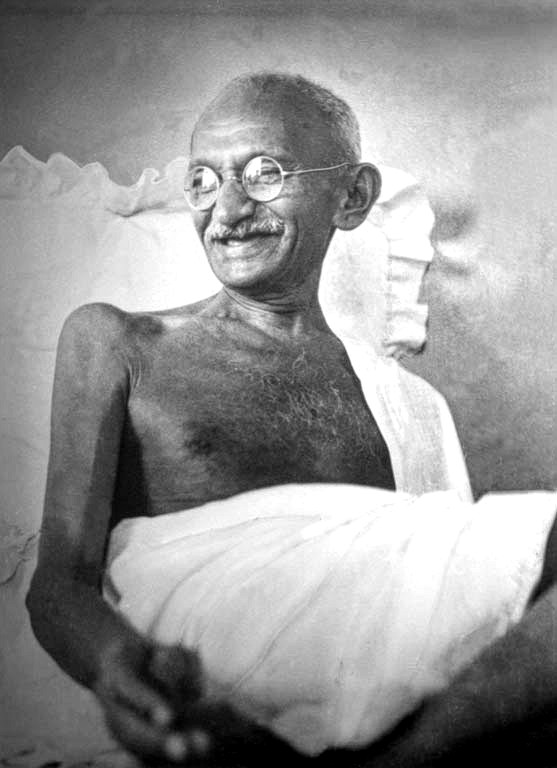

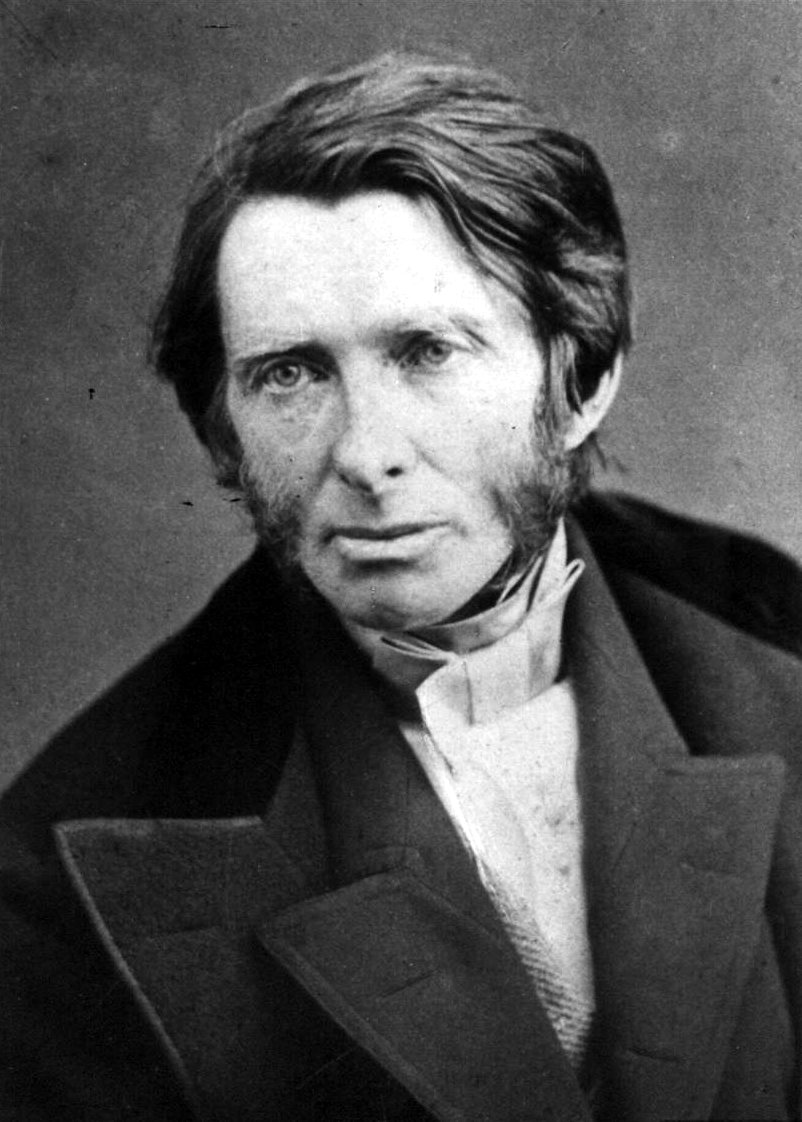

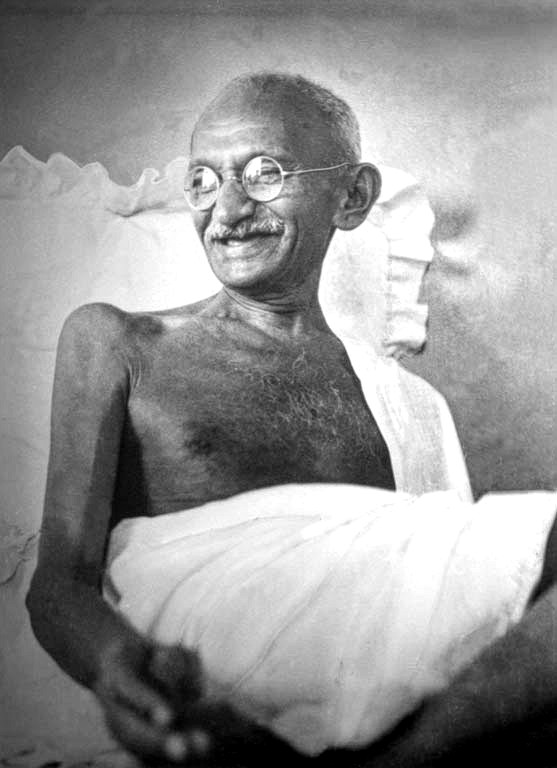

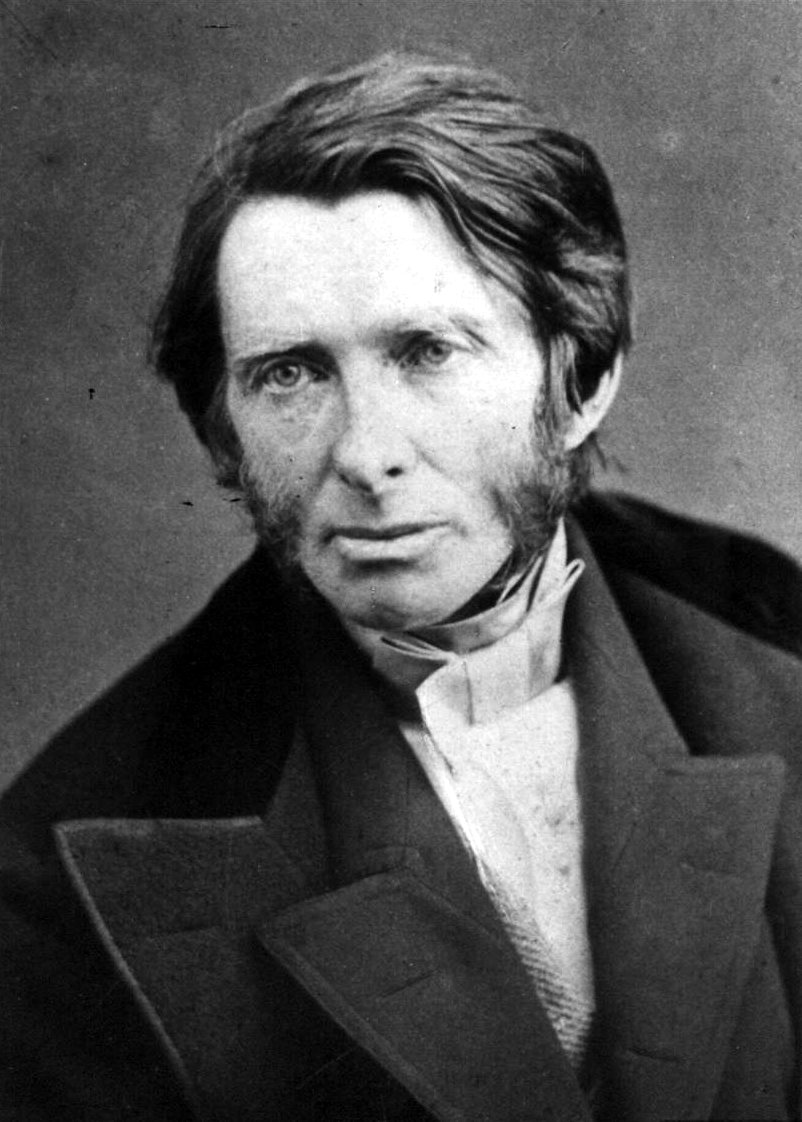

John Ruskin (8 February 1819 20 January 1900) was an

English

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

** English national ide ...

writer,

philosopher

A philosopher is a person who practices or investigates philosophy. The term ''philosopher'' comes from the grc, φιλόσοφος, , translit=philosophos, meaning 'lover of wisdom'. The coining of the term has been attributed to the Greek th ...

