Kelpie Wearing An Elizabethan Collar on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

A kelpie, or water kelpie (

A kelpie, or water kelpie (

Kelpies have the ability to

Kelpies have the ability to

Alt URL

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * {{Fairies Scottish folklore Shapeshifting Fairies Horses in mythology Water spirits Scottish mythology Scottish legendary creatures

A kelpie, or water kelpie (

A kelpie, or water kelpie (Scottish Gaelic

Scottish Gaelic ( gd, Gàidhlig ), also known as Scots Gaelic and Gaelic, is a Goidelic language (in the Celtic branch of the Indo-European language family) native to the Gaels of Scotland. As a Goidelic language, Scottish Gaelic, as well as ...

: ''Each-Uisge''), is a shape-shifting spirit inhabiting lochs in Scottish folklore

Scottish folklore (Scottish Gaelic: ''Beul-aithris na h-Alba'') encompasses the folklore of the Scottish people from their earliest records until today. Folklorists, both academic and amateur, have published a variety of works focused specifically ...

. It is usually described as a black horse-like creature, able to adopt human form. Some accounts state that the kelpie retains its hooves when appearing as a human, leading to its association with the Christian idea of Satan

Satan,, ; grc, ὁ σατανᾶς or , ; ar, شيطانالخَنَّاس , also known as Devil in Christianity, the Devil, and sometimes also called Lucifer in Christianity, is an non-physical entity, entity in the Abrahamic religions ...

as alluded to by Robert Burns

Robert Burns (25 January 175921 July 1796), also known familiarly as Rabbie Burns, was a Scottish poet and lyricist. He is widely regarded as the national poet of Scotland and is celebrated worldwide. He is the best known of the poets who hav ...

in his 1786 poem " Address to the Devil".

Almost every sizeable body of water in Scotland has an associated kelpie story, but the most extensively reported is that of Loch Ness

Loch Ness (; gd, Loch Nis ) is a large freshwater loch in the Scottish Highlands extending for approximately southwest of Inverness. It takes its name from the River Ness, which flows from the northern end. Loch Ness is best known for clai ...

. The kelpie has counterparts across the world, such as the Germanic nixie, the wihwin

Wihwin is the name given to a malevolent water spirit of Central America, particularly associated with the Miskito tribe. Similar mythological creatures around the world include the kelpie in Scotland, the Scandinavian bäckahäst and the Austral ...

of South America and the Australian bunyip

The bunyip is a creature from the aboriginal mythology of southeastern Australia, said to lurk in swamps, billabongs, creeks, riverbeds, and waterholes.

Name

The origin of the word ''bunyip'' has been traced to the Wemba-Wemba or Wergaia ...

. The origins of narratives about the creature are unclear but the practical purpose of keeping children away from dangerous stretches of water and warning young women to be wary of handsome strangers has been noted in secondary literature.

Kelpies have been portrayed in their various forms in art and literature, including two steel sculptures in Falkirk

Falkirk ( gd, An Eaglais Bhreac, sco, Fawkirk) is a large town in the Central Lowlands of Scotland, historically within the county of Stirlingshire. It lies in the Forth Valley, northwest of Edinburgh and northeast of Glasgow.

Falkirk had a ...

, ''The Kelpies

''The'' () is a grammatical article in English, denoting persons or things already mentioned, under discussion, implied or otherwise presumed familiar to listeners, readers, or speakers. It is the definite article in English. ''The'' is the m ...

'', completed in October 2013.

Etymology

The etymology of the Scots word ''kelpie'' is uncertain, but it may be derived from theGaelic

Gaelic is an adjective that means "pertaining to the Gaels". As a noun it refers to the group of languages spoken by the Gaels, or to any one of the languages individually. Gaelic languages are spoken in Ireland, Scotland, the Isle of Man, and Ca ...

''calpa'' or ''cailpeach'', meaning "heifer" or "colt". The first recorded use of the term to describe a mythological creature, then spelled ''kaelpie'', appears in the manuscript of an ode

An ode (from grc, ᾠδή, ōdḗ) is a type of lyric poetry. Odes are elaborately structured poems praising or glorifying an event or individual, describing nature intellectually as well as emotionally. A classic ode is structured in three majo ...

by William Collins, composed some time before 1759 and reproduced in the Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh

Transaction or transactional may refer to:

Commerce

*Financial transaction, an agreement, communication, or movement carried out between a buyer and a seller to exchange an asset for payment

*Debits and credits in a Double-entry bookkeeping syst ...

of 1788. The place names

Toponymy, toponymics, or toponomastics is the study of ''toponyms'' (proper names of places, also known as place names and geographic names), including their origins, meanings, usage and types. Toponym is the general term for a proper name of ...

Kelpie hoall and Kelpie hooll are reported in '' A Dictionary of the Older Scottish Tongue'' as appearing in the 1674 burgh records for Kirkcudbright

Kirkcudbright ( ; sco, Kirkcoubrie; gd, Cille Chùithbeirt) is a town, parish and a Royal Burgh from 1455 in Kirkcudbrightshire, of which it is traditionally the county town, within Dumfries and Galloway, Scotland.

