Joseph Swetnam on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Joseph Swetnam (died 1621) was an English

, The Arraignment of Women His borrowing of authority from Biblical figures was far more powerful and inflammatory, especially in Protestant England. Most material in attacks on women and in their defence was taken from the Bible, by all writers engaged in the debate. An important part of any author's attack or defence of women (as well as other subjects of debate) was interpretation and counter-interpretation of the Bible to support his or her perspective.Book

Half Humankind Swetnam draws somewhat from the much-debated scene of the

Three female writers responded independently to Swetnam's work, in defence of their gender. The first response was by

Three female writers responded independently to Swetnam's work, in defence of their gender. The first response was by

In his 1617

In his 1617

Swetnam, Joseph (d. 1621)

, ''

Half Humankind: Contexts and Texts of the Controversy about Women in England 1540–1640

Half Humankind, a book about the Pamphlet Wars in England, among other things.

a transcription of the practical sections of Swetnam's fencing manual.

The Schoole of the Noble and Worthy Science of Defence – Complete, PDF

a complete facsimile scan of the fencing manual.

A short video introduction to Swetnam's rapier fencing systemA short video examining Swetnam's claims that he could lunge 12 feet

{{DEFAULTSORT:Swetnam, Joseph 17th-century English writers 17th-century English male writers Year of birth unknown Year of death unknown Historical European martial arts English male writers

pamphleteer

Pamphleteer is a historical term for someone who creates or distributes pamphlets, unbound (and therefore inexpensive) booklets intended for wide circulation.

Context

Pamphlets were used to broadcast the writer's opinions: to articulate a polit ...

and fencing

Fencing is a group of three related combat sports. The three disciplines in modern fencing are the foil, the épée, and the sabre (also ''saber''); winning points are made through the weapon's contact with an opponent. A fourth discipline ...

master. He is best known for a misogynistic

Misogyny () is hatred of, contempt for, or prejudice against women. It is a form of sexism that is used to keep women at a lower social status than men, thus maintaining the societal roles of patriarchy. Misogyny has been widely practiced ...

pamphlet

A pamphlet is an unbound book (that is, without a hard cover or binding). Pamphlets may consist of a single sheet of paper that is printed on both sides and folded in half, in thirds, or in fourths, called a ''leaflet'' or it may consist of a ...

and an early English fencing treatise. Three defensive responses as pamphlets were made by Rachel Speght

Rachel Speght (1597 – death date unknown) was a poet and polemicist. She was the first Englishwoman to identify herself, by name, as a polemicist and critic of gender ideology. Speght, a feminist and a Calvinist, is perhaps best known for her tr ...

, Ester Sowernam and Constantia Munda.

The Pamphlet Wars

Swetnam's pamphlet attacking women was one of the most influential of the era.''The Arraignment of Women'' (1615)

''The arraignment of lewd, idle, froward, and unconstant women'' was published in 1615 under the pseudonym Thomas Tell-Troth. Despite this attempt at anonymity, Swetnam was quickly known as the true author. (The full title of the original pamphlet was: ) Swetnam describes in this document what he views as the sinful, deceiving, worthless nature of women. He addresses his remarks to young men of the world, as if warning them about the dangers of womankind. He cites personal experiences as well as those of well-knownbiblical

The Bible (from Koine Greek , , 'the books') is a collection of religious texts or scriptures that are held to be sacred in Christianity, Judaism, Samaritanism, and many other religions. The Bible is an anthologya compilation of texts of a ...

and classical figures to authenticate his claims. Obviously intended for a male audience, much of the pamphlet takes the comical form of what we might today call sexist jokes. For example, Swetnam writes, "A gentleman on a time said to his friend, 'I can help you to a good marriage for your son.' His friend made him this answer: 'My son,' said he, 'shall stay till he have more wit.' The Gentleman replied again, saying, 'If you marry him not before he has wit, he will never marry so long as he lives.'"Pamphlet, The Arraignment of Women His borrowing of authority from Biblical figures was far more powerful and inflammatory, especially in Protestant England. Most material in attacks on women and in their defence was taken from the Bible, by all writers engaged in the debate. An important part of any author's attack or defence of women (as well as other subjects of debate) was interpretation and counter-interpretation of the Bible to support his or her perspective.Book

Half Humankind Swetnam draws somewhat from the much-debated scene of the

Garden of Eden

In Abrahamic religions, the Garden of Eden ( he, גַּן־עֵדֶן, ) or Garden of God (, and גַן־אֱלֹהִים ''gan-Elohim''), also called the Terrestrial Paradise, is the biblical paradise described in Genesis 2-3 and Ezekiel 28 an ...

