Japanese submarine I-25 on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

was a B1 type (''I-15''-class)

A number of days of rough swell prevented an immediate launch of the "Glen" floatplane. They stayed submerged during the day and went back to the surface at night. Finally on Tuesday, 17 February, Warrant Flying Officer Nobuo Fujita took off in the "Glen" for a reconnaissance flight over

A number of days of rough swell prevented an immediate launch of the "Glen" floatplane. They stayed submerged during the day and went back to the surface at night. Finally on Tuesday, 17 February, Warrant Flying Officer Nobuo Fujita took off in the "Glen" for a reconnaissance flight over

The incoming shell fire had a highly stimulative effect on the personnel at Battery Russell. Men leaped out of bed, crashing into things in the dark—turning on a light would be unthinkable—as they scrambled to battle stations in their underwear.

"We looked like hell," Capt. Jack R. Wood, commander of the battery, told historian Bert Webber later. "But we were ready to shoot back in a couple of minutes."

But when gunners requested permission to open fire, they were firmly refused. In part, this was because the submarine's location remained uncertain because of difficulties evaluating reports from different observation points; it was, after all, from shore. Furthermore, authorities later stated they wished to avoid revealing the locations of their guns to what they believed to be a reconnaissance mission. The sub may also have been out of range of Battery Russell's artillery; the mechanism used with the 10-inch disappearing guns limited their upward travel, which limited their effective range to less than . If the guns opened fire, the sub would be able to report back to Tokyo that a fleet of surface ships could simply heave to, from shore, and pound Battery Russell with impunity, then sail right on into the Columbia—where, among other valuable targets, upstream at

The incoming shell fire had a highly stimulative effect on the personnel at Battery Russell. Men leaped out of bed, crashing into things in the dark—turning on a light would be unthinkable—as they scrambled to battle stations in their underwear.

"We looked like hell," Capt. Jack R. Wood, commander of the battery, told historian Bert Webber later. "But we were ready to shoot back in a couple of minutes."

But when gunners requested permission to open fire, they were firmly refused. In part, this was because the submarine's location remained uncertain because of difficulties evaluating reports from different observation points; it was, after all, from shore. Furthermore, authorities later stated they wished to avoid revealing the locations of their guns to what they believed to be a reconnaissance mission. The sub may also have been out of range of Battery Russell's artillery; the mechanism used with the 10-inch disappearing guns limited their upward travel, which limited their effective range to less than . If the guns opened fire, the sub would be able to report back to Tokyo that a fleet of surface ships could simply heave to, from shore, and pound Battery Russell with impunity, then sail right on into the Columbia—where, among other valuable targets, upstream at

Following his successful observation flights on the second and third patrols, Warrant Officer Nubuo Fujita was specifically chosen for a special incendiary bombing mission to create forest fires in North America. ''I-25'' left Yokosuka on 15 August 1942 carrying six

Following his successful observation flights on the second and third patrols, Warrant Officer Nubuo Fujita was specifically chosen for a special incendiary bombing mission to create forest fires in North America. ''I-25'' left Yokosuka on 15 August 1942 carrying six

''Aviation History'' article

* ttps://web.archive.org/web/20180417022947/http://www.pilotmag.co.uk/2009/12/22/ss-fort-camosun-japanese-submarine-i-25/ SS Fort Camosun & Japanese submarine I-25

IJN I-25: Tabular Record of Movement - Revision 7

{{DEFAULTSORT:I-025 Type B1 submarines Ships built by Mitsubishi Heavy Industries 1940 ships World War II submarines of Japan Ships of the Aleutian Islands campaign Japanese submarines lost during World War II World War II shipwrecks in the Pacific Ocean Maritime incidents in September 1943

submarine

A submarine (or sub) is a watercraft capable of independent operation underwater. It differs from a submersible, which has more limited underwater capability. The term is also sometimes used historically or colloquially to refer to remotely o ...

of the Imperial Japanese Navy

The Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN; Kyūjitai: Shinjitai: ' 'Navy of the Greater Japanese Empire', or ''Nippon Kaigun'', 'Japanese Navy') was the navy of the Empire of Japan from 1868 to 1945, when it was dissolved following Japan's surrend ...

that served in World War II, took part in the Attack on Pearl Harbor

The attack on Pearl HarborAlso known as the Battle of Pearl Harbor was a surprise military strike by the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service upon the United States against the naval base at Pearl Harbor in Honolulu, Territory of Hawai ...

