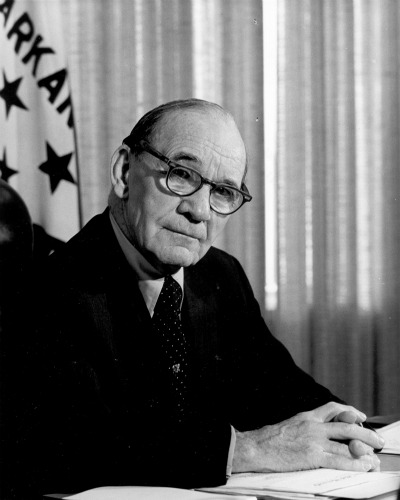

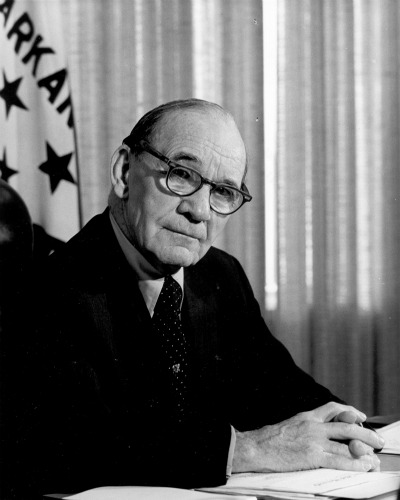

John Little McClellan on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

John Little McClellan (February 25, 1896 – November 28, 1977) was an American lawyer and a

However, in 1986 the local paper ran a series of articles suggesting that she was killed as she was obstructing the attempt by another partner in McClellan's law firm to subvert the will of one of her clients. It is unclear whether McClellan would have been aware of this matter although, since it involved matters of legal ethics and a $15m will it is probable that he was at least aware of the dispute. If so he was complicit in hiding this matter until his death.

In 1957, McClellan opposed U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower's decision to send federal troops to enforce the desegregation of Central High School in Little Rock. Prior to the sending of the troops under the command of Major General Edwin A. Walker, McClellan had expressed "regret egardingthe ... use of force by the federal government to enforce integration. I believe it to be without authority of law. I am very apprehensive that such action may precipitate more trouble than it will prevent."

McClellan and fellow Senator Robert S. Kerr of Oklahoma were the sponsors of the bill that authorized construction of the McClellan-Kerr Arkansas River Navigation System, maintained by the Army Corps of Engineers. The system transformed the once-useless

However, in 1986 the local paper ran a series of articles suggesting that she was killed as she was obstructing the attempt by another partner in McClellan's law firm to subvert the will of one of her clients. It is unclear whether McClellan would have been aware of this matter although, since it involved matters of legal ethics and a $15m will it is probable that he was at least aware of the dispute. If so he was complicit in hiding this matter until his death.

In 1957, McClellan opposed U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower's decision to send federal troops to enforce the desegregation of Central High School in Little Rock. Prior to the sending of the troops under the command of Major General Edwin A. Walker, McClellan had expressed "regret egardingthe ... use of force by the federal government to enforce integration. I believe it to be without authority of law. I am very apprehensive that such action may precipitate more trouble than it will prevent."

McClellan and fellow Senator Robert S. Kerr of Oklahoma were the sponsors of the bill that authorized construction of the McClellan-Kerr Arkansas River Navigation System, maintained by the Army Corps of Engineers. The system transformed the once-useless

Congressional Biographical Directory.

* ttp://www.tv.com/whats-my-line/episode-245/episode/95202/summary.html TV.com's Episode Guide for "What's My Line" - Episode 245 with Senator John McClellan as mystery guest.

Fearless: John L. McClellan, United States Senator - Official biography.

