John Breckinridge (U.S. Attorney General) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

John Breckinridge (December 2, 1760 – December 14, 1806) was a lawyer, slave-owning planter, soldier, and politician in the

On June 28, 1785, Breckinridge married Mary Hopkins ("Polly") Cabell, daughter of Joseph Cabell, a member of the Cabell political family. Polly's

On June 28, 1785, Breckinridge married Mary Hopkins ("Polly") Cabell, daughter of Joseph Cabell, a member of the Cabell political family. Polly's

In November 1794, the Democratic-Republicans nominated Breckinridge to succeed

In November 1794, the Democratic-Republicans nominated Breckinridge to succeed

Letters between Nicholas and Jefferson indicate a different series of events.Harrison in ''John Breckinridge: Jeffersonian Republican'', p. 76. In a letter dated October 4, 1798, Nicholas informed Jefferson that he had given "a copy of the resolutions you sent me" to Breckinridge, who would introduce them in Kentucky. The letter also indicated that this was a deviation from the original plan to deliver the draft to a legislator in

Letters between Nicholas and Jefferson indicate a different series of events.Harrison in ''John Breckinridge: Jeffersonian Republican'', p. 76. In a letter dated October 4, 1798, Nicholas informed Jefferson that he had given "a copy of the resolutions you sent me" to Breckinridge, who would introduce them in Kentucky. The letter also indicated that this was a deviation from the original plan to deliver the draft to a legislator in

Before an invasion became necessary, U.S. ambassadors learned that Spain had ceded Louisiana to France via the

Before an invasion became necessary, U.S. ambassadors learned that Spain had ceded Louisiana to France via the

The Democratic-Republican congressional caucus convened February 25, 1804.Harrison in "John Breckinridge and the Vice-Presidency", p. 158. Contrary to previous conventions, the proceedings were open and formal. Afraid that taking vice presidential nominations from the floor would precipitate divisive oratory, chairman Stephen Bradley called for open balloting for the nomination. New York's George Clinton received a majority with 67 votes; Breckinridge garnered 20 votes, mostly from western delegates, and the remaining votes were scattered among 4 other candidates. Historian

The Democratic-Republican congressional caucus convened February 25, 1804.Harrison in "John Breckinridge and the Vice-Presidency", p. 158. Contrary to previous conventions, the proceedings were open and formal. Afraid that taking vice presidential nominations from the floor would precipitate divisive oratory, chairman Stephen Bradley called for open balloting for the nomination. New York's George Clinton received a majority with 67 votes; Breckinridge garnered 20 votes, mostly from western delegates, and the remaining votes were scattered among 4 other candidates. Historian

Remonstrance of the Citizens West of the Mountains to the President and Congress of the United States

', a pamphlet written by Breckinridge urging the federal government to secure unrestricted navigation of the Mississippi River {{DEFAULTSORT:Breckinridge, John 1760 births 1806 deaths American racehorse owners and breeders Breckinridge family College of William & Mary alumni 19th-century deaths from tuberculosis Democratic-Republican Party United States senators Tuberculosis deaths in Kentucky Jefferson administration cabinet members Kentucky Attorneys General Kentucky Democratic-Republicans Kentucky lawyers Members of the Virginia House of Delegates People from Augusta County, Virginia Speakers of the Kentucky House of Representatives United States Attorneys General United States senators from Kentucky Virginia lawyers Virginia militiamen in the American Revolution Washington and Lee University alumni People from Botetourt County, Virginia 18th-century American lawyers 19th-century American lawyers 18th-century American politicians 19th-century American politicians American slave owners United States senators who owned slaves

U.S. state

In the United States, a state is a constituent political entity, of which there are 50. Bound together in a political union, each state holds governmental jurisdiction over a separate and defined geographic territory where it shares its sove ...

s of Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth are ...

and Kentucky

Kentucky ( , ), officially the Commonwealth of Kentucky, is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States and one of the states of the Upper South. It borders Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio to the north; West Virginia and Virginia ...

. He served several terms each in the state legislatures of Virginia and Kentucky

Kentucky ( , ), officially the Commonwealth of Kentucky, is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States and one of the states of the Upper South. It borders Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio to the north; West Virginia and Virginia ...

before legislators elected him to the U.S. Senate. He also served as United States Attorney General

The United States attorney general (AG) is the head of the United States Department of Justice, and is the chief law enforcement officer of the federal government of the United States. The attorney general serves as the principal advisor to the p ...

during the second term of President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

* President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese ...

Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 18 ...

. He is the progenitor of Kentucky's Breckinridge political family and the namesake of Breckinridge County, Kentucky

Breckinridge County is a county located in the Commonwealth of Kentucky. As of the 2020 census, the population was 20,432. Its county seat is Hardinsburg, Kentucky. The county was named for John Breckinridge (1760–1806), a Kentucky Attorney ...

.

Breckinridge's father was landowner and colonel in the local Virginia militia who married into the Preston political family. Breckinridge attended the William and Mary College intermittently between 1780 and 1784; his attendance was interrupted by the Revolutionary War and he three times won election to the Virginia House of Delegates

The Virginia House of Delegates is one of the two parts of the Virginia General Assembly, the other being the Senate of Virginia. It has 100 members elected for terms of two years; unlike most states, these elections take place during odd-number ...

. One of the youngest members of that (part-time) body, this allowed him to meet many prominent politicians. In 1785, he married "Polly" Cabell, a member of the Cabell political family. Despite making his legal and farming activities, letters from relatives in Kentucky convinced him to move to the western frontier. He established "Cabell's Dale", his plantation, near Lexington, Kentucky

Lexington is a city in Kentucky, United States that is the county seat of Fayette County. By population, it is the second-largest city in Kentucky and 57th-largest city in the United States. By land area, it is the country's 28th-largest ...

, in 1793.

Breckinridge continued his legal and political career and was appointed as the state's attorney general

In most common law jurisdictions, the attorney general or attorney-general (sometimes abbreviated AG or Atty.-Gen) is the main legal advisor to the government. The plural is attorneys general.

In some jurisdictions, attorneys general also have exec ...

soon after arriving. In November 1797, he resigned to campaign, then won election to the Kentucky House of Representatives

The Kentucky House of Representatives is the lower house of the Kentucky General Assembly. It is composed of 100 Representatives elected from single-member districts throughout the Commonwealth. Not more than two counties can be joined to form a ...

. As a legislator, Breckinridge secured passage of a more humane criminal code that abolished the death penalty

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty, is the state-sanctioned practice of deliberately killing a person as a punishment for an actual or supposed crime, usually following an authorized, rule-governed process to conclude that ...

for all offenses except first-degree murder

Murder is the unlawful killing of another human without justification or valid excuse, especially the unlawful killing of another human with malice aforethought. ("The killing of another person without justification or excuse, especially t ...

. On a 1798 trip back to Virginia, an intermediary gave him Thomas Jefferson's Kentucky Resolutions

The Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions were political statements drafted in 1798 and 1799 in which the Kentucky and Virginia legislatures took the position that the federal Alien and Sedition Acts were unconstitutional. The resolutions argued t ...

, which denounced the Alien and Sedition Acts

The Alien and Sedition Acts were a set of four laws enacted in 1798 that applied restrictions to immigration and speech in the United States. The Naturalization Act increased the requirements to seek citizenship, the Alien Friends Act allowed th ...

. At Jefferson's request, Breckinridge assumed credit for the modified resolutions he shepherded through the Kentucky General Assembly

The Kentucky General Assembly, also called the Kentucky Legislature, is the state legislature of the U.S. state of Kentucky. It comprises the Kentucky Senate and the Kentucky House of Representatives.

The General Assembly meets annually in ...

; Jefferson's authorship was not discovered until after Breckinridge's death. Although Breckinridge opposed calling a constitutional convention for the new state in 1799 he was elected as a delegate. Due to his influence, the state's government remained comparatively aristocratic, maintaining protections for slavery

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

and limiting the power of the electorate. Called the father of the resultant constitution, he emerged from the convention as the acknowledged leader of the state's Democratic-Republican Party

The Democratic-Republican Party, known at the time as the Republican Party and also referred to as the Jeffersonian Republican Party among other names, was an American political party founded by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison in the earl ...

and fellow delegates elected him Speaker of the Kentucky House of Representatives in 1799 and 1800.

Elected to the U.S. Senate in 1800, Breckinridge functioned as Jefferson's floor leader, guiding administration bills through the chamber that was narrowly controlled by his party. Residents of the western frontier called for his nomination as vice president

A vice president, also director in British English, is an officer in government or business who is below the president (chief executive officer) in rank. It can also refer to executive vice presidents, signifying that the vice president is on ...

in 1804, but Jefferson appointed him as U.S. Attorney General in 1805 instead. He was the first cabinet-level official from the West but had little impact before his death from tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB) is an infectious disease usually caused by '' Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can also affect other parts of the body. Most infections show no symptoms, ...

on December 14, 1806, at the age of 46.