The town lies southwest of C ...

.

Folk beliefs

Description and common attributes

The kelpie is the most common water spirit in Scottish folklore, and the name is attributed to several different forms in narratives recorded throughout the country. The late 19th century saw the onset of an interest in transcribing folklore, and recorders were inconsistent in spelling and frequentlyanglicised

Anglicisation is the process by which a place or person becomes influenced by English culture or British culture, or a process of cultural and/or linguistic change in which something non-English becomes English. It can also refer to the influen ...

words, which could result in differing names for the same spirit.

Commentators have disagreed over the kelpie's aquatic habitat. Folklorists who define kelpies as spirits living beside rivers, as distinguished from the Celtic lochside-dwelling water horse (''each-uisge

The each-uisge (, literally "water horse") is a water spirit in Scottish folklore, known as the each-uisce (anglicized as ''aughisky'' or ''ech-ushkya'') in Ireland and cabyll-ushtey on the Isle of Man. It usually takes the form of a horse, and ...

''), include 19th-century minister of Tiree

Tiree (; gd, Tiriodh, ) is the most westerly island in the Inner Hebrides of Scotland. The low-lying island, southwest of Coll, has an area of and a population of around 650.

The land is highly fertile, and crofting, alongside tourism, and ...

John Gregorson Campbell

John Gregorson Campbell (1836 – 22 November 1891) was a Scottish folklorist and Free Church minister at the Tiree and Coll parishes in Argyll, Scotland. An avid collector of traditional stories, he became Secretary to the Ossianic Societ ...

and 20th-century writers Lewis Spence

James Lewis Thomas Chalmers Spence (25 November 1874 – 3 March 1955) was a Scottish journalist, poet, author, folklorist and occult scholar. Spence was a Fellow of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, and vice- ...

and Katharine Briggs.Briggs, Katharine, ''An Encyclopedia of Fairies'', quoted in This distinction is not universally applied however; Sir Walter Scott

Sir Walter Scott, 1st Baronet (15 August 1771 – 21 September 1832), was a Scottish novelist, poet, playwright and historian. Many of his works remain classics of European and Scottish literature, notably the novels ''Ivanhoe'', ''Rob Roy (n ...

for instance claims that the kelpie's range may extend to lochs. Mackillop's dictionary reconciles the discrepancy, stating that the kelpie was "initially thought to inhabit ... streams, and later any body of water." But the distinction should stand, argues one annotator, who suggests that people are led astray when an ''each uisge'' in a "common practice of translating" are referred to as kelpies in English accounts, and thus mistakenly attribute loch-dwelling habits to the latter.

Others associate the term ''kelpie'' with a wide variety of legendary creatures. Counterparts in some regions of Scotland include the shoopiltee and nuggle

A nuggle, njuggle, or , is a mythical water horse of primarily Shetland folklore where it is also referred to as a shoepultie or shoopiltee on some parts of the islands. A nocturnal creature that is always of a male gender, there are occasional fl ...

of Shetland

Shetland, also called the Shetland Islands and formerly Zetland, is a subarctic archipelago in Scotland lying between Orkney, the Faroe Islands and Norway. It is the northernmost region of the United Kingdom.

The islands lie about to the no ...

and the tangie

A tangie (or ''tongie'') is a shape-shifting sea spirit in the folklore of the Orkney and Shetland Islands in the British Isles. A sea horse or merman, it takes on the appearance of either a horse or an aged man. Usually described as being cover ...

of Orkney

Orkney (; sco, Orkney; on, Orkneyjar; nrn, Orknøjar), also known as the Orkney Islands, is an archipelago in the Northern Isles of Scotland, situated off the north coast of the island of Great Britain. Orkney is 10 miles (16 km) north ...

; in other parts of the British Islands

The British Islands is a term within the law of the United Kingdom which refers collectively to the following four polities:

* the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland (formerly the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland); ...

they include the Welsh ceffyl dŵr

is a water horse in Welsh folklore, a counterpart of the Scottish kelpie.

In her 1973 book ''Folk-lore and Folk-tales of Wales'', Marie Trevelyan says that the was believed to shapeshift and even fly, although this varies depending on region. F ...

and the Manx cabbyl-ushtey. Parallels to the general Germanic neck

The neck is the part of the body on many vertebrates that connects the head with the torso. The neck supports the weight of the head and protects the nerves that carry sensory and motor information from the brain down to the rest of the body. In ...

and the Scandinavian bäckahäst have been observed; Nick Middleton

Nick Middleton (born 1960) is a British physical geographer and supernumerary fellow of St Anne's College, Oxford. He specialises in desertification.

