John Strachan on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

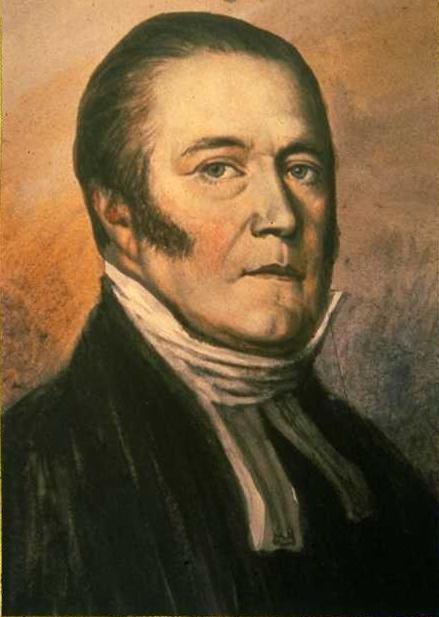

John Strachan (; 12 April 1778 – 1 November 1867) was a notable figure in

He moved to

He moved to

Much of Strachan's life and work was focused on education. He wanted Upper Canada to be under Church of England control to avoid American influence. He tried to set up annual reviews for

Much of Strachan's life and work was focused on education. He wanted Upper Canada to be under Church of England control to avoid American influence. He tried to set up annual reviews for

Documents by Strachan

from

Poetry by Strachan

{{DEFAULTSORT:Strachan, John 1778 births 1867 deaths Anglican bishops of Toronto 19th-century Anglican Church of Canada bishops Converts to Anglicanism from Presbyterianism People from Aberdeen People from Old Toronto Pre-Confederation Ontario people Presidents of the University of Toronto Scottish emigrants to pre-Confederation Ontario Alumni of the University of Aberdeen Persons of National Historic Significance (Canada) Members of the American Antiquarian Society Immigrants to Upper Canada Canadian people of the War of 1812

Upper Canada

The Province of Upper Canada (french: link=no, province du Haut-Canada) was a part of British Canada established in 1791 by the Kingdom of Great Britain, to govern the central third of the lands in British North America, formerly part of the ...

and the first Anglican

Anglicanism is a Western Christian tradition that has developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the context of the Protestant Reformation in Europe. It is one of th ...

Bishop of Toronto. He is best known as a political bishop who held many government positions and promoted education from common schools to helping to found the University of Toronto

The University of Toronto (UToronto or U of T) is a public research university in Toronto, Ontario, Canada, located on the grounds that surround Queen's Park. It was founded by royal charter in 1827 as King's College, the first institution ...

.

Gauvreau says in the 1820s he was "the most eloquent and powerful Upper Canadian exponent of an anti-republican social order based upon the tory principles of hierarchy and subordination in both church and state". Craig characterizes him as "the Canadian arch tory of his era" for his intense conservatism. Craig argues that Strachan "believed in an ordered society, an established church, the prerogative of the crown, and prescriptive rights; he did not believe that the voice of the people was the voice of God".

Strachan built his home in a large yard bound by Simcoe Street, York Street, and Front Street. It was a two-storey building that was the first building in Toronto to use locally manufactured bricks. The gardens and grounds of the property occupied the entire square and became a local Toronto landmark, being given the name "The Bishop's Palace". After Strachan's death, the home was converted into a private hotel called The Palace Boarding House.

Life and work

Early life

Born 12 April 1778, Strachan was the youngest of six children born to the overseer of agranite

Granite () is a coarse-grained (phaneritic) intrusive igneous rock composed mostly of quartz, alkali feldspar, and plagioclase. It forms from magma with a high content of silica and alkali metal oxides that slowly cools and solidifies undergro ...

quarry in Aberdeen

Aberdeen (; sco, Aiberdeen ; gd, Obar Dheathain ; la, Aberdonia) is a city in North East Scotland, and is the third most populous city in the country. Aberdeen is one of Scotland's 32 local government council areas (as Aberdeen City), and ...

, Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a border with England to the southeast and is otherwise surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean to the ...

. He graduated from King's College, Aberdeen

King's College in Old Aberdeen, Scotland, the full title of which is The University and King's College of Aberdeen (''Collegium Regium Abredonense''), is a formerly independent university founded in 1495 and now an integral part of the Universi ...

, in 1797. After his father died in an accident in 1794, Strachan tutored students and taught school to finance his own education.

He emigrated to Kingston, Upper Canada

The Province of Upper Canada (french: link=no, province du Haut-Canada) was a part of British Canada established in 1791 by the Kingdom of Great Britain, to govern the central third of the lands in British North America, formerly part of the ...