{{DEFAULTSORT:McClellan, John Little 1896 births 1977 deaths Arkansas lawyers People from Camden, Arkansas People from Sheridan, Arkansas Politicians from Little Rock, Arkansas Sheridan High School (Arkansas) alumni United States Army officers Democratic Party United States senators from Arkansas Democratic Party members of the United States House of Representatives from Arkansas 20th-century American politicians Lawyers from Little Rock, Arkansas 20th-century American lawyers United States Army personnel of World War I Old Right (United States) American anti-communists

segregationist

Racial segregation is the systematic separation of people into racial or other ethnic groups in daily life. Racial segregation can amount to the international crime of apartheid and a crime against humanity under the Statute of the Interna ...

politician. A member of the Democratic Party, he served as a U.S. Representative (1935–1939) and a U.S. Senator

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and power ...

(1943–1977) from Arkansas

Arkansas ( ) is a landlocked state in the South Central United States. It is bordered by Missouri to the north, Tennessee and Mississippi to the east, Louisiana to the south, and Texas and Oklahoma to the west. Its name is from the O ...

.

At the time of his death, he was the second most senior member of the Senate and chairman of the Senate Appropriations Committee

The United States Senate Committee on Appropriations is a standing committee of the United States Senate. It has jurisdiction over all discretionary spending legislation in the Senate.

The Senate Appropriations Committee is the largest committ ...

. He is the longest-serving senator in Arkansas history.

Early life and career

John Little McClellan was born on a farm nearSheridan, Arkansas

Sheridan is a city and county seat of Grant County, Arkansas, United States. The community is located deep in the forests of the Arkansas Timberlands. It sits at the intersection of US Highways 167 and 270. Early settlers were drawn to the are ...

to Isaac Scott and Belle (née Suddeth) McClellan. His parents, who were strong Democrats, named him after John Sebastian Little

John Sebastian Little (March 15, 1851 – October 29, 1916) was an American politician who served as a member of the United States House of Representatives and the 21st Governor of the U.S. state of Arkansas.

Biography

John Sebastian "Bass" Li ...

, who served as a U.S. Representative (1894–1907) and Governor of Arkansas

A governor is an administrative leader and head of a polity or political region, ranking under the head of state and in some cases, such as governors-general, as the head of state's official representative. Depending on the type of political ...

(1907). His mother died only months after his birth, and he received his early education at local public schools. At age 12, after graduating from Sheridan High School, he began studying law in his father's office.

He was admitted to the state bar in 1913, when he was only 17, after the Arkansas General Assembly

The General Assembly of Arkansas is the state legislature of the U.S. state of Arkansas. The legislature is a bicameral body composed of the upper house Arkansas Senate with 35 members, and the lower Arkansas House of Representatives with 10 ...

approved a special act waiving the normal age requirement for certification as a lawyer. As the youngest attorney in the United States, he practiced law with his father in Sheridan.

McClellan married Eula Hicks in 1913; the couple had two children, and divorced in 1921. During World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

, he served in the U.S. Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army of the United States in the U.S. Constitution.Article II, section 2, cl ...

as a first lieutenant

First lieutenant is a commissioned officer military rank in many armed forces; in some forces, it is an appointment.

The rank of lieutenant has different meanings in different military formations, but in most forces it is sub-divided into a ...

in the aviation section of the Signal Corps from 1917 to 1919. Following his military service, he moved to Malvern, where he opened a law office and served as city attorney

A city attorney is a position in city and municipal government in the United States. The city attorney is the attorney representing the municipality.

Unlike a district attorney or public defender, who usually handles criminal cases, a city att ...

(1920–26).

In 1922, he married Lucille Smith, to whom he remained married until her death in 1935; they had three children. He was prosecuting attorney of the seventh judicial district of Arkansas from 1927 to 1930.

