John P. Kennedy on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

John Pendleton Kennedy (October 25, 1795 – August 18, 1870) was an American novelist, lawyer and Whig politician who served as

Kennedy's college studies were interrupted by the War of 1812. He joined the army and in 1814, marched with the United Company of the 5th Baltimore Light Dragoons, known as the "Baltimore 5th," a unit that included rich merchants, lawyers, and other professionals. Kennedy wrote humorous amounts of his military escapades, such as when he lost his boots and marched onward in dancing pumps. The war was, however, serious, and Kennedy participated in the disastrous Battle of Bladensburg as the British threatened the new national capitol, Washington, D.C. Secretary of State

Kennedy's college studies were interrupted by the War of 1812. He joined the army and in 1814, marched with the United Company of the 5th Baltimore Light Dragoons, known as the "Baltimore 5th," a unit that included rich merchants, lawyers, and other professionals. Kennedy wrote humorous amounts of his military escapades, such as when he lost his boots and marched onward in dancing pumps. The war was, however, serious, and Kennedy participated in the disastrous Battle of Bladensburg as the British threatened the new national capitol, Washington, D.C. Secretary of State

Kennedy's friends and personal associates included

Kennedy's friends and personal associates included

Kennedy was proposed as a vice-presidential running mate to

Kennedy was proposed as a vice-presidential running mate to

Kennedy's opposition to slavery was first publicly expressed in his writings, and then later in his life as a politician, through his speeches and political initiatives. His opposition to slavery in Maryland can be traced back through many decades of his life, but the depth of that opposition went through an evolution from milder and more understated in the beginning, to being stronger, more vocal and more morally based by the time of the

Kennedy's opposition to slavery was first publicly expressed in his writings, and then later in his life as a politician, through his speeches and political initiatives. His opposition to slavery in Maryland can be traced back through many decades of his life, but the depth of that opposition went through an evolution from milder and more understated in the beginning, to being stronger, more vocal and more morally based by the time of the

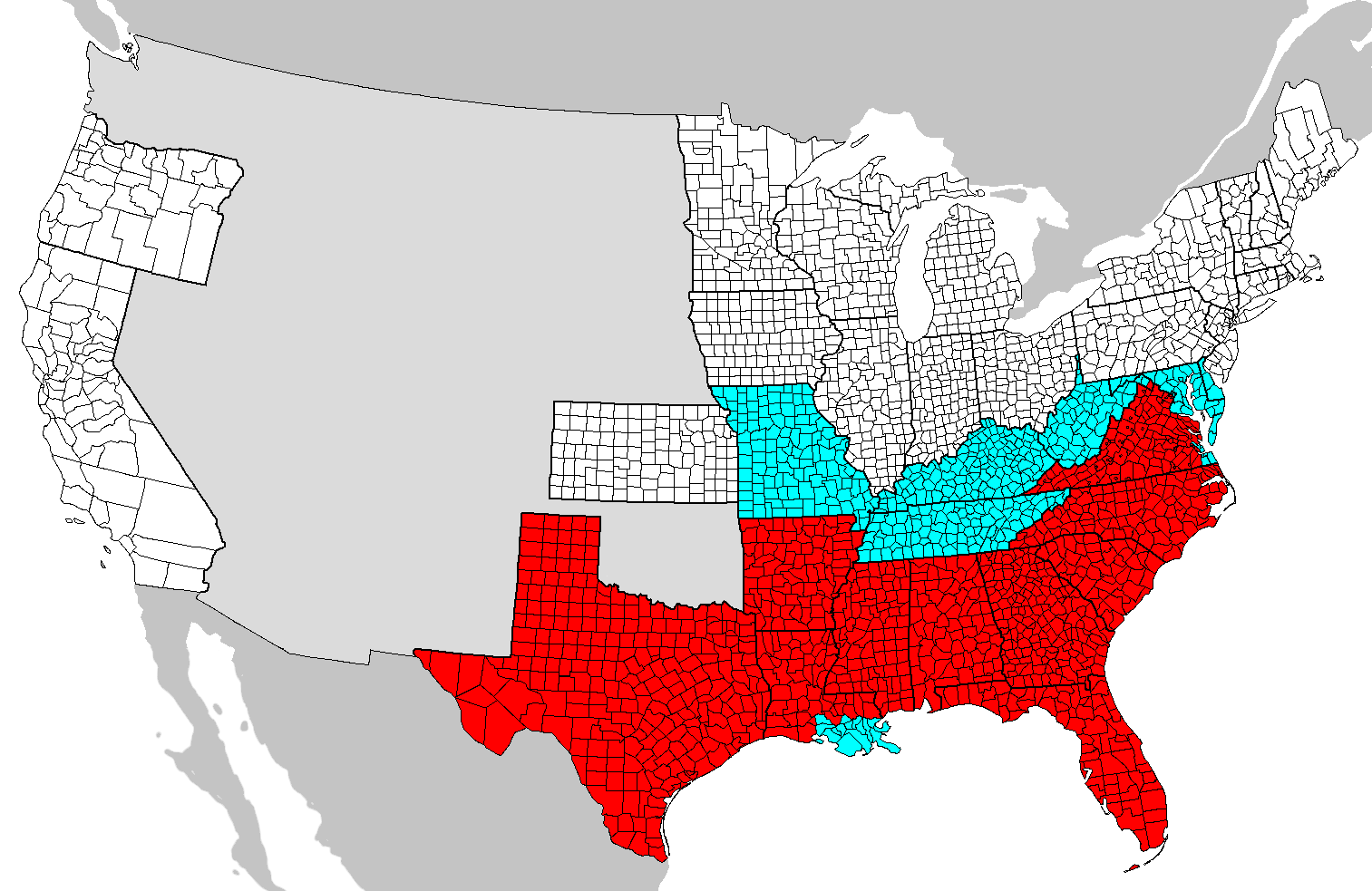

Because Maryland was not in the Confederacy, the Emancipation Proclamation did not apply to the state and slavery continued there.Miranda S. Spivack, September 13, 2013, "The not-quite-Free State: Maryland dragged its feet on emancipation during Civil War: Special Report, Civil War 150", CHAPTER 7, The Washington Post, https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/md-politics/the-not-quite-free-state-maryland-dragged-its-feet-on-emancipation-during-civil-war/2013/09/13/a34d35de-fec7-11e2-bd97-676ec24f1f3f_story.html Since there was no active insurrection in Maryland, President Lincoln did not feel constitutionally authorized to extend the Emancipation Proclamation to Maryland. Only the state itself could end slavery at this point, and this was not a certain outcome as Maryland was a

