John of the Cross on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

John of the Cross, OCD ( es, link=no, Juan de la Cruz; la, Ioannes a Cruce; born Juan de Yepes y Álvarez; 24 June 1542 – 14 December 1591) was a Spanish

He was born Juan de Yepes y Álvarez at Fontiveros,

He was born Juan de Yepes y Álvarez at Fontiveros,

John was

John was

Catholic priest

The priesthood is the office of the ministers of religion, who have been commissioned (" ordained") with the Holy orders of the Catholic Church. Technically, bishops are a priestly order as well; however, in layman's terms ''priest'' refers onl ...

, mystic, and a Carmelite

, image =

, caption = Coat of arms of the Carmelites

, abbreviation = OCarm

, formation = Late 12th century

, founder = Early hermits of Mount Carmel

, founding_location = Mount Ca ...

friar

A friar is a member of one of the mendicant orders founded in the twelfth or thirteenth century; the term distinguishes the mendicants' itinerant apostolic character, exercised broadly under the jurisdiction of a superior general, from the ...

of converso

A ''converso'' (; ; feminine form ''conversa''), "convert", () was a Jew who converted to Catholicism in Spain or Portugal, particularly during the 14th and 15th centuries, or one of his or her descendants.

To safeguard the Old Christian p ...

origin. He is a major figure of the Counter-Reformation

The Counter-Reformation (), also called the Catholic Reformation () or the Catholic Revival, was the period of Catholic resurgence that was initiated in response to the Protestant Reformation. It began with the Council of Trent (1545–1563) a ...

in Spain, and he is one of the thirty-seven Doctors of the Church.

John of the Cross is known for his writings. He was mentored by and corresponded with the older Carmelite, Teresa of Ávila

Teresa of Ávila, OCD (born Teresa Sánchez de Cepeda y Ahumada; 28 March 15154 or 15 October 1582), also called Saint Teresa of Jesus, was a Spanish Carmelite nun and prominent Spanish mystic and religious reformer.

Active during t ...

. Both his poetry and his studies on the development of the soul

In many religious and philosophical traditions, there is a belief that a soul is "the immaterial aspect or essence of a human being".

Etymology

The Modern English noun '' soul'' is derived from Old English ''sāwol, sāwel''. The earliest att ...

are considered the summit of mystical

Mysticism is popularly known as becoming one with God or the Absolute, but may refer to any kind of ecstasy or altered state of consciousness which is given a religious or spiritual meaning. It may also refer to the attainment of insight in u ...

Spanish literature and among the greatest works of all Spanish literature

Spanish literature generally refers to literature (Spanish poetry, prose, and drama) written in the Spanish language within the territory that presently constitutes the Kingdom of Spain. Its development coincides and frequently intersects w ...

. He was canonized

Canonization is the declaration of a deceased person as an officially recognized saint, specifically, the official act of a Christian communion declaring a person worthy of public veneration and entering their name in the canon catalogue of s ...

by Pope Benedict XIII

Pope Benedict XIII ( la, Benedictus XIII; it, Benedetto XIII; 2 February 1649 – 21 February 1730), born Pietro Francesco Orsini and later called Vincenzo Maria Orsini, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 29 May ...

in 1726. In 1926, he was declared a Doctor of the Church by Pope Pius XI

Pope Pius XI ( it, Pio XI), born Ambrogio Damiano Achille Ratti (; 31 May 1857 – 10 February 1939), was head of the Catholic Church from 6 February 1922 to his death in February 1939. He was the first sovereign of Vatican City f ...

, and is also known as the "mystical doctor".

Life

Early life and education

Old Castile

Old Castile ( es, Castilla la Vieja ) is a historic region of Spain, which had different definitions along the centuries. Its extension was formally defined in the 1833 territorial division of Spain as the sum of the following provinces: Sant ...

into a converso

A ''converso'' (; ; feminine form ''conversa''), "convert", () was a Jew who converted to Catholicism in Spain or Portugal, particularly during the 14th and 15th centuries, or one of his or her descendants.

To safeguard the Old Christian p ...

family (descendants of Jewish converts to Catholicism) in Fontiveros, near Ávila

Ávila (, , ) is a city of Spain located in the autonomous community of Castile and León. It is the capital and most populated municipality of the Province of Ávila.

It lies on the right bank of the Adaja river. Located more than 1,130 m ab ...

, a town of around 2,000 people. His father, Gonzalo, was an accountant to richer relatives who were silk merchants. In 1529 Gonzalo married John's mother, Catalina, who was an orphan of a lower class; he was rejected by his family and forced to work with his wife as a weaver. John's father died in 1545, while John was still only around three years old. Two years later, John's older brother, Luis, died, probably as a result of malnourishment due to the poverty to which the family had been reduced. As a result, John's mother Catalina took John and his surviving brother Francisco, first to Arévalo, in 1548 and then in 1551 to Medina del Campo

Medina del Campo is a town and municipality of Spain located in the autonomous community of Castile and León. Part of the Province of Valladolid, it is the centre of a farming area.

History

Medina del Campo grew in importance thanks to its fairs ...

, where she was able to find work.

In Medina, John entered a school for 160 poor children, mostly orphans, to receive a basic education, mainly in Christian doctrine. They were given some food, clothing and lodging. While studying there, he was chosen to serve as an altar boy at a nearby monastery of Augustinian nuns. Growing up, John worked at a hospital and studied the humanities at a Jesuit

, image = Ihs-logo.svg

, image_size = 175px

, caption = ChristogramOfficial seal of the Jesuits

, abbreviation = SJ

, nickname = Jesuits

, formation =

, founders ...

school from 1559 to 1563. The Society of Jesus was at that time a new organisation, having been founded only a few years earlier by the Spaniard St. Ignatius of Loyola

Ignatius of Loyola, S.J. (born Íñigo López de Oñaz y Loyola; eu, Ignazio Loiolakoa; es, Ignacio de Loyola; la, Ignatius de Loyola; – 31 July 1556), venerated as Saint Ignatius of Loyola, was a Spanish Catholic priest and theologian ...

. In 1563 he entered the Carmelite Order, adopting the name John of St. Matthias.

The following year, in 1564 he made his First Profession as a Carmelite and travelled to Salamanca

Salamanca () is a city in western Spain and is the capital of the Province of Salamanca in the autonomous community of Castile and León. The city lies on several rolling hills by the Tormes River. Its Old City was declared a UNESCO World Herit ...

University, where he studied theology and philosophy. There he met Fray Luis de León

Fray or Frays or The Fray may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media

Fictional entities

*Fray, a phenomenon in Terry Pratchett's '' The Carpet People''

*Fray, the main character in the video games:

**''Fray in Magical Adventure''

**''Fray CD' ...

, who taught biblical studies (Exegesis

Exegesis ( ; from the Greek , from , "to lead out") is a critical explanation or interpretation of a text. The term is traditionally applied to the interpretation of Biblical works. In modern usage, exegesis can involve critical interpretation ...

, Hebrew

Hebrew (; ; ) is a Northwest Semitic language of the Afroasiatic language family. Historically, it is one of the spoken languages of the Israelites and their longest-surviving descendants, the Jews and Samaritans. It was largely preserved ...

and Aramaic

The Aramaic languages, short Aramaic ( syc, ܐܪܡܝܐ, Arāmāyā; oar, 𐤀𐤓𐤌𐤉𐤀; arc, 𐡀𐡓𐡌𐡉𐡀; tmr, אֲרָמִית), are a language family containing many varieties (languages and dialects) that originated i ...

) at the university.

Joining the Reform of Teresa of Ávila

ordained

Ordination is the process by which individuals are consecrated, that is, set apart and elevated from the laity class to the clergy, who are thus then authorized (usually by the denominational hierarchy composed of other clergy) to perform ...

as a priest in 1567. He subsequently thought about joining the strict Carthusian

The Carthusians, also known as the Order of Carthusians ( la, Ordo Cartusiensis), are a Latin enclosed religious order of the Catholic Church. The order was founded by Bruno of Cologne in 1084 and includes both monks and nuns. The order has i ...

