Keeley Institute on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

took over the declining institute. In 1939 the institute celebrated its 60th anniversary. A ceremony which unveiled a commemorative plaque bearing the likenesses of Keeley, Oughton and Judd attracted 10,000 people. The plaque, designed by Florence Gray, a student of Lorado Taft, is still on the grounds, complete with a time capsule. The Keeley Institute continued to operate until it definitively shut down in 1965.

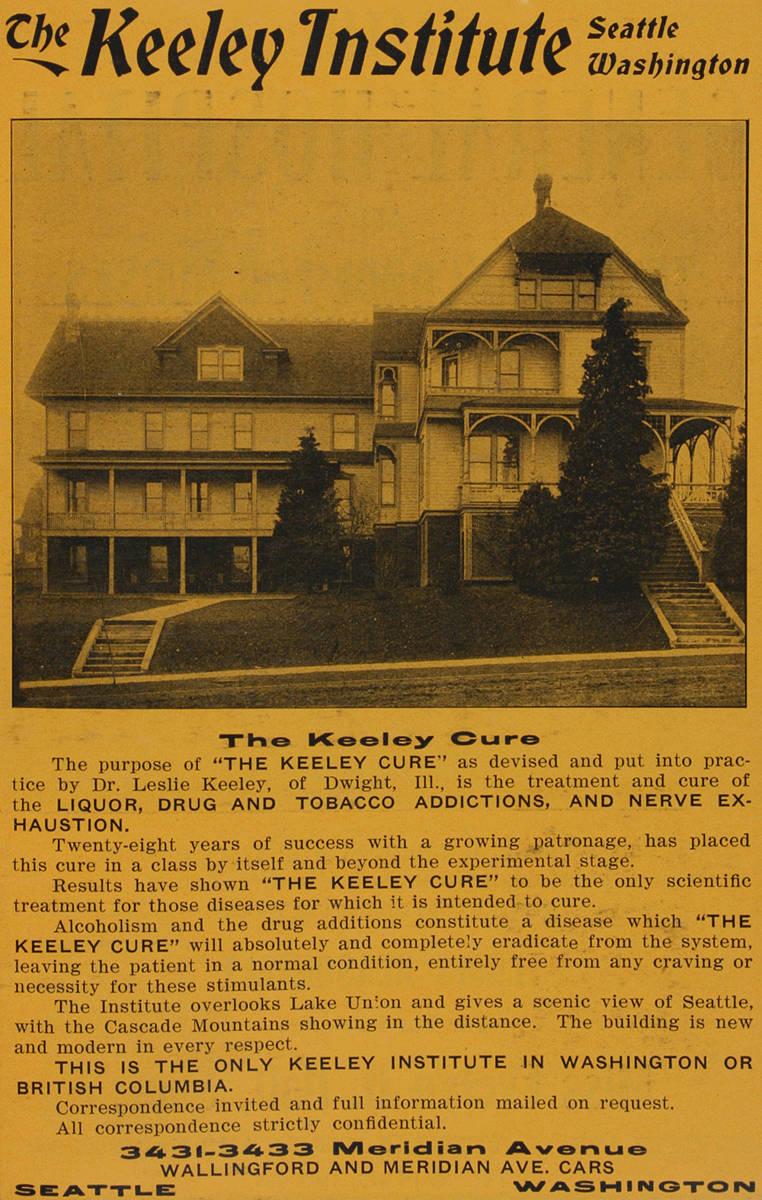

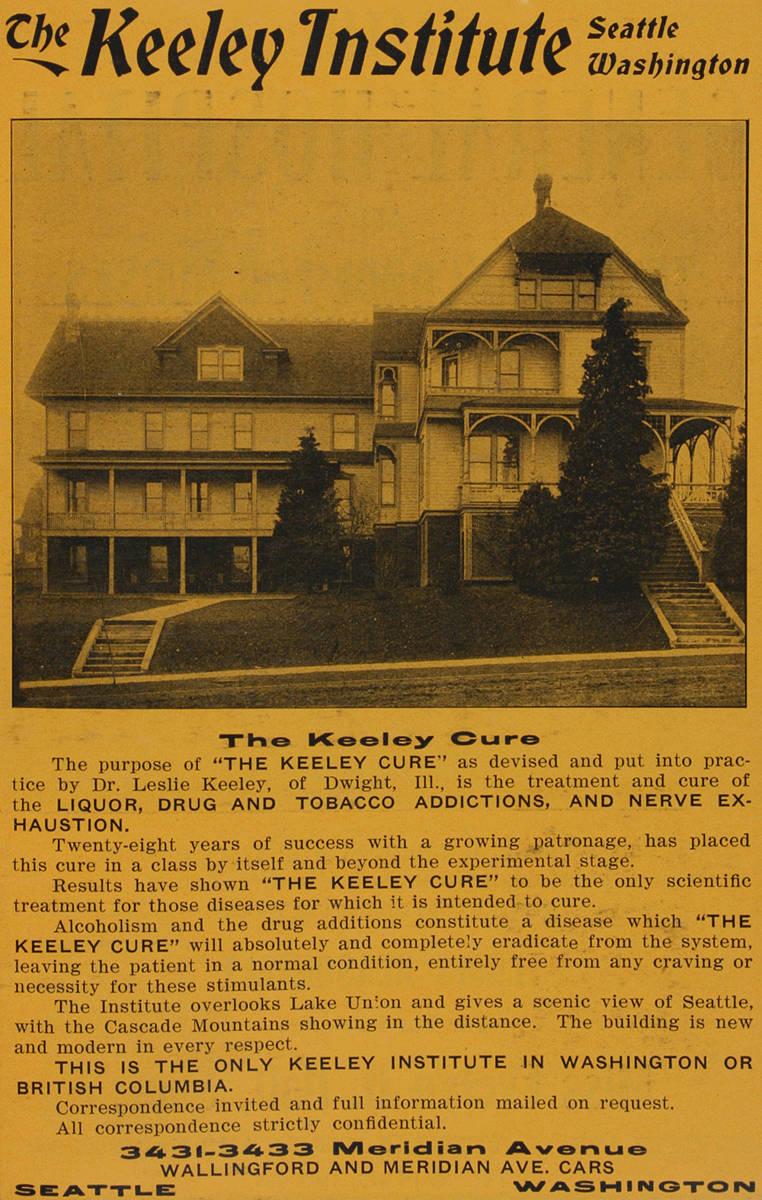

The Keeley Institute, known for its Keeley Cure or Gold Cure, was a commercial medical operation that offered treatment to

Google Books

, Continuum International Publishing Group: 2005, p. 231, (). Retrieved 30 September 2007. The discovery, a new treatment for The Keeley Institute eventually had over 200 branches throughout the United States and Europe, and by 1900 the so-called Keeley Cure, injections of

The Keeley Institute eventually had over 200 branches throughout the United States and Europe, and by 1900 the so-called Keeley Cure, injections of

The Parent Institute; Experiences of the drunkards who go to Dwight to be cured

" ''The New York Times'', 18 October 1891. Retrieved 30 September 2007.Anonymous.

" ''The New York Times'', 14 May 1893. Retrieved 30 September 2007. In the June 10, 1894 edition of the ''New York World'',

" ''Time Magazine'', 25 September 1939. Retrieved 30 September 2007. Oughton and Judd took over the company following Keeley's death, and continued to operate the institute. But without Keeley, its primary spokesman and defender, the organization, which had always drawn some criticism, faded into national oblivion. By the late 1930s most

'' magazine article that the treatment program had cured "17,000 drunken doctors".

When John R. Oughton died in 1925 his James H. Oughton">son

A son is a male offspring; a boy or a man in relation to his parents. The female counterpart is a daughter. From a biological perspective, a son constitutes a first degree relative.