, and was the only Axis

An axis (plural ''axes'') is an imaginary line around which an object rotates or is symmetrical. Axis may also refer to:

Mathematics

* Axis of rotation: see rotation around a fixed axis

*Axis (mathematics), a designator for a Cartesian-coordinate ...

submarine to carry out aerial bombing on the continental United States

The contiguous United States (officially the conterminous United States) consists of the 48 adjoining U.S. states and the Federal District of the United States of America. The term excludes the only two non-contiguous states, Alaska and Hawaii ...

in World War II, during the so-called Lookout Air Raids, and the shelling of Fort Stevens, both attacks occurring in the state of Oregon

Oregon () is a U.S. state, state in the Pacific Northwest region of the Western United States. The Columbia River delineates much of Oregon's northern boundary with Washington (state), Washington, while the Snake River delineates much of it ...

.

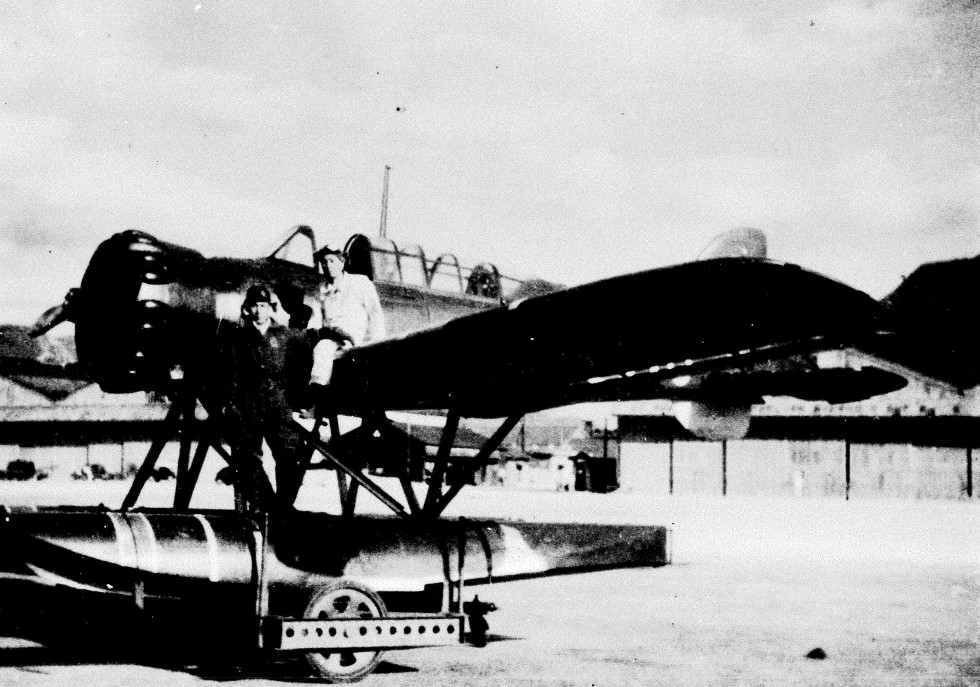

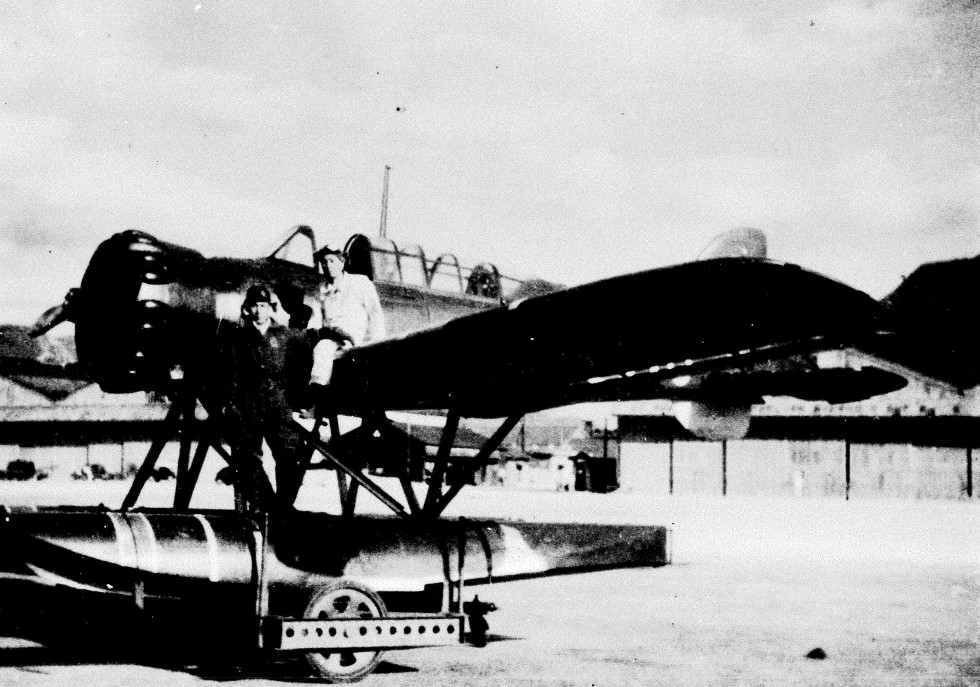

''I-25'', of 2,369 tonnes (2,600 tons), was long, with a range of , a maximum surface speed of and a maximum submerged speed of . She carried a two-seater Yokosuka E14Y reconnaissance

In military operations, reconnaissance or scouting is the exploration of an area by military forces to obtain information about enemy forces, terrain, and other activities.

