with military failure, and Gaunt left England to pursue his claim to the throne of Castile in 1386 amid rumours of a plot against his person. With Gaunt gone, the unofficial leadership of the growing dissent against the king and his courtiers passed to Buckinghamwho had by now been created Duke of Gloucesterand Richard Fitzalan, 4th Earl of Arundel

Richard Fitzalan, 4th Earl of Arundel, 9th Earl of Surrey, KG (1346 – 21 September 1397) was an English medieval nobleman and military commander.

Lineage

Born in 1346, he was the son of Richard Fitzalan, 3rd Earl of Arundel and Eleanor of L ...

.

First crisis of 1386–88

The threat of a French invasion did not subside, but instead grew stronger into 1386. At the parliament of October that year, Michael de la Polein his capacity of chancellorrequested taxation of an unprecedented level for the defence of the realm. Rather than consenting, the parliament responded by refusing to consider any request until the chancellor was removed. The parliament (later known as the

The threat of a French invasion did not subside, but instead grew stronger into 1386. At the parliament of October that year, Michael de la Polein his capacity of chancellorrequested taxation of an unprecedented level for the defence of the realm. Rather than consenting, the parliament responded by refusing to consider any request until the chancellor was removed. The parliament (later known as the Wonderful Parliament

The Wonderful Parliament was a session of the English parliament held from October to November 1386 in Westminster Abbey. Originally called to address King Richard II's need for money, it quickly refocused on pressing for the reform of his adm ...

) was presumably working with the support of Gloucester and Arundel. The king famously responded that he would not dismiss as much as a scullion

Scullion may refer to:

* The Irish surname derived from 'Ó Scolláin' meaning 'descendant of the/a scholar'

* a servant from the lower classes.

Music

* Scullion (group), an Irish folk rock band

* ''Scullion'' (album)

People with the surname

...

from his kitchen at parliament's request. Only when threatened with deposition was Richard forced to give in and let de la Pole go. A commission was set up to review and control royal finances for a year.

Richard was deeply perturbed by this affront to his royal prerogative, and from February to November 1387 went on a "gyration" (tour) of the country to muster support for his cause. By installing de Vere as Justice of Chester

The Justice of Chester was the chief judicial authority for the county palatine of Chester, from the establishment of the county until the abolition of the Great Sessions in Wales and the palatine judicature in 1830.

Within the County Palatine (w ...

, he began the work of creating a loyal military power base in Cheshire

Cheshire ( ) is a ceremonial and historic county in North West England, bordered by Wales to the west, Merseyside and Greater Manchester to the north, Derbyshire to the east, and Staffordshire and Shropshire to the south. Cheshire's county t ...

. He also secured a legal ruling from Chief Justice Robert Tresilian

Sir Robert Tresilian (died 19 February 1388) was a Cornish lawyer, and Chief Justice of the King's Bench between 1381 and 1387. He was born in Cornwall, and held land in Tresillian, near Truro. Tresilian was deeply involved in the struggles betw ...

that parliament's conduct had been unlawful and treasonable.

On his return to London, the king was confronted by Gloucester, Arundel and Thomas de Beauchamp, 12th Earl of Warwick

Thomas may refer to:

People

* List of people with given name Thomas

* Thomas (name)

* Thomas (surname)

* Saint Thomas (disambiguation)

* Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274) Italian Dominican friar, philosopher, and Doctor of the Church

* Thomas the Ap ...

, who brought an appeal

In law, an appeal is the process in which cases are reviewed by a higher authority, where parties request a formal change to an official decision. Appeals function both as a process for error correction as well as a process of clarifying and ...

of treason against de la Pole, de Vere, Tresilian, and two other loyalists: the mayor of London, Nicholas Brembre

Sir Nicholas Brembre (died 20 February 1388) was a wealthy magnate and a chief ally of King Richard II in 14th-century England. He was Lord Mayor of London in 1377, and again from 1384–5,6. Named a "worthie and puissant man of the city" by Rich ...

, and Alexander Neville

Alexander Neville ( 1340–1392) was a late medieval prelate who served as Archbishop of York from 1374 to 1388.

Life

Born in about 1340, Alexander Neville was a younger son of Ralph Neville, 2nd Baron Neville de Raby and Alice de Audley. He ...

, the Archbishop of York

The archbishop of York is a senior bishop in the Church of England, second only to the archbishop of Canterbury. The archbishop is the diocesan bishop of the Diocese of York and the metropolitan bishop of the province of York, which covers th ...

. Richard stalled the negotiations to gain time, as he was expecting de Vere to arrive from Cheshire with military reinforcements.Saul (1997), p. 187. The three peers then joined forces with Gaunt's son Henry Bolingbroke

Henry IV ( April 1367 – 20 March 1413), also known as Henry Bolingbroke, was King of England from 1399 to 1413. He asserted the claim of his grandfather King Edward III, a maternal grandson of Philip IV of France, to the Kingdom of Fran ...