Order, which appealed to him because of its practice of solitary and silent contemplation. His journey from Salamanca to Medina del Campo

Medina del Campo is a town and municipality of Spain located in the autonomous community of Castile and León. Part of the Province of Valladolid, it is the centre of a farming area.

History

Medina del Campo grew in importance thanks to its fairs ...

, probably in September 1567 became pivotal. In Medina he met the influential Carmelite nun, Teresa of Ávila

Teresa of Ávila, OCD (born Teresa Sánchez de Cepeda y Ahumada; 28 March 15154 or 15 October 1582), also called Saint Teresa of Jesus, was a Spanish Carmelite nun and prominent Spanish mystic and religious reformer.

Active during t ...

. She was staying in Medina to found the second of her new convents. She immediately talked to him about her reformation projects for the Order: she was seeking to restore the purity of the Carmelite Order by reverting to the observance of its "Primitive Rule" of 1209, which had been relaxed by Pope Eugene IV

Pope Eugene IV ( la, Eugenius IV; it, Eugenio IV; 1383 – 23 February 1447), born Gabriele Condulmer, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 3 March 1431 to his death in February 1447. Condulmer was a Venetian, and ...

in 1432.

Under the Rule, much of the day and night were to be divided between the recitation of the Liturgy of the Hours

The Liturgy of the Hours (Latin: ''Liturgia Horarum'') or Divine Office (Latin: ''Officium Divinum'') or ''Opus Dei'' ("Work of God") are a set of Catholic prayers comprising the canonical hours, often also referred to as the breviary, of the ...

, study and devotional reading, the celebration of Mass and periods of solitude. In the case of friars, time was to be spent evangelizing the population around the monastery. There was to be total abstinence

Abstinence is a self-enforced restraint from indulging in bodily activities that are widely experienced as giving pleasure. Most frequently, the term refers to sexual abstinence, but it can also mean abstinence from alcohol, drugs, food, etc.

...

from meat and a lengthy period of fasting

Fasting is the abstention from eating and sometimes drinking. From a purely physiological context, "fasting" may refer to the metabolic status of a person who has not eaten overnight (see " Breakfast"), or to the metabolic state achieved after ...

from the Feast of the Exaltation of the Cross (14 September) until Easter. There were to be long periods of silence, especially between Compline

Compline ( ), also known as Complin, Night Prayer, or the Prayers at the End of the Day, is the final prayer service (or office) of the day in the Christian tradition of canonical hours, which are prayed at fixed prayer times.

The English ...

and Prime

A prime number (or a prime) is a natural number greater than 1 that is not a product of two smaller natural numbers. A natural number greater than 1 that is not prime is called a composite number. For example, 5 is prime because the only ways ...

. More simple, that is coarser, shorter habits were to be adopted. There was also an injunction

An injunction is a legal and equitable remedy in the form of a special court order that compels a party to do or refrain from specific acts. ("The court of appeals ... has exclusive jurisdiction to enjoin, set aside, suspend (in whole or in p ...

against wearing covered shoes (also previously mitigated in 1432). That particular observance distinguished the "discalced

A discalced congregation is a religious congregation that goes barefoot or wears sandals. These congregations are often distinguished on this account from other branches of the same order. The custom of going unshod was introduced into the West b ...

", i.e., barefoot followers of Teresa from traditional Carmelites, and they would be formally recognized as the separate ''Order of Discalced Carmelites

The Discalced Carmelites, known officially as the Order of the Discalced Carmelites of the Blessed Virgin Mary of Mount Carmel ( la, Ordo Fratrum Carmelitarum Discalceatorum Beatae Mariae Virginis de Monte Carmelo) or the Order of Discalced Carme ...

'' in 1580.

Teresa asked John to delay his entry into the Carthusian order and to follow her. Having spent a final year studying in Salamanca, in August 1568 John travelled with Teresa from Medina to Valladolid

Valladolid () is a municipality in Spain and the primary seat of government and de facto capital of the autonomous community of Castile and León. It is also the capital of the province of the same name. It has a population around 300,000 peop ...

, where Teresa intended to found another convent. After a spell at Teresa's side in Valladolid, learning more about the new form of Carmelite life, in October 1568, John left Valladolid, accompanied by Friar Antonio de Jesús de Heredia, to found a new monastery for Carmelite friars, the first to follow Teresa's principles. They were given the use of a derelict house at Duruelo, which had been donated to Teresa. On 28 November 1568, the monastery was established, and on that same day, John changed his name to "John of the Cross".

Soon after, in June 1570, the friars found the house at Duruelo was too small, and so moved to the nearby town of Mancera de Abajo, midway between Ávila and Salamanca. John moved from the first community to set up a new community at Pastrana Pastrana may refer to:

* Pastrana (musical)

''Pastrana'' is an Australian musical by Allan McFadden and Peter Northwood. It is based on the true 19th century story of Julia Pastrana, a Mexican woman who was born with canine-like teeth and a th ...

in October 1570, and then a further community at Alcalá de Henares

Alcalá de Henares () is a Spanish city in the Community of Madrid. Straddling the Henares River, it is located to the northeast of the centre of Madrid. , it has a population of 193,751, making it the region's third-most populated municipality ...

, as a house for the academic training of the friars. In 1572 he arrived in Ávila, at Teresa's invitation. She had been appointed prior

Prior (or prioress) is an ecclesiastical title for a superior in some religious orders. The word is derived from the Latin for "earlier" or "first". Its earlier generic usage referred to any monastic superior. In abbeys, a prior would be low ...

ess of the Convent of the Incarnation there in 1571. John became the spiritual director

Spiritual direction is the practice of being with people as they attempt to deepen their relationship with the divine, or to learn and grow in their personal spirituality. The person seeking direction shares stories of their encounters of the di ...

and confessor

Confessor is a title used within Christianity in several ways.

Confessor of the Faith

Its oldest use is to indicate a saint who has suffered persecution and torture for the faith but not to the point of death. In 1574, John accompanied Teresa for the foundation of a new religious community in  At some time between 1574 and 1577, while praying in a loft overlooking the sanctuary in the Monastery of the Incarnation in Ávila, John had a vision of the crucified Christ, which led him to create his drawing of Christ "from above". In 1641, this drawing was placed in a small

At some time between 1574 and 1577, while praying in a loft overlooking the sanctuary in the Monastery of the Incarnation in Ávila, John had a vision of the crucified Christ, which led him to create his drawing of Christ "from above". In 1641, this drawing was placed in a small

Segovia

Segovia ( , , ) is a city in the autonomous community of Castile and León, Spain. It is the capital and most populated municipality of the Province of Segovia.

Segovia is in the Inner Plateau ('' Meseta central''), near the northern slopes of t ...

, returning to Ávila after staying there a week. Aside from the one trip, John seems to have remained in Ávila between 1572 and 1577.

At some time between 1574 and 1577, while praying in a loft overlooking the sanctuary in the Monastery of the Incarnation in Ávila, John had a vision of the crucified Christ, which led him to create his drawing of Christ "from above". In 1641, this drawing was placed in a small

At some time between 1574 and 1577, while praying in a loft overlooking the sanctuary in the Monastery of the Incarnation in Ávila, John had a vision of the crucified Christ, which led him to create his drawing of Christ "from above". In 1641, this drawing was placed in a small monstrance

A monstrance, also known as an ostensorium (or an ostensory), is a vessel used in Roman Catholic, Old Catholic, High Church Lutheran and Anglican churches for the display on an altar of some object of piety, such as the consecrated Eucharistic ...

and kept in Ávila. This same drawing inspired the artist Salvador Dalí

Salvador Domingo Felipe Jacinto Dalí i Domènech, Marquess of Dalí of Púbol (; ; ; 11 May 190423 January 1989) was a Spanish Surrealism, surrealist artist renowned for his technical skill, precise draftsmanship, and the striking and bizarr ...

