John T. Scopes on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

John Thomas Scopes (August 3, 1900 – October 21, 1970) was a teacher in

The results of the Scopes Trial affected him professionally and personally. His public image was mocked in animation, cartoons and other media in the following years. Scopes himself retreated from the public eye and focused his attention on his career.

In September 1925, he enrolled in the graduate school of

The results of the Scopes Trial affected him professionally and personally. His public image was mocked in animation, cartoons and other media in the following years. Scopes himself retreated from the public eye and focused his attention on his career.

In September 1925, he enrolled in the graduate school of

Ghostarchive

and th

Wayback Machine

In June 1967, Scopes wrote ''Center of the Storm: Memoirs of John T. Scopes''. The Butler Act was repealed that same year.

Dayton, Tennessee

Dayton is a city and county seat in Rhea County, Tennessee, United States. As of the 2020 census, the city population was 7,065. The Dayton Urban Cluster, which includes developed areas adjacent to the city and extends south to Graysville.

Da ...

, who was charged on May 5, 1925, with violating Tennessee

Tennessee ( , ), officially the State of Tennessee, is a landlocked state in the Southeastern region of the United States. Tennessee is the 36th-largest by area and the 15th-most populous of the 50 states. It is bordered by Kentucky to th ...

's Butler Act

The Butler Act was a 1925 Tennessee law prohibiting public school teachers from denying the Biblical account of mankind's origin. The law also prevented the teaching of the evolution of man from what it referred to as lower orders of animals in ...

, which prohibited the teaching of human evolution

Human evolution is the evolutionary process within the history of primates that led to the emergence of ''Homo sapiens'' as a distinct species of the hominid family, which includes the great apes. This process involved the gradual development of ...

in Tennessee schools. He was tried in a case known as the Scopes Monkey Trial, in which he was found guilty and fined $100 ().

Early life

Scopes was born in 1900 to Thomas Scopes and Mary Alva Brown, who lived on a farm inPaducah, Kentucky

Paducah ( ) is a home rule-class city in and the county seat of McCracken County, Kentucky. The largest city in the Jackson Purchase region, it is located at the confluence of the Tennessee and the Ohio rivers, halfway between St. Louis, Missour ...

. John was the fifth child and only son. The family moved to Danville, Illinois

Danville is a city in and the county seat of Vermilion County, Illinois. As of the 2010 census, its population was 33,027. As of 2019, the population was an estimated 30,479.

History

The area that is now Danville was once home to the Miami, K ...

, when he was a teenager. In 1917, he moved to Salem, Illinois

Salem is a city in and the county seat of Marion County, Illinois, United States. The population was 7,485 at the 2010 census.

Geography

Salem is located at (38.6282, -88.9482).

According to the 2010 census, Salem has a total area of , of w ...

, where he was a member of the class of 1919 at Salem High School.

He attended the University of Illinois

The University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign (U of I, Illinois, University of Illinois, or UIUC) is a public land-grant research university in Illinois in the twin cities of Champaign and Urbana. It is the flagship institution of the University ...

briefly before leaving for health reasons. He earned a degree at the University of Kentucky

The University of Kentucky (UK, UKY, or U of K) is a Public University, public Land-grant University, land-grant research university in Lexington, Kentucky. Founded in 1865 by John Bryan Bowman as the Agricultural and Mechanical College of Kentu ...

in 1924, with a major in law and a minor in geology.

Scopes moved to Dayton where he became the Rhea County High School

A secondary school describes an institution that provides secondary education and also usually includes the building where this takes place. Some secondary schools provide both '' lower secondary education'' (ages 11 to 14) and ''upper seconda ...

's football

Football is a family of team sports that involve, to varying degrees, kicking a ball to score a goal. Unqualified, the word ''football'' normally means the form of football that is the most popular where the word is used. Sports commonly c ...

coach

Coach may refer to:

Guidance/instruction

* Coach (sport), a director of athletes' training and activities

* Coaching, the practice of guiding an individual through a process

** Acting coach, a teacher who trains performers

Transportation

* Co ...

