The Khalistan movement is a

Sikh

Sikhs ( or ; pa, ਸਿੱਖ, ' ) are people who adhere to Sikhism, Sikhism (Sikhi), a Monotheism, monotheistic religion that originated in the late 15th century in the Punjab region of the Indian subcontinent, based on the revelation of Gu ...

separatist movement

Separatism is the advocacy of cultural, ethnic, tribal, religious, racial, governmental or gender separation from the larger group. As with secession, separatism conventionally refers to full political separation. Groups simply seeking greate ...

seeking to create a homeland for Sikhs by establishing a

sovereign state

A sovereign state or sovereign country, is a polity, political entity represented by one central government that has supreme legitimate authority over territory. International law defines sovereign states as having a permanent population, defin ...

, called Khālistān ('

Land of the

Khalsa

Khalsa ( pa, ਖ਼ਾਲਸਾ, , ) refers to both a community that considers Sikhism as its faith,[Kha ...]

'), in the

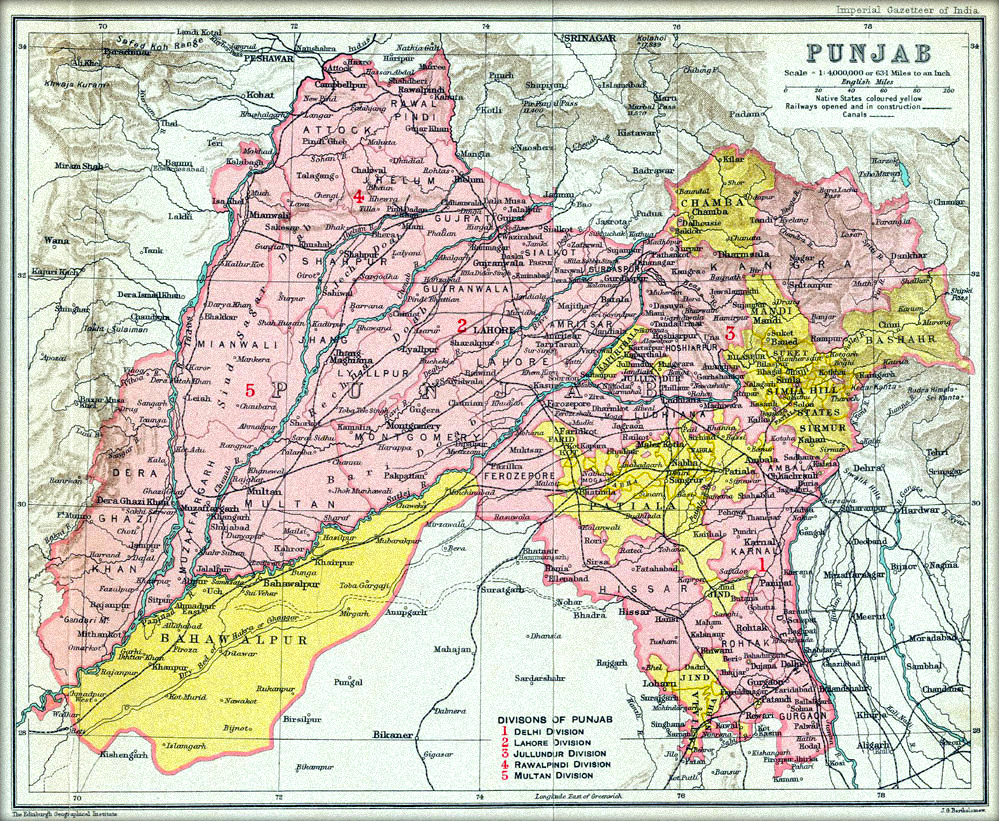

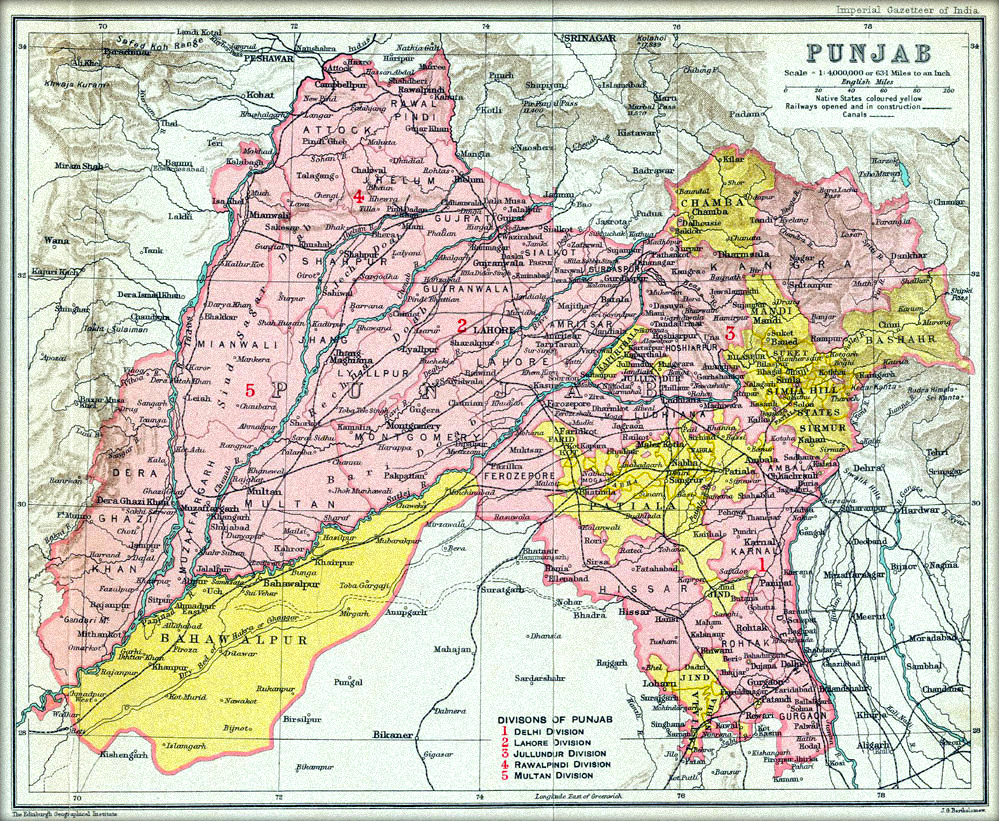

Punjab region

Punjab (; Punjabi Language, Punjabi: پنجاب ; ਪੰਜਾਬ ; ; also Romanization, romanised as ''Panjāb'' or ''Panj-Āb'') is a geopolitical, cultural, and historical region in South Asia, specifically in the northern part of the I ...

. The proposed state would consist of land that currently forms

Punjab, India

Punjab (; ) is a States and union territories of India, state in northern India. Forming part of the larger Punjab region of the Indian subcontinent, the state is bordered by the States and union territories of India, Indian states of Himachal ...

and

Punjab, Pakistan

Punjab (; , ) is one of the four provinces of Pakistan. Located in central-eastern region of the country, Punjab is the second-largest province of Pakistan by land area and the largest province by population. It shares land borders with the ...

.

[: ]

Ever since the separatist movement gathered force in the 1980s, the territorial ambitions of Khalistan have at times included

Chandigarh

Chandigarh () is a planned city in India. Chandigarh is bordered by the state of Punjab to the west and the south, and by the state of Haryana to the east. It constitutes the bulk of the Chandigarh Capital Region or Greater Chandigarh, which al ...

, sections of the Indian Punjab, including the whole of

North India

North India is a loosely defined region consisting of the northern part of India. The dominant geographical features of North India are the Indo-Gangetic Plain and the Himalayas, which demarcate the region from the Tibetan Plateau and Central ...

, and some parts of the western states of India.

[Crenshaw, Martha, 1995, ''Terrorism in Context'', ]Pennsylvania State University

The Pennsylvania State University (Penn State or PSU) is a Public university, public Commonwealth System of Higher Education, state-related Land-grant university, land-grant research university with campuses and facilities throughout Pennsylvan ...

, p. 364 Prime Minister of Pakistan

The prime minister of Pakistan ( ur, , romanized: Wazīr ē Aʿẓam , ) is the head of government of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan. Executive authority is vested in the prime minister and his chosen cabinet, despite the president of Paki ...

Zulfikar Ali Bhutto

Zulfikar (or Zulfiqar) Ali Bhutto ( ur, , sd, ذوالفقار علي ڀٽو; 5 January 1928 – 4 April 1979), also known as Quaid-e-Awam ("the People's Leader"), was a Pakistani barrister, politician and statesman who served as the fourth ...

, according to

Jagjit Singh Chohan

Jagjit Singh Chohan was the founder of the Khalistan movement that sought to create an independent Sikh state in the Punjab region of India and Pakistan.

Politics

Jagjit Singh grew up in Tanda in Punjab's Hoshiarpur district, about 180 km ...