's 1951 work '' Christ of Saint John of the Cross''.

Height of Carmelite tensions

The years 1575–77 saw a great increase in tensions among Spanish Carmelite friars over the reforms of Teresa and John. Since 1566 the reforms had been overseen by Canonical Visitors from theDominican Order

The Order of Preachers ( la, Ordo Praedicatorum) abbreviated OP, also known as the Dominicans, is a Catholic mendicant order of Pontifical Right for men founded in Toulouse, France, by the Spanish priest, saint and mystic Dominic of ...

, with one appointed to Castile and a second to Andalusia

Andalusia (, ; es, Andalucía ) is the southernmost autonomous community in Peninsular Spain. It is the most populous and the second-largest autonomous community in the country. It is officially recognised as a "historical nationality". The ...

. The Visitors had substantial powers: they could move members of religious communities from one house to another or from one province

A province is almost always an administrative division within a country or state. The term derives from the ancient Roman ''provincia'', which was the major territorial and administrative unit of the Roman Empire's territorial possessions out ...

to the next. They could assist religious superior

In a hierarchy or tree structure of any kind, a superior is an individual or position at a higher level in the hierarchy than another (a "subordinate" or "inferior"), and thus closer to the apex. In business, superiors are people who are superv ...

s in the discharge of their office, and could delegate superiors between the Dominican or Carmelite orders. In Castile, the Visitor was Pedro Fernández, who prudently balanced the interests of the Discalced Carmelites with those of the nuns and friars who did not desire reform.

In Andalusia to the south, the Visitor was Francisco Vargas, and tensions rose due to his clear preference for the Discalced friars. Vargas asked them to make foundations in various cities, in contradiction to the express orders from the Carmelite Prior General

Prior (or prioress) is an ecclesiastical title for a superior in some religious orders. The word is derived from the Latin for "earlier" or "first". Its earlier generic usage referred to any monastic superior. In abbeys, a prior would be lowe ...

to curb expansion in Andalusia. As a result, a General Chapter

A chapter ( la, capitulum or ') is one of several bodies of clergy in Roman Catholic, Old Catholic, Anglican, and Nordic Lutheran churches or their gatherings.

Name

The name derives from the habit of convening monks or canons for the re ...

of the Carmelite Order was convened at Piacenza

Piacenza (; egl, label= Piacentino, Piaṡëinsa ; ) is a city and in the Emilia-Romagna region of northern Italy, and the capital of the eponymous province. As of 2022, Piacenza is the ninth largest city in the region by population, with over ...

in Italy in May 1576, out of concern that events in Spain were getting out of hand. It concluded by ordering the total suppression of the Discalced houses.

That measure was not immediately enforced. King Philip II of Spain

Philip II) in Spain, while in Portugal and his Italian kingdoms he ruled as Philip I ( pt, Filipe I). (21 May 152713 September 1598), also known as Philip the Prudent ( es, Felipe el Prudente), was King of Spain from 1556, King of Portugal from ...

was supportive of Teresa's reforms, and so was not immediately willing to grant the necessary permission to enforce the ordinance. The Discalced friars also found support from the papal nuncio

An apostolic nuncio ( la, nuntius apostolicus; also known as a papal nuncio or simply as a nuncio) is an ecclesiastical diplomat, serving as an envoy or a permanent diplomatic representative of the Holy See to a state or to an international ...

to Spain, , Bishop of Padua

The Roman Catholic Diocese of Padua ( it, Diocesi di Padova; la, Dioecesis Patavina) is an episcopal see of the Catholic Church in Veneto, northern Italy. It was erected in the 3rd century.Jerónimo Gracián, a priest from the

On the night of 2 December 1577, a group of Carmelites opposed to reform broke into John's dwelling in Ávila and took him prisoner. John had received an order from superiors, opposed to reform, to leave Ávila and return to his original house. John had refused on the basis that his reform work had been approved by the papal nuncio to Spain, a higher authority than these superiors.