Social issues

In pre-industrial societies and some current c ...alcoholic

Alcoholism is, broadly, any drinking of alcohol that results in significant mental or physical health problems. Because there is disagreement on the definition of the word ''alcoholism'', it is not a recognized diagnostic entity. Predomin ...

s from 1879 to 1965. Though at one time there were more than 200 branches in the United States and Europe, the original institute was founded by Leslie Keeley

Leslie Enraught Keeley (June 10, 1836 – February 21, 1900) was an American physician, originator of the Keeley Cure.

Biography

He was born in Potsdam, New York, on June 10, 1836.

Keeley graduated at the Rush Medical College, Chicago, in 1863, ...

in Dwight, Illinois

Dwight is a village located mainly in Livingston County, Illinois, with a small portion in Grundy County. The population was 4,032 at the 2020 census. Dwight contains an original stretch of U.S. Route 66, and from 1892 until 2016 continuously us ...

, United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

. The Keeley Institute's location in Dwight, Illinois, had a major influence on the development of Dwight as a village, though only a few indications of its significance remain in the village.

After Keeley's death the institute began a slow decline but remained in operation under John R. Oughton, and, later, his son. The Institute offered the internationally known Keeley Cure, a cure which drew sharp criticism from those in the mainstream medical profession. It was wildly popular in the late 1890s. Thousands of people came to Dwight to be cured of alcoholism; thousands more sent for the mail-order oral liquid form which they took in the privacy of their homes.

History

In 1879, Dr.Leslie Keeley

Leslie Enraught Keeley (June 10, 1836 – February 21, 1900) was an American physician, originator of the Keeley Cure.

Biography

He was born in Potsdam, New York, on June 10, 1836.

Keeley graduated at the Rush Medical College, Chicago, in 1863, ...

announced the result of a collaboration with John R. Oughton, an Irish chemist

A chemist (from Greek ''chēm(ía)'' alchemy; replacing ''chymist'' from Medieval Latin ''alchemist'') is a scientist trained in the study of chemistry. Chemists study the composition of matter and its properties. Chemists carefully describe th ...

, which was heralded as a "major discovery" by Keeley.Lion, Jean Pierre. ''Bix: The Definitive Biography of a Jazz Legend'',Google Books

, Continuum International Publishing Group: 2005, p. 231, (). Retrieved 30 September 2007. The discovery, a new treatment for

alcoholism

Alcoholism is, broadly, any drinking of alcohol (drug), alcohol that results in significant Mental health, mental or physical health problems. Because there is disagreement on the definition of the word ''alcoholism'', it is not a recognize ...

, resulted in the founding of the Keeley Institute. The treatment was developed from a partnership with John Oughton, an Irish chemist, and a merchant named Curtis Judd.("Fargo, N.D., History Exhibition") The institute attempted to treat alcoholism as a disease. Patients who were cured using this treatment were honored as "graduates" and asked to promote the cure. (Tracy) Keeley became wealthy through the popularity of the institute and its well-known slogan, "Drunkenness is a disease and I can cure it." His work foreshadowed later work that would attribute a physiological

Physiology (; ) is the scientific study of functions and mechanisms in a living system. As a sub-discipline of biology, physiology focuses on how organisms, organ systems, individual organs, cells, and biomolecules carry out the chemical ...

nature to alcoholism.

The Dwight, Illinois location was the original institute founded by Leslie Keeley that treated alcoholics with the infamous Keeley Cure, which was criticized by the medical profession.(Lender, and Martin) This cure, which later became known as the "gold cure", expanded to over 200 locations in the United States and Europe.(Keeley Cure)

The Keeley Institute eventually had over 200 branches throughout the United States and Europe, and by 1900 the so-called Keeley Cure, injections of

The Keeley Institute eventually had over 200 branches throughout the United States and Europe, and by 1900 the so-called Keeley Cure, injections of bichloride of gold

Gold(III) chloride, traditionally called auric chloride, is a compound of gold and chlorine with the molecular formula . The "III" in the name indicates that the gold has an oxidation state of +3, typical for many gold compounds. Gold(III) c ...

