Joseph Henry on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Joseph Henry (December 17, 1797– May 13, 1878) was an American scientist who served as the first Secretary of the

Joseph Henry (December 17, 1797– May 13, 1878) was an American scientist who served as the first Secretary of the

Henry excelled at his studies (so much so, he would often help his teachers teach science) and in 1826 was appointed Professor of Mathematics and Natural Philosophy at

Henry excelled at his studies (so much so, he would often help his teachers teach science) and in 1826 was appointed Professor of Mathematics and Natural Philosophy at  Using his newly developed electromagnetic principle, in 1831, Henry created one of the first machines to use electromagnetism for motion. This was the earliest ancestor of modern DC motor. It did not make use of rotating motion, but was merely an electromagnet perched on a pole, rocking back and forth. The rocking motion was caused by one of the two leads on both ends of the magnet rocker touching one of the two battery cells, causing a polarity change, and rocking the opposite direction until the other two leads hit the other battery.

This apparatus allowed Henry to recognize the property of self inductance. British scientist

Using his newly developed electromagnetic principle, in 1831, Henry created one of the first machines to use electromagnetism for motion. This was the earliest ancestor of modern DC motor. It did not make use of rotating motion, but was merely an electromagnet perched on a pole, rocking back and forth. The rocking motion was caused by one of the two leads on both ends of the magnet rocker touching one of the two battery cells, causing a polarity change, and rocking the opposite direction until the other two leads hit the other battery.

This apparatus allowed Henry to recognize the property of self inductance. British scientist

As a famous scientist and director of the Smithsonian Institution, Henry received visits from other scientists and inventors who sought his advice. Henry was patient, kindly, self-controlled, and gently humorous. One such visitor was

As a famous scientist and director of the Smithsonian Institution, Henry received visits from other scientists and inventors who sought his advice. Henry was patient, kindly, self-controlled, and gently humorous. One such visitor was

/ref> In 1915 Henry was inducted into the

*1826 – Professor of mathematics and natural philosophy at

*1826 – Professor of mathematics and natural philosophy at

Joseph Henry collection

at th

University of Pennsylvania Libraries

Biographical details

— ''Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences'' (1967), 58(1), pp. 1–10.

Dedication ceremony for the Henry statue (1883)

Published physics papers

— ''On the Production of Currents and Sparks of Electricity from Magnetism'' and ''On Electro-Dynamic Induction (extract)''

Joseph Henry Collection, Smithsonian InstitutionNational Academy of Sciences Biographical Memoir

{{DEFAULTSORT:Henry, Joseph 1797 births 1878 deaths American physicists People from Albany, New York People associated with electricity American people of Scottish descent Secretaries of the Smithsonian Institution Burials at Oak Hill Cemetery (Washington, D.C.) People from Galway, New York Hall of Fame for Great Americans inductees Members of the American Antiquarian Society Scientists from New York (state) The Albany Academy alumni

Joseph Henry (December 17, 1797– May 13, 1878) was an American scientist who served as the first Secretary of the

Joseph Henry (December 17, 1797– May 13, 1878) was an American scientist who served as the first Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution

The Smithsonian Institution ( ), or simply the Smithsonian, is a group of museums and education and research centers, the largest such complex in the world, created by the U.S. government "for the increase and diffusion of knowledge". Found ...

. He was the secretary for the National Institute for the Promotion of Science, a precursor of the Smithsonian Institution. He was highly regarded during his lifetime. While building electromagnets, Henry discovered the electromagnetic phenomenon of self-inductance

Inductance is the tendency of an electrical conductor to oppose a change in the electric current flowing through it. The flow of electric current creates a magnetic field around the conductor. The field strength depends on the magnitude of th ...

. He also discovered mutual inductance independently of Michael Faraday

Michael Faraday (; 22 September 1791 – 25 August 1867) was an English scientist who contributed to the study of electromagnetism and electrochemistry. His main discoveries include the principles underlying electromagnetic inducti ...

, though Faraday was the first to make the discovery and publish his results. Henry developed the electromagnet

An electromagnet is a type of magnet in which the magnetic field is produced by an electric current. Electromagnets usually consist of wire wound into a coil. A current through the wire creates a magnetic field which is concentrated in ...

into a practical device. He invented a precursor to the electric doorbell

A doorbell is a signaling device typically placed near a door to a building's entrance. When a visitor presses a button, the bell rings inside the building, alerting the occupant to the presence of the visitor. Although the first doorbells were ...