Because Maryland was not in the Confederacy, the Emancipation Proclamation did not apply to the state and slavery continued there.Miranda S. Spivack, September 13, 2013, "The not-quite-Free State: Maryland dragged its feet on emancipation during Civil War: Special Report, Civil War 150", CHAPTER 7, The Washington Post, https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/md-politics/the-not-quite-free-state-maryland-dragged-its-feet-on-emancipation-during-civil-war/2013/09/13/a34d35de-fec7-11e2-bd97-676ec24f1f3f_story.html Since there was no active insurrection in Maryland, President Lincoln did not feel constitutionally authorized to extend the Emancipation Proclamation to Maryland. Only the state itself could end slavery at this point, and this was not a certain outcome as Maryland was a

Biography at the Naval Historical Center

John Kennedy

at

Swallow Barn, vol. 1

, - , - , - , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Kennedy, John P. 1795 births 1870 deaths 19th-century American novelists African-American history of Maryland American male novelists 19th-century American memoirists American military personnel of the War of 1812 American people of Irish descent Burials at Green Mount Cemetery Fillmore administration cabinet members History of Baltimore History of slavery in Maryland Johns Hopkins University Maryland lawyers Politicians from Baltimore Speakers of the Maryland House of Delegates St. Mary's City, Maryland St. Mary's College of Maryland St. Mary's County, Maryland United States Secretaries of the Navy Whig Party members of the United States House of Representatives from Maryland 19th-century American politicians Writers from Baltimore American abolitionists Novelists from Maryland American male non-fiction writers

United States Secretary of the Navy

The secretary of the Navy (or SECNAV) is a statutory officer () and the head (chief executive officer) of the Department of the Navy, a military department (component organization) within the United States Department of Defense.

By law, the se ...

from July 26, 1852, to March 4, 1853, during the administration of President Millard Fillmore

Millard Fillmore (January 7, 1800March 8, 1874) was the 13th president of the United States, serving from 1850 to 1853; he was the last to be a member of the Whig Party while in the White House. A former member of the U.S. House of Represen ...

, and as a U.S. Representative from Maryland's 4th congressional district, during which he encouraged the United States government's study, adoption and implementation of the telegraph

Telegraphy is the long-distance transmission of messages where the sender uses symbolic codes, known to the recipient, rather than a physical exchange of an object bearing the message. Thus flag semaphore is a method of telegraphy, whereas ...

. A lawyer who became a lobbyist for and director of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad

The Baltimore and Ohio Railroad was the first common carrier railroad and the oldest railroad in the United States, with its first section opening in 1830. Merchants from Baltimore, which had benefited to some extent from the construction of ...

, Kennedy also served several terms in the Maryland General Assembly

The Maryland General Assembly is the state legislature of the U.S. state of Maryland that convenes within the State House in Annapolis. It is a bicameral body: the upper chamber, the Maryland Senate, has 47 representatives and the lower chamber ...

, and became its Speaker in 1847.

Kennedy later helped lead the effort to end slavery

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

in Maryland,"Immediate emancipation in Maryland. Proceedings of the Union State Central Committee, at a meeting held in Temperance Temple, Baltimore, Wednesday, December 16, 1863", 24 pages, Publisher: Cornell University Library (January 1, 1863), , which, as a non-Confederate state, was not affected by the Emancipation Proclamation

The Emancipation Proclamation, officially Proclamation 95, was a presidential proclamation and executive order issued by United States President Abraham Lincoln on January 1, 1863, during the American Civil War, Civil War. The Proclamation c ...

and required a state law to free slaves within its borders and to outlaw the furtherance of the practice.

Kennedy also advocated religious tolerance, and furthered studies of Maryland history. He helped preserve or found Historic St. Mary's City (site of the colonial founding of Maryland and the birthplace of religious freedom in America), St. Mary's College of Maryland (then St. Mary's Female seminary), the Peabody Library (now a part of Johns Hopkins University

Johns Hopkins University (Johns Hopkins, Hopkins, or JHU) is a private research university in Baltimore, Maryland. Founded in 1876, Johns Hopkins is the oldest research university in the United States and in the western hemisphere. It consi ...

) and the Peabody Conservatory of Music

The Peabody Institute of The Johns Hopkins University is a private conservatory and preparatory school in Baltimore, Maryland. It was founded in 1857 and opened in 1866 by merchant/financier and philanthropist George Peabody (1795–1869) ...

(also now a part of Johns Hopkins).

Early life and education

John Pendleton Kennedy was born inBaltimore, Maryland

Baltimore ( , locally: or ) is the most populous city in the U.S. state of Maryland, fourth most populous city in the Mid-Atlantic, and the 30th most populous city in the United States with a population of 585,708 in 2020. Baltimore wa ...

, on October 25, 1795,Ehrlich, Eugene and Gorton Carruth. ''The Oxford Illustrated Literary Guide to the United States''. New York: Oxford University Press, 1982: 218. the son of an Irish immigrant and merchant, John Kennedy. His mother, the former Nancy Pendleton, was descended from the First Families of Virginia

First Families of Virginia (FFV) were those families in Colonial Virginia who were socially prominent and wealthy, but not necessarily the earliest settlers. They descended from English colonists who primarily settled at Jamestown, Williamsbur ...

family. Poor investments resulted in his father declaring bankruptcy in 1809. John Pendleton Kennedy attended private schools while growing up and was relatively well-educated for the time. He graduated from Baltimore College

Baltimore College was a secular college in the city of Baltimore, Maryland, founded in 1804. It was a private non-sectarian institution, although the president of its board of directors when it was formed also happened to be the Roman Catholic bis ...

in 1812. His brother Anthony Kennedy

Anthony McLeod Kennedy (born July 23, 1936) is an American lawyer and jurist who served as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1988 until his retirement in 2018. He was nominated to the court in 1987 by Presid ...

would become a U.S. Senator

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and power ...

