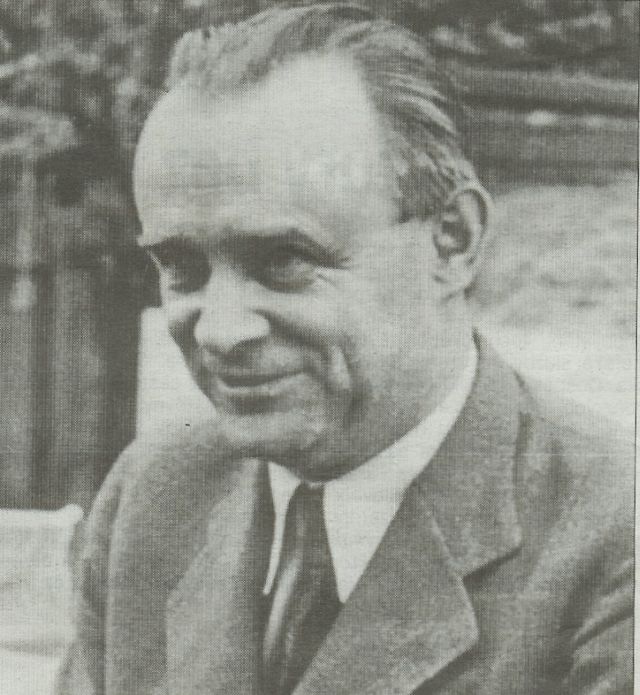

Karel Janoušek on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Karel Janoušek, (30 October 1893 – 27 October 1971) was a senior

In May 1945 the European theatre of World War II, Second World War in Europe ended, and in August the RAF's Czechoslovak squadrons relocated to Václav Havel Airport Prague, Ruzyně Airport, Prague. On 3 August they held a farewell parade at RAF Manston in Kent, where Air Marshal John Slessor inspected them. The next day Janoušek gave a farewell broadcast on the BBC Home Service. He told listeners:

In May 1945 the European theatre of World War II, Second World War in Europe ended, and in August the RAF's Czechoslovak squadrons relocated to Václav Havel Airport Prague, Ruzyně Airport, Prague. On 3 August they held a farewell parade at RAF Manston in Kent, where Air Marshal John Slessor inspected them. The next day Janoušek gave a farewell broadcast on the BBC Home Service. He told listeners:

In February 1948 the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia 1948 Czechoslovak coup d'état, seized power. Three days later Boček ordered Janoušek, Brig Gen Alois Liška and military intelligence chief Gen František Moravec to take leave "for health reasons" pending a final decision about their future. In March Gen Šimon Drgáč personally told Janoušek there was no place for him under the Communist régime. Janoušek applied for a job at the International Civil Aviation Organization in Montreal, for which he had helped to lay the foundations at the 1944 Chicago conference. Dr Josef Dubský at the ICAO offered him a job, but Bedřich Reicin at the OBZ refused to let Janoušek leave Czechoslovakia.

In February 1948 the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia 1948 Czechoslovak coup d'état, seized power. Three days later Boček ordered Janoušek, Brig Gen Alois Liška and military intelligence chief Gen František Moravec to take leave "for health reasons" pending a final decision about their future. In March Gen Šimon Drgáč personally told Janoušek there was no place for him under the Communist régime. Janoušek applied for a job at the International Civil Aviation Organization in Montreal, for which he had helped to lay the foundations at the 1944 Chicago conference. Dr Josef Dubský at the ICAO offered him a job, but Bedřich Reicin at the OBZ refused to let Janoušek leave Czechoslovakia.

In June 1952 Janoušek was moved to Leopoldov Prison, a converted 17th-century fortress in Slovakia. In 1955 President Antonín Zápotocký granted a partial amnesty and Janoušek's life sentence was reduced to 25 years. In November 1956 he was moved again, to a prison at Ruzyně near Prague. Before the end of the year Janoušek's 25-year sentence was reduced to four years and his earlier 19-year sentence was reduced to 16 years.

In June 1952 Janoušek was moved to Leopoldov Prison, a converted 17th-century fortress in Slovakia. In 1955 President Antonín Zápotocký granted a partial amnesty and Janoušek's life sentence was reduced to 25 years. In November 1956 he was moved again, to a prison at Ruzyně near Prague. Before the end of the year Janoušek's 25-year sentence was reduced to four years and his earlier 19-year sentence was reduced to 16 years.

Janoušek's Czechoslovak decorations included the Czechoslovak War Cross 1918, Czechoslovak War Cross 1939–1945, ''Československá medaile Za chrabrost před nepřítelem'' ("Bravery in Face of the Enemy") and ''Československá medaile za zásluhy, 1. stupně'' ("Medal of Merit, First Class"). In 2016 on Czech Independence Day, 28 October, the Czech Republic Posthumous award, Posthumously awarded him the Order of the White Lion First Class. He has also been posthumously awarded the Milan Rastislav Stefanik Order Second Class.