Early life and family

John Breckinridge's grandfather, Alexander Breckenridge, immigrated from Ireland toBucks County, Pennsylvania

Bucks County is a county in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. As of the 2020 census, the population was 646,538, making it the fourth-most populous county in Pennsylvania. Its county seat is Doylestown. The county is named after the English ...

, around 1728, while the Breckinridge family originated in Ayrshire

Ayrshire ( gd, Siorrachd Inbhir Àir, ) is a historic county and registration county in south-west Scotland, located on the shores of the Firth of Clyde. Its principal towns include Ayr, Kilmarnock and Irvine and it borders the counties of ...

, Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a border with England to the southeast and is otherwise surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean to ...

, before migrating to Ulster

Ulster (; ga, Ulaidh or ''Cúige Uladh'' ; sco, label= Ulster Scots, Ulstèr or ''Ulster'') is one of the four traditional Irish provinces. It is made up of nine counties: six of these constitute Northern Ireland (a part of the United Kin ...

(possibly County Antrim

County Antrim (named after the town of Antrim, ) is one of six counties of Northern Ireland and one of the thirty-two counties of Ireland. Adjoined to the north-east shore of Lough Neagh, the county covers an area of and has a population ...

or County Londonderry

County Londonderry ( Ulster-Scots: ''Coontie Lunnonderrie''), also known as County Derry ( ga, Contae Dhoire), is one of the six counties of Northern Ireland, one of the thirty two counties of Ireland and one of the nine counties of Ulster. ...

) probably in the late 17th century.Davis notes that John Breckinridge changed the spelling of the family name for unknown reasons during his time in the Virginia House of Delegates between 1781 and 1784. See Davis, p. 5. In 1740, the family moved to Augusta County, Virginia

Augusta County is a county in the Shenandoah Valley on the western edge of the Commonwealth of Virginia. The second-largest county of Virginia by total area, it completely surrounds the independent cities of Staunton and Waynesboro. Its count ...

, near the city of Staunton and Alexander died there in 1743.

John Breckinridge was born in Augusta County on December 2, 1760, the second of six children of Robert Breckenridge and his second wife, Lettice (Preston) Breckenridge.Klotter in ''The Breckinridges of Kentucky'', p. 8. His mother was the daughter of John Preston of Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth are ...

's Preston political family."John Breckinridge". ''Dictionary of American Biography''. Robert Breckinridge had two children by a previous marriage, and through one of these half-brothers that John Breckinridge was uncle to future Congressman

A Member of Congress (MOC) is a person who has been appointed or elected and inducted into an official body called a congress, typically to represent a particular constituency in a legislature. The term member of parliament (MP) is an equivalen ...

James D. Breckinridge

James Douglas Breckinridge (1781 – May 6, 1849) was a U.S. Representative from Kentucky. He was a member of the noted Breckinridge family.

Breckinridge was born in Woodville, Kentucky, in 1781. He attended Washington College (now Washing ...

.The paternity of James D. Breckinridge is disputed; see ''The Breckinridges of Kentucky'', p. 8. A veteran of the French and Indian War

The French and Indian War (1754–1763) was a theater of the Seven Years' War, which pitted the North American colonies of the British Empire against those of the French, each side being supported by various Native American tribes. At the st ...

, Robert Breckinridge had farmed as well as served first as Augusta County's under-sheriff, then as sheriff, then justice of the peace

A justice of the peace (JP) is a judicial officer of a lower or '' puisne'' court, elected or appointed by means of a commission ( letters patent) to keep the peace. In past centuries the term commissioner of the peace was often used with the s ...

. Soon after John Breckinridge's birth, the family moved southward along the Wilderness Road

The Wilderness Road was one of two principal routes used by colonial and early national era settlers to reach Kentucky from the East. Although this road goes through the Cumberland Gap into southern Kentucky and northern Tennessee, the other (m ...

to Botetourt County

Botetourt County ( ) is a US county that lies in the Roanoke Region of the Commonwealth of Virginia. Located in the mountainous portion of the state, the county is bordered by two major ranges, the Blue Ridge Mountains and the Appalachian Mount ...

where Robert Breckinridge farmed, as well as became a constable and justice of the peace, and served in the local militia. He died in 1773, leaving 12-year-old John of land, one slave, and half-ownership of another slave.Klotter in ''The Breckiridges of Kentucky'', p. 9.

Breckinridge received a private education suitable to his class, possibly including Augusta Academy (now Washington and Lee University

, mottoeng = "Not Unmindful of the Future"

, established =

, type = Private liberal arts university

, academic_affiliations =

, endowment = $2.092 billion (2021)

, president = William C. Dudley

, provost = Lena Hill

, city = Lexington ...

), but any records containing this information have been lost. After his father's death, the younger Breckinridge helped support the family by selling whiskey, brandy, and hemp.Harrison in "A Young Virginian", p. 21. He learned surveying

Surveying or land surveying is the technique, profession, art, and science of determining the terrestrial two-dimensional or three-dimensional positions of points and the distances and angles between them. A land surveying professional is ...

from his uncle, William Preston, and between 1774 and 1779, held a clerical job in the Botetourt County

Botetourt County ( ) is a US county that lies in the Roanoke Region of the Commonwealth of Virginia. Located in the mountainous portion of the state, the county is bordered by two major ranges, the Blue Ridge Mountains and the Appalachian Mount ...

land office in Fincastle. Preston sought opportunities for his nephew to attend private schools alongside his sons, but Breckinridge's other responsibilities interfered with his attendance.Harrison in ''John Breckinridge: Jeffersonian Republican'', p. 5. Preston also nominated Breckinridge as deputy surveyor of Montgomery County, a position he accepted after passing the requisite exam on February 1, 1780.Harrison in ''John Breckinridge: Jeffersonian Republican'', p. 6. Later that year, he joined his cousin, future Kentucky Senator

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the el ...

John Brown, at William and Mary College (now College of William & Mary

The College of William & Mary (officially The College of William and Mary in Virginia, abbreviated as William & Mary, W&M) is a public research university in Williamsburg, Virginia. Founded in 1693 by letters patent issued by King William I ...

).Harrison in "A Young Virginian", p. 22. The instructors who influenced him most were Reverend James Madison and George Wythe

George Wythe (; December 3, 1726 – June 8, 1806) was an American academic, scholar and judge who was one of the Founding Fathers of the United States. The first of the seven signatories of the United States Declaration of Independence from ...

.

The Revolutionary War forced William and Mary to close in 1781, and during various times during the conflict British, French, and American troops used them as barracks while controlling the surrounding area.Harrison in ''John Breckinridge: Jeffersonian Republican'', p. 7. Although William C. Davis records that Breckinridge had previously served as an ensign

An ensign is the national flag flown on a vessel to indicate nationality. The ensign is the largest flag, generally flown at the stern (rear) of the ship while in port. The naval ensign (also known as war ensign), used on warships, may be diffe ...

in the Botetourt County militia, Harrison notes that the most reliable records of Virginians' military service do not indicate his participation in the Revolutionary War, and less reliable sources mention him as a subaltern in the Virginia militia.Davis, p. 4.Harrison in ''John Breckinridge: Jeffersonian Republican'', p. 20. If Breckinridge served, Harrison speculates that such occurred in one or two short 1780 militia campaigns supporting Nathanael Greene

Nathanael Greene (June 19, 1786, sometimes misspelled Nathaniel) was a major general of the Continental Army in the American Revolutionary War. He emerged from the war with a reputation as General George Washington's most talented and dependab ...

's army in southwest Virginia.Harrison in ''John Breckinridge: Jeffersonian Republican'', p. 9.

Early political career

Although he had not sought the office and was not old enough to serve, Botetourt County voters twice elected Breckinridge to represent them part-time as one of the western county's representatives in theVirginia House of Delegates

The Virginia House of Delegates is one of the two parts of the Virginia General Assembly, the other being the Senate of Virginia. It has 100 members elected for terms of two years; unlike most states, these elections take place during odd-number ...

in late 1780. Though without documentary support, some claim fellow delegates twice refused Breckinridge his seat because of his age, but his constituents reelected him each time, and he was seated the third time.Harrison in ''John Breckinridge: Jeffersonian Republican'', p. 10. His legislative colleagues included Patrick Henry

Patrick Henry (May 29, 1736June 6, 1799) was an American attorney, planter, politician and orator known for declaring to the Second Virginia Convention (1775): " Give me liberty, or give me death!" A Founding Father, he served as the first a ...

, Benjamin Harrison

Benjamin Harrison (August 20, 1833March 13, 1901) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 23rd president of the United States from 1889 to 1893. He was a member of the Harrison family of Virginia–a grandson of the ninth pr ...

, John Tyler

John Tyler (March 29, 1790 – January 18, 1862) was the tenth president of the United States, serving from 1841 to 1845, after briefly holding office as the tenth vice president in 1841. He was elected vice president on the 1840 Whig tick ...