.

Kennedy's college studies were interrupted by the War of 1812. He joined the army and in 1814, marched with the United Company of the 5th Baltimore Light Dragoons, known as the "Baltimore 5th," a unit that included rich merchants, lawyers, and other professionals. Kennedy wrote humorous amounts of his military escapades, such as when he lost his boots and marched onward in dancing pumps. The war was, however, serious, and Kennedy participated in the disastrous Battle of Bladensburg as the British threatened the new national capitol, Washington, D.C. Secretary of State

Kennedy's college studies were interrupted by the War of 1812. He joined the army and in 1814, marched with the United Company of the 5th Baltimore Light Dragoons, known as the "Baltimore 5th," a unit that included rich merchants, lawyers, and other professionals. Kennedy wrote humorous amounts of his military escapades, such as when he lost his boots and marched onward in dancing pumps. The war was, however, serious, and Kennedy participated in the disastrous Battle of Bladensburg as the British threatened the new national capitol, Washington, D.C. Secretary of State James Monroe

James Monroe ( ; April 28, 1758July 4, 1831) was an American statesman, lawyer, diplomat, and Founding Father who served as the fifth president of the United States from 1817 to 1825. A member of the Democratic-Republican Party, Monroe was ...

ordered the Baltimore 5th to move back from the left of the forward line to an exposed position a quarter-mile away. After the British forces crossed a bridge, the 5th moved forward. The fighting was intense: nearly every British officer among the advancing troops was hit, but then the British fired Congreve rockets. At first, the 5th stood firm, but when the two regiments to the right ran away, the 5th also broke. Kennedy threw away his musket and carried a wounded fellow-soldier ( James W. McCulloh) to safety. Kennedy later fought in the Battle of North Point, which saved Baltimore from a burning similar to that of the capitol. Another wartime contact who proved crucial in Kennedy's later political and business career was George Peabody, who later helped finance the B&O Railroad and founded the House of Morgan, as well as the Peabody Institute

The Peabody Institute of The Johns Hopkins University is a private conservatory and preparatory school in Baltimore, Maryland. It was founded in 1857 and opened in 1866 by merchant/financier and philanthropist George Peabody (1795–1869) ...

.

Kennedy spent his summers in Martinsburg, Virginia, where he read law under the tutelage of his relative Judge Edmund Pendleton (descendant of the patriot Edmund Pendleton

Edmund Pendleton (September 9, 1721 – October 23, 1803) was an American planter, politician, lawyer, and judge. He served in the Virginia legislature before and during the American Revolutionary War, rising to the position of speaker. Pendleto ...

, who sat on the Virginia Court of Appeals). Kennedy would later often allude to genteel life on Southern plantations based on his youthful summers in Martinsburg.Dilts p. 243 Later, Kennedy inherited some money from a rich Philadelphia uncle, and in 1829 married Elizabeth Gray, whose father Edward Gray was a wealthy mill-owner with a country house on the Patapsco River

The Patapsco River mainstem is a U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map , accessed April 1, 2011 river in central Maryland that flows into the Chesapeake Bay. The river's tidal port ...

below Ellicott's Mills, and whose monetary generosity would allow Kennedy to effectively withdraw from his law practice for a decade to write.

Literary life

Although admitted to the bar in 1816, he was much more interested in literature and politics than law. He associated with the focal point of Baltimore's literary community, theDelphian Club

The Delphian Club was an early American literary club active between 1816 and 1825. The focal point of Baltimore's literary community, Delphians like John Neal were prodigious authors and editors. The group of mostly lawyers and doctors gath ...

. Kennedy's first literary attempt was a fortnightly periodical called the ''Red Book'', published anonymously with his roommate Peter Hoffman Cruse from 1819 to 1820. Kennedy published ''Swallow Barn, or A Sojourn in the Old Dominion'' in 1832, which would become his best-known work. ''Horse-Shoe Robinson

''Horse-Shoe Robinson: A Tale of the Tory Ascendency'' is an 1835 novel by John P. Kennedy that was a popular seller in its day.Hart, James DThe Popular Book: A History of America's Literary Taste p. 305 (1951)(July 1835Literary Notices (book rev ...

'' was published in 1835 to win a permanent place of respect in the history of American fiction.

Kennedy's friends and personal associates included

Kennedy's friends and personal associates included George Henry Calvert

George Henry Calvert (January 2, 1803 – May 24, 1889) was an American editor, essayist, dramatist, poet, and biographer. He was the Chair of Moral Philosophy at the newly established College of Arts and Sciences at the University of Baltimor ...

, James Fenimore Cooper

James Fenimore Cooper (September 15, 1789 – September 14, 1851) was an American writer of the first half of the 19th century, whose historical romances depicting colonist and Indigenous characters from the 17th to the 19th centuries brought ...

, Charles Dickens

Charles John Huffam Dickens (; 7 February 1812 – 9 June 1870) was an English writer and social critic. He created some of the world's best-known fictional characters and is regarded by many as the greatest novelist of the Victorian er ...

, Washington Irving

Washington Irving (April 3, 1783 – November 28, 1859) was an American short-story writer, essayist, biographer, historian, and diplomat of the early 19th century. He is best known for his short stories "Rip Van Winkle" (1819) and " The Legen ...

, Edgar Allan Poe

Edgar Allan Poe (; Edgar Poe; January 19, 1809 – October 7, 1849) was an American writer, poet, editor, and literary critic. Poe is best known for his poetry and short stories, particularly his tales of mystery and the macabre. He is wid ...

, William Gilmore Simms, and William Makepeace Thackeray

William Makepeace Thackeray (; 18 July 1811 – 24 December 1863) was a British novelist, author and illustrator. He is known for his satirical works, particularly his 1848 novel ''Vanity Fair'', a panoramic portrait of British society, and t ...

