Kansai Accent on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The is a group of Japanese dialects in the Kansai region (Kinki region) of Japan. In Japanese, is the common name and it is called in technical terms. The dialects of Kyoto and Osaka are known as , and were particularly referred to as such in the Edo period. The Kansai dialect is typified by the speech of Osaka, the major city of Kansai, which is referred to specifically as . It is characterized as being both more melodic and harsher by speakers of the standard language.Omusubi: Japan's Regional Diversity

The is a group of Japanese dialects in the Kansai region (Kinki region) of Japan. In Japanese, is the common name and it is called in technical terms. The dialects of Kyoto and Osaka are known as , and were particularly referred to as such in the Edo period. The Kansai dialect is typified by the speech of Osaka, the major city of Kansai, which is referred to specifically as . It is characterized as being both more melodic and harsher by speakers of the standard language.Omusubi: Japan's Regional Diversity

retrieved January 23, 2007

* is nearer to than to , as it is in Tokyo.

*In Standard,

* is nearer to than to , as it is in Tokyo.

*In Standard,

The pitch accent in Kansai dialect is very different from the standard Tokyo accent, so non-Kansai Japanese can recognize Kansai people easily from that alone. The Kansai pitch accent is called the Kyoto-Osaka type accent ( 京阪式アクセント, ''Keihan-shiki akusento'') in technical terms. It is used in most of Kansai, Shikoku and parts of western

The pitch accent in Kansai dialect is very different from the standard Tokyo accent, so non-Kansai Japanese can recognize Kansai people easily from that alone. The Kansai pitch accent is called the Kyoto-Osaka type accent ( 京阪式アクセント, ''Keihan-shiki akusento'') in technical terms. It is used in most of Kansai, Shikoku and parts of western

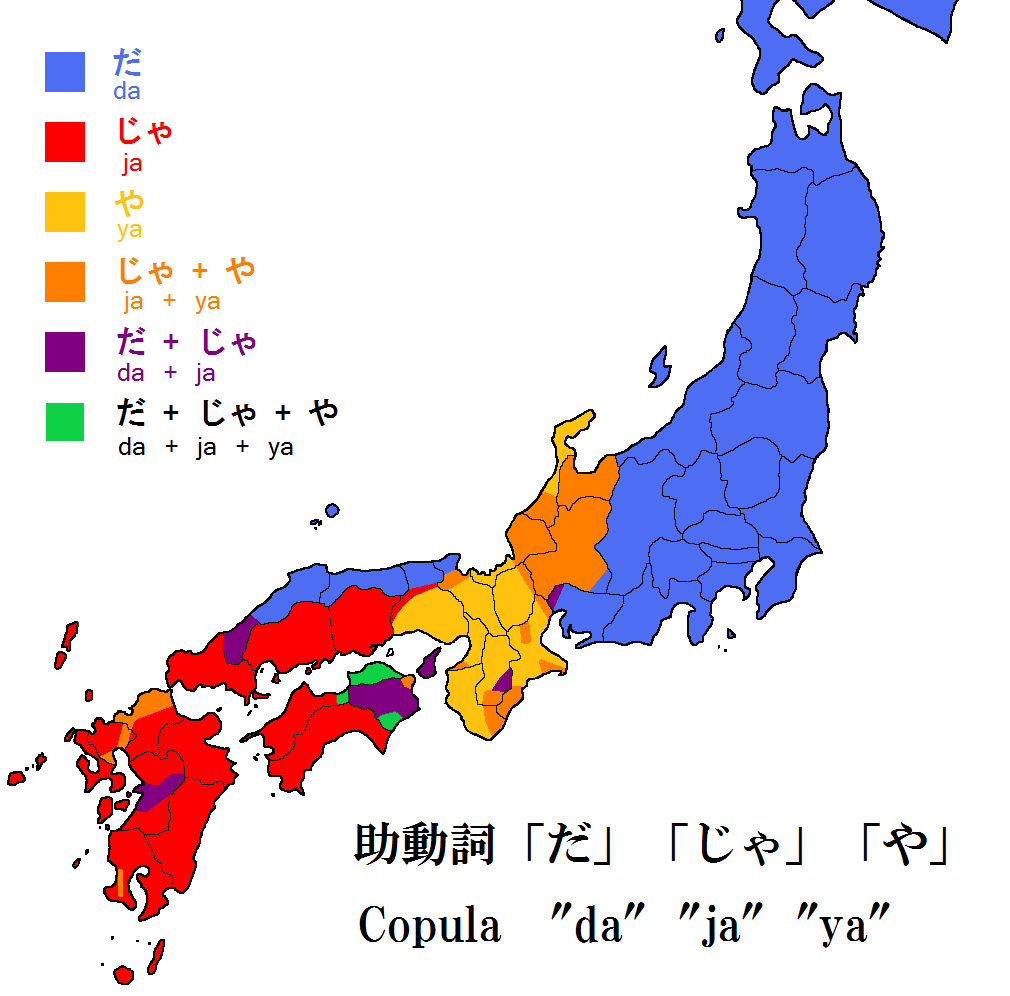

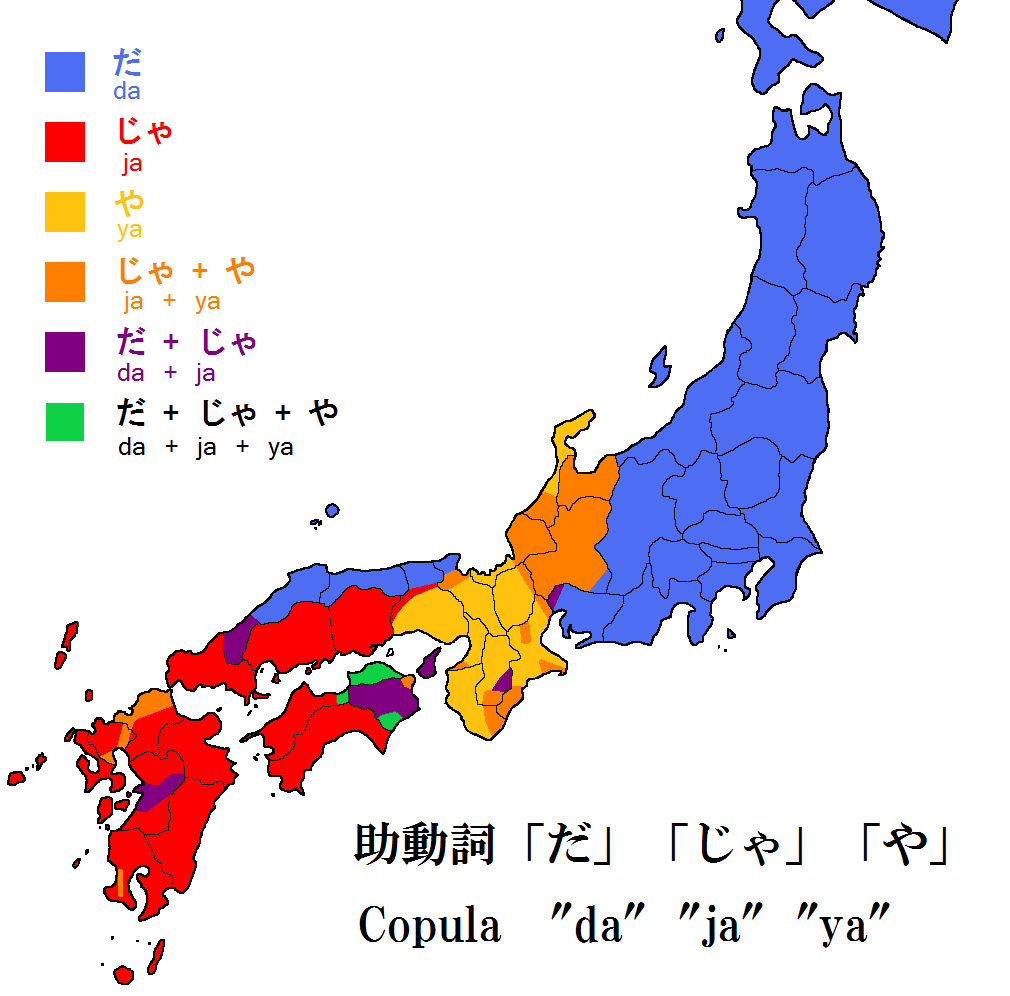

The standard Japanese copula ''da'' is replaced by the Kansai dialect copula ''ya''. The inflected forms maintain this difference, resulting in ''yaro'' for ''darō'' (presumptive), ''yatta'' for ''datta'' (past); ''darō'' is often considered to be a masculine expression, but ''yaro'' is used by both men and women. The negative copula ''de wa nai'' or ''ja nai'' is replaced by ''ya nai'' or ''ya arahen/arehen'' in Kansai dialect. ''Ya'' originated from ''ja'' (a variation of ''dearu'') in late Edo period and is still commonly used in other parts of western Japan like

The standard Japanese copula ''da'' is replaced by the Kansai dialect copula ''ya''. The inflected forms maintain this difference, resulting in ''yaro'' for ''darō'' (presumptive), ''yatta'' for ''datta'' (past); ''darō'' is often considered to be a masculine expression, but ''yaro'' is used by both men and women. The negative copula ''de wa nai'' or ''ja nai'' is replaced by ''ya nai'' or ''ya arahen/arehen'' in Kansai dialect. ''Ya'' originated from ''ja'' (a variation of ''dearu'') in late Edo period and is still commonly used in other parts of western Japan like

Historically, extensive use of keigo (honorific speech) was a feature of the Kansai dialect, especially in Kyōto, while the Kantō dialect, from which standard Japanese developed, formerly lacked it. Keigo in standard Japanese was originally borrowed from the medieval Kansai dialect. However, keigo is no longer considered a feature of the dialect since Standard Japanese now also has it. Even today, keigo is used more often in Kansai than in the other dialects except for the standard Japanese, to which people switch in formal situations.

