Kathleen Ferrier on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

After her Carlisle victories, Ferrier began to receive offers of singing engagements. Her first appearance as a professional vocalist, in autumn 1937, was at a

After her Carlisle victories, Ferrier began to receive offers of singing engagements. Her first appearance as a professional vocalist, in autumn 1937, was at a

On 17 May 1943 Ferrier sang in Handel's ''Messiah'' at

On 17 May 1943 Ferrier sang in Handel's ''Messiah'' at  Ferrier's performances in the Glyndebourne run, which began on 12 July 1946, earned her favourable reviews, although the opera itself was less well received. On the provincial tour which followed the festival it failed to attract the public and incurred heavy financial losses.

By contrast, when the opera reached Amsterdam it was greeted warmly by the Dutch audiences who showed particular enthusiasm for Ferrier's performance. This was Ferrier's first trip abroad, and she wrote an excited letter to her family: "The cleanest houses and windows you ever did see, and flowers in the fields all the way!" Following her success as Lucretia she agreed to return to Glyndebourne in 1947, to sing Orfeo in Gluck's opera '' Orfeo ed Euridice''. She had often sung Orfeo's aria ''Che farò'' ("What is life") as a concert piece, and had recently recorded it with Decca. At Glyndebourne, Ferrier's limited acting abilities caused some difficulties in her relationship with the conductor,

Ferrier's performances in the Glyndebourne run, which began on 12 July 1946, earned her favourable reviews, although the opera itself was less well received. On the provincial tour which followed the festival it failed to attract the public and incurred heavy financial losses.

By contrast, when the opera reached Amsterdam it was greeted warmly by the Dutch audiences who showed particular enthusiasm for Ferrier's performance. This was Ferrier's first trip abroad, and she wrote an excited letter to her family: "The cleanest houses and windows you ever did see, and flowers in the fields all the way!" Following her success as Lucretia she agreed to return to Glyndebourne in 1947, to sing Orfeo in Gluck's opera '' Orfeo ed Euridice''. She had often sung Orfeo's aria ''Che farò'' ("What is life") as a concert piece, and had recently recorded it with Decca. At Glyndebourne, Ferrier's limited acting abilities caused some difficulties in her relationship with the conductor,

On 1 January 1948 Ferrier left for a four-week tour of North America, the first of three transatlantic trips she would make during the next three years. In New York she sang two performances of ''Das Lied von der Erde'', with Bruno Walter and the

On 1 January 1948 Ferrier left for a four-week tour of North America, the first of three transatlantic trips she would make during the next three years. In New York she sang two performances of ''Das Lied von der Erde'', with Bruno Walter and the  Shortly after her return to Britain early in June 1949, Ferrier left for Amsterdam where, on 14 July, she sang in the world premiere of Britten's ''

Shortly after her return to Britain early in June 1949, Ferrier left for Amsterdam where, on 14 July, she sang in the world premiere of Britten's ''

Ferrier resumed her career on 19 June 1951, in the Mass in B minor at the

Ferrier resumed her career on 19 June 1951, in the Mass in B minor at the

The news of Ferrier's death came as a considerable shock to the public. Although some in musical circles knew or suspected the truth, the myth had been preserved that her absence from the concert scene was temporary. The opera critic

The news of Ferrier's death came as a considerable shock to the public. Although some in musical circles knew or suspected the truth, the myth had been preserved that her absence from the concert scene was temporary. The opera critic

The Kathleen Ferrier Society (KFS)

Flat at Frognal Mansions, Hampstead, with blue plaque

"The Community, Voice and Passion of Kathleen Ferrier: A Critical Outlook on the Legendary English Contralto

by Yakir Ariel, n.d. (2018?) * (brief samples of Ferrier's voice, from a recent CD issue) * (biographical summary.) * (In Dutch, with a synopsis in English, it includes an account of the preparation of the 1951 Holland Festival recording of ''Orfeo ed Euridice'' for release on record.) {{DEFAULTSORT:Ferrier, Kathleen 1912 births 1953 deaths Commanders of the Order of the British Empire Deaths from cancer in England Deaths from breast cancer Decca Records artists English contraltos English opera singers Operatic contraltos People from Blackburn People from Walton-le-Dale Royal Philharmonic Society Gold Medallists Golders Green Crematorium 20th-century British women opera singers

Kathleen Mary Ferrier,

The Ferrier family originally came from

The Ferrier family originally came from

On 10 March 1929 she made a well-received appearance as an accompanist in a concert at Blackburn's King George's Hall. After further piano competition successes she was invited to perform a short radio recital at the

On 10 March 1929 she made a well-received appearance as an accompanist in a concert at Blackburn's King George's Hall. After further piano competition successes she was invited to perform a short radio recital at the

, and on 3 July 1930 made her first broadcast, playing works by CBE

The Most Excellent Order of the British Empire is a British order of chivalry, rewarding contributions to the arts and sciences, work with charitable and welfare organisations,

and public service outside the civil service. It was established o ...

(22 April 19128 October 1953) was an English contralto

A contralto () is a type of classical female singing voice whose vocal range is the lowest female voice type.

The contralto's vocal range is fairly rare; similar to the mezzo-soprano, and almost identical to that of a countertenor, typically b ...

singer who achieved an international reputation as a stage, concert and recording artist, with a repertoire extending from folksong and popular ballads to the classical works of Bach

Johann Sebastian Bach (28 July 1750) was a German composer and musician of the late Baroque period. He is known for his orchestral music such as the '' Brandenburg Concertos''; instrumental compositions such as the Cello Suites; keyboard w ...

, Brahms

Johannes Brahms (; 7 May 1833 – 3 April 1897) was a German composer, pianist, and conductor of the mid-Romantic period. Born in Hamburg into a Lutheran family, he spent much of his professional life in Vienna. He is sometimes grouped with ...

, Mahler

Gustav Mahler (; 7 July 1860 – 18 May 1911) was an Austro-Bohemian Romantic composer, and one of the leading conductors of his generation. As a composer he acted as a bridge between the 19th-century Austro-German tradition and the modernism ...

and Elgar

Sir Edward William Elgar, 1st Baronet, (; 2 June 1857 – 23 February 1934) was an English composer, many of whose works have entered the British and international classical concert repertoire. Among his best-known compositions are orchestr ...

. Her death from cancer, at the height of her fame, was a shock to the musical world and particularly to the general public, which was kept in ignorance of the nature of her illness until after her death.

The daughter of a Lancashire

Lancashire ( , ; abbreviated Lancs) is the name of a historic county, ceremonial county, and non-metropolitan county in North West England. The boundaries of these three areas differ significantly.

The non-metropolitan county of Lancashi ...

village schoolmaster, Ferrier showed early talent as a pianist, and won numerous amateur piano competitions while working as a telephonist with the General Post Office. She did not take up singing seriously until 1937, when after winning a prestigious singing competition at the Carlisle

Carlisle ( , ; from xcb, Caer Luel) is a city that lies within the Northern England, Northern English county of Cumbria, south of the Anglo-Scottish border, Scottish border at the confluence of the rivers River Eden, Cumbria, Eden, River C ...

Festival she began to receive offers of professional engagements as a vocalist. Thereafter she took singing lessons, first with J.E. Hutchinson and later with Roy Henderson. After the outbreak of the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

Ferrier was recruited by the Council for the Encouragement of Music and the Arts (CEMA), and in the following years sang at concerts and recitals throughout the UK. In 1942 her career was boosted when she met the conductor Malcolm Sargent

Sir Harold Malcolm Watts Sargent (29 April 1895 – 3 October 1967) was an English conductor, organist and composer widely regarded as Britain's leading conductor of choral works. The musical ensembles with which he was associated include ...

, who recommended her to the influential Ibbs and Tillett

Ibbs and Tillett was a London-based classical music artist and concert management agency that flourished between 1906 and 1990 in the United Kingdom. It was described as "one of the legendary duos in classical music artist management".

Founding

...

concert management agency. She became a regular performer at leading London and provincial venues, and made numerous BBC radio broadcasts.

In 1946, Ferrier made her stage debut, in the Glyndebourne Festival

Glyndebourne Festival Opera is an annual opera festival held at Glyndebourne, an English country house near Lewes, in East Sussex, England.

History

Under the supervision of the Christie family, the festival has been held annually since 1934, ...

