John Murray (oceanographer) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Sir John Murray (3 March 1841 – 16 March 1914) was a pioneering Canadian-born British

Sir John Murray (3 March 1841 – 16 March 1914) was a pioneering Canadian-born British

* Fellow of the

* Fellow of the

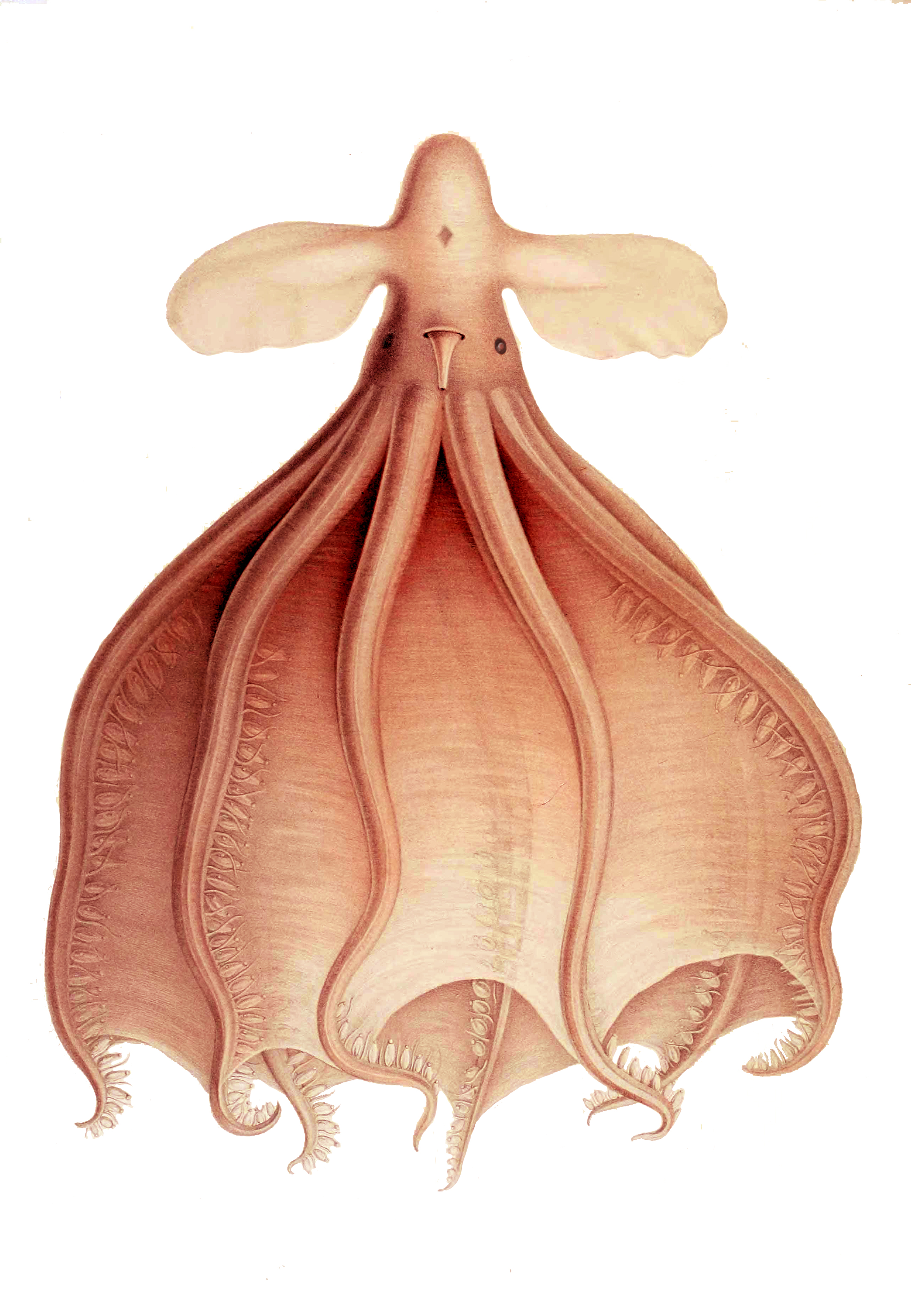

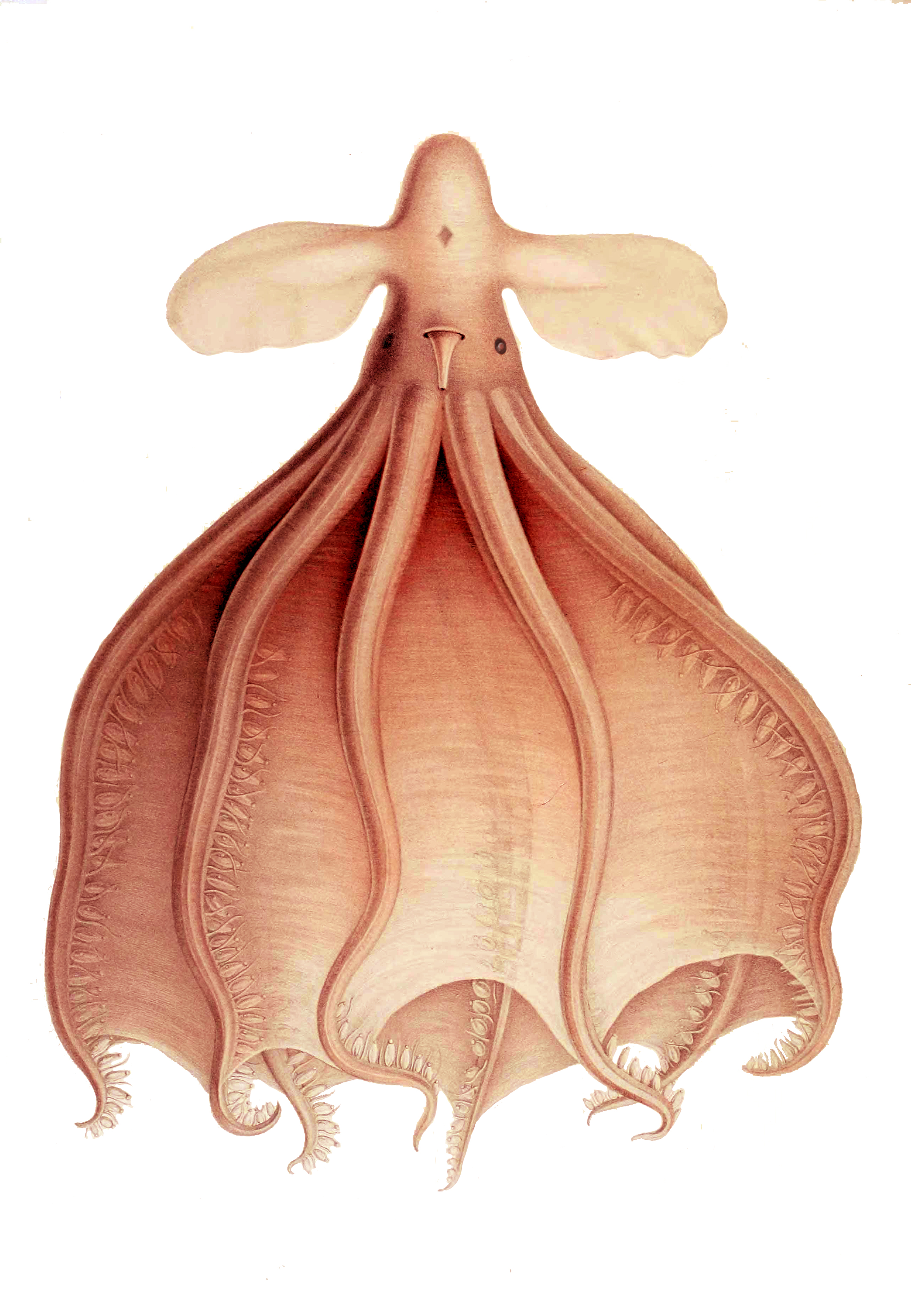

On the 1910 Murray and Hjort expedition and the ''Cirrothauma murrayi'' octopus

{{DEFAULTSORT:Murray, John 1841 births 1914 deaths Knights Commander of the Order of the Bath People from Cobourg Road incident deaths in Scotland People educated at Stirling High School Canadian people of Scottish descent Scottish biologists Scottish explorers Scottish non-fiction writers Alumni of the University of Edinburgh Pre-Confederation Ontario people Royal Medal winners Recipients of the Cullum Geographical Medal Recipients of the Pour le Mérite (civil class) Scottish marine biologists Scottish oceanographers Fellows of the Royal Society Fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh Presidents of the Royal Scottish Geographical Society Foreign associates of the National Academy of Sciences Burials at the Dean Cemetery Scottish surgeons British limnologists Scottish naturalists

oceanographer