In modern Kansai dialect, -''haru'' (sometimes -''yaharu'' except ''godan'' verbs, mainly Kyōto) is used for showing reasonable respect without formality especially in Kyōto. The conjugation before -''haru'' has two varieties between Kyōto and Ōsaka (see the table below). In Southern Hyōgo, including Kōbe, ''-te ya'' is used instead of -''haru''. In formal speech, -''naharu'' and -''haru'' connect with -''masu'' and -''te ya'' changes -''te desu''.

-''Haru'' was originally a shortened form of -''naharu'', a transformation of -''nasaru''. -''Naharu'' has been dying out due to the spread of -''haru'' but its imperative form -''nahare'' (mainly Ōsaka) or -''nahai'' (mainly Kyōto, also -''nai'') and negative imperative form -''nasan'na'' or -''nahan'na'' has comparatively survived because -''haru'' lacks an imperative form. In more honorific speech, ''o- yasu'', a transformation of ''o- asobasu'', is used especially in Kyōto and its original form is same to its imperative form, showing polite invitation or order. ''Oide yasu'' and ''okoshi yasu'' (more respectful), meaning "welcome", are the common phrases of sightseeing areas in Kyōto. -''Te okun nahare'' (also -''tokun nahare'', -''toku nahare'') and -''te okure yasu'' (also -''tokure yasu'', -''tokuryasu'') are used instead of -''te kudasai'' in standard Japanese.

Historically, extensive use of keigo (honorific speech) was a feature of the Kansai dialect, especially in Kyōto, while the Kantō dialect, from which standard Japanese developed, formerly lacked it. Keigo in standard Japanese was originally borrowed from the medieval Kansai dialect. However, keigo is no longer considered a feature of the dialect since Standard Japanese now also has it. Even today, keigo is used more often in Kansai than in the other dialects except for the standard Japanese, to which people switch in formal situations.

In modern Kansai dialect, -''haru'' (sometimes -''yaharu'' except ''godan'' verbs, mainly Kyōto) is used for showing reasonable respect without formality especially in Kyōto. The conjugation before -''haru'' has two varieties between Kyōto and Ōsaka (see the table below). In Southern Hyōgo, including Kōbe, ''-te ya'' is used instead of -''haru''. In formal speech, -''naharu'' and -''haru'' connect with -''masu'' and -''te ya'' changes -''te desu''.

-''Haru'' was originally a shortened form of -''naharu'', a transformation of -''nasaru''. -''Naharu'' has been dying out due to the spread of -''haru'' but its imperative form -''nahare'' (mainly Ōsaka) or -''nahai'' (mainly Kyōto, also -''nai'') and negative imperative form -''nasan'na'' or -''nahan'na'' has comparatively survived because -''haru'' lacks an imperative form. In more honorific speech, ''o- yasu'', a transformation of ''o- asobasu'', is used especially in Kyōto and its original form is same to its imperative form, showing polite invitation or order. ''Oide yasu'' and ''okoshi yasu'' (more respectful), meaning "welcome", are the common phrases of sightseeing areas in Kyōto. -''Te okun nahare'' (also -''tokun nahare'', -''toku nahare'') and -''te okure yasu'' (also -''tokure yasu'', -''tokuryasu'') are used instead of -''te kudasai'' in standard Japanese.

In some cases, Kansai dialect uses entirely different words. The verb ''hokasu'' corresponds to standard Japanese ''suteru'' "to throw away", and ''metcha'' corresponds to the standard Japanese slang ''chō'' "very". ''Chō,'' in Kansai dialect, means "a little" and is a contracted form of ''chotto.'' Thus the phrase ''chō matte'' "wait a minute" by a Kansai person sounds strange to a Tokyo person.

Some Japanese words gain entirely different meanings or are used in different ways when used in Kansai dialect. One such usage is of the word ''naosu'' (usually used to mean "correct" or "repair" in the standard language) in the sense of "put away" or "put back." For example, ''kono jitensha naoshite'' means "please put back this bicycle" in Kansai, but many standard speakers are bewildered since in standard Japanese it would mean "please repair this bicycle".

Another widely recognized Kansai-specific usage is of ''aho''. Basically equivalent to the standard ''baka'' "idiot, fool", ''aho'' is both a term of reproach and a term of endearment to the Kansai speaker, somewhat like English ''twit'' or ''silly''. ''Baka'', which is used as "idiot" in most regions, becomes "complete moron" and a stronger insult than ''aho''. Where a Tokyo citizen would almost certainly object to being called ''baka'', being called ''aho'' by a Kansai person is not necessarily much of an insult. Being called ''baka'' by a Kansai speaker is however a much more severe criticism than it would be by a Tokyo speaker. Most Kansai speakers cannot stand being called ''baka'' but don't mind being called ''aho''.

In some cases, Kansai dialect uses entirely different words. The verb ''hokasu'' corresponds to standard Japanese ''suteru'' "to throw away", and ''metcha'' corresponds to the standard Japanese slang ''chō'' "very". ''Chō,'' in Kansai dialect, means "a little" and is a contracted form of ''chotto.'' Thus the phrase ''chō matte'' "wait a minute" by a Kansai person sounds strange to a Tokyo person.

Some Japanese words gain entirely different meanings or are used in different ways when used in Kansai dialect. One such usage is of the word ''naosu'' (usually used to mean "correct" or "repair" in the standard language) in the sense of "put away" or "put back." For example, ''kono jitensha naoshite'' means "please put back this bicycle" in Kansai, but many standard speakers are bewildered since in standard Japanese it would mean "please repair this bicycle".

Another widely recognized Kansai-specific usage is of ''aho''. Basically equivalent to the standard ''baka'' "idiot, fool", ''aho'' is both a term of reproach and a term of endearment to the Kansai speaker, somewhat like English ''twit'' or ''silly''. ''Baka'', which is used as "idiot" in most regions, becomes "complete moron" and a stronger insult than ''aho''. Where a Tokyo citizen would almost certainly object to being called ''baka'', being called ''aho'' by a Kansai person is not necessarily much of an insult. Being called ''baka'' by a Kansai speaker is however a much more severe criticism than it would be by a Tokyo speaker. Most Kansai speakers cannot stand being called ''baka'' but don't mind being called ''aho''.

Here is a division theory of Kansai dialects proposed by Mitsuo Okumura in 1968; ■ shows dialects influenced by Kyoto dialect and □ shows dialects influenced by Osaka dialect, proposed by Minoru Umegaki in 1962.

* Inner Kansai dialect

** ■Kyoto dialect (southern part of Kyoto Prefecture, especially the city of Kyoto)

*** Gosho dialect (old court dialect of Kyoto Gosho)

*** Machikata dialect (Kyoto citizens' dialect including several social dialects)

*** Tanba dialect (southeastern part of former Tanba Province)

*** Southern Yamashiro dialect (southern part of former Yamashiro Province)

** □Osaka dialect (

Here is a division theory of Kansai dialects proposed by Mitsuo Okumura in 1968; ■ shows dialects influenced by Kyoto dialect and □ shows dialects influenced by Osaka dialect, proposed by Minoru Umegaki in 1962.

* Inner Kansai dialect

** ■Kyoto dialect (southern part of Kyoto Prefecture, especially the city of Kyoto)

*** Gosho dialect (old court dialect of Kyoto Gosho)

*** Machikata dialect (Kyoto citizens' dialect including several social dialects)

*** Tanba dialect (southeastern part of former Tanba Province)

*** Southern Yamashiro dialect (southern part of former Yamashiro Province)

** □Osaka dialect (

Kyōto-ben (京都弁) or Kyō-kotoba ( 京言葉) is characterized by development of politeness and indirectness expressions. Kyoto-ben is often regarded as elegant and feminine dialect because of its characters and the image of Gion's '' geisha'' (''geiko-han'' and '' maiko-han'' in Kyoto-ben), the most conspicuous speakers of traditional Kyoto-ben.Ryoichi Sato ed (2009). . Kyoto-ben is divided into the court dialect called ''Gosho kotoba'' (御所言葉) and the citizens dialect called ''Machikata kotoba'' (町方言葉). The former was spoken by court noble before moving the Emperor to Tokyo, and some phrases inherit at a few monzeki. The latter has subtle difference at each social class such as old merchant families at Nakagyo, craftsmen at Nishijin and

Kyōto-ben (京都弁) or Kyō-kotoba ( 京言葉) is characterized by development of politeness and indirectness expressions. Kyoto-ben is often regarded as elegant and feminine dialect because of its characters and the image of Gion's '' geisha'' (''geiko-han'' and '' maiko-han'' in Kyoto-ben), the most conspicuous speakers of traditional Kyoto-ben.Ryoichi Sato ed (2009). . Kyoto-ben is divided into the court dialect called ''Gosho kotoba'' (御所言葉) and the citizens dialect called ''Machikata kotoba'' (町方言葉). The former was spoken by court noble before moving the Emperor to Tokyo, and some phrases inherit at a few monzeki. The latter has subtle difference at each social class such as old merchant families at Nakagyo, craftsmen at Nishijin and

Kansai Dialect Self-study Site for Japanese Language Learner

The Corpus of Kansai Vernacular Japanese

- nihongoresources.com

Kansai Ben

- TheJapanesePage.com

- Kansai-ben texts and videos made by Ritsumeikan University students

Osaka-ben Study Website

- U-biq

- Osaka city {{DEFAULTSORT:Kansai Dialect Japanese dialects Kansai region

The is a group of Japanese dialects in the Kansai region (Kinki region) of Japan. In Japanese, is the common name and it is called in technical terms. The dialects of Kyoto and Osaka are known as , and were particularly referred to as such in the Edo period. The Kansai dialect is typified by the speech of Osaka, the major city of Kansai, which is referred to specifically as . It is characterized as being both more melodic and harsher by speakers of the standard language.Omusubi: Japan's Regional Diversity

The is a group of Japanese dialects in the Kansai region (Kinki region) of Japan. In Japanese, is the common name and it is called in technical terms. The dialects of Kyoto and Osaka are known as , and were particularly referred to as such in the Edo period. The Kansai dialect is typified by the speech of Osaka, the major city of Kansai, which is referred to specifically as . It is characterized as being both more melodic and harsher by speakers of the standard language.Omusubi: Japan's Regional Diversityretrieved January 23, 2007

Background

Since Osaka is the largest city in the region and its speakers gained the most media exposure over the last century, non-Kansai-dialect speakers tend to associate the dialect of Osaka with the entire Kansai region. However, technically, Kansai dialect is not a single dialect but a group of related dialects in the region. Each major city and prefecture has a particular dialect, and residents take some pride in their particular dialectal variations. The common Kansai dialect is spoken inKeihanshin

is a metropolitan region in the Kansai region of Japan encompassing the metropolitan areas of the cities of Kyoto in Kyoto Prefecture, Osaka in Osaka Prefecture and Kobe in Hyōgo Prefecture. The entire region has a population () of 19,302,746 o ...

