John Smeaton on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

John Smeaton (8 June 1724 – 28 October 1792) was a British

Deciding that he wanted to focus on the lucrative field of civil engineering, he commenced an extensive series of commissions, including:

* the Calder and Hebble Navigation (1758–70)

* Coldstream Bridge over the River Tweed (1763–66)

* Improvements to the River Lee Navigation (1765–70)

* Smeaton's Pier in St Ives, Cornwall (1767–70)

* Perth Bridge over the

Deciding that he wanted to focus on the lucrative field of civil engineering, he commenced an extensive series of commissions, including:

* the Calder and Hebble Navigation (1758–70)

* Coldstream Bridge over the River Tweed (1763–66)

* Improvements to the River Lee Navigation (1765–70)

* Smeaton's Pier in St Ives, Cornwall (1767–70)

* Perth Bridge over the  Smeaton is considered to be the first expert witness to appear in an English court. Because of his expertise in engineering, he was called to testify in court for a case related to the silting-up of the harbour at Wells-next-the-Sea in Norfolk in 1782. He also acted as a consultant on the disastrous 63-year-long New Harbour at

Smeaton is considered to be the first expert witness to appear in an English court. Because of his expertise in engineering, he was called to testify in court for a case related to the silting-up of the harbour at Wells-next-the-Sea in Norfolk in 1782. He also acted as a consultant on the disastrous 63-year-long New Harbour at

It closed in 1839.

Structure Details: Chimney Mill

Smeaton's profile at the BBC

*John Smeaton [http://lhldigital.lindahall.org/cdm/search/searchterm/smeaton!edystone/field/creato!title/mode/all!all/conn/and!and/order/nosort ''A narrative of the building and a description of the construction of the Edystone Lighthouse''] (1791 and 1793 editions) – Linda Hall Library * {{DEFAULTSORT:Smeaton, John 1724 births 1792 deaths Engineers from Yorkshire British bridge engineers English canal engineers Concrete pioneers Lighthouse builders People of the Industrial Revolution Fellows of the Royal Society Recipients of the Copley Medal People educated at Leeds Grammar School Members of the Lunar Society of Birmingham 18th-century English people English mechanical engineers Harbour engineers

civil engineer

A civil engineer is a person who practices civil engineering – the application of planning, designing, constructing, maintaining, and operating infrastructure while protecting the public and environmental health, as well as improving existing ...

responsible for the design of bridges, canal

Canals or artificial waterways are waterways or engineered channels built for drainage management (e.g. flood control and irrigation) or for conveyancing water transport vehicles (e.g. water taxi). They carry free, calm surface fl ...

s, harbour

A harbor (American English), harbour (British English; see spelling differences), or haven is a sheltered body of water where ships, boats, and barges can be docked. The term ''harbor'' is often used interchangeably with ''port'', which is a ...

s and lighthouse

A lighthouse is a tower, building, or other type of physical structure designed to emit light from a system of lamps and lenses and to serve as a beacon for navigational aid, for maritime pilots at sea or on inland waterways.

Lighthouses mar ...

s. He was also a capable mechanical engineer and an eminent physicist. Smeaton was the first self-proclaimed "civil engineer", and is often regarded as the "father of civil engineering

Civil engineering is a professional engineering discipline that deals with the design, construction, and maintenance of the physical and naturally built environment, including public works such as roads, bridges, canals, dams, airports, sewa ...

".Mark Denny (2007). "Ingenium: Five Machines That Changed the World". p. 34. JHU Press. He pioneered the use of hydraulic lime

Hydraulic lime (HL) is a general term for calcium oxide, a variety of lime also called quicklime, that sets by hydration. This contrasts with calcium hydroxide, also called slaked lime or air lime that is used to make lime mortar, the other common ...

in concrete

Concrete is a composite material composed of fine and coarse aggregate bonded together with a fluid cement (cement paste) that hardens (cures) over time. Concrete is the second-most-used substance in the world after water, and is the most ...

, using pebbles and powdered brick as aggregate. Smeaton was associated with the Lunar Society.