, John Taylor of Caroline

John Taylor (December 19, 1753August 21, 1824), usually called John Taylor of Caroline, was a politician and writer. He served in the Virginia House of Delegates (1779–81, 1783–85, 1796–1800) and in the United States Senate (1792–94, 1803 ...

, George Nicholas, Daniel Boone

Daniel Boone (September 26, 1820) was an American pioneer and frontiersman whose exploits made him one of the first folk heroes of the United States. He became famous for his exploration and settlement of Kentucky, which was then beyond the we ...

, and Benjamin Logan

Benjamin Logan (May 1, 1743 – December 11, 1802) was an American pioneer, soldier, and politician from Virginia, then Shelby County, Kentucky. As colonel of the Kentucky County, Virginia militia during the American Revolutionary War, he was s ...

.Harrison in "A Young Virginian", p. 24.

Prevented by British soldiers from meeting at Williamsburg, the House convened May 7, 1781, in Richmond

Richmond most often refers to:

* Richmond, Virginia, the capital of Virginia, United States

* Richmond, London, a part of London

* Richmond, North Yorkshire, a town in England

* Richmond, British Columbia, a city in Canada

* Richmond, Californi ...

, but failed to achieve a quorum

A quorum is the minimum number of members of a deliberative assembly (a body that uses parliamentary procedure, such as a legislature) necessary to conduct the business of that group. According to '' Robert's Rules of Order Newly Revised'', the ...

. Because of British General Charles Cornwallis

Charles Cornwallis, 1st Marquess Cornwallis, (31 December 1738 – 5 October 1805), styled Viscount Brome between 1753 and 1762 and known as the Earl Cornwallis between 1762 and 1792, was a British Army general and official. In the United S ...

' May 10 advance on that city, the legislators adjourned to Charlottesville

Charlottesville, colloquially known as C'ville, is an independent city in the Commonwealth of Virginia. It is the county seat of Albemarle County, which surrounds the city, though the two are separate legal entities. It is named after Queen ...

on May 24. Breckinridge arrived in Charlottesville on May 28; a quorum was present to conduct legislative business through June 3. The next morning, Jack Jouett

John Jouett Jr. (December 7, 1754 – March 1, 1822) was an American farmer and politician in Virginia and Kentucky best known for his ride during the American Revolution. Sometimes called the "Paul Revere of the South", Jouett rode to warn Tho ...

rode into the city, warning the legislators that 250 light cavalrymen under Banastre Tarleton

Sir Banastre Tarleton, 1st Baronet, GCB (21 August 175415 January 1833) was a British general and politician. He is best known as the lieutenant colonel leading the British Legion at the end of the American Revolution. He later served in Portu ...

were approaching. Legislators quickly adjourned to Staunton and fled for their horses. Days later, they completed the session's business there. Breckinridge stayed at his mother's house between sessions, rejoining the legislature in Richmond in November 1781. Much of the session consisted of adopting resolutions of thanks for individuals who had made that city safe by defeating Cornwallis at Yorktown.Harrison in ''John Breckinridge: Jeffersonian Republican'', p. 11.

Financial difficulties prevented Breckinridge's return to college.Klotter in ''The Breckinridges of Kentucky''. He did not seek reelection in 1782; instead, he spent a year earning money by surveying, and was reelected to the House of Delegates in 1783, joining his legislative colleagues in May. He also joined the Constitutional Society of Virginia; fellow society members included future U.S. presidents James Madison

James Madison Jr. (March 16, 1751June 28, 1836) was an American statesman, diplomat, and Founding Father. He served as the fourth president of the United States from 1809 to 1817. Madison is hailed as the "Father of the Constitution" for h ...

and James Monroe

James Monroe ( ; April 28, 1758July 4, 1831) was an American statesman, lawyer, diplomat, and Founding Father who served as the fifth president of the United States from 1817 to 1825. A member of the Democratic-Republican Party, Monroe was ...

.Klotter in ''The Breckinridges of Kentucky'', p. 11. The House adjourned June 28, 1783, and Breckinridge returned to William and Mary, studying through the end of the year, excepting the legislative session in November and December.Harrison in "A Young Virginian", p. 25. With the war over, he urged that no economic or political penalties be imposed on former Loyalists

Loyalism, in the United Kingdom, its overseas territories and its former colonies, refers to the allegiance to the British crown or the United Kingdom. In North America, the most common usage of the term refers to loyalty to the British Cro ...

. In contrast to his later political views, he desired a stronger central government than provided for in the Articles of Confederation

The Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union was an agreement among the 13 Colonies of the United States of America that served as its first frame of government. It was approved after much debate (between July 1776 and November 1777) by ...

; he argued that the national government could not survive unless it could tax its citizens, a power it did not have under the Articles.Harrison in "John Breckinridge: Western Statesman", p. 138.

Financial problems caused Breckinridge to leave William and Mary after the spring semester in 1784.Harrison in "A Young Virginian", p. 23. Because of his studies earlier in the year, he had no time to campaign for reelection to the House of Delegates, so he asked his brother Joseph and his cousin John Preston to campaign on his behalf.Harrison, in "A Young Virginian", p. 26. Initially, his prospects seemed favorable, but he was beaten by future Virginia Congressman George Hancock. After the defeat, voters from Montgomery County – where Breckinridge had previously been a surveyor – chose him to represent them in the House. As a Virginia legislator, Breckinridge served on the prestigious committees on Propositions and Grievances, Courts of Justice, Religion, and Investigation of the Land Offices. His fellow committee members included Henry Tazewell, Carter Henry Harrison, Edward Carrington, Spencer Roane, John Marshall

John Marshall (September 24, 1755July 6, 1835) was an American politician and lawyer who served as the fourth Chief Justice of the United States from 1801 until his death in 1835. He remains the longest-serving chief justice and fourth-longes ...

, Richard Bland Lee, and Wilson Cary Nicholas.Harrison in ''John Breckinridge: Jeffersonian Republican'', p. 13. Inspired by his legislative service, he spent the summer between legislative sessions studying to become a lawyer.Harrison in "A Young Virginian", p. 27. The legislative session focused on domestic issues like whether Virginia should establish a tax to benefit religion in the state.Harrison in ''John Breckinridge: Jeffersonian Republican'', p. 14. Breckinridge was not associated with any denomination, and his writings indicate that he was opposed to such a tax.Harrison in ''John Breckinridge: Jeffersonian Republican'', p. 15. Instead, he and James Madison secured approval of a religious liberty bill first proposed by Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 18 ...

over five years earlier. The legislature rose on January 7, 1785, and Breckinridge was admitted to the bar

An admission to practice law is acquired when a lawyer receives a license to practice law. In jurisdictions with two types of lawyer, as with barristers and solicitors, barristers must gain admission to the bar whereas for solicitors there are dist ...

later that year, beginning practice in Charlottesville."Breckinridge, John", ''Biographical Directory of the United States Congress''.

Marriage and children

On June 28, 1785, Breckinridge married Mary Hopkins ("Polly") Cabell, daughter of Joseph Cabell, a member of the Cabell political family. Polly's

On June 28, 1785, Breckinridge married Mary Hopkins ("Polly") Cabell, daughter of Joseph Cabell, a member of the Cabell political family. Polly's dowry

A dowry is a payment, such as property or money, paid by the bride's family to the groom or his family at the time of marriage. Dowry contrasts with the related concepts of bride price and dower. While bride price or bride service is a payment ...

included a 400-acre (1.6-km2) plantation in Albemarle County

Albemarle County is a county located in the Piedmont region of the Commonwealth of Virginia. Its county seat is Charlottesville, which is an independent city and enclave entirely surrounded by the county. Albemarle County is part of the Char ...

dubbed "The Glebe". Nine children were born to the John and Polly Breckinridge – Letitia Preston (b. 1786), Joseph "Cabell" (b. 1787), Mary Hopkins (b. 1790), Robert (b. 1793), Mary Ann (b. 1795), John (b. 1797), Robert Jefferson

Robert Jefferson (11 July 1881 – 1 January 1968) was a Canadian Anglican bishop in the mid-20th century.

Jefferson was educated at St John's College, Manitoba and ordained in 1908. Crockford's Clerical Directory1951–52 p970: Oxford, OUP,1951 ...

(b. 1800), William Lewis (b. 1803), and James Monroe (b. 1806).

Polly, Cabell, and Letitia all fell ill but survived a smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by variola virus (often called smallpox virus) which belongs to the genus Orthopoxvirus. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization (WHO) c ...

epidemic in 1793; however, Mary Hopkins and their first son named Robert died.Klotter in ''The Breckinridges of Kentucky'', p. 32. Cabell Breckinridge

Joseph Cabell Breckinridge (July 14, 1788 – September 1, 1823) was a lawyer, soldier, slaveholder and politician in the U.S. state of Kentucky. From 1816 to 1819, he represented Fayette County in the Kentucky House of Representatives, and fel ...

would later follow a similar career as a planter, lawyer and politician, and become Speaker of the Kentucky House of Representatives

The Kentucky House of Representatives is the lower house of the Kentucky General Assembly. It is composed of 100 Representatives elected from single-member districts throughout the Commonwealth. Not more than two counties can be joined to form a ...

and later Kentucky's Secretary of State.Klotter in ''The Breckinridges of Kentucky'', p. 40. Other sons became ministers and planters; the family's loyalties would be split during the American Civil War long after this man's death. Cabell Beckinridge's son John C. Breckinridge continued the family legal, planter and political traditions and become U.S. Vice President

The vice president of the United States (VPOTUS) is the second-highest officer in the executive branch of the U.S. federal government, after the president of the United States, and ranks first in the presidential line of succession. The vice pr ...

