John Marshall Harlan II on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

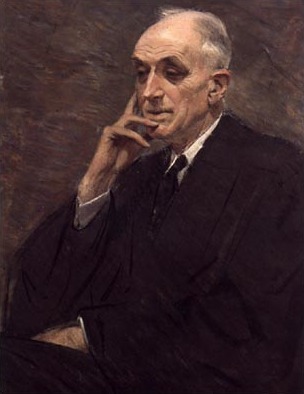

John Marshall Harlan (May 20, 1899 – December 29, 1971) was an American lawyer and jurist who served as an

Harlan's nomination came shortly after the Supreme Court handed down its landmark decision in '' Brown v. Board of Education'', declaring segregation in public schools unconstitutional. James Eastland (the chairman of the United States Senate Committee on the Judiciary) and several other southern senators delayed his confirmation, because they (correctly) believed that he would support desegregation of the schools and

Harlan's nomination came shortly after the Supreme Court handed down its landmark decision in '' Brown v. Board of Education'', declaring segregation in public schools unconstitutional. James Eastland (the chairman of the United States Senate Committee on the Judiciary) and several other southern senators delayed his confirmation, because they (correctly) believed that he would support desegregation of the schools and

John M. Harlan Papers at the Seeley G. Mudd Manuscript Library, Princeton University

*

Public Broadcasting Service. *

"John Marshall Harlan II."

''Booknotes'' interview with Tinsley Yarbrough on ''John Marshall Harlan: Great Dissenter of the Warren Court'', April 26, 1992.

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Harlan, John Marshall II 1899 births 1971 deaths 20th-century American judges Alumni of Balliol College, Oxford United States Army personnel of World War II American Presbyterians American people of Scotch-Irish descent American Rhodes Scholars Appleby College alumni Assistant United States Attorneys Deaths from cancer in Washington, D.C. Neurological disease deaths in Washington, D.C. Deaths from spinal cancer Fellows of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences Judges of the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit Latin School of Chicago alumni Lawyers from Chicago Military personnel from Illinois New York Law School alumni New York (state) Republicans People from Weston, Connecticut Princeton University alumni Recipients of the Croix de guerre (Belgium) Recipients of the Croix de Guerre 1939–1945 (France) Recipients of the Legion of Merit United States Army officers United States court of appeals judges appointed by Dwight D. Eisenhower Justices of the Supreme Court of the United States Upper Canada College alumni Harlan family Conservatism in the United States

associate justice of the U.S. Supreme Court

An associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States is any member of the Supreme Court of the United States other than the chief justice of the United States. The number of associate justices is eight, as set by the Judiciary Act of 1 ...

from 1955 to 1971. Harlan is usually called John Marshall Harlan II to distinguish him from his grandfather John Marshall Harlan, who served on the U.S. Supreme Court from 1877 to 1911.

Harlan was a student at Upper Canada College and Appleby College and then at Princeton University

Princeton University is a private research university in Princeton, New Jersey. Founded in 1746 in Elizabeth as the College of New Jersey, Princeton is the fourth-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and one of the ...

. Awarded a Rhodes Scholarship

The Rhodes Scholarship is an international postgraduate award for students to study at the University of Oxford, in the United Kingdom.

Established in 1902, it is the oldest graduate scholarship in the world. It is considered among the world' ...

, he studied law at Balliol College, Oxford. Upon his return to the U.S. in 1923 Harlan worked in the law firm of Root, Clark, Buckner & Howland while studying at New York Law School

New York Law School (NYLS) is a private law school in Tribeca, New York City. NYLS has a full-time day program and a part-time evening program. NYLS's faculty includes 54 full-time and 59 adjunct professors. Notable faculty members include ...

. Later he served as Assistant U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of New York and as Special Assistant Attorney General of New York. In 1954 Harlan was appointed to the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit, and a year later president Dwight Eisenhower nominated Harlan to the United States Supreme Court following the death of Justice Robert H. Jackson

Robert Houghwout Jackson (February 13, 1892 – October 9, 1954) was an American lawyer, jurist, and politician who served as an Associate Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court from 1941 until his death in 1954. He had previously served as Unit ...

.

Harlan is often characterized as a member of the conservative wing of the Warren Court. He advocated a limited role for the judiciary, remarking that the Supreme Court should not be considered "a general haven for reform movements". In general, Harlan adhered more closely to precedent

A precedent is a principle or rule established in a previous legal case that is either binding on or persuasive for a court or other tribunal when deciding subsequent cases with similar issues or facts. Common-law legal systems place great v ...

, and was more reluctant to overturn legislation, than many of his colleagues on the Court. He strongly disagreed with the doctrine of incorporation, which held that the provisions of the federal Bill of Rights applied to the state governments, not merely the Federal. At the same time, he advocated a broad interpretation

Interpretation may refer to:

Culture

* Aesthetic interpretation, an explanation of the meaning of a work of art

* Allegorical interpretation, an approach that assumes a text should not be interpreted literally

* Dramatic Interpretation, an event ...

of the Fourteenth Amendment's Due Process Clause, arguing that it protected a wide range of rights not expressly mentioned in the United States Constitution

The Constitution of the United States is the supreme law of the United States of America. It superseded the Articles of Confederation, the nation's first constitution, in 1789. Originally comprising seven articles, it delineates the natio ...

. Justice Harlan was gravely ill when he retired from the Supreme Court on September 23, 1971. He died from spinal cancer

Spinal tumors are neoplasms located in either the vertebral column or the spinal cord. There are three main types of spinal tumors classified based on their location: extradural and intradural (intradural-intramedullary and intradural-extramedulla ...

three months later, on December 29, 1971. After Harlan's retirement, President Nixon appointed William Rehnquist to replace him.

Early life and career

John Marshall Harlan was born on May 20, 1899, inChicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = List of sovereign states, Count ...

. He was the son of John Maynard Harlan, a Chicago lawyer and politician, and Elizabeth Flagg. He had three sisters. Historically, Harlan's family had been politically active. His forebear George Harlan served as one of the governors of Delaware

Delaware ( ) is a state in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States, bordering Maryland to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; and New Jersey and the Atlantic Ocean to its east. The state takes its name from the adjacent ...

during the seventeenth century; his great-grandfather James Harlan was a congressman during the 1830s; his grandfather, also John Marshall Harlan, was an associate justice of the United States Supreme Court from 1877 to 1911; and his uncle, James S. Harlan

James S. Harlan (November 24, 1861 – September 20, 1927) was an American lawyer and commerce specialist, son of U.S. Supreme Court Justice John Marshall Harlan and uncle of Justice John Marshall Harlan II.

Biography

Harlan was born at Evans ...