, had proposed all out help to create Khalistan during his talks with Chohan, following the conclusion of the

Indo-Pakistani War of 1971

The Indo-Pakistani War of 1971 was a military confrontation between India and Pakistan that occurred during the Bangladesh Liberation War in East Pakistan from 3 December 1971 until the

Pakistani capitulation in Dhaka on 16 Decem ...

.

The call for a separate Sikh state began in the wake of the fall of the

British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts esta ...

.

In 1940, the first explicit call for Khalistan was made in a pamphlet titled "Khalistan". With financial and political support of the

Sikh diaspora

The Sikh diaspora is the modern Sikh migration from the traditional area of the Punjab region of India. Sikhism is a religion, the Punjab region of India being the historic homeland of Sikhism. The Sikh diaspora is largely a subset of the Pun ...

, the movement flourished in the Indian state of Punjab – which has a

Sikh-majority population – continuing through the 1970s and 1980s, and reaching its zenith in the late 1980s. In the 1990s, the insurgency petered out,

and the movement failed to reach its objective for multiple reasons including a heavy police crackdown on separatists, factional infighting, and disillusionment from the Sikh population.

There is some support within India and the Sikh diaspora, with yearly demonstrations in protest of those killed during

Operation Blue Star

Operation Blue Star was the codename of a military operation which was carried out by Indian security forces between 1 and 10 June 1984 in order to remove Damdami Taksal leader Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale and his followers from the buildings of ...

. In early 2018, some militant groups were arrested by police in Punjab, India.

Former

Chief Minister of Punjab Amarinder Singh

Captain Amarinder Singh (born 11 March 1942), is an Indian politician, military historian, former royal and Indian Army veteran who served as the 15th Chief Minister of Punjab. A former Member of the Legislative Assembly, Punjab and Member ...

claimed that the recent extremism is backed by Pakistan's

Inter-Services Intelligence

The Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI; ur, , bayn khadamatiy mukhabarati) is the premier intelligence agency of Pakistan. It is responsible for gathering, processing, and analyzing any information from around the world that is deemed relevant ...

(ISI) and "Khalistani sympathisers" in

Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by tot ...

,

Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical re ...

, and the

UK.

Simranjit Singh Mann, elected in 2022 from Sangrur, is currently the only openly Khalistani MP in the Indian Parliament and his party,

Shiromani Akali Dal (Amritsar)

Shiromani Akali Dal (Amritsar) is Khalistan movement, separatist political party led by Simranjit Singh Mann, it is a splinter group of the Shiromani Akali Dal. Shiromani Akali Dal (Amritsar) was formed on the 1st of May 1994.

Electoral success ...

, is currently the only pro-Khalistan party in the Indian parliament.

Pre-1950s

Sikhs have been concentrated in the

Punjab region

Punjab (; Punjabi Language, Punjabi: پنجاب ; ਪੰਜਾਬ ; ; also Romanization, romanised as ''Panjāb'' or ''Panj-Āb'') is a geopolitical, cultural, and historical region in South Asia, specifically in the northern part of the I ...

of

South Asia

South Asia is the southern subregion of Asia, which is defined in both geographical and ethno-cultural terms. The region consists of the countries of Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka.;;;;;;;; ...

. Before its conquest by the British, the region around Punjab had been ruled by the confederacy of Sikh

Misl

The Misls (derived from an Arabic word wikt:مثل#Etymology_3, مِثْل meaning 'equal') were the twelve sovereign states of the Sikh Confederacy, which rose during the 18th century in the Punjab region in the northern part of the Indian ...

s founded by

Banda Bahadur

Banda Singh Bahadur (born Lachman Dev) (27 October 1670 – 9 June 1716), was a Sikh warrior and a commander of Khalsa army. At age 15, he left home to become an ascetic, and was given the name Madho Das Bairagi. He established a monastery a ...

. The Misls ruled over the entire Punjab from 1767 to 1799, until their confederacy was unified into the

Sikh Empire

The Sikh Empire was a state originating in the Indian subcontinent, formed under the leadership of Maharaja Ranjit Singh, who established an empire based in the Punjab. The empire existed from 1799, when Maharaja Ranjit Singh captured Lahor ...

by

Maharajah Ranjit Singh

Ranjit Singh (13 November 1780 – 27 June 1839), popularly known as Sher-e-Punjab or "Lion of Punjab", was the first Maharaja of the Sikh Empire, which ruled the northwest Indian subcontinent in the early half of the 19th century. He s ...

from 1799 to 1849.

At the end of the

Second Anglo-Sikh War

The Second Anglo-Sikh War was a military conflict between the Sikh Empire and the East India Company, British East India Company that took place in 1848 and 1849. It resulted in the fall of the Sikh Empire, and the annexation of the Punjab r ...

in 1849, the Sikh Empire dissolved into separate

princely state

A princely state (also called native state or Indian state) was a nominally sovereign entity of the British Raj, British Indian Empire that was not directly governed by the British, but rather by an Indian ruler under a form of indirect rule, ...

s and the

British province of Punjab. In newly conquered regions, "religio-nationalist movements emerged in response to British “

divide and rule

Divide and rule policy ( la, divide et impera), or divide and conquer, in politics and sociology is gaining and maintaining power divisively. Historically, this strategy was used in many different ways by empires seeking to expand their terr ...

” administrative policies, the perceived success of Christian missionaries converting Hindu, Sikhs and Muslims, and a general belief that the solution to the downfall among India's religious communities was a grassroots religious revival."

As the British Empire began to dissolve in the 1930s, Sikhs made their first call for a Sikh homeland.

When the

Lahore Resolution

The Lahore Resolution ( ur, , ''Qarardad-e-Lahore''; Bengali: লাহোর প্রস্তাব, ''Lahor Prostab''), also called Pakistan resolution, was written and prepared by Muhammad Zafarullah Khan and was presented by A. K. Fazlul ...

of the

Muslim League Muslim League may refer to:

Political parties Subcontinent

; British India

*All-India Muslim League, Mohammed Ali Jinah, led the demand for the partition of India resulting in the creation of Pakistan.

**Punjab Muslim League, a branch of the organ ...

demanded Punjab be made into a Muslim state, the

Akalis viewed it as an attempt to usurp a historically Sikh territory. In response, the Sikh party

Shiromani Akali Dal

The Shiromani Akali Dal (SAD) (translation: ''Supreme Akali Party'') is a centre-right sikh-centric state political party in Punjab, India. The party is the second-oldest in India, after Congress, being founded in 1920. Although there are many ...

argued for a community that was separate from Hindus and Muslims. The Akali Dal imagined Khalistan as a

theocratic

Theocracy is a form of government in which one or more deities are recognized as supreme ruling authorities, giving divine guidance to human intermediaries who manage the government's daily affairs.

Etymology

The word theocracy originates fro ...

state led by the

Maharaja of Patiala

The Maharaja of Patiala was a maharaja in India and the ruler of the princely state of Patiala, a state in British India. The first Maharaja of Patiala was Baba Ala Singh (1695–1765).

Yadavindra Singh became the maharaja on 23 March 1938. H ...

with the aid of a cabinet consisting of the representatives of other units. The country would include parts of present-day

Punjab, India

Punjab (; ) is a States and union territories of India, state in northern India. Forming part of the larger Punjab region of the Indian subcontinent, the state is bordered by the States and union territories of India, Indian states of Himachal ...

, present-day

Punjab, Pakistan

Punjab (; , ) is one of the four provinces of Pakistan. Located in central-eastern region of the country, Punjab is the second-largest province of Pakistan by land area and the largest province by population. It shares land borders with the ...

(including

Lahore

Lahore ( ; pnb, ; ur, ) is the second most populous city in Pakistan after Karachi and 26th most populous city in the world, with a population of over 13 million. It is the capital of the province of Punjab where it is the largest city. ...

), and the

Simla

Shimla (; ; also known as Simla, the official name until 1972) is the capital and the largest city of the northern Indian state of Himachal Pradesh. In 1864, Shimla was declared as the summer capital of British India. After independence, the ...

Hill States

The Hill States of India were princely states lying in the northern border regions of the British Indian Empire.

History

During the colonial Raj period, two groups of princely states in direct relations with the Province of British Punjab ...

.

Partition of India, 1947

Before the 1947

partition of India

The Partition of British India in 1947 was the Partition (politics), change of political borders and the division of other assets that accompanied the dissolution of the British Raj in South Asia and the creation of two independent dominions: ...

, Sikhs were not in majority in any of the districts of pre-partition

British Punjab Province other than

Ludhiana

Ludhiana ( ) is the most populous and the largest Cities in India, city in the Indian state of Punjab, India, Punjab. The city has an estimated population of 1,618,879 2011 Indian census, 2011 census and distributed over , making Ludhiana the ...

(where Sikhs formed 41.6% of the population). Rather, districts in the region had a majority of either the Hindus or Muslims depending on its location in the province.