(specifically a bell that could be rung at a distance via an electric wire, 1831) and electric relay

A relay

Electromechanical relay schematic showing a control coil, four pairs of normally open and one pair of normally closed contacts

An automotive-style miniature relay with the dust cover taken off

A relay is an electrically operated switch ...

(1835). His work on the electromagnetic relay was the basis of the practical electrical telegraph

Electrical telegraphs were point-to-point text messaging systems, primarily used from the 1840s until the late 20th century. It was the first electrical telecommunications system and the most widely used of a number of early messaging systems ...

, invented by Samuel F. B. Morse and Sir Charles Wheatstone, separately. In his honor the SI unit of inductance

Inductance is the tendency of an electrical conductor to oppose a change in the electric current flowing through it. The flow of electric current creates a magnetic field around the conductor. The field strength depends on the magnitude of th ...

is named the henry (plural: henries; symbol: H

).

Biography

Henry was born inAlbany, New York

Albany ( ) is the capital of the U.S. state of New York, also the seat and largest city of Albany County. Albany is on the west bank of the Hudson River, about south of its confluence with the Mohawk River, and about north of New York Cit ...

, to Scottish immigrants Ann Alexander Henry and William Henry. His parents were poor, and Henry's father died while he was still young. For the rest of his childhood, Henry lived with his grandmother in Galway, New York. He attended a school which would later be named the "Joseph Henry Elementary School" in his honor. After school, he worked at a general store, and at the age of thirteen became an apprentice watchmaker and silversmith. Joseph's first love was theater, and he came close to becoming a professional actor. His interest in science was sparked at the age of sixteen by a book of lectures on scientific topics titled ''Popular Lectures on Experimental Philosophy''. In 1819 he entered The Albany Academy

The Albany Academy is an independent college preparatory day school for boys in Albany, New York, USA, enrolling students from Preschool (age 3) to Grade 12. It was established in 1813 by a charter signed by Mayor Philip Schuyler Van Rensselae ...

, where he was given free tuition. Even with free tuition he was so poor that he had to support himself with teaching and private tutoring positions. He intended to go into medicine, but in 1824 he was appointed an assistant engineer for the survey of the State road being constructed between the Hudson River

The Hudson River is a river that flows from north to south primarily through eastern New York. It originates in the Adirondack Mountains of Upstate New York and flows southward through the Hudson Valley to the New York Harbor between Ne ...

and Lake Erie

Lake Erie ( "eerie") is the fourth largest lake by surface area of the five Great Lakes in North America and the eleventh-largest globally. It is the southernmost, shallowest, and smallest by volume of the Great Lakes and therefore also ha ...

. From then on, he was inspired to a career in either civil or mechanical engineering

Mechanical engineering is the study of physical machines that may involve force and movement. It is an engineering branch that combines engineering physics and mathematics principles with materials science, to design, analyze, manufacture, ...

.

Henry excelled at his studies (so much so, he would often help his teachers teach science) and in 1826 was appointed Professor of Mathematics and Natural Philosophy at

