Kenneth Dewar on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Vice-Admiral Kenneth Gilbert Balmain Dewar,

As Flag Captain to Admiral Collard, Dewar was technically Collard's chief staff officer as well as captain of ''Royal Oak''. A good working relationship between Dewar and the second-in-command of the battle squadron was necessary. Notwithstanding, Collard on occasion acted imperiously and tactlessly on his flagship, causing friction with Dewar and his executive officer, Commander Henry Martin Daniel, DSO. At a dance on the quarterdeck on 12 January 1928, Collard openly lambasted Royal Marine Bandmaster Percy Barnacle and allegedly said "I won't have a bugger like that in my ship" in the presence of ship's officers and guests. Dewar and Daniel accused Collard of "vindictive fault-finding" and openly humiliating and insulting them before their crew, referring to an incident involving Collard's disembarkation from the ship on 5 March where the admiral had openly said that he was "fed up with the ship"; Collard countercharged the two with failing to follow orders and treating him "worse than a midshipman".

Dewar and Daniel, feeling that morale was sinking due to these public displays, wrote letters of complaint which were given to Collard on 10 March, on the eve of a major exercise. Collard forwarded the letters to his superior, Vice-Admiral Sir John Kelly; he immediately passed them on to the Commander-in-Chief, Admiral Sir Roger Keyes. On realising that the relationship between the two and their Flag Officer had irretrievably broken down, Keyes ordered the exercise postponed by fifteen hours and ordered a court of inquiry to be convened. As a consequence, Collard was ordered to strike his flag in ''Royal Oak'' and Dewar and Daniel were ordered back to Britain. The Admiralty was informed of the bare facts on 12 March and Keyes proceeded to sea with the Mediterranean Fleet for the exercise as planned. The press picked up on the story worldwide, describing the affair—with some hyperbole—as a "mutiny". Public attention reached such proportions as to raise the concerns of the

As Flag Captain to Admiral Collard, Dewar was technically Collard's chief staff officer as well as captain of ''Royal Oak''. A good working relationship between Dewar and the second-in-command of the battle squadron was necessary. Notwithstanding, Collard on occasion acted imperiously and tactlessly on his flagship, causing friction with Dewar and his executive officer, Commander Henry Martin Daniel, DSO. At a dance on the quarterdeck on 12 January 1928, Collard openly lambasted Royal Marine Bandmaster Percy Barnacle and allegedly said "I won't have a bugger like that in my ship" in the presence of ship's officers and guests. Dewar and Daniel accused Collard of "vindictive fault-finding" and openly humiliating and insulting them before their crew, referring to an incident involving Collard's disembarkation from the ship on 5 March where the admiral had openly said that he was "fed up with the ship"; Collard countercharged the two with failing to follow orders and treating him "worse than a midshipman".

Dewar and Daniel, feeling that morale was sinking due to these public displays, wrote letters of complaint which were given to Collard on 10 March, on the eve of a major exercise. Collard forwarded the letters to his superior, Vice-Admiral Sir John Kelly; he immediately passed them on to the Commander-in-Chief, Admiral Sir Roger Keyes. On realising that the relationship between the two and their Flag Officer had irretrievably broken down, Keyes ordered the exercise postponed by fifteen hours and ordered a court of inquiry to be convened. As a consequence, Collard was ordered to strike his flag in ''Royal Oak'' and Dewar and Daniel were ordered back to Britain. The Admiralty was informed of the bare facts on 12 March and Keyes proceeded to sea with the Mediterranean Fleet for the exercise as planned. The press picked up on the story worldwide, describing the affair—with some hyperbole—as a "mutiny". Public attention reached such proportions as to raise the concerns of the

