Joseph Justus Scaliger on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

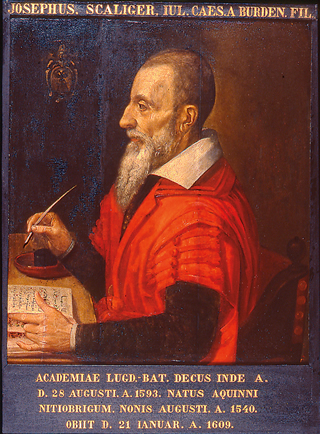

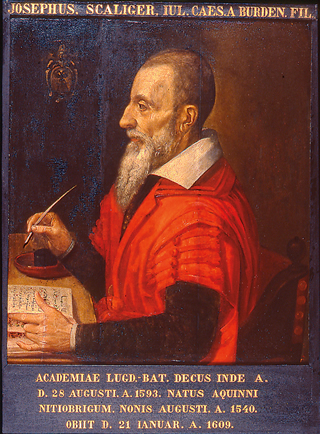

Joseph Justus Scaliger (; 5 August 1540 – 21 January 1609) was a French

Joseph Justus Scaliger (; 5 August 1540 – 21 January 1609) was a French

After his father's death, Scaliger spent four years at the

After his father's death, Scaliger spent four years at the

When Justus Lipsius retired from the

When Justus Lipsius retired from the

*

*

*

*

*

*

Correspondents of Scaliger

Joseph Justus Scaliger maintained a vast correspondence with European humanists and scholars, whose names are listed here

The Correspondence of Joseph Justus Scaliger

i

EMLO

{{DEFAULTSORT:Scaliger, Joseph Justus People from Agen 1540 births 1609 deaths 16th-century French historians 16th-century Latin-language writers 17th-century Latin-language writers 16th-century French writers 16th-century male writers 17th-century French writers 17th-century French male writers Chronologists French classical scholars French book and manuscript collectors Leiden University faculty College of Guienne alumni University of Paris alumni University of Geneva faculty 17th-century Dutch people French Protestants Converts to Protestantism French male non-fiction writers French people of Italian descent

Joseph Justus Scaliger (; 5 August 1540 – 21 January 1609) was a French

Joseph Justus Scaliger (; 5 August 1540 – 21 January 1609) was a French Calvinist

Calvinism (also called the Reformed Tradition, Reformed Protestantism, Reformed Christianity, or simply Reformed) is a major branch of Protestantism that follows the theological tradition and forms of Christian practice set down by John C ...

religious leader and scholar, known for expanding the notion of classical history from Greek and Ancient Roman

In modern historiography, ancient Rome refers to Roman civilisation from the founding of the city of Rome in the 8th century BC to the collapse of the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century AD. It encompasses the Roman Kingdom (753–50 ...

history to include Persian, Babylonia

Babylonia (; Akkadian: , ''māt Akkadī'') was an ancient Akkadian-speaking state and cultural area based in the city of Babylon in central-southern Mesopotamia (present-day Iraq and parts of Syria). It emerged as an Amorite-ruled state c ...

n, Jewish

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

and Ancient Egyptian history. He spent the last sixteen years of his life in the Netherlands

)

, anthem = ( en, "William of Nassau")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of the Netherlands

, established_title = Before independence

, established_date = Spanish Netherl ...

.

Early life

In 1540, Scaliger was born inAgen

The commune of Agen (, ; ) is the prefecture of the Lot-et-Garonne department in Nouvelle-Aquitaine, southwestern France. It lies on the river Garonne southeast of Bordeaux.

Geography

The city of Agen lies in the southwestern departme ...

, France, to Italian scholar and physician Julius Caesar Scaliger and his wife, Andiette de Roques Lobejac. His only formal education was three years of study at the College of Guienne in Bordeaux

Bordeaux ( , ; Gascon oc, Bordèu ; eu, Bordele; it, Bordò; es, Burdeos) is a port city on the river Garonne in the Gironde department, Southwestern France. It is the capital of the Nouvelle-Aquitaine region, as well as the prefectu ...