John C. Breckinridge, and a presidential candidate, only to side with the Confederacy during the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and t ...

.Klotter in ''The Kentucky Encyclopedia'', p. 116. Meanwhile his brother John Breckinridge also attended the same university, receiving a degree from Princeton Theological Seminary

Princeton Theological Seminary (PTSem), officially The Theological Seminary of the Presbyterian Church, is a private school of theology in Princeton, New Jersey. Founded in 1812 under the auspices of Archibald Alexander, the General Assembly of t ...

, before serving as chaplain of the U.S. House of Representatives, and president of Oglethorpe College (now Oglethorpe University

Oglethorpe University is a private college in Brookhaven, Georgia. It was chartered in 1835 and named in honor of General James Edward Oglethorpe, founder of the Colony of Georgia.

History

Oglethorpe University was chartered in 1834 in Mid ...

) in Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to the ...

. Robert Jefferson Breckinridge became superintendent of public instruction under Governor William Owsley

William Owsley (March 24, 1782 – December 9, 1862) was an associate justice of the Kentucky Court of Appeals and the 16th Governor of Kentucky. He also served in both houses of the Kentucky General Assembly and was Kentucky Secretary of Sta ...

and became known as the father of Kentucky's public education system. William Lewis Breckinridge became a prominent Presbyterian

Presbyterianism is a part of the Reformed tradition within Protestantism that broke from the Roman Catholic Church in Scotland by John Knox, who was a priest at St. Giles Cathedral (Church of Scotland). Presbyterian churches derive their n ...

minister, serving as moderator of the Presbyterian General Assembly in 1859 and later as president of Centre College

Centre College is a private liberal arts college in Danville, Kentucky. It is an undergraduate college with an enrollment of approximately 1,400 students. Centre was officially chartered by the Kentucky General Assembly in 1819. The college is a ...

in Danville, Kentucky

Danville is a home rule-class city in Boyle County, Kentucky, United States. It is the seat of its county. The population was 17,236 at the 2020 Census. Danville is the principal city of the Danville Micropolitan Statistical Area, which include ...

, and Oakland College in Yale, Mississippi. In 1804, this Breckinridge's daughter Letitia married Alfred W. Grayson, son of Virginia Senator William Grayson

William Grayson (1742 – March 12, 1790) was a planter, lawyer and statesman from Virginia. After leading a Virginia regiment in the Continental Army, Grayson served in the Virginia House of Delegates before becoming one of the first two U ...

.Klotter in ''The Breckinridges of Kentucky'', p. 33. Alfred Grayson died in 1808, and in 1816, the widowed Letitia married Peter Buell Porter

Peter Buell Porter (August 14, 1773 – March 20, 1844) was an American lawyer, soldier and politician who served as United States Secretary of War from 1828 to 1829.

Early life

Porter was born on August 14, 1773, one of six children born to Dr. ...

, who would later serve as Secretary of War

The secretary of war was a member of the U.S. president's Cabinet, beginning with George Washington's administration. A similar position, called either "Secretary at War" or "Secretary of War", had been appointed to serve the Congress of the ...

under President John Quincy Adams

John Quincy Adams (; July 11, 1767 – February 23, 1848) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, and diarist who served as the sixth president of the United States, from 1825 to 1829. He previously served as the eighth United States ...

.

Meanwhile, farming at the Glebe proved barely enough for Breckinridge's growing family.Harrison in "A Young Virginian", p. 28. Breckinridge's legal career provided enough money for some comforts but required long hours and difficult work.Harrison in "A Young Virginian", p. 30. Patrick Henry regularly represented clients opposite Breckinridge, and John Marshall both referred clients to him and asked him to represent his own clients in his absence. Though still interested in politics, Breckinridge refused to campaign for the people's support.Harrison in "A Young Virginian", p. 31. He believed changes were needed to the Articles of Confederation and agreed with much of the proposed U.S. constitution, but he did not support equal representation of the states in the Senate nor the federal judiciary.Harrison in ''John Breckinridge: Jeffersonian Republican'', p. 38. Heeding the advice of his brother James and his friend, Archibald Stuart

Archibald Stuart (December 2, 1795 – September 20, 1855) was a nineteenth-century politician and lawyer from Virginia. He was the first cousin of Alexander Hugh Holmes Stuart and the father of Confederate General James Ewell Brown "Je ...

, he did not seek election as a delegate to Virginia's ratification convention.

Relocation to Kentucky

Breckinridge's half-brothers, Andrew and Robert, moved toKentucky

Kentucky ( , ), officially the Commonwealth of Kentucky, is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States and one of the states of the Upper South. It borders Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio to the north; West Virginia and Virginia ...

in 1781, and his brother William followed in 1783. By 1785, Andrew and Robert were trustees of Louisville

Louisville ( , , ) is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Kentucky and the 28th most-populous city in the United States. Louisville is the historical seat and, since 2003, the nominal seat of Jefferson County, on the Indiana border.

...

.Klotter in ''The Breckinridges of Kentucky'', p. 12. Their letters described Kentucky's abundant land and plentiful legal business, in contrast to the crowded bar

Bar or BAR may refer to:

Food and drink

* Bar (establishment), selling alcoholic beverages

* Candy bar

* Chocolate bar

Science and technology

* Bar (river morphology), a deposit of sediment

* Bar (tropical cyclone), a layer of cloud

* Bar ( ...

and scarce unclaimed land in Virginia. By 1788, Breckinridge was convinced that Kentucky offered him more opportunity, and the next year, he traveled west to seek land on which to construct an estate.Harrison in "John Breckinridge of Kentucky", p. 205.Harrison in "A Virginian Moves to Kentucky", p. 203. Although inaccurate reports of his death reached Virginia, he arrived safely in Kentucky on April 15, 1789, and returned to Virginia in June.Harrison in "A Virginian Moves to Kentucky", p. 205. The following year, he paid 360 pounds sterling

Sterling (abbreviation: stg; Other spelling styles, such as STG and Stg, are also seen. ISO code: GBP) is the currency of the United Kingdom and nine of its associated territories. The pound ( sign: £) is the main unit of sterling, and ...

for along the North Elkhorn Creek about from present-day Lexington, Kentucky

Lexington is a city in Kentucky, United States that is the county seat of Fayette County. By population, it is the second-largest city in Kentucky and 57th-largest city in the United States. By land area, it is the country's 28th-largest ...

. The land, purchased from his only sister Betsy's father-in-law, lay adjacent to land owned by his sister, and in 1792, he purchased an adjacent , bringing his total holdings in Kentucky to .Harrison in "John Breckinridge of Kentucky", p. 206. After the purchase, he instructed William Russell, a friend already living in Kentucky, to find tenants to lease and improve the land.Harrison in "A Virginian Moves to Kentucky", p. 206.

In February 1792, Breckinridge, a Democratic-Republican

The Democratic-Republican Party, known at the time as the Republican Party and also referred to as the Jeffersonian Republican Party among other names, was an American political party founded by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison in the early ...

, was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives over token opposition.Harrison in "A Young Virginian", p. 32. On the date of the election, he wrote to Archibald Stuart, "The People appearing willing to elect, I could have no objection to serve them one Winter in Congress."Harrison in "A Virginian Moves to Kentucky", p. 209. Despite this, he left for Kentucky in March 1793 and resigned without serving a day in Congress

A congress is a formal meeting of the representatives of different countries, constituent states, organizations, trade unions, political parties, or other groups. The term originated in Late Middle English to denote an encounter (meeting of ...

, which convened on March 4.Harrison in "A Young Virginian", p. 34. He chose the longer but safer route to Kentucky, joining a group of flatboats at Brownsville, Pennsylvania

Brownsville is a borough in Fayette County, Pennsylvania, United States, first settled in 1785 as the site of a trading post a few years after the defeat of the Iroquois enabled a post-Revolutionary war resumption of westward migration. The Tradin ...

, for the trip down the Monongahela and Ohio

Ohio () is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. Of the List of states and territories of the United States, fifty U.S. states, it is the List of U.S. states and territories by area, 34th-l ...

rivers to Limestone (now Maysville, Kentucky

Maysville is a home rule-class city in Mason County, Kentucky, United States and is the seat of Mason County. The population was 8,782 as of 2019, making it the 51st-largest city in Kentucky by population. Maysville is on the Ohio River, north ...