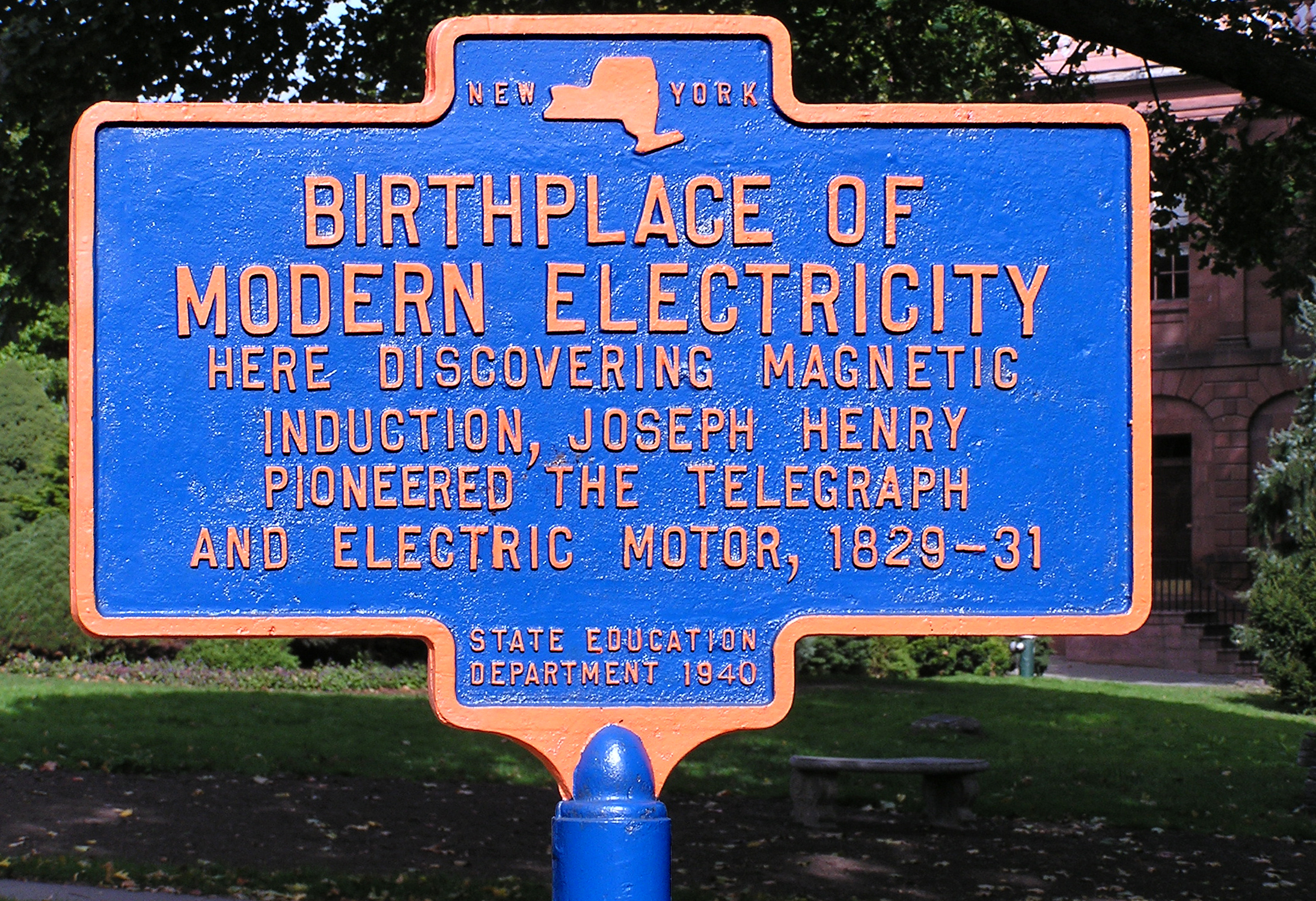

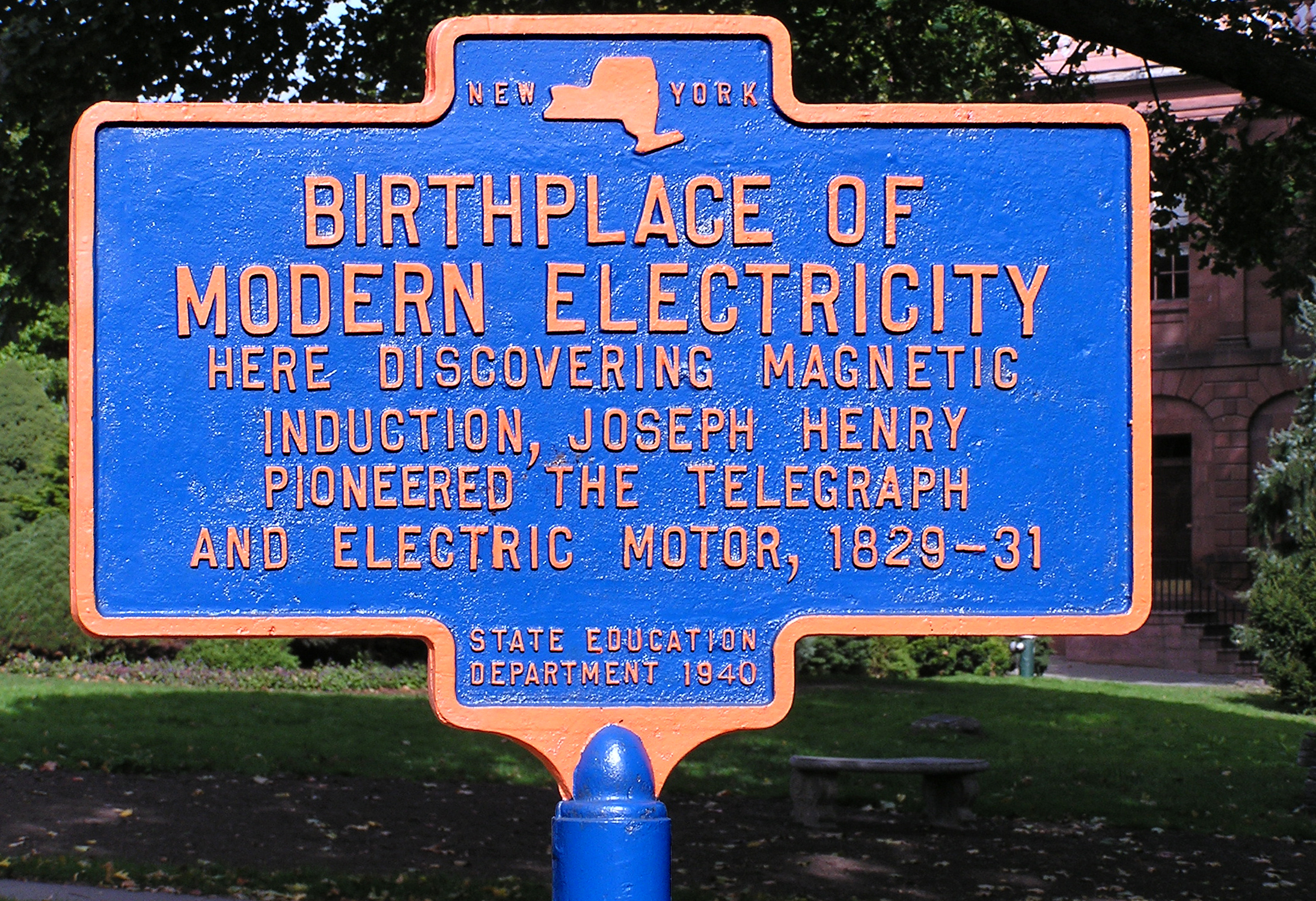

Henry excelled at his studies (so much so, he would often help his teachers teach science) and in 1826 was appointed Professor of Mathematics and Natural Philosophy at The Albany Academy

The Albany Academy is an independent college preparatory day school for boys in Albany, New York, USA, enrolling students from Preschool (age 3) to Grade 12. It was established in 1813 by a charter signed by Mayor Philip Schuyler Van Rensselae ...

by Principal T. Romeyn Beck. Some of his most important research was conducted in this new position. His curiosity about terrestrial magnetism led him to experiment with magnetism

Magnetism is the class of physical attributes that are mediated by a magnetic field, which refers to the capacity to induce attractive and repulsive phenomena in other entities. Electric currents and the magnetic moments of elementary particles ...

in general. He was the first to coil insulated wire tightly around an iron core in order to make a more powerful electromagnet

An electromagnet is a type of magnet in which the magnetic field is produced by an electric current. Electromagnets usually consist of wire wound into a coil. A current through the wire creates a magnetic field which is concentrated in ...

, improving on William Sturgeon's electromagnet which used loosely coiled uninsulated wire. Using this technique, he built the strongest electromagnet at the time, for Yale

Yale University is a private research university in New Haven, Connecticut. Established in 1701 as the Collegiate School, it is the third-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and among the most prestigious in the wor ...

. He also showed that, when making an electromagnet using just two electrode

An electrode is an electrical conductor used to make contact with a nonmetallic part of a circuit (e.g. a semiconductor, an electrolyte, a vacuum or air). Electrodes are essential parts of batteries that can consist of a variety of materials ...

s attached to a battery, it is best to wind several coils of wire in parallel, but when using a set-up with multiple batteries, there should be only one single long coil. The latter made the telegraph

Telegraphy is the long-distance transmission of messages where the sender uses symbolic codes, known to the recipient, rather than a physical exchange of an object bearing the message. Thus flag semaphore is a method of telegraphy, whereas ...

feasible. Because of his early experiments in electromagnetism some historians credit Henry with discoveries pre-dating Faraday and Hertz; however, Henry is not credited due to not publishing his work.