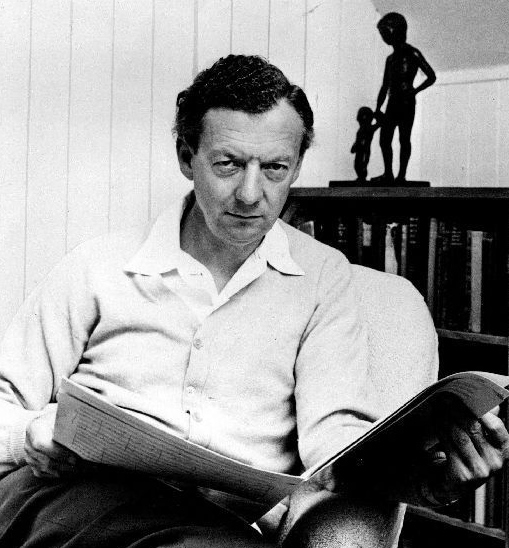

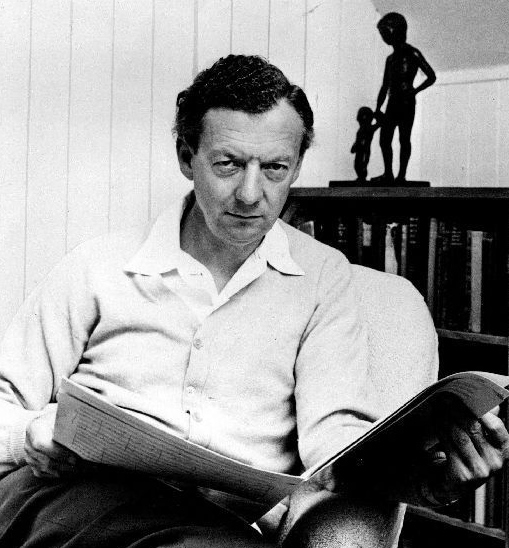

premiere of Benjamin Britten

Edward Benjamin Britten, Baron Britten (22 November 1913 – 4 December 1976, aged 63) was an English composer, conductor, and pianist. He was a central figure of 20th-century British music, with a range of works including opera, other ...

's opera ''The Rape of Lucretia

''The Rape of Lucretia'' (Op. 37) is an opera in two acts by Benjamin Britten, written for Kathleen Ferrier, who performed the title role. Ronald Duncan based his English libretto on André Obey's play '.

Performance history

The opera was fi ...

''. A year later she made her first appearance as Orfeo in Gluck

Christoph Willibald (Ritter von) Gluck (; 2 July 1714 – 15 November 1787) was a composer of Italian and French opera in the early classical period. Born in the Upper Palatinate and raised in Bohemia, both part of the Holy Roman Empire, he g ...

's '' Orfeo ed Euridice'', a work with which she became particularly associated. By her own choice, these were her only two operatic roles. As her reputation grew, Ferrier formed close working relationships with major musical figures, including Britten, Sir John Barbirolli

Sir John Barbirolli ( Giovanni Battista Barbirolli; 2 December 189929 July 1970) was a British conductor and cellist. He is remembered above all as conductor of the Hallé Orchestra in Manchester, which he helped save from dissolution in 194 ...

, Bruno Walter

Bruno Walter (born Bruno Schlesinger, September 15, 1876February 17, 1962) was a German-born conductor, pianist and composer. Born in Berlin, he escaped Nazi Germany in 1933, was naturalised as a French citizen in 1938, and settled in the Un ...

and the accompanist Gerald Moore

Gerald Moore Order of the British Empire, CBE (30 July 1899 – 13 March 1987) was an England, English classical music, classical pianist best known for his career as a Collaborative piano, collaborative pianist for many distinguished musicians. ...

. She became known internationally through her three tours to the United States between 1948 and 1950 and her many visits to continental Europe.

Ferrier was diagnosed with breast cancer

Breast cancer is cancer that develops from breast tissue. Signs of breast cancer may include a lump in the breast, a change in breast shape, dimpling of the skin, milk rejection, fluid coming from the nipple, a newly inverted nipple, or a re ...

in March 1951. In between periods of hospitalisation and convalescence she continued to perform and record; her final public appearance was as Orfeo, at the Royal Opera House

The Royal Opera House (ROH) is an opera house and major performing arts venue in Covent Garden, central London. The large building is often referred to as simply Covent Garden, after a previous use of the site. It is the home of The Royal Op ...

in February 1953, eight months before her death. Among her many memorials, the Kathleen Ferrier Cancer Research Fund was launched in May 1954. The Kathleen Ferrier Scholarship Fund, administered by the Royal Philharmonic Society

The Royal Philharmonic Society (RPS) is a British music society, formed in 1813. Its original purpose was to promote performances of instrumental music in London. Many composers and performers have taken part in its concerts. It is now a memb ...

, has since 1956 made annual awards to aspiring young professional singers.

Early life

Childhood

The Ferrier family originally came from

The Ferrier family originally came from Pembrokeshire

Pembrokeshire ( ; cy, Sir Benfro ) is a Local government in Wales#Principal areas, county in the South West Wales, south-west of Wales. It is bordered by Carmarthenshire to the east, Ceredigion to the northeast, and the rest by sea. The count ...

in South West Wales

South West Wales is one of the regions of Wales consisting of the unitary authorities of Swansea, Neath Port Talbot, Carmarthenshire and Pembrokeshire.

This definition is used by a number of government agencies and private organisations includin ...

. The Lancashire branch originated in the 19th century, when Thomas Ferrier (youngest son of Private Thomas Ferrier of the Pembrokeshire Regiment) settled in the area after being stationed near Blackburn

Blackburn () is an industrial town and the administrative centre of the Blackburn with Darwen borough in Lancashire, England. The town is north of the West Pennine Moors on the southern edge of the Ribble Valley, east of Preston and north-n ...

during a period of industrial unrest.Cardus, pp. 19–20 Kathleen Ferrier was born on 22 April 1912, in the Lancashire village of Higher Walton where her father William Ferrier (the fourth child of Thomas and Elizabeth, née Gorton) was the head of the village school. Although untrained musically, William was an enthusiastic member of the local operatic society and of several choirs, and his wife Alice (née Murray), whom he married in 1900, was a competent singer with a strong contralto voice.Ferrier, pp. 14–16 Kathleen was the third and youngest of the couple's children, following a sister and a brother; when she was two the family moved to Blackburn, after William was appointed headmaster of St Paul's School in the town. From an early age Kathleen showed promise as a pianist, and had lessons with Frances Walker, a noted North of England piano teacher who had been a pupil of Tobias Matthay

Tobias Augustus Matthay (19 February 185815 December 1945) was an English pianist, teacher, and composer.

Biography

Matthay was born in Clapham, Surrey, in 1858 to parents who had come from northern Germany and eventually became naturalised Brit ...

. Kathleen's talent developed quickly; in 1924 she came fourth out of 43 entrants at the Lytham St Annes

Lytham St Annes () is a seaside town in the Borough of Fylde in Lancashire, England. It is on the The Fylde, Fylde coast, directly south of Blackpool on the Ribble Estuary. The population at the United Kingdom Census 2011, 2011 census was 42,954 ...

Festival piano competition, and in the following year at Lytham she achieved second place.

Telephonist and pianist

Because of William's impending retirement and the consequent fall in the family's income, Ferrier's hopes of attending a music college could not be realised. In August 1926 she left school to start work as a trainee at theGPO GPO may refer to:

Government and politics

* General Post Office, Dublin

* General Post Office, in Britain

* Social Security Government Pension Offset, a provision reducing benefits

* Government Pharmaceutical Organization, a Thai state enterpris ...

telephone exchange in Blackburn. She continued her piano studies under Frances Walker, and in November 1928 was the regional winner in a national contest for young pianists, organised by the ''Daily Express

The ''Daily Express'' is a national daily United Kingdom middle-market newspaper printed in tabloid format. Published in London, it is the flagship of Express Newspapers, owned by publisher Reach plc. It was first published as a broadsheet i ...

''. Although unsuccessful in the London finals which followed, Ferrier won a Cramer Cramer may refer to:

Businesses

* Cramer brothers, 18th century publishers

* Cramer Systems, a software company

* Cramer & Co., a former musical-related business in London

Other uses

* Cramer (surname), including a list of people and fictional ...

upright piano as a prize.

On 10 March 1929 she made a well-received appearance as an accompanist in a concert at Blackburn's King George's Hall. After further piano competition successes she was invited to perform a short radio recital at the

On 10 March 1929 she made a well-received appearance as an accompanist in a concert at Blackburn's King George's Hall. After further piano competition successes she was invited to perform a short radio recital at the Manchester

Manchester () is a city in Greater Manchester, England. It had a population of 552,000 in 2021. It is bordered by the Cheshire Plain to the south, the Pennines to the north and east, and the neighbouring city of Salford to the west. The t ...

studios of the BBC #REDIRECT BBC #REDIRECT BBC

Here i going to introduce about the best teacher of my life b BALAJI sir. He is the precious gift that I got befor 2yrs . How has helped and thought all the concept and made my success in the 10th board exam. ...

