King Edward VI Of England on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Edward VI (12 October 1537 – 6 July 1553) was

Edward was born on 12 October 1537 in his mother's room inside

Edward was born on 12 October 1537 in his mother's room inside

Edward was a healthy baby who suckled strongly from the outset. His father was delighted with him; in May 1538, Henry was observed "dallying with him in his arms ... and so holding him in a window to the sight and great comfort of the people". That September, the Lord Chancellor,

Edward was a healthy baby who suckled strongly from the outset. His father was delighted with him; in May 1538, Henry was observed "dallying with him in his arms ... and so holding him in a window to the sight and great comfort of the people". That September, the Lord Chancellor,  Both Edward's sisters were attentive to their brother and often visited him—on one occasion, Elizabeth gave him a shirt "of her own working". Edward "took special content" in Mary's company, though he disapproved of her taste for foreign dances; "I love you most", he wrote to her in 1546. In 1543, Henry invited his children to spend Christmas with him, signalling his reconciliation with his daughters, whom he had previously illegitimised and disinherited. The following spring, he restored them to their place in the succession with a

Both Edward's sisters were attentive to their brother and often visited him—on one occasion, Elizabeth gave him a shirt "of her own working". Edward "took special content" in Mary's company, though he disapproved of her taste for foreign dances; "I love you most", he wrote to her in 1546. In 1543, Henry invited his children to spend Christmas with him, signalling his reconciliation with his daughters, whom he had previously illegitimised and disinherited. The following spring, he restored them to their place in the succession with a

On 1 July 1543, Henry VIII signed the

On 1 July 1543, Henry VIII signed the

The nine-year-old Edward wrote to his father and stepmother on 10 January 1547 from

The nine-year-old Edward wrote to his father and stepmother on 10 January 1547 from  On the eve of the coronation, Edward progressed on horseback from the Tower to the

On the eve of the coronation, Edward progressed on horseback from the Tower to the

Henry VIII's will named sixteen

Henry VIII's will named sixteen

During 1548, England was subject to social unrest. After April 1549, a series of armed revolts broke out, fuelled by various religious and agrarian grievances. The two most serious rebellions, which required major military intervention to put down, were in Devon and Cornwall and in Norfolk. The first, sometimes called the

During 1548, England was subject to social unrest. After April 1549, a series of armed revolts broke out, fuelled by various religious and agrarian grievances. The two most serious rebellions, which required major military intervention to put down, were in Devon and Cornwall and in Norfolk. The first, sometimes called the

In contrast, Somerset's successor the Earl of Warwick, made

In contrast, Somerset's successor the Earl of Warwick, made  Warwick's war policies were more pragmatic than Somerset's, and they have earned him criticism for weakness. In 1550, he signed a peace treaty with France that agreed to withdrawal from Boulogne and recalled all English garrisons from Scotland. In 1551, Edward was betrothed to

Warwick's war policies were more pragmatic than Somerset's, and they have earned him criticism for weakness. In 1550, he signed a peace treaty with France that agreed to withdrawal from Boulogne and recalled all English garrisons from Scotland. In 1551, Edward was betrothed to

In the matter of religion, the regime of Northumberland followed the same policy as that of Somerset, supporting an increasingly vigorous programme of reform. Although Edward VI's practical influence on government was limited, his intense Protestantism made a reforming administration obligatory; his succession was managed by the reforming faction, who continued in power throughout his reign. The man Edward trusted most, Thomas Cranmer, Archbishop of Canterbury, introduced a series of religious reforms that revolutionised the English church from one that—while rejecting papal supremacy—remained essentially Catholic to one that was institutionally Protestant. The confiscation of church property that had begun under Henry VIII resumed under Edward—notably with the dissolution of the

In the matter of religion, the regime of Northumberland followed the same policy as that of Somerset, supporting an increasingly vigorous programme of reform. Although Edward VI's practical influence on government was limited, his intense Protestantism made a reforming administration obligatory; his succession was managed by the reforming faction, who continued in power throughout his reign. The man Edward trusted most, Thomas Cranmer, Archbishop of Canterbury, introduced a series of religious reforms that revolutionised the English church from one that—while rejecting papal supremacy—remained essentially Catholic to one that was institutionally Protestant. The confiscation of church property that had begun under Henry VIII resumed under Edward—notably with the dissolution of the

In February 1553, Edward VI became ill, and by June, after several improvements and relapses, he was in a hopeless condition. The king's death and the succession of his Catholic half-sister Mary would jeopardise the English Reformation, and Edward's council and officers had many reasons to fear it. Edward himself opposed Mary's succession, not only on religious grounds but also on those of legitimacy and male inheritance, which also applied to Elizabeth. He composed a draft document, headed "My devise for the succession", in which he undertook to change the succession, most probably inspired by his father Henry VIII's precedent. He passed over the claims of his half-sisters and, at last, settled the Crown on his first cousin once removed, the 16-year-old Lady Jane Grey, who on 25 May 1553 had married

In February 1553, Edward VI became ill, and by June, after several improvements and relapses, he was in a hopeless condition. The king's death and the succession of his Catholic half-sister Mary would jeopardise the English Reformation, and Edward's council and officers had many reasons to fear it. Edward himself opposed Mary's succession, not only on religious grounds but also on those of legitimacy and male inheritance, which also applied to Elizabeth. He composed a draft document, headed "My devise for the succession", in which he undertook to change the succession, most probably inspired by his father Henry VIII's precedent. He passed over the claims of his half-sisters and, at last, settled the Crown on his first cousin once removed, the 16-year-old Lady Jane Grey, who on 25 May 1553 had married  In early June, Edward personally supervised the drafting of a clean version of his devise by lawyers, to which he lent his signature "in six several places." Then, on 15 June he summoned high-ranking judges to his sickbed, commanding them on their allegiance "with sharp words and angry countenance" to prepare his devise as letters patent and announced that he would have these passed in Parliament. His next measure was to have leading councillors and lawyers sign a bond in his presence, in which they agreed faithfully to perform Edward's will after his death. A few months later, Chief Justice Edward Montagu recalled that when he and his colleagues had raised legal objections to the devise, Northumberland had threatened them "trembling for anger, and ... further said that he would fight in his shirt with any man in that quarrel". Montagu also overheard a group of lords standing behind him conclude "if they refused to do that, they were traitors". At last, on 21 June, the devise was signed by over a hundred notables, including councillors, peers, archbishops, bishops and sheriffs; many of them later claimed that they had been bullied into doing so by Northumberland, although in the words of Edward's biographer Jennifer Loach, "few of them gave any clear indication of reluctance at the time".

It was now common knowledge that Edward was dying, and foreign diplomats suspected that some scheme to debar Mary was under way. France found the prospect of the emperor's cousin on the English throne disagreeable and engaged in secret talks with Northumberland, indicating support. The diplomats were certain that the overwhelming majority of the English people backed Mary, but nevertheless believed that Queen Jane would be successfully established.

For centuries, the attempt to alter the succession was mostly seen as a one-man plot by the Duke of Northumberland. Since the 1970s, however, many historians have attributed the inception of the "devise" and the insistence on its implementation to the king's initiative.

In early June, Edward personally supervised the drafting of a clean version of his devise by lawyers, to which he lent his signature "in six several places." Then, on 15 June he summoned high-ranking judges to his sickbed, commanding them on their allegiance "with sharp words and angry countenance" to prepare his devise as letters patent and announced that he would have these passed in Parliament. His next measure was to have leading councillors and lawyers sign a bond in his presence, in which they agreed faithfully to perform Edward's will after his death. A few months later, Chief Justice Edward Montagu recalled that when he and his colleagues had raised legal objections to the devise, Northumberland had threatened them "trembling for anger, and ... further said that he would fight in his shirt with any man in that quarrel". Montagu also overheard a group of lords standing behind him conclude "if they refused to do that, they were traitors". At last, on 21 June, the devise was signed by over a hundred notables, including councillors, peers, archbishops, bishops and sheriffs; many of them later claimed that they had been bullied into doing so by Northumberland, although in the words of Edward's biographer Jennifer Loach, "few of them gave any clear indication of reluctance at the time".

It was now common knowledge that Edward was dying, and foreign diplomats suspected that some scheme to debar Mary was under way. France found the prospect of the emperor's cousin on the English throne disagreeable and engaged in secret talks with Northumberland, indicating support. The diplomats were certain that the overwhelming majority of the English people backed Mary, but nevertheless believed that Queen Jane would be successfully established.

