King Edward III (retouched).jpg on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

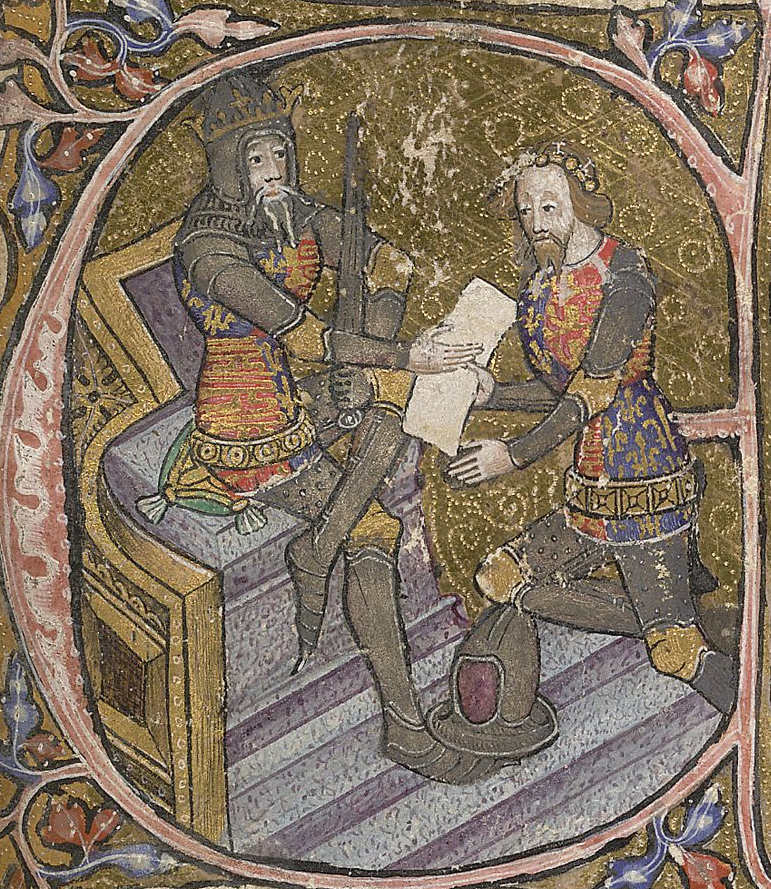

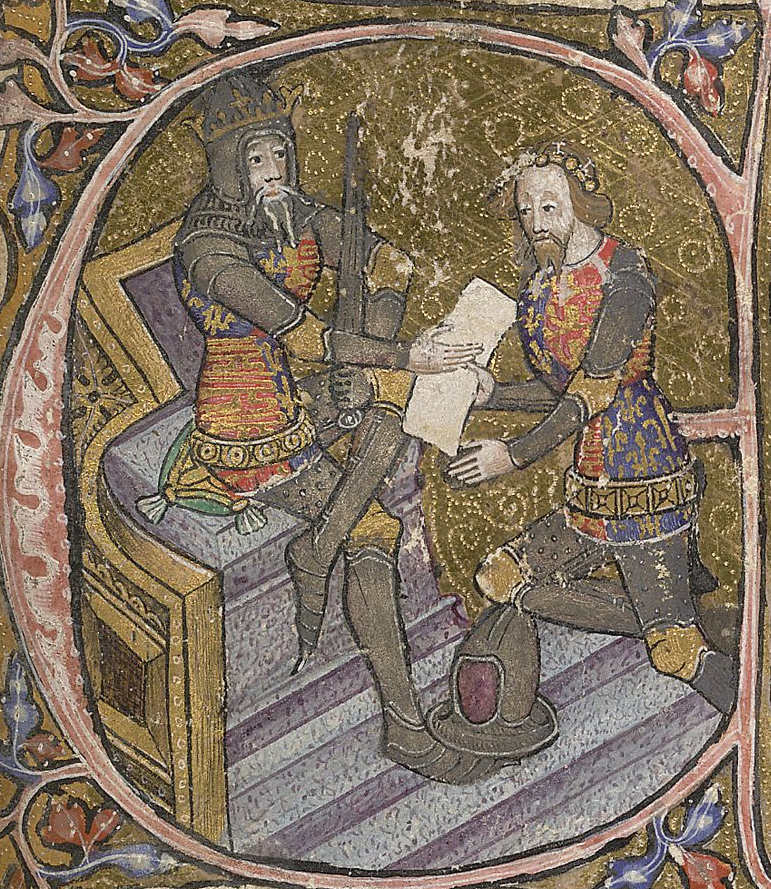

Edward III (13 November 1312 – 21 June 1377), also known as Edward of Windsor before his accession, was

King of England

The monarchy of the United Kingdom, commonly referred to as the British monarchy, is the constitutional form of government by which a hereditary sovereign reigns as the head of state of the United Kingdom, the Crown Dependencies (the Bailiw ...

and Lord of Ireland

The Lordship of Ireland ( ga, Tiarnas na hÉireann), sometimes referred to retroactively as Norman Ireland, was the part of Ireland ruled by the King of England (styled as "Lord of Ireland") and controlled by loyal Anglo-Norman lords between ...

from January 1327 until his death in 1377. He is noted for his military success and for restoring royal authority after the disastrous and unorthodox reign of his father, Edward II. EdwardIII transformed the Kingdom of England into one of the most formidable military powers in Europe. His fifty-year reign was one of the longest in English history, and saw vital developments in legislation and government, in particular the evolution of the English Parliament, as well as the ravages of the Black Death

The Black Death (also known as the Pestilence, the Great Mortality or the Plague) was a bubonic plague pandemic occurring in Western Eurasia and North Africa from 1346 to 1353. It is the most fatal pandemic recorded in human history, causi ...

. He outlived his eldest son, Edward the Black Prince, and the throne passed to his grandson, Richard II

Richard II (6 January 1367 – ), also known as Richard of Bordeaux, was King of England from 1377 until he was deposed in 1399. He was the son of Edward the Black Prince, Prince of Wales, and Joan, Countess of Kent. Richard's father died ...

.

Edward was crowned at age fourteen after his father was deposed by his mother, Isabella of France, and her lover Roger Mortimer. At age seventeen he led a successful coup d'état against Mortimer, the '' de facto'' ruler of the country, and began his personal reign. After a successful campaign in Scotland he declared himself rightful heir to the French throne in 1337. This started what became known as the Hundred Years' War

The Hundred Years' War (; 1337–1453) was a series of armed conflicts between the kingdoms of Kingdom of England, England and Kingdom of France, France during the Late Middle Ages. It originated from disputed claims to the French Crown, ...

. Following some initial setbacks, this first phase of the war went exceptionally well for England; victories at Crécy and Poitiers

Poitiers (, , , ; Poitevin: ''Poetàe'') is a city on the River Clain in west-central France. It is a commune and the capital of the Vienne department and the historical centre of Poitou. In 2017 it had a population of 88,291. Its agglomerat ...

led to the highly favourable Treaty of Brétigny, in which England made territorial gains, and Edward renounced his claim to the French throne. This phase would become known as the Edwardian War. Edward's later years were marked by international failure and domestic strife, largely as a result of his inactivity and poor health.

Edward was a temperamental man but capable of unusual clemency. He was in many ways a conventional king whose main interest was warfare. Admired in his own time and for centuries after, he was denounced as an irresponsible adventurer by later Whig historians such as Bishop William Stubbs; modern historians credit him with some significant achievements.