British India

The provinces of India, earlier presidencies of British India and still earlier, presidency towns, were the administrative divisions of British governance on the Indian subcontinent. Collectively, they have been called British India. In one ...

was partitioned on a religious basis in 1947, where the Punjab province was divided between India and the newly-created Pakistan. As result, a majority of Sikhs, along with the Hindus, migrated from the Pakistani region to India's Punjab, which included present-day

Haryana

Haryana (; ) is an Indian state located in the northern part of the country. It was carved out of the former state of East Punjab on 1 Nov 1966 on a linguistic basis. It is ranked 21st in terms of area, with less than 1.4% () of India's land ar ...

and

Himachal Pradesh

Himachal Pradesh (; ; "Snow-laden Mountain Province") is a state in the northern part of India. Situated in the Western Himalayas, it is one of the thirteen mountain states and is characterized by an extreme landscape featuring several peaks ...

. The Sikh population, which had gone as high as 19.8% in some Pakistani districts in 1941, dropped to 0.1% in Pakistan, and rose sharply in the districts assigned to India. However, they would still be a minority in the Punjab province of India, which remained a Hindu-majority province.

Sikh relationship with Punjab (via Oberoi)

Sikh historian

Harjot Singh Oberoi argues that, despite the historical linkages between Sikhs and Punjab, territory has never been a major element of Sikh self-definition. He makes the case that the attachment of Punjab with Sikhism is a recent phenomenon, stemming from the 1940s. Historically,

Sikhism

Sikhism (), also known as Sikhi ( pa, ਸਿੱਖੀ ', , from pa, ਸਿੱਖ, lit=disciple', 'seeker', or 'learner, translit=Sikh, label=none),''Sikhism'' (commonly known as ''Sikhī'') originated from the word ''Sikh'', which comes fro ...

has been pan-Indian, with the

Guru Granth Sahib

The Guru Granth Sahib ( pa, ਗੁਰੂ ਗ੍ਰੰਥ ਸਾਹਿਬ, ) is the central holy religious scripture of Sikhism, regarded by Sikhs as the final, sovereign and Guru Maneyo Granth, eternal Guru following the lineage of the Sikh gur ...

(the main scripture of Sikhism) drawing from works of saints in both North and South India, while several major seats in Sikhism (e.g.

Nankana Sahib

Nankana Sahib () is a city and capital of Nankana Sahib District in the Punjab province of Pakistan. It is named after the first Guru of the Sikhs, Guru Nanak, who was born in the city and first began preaching here. Nankana Sahib is the most ...

in Pakistan,

Takht Sri Patna Sahib

Takhat Sri Patna Sahib also known as Takhat Sri Harimandir Ji, Patna Sahib, is a one of the five Takhats of the Sikhs, located in Patna, Bihar, India. The construction of the Takhat was commissioned by Maharaja Ranjit Singh in the 18th ce ...

in

Bihar

Bihar (; ) is a state in eastern India. It is the 2nd largest state by population in 2019, 12th largest by area of , and 14th largest by GDP in 2021. Bihar borders Uttar Pradesh to its west, Nepal to the north, the northern part of West Be ...

, and

Hazur Sahib

Hazur Sahib (; ), also known as Takht Sachkhand Sri Hazur Abchalnagar Sahib, is one of the five takhts in Sikhism. The gurdwara was built between 1832 and 1837 by Maharaja Ranjit Singh (1780–1839). It is located on the banks of the Godavari ...

in

Maharashtra

Maharashtra (; , abbr. MH or Maha) is a states and union territories of India, state in the western India, western peninsular region of India occupying a substantial portion of the Deccan Plateau. Maharashtra is the List of states and union te ...

) are located outside of Punjab.

Oberoi makes the case that Sikh leaders in the late 1930s and 1940s realized that the dominance of

Muslims in Pakistan

Islam is the largest and the state religion of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan. As much as 90% of the population follows Sunni Islam. Most Pakistani Sunni Muslims belong to the Hanafi school of jurisprudence, which is represented by the Ba ...

and of

Hindus in India was imminent. To justify a separate Sikh state within the Punjab, Sikh leaders started to mobilize meta-commentaries and signs to argue that Punjab belonged to Sikhs and Sikhs belong to Punjab. This began the territorialization of the Sikh community.

This territorialization of the Sikh community would be formalized in March 1946, when the Sikh political party of

Akali Dal

The Shiromani Akali Dal (SAD) (translation: ''Supreme Akali Party'') is a centre-right sikh-centric state political party in Punjab, India. The party is the second-oldest in India, after Congress, being founded in 1920. Although there are man ...

passed a resolution proclaiming the natural association of Punjab and the Sikh religious community. Oberoi argues that despite having its beginnings in the early 20th century, Khalistan as a separatist movement was never a major issue until the late 1970s and 1980s when it began to militarize.

1950s to 1970s

There are two distinct narratives about the origins of the calls for a sovereign Khalistan. One refers to the events within India itself, while the other privileges the role of the

Sikh diaspora

The Sikh diaspora is the modern Sikh migration from the traditional area of the Punjab region of India. Sikhism is a religion, the Punjab region of India being the historic homeland of Sikhism. The Sikh diaspora is largely a subset of the Pun ...

. Both of these narratives vary in the form of governance proposed for this state (e.g.

theocracy

Theocracy is a form of government in which one or more deity, deities are recognized as supreme ruling authorities, giving divine guidance to human intermediaries who manage the government's daily affairs.

Etymology

The word theocracy origina ...

vs

democracy

Democracy (From grc, δημοκρατία, dēmokratía, ''dēmos'' 'people' and ''kratos'' 'rule') is a form of government in which the people have the authority to deliberate and decide legislation (" direct democracy"), or to choose gov ...

) as well as the proposed name (i.e. Sikhistan vs Khalistan). Even the precise geographical borders of the proposed state differs among them although it was generally imagined to be carved out from one of various historical constructions of the Punjab.

Emergence in India

Established on 14 December 1920,

Shiromani Akali Dal

The Shiromani Akali Dal (SAD) (translation: ''Supreme Akali Party'') is a centre-right sikh-centric state political party in Punjab, India. The party is the second-oldest in India, after Congress, being founded in 1920. Although there are many ...

was a Sikh political party that sought to form a government in Punjab.

[Jetly, Rajshree. 2006. "The Khalistan Movement in India: The Interplay of Politics and State Power." ''International Review of Modern Sociology'' 34(1):61–62. .]

Following the 1947 independence of India, the

Punjabi Suba movement

The Punjabi Suba movement was a long-drawn political agitation, launched by Punjabi speaking people (mostly Sikhs) demanding the creation of a Punjabi Suba, or Punjabi-speaking state, in the post-independence Indian state of East Punjab. Led by ...

, led by the Akali Dal, sought the creation of a province (''

suba

Suba may refer to:

Groups of people

*Suba people (Kenya), a people of Kenya

**Suba language

*Suba people (Tanzania), a people of Tanzania

* Subha (writers), alternatively spelt Suba, Indian writer duo

Individual people

*Suba (musician), Serbian- ...

'') for

Punjabi people

The Punjabis ( Punjabi: ; ਪੰਜਾਬੀ ; romanised as Panjābīs), are an Indo-Aryan ethnolinguistic group associated with the Punjab region of the Indian subcontinent, comprising areas of eastern Pakistan and northwestern India. The ...

. The Akali Dal's maximal position of demands was a

sovereign state

A sovereign state or sovereign country, is a polity, political entity represented by one central government that has supreme legitimate authority over territory. International law defines sovereign states as having a permanent population, defin ...

(i.e. Khalistan), while its minimal position was to have an

autonomous state

An autonomous administrative division (also referred to as an autonomous area, entity, unit, region, subdivision, or territory) is a subnational administrative division or internal territory of a sovereign state that has a degree of autonomy— ...

within India. The issues raised during the Punjabi Suba movement were later used as a premise for the creation of a separate Sikh country by proponents of Khalistan.

As the religious-based partition of India led to much bloodshed, the Indian government initially rejected the demand, concerned that creating a Punjabi-majority state would effectively mean yet again creating a state based on religious grounds.

However, in September 1966, the

Union Government

The Government of India (ISO: ; often abbreviated as GoI), known as the Union Government or Central Government but often simply as the Centre, is the national government of the Republic of India, a federal democracy located in South Asia, c ...

led by

Indira Gandhi

Indira Priyadarshini Gandhi (; Given name, ''née'' Nehru; 19 November 1917 – 31 October 1984) was an Indian politician and a central figure of the Indian National Congress. She was elected as third prime minister of India in 1966 ...

accepted the demand. On 7 September 1966, the

''Punjab Reorganisation Act'' was passed in Parliament, implemented with effect beginning 1 November 1966. Accordingly, Punjab was divided into the state of Punjab and

Haryana

Haryana (; ) is an Indian state located in the northern part of the country. It was carved out of the former state of East Punjab on 1 Nov 1966 on a linguistic basis. It is ranked 21st in terms of area, with less than 1.4% () of India's land ar ...