,

art critic

An art critic is a person who is specialized in analyzing, interpreting, and evaluating art. Their written critiques or reviews contribute to art criticism and they are published in newspapers, magazines, books, exhibition brochures, and catalogue ...

and

polymath

A polymath ( el, πολυμαθής, , "having learned much"; la, homo universalis, "universal human") is an individual whose knowledge spans a substantial number of subjects, known to draw on complex bodies of knowledge to solve specific pro ...

of the

Victorian era

In the history of the United Kingdom and the British Empire, the Victorian era was the period of Queen Victoria's reign, from 20 June 1837 until her death on 22 January 1901. The era followed the Georgian period and preceded the Edwardia ...

. He wrote on subjects as varied as

geology

Geology () is a branch of natural science concerned with Earth and other astronomical objects, the features or rocks of which it is composed, and the processes by which they change over time. Modern geology significantly overlaps all other Ear ...

,

architecture

Architecture is the art and technique of designing and building, as distinguished from the skills associated with construction. It is both the process and the product of sketching, conceiving, planning, designing, and constructing building ...

,

myth

Myth is a folklore genre consisting of Narrative, narratives that play a fundamental role in a society, such as foundational tales or Origin myth, origin myths. Since "myth" is widely used to imply that a story is not Objectivity (philosophy), ...

,

ornithology

Ornithology is a branch of zoology that concerns the "methodological study and consequent knowledge of birds with all that relates to them." Several aspects of ornithology differ from related disciplines, due partly to the high visibility and th ...

,

literature

Literature is any collection of written work, but it is also used more narrowly for writings specifically considered to be an art form, especially prose fiction, drama, and poetry. In recent centuries, the definition has expanded to include ...

,

education

Education is a purposeful activity directed at achieving certain aims, such as transmitting knowledge or fostering skills and character traits. These aims may include the development of understanding, rationality, kindness, and honesty. Va ...

,

botany

Botany, also called , plant biology or phytology, is the science of plant life and a branch of biology. A botanist, plant scientist or phytologist is a scientist who specialises in this field. The term "botany" comes from the Ancient Greek w ...

and

political economy

Political economy is the study of how Macroeconomics, economic systems (e.g. Marketplace, markets and Economy, national economies) and Politics, political systems (e.g. law, Institution, institutions, government) are linked. Widely studied ph ...

.

Ruskin's writing styles and literary forms were equally varied. He wrote essays and

treatises

A treatise is a formal and systematic written discourse on some subject, generally longer and treating it in greater depth than an essay, and more concerned with investigating or exposing the principles of the subject and its conclusions."Treat ...

, poetry and lectures, travel guides and manuals, letters and even

a fairy tale. He also made detailed sketches and paintings of rocks, plants, birds, landscapes, architectural structures and ornamentation. The elaborate style that characterised his earliest writing on art gave way in time to plainer language designed to communicate his ideas more effectively. In all of his writing, he emphasised the connections between nature, art and society.

Ruskin was hugely influential in the latter half of the 19th century and up to the

First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

. After a period of relative decline, his reputation has steadily improved since the 1960s with the publication of numerous academic studies of his work. Today, his ideas and concerns are widely recognised as having anticipated interest in

environmentalism

Environmentalism or environmental rights is a broad philosophy, ideology, and social movement regarding concerns for environmental protection and improvement of the health of the environment, particularly as the measure for this health seek ...

,

sustainability

Specific definitions of sustainability are difficult to agree on and have varied in the literature and over time. The concept of sustainability can be used to guide decisions at the global, national, and individual levels (e.g. sustainable livi ...

and

craft

A craft or trade is a pastime or an occupation that requires particular skills and knowledge of skilled work. In a historical sense, particularly the Middle Ages and earlier, the term is usually applied to people occupied in small scale prod ...

.

Ruskin first came to widespread attention with the first volume of ''

Modern Painters

''Modern Painters'' (1843–1860) is a five-volume work by the Victorian art critic, John Ruskin, begun when he was 24 years old based on material collected in Switzerland in 1842. Ruskin argues that recent painters emerging from the tradition of ...

'' (1843), an extended essay in defence of the work of

J. M. W. Turner in which he argued that the principal role of the artist is "truth to nature". From the 1850s, he championed the

Pre-Raphaelites, who were influenced by his ideas. His work increasingly focused on social and political issues. ''

Unto This Last ''Unto This Last'' is an essay critical of economics by John Ruskin, first published between August and December 1860 in the monthly journal ''Cornhill Magazine'' in four articles.

Title

The title is a quotation from the Parable of the Workers i ...

'' (1860, 1862) marked the shift in emphasis. In 1869, Ruskin became the first

Slade Professor of Fine Art

The Slade Professorship of Fine Art is the oldest professorship of art and art history at the universities of Cambridge, Oxford and University College, London.

History

The chairs were founded concurrently in 1869 by a bequest from the art collecto ...

at the

University of Oxford

, mottoeng = The Lord is my light

, established =

, endowment = £6.1 billion (including colleges) (2019)

, budget = £2.145 billion (2019–20)

, chancellor ...

, where he established the

Ruskin School of Drawing

The Ruskin School of Art, known as the Ruskin, is an art school at the University of Oxford, England. It is part of Oxford's Humanities Division.

History

The Ruskin grew out the Oxford School of Art, which was founded in 1865 and later became ...

. In 1871, he began his monthly "letters to the workmen and labourers of Great Britain", published under the title ''

Fors Clavigera'' (1871–1884). In the course of this complex and deeply personal work, he developed the principles underlying his ideal society. As a result, he founded the

Guild of St George

The Guild of St George is a charitable Education Trust, based in England but with a worldwide membership, which tries to uphold the values and put into practice the ideas of its founder, John Ruskin (1819–1900).

History

Ruskin, a Victorian ...

, an organisation that endures today.

Early life (1819–1846)

Genealogy

Ruskin was the only child of first cousins.

His father, John James Ruskin (1785–1864), was a sherry and wine importer,

founding partner and ''de facto'' business manager of Ruskin, Telford and Domecq (see

Allied Domecq

Allied Domecq PLC was an international company, headquartered in Bristol, United Kingdom, that operated spirits, wine, and quick service restaurant businesses. It was once a FTSE 100 Index constituent but has been acquired by Pernod Ricard. Th ...

). John James was born and brought up in

Edinburgh

Edinburgh ( ; gd, Dùn Èideann ) is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 Council areas of Scotland, council areas. Historically part of the county of Midlothian (interchangeably Edinburghshire before 1921), it is located in Lothian ...

, Scotland, to a mother from

Glenluce

Glenluce ( gd, Clachan Ghlinn Lus) is a small village in the parish of Old Luce in Wigtownshire, Scotland.

It contains a village shop,a caravan park and a town hall, as well as the parish church.

Location

Glenluce on the A75 road between Stranr ...

and a father originally from

Hertfordshire

Hertfordshire ( or ; often abbreviated Herts) is one of the home counties in southern England. It borders Bedfordshire and Cambridgeshire to the north, Essex to the east, Greater London to the south, and Buckinghamshire to the west. For govern ...

.

His wife, Margaret Cock (1781–1871), was the daughter of a publican in

Croydon

Croydon is a large town in south London, England, south of Charing Cross. Part of the London Borough of Croydon, a local government district of Greater London. It is one of the largest commercial districts in Greater London, with an extensi ...

.

She had joined the Ruskin household when she became companion to John James's mother, Catherine.

John James had hoped to practise law, and was articled as a clerk in London.

His father, John Thomas Ruskin, described as a grocer (but apparently an ambitious wholesale merchant), was an incompetent businessman. To save the family from bankruptcy, John James, whose prudence and success were in stark contrast to his father, took on all debts, settling the last of them in 1832.

John James and Margaret were engaged in 1809, but opposition to the union from John Thomas, and the problem of his debts, delayed the couple's wedding. They finally married, without celebration, in 1818. John James died on 3 March 1864 and is buried in the churchyard of St John the Evangelist, Shirley, Croydon.

Childhood and education

Ruskin was born on 8 February 1819 at 54 Hunter Street,

Brunswick Square

Brunswick Square is a public garden and ancillary streets along two of its sides in Bloomsbury, in the London Borough of Camden. It is overlooked by the School of Pharmacy and the Foundling Museum to the north; the Brunswick Centre to the w ...

, London (demolished 1969), south of

St Pancras railway station.

[''ODNB'' (2004) "Childhood and education"] His childhood was shaped by the contrasting influences of his father and mother, both of whom were fiercely ambitious for him. John James Ruskin helped to develop his son's

Romanticism

Romanticism (also known as the Romantic movement or Romantic era) was an artistic, literary, musical, and intellectual movement that originated in Europe towards the end of the 18th century, and in most areas was at its peak in the approximate ...

. They shared a passion for the works of

Byron

George Gordon Byron, 6th Baron Byron (22 January 1788 – 19 April 1824), known simply as Lord Byron, was an English romantic poet and peer. He was one of the leading figures of the Romantic movement, and has been regarded as among the ...

,

Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 26 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's nation ...

and especially

Walter Scott

Sir Walter Scott, 1st Baronet (15 August 1771 – 21 September 1832), was a Scottish novelist, poet, playwright and historian. Many of his works remain classics of European and Scottish literature, notably the novels ''Ivanhoe'', ''Rob Roy (n ...