(the metropolitan areas of the cities of Kyoto, Osaka and Kobe

Kobe ( , ; officially , ) is the capital city of Hyōgo Prefecture Japan. With a population around 1.5 million, Kobe is Japan's seventh-largest city and the third-largest port city after Tokyo and Yokohama. It is located in Kansai region, whic ...

) and its surroundings, a radius of about around the Osaka-Kyoto area (see regional differences).Mitsuo Okumura (1968). . 202 number. Tokyo: Chikuma Shobo. This article mainly discusses the Keihanshin version of the Kansai dialect in the Shōwa and Heisei period

The is the period of Japanese history corresponding to the reign of Emperor Emeritus Akihito from 8 January 1989 until his abdication on 30 April 2019. The Heisei era started on 8 January 1989, the day after the death of the Emperor Hirohito, ...

s.

Dialects of other areas have different features, some archaic, in common with the common Kansai dialect. Tajima and Tango (except Maizuru) dialects in northwest Kansai are too different to be regarded as Kansai dialects and are thus usually included in the Chūgoku dialect. Dialects spoken in Southeastern Kii Peninsula including Totsukawa and Owase

is a city located in Mie Prefecture, Japan. , the city had an estimated population of 16,910 in 9177 households and a population density of 88 persons per km2. The total area of the city was .

Geography

Owase is located in southeastern Kii Peni ...

are also far different from other Kansai dialects, and considered a language island. The Shikoku dialect and the Hokuriku dialect share many similarities with the Kansai dialects, but are classified separately.

History

The Kansai dialect has over a thousand years of history. When Kinai cities such as Nara and Kyoto were Imperial capitals, the Kinai dialect, the ancestor of the Kansai dialect, was the ''de facto'' standard Japanese. It had an influence on all of the nation including theEdo

Edo ( ja, , , "bay-entrance" or "estuary"), also romanized as Jedo, Yedo or Yeddo, is the former name of Tokyo.

Edo, formerly a ''jōkamachi'' (castle town) centered on Edo Castle located in Musashi Province, became the ''de facto'' capital of ...

dialect, the predecessor of modern Tokyo dialect. The literature style developed by the intelligentsia in Heian-kyō

Heian-kyō was one of several former names for the city now known as Kyoto. It was the official capital of Japan for over one thousand years, from 794 to 1868 with an interruption in 1180.

Emperor Kanmu established it as the capital in 794, mov ...

became the model of Classical Japanese language.

When the political and military center of Japan was moved to Edo

Edo ( ja, , , "bay-entrance" or "estuary"), also romanized as Jedo, Yedo or Yeddo, is the former name of Tokyo.

Edo, formerly a ''jōkamachi'' (castle town) centered on Edo Castle located in Musashi Province, became the ''de facto'' capital of ...

under the Tokugawa Shogunate and the Kantō region

The is a geographical area of Honshu, the largest island of Japan. In a common definition, the region includes the Greater Tokyo Area and encompasses seven prefectures: Gunma, Tochigi, Ibaraki, Saitama, Tokyo, Chiba and Kanagawa. Slight ...

grew in prominence, the Edo dialect took the place of the Kansai dialect. With the Meiji Restoration and the transfer of the imperial capital from Kyoto to Tokyo, the Kansai dialect became fixed in position as a provincial dialect. See also Early Modern Japanese.

As the Tokyo dialect was adopted with the advent of a national education/media standard in Japan, some features and intraregional differences of the Kansai dialect have diminished and changed. However, Kansai is the second most populated urban region in Japan after Kantō, with a population of about 20 million, so Kansai dialect is still the most widely spoken, known and influential non-standard Japanese dialect. The Kansai dialect's idioms are sometimes introduced into other dialects and even standard Japanese. Many Kansai people are attached to their own speech and have strong regional rivalry against Tokyo.

Since the Taishō period, the form of Japanese comedy has been developed in Osaka, and a large number of Osaka-based comedians have appeared in Japanese media with Osaka dialect, such as Yoshimoto Kogyo. Because of such associations, Kansai speakers are often viewed as being more "funny" or "talkative" than typical speakers of other dialects. Tokyo people even occasionally imitate Kansai dialect to provoke laughter or inject humor.

Phonology

In phonetic terms, Kansai dialect is characterized by strong vowels and contrasted with Tokyo dialect, characterized by its strong consonants, but the basis of the phonemes is similar. The specific phonetic differences between Kansai and Tokyo are as follows:Umegaki (1962)Vowels

* is nearer to than to , as it is in Tokyo.

*In Standard,

* is nearer to than to , as it is in Tokyo.

*In Standard, vowel reduction

In phonetics, vowel reduction is any of various changes in the acoustic ''quality'' of vowels as a result of changes in stress, sonority, duration, loudness, articulation, or position in the word (e.g. for the Creek language

The Muscogee lang ...

frequently occurs, but it is rare in Kansai. For example, the polite copula is pronounced nearly as in standard Japanese, but Kansai speakers tend to pronounce it distinctly as or even .

*In some registers, such as informal Tokyo speech, hiatuses often fuse into , as in and instead of "yummy" and "great", but are usually pronounced distinctly in Kansai dialect. In Wakayama, is also pronounced distinctly; it usually fuses into in standard Japanese and almost all other dialects.

*A recurring tendency to lengthen vowels at the end of monomoraic nouns. Common examples are for "tree", for "mosquito" and for "eye".

*Contrarily, long vowels in Standard inflections are sometimes shortened. This is particularly noticeable in the volitional conjugation of verbs. For instance, meaning "shall we go?" is shortened in Kansai to . The common phrase of agreement, meaning "that's it", is pronounced or even in Kansai.

*When vowels and semivowel follow , they sometimes palatalize with or . For example, "I love you" becomes , 日曜日 "Sunday" becomes にっちょうび and 賑やか "lively, busy" becomes にんぎゃか .

Consonants

*The syllable ひ is nearer to than to , as it is in Tokyo. *The '' yotsugana'' are two distinct syllables, as they are in Tokyo, but Kansai speakers tend to pronounce じ and ず as and in place of Standard and . *Intervocalic is pronounced either or in free variation, but is declining now. *In a provocative speech, becomes as well as Tokyo Shitamachi dialect. *The use of in place of . Some debuccalization of is apparent in most Kansai speakers, but it seems to have progressed more in morphological suffixes and inflections than in core vocabulary. This process has produced はん for さん ''- san'' "Mr., Ms.", まへん for ません (formal negative form), and まひょ for ましょう (formal volitional form), ひちや for 質屋 "pawnshop", among other examples. *The change of and in some words such as さぶい for 寒い "cold". *Especially in the rural areas, are sometimes confused. For example, でんでん for 全然 "never, not at all", かだら or からら for 体 "body". There is a joke describing these confusions: 淀川の水飲んれ腹らら下りや for 淀川の水飲んで腹だだ下りや "I drank water of Yodo River and have the trots". *The + vowel in the verb conjugations is sometimes changed to as well as colloquial Tokyo speech. For example, 何してるねん? "What are you doing?" often changes 何してんねん? in fluent Kansai speech.Pitch accent

The pitch accent in Kansai dialect is very different from the standard Tokyo accent, so non-Kansai Japanese can recognize Kansai people easily from that alone. The Kansai pitch accent is called the Kyoto-Osaka type accent ( 京阪式アクセント, ''Keihan-shiki akusento'') in technical terms. It is used in most of Kansai, Shikoku and parts of western

The pitch accent in Kansai dialect is very different from the standard Tokyo accent, so non-Kansai Japanese can recognize Kansai people easily from that alone. The Kansai pitch accent is called the Kyoto-Osaka type accent ( 京阪式アクセント, ''Keihan-shiki akusento'') in technical terms. It is used in most of Kansai, Shikoku and parts of western Chūbu region

The , Central region, or is a region in the middle of Honshu, Honshū, Japan, Japan's main island. In a wide, classical definition, it encompasses nine prefectures (''ken''): Aichi Prefecture, Aichi, Fukui Prefecture, Fukui, Gifu Prefecture ...

. The Tokyo accent distinguishes words only by downstep, but the Kansai accent distinguishes words also by initial tones, so Kansai dialect has more pitch patterns than standard Japanese. In the Tokyo accent, the pitch between first and second morae usually change, but in the Kansai accent, it does not always.

Below is a list of simplified Kansai accent patterns. H represents a high pitch and L represents a low pitch.

# or

#* The high pitch appears on the first mora and the others are low: H-L, H-L-L, H-L-L-L, etc.

#* The high pitch continues for the set mora and the rest are low: H-H-L, H-H-L-L, H-H-H-L, ''etc.''

#* The high pitch continues to the last: H-H, H-H-H, H-H-H-H, ''etc.''