Using his newly developed electromagnetic principle, in 1831, Henry created one of the first machines to use electromagnetism for motion. This was the earliest ancestor of modern DC motor. It did not make use of rotating motion, but was merely an electromagnet perched on a pole, rocking back and forth. The rocking motion was caused by one of the two leads on both ends of the magnet rocker touching one of the two battery cells, causing a polarity change, and rocking the opposite direction until the other two leads hit the other battery.

This apparatus allowed Henry to recognize the property of self inductance. British scientist

Using his newly developed electromagnetic principle, in 1831, Henry created one of the first machines to use electromagnetism for motion. This was the earliest ancestor of modern DC motor. It did not make use of rotating motion, but was merely an electromagnet perched on a pole, rocking back and forth. The rocking motion was caused by one of the two leads on both ends of the magnet rocker touching one of the two battery cells, causing a polarity change, and rocking the opposite direction until the other two leads hit the other battery.

This apparatus allowed Henry to recognize the property of self inductance. British scientist Michael Faraday

Michael Faraday (; 22 September 1791 – 25 August 1867) was an English scientist who contributed to the study of electromagnetism and electrochemistry. His main discoveries include the principles underlying electromagnetic inducti ...

also recognized this property around the same time. Since Faraday published his results first, he became the officially recognized discoverer of the phenomenon.

From 1832 to 1846, Henry served as the first Chair of Natural History at the College of New Jersey (now Princeton University

Princeton University is a private research university in Princeton, New Jersey. Founded in 1746 in Elizabeth as the College of New Jersey, Princeton is the fourth-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and one of the ...

). While in Princeton, he taught a wide range of courses including natural history, chemistry, and architecture, and ran a laboratory on campus. Decades later, Henry wrote that he made "several thousand original investigations on electricity, magnetism, and electro-magnetism" while on the Princeton faculty. Henry relied heavily on an African American research assistant, Sam Parker, in his laboratory and experiments. Parker was a free black man hired by the Princeton trustees to assist Henry. In an 1841 letter to mathematician Elias Loomis, Henry wrote:

The Trustees have however furnished me with an article which I now find indispensable namely with a coloured servant whom I have taught to manage my batteries and who now relieves me from all the dirty work of the laboratory.In his letters, Henry described Parker providing materials for experiments, fixing technical issues with Henry's equipment, and at times being used as a test subject in electrical experiments in which Henry and his students would shock Parker in classroom demonstrations. In 1842, when Parker fell ill, Henry's experiments stopped completely until he recovered. Henry was appointed the first Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution in 1846, and served in this capacity until 1878. In 1848, while Secretary, Henry worked in conjunction with Professor Stephen Alexander to determine the relative temperatures for different parts of the solar disk. They used a thermopile to determine that sunspots were cooler than the surrounding regions. This work was shown to the astronomer Angelo Secchi who extended it, but with some question as to whether Henry was given proper credit for his earlier work. In late 1861 and early 1862, during the

American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and t ...

, Henry oversaw a series of lectures by prominent abolitionists

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery. In Western Europe and the Americas, abolitionism was a historic movement that sought to end the Atlantic slave trade and liberate the enslaved people.

The Britis ...

at the Smithsonian Institution. Speakers included white clergymen, politicians, and activists such as Wendell Phillips, Horace Greeley

Horace Greeley (February 3, 1811 – November 29, 1872) was an American newspaper editor and publisher who was the founder and editor of the '' New-York Tribune''. Long active in politics, he served briefly as a congressman from New York ...

, Henry Ward Beecher, and Ralph Waldo Emerson

Ralph Waldo Emerson (May 25, 1803April 27, 1882), who went by his middle name Waldo, was an American essayist, lecturer, philosopher, abolitionist, and poet who led the transcendentalist movement of the mid-19th century. He was seen as a cham ...

. Famous orator and former fugitive slave Frederick Douglass

Frederick Douglass (born Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey, February 1817 or 1818 – February 20, 1895) was an American social reformer, abolitionist, orator, writer, and statesman. After escaping from slavery in Maryland, he became ...

was scheduled as the final speaker; Henry, however, refused to allow him to attend, stating: "I would not let the lecture of the coloured man be given in the rooms of the Smithsonian."

In the fall of 2014 history author Jeremy T.K. Farley released ''The Civil War Out My Window: Diary of Mary Henry''. The 262-page book featured the diary of Henry's daughter Mary, from the years of 1855 to 1878. Throughout the diary, Henry is repeatedly mentioned by his daughter, who showed a keen affection to her father.