...Brahms

Johannes Brahms (; 7 May 1833 – 3 April 1897) was a German composer, pianist, and conductor of the mid-Romantic period. Born in Hamburg into a Lutheran family, he spent much of his professional life in Vienna. He is sometimes grouped with ...

and Percy Grainger

Percy Aldridge Grainger (born George Percy Grainger; 8 July 188220 February 1961) was an Australian-born composer, arranger and pianist who lived in the United States from 1914 and became an American citizen in 1918. In the course of a long an ...

. Around this time she completed her training and she became a fully fledged telephonist.Ferrier, p. 30

In 1931, aged 19, Ferrier passed her Licentiate examinations at the Royal Academy of Music

The Royal Academy of Music (RAM) in London, England, is the oldest conservatoire in the UK, founded in 1822 by John Fane and Nicolas-Charles Bochsa. It received its royal charter in 1830 from King George IV with the support of the first Duke of ...

. In that year she started occasional singing lessons, and in December sang a small alto role in a church performance of Mendelssohn

Jakob Ludwig Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy (3 February 18094 November 1847), born and widely known as Felix Mendelssohn, was a German composer, pianist, organist and conductor of the early Romantic period. Mendelssohn's compositions include sym ...

's oratorio ''Elijah

Elijah ( ; he, אֵלִיָּהוּ, ʾĒlīyyāhū, meaning "My God is Yahweh/YHWH"; Greek form: Elias, ''Elías''; syr, ܐܸܠܝܼܵܐ, ''Elyāe''; Arabic: إلياس or إليا, ''Ilyās'' or ''Ilyā''. ) was, according to the Books of ...

''. However, her voice was not thought to be exceptional; her musical life centred on the piano and on local concerts, at King George's Hall and elsewhere.Leonard, pp. 19–20 Early in 1934 she transferred to the Blackpool

Blackpool is a seaside resort in Lancashire, England. Located on the North West England, northwest coast of England, it is the main settlement within the Borough of Blackpool, borough also called Blackpool. The town is by the Irish Sea, betw ...

telephone exchange and took lodgings nearby, to be close to her new boyfriend, a bank clerk named Albert Wilson. While at Blackpool she auditioned for the new "speaking clock" service which the GPO was preparing to introduce. In her excitement, Ferrier inserted an extra aspirate into her audition, and was not chosen for the final selection in London. Her decision in 1935 to marry Wilson meant the end of her employment with the telephone exchange, since at that time the GPO did not employ married women. Of Ferrier's career to this point, the music biographer Humphrey Burton

Humphrey is both a masculine given name and a surname. An earlier form, not attested since Medieval times, was Hunfrid.

Notable people with the name include:

People with the given name Medieval period

:''Ordered chronologically''

*Hunfrid of P ...

wrote: "For more than a decade, when she should have been studying music with the best teachers, learning English literature and foreign languages, acquiring stage craft and movement skills, and travelling to London regularly to see opera, Miss Ferrier was actually answering the telephone, getting married to a bank manager and winning tinpot competitions for her piano-playing."

Marriage

Ferrier met Albert Wilson in 1933, probably through dancing, which they both loved. When she announced that they were to marry, her family and friends had strong reservations, on the grounds that she was young and inexperienced, and that she and Wilson shared few serious interests. Nevertheless, the marriage took place on 19 November 1935. Shortly afterwards the couple moved toSilloth

Silloth (sometimes known as Silloth-on-Solway) is a port town and civil parish in the Allerdale borough of Cumbria, England. Historically in the county of Cumberland, the town is an example of a Victorian seaside resort in the North of Engl ...

, a small port town in Cumberland

Cumberland ( ) is a historic county in the far North West England. It covers part of the Lake District as well as the north Pennines and Solway Firth coast. Cumberland had an administrative function from the 12th century until 1974. From 19 ...

, where Wilson had been appointed as manager of his bank's branch. The marriage was not successful; the honeymoon had revealed problems of sexual incompatibility, and the union remained unconsummated.Leonard, pp. 26–28 Outward appearances were maintained for a few years, until Wilson's departure for military service in 1940 effectively ended the marriage. The couple divorced in 1947, though they remained on good terms. Wilson subsequently married a friend of Ferrier's, Wyn Hetherington; he died in 1969.

Early singing career

In 1937 Ferrier entered the Carlisle Festival open piano competition and, as a result of a small bet with her husband, also signed up for the singing contest. She easily won the piano trophy; in the singing finals she sangRoger Quilter

Roger Cuthbert Quilter (1 November 1877 – 21 September 1953) was a British composer, known particularly for his art songs. His songs, which number over a hundred, often set music to text by William Shakespeare and are a mainstay of the En ...

's ''To Daisies'', a performance which earned her the festival's top vocal award. To mark her double triumph in piano and voice, Ferrier was awarded a special rose bowl as champion of the festival.

After her Carlisle victories, Ferrier began to receive offers of singing engagements. Her first appearance as a professional vocalist, in autumn 1937, was at a

After her Carlisle victories, Ferrier began to receive offers of singing engagements. Her first appearance as a professional vocalist, in autumn 1937, was at a harvest festival

A harvest festival is an annual celebration that occurs around the time of the main harvest of a given region. Given the differences in climate and crops around the world, harvest festivals can be found at various times at different places. ...

celebration in the village church at Aspatria.Leonard, p. 33 She was paid one guinea

Guinea ( ),, fuf, 𞤘𞤭𞤲𞤫, italic=no, Gine, wo, Gine, nqo, ߖߌ߬ߣߍ߫, bm, Gine officially the Republic of Guinea (french: République de Guinée), is a coastal country in West Africa. It borders the Atlantic Ocean to the we ...

. After winning the gold cup at the 1938 Workington

Workington is a coastal town and civil parish at the mouth of the River Derwent on the west coast in the Allerdale borough of Cumbria, England. The town was historically in Cumberland. At the 2011 census it had a population of 25,207.

Loca ...

Festival, Ferrier sang "Ma Curly-Headed Babby" in a concert at Workington Opera House. Cecil McGivern

Cecil McGivern CBE (22 May 1907, in Newcastle, England – 30 January 1963, in Buckinghamshire, England) was a British broadcasting executive, who initially worked for BBC Radio before transferring to BBC Television in the late 1940s. From 1950 ...

, producer of a BBC Northern radio variety show, was in the audience and was sufficiently impressed to book her for the next edition of his programme, which was broadcast from Newcastle Newcastle usually refers to:

*Newcastle upon Tyne, a city and metropolitan borough in Tyne and Wear, England

*Newcastle-under-Lyme, a town in Staffordshire, England

*Newcastle, New South Wales, a metropolitan area in Australia, named after Newcastle ...

on 23 February 1939. This broadcast—her first as a vocalist—attracted wide attention, and led to more radio work, though for Ferrier the event was overshadowed by the death of her mother at the beginning of February.Ferrier, pp. 39–40 At the 1939 Carlisle Festival, Ferrier sang Richard Strauss

Richard Georg Strauss (; 11 June 1864 – 8 September 1949) was a German composer, conductor, pianist, and violinist. Considered a leading composer of the late Romantic and early modern eras, he has been described as a successor of Richard Wag ...

's song ''All Souls' Day'', a performance which particularly impressed one of the adjudicators, J. E. Hutchinson, a music teacher with a considerable reputation. Ferrier became his pupil and, under his guidance, began to extend her repertoire to include works by Bach

Johann Sebastian Bach (28 July 1750) was a German composer and musician of the late Baroque period. He is known for his orchestral music such as the '' Brandenburg Concertos''; instrumental compositions such as the Cello Suites; keyboard w ...

, Handel

George Frideric (or Frederick) Handel (; baptised , ; 23 February 1685 – 14 April 1759) was a German-British Baroque composer well known for his operas, oratorios, anthems, concerti grossi, and organ concertos. Handel received his training i ...

, Brahms and Elgar

Sir Edward William Elgar, 1st Baronet, (; 2 June 1857 – 23 February 1934) was an English composer, many of whose works have entered the British and international classical concert repertoire. Among his best-known compositions are orchestr ...

.

When Albert Wilson joined the army in 1940, Ferrier reverted to her maiden name, having until then sung as 'Kathleen Wilson'. In December 1940 she appeared for the first time professionally as 'Kathleen Ferrier' in a performance of Handel's ''Messiah

In Abrahamic religions, a messiah or messias (; ,

; ,

; ) is a saviour or liberator of a group of people. The concepts of ''mashiach'', messianism, and of a Messianic Age originated in Judaism, and in the Hebrew Bible, in which a ''mashiach'' ...