U.S. House of Representatives

In 1934, McClellan was elected as a Democrat to the U.S. House of Representatives from Arkansas's 6th congressional district. He was re-elected to the House in 1936. In March of that year, he condemnedCBS

CBS Broadcasting Inc., commonly shortened to CBS, the abbreviation of its former legal name Columbia Broadcasting System, is an American commercial broadcast television and radio network serving as the flagship property of the CBS Entertainm ...

for airing a speech by Communist

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, ...

leader Earl Browder

Earl Russell Browder (May 20, 1891 – June 27, 1973) was an American politician, communist activist and leader of the Communist Party USA (CPUSA). Browder was the General Secretary of the CPUSA during the 1930s and first half of the 1940s.

Durin ...

, which he described as "nothing less than treason."

During his tenure in the House, he voted against President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

* President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese ...

Franklin D. Roosevelt's court-packing plan, the Gavagan anti-lynching

Lynching is an extrajudicial killing by a group. It is most often used to characterize informal public executions by a mob in order to punish an alleged transgressor, punish a convicted transgressor, or intimidate people. It can also be an ex ...

bill, and the Reorganization Act of 1937. In 1937, he wed for the third and final time, marrying Norma Myers Cheatham.

In 1938, McClellan unsuccessfully challenged first-term incumbent Hattie Caraway

Hattie Ophelia Wyatt Caraway (February 1, 1878 – December 21, 1950) was an American politician who became the first woman elected to serve a full term as a United States Senator. Caraway represented Arkansas. She was the first woman to preside ...

for the Democratic nomination for the United States Senate

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and po ...

. During the campaign, he criticized Caraway for her support for the 1937 Reorganization Act and accused her of having "improper influence" over federal employees in Arkansas. Nevertheless, he was defeated in the primary election by a margin of about 8,000 votes. He subsequently resumed the practice of law in Camden, where he joined the firm Gaughan, McClellan and Gaughan. He served as a delegate to the Democratic National Convention

The Democratic National Convention (DNC) is a series of presidential nominating conventions held every four years since 1832 by the United States Democratic Party. They have been administered by the Democratic National Committee since the 18 ...

in 1940

A calendar from 1940 according to the Gregorian calendar, factoring in the dates of Easter and related holidays, cannot be used again until the year 5280.

Events

Below, the events of World War II have the "WWII" prefix.

January

* Januar ...

(Chicago), 1944

Events

Below, the events of World War II have the "WWII" prefix.

January

* January 2 – WWII:

** Free French General Jean de Lattre de Tassigny is appointed to command French Army B, part of the Sixth United States Army Group in ...

(Chicago), and 1948

Events January

* January 1

** The General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) is inaugurated.

** The Constitution of New Jersey (later subject to amendment) goes into effect.

** The railways of Britain are nationalized, to form British ...

(Philadelphia).

U.S. Senate

In 1942, afterG. Lloyd Spencer

George Lloyd Spencer (March 27, 1893January 14, 1981) was an American politician from Arkansas. A member of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, he represented the state in the United States Senate from 1941 to 1943.

G. Lloyd S ...

decided not to seek re-election, McClellan ran for the Senate again and this time won. He served as senator from Arkansas from 1943 to 1977, when he died in office. During his tenure, he served as chairman of the Appropriations Committee and served 22 years as chairman of the Committee on Government Operations. McClellan was the longest serving United States Senator in Arkansas history. During the later part of his Senate service, Arkansas had, perhaps, the most powerful Congressional delegations with McClellan as chairman of the Senate Appropriations Committee, Wilbur Mills

Wilbur Daigh Mills (May 24, 1909 – May 2, 1992) was an American Democratic politician who represented in the United States House of Representatives from 1939 until his retirement in 1977. As chairman of the House Ways and Means Committee from ...

as chairman of the House Ways and Means Committee, Oren Harris

Oren Harris (December 20, 1903 – February 5, 1997) was a United States representative from Arkansas and a United States district judge of the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Arkansas and the United States District Court ...

as chairman of the House Commerce Committee, Senator J. William Fulbright

James William Fulbright (April 9, 1905 – February 9, 1995) was an American politician, academic, and statesman who represented Arkansas in the United States Senate from 1945 until his resignation in 1974. , Fulbright is the longest serving chair ...

as chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, Took Gathings as chairman of the House Agriculture Committee, and James William Trimble

James William Trimble (February 3, 1894 – March 10, 1972) was a Democratic member of the United States House of Representatives from Arkansas, having served from 1945 to 1967. He was the first Democrat in Arkansas since Reconstruction to los ...

as a member of the powerful House Rules Committee.