Influences in aeronautics

Prof. Henry was introduced to Prof. Thaddeus Lowe, a balloonist from New Hampshire who had taken interest in the phenomenon of lighter-than-air gases, and exploits into meteorology, in particular, the high winds which we call theJet stream

Jet streams are fast flowing, narrow, meandering air currents in the atmospheres of some planets, including Earth. On Earth, the main jet streams are located near the altitude of the tropopause and are westerly winds (flowing west to east) ...

today. It was Lowe's intent to make a transatlantic crossing by utilizing an enormous gas-inflated aerostat. Henry took a great interest in Lowe's endeavors, promoting him among some of the more prominent scientists and institutions of the day.

In June 1860, Lowe had made a successful test flight with his gigantic balloon, first named the ''City of New York'' and later renamed ''The Great Western'', flying from Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Since ...

to Medford, New York

Medford is a hamlet and census-designated place (CDP) in the Town of Brookhaven in Suffolk County, on Long Island, in New York, United States. The population was 24,142 at the 2010 census.

History

The Long Island Rail Road established the Medf ...

. Lowe would not be able to attempt a transatlantic flight until late Spring of the 1861, so Henry convinced him to take his balloon to a point more West and fly the balloon back to the eastern seaboard, an exercise that would keep his investors interested.

Lowe took several smaller balloons to Cincinnati, Ohio

Cincinnati ( ) is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Hamilton County. Settled in 1788, the city is located at the northern side of the confluence of the Licking and Ohio rivers, the latter of which marks the state line w ...

in March 1861. On 19 April, he launched on a fateful flight that landed him in Confederate South Carolina. With the Southern States seceding from the Union, during that winter and spring of 1861, and the onset of Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government polici ...

, Lowe abandoned further attempts at a trans-Atlantic crossing and, with Henry's endorsement, went to Washington, D.C. to offer his services as an aeronaut to the Federal government. Henry submitted a letter to U.S. Secretary of War at the time Simon Cameron of Pennsylvania which carried Henry's endorsement:

On Henry's recommendation Lowe went on to form the United States Army/"Union Army" Balloon Corps and served two years with the Army of the Potomac

The Army of the Potomac was the principal Union Army in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War. It was created in July 1861 shortly after the First Battle of Bull Run and was disbanded in June 1865 following the surrender of the Confede ...

as a Civil War "Aeronaut".

Later years

As a famous scientist and director of the Smithsonian Institution, Henry received visits from other scientists and inventors who sought his advice. Henry was patient, kindly, self-controlled, and gently humorous. One such visitor was

As a famous scientist and director of the Smithsonian Institution, Henry received visits from other scientists and inventors who sought his advice. Henry was patient, kindly, self-controlled, and gently humorous. One such visitor was Alexander Graham Bell

Alexander Graham Bell (, born Alexander Bell; March 3, 1847 – August 2, 1922) was a Scottish-born inventor, scientist and engineer who is credited with patenting the first practical telephone. He also co-founded the American Telephone and T ...

, who on 1 March 1875 carried a letter of introduction to Henry. Henry showed an interest in seeing Bell's experimental apparatus, and Bell returned the following day. After the demonstration, Bell mentioned his untested theory on how to transmit human speech electrically by means of a "harp apparatus" which would have several steel reeds tuned to different frequencies to cover the voice spectrum. Henry said Bell had "the germ of a great invention". Henry advised Bell not to publish his ideas until he had perfected the invention. When Bell objected that he lacked the necessary knowledge, Henry firmly advised: "Get it!"

On 25 June 1876, Bell's experimental telephone (using a different design) was demonstrated at the Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia where Henry was one of the judges for electrical exhibits. On 13 January 1877, Bell demonstrated his instruments to Henry at the Smithsonian Institution and Henry invited Bell to demonstrate them again that night at the Washington Philosophical Society. Henry praised "the value and astonishing character of Mr. Bell's discovery and invention."

Henry died on 13 May 1878, and was buried in Oak Hill Cemetery in the Georgetown section of northwest Washington, D.C. John Phillips Sousa wrote the Transit of Venus March for the unveiling of the Joseph Henry statue in front of the Smithsonian Castle

The Smithsonian Institution Building, located near the National Mall in Washington, D.C. behind the National Museum of African Art and the Sackler Gallery, houses the Smithsonian Institution's administrative offices and information center. The ...