Law and physics

Smeaton was born inAusthorpe

Austhorpe is a civil parish and residential suburb of east Leeds, West Yorkshire, England. It is to the east of city centre and close to the A6120 dual carriageway ( Leeds Outer Ring Road) and the M1 motorway.

Location

The area is situa ...

, Leeds, England. After studying at Leeds Grammar School he joined his father's law firm, but left to become a mathematical instrument maker (working with Henry Hindley), developing, among other instruments, a pyrometer to study material expansion. In 1750, his premises were in the Great Turnstile in Holborn.

He was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1753 and in 1759 won the Copley Medal

The Copley Medal is an award given by the Royal Society, for "outstanding achievements in research in any branch of science". It alternates between the physical sciences or mathematics and the biological sciences. Given every year, the medal is t ...

for his research into the mechanics of waterwheel

A water wheel is a machine for converting the energy of flowing or falling water into useful forms of power, often in a watermill. A water wheel consists of a wheel (usually constructed from wood or metal), with a number of blades or buckets ...

s and windmills. His 1759 paper "An Experimental Enquiry Concerning the Natural Powers of Water and Wind to Turn Mills and Other Machines Depending on Circular Motion" addressed the relationship between pressure and velocity for objects moving in air (Smeaton noted that the table doing so was actually contributed by "my friend Mr Rouse" "an ingenious gentleman of Harborough, Leicestershire" and calculated on the basis of Rouse's experiments), and his concepts were subsequently developed to devise the 'Smeaton Coefficient'. Smeaton's water wheel experiments were conducted on a small scale model with which he tested various configurations over a period of seven years. The resultant increase in efficiency in water power contributed to the Industrial Revolution.

Over the period 1759–1782 he performed a series of further experiments and measurements on water wheels that led him to support and champion the '' vis viva'' theory of German Gottfried Leibniz

Gottfried Wilhelm (von) Leibniz . ( – 14 November 1716) was a German polymath active as a mathematician, philosopher, scientist and diplomat. He is one of the most prominent figures in both the history of philosophy and the history of mat ...

, an early formulation of conservation of energy

In physics and chemistry, the law of conservation of energy states that the total energy of an isolated system remains constant; it is said to be ''conserved'' over time. This law, first proposed and tested by Émilie du Châtelet, means th ...

. This led him into conflict with members of the academic establishment who rejected Leibniz's theory, believing it inconsistent with Sir Isaac Newton's conservation of momentum.

Smeaton coefficient

In his 1759 paper "An Experimental Enquiry Concerning the Natural Powers of Water and Wind to Turn Mills and Other Machines Depending on Circular Motion" Smeaton developed the concepts and data which became the basis for the ''Smeaton coefficient'', the lift equation used by the Wright brothers. It has the form: : where: : is the lift : is the Smeaton coefficient (see note below) : is the velocity : is the area in square feet : is the lift coefficient (the lift relative to the drag of a plate of the same area) The Wright brothers determined with wind tunnels that the Smeaton coefficient value of 0.005 was incorrect and should have been 0.0033. In modern analysis, the lift coefficient is normalised by the dynamic pressure instead of the Smeaton coefficient.Civil engineering

Smeaton is important in the history, rediscovery of, and development of moderncement

A cement is a binder, a chemical substance used for construction that sets, hardens, and adheres to other materials to bind them together. Cement is seldom used on its own, but rather to bind sand and gravel (aggregate) together. Cement m ...

, identifying the compositional requirements needed to obtain "hydraulicity" in lime; work which led ultimately to the invention of Portland cement. Portland cement led to the re-emergence of concrete as a modern building material, largely due to Smeaton's influence.