Middleton was born in London, England. As a geographer, he has travelled to more than 70 countr ...

observes that "the kelpie of Scottish folklore is a direct parallel of the icbäckahästen f Scandinavian folklore. The wihwin

Wihwin is the name given to a malevolent water spirit of Central America, particularly associated with the Miskito tribe. Similar mythological creatures around the world include the kelpie in Scotland, the Scandinavian bäckahäst and the Austral ...

of Central America and the Australian bunyip

The bunyip is a creature from the aboriginal mythology of southeastern Australia, said to lurk in swamps, billabongs, creeks, riverbeds, and waterholes.

Name

The origin of the word ''bunyip'' has been traced to the Wemba-Wemba or Wergaia ...

are seen as similar creatures in other parts of the world.

The kelpie is usually described as a powerful and beautiful black horse inhabiting the deep pools of rivers and streams of Scotland, preying on any humans it encounters, One of the water-kelpie's common identifying characteristics is that its hooves are reversed as compared to those of a normal horse, a trait also shared by the '' nykur'' of Iceland. An Aberdeenshire

Aberdeenshire ( sco, Aiberdeenshire; gd, Siorrachd Obar Dheathain) is one of the 32 Subdivisions of Scotland#council areas of Scotland, council areas of Scotland.

It takes its name from the County of Aberdeen which has substantially differe ...

variation portrays the kelpie as a horse with a mane of serpents, whereas the resident equine spirit of the River Spey

The River Spey (Scottish Gaelic: Uisge Spè) is a river in the northeast of Scotland. At it is the eighth longest river in the United Kingdom, as well as the second longest and fastest-flowing river in Scotland. It is important for salmon fishi ...

was white and could entice victims onto its back by singing.

The creature's nature was described by Walter Gregor

Walter Gregor (1825–1897) was a Scottish folklorist, linguist and minister of religion. His anthropological research work won him an international reputation.

Life

The son of James Gregor, a tenant farmer of Forgieside, near Keith, Banffshire ...

, a folklorist and one of the first members of the Folklore Society

The Folklore Society (FLS) is a national association in the United Kingdom for the study of folklore.

It was founded in London in 1878 to study traditional vernacular culture, including traditional music, song, dance and drama, narrative, arts an ...

, as "useful", "hurtful", or seeking "human companionship"; in some cases, kelpies take their victims into the water, devour them, and throw the entrails to the water's edge. In its equine form the kelpie is able to extend the length of its back to carry many riders together into the depths; a common theme in the tales is of several children clambering onto the creature's back while one remains on the shore. Usually a little boy, he then pets the horse but his hand sticks to its neck. In some variations the lad cuts off his fingers or hand to free himself; he survives but the other children are carried off and drowned, with only some of their entrails being found later. Such a creature said to inhabit Glen Keltney in Perthshire

Perthshire (locally: ; gd, Siorrachd Pheairt), officially the County of Perth, is a historic county and registration county in central Scotland. Geographically it extends from Strathmore in the east, to the Pass of Drumochter in the north, ...

is considered to be a kelpie by 20th-century folklorist Katharine Mary Briggs

Katharine Mary Briggs (8 November 1898 – 15 October 1980) was a British folklorist and writer, who wrote ''The Anatomy of Puck'', the four-volume ''A Dictionary of British Folk-Tales in the English Language'', and various other books on fairie ...

, but a similar tale also set in Perthshire has an ''each uisge'' as the culprit and omits the embellishment of the young boy. The lad does cut his finger off when the event takes place in Thurso

Thurso (pronounced ; sco, Thursa, gd, Inbhir Theòrsa ) is a town and former burgh on the north coast of the Highland council area of Scotland. Situated in the historical County of Caithness, it is the northernmost town on the island of Great ...

, where a water kelpie is identified as the culprit. The same tale set at Sunart

Sunart ( , Scottish Gaelic: ''Suaineart'') is a rural district and community in the south west of Lochaber in Highland, Scotland, on the shores of Loch Sunart, and part of the civil parish of Ardnamurchan. The main village is Strontian, at the head ...

in the Highlands

Highland is a broad term for areas of higher elevation, such as a mountain range or mountainous plateau.

Highland, Highlands, or The Highlands, may also refer to:

Places Albania

* Dukagjin Highlands

Armenia

* Armenian Highlands

Australia

*Sou ...

gives a specific figure of nine children lost, of whom only the innards of one are recovered. The surviving boy is again saved by cutting off his finger, and the additional information is given that he had a Bible in his pocket. Gregorson Campbell considers the creature responsible to have been a water horse rather than a kelpie, and the tale "obviously a pious fraud to keep children from wandering on Sundays".

Kelpie myths usually describe a solitary creature, but a fairy story recorded by John F. Campbell in ''Popular Tales of the West Highlands

''Popular Tales of the West Highlands'' is a four-volume collection of fairy tales, collected and published by John Francis Campbell, and often translated from Gaelic. Alexander Carmichael was one of the main contributors. The collection in four ...