, was attorney general of Puerto Rico

Puerto Rico (; abbreviated PR; tnq, Boriken, ''Borinquen''), officially the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico ( es, link=yes, Estado Libre Asociado de Puerto Rico, lit=Free Associated State of Puerto Rico), is a Caribbean island and unincorporated ...

and then chairman of the Interstate Commerce Commission

The Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) was a regulatory agency in the United States created by the Interstate Commerce Act of 1887. The agency's original purpose was to regulate railroads (and later trucking) to ensure fair rates, to elimina ...

.Dorsen

Dorsen is a surname. Notable people with the surname include:

* Annie Dorsen (born 1973), American theater director

* Norman Dorsen (1930–2017), American attorney, author, and law professor

See also

* Doreen (given name)

Doreen (, DAWR-een), ...

, 2002, pp. 139–143

In his younger years, Harlan attended The Latin School of Chicago. Yarbrough, 1992, pp. 10–11 He later attended two boarding high schools in the Toronto Area, Canada: Upper Canada College and Appleby College. Upon graduation from Appleby, Harlan returned to the U.S. and in 1916 enrolled at Princeton University

Princeton University is a private research university in Princeton, New Jersey. Founded in 1746 in Elizabeth as the College of New Jersey, Princeton is the fourth-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and one of the ...

. There, he was a member of the Ivy Club, served as an editor of '' The Daily Princetonian'', and was class president during his junior and senior years. After graduating from the university in 1920 with an Artium Baccalaureus

Bachelor of arts (BA or AB; from the Latin ', ', or ') is a bachelor's degree awarded for an undergraduate program in the arts, or, in some cases, other disciplines. A Bachelor of Arts degree course is generally completed in three or four years ...

degree, he received a Rhodes Scholarship

The Rhodes Scholarship is an international postgraduate award for students to study at the University of Oxford, in the United Kingdom.

Established in 1902, it is the oldest graduate scholarship in the world. It is considered among the world' ...

, which he used to attend Balliol College, Oxford, making him the first Rhodes Scholar to sit on the Supreme Court. Leitch 1978, pp. ? He studied jurisprudence at Oxford for three years, returning from England in 1923. Upon his return to the United States, he began work with the law firm of Root, Clark, Buckner & Howland (which became Dewey & LeBoeuf

Dewey & LeBoeuf LLP was a global law firm headquartered in New York City, United States. Some of the firm's leaders were indicted for fraud for their role in allegedly cooking the company's books to obtain loans while hiding the firm's financial ...

), one of the leading law firms in the country, while studying law at New York Law School

New York Law School (NYLS) is a private law school in Tribeca, New York City. NYLS has a full-time day program and a part-time evening program. NYLS's faculty includes 54 full-time and 59 adjunct professors. Notable faculty members include ...

. He received his Bachelor of Laws

Bachelor of Laws ( la, Legum Baccalaureus; LL.B.) is an undergraduate law degree in the United Kingdom and most common law jurisdictions. Bachelor of Laws is also the name of the law degree awarded by universities in the People's Republic of Ch ...

in 1924 and earned admission to the bar in 1925. Yarbrough, 1992, pp. 13–16

Between 1925 and 1927, Harlan served as Assistant United States Attorney

An assistant United States attorney (AUSA) is an official career civil service position in the U.S. Department of Justice composed of lawyers working under the U.S. Attorney of each U.S. federal judicial district. They represent the federal go ...

for the Southern District of New York, heading the district's Prohibition

Prohibition is the act or practice of forbidding something by law; more particularly the term refers to the banning of the manufacture, storage (whether in barrels or in bottles), transportation, sale, possession, and consumption of alcoholi ...

unit. He prosecuted Harry M. Daugherty

Harry Micajah Daugherty (; January 26, 1860 – October 12, 1941) was an American politician. A key Ohio Republican political insider, he is best remembered for his service as Attorney General of the United States under Presidents Warren G. Hard ...

, former United States Attorney General. In 1928, he was appointed Special Assistant Attorney General of New York

The attorney general of New York is the chief legal officer of the U.S. state of New York and head of the Department of Law of the state government. The office has been in existence in some form since 1626, under the Dutch colonial government ...

, in which capacity he investigated a scandal involving sewer construction in Queens

Queens is a borough of New York City, coextensive with Queens County, in the U.S. state of New York. Located on Long Island, it is the largest New York City borough by area. It is bordered by the borough of Brooklyn at the western tip of Long ...

. He prosecuted Maurice E. Connolly, the Queens borough president, for his involvement in the affair. In 1930, Harlan returned to his old law firm, becoming a partner one year later. At the firm, he served as chief assistant for senior partner Emory Buckner and followed him into public service when Buckner was appointed United States Attorney for the Southern District of New York. As one of "Buckner's Boy Scouts", eager young Assistant United States Attorneys, Harlan worked on Prohibition cases, and swore off drinking except when the prosecutors visited the Harlan family fishing camp in Quebec

Quebec ( ; )According to the Canadian government, ''Québec'' (with the acute accent) is the official name in Canadian French and ''Quebec'' (without the accent) is the province's official name in Canadian English is one of the thirte ...

, where Prohibition did not apply. Harlan remained in public service until 1930, and then returned to his firm. Buckner had also returned to the firm, and after Buckner's death, Harlan became the leading trial lawyer at the firm.

As a trial lawyer Harlan was involved in a number of famous cases. One such case was the conflict over the estate left after the death in 1931 of Ella Wendel, who had no heirs and left almost all her wealth, estimated at $30–100 million, to churches and charities. However, a number of claimants, most of them imposters, filed suits in state and federal courts seeking part of her fortune. Harlan acted as the main defender of her estate and will as well as the chief negotiator. Eventually a settlement among lawful claimants was reached in 1933. Yarbrough, 1992, pp. 41–51 In the following years Harlan specialized in corporate law dealing with the cases like ''Randall v. Bailey'',288 N.Y. 280, 43 N.E.2d 43 (1942) concerning the interpretation of state law governing distribution of corporate dividends

A dividend is a distribution of profits by a corporation to its shareholders. When a corporation earns a profit or surplus, it is able to pay a portion of the profit as a dividend to shareholders. Any amount not distributed is taken to be re-in ...

. In 1940, he represented the New York Board of Higher Education unsuccessfully in the Bertrand Russell case in its efforts to retain Bertrand Russell

Bertrand Arthur William Russell, 3rd Earl Russell, (18 May 1872 – 2 February 1970) was a British mathematician, philosopher, logician, and public intellectual. He had a considerable influence on mathematics, logic, set theory, linguistics, a ...

on the faculty of the City College of New York

The City College of the City University of New York (also known as the City College of New York, or simply City College or CCNY) is a public university within the City University of New York (CUNY) system in New York City. Founded in 1847, Cit ...