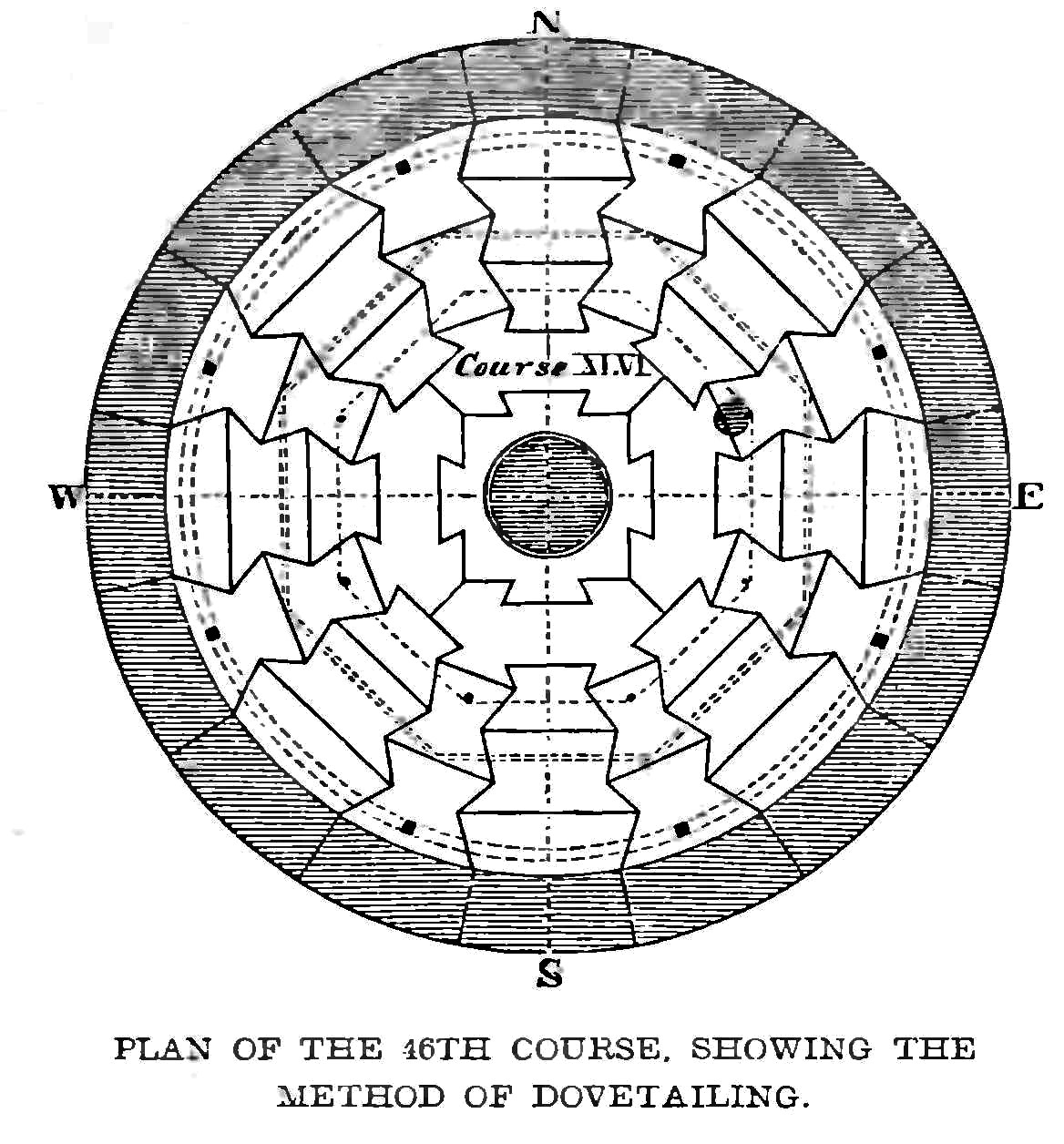

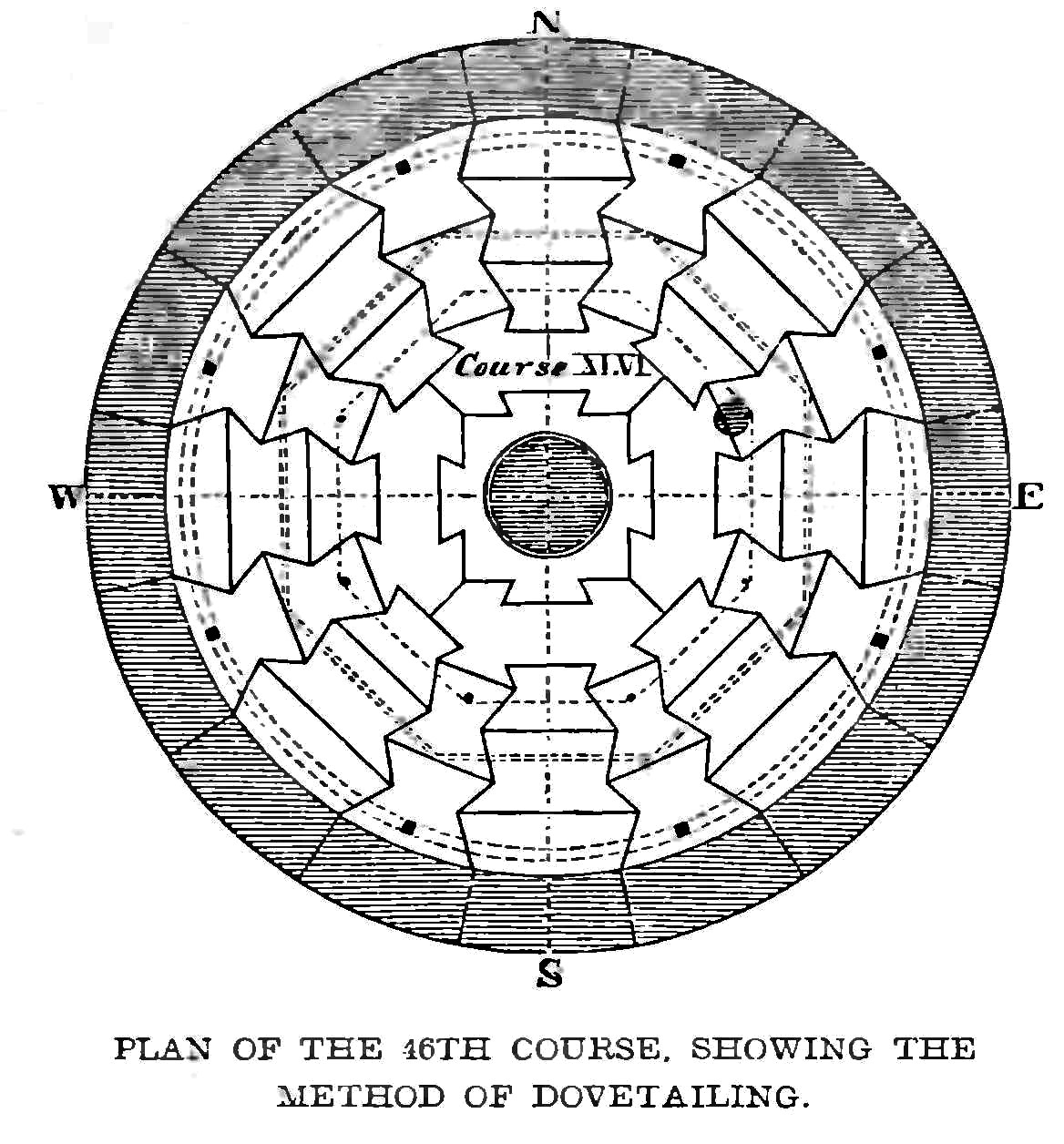

Recommended by the Royal Society, Smeaton designed the third Eddystone Lighthouse (1755–59). He pioneered the use of 'hydraulic lime

Hydraulic lime (HL) is a general term for calcium oxide, a variety of lime also called quicklime, that sets by hydration. This contrasts with calcium hydroxide, also called slaked lime or air lime that is used to make lime mortar, the other common ...

' (a form of mortar that will set under water) and developed a technique involving dovetailed blocks of granite in the building of the lighthouse. His lighthouse remained in use until 1877 when the rock underlying the structure's foundations had begun to erode; it was dismantled and partially rebuilt at Plymouth Hoe where it is known as Smeaton's Tower.