'' (1860) has a different perspective. Entitled ''Of the Drocht na Vougha or Fuoah'', which is given the translation ''of the bridge of the fairies or kelpies'', it features a group of voughas. The spirits had set about constructing a bridge over the Dornoch Firth

The Dornoch Firth ( gd, Caolas Dhòrnaich, ) is a firth on the east coast of Highland, in northern Scotland. It forms part of the boundary between Ross and Cromarty, to the south, and Sutherland, to the north. The firth is designated as a nationa ...

after becoming tired of travelling across the water in cockleshells. It was a magnificent piece of work resplendent with gold piers and posts, but sank into the water to become a treacherous area of quicksand after a grateful onlooker tried to bless the kelpies for their work. The same story is recorded by Folklore Society member and folklore collector Charlotte Dempster simply as ''The Kelpie's Bridge'' (1888) with no mention of Voughas or Fuoah. Quoting the same narrative Jennifer Westwood

Jennifer Westwood (5 January 1940 – 12 May 2008) was a British author, broadcaster and folklorist. She was a Doctor of Philosophy with special interests in English Language, Anglo-Saxon and Old Norse. Her first book, ''Mediaeval Tales'', was pu ...

, author and folklorist, uses the descriptor ''water kelpies'', adding that in her opinion "Kelpies, here and in a few other instances, is used in a loose sense to mean something like 'imps.

Progeny resulting from a mating between a kelpie and a normal horse were impossible to drown, and could be recognised by their shorter than normal ears, a characteristic shared by the mythical water bull

The water bull, also known as ''tarbh-uisge'' in Scottish Gaelic, is a mythological Scottish creature similar to the Manx ''tarroo ushtey''. Generally regarded as a nocturnal resident of moorland lochs, it is usually more amiable than its equine ...

or ''tarbh uisge'' in Scottish Gaelic, similar to the Manx ''tarroo ushtey''.

Shapeshifting

Kelpies have the ability to

Kelpies have the ability to transform

Transform may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* Transform (scratch), a type of scratch used by turntablists

* ''Transform'' (Alva Noto album), 2001

* ''Transform'' (Howard Jones album) or the title song, 2019

* ''Transform'' (Powerman 5000 album ...

themselves into non-equine forms, and can take on the outward appearance of human figures, in which guise they may betray themselves by the presence of water weeds in their hair. Gregor described a kelpie adopting the guise of a wizened old man continually muttering to himself while sitting on a bridge stitching a pair of trousers. Believing it to be a kelpie, a passing local struck it on the head, causing it to revert to its equine form and scamper back to its lair in a nearby pond. Other accounts describe the kelpie when appearing in human form as a "rough, shaggy man who leaps behind a solitary rider, gripping and crushing him", or as tearing apart and devouring humans.

A folk tale from Barra

Barra (; gd, Barraigh or ; sco, Barra) is an island in the Outer Hebrides, Scotland, and the second southernmost inhabited island there, after the adjacent island of Vatersay to which it is connected by a short causeway. The island is na ...

tells of a lonely kelpie that transforms itself into a handsome young man to woo a pretty young girl it was determined to take for its wife. But the girl recognises the young man as a kelpie and removes his silver

Silver is a chemical element with the Symbol (chemistry), symbol Ag (from the Latin ', derived from the Proto-Indo-European wikt:Reconstruction:Proto-Indo-European/h₂erǵ-, ''h₂erǵ'': "shiny" or "white") and atomic number 47. A soft, whi ...

necklace

A necklace is an article of jewellery that is worn around the neck. Necklaces may have been one of the earliest types of adornment worn by humans. They often serve Ceremony, ceremonial, Religion, religious, magic (illusion), magical, or Funerary ...

(his bridle) while he sleeps. The kelpie immediately reverts to its equine form, and the girl takes it home to her father's farm, where it is put to work for a year. At the end of that time the girl rides the kelpie to consult a wise man, who tells her to return the silver necklace. The wise man then asks the kelpie, once again transformed into the handsome young man the girl had first met, whether if given the choice it would choose to be a kelpie or a mortal. The kelpie in turn asks the girl whether, if he were a man, she would agree to be his wife. She confirms that she would, after which the kelpie chooses to become a mortal man, and the pair are married.

Traditionally, kelpies in their human form are male. One of the few stories describing the creature in female form is set at Conon House in Ross and Cromarty

Ross and Cromarty ( gd, Ros agus Cromba), sometimes referred to as Ross-shire and Cromartyshire, is a variously defined area in the Highlands and Islands of Scotland. There is a registration county and a lieutenancy area in current use, the latt ...

. It tells of a "tall woman dressed in green", with a "withered, meagre countenance, ever distorted by a malignant scowl", who overpowered and drowned a man and a boy after she jumped out of a stream.

The arrival of Christianity in Scotland in the 6th century resulted in some folk stories and beliefs being recorded by scribes, usually Christian monks, instead of being perpetuated by word of mouth

Word of mouth, or ''viva voce'', is the passing of information from person to person using oral communication, which could be as simple as telling someone the time of day. Storytelling is a common form of word-of-mouth communication where one pe ...