; Russell was declared "morally unfit" to teach. The future justice also represented boxer Gene Tunney in a breach of contract suit brought by a would-be fight manager, a matter settled out of court. Yarbrough, 1992, pp. 52–53

In 1937, Harlan was one of five founders of a eugenics

Eugenics ( ; ) is a fringe set of beliefs and practices that aim to improve the genetic quality of a human population. Historically, eugenicists have attempted to alter human gene pools by excluding people and groups judged to be inferior o ...

advocacy group called the Pioneer Fund, which had been formed to introduce Nazi ideas on eugenics to the United States. He had likely been invited into the group due to his expertise in non-profit organizations. Harlan served on the Pioneer Fund's board until 1954. He did not play a significant role in the fund. Tucker, 2002, pp. 6, 51–53

During World War II, Harlan volunteered for military duty, serving as a colonel

Colonel (abbreviated as Col., Col or COL) is a senior military officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, a colonel was typically in charge ...

in the United States Army Air Force

The United States Army Air Forces (USAAF or AAF) was the major land-based aerial warfare service component of the United States Army and ''de facto'' aerial warfare service branch of the United States during and immediately after World War I ...

from 1943 to 1945. He was the chief of the Operational Analysis Section of the Eighth Air Force in England. He won the Legion of Merit

The Legion of Merit (LOM) is a military award of the United States Armed Forces that is given for exceptionally meritorious conduct in the performance of outstanding services and achievements. The decoration is issued to members of the eight u ...

from the United States, and the Croix de Guerre from both France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

and Belgium

Belgium, ; french: Belgique ; german: Belgien officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a country in Northwestern Europe. The country is bordered by the Netherlands to the north, Germany to the east, Luxembourg to the southeast, France to ...

. In 1946 Harlan returned to private law practice representing Du Pont family

The du Pont family () or Du Pont family is a prominent American family descended from Pierre Samuel du Pont de Nemours (1739–1817). It has been one of the richest families in the United States since the mid-19th century, when it founded its f ...

members against a federal antitrust lawsuit. In 1951, however, he returned to public service, serving as Chief Counsel to the New York State Crime Commission, where he investigated the relationship between organized crime and the state government as well as illegal gambling activities in New York and other areas. During this period Harlan also served as a committee chairman of the Association of the Bar of the City of New York, and to which he was later elected vice president. Harlan's main specialization at that time was corporate and antitrust law.

Personal life

In 1928, Harlan married Ethel Andrews, who was the daughter of Yale history professorCharles McLean Andrews

Charles McLean Andrews (February 22, 1863 – September 9, 1943) was an American historian, an authority on American colonial history.Roth, David M., editor, and Grenier, Judith Arnold, associate editor, "Connecticut History and Culture: An Hist ...

. This was the second marriage for her. Ethel was originally married to New York architect Henry K. Murphy, who was twenty years her elder. After Ethel divorced Murphy in 1927, her brother John invited her to a Christmas party at Root, Clark, Buckner & Howland, where she was introduced to John Harlan. They saw each other regularly afterwards and married on November 10, 1928, in Farmington, Connecticut.

Harlan, a Presbyterian

Presbyterianism is a part of the Reformed tradition within Protestantism that broke from the Roman Catholic Church in Scotland by John Knox, who was a priest at St. Giles Cathedral (Church of Scotland). Presbyterian churches derive their n ...

, maintained a New York City apartment, a summer home in Weston, Connecticut, and a fishing camp in Murray Bay, Quebec, a lifestyle he described as "awfully tame and correct". The justice played golf, favored tweeds, and wore a gold watch which had belonged to the first Justice Harlan. In addition to carrying his grandfather's watch, when he joined the Supreme Court he used the same furniture which had furnished his grandfather's chambers.

John and Ethel Harlan had one daughter, Evangeline Dillingham (born on February 2, 1932). Yarbrough, 1992, pp. 33–35, 41. She was married to Frank Dillingham of West Redding, Connecticut, until his death, and has five children. One of Eve's children, Amelia Newcomb, is the international news editor at ''The Christian Science Monitor

''The Christian Science Monitor'' (''CSM''), commonly known as ''The Monitor'', is a nonprofit news organization that publishes daily articles in electronic format as well as a weekly print edition. It was founded in 1908 as a daily newspaper ...

'' and has two children: Harlan, named after John Marshall Harlan II, and Matthew Trevithick. Another daughter, Kate Dillingham, is a professional cellist and published author.

Second Circuit service

Harlan was nominated by President Dwight D. Eisenhower on January 13, 1954, to a seat on the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit vacated by JudgeAugustus Noble Hand

Augustus Noble Hand (July 26, 1869 – October 28, 1954) was a United States district judge of the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York and later was a United States Circuit Judge of the United States Court of Appeals ...

. Harlan knew this court well, as he had often appeared before it and was friendly with many of the judges. He was confirmed by the United States Senate

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and po ...

on February 9, 1954, and received his commission on the next day. His service terminated on March 27, 1955, due to his elevation to the Supreme Court.

Supreme Court service

Harlan was nominated by President Eisenhower on January 10, 1955, as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States, to succeedRobert H. Jackson

Robert Houghwout Jackson (February 13, 1892 – October 9, 1954) was an American lawyer, jurist, and politician who served as an Associate Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court from 1941 until his death in 1954. He had previously served as Unit ...

. On being nominated, the reticent Harlan called reporters into his chambers in New York, and stated, in full, "I am very deeply honored." He was confirmed by the Senate on March 16, 1955, by a 71-11 vote, and was sworn into office on March 28, 1955. Despite the brevity of his stay on the Second Circuit, Harlan would serve as the Circuit Justice

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. federal court cases, and over state court cases that involve a point of ...

responsible for the Second Circuit throughout his Supreme Court capacity, and, in that capacity, enjoyed attending the Circuit's annual conference, bringing his wife and catching up on the latest gossip. Additionally, he served as Circuit Justice for the Ninth Circuit from June 25 to June 26, 1963. He assumed retired status on September 23, 1971, serving in that capacity until his death on December 29, 1971.

Harlan's nomination came shortly after the Supreme Court handed down its landmark decision in '' Brown v. Board of Education'', declaring segregation in public schools unconstitutional. James Eastland (the chairman of the United States Senate Committee on the Judiciary) and several other southern senators delayed his confirmation, because they (correctly) believed that he would support desegregation of the schools and

Harlan's nomination came shortly after the Supreme Court handed down its landmark decision in '' Brown v. Board of Education'', declaring segregation in public schools unconstitutional. James Eastland (the chairman of the United States Senate Committee on the Judiciary) and several other southern senators delayed his confirmation, because they (correctly) believed that he would support desegregation of the schools and civil rights

Civil and political rights are a class of rights that protect individuals' freedom from infringement by governments, social organizations, and private individuals. They ensure one's entitlement to participate in the civil and political life ...