, which ended in 1555 due to an outbreak of the bubonic plague

Bubonic plague is one of three types of plague caused by the plague bacterium ('' Yersinia pestis''). One to seven days after exposure to the bacteria, flu-like symptoms develop. These symptoms include fever, headaches, and vomiting, as wel ...

. Until his death in 1558, Julius Scaliger taught his son Latin and poetry; he was made to write at least 80 lines of Latin a day.

University and travels

After his father's death, Scaliger spent four years at the

After his father's death, Scaliger spent four years at the University of Paris

, image_name = Coat of arms of the University of Paris.svg

, image_size = 150px

, caption = Coat of Arms

, latin_name = Universitas magistrorum et scholarium Parisiensis

, motto = ''Hic et ubique terrarum'' (Latin)

, mottoeng = Here and a ...

, where he studied Greek under Adrianus Turnebus

Adrianus Turnebus (french: Adrien Turnèbe or ''Tournebeuf''; 151212 June 1565) was a French classical scholar.

Life

Turnebus was born in Les Andelys in Normandy. At the age of twelve he was sent to Paris to study, and attracted great notice by ...

. After two months he found he was not in a position to profit from the lectures of the greatest Greek scholar of the time. He read Homer

Homer (; grc, Ὅμηρος , ''Hómēros'') (born ) was a Greek poet who is credited as the author of the ''Iliad'' and the ''Odyssey'', two epic poems that are foundational works of ancient Greek literature. Homer is considered one of the ...

in twenty-one days, and afterwards read other classical Greek poets, orators, and historians, forming a grammar

In linguistics, the grammar of a natural language is its set of structural constraints on speakers' or writers' composition of clauses, phrases, and words. The term can also refer to the study of such constraints, a field that includes doma ...

for himself as he went along. At the suggestion of Guillaume Postel, after learning Greek he learned Hebrew

Hebrew (; ; ) is a Northwest Semitic language of the Afroasiatic language family. Historically, it is one of the spoken languages of the Israelites and their longest-surviving descendants, the Jews and Samaritans. It was largely preserved ...

, and then Arabic

Arabic (, ' ; , ' or ) is a Semitic language spoken primarily across the Arab world.Semitic languages: an international handbook / edited by Stefan Weninger; in collaboration with Geoffrey Khan, Michael P. Streck, Janet C. E.Watson; Walter ...

, becoming proficient in both.

His most important teacher was Jean Dorat

Jean Daurat ( Occitan: Joan Dorat; Latin: Auratus) (3 April 15081 November 1588) was a French poet, scholar and a member of a group known as '' The Pléiade''.

Early life

He was born Joan Dinemandy in Limoges and was a member of a noble famil ...

, who was able not only to impart knowledge but also to kindle enthusiasm in Scaliger. It was to Dorat that Scaliger owed his home for the next thirty years of his life, for in 1563 the professor recommended him to Louis de Chasteigner, the young lord of La Roche-Posay

La Roche-Posay () is a commune in the Vienne department in the Nouvelle-Aquitaine region in western France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Over ...

, as a companion in his travels. The two young men formed a close friendship which remained unbroken until Louis's death in 1595. The travellers first went to Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus ( legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

. Here they found Marc Antoine Muret, who, when at Bordeaux

Bordeaux ( , ; Gascon oc, Bordèu ; eu, Bordele; it, Bordò; es, Burdeos) is a port city on the river Garonne in the Gironde department, Southwestern France. It is the capital of the Nouvelle-Aquitaine region, as well as the prefectu ...

and Toulouse

Toulouse ( , ; oc, Tolosa ) is the prefecture of the French department of Haute-Garonne and of the larger region of Occitania. The city is on the banks of the River Garonne, from the Mediterranean Sea, from the Atlantic Ocean and fr ...

, had been a great favourite and occasional visitor of Julius Caesar Scaliger at Agen. Muret soon recognized the young Scaliger's merits and introduced him to many contacts well worth knowing.

After visiting a large part of Italy, the travellers moved on to England and Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a border with England to the southeast and is otherwise surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean to ...