Early life (1312–1327)

Edward was born at Windsor Castle on 13 November 1312, and was often called Edward of Windsor in his early years. The reign of his father, Edward II, was a particularly problematic period of English history. One source of contention was the king's inactivity, and repeated failure, in the ongoing war with Scotland. Another controversial issue was the king's exclusivepatronage

Patronage is the support, encouragement, privilege, or financial aid that an organization or individual bestows on another. In the history of art, arts patronage refers to the support that kings, popes, and the wealthy have provided to artists su ...

of a small group of royal favourites. The birth of a male heir in 1312 temporarily improved EdwardII's position in relation to the baronial opposition. To bolster further the independent prestige of the young prince, the king had him created Earl of Chester at only twelve days of age.

In 1325, Edward II was faced with a demand from his brother-in-law, Charles IV of France, to perform homage

Homage (Old English) or Hommage (French) may refer to:

History

*Homage (feudal) /ˈhɒmɪdʒ/, the medieval oath of allegiance

*Commendation ceremony, medieval homage ceremony Arts

*Homage (arts) /oʊˈmɑʒ/, an allusion or imitation by one arti ...

for the English Duchy of Aquitaine. Edward was reluctant to leave the country, as discontent was once again brewing domestically, particularly over his relationship with the favourite Hugh Despenser the Younger. Instead, he had his son Edward created Duke of Aquitaine in his place and sent him to France to perform the homage. The young Edward was accompanied by his mother Isabella

Isabella may refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Isabella (given name), including a list of people and fictional characters

* Isabella (surname), including a list of people

Places

United States

* Isabella, Alabama, an unincorpora ...

, who was the sister of King Charles, and was meant to negotiate a peace treaty with the French. While in France, Isabella conspired with the exiled Roger Mortimer to have Edward deposed. To build up diplomatic and military support for the venture, Isabella had her son engaged to the twelve-year-old Philippa of Hainault. An invasion of England was launched and EdwardII's forces deserted him completely. Isabella and Mortimer summoned a parliament, and the king was forced to relinquish the throne to his son, who was proclaimed king in London on 25 January 1327. The new king was crowned as EdwardIII at Westminster Abbey on 1February at the age of 14.

Early reign (1327–1337)

Mortimer's rule and fall

It was not long before the new reign also met with other problems caused by the central position at court of Mortimer, who was now the de facto ruler of England. Mortimer used his power to acquire noble estates and titles, and his unpopularity grew with the humiliating defeat by the Scots at theBattle of Stanhope Park

The Weardale campaign, part of the First War of Scottish Independence, occurred during July and August 1327 in Weardale, England. A Scottish force under James, Lord of Douglas, and the earls of Moray and Mar faced an English army commande ...

in the county of Durham, and the ensuing Treaty of Edinburgh–Northampton, signed with the Scots in 1328. Also the young king came into conflict with his guardian. Mortimer knew his position in relation to the king was precarious and subjected Edward to disrespect. The tension increased after Edward and Philippa, who had married at York Minster on 24 January 1328, had a son, Edward of Woodstock

Edward of Woodstock, known to history as the Black Prince (15 June 1330 – 8 June 1376), was the eldest son of King Edward III of England, and the List of heirs to the English throne, heir apparent to the English throne. He died before his fat ...

, on 15 June 1330. Eventually, the king decided to take direct action against Mortimer. Aided by his close companion William Montagu, 3rd Baron Montagu

William Montagu, alias de Montacute, 1st Earl of Salisbury, 3rd Baron Montagu, King of Man (1301 – 30 January 1344) was an English nobleman and loyal servant of King Edward III of England, Edward III.

The son of William Montagu, 2nd Baron Mo ...

, and a small number of other trusted men, Edward took Mortimer by surprise at Nottingham Castle on 19 October 1330. Mortimer was executed and EdwardIII's personal reign began.

War in Scotland

Edward III was not content with the peace agreement made in his name, but the renewal of the war with Scotland originated in private, rather than royal initiative. A group of Englishmagnate

The magnate term, from the late Latin ''magnas'', a great man, itself from Latin ''magnus'', "great", means a man from the higher nobility, a man who belongs to the high office-holders, or a man in a high social position, by birth, wealth or ot ...

s known as The Disinherited, who had lost land in Scotland by the peace accord, staged an invasion of Scotland and won a great victory at the Battle of Dupplin Moor

The Battle of Dupplin Moor was fought between supporters of King David II of Scotland, the son of King Robert Bruce, and English-backed invaders supporting Edward Balliol, son of King John I of Scotland, on 11 August 1332. It took place a lit ...

in 1332. They attempted to install Edward Balliol

Edward Balliol (; 1283 – January 1364) was a claimant to the Scottish throne during the Second War of Scottish Independence. With English help, he ruled parts of the kingdom from 1332 to 1356.

Early life

Edward was the eldest son of John Ba ...

as king of Scotland in place of the infant DavidII

''Fritillaria davidii'' is an Asian species of herbaceous plant in the lily family, native to Sichuan Province in China.laying siege to the important border town of Berwick and defeated a large relieving army at the

Historian Nicholas Rodger called EdwardIII's claim to be the "Sovereign of the Seas" into question, arguing there was hardly any royal navy before the reign of HenryV (1413–1422). Despite Rodger's view,

Historian Nicholas Rodger called EdwardIII's claim to be the "Sovereign of the Seas" into question, arguing there was hardly any royal navy before the reign of HenryV (1413–1422). Despite Rodger's view,

Battle of Halidon Hill

The Battle of Halidon Hill took place on 19 July 1333 when a Scottish army under Sir Archibald Douglas attacked an English army commanded by King Edward III of England () and was heavily defeated. The year before, Edward Balliol had seized ...

. He reinstated Balliol on the throne and received a substantial amount of land in southern Scotland. These victories proved hard to sustain, as forces loyal to DavidII gradually regained control of the country. In 1338, EdwardIII was forced to agree to a truce with the Scots.Ormrod (1990), p. 21.

One reason for the change of strategy towards Scotland was a growing concern for the relationship between England and France. For as long as Scotland and France were in an alliance, the English were faced with the prospect of fighting a war on two fronts. The French carried out raids on English coastal towns, leading to rumours in England of a full-scale French invasion.

Mid-reign (1337–1360)

Sluys

In 1337,Philip VI of France

Philip VI (french: Philippe; 1293 – 22 August 1350), called the Fortunate (french: le Fortuné, link=no) or the Catholic (french: le Catholique, link=no) and of Valois, was the first king of France from the House of Valois, reigning from 132 ...

confiscated the English king's Duchy of Aquitaine and the county of Ponthieu. Instead of seeking a peaceful resolution to the conflict by paying homage to the French king, as his father had done, Edward responded by laying claim to the French crown as the grandson of Philip IV Philip IV may refer to:

* Philip IV of Macedon (died 297 BC)

* Philip IV of France (1268–1314), Avignon Papacy

* Philip IV of Burgundy or Philip I of Castile (1478–1506)

* Philip IV, Count of Nassau-Weilburg (1542–1602)

* Philip IV of Spain ...

. The French rejected this based on the precedents for agnatic succession set in 1316 and 1322. Instead, they upheld the rights of PhilipIV's nephew, King PhilipVI (an agnatic descendant of the House of France

The term House of France refers to the branch of the Capetian dynasty which provided the Kings of France following the election of Hugh Capet. The House of France consists of a number of branches and their sub-branches. Some of its branches hav ...