.Dorsen

Dorsen is a surname. Notable people with the surname include:

* Annie Dorsen (born 1973), American theater director

* Norman Dorsen (1930–2017), American attorney, author, and law professor

See also

* Doreen (given name)

Doreen (, DAWR-een), ...

, 2006 Unlike almost all previous Supreme Court nominees, Harlan appeared before the Senate Judiciary Committee to answer questions relating to his judicial views. Every Supreme Court nominee since Harlan has been questioned by the Judiciary Committee before confirmation. The Senate finally confirmed him on March 17, 1955, by a vote of 71–11.Epstein The surname Epstein ( yi, עפּשטײן, Epshteyn) is one of the oldest Ashkenazi Jewish family names. It is probably derived from the German town of Eppstein, in Hesse; the place-name was probably derived from Gaulish ''apa'' ("water", in the sen ...

, 2005 He took his seat on March 28, 1955. Of the eleven senators who voted against his appointment, nine were from the South. He was replaced on the Second Circuit by Joseph Edward Lumbard.

On the Supreme Court, Harlan often voted alongside Justice Felix Frankfurter, who was his principal mentor on the court. Some legal scholars even viewed him as "Frankfurter without mustard", though others recognize his own important contributions to the evolution of legal thought. Harlan was an ideological adversary—but close personal friend—of Justice Hugo Black

Hugo Lafayette Black (February 27, 1886 – September 25, 1971) was an American lawyer, politician, and jurist who served as a U.S. Senator from Alabama from 1927 to 1937 and as an associate justice of the U.S. Supreme Court from 1937 to 1971. ...

, with whom he disagreed on a variety of issues, including the applicability of the Bill of Rights to the states, the Due Process Clause, and the Equal Protection Clause.

Justice Harlan was very close to the law clerks whom he hired, and continued to take an interest in them after they left his chambers to continue their legal careers. The justice would advise them on their careers, hold annual reunions, and place pictures of their children on his chambers' walls. He would say to them of the Warren Court, "We must consider this only temporary," that the Court had gone astray, but would soon right itself.

Justice Harlan is remembered by people who worked with him for his tolerance and civility. He treated his fellow Justices, clerks and attorneys representing parties with respect and consideration. While Justice Harlan often strongly objected to certain conclusions and arguments, he never criticized other justices or anybody else personally, and never said any disparaging words about someone's motivations and capacity.Dorsen

Dorsen is a surname. Notable people with the surname include:

* Annie Dorsen (born 1973), American theater director

* Norman Dorsen (1930–2017), American attorney, author, and law professor

See also

* Doreen (given name)

Doreen (, DAWR-een), ...

, 2002, pp. 147, 156, 162. Harlan was reluctant to show emotion, and was never heard to complain about anything. Harlan was one of the intellectual leaders of the Warren Court. Harvard Constitutional law expert Paul Freund said of him:

His thinking threw light in a very introspective way on the entire process of the judicial function. His decisions, beyond just the vote they represented, were sufficiently philosophical to be of enduring interest. He decided the case before him with that respect for its particulars, its special features, that marks alike the honest artist and the just judge.

Jurisprudence

Harlan's jurisprudence is often characterized as conservative. He heldprecedent

A precedent is a principle or rule established in a previous legal case that is either binding on or persuasive for a court or other tribunal when deciding subsequent cases with similar issues or facts. Common-law legal systems place great v ...

to be of great importance, adhering to the principle of ''stare decisis

A precedent is a principle or rule established in a previous legal case that is either binding on or persuasive for a court or other tribunal when deciding subsequent cases with similar issues or facts. Common-law legal systems place great va ...

'' more closely than many of his Supreme Court colleagues. Unlike Justice Black, he eschewed strict textualism. While he believed that the original intention of the Framers should play an important part in constitutional adjudication, he also held that broad phrases like "liberty" in the Due Process Clause could be given an evolving interpretation. Dripps, 2005, pp. 125–131

Harlan believed that most problems should be solved by the political process, and that the judiciary should play only a limited role. In his dissent to '' Reynolds v. Sims'',, Harlan J., dissenting he wrote:

These decisions give support to a current mistaken view of the Constitution and the constitutional function of this court. This view, in short, is that every major social ill in this country can find its cure in some constitutional principle and that this court should take the lead in promoting reform when other branches of government fail to act. The Constitution is not a panacea for every blot upon the public welfare nor should this court, ordained as a judicial body, be thought of as a general haven of reform movements.However, Harlan was not a social conservative. He wrote the plurality opinion in

Manual Enterprises, Inc. v. Day

''MANual Enterprises, Inc. v. Day'', 370 U.S. 478 (1962), is a decision by the United States Supreme Court which held that magazines consisting largely of photographs of nude or near-nude male models are not obscene within the meaning of . It was ...

, ruling that photographs of nude men are not obscene, one of the first major victories for the early gay rights movement.

Despite Harlan’s conservatism, he opposed the Vietnam War

The Vietnam War (also known by #Names, other names) was a conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia from 1 November 1955 to the fall of Saigon on 30 April 1975. It was the second of the Indochina Wars and was officially fought between North Vie ...

and along with Justices William O. Douglas, Potter Stewart

Potter Stewart (January 23, 1915 – December 7, 1985) was an American lawyer and judge who served as an Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court from 1958 to 1981. During his tenure, he made major contributions to, among other areas ...

and William J. Brennan Jr. unsuccessfully pushed for the Court to hear challenges to its legality.

Equal Protection Clause

The Supreme Court decided several important equal protection cases during the first years of Harlan's career. In these cases, Harlan regularly voted in favor of civil rights—similar to his grandfather, the only dissenting justice in the infamous '' Plessy v. Ferguson'' case., Harlan J., dissenting He voted with the majority in '' Cooper v. Aaron'', compelling defiant officials inArkansas

Arkansas ( ) is a landlocked state in the South Central United States. It is bordered by Missouri to the north, Tennessee and Mississippi to the east, Louisiana to the south, and Texas and Oklahoma to the west. Its name is from the O ...

to desegregate public schools. He joined the opinion in '' Gomillion v. Lightfoot'', which declared that states could not redraw political boundaries in order to reduce the voting power of African-Americans. Moreover, he joined the unanimous decision in '' Loving v. Virginia'', which struck down state laws that banned interracial marriage.

Due Process Clause

Justice Harlan advocated a broad interpretation of the Fourteenth Amendment's Due Process Clause. He subscribed to the doctrine that the clause not only provided procedural guarantees, but also protected a wide range of fundamental rights, including those that were not specifically mentioned in the text of the Constitution. Wildenthal, 2000, p. 1463 (See substantive due process.) However, as JusticeByron White

Byron "Whizzer" Raymond White (June 8, 1917 April 15, 2002) was an American professional football player and jurist who served as an associate justice of the U.S. Supreme Court from 1962 until his retirement in 1993.