Deciding that he wanted to focus on the lucrative field of civil engineering, he commenced an extensive series of commissions, including:

* the Calder and Hebble Navigation (1758–70)

* Coldstream Bridge over the River Tweed (1763–66)

* Improvements to the River Lee Navigation (1765–70)

* Smeaton's Pier in St Ives, Cornwall (1767–70)

* Perth Bridge over the

Deciding that he wanted to focus on the lucrative field of civil engineering, he commenced an extensive series of commissions, including:

* the Calder and Hebble Navigation (1758–70)

* Coldstream Bridge over the River Tweed (1763–66)

* Improvements to the River Lee Navigation (1765–70)

* Smeaton's Pier in St Ives, Cornwall (1767–70)

* Perth Bridge over the River Tay

The River Tay ( gd, Tatha, ; probably from the conjectured Brythonic ''Tausa'', possibly meaning 'silent one' or 'strong one' or, simply, 'flowing') is the longest river in Scotland and the seventh-longest in Great Britain. The Tay originates ...

in Perth (1766–71)

* Ripon Canal (1766–1773)

* Smeaton's Viaduct

A viaduct is a specific type of bridge that consists of a series of arches, piers or columns supporting a long elevated railway or road. Typically a viaduct connects two points of roughly equal elevation, allowing direct overpass across a wide v ...

, which carries the A616 road (part of the original Great North Road) over the River Trent between Newark and South Muskham in Nottinghamshire (1768–70)

* the Forth and Clyde Canal from Grangemouth

Grangemouth ( sco, Grangemooth; gd, Inbhir Ghrainnse, ) is a town in the Falkirk council area, Scotland. Historically part of the county of Stirlingshire, the town lies in the Forth Valley, on the banks of the Firth of Forth, east of Falkirk ...

to Glasgow

Glasgow ( ; sco, Glesca or ; gd, Glaschu ) is the most populous city in Scotland and the fourth-most populous city in the United Kingdom, as well as being the 27th largest city by population in Europe. In 2020, it had an estimated pop ...

(1768–77)

* Langley on Tyne

Langley or Langley-on-Tyne is a small village in Northumberland, England, located to the west of Hexham.

The village is on the A686 about south of Haydon Bridge. The skyline of Langley on Tyne is still dominated by the lead smelting chimney w ...

smelt mill, with Nicholas Walton, acting as receivers to the Greenwich Hospital, London (1768)

* Banff harbour (1770–75)

* Lower North Water Bridge

The Lower North Water Bridge is a road bridge north of Montrose, Scotland. It carries the A92 over the River North Esk. It is situated on the border between Angus and Aberdeenshire. It is adjacent to the North Water Viaduct which previously carri ...

(1770–75)

* Aberdeen

Aberdeen (; sco, Aiberdeen ; gd, Obar Dheathain ; la, Aberdonia) is a city in North East Scotland, and is the third most populous city in the country. Aberdeen is one of Scotland's 32 local government council areas (as Aberdeen City), ...

bridge (1775–80)

* Peterhead harbour (1775–1881)

* Nent Force Level (1776–77)

* Cardington Bridge (1778)

* Harbour works at Ramsgate

Ramsgate is a seaside resort, seaside town in the district of Thanet District, Thanet in east Kent, England. It was one of the great English seaside towns of the 19th century. In 2001 it had a population of about 40,000. In 2011, according to t ...

(retention basin 1776–83; jetty 1788–1792)

* Hexham Bridge (1777–90); completed by Robert Mylne in 1793

* the Birmingham and Fazeley Canal (1782–89)

*St Austell

St Austell (; kw, Sans Austel) is a town in Cornwall, England, south of Bodmin and west of the border with Devon.

St Austell is one of the largest towns in Cornwall; at the 2011 census it had a population of 19,958.

History

St Austell wa ...