McClellan also served for eighteen years as chairman of the Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations (1955–73) and continued the hearings into subversive activities

Subversion () refers to a process by which the values and principles of a system in place are contradicted or reversed in an attempt to transform the established social order and its structures of power, authority, hierarchy, and social norms. Sub ...

at U.S. Army Signal Corps, Fort Monmouth, New Jersey

Fort Monmouth is a former installation of the Department of the Army in Monmouth County, New Jersey. The post is surrounded by the communities of Eatontown, Tinton Falls and Oceanport, New Jersey, and is located about from the Atlantic Ocean. ...

, where Soviet

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

spies Julius Rosenberg

Julius Rosenberg (May 12, 1918 – June 19, 1953) and Ethel Rosenberg (; September 28, 1915 – June 19, 1953) were American citizens who were convicted of spying on behalf of the Soviet Union. The couple were convicted of providing top-secret i ...

, Al Sarant

Alfred Epaminondas Sarant, also known as Filipp Georgievich Staros and Philip Georgievich Staros (September 26, 1918 – March 12, 1979), was an engineer and a member of the Communist party in New York City in 1944. He was part of the Rosenbe ...

and Joel Barr

Joel Barr (January 1, 1916 – August 1, 1998), also Iozef Veniaminovich Berg and Joseph Berg, was part of the Soviet Atomic Spy Ring.

Background

Born Joyel Barr in New York City, to immigrant parents of Ukrainian Jewish origin. He attended C ...

all worked in the 1940s. He was a participant in the famous Army-McCarthy Hearings and led a Democratic walkout of that subcommittee in protest of Senator Joseph McCarthy

Joseph Raymond McCarthy (November 14, 1908 – May 2, 1957) was an American politician who served as a Republican United States Senate, U.S. Senator from the state of Wisconsin from 1947 until his death in 1957. Beginning in 1950, McCarth ...

's conduct in those hearings.

McClellan appeared in the 2005 movie '' Good Night, and Good Luck'' in footage from the actual hearings. McClellan led two other investigations which were both televised uncovering spectacular law-breaking and corruption. The first, under the United States Senate Select Committee on Improper Activities in Labor and Management

The United States Senate Select Committee on Improper Activities in Labor and Management (also known as the McClellan Committee) was a select committee created by the United States Senate on January 30, 1957,Hilty, James. ''Robert Kennedy: Broth ...

, also known as the McClellan Committee, investigated union corruption and centered on Jimmy Hoffa

James Riddle Hoffa (born February 14, 1913 – disappeared July 30, 1975; declared dead July 30, 1982) was an American labor union leader who served as the president of the International Brotherhood of Teamsters (IBT) from 1957 until 1971.

...

and lasted from January 1957 to March 1960.

In April 1961, during a Senate Investigations Committee hearing, contractor Henry Gable asserted that Communists would not be able to do the same amount of damage to the American missile effort as done by labor at Cape Canaveral

, image = cape canaveral.jpg

, image_size = 300

, caption = View of Cape Canaveral from space in 1991

, map = Florida#USA

, map_width = 300

, type = Cape

, map_caption = Location in Florida

, location ...

. McClellan suggested that the comments bordered on subversion and called for more testimony from the unions.

The second in 1964, known as the Valachi hearings, investigated the operations of organized crime and featured the testimony of Joseph Valachi

Joseph Michael Valachi (September 22, 1904 – April 3, 1971) was an American mobster in the Genovese crime family who is notable as the first member of the Italian-American Mafia to acknowledge its existence publicly in 1963. He is credited wit ...