.

Legacy

Henry was a member of the United States Lighthouse Board from 1852 until his death. He was appointed chairman in 1871 and served in that position the remainder of his life. He was the only civilian to serve as chairman. TheUnited States Coast Guard

The United States Coast Guard (USCG) is the maritime security, search and rescue, and law enforcement service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the country's eight uniformed services. The service is a maritime, military, m ...

honored Henry for his work on lighthouses and fog signal acoustics by naming a cutter after him. The '' Joseph Henry'', usually referred to as the ''Joe Henry'', was launched in 1880 and was active until 1904.US Coast Guard Cutter Joseph Henry/ref> In 1915 Henry was inducted into the

Hall of Fame for Great Americans

The Hall of Fame for Great Americans is an outdoor sculpture gallery located on the grounds of Bronx Community College (BCC) in the Bronx, New York City. It is the first such hall of fame in the United States. Built in 1901 as part of the ...

in the Bronx, New York.

Bronze statues of Henry and Isaac Newton

Sir Isaac Newton (25 December 1642 – 20 March 1726/27) was an English mathematician, physicist, astronomer, alchemist, Theology, theologian, and author (described in his time as a "natural philosophy, natural philosopher"), widely ...

represent science on the balustrade of the galleries of the Main Reading Room in the Thomas Jefferson Building

The Thomas Jefferson Building is the oldest of the four United States Library of Congress buildings. Built between 1890 and 1897, it was originally known as the Library of Congress Building. It is now named for the 3rd U.S. president Thomas Jef ...

of the Library of Congress

The Library of Congress (LOC) is the research library that officially serves the United States Congress and is the ''de facto'' national library of the United States. It is the oldest federal cultural institution in the country. The libra ...

on Capitol Hill

Capitol Hill, in addition to being a metonym for the United States Congress, is the largest historic residential neighborhood in Washington, D.C., stretching easterly in front of the United States Capitol along wide avenues. It is one of the ...

in Washington, D.C. They are two of the 16 historical figures depicted in the reading room, each pair representing one of the 8 pillars of civilization.

In 1872 John Wesley Powell

John Wesley Powell (March 24, 1834 – September 23, 1902) was an American geologist, U.S. Army soldier, explorer of the American West, professor at Illinois Wesleyan University, and director of major scientific and cultural institutions. H ...

named a mountain range in southeastern Utah after Henry. The Henry Mountains were the last mountain range to be added to the map of the 48 contiguous U.S. states.

At Princeton

Princeton University is a private research university in Princeton, New Jersey. Founded in 1746 in Elizabeth as the College of New Jersey, Princeton is the fourth-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and one of the nin ...

, the Joseph Henry Laboratories and the Joseph Henry House are named for him.

After the Albany Academy moved out of its downtown building in the early 1930s, its old building in Academy Park was renamed Joseph Henry Memorial, with a statue of him out front. It is now the main offices of the Albany City School District. In 1971 it was listed on the National Register of Historic Places

The National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) is the United States federal government's official list of districts, sites, buildings, structures and objects deemed worthy of preservation for their historical significance or "great artistic ...

; later it was included as a contributing property when the Lafayette Park Historic District

The Lafayette Park Historic District is located in central Albany, New York, United States. It includes the park and the combination of large government buildings and small rowhouses on the neighboring streets. In 1978 it was recognized as a hi ...

was listed on the Register.

Curriculum vitae

*1826 – Professor of mathematics and natural philosophy at

*1826 – Professor of mathematics and natural philosophy at The Albany Academy

The Albany Academy is an independent college preparatory day school for boys in Albany, New York, USA, enrolling students from Preschool (age 3) to Grade 12. It was established in 1813 by a charter signed by Mayor Philip Schuyler Van Rensselae ...

, New York.

*1832 – Chair of Natural History at Princeton University (then the College of New Jersey) until 1846

*1835 – Invented the electromechanical relay

A relay

Electromechanical relay schematic showing a control coil, four pairs of normally open and one pair of normally closed contacts

An automotive-style miniature relay with the dust cover taken off

A relay is an electrically operated switch ...

.

