John Locke on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

John Locke (; 29 August 1632 – 28 October 1704) was an English philosopher and physician, widely regarded as one of the most influential of Enlightenment thinkers and commonly known as the "father of

In the late 17th and early 18th centuries, Locke's '' Two Treatises'' were rarely cited. Historian Julian Hoppit said of the book, "except among some Whigs, even as a contribution to the intense debate of the 1690s it made little impression and was generally ignored until 1703 (though in Oxford in 1695 it was reported to have made 'a great noise')." John Kenyon, in his study of British political debate from 1689 to 1720, has remarked that Locke's theories were "mentioned so rarely in the early stages of the loriousRevolution, up to 1692, and even less thereafter, unless it was to heap abuse on them" and that "no one, including most Whigs, asready for the idea of a notional or abstract contract of the kind adumbrated by Locke". In contrast, Kenyon adds that

In the late 17th and early 18th centuries, Locke's '' Two Treatises'' were rarely cited. Historian Julian Hoppit said of the book, "except among some Whigs, even as a contribution to the intense debate of the 1690s it made little impression and was generally ignored until 1703 (though in Oxford in 1695 it was reported to have made 'a great noise')." John Kenyon, in his study of British political debate from 1689 to 1720, has remarked that Locke's theories were "mentioned so rarely in the early stages of the loriousRevolution, up to 1692, and even less thereafter, unless it was to heap abuse on them" and that "no one, including most Whigs, asready for the idea of a notional or abstract contract of the kind adumbrated by Locke". In contrast, Kenyon adds that

Writing his '' Letters Concerning Toleration'' (1689–1692) in the aftermath of the

Writing his '' Letters Concerning Toleration'' (1689–1692) in the aftermath of the

Second Treatise of Government

' (10th ed.), digitized by D. Gowan.

liberalism

Liberalism is a political and moral philosophy based on the rights of the individual, liberty, consent of the governed, political equality and equality before the law."political rationalism, hostility to autocracy, cultural distaste for c ...

". Considered one of the first of the British empiricists

In philosophy, empiricism is an epistemological theory that holds that knowledge or justification comes only or primarily from sensory experience. It is one of several views within epistemology, along with rationalism and skepticism. Empir ...

, following the tradition of Francis Bacon

Francis Bacon, 1st Viscount St Alban (; 22 January 1561 – 9 April 1626), also known as Lord Verulam, was an English philosopher and statesman who served as Attorney General and Lord Chancellor of England. Bacon led the advancement of both ...

, Locke is equally important to social contract

In moral and political philosophy

Political philosophy or political theory is the philosophical study of government, addressing questions about the nature, scope, and legitimacy of public agents and institutions and the relationships betw ...

theory. His work greatly affected the development of epistemology

Epistemology (; ), or the theory of knowledge, is the branch of philosophy concerned with knowledge. Epistemology is considered a major subfield of philosophy, along with other major subfields such as ethics, logic, and metaphysics.

Episte ...

and political philosophy

Political philosophy or political theory is the philosophical study of government, addressing questions about the nature, scope, and legitimacy of public agents and institutions and the relationships between them. Its topics include politics, l ...

. His writings influenced Voltaire

François-Marie Arouet (; 21 November 169430 May 1778) was a French Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment writer, historian, and philosopher. Known by his ''Pen name, nom de plume'' M. de Voltaire (; also ; ), he was famous for his wit, and his ...

and Jean-Jacques Rousseau

Jean-Jacques Rousseau (, ; 28 June 1712 – 2 July 1778) was a Genevan philosopher, writer, and composer. His political philosophy influenced the progress of the Age of Enlightenment throughout Europe, as well as aspects of the French Revolu ...

, and many Scottish Enlightenment

The Scottish Enlightenment ( sco, Scots Enlichtenment, gd, Soillseachadh na h-Alba) was the period in 18th- and early-19th-century Scotland characterised by an outpouring of intellectual and scientific accomplishments. By the eighteenth century ...

thinkers, as well as the American Revolution

The American Revolution was an ideological and political revolution that occurred in British America between 1765 and 1791. The Americans in the Thirteen Colonies formed independent states that defeated the British in the American Revolut ...

aries. His contributions to classical republicanism

Classical republicanism, also known as civic republicanism or civic humanism, is a form of republicanism developed in the Renaissance inspired by the governmental forms and writings of classical antiquity, especially such classical writers as Ar ...

and liberal theory

Liberalism is a political and moral philosophy based on the rights of the individual, liberty, consent of the governed, political equality and equality before the law."political rationalism, hostility to autocracy, cultural distaste for c ...

are reflected in the United States Declaration of Independence

The United States Declaration of Independence, formally The unanimous Declaration of the thirteen States of America, is the pronouncement and founding document adopted by the Second Continental Congress meeting at Pennsylvania State House ...

. Internationally, Locke’s political-legal principles continue to have a profound influence on the theory and practice of limited representative government and the protection of basic rights and freedoms under the rule of law.

Locke's theory of mind

In psychology, theory of mind refers to the capacity to understand other people by ascribing mental states to them (that is, surmising what is happening in their mind). This includes the knowledge that others' mental states may be different fro ...

is often cited as the origin of modern conceptions of ''identity'' and the ''self'', figuring prominently in the work of later philosophers such as Jean-Jacques Rousseau, David Hume

David Hume (; born David Home; 7 May 1711 NS (26 April 1711 OS) – 25 August 1776) Cranston, Maurice, and Thomas Edmund Jessop. 2020 999br>David Hume" ''Encyclopædia Britannica''. Retrieved 18 May 2020. was a Scottish Enlightenment philo ...

, and Immanuel Kant

Immanuel Kant (, , ; 22 April 1724 – 12 February 1804) was a German philosopher and one of the central Enlightenment thinkers. Born in Königsberg, Kant's comprehensive and systematic works in epistemology, metaphysics, ethics, and ...

. Locke was the first to define the ''self'' through a continuity of consciousness

Consciousness, at its simplest, is sentience and awareness of internal and external existence. However, the lack of definitions has led to millennia of analyses, explanations and debates by philosophers, theologians, linguisticians, and scien ...

.

He postulated that, at birth, the mind

The mind is the set of faculties responsible for all mental phenomena. Often the term is also identified with the phenomena themselves. These faculties include thought, imagination, memory, will, and sensation. They are responsible for various m ...

was a blank slate, or ''tabula rasa

''Tabula rasa'' (; "blank slate") is the theory that individuals are born without built-in mental content, and therefore all knowledge comes from experience or perception. Epistemological proponents of ''tabula rasa'' disagree with the doctri ...

''. Contrary to Cartesian philosophy based on pre-existing concepts, he maintained that we are born without innate ideas

Innatism is a philosophical and epistemological doctrine that the mind is born with ideas, knowledge, and beliefs. Therefore, the mind is not a ''tabula rasa'' (blank slate) at birth, which contrasts with the views of early empiricists such as J ...

, and that knowledge

Knowledge can be defined as awareness of facts or as practical skills, and may also refer to familiarity with objects or situations. Knowledge of facts, also called propositional knowledge, is often defined as true belief that is distinc ...

is instead determined only by experience derived from sense

A sense is a biological system used by an organism for sensation, the process of gathering information about the world through the detection of Stimulus (physiology), stimuli. (For example, in the human body, the brain which is part of the cen ...

perception

Perception () is the organization, identification, and interpretation of sensory information in order to represent and understand the presented information or environment. All perception involves signals that go through the nervous system ...

, a concept now known as ''empiricism

In philosophy, empiricism is an epistemological theory that holds that knowledge or justification comes only or primarily from sensory experience. It is one of several views within epistemology, along with rationalism and skepticism. Empir ...

''.

Demonstrating the ideology of science in his observations, whereby something must be capable of being tested repeatedly and that nothing is exempt from being disproved, Locke stated that "whatever I write, as soon as I discover it not to be true, my hand shall be the forwardest to throw it into the fire". Such is one example of Locke's belief in empiricism.

Early life

Locke was born on 29 August 1632, in a small thatched cottage by the church in Wrington, Somerset, about 12 miles fromBristol

Bristol () is a city, ceremonial county and unitary authority in England. Situated on the River Avon, it is bordered by the ceremonial counties of Gloucestershire to the north and Somerset to the south. Bristol is the most populous city in ...