, Earl of Derby, and Thomas de Mowbray, Earl of Nottinghamthe group known to history as the Lords Appellant

The Lords Appellant were a group of nobles in the reign of King Richard II, who, in 1388, sought to impeach some five of the King's favourites in order to restrain what was seen as tyrannical and capricious rule. The word ''appellant'' — still u ...

. On 20 December 1387 they intercepted de Vere at Radcot Bridge

Radcot Bridge is a crossing of the Thames in England, south of Radcot, Oxfordshire, and north of Faringdon, Oxfordshire which is in the district of that county that was in Berkshire. It carries the A4095 road across the reach above Radcot L ...

, where he and his forces were routed and he was obliged to flee the country.

Richard now had no choice but to comply with the appellants' demands; Brembre and Tresilian were condemned and executed, while de Vere and de la Polewho had by now also left the countrywere sentenced to death ''in absentia'' at the Merciless Parliament

The Merciless Parliament was an English parliamentary session lasting from 3 February to 4 June 1388, at which many members of King Richard II's court were convicted of treason. The session was preceded by a period in which Richard's power was r ...

in February 1388. The proceedings went further, and a number of Richard's chamber knights were also executed, among these Burley. The appellants had now succeeded completely in breaking up the circle of favourites around the king.

Later reign

A fragile peace

Richard gradually re-established royal authority in the months after the deliberations of the Merciless Parliament. The aggressive foreign policy of the Lords Appellant failed when their efforts to build a wide, anti-French coalition came to nothing, and the north of England fell victim to a Scottish incursion. Richard was now over twenty-one years old and could with confidence claim the right to govern in his own name.Saul (1997), pp. 203–204. Furthermore, John of Gaunt returned to England in 1389 and settled his differences with the king, after which the old statesman acted as a moderating influence on English politics. Richard assumed full control of the government on 3 May 1389, claiming that the difficulties of the past years had been due solely to bad councillors. He outlined a foreign policy that reversed the actions of the appellants by seeking peace and reconciliation with France, and promised to lessen the burden of taxation on the people significantly. Richard ruled peacefully for the next eight years, having reconciled with his former adversaries. Still, later events would show that he had not forgotten the indignities he perceived. In particular, the execution of his former teacher Sir Simon de Burley was an insult not easily forgotten.

Richard gradually re-established royal authority in the months after the deliberations of the Merciless Parliament. The aggressive foreign policy of the Lords Appellant failed when their efforts to build a wide, anti-French coalition came to nothing, and the north of England fell victim to a Scottish incursion. Richard was now over twenty-one years old and could with confidence claim the right to govern in his own name.Saul (1997), pp. 203–204. Furthermore, John of Gaunt returned to England in 1389 and settled his differences with the king, after which the old statesman acted as a moderating influence on English politics. Richard assumed full control of the government on 3 May 1389, claiming that the difficulties of the past years had been due solely to bad councillors. He outlined a foreign policy that reversed the actions of the appellants by seeking peace and reconciliation with France, and promised to lessen the burden of taxation on the people significantly. Richard ruled peacefully for the next eight years, having reconciled with his former adversaries. Still, later events would show that he had not forgotten the indignities he perceived. In particular, the execution of his former teacher Sir Simon de Burley was an insult not easily forgotten.

With national stability secured, Richard began negotiating a permanent peace with France. A proposal put forward in 1393 would have greatly expanded the territory of

With national stability secured, Richard began negotiating a permanent peace with France. A proposal put forward in 1393 would have greatly expanded the territory of Aquitaine

Aquitaine ( , , ; oc, Aquitània ; eu, Akitania; Poitevin-Saintongeais: ''Aguiéne''), archaic Guyenne or Guienne ( oc, Guiana), is a historical region of southwestern France and a former administrative region of the country. Since 1 January ...

possessed by the English Crown. However, the plan failed because it included a requirement that the English king pay homage

Homage (Old English) or Hommage (French) may refer to:

History

*Homage (feudal) /ˈhɒmɪdʒ/, the medieval oath of allegiance

*Commendation ceremony, medieval homage ceremony Arts

*Homage (arts) /oʊˈmɑʒ/, an allusion or imitation by one arti ...

to the King of Francea condition that proved unacceptable to the English public. Instead, in 1396, a truce was agreed to, which was to last 28 years. As part of the truce, Richard agreed to marry Isabella of Valois

Isabella of France (9 November 1389 – 13 September 1409) was Queen of England as the wife of Richard II, King of England between 1396 and 1399, and Duchess (consort) of Orléans as the wife of Charles, Duke of Orléans from 1406 until her ...