), thereby setting the stage for the Hundred Years' War

The Hundred Years' War (; 1337–1453) was a series of armed conflicts between the kingdoms of Kingdom of England, England and Kingdom of France, France during the Late Middle Ages. It originated from disputed claims to the French Crown, ...

( see family tree below). In the early stages of the war, Edward's strategy was to build alliances with other Continental rulers. In 1338, Louis IV, Holy Roman Emperor

Louis IV (german: Ludwig; 1 April 1282 – 11 October 1347), called the Bavarian (, ), was King of the Romans from 1314, King of Italy from 1327, and Holy Roman Emperor from 1328 until his death in 1347.

Louis' election as king of Germany in ...

, named Edward vicar-general of the Holy Roman Empire and promised his support. As late as 1373, the Anglo-Portuguese Treaty of 1373 established an Anglo-Portuguese Alliance. These measures produced few results; the only major military victory in this phase of the war was the English naval victory at Sluys

Sluis (; zea, label=Zeelandic, Sluus ; french: Écluse) is a town and municipality located in the west of Zeelandic Flanders, in the south-western Dutch province of Zeeland.

The current incarnation of the municipality has existed since 1 January ...

on 24 June 1340, which secured its control of the English Channel.

Cost of war

Meanwhile, the fiscal pressure on the kingdom caused by Edward's expensive alliances led to discontent at home. The regency council at home was frustrated by the mounting national debt, while the king and his commanders on the Continent were angered by the failure of the government in England to provide sufficient funds. To deal with the situation, Edward himself returned to England, arriving in London unannounced on 30 November 1340. Finding the affairs of the realm in disorder, he purged the royal administration of a great number of ministers and judges. These measures did not bring domestic stability, and a stand-off ensued between the king and John de Stratford,Archbishop of Canterbury

The archbishop of Canterbury is the senior bishop and a principal leader of the Church of England, the ceremonial head of the worldwide Anglican Communion and the diocesan bishop of the Diocese of Canterbury. The current archbishop is Justi ...

, during which Stratford's relatives Robert Stratford

Robert de Stratford ( c. 1292 – 9 April 1362) was an English bishop and was one of Edward III's principal ministers.

Early life

Stratford was born into the landed Stratford family of Stratford-on-Avon around 1292. His father was anot ...

, Bishop of Chichester, and Henry de Stratford

Henry de Stratford was a Greater Clerk of the Royal Chancery under Edward III, and member of the Noble House of Stratford.

Life

He was born into the wealthy Stratford Family of Stratford-on-Avon, and was related to Ralph Stratford (Bishop of Lo ...

were temporarily stripped of title and imprisoned respectively. Stratford claimed that Edward had violated the laws of the land by arresting royal officers. A certain level of conciliation was reached at the parliament of April 1341. Here Edward was forced to accept severe limitations to his financial and administrative freedom, in return for a grant of taxation. Yet in October the same year, the king repudiated this statute and Archbishop Stratford was politically ostracised. The extraordinary circumstances of the April parliament had forced the king into submission, but under normal circumstances the powers of the king in medieval England were virtually unlimited, a fact that Edward was able to exploit.

Historian Nicholas Rodger called EdwardIII's claim to be the "Sovereign of the Seas" into question, arguing there was hardly any royal navy before the reign of HenryV (1413–1422). Despite Rodger's view,

Historian Nicholas Rodger called EdwardIII's claim to be the "Sovereign of the Seas" into question, arguing there was hardly any royal navy before the reign of HenryV (1413–1422). Despite Rodger's view, King John King John may refer to:

Rulers

* John, King of England (1166–1216)

* John I of Jerusalem (c. 1170–1237)

* John Balliol, King of Scotland (c. 1249–1314)

* John I of France (15–20 November 1316)

* John II of France (1319–1364)

* John I o ...

had already developed a royal fleet of galley

A galley is a type of ship that is propelled mainly by oars. The galley is characterized by its long, slender hull, shallow draft, and low freeboard (clearance between sea and gunwale). Virtually all types of galleys had sails that could be used ...

s and had attempted to establish an administration for these ships and others which were arrested (privately owned ships pulled into royal/national service). HenryIII, his successor, continued this work. Notwithstanding the fact that he, along with his predecessor, had hoped to develop a strong and efficient naval administration, their endeavours produced one that was informal and mostly ad hoc. A formal naval administration emerged during Edward's reign, comprising lay administrators and led by William de Clewre, Matthew de Torksey and John de Haytfield successively bearing the title of ''Clerk of the King's Ships''. Robert de Crull was the last to fill this position during EdwardIII's reign and would have the longest tenure in this position. It was during his tenure that Edward's naval administration would become a base for what evolved during the reigns of successors such as Henry VIII's ''Council of Marine'' and ''Navy Board'' and Charles I's ''Board of Admiralty''. Rodger also argues that for much of the fourteenth century, the French had the upper hand, apart from Sluys in 1340 and, perhaps, off Winchelsea in 1350. Yet, the French never invaded England and King John II of France died in captivity in England. There was a need for an English navy to play a role in this and to handle other matters, such as the insurrection of the Anglo-Irish lords and acts of piracy.

Crecy and Poitiers

By the early 1340s, it was clear that Edward's policy of alliances was too costly, and yielded too few results. The following years saw more direct involvement by English armies, including in the Breton War of Succession, but these interventions also proved fruitless at first. Edward defaulted on Florentine loans of 1,365,000florin

The Florentine florin was a gold coin struck from 1252 to 1533 with no significant change in its design or metal content standard during that time. It had 54 grains (3.499 grams, 0.113 troy ounce) of nominally pure or 'fine' gold with a purcha ...

s, resulting in the ruin of the lenders.

A major change came in July 1346, when Edward staged a major offensive, sailing for Normandy with a force of 15,000 men. His army sacked the city of Caen

Caen (, ; nrf, Kaem) is a commune in northwestern France. It is the prefecture of the department of Calvados. The city proper has 105,512 inhabitants (), while its functional urban area has 470,000,Flanders. It was not Edward's initial intention to engage the French army, but at Crécy, just north of the  After the fall of Calais, factors outside of Edward's control forced him to wind down the war effort. In 1348, the

After the fall of Calais, factors outside of Edward's control forced him to wind down the war effort. In 1348, the

The middle years of Edward's reign were a period of significant legislative activity. Perhaps the best-known piece of legislation was the Statute of Labourers of 1351, which addressed the labour shortage problem caused by the Black Death. The statute fixed wages at their pre-plague level and checked peasant mobility by asserting that lords had first claim on their men's services. In spite of concerted efforts to uphold the statute, it eventually failed due to competition among landowners for labour. The law has been described as an attempt "to legislate against the law of

The middle years of Edward's reign were a period of significant legislative activity. Perhaps the best-known piece of legislation was the Statute of Labourers of 1351, which addressed the labour shortage problem caused by the Black Death. The statute fixed wages at their pre-plague level and checked peasant mobility by asserting that lords had first claim on their men's services. In spite of concerted efforts to uphold the statute, it eventually failed due to competition among landowners for labour. The law has been described as an attempt "to legislate against the law of

Parliament as a representative institution was already well established by the time of EdwardIII, but the reign was nevertheless central to its development. During this period, membership in the English

Parliament as a representative institution was already well established by the time of EdwardIII, but the reign was nevertheless central to its development. During this period, membership in the English

Central to Edward III's policy was reliance on the higher nobility for purposes of war and administration. While his father had regularly been in conflict with a great portion of his peerage, EdwardIII successfully created a spirit of camaraderie between himself and his greatest subjects.Ormrod (1990), pp. 114–115. Both EdwardI and EdwardII had been limited in their policy towards the nobility, allowing the creation of few new peerages during the sixty years preceding EdwardIII's reign. EdwardIII reversed this trend when, in 1337, as a preparation for the imminent war, he created six new earls on the same day.