Oceanography (), also known as oceanology and ocean science, is the scientific study of the oceans. It is an Earth science, which covers a wide range of topics, including ecosystem dynamics; ocean currents, waves, and geophysical fluid dynamic ...

, marine biologist

Marine biology is the scientific study of the biology of marine life, organisms in the sea. Given that in biology many scientific classification, phyla, family (biology), families and genera have some species that live in the sea and others th ...

and limnologist

Limnology ( ; from Greek λίμνη, ''limne'', "lake" and λόγος, ''logos'', "knowledge") is the study of inland aquatic ecosystems.

The study of limnology includes aspects of the biological, chemical, physical, and geological characteristi ...

. He is considered to be the father of modern oceanography.

Early life and education

Murray was born at Cobourg,Canada West

The Province of Canada (or the United Province of Canada or the United Canadas) was a British colony in North America from 1841 to 1867. Its formation reflected recommendations made by John Lambton, 1st Earl of Durham, in the Report on the ...

(now Ontario

Ontario ( ; ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada.Ontario is located in the geographic eastern half of Canada, but it has historically and politically been considered to be part of Central Canada. Located in Central Ca ...

) on 3 March 1841. He was the second son of Robert Murray, an accountant, and his wife Elizabeth Macfarlane. His parents had emigrate

Emigration is the act of leaving a resident country or place of residence with the intent to settle elsewhere (to permanently leave a country). Conversely, immigration describes the movement of people into one country from another (to permanentl ...

d from Scotland to Ontario in about 1834. He went to school in London, Ontario

London (pronounced ) is a city in southwestern Ontario, Canada, along the Quebec City–Windsor Corridor. The city had a population of 422,324 according to the 2021 Canadian census. London is at the confluence of the Thames River, approximate ...

and later to Cobourg College. In 1858, at the age of 17 he returned to Scotland to live with his grandfather, John Macfarlane, and continue his education at Stirling High School

Stirling High School is a state high school for 11- to 18-year-olds run by Stirling Council in Stirling, Scotland. It is one of seven high schools in the Stirling district, and has approximately 972 pupils. It is located on Torbrex Farm Road, ...

. In 1864 he enrolled at University of Edinburgh

The University of Edinburgh ( sco, University o Edinburgh, gd, Oilthigh Dhùn Èideann; abbreviated as ''Edin.'' in post-nominals) is a public research university based in Edinburgh, Scotland. Granted a royal charter by King James VI in 15 ...

to study medicine however he did not complete his studies and did not graduate.