. He was baptised

Baptism (from grc-x-koine, βάπτισμα, váptisma) is a form of ritual purification—a characteristic of many religions throughout time and geography. In Christianity, it is a Christian sacrament of initiation and adoption, almost inv ...

the same day, as both of his parents were Puritans

The Puritans were English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries who sought to purify the Church of England of Roman Catholic practices, maintaining that the Church of England had not been fully reformed and should become more Protestant. P ...

. Locke's father, also called John, was an attorney who served as clerk to the Justices of the Peace

A justice of the peace (JP) is a judicial officer of a lower or ''puisne'' court, elected or appointed by means of a commission ( letters patent) to keep the peace. In past centuries the term commissioner of the peace was often used with the sa ...

in Chew Magna

Chew Magna is a village and civil parish within the Chew Valley in the Unitary authorities of England, unitary authority of Bath and North East Somerset, in the Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county of Somerset, England. The parish ...

and as a captain of cavalry

Historically, cavalry (from the French word ''cavalerie'', itself derived from "cheval" meaning "horse") are soldiers or warriors who fight mounted on horseback. Cavalry were the most mobile of the combat arms, operating as light cavalry ...

for the Parliamentarian forces during the early part of the English Civil War

The English Civil War (1642–1651) was a series of civil wars and political machinations between Parliamentarians (" Roundheads") and Royalists led by Charles I ("Cavaliers"), mainly over the manner of England's governance and issues of re ...

. His mother was Agnes Keene. Soon after Locke's birth, the family moved to the market town

A market town is a settlement most common in Europe that obtained by custom or royal charter, in the Middle Ages, a market right, which allowed it to host a regular market; this distinguished it from a village or city. In Britain, small rural ...

of Pensford

Pensford is the largest village in the civil parish of Publow in Somerset, England. It lies in the Chew Valley, approximately south of Bristol, west of Bath and north of Wells. It is on the A37 road from Bristol to Shepton Mallet.

Pensford ...

, about seven miles south of Bristol, where Locke grew up in a rural Tudor house in Belluton

Belluton is a village in Somerset, England. It is in the district of Bath and North East Somerset and is located due south of the city of Bristol and due west of the city of Bath. The eastern end of the village is defined by the A37 road.

In so ...

.

In 1647, Locke was sent to the prestigious Westminster School

(God Gives the Increase)

, established = Earliest records date from the 14th century, refounded in 1560

, type = Public school Independent day and boarding school

, religion = Church of England

, head_label = Hea ...

in London under the sponsorship of Alexander Popham

Alexander Popham (1605 – 1669) of Littlecote, Wiltshire, was an English politician who sat in the House of Commons at various times between 1640 and 1669. He was patron of the philosopher John Locke.

Early life

Popham was born at Little ...

, a member of Parliament and John Sr.'s former commander. After completing studies there, he was admitted to Christ Church, Oxford

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the ...

, in the autumn of 1652 at the age of 20. The dean of the college at the time was John Owen, vice-chancellor of the university. Although a capable student, Locke was irritated by the undergraduate curriculum of the time. He found the works of modern philosophers, such as René Descartes

René Descartes ( or ; ; Latinized: Renatus Cartesius; 31 March 1596 – 11 February 1650) was a French philosopher, scientist, and mathematician, widely considered a seminal figure in the emergence of modern philosophy and science. Mathem ...

, more interesting than the classical material taught at the university. Through his friend Richard Lower, whom he knew from the Westminster School, Locke was introduced to medicine and the experimental philosophy

Experimental philosophy is an emerging field of philosophical inquiry Edmonds, David and Warburton, NigelPhilosophy’s great experiment, ''Prospect'', March 1, 2009 that makes use of empirical data—often gathered through surveys which probe ...

being pursued at other universities and in the Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

, of which he eventually became a member.

Locke was awarded a bachelor's degree

A bachelor's degree (from Middle Latin ''baccalaureus'') or baccalaureate (from Modern Latin ''baccalaureatus'') is an undergraduate academic degree awarded by colleges and universities upon completion of a course of study lasting three to six ...

in February 1656 and a master's degree

A master's degree (from Latin ) is an academic degree awarded by universities or colleges upon completion of a course of study demonstrating mastery or a high-order overview of a specific field of study or area of professional practice.

in June 1658. He obtained a bachelor of medicine

Bachelor of Medicine, Bachelor of Surgery ( la, Medicinae Baccalaureus, Baccalaureus Chirurgiae; abbreviated most commonly MBBS), is the primary medical degree awarded by medical schools in countries that follow the tradition of the United Ki ...

in February 1675, having studied the subject extensively during his time at Oxford and, in addition to Lower, worked with such noted scientists and thinkers as Robert Boyle

Robert Boyle (; 25 January 1627 – 31 December 1691) was an Anglo-Irish natural philosopher, chemist, physicist, alchemist and inventor. Boyle is largely regarded today as the first modern chemist, and therefore one of the founders of ...

, Thomas Willis

Thomas Willis FRS (27 January 1621 – 11 November 1675) was an English doctor who played an important part in the history of anatomy, neurology and psychiatry, and was a founding member of the Royal Society.

Life

Willis was born on his pare ...

and Robert Hooke

Robert Hooke FRS (; 18 July 16353 March 1703) was an English polymath active as a scientist, natural philosopher and architect, who is credited to be one of two scientists to discover microorganisms in 1665 using a compound microscope that ...

. In 1666, he met Anthony Ashley Cooper, Lord Ashley, who had come to Oxford seeking treatment for a liver

The liver is a major Organ (anatomy), organ only found in vertebrates which performs many essential biological functions such as detoxification of the organism, and the Protein biosynthesis, synthesis of proteins and biochemicals necessary for ...

infection. Ashley was impressed with Locke and persuaded him to become part of his retinue.

Career

Work

Locke had been looking for a career and in 1667 moved into Ashley's home at Exeter House in London, to serve as his personal physician. In London, Locke resumed his medical studies under the tutelage ofThomas Sydenham

Thomas Sydenham (10 September 1624 – 29 December 1689) was an English physician. He was the author of ''Observationes Medicae'' which became a standard textbook of medicine for two centuries so that he became known as 'The English Hippocrate ...

. Sydenham had a major effect on Locke's natural philosophical thinkingan effect that would become evident in ''An Essay Concerning Human Understanding

''An Essay Concerning Human Understanding'' is a work by John Locke concerning the foundation of human knowledge and understanding. It first appeared in 1689 (although dated 1690) with the printed title ''An Essay Concerning Humane Understan ...

.''

Locke's medical knowledge was put to the test when Ashley's liver infection became life-threatening. Locke coordinated the advice of several physicians and was probably instrumental in persuading Ashley to undergo surgery (then life-threatening in itself) to remove the cyst. Ashley survived and prospered, crediting Locke with saving his life.

During this time, Locke served as Secretary of the Board of Trade and Plantations and Secretary to the Lords Proprietor

A lord proprietor is a person granted a royal charter for the establishment and government of an English colony in the 17th century. The plural of the term is "lords proprietors" or "lords proprietary".

Origin

In the beginning of the European ...

s of Carolina, which helped to shape his ideas on international trade and economics.

Ashley, as a founder of the Whig movement, exerted great influence on Locke's political ideas. Locke became involved in politics when Ashley became Lord Chancellor

The lord chancellor, formally the lord high chancellor of Great Britain, is the highest-ranking traditional minister among the Great Officers of State in Scotland and England in the United Kingdom, nominally outranking the prime minister. The ...

in 1672 (Ashley being created 1st Earl of Shaftesbury in 1673). Following Shaftesbury's fall from favour in 1675, Locke spent some time travelling across France as a tutor and medical attendant to Caleb Banks

Caleb Banks (18 September 1659 – 13 September 1696) was an English politician who sat in the House of Commons between 1685 and 1696.

Biography

Banks was the son of Sir John Banks, 1st Baronet and his wife Elizabeth Dethick, daughter of Sir Joh ...