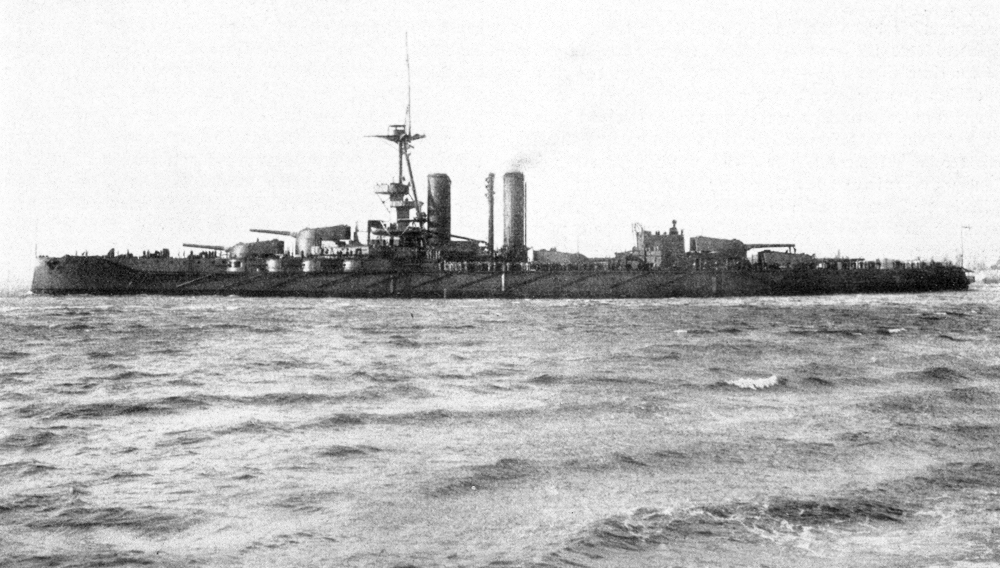

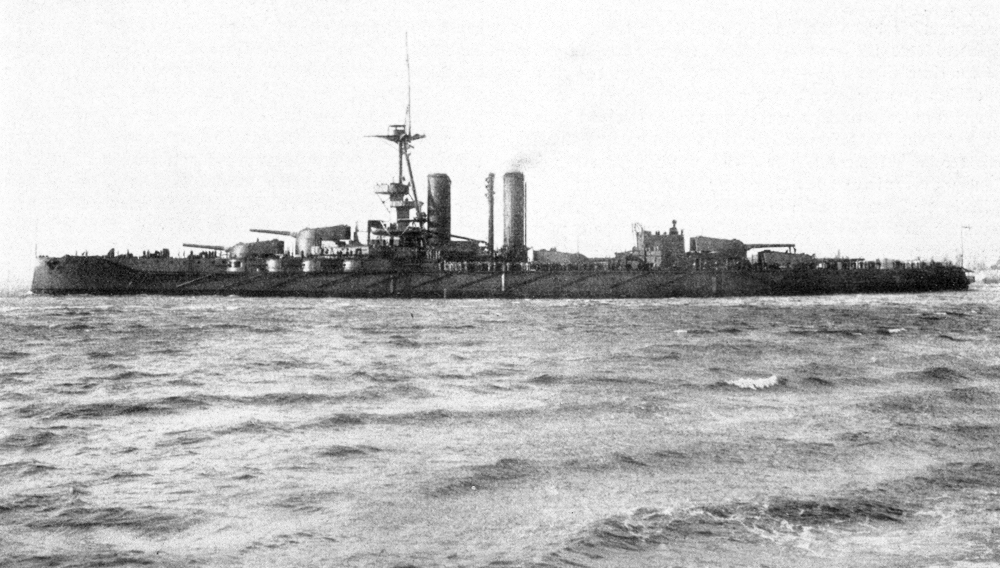

Dewar was once more given duty at sea. However, he was to be relegated to second-rate commands for a man of his seniority. Much to the surprise of many, on 25 September 1928 it was announced that from 5 November Dewar would be given command of the battle cruiser ''Tiger'', the oldest of her type still in service and engaged primarily in training. However, it demonstrated the Admiralty's continued, albeit conditional, faith in him. He commanded ''Tiger'' until he was given command of HMS ''Iron Duke'' the following year. On 29 May 1929, he was made a naval aide-de-camp (ADC) to King George V. However, Dewar's time in the Navy was drawing to a close. On 4 August, he was finally promoted to rear-admiral, and the following day he was retired. Promotion to flag rank also saw the end of his duty as ADC to the King. On the day of his promotion he was also granted the Good Service pension of £150 per annum.

Dewar was once more given duty at sea. However, he was to be relegated to second-rate commands for a man of his seniority. Much to the surprise of many, on 25 September 1928 it was announced that from 5 November Dewar would be given command of the battle cruiser ''Tiger'', the oldest of her type still in service and engaged primarily in training. However, it demonstrated the Admiralty's continued, albeit conditional, faith in him. He commanded ''Tiger'' until he was given command of HMS ''Iron Duke'' the following year. On 29 May 1929, he was made a naval aide-de-camp (ADC) to King George V. However, Dewar's time in the Navy was drawing to a close. On 4 August, he was finally promoted to rear-admiral, and the following day he was retired. Promotion to flag rank also saw the end of his duty as ADC to the King. On the day of his promotion he was also granted the Good Service pension of £150 per annum.

In the 1931 General Election, Dewar stood as a Labour party candidate in

In the 1931 General Election, Dewar stood as a Labour party candidate in

CBE

The Most Excellent Order of the British Empire is a British order of chivalry, rewarding contributions to the arts and sciences, work with charitable and welfare organisations,

and public service outside the civil service. It was established o ...

(21 September 1879 – 8 September 1964) was an officer of the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

. After specialising as a gunnery officer, Dewar became a staff officer and a controversial student of naval tactics before seeing extensive service during the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

. He served in the Dardanelles Campaign and commanded a monitor

Monitor or monitor may refer to:

Places

* Monitor, Alberta

* Monitor, Indiana, town in the United States

* Monitor, Kentucky

* Monitor, Oregon, unincorporated community in the United States

* Monitor, Washington

* Monitor, Logan County, West ...

in home waters before serving at the Admiralty

Admiralty most often refers to:

*Admiralty, Hong Kong

*Admiralty (United Kingdom), military department in command of the Royal Navy from 1707 to 1964

*The rank of admiral

*Admiralty law

Admiralty can also refer to:

Buildings

* Admiralty, Traf ...

for more than four years of staff duty. After the war ended he became embroiled in the controversy surrounding the consequences of the Battle of Jutland

The Battle of Jutland (german: Skagerrakschlacht, the Battle of the Skagerrak) was a naval battle fought between Britain's Royal Navy Grand Fleet, under Admiral John Jellicoe, 1st Earl Jellicoe, Sir John Jellicoe, and the Imperial German Navy ...

. Despite this, he held a variety of commands during the 1920s.

In 1928 he was at the heart of the "Royal Oak Mutiny", when as captain of the battleship

A battleship is a large armored warship with a main battery consisting of large caliber guns. It dominated naval warfare in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

The term ''battleship'' came into use in the late 1880s to describe a type of ...

''Royal Oak'' he forwarded his executive officer's letter of complaint about their immediate superior, Rear-Admiral Collard, to a higher authority. This came in the wake of a series of incidents aboard ship. All three men were ordered back to Britain, and Dewar and his executive officer requested Courts-martial

A court-martial or court martial (plural ''courts-martial'' or ''courts martial'', as "martial" is a postpositive adjective) is a military court or a trial conducted in such a court. A court-martial is empowered to determine the guilt of memb ...

so that they might defend themselves. The trials were held in Gibraltar

)

, anthem = " God Save the King"

, song = " Gibraltar Anthem"

, image_map = Gibraltar location in Europe.svg

, map_alt = Location of Gibraltar in Europe

, map_caption = United Kingdom shown in pale green

, mapsize =

, image_map2 = Gib ...

and garnered widespread media coverage.

Dewar, though found partially guilty, survived with a severe reprimand. His executive officer was found guilty and resigned, while Collard was compelled to resign his commission for provoking the situation. Having then commanded successively the two oldest capital ships in the fleet, Dewar retired on promotion to rear-admiral. His memoirs, published as ''The Navy from Within'' in 1939, were a vitriolic indictment of the Navy's practices.

Early life and career

Dewar was born in Queensferry on 21 September 1879, the son of Dr. James and Mrs. Flora Dewar. In July, 1893 he was nominated as a naval cadet, passed the entrance examination and joined the training ship ''Britannia'', where he studied for two years. Two of his brothers joined the navy; Alfred Charles (born 1876) who was promoted toCaptain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police department, election precinct, e ...

on the Retired List and was appointed Head of the Historical Section of the Naval Staff, and Alan Ramsay (born 1887) who achieved Flag Rank

A flag officer is a commissioned officer in a nation's armed forces senior enough to be entitled to fly a flag to mark the position from which the officer exercises command.

The term is used differently in different countries:

*In many countries ...

in 1938. Dewar performed so well in ''Britannia,'' that upon graduation, he was appointed Midshipman straight away, which normally required a year's service at sea and passing an examination. He joined the protected cruiser

Protected cruisers, a type of naval cruiser of the late-19th century, gained their description because an armoured deck offered protection for vital machine-spaces from fragments caused by shells exploding above them. Protected cruisers re ...

''Hawke'' on 20 August 1895. The following year he was appointed to the battleship

A battleship is a large armored warship with a main battery consisting of large caliber guns. It dominated naval warfare in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

The term ''battleship'' came into use in the late 1880s to describe a type of ...