, with certain areas to

Himachal Pradesh

Himachal Pradesh (; ; "Snow-laden Mountain Province") is a state in the northern part of India. Situated in the Western Himalayas, it is one of the thirteen mountain states and is characterized by an extreme landscape featuring several peaks ...

.

Chandigarh

Chandigarh () is a planned city in India. Chandigarh is bordered by the state of Punjab to the west and the south, and by the state of Haryana to the east. It constitutes the bulk of the Chandigarh Capital Region or Greater Chandigarh, which al ...

was made a centrally administered

Union territory.

Anandpur Resolution

As Punjab and Haryana now shared the capital of Chandigarh, resentment was felt among Sikhs in Punjab.

Adding further grievance, a canal system was put in place over the rivers of

Ravi Ravi may refer to:

People

* Ravi (name), including a list of people and characters with the name

* Ravi (composer) (1926–2012), Indian music director

* Ravi (Ivar Johansen) (born 1976), Norwegian musical artist

* Ravi (music director) (1926–201 ...

,

Beas

Beas is a riverfront town in the Amritsar district of the Indian States and union territories of India, state of Punjab, India, Punjab. Beas lies on the banks of the Beas River. Beas town is mostly located in revenue boundary of Budha Theh wit ...

, and

Sutlej

The Sutlej or Satluj River () is the longest of the five rivers that flow through the historic crossroads region of Punjab in northern India and Pakistan. The Sutlej River is also known as ''Satadru''. It is the easternmost tributary of the Ind ...

, which flowed through Punjab, in order for water to also reach Haryana and

Rajasthan

Rajasthan (; lit. 'Land of Kings') is a state in northern India. It covers or 10.4 per cent of India's total geographical area. It is the largest Indian state by area and the seventh largest by population. It is on India's northwestern si ...

. As result, Punjab would only receive 23% of the water while the rest would go to the two other states. The fact that the issue would not be revisited brought on additional turmoil to Sikh resentment against Congress.

The

Akali Dal

The Shiromani Akali Dal (SAD) (translation: ''Supreme Akali Party'') is a centre-right sikh-centric state political party in Punjab, India. The party is the second-oldest in India, after Congress, being founded in 1920. Although there are man ...

was defeated in the

1972 Punjab elections.

To regain public appeal, the party put forward the

Anandpur Sahib Resolution

The Anandpur Sahib Resolution was a statement with a list of demands made by the Punjabi Sikh political party, the Shiromani Akali Dal, in 1973.

Presentation in 1973

After the tenure of chief minister Gurnam Singh in the Punjab, newly demarcated ...

in 1973 to demand radical devolution of power and further autonomy to Punjab. The resolution document included both religious and political issues, asking for the recognition of Sikhism as a religion separate from Hinduism, as well as the transfer of

Chandigarh

Chandigarh () is a planned city in India. Chandigarh is bordered by the state of Punjab to the west and the south, and by the state of Haryana to the east. It constitutes the bulk of the Chandigarh Capital Region or Greater Chandigarh, which al ...

and certain other areas to Punjab. It also demanded that power be radically devolved from the central to state governments.

The document was largely forgotten for some time after its adoption until gaining attention in the following decade. In 1982, the Akali Dal and

Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale

Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale (; born Jarnail Singh Brar; 2 June 1947– 6 June 1984) was a militant leader of the Sikh organization Damdami Taksal. He was not an advocate of Khalistan. "Bhindranwale was not an outspoken supporter of Khalistan, ...

joined hands to launch the Dharam Yudh Morcha in order to implement the resolution. Thousands of people joined the movement, feeling that it represented a real solution to such demands as larger shares of water for irrigation and the return of Chandigarh to Punjab.

Emergence in the diaspora

According to the 'events outside India' narrative, particularly after 1971, the notion of a sovereign and independent state of Khalistan began to popularize among Sikhs in

North America

North America is a continent in the Northern Hemisphere and almost entirely within the Western Hemisphere. It is bordered to the north by the Arctic Ocean, to the east by the Atlantic Ocean, to the southeast by South America and the Car ...

and

Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a Continent#Subcontinents, subcontinent of Eurasia ...

. One such account is provided by the Khalistan Council which had moorings in

West London

West London is the western part of London, England, north of the River Thames, west of the City of London, and extending to the Greater London boundary.

The term is used to differentiate the area from the other parts of London: North London ...

, where the Khalistan movement is said to have launched in 1970.

Davinder Singh Parmar migrated to London in 1954. According to Parmar, his first pro-Khalistan meeting was attended by less than 20 people and he was labelled as a madman, receiving only one person's support. Parmar continued his efforts despite the lack of a following, eventually raising the Khalistani flag in

Birmingham

Birmingham ( ) is a city and metropolitan borough in the metropolitan county of West Midlands in England. It is the second-largest city in the United Kingdom with a population of 1.145 million in the city proper, 2.92 million in the West ...

in the 1970s. In 1969, two years after losing the Punjab Assembly elections, Indian politician

Jagjit Singh Chohan

Jagjit Singh Chohan was the founder of the Khalistan movement that sought to create an independent Sikh state in the Punjab region of India and Pakistan.

Politics

Jagjit Singh grew up in Tanda in Punjab's Hoshiarpur district, about 180 km ...

moved to the

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and North ...

to start his campaign for the creation of Khalistan.

Apart from Punjab, Himachal, and Haryana, Chohan's proposal of Khalistan also included parts of

Rajasthan

Rajasthan (; lit. 'Land of Kings') is a state in northern India. It covers or 10.4 per cent of India's total geographical area. It is the largest Indian state by area and the seventh largest by population. It is on India's northwestern si ...

state.

Parmar and Chohan would meet in 1970 and formally announce the Khalistan movement at a London press conference, though being largely dismissed by the community as fanatical fringe without any support.

Chohan in Pakistan and US

Following the

Indo-Pakistani War of 1971

The Indo-Pakistani War of 1971 was a military confrontation between India and Pakistan that occurred during the Bangladesh Liberation War in East Pakistan from 3 December 1971 until the

Pakistani capitulation in Dhaka on 16 Decem ...

, Chohan visited

Pakistan

Pakistan ( ur, ), officially the Islamic Republic of Pakistan ( ur, , label=none), is a country in South Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, fifth-most populous country, with a population of almost 24 ...

as a guest of such leaders as

Chaudhuri Zahoor Elahi. Visiting

Nankana Sahib

Nankana Sahib () is a city and capital of Nankana Sahib District in the Punjab province of Pakistan. It is named after the first Guru of the Sikhs, Guru Nanak, who was born in the city and first began preaching here. Nankana Sahib is the most ...

and several historical gurdwaras in Pakistan, Chohan utilized the opportunity to spread the notion of an independent Sikh state. Widely publicized by Pakistani press, the extensive coverage of his remarks introduced the international community, including those in India, to the demand of Khalistan for the first time. Though lacking public support, the term ''Khalistan'' became more and more recognizable. According to Chohan, during a talk with Prime Minister

Zulfikar Ali Bhutto

Zulfikar (or Zulfiqar) Ali Bhutto ( ur, , sd, ذوالفقار علي ڀٽو; 5 January 1928 – 4 April 1979), also known as Quaid-e-Awam ("the People's Leader"), was a Pakistani barrister, politician and statesman who served as the fourth ...

of Pakistan, Bhutto had proposed to make Nankana Sahib the capital of Khalistan.

On 13 October 1971, visiting the United States at the invitation of his supporters in the

Sikh diaspora

The Sikh diaspora is the modern Sikh migration from the traditional area of the Punjab region of India. Sikhism is a religion, the Punjab region of India being the historic homeland of Sikhism. The Sikh diaspora is largely a subset of the Pun ...

, Chohan placed an advertisement in the ''

New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid d ...

'' proclaiming an independent Sikh state. Such promotion enabled him to collect millions of dollars from the diaspora,

eventually leading to charges in India relating to

sedition

Sedition is overt conduct, such as speech and organization, that tends toward rebellion against the established order. Sedition often includes subversion of a constitution and incitement of discontent toward, or insurrection against, estab ...

and other crimes in connection with his separatist activities.

Khalistan National Council

After returning to India in 1977, Chohan travelled to Britain in 1979. There, he would establish the

Khalistan National Council

The Khalistan movement is a Sikh separatist movement seeking to create a homeland for Sikhs by establishing a sovereign state, called Khālistān (' Land of the Khalsa'), in the Punjab region. The proposed state would consist of land that cur ...

, declaring its formation at

Anandpur Sahib

Anandpur Sahib, sometimes referred to simply as Anandpur (lit. "city of bliss"), is a city in Rupnagar district (Ropar), on the edge of Shivalik Hills, in the Indian state of Punjab. Located near the Sutlej River, the city is one of the most s ...

on 12 April 1980. Chohan designated himself as President of the Council and Balbir Singh Sandhu as its Secretary General.