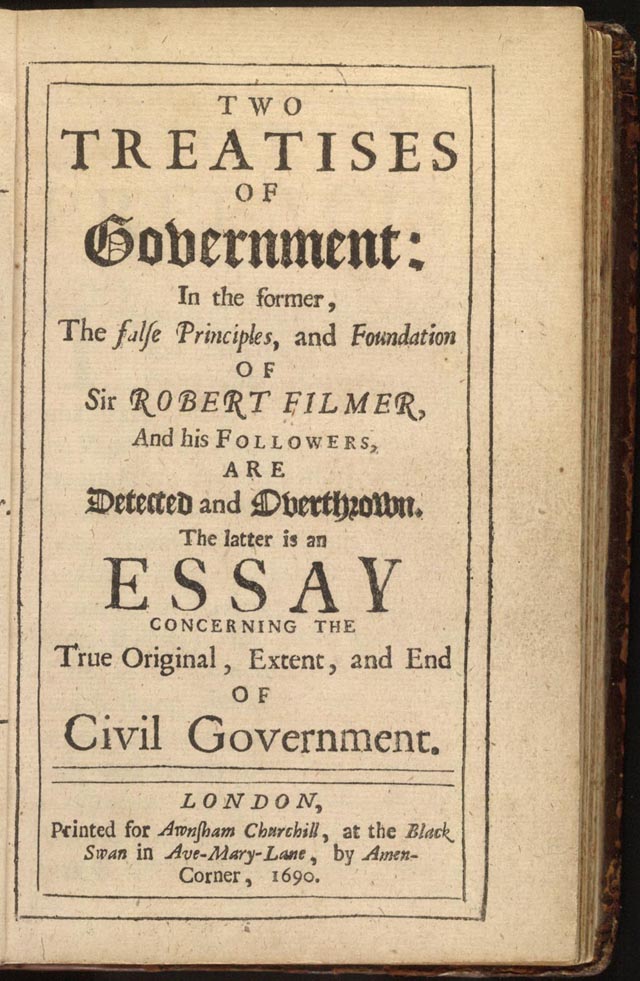

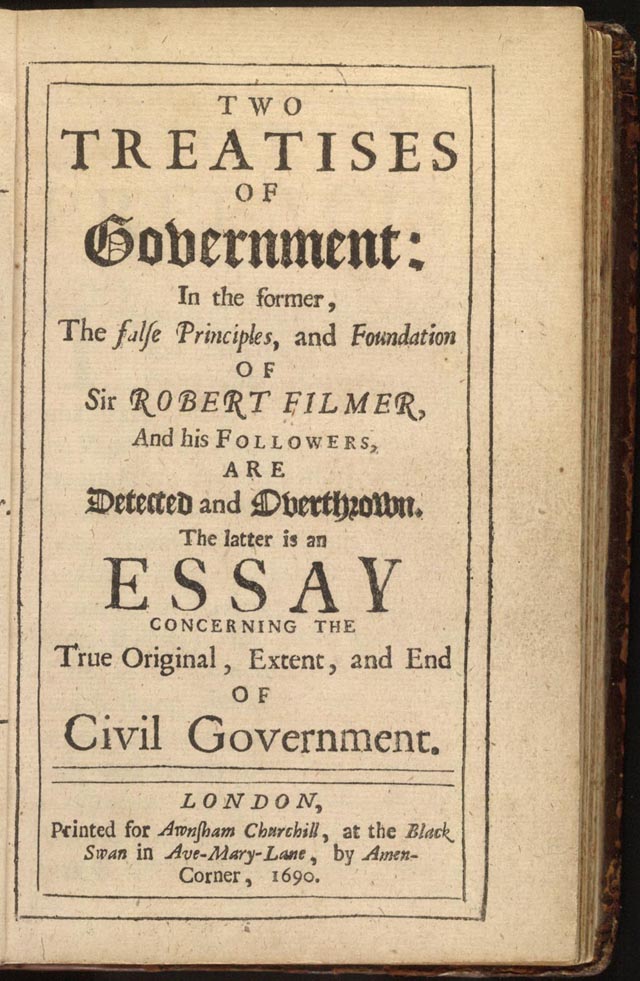

. He returned to England in 1679 when Shaftesbury's political fortunes took a brief positive turn. Around this time, most likely at Shaftesbury's prompting, Locke composed the bulk of the ''Two Treatises of Government

''Two Treatises of Government'' (or ''Two Treatises of Government: In the Former, The False Principles, and Foundation of Sir Robert Filmer, and His Followers, Are Detected and Overthrown. The Latter Is an Essay Concerning The True Original, ...

''. While it was once thought that Locke wrote the ''Treatises'' to defend the Glorious Revolution

The Glorious Revolution; gd, Rèabhlaid Ghlòrmhor; cy, Chwyldro Gogoneddus , also known as the ''Glorieuze Overtocht'' or ''Glorious Crossing'' in the Netherlands, is the sequence of events leading to the deposition of King James II and ...

of 1688, recent scholarship has shown that the work was composed well before this date. The work is now viewed as a more general argument against absolute monarchy

Absolute monarchy (or Absolutism as a doctrine) is a form of monarchy in which the monarch rules in their own right or power. In an absolute monarchy, the king or queen is by no means limited and has absolute power, though a limited constitut ...

(particularly as espoused by Robert Filmer

Sir Robert Filmer (c. 1588 – 26 May 1653) was an English political theorist who defended the divine right of kings. His best known work, '' Patriarcha'', published posthumously in 1680, was the target of numerous Whig attempts at rebuttal ...

and Thomas Hobbes

Thomas Hobbes ( ; 5/15 April 1588 – 4/14 December 1679) was an English philosopher, considered to be one of the founders of modern political philosophy. Hobbes is best known for his 1651 book ''Leviathan'', in which he expounds an influent ...

) and for individual consent as the basis of political legitimacy

In political science, legitimacy is the right and acceptance of an authority, usually a governing law or a regime. Whereas ''authority'' denotes a specific position in an established government, the term ''legitimacy'' denotes a system of gover ...

. Although Locke was associated with the influential Whigs, his ideas about natural rights and government are today considered quite revolutionary for that period in English history.

The Netherlands

Locke fled to theNetherlands

)

, anthem = ( en, "William of Nassau")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of the Netherlands

, established_title = Before independence

, established_date = Spanish Netherl ...

in 1683, under strong suspicion of involvement in the Rye House Plot

The Rye House Plot of 1683 was a plan to assassinate King Charles II of England and his brother (and heir to the throne) James, Duke of York. The royal party went from Westminster to Newmarket to see horse races and were expected to make the ...

, although there is little evidence to suggest that he was directly involved in the scheme. The philosopher and novelist Rebecca Newberger Goldstein argues that during his five years in Holland, Locke chose his friends "from among the same freethinking members of dissenting Protestant groups as Spinoza's small group of loyal confidants. aruch Spinoza had died in 1677.

Aruch ( hy, Արուճ; until 1970, TalishJohn Brady Kiesling, Raffi Kojian (2001). ''Rediscovering Armenia An Archaeological/touristic Gazetteer and Map Set for the Historical Monuments of Armenia''. Yerevan: Tigran Mets; p. 17), is a village in ...

Locke almost certainly met men in Amsterdam who spoke of the ideas of that renegade Jew who... insisted on identifying himself through his religion of reason alone." While she says that "Locke's strong empiricist tendencies" would have "disinclined him to read a grandly metaphysical work such as Spinoza's ''Ethics

Ethics or moral philosophy is a branch of philosophy that "involves systematizing, defending, and recommending concepts of right and wrong behavior".''Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy'' The field of ethics, along with aesthetics, concerns m ...

'', in other ways he was deeply receptive to Spinoza's ideas, most particularly to the rationalist's well thought out argument for political and religious tolerance

Religious toleration may signify "no more than forbearance and the permission given by the adherents of a dominant religion for other religions to exist, even though the latter are looked on with disapproval as inferior, mistaken, or harmful". ...

and the necessity of the separation of church and state." In the Netherlands, Locke had time to return to his writing, spending a great deal of time working on the ''Essay Concerning Human Understanding'' and composing the ''Letter on Toleration.''

Return to England

Locke did not return home until after theGlorious Revolution

The Glorious Revolution; gd, Rèabhlaid Ghlòrmhor; cy, Chwyldro Gogoneddus , also known as the ''Glorieuze Overtocht'' or ''Glorious Crossing'' in the Netherlands, is the sequence of events leading to the deposition of King James II and ...

. Locke accompanied Mary II back to England in 1688. The bulk of Locke's publishing took place upon his return from exilehis aforementioned ''Essay Concerning Human Understanding

''An Essay Concerning Human Understanding'' is a work by John Locke concerning the foundation of human knowledge and understanding. It first appeared in 1689 (although dated 1690) with the printed title ''An Essay Concerning Humane Understand ...