, passing through the town of La Roche-Posay on their way. During his time in the British Isles, Scaliger formed an unfavourable opinion of the English. Their inhuman disposition and inhospitable treatment of foreigners especially made a negative impression on him. He was also disappointed at finding only a few Greek manuscripts and, in his opinion, few learned men. It was not until a much later period that he became intimate with Richard Thomson and other Englishmen. Over the course of his travels, he became a Protestant

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

.

France, Geneva, and back to France

On his return to France, he spent three years with the Chastaigners, accompanying them to their different ''château

A château (; plural: châteaux) is a manor house or residence of the lord of the manor, or a fine country house of nobility or gentry, with or without fortifications, originally, and still most frequently, in French-speaking regions.

No ...

x'' in Poitou, as the calls of the civil war required. In 1570 he accepted the invitation of Jacques Cujas

Jacques Cujas (or Cujacius) ( Toulouse, 1522 – Bourges, 4 October 1590) was a French legal expert. He was prominent among the legal humanists or ''mos gallicus'' school, which sought to abandon the work of the medieval Commentators and conce ...

and proceeded to Valence to study jurisprudence

Jurisprudence, or legal theory, is the theoretical study of the propriety of law. Scholars of jurisprudence seek to explain the nature of law in its most general form and they also seek to achieve a deeper understanding of legal reasoning ...

under the greatest living jurist. Here he remained three years, profiting not only by the lectures but even more by the library of Cujas, which filled no fewer than seven or eight rooms and included five hundred manuscripts.

The St Bartholomew's Day Massacre

The St. Bartholomew's Day massacre (french: Massacre de la Saint-Barthélemy) in 1572 was a targeted group of assassinations and a wave of Catholic mob violence, directed against the Huguenots (French Calvinist Protestants) during the French Wa ...

– which occurred just before he was to accompany the bishop of Valence

The Roman Catholic Diocese of Valence (–Die–Saint-Paul-Trois-Châteaux) ( Latin: ''Dioecesis Valentinensis (–Diensis–Sancti Pauli Tricastinorum)''; French: ''Diocèse de Valence (–Die–Saint-Paul-Trois-Châteaux'') is a diocese of the ...

on an embassy to Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populou ...

– caused Scaliger to flee, alongside other Huguenot

The Huguenots ( , also , ) were a religious group of French Protestants who held to the Reformed, or Calvinist, tradition of Protestantism. The term, which may be derived from the name of a Swiss political leader, the Genevan burgomaster Be ...

s, to Geneva

Geneva ( ; french: Genève ) frp, Genèva ; german: link=no, Genf ; it, Ginevra ; rm, Genevra is the second-most populous city in Switzerland (after Zürich) and the most populous city of Romandy, the French-speaking part of Switzerland. Situa ...

, where he was appointed a professor at the Academy of Geneva. While there, he lectured on Aristotle's

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of phil ...

'' Organon'' and Cicero's ''De Finibus'' to much satisfaction for the students, but not appreciating it himself. He hated lecturing and was bored with the persistence of the fanatical preachers, accordingly in 1574 he returned to France and made his home for the next twenty years with Chastaigner.

Of his life during this period we have interesting details and notices in the ''Lettres françaises inédites de Joseph Scaliger'', edited by Tamizey de Larroque (Agen, 1881). Constantly moving through Poitou and the Limousin, as the exigencies of the civil war required, occasionally taking his turn as a guard, at least on one occasion trailing a pike on an expedition against the Leaguers, with no access to libraries, and frequently separated even from his own books, his life during this period seems most unsuited to study. He had, however, what so few contemporary scholars possessed – leisure and freedom from financial cares.

Academic output

It was during this period of his life that he composed and published his books of historical criticism. His editions of the ''Catalecta'' (1575), of Festus (1575), ofCatullus

Gaius Valerius Catullus (; 84 - 54 BCE), often referred to simply as Catullus (, ), was a Latin poet of the late Roman Republic who wrote chiefly in the neoteric style of poetry, focusing on personal life rather than classical heroes. His ...

, Tibullus

Albius Tibullus ( BC19 BC) was a Latin poet and writer of elegies. His first and second books of poetry are extant; many other texts attributed to him are of questionable origins.