At the same time, Edward expanded the ranks of the peerage upwards, by introducing the new title of duke for close relatives of the king. Furthermore, he bolstered the sense of community within this group by the creation of the

Central to Edward III's policy was reliance on the higher nobility for purposes of war and administration. While his father had regularly been in conflict with a great portion of his peerage, EdwardIII successfully created a spirit of camaraderie between himself and his greatest subjects.Ormrod (1990), pp. 114–115. Both EdwardI and EdwardII had been limited in their policy towards the nobility, allowing the creation of few new peerages during the sixty years preceding EdwardIII's reign. EdwardIII reversed this trend when, in 1337, as a preparation for the imminent war, he created six new earls on the same day.

At the same time, Edward expanded the ranks of the peerage upwards, by introducing the new title of duke for close relatives of the king. Furthermore, he bolstered the sense of community within this group by the creation of the

Increasingly, Edward began to rely on his sons for the leadership of military operations. The king's second son, Lionel of Antwerp, attempted to subdue by force the largely autonomous

Increasingly, Edward began to rely on his sons for the leadership of military operations. The king's second son, Lionel of Antwerp, attempted to subdue by force the largely autonomous

Edward III was succeeded by his ten-year-old grandson, King Richard II, son of Edward of Woodstock, since Woodstock himself had died on 8June 1376. In 1376, Edward had signed

Edward III was succeeded by his ten-year-old grandson, King Richard II, son of Edward of Woodstock, since Woodstock himself had died on 8June 1376. In 1376, Edward had signed

Edward III enjoyed unprecedented popularity in his own lifetime, and even the troubles of his later reign were never blamed directly on the king himself. His contemporary Jean Froissart wrote in his ''Chronicles'': "His like had not been seen since the days of King Arthur." This view persisted for a while but, with time, the image of the king changed. The Whig historians of a later age preferred constitutional reform to foreign conquest and accused Edward of ignoring his responsibilities to his own nation. Bishop Stubbs, in his work ''The Constitutional History of England'', states:

This view is challenged in a 1960 article titled "EdwardIII and the Historians", in which

Edward III enjoyed unprecedented popularity in his own lifetime, and even the troubles of his later reign were never blamed directly on the king himself. His contemporary Jean Froissart wrote in his ''Chronicles'': "His like had not been seen since the days of King Arthur." This view persisted for a while but, with time, the image of the king changed. The Whig historians of a later age preferred constitutional reform to foreign conquest and accused Edward of ignoring his responsibilities to his own nation. Bishop Stubbs, in his work ''The Constitutional History of England'', states:

This view is challenged in a 1960 article titled "EdwardIII and the Historians", in which

Edward III

at the official website of the British Monarchy

Edward III

at '' BBC History'' * The ''Medieval Sourcebook'' has some sources relating to the reign of EdwardIII: *

The Ordinance of Labourers, 1349

*

*

* * {{DEFAULTSORT:Edward 03 Of England 1312 births 1377 deaths 14th-century English monarchs 14th-century peers of France Burials at Westminster Abbey Earls of Chester English people of French descent English people of Spanish descent English people of the Wars of Scottish Independence English pretenders to the French throne House of Plantagenet Knights of the Garter Leaders who took power by coup Medieval child rulers People of the Hundred Years' War Sons of kings Children of Edward II of England

Somme __NOTOC__

Somme or The Somme may refer to: Places

*Somme (department), a department of France

*Somme, Queensland, Australia

*Canal de la Somme, a canal in France

*Somme (river), a river in France

Arts, entertainment, and media

* ''Somme'' (book), a ...

, he found favourable terrain and decided to fight a pursuing army led by PhilipVI. On 26 August, the English army defeated a far larger French army in the Battle of Crécy. Shortly after this, on 17 October, an English army defeated and captured King DavidII of Scotland at the Battle of Neville's Cross. With his northern borders secured, Edward felt free to continue his major offensive against France, laying siege to the town of Calais

Calais ( , , traditionally , ) is a port city in the Pas-de-Calais department, of which it is a subprefecture. Although Calais is by far the largest city in Pas-de-Calais, the department's prefecture is its third-largest city of Arras. Th ...

. The operation was the greatest English venture of the Hundred Years' War, involving an army of 35,000 men. The siege started on 4September 1346, and lasted until the town surrendered on 3August 1347.

After the fall of Calais, factors outside of Edward's control forced him to wind down the war effort. In 1348, the

After the fall of Calais, factors outside of Edward's control forced him to wind down the war effort. In 1348, the Black Death

The Black Death (also known as the Pestilence, the Great Mortality or the Plague) was a bubonic plague pandemic occurring in Western Eurasia and North Africa from 1346 to 1353. It is the most fatal pandemic recorded in human history, causi ...

struck England with full force, killing a third or more of the country's population. This loss of manpower led to a shortage of farm labour, and a corresponding rise in wages. The great landowners struggled with the shortage of manpower and the resulting inflation in labour cost. To curb the rise in wages, the king and parliament responded with the Ordinance of Labourers

The Ordinance of Labourers 1349 (23 Edw. 3) is often considered to be the start of English labour law.''Employment Law: Cases and Materials''. Rothstein, Liebman. Sixth Edition, Foundation Press. p. 20. Specifically, it fixed wages and imposed ...

in 1349, followed by the Statute of Labourers

The Statute of Labourers was a law created by the English parliament under King Edward III in 1351 in response to a labour shortage, which aimed at regulating the labour force by prohibiting requesting or offering a wage higher than pre-Plague sta ...

in 1351. These attempts to regulate wages could not succeed in the long run, but in the short term they were enforced with great vigour. All in all, the plague did not lead to a full-scale breakdown of government and society, and recovery was remarkably swift. This was to a large extent thanks to the competent leadership of royal administrators such as Treasurer William Edington and Chief Justice William de Shareshull

Sir William de Shareshull KB (1289/1290–1370) was an English lawyer and Chief Justice of the King's Bench from 26 October 1350 to 5 July 1361. He achieved prominence under the administration of Edward III of England.

He was responsible fo ...

.

It was not until the mid-1350s that military operations on the Continent were resumed on a large scale. In 1356, Edward's eldest son, Edward, Prince of Wales, won an important victory in the Battle of Poitiers. The greatly outnumbered English forces not only routed the French, but captured the French king JohnII and his youngest son, Philip

Philip, also Phillip, is a male given name, derived from the Greek (''Philippos'', lit. "horse-loving" or "fond of horses"), from a compound of (''philos'', "dear", "loved", "loving") and (''hippos'', "horse"). Prominent Philips who popularize ...

. After a succession of victories, the English held great possessions in France, the French king was in English custody, and the French central government had almost totally collapsed. There has been a historical debate as to whether Edward's claim to the French crown originally was genuine, or if it was simply a political ploy meant to put pressure on the French government. Regardless of the original intent, the stated claim now seemed to be within reach. Yet a campaign in 1359, meant to complete the undertaking, was inconclusive. In 1360, therefore, Edward accepted the Treaty of Brétigny, whereby he renounced his claims to the French throne, but secured his extended French possessions in full sovereignty.