). His family, along with 25 slaves, arrived in April and established their plantation, Cabell's Dale.Harrison in "John Breckinridge of Kentucky", p. 210. By the time of Breckinridge's move, he owned in Kentucky.

Domestic life in Kentucky

When he arrived in Kentucky, much of Breckinridge's land was occupied bytenant farmer

A tenant farmer is a person (farmer or farmworker) who resides on land owned by a landlord. Tenant farming is an agricultural production system in which landowners contribute their land and often a measure of operating capital and management, ...

s whose leases had not yet expired. He planted rye and wheat on of unleased land and sent 11 slaves and an overseer to clear land for the fall planting. Eventually, his crops at Cabell's Dale included corn, wheat, rye, barley, hay, grass seed, and hemp, but he refused to grow tobacco, a major cash crop, which he found too vulnerable to over-cultivation. He also bred thoroughbred

The Thoroughbred is a horse breed best known for its use in horse racing. Although the word ''thoroughbred'' is sometimes used to refer to any breed of purebred horse, it technically refers only to the Thoroughbred breed. Thoroughbreds are ...

horses, planted an orchard, and practiced law. He engaged in land speculation, particularly in the Northwest Territory

The Northwest Territory, also known as the Old Northwest and formally known as the Territory Northwest of the River Ohio, was formed from unorganized western territory of the United States after the American Revolutionary War. Established in 1 ...

, and at various times owned interests in iron and salt works, but these ventures were never very successful.Harrison in "John Breckinridge: Western Statesman", p. 142.

As his plantation became more productive, Breckinridge became interested in ways to sell his excess goods.Harrison in "John Breckinridge of Kentucky", p. 208. On August 26, 1793, he became a charter member of the Democratic Society of Kentucky, which lobbied the federal government to secure unrestricted use of the Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the List of longest rivers of the United States (by main stem), second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest Drainage system (geomorphology), drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson B ...

from Spain.Harrison and Klotter, p. 73. Breckinridge was elected chairman, Robert Todd and John Bradford

John Bradford (1510–1555) was an English Reformer, prebendary of St. Paul's, and martyr. He was imprisoned in the Tower of London for alleged crimes against Queen Mary I. He was burned at the stake on 1 July 1555.

Life

Bradford was born ...

were chosen as vice-chairmen, and Thomas Todd and Thomas Bodley were elected as clerks.Harrison in ''John Breckinridge: Jeffersonian Republican'', p. 54. Breckinridge authored a tract entitled ''Remonstrance of the Citizens West of the Mountains to the President and Congress of the United States'' and may have also written ''To the Inhabitants of the United States West of the Allegany (sic) and Apalachian (sic) Mountains''. He pledged funding to French minister Edmond-Charles Genêt

Edmond-Charles Genêt (January 8, 1763July 14, 1834), also known as Citizen Genêt, was the French envoy to the United States appointed by the Girondins during the French Revolution. His actions on arriving in the United States led to a major po ...

's proposed military operation against Spain, but Genêt was recalled before it could be executed.Klotter in ''The Breckinridges of Kentucky'', p. 18. Although alarmed that frontier settlers might initiate war with Spain, President George Washington

George Washington (February 22, 1732, 1799) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first president of the United States from 1789 to 1797. Appointed by the Continental Congress as commander of ...

made no immediate attempt to obtain use of the Mississippi, which the society maintained was "the natural right of the citizens of this Commonwealth". The resistance of the eastern states, particularly Federalist

The term ''federalist'' describes several political beliefs around the world. It may also refer to the concept of parties, whose members or supporters called themselves ''Federalists''.

History Europe federation

In Europe, proponents of de ...

politicians, caused Breckinridge to reconsider his support of a strong central government.Klotter in ''The Breckinridges of Kentucky'', p. 19.

Breckinridge was also concerned with easing overland transport of goods to Virginia. In mid-1795, he, Robert Barr, Elijah Craig, and Harry Toulmin formed a committee to raise funds for a road connecting the Cumberland Gap

The Cumberland Gap is a pass through the long ridge of the Cumberland Mountains, within the Appalachian Mountains, near the junction of the U.S. states of Kentucky, Virginia, and Tennessee. It is famous in American colonial history for its r ...

to central Kentucky. Breckinridge was disappointed with the quality of the route, which was finished in late 1796, concluding that the individual maintaining it was keeping most of the tolls instead of using them for the road's upkeep.

Breckinridge was also interested in education. Before moving to Kentucky, he accumulated a substantial library of histories, biographies, law and government texts, and classical literature. Frequently, he allowed aspiring lawyers and students access to the library, which was one of the most extensive in the west.Klotter in ''The Breckinridges of Kentucky'', p. 15. He also provided funding for a municipal library in Lexington. His lobbying for a college to be established in Lexington bore fruit with the opening of Transylvania Seminary (now Transylvania University

Transylvania University is a private university in Lexington, Kentucky. It was founded in 1780 and was the first university in Kentucky. It offers 46 major programs, as well as dual-degree engineering programs, and is accredited by the Southern ...

) in 1788. He was elected to the seminary's board of trustees on October 9, 1793, and supported hiring Harry Toulmin as president in February 1794 and consolidating the seminary with Kentucky Academy in 1796.Harrison in ''John Breckinridge: Jeffersonian Republican'', pp. 64–65. Conservatives on the board and in the Kentucky General Assembly

The Kentucky General Assembly, also called the Kentucky Legislature, is the state legislature of the U.S. state of Kentucky. It comprises the Kentucky Senate and the Kentucky House of Representatives.

The General Assembly meets annually in ...

forced Toulmin – a liberal Unitarian – to resign in 1796, and Breckinridge's enthusiasm for his trusteeship waned. He attended board meetings less frequently and resigned in late 1797.Harrison in ''John Breckinridge: Jeffersonian Republican'', p. 65.

Kentucky Attorney General

Kentucky needed qualified governmental leaders, and on December 19, 1793,Kentucky Governor

The governor of the Commonwealth of Kentucky is the head of government of Kentucky. Sixty-two men and one woman have served as governor of Kentucky. The governor's term is four years in length; since 1992, incumbents have been able to seek re- ...

Isaac Shelby

Isaac Shelby (December 11, 1750 – July 18, 1826) was the first and fifth Governor of Kentucky and served in the state legislatures of Virginia and North Carolina. He was also a soldier in Lord Dunmore's War, the American Revolutionary Wa ...

appointed Breckinridge attorney general

In most common law jurisdictions, the attorney general or attorney-general (sometimes abbreviated AG or Atty.-Gen) is the main legal advisor to the government. The plural is attorneys general.

In some jurisdictions, attorneys general also have exec ...

. Three weeks after accepting, he was offered the post of District Attorney for the Federal District of Kentucky, but he declined.Harrison in ''John Breckinridge: Jeffersonian Republican'', p. 62. Secretary of State Edmund Randolph

Edmund Jennings Randolph (August 10, 1753 September 12, 1813) was a Founding Father of the United States, attorney, and the 7th Governor of Virginia. As a delegate from Virginia, he attended the Constitutional Convention and helped to create ...

directed Shelby to prevent French agents in Kentucky from organizing an expedition against Spanish Louisiana.Harrison in ''John Breckinridge: Jeffersonian Republican'', p. 59. On Breckinridge's advice, Shelby responded that he lacked the authority to interfere. Lack of funding prevented the expedition, but Shelby's noncommittal response helped prompt passage of the Neutrality Act of 1794

The Neutrality Act of 1794 was a United States law which made it illegal for a United States citizen to wage war against any country at peace with the United States.

The Act declares in part:

If any person shall within the territory or jurisdic ...

which outlawed participation by U.S. citizens in such expeditions.Harrison in ''John Breckinridge: Jeffersonian Republican'', p. 60.

In November 1794, the Democratic-Republicans nominated Breckinridge to succeed

In November 1794, the Democratic-Republicans nominated Breckinridge to succeed John Edwards

Johnny Reid Edwards (born June 10, 1953) is an American lawyer and former politician who served as a U.S. senator from North Carolina. He was the Democratic nominee for vice president in 2004 alongside John Kerry, losing to incumbents George ...

in the U.S. Senate.Harrison and Klotter, p. 75. Federalist

The term ''federalist'' describes several political beliefs around the world. It may also refer to the concept of parties, whose members or supporters called themselves ''Federalists''.

History Europe federation

In Europe, proponents of de ...

s were generally unpopular in Kentucky, but the signing of Pinckney's Treaty

Pinckney's Treaty, also known as the Treaty of San Lorenzo or the Treaty of Madrid, was signed on October 27, 1795 by the United States and Spain.

It defined the border between the United States and Spanish Florida, and guaranteed the United S ...

– which temporarily secured Kentucky's use of the Mississippi River – and Anthony Wayne

Anthony Wayne (January 1, 1745 – December 15, 1796) was an American soldier, officer, statesman, and one of the Founding Fathers of the United States. He adopted a military career at the outset of the American Revolutionary War, where his mil ...