. They visited Scott's home,

Abbotsford, in 1838, but Ruskin was disappointed by its appearance. Margaret Ruskin, an

evangelical

Evangelicalism (), also called evangelical Christianity or evangelical Protestantism, is a worldwide Interdenominationalism, interdenominational movement within Protestantism, Protestant Christianity that affirms the centrality of being "bor ...

Christian, more cautious and restrained than her husband, taught young John to read the

Bible

The Bible (from Koine Greek , , 'the books') is a collection of religious texts or scriptures that are held to be sacred in Christianity, Judaism, Samaritanism, and many other religions. The Bible is an anthologya compilation of texts of a ...

from beginning to end, and then to start all over again, committing large portions to memory. Its language, imagery and parables had a profound and lasting effect on his writing. He later wrote:

Ruskin's childhood was spent from 1823 at 28

Herne Hill

Herne Hill is a district in South London, approximately four miles from Charing Cross and bordered by Brixton, Camberwell, Dulwich, and Tulse Hill. It sits to the north and east of Brockwell Park and straddles the boundary between the borou ...

(demolished ), near the village of

Camberwell

Camberwell () is a district of South London, England, in the London Borough of Southwark, southeast of Charing Cross.

Camberwell was first a village associated with the church of St Giles and a common of which Goose Green is a remnant. This e ...

in

South London

South London is the southern part of London, England, south of the River Thames. The region consists of the Districts of England, boroughs, in whole or in part, of London Borough of Bexley, Bexley, London Borough of Bromley, Bromley, London Borou ...

. He had few friends of his own age, but it was not the friendless and toyless experience he later said it was in his autobiography, ''Praeterita'' (1885–89).

He was educated at home by his parents and private tutors, including

Congregationalist preacher Edward Andrews, whose daughters, Mrs Eliza Orme and

Emily Augusta Patmore

Emily Augusta Patmore ( Andrews; 29 February 1824 – 5 July 1862) was a British author, Pre-Raphaelite muse and the inspiration for the 1854-1862 poem ''The Angel in the House''.

Early life and education

Emily Augusta Andrews was born on 29 ...

were later credited with introducing Ruskin to the

Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood

The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (later known as the Pre-Raphaelites) was a group of English painters, poets, and art critics, founded in 1848 by William Holman Hunt, John Everett Millais, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, William Michael Rossetti, James ...

.

From 1834 to 1835 he attended the school in

Peckham

Peckham () is a district in southeast London, within the London Borough of Southwark. It is south-east of Charing Cross. At the United Kingdom Census 2001, 2001 Census the Peckham ward had a population of 14,720.

History

"Peckham" is a Saxon p ...

run by the progressive evangelical

Thomas Dale

Sir Thomas Dale ( 1570 − 19 August 1619) was an English naval commander and deputy-governor of the Virginia Colony in 1611 and from 1614 to 1616. Governor Dale is best remembered for the energy and the extreme rigour of his administration in ...

(1797–1870). Ruskin heard Dale lecture in 1836 at

King's College, London

King's College London (informally King's or KCL) is a public university, public research university located in London, England. King's was established by royal charter in 1829 under the patronage of George IV of the United Kingdom, King G ...

, where Dale was the first Professor of English Literature.

Ruskin went on to enroll and complete his studies at

King's College, where he prepared for

Oxford

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the ...

under Dale's tutelage.

Travel

Ruskin was greatly influenced by the extensive and privileged travels he enjoyed in his childhood. It helped to establish his taste and augmented his education. He sometimes accompanied his father on visits to business clients at their country houses, which exposed him to English landscapes, architecture and paintings. Family tours took them to the

Lake District

The Lake District, also known as the Lakes or Lakeland, is a mountainous region in North West England. A popular holiday destination, it is famous for its lakes, forests, and mountains (or ''fells''), and its associations with William Wordswor ...

(his first long poem, ''Iteriad'', was an account of his tour in 1830) and to relatives in

Perth

Perth is the capital and largest city of the Australian state of Western Australia. It is the fourth most populous city in Australia and Oceania, with a population of 2.1 million (80% of the state) living in Greater Perth in 2020. Perth is ...

, Scotland. As early as 1825, the family visited

France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

and

Belgium

Belgium, ; french: Belgique ; german: Belgien officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a country in Northwestern Europe. The country is bordered by the Netherlands to the north, Germany to the east, Luxembourg to the southeast, France to th ...

. Their continental tours became increasingly ambitious in scope: in 1833 they visited

Strasbourg

Strasbourg (, , ; german: Straßburg ; gsw, label=Bas Rhin Alsatian, Strossburi , gsw, label=Haut Rhin Alsatian, Strossburig ) is the prefecture and largest city of the Grand Est region of eastern France and the official seat of the Eu ...

,

Schaffhausen

Schaffhausen (; gsw, Schafuuse; french: Schaffhouse; it, Sciaffusa; rm, Schaffusa; en, Shaffhouse) is a list of towns in Switzerland, town with historic roots, a municipalities of Switzerland, municipality in northern Switzerland, and the ...

,

Milan

Milan ( , , Lombard: ; it, Milano ) is a city in northern Italy, capital of Lombardy, and the second-most populous city proper in Italy after Rome. The city proper has a population of about 1.4 million, while its metropolitan city h ...

,

Genoa

Genoa ( ; it, Genova ; lij, Zêna ). is the capital of the Italian region of Liguria and the List of cities in Italy, sixth-largest city in Italy. In 2015, 594,733 people lived within the city's administrative limits. As of the 2011 Italian ce ...

and

Turin

Turin ( , Piedmontese language, Piedmontese: ; it, Torino ) is a city and an important business and cultural centre in Northern Italy. It is the capital city of Piedmont and of the Metropolitan City of Turin, and was the first Italian capital ...

, places to which Ruskin frequently returned. He developed a lifelong love of the

Alps

The Alps () ; german: Alpen ; it, Alpi ; rm, Alps ; sl, Alpe . are the highest and most extensive mountain range system that lies entirely in Europe, stretching approximately across seven Alpine countries (from west to east): France, Sw ...

, and in 1835 visited

Venice

Venice ( ; it, Venezia ; vec, Venesia or ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto Regions of Italy, region. It is built on a group of 118 small islands that are separated by canals and linked by over 400 ...

for the first time, that 'Paradise of cities' that provided the subject and symbolism of much of his later work.

These tours gave Ruskin the opportunity to observe and record his impressions of nature. He composed elegant, though mainly conventional poetry, some of which was published in ''Friendship's Offering''. His early notebooks and sketchbooks are full of visually sophisticated and technically accomplished drawings of maps, landscapes and buildings, remarkable for a boy of his age. He was profoundly affected by

Samuel Rogers

Samuel Rogers (30 July 1763 – 18 December 1855) was an English poet, during his lifetime one of the most celebrated, although his fame has long since been eclipsed by his Romantic colleagues and friends Wordsworth, Coleridge and Byron. ...

's poem ''Italy'' (1830), a copy of which was given to him as a 13th birthday present; in particular, he deeply admired the accompanying illustrations by

J. M. W. Turner. Much of Ruskin's own art in the 1830s was in imitation of Turner, and of

Samuel Prout

Samuel Prout painted by John Jackson in 1831

Market Day by Samuel Prout

A View in Nuremberg by Samuel Prout

Utrecht Town Hall by Samuel Prout in 1841

Samuel Prout (; 17 September 1783 – 10 February 1852) was a British watercolourist, and ...

, whose ''Sketches Made in Flanders and Germany'' (1833) he also admired. His artistic skills were refined under the tutelage of Charles Runciman,

Copley Fielding

Anthony Vandyke Copley Fielding (22 November 1787 – 3 March 1855), commonly called Copley Fielding, was an English painter born in Sowerby, near Halifax, and famous for his watercolour landscapes. At an early age Fielding became a pu ...

and

J. D. Harding.

First publications

Ruskin's journeys also provided inspiration for writing. His first publication was the poem "On Skiddaw and Derwent Water" (originally entitled "Lines written at the Lakes in Cumberland: Derwentwater" and published in the ''Spiritual Times'') (August 1829). In 1834, three short articles for

Loudon's ''Magazine of Natural History'' were published. They show early signs of his skill as a close "scientific" observer of nature, especially its geology.

From September 1837 to December 1838, Ruskin's ''The Poetry of Architecture'' was serialised in Loudon's ''Architectural Magazine'', under the pen name "Kata Phusin" (Greek for "According to Nature"). It was a study of cottages, villas, and other dwellings centred on a Wordsworthian argument that buildings should be sympathetic to their immediate environment and use local materials. It anticipated key themes in his later writings. In 1839, Ruskin's "Remarks on the Present State of Meteorological Science" was published in ''Transactions of the Meteorological Society''.

Oxford

In

Michaelmas

Michaelmas ( ; also known as the Feast of Saints Michael, Gabriel, and Raphael, the Feast of the Archangels, or the Feast of Saint Michael and All Angels) is a Christian festival observed in some Western liturgical calendars on 29 September, a ...

1836, Ruskin

matriculated

Matriculation is the formal process of entering a university, or of becoming eligible to enter by fulfilling certain academic requirements such as a matriculation examination.