, daughter of Charles VI of France

Charles VI (3 December 136821 October 1422), nicknamed the Beloved (french: le Bien-Aimé) and later the Mad (french: le Fol or ''le Fou''), was King of France from 1380 until his death in 1422. He is known for his mental illness and psychotic ...

, when she came of age. There were some misgivings about the betrothal, in particular because the princess was then only six years old, and thus would not be able to produce an heir to the throne of England for many years.

Although Richard sought peace with France, he took a different approach to the situation in Ireland. The English lordships in Ireland were in danger of being overrun by the Gaelic Irish kingdoms, and the Anglo-Irish

Anglo-Irish people () denotes an ethnic, social and religious grouping who are mostly the descendants and successors of the English Protestant Ascendancy in Ireland. They mostly belong to the Anglican Church of Ireland, which was the establis ...

lords were pleading for the king to intervene. In the autumn of 1394, Richard left for Ireland, where he remained until May 1395. His army of more than 8,000 men was the largest force brought to the island during the late Middle Ages. The invasion was a success, and a number of Irish chieftains submitted to English overlordship. It was one of the most successful achievements of Richard's reign, and strengthened his support at home, although the consolidation of the English position in Ireland proved to be short-lived.

Second crisis of 1397–99

The period that historians refer to as the "tyranny" of Richard II began towards the end of the 1390s. The king had Gloucester, Arundel and Warwick arrested in July 1397. The timing of these arrests and Richard's motivation are not entirely clear. Although one chronicle suggested that a plot was being planned against the king, there is no evidence that this was the case. It is more likely that Richard had simply come to feel strong enough to safely retaliate against these three men for their role in events of 1386–88 and eliminate them as threats to his power. Arundel was the first of the three to be brought to trial, at the parliament of September 1397. After a heated quarrel with the king, he was condemned and executed. Gloucester was being held prisoner by the Earl of Nottingham at Calais while awaiting his trial. As the time for the trial drew near, Nottingham brought news that Gloucester was dead. It is thought likely that the king had ordered him to be killed to avoid the disgrace of executing a prince of the blood. Warwick was also condemned to death, but his life was spared and his sentence reduced to life imprisonment. Arundel's brotherThomas Arundel

Thomas Arundel (1353 – 19 February 1414) was an English clergyman who served as Lord Chancellor and Archbishop of York during the reign of Richard II, as well as Archbishop of Canterbury in 1397 and from 1399 until his death, an outspoken o ...

, the Archbishop of Canterbury, was exiled for life. Richard then took his persecution of adversaries to the localities. While recruiting retainers

Retainer may refer to:

* Retainer (orthodontics), devices for teeth

* RFA ''Retainer'' (A329), a ship

* Retainers in early China, a social group in early China

Employment

* Retainer agreement, a contract in which an employer pays in advance for ...

for himself in various counties, he prosecuted local men who had been loyal to the appellants. The fines levied on these men brought great revenues to the crown, although contemporary chroniclers raised questions about the legality of the proceedings.

These actions were made possible primarily through the collusion of John of Gaunt, but with the support of a large group of other magnates, many of whom were rewarded with new titles, and were disparagingly referred to as Richard's "duketti".Saul (2005), p. 63. These included the former Lords Appellant

* Henry Bolingbroke, Earl of Derby, who was made

These actions were made possible primarily through the collusion of John of Gaunt, but with the support of a large group of other magnates, many of whom were rewarded with new titles, and were disparagingly referred to as Richard's "duketti".Saul (2005), p. 63. These included the former Lords Appellant

* Henry Bolingbroke, Earl of Derby, who was made Duke of Hereford

Duke of Hereford was a title in the Peerage of England. It was created in 1397 for Richard II's cousin, Henry Bolingbroke, due to his support for the King in his struggle against their uncle Thomas of Woodstock, 1st Duke of Gloucester. It merged ...

, and

* Thomas de Mowbray, Earl of Nottingham, who was created Duke of Norfolk

Duke of Norfolk is a title in the peerage of England. The seat of the Duke of Norfolk is Arundel Castle in Sussex, although the title refers to the county of Norfolk. The current duke is Edward Fitzalan-Howard, 18th Duke of Norfolk. The dukes ...

.

Also among them were

* John

John is a common English name and surname:

* John (given name)

* John (surname)

John may also refer to:

New Testament

Works

* Gospel of John, a title often shortened to John

* First Epistle of John, often shortened to 1 John

* Second ...

, the king's half-brother, promoted from earl of Huntingdon

Huntingdon is a market town in the Huntingdonshire district in Cambridgeshire, England. The town was given its town charter by King John in 1205. It was the county town of the historic county of Huntingdonshire. Oliver Cromwell was born there ...

to duke of Exeter

Exeter () is a city in Devon, South West England. It is situated on the River Exe, approximately northeast of Plymouth and southwest of Bristol.