In 1945 France made Janoušek a ''Legion of Honour#Membership, Commandeur de la Légion d'honneur''. He also held the Croix de guerre 1914–1918 (France), ''Croix de Guerre'' 1914–18 and Croix de guerre 1939–1945 (France), ''Croix de Guerre'' 1939–45. In 1945 the USA made him a Legion of Merit#Criteria, Commander of the Legion of Merit. Poland made him a Order of Polonia Restituta#Classed, Commander of the Order of Polonia Restituta. He was also awarded White Russian, Yugoslav, Romanian and Norway, Norwegian decorations.

Janoušek's Czechoslovak decorations included the Czechoslovak War Cross 1918, Czechoslovak War Cross 1939–1945, ''Československá medaile Za chrabrost před nepřítelem'' ("Bravery in Face of the Enemy") and ''Československá medaile za zásluhy, 1. stupně'' ("Medal of Merit, First Class"). In 2016 on Czech Independence Day, 28 October, the Czech Republic Posthumous award, Posthumously awarded him the Order of the White Lion First Class. He has also been posthumously awarded the Milan Rastislav Stefanik Order Second Class.

In 1945 France made Janoušek a ''Legion of Honour#Membership, Commandeur de la Légion d'honneur''. He also held the Croix de guerre 1914–1918 (France), ''Croix de Guerre'' 1914–18 and Croix de guerre 1939–1945 (France), ''Croix de Guerre'' 1939–45. In 1945 the USA made him a Legion of Merit#Criteria, Commander of the Legion of Merit. Poland made him a Order of Polonia Restituta#Classed, Commander of the Order of Polonia Restituta. He was also awarded White Russian, Yugoslav, Romanian and Norway, Norwegian decorations.

Czechoslovak Air Force

The Czechoslovak Air Force (''Československé letectvo'') or the Czechoslovak Army Air Force (''Československé vojenské letectvo'') was the air force branch of the Czechoslovak Army formed in October 1918. The armed forces of Czechoslovakia c ...

officer. He began his career as a soldier, serving in the Austrian Imperial-Royal Landwehr

The Imperial-Royal Landwehr ( or ''k.k. Landwehr''), also called the Austrian Landwehr, was the territorial army of the Cisleithanian or Austrian half of the Austro-Hungarian Empire from 1869 to 1918. Its counterpart was the Royal Hungarian Land ...

1915–16, Czechoslovak Legion

The Czechoslovak Legion ( Czech: ''Československé legie''; Slovak: ''Československé légie'') were volunteer armed forces consisting predominantly of Czechs and Slovaks fighting on the side of the Entente powers during World War I and the ...

1916–20 and Czechoslovak Army

The Czechoslovak Army (Czech and Slovak: ''Československá armáda'') was the name of the armed forces of Czechoslovakia. It was established in 1918 following Czechoslovakia's declaration of independence from Austria-Hungary.

History

In t ...

1920–24.

In 1924 Janoušek transferred to the Czechoslovak Air Force

The Czechoslovak Air Force (''Československé letectvo'') or the Czechoslovak Army Air Force (''Československé vojenské letectvo'') was the air force branch of the Czechoslovak Army formed in October 1918. The armed forces of Czechoslovakia c ...

and in 1926 he qualified as an aircraft pilot

An aircraft pilot or aviator is a person who controls the flight of an aircraft by operating its directional flight controls. Some other aircrew members, such as navigators or flight engineers, are also considered aviators because they a ...

. In 1930 he co-wrote a textbook on aerial warfare

Aerial warfare is the use of military aircraft and other flying machines in warfare. Aerial warfare includes bombers attacking tactical bombing, enemy installations or a concentration of enemy troops or Strategic bombing, strategic targets; fi ...

tactics

Tactic(s) or Tactical may refer to:

* Tactic (method), a conceptual action implemented as one or more specific tasks

** Military tactics, the disposition and maneuver of units on a particular sea or battlefield

** Chess tactics

In chess, a tac ...

. In the 1930s he was a staff officer

A military staff or general staff (also referred to as army staff, navy staff, or air staff within the individual services) is a group of officers, enlisted, and civilian staff who serve the commander of a division or other large milita ...

. From 1936 he studied meteorology and geophysics at the Charles University

Charles University (CUNI; , UK; ; ), or historically as the University of Prague (), is the largest university in the Czech Republic. It is one of the List of oldest universities in continuous operation, oldest universities in the world in conti ...

and in 1939 he was awarded a doctorate in natural science

Natural science or empirical science is one of the branches of science concerned with the description, understanding and prediction of natural phenomena, based on empirical evidence from observation and experimentation. Mechanisms such as peer ...

s (RNDr).

In the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

Janoušek escaped first to France and then the United Kingdom. In the UK he commanded the RAF's Czechoslovak squadrons, was knighted by HM King George VI

George VI (Albert Frederick Arthur George; 14 December 1895 – 6 February 1952) was King of the United Kingdom and the Dominions of the British Commonwealth from 11 December 1936 until Death and state funeral of George VI, his death in 1952 ...

and ultimately promoted to Air Marshal. In occupied Czechoslovakia

' ( Norwegian: ') is a Norwegian political thriller TV series that premiered on TV2 on 5 October 2015. Based on an original idea by Jo Nesbø, the series is co-created with Karianne Lund and Erik Skjoldbjærg. Season 2 premiered on 10 October ...

the Nazis retaliated against Janoušek's Free Czechoslovak service by jailing his wife and much of their family.