Australia

In Australia, the term "matriculation" is seldom used now. ...

at the

University of Oxford

, mottoeng = The Lord is my light

, established =

, endowment = £6.1 billion (including colleges) (2019)

, budget = £2.145 billion (2019–20)

, chancellor ...

, taking up residence at

Christ Church in January of the following year. Enrolled as a

gentleman-commoner

A commoner is a student at certain universities in the British Isles who historically pays for his own tuition and commons, typically contrasted with scholars and exhibitioners, who were given financial emoluments towards their fees.

Cambridge

...

, he enjoyed equal status with his aristocratic peers. Ruskin was generally uninspired by Oxford and suffered bouts of illness. Perhaps the greatest advantage of his time there was in the few, close friendships he made. His tutor, the Rev Walter Lucas Brown, always encouraged him, as did a young senior tutor,

Henry Liddell (later the father of

Alice Liddell

Alice Pleasance Hargreaves (''née'' Liddell, ; 4 May 1852 – 16 November 1934), was an English woman who, in her childhood, was an acquaintance and photography subject of Lewis Carroll. One of the stories he told her during a boating trip beca ...

) and a private tutor, the Reverend

Osborne Gordon. He became close to the geologist and natural theologian

William Buckland

William Buckland DD, FRS (12 March 1784 – 14 August 1856) was an English theologian who became Dean of Westminster. He was also a geologist and palaeontologist.

Buckland wrote the first full account of a fossil dinosaur, which he named ' ...

. Among his fellow undergraduates, Ruskin's most important friends were

Charles Thomas Newton and

Henry Acland

Sir Henry Wentworth Dyke Acland, 1st Baronet, (23 August 181516 October 1900) was an English physician and educator.

Life

Henry Acland was born in Killerton, Exeter, the fourth son of Sir Thomas Acland and Lydia Elizabeth Hoare, and educate ...

.

His most noteworthy success came in 1839 when, at the third attempt, he won the prestigious

Newdigate Prize for poetry (

Arthur Hugh Clough came second). He met

William Wordsworth

William Wordsworth (7 April 177023 April 1850) was an English Romantic poet who, with Samuel Taylor Coleridge, helped to launch the Romantic Age in English literature with their joint publication '' Lyrical Ballads'' (1798).

Wordsworth's ' ...

, who was receiving an honorary degree, at the ceremony.

Ruskin's health was poor and he never became independent from his family during his time at Oxford. His mother took lodgings on High Street, where his father joined them at weekends. He was devastated to hear that his first love, Adèle Domecq, the second daughter of his father's business partner, had become engaged to a French nobleman. In April 1840, whilst revising for his examinations, he began to cough blood, which led to fears of consumption and a long break from Oxford travelling with his parents.

Before he returned to Oxford, Ruskin responded to a challenge that had been put to him by

Effie Gray

Euphemia Chalmers Millais, Lady Millais (''née'' Gray; 7 May 1828 – 23 December 1897) was a Scottish artists' model and the wife of Pre-Raphaelite painter John Everett Millais. She had previously been married to the art critic John Ruskin ...

, whom he later married: the twelve-year-old Effie had asked him to write a fairy story. During a six-week break at

Leamington Spa

Royal Leamington Spa, commonly known as Leamington Spa or simply Leamington (), is a spa town and civil parish in Warwickshire, England. Originally a small village called Leamington Priors, it grew into a spa town in the 18th century following ...

to undergo Dr Jephson's (1798–1878) celebrated salt-water cure, Ruskin wrote his only work of fiction, the fable ''

The King of the Golden River

''The King of the Golden River or The Black Brothers: A Legend of Stiria'' is a fantasy story originally written in 1841 by John Ruskin for the twelve-year-old Effie (Euphemia) Gray, whom Ruskin later married. It was published in book form in ...

'' (not published until December 1850 (but imprinted 1851), with illustrations by

Richard Doyle). A work of Christian sacrificial morality and charity, it is set in the Alpine landscape Ruskin loved and knew so well. It remains the most translated of all his works. Back at Oxford, in 1842 Ruskin sat for a pass degree, and was awarded an uncommon honorary double fourth-class degree in recognition of his achievements.

''Modern Painters I'' (1843)

For much of the period from late 1840 to autumn 1842, Ruskin was abroad with his parents, mainly in Italy. His studies of Italian art were chiefly guided by

George Richmond, to whom the Ruskins were introduced by

Joseph Severn

Joseph Severn (7 December 1793 – 3 August 1879) was an English portrait and subject painter and a personal friend of the famous English poet John Keats. He exhibited portraits, Italian genre, literary and biblical subjects, and a selec ...

, a friend of

Keats

John Keats (31 October 1795 – 23 February 1821) was an English poet of the second generation of Romantic poets, with Lord Byron and Percy Bysshe Shelley. His poems had been in publication for less than four years when he died of tuberculos ...

(whose son, Arthur Severn, later married Ruskin's cousin, Joan). He was galvanised into writing a defence of J. M. W. Turner when he read an attack on several of Turner's pictures exhibited at the

Royal Academy

The Royal Academy of Arts (RA) is an art institution based in Burlington House on Piccadilly in London. Founded in 1768, it has a unique position as an independent, privately funded institution led by eminent artists and architects. Its pur ...

. It recalled an attack by the critic Rev

John Eagles

John Eagles (1783–1855), was an English artist and author. His essays, mainly in art criticism, appeared in ''Blackwood's Magazine'' and were collected and published after his death. He also produced poetry and translations.

Biography

Eagles, ...

in ''

Blackwood's Magazine

''Blackwood's Magazine'' was a British magazine and miscellany printed between 1817 and 1980. It was founded by the publisher William Blackwood and was originally called the ''Edinburgh Monthly Magazine''. The first number appeared in April 1817 ...

'' in 1836, which had prompted Ruskin to write a long essay. John James had sent the piece to Turner, who did not wish it to be published. It finally appeared in 1903.

Before Ruskin began ''

Modern Painters

''Modern Painters'' (1843–1860) is a five-volume work by the Victorian art critic, John Ruskin, begun when he was 24 years old based on material collected in Switzerland in 1842. Ruskin argues that recent painters emerging from the tradition of ...

'', John James Ruskin had begun collecting watercolours, including works by

Samuel Prout

Samuel Prout painted by John Jackson in 1831

Market Day by Samuel Prout

A View in Nuremberg by Samuel Prout

Utrecht Town Hall by Samuel Prout in 1841

Samuel Prout (; 17 September 1783 – 10 February 1852) was a British watercolourist, and ...

and Turner. Both painters were among occasional guests of the Ruskins at Herne Hill, and 163

Denmark Hill

Denmark Hill is an area and road in Camberwell, in the London Borough of Southwark. It is a sub-section of the western flank of the Norwood Ridge, centred on the long, curved Ruskin Park slope of the ridge. The road is part of the A215 road, A21 ...

(demolished 1947) to which the family moved in 1842.

What became the first volume of ''

Modern Painters

''Modern Painters'' (1843–1860) is a five-volume work by the Victorian art critic, John Ruskin, begun when he was 24 years old based on material collected in Switzerland in 1842. Ruskin argues that recent painters emerging from the tradition of ...

'' (1843), published by

Smith, Elder & Co. under the anonymous authority of "A Graduate of Oxford", was Ruskin's answer to

Turner

Turner may refer to:

People and fictional characters

*Turner (surname), a common surname, including a list of people and fictional characters with the name

* Turner (given name), a list of people with the given name

*One who uses a lathe for turni ...

's critics. Ruskin controversially argued that modern landscape painters—and in particular Turner—were superior to the so-called "

" of the post-

Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass ideas ...

period. Ruskin maintained that, unlike Turner, Old Masters such as

Gaspard Dughet

Gaspard Dughet (15 June 1615 – 25 May 1675), also known as Gaspard Poussin, was a French painter born in Rome.

Life

Dughet was born in Rome, the son of a French pastry-cook

and his Italian wife. He has always generally been considered as a Fr ...

(Gaspar Poussin),

Claude, and

Salvator Rosa favoured pictorial convention, and not "truth to nature". He explained that he meant "moral as well as material truth". The job of the artist is to observe the reality of nature and not to invent it in a studioto render imaginatively on canvas what he has seen and understood, free of any rules of composition. For Ruskin, modern landscapists demonstrated superior understanding of the "truths" of water, air, clouds, stones, and vegetation, a profound appreciation of which Ruskin demonstrated in his own prose. He described works he had seen at the

National Gallery

The National Gallery is an art museum in Trafalgar Square in the City of Westminster, in Central London, England. Founded in 1824, it houses a collection of over 2,300 paintings dating from the mid-13th century to 1900. The current Director o ...

and

Dulwich Picture Gallery

Dulwich Picture Gallery is an art gallery in Dulwich, South London, which opened to the public in 1817. It was designed by Regency architect Sir John Soane using an innovative and influential method of illumination. Dulwich is the oldest pub ...

with extraordinary verbal felicity.