'', the ''Two Treatises of Government

''Two Treatises of Government'' (or ''Two Treatises of Government: In the Former, The False Principles, and Foundation of Sir Robert Filmer, and His Followers, Are Detected and Overthrown. The Latter Is an Essay Concerning The True Original, ...

'' and ''A Letter Concerning Toleration

''A Letter Concerning Toleration'' by John Locke was originally published in 1689. Its initial publication was in Latin, and it was immediately translated into other languages. Locke's work appeared amidst a fear that Catholicism might be taking ...

'' all appearing in quick succession.

Locke's close friend Lady Masham

]

Damaris, Lady Masham (18 January 1659 – 20 April 1708) was an English writer, philosopher, theologian, and advocate for women's education who is characterized as a proto-feminist. She overcame some weakness of eyesight and lack of access t ...

invited him to join her at Otes, the Mashams' country house in Essex. Although his time there was marked by variable health from asthma

Asthma is a long-term inflammatory disease of the airways of the lungs. It is characterized by variable and recurring symptoms, reversible airflow obstruction, and easily triggered bronchospasms. Symptoms include episodes of wheezing, cou ...

attacks, he nevertheless became an intellectual hero of the Whigs. During this period he discussed matters with such figures as John Dryden

''

John Dryden (; – ) was an English poet, literary critic, translator, and playwright who in 1668 was appointed England's first Poet Laureate.

He is seen as dominating the literary life of Restoration England to such a point that the per ...

and Isaac Newton

Sir Isaac Newton (25 December 1642 – 20 March 1726/27) was an English mathematician, physicist, astronomer, alchemist, theologian, and author (described in his time as a "natural philosopher"), widely recognised as one of the grea ...

.

Death

He died on 28 October 1704, and is buried in the churchyard of the village ofHigh Laver

High Laver is a village and civil parish in the Epping Forest district of the county of Essex, England. The parish is noted for its association with the philosopher John Locke.

History

High Laver is historically a rural agricultural parish, pred ...

, east of Harlow

Harlow is a large town and local government district located in the west of Essex, England. Founded as a new town, it is situated on the border with Hertfordshire and London, Harlow occupies a large area of land on the south bank of the upp ...

in Essex, where he had lived in the household of Sir Francis Masham since 1691. Locke never married nor had children.

Events that happened during Locke's lifetime include the English Restoration

The Restoration of the Stuart monarchy in the kingdoms of England, Scotland and Ireland took place in 1660 when King Charles II returned from exile in continental Europe. The preceding period of the Protectorate and the civil wars came to be ...

, the Great Plague of London

The Great Plague of London, lasting from 1665 to 1666, was the last major epidemic of the bubonic plague to occur in England. It happened within the centuries-long Second Pandemic, a period of intermittent bubonic plague epidemics that origi ...

, the Great Fire of London

The Great Fire of London was a major conflagration that swept through central London from Sunday 2 September to Thursday 6 September 1666, gutting the medieval City of London inside the old Roman city wall, while also extending past the ...

, and the Glorious Revolution

The Glorious Revolution; gd, Rèabhlaid Ghlòrmhor; cy, Chwyldro Gogoneddus , also known as the ''Glorieuze Overtocht'' or ''Glorious Crossing'' in the Netherlands, is the sequence of events leading to the deposition of King James II and ...

. He did not quite see the Act of Union of 1707

The Acts of Union ( gd, Achd an Aonaidh) were two Acts of Parliament: the Union with Scotland Act 1706 passed by the Parliament of England, and the Union with England Act 1707 passed by the Parliament of Scotland. They put into effect the te ...

, though the thrones of England and Scotland were held in personal union

A personal union is the combination of two or more states that have the same monarch while their boundaries, laws, and interests remain distinct. A real union, by contrast, would involve the constituent states being to some extent interlink ...

throughout his lifetime. Constitutional monarchy

A constitutional monarchy, parliamentary monarchy, or democratic monarchy is a form of monarchy in which the monarch exercises their authority in accordance with a constitution and is not alone in decision making. Constitutional monarchies dif ...

and parliamentary democracy

A parliamentary system, or parliamentarian democracy, is a system of democratic governance of a state (or subordinate entity) where the executive derives its democratic legitimacy from its ability to command the support ("confidence") of the ...

were in their infancy during Locke's time.

Philosophy

In the late 17th and early 18th centuries, Locke's '' Two Treatises'' were rarely cited. Historian Julian Hoppit said of the book, "except among some Whigs, even as a contribution to the intense debate of the 1690s it made little impression and was generally ignored until 1703 (though in Oxford in 1695 it was reported to have made 'a great noise')." John Kenyon, in his study of British political debate from 1689 to 1720, has remarked that Locke's theories were "mentioned so rarely in the early stages of the loriousRevolution, up to 1692, and even less thereafter, unless it was to heap abuse on them" and that "no one, including most Whigs, asready for the idea of a notional or abstract contract of the kind adumbrated by Locke". In contrast, Kenyon adds that

In the late 17th and early 18th centuries, Locke's '' Two Treatises'' were rarely cited. Historian Julian Hoppit said of the book, "except among some Whigs, even as a contribution to the intense debate of the 1690s it made little impression and was generally ignored until 1703 (though in Oxford in 1695 it was reported to have made 'a great noise')." John Kenyon, in his study of British political debate from 1689 to 1720, has remarked that Locke's theories were "mentioned so rarely in the early stages of the loriousRevolution, up to 1692, and even less thereafter, unless it was to heap abuse on them" and that "no one, including most Whigs, asready for the idea of a notional or abstract contract of the kind adumbrated by Locke". In contrast, Kenyon adds that Algernon Sidney

Algernon Sidney or Sydney (15 January 1623 – 7 December 1683) was an English politician, republican political theorist and colonel. A member of the middle part of the Long Parliament and commissioner of the trial of King Charles I of Englan ...

's ''Discourses Concerning Government'' were "certainly much more influential than Locke's ''Two Treatises.''"Kenyon (1977) adds: "Any unbiassed study of the position shows in fact that it was Filmer, not Hobbes, Locke or Sidney, who was the most influential thinker of the age" (p. 63).

In the 50 years after Queen Anne's death in 1714, the ''Two Treatises'' were reprinted only once (except in the collected works of Locke). However, with the rise of American resistance to British taxation, the ''Second Treatise of Government

''Two Treatises of Government'' (or ''Two Treatises of Government: In the Former, The False Principles, and Foundation of Sir Robert Filmer, and His Followers, Are Detected and Overthrown. The Latter Is an Essay Concerning The True Original, ...

'' gained a new readership; it was frequently cited in the debates in both America and Britain. The first American printing occurred in 1773 in Boston.

Locke exercised a profound influence on political philosophy

Political philosophy or political theory is the philosophical study of government, addressing questions about the nature, scope, and legitimacy of public agents and institutions and the relationships between them. Its topics include politics, l ...

, in particular on modern liberalism. Michael Zuckert

Michael P. Zuckert (born July 24, 1942) is an American political philosopher and Reeves Dreux Professor of Political Science at the University of Notre Dame. Zuckert earned a bachelor's degree in Cornell University in 1964, and completed his mast ...

has argued that Locke launched liberalism by tempering Hobbesian absolutism and clearly separating the realms of Church and State. He had a strong influence on Voltaire

François-Marie Arouet (; 21 November 169430 May 1778) was a French Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment writer, historian, and philosopher. Known by his ''Pen name, nom de plume'' M. de Voltaire (; also ; ), he was famous for his wit, and his ...

, who called him "''le sage'' Locke". His arguments concerning liberty

Liberty is the ability to do as one pleases, or a right or immunity enjoyed by prescription or by grant (i.e. privilege). It is a synonym for the word freedom.

In modern politics, liberty is understood as the state of being free within society fr ...

and the social contract

In moral and political philosophy

Political philosophy or political theory is the philosophical study of government, addressing questions about the nature, scope, and legitimacy of public agents and institutions and the relationships betw ...

later influenced the written works of Alexander Hamilton

Alexander Hamilton (January 11, 1755 or 1757July 12, 1804) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first United States secretary of the treasury from 1789 to 1795.

Born out of wedlock in Charlest ...

, James Madison

James Madison Jr. (March 16, 1751June 28, 1836) was an American statesman, diplomat, and Founding Father. He served as the fourth president of the United States from 1809 to 1817. Madison is hailed as the "Father of the Constitution" for hi ...

, Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 18 ...

, and other Founding Fathers of the United States

The Founding Fathers of the United States, known simply as the Founding Fathers or Founders, were a group of late-18th-century American Revolution, American revolutionary leaders who United Colonies, united the Thirteen Colonies, oversaw the Am ...

. In fact, one passage from the ''Second Treatise'' is reproduced verbatim in the Declaration of Independence, the reference to a "long train of abuses". Such was Locke's influence that Thomas Jefferson wrote:However, Locke's influence may have been even more profound in the realm ofBacon Bacon is a type of salt-cured pork made from various cuts, typically the belly or less fatty parts of the back. It is eaten as a side dish (particularly in breakfasts), used as a central ingredient (e.g., the bacon, lettuce, and tomato sand ..., Locke and Newton… I consider them as the three greatest men that have ever lived, without any exception, and as having laid the foundation of those superstructures which have been raised in the Physical and Moral sciences.

epistemology

Epistemology (; ), or the theory of knowledge, is the branch of philosophy concerned with knowledge. Epistemology is considered a major subfield of philosophy, along with other major subfields such as ethics, logic, and metaphysics.

Episte ...

. Locke redefined subjectivity

Subjectivity in a philosophical context has to do with a lack of objective reality. Subjectivity has been given various and ambiguous definitions by differing sources as it is not often the focal point of philosophical discourse.Bykova, Marina F ...

, or ''self'', leading intellectual historians

An intellectual is a person who engages in critical thinking, research, and reflection about the reality of society, and who proposes solutions for the normative problems of society. Coming from the world of culture, either as a creator or as ...

such as Charles Taylor and Jerrold Seigel

Jerrold Seigel is a prominent American historian. He is Professor Emeritus at New York University. He taught for twenty-five years at Princeton University. His book ''Modernity and Bourgeois Life: Society, Politics and Culture in England, France, ...

to argue that Locke's ''An Essay Concerning Human Understanding

''An Essay Concerning Human Understanding'' is a work by John Locke concerning the foundation of human knowledge and understanding. It first appeared in 1689 (although dated 1690) with the printed title ''An Essay Concerning Humane Understan ...

'' (1689/90) marks the beginning of the modern Western conception of the ''self''.

Locke's theory of association heavily influenced the subject matter of modern psychology

Psychology is defined as "the scientific study of behavior and mental processes". Philosophical interest in the human mind and behavior dates back to the ancient civilizations of Egypt, Persia, Greece, China, and India.

Psychology as a field of ...

. At the time, Locke's recognition of two types of ideas, ''simple'' and ''complex''and, more importantly, their interaction through associationinspired other philosophers, such as David Hume

David Hume (; born David Home; 7 May 1711 NS (26 April 1711 OS) – 25 August 1776) Cranston, Maurice, and Thomas Edmund Jessop. 2020 999br>David Hume" ''Encyclopædia Britannica''. Retrieved 18 May 2020. was a Scottish Enlightenment philo ...

and George Berkeley, to revise and expand this theory and apply it to explain how humans gain knowledge in the physical world.

Religious tolerance

Writing his '' Letters Concerning Toleration'' (1689–1692) in the aftermath of the

Writing his '' Letters Concerning Toleration'' (1689–1692) in the aftermath of the European wars of religion

The European wars of religion were a series of wars waged in Europe during the 16th, 17th and early 18th centuries. Fought after the Protestant Reformation began in 1517, the wars disrupted the religious and political order in the Catholic Chu ...

, Locke formulated a classic reasoning for religious tolerance

Religious toleration may signify "no more than forbearance and the permission given by the adherents of a dominant religion for other religions to exist, even though the latter are looked on with disapproval as inferior, mistaken, or harmful". ...

, in which three arguments are central:

# earthly judges, the state

A state is a centralized political organization that imposes and enforces rules over a population within a territory. There is no undisputed definition of a state. One widely used definition comes from the German sociologist Max Weber: a "stat ...

in particular, and human beings generally, cannot dependably evaluate the truth-claims of competing religious standpoints;

# even if they could, enforcing a single 'true religion' would not have the desired effect, because belief cannot be compelled by violence;

# coercing religious uniformity

Religious uniformity occurs when government is used to promote one state religion, denomination, or philosophy to the exclusion of all other religious beliefs. History

Religious uniformity was common in many modern theocratic and atheistic govern ...

would lead to more social disorder than allowing diversity.

With regard to his position on religious tolerance, Locke was influenced by Baptist

Baptists form a major branch of Protestantism distinguished by baptizing professing Christian believers only (believer's baptism), and doing so by complete immersion. Baptist churches also generally subscribe to the doctrines of soul compete ...

theologians like John Smyth and Thomas Helwys

Thomas Helwys (c. 1575 – c. 1616), an English minister, was one of the joint founders, with John Smyth, of the General Baptist denomination. In the early seventeenth century, Helwys was principal formulator of demand that the church and t ...

, who had published tracts demanding freedom of conscience

Freedom of thought (also called freedom of conscience) is the freedom of an individual to hold or consider a fact, viewpoint, or thought, independent of others' viewpoints.

Overview

Every person attempts to have a cognitive proficiency by ...

in the early 17th century. Baptist theologian Roger Williams

Roger Williams (21 September 1603between 27 January and 15 March 1683) was an English-born New England Puritan minister, theologian, and author who founded Providence Plantations, which became the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantation ...

founded the colony of Rhode Island

Rhode Island (, like ''road'') is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It is the List of U.S. states by area, smallest U.S. state by area and the List of states and territories of the United States ...

in 1636, where he combined a democratic constitution

Democracy (From grc, δημοκρατία, dēmokratía, ''dēmos'' 'people' and ''kratos'' 'rule') is a form of government in which people, the people have the authority to deliberate and decide legislation ("direct democracy"), or to choo ...

with unlimited religious freedom. His tract, ''The Bloudy Tenent of Persecution for Cause of Conscience

''The Bloudy Tenent of Persecution, for Cause of Conscience, Discussed in a Conference between Truth and Peace'' is a 1644 book about government force written by Roger Williams, the founder of Providence Plantations in New England and the co-found ...

'' (1644), which was widely read in the mother country, was a passionate plea for absolute religious freedom and the total separation of church and state

The separation of church and state is a philosophical and jurisprudential concept for defining political distance in the relationship between religious organizations and the state. Conceptually, the term refers to the creation of a secular sta ...

. Freedom of conscience had had high priority on the theological, philosophical, and political agenda, as Martin Luther

Martin Luther (; ; 10 November 1483 – 18 February 1546) was a German priest, theologian, author, hymnwriter, and professor, and Order of Saint Augustine, Augustinian friar. He is the seminal figure of the Reformation, Protestant Refo ...

refused to recant his beliefs before the Diet

Diet may refer to:

Food

* Diet (nutrition), the sum of the food consumed by an organism or group

* Dieting, the deliberate selection of food to control body weight or nutrient intake

** Diet food, foods that aid in creating a diet for weight loss ...

of the Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a Polity, political entity in Western Europe, Western, Central Europe, Central, and Southern Europe that developed during the Early Middle Ages and continued until its Dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire, dissolution i ...

at Worms Worms may refer to:

*Worm, an invertebrate animal with a tube-like body and no limbs

Places

*Worms, Germany

Worms () is a city in Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany, situated on the Upper Rhine about south-southwest of Frankfurt am Main. It had ...

in 1521, unless he would be proved false by the Bible.

Slavery and child labour

Locke's views on slavery were multifaceted and complex. Although he wrote against slavery in general, Locke was an investor and beneficiary of theslave trading

The history of slavery spans many cultures, nationalities, and Slavery and religion, religions from Ancient history, ancient times to the present day. Likewise, its victims have come from many different ethnicities and religious groups. The socia ...

Royal Africa Company

The Royal African Company (RAC) was an English mercantile (trading) company set up in 1660 by the royal Stuart family and City of London merchants to trade along the west coast of Africa. It was led by the Duke of York, who was the brother o ...

. In addition, while secretary to the Earl of Shaftesbury

Earl of Shaftesbury is a title in the Peerage of England. It was created in 1672 for Anthony Ashley-Cooper, 1st Baron Ashley, a prominent politician in the Cabal then dominating the policies of King Charles II. He had already succeeded his fa ...