, the first American mafia figure to testify about the activities of organized crime. He continued his efforts against organized crime, supplying the political influence for the anti-organized crime law Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act

The Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations (RICO) Act is a United States federal law that provides for extended criminal penalties and a civil cause of action for acts performed as part of an ongoing criminal organization.

RICO was en ...

(RICO) until 1973 when he switched to investigating political subversion. During this period, he hired Robert F. Kennedy as chief counsel and vaulted him into the national spotlight. He investigated numerous cases of government corruption including numerous defense contractors and Texas

Texas (, ; Spanish: ''Texas'', ''Tejas'') is a state in the South Central region of the United States. At 268,596 square miles (695,662 km2), and with more than 29.1 million residents in 2020, it is the second-largest U.S. state by ...

financier Billie Sol Estes

Billie Sol Estes (January 10, 1925 – May 14, 2013) was an American businessman and financier best known for his involvement in a business fraud scandal that complicated his ties to friend and future U.S. President Lyndon Johnson.

Early life

Es ...

.

In 1956, McClellan was one of 82 representatives and 19 senators who signed the Southern Manifesto

The Declaration of Constitutional Principles (known informally as the Southern Manifesto) was a document written in February and March 1956, during the 84th United States Congress, in opposition to racial integration of public places. The manif ...

in opposition to the 1954 U.S. Supreme Court decision '' Brown v. Board of Education'' and racial integration

Racial integration, or simply integration, includes desegregation (the process of ending systematic racial segregation). In addition to desegregation, integration includes goals such as leveling barriers to association, creating equal opportuni ...

.

One of McClellan's law partners prior to his Senate service, Maud Crawford, went missing in March 1957 in Camden, Arkansas

Camden is a city in and the county seat of Ouachita County in the south-central part of the U.S. state of Arkansas. The city is located about 100 miles south of Little Rock. Situated on bluffs overlooking the Ouachita River, the city developed ...

. There had been speculation that she had been kidnapped by the Mafia

"Mafia" is an informal term that is used to describe criminal organizations that bear a strong similarity to the original “Mafia”, the Sicilian Mafia and Italian Mafia. The central activity of such an organization would be the arbitration of d ...

in an attempt to intimidate McClellan, but no ransom note was ever forthcoming. The disappearance, which remains unsolved, received international attention.

However, in 1986 the local paper ran a series of articles suggesting that she was killed as she was obstructing the attempt by another partner in McClellan's law firm to subvert the will of one of her clients. It is unclear whether McClellan would have been aware of this matter although, since it involved matters of legal ethics and a $15m will it is probable that he was at least aware of the dispute. If so he was complicit in hiding this matter until his death.

In 1957, McClellan opposed U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower's decision to send federal troops to enforce the desegregation of Central High School in Little Rock. Prior to the sending of the troops under the command of Major General Edwin A. Walker, McClellan had expressed "regret egardingthe ... use of force by the federal government to enforce integration. I believe it to be without authority of law. I am very apprehensive that such action may precipitate more trouble than it will prevent."

McClellan and fellow Senator Robert S. Kerr of Oklahoma were the sponsors of the bill that authorized construction of the McClellan-Kerr Arkansas River Navigation System, maintained by the Army Corps of Engineers. The system transformed the once-useless

However, in 1986 the local paper ran a series of articles suggesting that she was killed as she was obstructing the attempt by another partner in McClellan's law firm to subvert the will of one of her clients. It is unclear whether McClellan would have been aware of this matter although, since it involved matters of legal ethics and a $15m will it is probable that he was at least aware of the dispute. If so he was complicit in hiding this matter until his death.

In 1957, McClellan opposed U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower's decision to send federal troops to enforce the desegregation of Central High School in Little Rock. Prior to the sending of the troops under the command of Major General Edwin A. Walker, McClellan had expressed "regret egardingthe ... use of force by the federal government to enforce integration. I believe it to be without authority of law. I am very apprehensive that such action may precipitate more trouble than it will prevent."