In Roman Britain, Exeter was established as the base of Legio II Augusta under the personal comm ...

* Thomas Holland, the king's nephew, promoted from Earl of Kent

The peerage title Earl of Kent has been created eight times in the Peerage of England and once in the Peerage of the United Kingdom. In fiction, the Earl of Kent is also known as a prominent supporting character in William Shakespeare's tragedy K ...

to Duke of Surrey

Duke is a male title either of a monarch ruling over a duchy, or of a member of royalty, or nobility. As rulers, dukes are ranked below emperors, kings, grand princes, grand dukes, and sovereign princes. As royalty or nobility, they are ran ...

* Edward of Norwich, Earl of Rutland

Edward, 2nd Duke of York, ( – 25 October 1415) was an English Nobility, nobleman, military commander and magnate. He was the eldest son of Edmund of Langley, 1st Duke of York, and a grandson of Edward III of England, King Edward III of England ...

, the king's cousin, who received Gloucester's French title of Duke of Aumale

Duke is a male title either of a monarch ruling over a duchy, or of a member of royalty, or nobility. As rulers, dukes are ranked below emperors, kings, grand princes, grand dukes, and sovereign princes. As royalty or nobility, they are ranked ...

* Gaunt's son John Beaufort, 1st Earl of Somerset

John Beaufort, 1st Marquess of Somerset and 1st Marquess of Dorset, later only 1st Earl of Somerset, (c. 1373 – 16 March 1410) was an English nobleman and politician. He was the first of the four illegitimate children of John of Gaunt ...

, who was made Marquess of Somerset

A marquess (; french: marquis ), es, marqués, pt, marquês. is a nobleman of high hereditary rank in various European peerages and in those of some of their former colonies. The German language equivalent is Markgraf (margrave). A woman wi ...

and Marquess of Dorset

The title Marquess of Dorset has been created three times in the Peerage of England. It was first created in 1397 for John Beaufort, 1st Earl of Somerset, but he lost the title two years later. It was then created in 1442 for Edmund Beaufort, 1st ...

* John Montacute, 3rd Earl of Salisbury

John Montagu, 3rd Earl of Salisbury and 5th and 2nd Baron Montagu, KG (c. 1350 – 7 January 1400) was an English nobleman, one of the few who remained loyal to Richard II after Henry IV became king.

Early life

He was the son of Sir John de Mo ...

* Lord Thomas le Despenser, who became Earl of Gloucester

The title of Earl of Gloucester was created several times in the Peerage of England. A fictional earl is also a character in William Shakespeare's play ''King Lear.''

Earls of Gloucester, 1st Creation (1121)

*Robert, 1st Earl of Gloucester (1100� ...

.

With the forfeited lands of the convicted appellants, the king could reward these men with lands suited to their new ranks.McKisack (1959), pp. 483–484.

A threat to Richard's authority still existed, however, in the form of the House of Lancaster

The House of Lancaster was a cadet branch of the royal House of Plantagenet. The first house was created when King Henry III of England created the Earldom of Lancasterfrom which the house was namedfor his second son Edmund Crouchback in 126 ...

, represented by John of Gaunt and his son Henry Bolingbroke, Duke of Hereford. The House of Lancaster not only possessed greater wealth than any other family in England, they were of royal descent and, as such, likely candidates to succeed the childless Richard.

Discord broke out in the inner circles of court in December 1397, when Bolingbroke and Mowbray became embroiled in a quarrel. According to Bolingbroke, Mowbray had claimed that the two, as former Lords Appellant, were next in line for royal retribution. Mowbray vehemently denied these charges, as such a claim would have amounted to treason. A parliamentary committee decided that the two should settle the matter by battle, but at the last moment Richard exiled the two dukes instead: Mowbray for life, Bolingbroke for ten years.

In 1398 Richard summoned the Parliament of Shrewsbury, which declared all the acts of the Merciless Parliament to be null and void, and announced that no restraint could legally be put on the king. It delegated all parliamentary power to a committee of twelve lords and six commoners chosen from the king's friends, making Richard an absolute ruler unbound by the necessity of gathering a Parliament again.

On 3 February 1399, John of Gaunt died. Rather than allowing Bolingbroke to succeed, Richard extended the term of his exile to life and expropriated his properties. The king felt safe from Bolingbroke, who was residing in Paris, since the French had little interest in any challenge to Richard and his peace policy. Richard left the country in May for another expedition in Ireland.