# or

#* The pitch rises drastically the middle set mora and falls again: L-H-L, L-H-L-L, L-L-H-L, ''etc.''

#* The pitch rises drastically the last mora: L-L-H, L-L-L-H, L-L-L-L-H, ''etc.''

#** If particles attach to the end of the word, all moras are low: L-L-L(-H), L-L-L-L(-H), L-L-L-L-L(-H)

#* With two-mora words, there are two accent patterns. Both of these tend to be realized in recent years as L-H, L-H(-L).

#** The second mora rises and falls quickly. If particles attach to the end of the word, the fall is sometimes not realized: L-HL, L-HL(-L) or L-H(-L)

#** The second mora does not fall. If particles attach to the end of the word, both moras are low: L-H, L-L(-H)

The Kansai accent includes local variations. The traditional pre-modern Kansai accent is kept in Shikoku and parts of the Kii Peninsula such as Tanabe city. Even between Kyoto and Osaka, only 30 minutes by train, a few of the pitch accents change between words. For example, ''Tōkyō ikimashita'' ( went to Tokyo) is pronounced H-H-H-H H-H-H-L-L in Osaka, L-L-L-L H-H-L-L-L in Kyoto.

Grammar

Many words and grammar structures in Kansai dialect are contractions of theirclassical Japanese

The classical Japanese language ( ''bungo'', "literary language"), also called "old writing" ( ''kobun''), sometimes simply called "Medieval Japanese" is the literary form of the Japanese language that was the standard until the early Shōwa pe ...

equivalents (it is unusual to contract words in such a way in standard Japanese). For example, ''chigau'' (to be different or wrong) becomes ''chau'', ''yoku'' (well) becomes ''yō'', and ''omoshiroi'' (interesting or funny) becomes ''omoroi''. These contractions follow similar inflection rules as their standard forms so ''chau'' is politely said ''chaimasu'' in the same way as ''chigau'' is inflected to ''chigaimasu''.

Verbs

Kansai dialect also has two types of regular verb, 五段 ''godan verbs'' (''-u'' verbs) and 一段 ''ichidan verbs'' (''-ru'' verbs), and two irregular verbs, 来る ("to come") and する ("to do"), but some conjugations are different from standard Japanese. The geminated consonants found in godan verbs of standard Japanese verbal inflections are usually replaced with long vowels (often shortened in 3 morae verbs) in Kansai dialect (See alsoOnbin

Japanese is an agglutinative, synthetic, mora-timed language with simple phonotactics, a pure vowel system, phonemic vowel and consonant length, and a lexically significant pitch-accent. Word order is normally subject–object–verb with par ...

). Thus, for the verb 言う ("to say"), the past tense in standard Japanese 言った or ("said") becomes 言うた in Kansai dialect. This particular verb is a dead giveaway of a native Kansai speaker, as most will unconsciously say 言うて instead of 言って or even if well-practiced at speaking in standard Japanese. Other examples of geminate replacement are 笑った ("laughed") becoming 笑うた or わろた and 貰った ("received") becoming 貰うた , もろた or even もうた .

A compound verb てしまう (to finish something or to do something in unintentional or unfortunate circumstances) is contracted to ちまう or ちゃう in colloquial Tokyo speech but to てまう in Kansai speech. Thus, しちまう , or しちゃう , becomes してまう . Furthermore, as the verb しまう is affected by the same sound changes as in other 五段 godan verbs, the past tense of this form is rendered as てもうた or てもた rather than ちまった or ちゃった : 忘れちまった or 忘れちゃった ("I forgot t) in Tokyo is 忘れてもうた or 忘れてもた in Kansai.

The long vowel of the volitional form is often shortened; for example, 使おう (the volitional form of ''tsukau'') becomes 使お , 食べよう (the volitional form of 食べる ) becomes 食べよ . The irregular verb する has special volitinal form しょ(う) instead of しよう . The volitinal form of another irregular verb 来る is 来よう as well as the standard Japanese, but when 来る is used as a compound verb てくる , てこよう is sometimes replaced with てこ(う) in Kansai.

The causative

In linguistics, a causative (abbreviated ) is a valency-increasing operationPayne, Thomas E. (1997). Describing morphosyntax: A guide for field linguists'' Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 173–186. that indicates that a subject either ...

verb ending is usually replaced with in Kansai dialect; for example, させる (causative form of ) changes さす , 言わせる (causative form of 言う ) changes 言わす . Its -te form and perfective form change to and ; they also appear in transitive ichidan verbs such as 見せる ("to show"), e.g. 見して for 見せて .

The potential verb endings for 五段 godan and られる for 一段 ichidan, recently often shortened れる , are common between the standard Japanese and Kansai dialect. For making their negative forms, it is only to replace ない with ん or へん (See Negative). However, mainly in Osaka, potential negative form of 五段 godan verbs is often replaced with such as 行かれへん instead of 行けない and 行けへん "can't go". This is because overlaps with Osakan negative conjugation. In western Japanese including Kansai dialect, a combination of よう and ん negative form is used as a negative form of the personal impossibility such as よう言わん "I can't say anything (in disgust or diffidence)".

Existence verbs

In Standard Japanese, the verb '' iru'' is used for reference to the existence of ananimate

Animation is a method by which still figures are manipulated to appear as moving images. In traditional animation, images are drawn or painted by hand on transparent celluloid sheets to be photographed and exhibited on film. Today, most ani ...

object, and ''iru'' is replaced with ''oru'' in humble language and some written language. In western Japanese, ''oru'' is used not only in humble language but also in all other situations instead of ''iru''.

Kansai dialect belongs to western Japanese, but いる and its variation, いてる (mainly Osaka), are used in Osaka, Kyoto, Shiga and so on. People in these areas, especially Kyoto women, tend to consider おる an outspoken or contempt word. They usually use it for mates, inferiors and animals; avoid using for elders (exception: respectful expression ''orareru'' and humble expression ''orimasu''). In other areas such as Hyogo and Mie, いる is hardly used and おる does not have the negative usage. In parts of Wakayama, いる is replaced with ある , which is used for inanimate objects in most other dialects.

The verb おる is also used as an auxiliary verb and usually pronounced in that case. In Osaka, Kyoto, Shiga, northern Nara and parts of Mie, mainly in masculine speech, よる shows annoying or contempt feelings for a third party, usually milder than やがる . In Hyogo, southern Nara and parts of Wakayama, よる is used for progressive aspect (See Aspect).

Negative

In informal speech, the negative verb ending, which is ない in standard Japanese, is expressed with ん or へん , as in 行かん and 行かへん "not going", which is 行かない in standard Japanese. ん is a transformation of the classical Japanese negative form ぬ and is also used for some idioms in standard Japanese. へん is the result of contraction and phonological change of はせん , the emphatic form of . やへん , a transitional form between はせん and へん , is sometimes still used for 一段 ichidan verbs. The godan verbs conjugation before ''-hen'' has two varieties: the more common conjugation is like 行かへん , but ''-ehen'' like 行けへん is also used in Osaka. When the vowel before へん is , へん often changes to ひん , especially in Kyoto. The past negative form is んかった and , a mixture of ん or へん and the standard past negative form なかった . In traditional Kansai dialect, なんだ and へなんだ is used in the past negative form. * 五段 godan verbs: 使う ("to use") becomes 使わん and 使わへん , 使えへん * 上一段 kami-ichidan verbs: 起きる ("to wake up") becomes 起きん and 起きやへん , 起きへん , 起きひん ** one mora verbs: 見る ("to see") becomes 見ん and 見やへん , 見えへん , 見いひん * 下一段 shimo-ichidan verbs: 食べる ("to eat") becomes 食べん and 食べやへん , 食べへん ** one mora verbs: 寝る ("to sleep") becomes 寝ん and 寝やへん , 寝えへん * s-irregular verb: する becomes せん and しやへん , せえへん , しいひん * k-irregular verb: 来る becomes 来ん and きやへん , けえへん , きいひん ** 来おへん , a mixture けえへん with standard 来ない , is also used lately by young people, especially in Kobe. Generally speaking, へん is used in almost negative sentences and ん is used in strong negative sentences and idiomatic expressions. For example, んといて or んとって instead of standard ないで means "please do not to do"; んでもええ instead of standard なくてもいい means "need not do";んと(あかん) instead of standard なくちゃ(いけない) or ねばならない means "must do". The last expression can be replaced by な(あかん) or んならん .Imperative

Kansai dialect has two imperative forms. One is the normal imperative form, inherited from Late Middle Japanese. The ろ form for ichidan verbs in standard Japanese is much rarer and replaced by or in Kansai. The normal imperative form is often followed by よ or や . The other is a soft and somewhat feminine form which uses the (ます stem), an abbreviation of + . The end of the soft imperative form is often elongated and is generally followed by や or な . In Kyoto, women often add よし to the soft imperative form. * godan verbs: 使う becomes 使え in the normal form, 使い(い) in the soft one. * 上一段 kami-ichidan verbs: 起きる becomes 起きい (L-H-L) in the normal form, 起き(い) (L-L-H) in the soft one. * 下一段 shimo-ichidan verbs: 食べる becomes 食べえ (L-H-L) in the normal form, 食べ(え) (L-L-H) in the soft one. * s-irregular verb: する becomes せえ in the normal form, し(い) in the soft one. * k-irregular verb: 来る becomes こい in the normal form, き(い) in the soft one. In the negative imperative mood, Kansai dialect also has the somewhat soft form which uses the ''ren'yōkei'' + な , an abbreviation of the ''ren'yōkei'' + なさるな . な sometimes changes to なや or ないな . This soft negative imperative form is the same as the soft imperative and な , Kansai speakers can recognize the difference by accent, but Tokyo speakers are sometimes confused by a command ''not to do'' something, which they interpret as an order to ''do'' it. Accent on the soft imperative form is flat, and the accent on the soft negative imperative form has a downstep before ''na''. * 五段 godan verbs: 使う becomes 使うな in the normal form, 使いな in the soft one. * 上一段 kami-ichidan verbs: 起きる becomes 起きるな in the normal form, 起きな in the soft one. * 下一段 shimo-ichidan verbs: 食べる becomes 食べるな in the normal form, 食べな in the soft one. * s-irregular verb: する becomes するな or すな in the normal form, しな in the soft one. * k-irregular verb: 来る becomes 来るな in the normal form, きな in the soft one.Adjectives