. Some accounts state that the kelpie retains its hooves even in human form, leading to its association with the Christian notion of Satan

Satan,, ; grc, ὁ σατανᾶς or , ; ar, شيطانالخَنَّاس , also known as Devil in Christianity, the Devil, and sometimes also called Lucifer in Christianity, is an non-physical entity, entity in the Abrahamic religions ...

, just as with the Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

god Pan. Robert Burns

Robert Burns (25 January 175921 July 1796), also known familiarly as Rabbie Burns, was a Scottish poet and lyricist. He is widely regarded as the national poet of Scotland and is celebrated worldwide. He is the best known of the poets who hav ...

refers to such a Satanic association in his " Address to the Devil" (1786):

Capture and killing

When a kelpie appeared in its equine persona without anytack

TACK is a group of archaea acronym for Thaumarchaeota (now Nitrososphaerota), Aigarchaeota, Crenarchaeota (now Thermoproteota), and Korarchaeota, the first groups discovered. They are found in different environments ranging from acidophilic the ...

, it could be captured using a halter stamped with the sign of a cross

A cross is a geometrical figure consisting of two intersecting lines or bars, usually perpendicular to each other. The lines usually run vertically and horizontally. A cross of oblique lines, in the shape of the Latin letter X, is termed a sa ...

, and its strength could then be harnessed in tasks such as the transportation of heavy mill stones. One folk tale describes how the Laird of Morphie captured a kelpie and used it to carry stones to build his castle. Once the work was complete, the laird released the kelpie, which was evidently unhappy about its treatment. The curse it issued before leaving – "Sair back and sair banes/ Drivin' the Laird o' Morphies's stanes,/ The Laird o' Morphie'll never thrive/ As lang's the kelpy is alive" – (Sore back and sore bones/ Driving the Lord of Morphie's stones,/ The Lord of Morphie will never thrive/ As long as the kelpie is alive) was popularly believed to have resulted in the extinction of the laird's family. Some kelpies were said to be equipped with a bridle and sometimes a saddle, and appeared invitingly ready to ride, but if mounted they would run off and drown their riders. If the kelpie was already wearing a bridle, exorcism

Exorcism () is the religious or spiritual practice of evicting demons, jinns, or other malevolent spiritual entities from a person, or an area, that is believed to be possessed. Depending on the spiritual beliefs of the exorcist, this may be ...

might be achieved by removing it. A bridle taken from a kelpie was endowed with magical properties, and if brandished towards someone, was able to transform that person into a horse or pony.

Just as with cinematic werewolves

In folklore, a werewolf (), or occasionally lycanthrope (; ; uk, Вовкулака, Vovkulaka), is an individual that can shapeshift into a wolf (or, especially in modern film, a therianthropic hybrid wolf-like creature), either purposely or ...

, a kelpie can be killed by being shot with a silver bullet, after which it is seen to consist of nothing more than "turf and a soft mass like jelly-fish" according to an account published by Spence. When a blacksmith's family were being frightened by the repeated appearances of a water kelpie at their summer cottage, the blacksmith managed to render it into a "heap of starch, or something like it" by penetrating the spirit's flanks with two sharp iron spears that had been heated in a fire.

Loch Ness

Almost every sizeable Scottish body of water has a kelpie story associated with it, but the most widely reported is the kelpie ofLoch Ness

Loch Ness (; gd, Loch Nis ) is a large freshwater loch in the Scottish Highlands extending for approximately southwest of Inverness. It takes its name from the River Ness, which flows from the northern end. Loch Ness is best known for clai ...

. Several stories of mythical spirits and monsters are attached to the loch's vicinity, dating back to 6th-century reports of Saint Columba

Columba or Colmcille; gd, Calum Cille; gv, Colum Keeilley; non, Kolban or at least partly reinterpreted as (7 December 521 – 9 June 597 AD) was an Irish abbot and missionary evangelist credited with spreading Christianity in what is toda ...

defeating a monster on the banks of the River Ness

The River Ness (Scottish Gaelic: ''Abhainn Nis'') is a river in Highland, Scotland, UK. It flows from Loch Dochfour, at the northern end of Loch Ness, north-east to the mouth of the Beauly Firth at Inverness, a distance of about , with a fall ...

. The early 19th-century kelpie that haunted the woods and shores of Loch Ness was tacked up with its own saddle and bridle. A fable attached to the notoriously nasty creature has the Highlander James MacGrigor taking it by surprise and cutting off its bridle, the source of its power and life, without which it would die within twenty-four hours. As the kelpie had the power of speech, it attempted unsuccessfully to bargain with MacGrigor for the return of its bridle. After following MacGrigor to his home, the kelpie asserted that MacGrigor would be unable to enter his house while in possession of the bridle, because of the presence of a cross above the entrance door. But MacGrigor outwitted the creature by tossing the bridle through a window, so the kelpie accepted its fate and left, cursing and swearing. The myth is perpetuated with further tales of the bridle as it is passed down through the family. Referred to as "Willox's Ball and Bridle", it had magical powers of healing; a spell was made by placing the items in water while chanting "In the name of the Father, the Son and of the Holy Ghost"; the water could then be used as a cure.