Little is known about the life of Tibullus. There are only a f ...

and Propertius

Sextus Propertius was a Latin elegiac poet of the Augustan age. He was born around 50–45 BC in Assisium and died shortly after 15 BC.

Propertius' surviving work comprises four books of '' Elegies'' ('). He was a friend of the poets Gallu ...

(1577), are the work of a man determined to discover the real meaning and force of his author. He was the first to lay down and apply sound rules of criticism and revision, and to change textual criticism from a series of haphazard guesses into a "rational procedure subject to fixed laws" ( Mark Pattison).

These works, despite proving Scaliger's skill among his contemporaries as a Latin scholar and critic, did not go beyond simple scholarship. It was reserved for his edition of Manilius (1579), and his ''De emendatione temporum'' (1583), to revolutionize perceived ideas of ancient chronology

Chronology (from Latin ''chronologia'', from Ancient Greek , ''chrónos'', "time"; and , ''-logia'') is the science of arranging events in their order of occurrence in time. Consider, for example, the use of a timeline or sequence of even ...

—to show that ancient history was not confined to that of the Greeks

The Greeks or Hellenes (; el, Έλληνες, ''Éllines'' ) are an ethnic group and nation indigenous to the Eastern Mediterranean and the Black Sea regions, namely Greece, Cyprus, Albania, Italy, Turkey, Egypt, and, to a lesser extent, ot ...

and Romans, but also comprises that of the Persia

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

ns, the Babylonians and the Egyptians

Egyptians ( arz, المَصرِيُون, translit=al-Maṣriyyūn, ; arz, المَصرِيِين, translit=al-Maṣriyyīn, ; cop, ⲣⲉⲙⲛ̀ⲭⲏⲙⲓ, remenkhēmi) are an ethnic group native to the Nile, Nile Valley in Egypt. Egyptian ...

, hitherto neglected, and that of the Jews

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

, hitherto treated as a thing apart; and that the historical narratives and fragments of each of these, and their several systems of chronology, must be critically compared. It was this innovation that distinguished Scaliger from contemporary scholars. Neither they nor those who immediately followed seem to have appreciated his innovation. Instead, they valued his emendatory criticism and his skill in Greek. His commentary on Manilius is a treatise on ancient astronomy

Astronomy () is a natural science that studies celestial objects and phenomena. It uses mathematics, physics, and chemistry in order to explain their origin and evolution. Objects of interest include planets, moons, stars, nebulae, g ...

, and it forms an introduction to ''De emendatione temporum''; in this work, Scaliger investigates ancient systems of determining epoch

In chronology and periodization, an epoch or reference epoch is an instant in time chosen as the origin of a particular calendar era. The "epoch" serves as a reference point from which time is measured.

The moment of epoch is usually decided ...

s, calendar

A calendar is a system of organizing days. This is done by giving names to periods of time, typically days, weeks, months and years. A date is the designation of a single and specific day within such a system. A calendar is also a phy ...

s and computations of time. Applying the work of Nicolaus Copernicus

Nicolaus Copernicus (; pl, Mikołaj Kopernik; gml, Niklas Koppernigk, german: Nikolaus Kopernikus; 19 February 1473 – 24 May 1543) was a Renaissance polymath, active as a mathematician, astronomer, and Catholic canon, who formulat ...

and other modern scientists, he reveals the principles behind these systems.

In the remaining twenty-four years of his life, he expanded on his work in the ''De emendatione''. He succeeded in reconstructing the lost ''Chronicle'' of Eusebius

Eusebius of Caesarea (; grc-gre, Εὐσέβιος ; 260/265 – 30 May 339), also known as Eusebius Pamphilus (from the grc-gre, Εὐσέβιος τοῦ Παμφίλου), was a Greek historian of Christianity, exegete, and Chris ...

—one of the most valuable ancient documents, especially valuable for ancient chronology. This he printed in 1606 in his ''Thesaurus temporum'', in which he collected, restored, and arranged every chronological relic extant in Greek or Latin.

