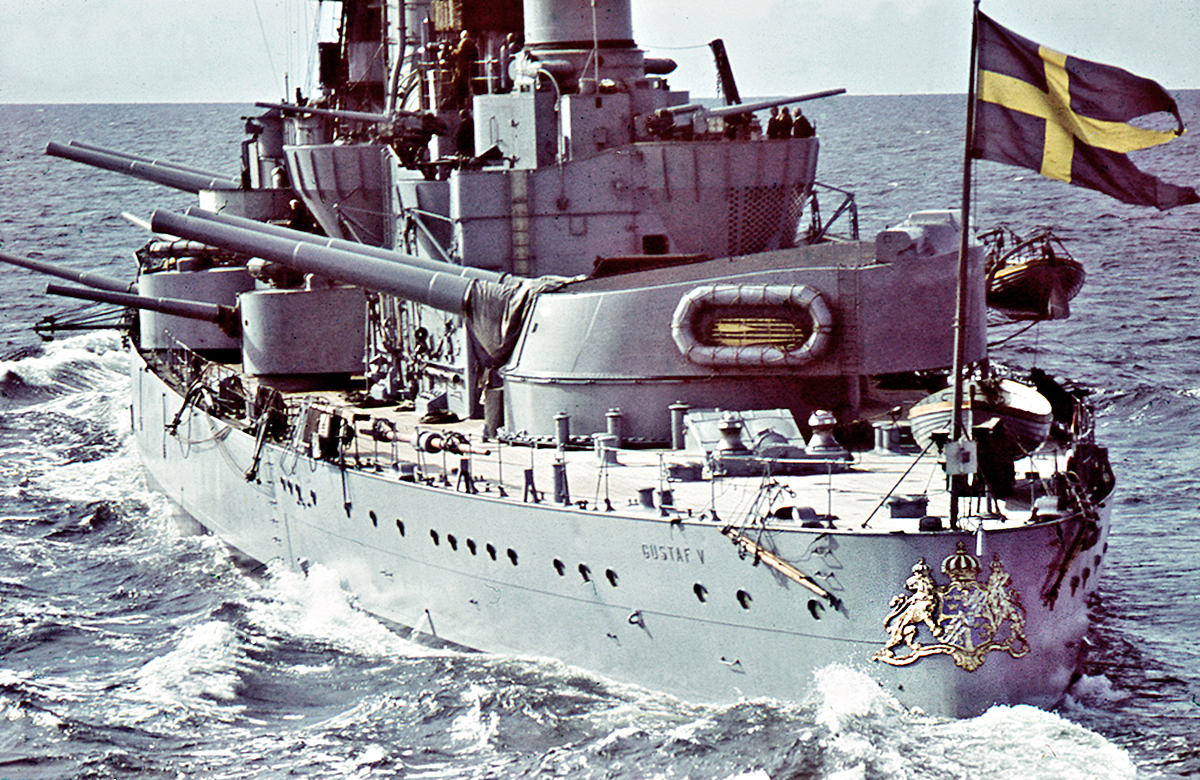

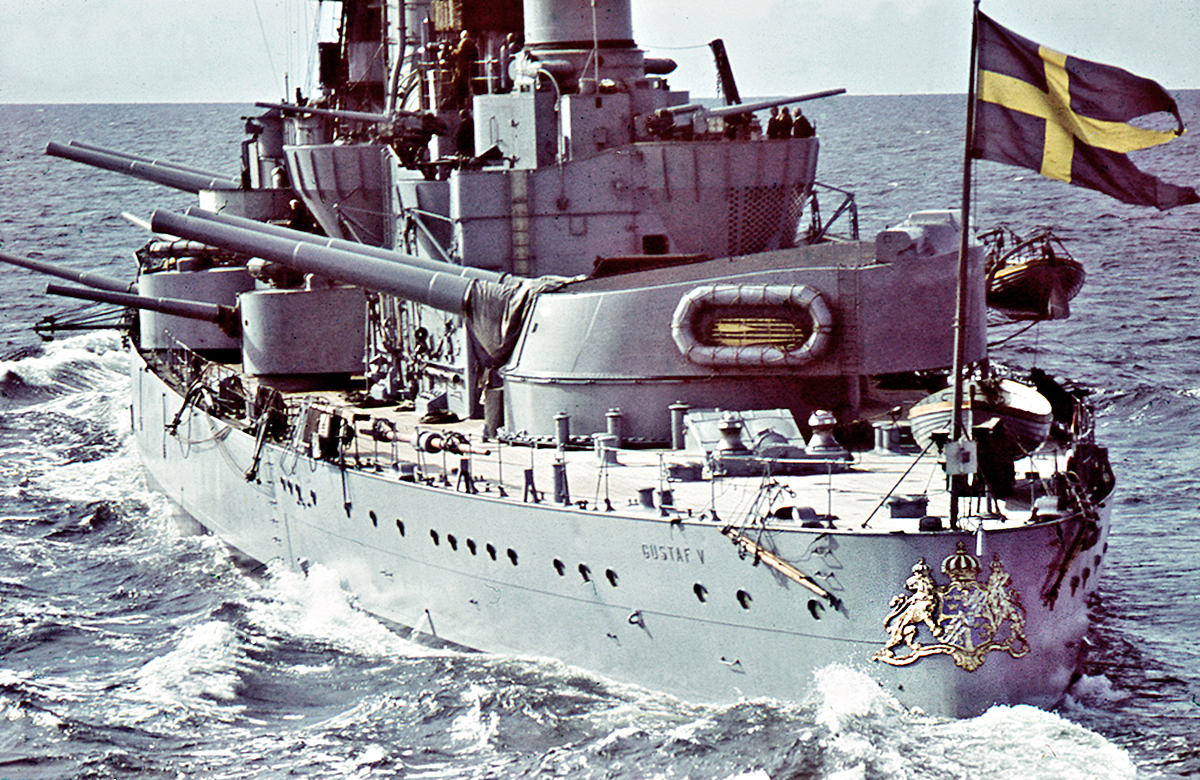

King Gustaf V on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Gustaf V (Oscar Gustaf Adolf; 16 June 1858 – 29 October 1950) was

Gustaf V (Oscar Gustaf Adolf; 16 June 1858 – 29 October 1950) was

The 1917 elections showed a heavy gain for the Liberals and

The 1917 elections showed a heavy gain for the Liberals and

Both the King and his grandson Prince Gustav Adolf socialized with

Both the King and his grandson Prince Gustav Adolf socialized with

Coat of arms Prince héritier Gustave (V).svg, Arms as crown prince from 1872 to 1905

Coat of arms Crown Prince Gustav (V) of Sweden 1.svg, Arms as crown prince from 1905 to 1907

Great coat of arms of Sweden.svg, Greater Coat of Arms of Sweden

Royal Monogram of King Gustaf V of Sweden.svg, Royal Monogram of King Gustaf V of Sweden

Gustaf V profile at the International Tennis Hall of Fame website

* * * , - , - , - , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Gustaf 05 1858 births 1950 deaths 20th-century Swedish monarchs People from Ekerö Municipality Dukes of Värmland House of Bernadotte Swedish Lutherans Swedish male tennis players International Tennis Hall of Fame inductees Uppsala University alumni World War II political leaders Swedish people of French descent Swedish monarchs of German descent Crown Princes of Sweden Burials at Riddarholmen Church Grand Masters of the Order of Charles XIII Knights of the Order of Charles XIII Commanders Grand Cross of the Order of the Sword