*1846 – First secretary of the Smithsonian Institution

The Smithsonian Institution ( ), or simply the Smithsonian, is a group of museums and education and research centers, the largest such complex in the world, created by the U.S. government "for the increase and diffusion of knowledge". Found ...

until 1878

*1848 – Edited Ephraim G. Squier and Edwin H. Davis' '' Ancient Monuments of the Mississippi Valley'', the Institution's first publication.

*1852 – Appointed to the Lighthouse Board

*1871 – Appointed chairman of the Lighthouse Board

Other honors

300px, A bronze statue of Henry stands on the rotunda of the U.S. Library of Congress. Elected a member of theAmerican Philosophical Society

The American Philosophical Society (APS), founded in 1743 in Philadelphia, is a scholarly organization that promotes knowledge in the sciences and humanities through research, professional meetings, publications, library resources, and communit ...

in 1835 and American Antiquarian Society

The American Antiquarian Society (AAS), located in Worcester, Massachusetts, is both a learned society and a national research library of pre-twentieth-century American history and culture. Founded in 1812, it is the oldest historical society i ...

in 1851.

The District of Columbia named a school, built in 1878–80, on P Street between 6th and 7th the Joseph Henry School. It was demolished at some point after 1932.

The Henry Mountains (Utah

Utah ( , ) is a state in the Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. Utah is a landlocked U.S. state bordered to its east by Colorado, to its northeast by Wyoming, to its north by Idaho, to its south by Arizona, and to its ...

) had been so named by geologist Almon Thompson in his honour.

Mount Henry in California is named in his honor.

See also

*Electromagnetism

In physics, electromagnetism is an interaction that occurs between particles with electric charge. It is the second-strongest of the four fundamental interactions, after the strong force, and it is the dominant force in the interactions o ...

* Henry (unit)

* Multiple coil magnet

* Timeline of historic inventions

The timeline of historic inventions is a chronological list of particularly important or significant technological inventions and their inventors, where known.

Paleolithic

The dates listed in this section refer to the earliest evidence of an i ...

* Timeline of communication technology

The history of communication technologies (media and appropriate inscription tools) have evolved in tandem with shifts in political and economic systems, and by extension, systems of power. Communication can range from very subtle processes of exc ...

* American Philosophical Society

The American Philosophical Society (APS), founded in 1743 in Philadelphia, is a scholarly organization that promotes knowledge in the sciences and humanities through research, professional meetings, publications, library resources, and communit ...

* History of Albany, New York

* Daniel Davis Jr. - electrical device inventor

References

Further reading

* Ames, Joseph Sweetman (Ed.), ''The discovery of induced electric currents'', Vol. 1. Memoirs, by Joseph Henry. New York, Cincinnati tc.American book company 1900LCCN 00005889 * Coulson, Thomas, ''Joseph Henry: His Life and Work'', Princeton, Princeton University Press, 1950 * Dorman, Kathleen W., and Sarah J. Shoenfeld (comps.), ''The Papers of Joseph Henry. Volume 12: Cumulative Index,'' Science History Publications, 2008 * Henry, Joseph, ''Scientific Writings of Joseph Henry. Volumes 1 and 2'', Smithsonian Institution, 1886 * Moyer, Albert E., ''Joseph Henry: The Rise of an American Scientist,'' Washington, Smithsonian Institution Press, 1997. * Reingold, Nathan, et al., (eds.), ''The Papers of Joseph Henry. Volumes 1-5,'' Washington, Smithsonian Institution Press, 1972–1988 * Rothenberg, Marc, et al., (eds.), ''The Papers of Joseph Henry. Volumes 6-8,'' Washington, Smithsonian Institution Press, 1992–1998, and ''Volumes 9-11,'' Science History Publications, 2002–2007External links

* Finding aid to thJoseph Henry collection

at th

University of Pennsylvania Libraries

Biographical details

— ''Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences'' (1967), 58(1), pp. 1–10.

Dedication ceremony for the Henry statue (1883)

Published physics papers

— ''On the Production of Currents and Sparks of Electricity from Magnetism'' and ''On Electro-Dynamic Induction (extract)''

Joseph Henry Collection, Smithsonian Institution

{{DEFAULTSORT:Henry, Joseph 1797 births 1878 deaths American physicists People from Albany, New York People associated with electricity American people of Scottish descent Secretaries of the Smithsonian Institution Burials at Oak Hill Cemetery (Washington, D.C.) People from Galway, New York Hall of Fame for Great Americans inductees Members of the American Antiquarian Society Scientists from New York (state) The Albany Academy alumni