Thestem

Stem or STEM may refer to:

Plant structures

* Plant stem, a plant's aboveground axis, made of vascular tissue, off which leaves and flowers hang

* Stipe (botany), a stalk to support some other structure

* Stipe (mycology), the stem of a mushro ...

of adjective forms in Kansai dialect is generally the same as in standard Japanese, except for regional vocabulary differences. The same process that reduced the Classical Japanese terminal and attributive endings (し and き , respectively) to has reduced also the ren'yōkei ending く to , yielding such forms as 早う (contraction of 早う ) for 早く ("quickly"). Dropping the consonant from the final mora in all forms of adjective endings has been a frequent occurrence in Japanese over the centuries (and is the origin of such forms as ありがとう and おめでとう ), but the Kantō speech preserved く while reducing し and き to , thus accounting for the discrepancy in the standard language (see also Onbin

Japanese is an agglutinative, synthetic, mora-timed language with simple phonotactics, a pure vowel system, phonemic vowel and consonant length, and a lexically significant pitch-accent. Word order is normally subject–object–verb with par ...

)

The ending can be dropped and the last vowel of the adjective's stem can be stretched out for a second mora, sometimes with a tonal change for emphasis. By this process, ''omoroi'' "interesting, funny" becomes ''omorō'' and ''atsui'' "hot" becomes ''atsū'' or ''attsū''. This use of the adjective's stem, often as an exclamation, is seen in classical literature and many dialects of modern Japanese, but is more often used in modern Kansai dialect.

There is not a special conjugated form for presumptive of adjectives in Kansai dialect, it is just addition of やろ to the plain form. For example, 安かろう (the presumptive form of 安い "cheap") is hardly used and is usually replaced with the plain form + やろ likes 安いやろ . Polite suffixes です/だす/どす and ます are also added やろ for presumptive form instead of でしょう in standard Japanese. For example, 今日は晴れでしょう ("It may be fine weather today") is replaced with 今日は晴れですやろ .

Copulae

The standard Japanese copula ''da'' is replaced by the Kansai dialect copula ''ya''. The inflected forms maintain this difference, resulting in ''yaro'' for ''darō'' (presumptive), ''yatta'' for ''datta'' (past); ''darō'' is often considered to be a masculine expression, but ''yaro'' is used by both men and women. The negative copula ''de wa nai'' or ''ja nai'' is replaced by ''ya nai'' or ''ya arahen/arehen'' in Kansai dialect. ''Ya'' originated from ''ja'' (a variation of ''dearu'') in late Edo period and is still commonly used in other parts of western Japan like

The standard Japanese copula ''da'' is replaced by the Kansai dialect copula ''ya''. The inflected forms maintain this difference, resulting in ''yaro'' for ''darō'' (presumptive), ''yatta'' for ''datta'' (past); ''darō'' is often considered to be a masculine expression, but ''yaro'' is used by both men and women. The negative copula ''de wa nai'' or ''ja nai'' is replaced by ''ya nai'' or ''ya arahen/arehen'' in Kansai dialect. ''Ya'' originated from ''ja'' (a variation of ''dearu'') in late Edo period and is still commonly used in other parts of western Japan like Hiroshima

is the capital of Hiroshima Prefecture in Japan. , the city had an estimated population of 1,199,391. The gross domestic product (GDP) in Greater Hiroshima, Hiroshima Urban Employment Area, was US$61.3 billion as of 2010. Kazumi Matsui h ...

, and is also used stereotypically by old men in fiction.

''Ya'' and ''ja'' are used only informally, analogically to the standard ''da'', while the standard ''desu'' is by and large used for the polite (teineigo) copula. For polite speech, -''masu'', ''desu'' and ''gozaimasu'' are used in Kansai as well as in Tokyo, but traditional Kansai dialect has its own polite forms. ''Desu'' is replaced by ''dasu'' in Osaka and ''dosu'' in Kyoto. There is another unique polite form ''omasu'' and it is often replaced by ''osu'' in Kyoto. The usage of ''omasu/osu'' is same as ''gozaimasu'', the polite form of the verb ''aru'' and also be used for polite form of adjectives, but it is more informal than ''gozaimasu''. In Osaka, ''dasu'' and ''omasu'' are sometimes shortened to ''da'' and ''oma''. ''Omasu'' and ''osu'' have their negative forms ''omahen'' and ''ohen''.

When some sentence-final particles and a presumptive inflection ''yaro'' follow -''su'' ending polite forms, ''su'' is often combined especially in Osaka. Today, this feature is usually considered to be dated or exaggerated Kansai dialect.

* -n'na (-su + na), emphasis. e.g. ''Bochi-bochi den'na.'' ("So-so, you know.")

* -n'nen (-su + nen), emphasis. e.g. ''Chaiman'nen.'' ("It is wrong")

* -ngana (-su + gana), emphasis. e.g. ''Yoroshū tanomimangana.'' ("Nice to meet you")

* -kka (-su + ka), question. e.g. ''Mōkarimakka?'' ("How's business?")

* -n'no (-su + no), question. e.g. ''Nani yūteman'no?'' ("What are you talking about?")

* -sse (-su + e, a variety of yo), explain, advise. e.g. ''Ee toko oshiemasse!'' ("I'll show you a nice place!")

* -ssharo (-su + yaro), surmise, make sure. e.g. ''Kyō wa hare dessharo.'' ("It may be fine weather today")

Aspect

In common Kansai dialect, there are two forms for thecontinuous and progressive aspects

The continuous and progressive aspects (abbreviated and ) are grammatical aspects that express incomplete action ("to do") or state ("to be") in progress at a specific time: they are non-habitual, imperfective aspects.

In the grammars of many l ...

-''teru'' and -''toru''; the former is a shortened form of -''te iru'' just as does standard Japanese, the latter is a shortened form of -''te oru'' which is common to other western Japanese. The proper use between -''teru'' and -''toru'' is same as ''iru'' and ''oru''.

In the expression to the condition of inanimate objects, -''taru'' or -''taaru'' form, a shortened form of -''te aru''. In standard Japanese, -''te aru'' is only used with transitive verbs, but Kansai -''taru'' or -''taaru'' is also used with intransitive verbs. One should note that -''te yaru'', "to do for someone," is also contracted to -''taru'' (-''charu'' in Senshu and Wakayama), so as not to confuse the two.

Other Western Japanese as Chūgoku and Shikoku dialects has the discrimination of grammatical aspect

In linguistics, aspect is a grammatical category that expresses how an action, event, or state, as denoted by a verb, extends over time. Perfective aspect is used in referring to an event conceived as bounded and unitary, without reference to ...

, -''yoru'' in progressive

Progressive may refer to:

Politics

* Progressivism, a political philosophy in support of social reform

** Progressivism in the United States, the political philosophy in the American context

* Progressive realism, an American foreign policy par ...

and -''toru'' in perfect

Perfect commonly refers to:

* Perfection, completeness, excellence

* Perfect (grammar), a grammatical category in some languages

Perfect may also refer to:

Film

* Perfect (1985 film), ''Perfect'' (1985 film), a romantic drama

* Perfect (2018 f ...

. In Kansai, some dialects of southern Hyogo and Kii Peninsula have these discrimination, too. In parts of Wakayama, -''yoru'' and -''toru'' are replaced with -''yaru'' and -''taaru/chaaru''.

Politeness

Historically, extensive use of keigo (honorific speech) was a feature of the Kansai dialect, especially in Kyōto, while the Kantō dialect, from which standard Japanese developed, formerly lacked it. Keigo in standard Japanese was originally borrowed from the medieval Kansai dialect. However, keigo is no longer considered a feature of the dialect since Standard Japanese now also has it. Even today, keigo is used more often in Kansai than in the other dialects except for the standard Japanese, to which people switch in formal situations.

In modern Kansai dialect, -''haru'' (sometimes -''yaharu'' except ''godan'' verbs, mainly Kyōto) is used for showing reasonable respect without formality especially in Kyōto. The conjugation before -''haru'' has two varieties between Kyōto and Ōsaka (see the table below). In Southern Hyōgo, including Kōbe, ''-te ya'' is used instead of -''haru''. In formal speech, -''naharu'' and -''haru'' connect with -''masu'' and -''te ya'' changes -''te desu''.

-''Haru'' was originally a shortened form of -''naharu'', a transformation of -''nasaru''. -''Naharu'' has been dying out due to the spread of -''haru'' but its imperative form -''nahare'' (mainly Ōsaka) or -''nahai'' (mainly Kyōto, also -''nai'') and negative imperative form -''nasan'na'' or -''nahan'na'' has comparatively survived because -''haru'' lacks an imperative form. In more honorific speech, ''o- yasu'', a transformation of ''o- asobasu'', is used especially in Kyōto and its original form is same to its imperative form, showing polite invitation or order. ''Oide yasu'' and ''okoshi yasu'' (more respectful), meaning "welcome", are the common phrases of sightseeing areas in Kyōto. -''Te okun nahare'' (also -''tokun nahare'', -''toku nahare'') and -''te okure yasu'' (also -''tokure yasu'', -''tokuryasu'') are used instead of -''te kudasai'' in standard Japanese.

Historically, extensive use of keigo (honorific speech) was a feature of the Kansai dialect, especially in Kyōto, while the Kantō dialect, from which standard Japanese developed, formerly lacked it. Keigo in standard Japanese was originally borrowed from the medieval Kansai dialect. However, keigo is no longer considered a feature of the dialect since Standard Japanese now also has it. Even today, keigo is used more often in Kansai than in the other dialects except for the standard Japanese, to which people switch in formal situations.