, Locke participated in drafting the ''Fundamental Constitutions of Carolina

The ''Fundamental Constitutions of Carolina'' were adopted on March 1, 1669 by the eight Lords Proprietors of the Province of Carolina, which included most of the land between what is now Virginia and Florida. It replaced the '' Charter of Caro ...

'', which established a quasi-feudal aristocracy

Aristocracy (, ) is a form of government that places strength in the hands of a small, privileged ruling class, the aristocracy (class), aristocrats. The term derives from the el, αριστοκρατία (), meaning 'rule of the best'.

At t ...

and gave Carolinian planters

Planters Nut & Chocolate Company is an American snack food company now owned by Hormel Foods. Planters is best known for its processed nuts and for the Mr. Peanut icon that symbolizes them. Mr. Peanut was created by grade schooler Antonio Gentil ...

absolute power over their enslaved chattel property; the constitutions pledged that "every freeman of Carolina shall have absolute power and authority over his negro slaves". Philosopher Martin Cohen notes that Locke, as secretary to the Council of Trade and Plantations and a member of the Board of Trade, was "one of just half a dozen men who created and supervised both the colonies and their iniquitous systems of servitude".

According to American historian James Farr, Locke never expressed any thoughts concerning his contradictory opinions regarding slavery, which Farr ascribes to his personal involvement in the slave trade. Locke's positions on slavery have been described as hypocritical, and laying the foundation for the Founding Fathers to hold similarly contradictory thoughts regarding freedom and slavery.

Historian Holly Brewer has argued, however, that Locke's role in the Constitution of Carolina has been exaggerated and that he was merely paid to revise and make copies of a document that had already been partially written before he became involved; she compares Locke's role to a lawyer writing a will. She further says that Locke was paid in Royal African Company stock in lieu of money for his work as a secretary for a governmental sub-committee and that he sold the stock after a few years. Brewer likewise argues that Locke actively worked to undermine slavery in Virginia while heading a Board of Trade created by William of Orange following the Glorious Revolution. He specifically attacked colonial policy granting land to slave owners and encouraged the baptism and Christian education of the children of enslaved Africans to undercut a major justification of slaverythat they were heathens that possessed no rights.

Locke also supported child labour

Child labour refers to the exploitation of children through any form of work that deprives children of their childhood, interferes with their ability to attend regular school, and is mentally, physically, socially and morally harmful. Such e ...

. In his "Essay on the Poor Law", he turns to the education of the poor; he laments that "the children of labouring people are an ordinary burden to the parish, and are usually maintained in idleness, so that their labour also is generally lost to the public till they are 12 or 14 years old". He suggests, therefore, that "working schools" be set up in each parish in England for poor children so that they will be "from infancy hree years oldinured to work". He goes on to outline the economics of these schools, arguing not only that they will be profitable for the parish, but also that they will instill a good work ethic in the children.

Government

Locke's political theory was founded upon that ofsocial contract

In moral and political philosophy

Political philosophy or political theory is the philosophical study of government, addressing questions about the nature, scope, and legitimacy of public agents and institutions and the relationships betw ...

. Unlike Thomas Hobbes

Thomas Hobbes ( ; 5/15 April 1588 – 4/14 December 1679) was an English philosopher, considered to be one of the founders of modern political philosophy. Hobbes is best known for his 1651 book ''Leviathan'', in which he expounds an influent ...

, Locke believed that human nature

Human nature is a concept that denotes the fundamental dispositions and characteristics—including ways of thinking, feeling, and acting—that humans are said to have naturally. The term is often used to denote the essence of humankind, or ...

is characterised by reason

Reason is the capacity of consciously applying logic by drawing conclusions from new or existing information, with the aim of seeking the truth. It is closely associated with such characteristically human activities as philosophy, science, ...

and tolerance. Like Hobbes, however, Locke believed that human nature allows people to be selfish. This is apparent with the introduction of currency. In a natural state, all people were equal and independent, and everyone had a natural right to defend his "life, health, liberty, or possessions".Locke, John. 690

__NOTOC__

Year 690 (Roman numerals, DCXC) was a common year starting on Saturday (link will display the full calendar) of the Julian calendar. The denomination 690 for this year has been used since the early medieval period, when the Anno Domi ...

2017. Second Treatise of Government

' (10th ed.), digitized by D. Gowan.

Project Gutenberg

Project Gutenberg (PG) is a Virtual volunteering, volunteer effort to digitize and archive cultural works, as well as to "encourage the creation and distribution of eBooks."

It was founded in 1971 by American writer Michael S. Hart and is the ...

. Retrieved 2 June 2020. Most scholars trace the phrase "Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness

"Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness" is a well-known phrase from the United States Declaration of Independence. Scanned image of the Jefferson's "original Rough draught" of the Declaration of Independence, written in June 1776, including ...

" in the American Declaration of Independence

The United States Declaration of Independence, formally The unanimous Declaration of the thirteen States of America, is the pronouncement and founding document adopted by the Second Continental Congress meeting at Pennsylvania State House ...

to Locke's theory of rights, although other origins have been suggested.

Like Hobbes, Locke assumed that the sole right to defend in the state of nature was not enough, so people established a civil society

Civil society can be understood as the "third sector" of society, distinct from government and business, and including the family and the private sphere.separation of powers

Separation of powers refers to the division of a state's government into branches, each with separate, independent powers and responsibilities, so that the powers of one branch are not in conflict with those of the other branches. The typic ...

and believed that revolution is not only a right

Rights are law, legal, social, or ethics, ethical principles of Liberty, freedom or entitlement; that is, rights are the fundamental normative rules about what is allowed of people or owed to people according to some legal system, social convent ...

but an obligation in some circumstances. These ideas would come to have profound influence on the Declaration of Independence

A declaration of independence or declaration of statehood or proclamation of independence is an assertion by a polity in a defined territory that it is independent and constitutes a state. Such places are usually declared from part or all of th ...

and the Constitution of the United States

The Constitution of the United States is the supreme law of the United States of America. It superseded the Articles of Confederation, the nation's first constitution, in 1789. Originally comprising seven articles, it delineates the natio ...

.

Accumulation of wealth

According to Locke, unused property is wasteful and an offence against nature, but, with the introduction of "durable" goods, men could exchange their excessive perishable goods for those which would last longer and thus not offend thenatural law

Natural law ( la, ius naturale, ''lex naturalis'') is a system of law based on a close observation of human nature, and based on values intrinsic to human nature that can be deduced and applied independently of positive law (the express enacte ...

. In his view, the introduction of money marked the culmination of this process, making possible the unlimited accumulation of property without causing waste through spoilage. He also includes gold or silver as money because they may be "hoarded up without injury to anyone", as they do not spoil or decay in the hands of the possessor. In his view, the introduction of money eliminates limits to accumulation. Locke stresses that inequality has come about by tacit agreement on the use of money, not by the social contract establishing civil society

Civil society can be understood as the "third sector" of society, distinct from government and business, and including the family and the private sphere.law of land regulating property. Locke is aware of a problem posed by unlimited accumulation, but does not consider it his task. He just implies that government would function to moderate the conflict between the unlimited accumulation of property and a more nearly equal distribution of wealth; he does not identify which principles that government should apply to solve this problem. However, not all elements of his thought form a consistent whole. For example, the

Locke was an assiduous book collector and notetaker throughout his life. By his death in 1704, Locke had amassed a library of more than 3,000 books, a significant number in the seventeenth century. Unlike some of his contemporaries, Locke took care to catalogue and preserve his library, and his will made specific provisions for how his library was to be distributed after his death. Locke's will offered Lady Masham the choice of "any four folios, eight quartos and twenty books of less volume, which she shall choose out of the books in my Library."Quoted in Harrison, John; Laslett, Peter (1971). ''The Library of John Locke''. Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 8. Locke also gave six titles to his “good friend” Anthony Collins, but Locke bequeathed the majority of his collection to his cousin Peter King (later Lord King) and to Lady Masham's son, Francis Cudworth Masham.