, and occasionally served as a substitute teacher.

Trial

Scopes' involvement in the so-called Scopes Monkey Trial came about after theAmerican Civil Liberties Union

The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) is a nonprofit organization founded in 1920 "to defend and preserve the individual rights and liberties guaranteed to every person in this country by the Constitution and laws of the United States". T ...

(ACLU) announced that it would finance a test case

In software engineering, a test case is a specification of the inputs, execution conditions, testing procedure, and expected results that define a single test to be executed to achieve a particular software testing objective, such as to exercise ...

challenging the constitutionality

Constitutionality is said to be the condition of acting in accordance with an applicable constitution; "Webster On Line" the status of a law, a procedure, or an act's accordance with the laws or set forth in the applicable constitution. When l ...

of the Butler Act if they could find a Tennessee teacher who was willing to act as a defendant.

A band of businessmen in Dayton, Tennessee, led by engineer and geologist George Rappleyea

George Washington Rappleyea (July 4, 1894 – August 29, 1966), an American metallurgical engineer and the manager of the Cumberland Coal and Iron Company in Dayton, Tennessee. He held this position in the summer of 1925 when he became the chief ...

, saw this as an opportunity to get publicity for their town, and they approached Scopes. Rappleyea pointed out that while the Butler Act prohibited the teaching of human evolution, the state required teachers to use the assigned textbook, Hunter

Hunting is the human activity, human practice of seeking, pursuing, capturing, or killing wildlife or feral animals. The most common reasons for humans to hunt are to harvest food (i.e. meat) and useful animal products (fur/hide (skin), hide, ...

's ''Civic Biology

''A Civic Biology: Presented in Problems'' (usually referred to as just ''Civic Biology'') was a biology textbook written by George William Hunter, published in 1914. It is the book which the state of Tennessee required high school teachers to u ...

'' (1914), which included a chapter on evolution. Rappleyea argued that teachers were essentially required to break the law. When asked about the test case, Scopes was initially reluctant to get involved. After some discussion he told the group gathered in Robinson's Drugstore, "If you can prove that I've taught evolution and that I can qualify as a defendant, then I'll be willing to stand trial."