Examples of reconnaissance include patrolling by troops (skirmishers ...

floatplane

A floatplane is a type of seaplane with one or more slender floats mounted under the fuselage to provide buoyancy. By contrast, a flying boat uses its fuselage for buoyancy. Either type of seaplane may also have landing gear suitable for land, m ...

, known to the Allies as "Glen". It was disassembled and stowed in a hangar in front of the conning tower

A conning tower is a raised platform on a ship or submarine, often armored, from which an officer in charge can conn the vessel, controlling movements of the ship by giving orders to those responsible for the ship's engine, rudder, lines, and gro ...

.

First patrol

In World War II, ''I-25'' served under the command ofLieutenant Commander

Lieutenant commander (also hyphenated lieutenant-commander and abbreviated Lt Cdr, LtCdr. or LCDR) is a commissioned officer rank in many navies. The rank is superior to a lieutenant and subordinate to a commander. The corresponding rank ...

Akiji Tagami who had graduated from Class 51 at Etajima, Hiroshima

is a city (formerly a town) located on the island of Etajima in Hiroshima Bay in southwestern Hiroshima Prefecture, Japan.

The modern city of Etajima was established on November 1, 2004, from the merger of the town of Etajima (from Aki Distri ...

. 26-year-old Lieutenant

A lieutenant ( , ; abbreviated Lt., Lt, LT, Lieut and similar) is a commissioned officer rank in the armed forces of many nations.

The meaning of lieutenant differs in different militaries (see comparative military ranks), but it is often sub ...

Tatsuo Tsukudo was the executive officer

An executive officer is a person who is principally responsible for leading all or part of an organization, although the exact nature of the role varies depending on the organization. In many militaries and police forces, an executive officer, o ...

(XO) on ''I-25''. ''I-25'' departed Yokosuka

is a city in Kanagawa Prefecture, Japan.

, the city has a population of 409,478, and a population density of . The total area is . Yokosuka is the 11th most populous city in the Greater Tokyo Area, and the 12th in the Kantō region.

The city ...

on 21 November 1941 in preparation for hostilities.

''I-25'' and three other submarines patrolled a line north of Oahu

Oahu () ( Hawaiian: ''Oʻahu'' ()), also known as "The Gathering Place", is the third-largest of the Hawaiian Islands. It is home to roughly one million people—over two-thirds of the population of the U.S. state of Hawaii. The island of O� ...

during the Japanese Attack on Pearl Harbor

The attack on Pearl HarborAlso known as the Battle of Pearl Harbor was a surprise military strike by the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service upon the United States against the naval base at Pearl Harbor in Honolulu, Territory of Hawai ...

. After the Japanese aircraft carrier

An aircraft carrier is a warship that serves as a seagoing airbase, equipped with a full-length flight deck and facilities for carrying, arming, deploying, and recovering aircraft. Typically, it is the capital ship of a fleet, as it allows ...

s sailed west following the attack, ''I-25'' and eight other submarines sailed eastwards to patrol the west coast of the United States. ''I-25'' patrolled off the mouth of the Columbia River

The Columbia River ( Upper Chinook: ' or '; Sahaptin: ''Nch’i-Wàna'' or ''Nchi wana''; Sinixt dialect'' '') is the largest river in the Pacific Northwest region of North America. The river rises in the Rocky Mountains of British Columbia, ...

. A scheduled shelling of American coastal cities on Christmas

Christmas is an annual festival commemorating the birth of Jesus Christ, observed primarily on December 25 as a religious and cultural celebration among billions of people around the world. A feast central to the Christian liturgical year ...

eve of 1941 was canceled because of the frequency of coastal air and surface patrols.

''I-25'' attacked SS ''Connecticut'' off the US coast. The damaged tanker managed to escape but ran aground at the mouth of the Columbia River. ''I-25'' then returned to Kwajalein

Kwajalein Atoll (; Marshallese: ) is part of the Republic of the Marshall Islands (RMI). The southernmost and largest island in the atoll is named Kwajalein Island, which its majority English-speaking residents (about 1,000 mostly U.S. civili ...

, arriving on 11 January 1942 to refuel and be refurbished.

Second patrol

''I-25'' left Kwajalein atoll in theMarshall Islands

The Marshall Islands ( mh, Ṃajeḷ), officially the Republic of the Marshall Islands ( mh, Aolepān Aorōkin Ṃajeḷ),'' () is an independent island country and microstate near the Equator in the Pacific Ocean, slightly west of the Intern ...

on 5 February for its next operational patrol in the south Pacific

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean (or, depending on definition, to Antarctica) in the south, and is bounded by the contine ...