In 1868 he joined the whaling ship, ''Jan Mayen'', as ship's surgeon and visited Spitsbergen

Spitsbergen (; formerly known as West Spitsbergen; Norwegian: ''Vest Spitsbergen'' or ''Vestspitsbergen'' , also sometimes spelled Spitzbergen) is the largest and the only permanently populated island of the Svalbard archipelago in northern Norw ...

and Jan Mayen Island

Jan Mayen () is a Norwegian volcanic island in the Arctic Ocean with no permanent population. It is long (southwest-northeast) and in area, partly covered by glaciers (an area of around the Beerenberg volcano). It has two parts: larger n ...

. During the seven-month trip, he collected marine specimens and recorded ocean currents, ice movements and the weather.

On his return to Edinburgh

Edinburgh ( ; gd, Dùn Èideann ) is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 Council areas of Scotland, council areas. Historically part of the county of Midlothian (interchangeably Edinburghshire before 1921), it is located in Lothian ...

he re-entered the University to complete his studies (1868–72) in geology under Sir Archibald Geikie

Sir Archibald Geikie (28 December 183510 November 1924) was a Scottish geologist and writer.

Early life

Geikie was born in Edinburgh in 1835, the eldest son of Isabella Thom and her husband James Stuart Geikie, a musician and music critic. T ...

.

Challenger Expedition

In 1872 Murray assisted in preparing scientific apparatus for theChallenger Expedition

The ''Challenger'' expedition of 1872–1876 was a scientific program that made many discoveries to lay the foundation of oceanography. The expedition was named after the naval vessel that undertook the trip, .

The expedition, initiated by Wi ...

under the direction of the expedition's chief scientist, Charles Wyville Thomson. When a position on the expedition became available Murray joined the crew as a naturalist. During the four-year voyage, he assisted in the research of the oceans including collecting marine samples, making and noting observations, and making improvements to marine instrumentation. After the expedition, Murray was appointed Chief Assistant at the Challenger offices in Edinburgh where he managed and organised the collection. After Thomson's death in 1882, Murray became Director of the office and in 1896 published ''The Report on the Scientific Results of the Voyage of HMS Challenger'', a work of more than 50 volumes of reports.

Murray renamed his house, on Boswall Road in northern Edinburgh, ''Challenger Lodge'' in recognition of the expedition. The building now houses St Columba's Hospice.

Marine Laboratory, Granton

In 1884, Murray set up the Marine Laboratory atGranton, Edinburgh

Granton is a district in the north of Edinburgh, Scotland. Granton forms part of Edinburgh's waterfront along the Firth of Forth and is, historically, an industrial area having a large harbour. Granton is part of Edinburgh's large scale waterf ...

, the first of its kind in the United Kingdom. In 1894, this laboratory was moved to Millport, Isle of Cumbrae

Millport (Scottish Gaelic: Port a' Mhuilinn) is the only town on the island of Great Cumbrae in the Firth of Clyde off the coast of mainland Britain, in the council area of North Ayrshire. The town is south of the ferry terminal that links the ...

, on the Firth of Clyde

The Firth of Clyde is the mouth of the River Clyde. It is located on the west coast of Scotland and constitutes the deepest coastal waters in the British Isles (it is 164 metres deep at its deepest). The firth is sheltered from the Atlantic ...

, and became the University Marine Biological Station, Millport, the forerunner of today's Scottish Association for Marine Science

The Scottish Association for Marine Science (SAMS) is one of Europe's leading marine science research organisations, one of the oldest oceanographic organisations in the world and is Scotland's largest and oldest independent marine science org ...

at Dunstaffnage, near Oban

Oban ( ; ' in Scottish Gaelic meaning ''The Little Bay'') is a resort town within the Argyll and Bute council area of Scotland. Despite its small size, it is the largest town between Helensburgh and Fort William. During the tourist season, th ...

, Argyll and Bute

Argyll and Bute ( sco, Argyll an Buit; gd, Earra-Ghàidheal agus Bòd, ) is one of 32 unitary authority council areas in Scotland and a lieutenancy area. The current lord-lieutenant for Argyll and Bute is Jane Margaret MacLeod (14 July 2020) ...