Court culture

In the last years of Richard's reign, and particularly in the months after the suppression of the appellants in 1397, the king enjoyed a virtual monopoly on power in the country, a relatively uncommon situation in medieval England. In this period a particular court culture was allowed to emerge, one that differed sharply from that of earlier times. A new form of address developed; where the king previously had been addressed simply as "

In the last years of Richard's reign, and particularly in the months after the suppression of the appellants in 1397, the king enjoyed a virtual monopoly on power in the country, a relatively uncommon situation in medieval England. In this period a particular court culture was allowed to emerge, one that differed sharply from that of earlier times. A new form of address developed; where the king previously had been addressed simply as "highness

Highness (abbreviation HH, oral address Your Highness) is a formal style used to address (in second person) or refer to (in third person) certain members of a reigning or formerly reigning dynasty. It is typically used with a possessive adjecti ...

", now "royal majesty

Majesty (abbreviated HM for His Majesty or Her Majesty, oral address Your Majesty; from the Latin ''maiestas'', meaning "greatness") is used as a manner of address by many monarchs, usually kings or queens. Where used, the style outranks the st ...

", or "high majesty" were often used. It was said that on solemn festivals Richard would sit on his throne in the royal hall for hours without speaking, and anyone on whom his eyes fell had to bow his knees to the king. The inspiration for this new sumptuousness and emphasis on dignity came from the courts on the continent, not only the French and Bohemian courts that had been the homes of Richard's two wives, but also the court that his father had maintained while residing in Aquitaine.

Richard's approach to kingship was rooted in his strong belief in the royal prerogative

The royal prerogative is a body of customary authority, privilege and immunity, recognized in common law and, sometimes, in civil law jurisdictions possessing a monarchy, as belonging to the sovereign and which have become widely vested in th ...

, the inspiration of which can be found in his early youth, when his authority was challenged first by the Peasants' Revolts and then by the Lords Appellant. Richard rejected the approach his grandfather Edward III had taken to the nobility. Edward's court had been a martial one, based on the interdependence between the king and his most trusted noblemen as military captains. In Richard's view, this put a dangerous amount of power in the hands of the baronage. To avoid dependence on the nobility for military recruitment, he pursued a policy of peace towards France.Saul (1997), p. 439. At the same time, he developed his own private military retinue, larger than that of any English king before him, and gave them livery

A livery is an identifying design, such as a uniform, ornament, symbol or insignia that designates ownership or affiliation, often found on an individual or vehicle. Livery will often have elements of the heraldry relating to the individual or ...

badges

A badge is a device or accessory, often containing the insignia of an organization, which is presented or displayed to indicate some feat of service, a special accomplishment, a symbol of authority granted by taking an oath (e.g., police and fi ...

with his White Hart

The White Hart ("hart" being an archaic word for a mature stag) was the personal badge of Richard II, who probably derived it from the arms of his mother, Joan "The Fair Maid of Kent", heiress of Edmund of Woodstock. It may also have been a pun ...

. He was then free to develop a courtly atmosphere in which the king was a distant, venerated figure, and art and culture, rather than warfare, were at the centre.