Born and raised in Colo ...

noted in his dissenting opinion in '' Moore v. East Cleveland'', "no one was more sensitive than Mr. Justice Harlan to any suggestion that his approach to the Due Process Clause would lead to judges 'roaming at large in the constitutional field'.", White, B., dissenting Under Harlan's approach, judges would be limited in the Due Process area by "respect for the teachings of history, solid recognition of the basic values that underlie our society, and wise appreciation of the great roles that the doctrines of federalism and separation of powers

Separation of powers refers to the division of a state's government into branches, each with separate, independent powers and responsibilities, so that the powers of one branch are not in conflict with those of the other branches. The typi ...

have played in establishing and preserving American freedoms"., Harlan, J., concurring in the judgment

Harlan set forth his interpretation in an often cited dissenting opinion to ''Poe v. Ullman

''Poe v. Ullman'', 367 U.S. 497 (1961), was a United States Supreme Court case that held that plaintiffs lacked standing to challenge a Connecticut law that banned the use of contraceptives and banned doctors from advising their use because the ...

'',, Harlan, J., dissenting which involved a challenge to a Connecticut

Connecticut () is the southernmost state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It is bordered by Rhode Island to the east, Massachusetts to the north, New York (state), New York to the west, and Long Island Sound to the ...

law banning the use of contraceptive

Birth control, also known as contraception, anticonception, and fertility control, is the use of methods or devices to prevent unwanted pregnancy. Birth control has been used since ancient times, but effective and safe methods of birth contr ...

s. The Supreme Court dismissed the case on technical grounds, holding that the case was not ripe for adjudication. Justice Harlan dissented from the dismissal, suggesting that the Court should have considered the merits of the case. Thereafter, he indicated his support for a broad view of the due process clause's reference to "liberty". He wrote, "This 'liberty' is not a series of isolated points pricked out in terms of the taking of property; the freedom of speech, press, and religion; the right to keep and bear arms

The right to keep and bear arms (often referred to as the right to bear arms) is a right for people to possess weapons (arms) for the preservation of life, liberty, and property. The purpose of gun rights is for self-defense, including securi ...

; the freedom from unreasonable searches and seizures

Search and seizure is a procedure used in many civil law and common law legal systems by which police or other authorities and their agents, who, suspecting that a crime has been committed, commence a search of a person's property and confis ...

; and so on. It is a rational continuum which, broadly speaking, includes a freedom from all substantial arbitrary impositions and purposeless restraints." He suggested that the due process clause encompassed a right to privacy, and concluded that a prohibition on contraception violated this right. Dripps, 2005, p. 144

The same law was challenged again in '' Griswold v. Connecticut''. This time, the Supreme Court agreed to consider the case, and concluded that the law violated the Constitution. However, the decision was based not on the due process clause, but on the argument that a right to privacy was found in the "penumbra

The umbra, penumbra and antumbra are three distinct parts of a shadow, created by any light source after impinging on an opaque object. Assuming no diffraction, for a collimated beam (such as a point source) of light, only the umbra is cast.

T ...

s" of other provisions of the Bill of Rights. Justice Harlan concurred in the result, but criticized the Court for relying on the Bill of Rights in reaching its decision. "The Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment stands," he wrote, "on its own bottom." The Supreme Court would later adopt Harlan's approach, relying on the due process clause rather than the penumbras of the Bill of Rights in right to privacy cases such as ''Roe v. Wade

''Roe v. Wade'', 410 U.S. 113 (1973),. was a landmark decision of the U.S. Supreme Court in which the Court ruled that the Constitution of the United States conferred the right to have an abortion. The decision struck down many federal and st ...

'' and ''Lawrence v. Texas

''Lawrence v. Texas'', 539 U.S. 558 (2003), is a landmark decision of the U.S. Supreme Court in which the Court ruled that most sanctions of criminal punishment for consensual, adult non- procreative sexual activity (commonly referred to as sod ...

''.

Harlan's interpretation of the Due Process Clause attracted the criticism of Justice Black, who rejected the idea that the Clause included a "substantive" component, considering this interpretation unjustifiably broad and historically unsound, one of the few issues in which Black was more conservative than Harlan. The Supreme Court has agreed with Harlan, and has continued to apply the doctrine of substantive due process in a wide variety of cases. Yarbrough, 1989, Chapter 3, The bill of rights and the states

Incorporation

Justice Harlan was strongly opposed to the theory that the Fourteenth Amendment "incorporated" the Bill of Rights—that is, made the provisions of the Bill of Rights applicable to the states. His opinion on the matter was opposite to that of his grandfather, who supported the full incorporation of the Bill of Rights. Wildenthal, 2000 When it was originally ratified, the Bill of Rights was binding only upon the federal government, as the Supreme Court ruled in the 1833 case ''Barron v. Baltimore

''Barron v. Baltimore'', 32 U.S. (7 Pet.) 243 (1833), is a landmark United States Supreme Court case in 1833, which helped define the concept of federalism in US constitutional law. The Court ruled that the Bill of Rights did not apply to the stat ...

''. Some jurists argued that the Fourteenth Amendment made the entirety of the Bill of Rights binding upon the states as well. Harlan, however, rejected this doctrine, which he called "historically unfounded" in his ''Griswold'' concurrence.

Instead, Justice Harlan believed that the Fourteenth Amendment's due process clause only protected "fundamental" rights. Thus, if a guarantee of the Bill of Rights was "fundamental" or "implicit in the concept of ordered liberty," Harlan agreed that it applied to the states as well as the federal government. Thus, for example, Harlan believed that the First Amendment

First or 1st is the ordinal form of the number one (#1).

First or 1st may also refer to:

*World record, specifically the first instance of a particular achievement

Arts and media Music

* 1$T, American rapper, singer-songwriter, DJ, and reco ...

's free speech

Freedom of speech is a principle that supports the freedom of an individual or a community to articulate their opinions and ideas without fear of retaliation, censorship, or legal sanction. The right to freedom of expression has been recog ...

clause applied to the states, but that the Fifth Amendment's self-incrimination clause did not.

Harlan's approach was largely similar to that of Justices Benjamin Cardozo and Felix Frankfurter. It drew criticism from Justice Black, a proponent of the total incorporation theory. Black claimed that the process of identifying some rights as more "fundamental" than others was largely arbitrary, and depended on each Justice's personal opinions.