's Charlestown harbour in Cornwall (1792)

Smeaton is considered to be the first expert witness to appear in an English court. Because of his expertise in engineering, he was called to testify in court for a case related to the silting-up of the harbour at Wells-next-the-Sea in Norfolk in 1782. He also acted as a consultant on the disastrous 63-year-long New Harbour at

Smeaton is considered to be the first expert witness to appear in an English court. Because of his expertise in engineering, he was called to testify in court for a case related to the silting-up of the harbour at Wells-next-the-Sea in Norfolk in 1782. He also acted as a consultant on the disastrous 63-year-long New Harbour at Rye

Rye (''Secale cereale'') is a grass grown extensively as a grain, a cover crop and a forage crop. It is a member of the wheat tribe (Triticeae) and is closely related to both wheat (''Triticum'') and barley (genus ''Hordeum''). Rye grain is u ...

, designed to combat the silting of the port of Winchelsea. The project is now known informally as "Smeaton's Harbour", but despite the name his involvement was limited and occurred more than 30 years after work on the harbour commenced.Rye Museum websiteIt closed in 1839.

Mechanical engineer

Employing his skills as a mechanical engineer, he devised awater engine

The water engine is a positive-displacement engine, often closely resembling a steam engine with similar pistons and valves, that is driven by water pressure. The supply of water was derived from a natural head of water, the water mains, or a sp ...

for the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew in 1761 and a watermill at Alston, Cumbria in 1767 (he is credited by some with inventing the cast-iron axle shaft for water wheels). In 1782 he built the Chimney Mill at Spital Tongues in Newcastle upon Tyne, the first 5-sailed smock mill in Britain. He also improved Thomas Newcomen's atmospheric engine

The atmospheric engine was invented by Thomas Newcomen in 1712, and is often referred to as the Newcomen fire engine (see below) or simply as a Newcomen engine. The engine was operated by condensing steam drawn into the cylinder, thereby creati ...

, erecting one at Chacewater mine, Wheal Busy, in Cornwall in 1775.

In 1789 Smeaton applied an idea by Denis Papin, by using a force pump to maintain the pressure and fresh air inside a diving bell

A diving bell is a rigid chamber used to transport divers from the surface to depth and back in open water, usually for the purpose of performing underwater work. The most common types are the open-bottomed wet bell and the closed bell, which c ...

. This bell, built for the Hexham Bridge project, was not intended for underwater work, but in 1790 the design was updated to enable it to be used underwater on the breakwater at Ramsgate Harbour. Smeaton is also credited with explaining the fundamental differences and benefits of overshot versus undershot water wheels. Smeaton experimented with the Newcomen steam engine and made marked improvements around the time James Watt

James Watt (; 30 January 1736 (19 January 1736 OS) – 25 August 1819) was a Scottish inventor, mechanical engineer, and chemist who improved on Thomas Newcomen's 1712 Newcomen steam engine with his Watt steam engine in 1776, which was fun ...

was building his first engines ().

Legacy

Smeaton died after suffering a stroke while walking in the garden of his family home at Austhorpe, and was buried in the parish church at Whitkirk, West Yorkshire. His surviving daughters erected a memorial to him and his wife which is on thechancel

In church architecture, the chancel is the space around the altar, including the choir and the sanctuary (sometimes called the presbytery), at the liturgical east end of a traditional Christian church building. It may terminate in an apse.

...

wall of the church.

Due to the decay of the rock beneath the Eddystone Lighthouse the structure needed to be replaced. When the upper section of Smeaton's lighthouse (which included the lantern, store and living and watch room) was about to be removed, it was suggested that some of it be brought to Whitkirk and set up as a memorial to him. Unfortunately, the project was deemed too expensive as it was estimated that it would cost around £1800.

He is highly regarded by other engineers, having contributed to the Lunar Society and founded the Society of Civil Engineers

The Smeatonian Society of Civil Engineers was founded in England in 1771. It was the first engineering society to be formed anywhere in the world, and remains the oldest. It was originally known as the Society of Civil Engineers, being renamed fo ...

in 1771. He coined the term ''civil engineers

This list of civil engineers is a list of notable people who have been trained in or have practiced civil engineering.

A

B

C

D

E

F

G

H

I

J

K

L

M

N

O

P

Q

R

S

T

U

...