. Tagami's orders were to reconnoitre the Australian harbours of Sydney

Sydney ( ) is the capital city of the state of New South Wales, and the most populous city in both Australia and Oceania. Located on Australia's east coast, the metropolis surrounds Sydney Harbour and extends about towards the Blue Mountai ...

, Melbourne

Melbourne ( ; Boonwurrung/Woiwurrung: ''Narrm'' or ''Naarm'') is the capital and most populous city of the Australian state of Victoria, and the second-most populous city in both Australia and Oceania. Its name generally refers to a metr ...

and Hobart

Hobart ( ; Nuennonne/Palawa kani: ''nipaluna'') is the capital and most populous city of the Australian island state of Tasmania. Home to almost half of all Tasmanians, it is the least-populated Australian state capital city, and second-smalle ...

followed by the New Zealand

New Zealand ( mi, Aotearoa ) is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and over 700 smaller islands. It is the sixth-largest island country ...

harbours of Wellington

Wellington ( mi, Te Whanganui-a-Tara or ) is the capital city of New Zealand. It is located at the south-western tip of the North Island, between Cook Strait and the Remutaka Range. Wellington is the second-largest city in New Zealand by me ...

and Auckland

Auckland (pronounced ) ( mi, Tāmaki Makaurau) is a large metropolitan city in the North Island of New Zealand. The most populous urban area in the country and the fifth largest city in Oceania, Auckland has an urban population of about ...

.

''I-25'' travelled on the surface for nine days, but as she approached the Australian coastline, she only travelled on the surface under the cover of night.

On Saturday 14 February, ''I-25'' was within a few miles of the coast near Sydney. The searchlights in Sydney could clearly be seen from the bridge of ''I-25''. Tagami then took ''I-25'' to a position south east of Sydney.

A number of days of rough swell prevented an immediate launch of the "Glen" floatplane. They stayed submerged during the day and went back to the surface at night. Finally on Tuesday, 17 February, Warrant Flying Officer Nobuo Fujita took off in the "Glen" for a reconnaissance flight over

A number of days of rough swell prevented an immediate launch of the "Glen" floatplane. They stayed submerged during the day and went back to the surface at night. Finally on Tuesday, 17 February, Warrant Flying Officer Nobuo Fujita took off in the "Glen" for a reconnaissance flight over Sydney Harbour

Port Jackson, consisting of the waters of Sydney Harbour, Middle Harbour, North Harbour and the Lane Cove and Parramatta Rivers, is the ria or natural harbour of Sydney, New South Wales, Australia. The harbour is an inlet of the Tasman Se ...

. The purpose was to look at Sydney's airbase. By 0730, Fujita had returned to ''I-25'' and disassembled the "Glen" and stowed it in the watertight hangar. Commander Tagami then pointed ''I-25'' southwards on the surface at . By midday on Wednesday 18 February, they were nearly south east of Sydney still heading southwards.

Their next mission was a similar flight over Melbourne. Tagami decided to launch the aircraft from Cape Wickham at the northern end of King Island at the western end of Bass Strait

Bass Strait () is a strait separating the island state of Tasmania from the Australian mainland (more specifically the coast of Victoria, with the exception of the land border across Boundary Islet). The strait provides the most direct waterw ...

about halfway between Victoria

Victoria most commonly refers to:

* Victoria (Australia), a state of the Commonwealth of Australia

* Victoria, British Columbia, provincial capital of British Columbia, Canada

* Victoria (mythology), Roman goddess of Victory

* Victoria, Seyche ...

and Tasmania

)

, nickname =

, image_map = Tasmania in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of Tasmania in AustraliaCoordinates:

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdi ...

. The floatplane was launched on 26 February for its reconnaissance flight to Melbourne over Port Phillip Bay

Port Phillip ( Kulin: ''Narm-Narm'') or Port Phillip Bay is a horsehead-shaped enclosed bay on the central coast of southern Victoria, Australia. The bay opens into the Bass Strait via a short, narrow channel known as The Rip, and is com ...

.

Fujita's next reconnaissance flight in Australia was over Hobart on 1 March. ''I-25'' then headed for New Zealand where Fujita flew another reconnaissance flight over Wellington on 8 March. Fujita next flew over Auckland on 13 March, followed by Fiji

Fiji ( , ,; fj, Viti, ; Fiji Hindi: फ़िजी, ''Fijī''), officially the Republic of Fiji, is an island country in Melanesia, part of Oceania in the South Pacific Ocean. It lies about north-northeast of New Zealand. Fiji consi ...

on 17 March.