.

Bathymetrical survey of the fresh-water lochs of Scotland

After completing the Challenger Expedition reports, Murray began work surveying the freshwaterlochs

''Loch'' () is the Scottish Gaelic, Scots and Irish word for a lake or sea inlet. It is cognate with the Manx lough, Cornish logh, and one of the Welsh words for lake, llwch.

In English English and Hiberno-English, the anglicised spelling ...

of Scotland. He was assisted by Frederick Pullar and over a period of three years, they surveyed 15 lochs together. In 1901 Pullar drowned as a result of an ice-skating accident which caused Murray to consider abandoning the survey work. However, Pullar's father, Laurence Pullar, persuaded him to continue and gave £10,000 towards the completion of the survey. Murray coordinated a team of nearly 50 people who took more than 60,000 individual depth soundings and recorded other physical characteristics of the 562 lochs. The resulting 6 volume ''Bathymetrical Survey of the Fresh-Water Lochs of Scotland'' was published in 1910.

The cartographer John George Bartholomew

John George Bartholomew (22 March 1860 – 14 April 1920) was a Scottish cartographer and geographer. As a holder of a royal warrant, he used the title "Cartographer to the King"; for this reason he was sometimes known by the epithet "the ...

, who strove to advance geographical and scientific understanding through his cartographic work, drafted and published all the maps of the Survey.

North Atlantic oceanographic expedition

In 1909 Murray indicated to theInternational Council for the Exploration of the Sea

The International Council for the Exploration of the Sea (ICES; french: Conseil International de l'Exploration de la Mer, ''CIEM'') is a regional fishery advisory body and the world's oldest intergovernmental science organization. ICES is headqu ...

that an oceanographic survey of the North Atlantic should be undertaken. After Murray agreed to pay all expenses, the Norwegian Government lent him the research ship ''Michael Sars'' and its scientific crew. He was joined on board by the Norwegian marine biologist Johan Hjort

Johan Hjort (18 February 1869, in Christiania – 7 October 1948, in Oslo) was a Norwegian fisheries scientist, marine zoologist, and oceanographer. He was among the most prominent and influential marine zoologists of his time.

The early yea ...

and the ship departed Plymouth

Plymouth () is a port city and unitary authority in South West England. It is located on the south coast of Devon, approximately south-west of Exeter and south-west of London. It is bordered by Cornwall to the west and south-west.

Plymouth ...

in April 1910 for a four-month expedition to take physical and biological observations at all depths between Europe and North America. Murray and Hjort published their findings in ''The Depths of the Ocean'' in 1912 and it became a classic for marine naturalists and oceanographers.

He was the first to note the existence of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge

The Mid-Atlantic Ridge is a mid-ocean ridge (a divergent or constructive plate boundary) located along the floor of the Atlantic Ocean, and part of the longest mountain range in the world. In the North Atlantic, the ridge separates the North Ame ...

and of oceanic trench

Oceanic trenches are prominent long, narrow topographic depressions of the ocean floor. They are typically wide and below the level of the surrounding oceanic floor, but can be thousands of kilometers in length. There are about of oceanic tren ...

es. He also noted the presence of deposits derived from the Sahara

, photo = Sahara real color.jpg

, photo_caption = The Sahara taken by Apollo 17 astronauts, 1972

, map =

, map_image =

, location =

, country =

, country1 =

, ...

n desert in deep ocean sediments

Sediment is a naturally occurring material that is broken down by processes of weathering and erosion, and is subsequently transported by the action of wind, water, or ice or by the force of gravity acting on the particles. For example, sand a ...

and published many papers on his findings.

Awards, recognition and legacy

* Fellow of the

* Fellow of the Royal Society of Edinburgh

The Royal Society of Edinburgh is Scotland's national academy of science and letters. It is a registered charity that operates on a wholly independent and non-partisan basis and provides public benefit throughout Scotland. It was established i ...