."John Pendleton Kennedy: Author, Statesman, Patriot", April 15, 2013, Amy Kimball, Materials Manager for Special Collections, The Sheridan Libraries http://blogs.library.jhu.edu/wordpress/2013/04/john-pendleton-kennedy-author-statesman-patriot/

Kennedy's journal entries dated September 1858 state that Thackeray asked him for assistance with a chapter in '' The Virginians''; Kennedy then assisted him by contributing scenic written depictions to that chapter.

While sitting round a back parlor table at the home of noted Baltimore literarist, civic leader and friend John H. B. Latrobe at 11 West Mulberry Street, across from the old Baltimore Cathedral in the Mount Vernon, Baltimore

Mount Vernon is a neighborhood of Baltimore, Maryland, located immediately north of the city's downtown district. Designated a city Cultural District, it is one of the oldest neighborhoods originally home to the city's wealthiest and most fashion ...

neighborhood in October 1833, imbibing some spirits and genial conversation with another friend James H. Miller, they together judged the draft of " MS. Found in a Bottle" from a then-unknown aspiring writer Edgar Allan Poe

Edgar Allan Poe (; Edgar Poe; January 19, 1809 – October 7, 1849) was an American writer, poet, editor, and literary critic. Poe is best known for his poetry and short stories, particularly his tales of mystery and the macabre. He is wid ...

to be worthy of publishing in the '' Baltimore Sunday Visitor'' because of its dark and macabre atmosphere. Also in 1835, he helped later introduce Poe to Thomas Willis White, editor of the ''Southern Literary Messenger

The ''Southern Literary Messenger'' was a periodical published in Richmond, Virginia, from August 1834 to June 1864, and from 1939 to 1945. Each issue carried a subtitle of "Devoted to Every Department of Literature and the Fine Arts" or some va ...

''.

While abroad, Kennedy became a friend of William Makepeace Thackeray

William Makepeace Thackeray (; 18 July 1811 – 24 December 1863) was a British novelist, author and illustrator. He is known for his satirical works, particularly his 1848 novel ''Vanity Fair'', a panoramic portrait of British society, and t ...

and wrote or outlined the fourth chapter of the second volume of '' The Virginians'', a fact which accounts for the great accuracy of its scenic descriptions. Of his works, ''Horse-Shoe Robinson'' is the best and ranks high in antebellum fiction. Washington Irving

Washington Irving (April 3, 1783 – November 28, 1859) was an American short-story writer, essayist, biographer, historian, and diplomat of the early 19th century. He is best known for his short stories "Rip Van Winkle" (1819) and " The Legen ...

read an advance copy of it and reported he was "so tickled with some parts of it" that he read it aloud to his friends. Kennedy sometimes wrote under the pen name 'Mark Littleton', especially in his political satires.

Lawyer and politician

Kennedy enjoyed politics more than law (although the Union Bank was a prime client), and left the Democratic Party when he realized that under President Andrew Jackson it came to oppose internal improvements. He thus became an active Whig like his father-in-law and favored Baltimore's commercial interests. He was appointed Secretary of the Legation inChile

Chile, officially the Republic of Chile, is a country in the western part of South America. It is the southernmost country in the world, and the closest to Antarctica, occupying a long and narrow strip of land between the Andes to the eas ...

on January 27, 1823, but did not proceed to his post, instead resigning on June 23 of the same year. He was elected to the Maryland House of Delegates

The Maryland House of Delegates is the lower house of the legislature of the State of Maryland. It consists of 141 delegates elected from 47 districts. The House of Delegates Chamber is in the Maryland State House on State Circle in Annapolis, ...

in 1820 and chaired its committee on internal improvements, championing the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal

The Chesapeake and Ohio Canal, abbreviated as the C&O Canal and occasionally called the "Grand Old Ditch," operated from 1831 until 1924 along the Potomac River between Washington, D.C. and Cumberland, Maryland. It replaced the Potomac Canal, ...

so vigorously (despite its failure to pay dividends), that he failed to win re-election after his 1823 vote for state support.

In 1838, Kennedy succeeded Isaac McKim

Isaac McKim (July 21, 1775 – April 1, 1838) was a U.S. Representative from Maryland, nephew of Alexander McKim. McKim's five terms as a Congressman saw him change parties three times (from Republican to Jackson Republican to Jacksonian).

Ea ...

in the U.S. House of Representatives, but was defeated in his bid for reelection in November of that year. Meanwhile, in 1835, Kennedy was among the 10 Baltimoreans who attended a railroad meeting in Brownsville, Pennsylvania, where he delivered a very well-received address urging completion of the B&O Railroad

The Baltimore and Ohio Railroad was the first common carrier railroad and the oldest railroad in the United States, with its first section opening in 1830. Merchants from Baltimore, which had benefited to some extent from the construction of ...

to the Ohio River valley (rather than to Pennsylvania canals, which fed Philadelphia rather than Baltimore). Kennedy was also on the 25-man committee that lobbied the Maryland legislature on the B&O's behalf and ultimately secured passage of the "Eight Million Dollar Bill" in 1836, which led to his becoming a B&O board member the following year (and remained such for many years). When the B&O chose a route westward through Virginia rather than the mountains near Hagerstown, Maryland in 1838, Kennedy was in the B&O's delegation to lobby Virginia's legislature (together with B&O President Louis McLane

Louis McLane (May 28, 1786 – October 7, 1857) was an American lawyer and politician from Wilmington, in New Castle County, Delaware, and Baltimore, Maryland. He was a veteran of the War of 1812, a member of the Federalist Party and later th ...

and well-connected Maryland delegate John Spear Nicholas, son of Judge Philip Norborne Nicholas, a leader of the Richmond Junto) that secured passage of a law authorizing a $1,058,000 subscription (40% of the estimated cost for building the B&O through the state). However, the B&O's shareholders would reject the necessary Wheeling subscription because of its onerous terms, and Kennedy would again take up his pen in the B&O's defense against criticism by Maryland Governor William Grason.

Kennedy won re-election to Congress in 1840 and 1842; but, because of his strong opposition to the annexation of Texas

The Texas annexation was the 1845 annexation of the Republic of Texas into the United States. Texas was admitted to the Union as the 28th state on December 29, 1845.