Commanders Grand Cross of the Order of the Polar Star Grand Crosses of the Order of Vasa Knights of the Order of the Norwegian Lion Recipients of the Cross of Honour of the Order of the Dannebrog Grand Commanders of the Order of the Dannebrog Grand Crosses of the Order of Saint Stephen of Hungary Knights of the Golden Fleece of Spain Honorary Knights Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath Extra Knights Companion of the Garter Collars of the Order of the White Lion Recipients of the Order of the Netherlands Lion 3 3 3 Recipients of the Order of the White Eagle (Russia) Recipients of the Order of St. Anna, 1st class Recipients of the Order of Propitious Clouds Recipients of the Order of the White Star, 1st Class Grand Crosses with Diamonds of the Order of the Sun of Peru Sons of kings Recipients of the Order of the White Eagle (Poland) Grand Crosses of the Order of Saint-Charles

Gustaf V (Oscar Gustaf Adolf; 16 June 1858 – 29 October 1950) was

Gustaf V (Oscar Gustaf Adolf; 16 June 1858 – 29 October 1950) was King of Sweden

The monarchy of Sweden is the monarchical head of state of Sweden,See the #IOG, Instrument of Government, Chapter 1, Article 5. which is a constitutional monarchy, constitutional and hereditary monarchy with a parliamentary system.Parliamentary ...

from 8 December 1907 until his death in 1950. He was the eldest son of King Oscar II of Sweden

Oscar II (Oscar Fredrik; 21 January 1829 – 8 December 1907) was King of Sweden from 1872 until his death in 1907 and King of Norway from 1872 to 1905.