''Magnificent'' on 30 October 1896. Promoted acting sub-lieutenant

Sub-lieutenant is usually a junior officer rank, used in armies, navies and air forces.

In most armies, sub-lieutenant is the lowest officer rank. However, in Brazil, it is the highest non-commissioned rank, and in Spain, it is the second high ...

, Dewar was confirmed in that rank on 15 February 1899 and promoted to lieutenant

A lieutenant ( , ; abbreviated Lt., Lt, LT, Lieut and similar) is a commissioned officer rank in the armed forces of many nations.

The meaning of lieutenant differs in different militaries (see comparative military ranks), but it is often sub ...

on 15 February 1900. Following promotion he was posted to the Devonport destroyer

In naval terminology, a destroyer is a fast, manoeuvrable, long-endurance warship intended to escort

larger vessels in a fleet, convoy or battle group and defend them against powerful short range attackers. They were originally developed in ...

''Osprey'' on 15 March, and on 12 June that year he was appointed to the torpedo-boat destroyer

In naval terminology, a destroyer is a fast, manoeuvrable, long-endurance warship intended to escort

larger vessels in a fleet, convoy or battle group and defend them against powerful short range attackers. They were originally developed in 1 ...

''Fervent''.

Gunnery officer

Following this period at sea, Lieutenant Dewar was selected to specialise in gunnery duties. His time training at HMS ''Excellent'', the gunnery school at Portsmouth, coincided with that of the captaincy ofPercy Scott

Admiral Sir Percy Moreton Scott, 1st Baronet, (10 July 1853 – 18 October 1924) was a British Royal Navy officer and a pioneer in modern naval gunnery. During his career he proved to be an engineer and problem solver of some considerable f ...

, the renowned gunnery expert. His performance on the two-year course was so impressive that on graduation he was given command of a ship. From 21 July 1903, Dewar was Lieutenant and Commander of the Chatham-based destroyer ''Mermaid''.

Dewar became the gunnery officer of the armoured cruiser

The armored cruiser was a type of warship of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. It was designed like other types of cruisers to operate as a long-range, independent warship, capable of defeating any ship apart from a battleship and fast eno ...

''Kent'' on 24 August 1905, where he remained until 1908. Dewar's dedication and standard of training became evident when his ship led the Fleet in battle practice firings and gunlayer's-test. He was reassigned to ''Excellent'' on 19 January 1908 for instruction duties. Soon he was sent to sea again, being made gunnery officer of the battleship ''Prince George'' on 8 February 1908. He rejoined ''Excellent'' on 22 December that year. On 11 June 1909 Dewar was "lent" as gunnery officer to the protected cruiser ''Spartiate'' for the annual fleet manœuvres. Once the manœuvres were finished, Dewar was made assistant to the Inspector of Target Practice, an important gunnery position at the Admiralty on 17 July. In the same year, he was asked to lecture on the Imperial Japanese Navy

The Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN; Kyūjitai: Shinjitai: ' 'Navy of the Greater Japanese Empire', or ''Nippon Kaigun'', 'Japanese Navy') was the navy of the Empire of Japan from 1868 to 1945, when it was dissolved following Japan's surrender ...

, which he had previously had experience of, at the Royal Naval War College at Portsmouth. During his talk, he exhibited an unpalatable forthrightness by saying that the Royal Navy needed more intellectual officers like Togo Heihachiro

Togo (), officially the Togolese Republic (french: République togolaise), is a country in West Africa. It is bordered by Ghana to the west, Benin to the east and Burkina Faso to the north. It extends south to the Gulf of Guinea, where its c ...

, implying that there was a dearth of such officers. The President of the College, Lewis Bayly

Lewis may refer to:

Names

* Lewis (given name), including a list of people with the given name

* Lewis (surname), including a list of people with the surname

Music

* Lewis (musician), Canadian singer

* " Lewis (Mistreated)", a song by Radiohea ...

, abruptly terminated his lecture.

On 1 January 1910, Dewar was once more given sea duty as first lieutenant and gunnery officer (referred to as "1st and G") of ''Dreadnought''. ''Dreadnought'' was still one of the most prestigious postings in the fleet despite the growing number of newer dreadnought

The dreadnought (alternatively spelled dreadnaught) was the predominant type of battleship in the early 20th century. The first of the kind, the Royal Navy's , had such an impact when launched in 1906 that similar battleships built after her ...

battleships and battle cruisers entering service. It was Dewar's misfortune during this service to be taken in by the ''Dreadnought'' hoax on 10 February, in which he escorted a party of practical jokers, that included Virginia Woolf

Adeline Virginia Woolf (; ; 25 January 1882 28 March 1941) was an English writer, considered one of the most important modernist 20th-century authors and a pioneer in the use of stream of consciousness as a narrative device.

Woolf was born i ...

, pretending to be Abyssinian royalty, on an official visit to the battleship. However, Dewar befriended the captain, Herbert Richmond

Admiral Sir Herbert William Richmond, (15 September 1871 – 15 December 1946) was a prominent Royal Navy officer, described as "perhaps the most brilliant naval officer of his generation." He was also a top naval historian, known as the "Briti ...

, who acted both as a friend and a mentor to him in the following years. With Richmond's encouragement, Dewar began a thorough study of naval tactics and strategy which would later continue at the Royal Naval War College.

Promotion to commander

Dewar was reappointed to ''Dreadnought'' on 28 March 1911, was promoted Commander on 22 June and on 14 December he was appointed for duty at the Royal Naval War College, Portsmouth as an instructor. The next year, he was selected to join the newly formed War Staff at the Admiralty, created onFirst Lord of the Admiralty

The First Lord of the Admiralty, or formally the Office of the First Lord of the Admiralty, was the political head of the English and later British Royal Navy. He was the government's senior adviser on all naval affairs, responsible for the di ...

Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 Winston Churchill in the Second World War, dur ...

's orders in 1912. He was consequently reappointed for duty at the War College on 2 April 1912. On 4 March 1913, it was announced that Commander Dewar had been awarded the Gold Medal and Trench-Gascoigne Prize by the Royal United Service Institution

The Royal United Services Institute (RUSI, Rusi), registered as Royal United Service Institute for Defence and Security Studies and formerly the Royal United Services Institute for Defence Studies, is a British defence and security think tank. ...

for his winning essay on the question "What is the war value of oversea commerce? How did it affect our naval policy in the past and how does it in the present day?" The final chapter of the paper was suppressed from publication by the Admiralty; in it Dewar advocated a "distant" blockade in a war with Germany at a time (1912) when the Royal Navy was still contemplating a "close" blockade of the German coastline. In the event, a distant blockade was imposed. Dewar was then and remained unsympathetic to the removal of his concluding chapter;

Dewar's reputation as an intellectual within the Navy was confirmed when in 1912, he became one of the founder members of ''The Naval Review'', an independent journal of Royal Navy officers. That year Richmond had formed a "Naval Society" with a dozen friends, Dewar among them. After Richmond went abroad on active service, Dewar decided that instead of being a society of purely discussion, it ought publish a journal, to which end he "raised subscriptions for the first issue from some forty or fifty officers of all ranks".