The Republic of Texas declared independence from the Republic of Mexico ...

, he was defeated in 1844. His influence in Congress was largely responsible for the appropriation of $30,000 to test Samuel Morse

Samuel Finley Breese Morse (April 27, 1791 – April 2, 1872) was an American inventor and painter. After having established his reputation as a portrait painter, in his middle age Morse contributed to the invention of a single-wire telegraph ...

's telegraph

Telegraphy is the long-distance transmission of messages where the sender uses symbolic codes, known to the recipient, rather than a physical exchange of an object bearing the message. Thus flag semaphore is a method of telegraphy, whereas ...

. In 1847, Kennedy became speaker of the Maryland House of Delegates, and used his influence to help the B&O, although by the late 1840s it was caught in a three-way controversy with the states of Pennsylvania and Virginia as to whether the B&O's terminus should be Wheeling, Parkersburg or Pittsburgh

Pittsburgh ( ) is a city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, United States, and the county seat of Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, Allegheny County. It is the most populous city in both Allegheny County and Wester ...

. After an acrimonious shareholders meeting on August 25, 1847, the B&O affirmed Wheeling as its terminus, and finally completed track to the city in 1853.

Meanwhile, President Millard Fillmore

Millard Fillmore (January 7, 1800March 8, 1874) was the 13th president of the United States, serving from 1850 to 1853; he was the last to be a member of the Whig Party while in the White House. A former member of the U.S. House of Represen ...

appointed Kennedy as Secretary of the Navy

The secretary of the Navy (or SECNAV) is a statutory officer () and the head (chief executive officer) of the Department of the Navy, a military department (component organization) within the United States Department of Defense.

By law, the se ...

in July 1852. During Kennedy's tenure in office, the Navy organized four important naval expeditions including that which sent Commodore Matthew C. Perry to Japan and Lieutenant William Lewis Herndon

Commander William Lewis Herndon (25 October 1813 – 12 September 1857) was one of the United States Navy's outstanding explorers and seamen. In 1851 he led a United States expedition to the Valley of the Amazon, and prepared a report published ...

and Lieutenant Lardner Gibbon

''Exploration of the Valley of the Amazon'' is a two volume publication by two young USN lieutenants William Lewis Herndon (vol. 1) and Lardner A. Gibbon (vol. 2). Gibbon's dates: Aug. 13, 1820 - Jan. 10, 1910. Herndon split the main party in ...

to explore the Amazon

Amazon most often refers to:

* Amazons, a tribe of female warriors in Greek mythology

* Amazon rainforest, a rainforest covering most of the Amazon basin

* Amazon River, in South America

* Amazon (company), an American multinational technolog ...

.

Kennedy was proposed as a vice-presidential running mate to

Kennedy was proposed as a vice-presidential running mate to Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation throu ...

when Lincoln first sought the Presidency of the United States, although Kennedy was ultimately not selected. Kennedy became a forceful supporter of the Union during the Civil War, and he supported the passage of the Emancipation Proclamation

The Emancipation Proclamation, officially Proclamation 95, was a presidential proclamation and executive order issued by United States President Abraham Lincoln on January 1, 1863, during the American Civil War, Civil War. The Proclamation c ...

. Barbara Jeanne Fields, "Slavery and Freedom on the Middle Ground: Maryland During the Nineteenth Century (Yale Historical Publications Series)", Publisher: Univ Tennessee Press; (July 30, 2012), , Later, since the proclamation did not free Maryland slaves because the state was not in rebellion, he also used his influence to push for legislation in Maryland that ultimately ended slavery there in 1864.

In 1853, he was elected as a member to the American Philosophical Society

The American Philosophical Society (APS), founded in 1743 in Philadelphia, is a scholarly organization that promotes knowledge in the sciences and humanities through research, professional meetings, publications, library resources, and communit ...

.

Position on religious tolerance

Kennedy called for erecting a monument to the founding of the state of Maryland and to the birth of religious freedom in its original colonial settlement in St. Mary's City, Maryland. Three local citizens then expanded on his idea and sought to start a school that would become a "Living Monument" to religious freedom. The school was founded as such a monument in 1840 by order of the state legislature. Its original name was St. Mary's Seminary, but it would later be known as St. Mary's College of Maryland. Earlier, when he was in the Maryland state legislature, Kennedy was instrumental in repealing a law that discriminated against Jewish people in court and trial procedures in Maryland."The unedited full-text of the 1906 Jewish Encyclopedia: 1825", JewishEncyclopedia.com, Note: There are two different "Kennedys" mentioned in this source, 1) Thomas Kennedy, followed later by 2) John Pendleton Kennedy, http://www.jewishencyclopedia.com/articles/10455-maryland Jewish people were a tiny population in the state at the time and Kennedy was not Jewish, so there was no political or personal advantage to his position. His opposition to slavery in Maryland can be traced back for decades but the depth of that opposition went through an evolution from mild and more economically based in the beginning, to being stronger and more morally based by the time of the Emancipation Proclamation."The Life of John Pendleton Kennedy", Henry T. Tuckerman Kuchapishwa na Kessinger Publishing, Llc, , Kennedy, anEpiscopalian

Anglicanism is a Western Christian tradition that has developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the context of the Protestant Reformation in Europe. It is one of the ...

, also helped to lead private charitable efforts to aid Irish Catholic

Irish Catholics are an ethnoreligious group native to Ireland whose members are both Catholic and Irish. They have a large diaspora, which includes over 36 million American citizens and over 14 million British citizens (a quarter of the Briti ...

immigrants,"Forgotten Doors: The Other Ports of Entry to the United States Hardcover", chapter entitled ''Immigration through Baltimore'' Page 66, M. Mark Stolarik, Balch Inst for Ethnic Studies (November 1988) , who were experiencing a great deal of discrimination in the state at the time. However, he did also advocate setting limits on overall foreign national immigration into Maryland beginning in the 1850s, stating that he felt that the sheer number of new immigrants might overwhelm the economy.