Oscar was the son of King Oscar I and Josephine of Leuchtenberg, Queen Josephine. He inheri ...

and Sophia of Nassau

Sophia of Nassau (Sophia Wilhelmine Marianne Henriette; 9 July 1836 – 30 December 1913) was Queen of Sweden and Norway as the wife of King Oscar II. She was Queen of Sweden for 35 years, longer than anyone before her, and the longest-serv ...

, a half-sister of Adolphe, Grand Duke of Luxembourg

Adolphe (Adolf Wilhelm August Karl Friedrich; 24 July 1817 – 17 November 1905) was Grand Duke of Luxembourg from 23 November 1890 to his death on 17 November 1905. The first grand duke from the House of Nassau-Weilburg, he succeeded King Willia ...

. Reigning from the death of his father Oscar II in 1907 to his own death nearly 43 years later, he holds the record of being the oldest monarch of Sweden and the third-longest rule, after Magnus IV (1319–1364) and Carl XVI Gustaf

Carl XVI Gustaf (Carl Gustaf Folke Hubertus; born 30 April 1946) is King of Sweden. He ascended the throne on the death of his grandfather, Gustaf VI Adolf, on 15 September 1973.

He is the youngest child and only son of Prince Gustaf Adolf, ...

(1973–present). He was also the last Swedish monarch to exercise his royal prerogatives, which largely died with him, although they were formally abolished only with the remaking of the Swedish constitution in 1974. He was the first Swedish king since the High Middle Ages

The High Middle Ages, or High Medieval Period, was the period of European history that lasted from AD 1000 to 1300. The High Middle Ages were preceded by the Early Middle Ages and were followed by the Late Middle Ages, which ended around AD ...

not to have a coronation

A coronation is the act of placement or bestowal of a crown upon a monarch's head. The term also generally refers not only to the physical crowning but to the whole ceremony wherein the act of crowning occurs, along with the presentation of o ...

and so never wore the king's crown, a practice that has continued ever since.

Gustaf's early reign saw the rise of parliamentary rule in Sweden although the leadup to World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

induced his dismissal of Liberal Prime Minister Karl Staaff

Karl Albert Staaff (21 January 1860 – 4 October 1915) was a Swedish liberal politician and lawyer. He was chairman of the Liberal Coalition Party (1907–1915) and served twice as Prime Minister of Sweden (1905–1906 and 1911–1914).

Staaf ...

in 1914, replacing him with his own figurehead, Hjalmar Hammarskjöld, the father of Dag Hammarskjöld

Dag Hjalmar Agne Carl Hammarskjöld ( , ; 29 July 1905 – 18 September 1961) was a Swedish economist and diplomat who served as the second Secretary-General of the United Nations from April 1953 until his death in a plane crash in September 196 ...

, for most of the war. However, after the Liberals and Social Democrats

Social democracy is a political, social, and economic philosophy within socialism that supports political and economic democracy. As a policy regime, it is described by academics as advocating economic and social interventions to promote s ...

secured a parliamentary majority under Staaff's successor, Nils Edén, he allowed Edén to form a new government which ''de facto'' stripped the monarchy of virtually all powers and enacted universal and equal suffrage, including for women, by 1919. Bowing to the principles of parliamentary democracy, he remained a popular figurehead for the remaining 31 years of his rule, although not completely without influence. Gustaf V had pro-German and anti-Communist stances which were outwardly expressed during World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

and the Russian Civil War

{{Infobox military conflict

, conflict = Russian Civil War

, partof = the Russian Revolution and the aftermath of World War I

, image =

, caption = Clockwise from top left:

{{flatlist,

*Soldiers ...