For centuries, the attempt to alter the succession was mostly seen as a one-man plot by the Duke of Northumberland. Since the 1970s, however, many historians have attributed the inception of the "devise" and the insistence on its implementation to the king's initiative.

Lady Mary was last seen by Edward in February, and was kept informed about the state of her half-brother's health by Northumberland and through her contacts with the imperial ambassadors. Aware of Edward's imminent death, she left

Lady Mary was last seen by Edward in February, and was kept informed about the state of her half-brother's health by Northumberland and through her contacts with the imperial ambassadors. Aware of Edward's imminent death, she left

Although Edward reigned for only six years and died at the age of 15, his reign made a lasting contribution to the English Reformation and the structure of the Church of England. The last decade of Henry VIII's reign had seen a partial stalling of the Reformation, a drifting back to Catholic values. By contrast, Edward's reign saw radical progress in the Reformation, with the Church transferring from an essentially Catholic liturgy and structure to one that is usually identified as Protestant. In particular, the introduction of the Book of Common Prayer, the Ordinal of 1550 and Cranmer's Forty-two Articles formed the basis for English Church practices that continue to this day. Edward himself fully approved these changes, and though they were the work of reformers such as Thomas Cranmer, Hugh Latimer and Nicholas Ridley, backed by Edward's determinedly evangelical council, the fact of the king's religion was a catalyst in the acceleration of the Reformation during his reign.

Queen Mary's attempts to undo the reforming work of her brother's reign faced major obstacles. Despite her belief in the papal supremacy, she ruled constitutionally as the Supreme Head of the English Church, a contradiction under which she bridled. She found herself entirely unable to restore the vast number of ecclesiastical properties handed over or sold to private landowners. Although she burned a number of leading Protestant churchmen, many reformers either went into exile or remained subversively active in England during her reign, producing a torrent of reforming propaganda that she was unable to stem. Nevertheless, Protestantism was not yet "printed in the stomachs" of the English people, and had Mary lived longer, her Catholic reconstruction might have succeeded, leaving Edward's reign, rather than hers, as a historical aberration.

On Mary's death in 1558, the English Reformation resumed its course, and most of the reforms instituted during Edward's reign were reinstated in the

Although Edward reigned for only six years and died at the age of 15, his reign made a lasting contribution to the English Reformation and the structure of the Church of England. The last decade of Henry VIII's reign had seen a partial stalling of the Reformation, a drifting back to Catholic values. By contrast, Edward's reign saw radical progress in the Reformation, with the Church transferring from an essentially Catholic liturgy and structure to one that is usually identified as Protestant. In particular, the introduction of the Book of Common Prayer, the Ordinal of 1550 and Cranmer's Forty-two Articles formed the basis for English Church practices that continue to this day. Edward himself fully approved these changes, and though they were the work of reformers such as Thomas Cranmer, Hugh Latimer and Nicholas Ridley, backed by Edward's determinedly evangelical council, the fact of the king's religion was a catalyst in the acceleration of the Reformation during his reign.

Queen Mary's attempts to undo the reforming work of her brother's reign faced major obstacles. Despite her belief in the papal supremacy, she ruled constitutionally as the Supreme Head of the English Church, a contradiction under which she bridled. She found herself entirely unable to restore the vast number of ecclesiastical properties handed over or sold to private landowners. Although she burned a number of leading Protestant churchmen, many reformers either went into exile or remained subversively active in England during her reign, producing a torrent of reforming propaganda that she was unable to stem. Nevertheless, Protestantism was not yet "printed in the stomachs" of the English people, and had Mary lived longer, her Catholic reconstruction might have succeeded, leaving Edward's reign, rather than hers, as a historical aberration.

On Mary's death in 1558, the English Reformation resumed its course, and most of the reforms instituted during Edward's reign were reinstated in the

online

Edward VI of England - World History Encyclopedia

* * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Edward 06 Of England Edward VI of England 1537 births 1553 deaths 16th-century English monarchs 16th-century English nobility 16th-century Irish monarchs English people of Welsh descent English pretenders to the French throne Founders of English schools and colleges Princes of Wales Burials at Westminster Abbey Modern child rulers Dukes of Cornwall Christ's Hospital Protestant monarchs 16th-century deaths from tuberculosis English people of the Rough Wooing Jane Seymour House of Tudor Children of Henry VIII Tuberculosis deaths in England Rulers who died as children Sons of kings

King of England

The monarchy of the United Kingdom, commonly referred to as the British monarchy, is the constitutional form of government by which a hereditary sovereign reigns as the head of state of the United Kingdom, the Crown Dependencies (the Bailiw ...

and Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe, north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel (Grea ...

from 28 January 1547 until his death in 1553. He was crowned on 20 February 1547 at the age of nine. Edward was the son of Henry VIII

Henry VIII (28 June 149128 January 1547) was King of England from 22 April 1509 until his death in 1547. Henry is best known for his six marriages, and for his efforts to have his first marriage (to Catherine of Aragon) annulled. His disa ...

and Jane Seymour

Jane Seymour (c. 150824 October 1537) was List of English consorts, Queen of England as the third wife of King Henry VIII of England from their Wives of Henry VIII, marriage on 30 May 1536 until her death the next year. She became queen followi ...

and the first English monarch to be raised as a Protestant

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

. During his reign, the realm was governed by a regency

A regent (from Latin : ruling, governing) is a person appointed to govern a state '' pro tempore'' (Latin: 'for the time being') because the monarch is a minor, absent, incapacitated or unable to discharge the powers and duties of the monarchy ...

council because he never reached maturity. The council was first led by his uncle Edward Seymour, 1st Duke of Somerset

Edward Seymour, 1st Duke of Somerset (150022 January 1552) (also 1st Earl of Hertford, 1st Viscount Beauchamp), also known as Edward Semel, was the eldest surviving brother of Queen Jane Seymour (d. 1537), the third wife of King Henry VI ...

(1547–1549), and then by John Dudley, 1st Earl of Warwick

John Dudley, 1st Duke of Northumberland (1504Loades 2008 – 22 August 1553) was an English general, admiral, and politician, who led the government of the young King Edward VI from 1550 until 1553, and unsuccessfully tried to install Lady Jan ...

(1550–1553), who from 1551 was Duke of Northumberland

Duke of Northumberland is a noble title that has been created three times in English and British history, twice in the Peerage of England and once in the Peerage of Great Britain. The current holder of this title is Ralph Percy, 12th Duke ...

.

Edward's reign was marked by economic problems and social unrest that in 1549 erupted into riot and rebellion. An expensive war with Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a border with England to the southeast and is otherwise surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean to the ...

, at first successful, ended with military withdrawal from Scotland and Boulogne-sur-Mer

Boulogne-sur-Mer (; pcd, Boulonne-su-Mér; nl, Bonen; la, Gesoriacum or ''Bononia''), often called just Boulogne (, ), is a coastal city in Northern France. It is a sub-prefecture of the department of Pas-de-Calais. Boulogne lies on the ...

in exchange for peace. The transformation of the Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Britain ...

into a recognisably Protestant body also occurred under Edward, who took great interest in religious matters. His father, Henry VIII, had severed the link between the Church and Rome, but continued to uphold most Catholic doctrine Catholic doctrine may refer to:

* Catholic theology

** Catholic moral theology

** Catholic Mariology

*Heresy in the Catholic Church

* Catholic social teaching

* Catholic liturgy

*Catholic Church and homosexuality

The Catholic Church broadly ...

and ceremony. It was during Edward's reign that Protestantism was established for the first time in England with reforms that included the abolition of clerical celibacy

Clerical celibacy is the requirement in certain religions that some or all members of the clergy be unmarried. Clerical celibacy also requires abstention from deliberately indulging in sexual thoughts and behavior outside of marriage, because the ...

and the Mass

Mass is an intrinsic property of a body. It was traditionally believed to be related to the quantity of matter in a physical body, until the discovery of the atom and particle physics. It was found that different atoms and different elementar ...

, and the imposition of compulsory services in English.

In February 1553, at age 15, Edward fell ill. When his sickness was discovered to be terminal, he and his council drew up a "Devise for the Succession" to prevent the country's return to Catholicism. Edward named his first cousin once removed, Lady Jane Grey

Lady Jane Grey ( 1537 – 12 February 1554), later known as Lady Jane Dudley (after her marriage) and as the "Nine Days' Queen", was an English noblewoman who claimed the throne of England and Ireland from 10 July until 19 July 1553.

Jane was ...