(1877)

* Neill Medal from the Royal Society of Edinburgh (1877)

* Makdougall Brisbane Prize

The Royal Society of Edinburgh is Scotland's national academy of science and letters. It is a registered charity that operates on a wholly independent and non-partisan basis and provides public benefit throughout Scotland. It was established i ...

from the Royal Society of Edinburgh (1884)

* Founder's Medal from the Royal Geographical Society

The Royal Geographical Society (with the Institute of British Geographers), often shortened to RGS, is a learned society and professional body for geography based in the United Kingdom. Founded in 1830 for the advancement of geographical scien ...

(1895)

* Fellow of the Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

(1896)

* Knight Commander of the Order of the Bath

The Most Honourable Order of the Bath is a British order of chivalry founded by George I of Great Britain, George I on 18 May 1725. The name derives from the elaborate medieval ceremony for appointing a knight, which involved Bathing#Medieval ...

(1898)

* Cullum Geographical Medal

The Cullum Geographical Medal is one of the oldest awards of the American Geographical Society. It was established in the will of George Washington Cullum, the vice president of the Society, and is awarded "to those who distinguish themselves by ...

from the American Geographical Society

The American Geographical Society (AGS) is an organization of professional geographers, founded in 1851 in New York City. Most fellows of the society are Americans, but among them have always been a significant number of fellows from around the ...

(1899)

* Clarke Medal

The Clarke Medal is awarded by the Royal Society of New South Wales, the oldest learned society in Australia and the Southern Hemisphere, for distinguished work in the Natural sciences.

The medal is named in honour of the Reverend William Bran ...

from the Royal Society of New South Wales

The Royal Society of New South Wales is a learned society based in Sydney, Australia. The Governor of New South Wales is the vice-regal patron of the Society.

The Society was established as the Philosophical Society of Australasia on 27 June ...

(1900)

* Livingstone Medal The Livingstone Medal is awarded by the Royal Scottish Geographical Society in recognition of outstanding service of a humanitarian nature with a clear geographical dimension. This was awarded first in 1901.

Named after the African explorer David L ...

from the Royal Scottish Geographical Society

The Royal Scottish Geographical Society (RSGS) is an educational charity based in Perth, Scotland founded in 1884. The purpose of the society is to advance the subject of geography worldwide, inspire people to learn more about the world around ...

(1910)

* Vega Medal from the Swedish Society for Anthropology and Geography

The Swedish Society for Anthropology and Geography (SSAG; sv, Svenska Sällskapet för Antropologi och Geografi) is a scientific learned society founded in December 1877. It was established after a rearrangement of various sections of the Anthropo ...

(1912)

Other awards included the Cuvier Prize and Medal from the Institut de France

The (; ) is a French learned society, grouping five , including the Académie Française. It was established in 1795 at the direction of the National Convention. Located on the Quai de Conti in the 6th arrondissement of Paris, the institute m ...

and the Humboldt Medal of the Gesellschaft für Erdkunde zu Berlin

The Gesellschaft für Erdkunde zu Berlin (''Berlin Geographical Society'') was founded in 1828 and is the second oldest geographical society.

It was founded by some of the foremost geographers of its time. The founder Carl Ritter and the foundin ...

.

He was president of the Royal Scottish Geographical Society from 1898 to 1904.

In 1911, Murray founded the Alexander Agassiz Medal

The Alexander Agassiz Medal is awarded every three years by the U.S. National Academy of Sciences for an original contribution in the science of oceanography. It was established in 1911 by Sir John Murray in honor of his friend, the scientist Ale ...

which is awarded by the National Academy of Sciences

The National Academy of Sciences (NAS) is a United States nonprofit, non-governmental organization. NAS is part of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, along with the National Academy of Engineering (NAE) and the Nati ...