, had been administered to more than 300,000 people. The reputation of the Keeley Cure was largely enhanced by positive coverage from the ''Chicago Tribune

The ''Chicago Tribune'' is a daily newspaper based in Chicago, Illinois, United States, owned by Tribune Publishing. Founded in 1847, and formerly self-styled as the "World's Greatest Newspaper" (a slogan for which WGN radio and television ar ...

''. ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

'' also featured coverage on the Keeley Institute as early as 1891, and in 1893 a Brooklyn

Brooklyn () is a borough of New York City, coextensive with Kings County, in the U.S. state of New York. Kings County is the most populous county in the State of New York, and the second-most densely populated county in the United States, be ...

man's drunken rabble-rousing received coverage which noted he was a Keeley Institute graduate. ''The Times'' said "it is not everyday that a man from the Keeley Institute for the cure of drunkenness comes to New-York and gets into such a predicament."Anonymous.The Parent Institute; Experiences of the drunkards who go to Dwight to be cured

" ''The New York Times'', 18 October 1891. Retrieved 30 September 2007.Anonymous.

" ''The New York Times'', 14 May 1893. Retrieved 30 September 2007. In the June 10, 1894 edition of the ''New York World'',

Nellie Bly

Elizabeth Cochran Seaman (born Elizabeth Jane Cochran; May 5, 1864 – January 27, 1922), better known by her pen name Nellie Bly, was an American journalist, industrialist, inventor, and charity worker who was widely known for her record-breaki ...

's undercover report on the Keeley Institute in White Plains, New York

(Always Faithful)

, image_seal = WhitePlainsSeal.png

, seal_link =

, subdivision_type = List of sovereign states, Country

, subdivision_name =

, subdivision_type1 = U.S. state, State

, su ...

, was published as "Nellie Bly Takes The Keeley Cure." A subheadline described the story as Bly’s account of "A Week’s Experience and Odd Talks with the Queer Little Family of Hopeful Inebriates."

After Keeley died in 1900, the patient numbers lowered; 100,000 additional people took the cure between 1900 and 1939.Keeley Cure" ''Time Magazine'', 25 September 1939. Retrieved 30 September 2007. Oughton and Judd took over the company following Keeley's death, and continued to operate the institute. But without Keeley, its primary spokesman and defender, the organization, which had always drawn some criticism, faded into national oblivion. By the late 1930s most

physician

A physician (American English), medical practitioner (Commonwealth English), medical doctor, or simply doctor, is a health professional who practices medicine, which is concerned with promoting, maintaining or restoring health through th ...

s believed that "drunkards are neurotics 'sic''.html"_;"title="sic.html"_;"title="'sic">'sic''">sic.html"_;"title="'sic">'sic''and_cannot_be_cured_by_injections."'sic''.html"_;"title="sic.html"_;"title="'sic">'sic''">sic.html"_;"title="'sic">'sic''and_cannot_be_cured_by_injections."_

Time_is_the_continued_sequence_of_existence_and_events_that_occurs_in_an_apparently__irreversible_succession_from_the_past,_through_the__present,_into_the__future._It_is_a_component_quantity_of_various__measurements_used_to_sequence_events,_to_...