, as his heir, excluding his half-sisters, Mary

Mary may refer to:

People

* Mary (name), a feminine given name (includes a list of people with the name)

Religious contexts

* New Testament people named Mary, overview article linking to many of those below

* Mary, mother of Jesus, also calle ...

and Elizabeth

Elizabeth or Elisabeth may refer to:

People

* Elizabeth (given name), a female given name (including people with that name)

* Elizabeth (biblical figure), mother of John the Baptist

Ships

* HMS ''Elizabeth'', several ships

* ''Elisabeth'' (sch ...

. This decision was disputed following Edward's death, and Jane was deposed by Mary nine days after becoming queen. Mary, a Catholic, reversed Edward's Protestant reforms during her reign, but Elizabeth restored them in 1559.

Early life

Birth

Edward was born on 12 October 1537 in his mother's room inside

Edward was born on 12 October 1537 in his mother's room inside Hampton Court Palace

Hampton Court Palace is a Grade I listed royal palace in the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames, southwest and upstream of central London on the River Thames. The building of the palace began in 1514 for Cardinal Thomas Wolsey, the chie ...

, in Middlesex

Middlesex (; abbreviation: Middx) is a Historic counties of England, historic county in South East England, southeast England. Its area is almost entirely within the wider urbanised area of London and mostly within the Ceremonial counties of ...

. He was the son of King Henry VIII

Henry VIII (28 June 149128 January 1547) was King of England from 22 April 1509 until his death in 1547. Henry is best known for his six marriages, and for his efforts to have his first marriage (to Catherine of Aragon) annulled. His disa ...

by his third wife, Jane Seymour

Jane Seymour (c. 150824 October 1537) was List of English consorts, Queen of England as the third wife of King Henry VIII of England from their Wives of Henry VIII, marriage on 30 May 1536 until her death the next year. She became queen followi ...

. Throughout the realm, the people greeted the birth of a male heir, "whom we hungered for so long", with joy and relief. ''Te Deum

The "Te Deum" (, ; from its incipit, , ) is a Latin Christian hymn traditionally ascribed to AD 387 authorship, but with antecedents that place it much earlier. It is central to the Ambrosian hymnal, which spread throughout the Latin Chur ...

s'' were sung in churches, bonfires lit, and "their was shott at the Tower that night above two thousand gonnes". Queen Jane, appearing to recover quickly from the birth, sent out personally signed letters announcing the birth of "a Prince, conceived in most lawful matrimony between my Lord the King's Majesty and us". Edward was christened on 15 October, with his half-sisters, the 21-year-old Lady Mary as godmother and the 4-year-old Lady Elizabeth carrying the chrisom

Anciently, a chrisom, or "chrisom-cloth," was the face-cloth, or piece of linen laid over a child's head when they were baptised or christened. Originally, the purpose of the chrisom-cloth was to keep the ''chrism'', a consecrated oil, from accid ...

; and the Garter King of Arms

The Garter Principal King of Arms (also Garter King of Arms or simply Garter) is the senior King of Arms, and the senior Officer of Arms of the College of Arms, the heraldic authority with jurisdiction over England, Wales and Northern Ireland. ...

proclaimed him as Duke of Cornwall

Duke of Cornwall is a title in the Peerage of England, traditionally held by the eldest son of the reigning British monarch, previously the English monarch. The duchy of Cornwall was the first duchy created in England and was established by a ro ...

and Earl of Chester

The Earldom of Chester was one of the most powerful earldoms in medieval England, extending principally over the counties of Cheshire and Flintshire. Since 1301 the title has generally been granted to heirs apparent to the English throne, and a ...

. The queen, however, fell ill on 23 October from presumed postnatal complications, and died the following night. Henry VIII wrote to Francis I of France

Francis I (french: François Ier; frm, Francoys; 12 September 1494 – 31 March 1547) was King of France from 1515 until his death in 1547. He was the son of Charles, Count of Angoulême, and Louise of Savoy. He succeeded his first cousin once ...

that "Divine Providence ... hath mingled my joy with bitterness of the death of her who brought me this happiness".

Upbringing and education

Edward was a healthy baby who suckled strongly from the outset. His father was delighted with him; in May 1538, Henry was observed "dallying with him in his arms ... and so holding him in a window to the sight and great comfort of the people". That September, the Lord Chancellor,

Edward was a healthy baby who suckled strongly from the outset. His father was delighted with him; in May 1538, Henry was observed "dallying with him in his arms ... and so holding him in a window to the sight and great comfort of the people". That September, the Lord Chancellor, Lord Audley

Baron Audley is a title in the Peerage of England first created in 1313, by writ to the Parliament of England, for Sir Nicholas Audley of Heighley Castle, a member of the Anglo-Norman Audley family of Staffordshire.

The third Baron, the last ...

, reported Edward's rapid growth and vigour, and other accounts describe him as a tall and merry child. The tradition that Edward VI was a sickly boy has been challenged by more recent historians. At the age of four, he fell ill with a life-threatening "quartan fever

Quartan fever is one of the four types of malaria which can be contracted by humans.

It is specifically caused by the ''Plasmodium malariae'' species, one of the six species of the protozoan genus ''Plasmodium''. Quartan fever is a form of malaria ...

", but, despite occasional illnesses and poor eyesight, he enjoyed generally good health until the last six months of his life.

Edward was initially placed in the care of Margaret Bryan

Margaret Bryan, Baroness Bryan (c. 1468 – c. 1551/52) was lady governess to the children of King Henry VIII of England, the future monarchs Mary I, Elizabeth I, and Edward VI, as well as the illegitimate Henry FitzRoy.She was also Lady Govern ...

, "lady mistress" of the prince's household. She was succeeded by Blanche Herbert, Lady Troy. Until the age of six, Edward was brought up, as he put it later in his ''Chronicle'', "among the women". The formal royal household established around Edward was, at first, under Sir William Sidney

Sir William Sidney (1482?–1554) was an English courtier under Henry VIII and Edward VI.

Life

He was eldest son of Nicholas Sidney, by Anne, sister of William Brandon (standard-bearer), Sir William Brandon. In 1511 he accompanied Thomas Darcy, ...

, and later Sir Richard Page, stepfather of Edward's aunt Anne

Anne, alternatively spelled Ann, is a form of the Latin female given name Anna. This in turn is a representation of the Hebrew Hannah, which means 'favour' or 'grace'. Related names include Annie.

Anne is sometimes used as a male name in the ...

(the wife of Edward Seymour). Henry demanded exacting standards of security and cleanliness in his son's household, stressing that Edward was "this whole realm's most precious jewel". Visitors described the prince, who was lavishly provided with toys and comforts, including his own troupe of minstrel

A minstrel was an entertainer, initially in medieval Europe. It originally described any type of entertainer such as a musician, juggler, acrobat, singer or fool; later, from the sixteenth century, it came to mean a specialist entertainer who ...

s, as a contented child.

From the age of six, Edward began his formal education under Richard Cox and John Cheke

Sir John Cheke (or Cheek) (16 June 1514 – 13 September 1557) was an English classical scholar and statesman. One of the foremost teachers of his age, and the first Regius Professor of Greek at the University of Cambridge, he played a great pa ...

, concentrating, as he recalled himself, on "learning of tongues, of the scripture, of philosophy, and all liberal sciences". He received tuition from his sister Elizabeth's tutor, Roger Ascham

Roger Ascham (; c. 151530 December 1568)"Ascham, Roger" in ''The New Encyclopædia Britannica''. Chicago: Encyclopædia Britannica Inc., 15th edn., 1992, Vol. 1, p. 617. was an English scholar and didactic writer, famous for his prose style, ...

, and from Jean Belmain

Jean Belmain, also known as John Belmain or John Belleman (died after 1557) was a French Huguenot scholar who served as a French-language teacher to future English monarchs King Edward VI and Queen Elizabeth I at the court of their father, Henry VI ...

, learning French, Spanish and Italian. In addition, he is known to have studied geometry

Geometry (; ) is, with arithmetic, one of the oldest branches of mathematics. It is concerned with properties of space such as the distance, shape, size, and relative position of figures. A mathematician who works in the field of geometry is c ...

and learned to play musical instruments, including the lute

A lute ( or ) is any plucked string instrument with a neck and a deep round back enclosing a hollow cavity, usually with a sound hole or opening in the body. It may be either fretted or unfretted.

More specifically, the term "lute" can ref ...

and the virginals

The virginals (or virginal) is a keyboard instrument of the harpsichord family. It was popular in Europe during the late Renaissance and early Baroque periods.