McClellan and fellow Senator Robert S. Kerr of Oklahoma were the sponsors of the bill that authorized construction of the McClellan-Kerr Arkansas River Navigation System, maintained by the Army Corps of Engineers. The system transformed the once-useless Arkansas River

The Arkansas River is a major tributary of the Mississippi River. It generally flows to the east and southeast as it traverses the U.S. states of Colorado, Kansas, Oklahoma, and Arkansas. The river's source basin lies in the western United ...

into a major transportation route and water source.

Although his Select Committee on Improper Activities in Labor and Management had already been dissolved by 1960, McClellan began a related three-year investigation in 1963 through the Permanent Investigations Senate Subcommittee into the union benefit plans of labor leader George Barasch

George Barasch (December 10, 1910 – August 11, 2013) was a US union labor leader who led both the Allied Trades Council and Teamsters Local 815 (New York City), representing a combined total of 11,000 members.

He was the first labor leader to c ...

, alleging misuse and diversion of $4,000,000 of benefit funds.

McClellan's notable failure to find any legal wrongdoing led to his introduction of several pieces of new legislation including his own bill on October 12, 1965 setting new fiduciary standards for plan trustees. Senator Jacob K. Javits

Jacob Koppel Javits ( ; May 18, 1904 – March 7, 1986) was an American lawyer and politician. During his time in politics, he represented the state of New York in both houses of the United States Congress. A member of the Republican Party, he a ...

(R-NY) introduced bills in 1965 and 1967 increasing regulation on welfare and pension funds to limit the control of plan trustees and administrators. Provisions from all three bills ultimately evolved into the guidelines enacted in the Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974 (ERISA).

In his last Senate election in 1972, McClellan defeated fellow Democrat David Hampton Pryor

David Hampton Pryor (born August 29, 1934) is an American politician and former Democratic United States Representative and United States Senator from the State of Arkansas. Pryor also served as the 39th Governor of Arkansas from 1975 to 1979 ...

, then a U.S. representative, by a narrow 52-48 percent margin in the party runoff. He then defeated the only Republican

Republican can refer to:

Political ideology

* An advocate of a republic, a type of government that is not a monarchy or dictatorship, and is usually associated with the rule of law.

** Republicanism, the ideology in support of republics or agains ...

who ever ran against him, Wayne H. Babbitt, then a North Little Rock

North Little Rock is a city in Pulaski County, Arkansas, across the Arkansas from Little Rock in the central part of the state. The population was 64,591 at the 2020 census. In 2019 the estimated population was 65,903, making it the seventh-mo ...

veterinarian

A veterinarian (vet), also known as a veterinary surgeon or veterinary physician, is a medical professional who practices veterinary medicine. They manage a wide range of health conditions and injuries in non-human animals. Along with this, vet ...

, by a margin of 61-39 percent. Pryor was elected to the seat in 1978, three weeks before the first anniversary of McClellan's death.

In 1974, McClellan informed President Gerald R. Ford, Jr.

Gerald Rudolph Ford Jr. ( ; born Leslie Lynch King Jr.; July 14, 1913December 26, 2006) was an American politician who served as the 38th president of the United States from 1974 to 1977. He was the only president never to have been elected ...

, that he would not support the renomination of Republican Lynn A. Davis as U.S. marshal for the Eastern District of Arkansas based in Little Rock. McClellan claimed that Davis, who as the temporary head of the Arkansas state police had conducted sensational raids against mobsters in Hot Springs

A hot spring, hydrothermal spring, or geothermal spring is a spring produced by the emergence of geothermally heated groundwater onto the surface of the Earth. The groundwater is heated either by shallow bodies of magma (molten rock) or by circ ...