's expedition against the Indians in the Northwest Territory prompted a surge of support for the federal government in Kentucky.Harrison in ''John Breckinridge: Jeffersonian Republican'', p. 63. The election's first ballot reflected this, as Federalist candidate Humphrey Marshall received 18 votes to Breckinridge's 16, John Fowler's 8, and 7 votes for the incumbent Edwards. On the runoff ballot, Marshall was elected over Breckinridge by a vote of 28–22. Harrison posits that Marshall's incumbency in the General Assembly may have aided his election but notes that Marshall downplayed its significance.

In May 1796, Kentucky's gubernatorial electors convened to choose Shelby's successor. Their votes were split among four candidates; frontiersman Benjamin Logan received 21 votes, Baptist

Baptists form a major branch of Protestantism distinguished by baptizing professing Christian believers only ( believer's baptism), and doing so by complete immersion. Baptist churches also generally subscribe to the doctrines of soul c ...

minister James Garrard

James Garrard (January 14, 1749 – January 19, 1822) was an American farmer, Baptist minister and politician who served as the second governor of Kentucky from 1796 to 1804. Because of term limits imposed by the state constitution adopted in ...

received 17, Thomas Todd received 14, and Breckinridge's cousin, Senator John Brown, received 1. The Kentucky Constitution The Constitution of the Commonwealth of Kentucky is the document that governs the Kentucky, Commonwealth of Kentucky. It was first adopted in 1792 and has since been rewritten three times and amended many more. The later versions were adopted in 179 ...

did not specify whether a plurality or a majority

A majority, also called a simple majority or absolute majority to distinguish it from related terms, is more than half of the total.Dictionary definitions of ''majority'' aMerriam-Websterstate senate

A state legislature in the United States is the legislative body of any of the 50 U.S. states. The formal name varies from state to state. In 27 states, the legislature is simply called the ''Legislature'' or the ''State Legislature'', whil ...

was authorized to settle disputed elections, but they, too, refused to intervene. Breckinridge resigned as attorney general on November 30, 1797; the extension of the attorney general's duties to include representing the state in federal district court as well as the Kentucky Court of Appeals

The Kentucky Court of Appeals is the lower of Kentucky's two appellate courts, under the Kentucky Supreme Court. Prior to a 1975 amendment to the Kentucky Constitution the Kentucky Court of Appeals was the only appellate court in Kentucky.

Th ...

, and reluctance to serve under Garrard after publicly declaring he had no right to his office may have contributed to the decision. A month later, he declared his candidacy to fill a vacancy in the Fayette County delegation to the Kentucky House of Representatives.Harrison in ''John Breckinridge: Jeffersonian Republican'', p. 72. Of the 1,323 votes cast, he garnered 594 (45%), the most of any of the six candidates in the race.

Kentucky House of Representatives

Breckinridge pressed to reform the state's criminal code, which was based on the English system and imposed the death penalty for over 200 different crimes.Harrison and Klotter, p. 83. Inspired by Thomas Jefferson's failed attempt to reform Virginia's code, he first asked the Lexington Democratic Society to study ways to make punishments more proportional to crimes in November 1793. By 1796, he was drafting a new code based on the principles that criminals should be rehabilitated, victims should be compensated for their injury, the public should be reimbursed for the cost of prosecuting the criminal, and the punishment's severity should serve as a deterrent for would-be offenders. In January 1798, he introduced his proposed code in the General Assembly. A month later, the Assembly reformed the code, abolishing the death penalty for every crime exceptfirst-degree murder

Murder is the unlawful killing of another human without justification or valid excuse, especially the unlawful killing of another human with malice aforethought. ("The killing of another person without justification or excuse, especially t ...

.

Kentucky Resolutions

In August, Breckinridge traveled to Virginia's Sweet Springs to improve his health.Harrison in ''John Breckinridge: Jeffersonian Republican'', p. 74. He visited family and friends while there, but the exact dates and locations he visited are not known.Harrison in ''John Breckinridge: Jeffersonian Republican''. At some point, he obtained a draft of resolutions written by Vice President Thomas Jefferson denouncing the recently-enactedAlien and Sedition Acts

The Alien and Sedition Acts were a set of four laws enacted in 1798 that applied restrictions to immigration and speech in the United States. The Naturalization Act increased the requirements to seek citizenship, the Alien Friends Act allowed th ...

. Jefferson wished to keep his authorship secret, and Breckinridge accepted credit for them during his life. In 1814, John Taylor revealed Jefferson's authorship; Breckinridge's grandson, John C. Breckinridge, wrote Jefferson for confirmation of Taylor's claims. Cautioning that the passage of time and his failing memory might cause him to inaccurately recount the details, Jefferson responded that he, Breckinridge, Wilson Nicholas, and possibly James Madison met at Monticello

Monticello ( ) was the primary plantation of Founding Father Thomas Jefferson, the third president of the United States, who began designing Monticello after inheriting land from his father at age 26. Located just outside Charlottesville, V ...

, at a date Jefferson could not recall, to discuss the need for resolutions denouncing the Alien and Sedition Acts. They decided that Jefferson would pen the resolutions and that Breckinridge would introduce them in the Kentucky legislature upon his return to that state.

Letters between Nicholas and Jefferson indicate a different series of events.Harrison in ''John Breckinridge: Jeffersonian Republican'', p. 76. In a letter dated October 4, 1798, Nicholas informed Jefferson that he had given "a copy of the resolutions you sent me" to Breckinridge, who would introduce them in Kentucky. The letter also indicated that this was a deviation from the original plan to deliver the draft to a legislator in

Letters between Nicholas and Jefferson indicate a different series of events.Harrison in ''John Breckinridge: Jeffersonian Republican'', p. 76. In a letter dated October 4, 1798, Nicholas informed Jefferson that he had given "a copy of the resolutions you sent me" to Breckinridge, who would introduce them in Kentucky. The letter also indicated that this was a deviation from the original plan to deliver the draft to a legislator in North Carolina

North Carolina () is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. The state is the List of U.S. states and territories by area, 28th largest and List of states and territories of the United ...

for introduction in the legislature there.Schachner, p. 613. Nicholas felt that recipient was too closely associated with Jefferson, risking his being discovered as the resolutions' author. According to Nicholas, Breckinridge wanted to discuss the draft with Jefferson, but Nicholas advised against the meeting, fearing it could implicate Jefferson. A subsequent letter from Jefferson expressed his approval of Nicholas' actions. Lowell Harrison notes that after Breckinridge left Virginia, his contacts with Jefferson were few until his election to the Senate in 1801. Harrison considered it unlikely that Jefferson was mistaken about a meeting between the two to discuss a matter as important as the resolutions, positing that Jefferson may have met separately with Breckinridge and Nicholas to discuss the resolutions, and that the meeting with Breckinridge was kept secret from Nicholas.Harrison in ''John Breckinridge: Jeffersonian Republican'', p. 77. Because of the uncertainty surrounding Breckinridge's activities in Virginia in 1798, the extent of his influence on Jefferson's original draft of the resolutions is unknown.

In Garrard's November 5, 1798, State of the Commonwealth address, he encouraged the General Assembly to declare its views on the Alien and Sedition Acts.Harrison in ''John Breckinridge: Jeffersonian Republican'', p. 78. Breckinridge was chosen as chairman of a three-person committee to carry out the governor's charge. The resolutions that the committee brought to the floor on November 10 became known as the Kentucky Resolutions

The Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions were political statements drafted in 1798 and 1799 in which the Kentucky and Virginia legislatures took the position that the federal Alien and Sedition Acts were unconstitutional. The resolutions argued t ...

.Klotter in ''The Breckinridges of Kentucky'', p. 20. The first seven were exactly as Jefferson had written them, but Breckinridge modified the last two, eliminating Jefferson's suggestion of nullifying the unpopular acts.Harrison and Klotter, p. 82. During the debate on the House floor, Breckinridge endorsed nullification if Congress would not repeal the acts after a majority of states declared their opposition to them. Federalist William Murray led opposition to the resolutions in the House but was the only dissenting vote on five of the nine; John Pope led similarly unsuccessful Federalist opposition in the Senate. Upon concurrence of both houses, Garrard signed the resolutions.

Federalist state legislatures, primarily those north of the Potomac River

The Potomac River () drains the Mid-Atlantic United States, flowing from the Potomac Highlands into Chesapeake Bay. It is long,U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map. Retrieved Augu ...

, sent the Kentucky General Assembly negative responses to the resolutions. Nicholas convinced Jefferson that Kentucky should adopt a second set of resolutions affirming the first, lest the lack of a reply be seen acquiescence.Schachner, p. 627. Jefferson refused to compose these resolutions, maintaining that there were sufficiently talented individuals in Kentucky to compose them and fearing still that he would be discovered as the author of the first set. Breckinridge, chosen Speaker of the Kentucky House of Representatives at the outset of the 1799 session, took on the task, drafting resolutions reasserting the original principles and endorsing nullification.Although some historians have questioned Breckinridge's authorship of the second set of resolutions, Jefferson biographer Nathan Schachner noted that original drafts of those resolutions, in Breckinridge's handwriting, are among his papers housed at the Library of Congress. See Schachner, p. 628. The resolutions unanimously passed the House. The Federalist minority in the Senate opposed them, especially the endorsement of nullification, but that chamber also adopted the resolutions as written. Breckinridge's presumed authorship of the original resolutions and his subsequent defense of them caused his popularity to soar in Kentucky.