'', under Hutchinson's direction. In early 1941 she successfully auditioned as a singer with the Council for the Encouragement of the Arts (CEMA), which provided concerts and other entertainments to military camps, factories and other workplaces. Within this organisation Ferrier began working with artists with international reputations; in December 1941 she sang with the Hallé Orchestra in a performance of ''Messiah'' together with Isobel Baillie

Isobel Baillie, (9 March 189524 September 1983), ''née'' Isabella Douglas Baillie, was a Scottish soprano. She made a local success in Manchester, where she was brought up, and in 1923 made a successful London debut. Her career, encouraged by ...

, the distinguished soprano

A soprano () is a type of classical female singing voice and has the highest vocal range of all voice types. The soprano's vocal range (using scientific pitch notation) is from approximately middle C (C4) = 261 Hz to "high A" (A5) = 880&n ...

. However, her application to the BBC's head of music in Manchester for an audition was turned down.Fifield (ed.), p. 17 Ferrier had better fortune when she was introduced to Malcolm Sargent

Sir Harold Malcolm Watts Sargent (29 April 1895 – 3 October 1967) was an English conductor, organist and composer widely regarded as Britain's leading conductor of choral works. The musical ensembles with which he was associated include ...

after a Hallé concert in Blackpool. Sargent agreed to hear her sing, and afterwards recommended her to Ibbs and Tillett

Ibbs and Tillett was a London-based classical music artist and concert management agency that flourished between 1906 and 1990 in the United Kingdom. It was described as "one of the legendary duos in classical music artist management".

Founding

...

, the London-based concert management agency. John Tillett accepted her as a client without hesitation after which, on Sargent's advice, Ferrier decided to base herself in London. On 24 December 1942 she moved with her sister Winifred into a flat in Frognal Mansions, Hampstead

Hampstead () is an area in London, which lies northwest of Charing Cross, and extends from Watling Street, the A5 road (Roman Watling Street) to Hampstead Heath, a large, hilly expanse of parkland. The area forms the northwest part of the Lon ...

.

Stardom

Growing reputation

Ferrier gave her first London recital on 28 December 1942 at theNational Gallery

The National Gallery is an art museum in Trafalgar Square in the City of Westminster, in Central London, England. Founded in 1824, it houses a collection of over 2,300 paintings dating from the mid-13th century to 1900. The current Director o ...

, in a lunch-time concert organised by Dame Myra Hess.Leonard, pp. 50–51 Although she wrote "went off very well" in her diary, Ferrier was disappointed with her performance, and concluded that she needed further voice training. She approached the distinguished baritone Roy Henderson with whom, a week previously, she had sung in Mendelssohn's ''Elijah''. Henderson agreed to teach her, and was her regular voice coach for the remainder of her life. He later explained that her "warm and spacious tone" was in part due to the size of the cavity at the back of her throat: "one could have shot a fair-sized apple right to the back of the throat without obstruction". However, this natural physical advantage was not in itself enough to ensure the quality of her voice; this was due, Henderson says, to "her hard work, artistry, sincerity, personality and above all her character".

On 17 May 1943 Ferrier sang in Handel's ''Messiah'' at

On 17 May 1943 Ferrier sang in Handel's ''Messiah'' at Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an historic, mainly Gothic church in the City of Westminster, London, England, just to the west of the Palace of Westminster. It is one of the United ...

, alongside Isobel Baillie and Peter Pears

Sir Peter Neville Luard Pears ( ; 22 June 19103 April 1986) was an English tenor. His career was closely associated with the composer Benjamin Britten, his personal and professional partner for nearly forty years.

Pears' musical career started ...

, with Reginald Jacques

Thomas Reginald Jacques (13 January 1894 – 2 June 1969) was an English choral and orchestral conductor. His legacy includes various choral music arrangements, but he is not primarily remembered as a composer.

Jacques was born in Ashby-de ...

conducting. According to the critic Neville Cardus

Sir John Frederick Neville Cardus, Commander of the Order of the British Empire, CBE (2 April 188828 February 1975) was an English writer and critic. From an impoverished home background, and mainly self-educated, he became ''The Manchester Gua ...

, it was through the quality of her singing here that Ferrier "made her first serious appeal to musicians". Her assured performance led to other important engagements, and to broadcasting work; her increasingly frequent appearances on popular programmes such as ''Forces Favourites'' and ''Housewives' Choice

''Housewives' Choice'' was a BBC Radio record request programme, broadcast every morning between 1946 and 1967 on the BBC Light Programme. It played a wide range of mostly popular music intended to appeal to housewives at home during the day. ...

'' soon gave her national recognition. In May 1944, at EMI's Abbey Road Studios with Gerald Moore

Gerald Moore Order of the British Empire, CBE (30 July 1899 – 13 March 1987) was an England, English classical music, classical pianist best known for his career as a Collaborative piano, collaborative pianist for many distinguished musicians. ...

as her accompanist, she made test recordings of music by Brahms, Gluck

Christoph Willibald (Ritter von) Gluck (; 2 July 1714 – 15 November 1787) was a composer of Italian and French opera in the early classical period. Born in the Upper Palatinate and raised in Bohemia, both part of the Holy Roman Empire, he g ...

and Elgar. Her first published record, made in September 1944, was issued under the Columbia label; it consisted of two songs by Maurice Greene, again with Moore accompanying. Her time as a Columbia recording artist was brief and unhappy; she had poor relations with her producer, Walter Legge

Harry Walter Legge (1 June 1906 – 22 March 1979) was an English classical music record producer, most especially associated with EMI. His recordings include many sets later regarded as classics and reissued by EMI as "Great Recordings of the ...

, and after a few months she transferred to Decca Decca may refer to:

Music

* Decca Records or Decca Music Group, a record label

* Decca Gold, a classical music record label owned by Universal Music Group

* Decca Broadway, a musical theater record label

* Decca Studios, a recording facility in W ...

.

In the remaining wartime months Ferrier continued to travel throughout the country, to fulfil the growing demands for her services from concert promoters. At Leeds in November 1944 she sang the part of the Angel in Elgar's choral work ''The Dream of Gerontius

''The Dream of Gerontius'', Op. 38, is a work for voices and orchestra in two parts composed by Edward Elgar in 1900, to text from the poem by John Henry Newman. It relates the journey of a pious man's soul from his deathbed to his judgment b ...

'', her first performance in what became one of her best-known roles. In December she met John Barbirolli

Sir John Barbirolli ( Giovanni Battista Barbirolli; 2 December 189929 July 1970) was a British conductor and cellist. He is remembered above all as conductor of the Hallé Orchestra in Manchester, which he helped save from dissolution in 194 ...

while working on another Elgar piece, ''Sea Pictures

''Sea Pictures, Op. 37'' is a song cycle by Sir Edward Elgar consisting of five songs written by various poets. It was set for contralto and orchestra, though a distinct version for piano was often performed by Elgar. Many mezzo-sopranos have su ...

''; the conductor later became one of her closest friends and strongest advocates. On 15 September 1945 Ferrier made her debut at the London Proms

The BBC Proms or Proms, formally named the Henry Wood Promenade Concerts Presented by the BBC, is an eight-week summer season of daily orchestral classical music concerts and other events held annually, predominantly in the Royal Albert Hal ...

, when she sang ''L'Air des Adieux'' from Tchaikovsky

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky , group=n ( ; 7 May 1840 – 6 November 1893) was a Russian composer of the Romantic period. He was the first Russian composer whose music would make a lasting impression internationally. He wrote some of the most popu ...

's opera '' The Maid of Orleans''. Although she often sang individual aria

In music, an aria (Italian: ; plural: ''arie'' , or ''arias'' in common usage, diminutive form arietta , plural ariette, or in English simply air) is a self-contained piece for one voice, with or without instrumental or orchestral accompanime ...

s, opera was not Ferrier's natural forte; she had not enjoyed singing the title role in a concert version of Bizet

Georges Bizet (; 25 October 18383 June 1875) was a French composer of the Romantic era. Best known for his operas in a career cut short by his early death, Bizet achieved few successes before his final work, '' Carmen'', which has become o ...

's ''Carmen

''Carmen'' () is an opera in four acts by the French composer Georges Bizet. The libretto was written by Henri Meilhac and Ludovic Halévy, based on the Carmen (novella), novella of the same title by Prosper Mérimée. The opera was first perfo ...

'' at Stourbridge

Stourbridge is a market town in the Metropolitan Borough of Dudley in the West Midlands, England, situated on the River Stour. Historically in Worcestershire, it was the centre of British glass making during the Industrial Revolution. The 20 ...

in March 1944, and generally avoided similar engagements. Nevertheless, Benjamin Britten

Edward Benjamin Britten, Baron Britten (22 November 1913 – 4 December 1976, aged 63) was an English composer, conductor, and pianist. He was a central figure of 20th-century British music, with a range of works including opera, other ...

, who had heard her Westminster Abbey ''Messiah'' performance, persuaded her to create the role of Lucretia in his new opera ''The Rape of Lucretia

''The Rape of Lucretia'' (Op. 37) is an opera in two acts by Benjamin Britten, written for Kathleen Ferrier, who performed the title role. Ronald Duncan based his English libretto on André Obey's play '.