, to tutor the children of Richard Cartwright. He applied to the pulpit of a Presbyterian church in Montreal but did not receive the position. He then became an Anglican minister and became a minister for a church in Cornwall, Ontario

Cornwall is a city in Eastern Ontario, Canada, situated where the provinces of Central Canada, Ontario and Quebec and the state of New York (state), New York converge. It is the seat of the United Counties of Stormont, Dundas and Glengarry, Unit ...

.

Strachan taught at a grammar school which was attended by the Upper Canadian elite. He married Ann McGill née Wood, widow of Andrew McGill, in 1807. Together they had nine children, some of whom died young.

York and the War of 1812

York, Upper Canada

York was a town and second capital of the colony of Upper Canada. It is the predecessor to the old city of Toronto (1834–1998). It was established in 1793 by Lieutenant-Governor John Graves Simcoe as a "temporary" location for the capital of ...

, just before the War of 1812

The War of 1812 (18 June 1812 – 17 February 1815) was fought by the United States of America and its indigenous allies against the United Kingdom and its allies in British North America, with limited participation by Spain in Florida. It bega ...

, where he became rector of St. James' Church (which would later become his cathedral) and headmaster of the Home District Grammar School. This school, also known as "The Blue School," taught students from five to seventeen and emphasized a practical means of learning. Students recited abridged speeches from the House of Commons, learned Latin, and were encouraged to ask questions of their fellow pupils.

A conservative, Strachan supported his nation during the War of 1812, using his sermons to support the suspension of civil liberties. Upon hearing that of the fall of Fort Detroit to British forces, Strachan declared in a sermon: "The brilliant victory... has been of infinite service in confirming the wavering & adding spirit to the loyal". Strachan had the young women of York knit flags for the militia regiments in which their menfolk were serving in and organized fundraising drives to give the militiamen serving on the Niagara frontier shoes and clothing.

In December 1812, Strachan founded the Loyal and Patriotic Society of Upper Canada which raised £21,500 to support the families of militiaman and care for the wounded. During the Battle of York in 1813, along with senior militia officers, Strachan negotiated the surrender of the city with American

American(s) may refer to:

* American, something of, from, or related to the United States of America, commonly known as the "United States" or "America"

** Americans, citizens and nationals of the United States of America

** American ancestry, pe ...

general Henry Dearborn

Henry Dearborn (February 23, 1751 – June 6, 1829) was an American military officer and politician. In the Revolutionary War, he served under Benedict Arnold in his expedition to Quebec, of which his journal provides an important record ...

. The Americans violated the terms by looting homes and churches and locked the wounded British soldiers and Upper Canada militiamen into a hospital without food or water for two days. Strachan went to meet to complain in person to Dearborn about the violation of the terms of surrender and shamed Dearborn into imposing order on his troops. He is credited with saving the city from American troops, eager to loot and burn it.

After the sack of York, Strachan sent his wife Anne and their children to Cornwall because he believed they would be safe there. A few months later, Cornwall was taken by the Americans, who looted the Strachan home and likely raped a then-pregnant Anne Strachan.

Family Compact

After the war, he became a pillar of theFamily Compact

The Family Compact was a small closed group of men who exercised most of the political, economic and judicial power in Upper Canada (today’s Ontario) from the 1810s to the 1840s. It was the Upper Canadian equivalent of the Château Clique in ...

, the conservative elite that controlled the colony. He was a member of the Executive Council of Upper Canada

The Executive Council of Upper Canada had a similar function to the Cabinet in England but was not responsible to the Legislative Assembly. Members of the Executive Council were not necessarily members of the Legislative Assembly but were usually ...

from 1815 to 1836 as well as the Legislative Council from 1820 to 1841. He was an influential advisor to the Lieutenant-Governors of Upper Canada and the other members of the Councils and Assemblies, many of whom were his former students. The "Family Compact

The Family Compact was a small closed group of men who exercised most of the political, economic and judicial power in Upper Canada (today’s Ontario) from the 1810s to the 1840s. It was the Upper Canadian equivalent of the Château Clique in ...

" were the elite who shared his fierce loyalty to the British monarchy

The monarchy of the United Kingdom, commonly referred to as the British monarchy, is the constitutional form of government by which a hereditary sovereign reigns as the head of state of the United Kingdom, the Crown Dependencies (the Bailiwi ...

, his strict and exclusive Tory

A Tory () is a person who holds a political philosophy known as Toryism, based on a British version of traditionalism and conservatism, which upholds the supremacy of social order as it has evolved in the English culture throughout history. The ...

ism and the established church (Anglicanism

Anglicanism is a Western Christian tradition that has developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the context of the Protestant Reformation in Europe. It is one of the ...