A popular and more recent explanation for the Loch Ness monster among believers is that it belongs to a line of long-surviving plesiosaurs

The Plesiosauria (; Greek: πλησίος, ''plesios'', meaning "near to" and ''sauros'', meaning "lizard") or plesiosaurs are an order or clade of extinct Mesozoic marine reptiles, belonging to the Sauropterygia.

Plesiosaurs first appeared ...

, but the kelpie myth still survives in children's books such as Mollie Hunter

Maureen Mollie Hunter McIlwraith (30 June 1922 – 31 July 2012) was a Scottish writer known as Mollie Hunter. She wrote fantasy for children, historical stories for young adults, and realistic novels for adults. Many of her works are inspired b ...

's ''The Kelpie's Pearls'' (1966) and Dick King-Smith

Ronald Gordon King-Smith OBE (27 March 1922 – 4 January 2011), was an English writer of children's books, primarily using the pen name Dick King-Smith. He is best known for ''The Sheep-Pig'' (1983). It was adapted as the movie ''Babe'' (1995) ...

's ''The Water Horse'' (1990).

Origins

According to Derek Gath Whitley (1911), the association with horses may have its roots inhorse sacrifice

Horse sacrifice is the ritual killing and offering of a horse, usually as part of a religious or cultural ritual. Horse sacrifices were common throughout Eurasia with the domestication of the horse and continuing up until the spread of Abrahamic ...

s performed in ancient Scandinavia

Scandinavia; Sámi languages: /. ( ) is a subregion#Europe, subregion in Northern Europe, with strong historical, cultural, and linguistic ties between its constituent peoples. In English usage, ''Scandinavia'' most commonly refers to Denmark, ...

. Stories of malevolent water spirits served the practical purpose of keeping children away from perilous areas of water, and of warning adolescent women to be wary of attractive young strangers. The stories were also used to enforce moral standards, as they implied that the creatures took retribution for bad behaviour carried out on Sundays. The intervention of demons and spirits was possibly a way to rationalise the drowning of children and adults who had accidentally fallen into deep, fast flowing or turbulent water.

Historian and symbol

A symbol is a mark, sign, or word that indicates, signifies, or is understood as representing an idea, object, or relationship. Symbols allow people to go beyond what is known or seen by creating linkages between otherwise very different conc ...

ogist Charles Milton Smith has hypothesised that the kelpie myth might originate with the water spout

A waterspout is an intense columnar vortex (usually appearing as a funnel-shaped cloud) that occurs over a body of water. Some are connected to a cumulus congestus cloud, some to a cumuliform cloud and some to a cumulonimbus cloud. In the com ...

s that can form over the surface of Scottish lochs, giving the impression of a living form as they move across the water. Sir Walter Scott alludes to a similar explanation in his epic poem ''The Lady of the Lake

The Lady of the Lake (french: Dame du Lac, Demoiselle du Lac, cy, Arglwyddes y Llyn, kw, Arloedhes an Lynn, br, Itron al Lenn, it, Dama del Lago) is a name or a title used by several either fairy or fairy-like but human enchantresses in the ...

'' (1810), which contains the lines

in which Scott uses "River Demon" to denote a "kelpy". Scott may also have hinted at an alternative rational explanation by naming a treacherous area of quicksand

Quicksand is a colloid

A colloid is a mixture in which one substance consisting of microscopically dispersed insoluble particles is suspended throughout another substance. Some definitions specify that the particles must be dispersed in a ...

"Kelpie's Flow" in his novel ''The Bride of Lammermoor

''The Bride of Lammermoor'' is a historical novel by Sir Walter Scott, published in 1819, one of the Waverley novels. The novel is set in the Lammermuir Hills of south-east Scotland, shortly before the Act of Union of 1707 (in the first editio ...

'' (1818).

Artistic representations

Pictish stone

A Pictish stone is a type of monumental stele, generally carved or incised with symbols or designs. A few have ogham inscriptions. Located in Scotland, mostly north of the Clyde-Forth line and on the Eastern side of the country, these stones are ...

s dating from the 6th to 9th centuries featuring what has been dubbed the Pictish Beast

The Pictish Beast (sometimes Pictish Dragon or Pictish Elephant) is an artistic representation of an animal depicted on Pictish symbol stones.

Design

The Pictish Beast is not easily identifiable with any real animal, but resembles a seahorse, ...

may be the earliest representations of a kelpie or kelpie-like creature.