Performance history

The opera was fi ...

'', which was to open the first postwar Glyndebourne Festival

Glyndebourne Festival Opera is an annual opera festival held at Glyndebourne, an English country house near Lewes, in East Sussex, England.

History

Under the supervision of the Christie family, the festival has been held annually since 1934, ...

in 1946. She would share the part with Nancy Evans.Britten, pp. 83–85 Despite her initial misgivings, by early July Ferrier was writing to her agent that she was "enjoying he rehearsalstremendously and I should think it's the best part one could possibly have".

Ferrier's performances in the Glyndebourne run, which began on 12 July 1946, earned her favourable reviews, although the opera itself was less well received. On the provincial tour which followed the festival it failed to attract the public and incurred heavy financial losses.

By contrast, when the opera reached Amsterdam it was greeted warmly by the Dutch audiences who showed particular enthusiasm for Ferrier's performance. This was Ferrier's first trip abroad, and she wrote an excited letter to her family: "The cleanest houses and windows you ever did see, and flowers in the fields all the way!" Following her success as Lucretia she agreed to return to Glyndebourne in 1947, to sing Orfeo in Gluck's opera '' Orfeo ed Euridice''. She had often sung Orfeo's aria ''Che farò'' ("What is life") as a concert piece, and had recently recorded it with Decca. At Glyndebourne, Ferrier's limited acting abilities caused some difficulties in her relationship with the conductor,

Ferrier's performances in the Glyndebourne run, which began on 12 July 1946, earned her favourable reviews, although the opera itself was less well received. On the provincial tour which followed the festival it failed to attract the public and incurred heavy financial losses.

By contrast, when the opera reached Amsterdam it was greeted warmly by the Dutch audiences who showed particular enthusiasm for Ferrier's performance. This was Ferrier's first trip abroad, and she wrote an excited letter to her family: "The cleanest houses and windows you ever did see, and flowers in the fields all the way!" Following her success as Lucretia she agreed to return to Glyndebourne in 1947, to sing Orfeo in Gluck's opera '' Orfeo ed Euridice''. She had often sung Orfeo's aria ''Che farò'' ("What is life") as a concert piece, and had recently recorded it with Decca. At Glyndebourne, Ferrier's limited acting abilities caused some difficulties in her relationship with the conductor, Fritz Stiedry

Fritz Stiedry (11 October 18838 August 1968) was an Austrian conductor and composer.

Biography

Fritz Stiedry was born in Vienna in 1883. While still a law student at the University of Vienna, Stiedry's talent for music was noticed by Gustav Mahl ...

; nevertheless her performance on the first night, 19 June 1947, attracted warm critical praise.

Ferrier's association with Glyndebourne bore further fruit when Rudolf Bing

Sir Rudolf Bing, KBE (January 9, 1902 – September 2, 1997) was an Austrian-born British opera impresario who worked in Germany, the United Kingdom and the United States, most notably being General Manager of the Metropolitan Opera in New York ...

, the festival's general manager, recommended her to Bruno Walter

Bruno Walter (born Bruno Schlesinger, September 15, 1876February 17, 1962) was a German-born conductor, pianist and composer. Born in Berlin, he escaped Nazi Germany in 1933, was naturalised as a French citizen in 1938, and settled in the Un ...

as the contralto soloist in a performance of Mahler

Gustav Mahler (; 7 July 1860 – 18 May 1911) was an Austro-Bohemian Romantic composer, and one of the leading conductors of his generation. As a composer he acted as a bridge between the 19th-century Austro-German tradition and the modernism ...

's symphonic song cycle ''Das Lied von der Erde

''Das Lied von der Erde'' ("The Song of the Earth") is an orchestral song cycle for two voices and orchestra written by Gustav Mahler between 1908 and 1909. Described as a symphony when published, it comprises six songs for two singers who alte ...

''. This was planned for the 1947 Edinburgh International Festival

The Edinburgh International Festival is an annual arts festival in Edinburgh, Scotland, spread over the final three weeks in August. Notable figures from the international world of music (especially classical music) and the performing arts are i ...

. Walter was initially wary of working with a relatively new singer, but after her audition his fears were allayed; "I recognised with delight that here potentially was one of the greatest singers of our time", he later wrote. ''Das Lied von der Erde'' was at that time largely unknown in Britain, and some critics found it unappealing; nevertheless, the ''Edinburgh Evening News'' thought it "simply superb". In a later biographical sketch of Ferrier, Lord Harewood

Earl of Harewood (), in the County of York, is a title in the Peerage of the United Kingdom.

History

The title was created in 1812 for Edward Lascelles, 1st Baron Harewood, a wealthy sugar plantation owner and former Member of Parliament for ...

described the partnership between Walter and her, which endured until the singer's final illness, as "a rare match of music, voice and temperament."

Career apex, 1948–51

On 1 January 1948 Ferrier left for a four-week tour of North America, the first of three transatlantic trips she would make during the next three years. In New York she sang two performances of ''Das Lied von der Erde'', with Bruno Walter and the

On 1 January 1948 Ferrier left for a four-week tour of North America, the first of three transatlantic trips she would make during the next three years. In New York she sang two performances of ''Das Lied von der Erde'', with Bruno Walter and the New York Philharmonic

The New York Philharmonic, officially the Philharmonic-Symphony Society of New York, Inc., globally known as New York Philharmonic Orchestra (NYPO) or New York Philharmonic-Symphony Orchestra, is a symphony orchestra based in New York City. It is ...

. Alma Mahler

Alma Maria Mahler Gropius Werfel (born Alma Margaretha Maria Schindler; 31 August 1879 – 11 December 1964) was an Austrian composer, author, editor, and socialite. At 15, she was mentored by Max Burckhard. Musically active from her early yea ...

, the composer's widow, was present at the first of these, on 15 January. In a letter written the following day, Ferrier told her sister: "Some of the critics are enthusiastic, others unimpressed". After the second performance, which was broadcast from coast to coast, Ferrier gave recitals in Ottawa

Ottawa (, ; Canadian French: ) is the capital city of Canada. It is located at the confluence of the Ottawa River and the Rideau River in the southern portion of the province of Ontario. Ottawa borders Gatineau, Quebec, and forms the core ...

and Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name ...

before returning to New York and embarking for home on 4 February.

During 1948, amid many engagements, Ferrier performed Brahms's ''Alto Rhapsody

The ''Alto Rhapsody'', Op. 53, is a composition for contralto, male chorus, and orchestra by Johannes Brahms, a setting of verses from Johann Wolfgang von Goethe's '' Harzreise im Winter''. It was written in 1869, as a wedding gift for Robert ...

'' at the Proms in August, and sang in Bach's Mass in B minor

The Mass in B minor (), BWV 232, is an extended setting of the Mass ordinary by Johann Sebastian Bach. The composition was completed in 1749, the year before the composer's death, and was to a large extent based on earlier work, such as a Sanctu ...

at that year's Edinburgh Festival. On 13 October she joined Barbirolli and the Hallé Orchestra in a broadcast performance of Mahler's song cycle ''Kindertotenlieder

(''Songs on the Death of Children'') is a song cycle (1904) for voice and orchestra by Gustav Mahler. The words of the songs are poems by Friedrich Rückert.

Text and music

The original were a group of 428 poems written by Rückert in 1833� ...

''. She returned to the Netherlands in January 1949 for a series of recitals, then left Southampton

Southampton () is a port city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire in southern England. It is located approximately south-west of London and west of Portsmouth. The city forms part of the South Hampshire built-up area, which also covers Po ...

on 18 February to begin her second American tour. This opened in New York with a concert performance of ''Orfeo ed Euridice'' that won uniform critical praise from the New York critics. On the tour which followed, her accompanist was Arpád Sándor (1896–1972), who was suffering from a depressive illness that badly affected his playing. Unaware of his problem, in letters home Ferrier berated "this abominable accompanist" who deserved "a kick in the pants". When she found out that he had been ill for months, she turned her fury on the tour's promoters: "What a blinking nerve to palm him on to me". Eventually, when Sándor was too ill to appear, Ferrier was able to recruit a Canadian pianist, John Newmark, with whom she formed a warm and lasting working relationship.

Shortly after her return to Britain early in June 1949, Ferrier left for Amsterdam where, on 14 July, she sang in the world premiere of Britten's ''

Shortly after her return to Britain early in June 1949, Ferrier left for Amsterdam where, on 14 July, she sang in the world premiere of Britten's ''Spring Symphony

The Spring Symphony is a choral symphony by Benjamin Britten, his Opus 44. It is dedicated to Serge Koussevitzky and the Boston Symphony Orchestra. It was premiered in the Concertgebouw, Amsterdam, on Thursday 14 July 1949 (not 9 July which is ...