), and his contempt for slavery

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

, Presbyterians, Methodists, American republicanism

The values, ideals and concept of republicanism have been discussed and celebrated throughout the history of the United States. As the United States has no formal hereditary ruling class, ''republicanism'' in this context does not refer to a ...

, and reformism

Reformism is a political doctrine advocating the reform of an existing system or institution instead of its abolition and replacement.

Within the socialist movement, reformism is the view that gradual changes through existing institutions can eve ...

. Strachan was a leader of anti-American elements, which he saw as a republican and democratic threat that promised chaos and an end to a well-ordered society. In 1822 he was appointed an honorary member of the Bank of Upper Canada.

Strachan invented the "militia myth" to the effect that the local militia had done more to defend Canada than the British Army

The British Army is the principal land warfare force of the United Kingdom, a part of the British Armed Forces along with the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. , the British Army comprises 79,380 regular full-time personnel, 4,090 Gurk ...

, which has been rejected by Canadian historians.

Strachan supported a strict interpretation of the Constitutional Act of 1791

The Clergy Endowments (Canada) Act 1791, commonly known as the Constitutional Act 1791 (), was an Act of the Parliament of Great Britain which passed under George III. The current short title has been in use since 1896.

History

The act refor ...

, claiming that clergy reserves Clergy reserves were tracts of land in Upper Canada and Lower Canada reserved for the support of "Protestant clergy" by the Constitutional Act of 1791. One-seventh of all surveyed Crown lands were set aside, totaling and respectively for each Prov ...

were to be given to the Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Britain ...

alone, rather than to Protestants

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century against what its followers perceived to b ...

in general. In 1826, his interpretation was opposed by Egerton Ryerson, who advocated the separation of church and state and argued that the reserves should be sold for the benefit of education in the province. Although Strachan long controlled the reserves through the Clergy Corporation {{One source, date=June 2009

The Clergy Corporation, or the Clergy Reserve Corporation of Upper Canada, existed to oversee, manage and lease the Clergy reserves of Upper Canada, a large amount of land in Upper Canada that had been put aside for the ...

, he was ultimately forced to oversee the selling off of most of the land in 1854.

Educational interests

Much of Strachan's life and work was focused on education. He wanted Upper Canada to be under Church of England control to avoid American influence. He tried to set up annual reviews for

Much of Strachan's life and work was focused on education. He wanted Upper Canada to be under Church of England control to avoid American influence. He tried to set up annual reviews for grammar school

A grammar school is one of several different types of school in the history of education in the United Kingdom and other English-speaking countries, originally a school teaching Latin, but more recently an academically oriented secondary school ...

s to make sure they were following Church of England doctrines and tried to introduce Andrew Bell's education system from Britain, but those acts were vetoed by the Legislative Assembly. In 1827 Strachan chartered King's College, an Anglican university, although it was not actually created until 1843.

In 1839, he was consecrated the first Anglican bishop of Toronto

Toronto ( ; or ) is the capital city of the Canadian province of Ontario. With a recorded population of 2,794,356 in 2021, it is the most populous city in Canada and the fourth most populous city in North America. The city is the ancho ...

alongside Aubrey Spencer

Aubrey George Spencer (8 February 1795 – 24 February 1872)''DEATH OF THE BISHOP OF JAMAICA'' The Morning Post (London, England), Monday, 26 February 1872; pg. 6; Issue 30645 was the first bishop of the Anglican Diocese of Newfoundland and Ber ...

, the first Bishop of Newfoundland, at Lambeth Palace

Lambeth Palace is the official London residence of the Archbishop of Canterbury. It is situated in north Lambeth, London, on the south bank of the River Thames, south-east of the Palace of Westminster, which houses Parliament, on the opposite ...

August 4. He founded Trinity College Trinity College may refer to:

Australia

* Trinity Anglican College, an Anglican coeducational primary and secondary school in , New South Wales

* Trinity Catholic College, Auburn, a coeducational school in the inner-western suburbs of Sydney, New ...

in 1851 after King's College was secularized as the University of Toronto

The University of Toronto (UToronto or U of T) is a public research university in Toronto, Ontario, Canada, located on the grounds that surround Queen's Park. It was founded by royal charter in 1827 as King's College, the first institution ...

.

In 1835, he was forced to resign from the Executive Council, and he resigned from politics in 1841 after the Act of Union. He continued to influence his former students although the Family Compact declined in the new Province of Canada

The Province of Canada (or the United Province of Canada or the United Canadas) was a British North America, British colony in North America from 1841 to 1867. Its formation reflected recommendations made by John Lambton, 1st Earl of Durham ...