, saying that woman "was no sooner made but straightway...procured man's fall", but he spends more time naming various victims of seduction, including David

David (; , "beloved one") (traditional spelling), , ''Dāwūd''; grc-koi, Δαυΐδ, Dauíd; la, Davidus, David; gez , ዳዊት, ''Dawit''; xcl, Դաւիթ, ''Dawitʿ''; cu, Давíдъ, ''Davidŭ''; possibly meaning "beloved one". w ...

, Solomon

Solomon (; , ),, ; ar, سُلَيْمَان, ', , ; el, Σολομών, ; la, Salomon also called Jedidiah ( Hebrew: , Modern: , Tiberian: ''Yăḏīḏăyāh'', "beloved of Yah"), was a monarch of ancient Israel and the son and succe ...

, and Samson

Samson (; , '' he, Šīmšōn, label= none'', "man of the sun") was the last of the judges of the ancient Israelites mentioned in the Book of Judges (chapters 13 to 16) and one of the last leaders who "judged" Israel before the institution ...

, blaming their falls from Godly grace on the wiles of the women with whom they sinned. He even makes use of a number of legendary figures in classical antiquity

Classical antiquity (also the classical era, classical period or classical age) is the period of cultural history between the 8th century BC and the 5th century AD centred on the Mediterranean Sea, comprising the interlocking civilizations o ...

, including Hercules

Hercules (, ) is the Roman equivalent of the Greek divine hero Heracles, son of Jupiter and the mortal Alcmena. In classical mythology, Hercules is famous for his strength and for his numerous far-ranging adventures.

The Romans adapted the Gr ...

, Agamemnon

In Greek mythology, Agamemnon (; grc-gre, Ἀγαμέμνων ''Agamémnōn'') was a king of Mycenae who commanded the Greeks during the Trojan War. He was the son, or grandson, of King Atreus and Queen Aerope, the brother of Menelaus, the hus ...

, and Ulysses, citing the travails they suffered at the hands of women. While citing scriptural examples lends religious authority to his claims, using classical examples, even those from a mythology deemed false by Christian beliefs, appeals to the sense of antiquity and cultural superiority associated with Rome.

''The Arraignment of Women'' was extremely popular—there were thirteen "known reprints" in the 17th century and another five in the early 18th century; it was even translated into Dutch

Dutch commonly refers to:

* Something of, from, or related to the Netherlands

* Dutch people ()

* Dutch language ()

Dutch may also refer to:

Places

* Dutch, West Virginia, a community in the United States

* Pennsylvania Dutch Country

People ...

as ''Recht-Banck tegen de Luye, Korzelighe, en Wispeltuyrighe Vrouwen'' in 1641 (to be reprinted four times in the 17th century, with two further editions in the early 18th). Some scholars propose that this popularity was due to its heavy drawing from previous works, including and especially John Lyly

John Lyly (; c. 1553 or 1554 – November 1606; also spelled ''Lilly'', ''Lylie'', ''Lylly'') was an English writer, dramatist of the University Wits, courtier, and parliamentarian. He was best known during his lifetime for his two books '' E ...

's Euphues

''Euphues: The Anatomy of Wit'' , a didactic romance written by John Lyly, was entered in the Stationers' Register 2 December 1578 and published that same year. It was followed by ''Euphues and his England'', registered on 25 July 1579, but not p ...

, and its consequent sense of inclusiveness. Others suppose it could have been its decisively middle-class emphasis and humor. It is also possible that it became popular because of the reaction it sparked from other writers, which seems to be its most distinguishing characteristic.

Response

Three female writers responded independently to Swetnam's work, in defence of their gender. The first response was by

Three female writers responded independently to Swetnam's work, in defence of their gender. The first response was by Rachel Speght

Rachel Speght (1597 – death date unknown) was a poet and polemicist. She was the first Englishwoman to identify herself, by name, as a polemicist and critic of gender ideology. Speght, a feminist and a Calvinist, is perhaps best known for her tr ...

, writing under her own name. ''A Mouzell for Melastomus'' focuses on biblical material, interpreting scripture to counter Swetnam's attacks, while criticising its grammar and style. She writes, "Whoso makes the fruit of his cogitations extant to the view of all men should have his work to be as a well-tuned instrument, in all places according and agreeing, the which I am sure yours doth not" (p. 36). She also responds briefly to his tract in her second publication, ''Mortalities Memorandum''.