Description

A virginal is a smaller and simpler rectangular or polygonal form of ...

. He collected globes and maps and, according to coinage historian C. E. Challis, developed a grasp of monetary affairs that indicated a high intelligence. Edward's religious education is assumed to have favoured the reforming agenda. His religious establishment was probably chosen by Archbishop Thomas Cranmer, a leading reformer. Both Cox and Cheke were "reformed" Catholics or Erasmians and later became Marian exiles

The Marian exiles were English Protestantism, Protestants who fled to Continental Europe during the 1553–1558 reign of the Catholic Church, Catholic monarchs Queen Mary I and Philip II of Spain, King Philip.Christina Hallowell Garrett (1938) ''M ...

. By 1549, Edward had written a treatise

A treatise is a formal and systematic written discourse on some subject, generally longer and treating it in greater depth than an essay, and more concerned with investigating or exposing the principles of the subject and its conclusions."Treat ...

on the pope as Antichrist

In Christian eschatology, the Antichrist refers to people prophesied by the Bible to oppose Jesus Christ and substitute themselves in Christ's place before the Second Coming. The term Antichrist (including one plural form) 1 John ; . 2 John . ...

and was making informed notes on theological controversies. Many aspects of Edward's religion were essentially Catholic in his early years, including celebration of the mass

Mass is an intrinsic property of a body. It was traditionally believed to be related to the quantity of matter in a physical body, until the discovery of the atom and particle physics. It was found that different atoms and different elementar ...

and reverence for images and relics of the saints.

Both Edward's sisters were attentive to their brother and often visited him—on one occasion, Elizabeth gave him a shirt "of her own working". Edward "took special content" in Mary's company, though he disapproved of her taste for foreign dances; "I love you most", he wrote to her in 1546. In 1543, Henry invited his children to spend Christmas with him, signalling his reconciliation with his daughters, whom he had previously illegitimised and disinherited. The following spring, he restored them to their place in the succession with a

Both Edward's sisters were attentive to their brother and often visited him—on one occasion, Elizabeth gave him a shirt "of her own working". Edward "took special content" in Mary's company, though he disapproved of her taste for foreign dances; "I love you most", he wrote to her in 1546. In 1543, Henry invited his children to spend Christmas with him, signalling his reconciliation with his daughters, whom he had previously illegitimised and disinherited. The following spring, he restored them to their place in the succession with a Third Succession Act

The Third Succession Act of King Henry VIII's reign, passed by the Parliament of England in July 1543, returned his daughters Mary and Elizabeth to the line of the succession behind their half-brother Edward. Born in 1537, Edward was the son of ...

, which also provided for a regency council during Edward's minority. This unaccustomed family harmony may have owed much to the influence of Henry's new wife, Catherine Parr

Catherine Parr (sometimes alternatively spelled Katherine, Katheryn, Kateryn, or Katharine; 1512 – 5 September 1548) was Queen of England and Ireland as the last of the six wives of King Henry VIII from their marriage on 12 July 1543 until ...

, of whom Edward soon became fond. He called her his "most dear mother" and in September 1546 wrote to her: "I received so many benefits from you that my mind can hardly grasp them."

Other children were brought to play with Edward, including the granddaughter of his chamberlain, Sir William Sidney, who in adulthood recalled the prince as "a marvellous sweet child, of very mild and generous condition". Edward was educated with sons of nobles, "appointed to attend upon him" in what was a form of miniature court. Among these, Barnaby Fitzpatrick

Sir Barnaby Fitzpatrick, 2nd Baron Upper Ossory (1535? – 11 September 1581), was educated at the court of Henry VIII of England with Edward, Prince of Wales. While he was in France, he corresponded regularly with King Edward VI. He was active ...

, son of an Irish peer, became a close and lasting friend. Edward was more devoted to his schoolwork than his classmates and seems to have outshone them, motivated to do his "duty" and compete with his sister Elizabeth's academic prowess. Edward's surroundings and possessions were regally splendid: his rooms were hung with costly Flemish tapestries

Tapestry is a form of textile art, traditionally woven by hand on a loom. Tapestry is weft-faced weaving, in which all the warp threads are hidden in the completed work, unlike most woven textiles, where both the warp and the weft threads may ...

, and his clothes, books and cutlery were encrusted with precious jewels and gold. Like his father, Edward was fascinated by military arts, and many of his portraits show him wearing a gold dagger with a jewelled hilt, in imitation of Henry. Edward's ''Chronicle'' enthusiastically details English military campaigns against Scotland and France, and adventures such as John Dudley

John Dudley, 1st Duke of Northumberland (1504Loades 2008 – 22 August 1553) was an English general, admiral, and politician, who led the government of the young King Edward VI from 1550 until 1553, and unsuccessfully tried to install Lady Ja ...

's near capture at Musselburgh

Musselburgh (; sco, Musselburrae; gd, Baile nam Feusgan) is the largest settlement in East Lothian, Scotland, on the coast of the Firth of Forth, east of Edinburgh city centre. It has a population of .

History

The name Musselburgh is Ol ...

in 1547.

"The Rough Wooing"

On 1 July 1543, Henry VIII signed the

On 1 July 1543, Henry VIII signed the Treaty of Greenwich

The Treaty of Greenwich (also known as the Treaties of Greenwich) contained two agreements both signed on 1 July 1543 in Greenwich between representatives of England and Scotland. The accord, overall, entailed a plan developed by Henry VIII of En ...

with the Scots, sealing the peace with Edward's betrothal

An engagement or betrothal is the period of time between the declaration of acceptance of a marriage proposal and the marriage itself (which is typically but not always commenced with a wedding). During this period, a couple is said to be ''fi ...

to the seven-month-old Mary, Queen of Scots

Mary, Queen of Scots (8 December 1542 – 8 February 1587), also known as Mary Stuart or Mary I of Scotland, was Queen of Scotland from 14 December 1542 until her forced abdication in 1567.

The only surviving legitimate child of James V of Scot ...

. The Scots were in a weak bargaining position after their defeat at the Battle of Solway Moss

The Battle of Solway Moss took place on Solway Moss near the River Esk on the English side of the Anglo-Scottish border in November 1542 between English and Scottish forces.

The Scottish King James V had refused to break from the Catholic Chu ...

in November 1542, and Henry, seeking to unite the two realms, stipulated that Mary be handed over to him to be brought up in England. When the Scots repudiated the treaty in December 1543 and renewed their alliance with France, Henry was enraged. In April 1544, he ordered Edward's uncle, Edward Seymour, Earl of Hertford, to invade Scotland and "put all to fire and sword, burn Edinburgh town, so razed and defaced when you have sacked and gotten what ye can of it, as there may remain forever a perpetual memory of the vengeance of God lightened upon hem

A hem in sewing is a garment finishing method, where the edge of a piece of cloth is folded and sewn to prevent unravelling of the fabric and to adjust the length of the piece in garments, such as at the end of the sleeve or the bottom of the ga ...

for their falsehood and disloyalty". Seymour responded with the most savage campaign ever launched by the English against the Scots. The war, which continued into Edward's reign, has become known as "the Rough Wooing

The Rough Wooing (December 1543 – March 1551), also known as the Eight Years' War, was part of the Anglo-Scottish Wars of the 16th century. Following its break with the Roman Catholic Church, England attacked Scotland, partly to break the ...

".

Accession

Hertford

Hertford ( ) is the county town of Hertfordshire, England, and is also a civil parish in the East Hertfordshire district of the county. The parish had a population of 26,783 at the 2011 census.

The town grew around a ford on the River Lea, ne ...

thanking them for his new year's gift of their portraits from life. By 28 January, Henry VIII was dead. Those close to the throne, led by Edward Seymour and William Paget William Paget may refer to:

*William Paget, 1st Baron Paget (1506–1563), English statesman

* William Paget, 4th Baron Paget de Beaudesert (1572–1629), English colonist

*William Paget, 5th Baron Paget (1609–1678), English peer

*William Paget, ...

, agreed to delay the announcement of the king's death until arrangements had been made for a smooth succession. Seymour and Sir Anthony Browne, the Master of the Horse

Master of the Horse is an official position in several European nations. It was more common when most countries in Europe were monarchies, and is of varying prominence today.

(Ancient Rome)

The original Master of the Horse ( la, Magister Equitu ...

, rode to collect Edward from Hertford and brought him to Enfield

Enfield may refer to:

Places Australia

* Enfield, New South Wales

* Enfield, South Australia

** Electoral district of Enfield, a state electoral district in South Australia, corresponding to the suburb

** Enfield High School (South Australia)

...