The Netherlands

University of Leiden

Leiden University (abbreviated as ''LEI''; nl, Universiteit Leiden) is a public research university in Leiden, Netherlands. The university was founded as a Protestant university in 1575 by William, Prince of Orange, as a reward to the city of Le ...

in 1590, the university and its protectors, the States-General of the Netherlands

)

, anthem = ( en, "William of Nassau")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of the Netherlands

, established_title = Before independence

, established_date = Spanish Netherl ...

and the Prince of Orange

Prince of Orange (or Princess of Orange if the holder is female) is a title originally associated with the sovereign Principality of Orange, in what is now southern France and subsequently held by sovereigns in the Netherlands.

The titl ...

, resolved to appoint Scaliger as his successor. He declined; he hated lecturing, and there were those among his friends who erroneously believed that with the success of Henry IV learning would flourish, and Protestantism would be no barrier to his advancement. The invitation was renewed in the most flattering manner a year later; the invitation stated Scaliger would not be required to lecture, and that the university wished only for his presence, while he would be able to dispose of his own time in all respects. This offer Scaliger accepted provisionally. Midway through 1593, he set out for the Netherlands, where he would pass the remaining sixteen years of his life, never returning to France. His reception at Leiden was all that he could have wished for. He received a handsome income; he was treated with the highest consideration. His supposed rank as a prince of Verona

Verona ( , ; vec, Verona or ) is a city on the Adige River in Veneto, Italy, with 258,031 inhabitants. It is one of the seven provincial capitals of the region. It is the largest city municipality in the region and the second largest in nor ...

, a sensitive issue for the Scaligeri, was recognized. Leiden lying between The Hague

The Hague ( ; nl, Den Haag or ) is a city and municipality of the Netherlands, situated on the west coast facing the North Sea. The Hague is the country's administrative centre and its seat of government, and while the official capital o ...

and Amsterdam

Amsterdam ( , , , lit. ''The Dam on the River Amstel'') is the capital and most populous city of the Netherlands, with The Hague being the seat of government. It has a population of 907,976 within the city proper, 1,558,755 in the urban ar ...

, Scaliger was able to enjoy, besides the learned circle of Leiden, the advantages of the best society of both these capitals. For Scaliger was no hermit buried among his books; he was fond of social intercourse and was himself a good talker.

During the first seven years of his residence at Leiden, his reputation was at its highest point. His literary judgment was unquestioned. From his throne at Leiden he ruled the learned world; a word from him could make or mar a rising reputation, and he was surrounded by young men eager to listen to and profit from his conversation. He encouraged Grotius when only a youth of sixteen to edit Martianus Capella

Martianus Minneus Felix Capella (fl. c. 410–420) was a jurist, polymath and Latin prose writer of late antiquity, one of the earliest developers of the system of the seven liberal arts that structured early medieval education. He was a nati ...

. At the early death of the younger Douza, he wept as at that of a beloved son. Daniel Heinsius

Daniel is a masculine given name and a surname of Hebrew origin. It means "God is my judge"Hanks, Hardcastle and Hodges, ''Oxford Dictionary of First Names'', Oxford University Press, 2nd edition, , p. 68. (cf. Gabriel—"God is my strength"), ...

, at first his favourite pupil, became his most intimate friend.

At the same time, Scaliger had made numerous enemies. He hated ignorance, but he hated still more half-learning, and most of all dishonesty in argument or quotation. He had no toleration for the disingenuous argument and the misstatements of facts of those who wrote to support a theory or to defend an unsound cause. His pungent sarcasm soon reached the ears of the persons who were its object, and his pen was not less bitter than his tongue. He was conscious of his power, and not always sufficiently cautious or sufficiently gentle in its exercise. Nor was he always right. He trusted much to his memory, which was occasionally treacherous. His emendations, if often valuable, were sometimes absurd. In laying the foundations of a science of ancient chronology he relied sometimes on groundless or even absurd hypotheses, often based on an imperfect induction The imperfect induction is the process of inferring from a sample

Sample or samples may refer to:

Base meaning

* Sample (statistics), a subset of a population – complete data set

* Sample (signal), a digital discrete sample of a continuous an ...