'' to distinguish them from military engineers graduating from the Royal Military Academy at Woolwich. The Society was a forerunner of the Institution of Civil Engineers, established in 1818, and was renamed the Smeatonian Society of Civil Engineers in 1830. His pupils included canal engineer William Jessop and architect and engineer Benjamin Latrobe.

The pioneering constant of proportionality describing pressure varying inversely as the square of the velocity when applied to objects moving in air was named ''Smeaton's coefficient'' in his honor. Based on his concepts and data, it was used by the Wright brothers in their pursuit of the first successful heavier-than-air aircraft.

Between 1860 and 1894 the design of the reverse side of the old penny coin showed (behind Britannia

Britannia () is the national personification of Britain as a helmeted female warrior holding a trident and shield. An image first used in classical antiquity, the Latin ''Britannia'' was the name variously applied to the British Isles, Gr ...

) a depiction of Smeaton’s Eddystone lighthouse.

Smeaton is one of six civil engineers depicted in the Stephenson

Stephenson is a medieval patronymic surname meaning "son of Stephen". The earliest public record is found in the county of Huntingdonshire in 1279. There are variant spellings including Stevenson. People with the surname include:

*Ashley Stephen ...

stained glass window, designed by William Wailes and unveiled in Westminster Abbey in 1862. A memorial stone commemorating Smeaton himself was unveiled in the Abbey on 7 November 1994, by Noel Ordman, President of the Smeatonian Society of Civil Engineers.

John Smeaton Academy

John Smeaton Academy is a co-educational secondary school located in Leeds, West Yorkshire, England.

The school educates children aged 11–18 from across Leeds and its surrounding villages including Scholes, Cross Gates, Barwick-in-Elmet, Pe ...

, a secondary school in the suburbs of Leeds adjacent to the Pendas Fields estate near Austhorpe, is named after Smeaton. He is also commemorated at the University of Plymouth, where the Mathematics and Technology Department is housed in a building named after him. A viaduct in the final stage of the Leeds Inner Ring Road, opened in 2008, was named after him.

In 2003 Smeaton was named among the top 10 technological innovators in '' Human Accomplishment: The Pursuit of Excellence in the Arts and Sciences, 800 B.C. to 1950''. He is mentioned in the song " I Predict a Riot" (as a symbol of a more dignified and peaceful epoch in Leeds history; and in reference to a Junior School House at Leeds Grammar School, which lead singer Ricky Wilson attended) by the indie rock band Kaiser Chiefs, who are natives of Leeds.

Works

* * ''A Narrative Of The Building And A Description Of The Construction Of The Edystone Lighthouse With Stone''. London: H. Hughs. 1791. * Account of an observation of the night ascension and declination of Mercury : out of the meridian, near his greatest elongation. London. 1787. * Description of an improvement in the application of the quadrant of altitude to a celestial globe, for the resolution of problems dependant on azimuth and altitude. 1789.See also

* Canals of the United Kingdom *History of the British canal system

History (derived ) is the systematic study and the documentation of the human activity. The time period of event before the invention of writing systems is considered prehistory. "History" is an umbrella term comprising past events as well ...

Further reading

* Skempton, A.W. d. ''John Smeaton FRS'', ICE Publishing (1991) LondonReferences

External links

* *Structure Details: Chimney Mill

Smeaton's profile at the BBC

*John Smeaton [http://lhldigital.lindahall.org/cdm/search/searchterm/smeaton!edystone/field/creato!title/mode/all!all/conn/and!and/order/nosort ''A narrative of the building and a description of the construction of the Edystone Lighthouse''] (1791 and 1793 editions) – Linda Hall Library * {{DEFAULTSORT:Smeaton, John 1724 births 1792 deaths Engineers from Yorkshire British bridge engineers English canal engineers Concrete pioneers Lighthouse builders People of the Industrial Revolution Fellows of the Royal Society Recipients of the Copley Medal People educated at Leeds Grammar School Members of the Lunar Society of Birmingham 18th-century English people English mechanical engineers Harbour engineers