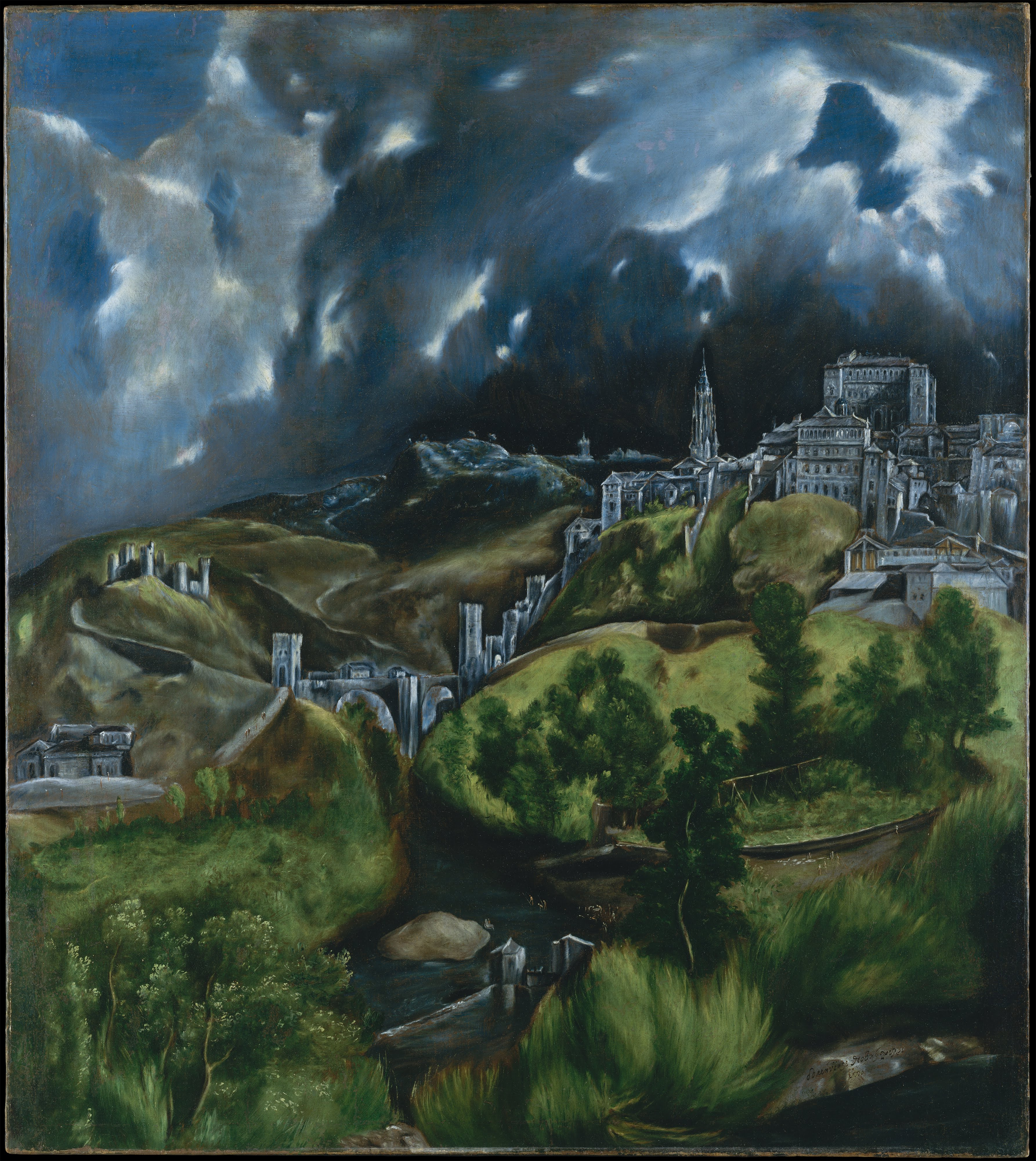

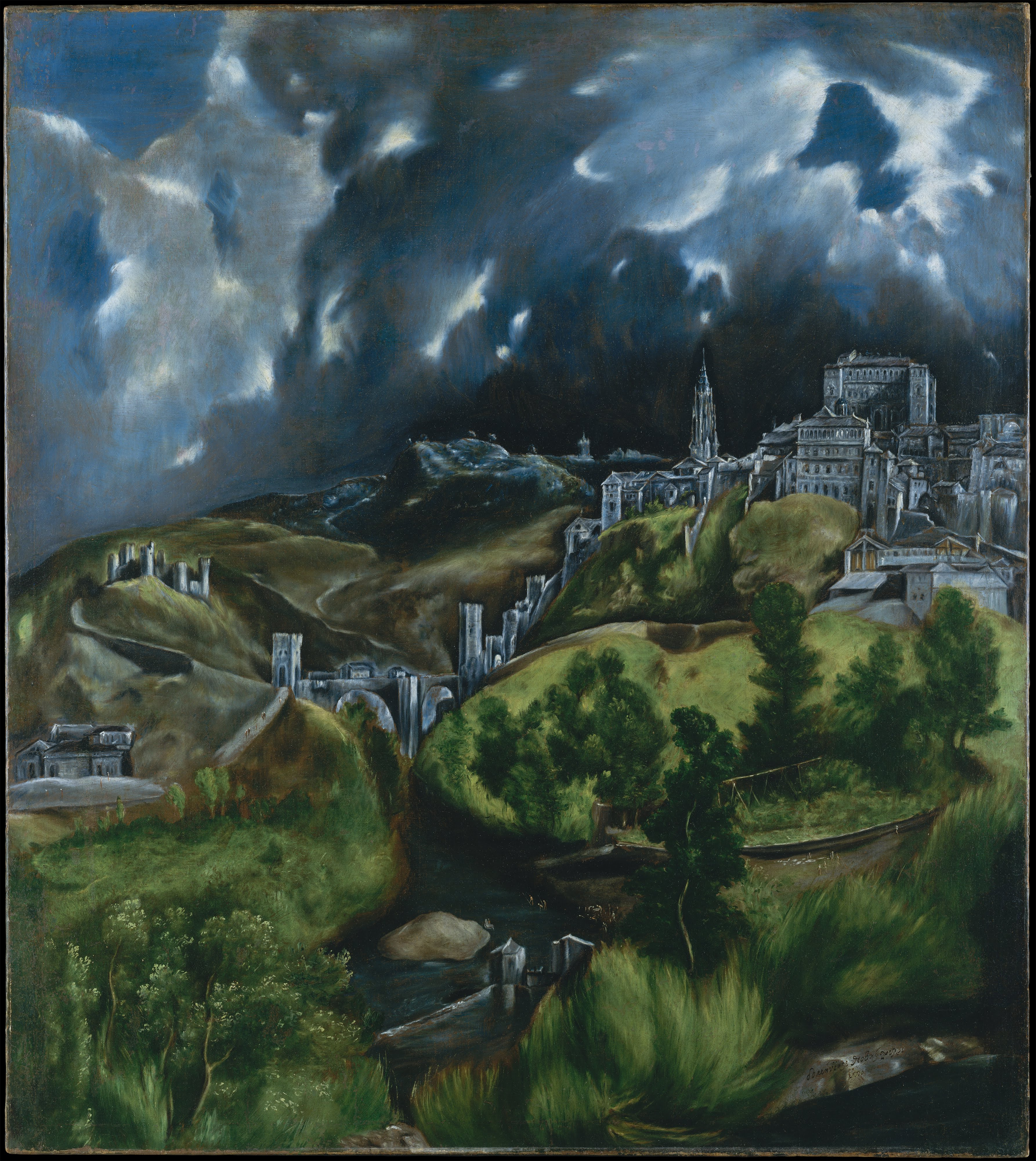

, pages = 10,11 The Carmelites therefore took John captive. John was taken from Ávila to the Carmelite monastery in Toledo, at that time the order's leading monastery in Castile, with a community of 40 friars.

John was brought before a court of friars, accused of disobeying the ordinances of Piacenza. Despite his argument that he had not disobeyed the ordinances, he was sentenced to a term of imprisonment. He was jailed in a monastery where he was kept under a brutal regime that included public lashings before the community at least weekly, and severe isolation in a tiny stifling cell measuring barely 10 feet by 6 feet. Except when rarely permitted an oil lamp, he had to stand on a bench to read his

On the night of 2 December 1577, a group of Carmelites opposed to reform broke into John's dwelling in Ávila and took him prisoner. John had received an order from superiors, opposed to reform, to leave Ávila and return to his original house. John had refused on the basis that his reform work had been approved by the papal nuncio to Spain, a higher authority than these superiors.

, pages = 10,11 The Carmelites therefore took John captive. John was taken from Ávila to the Carmelite monastery in Toledo, at that time the order's leading monastery in Castile, with a community of 40 friars.

John was brought before a court of friars, accused of disobeying the ordinances of Piacenza. Despite his argument that he had not disobeyed the ordinances, he was sentenced to a term of imprisonment. He was jailed in a monastery where he was kept under a brutal regime that included public lashings before the community at least weekly, and severe isolation in a tiny stifling cell measuring barely 10 feet by 6 feet. Except when rarely permitted an oil lamp, he had to stand on a bench to read his

In November 1581, John was sent by Teresa to help Ana de Jesús to found a convent in

In November 1581, John was sent by Teresa to help Ana de Jesús to found a convent in

John of the Cross is considered one of the foremost poets in Spanish. Although his complete poems add up to fewer than 2500 verses, two of them, the ''

John of the Cross is considered one of the foremost poets in Spanish. Although his complete poems add up to fewer than 2500 verses, two of them, the ''

University of Alcalá

The University of Alcalá ( es, Universidad de Alcalá) is a public university located in Alcalá de Henares, a city 35 km (22 miles) northeast of Madrid in Spain and also the third-largest city of the region. It was founded in 1293 as a ...

, who was in fact a Discalced Carmelite friar himself. The nuncio's protection helped John avoid problems for a time. In January 1576, John was detained in Medina del Campo by traditional Carmelite friars, but through the nuncio's intervention, he was soon released. When Ormaneto died on 18 June 1577, John was left without protection, and the friars opposing his reforms regained the upper hand.

Foundations, imprisonment, torture and death

On the night of 2 December 1577, a group of Carmelites opposed to reform broke into John's dwelling in Ávila and took him prisoner. John had received an order from superiors, opposed to reform, to leave Ávila and return to his original house. John had refused on the basis that his reform work had been approved by the papal nuncio to Spain, a higher authority than these superiors.

, pages = 10,11 The Carmelites therefore took John captive. John was taken from Ávila to the Carmelite monastery in Toledo, at that time the order's leading monastery in Castile, with a community of 40 friars.

John was brought before a court of friars, accused of disobeying the ordinances of Piacenza. Despite his argument that he had not disobeyed the ordinances, he was sentenced to a term of imprisonment. He was jailed in a monastery where he was kept under a brutal regime that included public lashings before the community at least weekly, and severe isolation in a tiny stifling cell measuring barely 10 feet by 6 feet. Except when rarely permitted an oil lamp, he had to stand on a bench to read his

On the night of 2 December 1577, a group of Carmelites opposed to reform broke into John's dwelling in Ávila and took him prisoner. John had received an order from superiors, opposed to reform, to leave Ávila and return to his original house. John had refused on the basis that his reform work had been approved by the papal nuncio to Spain, a higher authority than these superiors.