In 1945 Janoušek returned to Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia ( ; Czech language, Czech and , ''Česko-Slovensko'') was a landlocked country in Central Europe, created in 1918, when it declared its independence from Austria-Hungary. In 1938, after the Munich Agreement, the Sudetenland beca ...

, where he found his wife and several of their relatives had died in imprisonment. He was sidelined by the increasingly pro-Communist

Communism () is a sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology within the socialist movement, whose goal is the creation of a communist society, a socioeconomic order centered on common ownership of the means of production, di ...

commanders of the Czechoslovak Air Force. After the 1948 Czechoslovak coup d'état

In late February 1948, the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia (KSČ), with Soviet backing, assumed undisputed control over the government of Czechoslovakia through a coup d'état. It marked the beginning of four decades of the party's rule in t ...

Janoušek was court-martial

A court-martial (plural ''courts-martial'' or ''courts martial'', as "martial" is a postpositive adjective) is a military court or a trial conducted in such a court. A court-martial is empowered to determine the guilt of members of the arme ...

led, sentenced to 18 years in prison and stripped of his rank, doctorate and awards. In 1949 his sentence was extended to 19 years. In 1950 it was extended to life imprisonment

Life imprisonment is any sentence (law), sentence of imprisonment under which the convicted individual is to remain incarcerated for the rest of their natural life (or until pardoned or commuted to a fixed term). Crimes that result in life impr ...

for a separate offence, but in 1955 this sentence was shortened to 25 years.

In 1956 Janoušek' sentences were reduced and in 1960 he was released in a Presidential amnesty. A military tribunal cancelled his convictions in the Prague Spring

The Prague Spring (; ) was a period of liberalization, political liberalization and mass protest in

the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic. It began on 5 January 1968, when reformist Alexander Dubček was elected Secretary (title), First Secre ...

in 1968. Janoušek died in Prague in 1971. He was not fully rehabilitated until after the 1989 Velvet Revolution

The Velvet Revolution () or Gentle Revolution () was a non-violent transition of power in what was then Czechoslovakia, occurring from 17 November to 28 November 1989. Popular demonstrations against the one-party government of the Communist Pa ...

ended the Communist dictatorship.

Early life

Janoušek was born inPřerov

Přerov (; ) is a city in the Olomouc Region of the Czech Republic. It has about 41,000 inhabitants. It lies on the Bečva River. In the past it was a major crossroad in the heart of Moravia in the Czech Republic. The historic city centre is we ...

, Moravia

Moravia ( ; ) is a historical region in the eastern Czech Republic, roughly encompassing its territory within the Danube River's drainage basin. It is one of three historical Czech lands, with Bohemia and Czech Silesia.

The medieval and early ...

, the second child of a clerk on the Imperial Royal Austrian State Railways

The Imperial-Royal State Railways () abbr. ''kkStB'') or Imperial-Royal Austrian State Railways (''k.k. österreichische Staatsbahnen'',The name incorporating "Austrian" appears, for example, in the 1907 official state handbook (''Staatshandbuch'' ...

. His father, also called Karel Janoušek, was a founding member of the Czech Social Democratic Party

Social Democracy (, SOCDEM), known as the Czech Social Democratic Party (, ČSSD) until 10 June 2023, is a social democratic political party in the Czech Republic. Sitting on the centre-left of the political spectrum and holding pro-European ...

. Janoušek's mother, Adelheid, died when Janoušek was two years old. His father remarried and had another nine children by his second wife, Božena.

Janoušek completed secondary school in 1912 and then went to a German business school. He spent the first three years of his working life as a clerk in a local business that belonged to a distant relative.

In June 1915 Janoušek was conscripted

Conscription, also known as the draft in the United States and Israel, is the practice in which the compulsory enlistment in a national service, mainly a military service, is enforced by law. Conscription dates back to antiquity and it contin ...

into the Austrian Imperial-Royal Landwehr

The Imperial-Royal Landwehr ( or ''k.k. Landwehr''), also called the Austrian Landwehr, was the territorial army of the Cisleithanian or Austrian half of the Austro-Hungarian Empire from 1869 to 1918. Its counterpart was the Royal Hungarian Land ...

, trained at Opava

Opava (; , ) is a city in the Moravian-Silesian Region of the Czech Republic. It has about 55,000 inhabitants. It lies on the Opava (river), Opava River. Opava is one of the historical centres of Silesia and was a historical capital of Czech Sile ...

in Czech Silesia

Czech Silesia (; ) is the part of the historical region of Silesia now in the Czech Republic. While it currently has no formal boundaries, in a narrow geographic sense, it encompasses most or all of the territory of the Czech Republic within the ...

and was promoted to corporal. He served in the 57th Infantry Regiment and fought in the Sixth Battle of the Isonzo

The Sixth Battle of the Isonzo, better known as the Battle of Gorizia, was the most successful Italian offensive along the Soča () River during World War I.