''_magazine_article_that_the_treatment_program_had_cured_"17,000_drunken_doctors".Treatment

Treatment at the Keeley Institute has been referred to as pioneering and humane. The institute maintained a philosophy of open, homelike care throughout its history. Little is known of what exactly went on in the many branches orfranchise

Franchise may refer to:

Business and law

* Franchising, a business method that involves licensing of trademarks and methods of doing business to franchisees

* Franchise, a privilege to operate a type of business such as a cable television p ...

s of the Keeley Institute around the world but it is thought that many were modeled after the Dwight institute.Tracy, Sarah W. ''Alcoholism in America: From Reconstruction to Prohibition'',Google Books

, Johns Hopkins University Press: 2005, pp. 114–118, (). Retrieved 30 September 2007. New patients who arrived at the Dwight institute were introduced into an open, informal environment where they were first offered as much

alcohol

Alcohol most commonly refers to:

* Alcohol (chemistry), an organic compound in which a hydroxyl group is bound to a carbon atom

* Alcohol (drug), an intoxicant found in alcoholic drinks

Alcohol may also refer to:

Chemicals

* Ethanol, one of sev ...

as they could imbibe. Initially, patients were boarded in nearby hotels, such as the Dwight Livingston Hotel, or the homes of private residents. Later patients stayed in the converted John R. Oughton House.Lehman, John M.John R. Oughton House

" (

PDF

Portable Document Format (PDF), standardized as ISO 32000, is a file format developed by Adobe in 1992 to present documents, including text formatting and images, in a manner independent of application software, hardware, and operating systems. ...

), National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form, 25 April 1980, HAARGIS Database, ''Illinois Historic Preservation Agency'', pp. 1–9. Retrieved 30 September 2007. The institute operated out of homes and hotels using a spa like atmosphere of peace and comfort. All patients received injections of bichloride of gold

Gold(III) chloride, traditionally called auric chloride, is a compound of gold and chlorine with the molecular formula . The "III" in the name indicates that the gold has an oxidation state of +3, typical for many gold compounds. Gold(III) c ...

four times daily. There were other tonics given as well.(Tracy) The treatment lasted four weeks.(Larson pp. 161–163.) The medical profession continued to criticize the method and many tried to identify the mysterious ingredients. Strychnine

Strychnine (, , US chiefly ) is a highly toxic, colorless, bitter, crystalline alkaloid used as a pesticide, particularly for killing small vertebrates such as birds and rodents. Strychnine, when inhaled, swallowed, or absorbed through the eye ...

, alcohol, apomorphine

Apomorphine, sold under the brand name Apokyn among others, is a type of aporphine having activity as a non- selective dopamine agonist which activates both D2-like and, to a much lesser extent, D1-like receptors. It also acts as an antagon ...

, willow bark

Willows, also called sallows and osiers, from the genus ''Salix'', comprise around 400 speciesMabberley, D.J. 1997. The Plant Book, Cambridge University Press #2: Cambridge. of typically deciduous trees and shrubs, found primarily on moist so ...

, ammonia, and atropine

Atropine is a tropane alkaloid and anticholinergic medication used to treat certain types of nerve agent and pesticide poisonings as well as some types of slow heart rate, and to decrease saliva production during surgery. It is typically given i ...

were claimed to have been identified in the injections. The injections were dissolved in red, white and blue liquids and the amounts varied. In addition, patients would receive individually prescribed tonics every two hours throughout the day. Treatments lasted for a period of four weeks.

Patients at Dwight were free to stroll the grounds of the institute as well as the streets of the village. It has been called an early therapeutic community Therapeutic community is a participative, group-based approach to long-term mental illness, personality disorders and drug addiction. The approach was usually residential, with the clients and therapists living together, but increasingly residential ...

.

Maud Faulkner would take her husband Murry to the Keeley Institute located near Memphis

Memphis most commonly refers to:

* Memphis, Egypt, a former capital of ancient Egypt

* Memphis, Tennessee, a major American city

Memphis may also refer to:

Places United States

* Memphis, Alabama

* Memphis, Florida

* Memphis, Indiana

* Memp ...

whenever his drinking became unbearable. While their father received "the cure", William Faulkner

William Cuthbert Faulkner (; September 25, 1897 – July 6, 1962) was an American writer known for his novels and short stories set in the fictional Yoknapatawpha County, based on Lafayette County, Mississippi, where Faulkner spent most of ...

and his brothers would explore the grounds or ride the streetcar to Memphis.