The second response came in 1617 from a writer under the pseudonym Esther Sowernam ("Sour"nam, as opposed to "Sweet"nam). ''Ester Hath Hang'd Haman'' is most notable for its reasoned and well-ordered argument.

Next, also in 1617, was ''Worming of a Mad Dogge'', by a writer under the pseudonym Constantia Munda. This tract deployed both invective and learning of French, Italian, Latin and the language of the law. The demonstration of wide education and the inventive used has cast doubt of Constantia being a woman, but within the text she indicates that she is a daughter. The pamphlet was recorded on 29 April 1617 by Laurence Hayes without an author. It has been guessed that the writer may have been employed by Hayes.

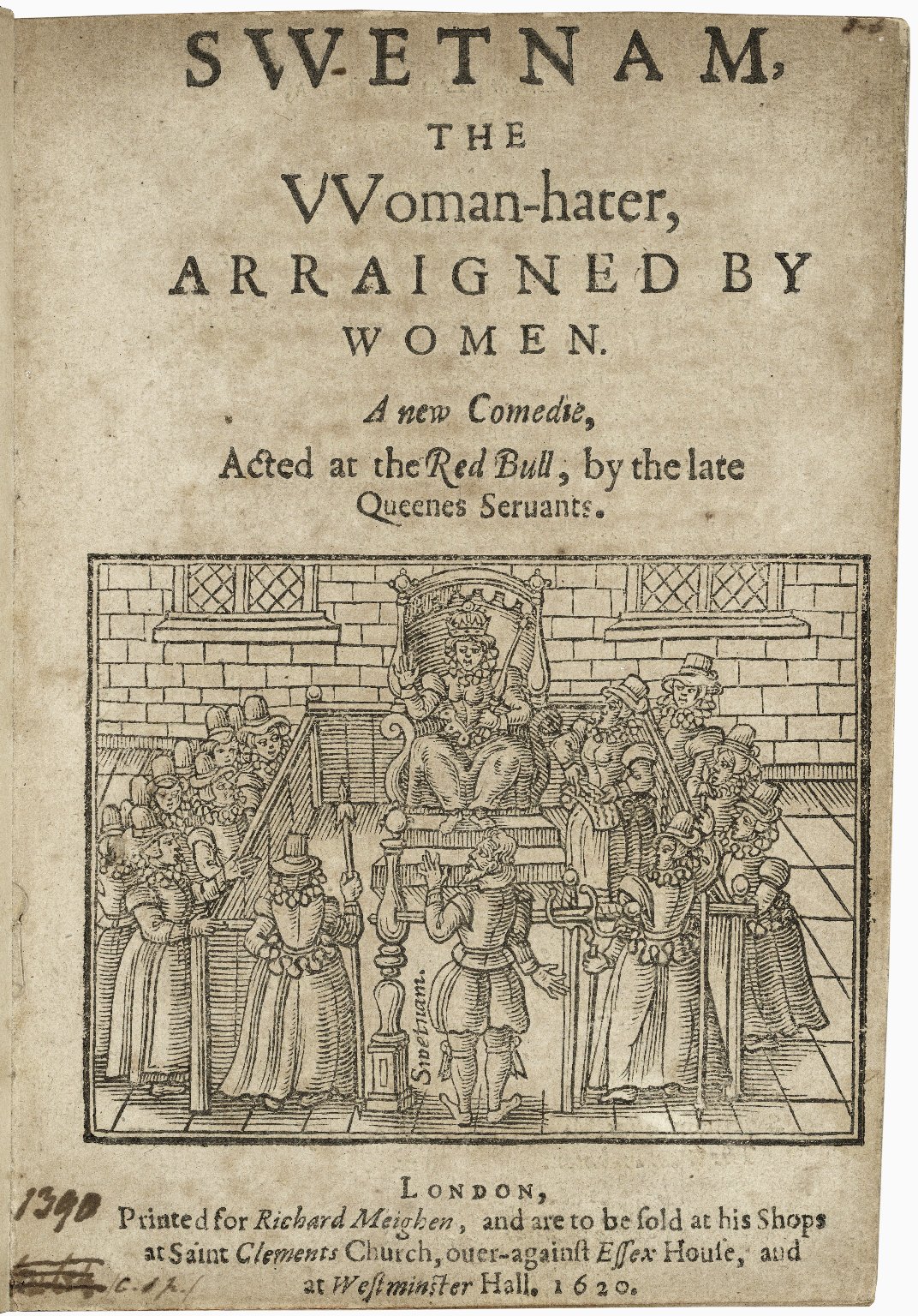

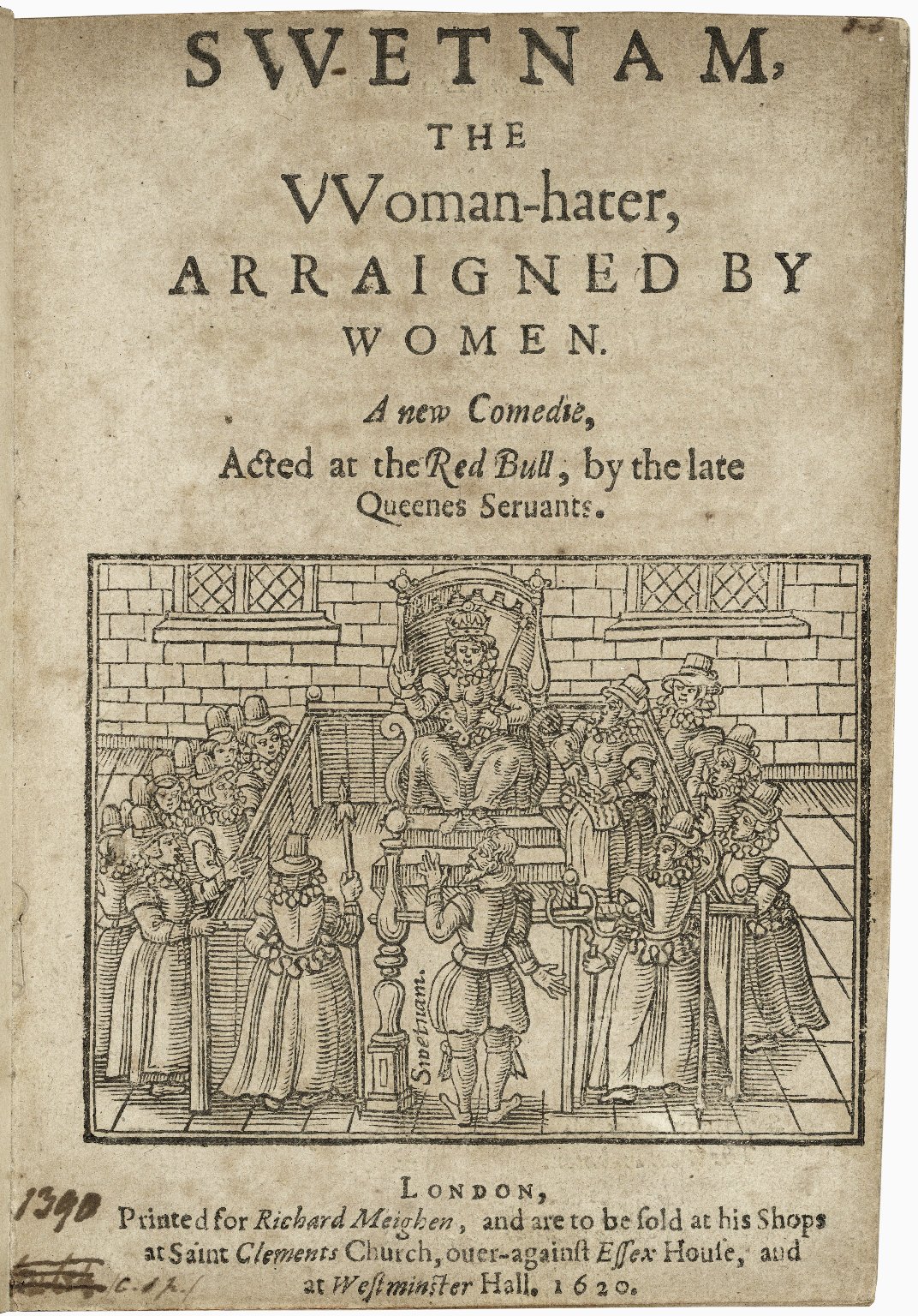

Another reply to Swetnam was the comic play, '' Swetnam the Woman-Hater Arraigned by Women'' (1620), anonymously written. In it, Swetnam, under the name "Misogynos", is made uncomfortable at the hands of the women he despises. The play reflects the popularity of Swetnam's tract with the "common people": it was performed at London's Red Bull Theatre

The Red Bull was an inn-yard conversion erected in Clerkenwell, London operating in the 17th century. For more than four decades, it entertained audiences drawn primarily from the City and its suburbs, developing a reputation over the years for r ...

, which had a populist reputation. The play is credited with originating the English term misogyny

Misogyny () is hatred of, contempt for, or prejudice against women. It is a form of sexism that is used to keep women at a lower social status than men, thus maintaining the societal roles of patriarchy. Misogyny has been widely practiced f ...