Government

Legislation

The middle years of Edward's reign were a period of significant legislative activity. Perhaps the best-known piece of legislation was the Statute of Labourers of 1351, which addressed the labour shortage problem caused by the Black Death. The statute fixed wages at their pre-plague level and checked peasant mobility by asserting that lords had first claim on their men's services. In spite of concerted efforts to uphold the statute, it eventually failed due to competition among landowners for labour. The law has been described as an attempt "to legislate against the law of

The middle years of Edward's reign were a period of significant legislative activity. Perhaps the best-known piece of legislation was the Statute of Labourers of 1351, which addressed the labour shortage problem caused by the Black Death. The statute fixed wages at their pre-plague level and checked peasant mobility by asserting that lords had first claim on their men's services. In spite of concerted efforts to uphold the statute, it eventually failed due to competition among landowners for labour. The law has been described as an attempt "to legislate against the law of supply and demand

In microeconomics, supply and demand is an economic model of price determination in a Market (economics), market. It postulates that, Ceteris paribus, holding all else equal, in a perfect competition, competitive market, the unit price for a ...

", which made it doomed to fail. Nevertheless, the labour shortage had created a community of interest between the smaller landowners of the House of Commons and the greater landowners of the House of Lords. The resulting measures angered the peasants, leading to the Peasants' Revolt of 1381.

The reign of Edward III coincided with the so-called Babylonian Captivity

The Babylonian captivity or Babylonian exile is the period in Jewish history during which a large number of Judeans from the ancient Kingdom of Judah were captives in Babylon, the capital city of the Neo-Babylonian Empire, following their defeat ...

of the papacy at Avignon

Avignon (, ; ; oc, Avinhon, label=Provençal dialect, Provençal or , ; la, Avenio) is the Prefectures in France, prefecture of the Vaucluse Departments of France, department in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur Regions of France, region of So ...

. During the wars with France, opposition emerged in England against perceived injustices by a papacy largely controlled by the French crown. Papal taxation of the English Church was suspected to be financing the nation's enemies, while the practice of provisions (the Pope's providing benefices for clerics) caused resentment in the English population. The statutes of Provisors and Praemunire

In English history, ''praemunire'' or ''praemunire facias'' () refers to a 14th-century law that prohibited the assertion or maintenance of papal jurisdiction, or any other foreign jurisdiction or claim of supremacy in England, against the suprema ...

, of 1350 and 1353 respectively, aimed to amend this by banning papal benefices, as well as limiting the power of the papal court over English subjects. The statutes did not sever the ties between the king and the Pope, who were equally dependent upon each other.

Other legislation of importance includes the Treason Act 1351. It was precisely the harmony of the reign that allowed a consensus on the definition of this controversial crime. Yet the most significant legal reform was probably that concerning the Justices of the Peace. This institution began before the reign of EdwardIII but, by 1350, the justices had been given the power not only to investigate crimes and make arrests, but also to try cases, including those of felony. With this, an enduring fixture in the administration of local English justice had been created.

Parliament and taxation

Parliament as a representative institution was already well established by the time of EdwardIII, but the reign was nevertheless central to its development. During this period, membership in the English

Parliament as a representative institution was already well established by the time of EdwardIII, but the reign was nevertheless central to its development. During this period, membership in the English baron

Baron is a rank of nobility or title of honour, often hereditary, in various European countries, either current or historical. The female equivalent is baroness. Typically, the title denotes an aristocrat who ranks higher than a lord or knig ...

age, formerly a somewhat indistinct group, became restricted to those who received a personal summons

A summons (also known in England and Wales as a claim form and in the Australian state of New South Wales as a court attendance notice (CAN)) is a legal document issued by a court (a ''judicial summons'') or by an administrative agency of governme ...

to parliament. This happened as parliament gradually developed into a bicameral

Bicameralism is a type of legislature, one divided into two separate assemblies, chambers, or houses, known as a bicameral legislature. Bicameralism is distinguished from unicameralism, in which all members deliberate and vote as a single grou ...

institution, composed of a House of Lords and a House of Commons. Yet it was not in the Lords, but in the Commons that the greatest changes took place, with the expanding political role of the Commons. Informative is the Good Parliament, where the Commons for the first time—albeit with noble support—were responsible for precipitating a political crisis. In the process, both the procedure of impeachment

Impeachment is the process by which a legislative body or other legally constituted tribunal initiates charges against a public official for misconduct. It may be understood as a unique process involving both political and legal elements.

In ...

and the office of the Speaker were created. Even though the political gains were of only temporary duration, this parliament represented a watershed in English political history.

The political influence of the Commons originally lay in their right to grant taxes. The financial demands of the Hundred Years' War were enormous, and the king and his ministers tried different methods of covering the expenses. The king had a steady income from crown lands

Crown land (sometimes spelled crownland), also known as royal domain, is a territorial area belonging to the monarch, who personifies the Crown. It is the equivalent of an entailed estate and passes with the monarchy, being inseparable from it. ...

, and could also take up substantial loans from Italian and domestic financiers. To finance warfare, he had to resort to taxation of his subjects. Taxation took two primary forms: levy and customs. The levy was a grant of a proportion of all moveable property, normally a tenth for towns and a fifteenth for farmland. This could produce large sums of money, but each such levy had to be approved by parliament, and the king had to prove the necessity. The customs therefore provided a welcome supplement, as a steady and reliable source of income. An "ancient duty" on the export of wool had existed since 1275. Edward I had tried to introduce an additional duty on wool, but this unpopular '' maltolt'', or "unjust exaction", was soon abandoned. Then, from 1336 onwards, a series of schemes aimed at increasing royal revenues from wool export were introduced. After some initial problems and discontent, it was agreed through the Statute of the Staple

The Ordinance of the Staple was an ordinance issued in the Great Council in October 1353. It aimed to regularise the status of staple ports in England, Wales, and Ireland. In particular, it designated particular ports where specific goods could ...

of 1353 that the new customs should be approved by parliament, though in reality they became permanent.

Through the steady taxation of EdwardIII's reign, parliament—and in particular the Commons—gained political influence. A consensus emerged that in order for a tax to be just, the king had to prove its necessity, it had to be granted by the community of the realm, and it had to be to the benefit of that community. In addition to imposing taxes, parliament would also present petitions for redress of grievances to the king, most often concerning misgovernment by royal officials. This way the system was beneficial for both parties. Through this process the commons, and the community they represented, became increasingly politically aware, and the foundation was laid for the particular English brand of constitutional monarchy.

Chivalry and national identity

Order of the Garter

The Most Noble Order of the Garter is an order of chivalry founded by Edward III of England in 1348. It is the most senior order of knighthood in the British honours system, outranked in precedence only by the Victoria Cross and the George C ...

, probably in 1348. A plan from 1344 to revive the Round Table

The Round Table ( cy, y Ford Gron; kw, an Moos Krenn; br, an Daol Grenn; la, Mensa Rotunda) is King Arthur's famed table in the Arthurian legend, around which he and his knights congregate. As its name suggests, it has no head, implying that e ...

of King Arthur

King Arthur ( cy, Brenin Arthur, kw, Arthur Gernow, br, Roue Arzhur) is a legendary king of Britain, and a central figure in the medieval literary tradition known as the Matter of Britain.