''I-25'' returned to its base at Kwajalein on 31 March and then proceeded to Yokosuka for refit. ''I-25'' was in Yokosuka drydock number 5 on 18 April 1942 when one of the Doolittle Raid

The Doolittle Raid, also known as the Tokyo Raid, was an air raid on 18 April 1942 by the United States on the Japanese capital Tokyo and other places on Honshu during World War II. It was the first American air operation to strike the Jap ...

B-25 Mitchell

The North American B-25 Mitchell is an American medium bomber that was introduced in 1941 and named in honor of Major General William "Billy" Mitchell, a pioneer of U.S. military aviation. Used by many Allied air forces, the B-25 served in ...

bombers damaged Japanese aircraft carrier Ryūhō in adjacent drydock number 4.

Third patrol

While outbound past theAleutian Islands

The Aleutian Islands (; ; ale, Unangam Tanangin,”Land of the Aleuts", possibly from Chukchi ''aliat'', "island"), also called the Aleut Islands or Aleutic Islands and known before 1867 as the Catherine Archipelago, are a chain of 14 large v ...

for a third war patrol off the west coast of North America, ''I-25''s Glen seaplane overflew United States military installations on Kodiak Island

Kodiak Island (Alutiiq: ''Qikertaq''), is a large island on the south coast of the U.S. state of Alaska, separated from the Alaska mainland by the Shelikof Strait. The largest island in the Kodiak Archipelago, Kodiak Island is the second larg ...

. The surveillance on 21 May 1942 was in preparation for the northern diversion of the Battle of Midway

The Battle of Midway was a major naval battle in the Pacific Theater of World War II that took place on 4–7 June 1942, six months after Japan's attack on Pearl Harbor and one month after the Battle of the Coral Sea. The U.S. Navy under A ...

.

Shortly after midnight on 20 June 1942, ''I-25'' torpedoed the new, coal-burning Canadian freighter SS ''Fort Camosun'' off the coast of Washington. The freighter was bound for England with a cargo of war production materials including zinc, lead, and plywood. One torpedo struck the port side below the bridge and flooded the 2nd and 3rd cargo holds. Canadian corvette

A corvette is a small warship. It is traditionally the smallest class of vessel considered to be a proper (or " rated") warship. The warship class above the corvette is that of the frigate, while the class below was historically that of the sloop ...

s and reached the stricken freighter after dawn and rescued the crew from lifeboats. ''Fort Camosun'' was towed back into Puget Sound for repairs, and later survived a second torpedo attack by ''I-27'' in the Gulf of Aden

The Gulf of Aden ( ar, خليج عدن, so, Gacanka Cadmeed 𐒅𐒖𐒐𐒕𐒌 𐒋𐒖𐒆𐒗𐒒) is a deepwater gulf of the Indian Ocean between Yemen to the north, the Arabian Sea to the east, Djibouti to the west, and the Guardafui Chann ...

in the fall of 1943.

On the evening of 21 June 1942, ''I-25'' followed a fleet of fishing vessels to avoid minefields near the mouth of the Columbia River, in Oregon. ''I-25'' fired seventeen 14-cm (5.5-inch) shells at Battery Russell, a small coastal army installation within Fort Stevens which was later decommissioned. Fort Stevens was equipped with two 10-inch disappearing gun

A disappearing gun, a gun mounted on a ''disappearing carriage'', is an obsolete type of artillery which enabled a gun to hide from direct fire and observation. The overwhelming majority of carriage designs enabled the gun to rotate bac ...

s, some 12-inch mortars, 75 mm field guns, .50-caliber machine guns, and associated searchlights, observation posts, and secret radar

Radar is a detection system that uses radio waves to determine the distance (''ranging''), angle, and radial velocity of objects relative to the site. It can be used to detect aircraft, ships, spacecraft, guided missiles, motor vehicles, ...

capability. Damage was minimal. In fact, the only items of significance damaged on the fort were a baseball backstop and some power and telephone lines.

The incoming shell fire had a highly stimulative effect on the personnel at Battery Russell. Men leaped out of bed, crashing into things in the dark—turning on a light would be unthinkable—as they scrambled to battle stations in their underwear.

"We looked like hell," Capt. Jack R. Wood, commander of the battery, told historian Bert Webber later. "But we were ready to shoot back in a couple of minutes."

But when gunners requested permission to open fire, they were firmly refused. In part, this was because the submarine's location remained uncertain because of difficulties evaluating reports from different observation points; it was, after all, from shore. Furthermore, authorities later stated they wished to avoid revealing the locations of their guns to what they believed to be a reconnaissance mission. The sub may also have been out of range of Battery Russell's artillery; the mechanism used with the 10-inch disappearing guns limited their upward travel, which limited their effective range to less than . If the guns opened fire, the sub would be able to report back to Tokyo that a fleet of surface ships could simply heave to, from shore, and pound Battery Russell with impunity, then sail right on into the Columbia—where, among other valuable targets, upstream at

The incoming shell fire had a highly stimulative effect on the personnel at Battery Russell. Men leaped out of bed, crashing into things in the dark—turning on a light would be unthinkable—as they scrambled to battle stations in their underwear.