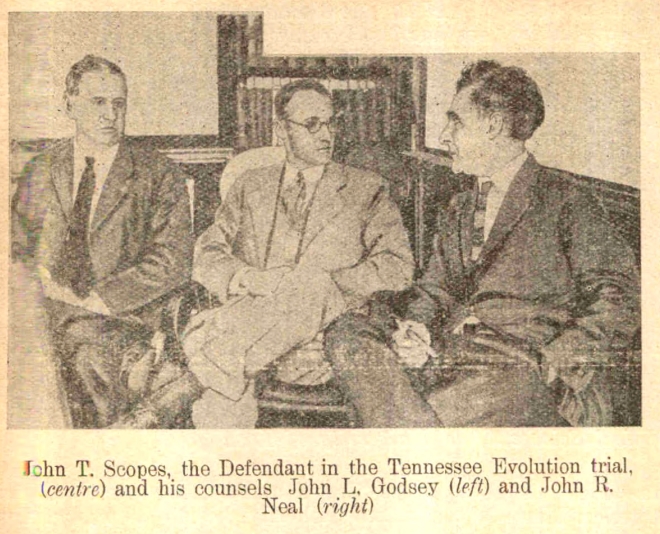

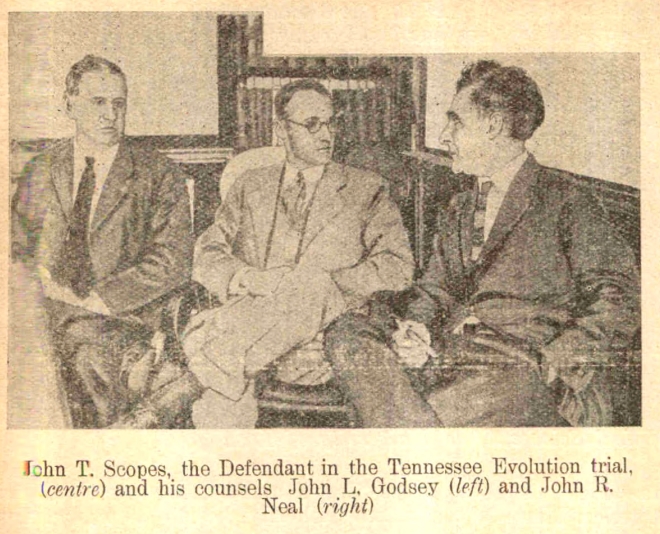

By the time the trial had begun, the defense

Defense or defence may refer to:

Tactical, martial, and political acts or groups

* Defense (military), forces primarily intended for warfare

* Civil defense, the organizing of civilians to deal with emergencies or enemy attacks

* Defense industr ...

team included Clarence Darrow

Clarence Seward Darrow (; April 18, 1857 – March 13, 1938) was an American lawyer who became famous in the early 20th century for his involvement in the Leopold and Loeb murder trial and the Scopes "Monkey" Trial. He was a leading member of t ...

, Dudley Field Malone

Dudley Field Malone (June 3, 1885 – October 5, 1955) was an American attorney, politician, liberal activist, and actor. Malone is best remembered as one of the most prominent liberal attorneys in the United States during the decade of the 1920s ...

, John Neal, Arthur Garfield Hays

Arthur Garfield Hays (December 12, 1881 – December 14, 1954) was an American lawyer and champion of civil liberties issues, best known as a co-founder and general counsel of the American Civil Liberties Union and for participating in notable ca ...

and Frank McElwee. The prosecution team, led by Tom Stewart Thomas Stewart may refer to:

Politicians and nobility

* Thomas A. Stewart (politician) (1849–1920), member of the Wisconsin State Assembly

* Thomas E. Stewart (1824–1904), U.S. Representative from New York

*Thomas Joseph Stewart (1848–1926), ...

, included brothers Herbert Hicks and Sue K. Hicks, Wallace Haggard, father and son pairings Ben and J. Gordon McKenzie, and William Jennings Bryan

William Jennings Bryan (March 19, 1860 – July 26, 1925) was an American lawyer, orator and politician. Beginning in 1896, he emerged as a dominant force in the History of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, running ...

and William Jennings Bryan Jr. The elder Bryan had spoken at Scopes' high school commencement, and remembered the defendant was laughing while he was giving the address to the graduating class six years earlier.

The case ended on July 21, 1925, with a guilty

Guilty or The Guilty may refer to:

* Guilt (emotion), an experience that occurs when a person believes they have violated a moral standard

Law

*Culpability, the degree to which an agent can be held responsible for action or inaction

*Guilt (law) ...

verdict

In law, a verdict is the formal trier of fact, finding of fact made by a jury on matters or questions submitted to the jury by a judge. In a bench trial, the judge's decision near the end of the trial is simply referred to as a finding. In Engl ...

, and Scopes was fined $100 (Roughly $1,460 in 2020). The case was appealed to the Tennessee Supreme Court

The Tennessee Supreme Court is the ultimate judicial tribunal of the state of Tennessee. Roger A. Page is the Chief Justice.

Unlike other states, in which the state attorney general is directly elected or appointed by the governor or state le ...

. In a 3–1 decision written by Chief Justice Grafton Green

Grafton Green (August 12, 1872 – January 27, 1947) was an American jurist who served on the Tennessee Supreme Court from 1910 to 1947, including more than 23 years as chief justice.constitutional

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organisation or other type of entity and commonly determine how that entity is to be governed.

When these princip ...