Although critics were slow to react and the reviews were mixed, many notable literary and artistic figures were impressed with the young man's work, including

Charlotte Brontë

Charlotte Brontë (, commonly ; 21 April 1816 – 31 March 1855) was an English novelist and poet, the eldest of the three Brontë sisters who survived into adulthood and whose novels became classics of English literature.

She enlisted i ...

and

Elizabeth Gaskell. Suddenly Ruskin had found his métier, and in one leap helped redefine the genre of art criticism, mixing a discourse of polemic with aesthetics, scientific observation and ethics. It cemented Ruskin's relationship with Turner. After the artist died in 1851, Ruskin catalogued nearly 20,000 sketches that Turner gave to the British nation.

1845 tour and ''Modern Painters II'' (1846)

Ruskin toured the continent with his parents again during 1844, visiting

Chamonix

Chamonix-Mont-Blanc ( frp, Chamôni), more commonly known as Chamonix, is a commune in the Haute-Savoie department in the Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes region of southeastern France. It was the site of the first Winter Olympics in 1924. In 2019, it had ...

and

Paris

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. S ...

, studying the geology of the Alps and the paintings of

Titian

Tiziano Vecelli or Vecellio (; 27 August 1576), known in English as Titian ( ), was an Italians, Italian (Republic of Venice, Venetian) painter of the Renaissance, considered the most important member of the 16th-century Venetian school (art), ...

,

Veronese and

Perugino

Pietro Perugino (, ; – 1523), born Pietro Vannucci, was an Italian Renaissance painter of the Umbrian school, who developed some of the qualities that found classic expression in the High Renaissance. Raphael was his most famous pupil.

Ear ...

among others at the

Louvre

The Louvre ( ), or the Louvre Museum ( ), is the world's most-visited museum, and an historic landmark in Paris, France. It is the home of some of the best-known works of art, including the ''Mona Lisa'' and the ''Venus de Milo''. A central l ...

. In 1845, at the age of 26, he undertook to travel without his parents for the first time. It provided him with an opportunity to study medieval art and architecture in France, Switzerland and especially Italy. In

Lucca

Lucca ( , ) is a city and ''comune'' in Tuscany, Central Italy, on the Serchio River, in a fertile plain near the Ligurian Sea. The city has a population of about 89,000, while its province has a population of 383,957.

Lucca is known as one o ...

he saw the Tomb of Ilaria del Carretto by

Jacopo della Quercia

Jacopo della Quercia (, ; 20 October 1438), also known as Jacopo di Pietro d'Agnolo di Guarnieri, was an Italian sculptor of the Renaissance, a contemporary of Brunelleschi, Ghiberti and Donatello. He is considered a precursor of Michelangelo ...

, which Ruskin considered the exemplar of Christian sculpture (he later associated it with the then object of his love,

Rose La Touche

Rose La Touche (1848–1875) was the pupil, cherished student, "pet", and ideal on whom the English art historian John Ruskin based ''Sesame and Lilies'' (1865).

Background

Rose was born to John "The Master" La Touche (1814-1904), (of the Hu ...

). He drew inspiration from what he saw at the

Campo Santo in

Pisa

Pisa ( , or ) is a city and ''comune'' in Tuscany, central Italy, straddling the Arno just before it empties into the Ligurian Sea. It is the capital city of the Province of Pisa. Although Pisa is known worldwide for its leaning tower, the cit ...

, and in

Florence

Florence ( ; it, Firenze ) is a city in Central Italy and the capital city of the Tuscany region. It is the most populated city in Tuscany, with 383,083 inhabitants in 2016, and over 1,520,000 in its metropolitan area.Bilancio demografico an ...

. In

Venice

Venice ( ; it, Venezia ; vec, Venesia or ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto Regions of Italy, region. It is built on a group of 118 small islands that are separated by canals and linked by over 400 ...

, he was particularly impressed by the works of

Fra Angelico

Fra Angelico (born Guido di Pietro; February 18, 1455) was an Italian painter of the Early Renaissance, described by Vasari in his '' Lives of the Artists'' as having "a rare and perfect talent".Giorgio Vasari, ''Lives of the Artists''. Pengu ...

and

Giotto

Giotto di Bondone (; – January 8, 1337), known mononymously as Giotto ( , ) and Latinised as Giottus, was an Italian painter and architect from Florence during the Late Middle Ages. He worked during the Gothic/Proto-Renaissance period. Giot ...

in

St Mark's Cathedral, and

Tintoretto

Tintoretto ( , , ; born Jacopo Robusti; late September or early October 1518Bernari and de Vecchi 1970, p. 83.31 May 1594) was an Italian painter identified with the Venetian school. His contemporaries both admired and criticized the speed with ...

in the

Scuola di San Rocco

The Scuola Grande di San Rocco is a building in Venice, northern Italy. It is noted for its collection of paintings by Tintoretto and generally agreed to include some of his finest work.

History

The building is the seat of a confraternity establ ...

, but he was alarmed by the combined effects of decay and modernisation on the city: "Venice is lost to me", he wrote. It finally convinced him that architectural restoration was destruction, and that the only true and faithful action was preservation and conservation.

Drawing on his travels, he wrote the second volume of ''Modern Painters'' (published April 1846). The volume concentrated on Renaissance and pre-Renaissance artists rather than on Turner. It was a more theoretical work than its predecessor. Ruskin explicitly linked the aesthetic and the divine, arguing that truth, beauty and religion are inextricably bound together: "the Beautiful as a gift of God". In defining categories of beauty and imagination, Ruskin argued that all great artists must perceive beauty and, with their imagination, communicate it creatively by means of symbolic representation. Generally, critics gave this second volume a warmer reception, although many found the attack on the aesthetic orthodoxy associated with

Joshua Reynolds

Sir Joshua Reynolds (16 July 1723 – 23 February 1792) was an English painter, specialising in portraits. John Russell said he was one of the major European painters of the 18th century. He promoted the "Grand Style" in painting which depend ...

difficult to accept. In the summer, Ruskin was abroad again with his father, who still hoped his son might become a poet, even

poet laureate

A poet laureate (plural: poets laureate) is a poet officially appointed by a government or conferring institution, typically expected to compose poems for special events and occasions. Albertino Mussato of Padua and Francesco Petrarca (Petrarch ...

, just one among many factors increasing the tension between them.

Middle life (1847–1869)

Marriage to Effie Gray

During 1847, Ruskin became closer to

Euphemia "Effie" Gray, the daughter of family friends. It was for her that Ruskin had written ''

The King of the Golden River

''The King of the Golden River or The Black Brothers: A Legend of Stiria'' is a fantasy story originally written in 1841 by John Ruskin for the twelve-year-old Effie (Euphemia) Gray, whom Ruskin later married. It was published in book form in ...

''. The couple were engaged in October. They married on 10 April 1848 at her home,

Bowerswell, in

Perth

Perth is the capital and largest city of the Australian state of Western Australia. It is the fourth most populous city in Australia and Oceania, with a population of 2.1 million (80% of the state) living in Greater Perth in 2020. Perth is ...

, once the residence of the Ruskin family. It was the site of the suicide of John Thomas Ruskin (Ruskin's grandfather). Owing to this association and other complications, Ruskin's parents did not attend. The European

Revolutions of 1848

The Revolutions of 1848, known in some countries as the Springtime of the Peoples or the Springtime of Nations, were a series of political upheavals throughout Europe starting in 1848. It remains the most widespread revolutionary wave in Europea ...

meant that the newlyweds' earliest travels together were restricted, but they were able to visit

Normandy

Normandy (; french: link=no, Normandie ; nrf, Normaundie, Nouormandie ; from Old French , plural of ''Normant'', originally from the word for "northman" in several Scandinavian languages) is a geographical and cultural region in Northwestern ...

, where Ruskin admired the

Gothic architecture

Gothic architecture (or pointed architecture) is an architectural style that was prevalent in Europe from the late 12th to the 16th century, during the High and Late Middle Ages, surviving into the 17th and 18th centuries in some areas. It e ...

.

Their early life together was spent at 31 Park Street,

Mayfair

Mayfair is an affluent area in the West End of London towards the eastern edge of Hyde Park, in the City of Westminster, between Oxford Street, Regent Street, Piccadilly and Park Lane. It is one of the most expensive districts in the world. ...

, secured for them by Ruskin's father (later addresses included nearby 6 Charles Street, and 30 Herne Hill). Effie was too unwell to undertake the European tour of 1849, so Ruskin visited the

Alps

The Alps () ; german: Alpen ; it, Alpi ; rm, Alps ; sl, Alpe . are the highest and most extensive mountain range system that lies entirely in Europe, stretching approximately across seven Alpine countries (from west to east): France, Sw ...

with his parents, gathering material for the third and fourth volumes of ''

Modern Painters

''Modern Painters'' (1843–1860) is a five-volume work by the Victorian art critic, John Ruskin, begun when he was 24 years old based on material collected in Switzerland in 1842. Ruskin argues that recent painters emerging from the tradition of ...

''. He was struck by the contrast between the Alpine beauty and the poverty of Alpine peasants, stirring his increasingly sensitive social conscience.

The marriage was unhappy, with Ruskin reportedly being cruel to Effie and distrustful of her. The marriage was never

consummated and was annulled six years later in 1854.