The Supreme Court has eventually adopted some elements of Harlan's approach, holding that only some Bill of Rights guarantees were applicable against the states—the doctrine known as selective incorporation. However, under Chief Justice Earl Warren during the 1960s, an increasing number of rights were deemed sufficiently fundamental for incorporation (Harlan regularly dissented from these rulings). Hence, the majority of provisions from the Bill of Rights have been extended to the states; the exceptions are the Third Amendment, the grand jury clause of the Fifth Amendment, the Seventh Amendment, the Ninth Amendment, and the Tenth Amendment. Thus, although the Supreme Court has agreed with Harlan's general reasoning, the end result of its jurisprudence is very different from what Harlan advocated. Cortner, 1985

First Amendment

Justice Harlan supported many of the Warren Court's landmark decisions relating to theseparation of church and state

The separation of church and state is a philosophical and jurisprudential concept for defining political distance in the relationship between religious organizations and the state. Conceptually, the term refers to the creation of a secular s ...

. For instance, he voted in favor of the Court's ruling that the states could not use religious tests as qualifications for public office in ''Torcaso v. Watkins

''Torcaso v. Watkins'', 367 U.S. 488 (1961), was a United States Supreme Court case in which the court reaffirmed that the United States Constitution prohibits states and the federal government from requiring any kind of religious test for publ ...

''. He joined in '' Engel v. Vitale'', which declared that it was unconstitutional for states to require the recitation of official prayers in public schools. In '' Epperson v. Arkansas'',, Harlan, J., concurring he similarly voted to strike down an Arkansas law banning the teaching of evolution

Evolution is change in the heritable characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. These characteristics are the expressions of genes, which are passed on from parent to offspring during reproduction. Variation ...

.

In many cases, Harlan took a fairly broad view of First Amendment rights such as the freedom of speech and of the press, although he thought that the First Amendment applied directly only to the federal government. O'Neil, 2001 According to Harlan the freedom of speech was among the "fundamental principles of liberty and justice" and therefore applicable also to states, but less stringently than to the national government. Moreover, Justice Harlan believed that federal laws censoring "obscene" publications violated the free speech clause. Thus, he dissented from '' Roth v. United States'',, Harlan, J., concurring in the result in No. 61, and dissenting in No. 582 in which the Supreme Court upheld the validity of a federal obscenity law. At the same time, Harlan did not believe that the Constitution prevented the states from censoring obscenity. O'Neil, 2001, pp. 63–64 He explained in his ''Roth'' dissent:

The danger is perhaps not great if the people of one State, through their legislature, decide that '' Lady Chatterley's Lover'' goes so far beyond the acceptable standards of candor that it will be deemed offensive and non-sellable, for the State next door is still free to make its own choice. At least we do not have one uniform standard. But the dangers to free thought and expression are truly great if the Federal Government imposes a blanket ban over the Nation on such a book. ... The fact that the people of one State cannot read some of the works ofHarlan concurred in '' New York Times Co. v. Sullivan'', which required public officials suing newspapers forD. H. Lawrence David Herbert Lawrence (11 September 1885 – 2 March 1930) was an English writer, novelist, poet and essayist. His works reflect on modernity, industrialization, sexuality, emotional health, vitality, spontaneity and instinct. His best-k ...seems to me, if not wise or desirable, at least acceptable. But that no person in the United States should be allowed to do so seems to me to be intolerable, and violative of both the letter and spirit of the First Amendment.

libel

Defamation is the act of communicating to a third party false statements about a person, place or thing that results in damage to its reputation. It can be spoken (slander) or written (libel). It constitutes a tort or a crime. The legal defi ...

to prove that the publisher had acted with "actual malice

Actual malice in United States law is a legal requirement imposed upon public officials or public figures when they file suit for libel (defamatory printed communications). Compared to other individuals who are less well known to the general pu ...

." This stringent standard made it much more difficult for public officials to win libel cases. He did not, however, go as far as Justices Hugo Black and William O. Douglas, who suggested that all libel laws were unconstitutional. In '' Street v. New York'', Harlan wrote the opinion of the court, ruling that the government could not punish an individual for insulting the American flag. In 1969 he noted that the Supreme Court had consistently "rejected all manner of prior restraint on publication." Abrams, 2005, pp. 15–16

When Harlan was a Circuit Judge in 1955, he authorized the decision upholding the conviction of leaders of the Communist Party USA (including Elizabeth Gurley Flynn) under the Smith Act. The ruling was based on the previous Supreme Court's decisions, by which the Court of Appeals was bound. Later, when he was a Supreme Court justice, Harlan, however, wrote an opinion overturning the conviction of Communist Party activists as unconstitutional in the case of ''Yates v. United States

''Yates v. United States'', 354 U.S. 298 (1957), was a case decided by the Supreme Court of the United States that held that the First Amendment protected radical and reactionary speech, unless it posed a "clear and present danger."

Background

F ...

''. Another such case was '' Watkins v. United States''.

Harlan penned the majority opinion in '' Cohen v. California'', holding that wearing a jacket emblazoned with the words "Fuck the Draft" was speech protected by the First Amendment. His opinion was later described by constitutional law expert Professor Yale Kamisar as one of the greatest ever written on freedom of expression. In the ''Cohen'' opinion, Harlan famously wrote "one man's vulgarity is another's lyric," a quote that was later denounced by Robert Bork as " moral relativism".

Justice Harlan is credited for establishing that the First Amendment protects the freedom of association. In ''NAACP v. Alabama

''National Association for the Advancement of Colored People v. Alabama'', 357 U.S. 449 (1958), was a landmark decision of the US Supreme Court. Alabama sought to prevent the NAACP from conducting further business in the state. After the circuit ...

'', Justice Harlan delivered the opinion of the court, invalidating an Alabama law that required the NAACP to disclose membership lists. However he did not believe that individuals were entitled to exercise their First Amendment rights wherever they pleased. He joined in ''Adderley v. Florida'', which controversially upheld a trespassing conviction for protesters who demonstrated on government property. He dissented from ''Brown v. Louisiana

''Brown v. Louisiana'', 383 U.S. 131 (1966), was a United States Supreme Court case based on the First Amendment in the U.S. Constitution. It held that protesters have a First and Fourteenth Amendment right to engage in a peaceful sit-in at a pu ...

'',, Mr. Justice Black, with whom Mr. Justice Clark, Mr. Justice Harlan, and Mr. Justice Stewart join dissenting in which the Court held that protesters were entitled to engage in a sit-in at a public library. Likewise, he disagreed with '' Tinker v. Des Moines'',, Harlan, J., dissenting in which the Supreme Court ruled that students had the right to wear armbands (as a form of protest) in public schools.

Criminal procedure

During the 1960s the Warren Court made a series of rulings expanding the rights of criminaldefendant

In court proceedings, a defendant is a person or object who is the party either accused of committing a crime in criminal prosecution or against whom some type of civil relief is being sought in a civil case.

Terminology varies from one jurisd ...

s. In some instances, Justice Harlan concurred in the result,, Harlan, J., concurring while in many other cases he found himself in dissent. Harlan was usually joined by the other moderate members of the Court: Justices Potter Stewart

Potter Stewart (January 23, 1915 – December 7, 1985) was an American lawyer and judge who served as an Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court from 1958 to 1981. During his tenure, he made major contributions to, among other areas ...