, but the court overturned Scopes's conviction because the judge had set the fine instead of the jury. The Butler Act remained in effect until May 18, 1967, when it was repealed by the Tennessee legislature

The Tennessee General Assembly (TNGA) is the state legislature of the U.S. state of Tennessee. It is a part-time bicameral legislature consisting of a Senate and a House of Representatives. The Speaker of the Senate carries the additional title ...

.

Scopes may have actually been innocent of the crime to which his name is inexorably linked. After the trial, he admitted to reporter William Kinsey Hutchinson

William Kinsey Hutchinson (June 27, 1896 – May 25, 1958) was an American reporter who became friends with presidents, legislators, cabinet members, and other U.S. government diplomats and officials. Between 1913 and 1920 William (Bill) wo ...

, "I didn't violate the law," explaining that he had skipped the evolution lesson, and that his lawyers had coached his students to go on the stand; the Dayton businessmen had assumed that he had violated the law. Hutchinson did not file his story until after the Scopes appeal was decided in 1927.

In 1955, the trial was made into a play titled '' Inherit the Wind'' starring Paul Muni

Paul Muni (born Frederich Meshilem Meier Weisenfreund; September 22, 1895– August 25, 1967) was an American stage and film actor who grew up in Chicago. Muni was a five-time Academy Award nominee, with one win. He started his acting career in ...

as a character based on Clarence Darrow, and Ed Begley

Edward James Begley Sr. (March 25, 1901 – April 28, 1970) was an American actor of theatre, radio, film, and television. He won an Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor for his performance in the film ''Sweet Bird of Youth'' (1962) an ...

as a character based on William Jennings Bryan. In 1960, a film version of the play starred Spencer Tracy

Spencer Bonaventure Tracy (April 5, 1900 – June 10, 1967) was an American actor. He was known for his natural performing style and versatility. One of the major stars of Hollywood's Golden Age, Tracy was the first actor to win two cons ...

as the Darrow character and Fredric March

Fredric March (born Ernest Frederick McIntyre Bickel; August 31, 1897 – April 14, 1975) was an American actor, regarded as one of Hollywood's most celebrated, versatile stars of the 1930s and 1940s.Obituary ''Variety'', April 16, 1975, p ...

as the Bryan character.

Both the play and the film engage in literary license

Artistic license (alongside more contextually-specific derivative terms such as poetic license, historical license, dramatic license, and narrative license) refers to deviation from fact or form for artistic purposes. It can include the alterat ...

with the facts. For example, "Bertram Cates" (the character representing Scopes) is shown being arrested in class, thrown in jail, burned in effigy by frenzied, mean-spirited, and ignorant townspeople, and taunted by a fire-snorting preacher. "Matthew Harrison Brady" (Bryan), an almost comical fanatic, dramatically dies of a "busted belly" while attempting to deliver his summation in a chaotic courtroom. None of that actually happened in Dayton, Tennessee

Dayton is a city and county seat in Rhea County, Tennessee, United States. As of the 2020 census, the city population was 7,065. The Dayton Urban Cluster, which includes developed areas adjacent to the city and extends south to Graysville.

Da ...

, during the trial.

Life after the trial

The results of the Scopes Trial affected him professionally and personally. His public image was mocked in animation, cartoons and other media in the following years. Scopes himself retreated from the public eye and focused his attention on his career.

In September 1925, he enrolled in the graduate school of

The results of the Scopes Trial affected him professionally and personally. His public image was mocked in animation, cartoons and other media in the following years. Scopes himself retreated from the public eye and focused his attention on his career.