Patronage and the arts

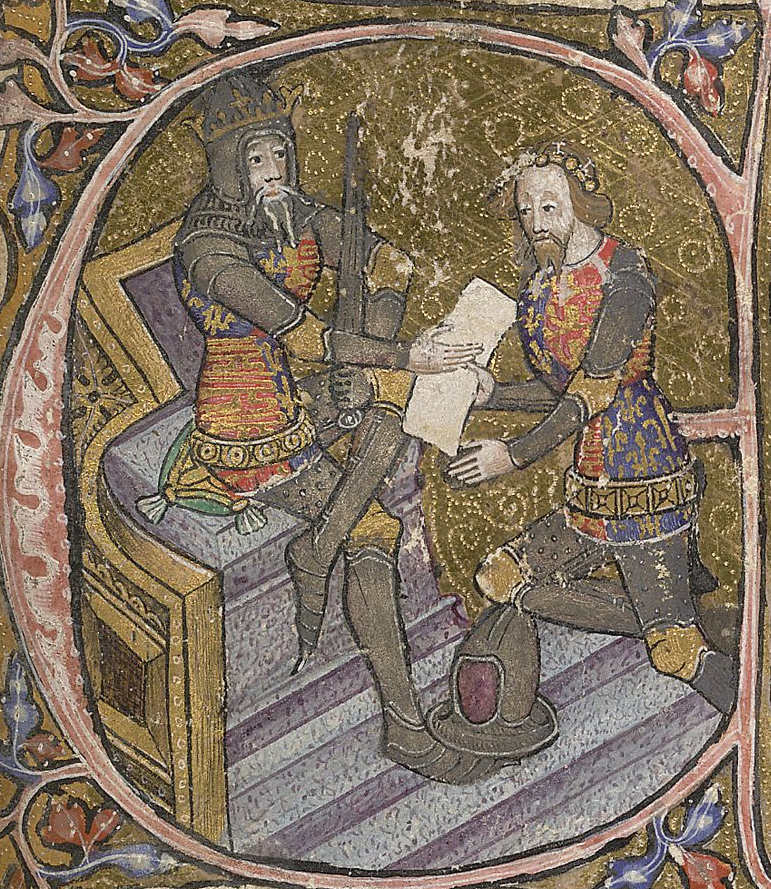

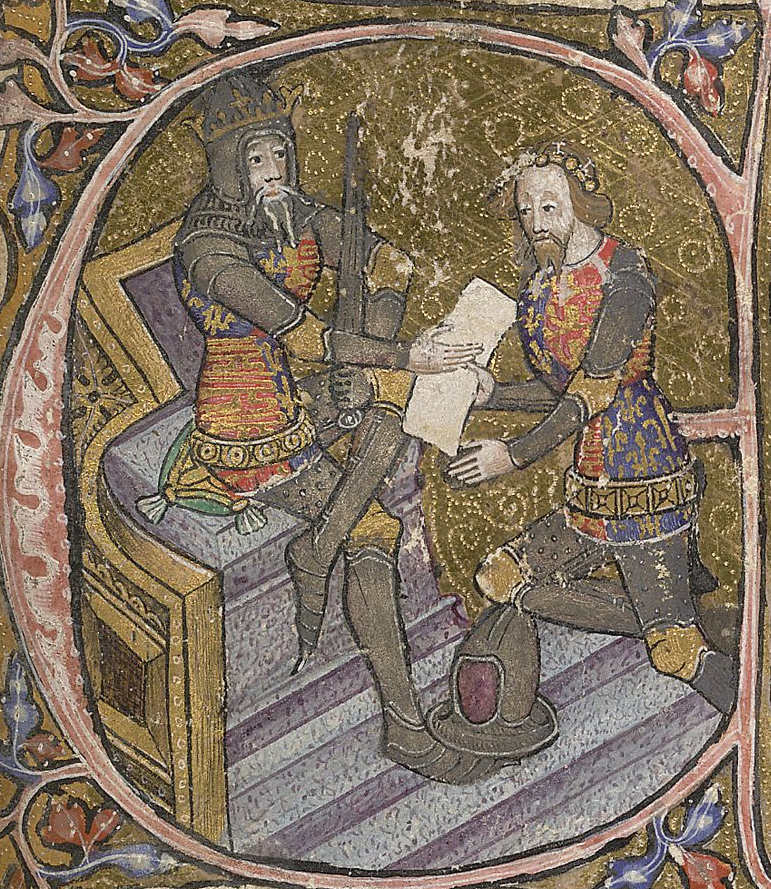

As part of Richard's programme of asserting his authority, he also tried to cultivate the royal image. Unlike any other English king before him, he had himself portrayed inpanel painting

A panel painting is a painting made on a flat panel of wood, either a single piece or a number of pieces joined together. Until canvas became the more popular support medium in the 16th century, panel painting was the normal method, when not paint ...

s of elevated majesty, of which two survive: an over life-size Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an historic, mainly Gothic church in the City of Westminster, London, England, just to the west of the Palace of Westminster. It is one of the United ...

portrait (c. 1390), and the Wilton Diptych

The Wilton Diptych () is a small portable diptych of two hinged panels, painted on both sides, now in the National Gallery, London. It is an extremely rare survival of a late medieval religious panel painting from England.

The diptych was pain ...

(1394–99), a portable work probably intended to accompany Richard on his Irish campaign. It is one of the few surviving English examples of the courtly International Gothic

International Gothic is a period of Gothic art which began in Burgundy, France, and northern Italy in the late 14th and early 15th century. It then spread very widely across Western Europe, hence the name for the period, which was introduced by th ...

style of painting that was developed in the courts of the Continent, especially Prague and Paris. Richard's expenditure on jewellery, rich textiles and metalwork was far higher than on paintings, but as with his illuminated manuscript

An illuminated manuscript is a formally prepared document where the text is often supplemented with flourishes such as borders and miniature illustrations. Often used in the Roman Catholic Church for prayers, liturgical services and psalms, the ...

s, there are hardly any surviving works that can be connected with him, except for a crown, "one of the finest achievements of the Gothic goldsmith", that probably belonged to his wife Anne.

Among Richard's grandest projects in the field of architecture was Westminster Hall

The Palace of Westminster serves as the meeting place for both the House of Commons of the United Kingdom, House of Commons and the House of Lords, the two houses of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Informally known as the Houses of Parli ...

, which was extensively rebuilt during his reign, perhaps spurred on by the completion in 1391 of John of Gaunt's magnificent hall at Kenilworth Castle

Kenilworth Castle is a castle in the town of Kenilworth in Warwickshire, England managed by English Heritage; much of it is still in ruins. The castle was founded during the Norman conquest of England; with development through to the Tudor pe ...