. During World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

, he allegedly urged Per Albin Hansson

Per Albin Hansson (28 October 1885 – 6 October 1946) was a Swedish politician, chairman of the Social Democrats from 1925 and two-time Prime Minister in four governments between 1932 and 1946, governing all that period save for a short-liv ...

's coalition government to accept requests from Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

for logistics support, arguing that refusing might provoke an invasion. His intervention remains controversial.

An avid hunter and sportsman, Gustaf presided over the 1912 Olympic Games

Year 191 ( CXCI) was a common year starting on Friday (link will display the full calendar) of the Julian calendar. At the time, it was known as the Year of the Consulship of Apronianus and Bradua (or, less frequently, year 944 ''Ab urbe condit ...

and chaired the Swedish Association of Sports from 1897 to 1907. Most notably, he represented Sweden (under the alias of ''Mr G.'') as a competitive tennis player, keeping up competitive tennis until his 80s, when his eyesight deteriorated rapidly. He was succeeded by his son, Gustaf VI Adolf

Gustaf VI Adolf (Oscar Fredrik Wilhelm Olaf Gustaf Adolf; 11 November 1882 – 15 September 1973) was King of Sweden from 29 October 1950 until his death in 1973. He was the eldest son of Gustaf V and his wife, Victoria of Baden. Before Gustaf ...

.

Early life

Gustaf V was born inDrottningholm Palace

The Drottningholm Palace ( sv, Drottningholms slott) is the private residence of the Swedish royal family. Drottningholm is near the capital Stockholm. Built on the island Lovön (in Ekerö Municipality of Stockholm County), it is one of S ...

in Ekerö

Ekerö is a locality (urban area) and the seat of Ekerö Municipality in Stockholm County, Sweden, with 11,524 inhabitants in 2017. It is also an alternative name of the island Ekerön, on which the Ekerö urban area is situated.

Sports

The ...

, Stockholm County

Stockholm County ( sv, Stockholms län, link=no ) is a county or '' län'' (in Swedish) on the Baltic Sea coast of Sweden. It borders Uppsala County and Södermanland County. It also borders Mälaren and the Baltic Sea. The city of Stoc ...

, the son of Prince Oscar and Princess Sofia of Nassau. At birth Gustaf was created Duke

Duke is a male title either of a monarch ruling over a duchy, or of a member of Royal family, royalty, or nobility. As rulers, dukes are ranked below emperors, kings, grand princes, grand dukes, and sovereign princes. As royalty or nobility, t ...

of Värmland

Värmland () also known as Wermeland, is a ''landskap'' (historical province) in west-central Sweden. It borders Västergötland, Dalsland, Dalarna, Västmanland, and Närke, and is bounded by Norway in the west. Latin name versions are ...

. Upon his father's accession to the throne in 1872, Gustaf became crown prince of both Sweden and Norway

Norway, officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic country in Northern Europe, the mainland territory of which comprises the western and northernmost portion of the Scandinavian Peninsula. The remote Arctic island of Jan Mayen and t ...

. On 8 December 1907, he succeeded his father on the Swedish throne.

On 20 September 1881 he married Princess Victoria of Baden

Sophie Marie Victoria of Baden (german: Sophie Marie Viktoria; 7 August 1862 – 4 April 1930) was Queen of Sweden from 8 December 1907 until her death in 1930 as the wife of King Gustaf V. She was politically active in a conservative fashion d ...

in Karlsruhe

Karlsruhe ( , , ; South Franconian German, South Franconian: ''Kallsruh'') is the List of cities in Baden-Württemberg by population, third-largest city of the German States of Germany, state (''Land'') of Baden-Württemberg after its capital o ...

, Germany.

Public life

When he ascended the throne, Gustaf V was, at least on paper, a near-autocrat. The1809 Instrument of Government

The 1809 Instrument of Government ( sv, 1809 års regeringsform), adopted on 6 June 1809 by the Riksdag of the Estates and King Charles XIII, was the constitution of the Kingdom of Sweden from 1809 to the end of 1974. It came about as a result ...

made the king both head of state and head of government, and ministers were solely responsible to him. However, his father had been forced to accept a government chosen by the majority in Parliament in 1905. Since then, prime ministers had been ''de facto'' required to have the confidence of the Riksdag to stay in office.