, in memory of his friend Alexander Agassiz

Alexander Emmanuel Rodolphe Agassiz (December 17, 1835March 27, 1910), son of Louis Agassiz and stepson of Elizabeth Cabot Agassiz, was an American scientist and engineer.

Biography

Agassiz was born in Neuchâtel, Switzerland and immigrated to ...

(1835–1910).

After his death his estate funded the John Murray Travelling Studentship Fund and the 1933 John Murray ''Mabahiss'' Expedition to the Indian Ocean.

Death

Murray lived at Challenger Lodge (renamed after his expedition) on Boswall Road inTrinity, Edinburgh

Trinity is a district of northern Edinburgh, Scotland, once a part of the burgh of Leith (itself a part of the city since 1920). It is one of the outer villa suburbs of Edinburgh mainly created in the 19th century. It is bordered by Wardie to ...

, with commanding views over the Firth of Forth

The Firth of Forth () is the estuary, or firth, of several Scottish rivers including the River Forth. It meets the North Sea with Fife on the north coast and Lothian on the south.

Name

''Firth'' is a cognate of ''fjord'', a Norse word meani ...

.

In 1905 he and his family rented the House of Falkland for one year.

Murray was killed when his car overturned west of his home on 16 March 1914 at Kirkliston

Kirkliston is a small town and parish to the west of Edinburgh, Scotland, historically within the county of West Lothian but now within the City of Edinburgh council limits. It lies on high ground immediately north of a northward loop of the Al ...

near Edinburgh

Edinburgh ( ; gd, Dùn Èideann ) is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 Council areas of Scotland, council areas. Historically part of the county of Midlothian (interchangeably Edinburghshire before 1921), it is located in Lothian ...

. He is buried in Dean Cemetery

The Dean Cemetery is a historically important Victorian cemetery north of the Dean Village, west of Edinburgh city centre, in Scotland. It lies between Queensferry Road and the Water of Leith, bounded on its east side by Dean Path and on ...

in Edinburgh

Edinburgh ( ; gd, Dùn Èideann ) is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 Council areas of Scotland, council areas. Historically part of the county of Midlothian (interchangeably Edinburghshire before 1921), it is located in Lothian ...

on the central path of the north section in the original cemetery.

His home was converted into St Columba's Hospice in 1977.

Tribute

The ''John Murray Laboratories'' at the University of Edinburgh, the ''John Murray Society'' at the University of Newcastle and theScottish Environment Protection Agency

The Scottish Environment Protection Agency (SEPA; gd, Buidheann Dìon Àrainneachd na h-Alba) is Scotland's Environmental regulation, environmental regulator and national flood forecasting, flood warning and strategic flood risk management au ...

research vessel

A research vessel (RV or R/V) is a ship or boat designed, modified, or equipped to carry out research at sea. Research vessels carry out a number of roles. Some of these roles can be combined into a single vessel but others require a dedicated ...

, the S.V. ''Sir John Murray'', and the Murray Glacier

Murray Glacier () is a valley glacier, long, draining seaward along the east side of Geikie Ridge in the Admiralty Mountains. Its terminus coalesces with that of Dugdale Glacier where both glaciers discharge into Robertson Bay along the north ...

are named after him.

Taxon named in his honor

Animals named in his honor include ''Cirrothauma murrayi

''Cirrothauma murrayi,'' commonly called the "Blind cirrate octopus," is a nearly blind octopus whose eyes can sense light, but not form images. It has been found worldwide, usually beneath the ocean's surface. Like other cirrates, it has an in ...

'', an almost blind octopus that lives at depths from to and the Murrayonida

The Murrayonida are an order of sea sponges in the subclass Calcinea.

Taxonomy

The order consists of four known species, in three families:

Family Murrayonidae Dendy & Row, 1913

* '' Murrayona phanolepis'' Kirkpatrick, 1910 - discovered by ...

order of sea sponge

Sponges, the members of the phylum Porifera (; meaning 'pore bearer'), are a basal animal clade as a sister of the diploblasts. They are multicellular organisms that have bodies full of pores and channels allowing water to circulate through t ...

s are named after Murray. '' Silvascincus murrayi'' (Murray's skink), a species of Australian lizard, is named in his honour.