, pages = 10,11 The Carmelites therefore took John captive. John was taken from Ávila to the Carmelite monastery in Toledo, at that time the order's leading monastery in Castile, with a community of 40 friars.

John was brought before a court of friars, accused of disobeying the ordinances of Piacenza. Despite his argument that he had not disobeyed the ordinances, he was sentenced to a term of imprisonment. He was jailed in a monastery where he was kept under a brutal regime that included public lashings before the community at least weekly, and severe isolation in a tiny stifling cell measuring barely 10 feet by 6 feet. Except when rarely permitted an oil lamp, he had to stand on a bench to read his breviary

A breviary (Latin: ''breviarium'') is a liturgical book used in Christianity for praying the canonical hours, usually recited at seven fixed prayer times.

Historically, different breviaries were used in the various parts of Christendom, such ...

by the light through the hole into the adjoining room. He had no change of clothing and a penitential diet of water, bread and scraps of salt fish. During his imprisonment, he composed a great part of his most famous poem ''Spiritual Canticle

''The Spiritual Canticle'' (), is one of the poetic works of the Spanish mystical poet Saint John of the Cross.

Saint John of the Cross, a Carmelite friar and priest during the Counter-Reformation was arrested and jailed by the Calced Carmeli ...

'', as well as a few shorter poems. The paper was passed to him by the friar who guarded his cell. He managed to escape eight months later, on 15 August 1578, through a small window in a room adjoining his cell. (He had managed to pry open the hinges of the cell door earlier that day.)

After being nursed back to health, first by Teresa's nuns in Toledo, and then during six weeks at the Hospital of Santa Cruz, John continued with the reforms. In October 1578 he joined a meeting at Almodóvar del Campo

Almodóvar del Campo is a municipality of Spain, located in the province of Ciudad Real, autonomous community of Castilla–La Mancha. Featuring a total area of 1.208,25 km2, it is the largest municipality in the region and one of the largest ...

of reform supporters, better known as the Discalced Carmelites. There, in part as a result of the opposition faced from other Carmelites, they decided to request from the Pope their formal separation from the rest of the Carmelite order.

At that meeting John was appointed superior of El Calvario, an isolated monastery of around thirty friars in the mountains about 6 miles away from Beas

Beas is a riverfront town in the Amritsar district of the Indian state of Punjab. Beas lies on the banks of the Beas River. Beas town is mostly located in revenue boundary of Budha Theh with parts in villages Dholo Nangal and Wazir Bhullar. ...

in Andalusia. During that time he befriended the nun, Ana de Jesús, superior of the Discalced nuns at Beas, through his visits to the town every Saturday. While at El Calvario he composed the first version of his commentary on his poem, ''The Spiritual Canticle'', possibly at the request of the nuns in Beas.

In 1579 he moved to Baeza

Baeza may refer to:

* Baeza, Ecuador

* Baeza, Spain

** University of Baeza

** Baeza Cathedral

* '' Brusqeulia baeza'', a species of moth

People

* Baeza (rapper) (born 1993), American rapper, singer, actor, hip hop producer, and songwriter

* Ac ...

, a town of around 50,000 people, to serve as rector of a new college, the Colegio de San Basilio, for Discalced friars in Andalusia. It opened on 13 June 1579. He remained in post until 1582, spending much of his time as a spiritual director to the friars and townspeople.

1580 was a significant year in the resolution of disputes between the Carmelites. On 22 June, Pope Gregory XIII

Pope Gregory XIII ( la, Gregorius XIII; it, Gregorio XIII; 7 January 1502 – 10 April 1585), born Ugo Boncompagni, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 13 May 1572 to his death in April 1585. He is best known for ...

signed a decree, entitled ''Pia Consideratione'', which authorised the separation of the old (later "calced") and the newly reformed, "Discalced" Carmelites. The Dominican friar Juan Velázquez de las Cuevas was appointed to oversee the decision. At the first General Chapter of the Discalced Carmelites, in Alcalá de Henares

Alcalá de Henares () is a Spanish city in the Community of Madrid. Straddling the Henares River, it is located to the northeast of the centre of Madrid. , it has a population of 193,751, making it the region's third-most populated municipality ...

on 3 March 1581, John of the Cross was elected one of the "Definitors" of the community, and wrote a constitution for them. By the time of the Provincial Chapter at Alcalá in 1581, there were 22 houses, some 300 friars and 200 nuns among the Discalced Carmelites.

In November 1581, John was sent by Teresa to help Ana de Jesús to found a convent in

In November 1581, John was sent by Teresa to help Ana de Jesús to found a convent in Granada

Granada (,, DIN: ; grc, Ἐλιβύργη, Elibýrgē; la, Illiberis or . ) is the capital city of the province of Granada, in the autonomous community of Andalusia, Spain. Granada is located at the foot of the Sierra Nevada mountains, at the c ...

. Arriving in January 1582, she set up a convent, while John stayed in the monastery of Los Mártires, near the Alhambra, becoming its prior in March 1582. While there, he learned of Teresa's death in October of that year.

In February 1585, John travelled to Málaga

Málaga (, ) is a municipality of Spain, capital of the Province of Málaga, in the autonomous community of Andalusia. With a population of 578,460 in 2020, it is the second-most populous city in Andalusia after Seville and the sixth most po ...

where he established a convent for Discalced nuns. In May 1585, at the General Chapter of the Discalced Carmelites in Lisbon

Lisbon (; pt, Lisboa ) is the capital and largest city of Portugal, with an estimated population of 544,851 within its administrative limits in an area of 100.05 km2. Lisbon's urban area extends beyond the city's administrative limits w ...

, John was elected Vicar Provincial of Andalusia, a post which required him to travel frequently, making annual visitations to the houses of friars and nuns in Andalusia. During this time he founded seven new monasteries in the region, and is estimated to have travelled around 25,000 km.

In June 1588, he was elected third Councillor to the Vicar General for the Discalced Carmelites, Father Nicolas Doria. To fulfill this role, he had to return to Segovia in Castile, where he also took on the role of prior of the monastery. After disagreeing in 1590–1 with some of Doria's remodelling of the leadership of the Discalced Carmelite Order, John was removed from his post in Segovia, and sent by Doria in June 1591 to an isolated monastery in Andalusia called La Peñuela. There he fell ill, and travelled to the monastery at Úbeda

Úbeda (; from Iberian ''Ibiut'') is a town in the province of Jaén in Spain's autonomous community of Andalusia, with 34,733 (data 2017) inhabitants. Both this city and the neighbouring city of Baeza benefited from extensive patronage in the ...

for treatment. His condition worsened, however, and he died there, of erysipelas

Erysipelas () is a relatively common bacterial infection of the superficial layer of the skin ( upper dermis), extending to the superficial lymphatic vessels within the skin, characterized by a raised, well-defined, tender, bright red rash, ...

on 14 December 1591.

Veneration

The morning after John's death huge numbers of townspeople in Úbeda entered the monastery to view his body; in the crush, many were able to take home bits of his habit. He was initially buried at Úbeda, but, at the request of the monastery in Segovia, his body was secretly moved there in 1593. The people of Úbeda, however, unhappy at this change, sent a representative to petition the pope to move the body back to its original resting place. Pope Clement VIII, impressed by the petition, issued a Brief on 15 October 1596 ordering the return of the body to Úbeda. Eventually, in a compromise, the superiors of the Discalced Carmelites decided that the monastery at Úbeda would receive one leg and one arm of the corpse from Segovia (the monastery at Úbeda had already kept one leg in 1593, and the other arm had been removed as the corpse passed through Madrid in 1593, to form a relic there). A hand and a leg remain visible in a reliquary at the Oratory of San Juan de la Cruz in Úbeda, a monastery built in 1627 though connected to the original Discalced monastery in the town founded in 1587. The head and torso were retained by the monastery at Segovia. They were venerated until 1647, when on orders from Rome designed to prevent the veneration of remains without official approval, the remains were buried in the ground. In the 1930s they were disinterred, and are now sited in a side chapel in a marble case above a special altar. Proceedings to beatify John began between 1614 and 1616. He was eventuallybeatified

Beatification (from Latin ''beatus'', "blessed" and ''facere'', "to make”) is a recognition accorded by the Catholic Church of a deceased person's entrance into Heaven and capacity to intercede on behalf of individuals who pray in their n ...

in 1675 by Pope Clement X

Pope Clement X ( la, Clemens X; it, Clemente X; 13 July 1590 – 22 July 1676), born Emilio Bonaventura Altieri, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 29 April 1670 to his death in July 1676. Elected pope at ag ...