Early in his reign, in 1910, Gustaf V refused to grant clemency to the convicted murderer Johan Alfred Ander, who thus became the last person to be executed in Sweden.

At first, Gustaf V seemed to be willing to accept parliamentary rule. After the Liberals won a massive landslide in 1911, Gustaf appointed Liberal leader Karl Staaff

Karl Albert Staaff (21 January 1860 – 4 October 1915) was a Swedish liberal politician and lawyer. He was chairman of the Liberal Coalition Party (1907–1915) and served twice as Prime Minister of Sweden (1905–1906 and 1911–1914).

Staaf ...

as Prime Minister. However, during the runup to World War I, the elites objected to Staaff's defence policy. In February 1914, a large crowd of farmers gathered at the royal palace and demanded that the country's defences be strengthened. In his reply, the so-called Courtyard Speech

The Courtyard Speech (Swedish: Borggårdstalet) was a speech written by conservative explorer Sven Hedin and Swedish Army lieutenant Carl Bennedich, delivered by King Gustaf V of Sweden to the participants of the Peasant armament support march ( ...

—which was actually written by explorer Sven Hedin

Sven Anders Hedin, KNO1kl RVO,Wennerholm, Eric (1978) ''Sven Hedin – En biografi'', Bonniers, Stockholm (19 February 1865 – 26 November 1952) was a Swedish geographer, topographer, explorer, photographer, travel writer and illustrator ...

, an ardent conservative—Gustaf promised to strengthen the country's defences. Staaff was outraged, telling the king that parliamentary rule called for the Crown to stay out of partisan politics. He was also angered that he had not been consulted in advance of the speech. However, Gustaf retorted that he still had the right to "communicate freely with the Swedish people." The Staaff government resigned in protest, and Gustaf appointed a government of civil servants headed by Hjalmar Hammarskjöld (father of future UN Secretary-General Dag Hammarskjöld

Dag Hjalmar Agne Carl Hammarskjöld ( , ; 29 July 1905 – 18 September 1961) was a Swedish economist and diplomat who served as the second Secretary-General of the United Nations from April 1953 until his death in a plane crash in September 196 ...

) in its place.

The 1917 elections showed a heavy gain for the Liberals and

The 1917 elections showed a heavy gain for the Liberals and Social Democrats

Social democracy is a political, social, and economic philosophy within socialism that supports political and economic democracy. As a policy regime, it is described by academics as advocating economic and social interventions to promote s ...

, who between them held a decisive majority. Despite this, Gustaf initially tried to appoint a Conservative government headed by Johan Widén. However, Widén was unable to attract enough support for a coalition. It was now apparent that Gustaf could no longer appoint a government entirely of his own choosing, nor could he keep a government in office against the will of Parliament. With no choice but to appoint a Liberal as prime minister, he appointed a Liberal-Social Democratic coalition government headed by Staaff's successor as Liberal leader, Nils Edén. The Edén government promptly arrogated most of the king's political powers to itself and enacted numerous reforms, most notably the institution of complete (male and female) universal suffrage in 1918–1919. While Gustaf still formally appointed the ministers, they now had to have the confidence of Parliament. He was now also bound to act on the ministers' advice. Although the provision in the Instrument of Government stating that "the King alone shall govern the realm" remained unchanged, the king was now bound by convention to exercise his powers through the ministers. Thus, for all intents and purposes, the ministers did the actual governing. While ministers were already legally responsible to the Riksdag under the Instrument of government, it was now understood that they were politically responsible to the Riksdag as well. Gustaf accepted his reduced role, and reigned for the rest of his life as a model limited constitutional monarch. Parliamentarianism had become a ''de facto'' reality in Sweden, even if it would not be formalized until 1974, when a new Instrument of Government stripped the monarchy of even nominal political power.

Gustaf V was considered to have German sympathies during World War I. His political stance during the war was highly influenced by his wife, who felt a strong connection to her German homeland. On 18 December 1914, he sponsored a meeting in Malmö

Malmö (, ; da, Malmø ) is the largest city in the Swedish county (län) of Scania (Skåne). It is the third-largest city in Sweden, after Stockholm and Gothenburg, and the sixth-largest city in the Nordic region, with a municipal popula ...

with the other two kings of Scandinavia to demonstrate unity. Another of Gustaf V's objectives was to dispel suspicions that he wanted to bring Sweden into the war on Germany's side.