In May 1980, Chohan travelled to

London

London is the capital and largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary down to the North Sea, and has been a majo ...

to announce the formation of Khalistan. A similar announcement was made in

Amritsar

Amritsar (), historically also known as Rāmdāspur and colloquially as ''Ambarsar'', is the second largest city in the Indian state of Punjab, after Ludhiana. It is a major cultural, transportation and economic centre, located in the Majha r ...

by Sandhu, who released stamps and currency of Khalistan. Operating from a building termed "Khalistan House", Chohan named a Cabinet and declared himself president of the "Republic of Khalistan," issuing symbolic Khalistan 'passports,' 'postage stamps,' and 'Khalistan dollars.' Moreover, embassies in Britain and other European countries were opened by Chohan.

It is reported that, with the support of a wealthy Californian peach magnate, Chohan opened an Ecuadorian bank account to further support his operation.

As well as maintaining contacts among various groups in Canada, the US, and Germany, Chohan kept in contact with the Sikh leader

Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale

Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale (; born Jarnail Singh Brar; 2 June 1947– 6 June 1984) was a militant leader of the Sikh organization Damdami Taksal. He was not an advocate of Khalistan. "Bhindranwale was not an outspoken supporter of Khalistan, ...

who was campaigning for a

theocratic

Theocracy is a form of government in which one or more deities are recognized as supreme ruling authorities, giving divine guidance to human intermediaries who manage the government's daily affairs.

Etymology

The word theocracy originates fro ...

Sikh homeland.

The globalized Sikh diaspora invested efforts and resources for Khalistan, but the Khalistan movement remained nearly invisible on the global political scene until the Operation Blue Star of June 1984.

R&AW

In later disclosures from former

R&AW

The Research and Analysis Wing (abbreviated R&AW; hi, ) is the foreign intelligence agency of India. The agency's primary function is gathering foreign intelligence, counter-terrorism, counter-proliferation, advising Indian policymakers, an ...

special secretary G.B.S. Sidhu, R&AW itself helped "build the Khalistan legend," actively participated in the planning of

Operation Blue Star

Operation Blue Star was the codename of a military operation which was carried out by Indian security forces between 1 and 10 June 1984 in order to remove Damdami Taksal leader Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale and his followers from the buildings of ...

. While posted in

Ottawa

Ottawa (, ; Canadian French: ) is the capital city of Canada. It is located at the confluence of the Ottawa River and the Rideau River in the southern portion of the province of Ontario. Ottawa borders Gatineau, Quebec, and forms the core ...

, Canada in 1976 to look into the "Khalistan problem" among the Sikh diaspora, Sidhu found "nothing amiss" during the three years he was there,

stating that "Delhi was unnecessarily making a mountain of a molehill where none existed," that the agency created seven posts in West Europe and North America in 1981 to counter non-existent Khalistan activities, and that the deployed officers were "not always familiar with the Sikhs or the Punjab issue."

[ He described the secessionist movement as a "chimera" until the army operation, after which the insurgency would start.][ According to a New York Times article written just a few weeks after the operation, "Before the raid on the Golden Temple, neither the Government nor anyone else appeared to put much credence in the Khalistan movement. Mr. Bhindranwale himself said many times that he was not seeking an independent country for Sikhs, merely greater autonomy for Punjab within the Indian Union....One possible explanation advanced for the Government's raising of the Khalistan question is that it needs to take every opportunity to justify the killing in Amritsar and the invasion of the Sikhs' holiest shrine."][

]

Late 1970s to 1983

Delhi Asian Games (1982)

The Akali leaders, having planned to announce a victory for Dharam Yudh Morcha, were outraged by the changes to the agreed-upon settlement. In November 1982, Akali leader Harchand Singh Longowal

Sant Harchand Singh Longowal (2 January 1932 – 20 August 1985) was the President of the Akali Dal during the Punjab insurgency of the 1980s. He had signed the Punjab accord, also known as the Rajiv-Longowal Accord along with Rajiv Gandhi on 2 ...

announced that the party would disrupt the 9th annual Asian Games by sending groups of Akali workers to Delhi to intentionally get arrested. Following negotiations between the Akali Dal and the government failed at the last moment due to disagreements regarding the transfer of areas between Punjab and Haryana.Bhajan Lal

Bhajanlal Bishnoi (6 October 1930 – 3 June 2011) was a politician and three-time chief minister of the Indian state of Haryana. He became the Chief Minister for the first time in 1979, was re-elected in 1982, and became the chief minister for ...

, Chief Minister of Haryana and member of the INC

Inc. or inc may refer to:

* Incorporation (business), as a suffix indicating a corporation

* ''Inc.'' (magazine), an American business magazine

* Inc. No World, a Los Angeles-based band

* Indian National Congress, a political party in India

* I ...

party, responded by sealing the Delhi-Punjab border,Major General

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of a ...

Shabeg Singh

Shabeg Singh, PVSM, AVSM (1925–1984), was a Sikh resistance officer who had previously served in the Indian Army (Related: Dharam Yudh Morcha, Battle of Amritsar 1984, Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale).

During his military service in the Indian A ...

who subsequently became Bhindranwale's military advisor.

1984

Increasing militant activity

Widespread murders by followers of Bhindranwale occurred in 1980s' Punjab. Armed Khalistani militants of this period described themselves as ''kharku'',[Ghosh, Srikanta. 1997. ''Indian Democracy Derailed – Politics and Politicians.'' APH Publishing. . p. 95.] One such murder was that of DIG

Digging, also referred to as excavation, is the process of using some implement such as claws, hands, manual tools or heavy equipment, to remove material from a solid surface, usually soil, sand or rock (geology), rock on the surface of Earth. Di ...

Avtar Singh Atwal

Avtar Singh Atwal was a Deputy Inspector General in Punjab Police. He was murdered by a follower of Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale at the steps of Golden temple while coming out after prayers on 25 April 1983 His murder set in motion a chain of ev ...

, killed on 25 April 1983 at the gate of the Darbar Sahib,[Sharma, Puneet, dir. 2013.]

Operation Blue Star and the assassination of Indira Gandhi

(TV episode). ''Pradhanmantri

''Pradhanmantri'' () is an Indian television political documentary series, hosted by actor-director Shekhar Kapur on Hindi news channel ABP News. It premiered on 13 July 2013. It aimed to bring to the audience never-seen-before facts of Indian ...

'' Ep. 14. India: ABP News

ABP News is an Indian Hindi-language free-to-air television news channel owned by ABP Group. The news channel was launched in 1998 originally as STAR News before being acquired by ABP Group. It won the Best Hindi News Channel award in the 21st ...

. – via ABP News Hindi on YouTube

YouTube is a global online video platform, online video sharing and social media, social media platform headquartered in San Bruno, California. It was launched on February 14, 2005, by Steve Chen, Chad Hurley, and Jawed Karim. It is owned by ...

.[Verma, Arvind. 2003.]

Terrorist Victimization: Prevention, Control, and Recovery, Case Studies from India

" pp. 89–98 in ''Meeting the Challenges of Global Terrorism: Prevention, Control, and Recovery'', edited by D. K. Das and P. C. Kratcoski. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books

Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group is an independent publishing house founded in 1949. Under several imprints, the company offers scholarly books for the academic market, as well as trade books. The company also owns the book distributing compa ...

.

p. 89

Though it was common knowledge that those responsible for such bombings and murders were taking shelter in gurdwara

A gurdwara (sometimes written as gurudwara) (Gurmukhi: ਗੁਰਦੁਆਰਾ ''guradu'ārā'', meaning "Door to the Guru") is a place of assembly and worship for Sikhs. Sikhs also refer to gurdwaras as ''Gurdwara Sahib''. People from all faiths ...

s, the INC

Inc. or inc may refer to:

* Incorporation (business), as a suffix indicating a corporation

* ''Inc.'' (magazine), an American business magazine

* Inc. No World, a Los Angeles-based band

* Indian National Congress, a political party in India

* I ...

Government of India

The Government of India (ISO: ; often abbreviated as GoI), known as the Union Government or Central Government but often simply as the Centre, is the national government of the Republic of India, a federal democracy located in South Asia, c ...

declared that it could not enter these places of worship, for the fear of hurting Sikh sentiments.Prime Minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister is not ...

Indira Gandhi

Indira Priyadarshini Gandhi (; Given name, ''née'' Nehru; 19 November 1917 – 31 October 1984) was an Indian politician and a central figure of the Indian National Congress. She was elected as third prime minister of India in 1966 ...

, the Government would choose not to take action.[Sisson, Mary. 2011. "Sikh Terrorism." pp. 544–545 in ''The Sage Encyclopedia of Terrorism'' (2nd ed.), edited by G. Martin. Thousand Oaks, CA: ]Sage Publications

SAGE Publishing, formerly SAGE Publications, is an American independent publishing company founded in 1965 in New York by Sara Miller McCune and now based in Newbury Park, California.