Background

Franz Conrad von Hötzendorf had reduced the Austro-Hungarian forces alo ...

on the Italian Front.

Janoušek was then transferred to the Eastern Front to resist the Russian Brusilov Offensive. Russian forces captured him on 2 July 1916 and detained him in a prisoner-of-war camp

A prisoner-of-war camp (often abbreviated as POW camp) is a site for the containment of enemy fighters captured as Prisoner of war, prisoners of war by a belligerent power in time of war.

There are significant differences among POW camps, inte ...

near Kiev

Kyiv, also Kiev, is the capital and most populous List of cities in Ukraine, city of Ukraine. Located in the north-central part of the country, it straddles both sides of the Dnieper, Dnieper River. As of 1 January 2022, its population was 2, ...

, Ukraine

Ukraine is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the List of European countries by area, second-largest country in Europe after Russia, which Russia–Ukraine border, borders it to the east and northeast. Ukraine also borders Belarus to the nor ...

. However, on 1 August 1916 Janoušek was released to join the II Volunteer Division of the Serbian Army

The Serbian Army () is the land-based and the largest component of the Serbian Armed Forces. Its organization, composition, weapons and equipment are adapted to the assigned missions and tasks of the Serbian Armed Forces, primarily for operatio ...

in Odessa

ODESSA is an American codename (from the German language, German: ''Organisation der ehemaligen SS-Angehörigen'', meaning: Organization of Former SS Members) coined in 1946 to cover Ratlines (World War II aftermath), Nazi underground escape-pl ...

, which recognised his Austrian rank of corporal.

Czechoslovak Legion 1916–20

On 14 October 1916 Janoušek transferred to theCzechoslovak Legion

The Czechoslovak Legion ( Czech: ''Československé legie''; Slovak: ''Československé légie'') were volunteer armed forces consisting predominantly of Czechs and Slovaks fighting on the side of the Entente powers during World War I and the ...

as a private and joined its 1st Rifle Regiment at Boryspil

Boryspil (, ) is a city and the administrative center of Boryspil Raion in Kyiv Oblast (region) in northern and central Ukraine. It hosts the administration of Boryspil urban hromada, one of the hromadas of Ukraine. The population was estimate ...

. In 1917 after the February Revolution

The February Revolution (), known in Soviet historiography as the February Bourgeois Democratic Revolution and sometimes as the March Revolution or February Coup was the first of Russian Revolution, two revolutions which took place in Russia ...

the Czechoslovak Legion became part of the Russian 7th Army. Janoušek fought at the Battle of Zborov on 1–2 July 1917. He was wounded on 18 July, in hospital until August and then promoted to warrant officer

Warrant officer (WO) is a Military rank, rank or category of ranks in the armed forces of many countries. Depending on the country, service, or historical context, warrant officers are sometimes classified as the most junior of the commissioned ...

.

After the October Revolution

The October Revolution, also known as the Great October Socialist Revolution (in Historiography in the Soviet Union, Soviet historiography), October coup, Bolshevik coup, or Bolshevik revolution, was the second of Russian Revolution, two r ...

the Czechoslovak Legion suffered internal strife between pro- and anti-Bolshevik

The Bolsheviks, led by Vladimir Lenin, were a radical Faction (political), faction of the Marxist Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP) which split with the Mensheviks at the 2nd Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party, ...

factions. Janoušek was in the anti-Bolshevik faction, which ultimately won. The Legion disobeyed Edvard Beneš

Edvard Beneš (; 28 May 1884 – 3 September 1948) was a Czech politician and statesman who served as the president of Czechoslovakia from 1935 to 1938, and again from 1939 to 1948. During the first six years of his second stint, he led the Czec ...

' order to surrender "rebels" to the Bolsheviks, and in October 1918 Janoušek was promoted to interim commander of the 7th Company

A company, abbreviated as co., is a Legal personality, legal entity representing an association of legal people, whether Natural person, natural, Juridical person, juridical or a mixture of both, with a specific objective. Company members ...

of the II Battalion

A battalion is a military unit, typically consisting of up to one thousand soldiers. A battalion is commanded by a lieutenant colonel and subdivided into several Company (military unit), companies, each typically commanded by a Major (rank), ...

of the 1st Regiment

A regiment is a military unit. Its role and size varies markedly, depending on the country, military service, service, or administrative corps, specialisation.

In Middle Ages, Medieval Europe, the term "regiment" denoted any large body of l ...

.

The Legion joined one of the White movement, White Armies in the Russian Civil War. Janoušek fought in battles against the Red Army at Bugulma, Dimitrovgrad, Russia, Melekess, Braudina, Ulyanovsk, Simbirsk and Kazan. On 7 August 1918 he took command of the 3rd Company of the 1st Regiment. In September the Red Army forced the Legion to retreat from Kazan. In October Czechoslovak declaration of independence, Czechoslovakia declared independence from Austria-Hungary, and in November the First World War ended with the armistices of Armistice of Villa Giusti, Villa Giusti and Armistice of 11 November 1918, Compiègne. But the Czechoslovak Legion was trapped in Russia, with the Red Army blocking its escape to the west.