. Fifteen life-size statues of kings were placed in niches on the walls, and the hammer-beam

A hammerbeam roof is a decorative, open timber roof truss typical of English Gothic architecture and has been called "...the most spectacular endeavour of the English Medieval carpenter". They are traditionally timber framed, using short beams pr ...

roof by the royal carpenter Hugh Herland

Hugh Herland (c. 1330 – c. 1411) was a 14th-century medieval English carpenter.Hugh Herland

(c.1330–c.1411 ...

, "the greatest creation of medieval timber architecture", allowed the original three Romanesque aisles to be replaced with a single huge open space, with a dais at the end for Richard to sit in solitary state. The rebuilding had been begun by Henry III in 1245, but had by Richard's time been dormant for over a century.

The court's patronage of literature is especially important, because this was the period in which the English language took shape as a (c.1330–c.1411 ...

literary language

A literary language is the form (register) of a language used in written literature, which can be either a nonstandard dialect or a standardized variety of the language. Literary language sometimes is noticeably different from the spoken langu ...

. There is little evidence to tie Richard directly to patronage of poetry

Poetry (derived from the Greek ''poiesis'', "making"), also called verse, is a form of literature that uses aesthetic and often rhythmic qualities of language − such as phonaesthetics, sound symbolism, and metre − to evoke meanings i ...

, but it was nevertheless within his court that this culture was allowed to thrive. The greatest poet of the age, Geoffrey Chaucer

Geoffrey Chaucer (; – 25 October 1400) was an English poet, author, and civil servant best known for ''The Canterbury Tales''. He has been called the "father of English literature", or, alternatively, the "father of English poetry". He wa ...

, served the king as a diplomat, a customs official and a clerk of The King's Works while producing some of his best-known work. Chaucer was also in the service of John of Gaunt, and wrote ''The Book of the Duchess

''The Book of the Duchess'', also known as ''The Deth of Blaunche'',

''Encyclopædia Britannica'', 1910. Accessed 11 March ...

'' as a eulogy to Gaunt's wife Blanche. Chaucer's colleague and friend ''Encyclopædia Britannica'', 1910. Accessed 11 March ...

John Gower

John Gower (; c. 1330 – October 1408) was an English poet, a contemporary of William Langland and the Pearl Poet, and a personal friend of Geoffrey Chaucer

Geoffrey Chaucer (; – 25 October 1400) was an English poet, author, and civ ...

wrote his ''Confessio Amantis

''Confessio Amantis'' ("The Lover's Confession") is a 33,000-line Middle English poem by John Gower, which uses the confession made by an ageing lover to the chaplain of Venus as a frame story for a collection of shorter narrative poems. Accord ...

'' on a direct commission from Richard, although he later grew disenchanted with the king.

Downfall

Deposition

In June 1399,

In June 1399, Louis I, Duke of Orléans

Louis I of Orléans (13 March 1372 – 23 November 1407) was Duke of Orléans from 1392 to his death. He was also Duke of Touraine (1386–1392), Count of Valois (1386?–1406) Blois (1397–1407), Angoulême (1404–1407 ...

, gained control of the court of the insane Charles VI of France

Charles VI (3 December 136821 October 1422), nicknamed the Beloved (french: le Bien-Aimé) and later the Mad (french: le Fol or ''le Fou''), was King of France from 1380 until his death in 1422. He is known for his mental illness and psychotic ...

. The policy of ''rapprochement'' with the English crown did not suit Louis's political ambitions, and for this reason he found it opportune to allow Henry Bolingbroke to leave for England. With a small group of followers, Bolingbroke landed at Ravenspur

Ravenspurn was a town in the East Riding of Yorkshire, England, which was lost due to coastal erosion, one of more than 30 along the Holderness Coast which have been lost to the North Sea since the 19th century. The town was located close to the ...

in Yorkshire towards the end of June 1399. Men from all over the country soon rallied around him. Meeting with Henry Percy, 1st Earl of Northumberland

Henry Percy, 1st Earl of Northumberland, 4th Baron Percy, titular King of Mann, KG, Lord Marshal (10 November 134120 February 1408) was the son of Henry de Percy, 3rd Baron Percy, and a descendant of Henry III of England. His mother was Mar ...

, who had his own misgivings about the king, Bolingbroke insisted that his only object was to regain his own patrimony. Percy took him at his word and declined to interfere. The king had taken most of his household knights and the loyal members of his nobility with him to Ireland, so Bolingbroke experienced little resistance as he moved south. Keeper of the Realm Edmund, Duke of York

Edmund of Langley, Duke of York (5 June 1341 – 1 August 1402) was the fourth surviving son of King Edward III of England and Philippa of Hainault. Like many medieval English princes, Edmund gained his nickname from his birthplace: Kings Langle ...