of facts. Sometimes he misunderstood the astronomical science of the ancients, sometimes that of Copernicus

Nicolaus Copernicus (; pl, Mikołaj Kopernik; gml, Niklas Koppernigk, german: Nikolaus Kopernikus; 19 February 1473 – 24 May 1543) was a Renaissance polymath, active as a mathematician, astronomer, and Catholic canon, who formulat ...

and Tycho Brahe

Tycho Brahe ( ; born Tyge Ottesen Brahe; generally called Tycho (14 December 154624 October 1601) was a Danish astronomer, known for his comprehensive astronomical observations, generally considered to be the most accurate of his time. He was ...

. And he was no mathematician.

Disagreements with the Jesuits

But his enemies were not merely those whose errors he had exposed and whose hostility he had excited by the violence of his language. The results of his method of historical criticism threatened the Catholic controversialists and the authenticity of many of the documents on which they relied. TheJesuits

, image = Ihs-logo.svg

, image_size = 175px

, caption = ChristogramOfficial seal of the Jesuits

, abbreviation = SJ

, nickname = Jesuits

, formation =

, founders = ...

, who aspired to be the source of all scholarship and criticism, saw the writings and authority of Scaliger as a formidable barrier to their claims. Muret in the latter part of his life professed the strictest orthodoxy, Lipsius had been reconciled to the Church of Rome, Isaac Casaubon was supposed to be wavering, but Scaliger was known to be an irreconcilable Protestant. As long as his intellectual supremacy was unquestioned, the Protestants had the advantage in learning and scholarship. His enemies therefore aimed, if not to answer his criticisms or to disprove his statements, yet to attack him as a man and destroy his reputation. This was no easy task, for his moral character was absolutely spotless.

Veronese descent

After several attacks purportedly by the Jesuits, in 1607 a new attempt was made. In 1594 Scaliger had published his ''Epistola de vetustate et splendore gentis Scaligerae et JC Scaligeri vita''. In 1601 Gaspar Scioppius, then in the service of the Jesuits published his ''Scaliger Hypobolimaeus'' ("The Supposititious Scaliger"), aquarto

Quarto (abbreviated Qto, 4to or 4º) is the format of a book or pamphlet produced from full sheets printed with eight pages of text, four to a side, then folded twice to produce four leaves. The leaves are then trimmed along the folds to produc ...

volume of more than four hundred pages. The author purports to point out five hundred lies in the ''Epistola de vetustate'' of Scaliger, but the main argument of the book is to show the falsity of his pretensions to be of the family of La Scala, and the narrative of his father's early life. "No stronger proof," says Pattison, "can be given of the impressions produced by this powerful philippic, dedicated to the defamation of an individual, than that it had been the source from which the biography of Scaliger, as it now stands in our biographical collections, has mainly flowed."

To Scaliger, the publication of ''Scaliger Hypobolimaeus ''was crushing. Whatever his father Julius had believed, Joseph had never doubted himself to be a prince of Verona, and in his ''Epistola'' had put forth all that he had heard from his father. He wrote a reply to Scioppius, entitled ''Confutatio fabulae Burdonum''. In the opinion of Pattison, "as a refutation of Scioppius it is most complete"; but there are certainly grounds for dissenting from this judgment. Scaliger purported that Scioppius committed more blunders than he corrected, claiming that the book made untruthful allegations, but he did not succeed in adducing any proof either of his father's descent from the La Scala family, or of any of the events narrated by Julius before he arrived at Agen. Nor does Scaliger attempt a refutation of the crucial point, namely, that William, the last prince of Verona, had no son Nicholas, who would have been the alleged grandfather of Julius.

Complete or not, the ''Confutatio'' had little success; the attack attributed to the Jesuits was successful. Scioppius was wont to boast that his book had killed Scaliger. The ''Confutatio'' was Scaliger's last work. Five months after it appeared, on 21 January 1609, at four in the morning, he died at Leiden in the arms of his pupil and friend Heinsius. In his will Scaliger bequeathed his renowned collection of manuscripts and books (''tous mes livres de langues étrangères, Hebraiques, Syriens, Arabiques, Ethiopiens'') to Leiden University Library

Leiden University Libraries is a library founded in 1575 in Leiden, Netherlands. It is regarded as a significant place in the development of European culture: it is a part of a small number of cultural centres that gave direction to the developme ...