The Legion therefore fought its way east across Siberia to Vladivostok to be evacuated by sea. At Tayshet in May 1919 it defended the Trans-Siberian Railway from a Red Army attack. Janoušek was wounded again and treated in hospital in Irkutsk until the end of June. On 25 May French Third Republic, France, one of the Allied intervention in the Russian Civil War, interventionist powers, awarded him the ''Croix de Guerre'' with palm leaf. Janoušek's company set off for Vladivostok on 10 October 1919. On 6 December the unit sailed from Vladivostok aboard a Japanese steamship, the ''Yonan Maru''. Janoušek and his unit finally reached Prague on 2 February 1920.

Czechoslovakia 1920–39

Czechoslovak Army 1920–24

The Czechoslovak Legion formed the basis of the newCzechoslovak Army

The Czechoslovak Army (Czech and Slovak: ''Československá armáda'') was the name of the armed forces of Czechoslovakia. It was established in 1918 following Czechoslovakia's declaration of independence from Austria-Hungary.

History

In t ...

. In May 1920 Janoušek took command of the 2nd Infantry Regiment at Dobšiná in Slovakia and on 1 July he was made Second in Command of the XXII Brigade at Košice. On 21 February 1921 he was promoted to staff captain and given command of the 12th Artillery Regiment at Uzhhorod in Carpathian Ruthenia, but in October he was transferred to a desk job in Košice.

In September 1923 Janoušek graduated from War College. He was briefly stationed at the Provincial Headquarters in Prague, but then in February 1924 started training at Cheb in Bohemia to become a pilot.

Czechoslovak Air Force 1924–39

In January 1925 Janoušek was appointed Commander of the Xth Air Reconnaissance Course. On 19 November 1925 he married Anna Steinbachová, ''née'' Hoffmannová. On 1 January 1926 he qualified as a pilot. He was not an outstanding pilot, but he was good at reconnaissance, air navigation and meteorology. On 2 December 1926 he was promoted to Major (rank), major of the Staff (military), General Staff. In September 1927 he went on a one-month attachment to the French French Air Force, Armée de l'Air. On 28 February 1928 he was promoted to lieutenant colonel. By now he was Second in Command of the Military Flying School. He co-authored a book onaerial warfare

Aerial warfare is the use of military aircraft and other flying machines in warfare. Aerial warfare includes bombers attacking tactical bombing, enemy installations or a concentration of enemy troops or Strategic bombing, strategic targets; fi ...

tactics

Tactic(s) or Tactical may refer to:

* Tactic (method), a conceptual action implemented as one or more specific tasks

** Military tactics, the disposition and maneuver of units on a particular sea or battlefield

** Chess tactics

In chess, a tac ...

, inspired by the ideas of the Italian Military theory, military theorist Giulio Douhet, which was published in May 1930.

Janoušek was then posted to Slovakia and, on 31 December 1930, promoted to command the 6th Flying Regiment. In 1930–32 his duties also included training officers to be higher commanders. On 31 July 1933 he was promoted to full colonel. By 1936 he was a brigadier general and a Provincial Commander of the Air Force. Bad weather was a major limitation on aviation, and caused about half of all air accidents. Therefore, in 1936 Janoušek started studying meteorology and geophysics at the Charles University in Prague.

During the Munich Agreement#Sudeten crisis, Sudeten Crisis Czechoslovakia ordered a partial mobilization on 21 May and complete mobilization on 23 September. Janoušek commanded the Air Force of General Sergei Wojciechowski's 1st Army, which was to protect the frontier with Nazi Germany from České Budějovice in the southwest to Králíky in the north. But on 29 September France and the United Kingdom signed the Munich Agreement with Germany, forcing Czechoslovakia to cede the Sudetenland without a fight.

On 15 March 1939 Germany occupied Czechoslovakia

' ( Norwegian: ') is a Norwegian political thriller TV series that premiered on TV2 on 5 October 2015. Based on an original idea by Jo Nesbø, the series is co-created with Karianne Lund and Erik Skjoldbjærg. Season 2 premiered on 10 October ...

and created the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia, which was required to dissolve its army and air force. Nevertheless, Janoušek completed his course at Charles University and graduated with a doctorate in natural science

Natural science or empirical science is one of the branches of science concerned with the description, understanding and prediction of natural phenomena, based on empirical evidence from observation and experimentation. Mechanisms such as peer ...

s (RNDr) on 23 June.

Hundreds of Czechoslovak army and air force personnel responded to the German occupation by escaping to Second Polish Republic, Poland or France. The secret Obrana národa Resistance in German-occupied Czechoslovakia, Czechoslovak resistance organisation helped Janoušek to cross into Slovak Republic (1939–1945), Slovakia on 15 November 1939. From there he travelled ''via'' Hungary in World War II, Hungary, Kingdom of Yugoslavia, Yugoslavia, Kingdom of Greece, Greece and Beirut in French Mandate for Syria and the Lebanon, French-ruled Lebanon to reach France.