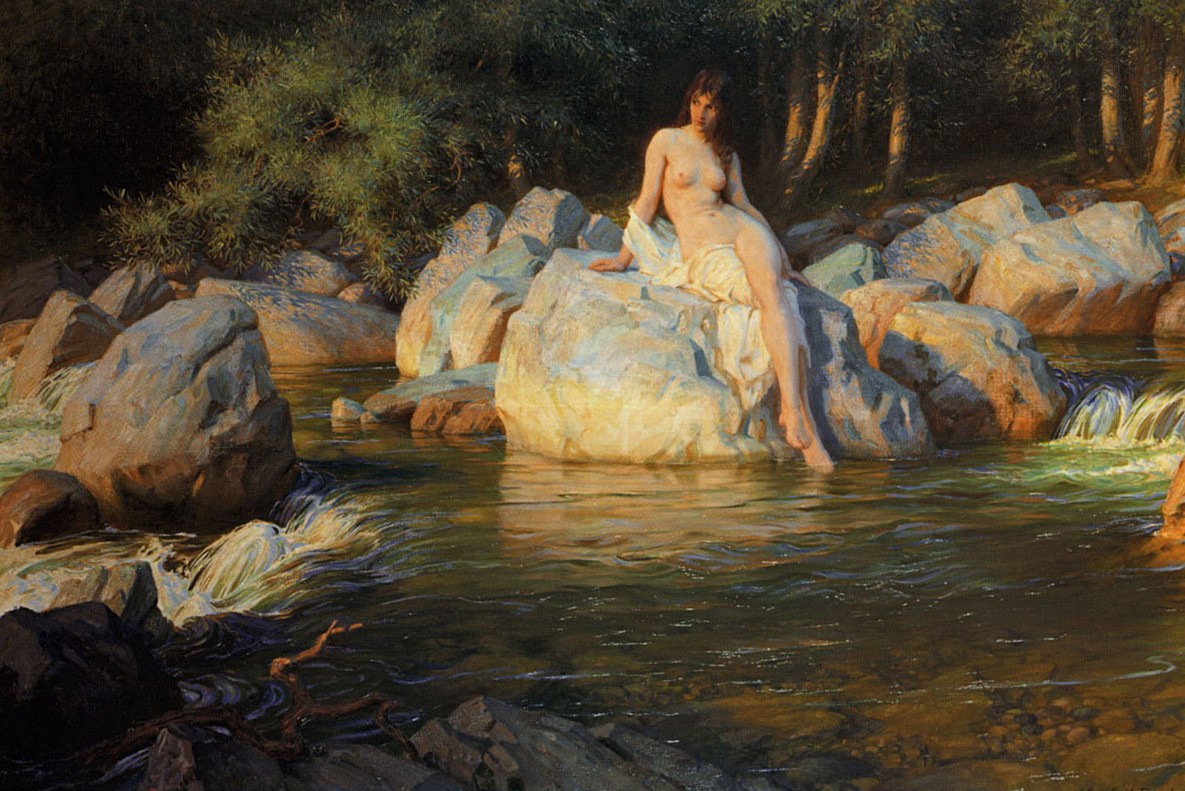

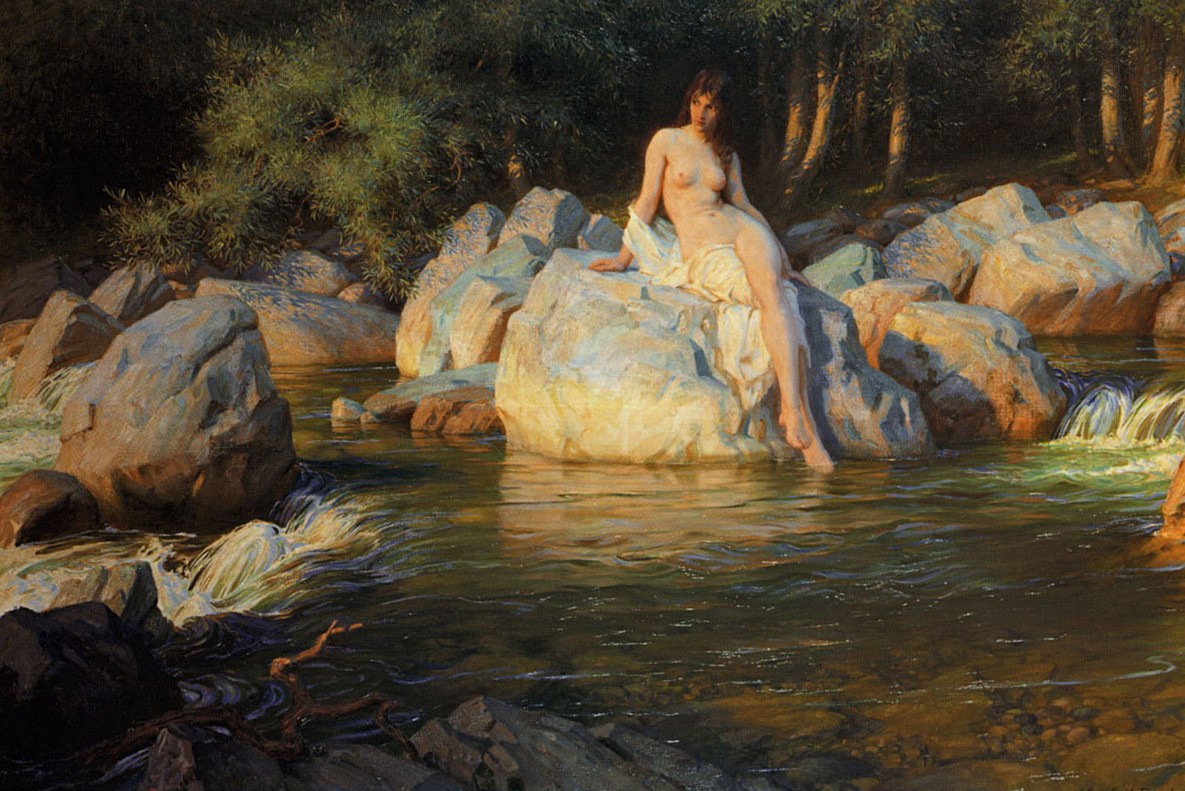

Victorian artist Thomas Millie Dow

Thomas Millie Dow (28 October 1848 – 3 July 1919) was a Scottish artist and member of the Glasgow Boys school. He was a member of The Royal Scottish Society of Painters in Watercolour and the New English Art Club.

Early life and education ...

sketched the kelpie in 1895 as a melancholy dark-haired maiden balanced on a rock, a common depiction for artists of the period. Other depictions show kelpies as poolside maidens, as in Draper

Draper was originally a term for a retailer or wholesaler of cloth that was mainly for clothing. A draper may additionally operate as a cloth merchant or a haberdasher.

History

Drapers were an important trade guild during the medieval period ...

's 1913 oil on canvas. Folklorist Nicola Bown has suggested that painters such as Millie Dow and Draper deliberately ignored earlier accounts of the kelpie and reinvented it by altering its sex and nature.

Two steel sculptures in Falkirk

Falkirk ( gd, An Eaglais Bhreac, sco, Fawkirk) is a large town in the Central Lowlands of Scotland, historically within the county of Stirlingshire. It lies in the Forth Valley, northwest of Edinburgh and northeast of Glasgow.

Falkirk had a ...

on the Forth and Clyde Canal

The Forth and Clyde Canal is a canal opened in 1790, crossing central Scotland; it provided a route for the seagoing vessels of the day between the Firth of Forth and the Firth of Clyde at the narrowest part of the Scottish Lowlands. This allo ...

, named ''The Kelpies

''The'' () is a grammatical article in English, denoting persons or things already mentioned, under discussion, implied or otherwise presumed familiar to listeners, readers, or speakers. It is the definite article in English. ''The'' is the m ...

'', borrow the name of the mythical creature to associate with the strength and endurance of the horse; designed by sculptor Andy Scott, they were built as monuments to Scotland's horse-powered industrial heritage. Construction was completed in October 2013 and the sculptures were opened for public access from April 2014.