, and was canonized

Canonization is the declaration of a deceased person as an officially recognized saint, specifically, the official act of a Christian communion declaring a person worthy of public veneration and entering their name in the canon catalogue of s ...

by Benedict XIII in 1726. When his feast day was added to the General Roman Calendar

The General Roman Calendar is the liturgical calendar that indicates the dates of celebrations of saints and mysteries of the Lord (Jesus Christ) in the Roman Rite of the Catholic Church, wherever this liturgical rite is in use. These cel ...

in 1738, it was assigned to 24 November, since his date of death was impeded by the then-existing octave

In music, an octave ( la, octavus: eighth) or perfect octave (sometimes called the diapason) is the interval between one musical pitch and another with double its frequency. The octave relationship is a natural phenomenon that has been refer ...

of the Feast of the Immaculate Conception

The Solemnity of the Immaculate Conception, also called Immaculate Conception Day, celebrates the sinless lifespan and Immaculate Conception of the Blessed Virgin Mary on 8 December, nine months before the feast of the Nativity of Mary, celebr ...

. This obstacle was removed in 1955 and in 1969 Pope Paul VI

Pope Paul VI ( la, Paulus VI; it, Paolo VI; born Giovanni Battista Enrico Antonio Maria Montini, ; 26 September 18976 August 1978) was head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City, Vatican City State from 21 June 1963 to his ...

moved it to the ''dies natalis'' (birthday to heaven) of John, 14 December

Events Pre-1600

* 557 – Constantinople is severely damaged by an earthquake, which cracks the dome of Hagia Sophia.

* 835 – Sweet Dew Incident: Emperor Wenzong of the Tang dynasty conspires to kill the powerful eunuchs of the T ...

. The Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Brit ...

and the Episcopal Church honor him on the same date. In 1926, he was declared a Doctor of the Church by Pope Pius XI

Pope Pius XI ( it, Pio XI), born Ambrogio Damiano Achille Ratti (; 31 May 1857 – 10 February 1939), was head of the Catholic Church from 6 February 1922 to his death in February 1939. He was the first sovereign of Vatican City f ...

after the definitive consultation of Reginald Garrigou-Lagrange O.P., professor of philosophy and theology at the Pontifical University of Saint Thomas Aquinas

A pontifical ( la, pontificale) is a Christian liturgical book containing the liturgies that only a bishop may perform. Among the liturgies are those of the ordinal for the ordination and consecration of deacons, priests, and bishops to Holy ...

, ''Angelicum'' in Rome.

Literary works

John of the Cross is considered one of the foremost poets in Spanish. Although his complete poems add up to fewer than 2500 verses, two of them, the ''

John of the Cross is considered one of the foremost poets in Spanish. Although his complete poems add up to fewer than 2500 verses, two of them, the ''Spiritual Canticle

''The Spiritual Canticle'' (), is one of the poetic works of the Spanish mystical poet Saint John of the Cross.

Saint John of the Cross, a Carmelite friar and priest during the Counter-Reformation was arrested and jailed by the Calced Carmeli ...

'' and the '' Dark Night of the Soul'', are widely considered masterpieces of Spanish poetry, both for their formal style

Style is a manner of doing or presenting things and may refer to:

* Architectural style, the features that make a building or structure historically identifiable

* Design, the process of creating something

* Fashion, a prevailing mode of clothing ...

and their rich symbol

A symbol is a mark, sign, or word that indicates, signifies, or is understood as representing an idea, object, or relationship. Symbols allow people to go beyond what is known or seen by creating linkages between otherwise very different conc ...

ism and imagery. His theological works often consist of commentaries on the poems. All the works were written between 1578 and his death in 1591.

The ''Spiritual Canticle'' is an eclogue

An eclogue is a poem in a classical style on a pastoral subject. Poems in the genre are sometimes also called bucolics.

Overview

The form of the word ''eclogue'' in contemporary English developed from Middle English , which came from Latin , wh ...

in which the bride, representing the soul

In many religious and philosophical traditions, there is a belief that a soul is "the immaterial aspect or essence of a human being".

Etymology

The Modern English noun '' soul'' is derived from Old English ''sāwol, sāwel''. The earliest att ...

, searches for the bridegroom, representing Jesus Christ

Jesus, likely from he, יֵשׁוּעַ, translit=Yēšūaʿ, label= Hebrew/ Aramaic ( AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ or Jesus of Nazareth (among other names and titles), was a first-century Jewish preacher and relig ...

, and is anxious at having lost him. Both are filled with joy upon reuniting. It can be seen as a free-form Spanish version of the Song of Songs at a time when vernacular translations of the Bible were forbidden. The first 31 stanzas of the poem were composed in 1578 while John was imprisoned in Toledo. After his escape it was read by the nuns at Beas, who made copies of the stanzas. Over the following years, John added further lines. Today, two versions exist: one with 39 stanzas and one with 40 with some of the stanzas ordered differently. The first redaction of the commentary on the poem was written in 1584, at the request of Madre Ana de Jesús, when she was prioress of the Discalced Carmelite nuns in Granada. A second edition, which contains more detail, was written in 1585–6.

The ''Dark Night'', from which the phrase '' Dark Night of the Soul'' takes its name, narrates the journey of the soul from its bodily home to union with God. It happens during the "dark", which represents the hardships and difficulties met in detachment from the world and reaching the light of the union with the Creator. There are several steps during the state of darkness, which are described in successive stanzas. The main idea behind the poem is the painful experience required to attain spiritual maturity and union with God. The poem was likely written in 1578 or 1579. In 1584–5, John wrote a commentary on the first two stanzas and on the first line of the third stanza.

The ''Ascent of Mount Carmel

''Ascent of Mount Carmel'' ( es, Subida del Monte Carmelo) is a 16th-century spiritual treatise by Spanish Catholic mystic and poet Saint John of the Cross. The book is a systematic treatment of the ascetical life in pursuit of mystical union w ...

'' is a more systematic study of the ascetical endeavour of a soul seeking perfect union with God and the mystical

Mysticism is popularly known as becoming one with God or the Absolute, but may refer to any kind of ecstasy or altered state of consciousness which is given a religious or spiritual meaning. It may also refer to the attainment of insight in u ...

events encountered along the way. Although it begins as a commentary on ''The Dark Night'', after the first two stanzas of the poem, it rapidly diverts into a full treatise. It was composed some time between 1581 and 1585.Kavanaugh, ''The Collected Works of St John of the Cross'', 34.

A four-stanza work, ''Living Flame of Love'', describes a greater intimacy, as the soul responds to God's love. It was written in a first version at Granada between 1585 and 1586, apparently in two weeks, and in a mostly identical second version at La Peñuela in 1591.Kavanaugh, ''The Collected Works of St John of the Cross'', 634.

These, together with his ''Dichos de Luz y Amor'' or "Sayings of Light and Love" along with Teresa's own writings, are the most important mystical works in Spanish, and have deeply influenced later spiritual writers across the world. They include: T. S. Eliot, Thérèse de Lisieux, Edith Stein

Edith Stein (religious name Saint Teresia Benedicta a Cruce ; also known as Saint Teresa Benedicta of the Cross or Saint Edith Stein; 12 October 1891 – 9 August 1942) was a German Jewish philosopher who converted to Christianity and became a D ...