It publishes more than 1,000 journals, more than 800 books ...

. . .

Constitutional issues

The Akali Dal began more agitation in February 1984, protesting against Article 25, clause (2)(b), of the Indian Constitution

The Constitution of India ( IAST: ) is the supreme law of India. The document lays down the framework that demarcates fundamental political code, structure, procedures, powers, and duties of government institutions and sets out fundamental r ...

, which ambiguously explains that "the reference to Hindus shall be construed as including a reference to persons professing the Sikh, Jaina

JAINA is an acronym for the Federation of Jain Associations in North America, an umbrella organizations to preserve, practice, and promote Jainism in USA and Canada. It was founded in 1981 and formalized in 1983. Among Jain organization it is ...

, or Buddhist

Buddhism ( , ), also known as Buddha Dharma and Dharmavinaya (), is an Indian religion or philosophical tradition based on teachings attributed to the Buddha. It originated in northern India as a -movement in the 5th century BCE, and ...

religion," while also implicitly recognizing Sikhism as a separate religion: "the wearing and carrying of kripans 'sic''.html" ;"title="sic.html" ;"title="'sic">'sic''">sic.html" ;"title="'sic">'sic''shall be deemed to be included in the profession of the Sikh religion."[Sharma, Mool Chand, and A.K. Sharma, eds. 2004.]

Discrimination Based on Religion

" pp. 108–110 in ''Discrimination Based on Sex, Caste, Religion, and Disability''. New Delhi: National Council for Teacher Education

Archived

from the original on 2 June 2010. Retrieved 17 May 2020. Even today, this clause is deemed offensive by many religious minorities in India due to its failure to recognise such religions separately under the constitution.Special Marriage Act, 1954

The Special Marriage Act, 1954 is an Act of the Parliament of India with provision for civil marriage (or "registered marriage") for people of India and all Indian nationals in foreign countries, irrelevant of the religion or faith followed b ...

'' or the ''Hindu Marriage Act, 1955

The Hindu Marriage Act is an Act of the Parliament of India enacted in 1955 which was passed on 18th of May. Three other important acts were also enacted as part of the Hindu Code Bills during this time: the Hindu Succession Act (1956), the Hind ...

''. The Akalis demanded replacement of such rules with laws specific to Sikhism

Sikhism (), also known as Sikhi ( pa, ਸਿੱਖੀ ', , from pa, ਸਿੱਖ, lit=disciple', 'seeker', or 'learner, translit=Sikh, label=none),''Sikhism'' (commonly known as ''Sikhī'') originated from the word ''Sikh'', which comes fro ...

.

Operation Blue Star

Operation Blue Star

Operation Blue Star was the codename of a military operation which was carried out by Indian security forces between 1 and 10 June 1984 in order to remove Damdami Taksal leader Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale and his followers from the buildings of ...

was an Indian military operation ordered by Prime Minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister is not ...

Indira Gandhi

Indira Priyadarshini Gandhi (; Given name, ''née'' Nehru; 19 November 1917 – 31 October 1984) was an Indian politician and a central figure of the Indian National Congress. She was elected as third prime minister of India in 1966 ...

, between 1 and 8 June 1984, to remove militant religious leader Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale

Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale (; born Jarnail Singh Brar; 2 June 1947– 6 June 1984) was a militant leader of the Sikh organization Damdami Taksal. He was not an advocate of Khalistan. "Bhindranwale was not an outspoken supporter of Khalistan, ...

and his armed followers from the buildings of the Harmandir Sahib complex (aka the Golden Temple) in Amritsar

Amritsar (), historically also known as Rāmdāspur and colloquially as ''Ambarsar'', is the second largest city in the Indian state of Punjab, after Ludhiana. It is a major cultural, transportation and economic centre, located in the Majha r ...

, Punjab

Punjab (; Punjabi: پنجاب ; ਪੰਜਾਬ ; ; also romanised as ''Panjāb'' or ''Panj-Āb'') is a geopolitical, cultural, and historical region in South Asia, specifically in the northern part of the Indian subcontinent, comprising ...

the most sacred site in Sikhism.Akali Dal

The Shiromani Akali Dal (SAD) (translation: ''Supreme Akali Party'') is a centre-right sikh-centric state political party in Punjab, India. The party is the second-oldest in India, after Congress, being founded in 1920. Although there are man ...

President Harchand Singh Longowal

Sant Harchand Singh Longowal (2 January 1932 – 20 August 1985) was the President of the Akali Dal during the Punjab insurgency of the 1980s. He had signed the Punjab accord, also known as the Rajiv-Longowal Accord along with Rajiv Gandhi on 2 ...

had invited Bhindranwale to take up residence at the sacred temple complex, which the government would allege that Bhindranwale would later make into an armoury

An arsenal is a place where arms and ammunition are made, maintained and repaired, stored, or issued, in any combination, whether privately or publicly owned. Arsenal and armoury (British English) or armory (American English) are most ...

and headquarters for his armed uprising.Hindus

Hindus (; ) are people who religiously adhere to Hinduism.Jeffery D. Long (2007), A Vision for Hinduism, IB Tauris, , pages 35–37 Historically, the term has also been used as a geographical, cultural, and later religious identifier for ...

and Nirankari

Nirankari ( pa, ਨਿਰੰਕਾਰੀ, ''lit.'' "formless one") is a sect of Sikhism.Harbans Singh, Editor-in-Chief (201Nirankaris Encyclopedia of Sikhism Volume III, Punjabi University, Patiala, pages 234–235 It was a reform movement found ...

s, as well as 39 Sikhs opposed to Bhindranwale, while a total of 410 dead and 1,180 injured came as result of Khalistani violence and riots.[ Tully, Mark, and Satish Jacob. 1985. ]

Amritsar: Mrs. Gandhi's Last Battle

' (5th ed.). London: Jonathan Cape

Jonathan Cape is a London publishing firm founded in 1921 by Herbert Jonathan Cape, who was head of the firm until his death in 1960.

Cape and his business partner Wren Howard set up the publishing house in 1921. They established a reputation ...

p. 147

As negotiations held with Bhindranwale and his supporters proved unsuccessful, Indira Gandhi ordered the Indian Army

The Indian Army is the land-based branch and the largest component of the Indian Armed Forces. The President of India is the Supreme Commander of the Indian Army, and its professional head is the Chief of Army Staff (COAS), who is a four- ...

to launch Operation Blue Star. Along with the Army, the operation would involve Central Reserve Police Force

The Central Reserve Police Force (CRPF) is a federal police organisation in India under the authority of the Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA) of the Government of India. It is one among the Central Armed Police Forces. The CRPF's primary role li ...

, Border Security Force

The Border Security Force (BSF) is India's border guarding organisation on its border with Pakistan and Bangladesh. It is one of the seven Central Armed Police Forces (CAPF) of India, and was raised in the wake of the 1965 war on 1 December 1 ...

, and Punjab Police. Army units led by Lt. Gen.

Lieutenant general (Lt Gen, LTG and similar) is a three-star rank, three-star military rank (NATO code OF-8) used in many countries. The rank traces its origins to the Middle Ages, where the title of lieutenant general was held by the second-in ...

Kuldip Singh Brar

Lieutenant General Kuldip Singh Brar, PVSM, AVSM, VrC (born 1934) is a retired Indian Army officer, who was involved in the Indo-Pakistani War of 1971. As a major general, he commanded Operation Blue Star.

Early days

K S Brar was born in 1934 ...

(a Sikh), surrounded the temple complex on 3 June 1984. Just before the commencement of the operation, Lt. Gen. Brar addressed the soldiers:[ Gates, Scott, and Kaushik Roy. 2016.]

Insurgency and Counterinsurgency in Punjab

" pp. 163–175 in ''Unconventional Warfare in South Asia: Shadow Warriors and Counterinsurgency''. Surrey: Ashgate

Ashgate Publishing was an academic book and journal publisher based in Farnham (Surrey, United Kingdom). It was established in 1967 and specialised in the social sciences, arts, humanities and professional practice. It had an American office in ...

. . p. 167.

However, none of the soldiers opted out, including many "Sikh officers, junior commissioned officers and other ranks."public address system

A public address system (or PA system) is an electronic system comprising microphones, amplifiers, loudspeakers, and related equipment. It increases the apparent volume (loudness) of a human voice, musical instrument, or other acoustic sound sou ...

, the Army repeatedly demanded the militants to surrender, asking them to at least allow pilgrims to leave the temple premises before commencing battle.

Nothing happened until 7:00 PM (IST

Ist or IST may refer to:

Information Science and Technology

* Bachelor's or Master's degree in Information Science and Technology

* Graduate School / Faculty of Information Science and Technology, Hokkaido University, Japan

* Graduate School ...