, where Lady Elizabeth was living. He and Elizabeth were then told of their father's death and heard a reading of his will.

Lord Chancellor Thomas Wriothesley

Sir Thomas Wriothesley ( ; died 24 November 1534) was a long serving officer of arms at the College of Arms in London. He was the son of Garter King of Arms, John Writhe, and he succeeded his father in this office.

Personal life

Wriothesley was ...

announced Henry's death to Parliament

In modern politics, and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

on 31 January, and general proclamations of Edward's succession were ordered. The new king was taken to the Tower of London

The Tower of London, officially His Majesty's Royal Palace and Fortress of the Tower of London, is a historic castle on the north bank of the River Thames in central London. It lies within the London Borough of Tower Hamlets, which is separa ...

, where he was welcomed with "great shot of ordnance in all places there about, as well out of the Tower as out of the ships". The following day, the nobles of the realm made their obeisance

A salute is usually a formal hand gesture or other action used to display respect in military situations. Salutes are primarily associated with the military and law enforcement, but many civilian organizations, such as Girl Guides, Boy Sco ...

to Edward at the Tower, and Seymour was announced as Protector

Protector(s) or The Protector(s) may refer to:

Roles and titles

* Protector (title), a title or part of various historical titles of heads of state and others in authority

** Lord Protector, a title that has been used in British constitutional l ...

. Henry VIII was buried at Windsor on 16 February, in the same tomb as Jane Seymour, as he had wished.

Edward VI was crowned at Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an historic, mainly Gothic church in the City of Westminster, London, England, just to the west of the Palace of Westminster. It is one of the United ...

on Sunday 20 February. The ceremonies were shortened, because of the "tedious length of the same which should weary and be hurtsome peradventure to the King's majesty, being yet of tender age", and also because the Reformation had rendered some of them inappropriate.

On the eve of the coronation, Edward progressed on horseback from the Tower to the

On the eve of the coronation, Edward progressed on horseback from the Tower to the Palace of Westminster

The Palace of Westminster serves as the meeting place for both the House of Commons of the United Kingdom, House of Commons and the House of Lords, the two houses of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Informally known as the Houses of Parli ...

through thronging crowds and pageants, many based on the pageants for a previous boy king, Henry VI. He laughed at a Spanish tightrope walker

Tightrope walking, also called funambulism, is the skill of walking along a thin wire or rope. It has a long tradition in various countries and is commonly associated with the circus. Other skills similar to tightrope walking include slack rope ...

who "tumbled and played many pretty toys" outside St Paul's Cathedral

St Paul's Cathedral is an Anglican cathedral in London and is the seat of the Bishop of London. The cathedral serves as the mother church of the Diocese of London. It is on Ludgate Hill at the highest point of the City of London and is a Grad ...

.

At the coronation service, Cranmer affirmed the royal supremacy

The Acts of Supremacy are two acts passed by the Parliament of England in the 16th century that established the English monarchs as the head of the Church of England; two similar laws were passed by the Parliament of Ireland establishing the Eng ...

and called Edward a second Josiah

Josiah ( or ) or Yoshiyahu; la, Iosias was the 16th king of Judah (–609 BCE) who, according to the Hebrew Bible, instituted major religious reforms by removing official worship of gods other than Yahweh. Josiah is credited by most biblical s ...

, urging him to continue the reformation of the Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Britain ...

, "the tyranny of the Bishops of Rome banished from your subjects, and images removed". After the service, Edward presided at a banquet in Westminster Hall

The Palace of Westminster serves as the meeting place for both the House of Commons of the United Kingdom, House of Commons and the House of Lords, the two houses of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Informally known as the Houses of Parli ...

, where, he recalled in his ''Chronicle'', he dined with his crown on his head.

Somerset Protectorate

Council of regency

Henry VIII's will named sixteen

Henry VIII's will named sixteen executor

An executor is someone who is responsible for executing, or following through on, an assigned task or duty. The feminine form, executrix, may sometimes be used.

Overview

An executor is a legal term referring to a person named by the maker of a ...

s, who were to act as Edward's council until he reached the age of eighteen. These executors were supplemented by twelve men "of counsail" who would assist the executors when called on. The final state of Henry VIII's will has been the subject of controversy. Some historians suggest that those close to the king manipulated either him or the will itself to ensure a share-out of power to their benefit, both material and religious. In this reading, the composition of the Privy Chamber

A privy chamber was the private apartment of a royal residence in England.

The Gentlemen of the Privy Chamber were noble-born servants to the Crown who would wait and attend on the King in private, as well as during various court activities, f ...

shifted towards the end of 1546 in favour of the reforming faction

Faction or factionalism may refer to:

Politics

* Political faction, a group of people with a common political purpose

* Free and Independent Faction, a Romanian political party

* Faction (''Planescape''), a political faction in the game ''Planes ...

. In addition, two leading conservative Privy Councillors were removed from the centre of power.

Stephen Gardiner

Stephen Gardiner (27 July 1483 – 12 November 1555) was an English Catholic bishop and politician during the English Reformation period who served as Lord Chancellor during the reign of Queen Mary I and King Philip.

Early life

Gardiner was b ...

was refused access to Henry during his last months. Thomas Howard, 3rd Duke of Norfolk

Thomas Howard, 3rd Duke of Norfolk, (1473 – 25 August 1554) was a prominent English politician and nobleman of the Tudor era. He was an uncle of two of the wives of King Henry VIII, Anne Boleyn and Catherine Howard, both of whom were beheade ...

, found himself accused of treason

Treason is the crime of attacking a state authority to which one owes allegiance. This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to overthrow its government, spying on its military, its diplo ...

; the day before the king's death his vast estates were seized, making them available for redistribution, and he spent the whole of Edward's reign in the Tower of London. Other historians have argued that Gardiner's exclusion was based on non-religious matters, that Norfolk was not noticeably conservative in religion, that conservatives remained on the council, and that the radicalism of such men as Sir Anthony Denny

Sir Anthony Denny (16 January 1501 – 10 September 1549) was Groom of the Stool to King Henry VIII of England, thus his closest courtier and confidant. He was the most prominent member of the Privy chamber in King Henry's last years, havin ...

, who controlled the dry stamp that replicated the king's signature, is debatable.

Whatever the case, Henry's death was followed by a lavish hand-out of lands and honours to the new power group. The will contained an "unfulfilled gifts" clause, added at the last minute, which allowed the executors to freely distribute lands and honours to themselves and the court, particularly to Edward Seymour, 1st Earl of Hertford, the new king's uncle who became Lord Protector of the Realm, Governor of the King's Person and Duke of Somerset

Duke is a male title either of a monarch ruling over a duchy, or of a member of royalty, or nobility. As rulers, dukes are ranked below emperors, kings, grand princes, grand dukes, and sovereign princes. As royalty or nobility, they are rank ...

.

In fact, Henry VIII's will did not provide for the appointment of a Protector. It entrusted the government of the realm during his son's minority to a regency council that would rule collectively, by majority decision, with "like and equal charge". Nevertheless, a few days after Henry's death, on 4 February, the executors chose to invest almost regal power in the Duke of Somerset. Thirteen out of the sixteen (the others being absent) agreed to his appointment as Protector, which they justified as their joint decision "by virtue of the authority" of Henry's will. Somerset may have done a deal with some of the executors, who almost all received hand-outs. He is known to have done so with William Paget, private secretary to Henry VIII, and to have secured the support of Sir Anthony Browne of the Privy Chamber.

Somerset's appointment was in keeping with historical precedent, and his eligibility for the role was reinforced by his military successes in Scotland and France. In March 1547, he secured letters patent

Letters patent ( la, litterae patentes) ( always in the plural) are a type of legal instrument in the form of a published written order issued by a monarch, president or other head of state, generally granting an office, right, monopoly, titl ...

from King Edward granting him the almost monarchical right to appoint members to the Privy Council himself and to consult them only when he wished. In the words of historian Geoffrey Elton, "from that moment his autocratic system was complete". He proceeded to rule largely by proclamation

A proclamation (Lat. ''proclamare'', to make public by announcement) is an official declaration issued by a person of authority to make certain announcements known. Proclamations are currently used within the governing framework of some nations ...

, calling on the Privy Council to do little more than rubber-stamp his decisions.

Somerset's takeover of power was smooth and efficient. The imperial ambassador, François van der Delft

François van der Delft (c. 1500 – 21 June 1550), was Imperial ambassador to the court of Henry VIII of England from 1545 to 1547 and ambassador to the court of Edward VI of England from 1547 to 1550.