Francis Masham was promised one “moiety” (half) of Locke's library when he reached “the age of one and twenty years.” The other “moiety” of Locke's books, along with his manuscripts, passed to his cousin King. Over the next two centuries, the Masham portion of Locke's library was dispersed. The manuscripts and books left to King, however, remained with King's descendants (later the

Locke was an assiduous book collector and notetaker throughout his life. By his death in 1704, Locke had amassed a library of more than 3,000 books, a significant number in the seventeenth century. Unlike some of his contemporaries, Locke took care to catalogue and preserve his library, and his will made specific provisions for how his library was to be distributed after his death. Locke's will offered Lady Masham the choice of "any four folios, eight quartos and twenty books of less volume, which she shall choose out of the books in my Library."Quoted in Harrison, John; Laslett, Peter (1971). ''The Library of John Locke''. Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 8. Locke also gave six titles to his “good friend” Anthony Collins, but Locke bequeathed the majority of his collection to his cousin Peter King (later Lord King) and to Lady Masham's son, Francis Cudworth Masham.

Francis Masham was promised one “moiety” (half) of Locke's library when he reached “the age of one and twenty years.” The other “moiety” of Locke's books, along with his manuscripts, passed to his cousin King. Over the next two centuries, the Masham portion of Locke's library was dispersed. The manuscripts and books left to King, however, remained with King's descendants (later the  The printed books in Locke's library reflected his various intellectual interests as well as his movements at different stages of his life. Locke travelled extensively in France and the Netherlands during the 1670s and 1680s, and during this time he acquired many books from the continent. Only half of the books in Locke's library were printed in England, while close to 40% came from France and the Netherlands. These books cover a wide range of subjects. According to John Harrison and Peter Laslett, the largest genres in Locke's library were

The printed books in Locke's library reflected his various intellectual interests as well as his movements at different stages of his life. Locke travelled extensively in France and the Netherlands during the 1670s and 1680s, and during this time he acquired many books from the continent. Only half of the books in Locke's library were printed in England, while close to 40% came from France and the Netherlands. These books cover a wide range of subjects. According to John Harrison and Peter Laslett, the largest genres in Locke's library were  These commonplace books were highly personal and were designed to be used by Locke himself rather than accessible to a wide audience. Locke's notes are often abbreviated and are full of codes which he used to reference material across notebooks. Another way Locke personalized his notebooks was by devising his own method of creating indexes using a grid system and Latin keywords. Instead of recording entire words, his indexes shortened words to their first letter and vowel. Thus, the word "Epistle" would be classified as "Ei". Locke published his method in French in 1686, and it was republished posthumously in English in 1706.

Some of the books in Locke's library at the Bodleian are a combination of manuscript and print. Locke had some of his books interleaved, meaning that they were bound with blank sheets in-between the printed pages to enable annotations. Locke interleaved and annotated his five volumes of the New Testament in French, Greek, and Latin (Bodleian Locke 9.103-107). Locke did the same with his copy of Thomas Hyde's Bodleian Library catalogue (Bodleian Locke 16.17), which Locke used to create a catalogue of his own library.

These commonplace books were highly personal and were designed to be used by Locke himself rather than accessible to a wide audience. Locke's notes are often abbreviated and are full of codes which he used to reference material across notebooks. Another way Locke personalized his notebooks was by devising his own method of creating indexes using a grid system and Latin keywords. Instead of recording entire words, his indexes shortened words to their first letter and vowel. Thus, the word "Epistle" would be classified as "Ei". Locke published his method in French in 1686, and it was republished posthumously in English in 1706.

Some of the books in Locke's library at the Bodleian are a combination of manuscript and print. Locke had some of his books interleaved, meaning that they were bound with blank sheets in-between the printed pages to enable annotations. Locke interleaved and annotated his five volumes of the New Testament in French, Greek, and Latin (Bodleian Locke 9.103-107). Locke did the same with his copy of Thomas Hyde's Bodleian Library catalogue (Bodleian Locke 16.17), which Locke used to create a catalogue of his own library.

excerpt and text search

* John Dunn (political theorist), Dunn, John, 1984. ''Locke''. Oxford Uni. Press. A succinct introduction. * ———, 1969. ''The Political Thought of John Locke: An Historical Account of the Argument of the "Two Treatises of Government"''. Cambridge Uni. Press. Introduced the interpretation which emphasises the theological element in Locke's political thought. * * Hudson, Nicholas, "John Locke and the Tradition of Nominalism," in: ''Nominalism and Literary Discourse'', ed. Hugo Keiper, Christoph Bode, and Richard Utz (Amsterdam: Rodopi, 1997), pp. 283–99. * to * * * ''Locke Studies'', appearing annually from 2001, formerly ''The Locke Newsletter'' (1970–2000), publishes scholarly work on John Locke. * * C. B. Macpherson, Macpherson, C.B. ''The Political Theory of Possessive Individualism: Hobbes to Locke'' (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1962). Establishes the deep affinity from Hobbes to Harrington, the Levellers, and Locke through to nineteenth-century utilitarianism. * * * * * * James Tully (philosopher), Tully, James, 1980. ''A Discourse on Property : John Locke and his Adversaries''. Cambridge Uni. Press * * John W. Yolton, Yolton, John W., ed., 1969. ''John Locke: Problems and Perspectives''. Cambridge Uni. Press. * Yolton, John W., ed., 1993. ''A Locke Dictionary''. Oxford: Blackwell. * Zuckert, Michael, ''Launching Liberalism: On Lockean Political Philosophy''. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas.

The Clarendon Edition of the Works of John Locke

''Of the Conduct of the Understanding''

* * *

Work by John Locke

at Online Books * ''The Works of John Locke'' *

* [http://www.libraries.psu.edu/tas/locke/mss/index.html John Locke Manuscripts]

Updated versions of ''Essay Concerning Human Understanding'', ''Second Treatise of Government'', ''Letter on Toleration'' and ''Conduct of the Understanding''

edited (i.e. modernized and abridged) by Jonathan Bennett (philosopher), Jonathan Bennett

John Locke Bibliography

Locke Studies An Annual Journal of Locke Research

* . * . * . * , a complex and positive answer. * *Anstey, Peter,

John Locke and Natural Philosophy

'' Oxford University Press'','' 2011''.'' {{DEFAULTSORT:Locke, John John Locke, 1632 births 1704 deaths 17th-century English male writers 17th-century English medical doctors 17th-century English philosophers 17th-century English writers Alumni of Christ Church, Oxford Anglican philosophers British classical liberals British expatriates in the Dutch Republic Critics of atheism Empiricists English Anglicans English Christian theologians English political philosophers Enlightenment philosophers Epistemologists Fellows of Christ Church, Oxford Fellows of the Royal Society Founders of philosophical traditions Metaphysicians Ontologists People educated at Westminster School, London People from Epping Forest District People from Wrington People of the Rye House Plot Philosophers of identity Philosophers of language Philosophers of law Philosophers of education

labour theory of value

The labor theory of value (LTV) is a theory of value that argues that the economic value of a good or service is determined by the total amount of " socially necessary labor" required to produce it.

The LTV is usually associated with Marxian ...

in the ''Two Treatises of Government

''Two Treatises of Government'' (or ''Two Treatises of Government: In the Former, The False Principles, and Foundation of Sir Robert Filmer, and His Followers, Are Detected and Overthrown. The Latter Is an Essay Concerning The True Original, ...

'' stands side by side with the demand-and-supply theory of value developed in a letter he wrote titled ''Some Considerations on the Consequences of the Lowering of Interest and the Raising of the Value of Money''. Moreover, Locke anchors property in labour but, in the end, upholds unlimited accumulation of wealth.

Ideas

Economics

On price theory

Locke's general theory of value and price is a supply-and-demand theory, set out in a letter to a member of parliament in 1691, titled ''Some Considerations on the Consequences of the Lowering of Interest and the Raising of the Value of Money''. In it, he refers to supply as ''quantity'' and demand as ''rent'': "The price of any commodity rises or falls by the proportion of the number of buyers and sellers" and "that which regulates the price…f goods

F, or f, is the sixth letter in the Latin alphabet, used in the modern English alphabet, the alphabets of other western European languages and others worldwide. Its name in English is ''ef'' (pronounced ), and the plural is ''efs''.

Hist ...

is nothing else but their quantity in proportion to their rent."

The quantity theory of money

In monetary economics, the quantity theory of money (often abbreviated QTM) is one of the directions of Western economic thought that emerged in the 16th-17th centuries. The QTM states that the general price level of goods and services is directly ...

forms a special case of this general theory. His idea is based on "money answers all things" (Ecclesiastes

Ecclesiastes (; hbo, קֹהֶלֶת, Qōheleṯ, grc, Ἐκκλησιαστής, Ekklēsiastēs) is one of the Ketuvim ("Writings") of the Hebrew Bible and part of the Wisdom literature of the Christian Old Testament. The title commonly use ...