In 1914, Dewar was appointed commander (second-in-command) of the battleship ''Prince of Wales'', then flagship of the 5th Battle Squadron in the 2nd Fleet (Home Fleets). On 28 July, Dewar married Gertrude Margaret Stapleton-Bretherton, the sister of Evelyn, Princess Blücher, in a service at St. Bartholomew's Church in Rainhill

Rainhill is a village and civil parish within the Metropolitan Borough of St Helens, in Merseyside, England. The population of the civil parish taken at the 2011 census was 10,853.

Historically part of Lancashire, Rainhill was formerly a townsh ...

on Merseyside

Merseyside ( ) is a metropolitan county, metropolitan and ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in North West England, with a population of List of ceremonial counties of England, 1.38 million. It encompasses both banks of the Merse ...

. The service was conducted by the Archbishop of Liverpool

The Archbishop of Liverpool is the ordinary of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Liverpool and metropolitan of the Province of Liverpool (also known as the Northern Province) in England.

The archdiocese covers an area of of the west of the C ...

and the Bishop of Portsmouth. Dewar's best man was the Honourable Reginald Plunkett

Admiral Sir Reginald Aylmer Ranfurly Plunkett-Ernle-Erle-Drax, KCB, DSO, JP, DL ( Plunkett; 28 August 1880 – 16 October 1967), commonly known as Reginald Plunkett or Reginald Drax, was an Anglo-Irish admiral. The younger son of the 17th Ba ...

, who later became known as Reginald Plunkett-Ernle-Erle-Drax, and would go on to achieve high rank in the Navy. Dewar and Gertrude had one son together, Kenneth Malcolm J. Dewar.

First World War

In August 1914, Britain went to war with Germany, and later that year with theOttoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

(modern-day Turkey

Turkey ( tr, Türkiye ), officially the Republic of Türkiye ( tr, Türkiye Cumhuriyeti, links=no ), is a list of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country located mainly on the Anatolia, Anatolian Peninsula in Western Asia, with ...

). ''Prince of Wales'' remained in the 5th Battle Squadron until 1915, when with a number of other pre-dreadnoughts she was sent to the Eastern Mediterranean to support the Gallipoli landings, the goal of which was to capture the strategically important Dardanelles Straits

The Dardanelles (; tr, Çanakkale Boğazı, lit=Strait of Çanakkale, el, Δαρδανέλλια, translit=Dardanéllia), also known as the Strait of Gallipoli from the Gallipoli peninsula or from Classical Antiquity as the Hellespont (; ...

, take Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth (Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya (Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis (" ...

and knock the Ottoman Empire out of the war. As second-in-command of ''Prince of Wales'', Dewar was present for part of the naval operations in the Dardanelles Campaign against the Turkish positions. Following aborted attempts to lend heavy-gunfire support to the troops at ANZAC Cove, Dewar wrote an unofficial memo to the Rear-Admiral commanding the Eastern Mediterranean Squadron, with suggestions for the employment of indirect fire to attack Turkish targets. Dewar heard nothing of his proposals, and it was not until November 1915 that indirect fire was used with good effect by the bulged cruiser ''Edgar''. Following the campaign, in October Dewar was given command of HM Gunnery School, Devonport. It was an important position as large numbers of Reserve

Reserve or reserves may refer to:

Places

* Reserve, Kansas, a US city

* Reserve, Louisiana, a census-designated place in St. John the Baptist Parish

* Reserve, Montana, a census-designated place in Sheridan County

* Reserve, New Mexico, a US vi ...

and Volunteer Reserve officers either re-qualified or qualified in gunnery duties. After a year Dewar returned to sea in command of the ''Abercrombie'' class monitor ''Roberts'', and joined the Dover Patrol in August, 1916.

In response to the German battle cruiser raids on the British coast, a visible response was called for to quell public anxiety. On 27 May 1916, ''Roberts'' arrived at Gorleston

Gorleston-on-Sea (), known colloquially as Gorleston, is a town in the Borough of Great Yarmouth, in Norfolk, England, to the south of Great Yarmouth. Situated at the mouth of the River Yare it was a port town at the time of the Domesday Book ...

to act as a guard ship for the port of Yarmouth, in effect acting as a coastal defence battery. ''Roberts'' fulfilled such duties at Tyneside

Tyneside is a built-up area across the banks of the River Tyne in northern England. Residents of the area are commonly referred to as Geordies. The whole area is surrounded by the North East Green Belt.

The population of Tyneside as published i ...

and in the Thames Estuary

The Thames Estuary is where the River Thames meets the waters of the North Sea, in the south-east of Great Britain.

Limits

An estuary can be defined according to different criteria (e.g. tidal, geographical, navigational or in terms of salini ...

for the rest of the war. Once again, Dewar was rotated back to shore, and was appointed to the Operations Division of the Naval Staff under first the Jellicoe, and then the Wemyss Boards of Admiralty. Dewar was promoted to the rank of captain on 30 June 1918 in the Half-Yearly lists and then became Assistant Director of Plans in the Plans Division. On 17 October 1919, he was appointed Commander of the Order of the British Empire

The Most Excellent Order of the British Empire is a British order of chivalry, rewarding contributions to the arts and sciences, work with charitable and welfare organisations,

and public service outside the civil service. It was established o ...

(CBE) "for valuable services at the Peace Conference, Paris."

Post-war commands

Jutland controversy

While still at the Admiralty, Dewar became embroiled with the controversies surrounding the aftermath of theBattle of Jutland

The Battle of Jutland (german: Skagerrakschlacht, the Battle of the Skagerrak) was a naval battle fought between Britain's Royal Navy Grand Fleet, under Admiral John Jellicoe, 1st Earl Jellicoe, Sir John Jellicoe, and the Imperial German Navy ...

. The manner in which the battle had been fought had come under criticism, with a line drawn between those who supported Sir John Jellicoe

Admiral of the Fleet John Rushworth Jellicoe, 1st Earl Jellicoe, (5 December 1859 – 20 November 1935) was a Royal Navy officer. He fought in the Anglo-Egyptian War and the Boxer Rebellion and commanded the Grand Fleet at the Battle of Jutla ...