In the earliest traditions, Arthur appears as a ...

never came to fruition, but the new order carried connotations from this legend by the circular shape of the garter. Edward's wartime experiences during the Crécy campaign (1346–7) seem to have been a determining factor in his abandonment of the Round Table project. It has been argued that the total warfare tactics employed by the English at Crécy in 1346 were contrary to Arthurian ideals and made Arthur a problematic paradigm for Edward, especially at the time of the institution of the Garter. There are no formal references to King Arthur and the Round Table in the surviving early fifteenth-century copies of the Statutes of the Garter, but the Garter Feast of 1358 did involve a round table game. Thus there was some overlap between the projected Round Table fellowship and the actualized Order of the Garter. Polydore Vergil tells of how the young Joan of Kent—allegedly the king's favourite at the time—accidentally dropped her garter at a ball at Calais. King Edward responded to the ensuing ridicule of the crowd by tying the garter around his own knee with the words '' honi soit qui mal y pense'' (shame on him who thinks ill of it).

This reinforcement of the aristocracy and the emerging sense of national identity must be seen in conjunction with the war in France. Just as the war with Scotland had done, the fear of a French invasion helped strengthen a sense of national unity, and nationalise the aristocracy that had been largely Anglo-Norman since the Norman conquest. Since the time of EdwardI, popular myth suggested that the French planned to extinguish the English language, and as his grandfather had done, EdwardIII made the most of this scare. As a result, the English language experienced a strong revival; in 1362, a Statute of Pleading

The Pleading in English Act 1362 (''36 Edw. III c. 15''), often rendered Statute of Pleading, was an Act of the Parliament of England. The Act complained that because the Norman French language was largely unknown to the common people of England ...

ordered English to be used in law courts, and the year after, Parliament was for the first time opened in English. At the same time, the vernacular saw a revival as a literary language, through the works of William Langland, John Gower and especially ''The Canterbury Tales

''The Canterbury Tales'' ( enm, Tales of Caunterbury) is a collection of twenty-four stories that runs to over 17,000 lines written in Middle English by Geoffrey Chaucer between 1387 and 1400. It is widely regarded as Chaucer's ''Masterpiece, ...

'' by Geoffrey Chaucer

Geoffrey Chaucer (; – 25 October 1400) was an English poet, author, and civil servant best known for ''The Canterbury Tales''. He has been called the "father of English literature", or, alternatively, the "father of English poetry". He wa ...

. Yet the extent of this Anglicisation

Anglicisation is the process by which a place or person becomes influenced by English culture or British culture, or a process of cultural and/or linguistic change in which something non-English becomes English. It can also refer to the influen ...

must not be exaggerated. The statute of 1362 was in fact written in the French language and had little immediate effect, and parliament was opened in that language as late as 1377. The Order of the Garter, though a distinctly English institution, included also foreign members such as John IV, Duke of Brittany, and Robert of Namur.

Later years and death (1360–1377)

While Edward's early reign had been energetic and successful, his later years were marked by inertia, military failure and political strife. The day-to-day affairs of the state had less appeal to Edward than military campaigning, so during the 1360s Edward increasingly relied on the help of his subordinates, in particular William Wykeham. A relative upstart, Wykeham was made Keeper of the Privy Seal in 1363 andChancellor

Chancellor ( la, cancellarius) is a title of various official positions in the governments of many nations. The original chancellors were the of Roman courts of justice—ushers, who sat at the or lattice work screens of a basilica or law cou ...

in 1367, though due to political difficulties connected with his inexperience, the Parliament forced him to resign the chancellorship in 1371. Compounding Edward's difficulties were the deaths of his most trusted men, some from the 1361–62 recurrence of the plague. William Montagu, 1st Earl of Salisbury, Edward's companion in the 1330 coup, died as early as 1344. William de Clinton, 1st Earl of Huntingdon, who had also been with the king at Nottingham, died in 1354. One of the earls created in 1337, William de Bohun, 1st Earl of Northampton, died in 1360, and the next year Henry of Grosmont, perhaps the greatest of Edward's captains, succumbed to what was probably plague. Their deaths left the majority of the magnates younger and more naturally aligned to the princes than to the king himself.

Increasingly, Edward began to rely on his sons for the leadership of military operations. The king's second son, Lionel of Antwerp, attempted to subdue by force the largely autonomous

Increasingly, Edward began to rely on his sons for the leadership of military operations. The king's second son, Lionel of Antwerp, attempted to subdue by force the largely autonomous Anglo-Irish

Anglo-Irish people () denotes an ethnic, social and religious grouping who are mostly the descendants and successors of the English Protestant Ascendancy in Ireland. They mostly belong to the Anglican Church of Ireland, which was the establis ...

lords in Ireland. The venture failed, and the only lasting mark he left were the suppressive Statutes of Kilkenny in 1366. In France, meanwhile, the decade following the Treaty of Brétigny was one of relative tranquillity, but on 8April 1364 JohnII died in captivity in England, after unsuccessfully trying to raise his own ransom at home. He was followed by the vigorous CharlesV, who enlisted the help of the capable Bertrand du Guesclin, Constable of France

The Constable of France (french: Connétable de France, from Latin for 'count of the stables') was lieutenant to the King of France, the first of the original five Great Officers of the Crown (along with seneschal, chamberlain, butler, and chanc ...

. In 1369, the French war started anew, and Edward's son John of Gaunt

John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster (6 March 1340 – 3 February 1399) was an English royal prince, military leader, and statesman. He was the fourth son (third to survive infancy as William of Hatfield died shortly after birth) of King Edward ...

was given the responsibility of a military campaign. The effort failed, and with the Treaty of Bruges in 1375, the great English possessions in France were reduced to only the coastal towns of Calais

Calais ( , , traditionally , ) is a port city in the Pas-de-Calais department, of which it is a subprefecture. Although Calais is by far the largest city in Pas-de-Calais, the department's prefecture is its third-largest city of Arras. Th ...

, Bordeaux, and Bayonne

Bayonne (; eu, Baiona ; oc, label= Gascon, Baiona ; es, Bayona) is a city in Southwestern France near the Spanish border. It is a commune and one of two subprefectures in the Pyrénées-Atlantiques department, in the Nouvelle-Aquitaine re ...

.

Military failure abroad, and the associated fiscal pressure of constant campaigns, led to political discontent at home. The problems came to a head in the parliament of 1376, the so-called Good Parliament. The parliament was called to grant taxation, but the House of Commons took the opportunity to address specific grievances. In particular, criticism was directed at some of the king's closest advisors. Lord Chamberlain William Latimer, 4th Baron Latimer, and Steward of the Household

The Lord Steward or Lord Steward of the Household is an official of the Royal Household in England. He is always a peer. Until 1924, he was always a member of the Government. Until 1782, the office was one of considerable political importance ...

John Neville, 3rd Baron Neville de Raby, were dismissed from their positions. Edward's mistress, Alice Perrers

Alice Perrers, also known as Alice de Windsor (circa 1348 –1400) was an English and British royal mistress, English royal mistress, lover of Edward III of England, Edward III, Monarchy of the United Kingdom, King of England. As a result o ...