Van der Delft came to England ...

, reported that he "governs everything absolutely", with Paget operating as his secretary, though he predicted trouble from John Dudley, Viscount Lisle, who had recently been raised to Earl of Warwick

Earl of Warwick is one of the most prestigious titles in the peerages of the United Kingdom. The title has been created four times in English history, and the name refers to Warwick Castle and the town of Warwick.

Overview

The first creation c ...

in the share-out of honours. In fact, in the early weeks of his Protectorate, Somerset was challenged only by the Chancellor, Thomas Wriothesley, whom the Earldom of Southampton had evidently failed to buy off, and by his own brother. Wriothesley, a religious conservative, objected to Somerset's assumption of monarchical power over the council. He then found himself abruptly dismissed from the chancellorship on charges of selling off some of his offices to delegates.

Thomas Seymour

Somerset faced less manageable opposition from his younger brother Thomas, who has been described as a "worm in the bud". As King Edward's uncle, Thomas Seymour demanded the governorship of the king's person and a greater share of power. Somerset tried to buy his brother off with abaron

Baron is a rank of nobility or title of honour, often hereditary, in various European countries, either current or historical. The female equivalent is baroness. Typically, the title denotes an aristocrat who ranks higher than a lord or knig ...

y, an appointment to the Lord Admiralship, and a seat on the Privy Council—but Thomas was bent on scheming for power. He began smuggling pocket money to King Edward, telling him that Somerset held the purse strings too tight, making him a "beggarly king". He also urged the king to throw off the Protector within two years and "bear rule as other kings do"; but Edward, schooled to defer to the council, failed to co-operate. In the spring of 1547, using Edward's support to circumvent Somerset's opposition, Thomas Seymour secretly married Henry VIII's widow Catherine Parr, whose Protestant household included the 11-year-old Lady Jane Grey

Lady Jane Grey ( 1537 – 12 February 1554), later known as Lady Jane Dudley (after her marriage) and as the "Nine Days' Queen", was an English noblewoman who claimed the throne of England and Ireland from 10 July until 19 July 1553.

Jane was ...

and the 13-year-old Lady Elizabeth.

In summer 1548, a pregnant Catherine Parr discovered Thomas Seymour embracing Lady Elizabeth. As a result, Elizabeth was removed from Parr's household and transferred to Sir Anthony Denny's. That September, Parr died shortly after childbirth, and Seymour promptly resumed his attentions to Elizabeth by letter, planning to marry her. Elizabeth was receptive, but, like Edward, unready to agree to anything unless permitted by the council. In January 1549, the council had Thomas Seymour arrested on various charges, including embezzlement

Embezzlement is a crime that consists of withholding assets for the purpose of conversion of such assets, by one or more persons to whom the assets were entrusted, either to be held or to be used for specific purposes. Embezzlement is a type ...

at the Bristol mint

MiNT is Now TOS (MiNT) is a free software alternative operating system kernel for the Atari ST system and its successors. It is a multi-tasking alternative to TOS and MagiC. Together with the free system components fVDI device drivers, XaAES g ...

. King Edward, whom Seymour was accused of planning to marry to Lady Jane Grey, himself testified about the pocket money. Lack of clear evidence for treason ruled out a trial, so Seymour was condemned instead by an act of attainder

A bill of attainder (also known as an act of attainder or writ of attainder or bill of penalties) is an act of a legislature declaring a person, or a group of people, guilty of some crime, and punishing them, often without a trial. As with attai ...

and beheaded on 20 March 1549.

War

Somerset's only undoubted skill was as a soldier, which he had proven on expeditions to Scotland and in the defence ofBoulogne-sur-Mer

Boulogne-sur-Mer (; pcd, Boulonne-su-Mér; nl, Bonen; la, Gesoriacum or ''Bononia''), often called just Boulogne (, ), is a coastal city in Northern France. It is a sub-prefecture of the department of Pas-de-Calais. Boulogne lies on the ...

in 1546. From the first, his main interest as Protector was the war against Scotland. After a crushing victory at the Battle of Pinkie

The Battle of Pinkie, also known as the Battle of Pinkie Cleugh ( , ), took place on 10 September 1547 on the banks of the River Esk near Musselburgh, Scotland. The last pitched battle between Scotland and England before the Union of the Cro ...

in September 1547, he set up a network of garrisons in Scotland, stretching as far north as Dundee

Dundee (; sco, Dundee; gd, Dùn Dè or ) is Scotland's fourth-largest city and the 51st-most-populous built-up area in the United Kingdom. The mid-year population estimate for 2016 was , giving Dundee a population density of 2,478/km2 or ...

. His initial successes, however, were followed by a loss of direction, as his aim of uniting the realms through conquest became increasingly unrealistic. The Scots allied with France, who sent reinforcements for the defence of Edinburgh in 1548. The Queen of Scots was moved to France, where she was betrothed to the Dauphin. The cost of maintaining the Protector's massive armies and his permanent garrisons in Scotland also placed an unsustainable burden on the royal finances. A French attack on Boulogne in August 1549 at last forced Somerset to begin a withdrawal from Scotland.

Rebellion

During 1548, England was subject to social unrest. After April 1549, a series of armed revolts broke out, fuelled by various religious and agrarian grievances. The two most serious rebellions, which required major military intervention to put down, were in Devon and Cornwall and in Norfolk. The first, sometimes called the

During 1548, England was subject to social unrest. After April 1549, a series of armed revolts broke out, fuelled by various religious and agrarian grievances. The two most serious rebellions, which required major military intervention to put down, were in Devon and Cornwall and in Norfolk. The first, sometimes called the Prayer Book Rebellion

The Prayer Book Rebellion or Western Rising was a popular revolt in Cornwall and Devon in 1549. In that year, the ''Book of Common Prayer'', presenting the theology of the English Reformation, was introduced. The change was widely unpopular, ...

, arose from the imposition of Protestantism, and the second

''The Second'' is the second studio album by Canadian-American rock band Steppenwolf, released in October 1968 on ABC Dunhill Records. The album contains one of Steppenwolf's most famous songs, " Magic Carpet Ride". The background of the orig ...

, led by a tradesman called Robert Kett

Robert Kett (c. 1492 – 7 December 1549) was the leader of Kett's Rebellion.

Kett was the fourth son of Thomas Kett, of Forncett, Norfolk and his wife Margery. He is thought to have been a tanner, but he certainly held the manor of Wymondha ...

, mainly from the encroachment of landlords on common grazing ground. A complex aspect of the social unrest was that the protesters believed they were acting legitimately against enclosing

Enclosure or Inclosure is a term, used in English landownership, that refers to the appropriation of "waste" or "common land" enclosing it and by doing so depriving commoners of their rights of access and privilege. Agreements to enclose land ...

landlords with the Protector's support, convinced that the landlords were the lawbreakers.

The same justification for outbreaks of unrest was voiced throughout the country, not only in Norfolk and the west. The origin of the popular view of Somerset as sympathetic to the rebel cause lies partly in his series of sometimes liberal, often contradictory, proclamations, and partly in the uncoordinated activities of the commissions he sent out in 1548 and 1549 to investigate grievances about loss of tillage, encroachment of large sheep flocks on common land

Common land is land owned by a person or collectively by a number of persons, over which other persons have certain common rights, such as to allow their livestock to graze upon it, to collect Wood fuel, wood, or to cut turf for fuel.

A person ...

, and similar issues. Somerset's commissions were led by an evangelical MP called John Hales John Hales may refer to:

*John Hales (theologian) (1584–1656), English theologian

* John Hales (bishop of Exeter) from 1455 to 1456

*John Hales (bishop of Coventry and Lichfield) (died 1490) from 1459 to 1490

* John Hales (died 1540), MP for Cante ...

, whose socially liberal rhetoric linked the issue of enclosure with Reformation theology and the notion of a godly commonwealth

A commonwealth is a traditional English term for a political community founded for the common good. Historically, it has been synonymous with "republic". The noun "commonwealth", meaning "public welfare, general good or advantage", dates from the ...

. Local groups often assumed that the findings of these commissions entitled them to act against offending landlords themselves. King Edward wrote in his ''Chronicle'' that the 1549 risings began "because certain commissions were sent down to pluck down enclosures".

Whatever the popular view of Somerset, the disastrous events of 1549 were taken as evidence of a colossal failure of government, and the council laid the responsibility at the Protector's door. In July 1549, Paget wrote to Somerset: "Every man of the council have misliked your proceedings ... would to God, that, at the first stir you had followed the matter hotly, and caused justice to be ministered in solemn fashion to the terror of others ...".