Reaction

The Keeley Institute offered a "scientific" treatment for alcoholism, something that until then was treated by various "miraculous" cures and other types ofquackery

Quackery, often synonymous with health fraud, is the promotion of fraudulent or ignorant medical practices. A quack is a "fraudulent or ignorant pretender to medical skill" or "a person who pretends, professionally or publicly, to have skill, ...

. The Keeley Cure became popular, with hundreds of thousands eventually receiving it. From the beginning, Keeley's decision to keep his formula a secret drew sharp criticism from his peers. The Keeley Institute's popularity with the public never translated to popularity with the medical profession. Medical professionals generally approached commercial cures, such as the Keeley Cure, with skepticism. A promotional brochure for one hospital specifically singled out the Keeley Cure in its language.

Many individuals and groups, especially those within the mainstream medical profession, attempted to analyze the Keeley Cure for its ingredients and reports varied widely as to their identity. Strychnine

Strychnine (, , US chiefly ) is a highly toxic, colorless, bitter, crystalline alkaloid used as a pesticide, particularly for killing small vertebrates such as birds and rodents. Strychnine, when inhaled, swallowed, or absorbed through the eye ...

, alcohol, apomorphine

Apomorphine, sold under the brand name Apokyn among others, is a type of aporphine having activity as a non- selective dopamine agonist which activates both D2-like and, to a much lesser extent, D1-like receptors. It also acts as an antagon ...

, willow bark, ammonia

Ammonia is an inorganic compound of nitrogen and hydrogen with the formula . A stable binary hydride, and the simplest pnictogen hydride, ammonia is a colourless gas with a distinct pungent smell. Biologically, it is a common nitrogenous was ...

, and atropine

Atropine is a tropane alkaloid and anticholinergic medication used to treat certain types of nerve agent and pesticide poisonings as well as some types of slow heart rate, and to decrease saliva production during surgery. It is typically given i ...

were among the many suggested chemicals.

Legacy

The Keeley Institute had a profound influence onDwight Dwight may refer to:

People

* Dwight (given name)

* Dwight D. Eisenhower (1890–1969), 34th president of the United States and former military officer

*New England Dwight family of American educators, military and political leaders, and authors

* ...

's development as a village. As the Institute gained national and international acclaim, Dwight began to develop into a "model" village. Eight hundred passengers per week were arriving in Dwight at the height of the Keeley Institute. Other developments followed the influx of people: modern paved roads replaced older dirt roads, electric light

An electric light, lamp, or light bulb is an electrical component that produces light. It is the most common form of artificial lighting. Lamps usually have a base made of ceramic, metal, glass, or plastic, which secures the lamp in the soc ...

ing was installed in place of older gas lamp

Gas lighting is the production of artificial light from combustion of a gaseous fuel, such as hydrogen, methane, carbon monoxide, propane, butane, acetylene, ethylene, coal gas (town gas) or natural gas. The light is produced either directly ...

s and water and sewage systems were replaced and improved. New homes, businesses, and a railroad depot were all constructed and Dwight became the "most famous village of its size in America."

There are few examples of structures associated with the Keeley Institute still extant in Dwight, and only one is open to the public:

*The Livingston Hotel once provided housing for hundreds of Keeley patients and a Keeley office building, known as the Keeley Building was first used by the institute in 1920, and now houses private commercial offices.

*The John R. Oughton House and its two outbuildings remain; the house operates as a restaurant

A restaurant is a business that prepares and serves food and drinks to customers. Meals are generally served and eaten on the premises, but many restaurants also offer take-out and food delivery services. Restaurants vary greatly in appearan ...

, the carriage house

A carriage house, also called a remise or coach house, is an outbuilding which was originally built to house horse-drawn carriages and the related tack.