Second World War

France 1939–40

Janoušek reported for duty in Paris on 1 December 1939. He was assigned to the Czechoslovak Military Administration (CsVS) as Head of the 3rd (Air) Department, ''de facto'' commanding the free Czechoslovak Air Force being formed in France, for which there were agreements between the French and Free Czechoslovak governments. But turning the force into a reality was hampered by inaction of the French Ministry of Aviation, lack of equipment, and Czechoslovak air force personnel being scattered at more than 20 locations in France and the French colonial empire, French Empire. On 15 March 1940 Janoušek was replaced by his senior and rival, Brig Gen Alois Vicherek. Janoušek was then to command a Czechoslovak Air Force training centre, which was to be built at Cognac, France, Cognac in western France. It never materialised. On 10 May Germany Battle of the Netherlands, invaded the Netherlands, Battle of Belgium, Belgium and Battle of France, France. As French armed forces were collapsing, on 18 June Janoušek and a large group of Czechoslovak airmen left Bordeaux aboard a small Dutch ship, the ''Karanan'', which reached Falmouth, Cornwall, Falmouth in England on 21 June. The next day Armistice of 22 June 1940, France capitulated to Germany.United Kingdom 1940–45

On 21 June, the day before France capitulated, the former Czechoslovak ambassador to the UK Jan Masaryk was reported as stating that Czechoslovakia "now has 1,500 young, trained pilots in England ready for service with the Allied air forces". However, Brig Gen Vicherek was stuck in France until 27 June and did not reach Britain until 7 July. Hence for a fortnight Janoušek was the most senior Czechoslovak Air force officer in the United Kingdom. There was not yet a military agreement between the Czechoslovak government-in-exile and the UK, but Janoušek secured the help of the UK's former air attaché to Prague, Wing commander (rank), Wg Cdr Frank Beaumont. It was agreed that all Czechoslovak airmen could enlist in the Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve, RAF Volunteer Reserve and that air force units of Czechoslovak personnel would be formed under RAF command. An Inspectorate of Czechoslovak Air Force was formed on 12 July 1940. The UK War Department (United Kingdom), War Department gave Janoušek the rank of Air commodore, Air Commodore, effectively giving him oversight of all Czechoslovak units of the RAF. However, the Defence Ministry of the Czechoslovak government-in-exile did not confirm Janoušek's appointment until 15 October 1940, followed by a Presidential Decree to the same effect on 18 June 1941. Both President Beneš and his Defence Minister, Brig Gen Sergej Ingr, criticised Janoušek for securing an agreement that excluded the government-in-exile from any control over Czechoslovak units and personnel in the RAF. It also excluded Brig Gen Vicherek from the Command hierarchy#Command hierarchy, chain of command. But it also ensured that the RAF enlisted, trained and equipped 88 Czechoslovak fighter pilots in time for them to fight in the Battle of Britain, including No. 310 Squadron RAF which was the RAF's first squadron formed almost entirely of Czechoslovak personnel. As Inspector of the Czechoslovak Air Force, Janoušek too was outside the RAF's immediate chain of command. His job was to inspect the RAF's Czechoslovak squadrons, organise training, propose which Czechoslovak officers should be promoted to command those squadrons, and have meetings with the President Beneš and Defence Minister Ingr. In the course of the war the Air Force Inspectorate expanded to include other functions including medical, transport and Military chaplain, pastoral services. For a time Janoušek's chief of staff was Wg Cdr Josef Schejbal, who in 1941 commanded No. 311 Squadron RAF, the RAF's only Czechoslovak heavy bomber squadron. By May 1941 the RAF had up to 1,600 Czechoslovak personnel. Nos. 310, 311, No. 312 (Czechoslovak) Squadron RAF, 312 and No. 313 Squadron RAF, 313 Squadrons were almost entirely Czechoslovak, as was one flight of No. 68 Squadron RAF, 68 Squadron. There were also numerous Czechoslovak personnel serving in other RAF units. On 31 December 1940 the New Year Honours list announced that Janoušek was to be made a Commander (order), Knight Commander of the Order of the Bath (KCB). HM KingGeorge VI

George VI (Albert Frederick Arthur George; 14 December 1895 – 6 February 1952) was King of the United Kingdom and the Dominions of the British Commonwealth from 11 December 1936 until Death and state funeral of George VI, his death in 1952 ...

knighted him at Buckingham Palace on 20 May 1941. The BBC broadcaster John Snagge interviewed Janoušek for ''The World Goes By'' programme, which was broadcast on the BBC Home Service on 8 July 1941 and the BBC Forces Programme two days later. Janoušek told BBC listeners:

This anniversary gives me a welcome opportunity to say thank you to Britain and the British people...By July 1941 Janoušek was an Air vice-marshal, Air Vice-Marshal. His duties as Inspector took him everywhere that Czechoslovak RAF personnel served or trained, including Canada, the US and The Bahamas. He was a delegate to the December 1944 Chicago Convention on International Civil Aviation that led to the creation of the International Civil Aviation Organization. On 17 May 1945 Janoušek was promoted to Air Marshal. Janoušek wrote a booklet in English, ''The Czechoslovak Air Force''. It is undated but seems to have been published before the end of 1942. In it he summarises the history of the force from the foundation of Czechoslovakia in 1918 to the escape of Czechoslovak airmen from 1938 onward, the formation of free Czechoslovak air units in France in 1939 and Britain in 1940.