, who had commanded the Grand Fleet

The Grand Fleet was the main battlefleet of the Royal Navy during the First World War. It was established in August 1914 and disbanded in April 1919. Its main base was Scapa Flow in the Orkney Islands.

History

Formed in August 1914 from the ...

at the battle; and those who fell-in behind his then-subordinate and successor, Sir David Beatty. Dewar followed the Beatty school of thought espoused by his former captain, Herbert Richmond, that the battle had been lost by the staid admirals of the battleship squadrons. In November 1920 he and his brother Captain Alfred Dewar (retired) were entrusted with compiling the ''Naval Staff Appreciation'' of the battle, which was completed in January 1922. The two brothers had produced a body of work which favoured Beatty, for whom the Dewars' "capacity for original thinking and literary talents always held an appeal." Even Richmond, who intensely disliked Jellicoe and was a confidant of Beatty, agreed with the Committee on Imperial Defence

The Committee of Imperial Defence was an important ''ad hoc'' part of the Government of the United Kingdom and the British Empire from just after the Second Boer War until the start of the Second World War. It was responsible for research, and som ...

's official naval historian, Sir Julian Corbett who wrote that Dewar's "facts were, I found, very loose."

The Appreciation, which had originally been intended for distribution around the Royal Navy, was deemed so full of "far-reaching and astringent criticism of Jellicoe" and of a new and therefore irrelevant tactical theory that Beatty and his Board of Admiralty were compelled to decide against its publication. Indeed, Admirals Roger Keyes

Admiral of the Fleet Roger John Brownlow Keyes, 1st Baron Keyes, (4 October 1872 – 26 December 1945) was a British naval officer.

As a junior officer he served in a corvette operating from Zanzibar on slavery suppression missions. Ea ...

and Ernle Chatfield

Admiral of the Fleet Alfred Ernle Montacute Chatfield, 1st Baron Chatfield, (27 September 1873 – 15 November 1967) was a Royal Navy officer. During the First World War he was present as Sir David Beatty's Flag-Captain at the Battle of ...

were moved to write to Beatty that if published the Appreciation "would rend the service to its foundations". The final straw had been the very public heckling of Dewar when he lectured from his Appreciation to the twenty students of the Senior Officers' War Course at the Royal Naval College, Greenwich. It was decided to expurgate the existing document, which had been removed from circulation and release it. It was published as ''The Narrative of the Battle of Jutland'' in 1924.

All copies of the original Appreciation were ordered destroyed in 1928 and before the "Narrative" had been published Dewar and his brother had already been barred access to the original. However, he continued to have a major impact on the historiography of the Battle of Jutland by serving throughout the 1920s as Winston Churchill's naval consultant on submarine-warfare. Churchill wrote an anti-Jellicoe tract in his ''World Crisis'', Volume III which in large measure shared Dewar's views on tactics and even some diagrams. Although Dewar would later become a supporter of the Labour Party, after Churchill was passed over for a cabinet position in 1931 Dewar wrote to him on 16 November, "I am very sorry to see that you are not in the new Cabinet. I had hoped you would go to the Admiralty and do very necessary work for the Navy."

Sea duty

After four years of duty at the Admiralty, Dewar returned to sea in 1922. He was fortunate after the "Geddes Axe

The Geddes Axe was the drive for public economy and retrenchment in UK government expenditure recommended in the 1920s by a Committee on National Expenditure chaired by Sir Eric Geddes and with Lord Inchcape, Lord Faringdon, Sir Joseph Maclay an ...

" (the systematic contraction of the Naval Service to a size substantially smaller than its pre-war level) and his controversial tenure at the Admiralty that he was still considered worthy of sea duty, ''the'' qualification for promotion to flag rank

A flag officer is a commissioned officer in a nation's armed forces senior enough to be entitled to fly a flag to mark the position from which the officer exercises command.

The term is used differently in different countries:

*In many countries ...

. He was appointed on 9 May to command the ''C'' class cruiser ''Calcutta'', flagship on the North America and West Indies Station. In 1923, Dewar was given command of ''Calcutta's'' sister-ship on the same station, HMS ''Cape Town''. While on the station, he had occasion to act as Flag Captain

In the Royal Navy, a flag captain was the captain of an admiral's flagship. During the 18th and 19th centuries, this ship might also have a "captain of the fleet", who would be ranked between the admiral and the "flag captain" as the ship's "First ...

to the Commander-in-Chief on the station, pay calls on cities as diverse as Halifax, Nova Scotia

Halifax is the capital and largest municipality of the Canadian province of Nova Scotia, and the largest municipality in Atlantic Canada. As of the 2021 Census, the municipal population was 439,819, with 348,634 people in its urban area. The ...

, Quebec City

Quebec City ( or ; french: Ville de Québec), officially Québec (), is the capital city of the Provinces and territories of Canada, Canadian province of Quebec. As of July 2021, the city had a population of 549,459, and the Communauté métrop ...

and Boston

Boston (), officially the City of Boston, is the state capital and most populous city of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as well as the cultural and financial center of the New England region of the United States. It is the 24th- mo ...

while cruising the Eastern Seaboard of North America. During the U.S. blockade of the Mexican port of Tampico

Tampico is a city and port in the southeastern part of the state of Tamaulipas, Mexico. It is located on the north bank of the Pánuco River, about inland from the Gulf of Mexico, and directly north of the state of Veracruz. Tampico is the fifth ...

in 1924, Dewar and ''Cape Town'' cancelled their planned cruise of the Caribbean

The Caribbean (, ) ( es, El Caribe; french: la Caraïbe; ht, Karayib; nl, De Caraïben) is a region of the Americas that consists of the Caribbean Sea, its islands (some surrounded by the Caribbean Sea and some bordering both the Caribbean Se ...

to adequately represent the British government at Vera Cruz, proceeding there on 4 January.

On 15 May 1924, Dewar was relieved in command of ''Cape Town'' by Captain G.H. Knowles, DSO. On 2 May 1925, he returned to the Admiralty as Deputy Director of Naval Intelligence. After two years in the position, he was relieved in June 1927 and given from 15 October command of the battleship ''Royal Oak'', flagship of the Rear-Admiral in the 1st Battle Squadron, Mediterranean Fleet

The British Mediterranean Fleet, also known as the Mediterranean Station, was a formation of the Royal Navy. The Fleet was one of the most prestigious commands in the navy for the majority of its history, defending the vital sea link between t ...