Fall of Somerset

The sequence of events that led to Somerset's removal from power has often been called a ''coup d'état

A coup d'état (; French for 'stroke of state'), also known as a coup or overthrow, is a seizure and removal of a government and its powers. Typically, it is an illegal seizure of power by a political faction, politician, cult, rebel group, m ...

''. By 1 October 1549, Somerset had been alerted that his rule faced a serious threat. He issued a proclamation calling for assistance, took possession of the king's person, and withdrew for safety to the fortified Windsor Castle

Windsor Castle is a royal residence at Windsor in the English county of Berkshire. It is strongly associated with the English and succeeding British royal family, and embodies almost a millennium of architectural history.

The original cast ...

, where Edward wrote, "Me thinks I am in prison". Meanwhile, a united council published details of Somerset's government mismanagement. They made clear that the Protector's power came from them, not from Henry VIII's will. On 11 October, the council had Somerset arrested and brought the king to Richmond Palace

Richmond Palace was a royal residence on the River Thames in England which stood in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Situated in what was then rural Surrey, it lay upstream and on the opposite bank from the Palace of Westminster, which w ...

. Edward summarised the charges against Somerset in his ''Chronicle'': "ambition, vainglory, entering into rash wars in mine youth, negligent looking on Newhaven, enriching himself of my treasure, following his own opinion, and doing all by his own authority, etc." In February 1550, John Dudley, Earl of Warwick

John Dudley, 1st Duke of Northumberland (1504Loades 2008 – 22 August 1553) was an English general, admiral, and politician, who led the government of the young King Edward VI from 1550 until 1553, and unsuccessfully tried to install Lady Ja ...

, emerged as the leader of the council and, in effect, as Somerset's successor. Although Somerset was released from the Tower and restored to the council, he was executed for felony

A felony is traditionally considered a crime of high seriousness, whereas a misdemeanor is regarded as less serious. The term "felony" originated from English common law (from the French medieval word "félonie") to describe an offense that resu ...

in January 1552 after scheming to overthrow Dudley's regime. Edward noted his uncle's death in his ''Chronicle'': "the duke of Somerset had his head cut off upon Tower Hill between eight and nine o'clock in the morning".

Historians contrast the efficiency of Somerset's takeover of power, in which they detect the organising skills of allies such as Paget, the "master of practices", with the subsequent ineptitude of his rule. By autumn 1549, his costly wars had lost momentum, the crown faced financial ruin, and riots and rebellions had broken out around the country. Until recent decades, Somerset's reputation with historians was high, in view of his many proclamations that appeared to back the common people against a rapacious landowning class. More recently, however, he has often been portrayed as an arrogant and aloof ruler, lacking in political and administrative skills.

Northumberland's leadership

In contrast, Somerset's successor the Earl of Warwick, made

In contrast, Somerset's successor the Earl of Warwick, made Duke of Northumberland

Duke of Northumberland is a noble title that has been created three times in English and British history, twice in the Peerage of England and once in the Peerage of Great Britain. The current holder of this title is Ralph Percy, 12th Duke ...

in 1551, was once regarded by historians merely as a grasping schemer who cynically elevated and enriched himself at the expense of the crown. Since the 1970s, the administrative and economic achievements of his regime have been recognised, and he has been credited with restoring the authority of the royal council and returning the government to an even keel after the disasters of Somerset's protectorate.

The Earl of Warwick's rival for leadership of the new regime was Thomas Wriothesley, 1st Earl of Southampton, whose conservative supporters had allied with Warwick's followers to create a unanimous council which they and observers, such as the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V

Charles V, french: Charles Quint, it, Carlo V, nl, Karel V, ca, Carles V, la, Carolus V (24 February 1500 – 21 September 1558) was Holy Roman Emperor and Archduke of Austria from 1519 to 1556, King of Spain ( Castile and Aragon) fro ...

's ambassador, expected to reverse Somerset's policy of religious reform. Warwick, on the other hand, pinned his hopes on the king's strong Protestantism and, claiming that Edward was old enough to rule in person, moved himself and his people closer to the king, taking control of the Privy Chamber. Paget, accepting a barony, joined Warwick when he realised that a conservative policy would not bring the emperor onto the English side over Boulogne. Southampton prepared a case for executing Somerset, aiming to discredit Warwick through Somerset's statements that he had done all with Warwick's co-operation. As a counter-move, Warwick convinced Parliament to free Somerset, which it did on 14 January 1550. Warwick then had Southampton and his followers purged from the council after winning the support of council members in return for titles, and was made Lord President of the Council

The lord president of the Council is the presiding officer of the Privy Council of the United Kingdom and the fourth of the Great Officers of State (United Kingdom), Great Officers of State, ranking below the Lord High Treasurer but above the ...

and great master of the king's household. Although not called a Protector, he was now clearly the head of the government.

As Edward was growing up, he was able to understand more and more government business. However, his actual involvement in decisions has long been a matter of debate, and during the 20th century, historians have presented the whole gamut of possibilities, "balanc ngan articulate puppet against a mature, precocious, and essentially adult king", in the words of Stephen Alford. A special "Counsel for the Estate" was created when Edward was fourteen. He chose the members himself. In the weekly meetings with this council, Edward was "to hear the debating of things of most importance". A major point of contact with the king was the Privy Chamber, and there Edward worked closely with William Cecil and William Petre

Sir William Petre (c. 1505 – 1572) (pronounced ''Peter'') was Secretary of State to three successive Tudor monarchs, namely Kings Henry VIII, Edward VI and Queen Mary I. He also deputised for the Secretary of State to Elizabeth I.

Educate ...

, the principal secretaries. The king's greatest influence was in matters of religion, where the council followed the strongly Protestant policy that Edward favoured.

The Duke of Northumberland's mode of operation was very different from Somerset's. Careful to make sure he always commanded a majority of councillors, he encouraged a working council and used it to legitimise his authority. Lacking Somerset's blood-relationship with the king, he added members to the council from his own faction in order to control it. He also added members of his family to the royal household. He saw that to achieve personal dominance, he needed total procedural control of the council. In the words of historian John Guy, "Like Somerset, he became quasi-king; the difference was that he managed the bureaucracy on the pretence that Edward had assumed full sovereignty, whereas Somerset had asserted the right to near-sovereignty as Protector".

Warwick's war policies were more pragmatic than Somerset's, and they have earned him criticism for weakness. In 1550, he signed a peace treaty with France that agreed to withdrawal from Boulogne and recalled all English garrisons from Scotland. In 1551, Edward was betrothed to

Warwick's war policies were more pragmatic than Somerset's, and they have earned him criticism for weakness. In 1550, he signed a peace treaty with France that agreed to withdrawal from Boulogne and recalled all English garrisons from Scotland. In 1551, Edward was betrothed to Elisabeth of Valois

Elisabeth of France or Elisabeth of Valois ( es, Isabel de Valois; french: Élisabeth de France) (2 April 1545 – 3 October 1568) was Queen of Spain as the third spouse of Philip II of Spain. She was the eldest daughter of Henry II of France ...

, King Henry II's daughter, and was made a Knight of Saint Michael. Warwick realised that England could no longer support the cost of wars. At home, he took measures to police local unrest. To forestall future rebellions, he kept permanent representatives of the crown in the localities, including lords lieutenant, who commanded military forces and reported back to central government.

Working with William Paulet and Walter Mildmay

Sir Walter Mildmay (bef. 1523 – 31 May 1589) was a statesman who served as Chancellor of the Exchequer to Queen Elizabeth I, and founded Emmanuel College, Cambridge.

Origins

He was born at Moulsham in Essex, the fourth and youngest son of Th ...

, Warwick tackled the disastrous state of the kingdom's finances. However, his regime first succumbed to the temptations of a quick profit by further debasing

A debasement of coinage is the practice of lowering the intrinsic value of coins, especially when used in connection with commodity money, such as gold or silver coins. A coin is said to be debased if the quantity of gold, silver, copper or nick ...

the coinage. The economic disaster that resulted caused Warwick to hand the initiative to the expert Thomas Gresham

Sir Thomas Gresham the Elder (; c. 151921 November 1579), was an English merchant and financier who acted on behalf of King Edward VI (1547–1553) and Edward's half-sisters, queens Mary I (1553–1558) and Elizabeth I (1558–1603). In 1565 G ...