, Tom Clark, and Byron White

Byron "Whizzer" Raymond White (June 8, 1917 April 15, 2002) was an American professional football player and jurist who served as an associate justice of the U.S. Supreme Court from 1962 until his retirement in 1993.

Born and raised in Colo ...

. Vasicko, 1980

Most notably, Harlan dissented from Supreme Court rulings restricting interrogation techniques used by law enforcement officers. For example, he dissented from the Court's holding in '' Escobedo v. Illinois'',, Harlan, J., dissenting that the police could not refuse to honor a suspect's request to consult with his lawyer during an interrogation. Harlan called the rule "ill-conceived" and suggested that it "unjustifiably fetters perfectly legitimate methods of criminal law enforcement." He disagreed with ''Miranda v. Arizona

''Miranda v. Arizona'', 384 U.S. 436 (1966), was a landmark decision of the U.S. Supreme Court in which the Court ruled that the Fifth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution restricts prosecutors from using a person's statements made in response to ...

'',, Harlan, J., dissenting which required law enforcement officials to warn a suspect of his rights before questioning him (see Miranda warning). He closed his dissenting opinion with a quotation from his predecessor, Justice Robert H. Jackson

Robert Houghwout Jackson (February 13, 1892 – October 9, 1954) was an American lawyer, jurist, and politician who served as an Associate Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court from 1941 until his death in 1954. He had previously served as Unit ...

: "This Court is forever adding new stories to the temples of constitutional law, and the temples have a way of collapsing when one story too many is added."

In ''Gideon v. Wainwright

''Gideon v. Wainwright'', 372 U.S. 335 (1963), was a landmark U.S. Supreme Court decision in which the Court ruled that the Sixth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution requires U.S. states to provide attorneys to criminal defendants who are unable to ...

'', Justice Harlan agreed that the Constitution required states to provide attorneys for defendants who could not afford their own counsel. However, he believed that this requirement applied only at trial, and not on appeal; thus, he dissented from '' Douglas v. California''., Harlan, J., dissenting

Harlan wrote the majority opinion in '' Leary v. United States''—a case that declared the Marijuana Tax Act

The Marihuana Tax Act of 1937, , was a United States Act that placed a tax on the sale of cannabis. The H.R. 6385 act was drafted by Harry Anslinger and introduced by Rep. Robert L. Doughton of North Carolina, on April 14, 1937. The Seventy-fift ...

unconstitutional based on the Fifth Amendment protection against self-incrimination

In criminal law, self-incrimination is the act of exposing oneself generally, by making a statement, "to an accusation or charge of crime; to involve oneself or another ersonin a criminal prosecution or the danger thereof". (Self-incriminati ...

.

Justice Harlan's concurrence in ''Katz v. United States

''Katz v. United States'', 389 U.S. 347 (1967), was a landmark decision of the U.S. Supreme Court in which the Court redefined what constitutes a "search" or "seizure" with regard to the protections of the Fourth Amendment to the U.S. Constituti ...

'' set forth the test for determining whether government conduct constituted a search

Searching or search may refer to:

Computing technology

* Search algorithm, including keyword search

** :Search algorithms

* Search and optimization for problem solving in artificial intelligence

* Search engine technology, software for find ...

. In this case the Supreme Court held that eavesdropping

Eavesdropping is the act of secretly or stealthily listening to the private conversation or communications of others without their consent in order to gather information.

Etymology

The verb ''eavesdrop'' is a back-formation from the noun ''eaves ...

on the petitioner's telephone conversation constituted a search in the meaning of the Fourth Amendment and thus required a warrant. According to Justice Harlan, there is a two-part requirement for a search: (1) that the individual have a subjective expectation of privacy; and (2) that the individual's expectation of privacy is "one that society is prepared to recognize as 'reasonable.'"

Voting rights

Justice Harlan rejected the theory that the Constitution enshrined the so-called " one man, one vote" principle, or the principle that legislative districts must be roughly equal in population.Hickok Hickok may refer to:

People

* Eugene W. Hickok (born 1951), American education advocate

* Laurens Perseus Hickok (1798–1888), American philosopher

* Lorena Hickok (1893–1968), American journalist

* Wild Bill Hickok (1837–1876), American scou ...

, 1991, pp. 5–7 In this regard, he shared the views of Justice Felix Frankfurter, who in '' Colegrove v. Green'' admonished the courts to stay out of the "political thicket" of reapportionment. The Supreme Court, however, disagreed with Harlan in a series of rulings during the 1960s. The first case in this line of rulings was '' Baker v. Carr''., Harlan, J., dissenting The Court ruled that the courts had jurisdiction

Jurisdiction (from Latin 'law' + 'declaration') is the legal term for the legal authority granted to a legal entity to enact justice. In federations like the United States, areas of jurisdiction apply to local, state, and federal levels.

J ...

over malapportionment issues and therefore were entitled to review the validity of district boundaries. Harlan, however, dissented, on the grounds that the plaintiffs failed to demonstrate that malapportionment violated their individual rights.

Then, in '' Wesberry v. Sanders'',, Harlan, J., dissenting the Supreme Court, relying on the Constitution's requirement that the United States House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives, often referred to as the House of Representatives, the U.S. House, or simply the House, is the lower chamber of the United States Congress, with the Senate being the upper chamber. Together they ...

be elected "by the People of the several States," ruled that congressional district

Congressional districts, also known as electoral districts and legislative districts, electorates, or wards in other nations, are divisions of a larger administrative region that represent the population of a region in the larger congressional bod ...

s in any particular state must be approximately equal in population. Harlan vigorously dissented, writing, "I had not expected to witness the day when the Supreme Court of the United States would render a decision which casts grave doubt on the constitutionality of the composition of the House of Representatives. It is not an exaggeration to say that such is the effect of today's decision." He proceeded to argue that the Court's decision was inconsistent with both the history and text of the Constitution; moreover, he claimed that only Congress, not the judiciary, had the power to require congressional districts with equal populations.

Harlan was the sole dissenter in '' Reynolds v. Sims'', in which the Court relied on the Equal Protection Clause to extend the one man, one vote principle to state legislative districts. He analyzed the language and history of the Fourteenth Amendment, and concluded that the Equal Protection Clause was never intended to encompass voting rights. Because the Fifteenth Amendment would have been superfluous if the Fourteenth Amendment (the basis of the reapportionment decisions) had conferred a general right to vote

Suffrage, political franchise, or simply franchise, is the right to vote in public, political elections and referendums (although the term is sometimes used for any right to vote). In some languages, and occasionally in English, the right to v ...