. The Rear-Admiral, 1st Battle Squadron was Bernard St. George Collard

Bernard ('' Bernhard'') is a French and West Germanic masculine given name. It is also a surname.

The name is attested from at least the 9th century. West Germanic ''Bernhard'' is composed from the two elements ''bern'' "bear" and ''hard'' "brav ...

.

"The Royal Oak Mutiny"

As Flag Captain to Admiral Collard, Dewar was technically Collard's chief staff officer as well as captain of ''Royal Oak''. A good working relationship between Dewar and the second-in-command of the battle squadron was necessary. Notwithstanding, Collard on occasion acted imperiously and tactlessly on his flagship, causing friction with Dewar and his executive officer, Commander Henry Martin Daniel, DSO. At a dance on the quarterdeck on 12 January 1928, Collard openly lambasted Royal Marine Bandmaster Percy Barnacle and allegedly said "I won't have a bugger like that in my ship" in the presence of ship's officers and guests. Dewar and Daniel accused Collard of "vindictive fault-finding" and openly humiliating and insulting them before their crew, referring to an incident involving Collard's disembarkation from the ship on 5 March where the admiral had openly said that he was "fed up with the ship"; Collard countercharged the two with failing to follow orders and treating him "worse than a midshipman".

Dewar and Daniel, feeling that morale was sinking due to these public displays, wrote letters of complaint which were given to Collard on 10 March, on the eve of a major exercise. Collard forwarded the letters to his superior, Vice-Admiral Sir John Kelly; he immediately passed them on to the Commander-in-Chief, Admiral Sir Roger Keyes. On realising that the relationship between the two and their Flag Officer had irretrievably broken down, Keyes ordered the exercise postponed by fifteen hours and ordered a court of inquiry to be convened. As a consequence, Collard was ordered to strike his flag in ''Royal Oak'' and Dewar and Daniel were ordered back to Britain. The Admiralty was informed of the bare facts on 12 March and Keyes proceeded to sea with the Mediterranean Fleet for the exercise as planned. The press picked up on the story worldwide, describing the affair—with some hyperbole—as a "mutiny". Public attention reached such proportions as to raise the concerns of the

As Flag Captain to Admiral Collard, Dewar was technically Collard's chief staff officer as well as captain of ''Royal Oak''. A good working relationship between Dewar and the second-in-command of the battle squadron was necessary. Notwithstanding, Collard on occasion acted imperiously and tactlessly on his flagship, causing friction with Dewar and his executive officer, Commander Henry Martin Daniel, DSO. At a dance on the quarterdeck on 12 January 1928, Collard openly lambasted Royal Marine Bandmaster Percy Barnacle and allegedly said "I won't have a bugger like that in my ship" in the presence of ship's officers and guests. Dewar and Daniel accused Collard of "vindictive fault-finding" and openly humiliating and insulting them before their crew, referring to an incident involving Collard's disembarkation from the ship on 5 March where the admiral had openly said that he was "fed up with the ship"; Collard countercharged the two with failing to follow orders and treating him "worse than a midshipman".

Dewar and Daniel, feeling that morale was sinking due to these public displays, wrote letters of complaint which were given to Collard on 10 March, on the eve of a major exercise. Collard forwarded the letters to his superior, Vice-Admiral Sir John Kelly; he immediately passed them on to the Commander-in-Chief, Admiral Sir Roger Keyes. On realising that the relationship between the two and their Flag Officer had irretrievably broken down, Keyes ordered the exercise postponed by fifteen hours and ordered a court of inquiry to be convened. As a consequence, Collard was ordered to strike his flag in ''Royal Oak'' and Dewar and Daniel were ordered back to Britain. The Admiralty was informed of the bare facts on 12 March and Keyes proceeded to sea with the Mediterranean Fleet for the exercise as planned. The press picked up on the story worldwide, describing the affair—with some hyperbole—as a "mutiny". Public attention reached such proportions as to raise the concerns of the King

King is the title given to a male monarch in a variety of contexts. The female equivalent is queen, which title is also given to the consort of a king.

*In the context of prehistory, antiquity and contemporary indigenous peoples, the tit ...

, who summoned William Bridgeman, the First Lord of the Admiralty, for an explanation.

Having arrived back in England, Dewar and Daniel gave their version of events at the Admiralty, and put in writing requests for reinstatement in their positions in ''Royal Oak'', or trial by court-martial

A court-martial or court martial (plural ''courts-martial'' or ''courts martial'', as "martial" is a postpositive adjective) is a military court or a trial conducted in such a court. A court-martial is empowered to determine the guilt of memb ...

. Having received Keyes' full dispatch on 16 March, the Board of Admiralty resolved that Dewar and Daniel should undergo trial by court-martial as soon as possible at Gibraltar

)

, anthem = " God Save the King"

, song = " Gibraltar Anthem"

, image_map = Gibraltar location in Europe.svg

, map_alt = Location of Gibraltar in Europe

, map_caption = United Kingdom shown in pale green

, mapsize =

, image_map2 = Gib ...

, where ''Royal Oak'' was due to be berthed. Consequently, Dewar and Commander Daniel departed Southampton in the P&O liner ''Malwa'' with their counsel, Mr. Day Kimball, and their wives, on 24 March and reached Gibraltar in the evening of 27 March. The two officers were immediately attached to the Gibraltar base ship, HMS ''Cormorant'' in accordance with naval custom. It was arranged that Daniel would face court-martial first, on 30 March, and Dewar's would follow at its conclusion.

The courts-martial were held publicly in hangar "A" of the aircraft carrier

An aircraft carrier is a warship that serves as a seagoing airbase, equipped with a full-length flight deck and facilities for carrying, arming, deploying, and recovering aircraft. Typically, it is the capital ship of a fleet, as it allows a ...

''Eagle''. Because ten captains from the fleet sat as members of the court, the departure of the Mediterranean Fleet was delayed until the end of the proceedings. Out of four charges which Daniel faced, two related to writing an allegedly subversive letter (the complaint) and the other two to publicly reading it out to officers of ''Royal Oak''. Dewar consequently faced the charge of having forwarded said subversive letter. The court found Daniel "guilty" on all four charges in the afternoon of 3 April and dismissed him from his ship and ordered him to be severely reprimanded.

Dewar's own court-martial began on 4 April. The court trying him was composed of five rear-admirals and eight captains. Dewar pleaded "not guilty to two charges of accepting and forwarding a letter subversive of discipline and contrary to King's Regulations and Admiralty Instructions". Dewar had the opportunity of cross-examining Rear-Admiral Collard over the incident of the dance and the disembarkation. Collard admitted to saying certain things, but refused to say that he had used improper words and not in earshot of anyone other than the captain.