Opposition to slavery

Kennedy's opposition to slavery was first publicly expressed in his writings, and then later in his life as a politician, through his speeches and political initiatives. His opposition to slavery in Maryland can be traced back through many decades of his life, but the depth of that opposition went through an evolution from milder and more understated in the beginning, to being stronger, more vocal and more morally based by the time of the

Kennedy's opposition to slavery was first publicly expressed in his writings, and then later in his life as a politician, through his speeches and political initiatives. His opposition to slavery in Maryland can be traced back through many decades of his life, but the depth of that opposition went through an evolution from milder and more understated in the beginning, to being stronger, more vocal and more morally based by the time of the Emancipation Proclamation

The Emancipation Proclamation, officially Proclamation 95, was a presidential proclamation and executive order issued by United States President Abraham Lincoln on January 1, 1863, during the American Civil War, Civil War. The Proclamation c ...

and then the following state-level effort to end slavery in Maryland, as the state was not included in the Emancipation Proclamation because it was not in the Confederacy.

Kennedy once wrote that witnessing a speech by Frederick Douglass

Frederick Douglass (born Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey, February 1817 or 1818 – February 20, 1895) was an American social reformer, abolitionist, orator, writer, and statesman. After escaping from slavery in Maryland, he became ...

had opened his eyes more fully to the "curse" of slavery, as Kennedy called it by 1863.

Kennedy's 1830s novel ''Swallow Barn'' is critical of slavery but also idealizes plantation life. However, the original manuscript shows that some of Kennedy's initial descriptions of plantation life were much more critical of slavery, but that he crossed those out of the manuscript before the book went to the printer, possibly because he was afraid of being too openly critical of slavery while living in Maryland, a slave state.

Historians are not in consensus as to whether his earlier softer opposition to slavery was a way of preventing violent attacks against himself, since he lived in a border state where slavery was still practiced and still widely supported. Outright abolitionism

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery. In Western Europe and the Americas, abolitionism was a historic movement that sought to end the Atlantic slave trade and liberate the enslaved people.

The Britis ...

at that time would have been an unpopular and potentially dangerous position in pro-slavery Maryland. Other historians maintain that his views on slavery simply evolved from weaker opposition to stronger opposition.

The novel, although more muted in its criticism of slavery by the time of its publication and also expressing some idyllic stereotypes about plantation life, leads to the prediction that slavery would bring the Southern states to ruin. ''Swallow Barn'' was published in 1832, 29 years before the start of the Civil War and long before anyone else was known to predict that the Southern and Northern states were headed for armed conflict.

Civil War

Just prior to the Civil War, Kennedy wrote that abolishing slavery immediately was not worth full-scale civil war and that slavery should instead be ended in stages to avoid war. He noted that civil wars were historically the most bloody and devastating kinds of warfare and suggested a negotiated, phased approach to ending slavery to prevent war between the sections. But after the war broke out, he returned to a position of outright opposition to slavery and began to call for "immediate emancipation" of slaves. His demands for the end of slavery grew stronger as the war progressed. By the height of the Civil War, when Kennedy's opposition to slavery had become much stronger, he signed his name to a key political pamphlet in Maryland opposing slavery and calling for its immediate end. There is consensus among historians that Kennedy was critical of slavery to some degree for decades, strongly opposed to slavery by the height of the Civil War, and strongly opposed the Confederacy. In Maryland state politics and charity leadership, Kennedy was also known to help other minority groups, notably Jews and Irish Catholics. When theEmancipation Proclamation

The Emancipation Proclamation, officially Proclamation 95, was a presidential proclamation and executive order issued by United States President Abraham Lincoln on January 1, 1863, during the American Civil War, Civil War. The Proclamation c ...

did not end slavery in Maryland, Kennedy played a key leadership role in campaigning for the end of slavery in the state.

slave state

In the United States before 1865, a slave state was a state in which slavery and the internal or domestic slave trade were legal, while a free state was one in which they were not. Between 1812 and 1850, it was considered by the slave states ...

with strong Confederate sympathies. John Pendleton Kennedy and other antislavery leaders, therefore, organized a political gathering. On December 16, 1863, a special meeting of the Central Committee of the Union Party of Maryland was called on the issue of slavery in the state (the Union Party was a powerful political party in the state at the time).

At the meeting, Thomas Swann

Thomas Swann (February 3, 1809 – July 24, 1883) was an American lawyer and politician who also was President of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad as it completed track to Wheeling and gained access to the Ohio River Valley. Initially a Know-N ...

, a state politician, put forward a motion calling for the party to work for "Immediate emancipation (of all slaves) in Maryland". John Pendleton Kennedy spoke next and seconded the motion. Since Kennedy was the former speaker of the Maryland General Assembly, as well as a respected author, his support carried enormous weight in the party. A vote was taken and the motion passed. However the people of Maryland as a whole were by then divided on the issue and so twelve months of campaigning and lobbying on the matter of slavery continued throughout the state. During this effort, Kennedy signed his name to a party pamphlet calling for "immediate emancipation" of all slaves that was widely circulated. On November 1, 1864, after a year-long debate, a state referendum was put forth on the slavery question. The citizens of Maryland voted to abolish slavery, though only by a 1,000 vote margin, as the Southern part of the state remained heavily dependent on the slave economy.

Work with cultural and educational institutions

Kennedy, in his close association with George Peabody, was instrumental in the establishment of thePeabody Institute

The Peabody Institute of The Johns Hopkins University is a private conservatory and preparatory school in Baltimore, Maryland. It was founded in 1857 and opened in 1866 by merchant/financier and philanthropist George Peabody (1795–1869) ...

, which later evolved and split into the Peabody Library and the Peabody Conservatory of Music

The Peabody Institute of The Johns Hopkins University is a private conservatory and preparatory school in Baltimore, Maryland. It was founded in 1857 and opened in 1866 by merchant/financier and philanthropist George Peabody (1795–1869) ...

, which are now both part of Johns Hopkins University

Johns Hopkins University (Johns Hopkins, Hopkins, or JHU) is a private research university in Baltimore, Maryland. Founded in 1876, Johns Hopkins is the oldest research university in the United States and in the western hemisphere. It consi ...