(Teresa Benedicta of the Cross) and Thomas Merton

Thomas Merton (January 31, 1915 – December 10, 1968) was an American Trappist monk, writer, theologian, mystic, poet, social activist and scholar of comparative religion. On May 26, 1949, he was ordained to the Catholic priesthood and g ...

. John is said to have also influenced philosophers (Jacques Maritain

Jacques Maritain (; 18 November 1882 – 28 April 1973) was a French Catholic philosopher. Raised Protestant, he was agnostic before converting to Catholicism in 1906. An author of more than 60 books, he helped to revive Thomas Aquinas fo ...

), theologians (Hans Urs von Balthasar

Hans Urs von Balthasar (12 August 1905 – 26 June 1988) was a Swiss theologian and Catholic priest who is considered an important Catholic theologian of the 20th century. He was announced as his choice to become a cardinal by Pope John Paul II, b ...

), pacifists

Pacifism is the opposition or resistance to war, militarism (including conscription and mandatory military service) or violence. Pacifists generally reject theories of Just War. The word ''pacifism'' was coined by the French peace campaigne ...

(Dorothy Day

Dorothy Day (November 8, 1897 – November 29, 1980) was an American journalist, social activist and anarchist who, after a bohemian youth, became a Catholic without abandoning her social and anarchist activism. She was perhaps the best-known ...

, Daniel Berrigan

Daniel Joseph Berrigan (May 9, 1921 – April 30, 2016) was an American Jesuit priest, anti-war activist, Christian pacifist, playwright, poet, and author.

Berrigan's active protest against the Vietnam War earned him both scorn and admi ...

and Philip Berrigan) and artists (Salvador Dalí

Salvador Domingo Felipe Jacinto Dalí i Domènech, Marquess of Dalí of Púbol (; ; ; 11 May 190423 January 1989) was a Spanish Surrealism, surrealist artist renowned for his technical skill, precise draftsmanship, and the striking and bizarr ...

). Pope John Paul II

Pope John Paul II ( la, Ioannes Paulus II; it, Giovanni Paolo II; pl, Jan Paweł II; born Karol Józef Wojtyła ; 18 May 19202 April 2005) was the head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 1978 until his ...

wrote his theological dissertation on the mystical theology of John of the Cross.

Editions of his works

His writings were first published in 1618 by Diego de Salablanca. The numerical divisions in the work, still used by modern editions of the text, were introduced by Salablanca (they were not in John's original writings) to help make the work more manageable for the reader. This edition does not contain the ''Spiritual Canticle'' however, and also omits or adapts certain passages, perhaps for fear of falling foul of the Inquisition. The ''Spiritual Canticle'' was first included in the 1630 edition, produced by Fray Jeronimo de San José, at Madrid. This edition was largely followed by later editors, although editions in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries gradually included a few more poems and letters. The first French edition was published in Paris in 1622, and the first Castilian edition in 1627 in Brussels. A critical edition of St John of the Cross's work in English was published by E. Allison Peers in 1935.Intellectual influences

The influences on John's writing are subject to an ongoing debate. It is widely acknowledged that at Salamanca university there would have existed a range of intellectual positions. In John's time they included the influences ofThomas Aquinas

Thomas Aquinas, Dominican Order, OP (; it, Tommaso d'Aquino, lit=Thomas of Aquino, Italy, Aquino; 1225 – 7 March 1274) was an Italian Dominican Order, Dominican friar and Catholic priest, priest who was an influential List of Catholic philo ...

, of Scotus

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. federal court cases, and over state court cases that involve a point of ...

and of Durandus. It is often assumed that John would have absorbed the thought of Aquinas, to explain the scholastic framework of his writings.

However, the belief that John was taught at both the Carmelite College of San Andrès and at the University of Salamanca has been challenged. Bezares calls into question whether John even studied theology at the University of Salamanca. The philosophy courses John probably took in logic, natural and moral philosophy, can be reconstructed, but Bezares argues that John in fact abandoned his studies at Salamanca in 1568 to join Teresa, rather than graduating. In the first biography of John, published in 1628, it is claimed, on the basis of information from John's fellow students, that he in 1567 made a special study of mystical writers, in particular of Pseudo-Dionysius and Pope Gregory I

Pope Gregory I ( la, Gregorius I; – 12 March 604), commonly known as Saint Gregory the Great, was the bishop of Rome from 3 September 590 to his death. He is known for instigating the first recorded large-scale mission from Rome, the Gregoria ...

.

There is little consensus from John's early years or potential influences.

Scripture

John was influenced heavily by the Bible. Scriptural images are common in both his poems and prose. In total, there are 1,583 explicit and 115 implicit quotations from the Bible in his works., p. 116 The influence of the ''Song of Songs'' on John's ''Spiritual Canticle'' has often been noted, both in terms of the structure of the poem, with its dialogue between two lovers, the account of their difficulties in meeting each other and the "offstage chorus" that comments on the action, and also in terms of the imagery for example, of pomegranates, wine cellar, turtle dove and lilies, which echoes that of the ''Song of Songs''. In addition, John shows at occasional points the influence of the Divine Office. This demonstrates how John, steeped in the language and rituals of the Church, drew at times on the phrases and language here.Pseudo-Dionysius

It has rarely been disputed that the overall structure of John's mystical theology, and his language of the union of the soul with God, is influenced by the pseudo-Dionysian tradition. However, it has not been clear whether John might have had direct access to the writings ofPseudo-Dionysius

Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite (or Dionysius the Pseudo-Areopagite) was a Greek author, Christian theologian and Neoplatonic philosopher of the late 5th to early 6th century, who wrote a set of works known as the ''Corpus Areopagiticum' ...

, or whether this influence may have been mediated through various later authors.

Medieval mystics

It is widely acknowledged that John may have been influenced by the writings of other medieval mystics, though there is debate about the exact thought which may have influenced him, and about how he might have been exposed to their ideas. The possibility of influence by the so-called "Rhineland mystics

The Friends of God (German: Gottesfreunde; or gotesvriunde) was a medieval mystical group of both ecclesiastical and lay persons within the Catholic Church (though it nearly became a separate sect) and a center of German mysticism. It was foun ...

" such as Meister Eckhart

Eckhart von Hochheim ( – ), commonly known as Meister Eckhart, Master Eckhart

John of the Cross

on

The Metaphysics of Mysticism: The Mystical Philosophy of Saint John of the Cross

Biography of Saint John of the Cross

Works by Saint John of the Cross

at Christian Classics Ethereal Library * *

Thomas Merton on Saint John of the Cross

Lectio divina and Saint John of the Cross

* ttp://poemsintranslation.blogspot.com/2009/09/saint-john-of-cross-dark-night-of-soul.html Verse-translation of ''The Dark Night of the Soul''at ''Poems Found in Translation'' {{Authority control 1542 births 1591 deaths Burials in the Community of Castile and León 16th-century Christian saints 16th-century Spanish Roman Catholic priests 16th-century Christian mystics Baroque writers Carmelite mystics Carmelite saints Carmelite spirituality Catholic spirituality Counter-Reformation Deaths from streptococcus infection Discalced Carmelites Doctors of the Church Founders of Catholic religious communities Incorrupt saints People from the Province of Ávila Poet priests Roman Catholic mystics Spanish Catholic poets Spanish escapees Spanish hermits Spanish people of Jewish descent Spanish Roman Catholic saints 16th-century Spanish Roman Catholic theologians Spanish spiritual writers University of Salamanca alumni Venerated Carmelites Spanish Christian mystics Anglican saints Venerated Catholics Canonizations by Pope Benedict XIII Beatifications by Pope Clement X