Although effectively stripped of political power, Gustaf was not completely without influence. In 1938, for instance, he personally summoned the German ambassador to Sweden and told him that if Hitler attacked Czechoslovakia

, rue, Чеськословеньско, , yi, טשעכאסלאוואקיי,

, common_name = Czechoslovakia

, life_span = 1918–19391945–1992

, p1 = Austria-Hungary

, image_p1 ...

over its refusal to give up the Sudetenland

The Sudetenland ( , ; Czech and sk, Sudety) is the historical German name for the northern, southern, and western areas of former Czechoslovakia which were inhabited primarily by Sudeten Germans. These German speakers had predominated in the ...

, it would trigger a world war that Germany would almost certainly lose.William Shirer, ''The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich'' (Touchstone Edition) (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1990) Additionally, his long reign gave him great moral authority Moral authority is authority premised on principles, or fundamental truths, which are independent of written, or positive, laws. As such, moral authority necessitates the existence of and adherence to truth. Because truth does not change, the princi ...

as a symbol of the nation's unity.

Alleged Nazi sympathies

Nazi

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right politics, far-right Totalitarianism, totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hit ...

leaders before World War II, though arguably for diplomatic purposes. Gustaf V attempted to convince Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Germany from 1933 until his death in 1945. He rose to power as the leader of the Nazi Party, becoming the chancellor in 1933 and the ...

during a visit to Berlin to soften his persecution of the Jews, according to historian Jörgen Weibull. He was also noted for appealing to the leader

Leadership, both as a research area and as a practical skill, encompasses the ability of an individual, group or organization to "lead", influence or guide other individuals, teams, or entire organizations. The word "leadership" often gets view ...

of Hungary

Hungary ( hu, Magyarország ) is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning of the Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Croa ...

to save its Jews "in the name of humanity."

When Nazi Germany invaded the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

in June 1941, Gustaf V tried to write a private letter to Hitler thanking him for taking care of the "Bolshevik

The Bolsheviks (russian: Большевики́, from большинство́ ''bol'shinstvó'', 'majority'),; derived from ''bol'shinstvó'' (большинство́), "majority", literally meaning "one of the majority". also known in English ...

pest" and congratulating him on his "already achieved victories". He was stopped from doing so by Prime Minister Per Albin Hansson

Per Albin Hansson (28 October 1885 – 6 October 1946) was a Swedish politician, chairman of the Social Democrats from 1925 and two-time Prime Minister in four governments between 1932 and 1946, governing all that period save for a short-liv ...

.

During the war, Gustav invited Swedish Nazi leader Sven Olov Lindholm to Stockholm Palace

Stockholm Palace or the Royal Palace ( sv, Stockholms slott or ) is the official residence and major royal palace of the Swedish monarch (King Carl XVI Gustaf and Queen Silvia use Drottningholm Palace as their usual residence). Stockholm Pala ...

. The Swedish king had friends in Lindholm's movement.

Midsummer crisis 1941

According to Prime Minister Hansson, during the Midsummer crisis, the King in a private conversation had threatened to abdicate if the government did not approve a German request to transfer a fighting infantry division, the so-called Engelbrecht Division, through Swedish territory from southern Norway to northern Finland in June 1941, aroundMidsummer

Midsummer is a celebration of the season of summer usually held at a date around the summer solstice. It has pagan pre-Christian roots in Europe.

The undivided Christian Church designated June 24 as the feast day of the early Christian marty ...

. The accuracy of the claim is debated, and the King's intention, if he really made that threat, is sometimes alleged to be his desire to avoid conflict with Germany. The event has received considerable attention from Swedish historians and is known as ''midsommarkrisen'', the Midsummer Crisis.

Confirmation of the King's action is contained in German Foreign Policy documents captured at the end of the war. On 25 June 1941, the German Minister in Stockholm sent a "Most Urgent-Top Secret" message to Berlin in which he stated that the King had just informed him that the transit of German troops would be allowed. He added: The King's words conveyed the joyful emotion he felt. He had lived through anxious days and had gone far in giving his personal support to the matter. He added confidentially that he had found it necessary to go so far as to mention his abdication.