, had little choice but to side with Bolingbroke. Meanwhile, Richard was delayed in his return from Ireland and did not land in Wales until 24 July. He made his way to Conwy

Conwy (, ), previously known in English as Conway, is a walled market town, community and the administrative centre of Conwy County Borough in North Wales. The walled town and castle stand on the west bank of the River Conwy, facing Deganwy on ...

, where on 12 August he met with the Earl of Northumberland for negotiations. On 19 August, Richard surrendered to Henry Bolingbroke at Flint Castle

Flint Castle ( cy, Castell y Fflint) in Flint, Flintshire, was the first of a series of castles built during King Edward I's campaign to conquer Wales.

The site was chosen for its strategic position in North East Wales. The castle was only one ...

, promising to abdicate if his life were spared. Both men then returned to London, the indignant king riding all the way behind Henry. On arrival, he was imprisoned in the Tower of London on 1 September.

Henry was by now fully determined to take the throne, but presenting a rationale for this action proved a dilemma. It was argued that Richard, through his tyranny and misgovernment, had rendered himself unworthy of being king. However, Henry was not next in line to the throne; the heir presumptive was Edmund Mortimer, 5th Earl of March

Edmund Mortimer, 5th Earl of March, 7th Earl of Ulster (6 November 139118 January 1425), was an English nobleman and a potential claimant to the throne of England. A great-great-grandson of King Edward III of England, he was heir presumptive to ...

, great-grandson of Edward III's second surviving son, Lionel, Duke of Clarence

Lionel of Antwerp, Duke of Clarence, (; 29 November 133817 October 1368) was the third son, but the second son to survive infancy, of the English king Edward III and Philippa of Hainault. He was named after his birthplace, at Antwerp in the Duch ...

. Bolingbroke's father, John of Gaunt, was Edward's third son to survive to adulthood. The problem was solved by emphasising Henry's descent in a direct ''male'' line, whereas March's descent was through his grandmother, Philippa of Clarence.

According to the official record, read by the Archbishop of Canterbury during an assembly of

According to the official record, read by the Archbishop of Canterbury during an assembly of lords

Lords may refer to:

* The plural of Lord

Places

*Lords Creek, a stream in New Hanover County, North Carolina

* Lord's, English Cricket Ground and home of Marylebone Cricket Club and Middlesex County Cricket Club

People

*Traci Lords (born 1 ...

and commons at Westminster Hall on Tuesday 30 September, Richard gave up his crown willingly and ratified his deposition citing as a reason his own unworthiness as a monarch. On the other hand, the ''Traison et Mort Chronicle'' suggests otherwise. It describes a meeting between Richard and Henry that took place one day before the parliament's session. The king succumbed to blind rage, ordered his own release from the Tower, called his cousin a traitor, demanded to see his wife, and swore revenge, throwing down his bonnet, while Henry refused to do anything without parliamentary approval. When parliament met to discuss Richard's fate, John Trevor, Bishop of St Asaph, read thirty-three articles of deposition that were unanimously accepted by lords and commons. On 1 October 1399, Richard II was formally deposed. On 13 October, the feast day of Edward the Confessor

Edward the Confessor ; la, Eduardus Confessor , ; ( 1003 – 5 January 1066) was one of the last Anglo-Saxon English kings. Usually considered the last king of the House of Wessex, he ruled from 1042 to 1066.

Edward was the son of Æth ...

, Henry Bolingbroke was crowned king.

Death

Henry had agreed to let Richard live after his abdication. This all changed when it was revealed that the earls of Huntingdon, Kent, and Salisbury, and Lord Despenser, and possibly also the Earl of Rutlandall now demoted from the ranks they had been given by Richardwere planning to murder the new king and restore Richard in theEpiphany Rising

The Epiphany Rising was a failed rebellion against King Henry IV of England in early January 1400.

Background

Richard II rewarded those who had supported him against Gloucester and the Lords Appellant with a plethora of new titles. Upon the usur ...

. Although averted, the plot highlighted the danger of allowing Richard to live. He is thought to have been starved to death in captivity in Pontefract Castle

Pontefract (or Pomfret) Castle is a castle ruin in the town of Pontefract, in West Yorkshire, England. King Richard II is thought to have died there. It was the site of a series of famous sieges during the 17th-century English Civil War. ...

on or around 14 February 1400, although there is some question over the date and manner of his death. His body was taken south from Pontefract and displayed in St Paul's Cathedral

St Paul's Cathedral is an Anglican cathedral in London and is the seat of the Bishop of London. The cathedral serves as the mother church of the Diocese of London. It is on Ludgate Hill at the highest point of the City of London and is a Grad ...

on 17 February before burial in King's Langley Priory

King's Langley Priory was a Dominican priory in Kings Langley, Hertfordshire, England. It was located adjacent to the Kings Langley Royal Palace, residence of the Plantagenet English kings.

History