'', with Eduard van Beinum

Eduard Alexander van Beinum (; 3 September 1900 – 13 April 1959, Amsterdam) was a Dutch conductor.

Biography

Van Beinum was born in Arnhem, Netherlands, where he received his first violin and piano lessons at an early age. He joined the A ...

and the Concertgebouw Orchestra

The Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra ( nl, Koninklijk Concertgebouworkest, ) is a Dutch symphony orchestra, based at the Amsterdam Royal Concertgebouw (concert hall). Considered one of the world's leading orchestras, Queen Beatrix conferred the "R ...

. Britten had written this work specifically for her. At the Edinburgh Festival in September she gave two recitals in which Bruno Walter acted as her piano accompanist. Ferrier felt that these recitals represented "a peak to which I had been groping for the last three years". A broadcast of one of the recitals was issued on record many years later; of this, the critic Alan Blyth

Geoffrey Alan Blyth (27 July 1929 – 14 August 2007) was an English music critic, author, and musicologist who was particularly known for his writings within the field of opera. He was a specialist on singers and singing. Born in London, Blyt ...

wrote: "Walter's very personal and positive support obviously pushes Ferrier to give of her very best".

The following 18 months saw almost uninterrupted activity, encompassing a number of visits to continental Europe and a third American tour between December 1949 and April 1950. This American trip broke new ground for Ferrier—the West Coast West Coast or west coast may refer to:

Geography Australia

* Western Australia

*Regions of South Australia#Weather forecasting, West Coast of South Australia

* West Coast, Tasmania

**West Coast Range, mountain range in the region

Canada

* Britis ...

—and included three performances in San Francisco of ''Orfeo ed Euridice'', with Pierre Monteux

Pierre Benjamin Monteux (; 4 April 18751 July 1964) was a French (later American) conductor. After violin and viola studies, and a decade as an orchestral player and occasional conductor, he began to receive regular conducting engagements in ...

conducting. At the rehearsals Ferrier met the renowned American contralto Marian Anderson

Marian Anderson (February 27, 1897April 8, 1993) was an American contralto. She performed a wide range of music, from opera to Spiritual (music), spirituals. Anderson performed with renowned orchestras in major concert and recital venues throu ...

, who reportedly said of her English counterpart: "My God, what a voice—and what a face!" On Ferrier's return home the hectic pace continued, with a rapid succession of concerts in Amsterdam, London and Edinburgh followed by a tour of Austria, Switzerland and Italy. In Vienna, the soprano Elisabeth Schwarzkopf

Dame Olga Maria Elisabeth Friederike Schwarzkopf, (9 December 19153 August 2006) was a German-born Austro-British soprano. She was among the foremost singers of lieder, and is renowned for her performances of Viennese operetta, as well as the op ...

was Ferrier's co-soloist in a recorded performance of Bach's Mass in B minor, with the Vienna Symphony

The Vienna Symphony (Vienna Symphony Orchestra, german: Wiener Symphoniker) is an Austrian orchestra based in Vienna. Its primary concert venue is the Konzerthaus, Vienna, Vienna Konzerthaus. In Vienna, the orchestra also performs at the Musikv ...

under Herbert von Karajan

Herbert von Karajan (; born Heribert Ritter von Karajan; 5 April 1908 – 16 July 1989) was an Austrian conductor. He was principal conductor of the Berlin Philharmonic for 34 years. During the Nazi era, he debuted at the Salzburg Festival, wit ...

. Schwarzkopf later recalled Ferrier's singing of the ''Agnus Dei'' from the ''Mass'' as her highlight of the year.

Early in 1951, while on tour in Rome, Ferrier learned of her father's death at the age of 83. Although she was upset by this news, she decided to continue with the tour; her diary entry for 30 January reads: "My Pappy died peacefully after flu and a slight stroke". She returned to London on 19 February, and was immediately busy rehearsing with Barbirolli and the Hallé a work that was new to her: Ernest Chausson

Amédée-Ernest Chausson (; 20 January 1855 – 10 June 1899) was a French Romantic composer who died just as his career was beginning to flourish.

Life

Born in Paris into an affluent bourgeois family, Chausson was the sole surviving child of a ...

's ''Poème de l'amour et de la mer

The ''Poème de l'amour et de la mer'' (literally, ''Poem of Love and the Sea''), Op. 19, is a song cycle for voice and orchestra by Ernest Chausson. It was composed over an extended period between 1882 and 1892 and dedicated to Henri Duparc. C ...

''. This was performed at Manchester on 28 February, to critical acclaim. Two weeks later Ferrier discovered a lump on her breast. She nevertheless fulfilled several engagements in Germany, the Netherlands and at Glyndebourne before seeing her doctor on 24 March. After tests at University College Hospital

University College Hospital (UCH) is a teaching hospital in the Fitzrovia area of the London Borough of Camden, England. The hospital, which was founded as the North London Hospital in 1834, is closely associated with University College London ...

, cancer of the breast was diagnosed, and a mastectomy

Mastectomy is the medical term for the surgical removal of one or both breasts, partially or completely. A mastectomy is usually carried out to treat breast cancer. In some cases, women believed to be at high risk of breast cancer have the operat ...

was performed on 10 April. All immediate engagements were cancelled; among these was a planned series of performances of ''The Rape of Lucretia'' by the English Opera Group

The English Opera Group was a small company of British musicians formed in 1947 by the composer Benjamin Britten (along with John Piper, Eric Crozier and Anne Wood) for the purpose of presenting his and other, primarily British, composers' operat ...

, scheduled as part of the 1951 Festival of Britain

The Festival of Britain was a national exhibition and fair that reached millions of visitors throughout the United Kingdom in the summer of 1951. Historian Kenneth O. Morgan says the Festival was a "triumphant success" during which people:

...

.

Later career

Failing health

Royal Albert Hall

The Royal Albert Hall is a concert hall on the northern edge of South Kensington, London. One of the UK's most treasured and distinctive buildings, it is held in trust for the nation and managed by a registered charity which receives no govern ...

. She then made her usual visit to the Holland Festival

The Holland Festival () is the oldest and largest performing arts festival in the Netherlands. It takes place every June in Amsterdam. It comprises theatre, music, opera and modern dance. In recent years, multimedia, visual arts, film and archit ...

, where she gave four performances of ''Orfeo'', and sang in Mahler's Second Symphony with Otto Klemperer

Otto Nossan Klemperer (14 May 18856 July 1973) was a 20th-century conductor and composer, originally based in Germany, and then the US, Hungary and finally Britain. His early career was in opera houses, but he was later better known as a concer ...

and the Concertgebouw Orchestra. Through the summer her concert schedule was interspersed with hospital visits; however, she was well enough to sing at the Edinburgh Festival in September, where she performed two recitals with Walter and sang Chausson's ''Poème'' with Barbirolli and the Hallé. In November she sang ''Land of Hope and Glory

"Land of Hope and Glory" is a British patriotic song, with music by Edward Elgar written in 1901 and lyrics by A. C. Benson later added in 1902.

Composition

The music to which the words of the refrain 'Land of Hope and Glory, &c' below ar ...

'' at the reopening of Manchester's Free Trade Hall

The Free Trade Hall on Peter Street, Manchester, England, was constructed in 1853–56 on St Peter's Fields, the site of the Peterloo Massacre. It is now a Radisson hotel.

The hall was built to commemorate the repeal of the Corn Laws in 1846. T ...

, a climax to the evening which, wrote Barbirolli, "moved everyone, not least the conductor, to tears". After this, Ferrier rested for two months while she underwent radiation therapy

Radiation therapy or radiotherapy, often abbreviated RT, RTx, or XRT, is a therapy using ionizing radiation, generally provided as part of cancer treatment to control or kill malignant cells and normally delivered by a linear accelerator. Radia ...

; her only work engagement during December was a three-day recording session of folk songs at the Decca studios.

In January 1952 Ferrier joined Britten and Pears in a short series of concerts to raise funds for Britten's English Opera Group, including the premiere of Britten's '' Canticle II: Abraham and Isaac''. Writing later, Britten recalled this tour as "perhaps the loveliest of all" of his artistic associations with Ferrier. Despite continuing health problems, she sang in Bach's ''St Matthew Passion

The ''St Matthew Passion'' (german: Matthäus-Passion, links=-no), BWV 244, is a '' Passion'', a sacred oratorio written by Johann Sebastian Bach in 1727 for solo voices, double choir and double orchestra, with libretto by Picander. It sets ...