, who was seen to hold far too much power over the ageing king, was banished from court. Yet the real adversary of the Commons, supported by powerful men such as Wykeham and Edmund Mortimer, 3rd Earl of March, was John of Gaunt. Both the king and Edward of Woodstock were by this time incapacitated by illness, leaving Gaunt in virtual control of government. Gaunt was forced to give in to the demands of parliament, but at its next convocation, in 1377, most of the achievements of the Good Parliament were reversed.

Edward did not have much to do with any of this; after around 1375 he played a limited role in the government of the realm. Around 29 September 1376 he fell ill with a large abscess

An abscess is a collection of pus that has built up within the tissue of the body. Signs and symptoms of abscesses include redness, pain, warmth, and swelling. The swelling may feel fluid-filled when pressed. The area of redness often extends b ...

. After a brief period of recovery in February 1377, the king died of a stroke at Sheen on 21 June.Ormrod (1990), p. 52.

Succession

Edward III was succeeded by his ten-year-old grandson, King Richard II, son of Edward of Woodstock, since Woodstock himself had died on 8June 1376. In 1376, Edward had signed

Edward III was succeeded by his ten-year-old grandson, King Richard II, son of Edward of Woodstock, since Woodstock himself had died on 8June 1376. In 1376, Edward had signed letters patent

Letters patent ( la, litterae patentes) ( always in the plural) are a type of legal instrument in the form of a published written order issued by a monarch, president or other head of state, generally granting an office, right, monopoly, titl ...

on the order of succession to the crown, citing in second position John of Gaunt, born in 1340, but ignoring Philippa, daughter of Lionel, born in 1338. Philippa's exclusion contrasted with a decision by Edward I

Edward I (17/18 June 1239 – 7 July 1307), also known as Edward Longshanks and the Hammer of the Scots, was King of England and Lord of Ireland from 1272 to 1307. Concurrently, he ruled the duchies of Aquitaine and Gascony as a vassal o ...

in 1290, which had recognized the right of women to inherit the crown and to pass it on to their descendants. The order of succession determined in 1376 led the House of Lancaster

The House of Lancaster was a cadet branch of the royal House of Plantagenet. The first house was created when King Henry III of England created the Earldom of Lancasterfrom which the house was namedfor his second son Edmund Crouchback in 126 ...

to the throne in 1399 (John of Gaunt was Duke of Lancaster), whereas the rule decided by Edward I would have favoured Philippa's descendants, among them the House of York

The House of York was a cadet branch of the English royal House of Plantagenet. Three of its members became kings of England in the late 15th century. The House of York descended in the male line from Edmund of Langley, 1st Duke of York, ...

, beginning with Richard of York

Richard of York, 3rd Duke of York (21 September 1411 – 30 December 1460), also named Richard Plantagenet, was a leading English magnate and claimant to the throne during the Wars of the Roses. He was a member of the ruling House of Plantage ...

, her great-grandson.

Legacy

Edward III enjoyed unprecedented popularity in his own lifetime, and even the troubles of his later reign were never blamed directly on the king himself. His contemporary Jean Froissart wrote in his ''Chronicles'': "His like had not been seen since the days of King Arthur." This view persisted for a while but, with time, the image of the king changed. The Whig historians of a later age preferred constitutional reform to foreign conquest and accused Edward of ignoring his responsibilities to his own nation. Bishop Stubbs, in his work ''The Constitutional History of England'', states:

This view is challenged in a 1960 article titled "EdwardIII and the Historians", in which

Edward III enjoyed unprecedented popularity in his own lifetime, and even the troubles of his later reign were never blamed directly on the king himself. His contemporary Jean Froissart wrote in his ''Chronicles'': "His like had not been seen since the days of King Arthur." This view persisted for a while but, with time, the image of the king changed. The Whig historians of a later age preferred constitutional reform to foreign conquest and accused Edward of ignoring his responsibilities to his own nation. Bishop Stubbs, in his work ''The Constitutional History of England'', states:

This view is challenged in a 1960 article titled "EdwardIII and the Historians", in which May McKisack

May McKisack (1900–1981) was a British medieval historian. She was professor of history at Westfield College in London and later professor of historiography at the University of Oxford and an honorary fellow of Somerville College Oxford. She is ...

points out the teleological nature of Stubbs' judgement. A medieval king could not be expected to work towards some future ideal of a parliamentary monarchy as if it were good in itself; rather, his role was a pragmatic one – to maintain order and solve problems as they arose. At this, Edward excelled. Edward had also been accused of endowing his younger sons too liberally and thereby promoting dynastic strife culminating in the Wars of the Roses. This claim was rejected by K.B. McFarlane

Kenneth Bruce McFarlane, FBA (18 October 1903 – 16 July 1966) was one of the 20th century's most influential historians of late medieval England.

Life

McFarlane was born on 18 October 1903, the only child of A. McFarlane, OBE. His father was ...

, who argued that this was not only the common policy of the age, but also the best. Later biographers of the king such as Mark Ormrod and Ian Mortimer have followed this historiographical trend. The older negative view has not completely disappeared; as recently as 2001, Norman Cantor

Norman Frank Cantor (November 19, 1929 – September 18, 2004) was a Canadian-American historian who specialized in the Middle Ages, medieval period. Known for his accessible writing and engaging narrative style, Cantor's books were among the mo ...

described Edward as an "avaricious and sadistic thug" and a "destructive and merciless force".

From what is known of Edward's character, he could be impulsive and temperamental, as was seen by his actions against Stratford and the ministers in 1340/41. At the same time, he was well known for his clemency; Mortimer's grandson

Family (from la, familia) is a Social group, group of people related either by consanguinity (by recognized birth) or Affinity (law), affinity (by marriage or other relationship). The purpose of the family is to maintain the well-being of its ...

was not only absolved, he came to play an important part in the French wars and was eventually made a Knight of the Garter. Both in his religious views and his interests, Edward was a conventional man. His favourite pursuit was the art of war and, in this, he conformed to the medieval notion of good kingship. As a warrior he was so successful that one modern military historian has described him as the greatest general in English history. He seems to have been unusually devoted to his wife, Queen Philippa

Philippa of Hainault (sometimes spelled Hainaut; Middle French: ''Philippe de Hainaut''; 24 June 1310 (or 1315) – 15 August 1369) was Queen of England as the wife and political adviser of King Edward III. She acted as regent in 1346,Strickla ...

. Much has been made of Edward's sexual licentiousness, but there is no evidence of any infidelity on his part before Alice Perrers became his lover, and by that time the queen was already terminally ill. This devotion extended to the rest of the family as well; in contrast to so many of his predecessors, Edward never experienced opposition from any of his five adult sons.

Issue

Sons

* Edward the Black Prince (1330–1376), eldest son and heir apparent, born at Woodstock Palace,Oxfordshire

Oxfordshire is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in the north west of South East England. It is a mainly rural county, with its largest settlement being the city of Oxford. The county is a centre of research and development, primarily ...

. He predeceased his father, having in 1361 married his cousin Joan, Countess of Kent, by whom he had issue: King RichardII;

* William of Hatfield (1337–1337), second son, born at Hatfield, South Yorkshire, died shortly after birth and was buried in York Minster;

* Lionel of Antwerp, 1st Duke of Clarence (1338–1368), third son (second surviving son), born at Antwerp

Antwerp (; nl, Antwerpen ; french: Anvers ; es, Amberes) is the largest city in Belgium by area at and the capital of Antwerp Province in the Flemish Region. With a population of 520,504,

in the Duchy of Brabant, where his father was based during his negotiations with Jacob van Artevelde. In 1352 he married firstly Elizabeth de Burgh, 4th Countess of Ulster

Elizabeth de Burgh, Duchess of Clarence, ''suo jure'' 4th Countess of Ulster and 5th Baroness of Connaught (; ; 6 July 1332 – 10 December 1363) was a Norman-Irish noblewoman who married Lionel of Antwerp, 1st Duke of Clarence.