'' Halieutopsis murrayi'' H. C. Ho, 2022 (Murray’s deepsea batfish)

'' Trachyrhynchus murrayi'' Günther, 1887

The salt water worm '' Phallonemertes murrayi'' (Brinkmann, 1912)

'' Murrayona'' Kirkpatrick, 1910

'' Stellitethya murrayi'' Sarà & Bavestrello, 1996

The fish '' Triglops murrayi'' Günther, 1888

'' Munneurycope murrayi'' (Walker, 1903)

'' Lanceola murrayi'' Norman, 1900

'' Potamethus murrayi'' (M'Intosh, 1916)

'' Mesothuria murrayi'' (Théel, 1886)

'' Bythotiara murrayi'' Günther, 1903

'' Anthoptilum murrayi'' Kölliker, 1880

'' Sophrosyne murrayi'' Stebbing, 1888

'' Millepora murrayi'' Quelch, 1886

'' Phascolion murrayi'' Stephen, 1941

'' Munnopsurus murrayi'' (Walker, 1903)

The Blind Octopus ''Cirrothauma murrayi

''Cirrothauma murrayi,'' commonly called the "Blind cirrate octopus," is a nearly blind octopus whose eyes can sense light, but not form images. It has been found worldwide, usually beneath the ocean's surface. Like other cirrates, it has an in ...

'' Chun, 1911

'' Culeolus murrayi'' Herdman, 1881

'' Deltocyathus murrayi'' Gardiner & Waugh, 1938

''Bathyraja murrayi

''Bathyraja'' is a large genus of skates in the family Arhynchobatidae.

Species

There are 55 recognized species in this genus:Orr, J.W., Stevenson, D.E., Hoff, G.R., Spies, I. & McEachran, J.D. (2011)Bathyraja panthera, ''a new species of skate ...

'' ( Günther, 1880)

'' Psammastra murrayi'' Sollas, 1886

''Lithodes murrayi

''Lithodes'' is a genus of king crabs. Today there are about 30 recognized species, but others formerly included in this genus have been moved to '' Neolithodes'' and '' Paralomis''. They are found in oceans around the world, ranging from shallow ...

'' Henderson, 1888

''Pythonaster murrayi

''Pythonaster'' is a genus of deep-sea velatid sea star

Starfish or sea stars are star-shaped echinoderms belonging to the class Asteroidea (). Common usage frequently finds these names being also applied to ophiuroids, which are correct ...

'' Sladen, 1889https://www.bemon.loven.gu.se/, Biographical Etymology of Marine Organism Names (BEMON)

Botanical references

See also

*European and American voyages of scientific exploration

The era of European and American voyages of scientific exploration followed the Age of Discovery and were inspired by a new confidence in science and reason that arose in the Age of Enlightenment. Maritime expeditions in the Age of Discovery were ...

References

External links

* * *On the 1910 Murray and Hjort expedition and the ''Cirrothauma murrayi'' octopus

{{DEFAULTSORT:Murray, John 1841 births 1914 deaths Knights Commander of the Order of the Bath People from Cobourg Road incident deaths in Scotland People educated at Stirling High School Canadian people of Scottish descent Scottish biologists Scottish explorers Scottish non-fiction writers Alumni of the University of Edinburgh Pre-Confederation Ontario people Royal Medal winners Recipients of the Cullum Geographical Medal Recipients of the Pour le Mérite (civil class) Scottish marine biologists Scottish oceanographers Fellows of the Royal Society Fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh Presidents of the Royal Scottish Geographical Society Foreign associates of the National Academy of Sciences Burials at the Dean Cemetery Scottish surgeons British limnologists Scottish naturalists