.

Fencing manual

In his 1617

In his 1617 fencing

Fencing is a group of three related combat sports. The three disciplines in modern fencing are the foil, the épée, and the sabre (also ''saber''); winning points are made through the weapon's contact with an opponent. A fourth discipline ...

treatise, ''The Schoole of the Noble and Worthy Science of Defence'', Joseph Swetnam represents himself as the fencing instructor for the then-deceased Prince Henry, who, after having read the treatise, urged Swetnam to print it—according to Swetnam. There is no record of his employment in Henry's service. The treatise itself is a manual detailing the use of the rapier

A rapier () or is a type of sword with a slender and sharply-pointed two-edged blade that was popular in Western Europe, both for civilian use (dueling and self-defense) and as a military side arm, throughout the 16th and 17th centuries.

Impo ...

, rapier and dagger

A dagger is a fighting knife with a very sharp point and usually two sharp edges, typically designed or capable of being used as a thrusting or stabbing weapon.State v. Martin, 633 S.W.2d 80 (Mo. 1982): This is the dictionary or popular-use de ...

, backsword

A backsword is a type of sword characterised by having a single-edged blade and a hilt with a single-handed grip. It is so called because the triangular cross section gives a flat back edge opposite the cutting edge. Later examples often have a " ...

, sword

A sword is an edged, bladed weapon intended for manual cutting or thrusting. Its blade, longer than a knife or dagger, is attached to a hilt and can be straight or curved. A thrusting sword tends to have a straighter blade with a pointed ti ...

and dagger, and quarterstaff

A quarterstaff (plural quarterstaffs or quarterstaves), also short staff or simply staff is a traditional European pole weapon, which was especially prominent in England during the Early Modern period.

The term is generally accepted to refer t ...

, prefaced with eleven chapters of moral and social advice relating to fencing, self-defence, and honour. Swetnam claims that his fencing treatise is "the first of any English-mans invention, which professed the sayd Science".

Swetnam is known for teaching a unique series of special guards (such as the fore-hand guard, broadwarde, lazie guard, and crosse guard), though his primary position is a "true guard", which varies slightly for each weapon. He advocates the use of thrusts over cuts and makes heavy use of feints. Swetnam favoured fencing from a long distance, using the lunge, and not engaging weapons. His defences are mostly simple parries, together with slips (evasive movements backward).

Swetnam's fencing system has been linked both to contemporary Italian systems as well as the traditional sword arts of England; his guard positions resemble those of contemporary Italian instructors, but his fencing system appears structurally different, and more closely related to a lineage of English fencing. He is also distinctive in his advice to wound rather than kill an opponent.Swetnam, Joseph: "The Schoole of the Noble and Worthy Science of Defence", Chapter XII: ''thou must marke which is the nearest part of thine enemie towards thee, and which lieth most unregarded, whether it be his dagger hand, his knee, or his leg, or where thous maist best hurt him at a large distance without danger to thy selfe, or without killing of thine enemy.'' mphasis added/ref>

Personal life

Nothing is known about his ancestral origins or other family life other than the fact that he had a daughter named Elizabeth, who married in the church of St Augustine the Less Church on 4 November 1613 and died in 1626. In a letter of administration drawn up after her death, Swetnam is referred to as "nuper de civit teBristoll" ("late of the city ofBristol

Bristol () is a city, ceremonial county and unitary authority in England. Situated on the River Avon, it is bordered by the ceremonial counties of Gloucestershire to the north and Somerset to the south. Bristol is the most populous city in ...

"). According to a letter of administration, Swetnam died abroad in 1621.Cis van Heertum,Swetnam, Joseph (d. 1621)

, ''

Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

The ''Dictionary of National Biography'' (''DNB'') is a standard work of reference on notable figures from British history, published since 1885. The updated ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'' (''ODNB'') was published on 23 September ...

'', Oxford University Press, 2004; online edition, January 2008. Retrieved 25 December 2013.

References

External links

Half Humankind: Contexts and Texts of the Controversy about Women in England 1540–1640

Half Humankind, a book about the Pamphlet Wars in England, among other things.

a transcription of the practical sections of Swetnam's fencing manual.

The Schoole of the Noble and Worthy Science of Defence – Complete, PDF

a complete facsimile scan of the fencing manual.

A short video introduction to Swetnam's rapier fencing system

{{DEFAULTSORT:Swetnam, Joseph 17th-century English writers 17th-century English male writers Year of birth unknown Year of death unknown Historical European martial arts English male writers