) or "rent of money is always sufficient, or more than enough" and "varies very little". Locke concludes that, as far as money is concerned, the demand

In economics, demand is the quantity of a good that consumers are willing and able to purchase at various prices during a given time. The relationship between price and quantity demand is also called the demand curve. Demand for a specific item ...

for it is exclusively regulated by its quantity, regardless of whether the demand is unlimited or constant. He also investigates the determinants of demand and supply. For supply

Supply may refer to:

*The amount of a resource that is available

**Supply (economics), the amount of a product which is available to customers

**Materiel, the goods and equipment for a military unit to fulfill its mission

*Supply, as in confidenc ...

, he explains the value of goods as based on their scarcity

In economics, scarcity "refers to the basic fact of life that there exists only a finite amount of human and nonhuman resources which the best technical knowledge is capable of using to produce only limited maximum amounts of each economic good. ...

and ability to be exchanged and consumed. He explains demand

In economics, demand is the quantity of a good that consumers are willing and able to purchase at various prices during a given time. The relationship between price and quantity demand is also called the demand curve. Demand for a specific item ...

for goods as based on their ability to yield a flow of income. Locke develops an early theory of capitalisation

Capitalization (American English) or capitalisation (British English) is writing a word with its first letter as a capital letter (uppercase letter) and the remaining letters in lower case, in writing systems with a case distinction. The term a ...

, such as of land, which has value because "by its constant production of saleable commodities it brings in a certain yearly income". He considers the demand for money as almost the same as demand for goods or land: it depends on whether money is wanted as medium of exchange

In economics, a medium of exchange is any item that is widely acceptable in exchange for goods and services. In modern economies, the most commonly used medium of exchange is currency.

The origin of "mediums of exchange" in human societies is ass ...

. As a medium of exchange, he states, "money is capable by exchange to procure us the necessaries or conveniences of life" and, for loanable funds In economics, the loanable funds doctrine is a theory of the market interest rate. According to this approach, the interest rate is determined by the demand for and supply of loanable funds. The term ''loanable funds'' includes all forms of credit, ...

, "it comes to be of the same nature with land by yielding a certain yearly income…or interest".

Monetary thoughts

Locke distinguishes two functions of money: as a ''counter'' to measure value, and as a ''pledge'' to lay claim togoods

In economics, goods are items that satisfy human wants

and provide utility, for example, to a consumer making a purchase of a satisfying product. A common distinction is made between goods which are transferable, and services, which are not t ...

. He believes that silver and gold, as opposed to paper money

A banknote—also called a bill (North American English), paper money, or simply a note—is a type of negotiable promissory note, made by a bank or other licensed authority, payable to the bearer on demand.

Banknotes were originally issued ...

, are the appropriate currency for international transactions. Silver and gold, he says, are treated to have equal value by all of humanity and can thus be treated as a pledge by anyone, while the value of paper money is only valid under the government which issues it.

Locke argues that a country should seek a favourable balance of trade

The balance of trade, commercial balance, or net exports (sometimes symbolized as NX), is the difference between the monetary value of a nation's exports and imports over a certain time period. Sometimes a distinction is made between a balance ...

, lest it fall behind other countries and suffer a loss in its trade. Since the world money stock

In macroeconomics, the money supply (or money stock) refers to the total volume of currency held by the public at a particular point in time. There are several ways to define "money", but standard measures usually include Circulation (curren ...

grows constantly, a country must constantly seek to enlarge its own stock. Locke develops his theory of foreign exchanges, in addition to commodity movements, there are also movements in country stock of money, and movements of capital determine exchange rate

In finance, an exchange rate is the rate at which one currency will be exchanged for another currency. Currencies are most commonly national currencies, but may be sub-national as in the case of Hong Kong or supra-national as in the case of ...

s. He considers the latter less significant and less volatile than commodity movements. As for a country's money stock, if it is large relative to that of other countries, he says it will cause the country's exchange to rise above par, as an export balance would do.

He also prepares estimates of the cash

In economics, cash is money in the physical form of currency, such as banknotes and coins.

In bookkeeping and financial accounting, cash is current assets comprising currency or currency equivalents that can be accessed immediately or near-imm ...

requirements for different economic groups (landholders

In common law systems, land tenure, from the French verb "tenir" means "to hold", is the legal regime in which land owned by an individual is possessed by someone else who is said to "hold" the land, based on an agreement between both individual ...

, labourers, and brokers). In each group he posits that the cash requirements are closely related to the length of the pay period. He argues the brokers—the middlemen—whose activities enlarge the monetary circuit and whose profits eat into the earnings of labourers and landholders, have a negative influence on both personal and the public economy to which they supposedly contribute.

Theory of value and property

Locke uses the concept of ''property

Property is a system of rights that gives people legal control of valuable things, and also refers to the valuable things themselves. Depending on the nature of the property, an owner of property may have the right to consume, alter, share, r ...

'' in both broad and narrow terms: broadly, it covers a wide range of human interests and aspirations; more particularly, it refers to material goods

In law, tangible property is literally anything that can be touched, and includes both real property and personal property (or moveable property), and stands in distinction to intangible property.

In English law and some Commonwealth legal ...

. He argues that property is a natural right

Some philosophers distinguish two types of rights, natural rights and legal rights.

* Natural rights are those that are not dependent on the laws or customs of any particular culture or government, and so are ''universal'', '' fundamental'' an ...

that is derived from labour

Labour or labor may refer to:

* Childbirth, the delivery of a baby

* Labour (human activity), or work

** Manual labour, physical work

** Wage labour, a socioeconomic relationship between a worker and an employer

** Organized labour and the labour ...

. In Chapter V of his '' Second Treatise'', Locke argues that the individual ownership of goods and property is justified by the labour exerted to produce such goods"at least where there is enough and

or AND may refer to:

Logic, grammar, and computing

* Conjunction (grammar), connecting two words, phrases, or clauses

* Logical conjunction in mathematical logic, notated as "∧", "⋅", "&", or simple juxtaposition

* Bitwise AND, a boolea ...

and as good, left in common for others" (para. 27)or to use property to produce goods beneficial to human society.

Locke states in his ''Second Treatise'' that nature on its own provides little of value to society, implying that the labour expended in the creation of goods gives them their value. From this premise, understood as a ''labour theory of value'', Locke developed a ''labour theory of property'', whereby ownership of property

Property is a system of rights that gives people legal control of valuable things, and also refers to the valuable things themselves. Depending on the nature of the property, an owner of property may have the right to consume, alter, share, r ...

is created by the application of labour. In addition, he believed that property precedes government and government cannot "dispose of the estates of the subjects arbitrarily". Karl Marx

Karl Heinrich Marx (; 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, economist, historian, sociologist, political theorist, journalist, critic of political economy, and socialist revolutionary. His best-known titles are the 1848 ...

later critiqued Locke's theory of property in his own social theory.

The human mind

The self

Locke defines ''the self'' as "that conscious thinking thing, (whatever substance, made up of whether spiritual, or material, simple, or compounded, it matters not) which is sensible, or conscious of pleasure and pain, capable of happiness or misery, and so is concerned for itself, as far as that consciousness extends". He does not, however, wholly ignore "substance", writing that "the body too goes to the making the man". In his ''Essay'', Locke explains the gradual unfolding of this conscious mind. Arguing against both theAugustinian Augustinian may refer to:

*Augustinians, members of religious orders following the Rule of St Augustine

*Augustinianism, the teachings of Augustine of Hippo and his intellectual heirs

*Someone who follows Augustine of Hippo

* Canons Regular of Sain ...

view of man as originally sinful and the Cartesian position, which holds that man innately knows basic logical propositions, Locke posits an 'empty mind', a ''tabula rasa

''Tabula rasa'' (; "blank slate") is the theory that individuals are born without built-in mental content, and therefore all knowledge comes from experience or perception. Epistemological proponents of ''tabula rasa'' disagree with the doctri ...

'', which is shaped by experience; sensations and reflections being the two sources of ''all'' of our idea

In common usage and in philosophy, ideas are the results of thought. Also in philosophy, ideas can also be mental representational images of some object. Many philosophers have considered ideas to be a fundamental ontological category of being ...

s. He states in ''An Essay Concerning Human Understanding'':