In modern Kansai dialect, -''haru'' (sometimes -''yaharu'' except ''godan'' verbs, mainly Kyōto) is used for showing reasonable respect without formality especially in Kyōto. The conjugation before -''haru'' has two varieties between Kyōto and Ōsaka (see the table below). In Southern Hyōgo, including Kōbe, ''-te ya'' is used instead of -''haru''. In formal speech, -''naharu'' and -''haru'' connect with -''masu'' and -''te ya'' changes -''te desu''.

-''Haru'' was originally a shortened form of -''naharu'', a transformation of -''nasaru''. -''Naharu'' has been dying out due to the spread of -''haru'' but its imperative form -''nahare'' (mainly Ōsaka) or -''nahai'' (mainly Kyōto, also -''nai'') and negative imperative form -''nasan'na'' or -''nahan'na'' has comparatively survived because -''haru'' lacks an imperative form. In more honorific speech, ''o- yasu'', a transformation of ''o- asobasu'', is used especially in Kyōto and its original form is same to its imperative form, showing polite invitation or order. ''Oide yasu'' and ''okoshi yasu'' (more respectful), meaning "welcome", are the common phrases of sightseeing areas in Kyōto. -''Te okun nahare'' (also -''tokun nahare'', -''toku nahare'') and -''te okure yasu'' (also -''tokure yasu'', -''tokuryasu'') are used instead of -''te kudasai'' in standard Japanese.

Particles

There is some difference in the particles between Kansai dialect and standard Japanese. In colloquial Kansai dialect, are often left out especially theaccusative case

The accusative case (abbreviated ) of a noun is the grammatical case used to mark the direct object of a transitive verb.

In the English language, the only words that occur in the accusative case are pronouns: 'me,' 'him,' 'her,' 'us,' and ‘the ...

''o'' and the quotation particles ''to'' and ''te'' (equivalent to ''tte'' in standard). The ellipsis of ''to'' and ''te'' happens only before two verbs: ''yū'' (to say) and ''omou'' (to think). For example, ''Tanaka-san to yū hito'' ("a man called Mr. Tanaka") can change to ''Tanaka-san yū hito''. And ''to yū'' is sometimes contracted to ''chū'' or ''tchū'' instead of ''te'', ''tsū'' or ''ttsū'' in Tokyo. For example, ''nanto yū koto da!'' or ''nante kotta!'' ("My goodness!") becomes ''nanchū kotcha!'' in Kansai.

The ''na'' or ''naa'' is used very often in Kansai dialect instead of ''ne'' or ''nee'' in standard Japanese. In standard Japanese, ''naa'' is considered rough masculine style in some context, but in Kansai dialect ''naa'' is used by both men and women in many familiar situations. It is not only used as interjectory particle (as emphasis for the imperative form, expression an admiration, and address to listeners, for example), and the meaning varies depending on context and voice intonation, so much so that ''naa'' is called the world's third most difficult word to translate. Besides ''naa'' and ''nee'', ''noo'' is also used in some areas, but ''noo'' is usually considered too harsh a masculine particle in modern Keihanshin.

''Kara'' and ''node'', the meaning "because," are replaced by ''sakai'' or ''yotte''; ''ni'' is sometimes added to the end of both, and ''sakai'' changes to ''sake'' in some areas. ''Sakai'' was so famous as the characteristic particle of Kansai dialect that a special saying was made out of it: ". However, in recent years, the standard ''kara'' and ''node'' have become dominant.

''Kate'' or ''katte'' is also characteristic particle of Kansai dialect, transformation of ''ka tote''. ''Kate'' has two usages. When ''kate'' is used with conjugative words, mainly in the past form and the negative form, it is the equivalent of the English "even if" or "even though", such as ''Kaze hiita kate, watashi wa ryokō e iku'' ("Even if catch a cold, I will go on the trip"). When ''kate'' is used with nouns, it means something like "even", "too," or "either", such as ''Ore kate shiran'' ("I don't know, either"), and is similar to the particle ''mo'' and ''datte''.

Sentence final particles

The used in Kansai differ widely from those used in Tokyo. The most prominent to Tokyo speakers is the heavy use of ''wa'' by men. In standard Japanese, it is used exclusively by women and so is said to sound softer. In western Japanese including Kansai dialect, however, it is used equally by both men and women in many different levels of conversation. It is noted that the feminine usage of ''wa'' in Tokyo is pronounced with a rising intonation and the Kansai usage of ''wa'' is pronounced with a falling intonation. Another difference in sentence final particles that strikes the ear of the Tokyo speaker is the ''nen'' particle such as ''nande ya nen!'', "you gotta be kidding!" or "why/what the hell?!", a stereotype tsukkomi phrase in the manzai. It comes from ''no ya'' (particle ''no'' + copula ''ya'', also ''n ya'') and much the same as the standard Japanese ''no da'' (also ''n da''). ''Nen'' has some variation, such as ''neya'' (intermediate form between ''no ya'' and ''nen''), ''ne'' (shortened form), and ''nya'' (softer form of ''neya''). When a copula precedes these particles, ''da'' + ''no da'' changes to ''na no da'' (''na n da'') and ''ya'' + ''no ya'' changes to ''na no ya'' (''na n ya''), but ''ya'' + ''nen'' does not change to ''na nen''. ''No da'' is never used with polite form, but ''no ya'' and ''nen'' can be used with formal form such as ''nande desu nen'', a formal form of ''nande ya nen''. In past tense, ''nen'' changes to ''-ten''; for example, "I love you" would be ''suki ya nen'' or ''sukkya nen'', and "I loved you" would be ''suki yatten.'' In the interrogative sentence, the use of ''nen'' and ''no ya'' is restricted to emphatic questions and involvesinterrogative word

An interrogative word or question word is a function word used to ask a question, such as ''what, which'', ''when'', ''where'', ''who, whom, whose'', ''why'', ''whether'' and ''how''. They are sometimes called wh-words, because in English most o ...

s. For simple questions, ''(no) ka'' is usually used and ''ka'' is often omitted as well as standard Japanese, but ''no'' is often changed ''n'' or ''non'' (somewhat feminine) in Kansai dialect. In standard Japanese, ''kai'' is generally used as a masculine variation of ''ka'', but in Kansai dialect, ''kai'' is used as an emotional question and is mainly used for rhetorical question rather than simple question and is often used in the forms as ''kaina'' (softer) and ''kaiya'' (harsher). When ''kai'' follows the negative verb ending -''n'', it means strong imperative sentence. In some areas such as Kawachi and Banshu, ''ke'' is used instead of ''ka'', but it is considered a harsh masculine particle in common Kansai dialect.

The emphatic particle ''ze'', heard often from Tokyo men, is rarely heard in Kansai. Instead, the particle ''de'' is used, arising from the replacement of ''z'' with ''d'' in words. However, despite the similarity with ''ze'', the Kansai ''de'' does not carry nearly as heavy or rude a connotation, as it is influenced by the lesser stress on formality and distance in Kansai. In Kyoto, especially feminine speech, ''de'' is sometimes replaced with ''e''. The particle ''zo'' is also replaced to ''do'' by some Kansai speakers, but ''do'' carries a rude masculine impression unlike ''de''.

The emphasis or tag question particle ''jan ka'' in the casual speech of Kanto changes to ''yan ka'' in Kansai. ''Yan ka'' has some variations, such as a masculine variation ''yan ke'' (in some areas, but ''yan ke'' is also used by women) and a shortened variation ''yan'', just like ''jan'' in Kanto. ''Jan ka'' and ''jan'' are used only in informal speech, but ''yan ka'' and ''yan'' can be used with formal forms like ''sugoi desu yan!'' ("It is great!"). Youngsters often use ''yan naa'', the combination of ''yan'' and ''naa'' for tag question.

Vocabulary

Well-known words

Here are some words and phrases famous as part of the Kansai dialect:Pronouns and honorifics

Standard first-person pronouns such as ''watashi'', ''boku'' and ''ore'' are also generally used in Kansai, but there are some local pronoun words. ''Watashi'' has many variations: ''watai'', ''wate'' (both gender), ''ate'' (somewhat feminine), and ''wai'' (masculine, casual). These variations are now archaic, but are still widely used in fictitious creations to represent stereotypical Kansai speakers especially ''wate'' and ''wai''. Elderly Kansai men frequent use ''washi'' as well as other western Japan. ''Uchi'' is famous for the typical feminine first-person pronoun of Kansai dialect and it is still popular among Kansai girls. In Kansai, ''omae'' and ''anta'' are often used for the informal second-person pronoun. ''Anata'' is hardly used. Traditional local second-person pronouns include ''omahan'' (''omae'' + ''-han''), ''anta-han'' and ''ansan'' (both are ''anta'' + ''-san'', but ''anta-han'' is more polite). An archaic first-person pronoun, ''ware'', is used as a hostile and impolite second-person pronoun in Kansai. ''Jibun'' () is a Japanese word meaning "oneself" and sometimes "I," but it has an additional usage in Kansai as a casual second-person pronoun. In traditional Kansai dialect, the honorific suffix ''-san'' is sometimes pronounced -''han'' when -''san'' follows ''a'', ''e'' and ''o''; for example, ''okaasan'' ("mother") becomes ''okaahan'', and ''Satō-san'' ("Mr. Satō") becomes ''Satō-han''. It is also the characteristic of Kansai usage of honorific suffixes that they can be used for some familiar inanimate objects as well, especially in Kyoto. In standard Japanese, the usage is usually considered childish, but in Kansai, ''o-imo

IMO or Imo may refer to:

Biology and medicine

* Irish Medical Organisation, the main organization for doctors in the Republic of Ireland

* Intelligent Medical Objects, a privately held company specializing in medical vocabularies

* Isomaltooligos ...