See also

*Water horse

A water horse (or "waterhorse" in some folklore) is a mythical creature, such as the , , the and kelpie.

Name origin

The term "water horse" was originally a name given to the kelpie, a creature similar to the hippocamp, which has the head, n ...

* Nuckelavee

The nuckelavee () or nuckalavee is a horse-like demon from Orcadian folklore that combines equine and human elements. British folklorist Katharine Briggs called it "the nastiest" of all the demons of Scotland's Northern Isles. The nuckelavee ...

* Hippocampus (mythology)

The hippocampus or hippocamp, also ''hippokampos'' (plural: hippocampi or hippocamps; grc, ἱππόκαμπος, from , "horse" and , "sea monster"

* Kappa (folklore)

A — also known as , , with a boss called or – is a reptiloid ''kami'' with similarities to ''yōkai'' found in traditional Japanese folklore. '' Kappa'' can become harmful when they are not respected as gods. They are typically depicted ...

* Neck (water spirit)

The Nixie, Nixy, Nix, Näcken, Nicor, Nøkk, or Nøkken (german: Nixe; nl, nikker, ; da, nøkke; Norwegian nb, nøkk; nn, nykk; sv, näck; fo, nykur; fi, näkki; is, nykur; et, näkk; ang, nicor; eng, neck or ) are humanoid, and ...

* Peg Powler Peg Powler is a hag and water spirit in English folklore who inhabits the River Tees. Similar to the Grindylow, Jenny Greenteeth, and Nelly Longarms, she drags children into the water if they get too close to the edge. She is regarded as a bogey ...

* Selkie

In Celtic and Norse mythology, selkies (also spelled ', ', ') or selkie folk ( sco, selkie fowk) meaning 'seal folk' are mythological beings capable of therianthropy, changing from seal to human form by shedding their skin. They are found ...

* Vodyanoi

References

Citations

Bibliography

*Alt URL

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * {{Fairies Scottish folklore Shapeshifting Fairies Horses in mythology Water spirits Scottish mythology Scottish legendary creatures