. By 1552, confidence in the coinage was restored, prices fell and trade at last improved. Though a full economic recovery was not achieved until Elizabeth's reign, its origins lay in the Duke of Northumberland's policies. The regime also cracked down on widespread embezzlement of government finances, and carried out a thorough review of revenue collection practices, which has been called "one of the more remarkable achievements of Tudor administration".

Reformation

In the matter of religion, the regime of Northumberland followed the same policy as that of Somerset, supporting an increasingly vigorous programme of reform. Although Edward VI's practical influence on government was limited, his intense Protestantism made a reforming administration obligatory; his succession was managed by the reforming faction, who continued in power throughout his reign. The man Edward trusted most, Thomas Cranmer, Archbishop of Canterbury, introduced a series of religious reforms that revolutionised the English church from one that—while rejecting papal supremacy—remained essentially Catholic to one that was institutionally Protestant. The confiscation of church property that had begun under Henry VIII resumed under Edward—notably with the dissolution of the

In the matter of religion, the regime of Northumberland followed the same policy as that of Somerset, supporting an increasingly vigorous programme of reform. Although Edward VI's practical influence on government was limited, his intense Protestantism made a reforming administration obligatory; his succession was managed by the reforming faction, who continued in power throughout his reign. The man Edward trusted most, Thomas Cranmer, Archbishop of Canterbury, introduced a series of religious reforms that revolutionised the English church from one that—while rejecting papal supremacy—remained essentially Catholic to one that was institutionally Protestant. The confiscation of church property that had begun under Henry VIII resumed under Edward—notably with the dissolution of the chantries

A chantry is an ecclesiastical term that may have either of two related meanings:

# a chantry service, a Christian liturgy of prayers for the dead, which historically was an obiit, or

# a chantry chapel, a building on private land, or an area in ...

—to the great monetary advantage of the crown and the new owners of the seized property. Church reform was therefore as much a political as a religious policy under Edward VI. By the end of his reign, the church had been financially ruined, with much of the property of the bishops transferred into lay hands.

The religious convictions of both Somerset and Northumberland have proved elusive for historians, who are divided on the sincerity of their Protestantism. There is less doubt, however, about the religious fervour of King Edward, who was said to have read twelve chapters of scripture daily and enjoyed sermons, and was commemorated by John Foxe

John Foxe (1516/1517 – 18 April 1587), an English historian and martyrologist, was the author of '' Actes and Monuments'' (otherwise ''Foxe's Book of Martyrs''), telling of Christian martyrs throughout Western history, but particularly the su ...

as a "godly imp". Edward was depicted during his life and afterwards as a new Josiah, the biblical king who destroyed the idols of Baal

Baal (), or Baal,; phn, , baʿl; hbo, , baʿal, ). ( ''baʿal'') was a title and honorific meaning "owner", "lord" in the Northwest Semitic languages spoken in the Levant during Ancient Near East, antiquity. From its use among people, it cam ...

. He could be prig

A prig () is a person who shows an inordinately zealous approach to matters of form and propriety—especially where the prig has the ability to show superior knowledge to those who do not know the protocol in question. They see little need to con ...

gish in his anti-Catholicism and once asked Catherine Parr to persuade Lady Mary "to attend no longer to foreign dances and merriments which do not become a most Christian princess". Edward's biographer Jennifer Loach cautions, however, against accepting too readily the pious image of Edward handed down by the reformers, as in John Foxe's influential ''Acts and Monuments

The ''Actes and Monuments'' (full title: ''Actes and Monuments of these Latter and Perillous Days, Touching Matters of the Church''), popularly known as Foxe's Book of Martyrs, is a work of Protestant history and martyrology by Protestant Engl ...

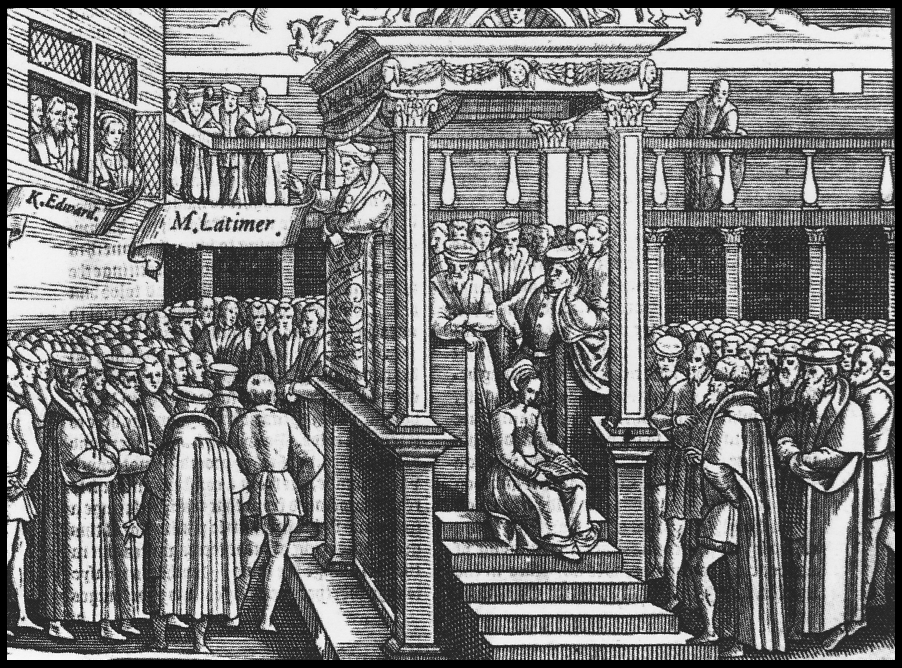

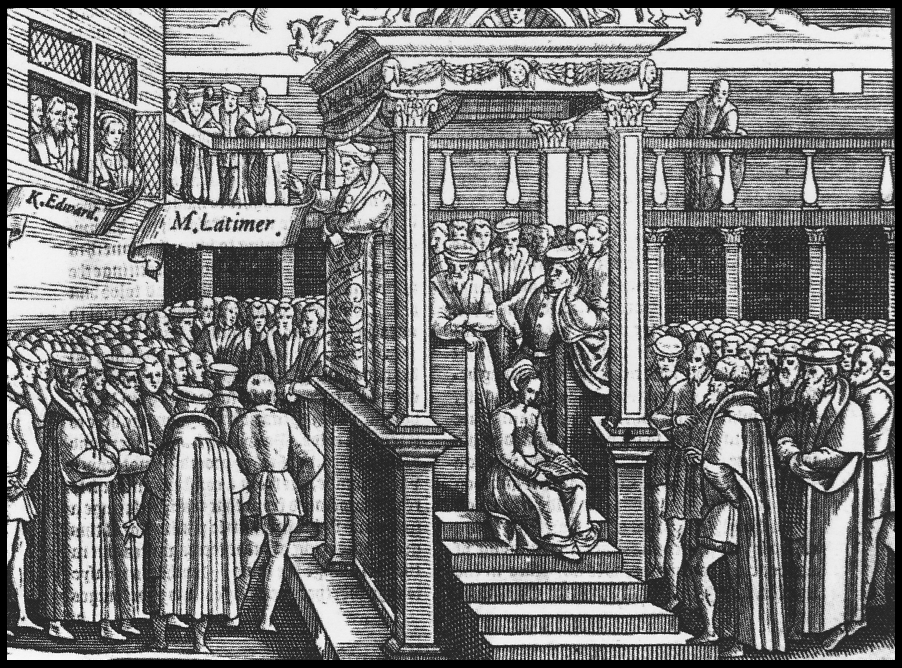

'', where a woodcut depicts the young king listening to a sermon by Hugh Latimer

Hugh Latimer ( – 16 October 1555) was a Fellow of Clare College, Cambridge, and Bishop of Worcester during the Reformation, and later Church of England chaplain to King Edward VI. In 1555 under the Catholic Queen Mary I he was burned at the s ...

. In the early part of his life, Edward conformed to the prevailing Catholic practices, including attendance at mass, but he became convinced, under the influence of Cranmer and the reformers among his tutors and courtiers, that "true" religion should be imposed in England.

The English Reformation

The English Reformation took place in 16th-century England when the Church of England broke away from the authority of the pope and the Catholic Church. These events were part of the wider European Protestant Reformation, a religious and poli ...

advanced under pressure from two directions: from the traditionalists on the one hand and the zealots

The Zealots were a political movement in 1st-century Second Temple Judaism which sought to incite the people of Judea Province to rebel against the Roman Empire and expel it from the Holy Land by force of arms, most notably during the First Jew ...