In Great Britain the farm building was called a cart shed. These typically were open f ...

is a public library

A public library is a library that is accessible by the general public and is usually funded from public sources, such as taxes. It is operated by librarians and library paraprofessionals, who are also Civil service, civil servants.

There are ...

and the windmill

A windmill is a structure that converts wind power into rotational energy using vanes called windmill sail, sails or blades, specifically to mill (grinding), mill grain (gristmills), but the term is also extended to windpumps, wind turbines, and ...

has been restored and is owned by the Village of Dwight.Historic sites," ''Village of Dwight'', official site. Retrieved 30 September 2007."Welcome to Our Historic Windmill", (

Brochure

A brochure is originally an Information, informative paper document (often also used for advertising) that can be folded into a template, pamphlet, or Folded leaflet, leaflet. A brochure can also be a set of related unfolded papers put into a po ...

), ''Village of Dwight''.

The Keeley Institute solidified its place in American culture throughout its period of prominence as several generations of Americans joked about people, especially the rich and famous, who were "taking the Keeley Cure" or had "gone to Dwight" and Dr. Keeley is remembered as the first to treat alcoholism as a medical disease rather than as a social vice.

Popular culture

In '' The Wet Parade (1932)'', a film version ofUpton Sinclair

Upton Beall Sinclair Jr. (September 20, 1878 – November 25, 1968) was an American writer, muckraker, political activist and the 1934 Democratic Party nominee for governor of California who wrote nearly 100 books and other works in seve ...

's eponymous novel about the devastation wrought by alcoholism

Alcoholism is, broadly, any drinking of alcohol (drug), alcohol that results in significant Mental health, mental or physical health problems. Because there is disagreement on the definition of the word ''alcoholism'', it is not a recognize ...

—and by Prohibition

Prohibition is the act or practice of forbidding something by law; more particularly the term refers to the banning of the manufacture, storage (whether in barrels or in bottles), transportation, sale, possession, and consumption of alcoholic ...

. Roger Chilcote (Lewis Stone

Lewis Shepard Stone (November 15, 1879 – September 12, 1953) was an American film actor. He spent 29 years as a contract player at Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer and was best known for his portrayal of Judge James Hardy in the studio's popular '' Andy ...

) the patriarch of an old Southern family, promises his daughter he will reform after she mentions the Keeley Institute as a last resort, a prospect that he finds horrifyingly shameful.

In the ''Murdoch Mysteries

''Murdoch Mysteries'' is a Canadian television drama series that premiered on Citytv on January 20, 2008, and currently airs on CBC. The series is based on characters from the ''Detective Murdoch'' novels by Maureen Jennings and stars Yannick B ...

'' season 2 episode "Murdoch.com", Inspector Thomas Brackenreid takes injections of the Keeley Gold Cure and experiences aggressive personality changes due to its contents of strychnine and cocaine.

The novel ''Opium and Absinthe: A Novel'' (2020) by Lydia Kang has a character visit the Keeley Institute in White Plains, New York, for an opiate addiction.

In the play ''Cat On A Hot Tin Roof'' (1955) by Tennessee Williams, prominent character Big Mama makes reference to "the Keeley cure" - a treatment for heavy drinkers used back in her day.

References

Further reading

*Tracy, Sarah. {{usurped,"Keeley Cure."

} Keeley Cure. Nebraska State Historical Society, 23 Jan 2006. Web. 1 Jun 2011. *Lender, Max Edward, and James Kirby Martin

"Drinking in America: A History." Drinking in America: A History.

The Free Press, New York, 1982, 21 Aug 2009. Web. 1 Jun 2011.

Really Big Vintage Junk Draw. 01Sep2009. Web. 1 Jun 2011.

Link Label for NC Keeley Institute

Dwight, Illinois Addiction organizations in the United States Drug and alcohol rehabilitation centers Health care companies established in 1879 Buildings and structures in Livingston County, Illinois Mental health organizations in Illinois 1879 establishments in Illinois 1965 disestablishments in Illinois Health care companies disestablished in 1965