Personal life

Gustaf V was thin, and known for his height. He worepince-nez

Pince-nez ( or , plural form same as singular; ) is a style of glasses, popular in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, that are supported without earpieces, by pinching the bridge of the nose. The name comes from French ''pincer'', "to pinch" ...

eyeglasses and sported a pointed mustache for most of his teen years.

Gustaf V was a devoted tennis player, appearing under the pseudonym ''Mr G''. As a player and promoter of the sport, he was elected into the International Tennis Hall of Fame

The International Tennis Hall of Fame is located in Newport, Rhode Island, United States. It honors both players and other contributors to the sport of tennis. The complex, the former Newport Casino, includes a museum, grass tennis courts, an ind ...

in 1980. The King learned the sport during a visit in Britain in 1876 and founded Sweden's first tennis club on his return home. In 1936 he founded the King's Club. During his reign, Gustaf was often seen playing on the Riviera

''Riviera'' () is an Italian word which means "coastline", ultimately derived from Latin , through Ligurian . It came to be applied as a proper name to the coast of Liguria, in the form ''Riviera ligure'', then shortened in English. The two areas ...

. On a visit to Berlin, Gustaf went straight from a meeting with Hitler to a tennis match with the Jewish player Daniel Prenn

Daniel Prenn (7 September 1904 – 3 September 1991) was a Russian Empire-born German, Polish, and British tennis player who was Jewish. He was ranked the world No. 6 for 1932 by A. Wallis Myers, and the European No. 1 by "American Lawn Tennis" ...

. During World War II, he interceded to obtain better treatment for Davis Cup stars Jean Borotra of France and his personal trainer and friend Baron Gottfried von Cramm

Gottfried Alexander Maximilian Walter Kurt Freiherr von Cramm (; 7 July 1909 – 8 November 1976) was a German tennis champion who won the French Open twice and reached the final of a Grand Slam on five other occasions. He was ranked number 2 in ...

of Germany, who had been imprisoned by the Nazi Government on the charge of a homosexual relationship with a Jew.

Haijby affair

Allegations of a love affair between Gustav andKurt Haijby

The Haijby scandal (''Haijbyaffären'') was a political affair in Sweden in the 1950s, involving the conviction and imprisonment of restaurateur Kurt Haijby for the supposed blackmail of King Gustaf V. Haijby claimed that he had a secret homos ...

led to the court paying 170,000 kronor under the threat of the blackmailing Haijby. That led to the so-called Haijby affair and several controversial trials and convictions against Haijby, which spawned considerable controversy about Gustav's alleged homosexuality.

In 2021 the alleged events surrounding the Haijby affair were adapted into a fictional miniseries for Sveriges Television

Sveriges Television AB ("Sweden's Television Stock Company"), shortened to SVT (), is the Swedish national public television broadcaster, funded by a public service tax on personal income set by the Riksdag (national parliament). Prior to 2019 ...

called ''En Kunglig Affär (A Royal Secret)'', directed by Lisa James Larsson Lisa or LISA may refer to:

People

People with the mononym

* Lisa Lisa (born 1967), American actress and lead singer of the Cult Jam

* Lisa (Japanese musician, born 1974), stylized "LISA", Japanese singer and producer

* Lisa Komine (born 1978), J ...

and written by Bengt Braskered.

Death

After a reign of nearly 43 years, King Gustaf V died in Stockholm of flu complications on 29 October 1950. His 67-year-old son Gustav succeeded him asGustav VI Adolf

Gustaf VI Adolf (Oscar Fredrik Wilhelm Olaf Gustaf Adolf; 11 November 1882 – 15 September 1973) was King of Sweden from 29 October 1950 until his death in 1973. He was the eldest son of Gustaf V and his wife, Victoria of Baden. Before Gustaf Ad ...

.

Honours

;National honours * Knight and Commander of the Seraphim, ''16 June 1858'' * Knight of theOrder of Charles XIII

The Royal Order of Charles XIII ( sv, Kungliga Carl XIII:s orden) is a Swedish order of merit, founded by King Charles XIII in 1811.

Membership

The Lord and Master of the Order is the King of Sweden, currently King Carl XVI Gustaf. Membershi ...