, he claimed that the Constitution did not require states to adhere to the one man, one vote principle, and that the Court was merely imposing its own political theories on the nation. He suggested, in addition, that the problem of malapportionment was one that should be solved by the political process, and not by litigation. He wrote:

This Court, limited in function in accordance with that premise, does not serve its high purpose when it exceeds its authority, even to satisfy justified impatience with the slow workings of the political process. For when, in the name of constitutional interpretation, the Court adds something to the Constitution that was deliberately excluded from it, the Court, in reality, substitutes its view of what should be so for the amending process.For similar reasons, Harlan dissented from ''Carrington v. Rash'',, Harlan, J., dissenting in which the Court held that voter qualifications were subject to scrutiny under the equal protection clause. He claimed in his dissent, "the Court totally ignores, as it did in last Term's reapportionment cases ... all the history of the Fourteenth Amendment and the course of judicial decisions which together plainly show that the Equal Protection Clause was not intended to touch state electoral matters." Similarly, Justice Harlan disagreed with the Court's ruling in ''

Harper v. Virginia Board of Elections

''Harper v. Virginia State Board of Elections'', 383 U.S. 663 (1966), was a case in which the U.S. Supreme Court found that Virginia's poll tax was unconstitutional under the equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment. In the late 19th and ear ...

'', invalidating the use of the poll tax as a qualification to vote.

Retirement and death

John M. Harlan's health began to deteriorate towards the end of his career. His eyesight began to fail during the late 1960s. Dean, 2001 To cover this, he would bring materials to within an inch of his eyes, and have clerks and his wife read to him (once when the Court took an obscenity case, a chagrined Harlan had his wife read him '' Lady Chatterley's Lover''). Gravely ill, he retired from the Supreme Court on September 23, 1971. Harlan died fromspinal cancer

Spinal tumors are neoplasms located in either the vertebral column or the spinal cord. There are three main types of spinal tumors classified based on their location: extradural and intradural (intradural-intramedullary and intradural-extramedulla ...

three months later, on December 29, 1971. He was buried at the Emmanuel Church Cemetery in Weston, Connecticut. Supreme Court Historical Society

The Supreme Court Historical Society (SCHS) is a Washington, D.C.-based private, nonprofit organization dedicated to preserving and communicating the history of the U.S. Supreme Court. The Society was founded in 1974 by U.S. Chief Justice Warren E ...

at Internet Archive

The Internet Archive is an American digital library with the stated mission of "universal access to all knowledge". It provides free public access to collections of digitized materials, including websites, software applications/games, music, ...

. President Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913April 22, 1994) was the 37th president of the United States, serving from 1969 to 1974. A member of the Republican Party, he previously served as a representative and senator from California and was ...

considered nominating Mildred Lillie

Mildred Loree Lillie (January 25, 1915 – October 27, 2002) was an American jurist. She served as a judge for 55 years in the state of California with a career that spanned from 1947 until her death in 2002. In 1958, she became the second woman t ...

, a California appeals court judge, to fill the vacant seat; Lillie would have been the first female nominee to the Supreme Court. However, Nixon decided against Lillie's nomination after the American Bar Association

The American Bar Association (ABA) is a voluntary bar association of lawyers and law students, which is not specific to any jurisdiction in the United States. Founded in 1878, the ABA's most important stated activities are the setting of aca ...

found Lillie to be unqualified. Thereafter, Nixon nominated William Rehnquist (a future Chief Justice), who was confirmed by the Senate.

Despite his many dissents, Harlan has been described as one of the most influential Supreme Court justices of the twentieth century. Yarbrough, 1992 He was elected a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences

The American Academy of Arts and Sciences (abbreviation: AAA&S) is one of the oldest learned societies in the United States. It was founded in 1780 during the American Revolution by John Adams, John Hancock, James Bowdoin, Andrew Oliver, a ...

in 1960. Harlan's extensive professional and Supreme Court papers (343 cubic feet) were donated to Princeton University

Princeton University is a private research university in Princeton, New Jersey. Founded in 1746 in Elizabeth as the College of New Jersey, Princeton is the fourth-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and one of the ...

, where they are housed at the Seeley G. Mudd Manuscript Library and open to research. Other papers repose at several other libraries. Ethel Harlan, his wife, outlived him by only a few months and died on June 12, 1972. She suffered from Alzheimer's disease for the last seven years of her life.

See also

* List of justices of the Supreme Court of the United States *List of United States Supreme Court justices by time in office

A total of 116 people have served on the Supreme Court of the United States, the highest judicial body in the United States, since it was established in 1789. Supreme Court justices have life tenure, and so they serve until they die, resign, re ...

*List of law clerks of the Supreme Court of the United States (Seat 9)

Law clerks have assisted the justices of the United States Supreme Court in various capacities since the first one was hired by Justice Horace Gray in 1882. Each justice is permitted to have between three and four law clerks per Court term. M ...

* List of United States Supreme Court cases by the Warren Court

*List of United States Supreme Court cases by the Burger Court

This is a partial chronological list of cases decided by the United States Supreme Court during the Burger Court

The Burger Court was the period in the history of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1969 to 1986, when Warren Burger s ...

*'' Clay v. United States'' (1971)

*'' Muhammad Ali's Greatest Fight'' (2013 television film)

Notes

References

* * * * * * * * * * * (Harlan arranged for Mayer to write this book about his mentor Emory Buckner and wrote the book's Introduction.) * * * * * * *Further reading

* * * * * * * *External links

* *John M. Harlan Papers at the Seeley G. Mudd Manuscript Library, Princeton University

*

Public Broadcasting Service. *

Supreme Court Historical Society

The Supreme Court Historical Society (SCHS) is a Washington, D.C.-based private, nonprofit organization dedicated to preserving and communicating the history of the U.S. Supreme Court. The Society was founded in 1974 by U.S. Chief Justice Warren E ...

"John Marshall Harlan II."

''Booknotes'' interview with Tinsley Yarbrough on ''John Marshall Harlan: Great Dissenter of the Warren Court'', April 26, 1992.

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Harlan, John Marshall II 1899 births 1971 deaths 20th-century American judges Alumni of Balliol College, Oxford United States Army personnel of World War II American Presbyterians American people of Scotch-Irish descent American Rhodes Scholars Appleby College alumni Assistant United States Attorneys Deaths from cancer in Washington, D.C. Neurological disease deaths in Washington, D.C. Deaths from spinal cancer Fellows of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences Judges of the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit Latin School of Chicago alumni Lawyers from Chicago Military personnel from Illinois New York Law School alumni New York (state) Republicans People from Weston, Connecticut Princeton University alumni Recipients of the Croix de guerre (Belgium) Recipients of the Croix de Guerre 1939–1945 (France) Recipients of the Legion of Merit United States Army officers United States court of appeals judges appointed by Dwight D. Eisenhower Justices of the Supreme Court of the United States Upper Canada College alumni Harlan family Conservatism in the United States