. He also served on the first board of trustees for the institute and did the first writing that outlined its mission. He also recorded minutes for the board's earliest meetings. Kennedy is known to have worked for years to help lay the groundwork for these institutions.

Kennedy also played an eseential but unintended role in the establishment of St. Mary's Female Seminary which is now known as St. Mary's College of Maryland, the state's public honors college. Kennedy's used his reputation as a respected Maryland politician and author, to call for designating St. Mary's City as the state's ''"Living Monument to religious freedom"'', memorializing its location on the site of Maryland's first colony, which was also considered to be the birthplace of religious freedom in America as well. A few years later three local citizens refined his idea into calling for a school in St. Mary's City that would be the "Living monument". The school continues to have this designation to this day.

Kennedy was the primary initial impetus and was also pivotal in gaining early state recognition of its responsibility for protecting, studying and memorializing St. Mary's City, Maryland"Archaeology, Narrative, and the Politics of the Past: The View from Southern Maryland", Page 64, Julia King, University of Tennessee Press; July 30, 2012, , (the then-abandoned site of Maryland's first colony and capitol, as well as being the birthplace of religious freedom in America),"Reconstructing the Brick Chapel of 1667" Page 1, ''See section entitled'' "The Birthplace of Religious Freedom" as a key state historic area, placing historical research and preservation mandates under the original auspices of the new state-sponsored St. Mary's Female Seminary, located on the same site. This planted the early seeds of what would eventually become Historic St. Mary's City, a state-run archeological research and historic interpretation area that exists today on the site of Maryland's original colonial settlement.

Historic St. Mary's City also co-runs (jointly with St. Mary's College of Maryland) the now internationally recognized Historical Archaeology Field School, a descendant of Kennedy's idea that a school should be involved in researching and preserving the remains of colonial St. Mary's City.

During his term as U.S. Secretary of the Navy, Kennedy made the request for the establishment of the United States Naval Academy Band in Annapolis in 1852."The History of the United States Naval Academy Band", MU1 Doug O'Connor, United States Naval Academy, Naval Academy Band http://www.usna.edu/USNABand/history/ The band continues to be active to this day.

Roles in science and technology

Federal study and acceptance of the telegraph

While serving in the United States Congress, John Pendleton Kennedy was the primary and decisive force in Congress in securing $30,000 (an enormous sum at the time) for testing Samuel Morse'stelegraph

Telegraphy is the long-distance transmission of messages where the sender uses symbolic codes, known to the recipient, rather than a physical exchange of an object bearing the message. Thus flag semaphore is a method of telegraphy, whereas ...

communications system. This was the first electronic means of long-distance communication in human history. The government tests corroborated Morse's invention and led to federal adoption of the technology and the subsequent establishment of the American telegraph communications system, which revolutionized communications and the economic development of the United States. Federal acceptance of the telegraph had a major impact on Abraham Lincoln's management of the Civil War as well.

Commissioner of the 1867 Paris Exposition

Kennedy was a commissioner of the1867 Paris Exposition

The International Exposition of 1867 (french: Exposition universelle 'art et d'industriede 1867), was the second world's fair to be held in Paris, from 1 April to 3 November 1867. A number of nations were represented at the fair. Following a dec ...

, an international science, technology and arts fair that was held in Paris, France, in 1867. The fair had participation from 42 nations and had over 50,000 exhibits. It was the second World's Fair

A world's fair, also known as a universal exhibition or an expo, is a large international exhibition designed to showcase the achievements of nations. These exhibitions vary in character and are held in different parts of the world at a specif ...

.

Retirement from public office

Kennedy retired from elected and appointed offices in March 1853 when President Fillmore left office, but he remained very active in both Federal and state of Maryland politics, supporting Fillmore in1856

Events

January–March

* January 8 – Borax deposits are discovered in large quantities by John Veatch in California.

* January 23 – American paddle steamer SS ''Pacific'' leaves Liverpool (England) for a transatlantic voya ...

, when Fillmore won Maryland's electoral votes and Kennedy's brother Anthony won a U.S. Senate seat. His name was mentioned as one of the vice-presidential prospects on the Republican ticket alongside Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation throu ...

in 1860 (which would have meant that Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation throu ...

would be on the same ticket as a man named "John Kennedy"). Instead, Kennedy was the Maryland chairman of the Constitutional Union Party, which nominated John Bell and Edward Everett

Edward Everett (April 11, 1794 – January 15, 1865) was an American politician, Unitarian pastor, educator, diplomat, and orator from Massachusetts. Everett, as a Whig, served as U.S. representative, U.S. senator, the 15th governor of Mass ...

for the Presidency. Kennedy played an instrumental leadership role in the Union Party's successful effort to end slavery in Maryland in 1864. This had to be done at the state level because the Emancipation Proclamation did not apply to the state. At the end of the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and t ...

– during which he forcefully supported the Union – he advocated amnesty for former rebels.

During this time, he had a summer home overlooking the south branch of the Patapsco River upstream near Orange Grove-Avalon- Ilchester off the main western line of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad

The Baltimore and Ohio Railroad was the first common carrier railroad and the oldest railroad in the United States, with its first section opening in 1830. Merchants from Baltimore, which had benefited to some extent from the construction of ...

now in the area of Patapsco Valley State Park

Patapsco Valley State Park is a Maryland state park extending along of the Patapsco River south and west of the city of Baltimore, Maryland. The park encompasses multiple developed areas on over acres of land, making it Maryland's largest st ...

, which was devastated by a disastrous flood in 1868.

Kennedy died in Newport, Rhode Island

Newport is an American seaside city on Aquidneck Island in Newport County, Rhode Island. It is located in Narragansett Bay, approximately southeast of Providence, south of Fall River, Massachusetts, south of Boston, and northeast of New Yor ...

, on August 18, 1870, and is buried in Greenmount Cemetery in Baltimore, Maryland

Baltimore ( , locally: or ) is the most populous city in the U.S. state of Maryland, fourth most populous city in the Mid-Atlantic, and the 30th most populous city in the United States with a population of 585,708 in 2020. Baltimore wa ...