-san'', ''o- mame-san'' and '' ame-chan'' are often heard not only in children's speech but also in adults' speech. The suffix ''-san'' is also added to some familiar greeting phrases; for example, ''ohayō-san'' ("good morning") and ''omedetō-san'' ("congratulations").

Regional differences

Since Kansai dialect is actually a group of related dialects, not all share the same vocabulary, pronunciation, or grammatical features. Each dialect has its own specific features discussed individually here. Here is a division theory of Kansai dialects proposed by Mitsuo Okumura in 1968; ■ shows dialects influenced by Kyoto dialect and □ shows dialects influenced by Osaka dialect, proposed by Minoru Umegaki in 1962.

* Inner Kansai dialect

** ■Kyoto dialect (southern part of Kyoto Prefecture, especially the city of Kyoto)

*** Gosho dialect (old court dialect of Kyoto Gosho)

*** Machikata dialect (Kyoto citizens' dialect including several social dialects)

*** Tanba dialect (southeastern part of former Tanba Province)

*** Southern Yamashiro dialect (southern part of former Yamashiro Province)

** □Osaka dialect (

Here is a division theory of Kansai dialects proposed by Mitsuo Okumura in 1968; ■ shows dialects influenced by Kyoto dialect and □ shows dialects influenced by Osaka dialect, proposed by Minoru Umegaki in 1962.

* Inner Kansai dialect

** ■Kyoto dialect (southern part of Kyoto Prefecture, especially the city of Kyoto)

*** Gosho dialect (old court dialect of Kyoto Gosho)

*** Machikata dialect (Kyoto citizens' dialect including several social dialects)

*** Tanba dialect (southeastern part of former Tanba Province)

*** Southern Yamashiro dialect (southern part of former Yamashiro Province)

** □Osaka dialect (Osaka Prefecture

is a Prefectures of Japan, prefecture of Japan located in the Kansai region of Honshu. Osaka Prefecture has a population of 8,778,035 () and has a geographic area of . Osaka Prefecture borders Hyōgo Prefecture to the northwest, Kyoto Prefecture ...

, especially the city of Osaka)

*** Settsu dialect (Northern part of Osaka Prefecture, former Settsu Province)

**** Senba dialect (old merchant dialect in the central area of the city of Osaka)

*** Kawachi dialect (eastern part of Osaka Prefecture, former Kawachi Province

was a province of Japan in the eastern part of modern Osaka Prefecture. It originally held the southwestern area that was split off into Izumi Province. It was also known as .

Geography

The area was radically different in the past, with Kawachi ...

)

*** Senshū dialect (southwestern part of Osaka Prefecture, former Izumi Province)

** □Kobe dialect (the city of Kobe

Kobe ( , ; officially , ) is the capital city of Hyōgo Prefecture Japan. With a population around 1.5 million, Kobe is Japan's seventh-largest city and the third-largest port city after Tokyo and Yokohama. It is located in Kansai region, whic ...

, Hyōgo Prefecture

is a prefecture of Japan located in the Kansai region of Honshu. Hyōgo Prefecture has a population of 5,469,762 () and has a geographic area of . Hyōgo Prefecture borders Kyoto Prefecture to the east, Osaka Prefecture to the southeast, an ...

)

** □Northern Nara dialect (northern part of Nara Prefecture)

** ■Shiga dialect (main part of Shiga Prefecture)

** ■Iga dialect (northwestern part of Mie Prefecture, former Iga Province

was a province of Japan located in what is today part of western Mie Prefecture. Nussbaum, Louis-Frédéric. (2005). "Iga" in . Its abbreviated name was . Iga is classified as one of the provinces of the Tōkaidō. Under the ''Engishiki'' cl ...

)

* Outer Kansai dialect

** Northern Kansai dialect

*** ■Tanba dialect (northern part of former Tanba Province and Maizuru)

*** ■Southern Fukui dialect (southern part of Fukui Prefecture, former Wakasa Province and Tsuruga

is a city located in Fukui Prefecture, Japan. , the city had an estimated population of 66,123 in 28,604 households and the population density of 260 persons per km2. The total area of the city was .

Geography

Tsuruga is located in central ...

)

*** ■Kohoku dialect (northeastern part of Shiga Prefecture)

** Western Kansai dialect

*** □Banshū dialect (southwestern part of Hyōgo Prefecture, former Harima Province

or Banshū (播州) was a province of Japan in the part of Honshū that is the southwestern part of present-day Hyōgo Prefecture. Harima bordered on Tajima, Tanba, Settsu, Bizen, and Mimasaka Provinces. Its capital was Himeji.

During the ...

)

*** ■Tanba dialect (southwestern part of former Tanba Province)

** Eastern Kansai dialect

*** ■Ise dialect (northern part of Mie Prefecture, former Ise Province)

** Southern Kansai dialect

*** Kishū dialect ( Wakayama Prefecture and southern part of Mie Prefecture, former Kii Province)

*** Shima dialect (southeastern part of Mie Prefecture, former Shima Province

was a Provinces of Japan, province of Japan which consisted of a peninsula in the southeastern part of modern Mie Prefecture.Louis-Frédéric, Nussbaum, Louis-Frédéric. (2005). "''Shima''" in . Its abbreviated name was . Shima bordered on Ise ...

)

*** □ Awaji dialect ( Awaji Island in Hyōgo Prefecture)

* Totsukawa-Kumano dialect (southern part of Yoshino and Owase

is a city located in Mie Prefecture, Japan. , the city had an estimated population of 16,910 in 9177 households and a population density of 88 persons per km2. The total area of the city was .

Geography

Owase is located in southeastern Kii Peni ...

- Kumano area in southeastern Kii Peninsula)

Osaka

Osaka-ben ( 大阪弁) is often identified with Kansai dialect by most Japanese, but some of the terms considered to be characteristic of Kansai dialect are actually restricted to Osaka and its environs. Perhaps the most famous is the term ''mōkarimakka?'', roughly translated as "how is business?", and derived from the verb ''mōkaru'' (儲かる), "to be profitable, to yield a profit". This is supposedly said as a greeting from one Osakan to another, and the appropriate answer is another Osaka phrase, ''maa, bochi bochi denna'' "well, so-so, y'know". The idea behind ''mōkarimakka'' is that Osaka was historically the center of the merchant culture. The phrase developed among low-class shopkeepers and can be used today to greet a business proprietor in a friendly and familiar way but is not a universal greeting. The latter phrase is also specific to Osaka, in particular the term ''bochi bochi'' (L-L-H-L). This means essentially "so-so": getting better little by little or not getting any worse. Unlike ''mōkarimakka'', ''bochi bochi'' is used in many situations to indicate gradual improvement or lack of negative change. Also, ''bochi bochi'' (H-L-L-L) can be used in place of the standard Japanese ''soro soro'', for instance ''bochi bochi iko ka'' "it is about time to be going". In the Edo period, Senba-kotoba (船場言葉), a social dialect of the wealthy merchants in thecentral business district

A central business district (CBD) is the commercial and business centre of a city. It contains commercial space and offices, and in larger cities will often be described as a financial district. Geographically, it often coincides with the "city ...

of Osaka, was considered the standard Osaka-ben. It was characterized by the polite speech based on Kyoto-ben and the subtle differences depending on the business type, class, post etc. It was handed down in Meiji, Taishō and Shōwa periods with some changes, but after the Pacific War

The Pacific War, sometimes called the Asia–Pacific War, was the theater of World War II that was fought in Asia, the Pacific Ocean, the Indian Ocean, and Oceania. It was geographically the largest theater of the war, including the vast ...

, Senba-kotoba became nearly an obsolete dialect due to the modernization of business practices. Senba-kotoba was famous for a polite copula ''gowasu'' or ''goasu'' instead of common Osakan copula ''omasu'' and characteristic forms for shopkeeper family mentioned below.

Southern branches of Osaka-ben, such as Senshū-ben ( 泉州弁) and Kawachi-ben ( 河内弁), are famous for their harsh locution, characterized by trilled "r", the question particle ''ke'', and the second person ''ware''. The farther south in Osaka one goes, the cruder the language is considered to be, with the local Senshū-ben of Kishiwada said to represent the peak of harshness.

Kyoto

geiko

{{Culture of Japan, Traditions, Geisha

{{nihongo, Geisha, 芸者 ({{IPAc-en, ˈ, ɡ, eɪ, ʃ, ə; {{IPA-ja, ɡeːɕa, lang), also known as {{nihongo, , 芸子, geiko (in Kyoto and Kanazawa) or {{nihongo, , 芸妓, geigi, are a class of female J ...

at Hanamachi ( Gion, Miyagawa-chō etc.)

Kyoto-ben was the ''de facto'' standard Japanese from 794 until the 18th century and some Kyoto people are still proud of their accent; they get angry when Tokyo people treat Kyoto-ben as a provincial accent. However, traditional Kyoto-ben is gradually declining except in the world of ''geisha'', which prizes the inheritance of traditional Kyoto customs. For example, a famous Kyoto copula ''dosu'', instead of standard ''desu'', is used by a few elders and ''geisha'' now.

The verb inflection ''-haru'' is an essential part of casual speech in modern Kyoto. In Osaka and its environs, ''-haru'' has a certain level of politeness above the base (informal) form of the verb, putting it somewhere between the informal and the more polite ''-masu'' conjugations. However, in Kyoto, its position is much closer to the informal than it is to the polite mood, owing to its widespread use. Kyoto people, especially elderly women, often use -''haru'' for their family and even for animals and weather.

Tango-ben ( 丹後弁) spoken in northernmost Kyoto Prefecture, is too different to be regarded as Kansai dialect and usually included in Chūgoku dialect. For example, the copula ''da'', the Tokyo-type accent, the honorific verb ending -''naru'' instead of -''haru'' and the peculiarly diphthong such as for ''akai'' "red".