Islamic influence

A controversial theory on the origins of John's mystical imagery is that he may have been influenced by Islamic sources. This was first proposed in detail by Miguel Asín Palacios and has been most recently put forward by the Puerto Rican scholar Luce López-Baralt. Arguing that John was influenced by Islamic sources on the peninsula, she traces Islamic antecedents of the images of the "dark night", the "solitary bird" of the ''Spiritual Canticle'', wine and mystical intoxication (the ''Spiritual Canticle''), lamps of fire (the ''Living Flame''). However, Peter Tyler concludes, there "are sufficient Christian medieval antecedents for many of the metaphors John employs to suggest we should look for Christian sources rather than Muslim sources". As José Nieto indicates, in trying to locate a link between Spanish Christian mysticism and Islamic mysticism, it might make more sense to refer to the common Neo-Platonic tradition and mystical experiences of both, rather than seek direct influence.José Nieto, ''Mystic, Rebel, Saint: A Study of St. John of the Cross'' (Geneva, 1979)Books

* John of the Cross, ''Dark Night of the Soul'', London, 2012. limovia.net * John of the Cross, ''Ascent of Mount Carmel'', London, 2012. limovia.net * John of the Cross, ''Spiritual Canticle of the Soul and the Bridegroom Christ'', London, 2012. limovia.net *''The Dark Night: A Masterpiece in the Literature of Mysticism'' (Translated and Edited by E. Allison Peers), Doubleday, 1959. *''The Poems of Saint John of the Cross'' (English Versions and Introduction by Willis Barnstone),Indiana University Press

Indiana University Press, also known as IU Press, is an academic publisher founded in 1950 at Indiana University that specializes in the humanities and social sciences. Its headquarters are located in Bloomington, Indiana. IU Press publishes 140 ...

, 1968, revised 2nd ed. New Directions, 1972.

*''The Dark Night, St. John of the Cross'' (Translated by Mirabai Starr), Riverhead Books

Riverhead Books is an imprint of Penguin Group (USA) founded in 1994 by Susan Petersen Kennedy.

Writers published by Riverhead include Ali Sethi, Marlon James, Junot Díaz, George Saunders, Khaled Hosseini, Nick Hornby, Anne Lamott, Carlo ...

, New York, 2002,

*''Poems of St John of The Cross'' (Translated and Introduction by Kathleen Jones), Burns and Oates, Tunbridge Wells, Kent, UK, 1993,

*''The Collected Works of St John of the Cross'' (Eds. K. Kavanaugh and O. Rodriguez), Institute of Carmelite Studies, Washington DC, revised edition, 1991,

* "St. John of the Cross: His Prophetic Mysticism in Sixteenth-Century Spain" by Prof Cristobal Serran-Pagan

See also

*A lo divino ''A lo divino'' () is a Spanish phrase meaning "to the divine" or "in a sacred manner". The phrase is frequently used to describe a secular work, rewritten with a religious overtone, or a secular topic recast in religious terms using metaphors an ...

* Book of the First Monks

*Byzantine Discalced Carmelites

The Byzantine Discalced Carmelites are communities of Discalced Carmelites that operate in several Eastern Catholic Churches, namely the Bulgarian Byzantine Catholic Church, the Melkite Greek Catholic Church, the Ruthenian Greek Catholic Church, ...

*Calendar of saints (Church of England)

The Church of England commemorates many of the same saints as those in the General Roman Calendar, mostly on the same days, but also commemorates various notable (often post-Reformation) Christians who have not been canonised by Rome, with a part ...

*Carmelite Rule of St. Albert

The eremitic Rule of Saint Albert is the shortest of the rules of consecrated life in existence of the Catholic spiritual tradition, and is composed almost exclusively of scriptural precepts. To this day it is a rich source of inspiration for the ...

*Christian meditation

Christian meditation is a form of prayer in which a structured attempt is made to become aware of and reflect upon the revelations of God. The word meditation comes from the Latin word ''meditārī'', which has a range of meanings including to r ...

* Constitutions of the Carmelite Order

*List of Catholic saints

This is an incomplete list of people and angels whom the Catholic Church has canonized as saints. According to Catholic theology, all saints enjoy the beatific vision. Many of the saints listed here are to be found in the General Roman Cal ...

*Miguel Asín Palacios

Miguel Asín Palacios (5 July 1871 – 12 August 1944) was a Spanish scholar of Islamic studies and the Arabic language, and a Roman Catholic priest. He is primarily known for suggesting Muslim sources for ideas and motifs present in Dante's Divin ...

* Saint John of the Cross, patron saint archive

*Saint Raphael Kalinowski, the first friar to be canonized (in 1991 by Pope John Paul II

Pope John Paul II ( la, Ioannes Paulus II; it, Giovanni Paolo II; pl, Jan Paweł II; born Karol Józef Wojtyła ; 18 May 19202 April 2005) was the head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 1978 until his ...

) in the Order of Discalced Carmelites since Saint John of the Cross

*Spanish Renaissance literature

Spanish Renaissance literature is the literature written in Spain during the Spanish Renaissance during the 15th and 16th centuries. .

Overview

Political, religious, literary, and military relations between Italy and Spain from the second half o ...

* Secular Order of Discalced Carmelites

* The world, the flesh, and the devil

References

Sources

* * *Further reading

* Howells, E. "Spanish Mysticism and Religious Renewal: Ignatius of Loyola, Teresa of Ávila, and John of the Cross (16th Century, Spain)", in Julia A. Lamm, ed., ''Blackwell Companion to Christian Mysticism'', (Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 2012) * Kavanaugh, K. ''John of the Cross: doctor of light and love'' (2000) * Matthew, Iain. ''The Impact of God, Soundings from St John of the Cross'' (Hodder & Stoughton, 1995) * Payne, Stephen. ''John of the Cross and the Cognitive Value of Mysticism'' (1990) * Stein, Edith, ''The Science of the Cross'' (translated by Sister Josephine Koeppel, O.C.D. ''The Collected Works of Edith Stein'', Vol. 6, ICS Publications, 2011) * Williams, Rowan. ''The wound of knowledge: Christian spirituality from the New Testament to St. John of the Cross'' (1990) * Wojtyła, K. ''Faith According to St. John of the Cross'' (1981) * "St. John of the Cross: His Prophetic Mysticism in Sixteenth-Century Spain" by Prof Cristobal Serran-PaganExternal links

John of the Cross

on

Catholic Encyclopedia

The ''Catholic Encyclopedia: An International Work of Reference on the Constitution, Doctrine, Discipline, and History of the Catholic Church'' (also referred to as the ''Old Catholic Encyclopedia'' and the ''Original Catholic Encyclopedia'') i ...

The Metaphysics of Mysticism: The Mystical Philosophy of Saint John of the Cross

Biography of Saint John of the Cross

Works by Saint John of the Cross

at Christian Classics Ethereal Library * *

Thomas Merton on Saint John of the Cross

Lectio divina and Saint John of the Cross

* ttp://poemsintranslation.blogspot.com/2009/09/saint-john-of-cross-dark-night-of-soul.html Verse-translation of ''The Dark Night of the Soul''at ''Poems Found in Translation'' {{Authority control 1542 births 1591 deaths Burials in the Community of Castile and León 16th-century Christian saints 16th-century Spanish Roman Catholic priests 16th-century Christian mystics Baroque writers Carmelite mystics Carmelite saints Carmelite spirituality Catholic spirituality Counter-Reformation Deaths from streptococcus infection Discalced Carmelites Doctors of the Church Founders of Catholic religious communities Incorrupt saints People from the Province of Ávila Poet priests Roman Catholic mystics Spanish Catholic poets Spanish escapees Spanish hermits Spanish people of Jewish descent Spanish Roman Catholic saints 16th-century Spanish Roman Catholic theologians Spanish spiritual writers University of Salamanca alumni Venerated Carmelites Spanish Christian mystics Anglican saints Venerated Catholics Canonizations by Pope Benedict XIII Beatifications by Pope Clement X