, ''16 June 1858''

* Commander Grand Cross of the Sword, ''16 June 1858''

* Commander Grand Cross of the Polar Star, ''16 June 1858''

* Commander Grand Cross of the Order of Vasa

The Royal Order of Vasa () is a Swedish order of chivalry, awarded to citizens of Sweden for service to state and society especially in the fields of agriculture, mining and commerce. It was instituted on 29 May 1772 by King Gustav III. It was ...

, ''12 July 1886''

* Honorary Member of the Johanniter Order

;Foreign military ranks

* : General à la suite

À la suite (, ''in the entourage f') was a military title given to those who were allotted to the army or a particular unit for honour's sake, and entitled to wear a regimental uniform but otherwise had no official position.

In Prussia, these w ...

in the Royal Danish Army

The Royal Danish Army ( da, Hæren, fo, Herurin, kl, Sakkutuut) is the land-based branch of the Danish Defence, together with the Danish Home Guard. For the last decade, the Royal Danish Army has undergone a massive transformation of structure ...

, 1909

*: Admiral à la suite in the Imperial Russian Navy

The Imperial Russian Navy () operated as the navy of the Russian Tsardom and later the Russian Empire from 1696 to 1917. Formally established in 1696, it lasted until dissolved in the wake of the February Revolution of 1917. It developed from ...

, 1909

* : Honorary Admiral in the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by Kingdom of England, English and Kingdom of Scotland, Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were foug ...

, 3 november 1908.

* : General à la suite in the Imperial German Army

The Imperial German Army (1871–1919), officially referred to as the German Army (german: Deutsches Heer), was the unified ground and air force of the German Empire. It was established in 1871 with the political unification of Germany under the ...

, 1909

* : Admiral à la suite in the Imperial German Navy

The Imperial German Navy or the Imperial Navy () was the navy of the German Empire, which existed between 1871 and 1919. It grew out of the small Prussian Navy (from 1867 the North German Federal Navy), which was mainly for coast defence. Wilhel ...

, 1909

* : Admiral à la suite in the Spanish Navy, 1928

* : Honorary commander of the third Life Grenadier Regiment "Königin Elisabeth", 1909

;Foreign honours

Arms

Upon his creation as Duke of Värmland, Gustaf V was granted a coat of arms with the Arms of Värmland in base. Upon his accession to the throne, he assumed the Arms of Dominion of Sweden.Issue

Swedish author Anders Lundebeck (1900–1976) allegedly was an extramarital son of King Gustaf V, an allegation purported by Lundebeck himself and to some extent supported by existing facts.Sir Gustaf von Platen in ''Bakom den gyllene fasaden''Bonniers

Bonnier AB (), also the Bonnier Group, is a privately held Swedish media group of 175 companies operating in 15 countries. It is controlled by the Bonnier family.

Background

The company was founded in 1804 by Gerhard Bonnier in Copenhagen, De ...

p 35

Ancestry

References

External links

Gustaf V profile at the International Tennis Hall of Fame website

* * * , - , - , - , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Gustaf 05 1858 births 1950 deaths 20th-century Swedish monarchs People from Ekerö Municipality Dukes of Värmland House of Bernadotte Swedish Lutherans Swedish male tennis players International Tennis Hall of Fame inductees Uppsala University alumni World War II political leaders Swedish people of French descent Swedish monarchs of German descent Crown Princes of Sweden Burials at Riddarholmen Church Grand Masters of the Order of Charles XIII Knights of the Order of Charles XIII Commanders Grand Cross of the Order of the Sword Commanders Grand Cross of the Order of the Polar Star Grand Crosses of the Order of Vasa Knights of the Order of the Norwegian Lion Recipients of the Cross of Honour of the Order of the Dannebrog Grand Commanders of the Order of the Dannebrog Grand Crosses of the Order of Saint Stephen of Hungary Knights of the Golden Fleece of Spain Honorary Knights Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath Extra Knights Companion of the Garter Collars of the Order of the White Lion Recipients of the Order of the Netherlands Lion 3 3 3 Recipients of the Order of the White Eagle (Russia) Recipients of the Order of St. Anna, 1st class Recipients of the Order of Propitious Clouds Recipients of the Order of the White Star, 1st Class Grand Crosses with Diamonds of the Order of the Sun of Peru Sons of kings Recipients of the Order of the White Eagle (Poland) Grand Crosses of the Order of Saint-Charles