The kindness of your RAF officers and men, and indeed of everybody here, has strengthened our souls to carry on. We have been here one short year. The qualities which make life worth living – liberty, decency, kindness and common sense – they are so evident here and more than ever we realise their value. May I thank you on behalf of our Air Force for the privilege of sharing these things with you. May this next year bring us nearer to victory over the enemy – the enemy not only of (the) British or Czechoslovaks or of any other people, but the enemy of all good.

In May 1945 the European theatre of World War II, Second World War in Europe ended, and in August the RAF's Czechoslovak squadrons relocated to Václav Havel Airport Prague, Ruzyně Airport, Prague. On 3 August they held a farewell parade at RAF Manston in Kent, where Air Marshal John Slessor inspected them. The next day Janoušek gave a farewell broadcast on the BBC Home Service. He told listeners:

In May 1945 the European theatre of World War II, Second World War in Europe ended, and in August the RAF's Czechoslovak squadrons relocated to Václav Havel Airport Prague, Ruzyně Airport, Prague. On 3 August they held a farewell parade at RAF Manston in Kent, where Air Marshal John Slessor inspected them. The next day Janoušek gave a farewell broadcast on the BBC Home Service. He told listeners:

Now that the time has come for us to leave this charming and hospitable land, where we have shared with you the joys and sorrows during the past five years of our common struggle; I would like to express to the British people on behalf of myself and of all Czechoslovak Air Force officers and men, our deepest gratitude for all the kindness they have at all times so readily shown us and for making us feel so much at home...

...we are departing with mixed feelings, for there are very few of us in the Czechoslovak Air Force whose families escaped persecution and often death at the hands of the Germans, a price our dear ones had to pay because their sons had taken up arms against the enemies of human freedom... In fact there will be many of us who will have no home to go to and no parents or relatives left alive...

Although we are leaving you we all hope most sincerely that the bonds of friendship forged between our two nations as a result of our happen association with the Royal Air Force, which will always be one of our most treasured memories, will not only remain a solid link unifying our two peoples but will strengthen even further in the days of peace.

Czechoslovakia 1945–71

Janoušek himself returned to Czechoslovakia on 13 August 1945. In six years of occupation the Nazis had jailed most of his family. His wife Anna and one of his sisters had been murdered in Auschwitz concentration camp, Auschwitz. One of his brothers had been murdered in Buchenwald concentration camp, Buchenwald. Two of his brothers-in-law had also died in jail: one in Litoměřice in Bohemia and the other in Pankrác Prison in Prague. General Vicherek had been sent to the Soviet Union on 1 May and made Commander of the Czechoslovak Air Force on 29 May. On 19 October 1945 Janoušek's post of Inspector of the Air Force ceased to exist. The next day he accepted the post of Deputy Chief of the General Headquarters for Special Tasks. He followed his late father into the Czechoslovak Social Democratic Party. In January 1946 the Chief of the Staff of the Czechoslovak Armed Forces, General Bohumil Boček, appraised Janoušek as "lazy, insincere, and disgruntled". Nevertheless, that spring Janoušek travelled to the UK to negotiate the purchase of UK and US materiél for the Czechoslovak Air Force. On 8 June 1946 he took part in a victory parade in London, and on 11 June he attended a Garden at Buckingham Palace#Garden parties, Royal Garden Party hosted by HM King George VI. On 15 February 1947 Janoušek was appointed interim inspector of Air Defense by the General Staff. On 15 September he was a member of the Czechoslovak delegation at the seventh anniversary of the Battle of Britain. But at the same time the Czechoslovak Communist Obranné zpravodajství (OBZ) military and political intelligence organisation was monitoring Janoušek's social life and visits to foreign embassies. On 15 October 1947 General Boček again appraised Janoušek, declaring "Janoušek is not suitable for a position in Command because of his attitude and therefore should only be employed in administration." In February 1948 the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia 1948 Czechoslovak coup d'état, seized power. Three days later Boček ordered Janoušek, Brig Gen Alois Liška and military intelligence chief Gen František Moravec to take leave "for health reasons" pending a final decision about their future. In March Gen Šimon Drgáč personally told Janoušek there was no place for him under the Communist régime. Janoušek applied for a job at the International Civil Aviation Organization in Montreal, for which he had helped to lay the foundations at the 1944 Chicago conference. Dr Josef Dubský at the ICAO offered him a job, but Bedřich Reicin at the OBZ refused to let Janoušek leave Czechoslovakia.

In February 1948 the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia 1948 Czechoslovak coup d'état, seized power. Three days later Boček ordered Janoušek, Brig Gen Alois Liška and military intelligence chief Gen František Moravec to take leave "for health reasons" pending a final decision about their future. In March Gen Šimon Drgáč personally told Janoušek there was no place for him under the Communist régime. Janoušek applied for a job at the International Civil Aviation Organization in Montreal, for which he had helped to lay the foundations at the 1944 Chicago conference. Dr Josef Dubský at the ICAO offered him a job, but Bedřich Reicin at the OBZ refused to let Janoušek leave Czechoslovakia.