"We looked like hell," Capt. Jack R. Wood, commander of the battery, told historian Bert Webber later. "But we were ready to shoot back in a couple of minutes."

But when gunners requested permission to open fire, they were firmly refused. In part, this was because the submarine's location remained uncertain because of difficulties evaluating reports from different observation points; it was, after all, from shore. Furthermore, authorities later stated they wished to avoid revealing the locations of their guns to what they believed to be a reconnaissance mission. The sub may also have been out of range of Battery Russell's artillery; the mechanism used with the 10-inch disappearing guns limited their upward travel, which limited their effective range to less than . If the guns opened fire, the sub would be able to report back to Tokyo that a fleet of surface ships could simply heave to, from shore, and pound Battery Russell with impunity, then sail right on into the Columbia—where, among other valuable targets, upstream at Portland

Portland most commonly refers to:

* Portland, Oregon, the largest city in the state of Oregon, in the Pacific Northwest region of the United States

* Portland, Maine, the largest city in the state of Maine, in the New England region of the northeas ...

, Oregon Shipbuilding Corporation, one of Henry Kaiser

Henry John Kaiser (May 9, 1882 – August 24, 1967) was an American industrialist who became known as the father of modern American shipbuilding. Prior to World War II, Kaiser was involved in the construction industry; his company was one of ...

's shipyards, was cranking out Liberty ship

Liberty ships were a class of cargo ship built in the United States during World War II under the Emergency Shipbuilding Program. Though British in concept, the design was adopted by the United States for its simple, low-cost construction. M ...

s at a rate of more than one a week. This, obviously, was not something the Navy could take a chance on.

In the end, Battery Russell sat there and absorbed the fire without a single shot in reply. It was a turning point for American coastal artillery

Coastal artillery is the branch of the armed forces concerned with operating anti-ship artillery or fixed gun batteries in coastal fortifications.

From the Middle Ages until World War II, coastal artillery and naval artillery in the form of ...

, and the failure to respond caused re-evaluation of men and artillery allocated to coastal defense.

Fourth patrol

Following his successful observation flights on the second and third patrols, Warrant Officer Nubuo Fujita was specifically chosen for a special incendiary bombing mission to create forest fires in North America. ''I-25'' left Yokosuka on 15 August 1942 carrying six

Following his successful observation flights on the second and third patrols, Warrant Officer Nubuo Fujita was specifically chosen for a special incendiary bombing mission to create forest fires in North America. ''I-25'' left Yokosuka on 15 August 1942 carrying six incendiary bomb

Incendiary weapons, incendiary devices, incendiary munitions, or incendiary bombs are weapons designed to start fires or destroy sensitive equipment using fire (and sometimes used as anti-personnel weaponry), that use materials such as napalm, ...

s. On 9 September, the crew again deployed the "Glen", which dropped two bombs over forest land near Brookings, Oregon. This attack by an enemy airplane was later called the " Lookout Air Raids", and was the ''only'' time that the mainland United States was ever bombed by enemy aircraft and the second continental territory to be bombed as such during wartime, after the bombing of Dutch Harbor in Unalaska, Alaska.

Warrant Officer Fujita's mission had been to trigger wildfire

A wildfire, forest fire, bushfire, wildland fire or rural fire is an unplanned, uncontrolled and unpredictable fire in an area of combustible vegetation. Depending on the type of vegetation present, a wildfire may be more specifically ident ...

s across the coast; at the time, the Tillamook Burn

The Tillamook Burn was a series of forest fires in the Northern Oregon Coast Range of Oregon in the United States that destroyed a total area of of old growth timber in what is now known as the Tillamook State Forest. There were four wildfir ...

incidents of 1933 and 1939 were well known, as was the destruction of the city of Bandon, Oregon

Bandon () is a city in Coos County, Oregon, United States, on the south side of the mouth of the Coquille River. It was named by George Bennet, an Irish peer, who settled nearby in 1873 and named the town after Bandon in Ireland, his hometown ...

by a smaller out-of-control wildfire in 1936. But light winds, wet weather conditions and two quick-acting fire lookout

A fire lookout (partly also called a fire watcher) is a person assigned the duty to look for fire from atop a building known as a fire lookout tower. These towers are used in remote areas, normally on mountain tops with high elevation and a ...

s kept the fires under control.McCash, William. ''Bombs Over Brookings: The World War II Bombings of Curry County, Oregon, and the Postwar Friendship Between Brookings and the Japanese Pilot, Nobuo Fujita.'' Bend, Ore.: Maverick, 2005 In fact, had the winds been sufficiently brisk to stoke widespread forest fires, the lightweight Glen may have had difficulty navigating through the bad weather. Shortly after the Glen seaplane had landed and been disassembled for storage, ''I-25'' was bombed at by a United States Army A-29 Hudson piloted by Captain Jean H. Daugherty from McChord Field

McChord Field is a United States Air Force base in the northwest United States, in Pierce County, Washington. South of Tacoma, McChord Field is the home of the 62d Airlift Wing, Air Mobility Command, the field's primary mission being world ...

near Tacoma, Washington

Tacoma ( ) is the county seat of Pierce County, Washington, United States. A port city, it is situated along Washington's Puget Sound, southwest of Seattle, northeast of the state capital, Olympia, Washington, Olympia, and northwest of Mount ...