'' at the Royal Albert Hall on 30 March, ''Messiah'' at the Free Trade Hall on 13 April, and ''Das Lied von der Erde'' with Barbirolli and the Hallé on 23 and 24 April.Fifield (ed.), p. 296 On 30 April Ferrier attended a private party at which the new Queen, Elizabeth II

Elizabeth II (Elizabeth Alexandra Mary; 21 April 1926 – 8 September 2022) was Queen of the United Kingdom and other Commonwealth realms from 6 February 1952 until her death in 2022. She was queen regnant of 32 sovereign states during ...

, and her sister, Princess Margaret

Princess Margaret, Countess of Snowdon, (Margaret Rose; 21 August 1930 – 9 February 2002) was the younger daughter of King George VI and Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother, and the younger sister and only sibling of Queen Elizabeth ...

, were present. In her diary, Ferrier notes: "Princess M sang—''very'' good!". Her health continued to deteriorate; she refused to consider a course of androgen

An androgen (from Greek ''andr-'', the stem of the word meaning "man") is any natural or synthetic steroid hormone that regulates the development and maintenance of male characteristics in vertebrates by binding to androgen receptors. This inc ...

injections, believing that this treatment would destroy the quality of her voice. In May she travelled to Vienna to record ''Das Lied'' and Mahler's ''Rückert-Lieder

' (Songs after Rückert) is a collection of five Lieder for voice and orchestra or piano by Gustav Mahler, based on poems written by Friedrich Rückert. The songs were first published in ''Sieben Lieder aus letzter Zeit'' (''Seven Songs of Latter ...

'' with Walter and the Vienna Philharmonic

The Vienna Philharmonic (VPO; german: Wiener Philharmoniker, links=no) is an orchestra that was founded in 1842 and is considered to be one of the finest in the world.

The Vienna Philharmonic is based at the Musikverein in Vienna, Austria. It ...

; singer and conductor had long sought to preserve their partnership on disc. Despite considerable suffering, Ferrier completed the recording sessions between 15 and 20 May.

During the remainder of 1952 Ferrier attended her seventh successive Edinburgh Festival, singing in performances of ''Das Lied'', ''The Dream of Gerontius'', ''Messiah'' and some Brahms songs. She undertook several studio recording sessions, including a series of Bach and Handel arias with Sir Adrian Boult

Sir Adrian Cedric Boult, Order of the Companions of Honour, CH (; 8 April 1889 – 22 February 1983) was an English conductor. Brought up in a prosperous mercantile family, he followed musical studies in England and at Leipzig, Germany, wi ...

and the London Philharmonic Orchestra

The London Philharmonic Orchestra (LPO) is one of five permanent symphony orchestras based in London. It was founded by the conductors Sir Thomas Beecham and Malcolm Sargent in 1932 as a rival to the existing London Symphony and BBC Symphony ...

in October. In November, after a Royal Festival Hall

The Royal Festival Hall is a 2,700-seat concert, dance and talks venue within Southbank Centre in London. It is situated on the South Bank of the River Thames, not far from Hungerford Bridge, in the London Borough of Lambeth. It is a Grade I l ...

recital, she was distressed by a review in which Neville Cardus criticised her performance for introducing "distracting extra vocal appeals" designed to please the audience at the expense of the songs. However, she accepted his comments with good grace, remarking that "... it's hard to please everybody—for years I've been criticised for being a colourless, monotonous singer". In December she sang in the BBC's Christmas ''Messiah'', the last time she would perform this work. On New Year's Day 1953 she was appointed a Commander of the Order of the British Empire

The Most Excellent Order of the British Empire is a British order of chivalry, rewarding contributions to the arts and sciences, work with charitable and welfare organisations,

and public service outside the civil service. It was established o ...

(CBE) in the Queen's New Year Honours List

The New Year Honours is a part of the British honours system, with New Year's Day, 1 January, being marked by naming new members of orders of chivalry and recipients of other official honours. A number of other Commonwealth realms also mark this ...

.

Final performances, illness and death

As 1953 began, Ferrier was busy rehearsing for ''Orpheus'', an English language version of ''Orfeo ed Euridice'' to be staged in four performances at theRoyal Opera House

The Royal Opera House (ROH) is an opera house and major performing arts venue in Covent Garden, central London. The large building is often referred to as simply Covent Garden, after a previous use of the site. It is the home of The Royal Op ...

in February. Barbirolli had instigated this project, with Ferrier's enthusiastic approval, some months previously. Her only other engagement in January was a BBC recital recording, in which she sang works by three living English composers: Howard Ferguson

George Howard Ferguson, PC (June 18, 1870 – February 21, 1946) was the ninth premier of Ontario, from 1923 to 1930. He was a Conservative member of the Legislative Assembly of Ontario from 1905 to 1930 who represented the eastern provinci ...

, William Wordsworth

William Wordsworth (7 April 177023 April 1850) was an English Romantic poet who, with Samuel Taylor Coleridge, helped to launch the Romantic Age in English literature with their joint publication ''Lyrical Ballads'' (1798).

Wordsworth's ' ...

and Edmund Rubbra

Edmund Rubbra (; 23 May 190114 February 1986) was a British composer. He composed both instrumental and vocal works for soloists, chamber groups and full choruses and orchestras. He was greatly esteemed by fellow musicians and was at the peak o ...

. During her regular hospital treatment she discussed with doctors the advisability of an oophorectomy

Oophorectomy (; from Greek , , 'egg-bearing' and , , 'a cutting out of'), historically also called ''ovariotomy'' is the surgical removal of an ovary or ovaries. The surgery is also called ovariectomy, but this term is mostly used in reference to ...

(removal of the ovaries), but on learning that the impact on her cancer would probably be insignificant and that her voice might be badly affected, she chose not to have the operation.

The first ''Orpheus'' performance, on 3 February, was greeted with unanimous critical approval. According to Barbirolli, Ferrier was particularly pleased with one critic's comment that her movements were as graceful as any of those of the dancers on stage. However, she was physically weakened from her prolonged radiation treatment; during the second performance, three days later, her left femur

The femur (; ), or thigh bone, is the proximal bone of the hindlimb in tetrapod vertebrates. The head of the femur articulates with the acetabulum in the pelvic bone forming the hip joint, while the distal part of the femur articulates with ...

partially disintegrated. Quick action by other cast members, who moved to support her, kept the audience in ignorance. Although virtually immobilised, Ferrier sang her remaining arias and took her curtain calls before being transferred to hospital. This proved to be her final public appearance; the two remaining performances, at first rescheduled for April, were eventually cancelled. Still the general public remained unaware of the nature of Ferrier's incapacity; an announcement in ''The Guardian'' stated: "Miss Ferrier is suffering from a strain resulting from arthritis which requires immediate further treatment. It has been caused by the physical stress involved in rehearsal and performance of her role in ''Orpheus''".

Ferrier spent two months in University College Hospital. As a result, she missed her CBE investiture

Investiture (from the Latin preposition ''in'' and verb ''vestire'', "dress" from ''vestis'' "robe") is a formal installation or ceremony that a person undergoes, often related to membership in Christian religious institutes as well as Christian k ...

; the ribbon was brought to her at the hospital by a friend. Meanwhile, her sister found her a ground-floor apartment in St John's Wood

St John's Wood is a district in the City of Westminster, London, lying 2.5 miles (4 km) northwest of Charing Cross. Traditionally the northern part of the ancient parish and Metropolitan Borough of Marylebone, it extends east to west from ...

, since she would no longer be able to negotiate the many stairs at Frognal Mansions. She moved to her new home in early April, but after only seven weeks was forced to return to hospital where, despite two further operations, her condition continued to deteriorate.Leonard, pp. 241–245 Early in June she heard that she had been awarded the Gold Medal of the Royal Philharmonic Society

The Royal Philharmonic Society (RPS) is a British music society, formed in 1813. Its original purpose was to promote performances of instrumental music in London. Many composers and performers have taken part in its concerts. It is now a memb ...

, the first female vocalist to receive this honour since Muriel Foster

Muriel Foster (22 November 187723 December 1937) was an English contralto, excelling in oratorio. '' Grove's Dictionary'' describes her voice as "one of the most beautiful voices of her time".

Muriel Foster was born in Sunderland in 1877. She w ...

in 1914. In a letter to the secretary of the Society she wrote that this "unbelievable, wondrous news has done more than anything to make me feel so much better". This letter, dated 9 June, is probably the last that Ferrier signed herself. As she weakened she saw only her sister and a few very close friends, and, although there were short periods of respite, her decline was unremitting. She died at University College Hospital on 8 October 1953, aged 41; the date for which, while still hopeful of recovery, she had undertaken to sing Frederick Delius

Delius, photographed in 1907

Frederick Theodore Albert Delius ( 29 January 1862 – 10 June 1934), originally Fritz Delius, was an English composer. Born in Bradford in the north of England to a prosperous mercantile family, he resisted atte ...