In September 1925, he enrolled in the graduate school of University of Chicago

The University of Chicago (UChicago, Chicago, U of C, or UChi) is a private research university in Chicago, Illinois. Its main campus is located in Chicago's Hyde Park neighborhood. The University of Chicago is consistently ranked among the b ...

to finish his studies in geology. Evidence of harassment by the press was highlighted by Frank Thorne: “You may be interested to know that Mr. John T. Scopes of anti-evolution trial fame expects to take up the study of geology as a graduate student of Chicago this fall…Please do what you can to protect him from the importunities of Chicago reporters….He is a modest and unassuming young chap, and has been subjected to a great deal more limelight than he likes.” A year later, the Tennessee Supreme Court decision of 1926 prompted the press to pursue Scopes again. During this time, he wrote to Thorne, “I am tired of fooling with them.” It is evident that the media attention was affecting Scopes emotionally.

Even worse, the Depression affected his career. After graduation, he was "barred" from career opportunities in Tennessee, requiring him and his wife to move into his childhood home in Kentucky around 1930.

Having failed in education, Scopes attempted a political career and entered an unsuccessful bid as a candidate of the Socialist Party for a seat in the U.S. House of Representatives in Kentucky's only at-large congressional race in 1932. In the end, Scopes returned to the oil industry, serving as an oil expert for the United Production Corporation, later known as United Gas Corporation

United Gas Corporation was a major oil company from its inception in 1930 to its hostile takeover and subsequent forced merger with Pennzoil in 1968.United Gas Corp. v. Pennzoil Co., 248 F.Supp. 449 (S.D.N.Y. 1965) http://www.leagle.com/decision ...

. There, he first worked out of Beeville, Texas, then in the company’s Houston office until 1940, and later in Shreveport, Louisiana, where he stayed until his death. United Gas merged into what was Pennzoil

Pennzoil is an American motor oil brand currently owned by Shell plc. The former Pennzoil Company had been established in 1913 in Pennsylvania, being active in business as an independent firm until it was acquired by Shell in 2002, becoming a bra ...

in 1968.

Later in his life, the media surrounding Scopes calmed down. Occasionally, he was dragged into the spotlight, such as to attend the 1960 ''Inherit the Wind'' premiere, accept the key to the city, and participate in the celebration of John T. Scopes Day.

Scopes and the story of his trial were featured in the first segment of the October 10, 1960, episode of the television game show ''To Tell the Truth''.Archived aGhostarchive

and th

Wayback Machine

In June 1967, Scopes wrote ''Center of the Storm: Memoirs of John T. Scopes''. The Butler Act was repealed that same year.

Personal life and death

Scopes married Mildred Elizabeth Scopes (née

A birth name is the name of a person given upon birth. The term may be applied to the surname, the given name, or the entire name. Where births are required to be officially registered, the entire name entered onto a birth certificate or birth re ...

Walker) (1905–1990). Together they had two sons: John Thomas Jr. and William Clement "Bill".

He died on October 21, 1970, of cancer

Cancer is a group of diseases involving abnormal cell growth with the potential to invade or spread to other parts of the body. These contrast with benign tumors, which do not spread. Possible signs and symptoms include a lump, abnormal b ...

in Shreveport, Louisiana

Shreveport ( ) is a city in the U.S. state of Louisiana. It is the third most populous city in Louisiana after New Orleans and Baton Rouge, respectively. The Shreveport–Bossier City metropolitan area, with a population of 393,406 in 2020, is t ...

, at the age of 70.

See also

*Mildred Seydell

Mildred Seydell (born Mildred Rutherford Woolley; March 21, 1889 – February 20, 1988) was an American pioneering female journalist in Georgia. Seydel wrote as a syndicated columnist and founded the ''Seydell Journal'', a quarterly journa ...

References

Sources

* * * * * * *Further reading

Books * Web *External links

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Scopes, John Thomas 1900 births 1970 deaths 20th-century American geologists Schoolteachers from Tennessee Socialist Party of America politicians from Kentucky Burials in Kentucky Converts to Roman Catholicism People from Marion County, Illinois People from Paducah, Kentucky People from Rhea County, Tennessee People from Danville, Illinois Scopes Trial University of Chicago alumni University of Kentucky alumni People from Salem, Illinois Writers from Kentucky Deaths from cancer in Louisiana 20th-century American educators