Family

Elizab ...

, without male issue, but his female issue was the senior royal ancestor of the Yorkist King EdwardIV: Philippa, 5th Countess of Ulster. Descent from Lionel was the basis of the Yorkist claim to the throne, not direct paternal descent from the 1st Duke of York, a more junior line. Secondly, in 1368, Lionel married Violante Visconti

Violante (Jolantha) Visconti (1354 – November 1386) was the second of two children of Galeazzo II Visconti, Lord of Milan and Pavia, and Bianca of Savoy. Her father gave to her the provinces of Alba, Mondovì, Kenites, Cherasco, and Demonte as ...

, without issue.

* John of Gaunt, 1st Duke of Lancaster (1340–1399), fourth son (third surviving son), born at "Gaunt" ( Ghent) in the County of Flanders, which city was an important buyer of English wool, then the foundation of English prosperity. In 1359, he married firstly his distant cousin the great heiress Blanche of Lancaster, descended from the 1st Earl of Lancaster, a younger son of King HenryIII. By Blanche he had issue: Henry of Bolingbroke, who became King HenryIV, having seized the throne from his first cousin King RichardII. In 1371, he married secondly the Infanta Constance of Castile, by whom he had issue. In 1396, he married thirdly his mistress Katherine Swynford

Katherine Swynford, Duchess of Lancaster (born Katherine de Roet, – 10 May 1403), also spelled Katharine or Catherine, was the third wife of John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster, the fourth (but third surviving) son of King Edward III.

Daughter o ...

, by whom he had illegitimate issue, later legitimised as the House of Beaufort. His great-granddaughter Margaret Beaufort was the mother of Henry VII, who claimed the throne as the representative of the Lancastrian line.

* Edmund of Langley, 1st Duke of York

Edmund of Langley, Duke of York (5 June 1341 – 1 August 1402) was the fourth surviving son of King Edward III of England and Philippa of Hainault. Like many medieval English princes, Edmund gained his nickname from his birthplace: Kings Langle ...

(1341–1402), fifth son (fourth surviving son), born at Kings Langley Palace, Hertfordshire

Hertfordshire ( or ; often abbreviated Herts) is one of the home counties in southern England. It borders Bedfordshire and Cambridgeshire to the north, Essex to the east, Greater London to the south, and Buckinghamshire to the west. For govern ...

. He married firstly the Infanta Isabella of Castile, by whom he had issue, sister of the Infanta Constance of Castile, second wife of his elder brother John of Gaunt, 1st Duke of Lancaster. Secondly in 1392 he married his second cousin Joan Holland

Lady Joan Holland (ca. 1380–12 April 1434) was the third daughter of Thomas Holland, 2nd Earl of Kent, and Lady Alice FitzAlan. She married four times. Her first husband was a duke, and the following three were barons. All of her marria ...

, without issue. His great-grandson (the 4th Duke of York) became King EdwardIV in 1461, having deposed his half-second cousin the Lancastrian King HenryVI. EdwardIV's daughter Elizabeth of York was mother of King HenryVIII.

* Thomas of Windsor (1347–1348), sixth son, born at Windsor Castle, died in infancy of the plague and was buried at King's Langley Priory

King's Langley Priory was a Dominican priory in Kings Langley, Hertfordshire, England. It was located adjacent to the Kings Langley Royal Palace, residence of the Plantagenet English kings.

History

Langley was founded in 1308 by Edward II in ...

, Hertfordshire;

* William of Windsor (1348–1348), seventh son, born before 24 June 1348 at Windsor Castle, died in infancy probably on 9 July1348, buried on 5 September 1348 in Westminster Abbey;

* Thomas of Woodstock, 1st Duke of Gloucester (1355–1397), eighth son (fifth surviving son), born at Woodstock Palace in Oxfordshire

Oxfordshire is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in the north west of South East England. It is a mainly rural county, with its largest settlement being the city of Oxford. The county is a centre of research and development, primarily ...

; in 1376 he married Eleanor de Bohun, by whom he had issue. His eventual heir was the Bourchier family, Earls of Bath, of Tawstock in Devon, today represented by the Wrey baronets, who quarter the arms of Thomas of Woodstock and continue as lords of the manor of Tawstock.

Daughters

*Isabella of England

Isabella of England (1214 – 1 December 1241) was an English princess of the House of Plantagenet. She became Holy Roman Empress, Queen of Sicily, Italy and Germany from 1235 until her death as the third wife of Emperor Frederick II.

Life B ...

(1332–1379/82), born at Woodstock Palace, Oxfordshire

Oxfordshire is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in the north west of South East England. It is a mainly rural county, with its largest settlement being the city of Oxford. The county is a centre of research and development, primarily ...

, in 1365 married Enguerrand VII de Coucy, 1st Earl of Bedford, by whom she had issue;

* Joan of England (1333/4–1348), born in the Tower of London; she was betrothed to Peter of Castile but died of the black death

The Black Death (also known as the Pestilence, the Great Mortality or the Plague) was a bubonic plague pandemic occurring in Western Eurasia and North Africa from 1346 to 1353. It is the most fatal pandemic recorded in human history, causi ...

en route to Castile before the marriage could take place. Peter's two daughters from his union with María de Padilla married Joan's younger brothers John of Gaunt, 1st Duke of Lancaster and Edmund of Langley, 1st Duke of York

Edmund of Langley, Duke of York (5 June 1341 – 1 August 1402) was the fourth surviving son of King Edward III of England and Philippa of Hainault. Like many medieval English princes, Edmund gained his nickname from his birthplace: Kings Langle ...

.

* Blanche (1342–1342), born in the Tower of London, died shortly after birth and was buried in Westminster Abbey.

* Mary of Waltham (1344–1361), born at Bishop's Waltham, Hampshire; in 1361 she married John IV, Duke of Brittany, without issue;

* Margaret

Margaret is a female first name, derived via French () and Latin () from grc, μαργαρίτης () meaning "pearl". The Greek is borrowed from Persian.

Margaret has been an English name since the 11th century, and remained popular througho ...

(Countess of Pembroke) (1346–1361), born at Windsor Castle; in 1359 she married John Hastings, 2nd Earl of Pembroke, without issue;

Genealogical tables

Edward's relationship to contemporary kings of France, Navarre, and ScotlandOrmrod (1990).Explanatory notes

References

Citations

General and cited sources

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *External links

Edward III

at the official website of the British Monarchy

Edward III

at '' BBC History'' * The ''Medieval Sourcebook'' has some sources relating to the reign of EdwardIII: *

The Ordinance of Labourers, 1349

*

*

* * {{DEFAULTSORT:Edward 03 Of England 1312 births 1377 deaths 14th-century English monarchs 14th-century peers of France Burials at Westminster Abbey Earls of Chester English people of French descent English people of Spanish descent English people of the Wars of Scottish Independence English pretenders to the French throne House of Plantagenet Knights of the Garter Leaders who took power by coup Medieval child rulers People of the Hundred Years' War Sons of kings Children of Edward II of England