Arrest, trial and political imprisonment

An OBZ double agent, Jaroslav Doubravský, lured Janoušek into trying to escape from Czechoslovakia. On 30 April 1948 Janoušek was arrested in the escape attempt, and on 2 May he was taken to an OBZ-controlled prison in the Hradčany district of Prague. A High Military Tribunalcourt-martial

A court-martial (plural ''courts-martial'' or ''courts martial'', as "martial" is a postpositive adjective) is a military court or a trial conducted in such a court. A court-martial is empowered to determine the guilt of members of the arme ...

led Janoušek on 17 June and sentenced him to 18 years imprisonment. He was stripped of his air force rank, his university doctorate and his awards. On 30 December the tribunal rejected his claim of a Trial#Mistrials, mistrial but on 9 February 1949 Janoušek was retried and his sentence was increased to 19 years. He appealed, but on 26 May the appeal court confirmed his sentence.

Janoušek was imprisoned in Bory prison in Plzeň. There a prison guard approached him with an escape plan. Janoušek thought it was a trap and rejected the proposal. The guard was arrested in November 1949 and sentenced to life imprisonment

Life imprisonment is any sentence (law), sentence of imprisonment under which the convicted individual is to remain incarcerated for the rest of their natural life (or until pardoned or commuted to a fixed term). Crimes that result in life impr ...

. Janoušek and another political prisoner, Major René Černý, were accused of failing to report the escape proposal. In March 1950 they were tried and sentenced to life imprisonment. On 18 April the prison authorities announced that they had uncovered a plan for a Prison riot, prison uprising and mass escape. Černý, the Christian and Democratic Union – Czechoslovak People's Party, ČSL politician Stanislav Broj and a guard were tried and executed and other prisoners were given long sentences. Janoušek was moved to a prison at Opava.

In June 1952 Janoušek was moved to Leopoldov Prison, a converted 17th-century fortress in Slovakia. In 1955 President Antonín Zápotocký granted a partial amnesty and Janoušek's life sentence was reduced to 25 years. In November 1956 he was moved again, to a prison at Ruzyně near Prague. Before the end of the year Janoušek's 25-year sentence was reduced to four years and his earlier 19-year sentence was reduced to 16 years.

In June 1952 Janoušek was moved to Leopoldov Prison, a converted 17th-century fortress in Slovakia. In 1955 President Antonín Zápotocký granted a partial amnesty and Janoušek's life sentence was reduced to 25 years. In November 1956 he was moved again, to a prison at Ruzyně near Prague. Before the end of the year Janoušek's 25-year sentence was reduced to four years and his earlier 19-year sentence was reduced to 16 years.

Release, exoneration and death

In 1960, on the 15th anniversary of the liberation of Czechoslovakia, President Antonín Novotný granted an amnesty to many political prisoners. It included Janoušek, who was released on 9 May. All his property had been confiscated and he had only a small pension, so he took work as a clerk at a state enterprise in Prague. He worked until 1967, when he was 74 years old and could retire on a higher pension. On 5 July 1968, during thePrague Spring

The Prague Spring (; ) was a period of liberalization, political liberalization and mass protest in

the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic. It began on 5 January 1968, when reformist Alexander Dubček was elected Secretary (title), First Secre ...

, a Higher Military Tribunal at Příbram in Bohemia cancelled Janoušek's convictions. Janoušek died on 27 October 1971, three days before what would have been his 78th birthday. He was buried in the Libeň suburb of Prague.

Honours and monuments

Awards and decorations

Monuments and grave

There is a plaque in memory of Janoušek in Ulice Železné lávky in the Prague 1 district. A street in the Černý Most suburb of Prague is named "Generála Janouška" after him. In 2011 a European Military Rehabilitation Centre and Air Marshal Karel Janoušek Museum were established at Jemnice in Moravia. In the Czech Republic there is a General Janoušek Flying Club, which in October 2013 took part in commemorations of the 120th anniversary of Janoušek's birth. In 2014 Janoušek's remains were exhumed from the Libeň Cemetery in Prague and on 12 May they were reinterred in the Šárka Cemetery. Janoušek's life in the Second World War is the subject of Swedish power metal band Sabaton (band), Sabaton's song ''Far from the Fame'', on their 2014 album Heroes (Sabaton album), Heroes.References

Notes

Bibliography

* *External links

* * {{DEFAULTSORT:Janousek, Karel 1893 births 1971 deaths Charles University alumni Commanders of the Order of Polonia Restituta Commanders of the Legion of Honour Czechoslovak military personnel of World War I Czechoslovak military personnel of World War II Honorary Knights Commander of the Order of the Bath People from Přerov Recipients of the Milan Rastislav Stefanik Order Royal Air Force air marshals of World War II Recipients of the Czechoslovak War Cross 1939–1945 Czechoslovak Legion personnel Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve personnel of World War II