Kentucky Constitution of 1799

Some Kentucky citizens were already displeased with parts of the state's constitution, and the disputed gubernatorial election of 1796 had added to the enthusiasm of those calling for a constitutional convention to revise it. Breckinridge opposed such a call, fearing changes would imperil his wealth and power.Harrison and Klotter, p. 76. John Breckinridge asked, "Where is the difference whether I am robbed of my horse by a highway-man, or of my slave by a set of people called a Convention? ... If they can by one experiment emancipate our slaves; the same principle pursued, will enable them at a second experiment to extinguish our land titles; both are held by rights equally sound."Friend, Craig Thompson. 2010. Kentucke's Frontiers. Indiana University Press, p. 208. The desire for a convention was so strong, even in aristocratic Fayette County, that Breckinridge's position nearly cost him his seat in the legislature.Harrison in ''John Breckinridge: Jeffersonian Republican'', p. 100. Seeking election to a full term in May 1798, he was the seventh-highest vote-getter, securing the last of Fayette County's seats in the legislature by only eight votes. Despite the efforts of conservatives like Breckinridge and George Nicholas, in late 1798, the General Assembly called a convention for July 22, 1799. Delegates to the convention were to be elected in May 1799, and the conservatives immediately began organizing slates of candidates that would represent their interests. Popular because of his role in securing adoption of the Kentucky Resolutions, Breckinridge was among the six conservative candidates promoted in Fayette County, all of whom were elected.Harrison in ''John Breckinridge: Jeffersonian Republican'', p. 101. Out of the fifty-eight men who arrived in Frankfort in late July as convention delegates, fifty-seven owned slaves and fifty held substantial property. Between the election and the convention, Breckinridge and Judge Caleb Wallace worked with Nicholas (who did not seek election as a delegate) to draft resolutions that Breckinridge would introduce at the convention in an attempt to steer the proceedings toward conservative positions.Harrison and Klotter, p. 77. The largest group of delegates at the convention – about 18 in number – were aristocrats who advocated protection of their wealth and status, including institutingvoice voting

In parliamentary procedure, a voice vote (from the Latin ''viva voce'', meaning "live voice") or acclamation is a voting method in deliberative assemblies (such as legislatures) in which a group vote is taken on a topic or motion by responding vo ...

in the legislature (which left legislators vulnerable to intimidation), safeguarding legal slavery, and limiting the power of the electorate. A smaller group led by Green Clay and Robert Johnson consisted mostly of planters who opposed most limits on the power of the legislature, which they believed was superior to the executive and judicial branches. A third group, led by future governor John Adair

John Adair (January 9, 1757 – May 19, 1840) was an American pioneer, slave trader, soldier, and politician. He was the eighth Governor of Kentucky and represented the state in both the U.S. House and Senate. A native of South Carolina, Ada ...

, agreed with the notion of legislative supremacy, but opposed limits on other branches of the government. The smallest group was the most populist and was led by John Bailey. The conservative faction strengthened the previous constitution's slavery protections by denying suffrage to free blacks and mulattoes. Legislative apportionment based on population, the addition of a lieutenant governor, and voice voting of the legislature – all issues advocated by Breckinridge – were also adopted.Harrison and Klotter, p. 78. He was unable to preserve the electoral college that elected the governor and state senators, but the direct election of these officers was balanced by a provision that county sheriffs and judges be appointed by the governor and confirmed by the Senate.Klotter in ''The Breckinridges of Kentucky'', p. 27.Harrison in "John Breckinridge: Western Statesman", p. 141. Attempts to make judicial decisions subject to legislative approval were defeated after Breckinridge defended the extant judicial system. He was also the architect of the constitution's provisions for amendment, which made changing the document difficult, but not entirely impossible. Because of his leading role in the convention, Breckinridge was regarded as the father of the resultant constitution, which was ratified in 1799, and emerged from the convention as the leader of his party. He was reelected as Speaker of the House in 1800.

U.S. Senator

On November 20, 1800, theKentucky General Assembly

The Kentucky General Assembly, also called the Kentucky Legislature, is the state legislature of the U.S. state of Kentucky. It comprises the Kentucky Senate and the Kentucky House of Representatives.

The General Assembly meets annually in ...

elected Breckinridge to the U.S. Senate by a vote of 68–13 over John Adair.Harrison in ''John Breckinridge: Jeffersonian Republican'', p. 110. He was eligible for the special congressional session called for March 4, 1801, but his summons to the session remained undelivered at the Lexington post office until March 5, and he consequently missed the entire session. When he left for Washington, D.C., late in the year, he left several of his pending legal cases in the hands of rising attorney Henry Clay

Henry Clay Sr. (April 12, 1777June 29, 1852) was an American attorney and statesman who represented Kentucky in both the United States Senate, U.S. Senate and United States House of Representatives, House of Representatives. He was the seven ...

, who would later become U.S. Secretary of State.Klotter in ''The Breckinridges of Kentucky'', p. 28.

Although Democratic-Republicans held a narrow majority in the Senate, the Federalist senators were both experienced and devoted their cause. Breckinridge acted as floor leader for the Democratic-Republicans and newly elected president, Thomas Jefferson. His proposed repeal of the Federalist-supported Judicial Act of 1801, which had increased the number of federal courts and judges, was particularly controversial.Klotter in ''The Kentucky Encyclopedia'', p. 117. On January 4, 1802, he presented caseload data to argue that the new courts and judges were unnecessary. Federalist leader Gouverneur Morris

Gouverneur Morris ( ; January 31, 1752 – November 6, 1816) was an American statesman, a Founding Father of the United States, and a signatory to the Articles of Confederation and the United States Constitution. He wrote the Preamble to th ...

countered that the proposal was unconstitutional; once established, courts were inviolate, he maintained.Harrison in ''John Breckinridge: Jeffersonian Republican'', p. 142. On January 20, Federalist Jonathan Dayton

Jonathan Dayton (October 16, 1760October 9, 1824) was an American Founding Father and politician from the U.S. state of New Jersey. He was the youngest person to sign the Constitution of the United States and a member of the United States Hou ...

moved to return the bill to a committee to consider amendments.Harrison in "John Breckinridge: Western Statesman", p. 143.Harrison in ''John Breckinridge: Jeffersonian Republican'', p. 144. South Carolina

)''Animis opibusque parati'' ( for, , Latin, Prepared in mind and resources, links=no)

, anthem = " Carolina";" South Carolina On My Mind"

, Former = Province of South Carolina

, seat = Columbia

, LargestCity = Charleston

, LargestMetro = ...

's John E. Colhoun, a Democratic-Republican, voted with the Federalists, and the result was a 15–15 tie. Empowered to break the tie, Jefferson's vice president, Aaron Burr

Aaron Burr Jr. (February 6, 1756 – September 14, 1836) was an American politician and lawyer who served as the third vice president of the United States from 1801 to 1805. Burr's legacy is defined by his famous personal conflict with Alexand ...

, voted with the Federalists. The five-man committee consisted of three Federalists, enough to prevent the bill's return to the floor, but when Vermont

Vermont () is a U.S. state, state in the northeast New England region of the United States. Vermont is bordered by the states of Massachusetts to the south, New Hampshire to the east, and New York (state), New York to the west, and the Provin ...

Senator Stephen R. Bradley

Stephen Row Bradley (February 20, 1754 – December 9, 1830) was an American lawyer, judge and politician. He served as a United States Senator from the state of Vermont and as the President pro tempore of the United States Senate during the ...

, who had traveled home because of a family illness, returned to the chamber, the Democratic-Republicans regained a majority and introduced a successful discharge petition

In United States parliamentary procedure, a discharge petition is a means of bringing a bill out of committee and to the floor for consideration without a report from the committee by "discharging" the committee from further consideration of a bil ...

.Schachner, p. 703. In one last attempt to derail the legislation in debate, Federalists argued that the judiciary would strike down the repeal as unconstitutional; Breckinridge denied the notion that the courts had the power to invalidate an act of Congress. On February 3, the Senate repealed the act by a vote of 16–15, with the House concurring a month later.