Architecture

Ruskin's developing interest in architecture, and particularly in the

Gothic

Gothic or Gothics may refer to:

People and languages

*Goths or Gothic people, the ethnonym of a group of East Germanic tribes

**Gothic language, an extinct East Germanic language spoken by the Goths

**Crimean Gothic, the Gothic language spoken b ...

, led to the first work to bear his name, ''

The Seven Lamps of Architecture

''The Seven Lamps of Architecture'' is an extended essay, first published in May 1849 and written by the English art critic and theorist John Ruskin. The 'lamps' of the title are Ruskin's principles of architecture, which he later enlarged upon i ...

'' (1849). It contained 14 plates etched by the author. The title refers to seven moral categories that Ruskin considered vital to and inseparable from all architecture: sacrifice, truth, power, beauty, life, memory and obedience. All would provide recurring themes in his future work. ''Seven Lamps'' promoted the virtues of a secular and Protestant form of Gothic. It was a challenge to the Catholic influence of architect

A. W. N. Pugin.

''The Stones of Venice''

In November 1849, John and Effie Ruskin visited

Venice

Venice ( ; it, Venezia ; vec, Venesia or ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto Regions of Italy, region. It is built on a group of 118 small islands that are separated by canals and linked by over 400 ...

, staying at the Hotel Danieli. Their different personalities are revealed by their contrasting priorities. For Effie, Venice provided an opportunity to socialise, while Ruskin was engaged in solitary studies. In particular, he made a point of drawing the

Ca' d'Oro

The Ca' d'Oro or Palazzo Santa Sofia is a palace on the Grand Canal in Venice, northern Italy. One of the older palaces in the city, its name means "golden house" due to the gilt and polychrome external decorations which once adorned its walls. ...

and the

Doge's Palace, or Palazzo Ducale, because he feared that they would be destroyed by the occupying Austrian troops. One of these troops, Lieutenant Charles Paulizza, became friendly with Effie, apparently with Ruskin's consent. Her brother, among others, later claimed that Ruskin was deliberately encouraging the friendship to compromise her, as an excuse to separate.

Meanwhile, Ruskin was making the extensive sketches and notes that he used for his three-volume work

''The Stones of Venice'' (1851–53). Developing from a technical history of Venetian architecture from the Romanesque to the Renaissance, into a broad cultural history, ''Stones'' represented Ruskin's opinion of contemporary England. It served as a warning about the moral and spiritual health of society. Ruskin argued that Venice had degenerated slowly. Its cultural achievements had been compromised, and its society corrupted, by the decline of true Christian faith. Instead of revering the divine, Renaissance artists honoured themselves, arrogantly celebrating human sensuousness.

The chapter, "The Nature of Gothic" appeared in the second volume of ''Stones''. Praising Gothic ornament, Ruskin argued that it was an expression of the artisan's joy in free, creative work. The worker must be allowed to think and to express his own personality and ideas, ideally using his own hands, rather than machinery.

This was both an aesthetic attack on, and a social critique of, the

division of labour in particular, and

industrial capitalism

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their operation for profit. Central characteristics of capitalism include capital accumulation, competitive markets, price system, private ...

in general. This chapter had a profound effect, and was reprinted both by the

Christian socialist

Christian socialism is a religious and political philosophy that blends Christianity and socialism, endorsing left-wing politics and socialist economics on the basis of the Bible and the teachings of Jesus. Many Christian socialists believe cap ...

founders of the

Working Men's College and later by the

Arts and Crafts

A handicraft, sometimes more precisely expressed as artisanal handicraft or handmade, is any of a wide variety of types of work where useful and decorative objects are made completely by one’s hand or by using only simple, non-automated re ...

pioneer and socialist

William Morris

William Morris (24 March 1834 – 3 October 1896) was a British textile designer, poet, artist, novelist, architectural conservationist, printer, translator and socialist activist associated with the British Arts and Crafts Movement. He ...

.

Pre-Raphaelites

John Everett Millais

Sir John Everett Millais, 1st Baronet, ( , ; 8 June 1829 – 13 August 1896) was an English painter and illustrator who was one of the founders of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. He was a child prodigy who, aged eleven, became the youngest ...

,

William Holman Hunt

William Holman Hunt (2 April 1827 – 7 September 1910) was an English painter and one of the founders of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. His paintings were notable for their great attention to detail, vivid colour, and elaborate symbolis ...

and

Dante Gabriel Rossetti

Gabriel Charles Dante Rossetti (12 May 1828 – 9 April 1882), generally known as Dante Gabriel Rossetti (), was an English poet, illustrator, painter, translator and member of the Rossetti family. He founded the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhoo ...

had established the

Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood

The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (later known as the Pre-Raphaelites) was a group of English painters, poets, and art critics, founded in 1848 by William Holman Hunt, John Everett Millais, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, William Michael Rossetti, James ...

in 1848. The Pre-Raphaelite commitment to 'naturalism' – "paint

ngfrom nature only", depicting nature in fine detail, had been influenced by Ruskin.

Ruskin became acquainted with Millais after the artists made an approach to Ruskin through their mutual friend

Coventry Patmore

Coventry Kersey Dighton Patmore (23 July 1823 – 26 November 1896) was an English poet and literary critic. He is best known for his book of poetry '' The Angel in the House'', a narrative poem about the Victorian ideal of a happy marriage.

...

. Initially, Ruskin had not been impressed by Millais's ''

Christ in the House of His Parents

''Christ in the House of His Parents'' (1849–50) is a painting by John Everett Millais depicting the Holy Family in Saint Joseph's carpentry workshop. The painting was extremely controversial when first exhibited, prompting many negative rev ...

'' (1849–50), a painting that was considered blasphemous at the time, but Ruskin wrote letters defending the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood to ''

The Times

''The Times'' is a British daily national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its current name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its sister paper ''The Sunday Times'' (fou ...

'' during May 1851. Providing Millais with artistic patronage and encouragement, in the summer of 1853 the artist (and his brother) travelled to Scotland with Ruskin and Effie where, at

Glenfinlas, he painted the closely observed landscape background of

gneiss

Gneiss ( ) is a common and widely distributed type of metamorphic rock. It is formed by high-temperature and high-pressure metamorphic processes acting on formations composed of igneous or sedimentary rocks. Gneiss forms at higher temperatures an ...

rock to which, as had always been intended, he later added

Ruskin's portrait.

Millais had painted a picture of Effie for ''

The Order of Release, 1746

''The Order of Release, 1746'' is a painting by John Everett Millais exhibited in 1853. It is notable for marking the beginnings of Millais's move away from the highly medievalist Pre-Raphaelitism of his early years. Effie Gray, who later left he ...

'', exhibited at the

Royal Academy

The Royal Academy of Arts (RA) is an art institution based in Burlington House on Piccadilly in London. Founded in 1768, it has a unique position as an independent, privately funded institution led by eminent artists and architects. Its pur ...

in 1852. Suffering increasingly from physical illness and acute mental anxiety, Effie was arguing fiercely with her husband and his intense and overly protective parents, and sought solace with her own parents in Scotland. The Ruskin marriage was already undermined as she and Millais fell in love, and Effie left Ruskin, causing a public scandal.

During April 1854, Effie filed her

suit of nullity, on grounds of "non-consummation" owing to his "incurable

impotency

Erectile dysfunction (ED), also called impotence, is the type of sexual dysfunction in which the penis fails to become or stay erect during sexual activity. It is the most common sexual problem in men.Cunningham GR, Rosen RC. Overview of male ...

", a charge Ruskin later disputed. Ruskin wrote, "I can prove my virility at once." The annulment was granted in July. Ruskin did not even mention it in his diary. Effie married Millais the following year. The complex reasons for the non-consummation and ultimate failure of the Ruskin marriage are a matter of enduring speculation and debate.

Ruskin continued to support

Hunt

Hunting is the human practice of seeking, pursuing, capturing, or killing wildlife or feral animals. The most common reasons for humans to hunt are to harvest food (i.e. meat) and useful animal products (fur/ hide, bone/tusks, horn/antler, e ...

and

Rossetti

The House of Rossetti is an Italian noble, and Boyar Princely family appearing in the 14th-15th century, originating among the patrician families, during the Republic of Genoa, with branches of the family establishing themselves in the Kingdom o ...

. He also provided an annuity of £150 in 1855–57 to

Elizabeth Siddal

Elizabeth Eleanor Siddall (25 July 1829 – 11 February 1862), better known as Elizabeth Siddal, was an English artist, poet, and artists' model. Significant collections of her artworks can be found at Wightwick Manor and the Ashmolean. Sidd ...

, Rossetti's wife, to encourage her art (and paid for the services of

Henry Acland

Sir Henry Wentworth Dyke Acland, 1st Baronet, (23 August 181516 October 1900) was an English physician and educator.

Life

Henry Acland was born in Killerton, Exeter, the fourth son of Sir Thomas Acland and Lydia Elizabeth Hoare, and educate ...

for her medical care).

[''ODNB'': "Critic of Contemporary Art".] Other artists influenced by the Pre-Raphaelites also received both critical and financial assistance from Ruskin, including

John Brett,

John William Inchbold

John William Inchbold (29 August 1830 – 23 January 1888) was an English painter who was born in Leeds, Yorkshire. His style was influenced by the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. He was the son of a Yorkshire newspaper owner, Thomas Inchbold.