. Strachan helped organize the Lambeth Conference

The Lambeth Conference is a decennial assembly of bishops of the Anglican Communion convened by the Archbishop of Canterbury. The first such conference took place at Lambeth in 1867.

As the Anglican Communion is an international association ...

of Anglican bishops in 1867 but died that year before it was held. Strachan was buried in a vault in the chancel of St. James' Cathedral. He was succeeded by Alexander Neil Bethune

Alexander Neil Bethune (August 28, 1800 – February 3, 1879) was a Church of England clergyman and bishop.

Early and Family Life

The son of the Reverend John Bethune of Williamstown, Ontario, the founding Church of Scotland minister for Upper Ca ...

.

Strachan was elected a member of the American Antiquarian Society

The American Antiquarian Society (AAS), located in Worcester, Massachusetts, is both a learned society and a national research library of pre-twentieth-century American history and culture. Founded in 1812, it is the oldest historical society in ...

in 1846.

First Nations

Strachan was concerned with the Natives and called on people to embrace the "sons of nature" as brothers. He claimed that the United States desired Upper Canada primarily to exterminate the indigenous tribes and free up the West for American expansion. Strachan defended the autonomy of the Natives, the superiority of British governance, and the centrality of Upper Canada in the theatre of war against the US. He rejected the prevalent assumption at the time that Natives were simply pawns in the contest and gave an original and influential explanation of why Upper Canada was vital to both Native and Imperial concerns.High-church views

Strachan was intensely devoted to the promotion of the Anglican position in Canada. He was born a Presbyterian in Scotland, but he never fully accepted it and first received communion at an Anglican church in Kingston. He was strongly influenced by thehigh-church

The term ''high church'' refers to beliefs and practices of Christian ecclesiology, liturgy, and theology that emphasize formality and resistance to modernisation. Although used in connection with various Christian traditions, the term originat ...

bishop of New York, John H. Hobart. Strachan preached that the Anglican Church was a branch of the universal church and that it was independent of both pope and king.

Strachan defended the Church of England from opponents who wanted to reduce its influence in Upper Canada. He published a sermon that said a Christian nation needs a religious establishment, referring to the Anglican church as the establishment. He rejected the notion that clergy reserve Clergy reserves were tracts of land in Upper Canada and Lower Canada reserved for the support of "Protestant clergy" by the Constitutional Act of 1791. One-seventh of all surveyed Crown lands were set aside, totaling and respectively for each Pro ...

s were intended for all Protestant denominations and appealed to the Colonial Office

The Colonial Office was a government department of the Kingdom of Great Britain and later of the United Kingdom, first created to deal with the colonial affairs of British North America but required also to oversee the increasing number of col ...

to maintain that Anglican Church's monopoly on these plots of land.

Like most Protestants of the era, he denounced the Roman Catholic Church for corruption. He rejected the revivalism of the Methodists as an American heresy and stressed the ancient practices and historic liturgy of his church. While a high churchman, Strachan's view alienated many of his clergy and laity who were drawn from the ranks of Irish Protestant immigrants of more low-church persuasion.

Strachan wanted more funds disseminated to build church infrastructure in rural Upper Canada. While fundraising in England his trustworthiness was challenged when he created an Ecclesiastical Chart of the religious statistics of Upper Canada that contained numerous errors. He actively promoted missionary work, using the Diocesan Theological Institute at Cobourg to train clergy to handle frontier conditions. Much of his effort after 1840 was undermined by theological disputes in the church, such as between high-church tractarians and low-church evangelicals. He also faced external attacks from political reformers and rival denominations.