. The Hudson carried general-purpose demolition bombs with delayed fuzes rather than depth charges. The bombs caused minor damage, but quick response by a Coast Guard cutter and three more aircraft caused ''I-25'' to be more cautious on a second bombing raid on 29 September 1942. The Glen seaplane was assembled and launched in pre-dawn darkness using Cape Blanco Light as a reference. The plane was heard at 0522 by a work crew at the Grassy Knob Lookout east of Port Orford, Oregon

Port Orford (Tolowa: tr’ee-ghi~’- ’an’ ) is a city in Curry County on the southern coast of Oregon, United States. The population was 1,133 at the 2010 census.

The city takes its name from George Vancouver's original name for nearby Ca ...

; but fire crews from the Gold Beach

Gold, commonly known as Gold Beach, was the code name for one of the five areas of the Allied invasion of German-occupied France in the Normandy landings on 6 June 1944, during the Second World War. Gold, the central of the five areas, was ...

Ranger Station were unable to locate any evidence of the two incendiary bombs dropped. The Glen seaplane was again recovered, but ''I-25'' decided not to risk a third flight with the two remaining incendiary bombs. Captain Tagami took I-25 to rest "...on the bottom f_the_harbor_of_ f_the_harbor_of_Port_Orford_">Port_Orford.html"_;"title="f_the_harbor_of_Port_Orford">f_the_harbor_of_Port_Orford_until_night_time.

At_0415_4_October_1942_''I-25''_torpedoed_the__tanker_List_of_shipwrecks_in_October_1942#4_October.html" ;"title="Port_Orford_.html" ;"title="Port_Orford.html" ;"title="f the harbor of Port Orford">f the harbor of Port Orford ">Port_Orford.html" ;"title="f the harbor of Port Orford">f the harbor of Port Orford until night time.

At 0415 4 October 1942 ''I-25'' torpedoed the tanker List of shipwrecks in October 1942#4 October">''Camden'' en route from San Pedro, California, to Puget Sound with a cargo of of gasoline. The damaged tanker was towed to the mouth of the Columbia River. When its draft was discovered to be too great to reach repair facilities in Portland, Oregon, another tow was arranged to Puget Sound; but the tanker was destroyed on 10 October by a fire of unknown origin during the second tow.

On the evening of 5 October 1942 ''I-25'' torpedoed the Richfield Oil Company tanker ''Larry Doheny'', which sank the next day. The cargo of of oil was lost with 2 of the tanker's crew and 4 members of the United States Navy Armed Guard

United States Navy Armed Guard units were established during World War II and headquartered in New Orleans.World War II U.S. Navy Armed Guard and World War II U.S. Merchant Marine, 2007-2014 Project Liberty Ship, Project Liberty Ship, P.O. Box 2 ...

. Survivors reached Port Orford, Oregon

Port Orford (Tolowa: tr’ee-ghi~’- ’an’ ) is a city in Curry County on the southern coast of Oregon, United States. The population was 1,133 at the 2010 census.

The city takes its name from George Vancouver's original name for nearby Ca ...

on the evening of 6 October.

Two submarines were sighted on 11 October 1942 about off the coast of Washington as ''I-25'' was returning to Japan. ''I-25'' fired its last torpedo at the lead submarine, which sank in 20 seconds with the loss of all hands. ''I-25'' reported sinking a U.S. submarine, but the submarine was actually Soviet ''L-16'' which was sailing with ''L-15'' en route from Vladivostok

Vladivostok ( rus, Владивосто́к, a=Владивосток.ogg, p=vɫədʲɪvɐˈstok) is the largest city and the administrative center of Primorsky Krai, Russia. The city is located around the Golden Horn Bay on the Sea of Japan, c ...

to the Panama Canal via Unalaska, Alaska, and San Francisco

San Francisco (; Spanish for " Saint Francis"), officially the City and County of San Francisco, is the commercial, financial, and cultural center of Northern California. The city proper is the fourth most populous in California and 17t ...

. United States Navy Chief Photographer's Mate Sergi Andreevich Mihailoff of Arcadia, California

Arcadia is a city in Los Angeles County, California, United States, located about northeast of downtown Los Angeles in the San Gabriel Valley and at the base of the San Gabriel Mountains. It contains a series of adjacent parks consisting of t ...