, was too partisan for the position. In an effort to appease the powerful McClellan, Ford moved to replace Davis with Len E. Blaylock

Len or LEN may refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Len (given name), a list of people and fictional characters

* Lén, a character from Irish mythology

* Alex Len (born 1993), Ukrainian basketball player

* Mr. Len, American hip hop DJ

*Le ...

of Perry County Perry County may refer to:

United States

* Perry County, Alabama

* Perry County, Arkansas

*Perry County, Illinois

* Perry County, Indiana

* Perry County, Kentucky

* Perry County, Mississippi

* Perry County, Missouri

*Perry County, Ohio

*Perr ...

, the mild-mannered Republican gubernatorial nominee in the 1972 campaign against Dale Bumpers.

In 1977, McClellan was one of five Democrats to vote against the nomination of F. Ray Marshall as United States Secretary of Labor

The United States Secretary of Labor is a member of the Cabinet of the United States, and as the head of the United States Department of Labor, controls the department, and enforces and suggests laws involving unions, the workplace, and all ot ...

.

Personal life

McClellan's second wife died ofspinal meningitis

Meningitis is acute or chronic inflammation of the protective membranes covering the brain and spinal cord, collectively called the meninges. The most common symptoms are fever, headache, and neck stiffness. Other symptoms include confusi ...

in 1935 and his son Max died of the same disease in 1943 while serving in Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent, after Asia in both cases. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 6% of Earth's total surface area ...

during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

. His son, John L. Jr., died in 1949 in an automobile accident, and his son James H. died in a plane crash in 1958. Both men were members of the Xi chapter of Kappa Sigma

Kappa Sigma (), commonly known as Kappa Sig, is an American collegiate social fraternity founded at the University of Virginia in 1869. Kappa Sigma is one of the five largest international fraternities with currently 318 active chapters and col ...

fraternity at the University of Arkansas. To honor their two fallen brothers, the Chapter initiated Senator McClellan into Kappa Sigma

Kappa Sigma (), commonly known as Kappa Sig, is an American collegiate social fraternity founded at the University of Virginia in 1869. Kappa Sigma is one of the five largest international fraternities with currently 318 active chapters and col ...

in 1965.

McClellan died in his sleep on November 28, 1977, in Little Rock, Arkansas

( The "Little Rock")

, government_type = Council-manager

, leader_title = Mayor

, leader_name = Frank Scott Jr.

, leader_party = D

, leader_title2 = Council

, leader_name2 ...

, following surgery to implant a pacemaker.State Capitol News Report; Benton Courier; Benton, Arkansas; Page 2; December 1, 1977 He was buried at Roselawn Memorial Park in Little Rock. A VA Hospital

Veterans' health care in the United States is separated geographically into 19 regions (numbered 1, 2, 4-10, 12 and 15–23) In January 2002, the Veterans Health Administration announced the merger of VISNs 13 and 14 to create a new, combined netw ...

in Little Rock is named in his honor. Ouachita Baptist University is the repository for his official papers.

See also

*List of United States Congress members who died in office (1950–1999)

The following is a list of United States senators and representatives who died of natural or accidental causes, or who killed themselves, while serving their terms between 1950 and 1999. For a list of members of Congress who were killed while in ...

References

External links

*Congressional Biographical Directory.

* ttp://www.tv.com/whats-my-line/episode-245/episode/95202/summary.html TV.com's Episode Guide for "What's My Line" - Episode 245 with Senator John McClellan as mystery guest.

Fearless: John L. McClellan, United States Senator - Official biography.

{{DEFAULTSORT:McClellan, John Little 1896 births 1977 deaths Arkansas lawyers People from Camden, Arkansas People from Sheridan, Arkansas Politicians from Little Rock, Arkansas Sheridan High School (Arkansas) alumni United States Army officers Democratic Party United States senators from Arkansas Democratic Party members of the United States House of Representatives from Arkansas 20th-century American politicians Lawyers from Little Rock, Arkansas 20th-century American lawyers United States Army personnel of World War I Old Right (United States) American anti-communists