Death and legacy

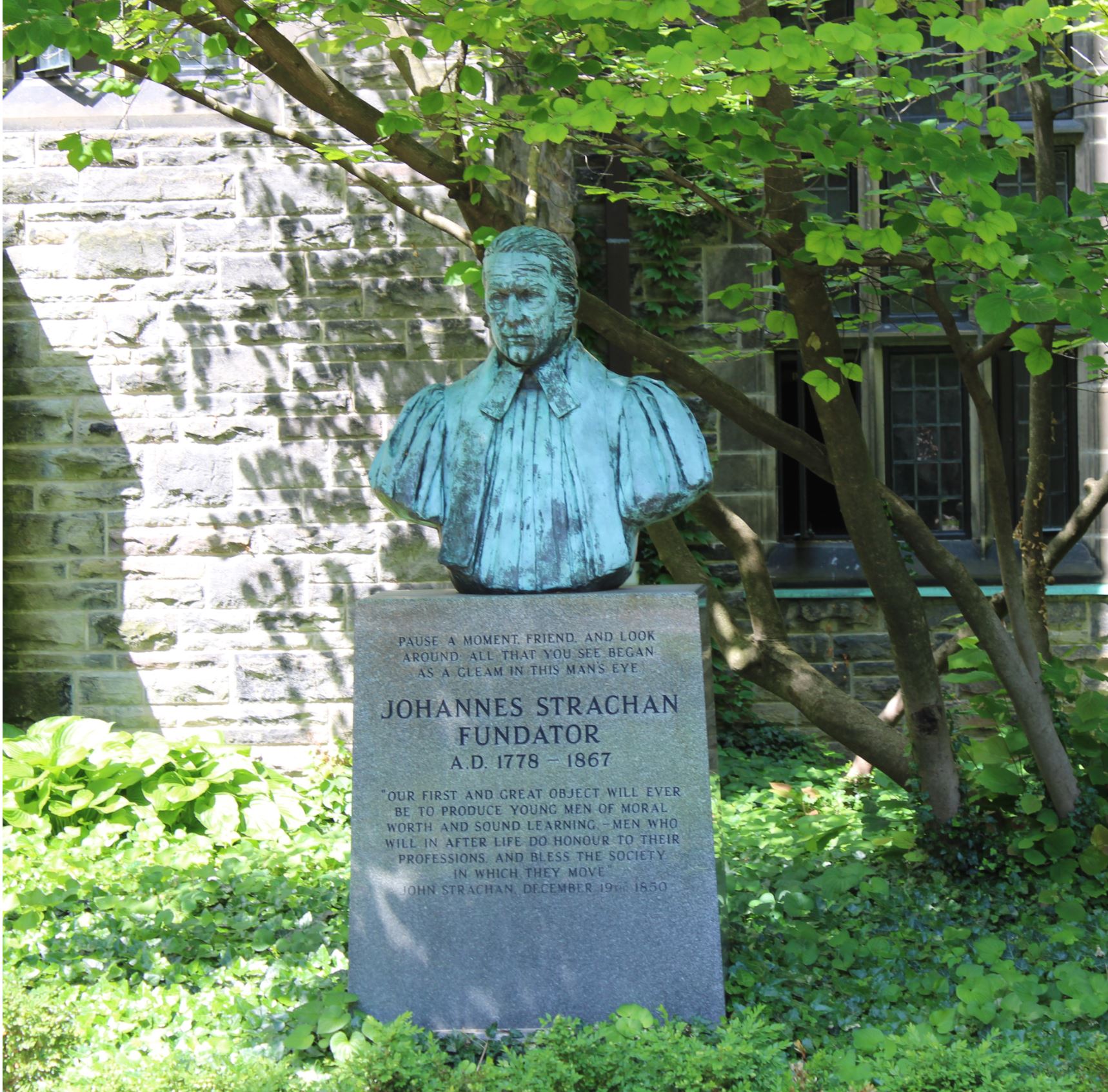

Strachan died on 1 November 1867 in Toronto. His funeral procession took place on November 5, and wound through the city streets from his home at Front and York to St. James Cathedral. A plaque at the University of Toronto erected by the Ontario Archaeological and Historic Sites Board commemorates the residence of Strachan. The Bishop's Palace is the site where assembled the Loyalist forces that defeated William Lyon Mackenzie during the Rebellion of 1837. In the summer of 2004, a bust of John Strachan was erected in the quadrangle of Trinity College at the University of Toronto. Strachan Avenue, running from the original site of Trinity College to Lake Shore Blvd., is also named in his honour.References

Footnotes

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

* * * * * * * * * *External links

Documents by Strachan

from

Project Canterbury Project Canterbury (sometimes abbreviated as PC) is an online archive of material related to the history of Anglicanism. It was founded by Richard Mammana, Jr. in 1999 with a grant from Episcopal Church Presiding Bishop Frank T. Griswold, and is ho ...

Poetry by Strachan

{{DEFAULTSORT:Strachan, John 1778 births 1867 deaths Anglican bishops of Toronto 19th-century Anglican Church of Canada bishops Converts to Anglicanism from Presbyterianism People from Aberdeen People from Old Toronto Pre-Confederation Ontario people Presidents of the University of Toronto Scottish emigrants to pre-Confederation Ontario Alumni of the University of Aberdeen Persons of National Historic Significance (Canada) Members of the American Antiquarian Society Immigrants to Upper Canada Canadian people of the War of 1812