Bi ...

, and

Edward Burne-Jones

Sir Edward Coley Burne-Jones, 1st Baronet, (; 28 August, 183317 June, 1898) was a British painter and designer associated with the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood which included Dante Gabriel Rossetti, John Millais, Ford Madox Brown and Holman Hun ...

, who became a good friend (he called him "Brother Ned"). His father's disapproval of such friends was a further cause of tension between them.

During this period Ruskin wrote regular reviews of the annual exhibitions at the

Royal Academy

The Royal Academy of Arts (RA) is an art institution based in Burlington House on Piccadilly in London. Founded in 1768, it has a unique position as an independent, privately funded institution led by eminent artists and architects. Its pur ...

with the title ''Academy Notes'' (1855–59, 1875). They were highly influential, capable of making or breaking reputations. The satirical magazine ''

Punch

Punch commonly refers to:

* Punch (combat), a strike made using the hand closed into a fist

* Punch (drink), a wide assortment of drinks, non-alcoholic or alcoholic, generally containing fruit or fruit juice

Punch may also refer to:

Places

* Pun ...

'' published the lines (24 May 1856), "I paints and paints,/hears no complaints/And sells before I'm dry,/Till savage Ruskin/He sticks his tusk in/Then nobody will buy."

Ruskin was an art-philanthropist: in March 1861 he gave 48

Turner

Turner may refer to:

People and fictional characters

*Turner (surname), a common surname, including a list of people and fictional characters with the name

* Turner (given name), a list of people with the given name

*One who uses a lathe for turni ...

drawings to the

Ashmolean

The Ashmolean Museum of Art and Archaeology () on Beaumont Street, Oxford, England, is Britain's first public museum. Its first building was erected in 1678–1683 to house the cabinet of curiosities that Elias Ashmole gave to the University o ...

in

Oxford

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the ...

, and a further 25 to the

Fitzwilliam Museum

The Fitzwilliam Museum is the art and antiquities museum of the University of Cambridge. It is located on Trumpington Street opposite Fitzwilliam Street in central Cambridge. It was founded in 1816 under the will of Richard FitzWilliam, 7th Vis ...

,

Cambridge

Cambridge ( ) is a university city and the county town in Cambridgeshire, England. It is located on the River Cam approximately north of London. As of the 2021 United Kingdom census, the population of Cambridge was 145,700. Cambridge bec ...

in May. Ruskin's own work was very distinctive, and he occasionally exhibited his watercolours: in the United States in 1857–58 and 1879, for example; and in England, at the Fine Art Society in 1878, and at the Royal Society of Painters in Watercolour (of which he was an honorary member) in 1879. He created many careful studies of natural forms, based on his detailed botanical, geological and architectural observations. Examples of his work include a painted, floral pilaster decoration in the central room of

Wallington Hall

Wallington is a country house and gardens located about west of Morpeth, Northumberland, England, near the village of Cambo. It has been owned by the National Trust since 1942, after it was donated complete with the estate and farms by Sir Ch ...

in Northumberland, home of his friend

Pauline Trevelyan

Pauline, Lady Trevelyan (''née'' Paulina Jermyn; Trevelyan, Raleigh (1978); ''A Pre-Raphaelite Circle'', p.7; Chatto & Windus, London; 1st edition. 25 January 1816, Hawkedon, Suffolk13 May 1866, Neuchâtel, Switzerland) was an English painter ...

. The

stained glass window

Stained glass is coloured glass as a material or works created from it. Throughout its thousand-year history, the term has been applied almost exclusively to the windows of churches and other significant religious buildings. Although tradition ...

in the ''Little Church of St Francis'' Funtley,

Fareham, Hampshire

Fareham ( ) is a market town at the north-west tip of Portsmouth Harbour, between the cities of Portsmouth and Southampton in south east Hampshire, England. It gives its name to the Borough of Fareham. It was historically an important manufact ...

is reputed to have been designed by him. Originally placed in the ''St. Peter's Church'' Duntisbourne Abbots near

Cirencester

Cirencester (, ; see below for more variations) is a market town in Gloucestershire, England, west of London. Cirencester lies on the River Churn, a tributary of the River Thames, and is the largest town in the Cotswolds. It is the home of ...

, the window depicts the Ascension and the Nativity.

Ruskin's theories also inspired some architects to adapt the

Gothic style

Gothic or Gothics may refer to:

People and languages

*Goths or Gothic people, the ethnonym of a group of East Germanic tribes

**Gothic language, an extinct East Germanic language spoken by the Goths

**Crimean Gothic, the Gothic language spoken b ...

. Such buildings created what has been called a distinctive "Ruskinian Gothic". Through his friendship with

Henry Acland

Sir Henry Wentworth Dyke Acland, 1st Baronet, (23 August 181516 October 1900) was an English physician and educator.

Life

Henry Acland was born in Killerton, Exeter, the fourth son of Sir Thomas Acland and Lydia Elizabeth Hoare, and educate ...

, Ruskin supported attempts to establish what became the

Oxford University Museum of Natural History

The Oxford University Museum of Natural History, sometimes known simply as the Oxford University Museum or OUMNH, is a museum displaying many of the University of Oxford's natural history specimens, located on Parks Road in Oxford, England. It a ...

(designed by

Benjamin Woodward

Benjamin Woodward (16 November 1816 – 15 May 1861) was an Irish architect who, in partnership with Sir Thomas Newenham Deane, designed a number of buildings in Dublin, Cork and Oxford.

Life

Woodward was born in Tullamore, County Offaly, Ire ...

) - which is the closest thing to a model of this style, but still failed to satisfy Ruskin completely. The many twists and turns in the Museum's development, not least its increasing cost, and the University authorities' less than enthusiastic attitude towards it, proved increasingly frustrating for Ruskin.

Ruskin and education

The

Museum

A museum ( ; plural museums or, rarely, musea) is a building or institution that cares for and displays a collection of artifacts and other objects of artistic, cultural, historical, or scientific importance. Many public museums make these ...

was part of a wider plan to improve science provision at Oxford, something the University initially resisted. Ruskin's first formal teaching role came about in the mid-1850s, when he taught drawing classes (assisted by

Dante Gabriel Rossetti

Gabriel Charles Dante Rossetti (12 May 1828 – 9 April 1882), generally known as Dante Gabriel Rossetti (), was an English poet, illustrator, painter, translator and member of the Rossetti family. He founded the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhoo ...

) at the

Working Men's College, established by the

Christian socialists,

Frederick James Furnivall

Frederick James Furnivall (4 February 1825 – 2 July 1910) was an English philologist, best known as one of the co-creators of the '' New English Dictionary''. He founded a number of learned societies on early English literature and made pio ...

and

Frederick Denison Maurice

John Frederick Denison Maurice (29 August 1805 – 1 April 1872), known as F. D. Maurice, was an English Anglican theologian, a prolific author, and one of the founders of Christian socialism. Since World War II, interest in Maurice has exp ...

. Although Ruskin did not share the founders' politics, he strongly supported the idea that through education workers could achieve a crucially important sense of (self-)fulfilment. One result of this involvement was Ruskin's ''Elements of Drawing'' (1857). He had taught several women drawing, by means of correspondence, and his book represented both a response and a challenge to contemporary drawing manuals. The WMC was also a useful recruiting ground for assistants, on some of whom Ruskin would later come to rely, such as his future publisher,

George Allen George Allen may refer to:

Politics and law

* George E. Allen (1896–1973), American political operative and one-time head coach of the Cumberland University football team

* George Allen (Australian politician) (1800–1877), Mayor of Sydney and ...

.

From 1859 until 1868, Ruskin was involved with the progressive school for girls at

Winnington Hall

Winnington Hall is a former country house in Winnington, now a suburb of Northwich, Cheshire, England. It is recorded in the National Heritage List for England as a designated Grade I listed building. The building is in effect two house ...

in Cheshire. A frequent visitor, letter-writer, and donor of pictures and geological specimens to the school, Ruskin approved of the mixture of sports, handicrafts, music and dancing encouraged by its principal, Miss Bell. The association led to Ruskin's sub-Socratic work, ''The Ethics of the Dust'' (1866), an imagined conversation with Winnington's girls in which he cast himself as the "Old Lecturer". On the surface a discourse on crystallography, it is a metaphorical exploration of social and political ideals. In the 1880s, Ruskin became involved with another educational institution,

Whitelands College

Whitelands College is the oldest of the four constituent colleges of the University of Roehampton.

History

Whitelands College is one of the oldest higher education institutions in England (predating every university except Oxford, Cambridge, Lo ...

, a training college for teachers, where he instituted a

May Queen

In the British Isles and parts of the Commonwealth, the May Queen or Queen of May is a personification of the May Day holiday, and of springtime and also summer. The May Queen is a girl who rides or walks at the front of a parade for May Da ...

festival that endures today. (It was also replicated in the 19th century at the

Cork

Cork or CORK may refer to:

Materials

* Cork (material), an impermeable buoyant plant product

** Cork (plug), a cylindrical or conical object used to seal a container

***Wine cork

Places Ireland

* Cork (city)

** Metropolitan Cork, also known as G ...

High School for Girls.) Ruskin also bestowed books and gemstones upon

Somerville College

Somerville College, a constituent college of the University of Oxford in England, was founded in 1879 as Somerville Hall, one of its first two women's colleges. Among its alumnae have been Margaret Thatcher, Indira Gandhi, Dorothy Hodgkin, ...