Hyogo

Hyōgo Prefecture

is a prefecture of Japan located in the Kansai region of Honshu. Hyōgo Prefecture has a population of 5,469,762 () and has a geographic area of . Hyōgo Prefecture borders Kyoto Prefecture to the east, Osaka Prefecture to the southeast, an ...

is the largest prefecture in Kansai, and there are some different dialects in the prefecture. As mentioned above, Tajima-ben ( 但馬弁) spoken in northern Hyōgo, former Tajima Province, is included in Chūgoku dialect as well as Tango-ben. Ancient vowel sequence /au/ changed in many Japanese dialects, but in Tajima, Tottori and Izumo dialects, /au/ changed . Accordingly, Kansai word ''ahō'' "idiot" is pronounced ''ahaa'' in Tajima-ben.

The dialect spoken in southwestern Hyōgo, former Harima Province

or Banshū (播州) was a province of Japan in the part of Honshū that is the southwestern part of present-day Hyōgo Prefecture. Harima bordered on Tajima, Tanba, Settsu, Bizen, and Mimasaka Provinces. Its capital was Himeji.

During the ...

alias Banshū, is called Banshū-ben. As well as Chūgoku dialect, it has the discrimination of aspect, ''-yoru'' in progressive and ''-toru'' in perfect. Banshū-ben is notable for transformation of ''-yoru'' and ''-toru'' into ''-yō'' and ''-tō'', sometimes ''-yon'' and ''-ton''. Another feature is the honorific copula ''-te ya'', common in Tanba, Maizuru and San'yō dialects. In addition, Banshū-ben is famous for an emphatic final particle ''doi'' or ''doiya'' and a question particle ''ke'' or ''ko'', but they often sound violent to other Kansai speakers, as well as Kawachi-ben. Kōbe-ben ( 神戸弁) spoken in Kobe

Kobe ( , ; officially , ) is the capital city of Hyōgo Prefecture Japan. With a population around 1.5 million, Kobe is Japan's seventh-largest city and the third-largest port city after Tokyo and Yokohama. It is located in Kansai region, whic ...

, the largest city of Hyogo, is the intermediate dialect between Banshū-ben and Osaka-ben and is well known for conjugating ''-yō'' and ''-tō'' as well as Banshū-ben.

Awaji-ben ( 淡路弁) spoken in Awaji Island, is different from Banshū/Kōbe-ben and mixed with dialects of Osaka, Wakayama and Tokushima Prefecture

is a prefecture of Japan located on the island of Shikoku. Tokushima Prefecture has a population of 728,633 (1 October 2019) and has a geographic area of 4,146 km2 (1,601 sq mi). Tokushima Prefecture borders Kagawa Prefecture to the north, E ...

s due to the intersecting location of sea routes in the Seto Inland Sea

The , sometimes shortened to the Inland Sea, is the body of water separating Honshū, Shikoku, and Kyūshū, three of the four main islands of Japan. It serves as a waterway connecting the Pacific Ocean to the Sea of Japan. It connects to Osaka ...

and the Tokushima Domain rule in Edo period.

Mie

The dialect in Mie Prefecture, sometimes called Mie-ben ( 三重弁), is made up of Ise-ben ( 伊勢弁) spoken in mid-northern Mie, Shima-ben ( 志摩弁) spoken in southeastern Mie andIga Iga may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* Ambush at Iga Pass, a 1958 Japanese film

* Iga no Kagemaru, Japanese manga series

* Iga, a set of characters from the Japanese novel '' The Kouga Ninja Scrolls''

Biology

* ''Iga'' (beetle), a gen ...

-ben ( 伊賀弁) spoken in western Mie. Ise-ben is famous for a sentence final particle ''ni'' as well as ''de''. Shima-ben is close to Ise-ben, but its vocabulary includes many archaic words. Iga-ben has a unique request expression ''-te daako'' instead of standard ''-te kudasai''.

They use the normal Kansai accent and basic grammar, but some of the vocabulary is common to the Nagoya dialect. For example, instead of -''te haru'' (respectful suffix), they have the Nagoya-style -''te mieru''. Conjunctive particles ''de'' and ''monde'' "because" is widely used instead of ''sakai'' and ''yotte''. The similarity to Nagoya-ben becomes more pronounced in the northernmost parts of the prefecture; the dialect of Nagashima and Kisosaki, for instance, could be considered far closer to Nagoya-ben than to Ise-ben.

In and around Ise city

, formerly called Ujiyamada (宇治山田), is a city in central Mie Prefecture, on the island of Honshū, Japan. Ise is home to Ise Grand Shrine, the most sacred Shintō shrine in Japan. The city has a long-standing title – Shinto (神都) � ...

, some variations on typical Kansai vocabulary can be found, mostly used by older residents. For instance, the typical expression ''ōkini'' is sometimes pronounced ''ōkina'' in Ise. Near the Isuzu River and Naikū shrine, some old men use the first-person pronoun ''otai''.

Wakayama

Kishū-ben ( 紀州弁) or Wakayama-ben (和歌山弁), the dialect in old province Kii Province, present-day Wakayama Prefecture and southern parts of Mie Prefecture, is fairly different from common Kansai dialect and comprises many regional variants. It is famous for heavy confusion of ''z'' and ''d'', especially on the southern coast. The ichidan verb negative form ''-n'' often changes ''-ran'' in Wakayama such as ''taberan'' instead of ''taben'' ("not eat"); ''-hen'' also changes ''-yan'' in Wakayama, Mie and Nara such as ''tabeyan'' instead of ''tabehen''. Wakayama-ben has specific perticles. ''Yō'' is often used as sentence final particle. ''Ra'' follows the volitional conjugation of verbs as ''iko ra yō!'' ("Let's go!"). ''Noshi'' is used as soft sentence final particle. ''Yashite'' is used as tag question. Local words are ''akana'' instead of ''akan'', ''omoshai'' instead of ''omoroi'', ''aga'' "oneself", ''teki'' "you", ''tsuremote'' "together" and so on. Wakayama people hardly ever use keigo, which is rather unusual for dialects in Kansai.Shiga

Shiga Prefecture is the eastern neighbor of Kyoto, so its dialect, sometimes called Shiga-ben (滋賀弁) or Ōmi-ben ( 近江弁) or Gōshū-ben (江州弁), is similar in many ways to Kyoto-ben. For example, Shiga people also frequently use ''-haru'', though some people tend to pronounce ''-aru'' and ''-te yaaru'' instead of ''-haru'' and ''-te yaharu''. Some elderly Shiga people also use ''-raru'' as a casual honorific form. The demonstrative pronoun ''so-'' often changes to ''ho-''; for example, ''so ya'' becomes ''ho ya'' and ''sore'' (that) becomes ''hore''. In Nagahama, people use the friendly-sounding auxiliary verb ''-ansu'' and ''-te yansu''. Nagahama and Hikone dialects has a unique final particle ''hon'' as well as ''de''.Nara

The dialect in Nara Prefecture is divided into northern including Nara city and southern including Totsukawa. The northern dialect, sometimes called Nara-ben ( 奈良弁) or Yamato-ben (大和弁), has a few particularities such as an interjectory particle ''mii'' as well as ''naa'', but the similarity with Osaka-ben increases year by year because of the economic dependency to Osaka. On the other hand, southern Nara prefecture is a language island because of its geographic isolation with mountains. The southern dialect uses Tokyo type accent, has the discrimination of grammatical aspect, and does not show a tendency to lengthen vowels at the end of monomoraic nouns.Example

An example of Kyoto women's conversation recorded in 1964See also

Kansai dialect in Japanese culture

* Bunraku - a traditional puppet theatre played in the early modern Osaka dialect * Kabuki - Kamigata style kabuki is played in Kansai dialect *Rakugo

is a form of ''yose'', which is itself a form of Japanese verbal entertainment. The lone sits on a raised platform, a . Using only a and a as props, and without standing up from the seiza sitting position, the rakugo artist depicts a long ...

- Kamigata style rakugo is played in Kansai dialect

* Mizuna - ''mizuna'' is originally a Kansai word for Kanto word ''kyōna''

* Shichimi - ''shichimi'' is originally a Kansai word for Kanto word ''nanairo''

* Tenkasu - ''tenkasu'' is originally a Kansai word for Kanto word ''agedama''

* Hamachi - ''hamachi'' is originally a Kansai word for Kanto word ''inada''

Related dialects

* Hokuriku dialect * Shikoku dialect * Mino dialectReferences

Notes

Bibliography

For non-Japanese speakers, learning environment of Kansai dialect is richer than other dialects. * Palter, DC and Slotsve, Kaoru Horiuchi (1995). ''Colloquial Kansai Japanese: The Dialects and Culture of the Kansai Region''. Boston: Charles E. Tuttle Publishing. . ** ** * Tse, Peter (1993). ''Kansai Japanese: The language of Osaka, Kyoto, and western Japan''. Boston: Charles E. Tuttle Publishing. . ** * Takahashi, Hiroshi and Kyoko (1995). ''How to speak Osaka Dialect''. Kobe: Taiseido Shobo Co. Ltd. * Minoru Umegaki (Ed.) (1962). . Tokyo: Sanseido. * Isamu Maeda (1965). . Tokyo: Tokyodo Publishing. * Kiichi Iitoyo, Sukezumi Hino, Ryōichi Satō (Ed.) (1982). . Tokyo: Kokushokankōkai * Shinji Sanada, Makiko Okamoto, Yoko Ujihara (2006). . Tokyo: Hituzi Syobo Publishing. .External links

Kansai Dialect Self-study Site for Japanese Language Learner

The Corpus of Kansai Vernacular Japanese

- nihongoresources.com

Kansai Ben

- TheJapanesePage.com

- Kansai-ben texts and videos made by Ritsumeikan University students

Osaka-ben Study Website

- U-biq

- Osaka city {{DEFAULTSORT:Kansai Dialect Japanese dialects Kansai region