In his defence, Dewar attacked one of the charges against him, namely that of contravening Article 11 of King's Regulations; he declared the charge invalid because his actions did not "bring him into contempt", and from witness testimony he portrayed himself as having acted in the best interests of his ships, his actions against Rear-Admiral Collard having been made out of a sense of duty and loyalty and not malice. Discounting one charge, he said, meant that the first had to fail as well.

The court reached its verdict on 5 April. The first charge was found proven, the second unproven, and Dewar was therefore acquitted of acting against regulations. However, despite his spotless record, when the court sentenced him to be dismissed from HMS ''Cormorant'', and severely reprimanded—a potentially career-destroying result. However, there was some popular support for his continued service in the Navy. Questions were asked in the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. ...

as to whether Dewar or Daniel would be found new positions. The First Lord, Bridgeman, stated that they would be found positions in the Navy as soon as vacancies arose. Dewar's career was reprieved for the time being. Daniel, however, resigned from the service, and following an unsuccessful attempt at a career in journalism, disappeared into obscurity in South Africa.

Post-''Royal Oak''

Dewar was once more given duty at sea. However, he was to be relegated to second-rate commands for a man of his seniority. Much to the surprise of many, on 25 September 1928 it was announced that from 5 November Dewar would be given command of the battle cruiser ''Tiger'', the oldest of her type still in service and engaged primarily in training. However, it demonstrated the Admiralty's continued, albeit conditional, faith in him. He commanded ''Tiger'' until he was given command of HMS ''Iron Duke'' the following year. On 29 May 1929, he was made a naval aide-de-camp (ADC) to King George V. However, Dewar's time in the Navy was drawing to a close. On 4 August, he was finally promoted to rear-admiral, and the following day he was retired. Promotion to flag rank also saw the end of his duty as ADC to the King. On the day of his promotion he was also granted the Good Service pension of £150 per annum.

Dewar was once more given duty at sea. However, he was to be relegated to second-rate commands for a man of his seniority. Much to the surprise of many, on 25 September 1928 it was announced that from 5 November Dewar would be given command of the battle cruiser ''Tiger'', the oldest of her type still in service and engaged primarily in training. However, it demonstrated the Admiralty's continued, albeit conditional, faith in him. He commanded ''Tiger'' until he was given command of HMS ''Iron Duke'' the following year. On 29 May 1929, he was made a naval aide-de-camp (ADC) to King George V. However, Dewar's time in the Navy was drawing to a close. On 4 August, he was finally promoted to rear-admiral, and the following day he was retired. Promotion to flag rank also saw the end of his duty as ADC to the King. On the day of his promotion he was also granted the Good Service pension of £150 per annum.

Standing for Parliament

In the 1931 General Election, Dewar stood as a Labour party candidate in

In the 1931 General Election, Dewar stood as a Labour party candidate in Portsmouth North

Portsmouth North is a constituency represented in the House of Commons of the UK Parliament since 2010 by Penny Mordaunt, the current Leader of the House of Commons and Lord President of the Council. She is a Conservative MP.

Boundaries

191 ...

, where he lost against the incumbent by 14,149 votes. Once more Dewar was unable to escape controversy, having put up posters around the naval city which raised indignation among many sailors and officers.

The posters, which Dewar himself called "propaganda sheets", were titled "Admiral Dewar's Election News", and carried the statement "The British Navy at Jutland in 1916 beat the ex-Kaiser; and at Invergordon

Invergordon (; gd, Inbhir Ghòrdain or ) is a town and port in Easter Ross, in Ross and Cromarty, Highland (council area), Highland, Scotland. It lies in the parish of Rosskeen.

History

The town built up around the harbour which was establish ...

in 1931 it beat Mr. Montagu Norman

Montagu Collet Norman, 1st Baron Norman DSO PC (6 September 1871 – 4 February 1950) was an English banker, best known for his role as the Governor of the Bank of England from 1920 to 1944.

Norman led the bank during the toughest period in m ...

", and featured prominently a depiction of the former Kaiser of Germany in civilian clothing in front of a sea battle, with the Governor of the Bank of England

The governor of the Bank of England is the most senior position in the Bank of England. It is nominally a civil service post, but the appointment tends to be from within the bank, with the incumbent grooming their successor. The governor of the Ba ...

, Montagu Norman, looking on. A notice beneath the picture read:

Dewar was accused of comparing Jutland to the Invergordon Mutiny

The Invergordon Mutiny was an industrial action by around 1,000 sailors in the British Atlantic Fleet that took place on 15–16 September 1931. For two days, ships of the Royal Navy at Invergordon were in open mutiny, in one of the few mili ...

, which rankled many servicemen who had fought at Jutland, but had taken no part in the 1931 mutiny in Northern Scotland. He claimed in his defence–a statement issued to the press on 29 October 1931–that he had had nothing to do with the design or production of the poster, which had been published by the National Cooperative Publishing Society. Later Dewar wrote, "I deeply regret that this picture should ever have been associated with my name." At this point, he had already lost at the polls by a substantial margin, the election having taken place on 27 October.

Later life

As part of Navy Week in 1933 on 5 August, Dewar was invited to open a naval paintings exhibition at the Ilford Galleries in London. He took the opportunity to praise theWashington Naval Conference

The Washington Naval Conference was a disarmament conference called by the United States and held in Washington, DC from November 12, 1921 to February 6, 1922. It was conducted outside the auspices of the League of Nations. It was attended by nine ...

and the London Naval Conference 1930

The London Naval Treaty, officially the Treaty for the Limitation and Reduction of Naval Armament, was an agreement between the United Kingdom, Japan, France, Italy, and the United States that was signed on 22 April 1930. Seeking to address is ...

, and to criticise the size of the Treaty battleship

A treaty battleship was a battleship built in the 1920s or 1930s under the terms of one of a number of international treaties governing warship construction. Many of these ships played an active role in the Second World War, but few survived long ...

. On the retired list of the Royal Navy, he was promoted to the rank of vice-admiral (retd.) on 31 July 1934.

In early 1939, Dewar's memoirs

A memoir (; , ) is any nonfiction narrative writing based in the author's personal memories. The assertions made in the work are thus understood to be factual. While memoir has historically been defined as a subcategory of biography or autobiog ...

were published. In ''The Navy from Within'', he recounted his life story, while at the same time criticising severely the manner in which the Royal Navy trained its officers, blaming defects in said training for the naval failure at Gallipoli. However, his account was criticised as being far too harsh and at points hypocritical, for after condemning the naval system of training he then made many mentions of naval officers whom he himself considered to be excellent. In a letter to ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British daily national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its current name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its sister paper ''The Sunday Times'' (fou ...