, one of

Oxford

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the ...

's first two

women's college

Women's colleges in higher education are undergraduate, bachelor's degree-granting institutions, often liberal arts colleges, whose student populations are composed exclusively or almost exclusively of women. Some women's colleges admit male stud ...

s, which he visited regularly, and was similarly generous to other educational institutions for women.

''Modern Painters III'' and ''IV''

Both volumes III and IV of ''

Modern Painters

''Modern Painters'' (1843–1860) is a five-volume work by the Victorian art critic, John Ruskin, begun when he was 24 years old based on material collected in Switzerland in 1842. Ruskin argues that recent painters emerging from the tradition of ...

'' were published in 1856. In ''MP'' III Ruskin argued that all great art is "the expression of the spirits of great men". Only the morally and spiritually healthy are capable of admiring the noble and the beautiful, and transforming them into great art by imaginatively penetrating their essence. ''MP'' IV presents the geology of the Alps in terms of landscape painting, and their moral and spiritual influence on those living nearby. The contrasting final chapters, "The Mountain Glory" and "The Mountain Gloom" provide an early example of Ruskin's social analysis, highlighting the poverty of the peasants living in the lower Alps.

Public lecturer

In addition to leading more formal teaching classes, from the 1850s Ruskin became an increasingly popular public lecturer. His first public lectures were given in Edinburgh, in November 1853, on architecture and painting. His lectures at the

Art Treasures Exhibition

The Art Treasures of Great Britain was an exhibition of fine art held in Manchester, England, from 5 May to 17 October 1857.[Keats

John Keats (31 October 1795 – 23 February 1821) was an English poet of the second generation of Romantic poets, with Lord Byron and Percy Bysshe Shelley. His poems had been in publication for less than four years when he died of tuberculos ...]

's phrase, ''A Joy For Ever''. In these lectures, Ruskin spoke about how to acquire art, and how to use it, arguing that England had forgotten that true wealth is virtue, and that art is an index of a nation's well-being. Individuals have a responsibility to consume wisely, stimulating beneficent demand. The increasingly critical tone and political nature of Ruskin's interventions outraged his father and the

"Manchester School" of economists, as represented by a hostile review in the ''

Manchester Examiner and Times

The ''Manchester Examiner'' was a newspaper based in Manchester, England, that was founded around 1845–1846. Initially intended as an organ to promote the idea of Manchester Liberalism, a decline in its later years led to a takeover by a group w ...

''. As the Ruskin scholar Helen Gill Viljoen noted, Ruskin was increasingly critical of his father, especially in letters written by Ruskin directly to him, many of them still unpublished.

Ruskin gave the inaugural address at the Cambridge School of Art in 1858, an institution from which the modern-day

Anglia Ruskin University

Anglia Ruskin University (ARU) is a public university in East Anglia, United Kingdom. Its origins are in the Cambridge School of Art, founded by William John Beamont in 1858. It became a university in 1992, and was renamed after John Ruskin in ...

has grown. In ''The Two Paths'' (1859), five lectures given in London,

Manchester

Manchester () is a city in Greater Manchester, England. It had a population of 552,000 in 2021. It is bordered by the Cheshire Plain to the south, the Pennines to the north and east, and the neighbouring city of Salford to the west. The t ...

,

Bradford

Bradford is a city and the administrative centre of the City of Bradford district in West Yorkshire, England. The city is in the Pennines' eastern foothills on the banks of the Bradford Beck. Bradford had a population of 349,561 at the 2011 ...

and

Tunbridge Wells

Royal Tunbridge Wells is a town in Kent, England, southeast of central London. It lies close to the border with East Sussex on the northern edge of the Weald, High Weald, whose sandstone geology is exemplified by the rock formation High Roc ...

, Ruskin argued that a 'vital law' underpins art and architecture, drawing on the

labour theory of value

The labor theory of value (LTV) is a theory of value that argues that the economic value of a good or service is determined by the total amount of " socially necessary labor" required to produce it.

The LTV is usually associated with Marxian ...

. (For other addresses and letters, Cook and Wedderburn, vol. 16, pp. 427–87.) The year 1859 also marked his last tour of Europe with his ageing parents, during which they visited

Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

and

Switzerland

). Swiss law does not designate a ''capital'' as such, but the federal parliament and government are installed in Bern, while other federal institutions, such as the federal courts, are in other cities (Bellinzona, Lausanne, Luzern, Neuchâtel ...

.

Turner Bequest

Ruskin had been in Venice when he heard about

Turner's death in 1851. Being named an executor to Turner's will was an honour that Ruskin respectfully declined, but later took up. Ruskin's book in celebration of the sea, ''The Harbours of England'', revolving around Turner's drawings, was published in 1856. In January 1857, Ruskin's ''Notes on the Turner Gallery at

Marlborough House

Marlborough House, a Grade I listed mansion in St James's, City of Westminster, London, is the headquarters of the Commonwealth of Nations and the seat of the Commonwealth Secretariat. It was built in 1711 for Sarah Churchill, Duchess of Marl ...

, 1856'' was published. He persuaded the

National Gallery

The National Gallery is an art museum in Trafalgar Square in the City of Westminster, in Central London, England. Founded in 1824, it houses a collection of over 2,300 paintings dating from the mid-13th century to 1900. The current Director o ...

to allow him to work on the Turner Bequest of nearly 20,000 individual artworks left to the nation by the artist. This involved Ruskin in an enormous amount of work, completed in May 1858, and involved cataloguing, framing and conserving. Four hundred watercolours were displayed in cabinets of Ruskin's own design.

Recent scholarship has argued that Ruskin did not, as previously thought, collude in the destruction of Turner's erotic drawings, but his work on the Bequest did modify his attitude towards Turner. (See below,

Controversies: Turner's Erotic Drawings.)

Religious "unconversion"

In 1858, Ruskin was again travelling in Europe. The tour took him from

Switzerland

). Swiss law does not designate a ''capital'' as such, but the federal parliament and government are installed in Bern, while other federal institutions, such as the federal courts, are in other cities (Bellinzona, Lausanne, Luzern, Neuchâtel ...

to

Turin

Turin ( , Piedmontese language, Piedmontese: ; it, Torino ) is a city and an important business and cultural centre in Northern Italy. It is the capital city of Piedmont and of the Metropolitan City of Turin, and was the first Italian capital ...

, where he saw

Paolo Veronese

Paolo Caliari (152819 April 1588), known as Paolo Veronese ( , also , ), was an Italian Renaissance painter based in Venice, known for extremely large history paintings of religion and mythology, such as ''The Wedding at Cana'' (1563) and ''The ...

's ''Presentation of the

Queen of Sheba

The Queen of Sheba ( he, מַלְכַּת שְׁבָא, Malkaṯ Šəḇāʾ; ar, ملكة سبأ, Malikat Sabaʾ; gez, ንግሥተ ሳባ, Nəgśətä Saba) is a figure first mentioned in the Hebrew Bible. In the original story, she bring ...

''. He would later claim (in April 1877) that the discovery of this painting, contrasting starkly with a particularly dull sermon, led to his "unconversion" from

Evangelical Christianity

Evangelicalism (), also called evangelical Christianity or evangelical Protestantism, is a worldwide Interdenominationalism, interdenominational movement within Protestantism, Protestant Christianity that affirms the centrality of being "bor ...

. He had, however, doubted his Evangelical Christian faith for some time, shaken by Biblical and geological scholarship that was claimed to have undermined the literal truth and absolute authority of the Bible: "those dreadful hammers!" he wrote to

Henry Acland

Sir Henry Wentworth Dyke Acland, 1st Baronet, (23 August 181516 October 1900) was an English physician and educator.

Life

Henry Acland was born in Killerton, Exeter, the fourth son of Sir Thomas Acland and Lydia Elizabeth Hoare, and educate ...

, "I hear the chink of them at the end of every cadence of the Bible verses." This "loss of faith" precipitated a considerable personal crisis. His confidence undermined, he believed that much of his writing to date had been founded on a bed of lies and half-truths. He later returned to Christianity.

Social critic and reformer: ''Unto This Last''

Although in 1877 Ruskin said that in 1860, "I gave up my art work and wrote ''

Unto This Last ''Unto This Last'' is an essay critical of economics by John Ruskin, first published between August and December 1860 in the monthly journal ''Cornhill Magazine'' in four articles.

Title

The title is a quotation from the Parable of the Workers i ...

''... the central work of my life" the break was not so dramatic or final. Following his crisis of faith, and urged to political and economic work by his professed "master"

Thomas Carlyle

Thomas Carlyle (4 December 17955 February 1881) was a Scottish essayist, historian and philosopher. A leading writer of the Victorian era, he exerted a profound influence on 19th-century art, literature and philosophy.

Born in Ecclefechan, Dum ...