).tank

A tank is an armoured fighting vehicle intended as a primary offensive weapon in front-line ground combat. Tank designs are a balance of heavy firepower, strong armour, and good battlefield mobility provided by tracks and a powerful engin ...

s and heavy artillery

Artillery is a class of heavy military ranged weapons that launch munitions far beyond the range and power of infantry firearms. Early artillery development focused on the ability to breach defensive walls and fortifications during siege ...

, had grossly underestimated the firepower possessed by the militants, who attacked with anti-tank

Anti-tank warfare originated from the need to develop technology and tactics to destroy tanks during World War I. Since the Triple Entente deployed the first tanks in 1916, the German Empire developed the first anti-tank weapons. The first deve ...

and machine-gun

A machine gun is a fully automatic, rifled autoloading firearm designed for sustained direct fire with rifle cartridges. Other automatic firearms such as automatic shotguns and automatic rifles (including assault rifles and battle rifles) ar ...

fire from the heavily fortified Akal Takht

The Akal Takht ("Throne of the Timeless One") is one of five takhts (seats of power) of the Sikhs. It is located in the Darbar Sahib (Golden Temple) complex in Amritsar, Punjab, India. The Akal Takht (originally called Akal Bunga) was built by ...

, and who possessed Chinese-made, rocket-propelled grenade launchers

A rocket-propelled grenade (RPG) is a shoulder-fired missile weapon that launches rockets equipped with an explosive warhead. Most RPGs can be carried by an individual soldier, and are frequently used as anti-tank weapons. These warheads are ...

with armour-piercing

Armour-piercing ammunition (AP) is a type of projectile designed to penetrate either body armour or vehicle armour.

From the 1860s to 1950s, a major application of armour-piercing projectiles was to defeat the thick armour carried on many warsh ...

capabilities. After a 24-hour shootout

A shootout, also called a firefight or gunfight, is a fight between armed combatants using firearms. The term can be used to describe any such fight, though it is typically used to describe those that do not involve military forces or only invo ...

, the army finally wrested control of the temple complex.

Bhindranwale was killed in the operation, while many of his followers managed to escape. Army casualty figures counted 83 dead and 249 injured. According to the official estimate presented by the Indian Government, the event resulted in a combined total of 493 militant and civilian casualties, as well as the apprehension of 1592 individuals.[India. 10 July 1984. "White Paper on the Punjab Agitation." New Delhi: Government of India Press. ]

p. 40

U.K. Foreign Secretary William Hague

William is a male given name of Germanic origin.Hanks, Hardcastle and Hodges, ''Oxford Dictionary of First Names'', Oxford University Press, 2nd edition, , p. 276. It became very popular in the English language after the Norman conquest of Engl ...

attributed high civilian casualties to the Indian Government's attempt at a full frontal assault on the militants, diverging from the recommendations provided by the U.K. Military.[Hague, William. 2014.]

Allegations of UK Involvement in the Indian Operation at Sri Harmandir Sahib, Amritsar 1984

" ( Policy paper). Available as

PDF

Retrieved 17 May 2020.

"The FCO files (Annex E) record the Indian Intelligence Co-ordinator telling a UK interlocutor, in the same time-frame as this public Indian report, that some time after the UK military adviser’s visit the Indian Army took over lead responsibility for the operation, the main concept behind the operation changed, and a frontal assault was attempted, which contributed to the large number of casualties on both sides."[Golden Temple attack: UK advised India but impact 'limited']

" ''BBC News

BBC News is an operational business division of the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) responsible for the gathering and broadcasting of news and current affairs in the UK and around the world. The department is the world's largest broadca ...

''. 7 June 2014. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

"The adviser suggested using an element of surprise, as well as helicopters, to try to keep casualty numbers low – features which were not part of the final operation, Mr Hague said." Opponents of Gandhi also criticised the operation for its excessive use of force. Lieutenant General Brar later stated that the Government had "no other recourse" due to a "complete breakdown" of the situation: state machinery was under the militants' control; declaration of Khalistan was imminent; and Pakistan

Pakistan ( ur, ), officially the Islamic Republic of Pakistan ( ur, , label=none), is a country in South Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, fifth-most populous country, with a population of almost 24 ...

would have come into the picture declaring its support for Khalistan.

Nonetheless, the operation did not crush Khalistani militancy, as it continued.

According to the Mitrokhin Archive

The "Mitrokhin Archive" is a collection of handwritten notes which were secretly made by the KGB archivist Vasili Mitrokhin during the thirty years in which he served as a KGB archivist in the foreign intelligence service and the First Chief Direc ...

, in 1982 the Soviets used a recruit in the New Delhi residency named “Agent S” who was close to Indira Gandhi as a major channel for providing her disinformation regarding Khalistan. Agent S provided Indira Gandhi with false documents purporting to show Pakistani involvement to create religious disturbances and allegedly initiate a Khalistan conspiracy. After Rajiv Gandhi

Rajiv Gandhi (; 20 August 1944 – 21 May 1991) was an Indian politician who served as the sixth prime minister of India from 1984 to 1989. He took office after the 1984 assassination of his mother, then Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, to beco ...

's visit to Moscow in 1983, the Soviets persuaded him that the US was engaged in secret support for the Sikhs. By 1984, according to Mitrokhin, the disinformation the Soviets provided had influenced Indira Gandhi to pursue Operation Blue Star.

Assassination of Indira Gandhi and anti-Sikh riots

On the morning of 31 October 1984,

On the morning of 31 October 1984, Indira Gandhi

Indira Priyadarshini Gandhi (; Given name, ''née'' Nehru; 19 November 1917 – 31 October 1984) was an Indian politician and a central figure of the Indian National Congress. She was elected as third prime minister of India in 1966 ...

was assassinated in New Delhi

New Delhi (, , ''Naī Dillī'') is the capital of India and a part of the National Capital Territory of Delhi (NCT). New Delhi is the seat of all three branches of the government of India, hosting the Rashtrapati Bhavan, Parliament House ...

by her two personal security guards Satwant Singh

Satwant Singh Bhakar (1962 – 6 January 1989) was one of the bodyguards, along with Beant Singh, who assassinated the Prime Minister of India, Indira Gandhi, at her New Delhi residence on 31 October 1984.

Assassination

The motivation for th ...

and Beant Singh, both Sikhs, in retaliation for Operation Blue Star

Operation Blue Star was the codename of a military operation which was carried out by Indian security forces between 1 and 10 June 1984 in order to remove Damdami Taksal leader Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale and his followers from the buildings of ...

. The assassination would trigger the 1984 anti-Sikh riots

The 1984 Anti-Sikh Riots, also known as the 1984 Sikh Massacre, was a series of organised pogroms against Sikhs in India following the assassination of Indira Gandhi by her Sikh bodyguards. Government estimates project that about 2,800 Sikhs ...

across North India

North India is a loosely defined region consisting of the northern part of India. The dominant geographical features of North India are the Indo-Gangetic Plain and the Himalayas, which demarcate the region from the Tibetan Plateau and Central ...

. While the ruling party, Indian National Congress

The Indian National Congress (INC), colloquially the Congress Party but often simply the Congress, is a political party in India with widespread roots. Founded in 1885, it was the first modern nationalist movement to emerge in the British Em ...

(INC), maintained that the violence was due to spontaneous riots, its critics have alleged that INC members themselves had planned a pogrom

A pogrom () is a violent riot incited with the aim of massacring or expelling an ethnic or religious group, particularly Jews. The term entered the English language from Russian to describe 19th- and 20th-century attacks on Jews in the Russia ...

against the Sikhs.[Guidry, John A., Michael D. Kennedy, and Mayer N. Zald, eds. 2000. Globalizations and Social Movements: Culture, Power, and the Transnational Public Sphere. Ann Arbor: ]University of Michigan Press

The University of Michigan Press is part of Michigan Publishing at the University of Michigan Library. It publishes 170 new titles each year in the humanities and social sciences. Titles from the press have earned numerous awards, including L ...

. . p. 319.

The Nanavati Commission

The Justice G.T. Nanavati commission was a one-man commission headed by Justice G.T. Nanavati, a retired Judge of the Supreme Court of India, appointed by the National Democratic Alliance (NDA) government in May 2000, to investigate the "k ...

, a special commission created to investigate the riots, concluded that INC leaders (including Jagdish Tytler

Jagdish Tytler (born Jagdish Kapoor; 17 August 1944) is an Indian politician and former Member of Parliament. He has held several government positions, the last being as Minister of State for Overseas Indian Affairs, a post from which he resigne ...

, H. K. L. Bhagat

Hari Krishan Lal Bhagat (4 April 1921 – 29 October 2005) was an Indian politician of the Congress party. He served as the Deputy Mayor and Mayor of Delhi, the chief whip of Delhi Pradesh Congress Committee (DPCC), and as a six-time MP and ...

, and Sajjan Kumar

Sajjan Kumar (born 23 September 1945) is an Indian politician. He was elected to the Lok Sabha, the lower house of the Parliament of India from Outer Delhi as a member of the Indian National Congress but resigned from the primary membership o ...