'', Dewar complained that their reviewer was taking far too much issue with the author, which as the reviewer pointed out, "a review of an autobiography

An autobiography, sometimes informally called an autobio, is a self-written account of one's own life.

It is a form of biography.

Definition

The word "autobiography" was first used deprecatingly by William Taylor in 1797 in the English peri ...

must necessarily deal largely with the author himself". Responding to a review of ''The Navy from Within'' in ''The Naval Review'' which questioned the prominence of "The Royal Oak Affair" in the book, Dewar responded by stating;

Dewar, despite the attached stigma of the mutiny and criticism of his memoirs, was still held in high regard by many, and as war

War is an intense armed conflict between states, governments, societies, or paramilitary groups such as mercenaries, insurgents, and militias. It is generally characterized by extreme violence, destruction, and mortality, using regular o ...

approached he wrote a number of letters to ''The Times'' criticising the cost of the Air Raid Precautions

Air Raid Precautions (ARP) refers to a number of organisations and guidelines in the United Kingdom dedicated to the protection of civilians from the danger of air raids. Government consideration for air raid precautions increased in the 1920s an ...

network, which attracted much support in the "Letters" pages in that newspaper.

During the Second World War, he returned to the Admiralty, working under his brother Alfred in the Historical Section of the Training and Staff Duties Division. After the war ended, Dewar would win one final victory when he sued the author and publisher of a book on Admiral Keyes for libel in 1953. In the book written by Brigadier-General Aspinall Oglander was a letter from Keyes to the King's private secretary, Lord Stamfordham

Lieutenant-Colonel Arthur John Bigge, 1st Baron Stamfordham, (18 June 1849 – 31 March 1931) was a British Army officer and courtier. He was Private Secretary to Queen Victoria during the last few years of her reign, and to George V during mos ...

, in which Keyes accused Dewar of having made contact with the press in his defence. Dewar denied this and the High Court of Justice

The High Court of Justice in London, known properly as His Majesty's High Court of Justice in England, together with the Court of Appeal of England and Wales, Court of Appeal and the Crown Court, are the Courts of England and Wales, Senior Cou ...

agreed with him, finding in his favour. The solicitors acting on behalf of Aspinall-Oglander and the publishers, Hogarth Press Ltd., agreed to apologise in court and paid Dewar damages and expenses.

In 1957, he returned to his earlier theme on the failings of officer training, in a three-part exposition on the Dardanelles Campaign for ''The Naval Review'', the journal he had helped found over forty years previously. In the concluding article, published in October 1957, Dewar wrote that the failure of the Navy to adequately support the Army at Gallipoli "is to be found in the system of training officers which consciously or unconsciously suppressed independent thought and suggestions from subordinates." Despite his later close association with Churchill, he criticised the former First Lord's unrealistic expectations and also Lord Fisher's inability to rein him in for want of a naval staff; and Admiral of the Fleet (at the time Commodore

Commodore may refer to:

Ranks

* Commodore (rank), a naval rank

** Commodore (Royal Navy), in the United Kingdom

** Commodore (United States)

** Commodore (Canada)

** Commodore (Finland)

** Commodore (Germany) or ''Kommodore''

* Air commodore ...

) Roger Keyes for actively trying to gain support for forcing the straits again instead of acting as chief of staff and only advising the Naval Commander at the Dardanelles.

Dewar was given the last rites

The last rites, also known as the Commendation of the Dying, are the last prayers and ministrations given to an individual of Christian faith, when possible, shortly before death. They may be administered to those awaiting execution, mortall ...

on 8 September 1964 and died at his home in Worthing

Worthing () is a seaside town in West Sussex, England, at the foot of the South Downs, west of Brighton, and east of Chichester. With a population of 111,400 and an area of , the borough is the second largest component of the Brighton and Hov ...

, Sussex

Sussex (), from the Old English (), is a historic county in South East England that was formerly an independent medieval Anglo-Saxon kingdom. It is bounded to the west by Hampshire, north by Surrey, northeast by Kent, south by the English ...

. He was buried at St Bartholomew's Church, Rainhill, Merseyside on 12 September.

Notes

a. The Inspector of Target Practice had been set up so that the Admiralty could have a gunnery officer other than the Director of Naval Ordnance capable to troubleshoot gunnery standards throughout the Royal Navy, and be of sufficient rank and stature to make their views known. His assistant(s) would be instrumental in observing tests and visiting ships. b. Richmond went on to retire from the navy and became a widely respected naval historian, before assuming the Mastership ofDowning College, Cambridge

Downing College is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge and currently has around 650 students. Founded in 1800, it was the only college to be added to Cambridge University between 1596 and 1869, and is often described as the olde ...

.

c. The Rear-Admiral in a battle squadron would in action command half the ships in a tactical formation called a division, and therefore required a small staff. In event of the Vice-Admiral being incapacitated, the Rear-Admiral would be expected to take active command of the squadron. Indeed, as senior officer in the squadron he would automatically be in command.

d. Keyes gave Collard the option of raising his flag in the battleship ''Resolution'', but Collard refused. He was consequently relieved of his command by the Admiralty and ordered home on the 16th.

e. To be "dismissed his ship", in this case the base ship HMS ''Cormorant'', meant being sent home in disgrace.

f. Calculated from the returns published in ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British daily national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its current name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its sister paper ''The Sunday Times'' (fou ...

'' for the 1929 United Kingdom general election

The 1929 United Kingdom general election was held on Thursday, 30 May 1929 and resulted in a hung parliament. It stands as the fourth of six instances under the secret ballot, and the first of three under universal suffrage, in which a party ha ...

and the 1931 United Kingdom general election

Events

January

* January 2 – South Dakota native Ernest Lawrence invents the cyclotron, used to accelerate particles to study nuclear physics.

* January 4 – German pilot Elly Beinhorn begins her flight to Africa.

* January 22 – Sir I ...

. The Liberal Party

The Liberal Party is any of many political parties around the world. The meaning of ''liberal'' varies around the world, ranging from liberal conservatism on the right to social liberalism on the left.

__TOC__ Active liberal parties

This is a li ...

declined to stand a candidate in 1931, which helps explain the massive increases in the Conservative and Labour votes.

g. *

Citations

References

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Dewar, Kenneth Royal Navy vice admirals Commanders of the Order of the British Empire 1879 births 1964 deaths Royal Navy officers of World War I Royal Navy officers who were court-martialled Graduates of Britannia Royal Naval College Labour Party (UK) parliamentary candidates People from South Queensferry Military personnel from Edinburgh