.

Sources

One notable biography of Joseph Scaliger is that of Jakob Bernays (Berlin, 1855). It was reviewed by Pattison in the ''Quarterly Review'', vol. cviii (1860), since reprinted in the ''Essays'', i (1889), 132–195. Pattison had made many manuscript collections for the life of Joseph Scaliger on a much more extensive scale, which he left unfinished. In writing the above article, Professor Christie had access to and made much use of these manuscripts, which include the life of Julius Caesar Scaliger. The fragments of the life of Joseph Scaliger have been printed in the ''Essays'', i. 196–245. For the life of Joseph, besides the letters published by Tamizis de Larroque (Agen, 1881), the two old collections of Latin and French letters and the two ''Scaligerana'' are the most important sources of information. The complete correspondence of Scaliger is now available in eight volumes.''The Correspondence of Joseph Justus Scaliger'', 8 vol. ; ed. by Paul Botley and Dirk van Miert. Supervisory editors Anthony Grafton, Henk Jan De Jonge and Jill Kraye. Genève : Droz, 2012. (Travaux d'Humanisme et Renaissance ; 507). . For the life of his father Julius Caesar Scaliger, the letters edited by his son, those subsequently published in 1620 by the President de Maussac, the ''Scaligerana'', and his own writings are full of autobiographical matter, are the chief authorities. Jules de Bourousse de Laffore's ''Etude sur Jules César de Lescale'' (Agen, 1860) and Adolphe Magen's ''Documents sur Julius Caesar Scaliger et sa famille'' (Agen, 1873) add important details to the lives of both father and son. The lives by Charles Nisard – that of ''Julius et Les Gladiateurs de la république des lettres'', and that of Joseph ''Le Triumvirat littéraire au seizième siècle'' – are equally unworthy of their author and their subjects. Julius is simply held up to ridicule, while the life of Joseph is almost wholly based on the book of Scioppius and the ''Scaligerana''. A complete list of the works of Joseph will be found in his life by Jakob Bernays. See alsoJ. E. Sandys

Sir John Edwin Sandys ( "Sands"; 19 May 1844 – 6 July 1922) was an English classical scholar.

Life

Born in Leicester, England on 19 May 1844, Sandys was the 4th son of Rev. Timothy Sandys (1803–1871) and Rebecca Swain (1800–1853). Livi ...

, ''History of Classical Scholarship'', ii. (1908), 199–204. A technical biography is Anthony T. Grafton, ''Joseph Scaliger: A Study in the History of Classical Scholarship'', 2 vol. (Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1983, 1993).

See also

*History of scholarship

The scholarly method or scholarship is the body of principles and practices used by scholars and academics to make their claims about the subject as valid and trustworthy as possible, and to make them known to the scholarly public. It is the met ...

*Julian Period

The Julian day is the continuous count of days since the beginning of the Julian period, and is used primarily by astronomers, and in software for easily calculating elapsed days between two events (e.g. food production date and sell by date).

...

– a tricyclic system of years proposed by Scaliger

* New Chronology (Fomenko)

References

Works

*

*

*

*

*

*

External links

* * *Correspondents of Scaliger

Joseph Justus Scaliger maintained a vast correspondence with European humanists and scholars, whose names are listed here

The Correspondence of Joseph Justus Scaliger

i

EMLO

{{DEFAULTSORT:Scaliger, Joseph Justus People from Agen 1540 births 1609 deaths 16th-century French historians 16th-century Latin-language writers 17th-century Latin-language writers 16th-century French writers 16th-century male writers 17th-century French writers 17th-century French male writers Chronologists French classical scholars French book and manuscript collectors Leiden University faculty College of Guienne alumni University of Paris alumni University of Geneva faculty 17th-century Dutch people French Protestants Converts to Protestantism French male non-fiction writers French people of Italian descent