Louisiana Purchase

Breckinridge advocated internal improvements and formed a coalition of legislators from South Carolina, Georgia,Tennessee

Tennessee ( , ), officially the State of Tennessee, is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. Tennessee is the List of U.S. states and territories by area, 36th-largest by ...

and Kentucky to support a system of roads connecting the Southern coastal states with the western frontier, but the routes they proposed proved impossible to construct with the technology available at the time.Harrison in "John Breckinridge of Kentucky", p. 209. Spanish revocation of Kentucky's right of deposit at – in violation of Pinckney's Treaty – further frustrated and angered frontier residents.Harrison and Klotter, p. 84. Although many desired war with Spain, Jefferson believed a diplomatic resolution was possible and urged restraint.Harrison in "John Breckinridge: Western Statesman", p. 144. Federalists, seeking to divide the Democratic-Republicans and curry favor with the West, abandoned their usual advocacy of peace. Pennsylvania Federalist James Ross introduced a measure allocating $5 million and raising 50,000 militiamen to seize the Louisiana Territory

The Territory of Louisiana or Louisiana Territory was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from July 4, 1805, until June 4, 1812, when it was renamed the Missouri Territory. The territory was formed out of the ...

from Spain. Cognizant of Jefferson's desire for more time, Breckinridge offered a substitute resolution on February 23, 1803, allocating 80,000 troops and unlimited funds for the potential invasion of New Orleans, but he left their use at the discretion of the president. Breckinridge's resolution was adopted after a heated debate.

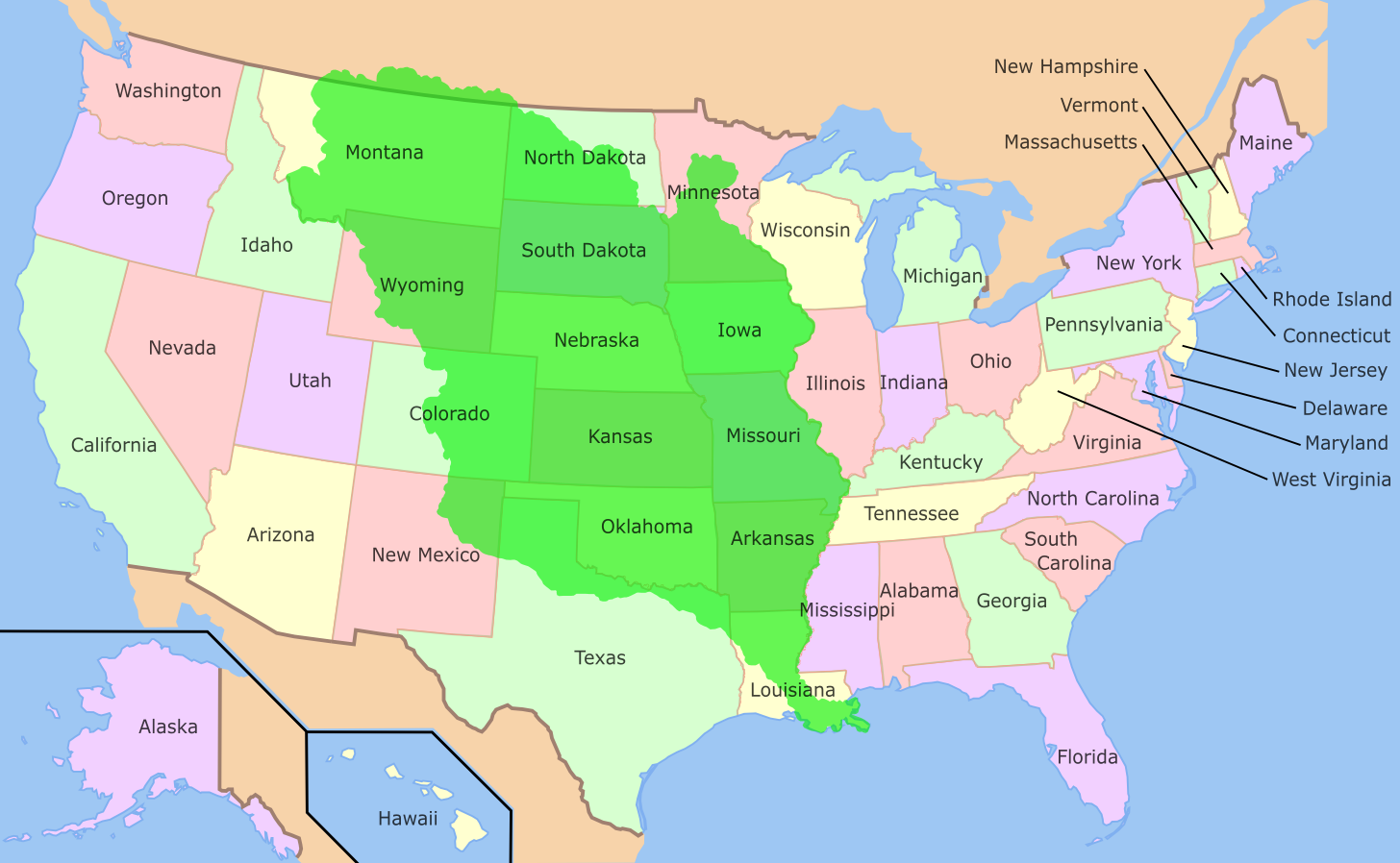

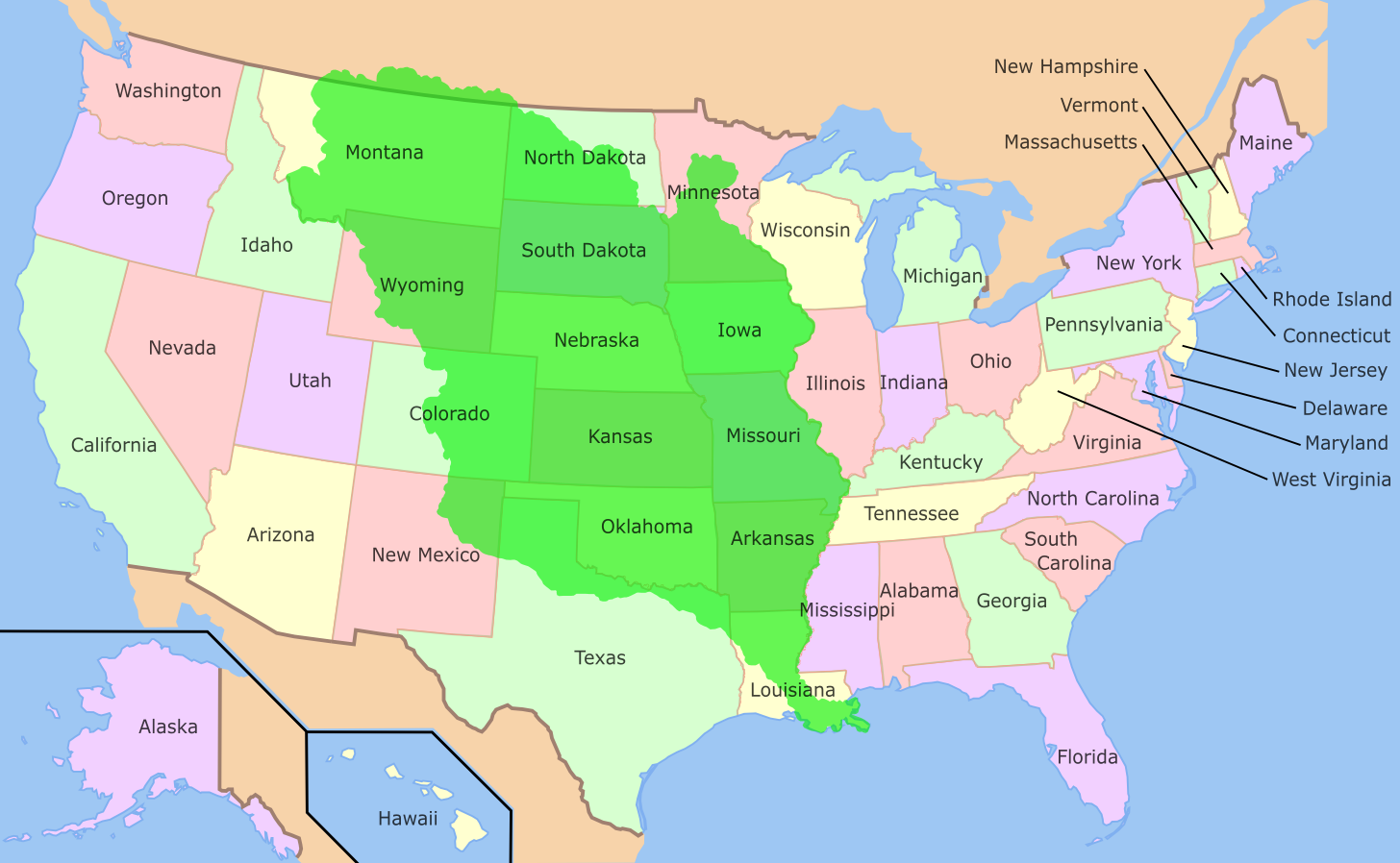

Before an invasion became necessary, U.S. ambassadors learned that Spain had ceded Louisiana to France via the

Before an invasion became necessary, U.S. ambassadors learned that Spain had ceded Louisiana to France via the Third Treaty of San Ildefonso