's ''A Mass of Life

''A Mass of Life'' (German: ''Eine Messe des Lebens'') is a cantata by English composer Frederick Delius, based on the German text of Friedrich Nietzsche's philosophical novel ''Thus Spoke Zarathustra'' (1883-1885). In 1898, Delius had written a m ...

'' at the 1953 Leeds Festival

The Reading and Leeds Festivals are a pair of annual music festivals that take place in Reading and Leeds in England. The events take place simultaneously on the Friday, Saturday and Sunday of the August bank holiday weekend. The Reading Festiv ...

. Ferrier was cremated a few days later, at Golders Green Crematorium

Golders Green Crematorium and Mausoleum was the first crematorium to be opened in London, and one of the oldest crematoria in Britain. The land for the crematorium was purchased in 1900, costing £6,000 (the equivalent of £135,987 in 2021), ...

, after a short private service.Leonard, pp. 246–251 She left an estate worth £15,134, which her biographer Maurice Leonard observes was "not a fortune for a world-famous singer, even by the standards of the day".

Assessment and legacy

The news of Ferrier's death came as a considerable shock to the public. Although some in musical circles knew or suspected the truth, the myth had been preserved that her absence from the concert scene was temporary. The opera critic

The news of Ferrier's death came as a considerable shock to the public. Although some in musical circles knew or suspected the truth, the myth had been preserved that her absence from the concert scene was temporary. The opera critic Rupert Christiansen Rupert Christiansen (born 1954) is an English writer, journalist and critic.

Life and career

Born in London, Christiansen is the grandson of Arthur Christiansen (former editor of the '' Daily Express'') and son of Kay and Michael Christiansen (for ...

, writing as the 50th anniversary of Ferrier's death approached, maintained that "no singer in this country has ever been more deeply loved, as much for the person she was as for the voice she uttered". Her death, he continued, "quite literally shattered the euphoria of the Coronation" (which had taken place on 2 June 1953). Ian Jack

Ian Grant Jack (7 February 1945 – 28 October 2022) was a British reporter, writer and editor. He edited the ''Independent on Sunday'', the literary magazine ''Granta'' and wrote regularly for ''The Guardian''.

Early life

Jack was born in Fa ...

, editor of ''Granta

''Granta'' is a literary magazine and publisher in the United Kingdom whose mission centres on its "belief in the power and urgency of the story, both in fiction and non-fiction, and the story’s supreme ability to describe, illuminate and ma ...

'', believed that she "may well have been the most celebrated woman in Britain after the Queen." Among the many tributes from her colleagues, that of Bruno Walter has been highlighted by biographers: "The greatest thing in music in my life has been to have known Kathleen Ferrier and Gustav Mahler—in that order." Very few singers, Lord Harewood writes, "have earned so powerful a valedictory from so senior a colleague." At a memorial service at Southwark Cathedral

Southwark Cathedral ( ) or The Cathedral and Collegiate Church of St Saviour and St Mary Overie, Southwark, London, lies on the south bank of the River Thames close to London Bridge. It is the mother church of the Anglican Diocese of Southwark. ...

on 14 November 1953 the Bishop of Croydon

The Bishop of Croydon is an episcopal title used by an area bishop of the Church of England Diocese of Southwark, in the Province of Canterbury, England. The Croydon Archdeaconry was transferred from Canterbury Diocese to Southwark in 1984.

Th ...

, in his eulogy, said of Ferrier's voice: "She seemed to bring into this world a radiance from another world."

From time to time commentators have speculated on the directions Ferrier's career might have taken had she lived. In 1951, while recovering from her mastectomy, she received an offer to sing the part of Brangäne in Wagner

Wilhelm Richard Wagner ( ; ; 22 May 181313 February 1883) was a German composer, theatre director, polemicist, and conductor who is chiefly known for his operas (or, as some of his mature works were later known, "music dramas"). Unlike most op ...

's opera ''Tristan und Isolde

''Tristan und Isolde'' (''Tristan and Isolde''), WWV 90, is an opera in three acts by Richard Wagner to a German libretto by the composer, based largely on the 12th-century romance Tristan and Iseult by Gottfried von Strassburg. It was compose ...

'' at the 1952 Bayreuth Festival

The Bayreuth Festival (german: link=no, Bayreuther Festspiele) is a music festival held annually in Bayreuth, Germany, at which performances of operas by the 19th-century German composer Richard Wagner are presented. Wagner himself conceived ...

. According to Christiansen she would have been "glorious" in the role, and was being equally sought by the Bayreuth management to sing Erda in the ''Ring cycle

(''The Ring of the Nibelung''), WWV 86, is a cycle of four German-language epic music dramas composed by Richard Wagner. The works are based loosely on characters from Germanic heroic legend, namely Norse legendary sagas and the ''Nibelung ...

''. Christiansen further suggests that, given the changes of style over the past 50 years, Ferrier might have been less successful in the 21st century world: "We dislike low-lying voices, for one thing—contraltos now sound freakish and headmistressy, and even the majority of mezzo-sopranos should more accurately be categorised as almost-sopranos". However, she was "a singer of, and for, her time—a time of grief and weariness, national self-respect and a belief in human nobility". In this context "her artistry stands upright, austere, unfussy, fundamental and sincere".

Shortly after Ferrier's death an appeal was launched by Barbirolli, Walter, Myra Hess and others, to establish a cancer research fund in Ferrier's name. Donations were received from all over the world. To publicise the fund a special concert was given at the Royal Festival Hall on 7 May 1954, at which Barbirolli and Walter shared the conducting duties without payment. Among the items was a rendition of Henry Purcell, Purcell's ''Dido's Lament, When I am laid in earth'', which Ferrier had often sung; on this occasion the vocal part was played by a solo cor anglais. The Kathleen Ferrier Cancer Research Fund helped establish the Kathleen Ferrier Chair of Clinical Oncology at University College Hospital, in 1984. , it was continuing to fund oncology research.

As the result of a separate appeal, augmented by the sales proceeds of a memoir edited by Neville Cardus, the Kathleen Ferrier Award, Kathleen Ferrier Memorial Scholarship Fund was created to encourage young British and Commonwealth of Nations, Commonwealth singers of either sex. The Fund, which has operated from 1956 under the auspices of the Royal Philharmonic Society, initially provided an annual award covering the cost of a year's study to a single prizewinner. With the advent of additional sponsors, the number and scope of awards has expanded considerably since that time; the list of winners of Ferrier Awards includes many singers of international repute, among them Felicity Palmer, Yvonne Kenny, Lesley Garrett and Bryn Terfel. The Kathleen Ferrier Society, founded in 1993 to promote interest in all aspects of the singer's life and work, has since 1996 awarded annual bursary, bursaries to students at Britain's major music colleges. In 2012, the Society organised a series of events to commemorate the centenary of Ferrier's birth and in February 2012 Ferrier was one of ten prominent Britons honoured by the Royal Mail in the "Britons of Distinction" stamps set. Another was Frederick Delius.

A biographic documentary film, ''Kathleen Ferrier'', also known as ' was directed by Diane Perelsztejn and produced by Arte, ARTE France in 2012. It featured interviews with her near relatives, friends and colleagues to produce a fresh view of her life and contributions to the arts. Kathleen Ferrier Crescent, in Basildon, Essex, is named in her honour.

Recordings

Ferrier's discography consists of studio recordings originally made on the Columbia and Decca labels, and recordings taken from live performances which were later issued as discs. In the years since her death, many of her recordings have received multiple reissues on modern media; between 1992 and 1996 Decca issued the Kathleen Ferrier Edition, incorporating much of Ferrier's recorded repertoire, on 10 compact discs. The discographer Paul Campion has drawn attention to numerous works which she performed but did not record, or for which no complete recording has yet surfaced. For example, only one aria from Elgar's ''Dream of Gerontius'', and none of her renderings of 20th century songs by Gustav Holst, Holst, Arnold Bax, Bax, Delius and others were recorded. Only a small part of her ''St John Passion'' was captured on disc. The recording of the a cappella, unaccompanied Northumbrian folk song "Blow the Wind Southerly", initially made by Decca in 1949, has been reissued many times and frequently played on radio in shows such as ''Desert Island Discs'', ''Housewives' Choice'' and ''Your Hundred Best Tunes''.Campion, pp. 43–44 Another signature aria, first recorded in 1944 and on numerous subsequent occasions, is "What is Life?" (''Che farò'') from ''Orfeo ed Euridice''. These records sold in large numbers rivalling those of other stars of the time, such as Frank Sinatra and Vera Lynn. In the 21st century Ferrier's recordings still sell hundreds of thousands of copies each year.Notes and references

Notes ReferencesSources

* * * * * * * * * * * *External links

The Kathleen Ferrier Society (KFS)

Flat at Frognal Mansions, Hampstead, with blue plaque