, was aboard ''L-16'' as a liaison officer and interpreter, and was killed with the remainder of the submarine crew. The United States Navy Western Sea Frontier denied loss of any submarine and withheld information about the Soviet loss because, at the time, the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

was officially neutral in the war between Japan and the United States.

SS ''H.M. Storey'' was bringing fuel oil

Fuel oil is any of various fractions obtained from the distillation of petroleum (crude oil). Such oils include distillates (the lighter fractions) and residues (the heavier fractions). Fuel oils include heavy fuel oil, marine fuel oil (MFO), bun ...

from Noumea, New Caledonia

)

, anthem = ""

, image_map = New Caledonia on the globe (small islands magnified) (Polynesia centered).svg

, map_alt = Location of New Caledonia

, map_caption = Location of New Caledonia

, mapsize = 290px

, subdivision_type = Sovereign st ...

, in the South Pacific Ocean

South is one of the cardinal directions or compass points. The direction is the opposite of north and is perpendicular to both east and west.

Etymology

The word ''south'' comes from Old English ''sūþ'', from earlier Proto-Germanic ''*sunþ ...

to Los Angeles

Los Angeles ( ; es, Los Ángeles, link=no , ), often referred to by its initials L.A., is the List of municipalities in California, largest city in the U.S. state, state of California and the List of United States cities by population, sec ...

. On May 17, 1943, ''I-25'' torpedoed and fired shells at the ship. The attack killed two of the crew; 63 of the crew made it in to the ship's lifeboat

Lifeboat may refer to:

Rescue vessels

* Lifeboat (shipboard), a small craft aboard a ship to allow for emergency escape

* Lifeboat (rescue), a boat designed for sea rescues

* Airborne lifeboat, an air-dropped boat used to save downed airmen

...

s before she sank. US destroyer

In naval terminology, a destroyer is a fast, manoeuvrable, long-endurance warship intended to escort

larger vessels in a fleet, convoy or battle group and defend them against powerful short range attackers. They were originally developed in ...

USS ''Fletcher'' rescued the crew in the lifeboats and took them to Port Vila

Port Vila (french: Port-Vila), or simply Vila (; french: Vila; bi, Vila ), is the capital and largest city of Vanuatu. It is located on the island of Efate.

Its population in the last census (2009) was 44,040, an increase of 35% on the ...

Efate

Efate (french: Éfaté) is an island in the Pacific Ocean which is part of the Shefa Province in Vanuatu. It is also known as Île Vate.

Geography

It is the most populous (approx. 66,000) island in Vanuatu. Efate's land area of makes it Vanu ...

, Vanuatu

Vanuatu ( or ; ), officially the Republic of Vanuatu (french: link=no, République de Vanuatu; bi, Ripablik blong Vanuatu), is an island country located in the South Pacific Ocean. The archipelago, which is of volcanic origin, is east of no ...

, in the South Pacific.

1942 North American west coastWebber (1985) "Silent Siege-II", p. iv

Loss

''I-25'' was sunk less than a year later by one or more of thedestroyer

In naval terminology, a destroyer is a fast, manoeuvrable, long-endurance warship intended to escort

larger vessels in a fleet, convoy or battle group and defend them against powerful short range attackers. They were originally developed in ...

s , , or which were involved in a series of naval engagements from late August to mid September 1943 off the New Hebrides

New Hebrides, officially the New Hebrides Condominium (french: link=no, Condominium des Nouvelles-Hébrides, "Condominium of the New Hebrides") and named after the Hebrides Scottish archipelago, was the colonial name for the island group ...

islands, approximately northeast of Espiritu Santo

Espiritu Santo (, ; ) is the largest island in the nation of Vanuatu, with an area of and a population of around 40,000 according to the 2009 census.

Geography

The island belongs to the archipelago of the New Hebrides in the Pacific region ...

. Which American ship sank the ''I-25'' (or any of the other IJN submarines in the vicinity) remains unknown.

Notes

Bibliography

* * * Jentschura, Hansgeorg; Dieter Jung, Peter Mickel. ''Warships of the Imperial Japanese Navy, 1869–1945.'' United States Naval Institute, 1977. Annapolis, Maryland, USA. . *''Aviation History'' article

External links

* ttps://web.archive.org/web/20180417022947/http://www.pilotmag.co.uk/2009/12/22/ss-fort-camosun-japanese-submarine-i-25/ SS Fort Camosun & Japanese submarine I-25

IJN I-25: Tabular Record of Movement - Revision 7

{{DEFAULTSORT:I-025 Type B1 submarines Ships built by Mitsubishi Heavy Industries 1940 ships World War II submarines of Japan Ships of the Aleutian Islands campaign Japanese submarines lost during World War II World War II shipwrecks in the Pacific Ocean Maritime incidents in September 1943