) had directly or indirectly taken a role in the rioting incidents.Union Minister

The Union Council of Ministers Article 58 of the ''Constitution of India'' is the principal executive organ of the Government of India, which is responsible for being the senior decision making body of the executive branch. It is chaired by t ...

Kamal Nath

Kamal Nath (born 18 November 1946) is an Indian politician who served as the 18th Chief Minister of Madhya Pradesh for approximately 15 months and resigned after a political crisis. He was the Leader of the Opposition in the Madhya Pradesh Legi ...

was accused of leading riots near Rakab Ganj, but was cleared due to lack of evidence.

1985 to present day

1985

Rajiv-Longowal Accord

Many Sikh and Hindu groups, as well as organisations not affiliated to any religion, have attempted to establish peace between the Khalistan proponents and the Government of India. Akalis continued to witness radicalization of Sikh politics, fearing disastrous consequences.Harchand Singh Longowal

Sant Harchand Singh Longowal (2 January 1932 – 20 August 1985) was the President of the Akali Dal during the Punjab insurgency of the 1980s. He had signed the Punjab accord, also known as the Rajiv-Longowal Accord along with Rajiv Gandhi on 2 ...

reinstated the head of the Akali Dal and pushed for a peace initiative that reiterated the importance of Hindu-Sikh amity, condemning Sikh extremist violence, therefore declaring that the Akali Dal was not in favor of Khalistan.

In 1985, The Government of India

The Government of India (ISO: ; often abbreviated as GoI), known as the Union Government or Central Government but often simply as the Centre, is the national government of the Republic of India, a federal democracy located in South Asia, c ...

attempted to seek a political solution to the grievances of the Sikhs through the Rajiv-Longowal Accord, which took place between Longowal and Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi

Rajiv Gandhi (; 20 August 1944 – 21 May 1991) was an Indian politician who served as the sixth prime minister of India from 1984 to 1989. He took office after the 1984 assassination of his mother, then Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, to beco ...

. The Accordrecognizing the religious, territorial, and economic demands of the Sikhs that were thought to be non-negotiable under Indira Gandhi's tenureagreed to establish commissions and independent tribunals in order to resolve the Chandigarh issue and the river dispute, laying the basis for Akali Dal's victory in the coming elections.

Air India Flight 182

Air India Flight 182

Air India Flight 182 was an Air India flight operating on the Montreal–London–Delhi–Bombay route. On 23 June 1985, it was operated using Boeing 747-237B registered ''VT-EFO''. It disintegrated in mid-air en route from Montreal to Lond ...

was an Air India

Air India is the flag carrier airline of India, headquartered at New Delhi. It is owned by Talace Private Limited, a Special-Purpose Vehicle (SPV) of Tata Sons, after Air India Limited's former owner, the Government of India, completed the sa ...

flight operating on the Montréal

Montreal ( ; officially Montréal, ) is the second-most populous city in Canada and most populous city in the Canadian province of Quebec. Founded in 1642 as '' Ville-Marie'', or "City of Mary", it is named after Mount Royal, the triple-p ...

-London

London is the capital and largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary down to the North Sea, and has been a majo ...

-Delhi

Delhi, officially the National Capital Territory (NCT) of Delhi, is a city and a union territory of India containing New Delhi, the capital of India. Straddling the Yamuna river, primarily its western or right bank, Delhi shares borders w ...

-Bombay

Mumbai (, ; also known as Bombay — the official name until 1995) is the capital city of the Indian state of Maharashtra and the ''de facto'' financial centre of India. According to the United Nations, as of 2018, Mumbai is the second- ...

route. On 23 June 1985, a Boeing 747

The Boeing 747 is a large, long-range wide-body airliner designed and manufactured by Boeing Commercial Airplanes in the United States between 1968 and 2022.

After introducing the 707 in October 1958, Pan Am wanted a jet times its size, t ...

operating on the route was blown up by a bomb mid-air off the coast of Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe, north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel (Grea ...

. A total of 329 people aboard were killed, 268 Canadian citizens, 27 British citizens and 24 Indian citizens, including the flight crew. On the same day, an explosion due to a luggage bomb was linked to the terrorist operation and occurred at the Narita Airport

Narita International Airport ( ja, 成田国際空港, Narita Kokusai Kūkō) , also known as Tokyo-Narita, formerly and originally known as , is one of two international airports serving the Greater Tokyo Area, the other one being Haneda Airport ...

in Tokyo, Japan, intended for Air India Flight 301, killing two baggage handlers. The entire event was inter-continental in scope, killing 331 people in total and affected five countries on different continents: Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by tot ...

, the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and North ...

, India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

, Japan

Japan ( ja, 日本, or , and formally , ''Nihonkoku'') is an island country in East Asia. It is situated in the northwest Pacific Ocean, and is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan, while extending from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north ...

, and Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe, north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel (Grea ...

.

The main suspects in the bombing were members of a Sikh

Sikhs ( or ; pa, ਸਿੱਖ, ' ) are people who adhere to Sikhism, Sikhism (Sikhi), a Monotheism, monotheistic religion that originated in the late 15th century in the Punjab region of the Indian subcontinent, based on the revelation of Gu ...

separatist group called the Babbar Khalsa

Babbar Khalsa International (BKI, pa, ਬੱਬਰ ਖ਼ਾਲਸਾ, ), better known as Babbar Khalsa, is an organisation whose main objective is to create an independent Sikh country, Khalistan. It operates in Canada, Germany and the United ...

, and other related groups who were at the time agitating for a separate Sikh state of Khalistan in Punjab, India

Punjab (; ) is a States and union territories of India, state in northern India. Forming part of the larger Punjab region of the Indian subcontinent, the state is bordered by the States and union territories of India, Indian states of Himachal ...

. In September 2007, the Canadian Commission of Inquiry investigated reports, initially disclosed in the Indian investigative news magazine ''Tehelka

''Tehelka'' (Hindi: Sensation) is an Indian news magazine known for its investigative journalism and sting operations. According to the British newspaper ''The Independent'', the ''Tehelka'' was founded by Tarun Tejpal, Aniruddha Bahal and a ...

'', that a hitherto unnamed person, Lakhbir Singh Rode

Lakhbir Singh Rode is a Khalistani separatist and the nephew of Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale.

He currently heads the International Sikh Youth Federation (ISYF), which has branches in over a dozen countries in western Europe and Canada. Rode is al ...

, had masterminded the explosions. However, in conclusion two separate Canadian inquiries officially determined that the mastermind behind the terrorist operation was in fact the Canadian, Talwinder Singh Parmar

Talwinder Singh Parmar (26 February 1944 – 15 October 1992) born in Kapurthala, Punjab, India was a sikh kharku. He was also the founder, leader, and Jathedar of Babbar Khalsa International, better known as Babbar Khalsa, a militant Sikh gro ...

.

Several men were arrested and tried for the Air India bombing. Inderjit Singh Reyat, a Canadian

Canadians (french: Canadiens) are people identified with the country of Canada. This connection may be residential, legal, historical or cultural. For most Canadians, many (or all) of these connections exist and are collectively the source of ...

national and member of the International Sikh Youth Federation

The International Sikh Youth Federation (ISYF) is a proscribed organisation that aims to establish an independent homeland for the Sikhs of India in Khalistan. It is banned as a terrorist organisation under Australian, European Union, Japane ...

who pleaded guilty in 2003 to manslaughter

Manslaughter is a common law legal term for homicide considered by law as less culpable than murder. The distinction between murder and manslaughter is sometimes said to have first been made by the ancient Athenian lawmaker Draco in the 7th cen ...

, would be the only person convicted in the case.Narita Airport

Narita International Airport ( ja, 成田国際空港, Narita Kokusai Kūkō) , also known as Tokyo-Narita, formerly and originally known as , is one of two international airports serving the Greater Tokyo Area, the other one being Haneda Airport ...

.

Late 1980s

In 1986, when the insurgency was at its peak, the Golden Temple was again occupied by militants belonging to the All India Sikh Students Federation

The All India Sikh Students Federation (AISSF), is a Sikh student organisation and political organisation in India. AISSF was formed in 1943. as the youth wing of the Akali Dal, which is a Sikh political party in the Indian Punjab.

Origin

Befor ...

and Damdami Taksal

The Damdamī Ṭaksāl is an orthodox Sikh cultural and educational organization, based in India. Its headquarters are located in the town of Mehta Chowk, approximately 40 km north of the city of Amritsar. It has been described as a seminary ...

. The militants called an assembly (Sarbat Khalsa

Sarbat Khalsa (lit. meaning ''all the Khalsa''; Punjabi: (Gurumukhi)), was a biannual deliberative assembly (on the same lines as a Parliament in a Direct Democracy) of the Sikhs held at Amritsar in Panjab during the 18th century. It literally t ...