.

Legacy

In his will, Kennedy wrote the following:It is my wish that the manuscript volumes containing my journals, my note or common-place books, and the several volumes of my own letters in press copy, as also all my other letters, such as may possess any interest or value (which I desire to be bound in volumes) that are now in loose sheets, shall be returned to my executors, who are requested to have the same packed away in a strong walnut box, closed and locked, and then delivered to the Peabody Institute, to be preserved by them unopened until the year 1900, when the same shall become the property of the Institute, to be kept among its books and records.Today there are two large special collections of his papers, manuscripts and correspondence; one remains at the

Peabody Institute

The Peabody Institute of The Johns Hopkins University is a private conservatory and preparatory school in Baltimore, Maryland. It was founded in 1857 and opened in 1866 by merchant/financier and philanthropist George Peabody (1795–1869) ...

in Baltimore and the other is at the Enoch Pratt Free Library

The Enoch Pratt Free Library is the free public library system of Baltimore, Maryland. Its Central Library and office headquarters are located on 400 Cathedral Street (southbound) and occupy the northeastern three quarters of a city block bounded ...

in Baltimore. There are also a number of libraries from Virginia to Boston that have smaller collections of his correspondence (both private and official letters).

The naval ships USS ''John P. Kennedy'' and USS ''Kennedy'' (DD-306) were named for him.

Books and essays

* ''The Red Book'' (1818–19, two volumes). * ''Swallow Barn: Or, A Sojourn in the Old Dominion'' (1832) nder the pen-name Mark Littleton * ''Horse-Shoe Robinson

''Horse-Shoe Robinson: A Tale of the Tory Ascendency'' is an 1835 novel by John P. Kennedy that was a popular seller in its day.Hart, James DThe Popular Book: A History of America's Literary Taste p. 305 (1951)(July 1835Literary Notices (book rev ...

: A Tale of the Tory Ascendency in South Carolina, in 1780'' (1835).

* ''Rob of the Bowl: A Legend of St. Inigoe's'' (1838) nder the pen-name Mark Littleton

* ''Annals of Quodlibet'' nder the pen-name Solomon Secondthoughts(1840).

* ''Defence of the Whigs'' nder the pen-name A Member of the Twenty-seventh Congress(1844).

* ''Memoirs of the Life of William Wirt'' (1849, two volumes).

* ''The Great Drama: An Appeal to Maryland'', Baltimore, reprinted from the Washington ''National Intelligencer'' of May 9, 1861.

* ''The Border States: Their Power and Duty in the Present Disordered Condition of the Country'' (1861).

* ''Autograph Leaves of Our Country's Authors''"Autograph Leaves of our Country's Authors", John Pendleton Kennedy and Alexander Bliss, 1864, Smithsonian Institution, http://americanhistory.si.edu/documentsgallery/exhibitions/gettysburg_address_6.html"Gettysburg Address On Display At The Smithsonian", Jeff Elliot, Abraham Lincoln Blog, November 28, 2008, ''Note: See "about notes" on author Jeff Elliot, who is an historian with 40 years of research experience,'' http://abrahamlincolnblog.blogspot.com/2008_11_01_archive.html [anthology, co-edited by John P. Kennedy and Alexander Bliss] (1864)

* ''Mr. Paul Ambrose's Letters on the American Civil War, Rebellion'' [under the pen-name Paul Ambrose] (1865).

* ''Collected Works of John Pendleton Kennedy'' (1870–72, ten volumes).

* ''At Home and Abroad: A Series of Essays: With a Journal in Europe in 1867–68'' (1872, essays).

Further reading

* Berton, Pierre (1981), '' Flames across the Border: The Canadian-American Tragedy, 1813-1814'', Boston: Atlantic-Little, Brown. *Bohner, Charles H. (1961), ''John Pendleton Kennedy, Gentleman from Baltimore'', Baltimore: Johns Hopkins. *Friedel, Frank (1967), ''Union Pamphlets of the Civil War'', ncludes Kennedy's ''Great Drama'' A John Harvard Library Book, Cambridge, MA: Harvard. *Gwathmey, Edward Moseley (1931), ''John Pendleton Kennedy'', New York: Thomas Nelson. *Hare, John L. (2002), ''Will the Circle be Unbroken?: Family and Sectionalism in the Virginia Novels of Kennedy, Caruthers, and Tucker, 1830—1845'', New York: Routledge. *Marine, William Matthew (1913), ''The British Invasion of Maryland, 1812-1815'', Baltimore: Society of the War of 1812 in Maryland. *Ridgely, Joseph Vincent (1966), ''John Pendleton Kennedy'', New York: Twayne. * Tuckerman, Henry Theodore (1871), ''The Life of John Pendleton Kennedy'', Collected Works of Henry Theodore Tuckerman, Volume 10, New York: Putnam. *Black, Andrew R. (2016), "John Pendleton Kennedy, Early American Novelist, Whig Statesman and Ardent Nationalist", Louisiana State University Press, Louisiana.See also

* History of slavery in Maryland * International Exposition (1867), the second Worlds Fair, held in Paris, of which Kennedy was a commissionerReferences

External links

* *Biography at the Naval Historical Center

John Kennedy

at

Find A Grave

Find a Grave is a website that allows the public to search and add to an online database of cemetery records. It is owned by Ancestry.com. Its stated mission is "to help people from all over the world work together to find, record and present fi ...

Swallow Barn, vol. 1

, - , - , - , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Kennedy, John P. 1795 births 1870 deaths 19th-century American novelists African-American history of Maryland American male novelists 19th-century American memoirists American military personnel of the War of 1812 American people of Irish descent Burials at Green Mount Cemetery Fillmore administration cabinet members History of Baltimore History of slavery in Maryland Johns Hopkins University Maryland lawyers Politicians from Baltimore Speakers of the Maryland House of Delegates St. Mary's City, Maryland St. Mary's College of Maryland St. Mary's County, Maryland United States Secretaries of the Navy Whig Party members of the United States House of Representatives from Maryland 19th-century American politicians Writers from Baltimore American abolitionists Novelists from Maryland American male non-fiction writers